外商直接投资和东道国工资:爱尔兰工厂面板数据新证据【外文翻译】

9-08 外商直接投资_劳动力市场与工资溢出效应

摘要:利用中国制造业12180家企业1998~2001年的面板数据,本文在估计了内资企业和外资企业在不同行业和地区间工资差距的基础上,利用系统广义矩估计方法,从劳动力市场角度,考察了FD I 通过影响劳动力供求以及由支付高工资所导致的工资溢出效应两种途径对内资企业的工资影响。

从总体上看,外资企业自身的较高技术水平、资本密集度等企业特征能在很大程度上解释内、外资企业间的工资差距,但在控制了上述企业特征因素的影响后,外资企业的工资水平仍不同程度的高于内资企业;外资企业通过影响劳动力供求对内资企业的工资水平具有显著的正向影响,而外资企业通过支付高工资这一行为,对内资企业存在明显的负向工资溢出效应,特别是对于细分行业而言;而内资企业工资水平的提高更多的是来自于其他内资企业的工资溢出影响以及企业自身技术水平和人均资本投入的提高。

关键词:外商直接投资劳动力市场工资溢出工资差距系统广义矩估计一、引言由于外商直接投资(FDI )集资本、技术和管理等技能于一体,被认为是直接资本输入和间接知识溢出的重要源泉(Balasubramanyam et al.,1996),因此众多的发展中国家尤其对于处于经济转型中的中国而言,把引进外资作为经济发展的一个重要战略。

改革开放30年来,我国的引资规模大幅增长,实际利用外资一直保持在世界前列。

据统计,截至2007年底,中国累计批准设立外商投资企业63.5万家,实际吸收外商直接投资超过7700亿美元,已成为全世界吸收外资最多的国家之一。

在华外商投资企业已经成为我国经济的重要组成部分,对经济发展产生着深层次的影响。

伴随着外资的大量流入,我国内资企业中的国有企业、城镇集体企业以及其他类型企业的平均工资出现了显著地提高①。

在1992年,上述3类企业的平均工资分别为2731元、2000元、3763元,到2006年达到13021元、7663元和12221元,分别增长了约376.8%、283.2%和224.8%。

爱尔兰吸引外商直接投资的 理论思考与分析

爱尔兰经济发展在国际上引起关注最多的一个方面 , 是

2000

2001

2002

外商直接投资 ( FD I) 所起的巨大作用 。爱尔兰在吸引和利用

ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ

出口

9811

9814

9317

外商直接投资尤其是美国直接投资方面取得了显著的成绩 。

进口

8415

8314

7510

根据联合国 1997年世界投资报告 , 爱尔兰是外商直接投资流 入对国内生产总值和固定资本形成总额贡献最高的经济体之 一 。[2 ]外商直接投资的大规模流入成为爱尔兰国内生产总值和

国家 丹麦 法国 比利时 - 卢森堡 爱尔兰 荷兰 意大利 英国 德国

百分比 ( % ) 37 33 27 27 22 14 14 5

资料来源 : UN. World Investment Report 1998 - Transnational Corpo2 rations, Market Structure and Competition Policy. New York and Geneva: U2 nited Nations Publication, 1997, p. 125.

15 1 J T G

R E FO RM O F ECONOM IC S YS TEM

NO. 4. 20 09

万 。“也许更令人注目的是爱尔兰相对于美国和欧盟的增长 。 1994~2003年期间 , 欧盟经济年均实际增长率仅超过 2% , 美 国仅超过 3% , 而爱尔兰为 8%。”[1 ]爱尔兰的经济 “腾飞 ”在 世界上引起了广泛的关注 , 成为其他国家 , 尤其是欧洲国家 的榜样 。

欧盟 15国 546 688

2, 113 3, 029 6, 271

FDI_国内资本与经济增长_1987_2001年中国省际面板数据的证据

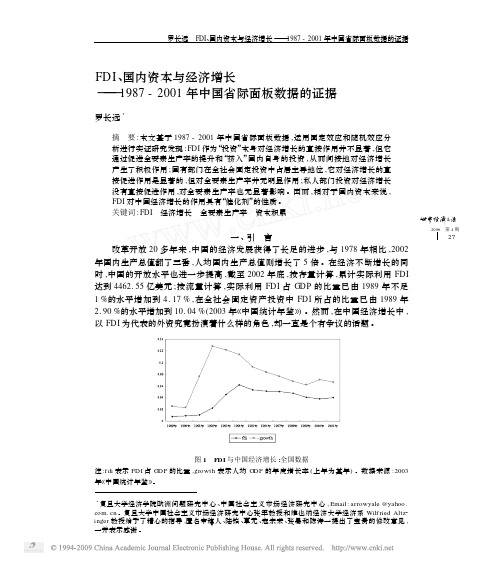

2006 第4期27 FDI 、国内资本与经济增长———1987-2001年中国省际面板数据的证据罗长远3摘 要:本文基于1987-2001年中国省际面板数据,运用固定效应和随机效应分析进行实证研究发现:FDI 作为“投资”本身对经济增长的直接作用并不显著,但它通过促进全要素生产率的提升和“挤入”国内自身的投资,从而间接地对经济增长产生了积极作用;国有部门在全社会固定投资中占居主导地位,它对经济增长的直接促进作用是显著的,但对全要素生产率并无明显作用;私人部门投资对经济增长没有直接促进作用,对全要素生产率也无显著影响。

因而,相对于国内资本来说,FDI 对中国经济增长的作用具有“催化剂”的性质。

关键词:FDI 经济增长 全要素生产率 资本积累一、引 言改革开放20多年来,中国的经济发展获得了长足的进步,与1978年相比,2002年国内生产总值翻了三番,人均国内生产总值则增长了5倍。

在经济不断增长的同时,中国的开放水平也进一步提高,截至2002年底,按存量计算,累计实际利用FDI 达到4462.55亿美元;按流量计算,实际利用FDI 占GDP 的比重已由1989年不足1%的水平增加到4.17%,在全社会固定资产投资中FDI 所占的比重已由1989年2.90%的水平增加到10.04%(2003年《中国统计年鉴》)。

然而,在中国经济增长中,以FDI 为代表的外资究竟扮演着什么样的角色,却一直是个有争议的话题。

图1 FDI 与中国经济增长:全国数据注:fdi 表示FDI 占G DP 的比重,growth 表示人均G DP 的年度增长率(上年为基年)。

数据来源:2003年《中国统计年鉴》。

3复旦大学经济学院欧洲问题研究中心、中国社会主义市场经济研究中心,Email :arrowyale @ 。

复旦大学中国社会主义市场经济研究中心张军教授和维也纳经济大学经济系Wilf ried Altz 2inger 教授给予了精心的指导,匿名审稿人、陆铭、章元、寇宗来、张晏和陈诗一提出了宝贵的修改意见,一并表示感谢。

外文翻译--墨西哥的外商直接投资和进出口

本科毕业论文外文翻译外文题目:Foreign Direct Investment, Exports and Imports in Mexico 出处:The World Economy作者:Penelope Pacheco Lopez译文:墨西哥的外商直接投资和进出口一、简介自20世纪80年代中期以来,特别是1994年签署北美自由贸易协定(NAFTA)之后,外商直接投资大幅进入墨西哥。

墨西哥政府奉行降低外商直接投资的进入壁垒的积极政策,希望跨国公司引进外商直接投资通过知识溢出与出口增长较快推动经济。

在2001年,墨西哥是拉美最大的外商直接投资(贸发会议,2002年)获得者,并成为世界第二大贸易发展中国家(世界贸易组织,2001),有近三分之二的出口来自跨国公司(贸发会议,2002)。

本文的目的有三:首先,描述外商直接投资自由化的过程,并描述性分析外商直接投资在墨西哥的作用;第二,探讨外商直接投资和进出口的因果关系;第三,简短的总结评价外商直接投资与墨西哥的经济发展。

一般的外国直接投资的影响是深远的,有证据表明外商直接投资效率显著影响,如在效率,就业要素价格和贸易方面。

墨西哥的情况是,各种研究都集中在外商直接投资对劳动生产率(布洛姆斯特罗姆和佩尔松,1983年;布洛姆斯特罗姆,1988年),工资(芬斯特拉和汗森,1997年),和经济增长(拉米雷斯2000年;2003年)的影响。

然而,尽管外商直接投资和贸易增长迅速,外商直接投资对出口和进口的影响尚未广泛。

最近的一篇文章探讨外商直接投资和出口的因果关系(安格斯,2002年),但外商直接投资和进口的因果关系还没有研究。

二、外商直接投资的自由化和作用(一)外商直接投资的自由化随着时间的推移,对外商投资法已逐渐放松管制,减少了对墨西哥公民或活动范围管制。

在特别是1989年和1993年的改革,尝试将外商投资法与北美自由贸易协定兼容。

到1995年,1996年,1998年,1999年和2000年对外商投资法进一步修订,加快了外商直接投资参与墨西哥的经济活动。

东道国腐败与中国对外直接投资_基于跨国面板数据的实证研究_胡兵

《国际贸易问题》2013年第10期国际投资与跨国经营东道国腐败与中国对外直接投资——基于跨国面板数据的实证研究胡兵邓富华张明摘要:为了考察东道国腐败对中国对外直接投资的影响,本文采用2003-2011年中国对东道国直接投资的跨国面板数据进行实证检验。

结果表明:在一些腐败水平较低的国家,腐败会对中国对外直接投资产生明显的“摩擦效应”,而在一些腐败水平较高的国家,腐败会作为一种次优选择对中国对外直接投资产生一定程度的“润滑效应”。

在采用动态面板GMM 方法控制腐败的内生性问题后,这一结论依然成立,表明东道国腐败对中国对外直接投资的影响是一定制度环境中腐败的“摩擦效应”和“润滑效应”这两种力量相互平衡的结果。

关键词:东道国;腐败;对外直接投资;动态面板GMM一、引言自20世纪70年代之后主要发生在发达国家的跨国资本流动开始出现调整,由于发展中国家拥有低廉的劳动力、丰富的资源要素以及广阔的市场潜力,大量的跨国直接投资开始频繁地流入发展中国家。

但与以发达国家作为东道国相比,跨国公司选择进入发展中国家往往需要应对其欠成熟的制度环境,在决定跨国直接投资的成本、风险和收益博弈中,东道国的制度质量是重要的参考变量。

而腐败作为衡量制度质量的重要标识,在跨国公司的投资决策中占据着重要权重,已经成为与东道国成本和经济政策同等重要的因素。

按照传统的认识,东道国腐败会产生“摩擦效应”(sand the wheels ),通过增大跨国投资活动的风险、增加母国投资者的沉没成本并形成连续被东道国官员“挟持”的路径依赖(Hines,1995;Wei,2000;Habib 和Zurawicki,2002),弱化母国企业进行直接投资的激励。

当东道国存在制度安排上的缺陷,比如对外资的规制过多时,外国投资者很难通过正常的途径进入东道国的一些投资领域,尤其是能源、公共基础项目等领域,而腐败作为一种次优选择却会产生“润滑效应”(grease the wheels ),帮助投资者减少制度摩擦,提高时间配置效率,因而腐败也可能会有利于跨国直接投资(Egger 和Winner,2005)。

外国直接投资与当地企业发展关系研究综述

外国直接投资与当地企业发展关系研究综述 国外学术界关于外国直接投资(FDI)与当地企业发展方面的研究已经比较系统,总体来说,基本上沿着FDI对东道国的技术转移和技术外溢的角度进行理论分析和实证检验。2000年以来,讨论外国直接投资对东道国企业发展的文献中,发展中国家的实证分析逐渐多了起来,这是对已经形成的理论模型的进一步验证,同时也对各国政府吸引FDI的政策提供了丰富的实践依据。本文准备从以下三个方面对基本理论模型与最新研究成果进行综述:FDI对其子公司的直接效应(direct effect);FDI与东道国供应商的后向关联(backward linkages);FDI与东道国竞争者的横向关联(horizontal linkages);而后两者都属于FDI的间接效应(indirect effect)。

一、跨国企业对其子公司的直接效应:理论综述与实证分析 直接效应指的是跨国企业在国外建立子公司时,对其子公司进行部分技术转移,在不改变所有权或活动的控制权的情况下,FDI会首先引起所在东道国整体技术知识和技能的提高。直接效应所涉及的是一种内部化的技术转移,是可以为跨国企业母公司所控制的,由跨国企业母公司总体战略决定的,并且收益可以预期。应该说这种技术扩散方式是在跨国企业中应用得最早和最普遍的。

1966年Vernon的“产品周期中的国际投资与国际贸易”一文中提出的产品生命周期假设应该说是直接效应分析的最初理论模型;该假设分析了新产品研发、生产、贸易与投资的过程,其所包含新技术从高技能劳动密集型向低技能劳动密集型的转化。

当产品达到标准化阶段时,跨国企业便在成本较低的发展中国家进行投资设厂,生产该产品,当地销售并出口到发达国家。之所以内部化技术转移成为跨国企业进行技术扩散的首选和早期形式,主要是由于无法控制的技术外溢会使得私人收益小于社会收益,跨国企业在进行技术转移时将会更倾向于内部化方式,即通过自己的子公司将技术转移到母国之外。

外商直接投资区位决策因素分析_基于区域面板数据的实证分析_廖上胜

年以来,中国开始进入区域发展的政策调整时期。2000年,中央提

出实施西部大开发战略2004年,为了平衡东、中、西部经济发展格

FDI区位选择影响因素

指标代码及相关说明

制度变量

( P 使用虚拟变量来计量)

成本因素(以劳动力成本来代替) W(可比价货币工资来代表,滞后一期)

市场容量

GD( P 以1995年不变价为基数)

集聚效应

CFD( I 以各区域累计FDI存量来表示,并滞后一期)

基础设施状况

K(以全社会固定投资总额占当年GDP比重)

பைடு நூலகம்

来作为影响在外国的外资企业区位选择的因素,具体详见(表2)所

示。在上面的影响因素中,制度变量在检验时使用虚拟变量来表示,

这就需要对我国引进FDI的阶段进行详细研究,并对每个阶段的政

图3 全国、东部、中部和西部地区年度FDI环比增速变化(1986-2008)单位:%

表2

影响在华开展对外直接投资跨国公司区位选择的因素

6.76 5.58

2619 阶段波动程度相差较大?其实,这些都是FDI区位选择问题。近年

3059

1990 1991

2945 3864

92.96 93.66

112 167

3.53 4.06

111 94

3.50 2.28

3168 4126

关于FDI区位选择的影响因素研究一直受到国内外学者的关注,

1992

数据来源: 《中国对外经济统计年鉴》 (1986-2009 年)

外文翻译--全球化,外商直接投资与越南就业

本科毕业论文外文翻译外文题目:Globalization, FDI and employment in Viet Nam 出处:Transnational Corporations,Vol.15,No.1(April 2006) 作者:Rhys Jenkins*译文:全球化,外商直接投资与越南就业引言本文研究当越南在20世纪90年代受到外资流入加快其全球经济一体化时,外国直接投资对越南就业的影响。

尽管外国公司工业产出和出口量大,然而直接创造就业机会已经非常有限,因为高劳动生产率和低比例的价值添加到这项投资的多输出。

文章还表明,外国直接投资产生的间接就业效应很小甚至可能是负面的,因为外国投资者创造和对国内投资的排挤效应的相关性是有效的。

关键词:外国直接投资,就业,越南; 制造业,资本密集度绪论全球化对就业的影响是中央当代政治经济问题。

站在发达国家的工人角度看,全球化往往被作为一个威胁,因为传统工业的职位消失或搬迁世界各地(不只是传统的就业机会,最近在印度的呼叫中心的扩大和其他地方的说明)。

另一方面,增加发展中国家的就业被看作是一个重大的贡献,以减少贫困和满足千年发展目标。

但是,全球化对劳动力市场机制的影响,通过其更符合全球经济一体化,可能导致创造就业机会仍然是争议的问题。

其中全球化影响劳工的方式有多种:最重要的通过增加贸易,外国直接投资(FDI)和国际技术转移。

实证研究更多地关注贸易对劳动力市场的影响,而不是外国直接投资的影响效果。

这部分反映了一个事实,虽然贸易对就业的分析相当完善和贸易数据比较容易获得,外国直接投资的分析仍很困难。

虽然创造就业机被政府视为外国直接投资对他们的经济体重要的潜在贡献,大多数分析得出外国直接投资对劳动力市场影响有正反两方面的潜在影响。

表1列出外商直接投资的就业效应主要类型。

外国直接投资对就业水平方面有重大的积极影响。

如果这种投资补充国内投资和涉及新型产业,也增加对劳动力的需求。

外文翻译--FDI和贸易对经济增长的影响:来自发展中国家的实证分析

本科毕业论文外文翻译外文题目:Impact of foreign direct investment and trade on economic growth:evidence from developing countries出处:American Journal of Agricultural Economics, V ol. 86Issue 3作者:Makki, Shiva S.,Somwaru, Agapi原文:IMPACT OF FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT ANDTRADE ON ECONOMIC GROWTH: EVIDENCEFROM DEVELOPING COUNTRIESForeign direct investment (FDI) and trade are often seen as important catalysts for economic growth in the developing countries. FDI is an important vehicle of technology transfer from developed countries to developing countries. FDI also stimulates domestic investment and facilitates improvements in human capital and institutions in the host countries. International trade is also known to be an instrument of economic growth (Romer). Trade facilitates more efficient production of goods and services by shifting production to countries that have comparative advantage in producing Them. Even though past studies show that FDI and trade have a positive impact on economic growth, the size of such impact may vary across countries depending on the level of human capital, domestic investment, infrastructure, macroeconomic stability, and trade policies. The literature continues to debate the role of FDI and trade in economic growth as well as the importance of economic and institutional developments in fostering FDI and trade.This article analyzes the role of FDI and trade in promoting economic growth across selected developing countries and the interaction among FDI, trade, and economic growth. We examine data from sixty-six developing countries over the last three decades. Our resultssuggest that FDI, trade, human capital, and domestic investment are important sources of economic growth for developing countries. We find a strong positive interaction between FDI and trade in advancing economic growth. Our results also show that FDI stimulates domestic investment. The contribution of FDI to economic growth is enhanced by its positive interaction with human capital and sound macroeconomic policies. Methodology and DataOur econometric model is derived from a production function in which the level of a country’s productivity depends on FDI, trade, domestic investment, human capital, and initial gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. The model is based on endogenous growth theory, in the tradition of Balasubramanyam, Salisu, and Sapsford and Borensztein, Gregorio, and Lee, where FDI contributes to economic growth directly through new technologies and other inputs as well as indirectly through improving human capital, infrastructure, and institutions. To assess empirically the effects of FDI and trade on economic growth, we specify the following basic formulation:g=a+b1FDI+b2TRD+b3HC+b4K+b5G0+c1FDI⨯TRD+c2FDI⨯HC+c3FDI⨯K (1)+d1TRI+d2TX+d3GC+ewhere g is the per capita GDP growth rate; TRD, the trade (exports plus imports) of goods and services; HC, the stock of human capital; K, the domestic capital investment; G0, the initial GDP(initial stock); IRT, the inflation rate; TX, the tax on income, profits, and capital gains in the host country expressed as percentage of current revenue; and GC is government consumption. The variables FDI, TRD, K, GC are measured as ratios to GDP. We also account for interaction of FDI with trade and domestic investment, in addition to human capital. Past empirical studies have indicated that FDI, trade, human capital, and domestic investment have a positive impact on economic growth in developing countries. We expect the estimated coefficients for these variables to be positive. We also expect positive interactions between FDI and trade and FDI and domestic capital investment in promoting economic growth.The stock of human capital in a host country is critical for absorbing foreign knowledge and an important determinant of whether potential spillovers will be realized. We postulate not only a positive relationship between FDI and the GDP growth rate but also a positiveinteraction between FDI and human capital in advancing economic growth. The application of advanced technologies embodied in FDI requires a sufficient level of human capital. That is, the higher the level of human capital in a host country, the higher the effect of FDI on the country’s economic growth. One of the key questions regarding FDI and economic growth is: “What is the interaction between FDI and domestic investment”? As argued before, FDI is an important vehicle for the transfer of capital, technology, and knowledge to host countries, thereby generating high-growth opportunities. In practice, however, the growth-enhancing impact of FDI depends critically on the absorptive capacity of a host country and whether FDI “crowds out” its domestic investment. Thus, an important question to be addressed is: “What is the extent to which FDI substitutes for or complements domestic investment”? In our empirical model, we include FDI and domestic investment separately as well as an interaction term between FDI and domestic investment (FDI K). A positive coefficient for the interaction term would suggest that FDI and domestic investment (K) reinforce (complement) each other in advancing economic growth. The initial GDP, measured in terms of constant U.S. dollars, controls for preexisting economic and institutional conditions in the host economy. We expect the initial GDP (expressed in logarithms) to be negatively related with GDP growth rates. The inflation rate is a key indicator of fiscal and monetary policies of a country. A lower inflation rate should mean a better climate for investment, trade, and, therefore, economic growth. Government consumption and tax on income, profits, and capital gains are proxies for institutions and infrastructure in the host countries. Since our objective is to quantify the effects of FDI and trade on economic growth, we focus on developing Countries.Data for our analysis are obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI) database. However, we limit our analysis to 1971 through 2000 because the flow of FDI to most developing countries began in 1970s. All variables represent the average over the following decades: 1971–1980, 1981–1990, and 1991–2000.We estimate a system of three equations, where the dependent variables are the mean values of per capita GDP growth rates in each decade. We estimate the system of equations using the seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) method as well as instrumental variable (three-stage least squares, TSLS) approach. The SUR estimation allows for different error variances in each equation and for correlation of these errors across equations, while theinstrumental variable technique allows us to overcome potential biases induced by endogeneity problems between FDI and economic growth.Empirical ResultsThe purpose of our empirical investigation is to analyze the effects of FDI and trade on economic growth and to examine how FDI interacts with trade, human capital, and domestic investment in advancing economic growth in developing countries. We control for preexisting economic conditions by including initial GDP as one of the explanatory variables. We also account for differences in macroeconomic policies in the host countries by including variables, such as inflation rate, tax burden, and government consumption.Table 1 presents the econometric results. Regressions 1.1, 1.2, and 1.3, different variants of equation (1) above are estimated using the SUR method. Regression 1.1 is our basic specification with explanatory variables of FDI, trade, human capital, domestic investment, and initial GDP. Regression 1.2 extends 1.1 to include interaction of FDI with trade, human capital, and domestic investment. Regression 1.3 builds on regression 1.2 by controlling for inflation rate, tax burden, and government consumption. Our results show that most coefficients have the expected signs, particularly in specification 1.3. The estimated R2 are generally low but reasonable given the cross sectional nature of the data used.Regression 1.1 reveals that FDI and trade have a positive impact on economic growth after controlling for human capital, domestic investment, and initial income. The estimated coefficient for FDI is positive and statistically significant while the estimated coefficient for trade is not statistically significant. Since the coefficient of FDI is larger than the coefficient of trade, it indicates the differential impact of FDI in the host country’s economic growth. The coefficient for human capital is positive, implying that human capital contributes positively to economic growth (significant only at a confidence level of 88%). The coefficients for domestic investment and initial income are not statistically significant. Including interactions between FDI and trade, FDI and human capital, and FDI and domestic investment not only improves the overall performance of the estimation but also allows us tocapture their interaction effects on economic growth.In regression 1.2, the interaction of FDI and trade yields a positive and statistically significant coefficient while the effects of FDI and trade, by themselves, are positive but not statistically significant. Regression 1.2 also reveals that the FDI interacts positively with domestic investment in advancing economic growth. The estimated coefficient for domestic investment is positive and statistically significant at a confidence level of 90%. The estimated coefficients indicate that host countries benefit positively both from FDI, itself, and through FDI’s positive interaction with trade and domestic investment. The interaction between FDI and human capital, although positive, is not statistically significant. Regression 1.3 includes additional variables to control for macroeconomic policies and institutional stability that could have a significant impact on FDI and trade and, thus, on economic growth. Recent literature indicates that FDI is greatly influenced by host country policies, such as monetary, fiscal, and open market policies. We include inflation rates, tax income, and government consumption. The results of regression 1.3 reveal that FDI and trade contribute positively to economic growth, but theestimated coefficients are not statistically significant. The stock of human capital and domestic investment, on the other hand, has positive and statistically significant coefficients. The results also indicate that FDI positively interacts with trade, human capital, and domestic investment. But only FDI trade interaction is statistically significant. This implies that FDI and trade complement each other in advancing growth rate of income in developing countries. This result is consistent with the idea that flow of advanced technology brought along by FDI can increase the growth rate of the host economy by interacting with that country’s trade.The diverse experiences from developing countries suggest that FDI and trade, by themselves, may not guarantee economic growth. A country’s economic growth is also affected by its macroeconomic policies and institutional stability. Sound macroeconomic policies and institutional stability are necessary preconditions for FDI-driven growth to materialize. The estimated coefficients for the three policy variables—inflation rate, government consumption, and tax on income, profits, and capital gains—are negative and statistically significant. This implies that lowering the inflation rate, tax burden, and government consumption would promote economic growth. Lower inflation rates would indicate that the host country’s macroeconomic policies are stable and disciplined. Lower tax burden would make the investments, foreign and domestic, more profitable. Decreasing the government consumption would leave more money for investments.FDI “Crowds-In” Domestic InvestmentOne of the important questions raised in the literature is whether FDI augments a host country’s capital investment or crowds out domestic investment. Even though not statistically significant, the positive interaction between FDI and domestic investment in regression 1.3 implies that domestic investment is unlikely to be crowded out in developing countries. To further strengthen our argument, we estimate the contribution of FDI to domestic investment after controlling for trade, human capital, initial income levels, and various macroeconomic policy variables. Regression 1.4 in table 1 presents the results of this estimation using the SUR method. The results indicate FDI has a positive effect on domestic investment, as the estimated coefficient is positive and statistically significant. This positive relationship implies that FDI stimulates or crowds-in domestic investment. This finding is consistent with Borensztein, Gregorio, and Lee. Even though trade, by itself, is notstatistically significant, trade interacts positively with FDI on domestic investment. The estimated coefficient for the FDI trade interaction term is positive and significant at the 90% confidence level.Endogeneity ProblemsThe correlation between FDI and growth rate could arise from an endogenous determination of FDI. That is, FDI, itself, may be influenced by innovations in the stochastic process governing growth rates (Borensztein, Gregorio, and Lee). For example, market reforms in host countries could increase both GDP growth rates and the inflow of FDI simultaneously. In this case, the presence of correlation between FDI and the country-specific error term would bias the estimated coefficients. The endogeneity problem is addressed by using the instrumental variables. One of the major problems with the instrumental variable estimation method is the difficulty in identifying instruments that are highly correlated with FDI (or trade) but not with the error term. We use lagged values of FDI, lagged values of trade, and log value of total GDP as instruments in a TSLS method. The results of the TSLS model (reported in table 2, regressions 2.1–2.3) show that the instrumental variable estimation yields qualitatively similar results as those obtained by the SUR method. The estimated coefficients on FDI and trade, by themselves, are positive but statistically insignificant. The interactive term of FDI and trade is positive and statistically significant. This alternative estimation also suggests that our results are robust.本科毕业论文外文翻译外文题目:Impact of foreign direct investment and trade on economic growth:evidence from developing countries出处:American Journal of Agricultural Economics, V ol. 86Issue 3作者:Makki, Shiva S.,Somwaru, Agapi译文:FDI和贸易对经济增长的影响:来自发展中国家的实证分析引言在发展中国家FDI和贸易常常被看作刺激经济增长的重要因素。

对外直接投资扩大母国企业间工资差_省略_了吗_基于我国微观数据的经验证据_戚建梅

式 (4) 中, Γ 为一组匹配向量 (即与对外投资企业属性相同但没有对外投资 企业的一些变量) ,这些变量包括:生产率 (用企业总产值与职工总数比值的对数 值表示) 、企业规模 (用企业资产总额对数值表示) 、利润率 (用企业营业利润与销 售额的比值衡量) 、资本密集度 (用企业固定资产与职工总数比值的对数值表示) 、 企业年龄 (用当年年份与开业年份差额加一表示) 等。 其次,对式 (4) 进行估计,即可得到处理组企业的倾向得分 ( p̂ ofdi ) 和控制 组企业的倾向得分 ( p̂ nofdi ) 。 每一个企业,刚好有唯一一个与其对照的非对外投资企业落入集合 Ω 中。 为了有效测度在母国这些有关联企业之间发生的二次技术溢出效应,构建了式

[基金项目]国家社科基金项目“要素价格扭曲对我国出口产品质量影响机理与升级路径研究” (15BJY120) ; 国家统计科学研究项目“大数据背景下我国出口产品质量测度方法改进研究” (2014LY010) 。 戚建梅:对外经济贸易大学国际经贸学院,山东财经大学国际经贸学院;王明益 (通讯作者) :山东财经大 学国际经贸学院 250014 电子信箱:wangmingyi2005@。

①从理论上讲,随着母国企业对外直接投资的开展,受其可支配资源的限制,其母公司的生产规模可能会适当

缩减,因此这时可能会伴随着部分劳动力等要素在国内市场的释放。但这个释放过程一般不会引起工资发生变化。

- 117 -

国际投资与跨国经营

《国际贸易问题》 2017 年第 1 期

这时的母国工资差距与对外直接投资之前并没有发生明显的变化。 随着对外直接投资时间的不断延长,技术外溢效应会逐渐显现,这时对外直接 投资企业会把其学到的先进技术、经营理念等反馈到母公司,从而让母公司相对于 国内其他企业有了较明显的技术、管理优势,这种优势导致本企业工资与其他企业 间有了较明显的差距。随着技术溢出强度的逐渐增强,工资差距会逐渐扩大。与此 同时,母公司较高的工资水平会引发劳动力的转移效应 (即它会吸引国内具有较高 素质的劳动力加入) ,母公司的生产规模持续扩大。在逆向技术溢出和熟练劳动力 大量加入的双重影响下,母公司与其他母国企业迅速拉开了较明显的工资差距,并 且这种差距拉开的速度在加快。 另一方面,随着母公司逐渐掌握并使用较先进的技术或管理经验生产产品,这 个过程也会产生与其存在价值链关联的其他企业间的技术外溢现象,从而会帮助其 他企业提高劳动生产率进而提高其工资水平。因此,在实现了对外直接投资母公司 与其他企业间的技术外溢后,母公司与其他企业间的工资差距会缩小,其缩小的幅 度取决于母公司的逆向技术消化与吸收能力、劳动力转移效应和母国其他企业对母 公司技术二次吸收能力的对比。如果逆向技术溢出效应和劳动力转移效应的作用效 果大于母国其他企业对母公司技术二次吸收能力,则这时工资差距还会扩大,只是 扩大的速度在减慢 (如图 2 中的情形一所示) ;如果逆向技术溢出效应和劳动力转 移效应的作用效果小于母国其他企业对母公司技术的二次吸收能力,则工资差距会 变小 (如图 2 中的情形二所示) 。 由于对外投资国母公司的逆向技术获取在时间上会早于其与当地其他企业间的 技术溢出,所以上述过程对应的工资差距的变化应该遵循“不变—扩大—缩小”或 “不变—扩大—缓慢扩大”的趋势。 根据已有相关研究可知,逆向技术溢出效应和母国其他企业对母公司技术吸收 能力的强弱又与各企业的自身研发水平、技术差距、人力资本及制度等密切相关 (赖明勇等,2005;沈坤荣、李剑,2009) 。据此,提出如下基本理论假设。 理论假设:对外直接投资对母国企业间工资差距存在动态非线性影响 (如图 2 所示) ,母国企业间工资差距是否扩大取决于对外投资母国企业的逆向技术溢出效 应、劳动力转移效应与国内其他企业对技术二次吸收能力的大小。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

本科毕业论文外文翻译 外文题目:Foreign Direct Investment And Host Country Wages:New Evidence From Irish Plant Level Panel Data

出 处: Economics Department, IIIS, Trinity College Dublin No.29 July 2004

作 者: Frances Ruane and Ali Uğur 原 文: Foreign Direct Investment And Host Country Wages:New Evidence From Irish Plant Level Panel Data 1. Introduction The effects on host countries of foreign direct investment (FDI) operating through multinational enterprises (MNEs) are well documented in the literature (see Lipsey (2002) for a recent review). Inter alia, these studies distinguish between the direct and indirect effects of FDI. Direct effects are typically reflected in the capital formation,employment and trade associated with FDI projects. The indirect effects on host economies are seen to arise when, for example, the investments of MNCs generate externalities that enhance the productivity of indigenous firms in the economy. These externalities, which are typically referred to as “positive productivity spillovers”, are seen as helping to improve the competitive advantage of the indigenous sector over time. Recent papers by Görg and Greenaway (2004) and Lipsey (2002) have surveyed this growing literature on FDI spillovers. It has also been argued in the literature, as for example by Aitken, Harrison and Lipsey (1996), that MNEs might have also direct and indirect effects on average manufacturing wages of host countries.The direct effects operate through MNEs paying higher wage levels than those paid by local enterprises (LEs) operating in the same sector and hence raising average wages. The indirect effects arise through the positive effect that the entry or presence of MNEs may have on wages in LEs, that is to say, that wage levels in LEs are higher in sectors where there is a higher presence of MNEs. In this paper we explore the effects of MNEs on wages using panel data on the Irish manufacturing sector for 1991-1999, a period in which the Irish economy experienced exceptionally high rates of economic growth and low unemployment rates relative to other European Union (EU) and OECD countries.Table 1 shows that growth in real Gross Domestic Product(GDP) averaged over six percent in the period 1991-1999 compared to overall growth rates of 1.9 and 2.5 per cent in the EU and OECD countries. This growth in the output levels of the Irish economy has brought down unemployment levels from 15.7 per cent in 1993 to 5.6 per cent in 1999. Table 2 shows that the unemployment level in the Irish economy in 1999 was well below the average rates in EU and OECD countries, having begun the decade substantially higher than their averages. It is widely acknowledged that the manufacturing sector, and especially the MNEs in that sector, was one of the main contributors to this high rate of growth.Total net manufacturing output increased by over 200 per cent in real terms between 1991 and 1999, accompanied by a 26 per cent rise in the employment levels. Ruane and Uğur (2003) show that foreign plants in Irish manufacturing industry accounted for 92 per cent of the growth in net output and 68 per cent of the growth in net employment in Irish manufacturing industry over that period. Table 3 shows that MNEs accounted for 85 percent of total net output and 49 percent of employment in manufacturing in 1999, holding a dominant position in all of the “high-tech” sectors.The sheer scale of the MNE sector in Ireland would lead one to expect it to have a significant impact on average wages. Employment rather than output shares are generally seen a preferred indicator of ownership and sectoral composition in the Irish manufacturing sector, because the low rate of Irish corporate tax is seen as creating incentives for transfer pricing in certain sectors. The objective of this paper is to examine two issues: first, to what extent do MNEspay higher wages than their domestic counterparts, when allowance has been made or plant level differences? Second, are wages in LEs relatively higher in sectors with a greater MNE presence? In examining these issues, the skill composition of the workforces in MNEs and LEs is of critical importance. In describing skill composition, the literature uses a variety of terms to dichotomise the workforce, viz. unskilled/skilled, production/non-production, and blue-collar/white-collar workers; in this paper we use unskilled/skilled. The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses some of the growing literature on wage differences between MNEs and LEs and on the possible indirect impact of MNEs on wages paid by LEs. In Section 3 we examine average wage differentials between foreign and domestic enterprises in Irish manufacturing industry over the 1990s. In Section 4 we outline the general model used to estimate the determinants of wage differentials between MNEs and LEs and describe the data set used. In Section 5 we estimate the model, focussing particularly on the distinction between skilled and unskilled labour. Section 6 looks for evidence that the presence of MNEs in a sector may impact on the wages paid by LEs in that sector, and Section 7 concludes. 2.Wage Differences and the Impact of MNEs on LE Wages Empirical evidence shows that foreign firms tend to pay higher wages than their domestic counterparts both in developing and developed countries. Examples from developed countries include Doms and Jensen (1998) and Feliciano and Lipsey(1999) for the US, Globerman, Ries and Vertinsky (1994) for Canada and Girma, Greenaway and Wakelin(2001) for the UK; all of these studies show that there are wage differences between foreign and domestic firms even after controlling for sector and firms specific factors.We also find that studies on developing countries show similar results; see for example Görg et al. (2002) for Ghana and te Velde and Morrisey (2001)