Testing for superexogeneity of wage equations

motivation in language learning tesol internation

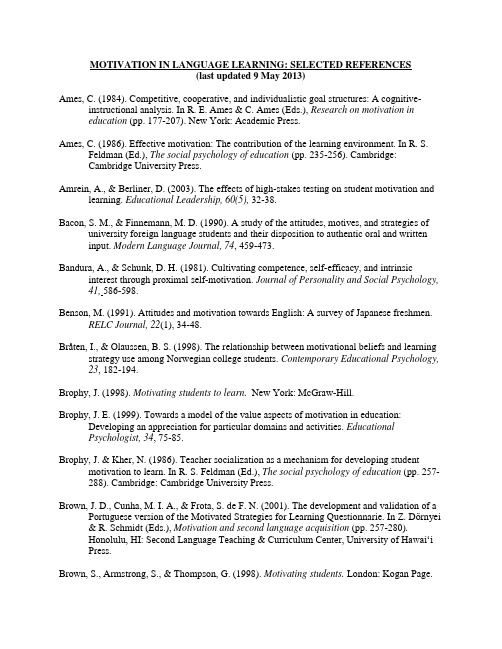

MOTIVATION IN LANGUAGE LEARNING: SELECTED REFERENCES(last updated 9 May 2013)Ames, C. (1984). Competitive, cooperative, and individualistic goal structures: A cognitive-instructional analysis. In R. E. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation ineducation (pp. 177-207). New York: Academic Press.Ames, C. (1986). Effective motivation: The contribution of the learning environment. In R. S.Feldman (Ed.), The social psychology of education (pp. 235-256). Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.Amrein, A., & Berliner, D. (2003). The effects of high-stakes testing on student motivation and learning. Educational Leadership, 60(5), 32-38.Bacon, S. M., & Finnemann, M. D. (1990). A study of the attitudes, motives, and strategies of university foreign language students and their disposition to authentic oral and writteninput. Modern Language Journal, 74, 459-473.Bandura, A., & Schunk, D. H. (1981). Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 586-598.Benson, M. (1991). Attitudes and motivation towards English: A survey of Japanese freshmen.RELC Journal, 22(1), 34-48.Bråten, I., & Olaussen, B. S. (1998). The relationship between motivational beliefs and learning strategy use among Norwegian college students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23, 182-194.Brophy, J. (1998). Motivating students to learn. New York: McGraw-Hill.Brophy, J. E. (1999). Towards a model of the value aspects of motivation in education: Developing an appreciation for particular domains and activities. EducationalPsychologist, 34, 75-85.Brophy, J. & Kher, N. (1986). Teacher socialization as a mechanism for developing student motivation to learn. In R. S. Feldman (Ed.), The social psychology of education (pp. 257-288). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Brown, J. D., Cunha, M. I. A., & Frota, S. de F. N. (2001). The development and validation of a Portuguese version of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnarie. In Z. Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 257-280).Honolulu, HI: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawai‘i Press.Brown, S., Armstrong, S., & Thompson, G. (1998). Motivating students. London: Kogan Page.Chambers, G. (1999). Motivating language learners. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. Cheng, H-F., & Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in language learning and teaching, 1,153-174.Cohen, M., & Dörnyei, Z. (2002). Focus on the language learner: Motivation, styles and strategies. In N. Schmidt (Ed.), An introduction to applied linguistics (pp. 170-190).London, UK: Arnold.Cooper, H., & Tom, D. Y. H. 1984. SES and ethnic differences in achievement motivation. In R.E. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Motivation in education (pp. 209-242). New York:Academic Press.Cranmer, D. (1996). Motivating high level learners. Harlow, UK: Longman.Crookes, G., & Schmidt, R. W. (1991). Motivation: Re-opening the research agenda. Language Learning, 41, 469-512.Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Nakamura, J. (1989). The dynamics of intrinsic motivation: A study of adolescents. In R. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Handbook of motivation theory and research, Vol. 3: Goals and cognitions (pp. 45–71). New York, NY: Academic Press.Csizér, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). Language learners’ motivational profiles and their motivated learning behavior. Language Learning, 55, 613-659.Csizér, K., Kormos, J., & Sarkadi, Á. (2010). The dynamics of language learning attitudes and motivation: Lessons from an interview study of dyslexic language learners. ModernLanguage Journal, 94(3), 470-487.deCharms, R. (1984). Motivation enhancement in educational settings. In R. E. Ames & C.Ames (Eds.), Motivation in education (pp. 275-310). New York: Academic Press. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Perspectives on motivation: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1990 (pp. 237-288). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3 & 4), 325-346.De Volder, M. L., & Lens, W. (1982). Academic achievement and future time perspective as a cognitive-motivational concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 20-33Dörnyei, Z. (1990). Conceptualizing motivation in foreign language learning. Language Learning, 40, 45-78.Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. Modern Language Journal,78, 273-284.Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31, 117-135.Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and researching motivation. Harlow, UK: Longman.Dörnyei, Z. (2002). The motivational basis of language learning tasks. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Individual differences and instructed language learning (pp. 137-158). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.Dörnyei, Z. (2003). Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning: Advances in theory, research, and applications. Language Learning, 53(Supplement 1), 3-32.Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Creating a motivating classroom environment. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International Handbook of English Language Teaching (Vol. 2) (pp. 719-731).New York, NY: Springer.Dörnyei, Z. (2008). New ways of motivating foreign language learners: Generating vision. Links, 38(Winter), 3-4.Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9-42).Tonawanda, NY: MultilingualMatters.Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten commandments for motivating language learners: Results of an empirical study. Language Teaching Research, 2, 203-229.Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (2002). Some dynamics of language attitudes and motivation: Results of a longitudinal nationwide survey. Applied Linguistics, 23, 421-462.Dörnyei, Z., & K. Csizér. (2002). Some dynamics of language attitudes and motivation: Results of a longitudinal nationwide survey. Applied Linguistics, 23, 421–462.Dörnyei, Z., Csizér, K., & Németh, N. (2006). Motivation, language attitudes, and globalization:A Hungarian perspective. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.Dörnyei, Z., & Ottó, I. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 4, 43-69.Dörnyei, Z., & Schmidt, R. (Eds.). (2001). Motivation and second language acquisition.Honolulu: National Foreign Language Resource Center/ University of Hawai'i Press.Dörnyei, Z., & Skehan, P. (2003). Individual differences in second language learning. In C. J.Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 589-630). Malden, MA: Blackwell.Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41, 1040-1048.Ehrman, M. (1996). An exploration of adult language learner motivation, self-efficacy, and anxiety. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation: Pathways to the new century (pp. 81-103). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.Gao, Y., Zhao, Y., Cheng, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2004). Motivation types of Chinese university undergraduates. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 45-64.Gardner, R. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitude and motivation. London, UK: Edward Arnold.Gardner, R. (2001). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. In Z. Dörnyei & R.Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 1-19). Honolulu, HI:University of Hawai’i Press.Gardner, R. C. (2000). Correlation, causation, motivation, and second language acquisition.Canadian Psychology, 41, 10-24.Gardner, R. C. (2001). Integrative motivation: Past, present and future. Retrieved from ://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/GardnerPublicLecture1.pdfGardner, R. (2001). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. In Z. Dörnyei & R.Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 1-19). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.Gardner, R. C. (2005). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. Retrieved from ://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/caaltalk5final.pdfGardner, R. C. (2009). Gardner and Lambert (1959): Fifty years and counting. Retrieved from ://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/CAALOttawa2009talkc.pdfGardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1959). Motivational variables in second language acquisition.Canadian Journal of Psychology, 13, 266-272.Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.Gardner, R. C., Masgoret, A.-M., Tennant, J., & Mihic, L. (2004). Integrative motivation: Changes during a year-long intermediate-level language course. Language Learning, 54, 1-34.Gardner, R. C., & Smythe, P. C. (1981). On the development of the attitude/ motivation test battery. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 37, 510-525.Gardner, R. C., & Tremblay, P. F. (1994). On motivation, research agendas, and theoretical frameworks. The Modern Language Journal, 78, 359-368.Grabe, W. (2009). Motivation and reading. In W. Grabe (Ed.), Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice (pp. 175-193). New York, NY: Cambridge UniversityPress.Graham, S. (1994). Classroom motivation from an attitudinal perspective. In H. F. J. O'Neil and M. Drillings (Eds.), Motivation: Theory and research (pp. 31-48). Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum.Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOLQuarterly, 42, 55-77.Hadfield, J. (2013). A second self: Translating motivation theory into practice. In T. Pattison (Ed.), IATEFL 2012: Glasgow Conference Selections (pp. 44-47). Canterbury, UK:IATEFL.Hao, M., Liu, M., & Hao, R. (2004). An empirical study on anxiety and motivation in English asa Foreign Language. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 89-104.Hara, C., & Sarver, W. T. (2010). Magic in ESL: An observation of student motivation in an ESL class. In G. Park, H. P. Widodo, & A. Cirocki (Eds.), Observation of teaching:Bridging theory and practice through research on teaching (pp. 141-153). Munich,Germany: LINCOM EUROPA.Hashimoto, Y. (2002). Motivation and willingness to communicate as predictors of reported L2 use: The Japanese ESL context. Retrieved from :///sls/uhwpesl/20(2)/Hashimoto.pdf.Hawkins, J. N. (1994). Issues of motivation in Asian education. In H. F. O’Neill & M. Drillings (Eds.), Motivation—theory and research (pp. 101-115). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Hsieh, P. (2008). Why are college foreign language students' self-efficacy, attitude, and motivation so different? International Education, 38(1), 76-94.Huang, S. (2010). Convergent vs. divergent assessment: Impact on college EFL students’ motivation and self-regulated learning strategies. Language Testing, 28(2), 251-270.Keller, J. M. (1983). Motivational design of instruction. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional design theories and models (pp. 386-433). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Kim, S. (2009). Questioning the stability of foreign language classroom anxiety and motivation across different classroom contexts. Foreign Language Annals, 42(1), 138-157. Komiyama, R. (2009). CAR: A means for motivating students to read. English Teaching Forum, 47(3), 32-37.Kondo-Brown, K. (2001). Bilingual heritage students’ language contact and motivation. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 433-460).Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.Koromilas, K. (2011). Obligation and motivation. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 44, 12-20.Lamb, M. (2004). Integrative motivation in a globalizing world. System, 32, 3-19.Lamb, T. (2009). Controlling learning: Learners’ voices and relationships between motivation and learner autonomy. In R. Pemberton, S. Toogood, & A. Barfield (Eds.), Maintaining control: Autonomy and language learning (pp. 67-86). Hong Kong: Hong KongUniversity Press.Lau, K.-l., & Chan, D. W. (2003). Reading strategy use and motivation among Chinese good and poor readers in Hong Kong. Journal of Research in Reading, 26, 177-190.Lepper, M. R. (1983). Extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation: implications for the classroom.In J. M. Levine & M. C. Wang (eds.), Teacher and student perceptions: implications for learning (pp. 281-317). Hillsdale, NJ; Erlbaum.Li, J. (2009). Motivational force and imagined community in ‘Crazy English.’ In J. Lo Bianco, J.Orton, & Y. Gao (Eds.), China and English: Globalisation and the dilemmas of identity(pp. 211-223). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.Lopez., F. (2010).Identity and motivation among Hispanic ELLs. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 18(16), 1-29.MacIntyre, P. D. (2002). Motivation, anxiety and emotion in second language acquisition. In P.Robinson (Ed.), Individual differences and instructed language learning (pp. 45-68).Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.MacIntyre, P. D., MacMaster, K., & Baker, S. C. (2001). The convergence of multiple models of motivation for second language learning: Gardner, Pintrich, Kuhl, and McCroskey. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 461-492).Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.Maehr, M. L. & Archer, J. (1987). Motivation and school achievement. In L. G. Katz (ed.), Current topics in early childhood education (pp. 85-107). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.Manderlink, G., & Harackiewicz, J. M. 1984. Proximal versus distal goal setting and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 918-928.Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224-253.Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper & Row.McCombs, B. L. (1984). Processes and skills underlying continued motivation to learn.Educational Psychologist, 19(4), 199-218.McCombs, B. L. (1988). Motivational skills training: combining metacognitive, cognitive, and affective learning strategies. In C. E. Weinstein, E. T. Goetz & P. A. Alexander (Eds.),Learning and study strategies (pp.141-169). New York: Academic Press.McCombs, B. L. (1994). Strategies for assessing and enhancing motivation: keys to promoting self-regulated learning and performance. In H. F. O’Neill & M. Drillings (Eds.),Motivation: theory and research (pp. 49-69). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.McCombs, B. L., & Whisler, J. S. (1997). The learner-centered classroom and school: Strategies for increasing student motivation and achievement. San Francisco. CA:Jossey-Bass.McCrossan, L. (2011). Progress, motivation and high-level learners. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 44, 6-12.Melvin, B. S., & Stout, D. S. (1987). Motivating language learners through authentic materials.In W. Rivers (Ed.), Interactive language teaching (pp. 44–56). New York, NY:Cambridge University Press.Midraj, S., Midraj, J., O’Neil, G., Sellami, A., & El-Temtamy, O. (2007). UAE grade 12 students’ motivation & language learning. In S. Midraj, A. Jendli, & A. Sellami (Eds.), Research in ELT contexts (pp. 47-62). Dubai: TESOL Arabia.Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2000). Meaning and motivation. In C. Sansone & J.Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimalmotivation and performance (pp. 131-159). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.Mori, S. (2002). Redefining motivation to read in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14, 91-110.Noels, K. A., Clément, R., & Pelletier, L. G. (1999). Perceptions of teachers’ communicative style and students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.Modern Language Journal,83, 23-34.Noels, K. A., Pelletier, L. G., Clément, R., & Vallerand, R. J. (2000). Why are you learning a second language?: Motivational orientations and self-determination theory. LanguageLearning, 50, 57-85.Oxford, R. L. (Ed.). (1996). Language learning motivation: pathways to the new century.Hono lulu: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawai’i.Oxford, R., & Shearin, J. (1994). Language learning motivation: Expanding the theoretical framework. Modern Language Journal, 78, 12-28.Papadimitriou, A. D. (2011). The impact of an extensive reading programme on vocabulary development and motivation. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 44, 39-47.Paris, S. C., & Turner, J. C. (1994). Situated motivation. In P. R. Pintrich, D. R. Brown, & C. E.Weinstein (Eds.), Student motivation, cognition, and learning (pp. 213-237). Hillsdale,NJ: Erlbaum.Peacock, M. (1997). The effect of authentic materials on the motivation of EFL learners. ELT Journal, 51(2), 144-156.Pedraza, P., & Ayala, J. (1996). Motivation as an emergent issue in an after-school program in El Barrio. In L. Schauble & R. Glaser (Eds.), Innovations in learning (pp. 75-91). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Pintrich, P. R. (1999). The role of motivation in promoting and sustaining self-regulated learning.International Journal of Educational Research, 31(6), 459-470.Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of educational psychology, 82(1), 33.Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (1996). Motivation in education: Theory, research and applications. Englewood Cliffs: NJ: Prentice-Hall.Ramage, K. (1991). Motivational factors and persistence in second language learning. Language Learning, 40(2), 189-219.Rueda, R., & Moll, L. (1994). A sociocultural perspective on motivation. In H. F. O’Neill & M.Drillings (Eds.), Motivation: theory and research (pp. 117-137). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology,25, 54-67.Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78. Schmidt, R., Boraie, D., & Kassabgy, O. (1996). Foreign language motivation: Internal structure and external connections. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation:Pathways to the new century (pp. 9-70). Honolulu: Second Language Teaching &Curriculum Center, University of Hawaii Press.Schutz, P. A. (1994). Goals as the transaction point between motivation and cognition. In P. R.Pintrich, D. R. Brown, & C. E. Weinstein (Eds.), Student motivation, cognition, andlearning (pp. 135-156). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Scott, K. (2006). Gender differences in motivation to learn French. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 62, 401-422.Syed, Z. (2001). Notions of self in foreign language learning: A qualitative analysis. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 127-147).Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.Schmidt, R., Boraie, D., & Kassabgy, O. (1996). Foreign language motivation: Internal structure and external connections. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation: Pathways to the new century (pp. 9-70). Honolulu, HI: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawaii Press.Scott, K. (2006). Gender differences in motivation to learn French. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 62, 401-422.Sisamakis, M. (2010). The motivational potential of the European language portfolio. In B.O’Rourke & L. Carson (Eds.), Language learner autonomy: Policy, curriculum,classroom (pp. 351-371). Oxford, UK: Peter Lang.Smith, K. (2006). Motivating students through assessment. In R. Wilkinson, V. Zegers, & C. van Leeuwen (Eds.), Bridging the assessment gap in English-medium higher education (pp.109-121). Nijmegen, The Netherlands: AKS –Verlag.St. John, J. (2007). Motivation: The teachers’ perspective. In S. Midraj, A. Jendli, & A. Sellami (Eds.), Research in ELT contexts (pp. 63-84). Dubai: TESOL Arabia.Syed, Z. (2001). Notions of self in foreign language learning: a qualitative analysis. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt, (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 127-148).Honolulu: National Foreign Language Resource Center/ University of Hawai'iPress.Ushioda, E. (2003). Motivation as a socially mediated process. In D. Little, J. Ridley, & E.Ushioda (Eds.), Learner autonomy in the language classroom (pp. 90-102). Dublin,Ireland: Authentik.Ushioda, E. (2008). Motivation and good language learners. In C. Griffiths (Ed.), Lessons from good language learners (pp. 19-34). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Ushioda, E. (2009). A person-in-context relational view of emergent motivation, self and identity.In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp.215-228). Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters.Ushioda, E. (2012). Motivation. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to pedagogy and practice in language teahcing (pp. 77-85). Cambridge, UK: CambridgeUniversity Press.Verhoeven, L., & Snow, C. E. (Eds.). (2001). Literacy and motivation: Reading engagement in individuals and groups. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Wachob, P. (2006). Methods and materials for motivation and learner autonomy. Reflections on English Language Teaching, 5(1), 93-122.Walker, C. J., & Quinn, J. W. (1996). Fostering instructional vitality and motivation. In R. J.Menges and associates, Teaching on solid ground (pp. 315-336). San Francisco, SF:Jossey-Bass.Warden, C. A., & Lin, H. J. (2000). Existence of integrative motivation in an Asian EFL setting.Foreign Language Annals, 33, 535-547.Weiner, B. (1984). Principles for a theory of student motivation and their application within an attributional framework. In R. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation ineducation (pp. 15-38). New York: Academic Press.Weiner, B. (1992). Human motivation: Metaphors, theories and research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Weiner, B. (1994). Integrating social and personal theories of achievement motivation. Review of Educational Research, 64, 557-573.Williams, M., Burden, R., & Lanvers, U. (2002). French is the language of love and stuff: Student perceptions of issues related to motivation in learning a foreign language.British Educational Research Journal, 28, 503–528.Wlodkowski, R. J. (1985). Enhancing adult motivation to learn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Wu, X. (2003). Intrinsic motivation and young language learners: The impact of the classroom environment. System, 31, 501-517.Xu, H., & Jiang, X. (2004). Achievement motivation, attributional beliefs, and EFL learning strategy use in China. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 65-87.Yung, K. W. H. (2103). Bridging the gap: Motivation in year one EAP classrooms. Hong Kong Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14(2), 83-95.。

面板数据模型的检验方法研究优秀毕业论文

-

I尹

学位论文作者签名:隐蠡墨 签字日期:卅一年歹月旷日

0

学位论文版权使用授权书

本学位论文作者完全了解天津大学 有关保留、使用学位论文的规定。

特授权天津大学可以将学位论文的全部或部分内容编入有关数据库进行检

索,并采用影印、缩印或扫描等复制手段保存、汇编以供查阅和借阅。同意学校 向国家有关部门或机构送交论文的复印件和磁盘。

N or T is relatively large;and unit root tests in panel data with trend shift are

●

uneffective and will lead to spurious result in most cases.They show that neglect of

theory and method of panel heteroskedasticity and serial dependence tests,panel unit

root tests and panel cointegration tests,and to perfect and expand the tests in panel

卜

structural breaks will iead to test failure.

、

(3)This paper proposes a LSTR-IPS panel data unit root test with structural

change,by modifying the traditional IPS unit test with nonlinear smooth transition

(4)Taking into account the progressive nature and smooth asymptotic

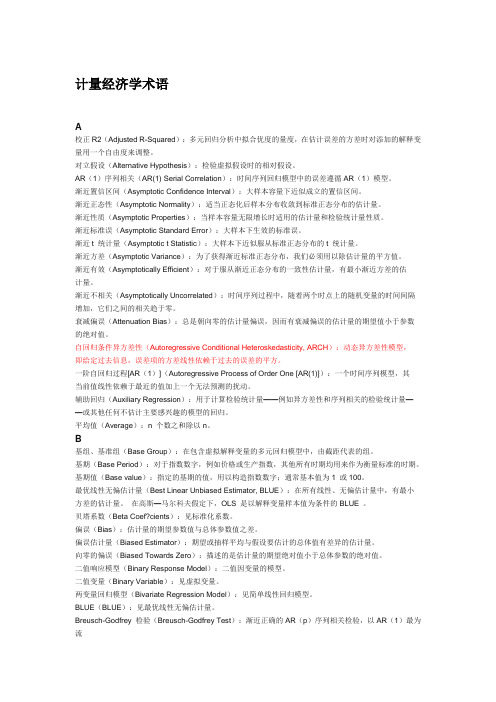

英汉对照计量经济学术语

计量经济学术语A校正R2(Adjusted R-Squared):多元回归分析中拟合优度的量度,在估计误差的方差时对添加的解释变量用一个自由度来调整。

对立假设(Alternative Hypothesis):检验虚拟假设时的相对假设。

AR(1)序列相关(AR(1) Serial Correlation):时间序列回归模型中的误差遵循AR(1)模型。

渐近置信区间(Asymptotic Confidence Interval):大样本容量下近似成立的置信区间。

渐近正态性(Asymptotic Normality):适当正态化后样本分布收敛到标准正态分布的估计量。

渐近性质(Asymptotic Properties):当样本容量无限增长时适用的估计量和检验统计量性质。

渐近标准误(Asymptotic Standard Error):大样本下生效的标准误。

渐近t 统计量(Asymptotic t Statistic):大样本下近似服从标准正态分布的t 统计量。

渐近方差(Asymptotic Variance):为了获得渐近标准正态分布,我们必须用以除估计量的平方值。

渐近有效(Asymptotically Efficient):对于服从渐近正态分布的一致性估计量,有最小渐近方差的估计量。

渐近不相关(Asymptotically Uncorrelated):时间序列过程中,随着两个时点上的随机变量的时间间隔增加,它们之间的相关趋于零。

衰减偏误(Attenuation Bias):总是朝向零的估计量偏误,因而有衰减偏误的估计量的期望值小于参数的绝对值。

自回归条件异方差性(Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity, ARCH):动态异方差性模型,即给定过去信息,误差项的方差线性依赖于过去的误差的平方。

一阶自回归过程[AR(1)](Autoregressive Process of Order One [AR(1)]):一个时间序列模型,其当前值线性依赖于最近的值加上一个无法预测的扰动。

计量经济学论文-薪资微观影响因素的计量分析

计量经济学课程论文某国薪资影响因素的计量分析[摘要]本文主要运用OLS,采取数据对工人工资的微观因素分析。

由此得出影响薪资最主要的因素是工作经验,以帮助大学生在择业就业时了解自己的优势劣势,及时增强自己的能力,增加工作经验,以求在职场中获得更高薪资和更好的表现。

AbstractThis paper mainly uses the OLS,take the analysis of data on the micro factors workers wages. Conclusion the main influence factors of salary is working experience,to help students understand their own advantages and disadvantages in the employment,to enhance their ability,work experience,in order to get higher pay and better performance in the workplace[关键词]薪资影响因素回归分析一.引言我国大学扩招后,大学生就业难的问题已经是一个不争的现象,且有可能越来越难的趋势。

这个方面和国际经济形式近3年来连遭打击,一方面和中国经济结构体制和教育改革落后有关,更和当今大学生的就业观滞后有关。

据统计,2013年全国高校毕业生将超过700万,这些高校学子的就业问题成为社会和学校关注的焦点。

那么我们通常关注的工作的薪水受自身的什么因素的影响呢?就此问题我搜集了关于薪水影响因素的数据,并且运用Eviews3.0进行多元回归分析。

二、数据搜集本文所采用数据均来自于薛薇-《基于SPSS的数据分析Employee data》,真实性和权威性很高。

三、计量经济模型(一)模型的建立Y=β1+β2X2+β3X3+β4X4+β5X5+β6X6+β7X7++β8X8+U其中:Y现在薪资(美元/年), X2—性别 X3—教育程度 X4—年龄 X5—初始工作工资 X6—工作时间 X7—工作经验 X8—行业类别 U—随机扰动项X2—性别,1代表男性,2代表女性(虚拟变量)X3—教育程度,以年为单位,表示学习时间的长短X7—工作经验,以月为单位,表示过去工作的时间长短X6—工作时间,从被雇佣开始工作的时间X8—行业类别,1表示管理者,2表示非管理者(虚拟变量)Dependent Variable: YMethod: Least SquaresDate: 11/03/13 Time: 15:36Sample: 1 471Included observations: 470ent Error1X3 331.597159.6873 2.076540 0.0384X4 -84.1361348.88423 -1.721130 0.0859X5 1.3351280.074393 17.94707 0.0000 X6 151.858332.57934 4.661185 0.0000X7 -9.137088 5.630314 -1.6228380.1053X8 11488.071393.907 8.241631 0.0000C -3936.153577.955 -1.100112 0.27199 dependent varAdjusted R-squared 0.835717S.D. dependentvar17119.69S.E. of regression 6938.926Akaike infocriterion20.54456Sum squared resid 2.22E+1Schwarzcriterion20.61524Log likelihood -4819.971F-statistic 341.8326Durbin-Watson stat 1.888283Prob(F-statistic) 0.000000由上表,模型估计有以下结果Y=-3936.150+2384.251X2+331.5970X3-84.13613X4+1.335128X5+151.8 583X6-9.137088X7+11488.07X8+Use=(3577.955)(784.8212) (159.6873)(48.88423) (0.074393) (32.57934) (5.630314)(1393.907)t=(-1.100112)(3.037955) (2.076540) (-1.721130) (17.94707) (4.661185) (-1.622838)(8.241631)R2=0.838169Adjusted R2=0.835717F-statistic=341.8326,n=471(二)参数估计的检验与修正由上表,该模型的可决系数较高,F检验值=341.8326,明显显著。

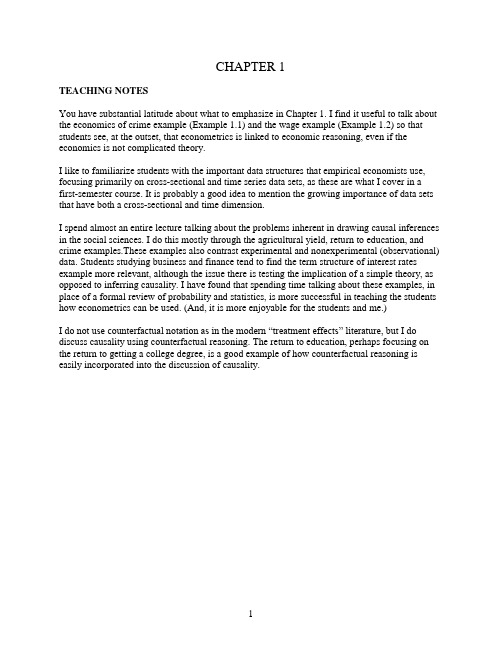

伍德里奇计量经济学第六版答案Chapter 1

CHAPTER 1TEACHING NOTESYou have substantial latitude about what to emphasize in Chapter 1. I find it useful to talk about the economics of crime example (Example 1.1) and the wage example (Example 1.2) so that students see, at the outset, that econometrics is linked to economic reasoning, even if the economics is not complicated theory.I like to familiarize students with the important data structures that empirical economists use, focusing primarily on cross-sectional and time series data sets, as these are what I cover in a first-semester course. It is probably a good idea to mention the growing importance of data sets that have both a cross-sectional and time dimension.I spend almost an entire lecture talking about the problems inherent in drawing causal inferences in the social sciences. I do this mostly through the agricultural yield, return to education, and crime examples.These examples also contrast experimental and nonexperimental (observational) data. Students studying business and finance tend to find the term structure of interest rates example more relevant, although the issue there is testing the implication of a simple theory, as opposed to inferring causality. I have found that spending time talking about these examples, in place of a formal review of probability and statistics, is more successful in teaching the students how econometrics can be used. (And, it is more enjoyable for the students and me.)I do not use counterfactual notation as in the modern “treatment effects” literature, but I do discuss causality using counterfactual reasoning. The return to education, perhaps focusing on the return to getting a college degree, is a good example of how counterfactual reasoning is easily incorporated into the discussion of causality.SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS1.1 (i) Ideally, we could randomly assign students to classes of different sizes. That is, each student is assigned a different class size without regard to any student characteristics such as ability and family background. For reasons we will see in Chapter 2, we would like substantial variation in class sizes (subject, of course, to ethical considerations and resource constraints).(ii) A negative correlation means that larger class size is associated with lower performance. We might find a negative correlation because larger class size actually hurts performance. However, with observational data, there are other reasons we might find a negative relationship. For example, children from more affluent families might be more likely to attend schools with smaller class sizes, and affluent children generally score better on standardized tests. Another possibility is that, within a school, a principal might assign the better students to smaller classes. Or, some parents might insist their children are in the smaller classes, and these same parents tend to be more involved in thei r children’s education.(iii) Given the potential for confounding factors – some of which are listed in (ii) – finding a negative correlation would not be strong evidence that smaller class sizes actually lead to better performance. Some way of controlling for the confounding factors is needed, and this is the subject of multiple regression analysis.1.2 (i) Here is one way to pose the question: If two firms, say A and B, are identical in all respects except that firm A supplies job training one hour per worker more than firm B, by how much would firm A’s output differ from firm B’s?(ii) Firms are likely to choose job training depending on the characteristics of workers. Some observed characteristics are years of schooling, years in the workforce, and experience in a particular job. Firms might even discriminate based on age, gender, or race. Perhaps firms choose to offer training to more or less able workers, where “ability” might be difficult to quantify but where a manager has some idea about the relative abilities of different employees. Moreover, different kinds of workers might be attracted to firms that offer more job training on average, and this might not be evident to employers.(iii) The amount of capital and technology available to workers would also affect output. So, two firms with exactly the same kinds of employees would generally have different outputs if they use different amounts of capital or technology. The quality of managers would also have an effect.(iv) No, unless the amount of training is randomly assigned. The many factors listed in parts (ii) and (iii) can contribute to finding a positive correlation between output and training even if job training does not improve worker productivity.1.3 It does not make sense to pose the question in terms of causality. Economists would assume that students choose a mix of studying and working (and other activities, such as attending class, leisure, and sleeping) based on rational behavior, such as maximizing utility subject to the constraint that there are only 168 hours in a week. We can then use statistical methods to。

计量经济学实验课程内容

计量经济学实验课程内容一.一.EViews 基本操作1.1.启动Eviews双击Eviews图标,出现Eviews窗口,它由以下部分组成:标题栏“Eviews”、主菜单“File,Edit,…,Help”、命令窗口(空白处)和工作区域。

2.产生文件Eviews的操作在工作文件中进行,故首先要有工作文件,然后进行数据输入、分析等等操作。

(1)(1)读已存在文件:File/Open/Workfile。

(2)(2)新建文件:File/New/Workfile,出现对话框“工作文件范围”,选取或填上数据类型、起止时间。

OK后,得到一个无名字的工作文件,其中有:时间范围、当前工作文件样本范围、filter 、默认方程、系数向量C、序列RESID。

3.输入数据(1)(1)从键盘输入:Quick/Empty Group (Edit Series),打开组窗口,产生一个untitled“Group”;按列在表中输入序列名(在OBS)及其数据,每输入一个数据完,敲一次enter。

(2)(2)从Excel复制数据:先取定Excel中的数据区域,选“复制”;其次,打开Eview,同2-(2),建工作文件,使样本区域包含与被复制数据同样多的观察值个数;第三,击Quick/Empty Group (Edit series);第四,按向上滚动指针,击数据区OBS右边的单元格,点Edit/Paste,再退出,选No,于是,在工作文件中有被复制的数据序列的图标。

(3)(3)从Excel复制部分数据到已存在的序列中:取定要复制的数据,复制之;打开包含已存在序列的Group窗口,使之处于Edit模式(开关键是Edit+);将光标指到目标单元格,点Edit/Paste,其它同3-(2)。

4.从Excel工作表中读取数据击Procs/Import/Read-Lotus-Excel,选取文件类型为Text-ASCII或Excel.xls,打开文件;在对话框中,选取要打开的序列名,多个之间用空格隔开(如全用原序列名,输入序列的个数即可),OK。

2014年高级计量经济学复习

2012级博士高级计量经济学复习面板数据模型与非面板数据模型在多处具有相似性。

在面板数据模型的模型设定中,需要考虑以下的主要问题:1.模型设定问题(1)平稳性问题(包括LLC、IPS检验法的基本原理,检验结果的读解);(2)“斜率”系数问题(变斜率系数与不变斜率系数的检验方法以及基本原理,检验结果的读解);(3)“维数”问题(两维截距、一维截距的检验方法以及基本原理,检验结果的读解);(4)“截距”系数问题(包括FEFE、RERE、FERE、REFE、FE0、0FE、RE0、0RE、pool等的检验方法以及基本原理,检验结果的读解);(5)检验的策略2.估计问题(只涉及平稳数据的估计问题)(1)一维情形下的估计问题(包括FE和RE的估计方法以及基本原理,估计结果的读解);(2)两维情形下的估计问题(包括FEFE、RERE、FERE和REFE的估计方法以及基本原理,估计结果的读解)3. 检验问题(1)F检验的应用前提条件(2)异方差性的检验(组内、组间以及总体方差的异方差性的检验方法以及基本原理,检验结果的读解);(3)自相关性的检验(组内、组间以及总体的自相关性的检验方法以及基本原理,检验结果的读解);(4)检验的策略与基本步骤微观部分二元选择模型(1)概率基础 (2)模型设定 (3)模型结果读解 有序选择模型 (1)模型设定 (2)模型结果读解例题(微观部分) 1. 设有()()()1|~1Prob y X e eΦ⎧⎪==⎨Λ⎪+⎩X βX βX βX β (1)(4分)试推导Logit 模型关于X 的边际效应;(2)(4分)有人得到以下实证分析结果,请对结果给出自己的解释; (3)(4分)计算实证分析中解释变量GPA 和TUCE 的边际效应; (4)(4分)试对如下结果中LR statistic (3 df)= 15.54585的含义进行解释。

Dependent Variable: GRADE Method: ML - Binary Probit (Quadratic hill climbing) Date: 08/12/09 Time: 23:15 Sample: 1 32 Included observations: 32 Convergence achieved after 5 iterations C -7.452320 2.542472 -2.931132 0.0034 GPA 1.625810 0.693882 2.343063 0.0191 TUCE 0.051729 0.083890 0.616626 0.5375 PSI 1.426332 0.595038 2.397045 0.0165Mean dependent var 0.343750 S.D. dependent var 0.482559 S.E. of regression 0.386128 Akaike info criterion 1.051175 Sum squared resid 4.174660 Schwarz criterion 1.234392 Log likelihood -12.81880 Hannan-Quinn criter. 1.111906 Restr. log likelihood -20.59173 Avg. log likelihood -0.400588 LR statistic (3 df) 15.54585 McFadden R-squared 0.377478Probability(LR stat) 0.001405Obs with Dep=0 21 Total obs 32 Obs with Dep=1 11()0.328f X β= 答案The logit model or logistic regression model specifies()()1TT TTe p F e==Λ=+xβx βx βx β (1)where ()Λ⋅is the logistic cdf, with ()111e e e-Λ==++z z zz . Logit 模型的边际效应()()()()()Pr 1||Ti i T iF y E y f ∂∂=∂===∂∂∂βx x x βx βx x x()()()()()()()22111TT T T T TT T T TT e d e dF d e e d d d e e⎛⎫⎪ ⎪Λ+⎝⎭===-++βxβx βx βx βx βx βx βx βx βx βx ()()()1111TTT T T T e e ee ⎛⎫=-=Λ-Λ ⎪ ⎪++⎝⎭βx βxβxβx βx βx ()()()()()()()|1T TT TT F dF E y d ⎛⎫∂∂ ⎪===Λ-Λ ⎪∂∂⎝⎭βx βx x ββx βx βx xβx Probit 模型的边际效应()()()()|T Ti T i iF E y φ∂∂Φ∂===∂∂∂βx βx x βx βx x x 故有:GPA1.625810 0.5333 TUCE 0.051729 0.01697 PSI1.426332 0.4678LR statistic (3 df)= 15.54585的含义是对Probit/Logit 模型中所有的斜率系数均等于0的假设进行检验。

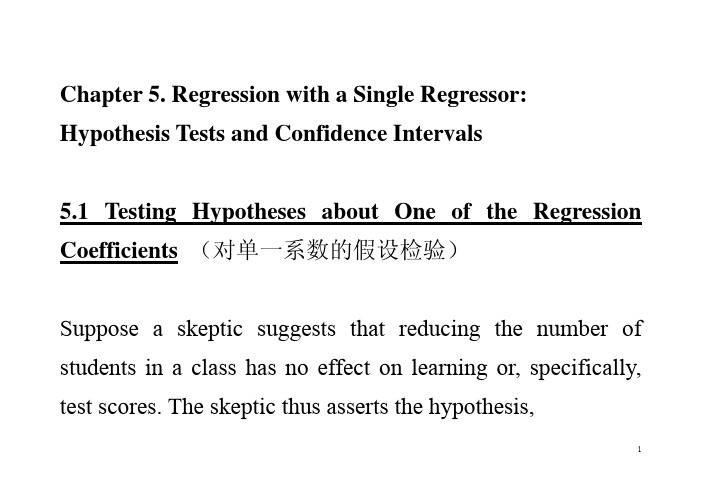

斯托克、沃森着《计量经济学》第五章

Chapter 5. Regression with a Single Regressor: Hypothesis Tests and Confidence Intervals5.1 Testing Hypotheses about One of the Regression Coefficients(对单一系数的假设检验)Suppose a skeptic suggests that reducing the number of students in a class has no effect on learning or, specifically, test scores. The skeptic thus asserts the hypothesis,1H0: β1 = 0We wish to test this hypothesis using data – reach a tentative conclusion whether it is correct or incorrect.Null hypothesis and two-sided alternative:H0: β1 = 0 vs. H1: β1≠ 0or, more generally,2H0: β1 = β1,0 vs. H1: β1≠β1,0where β1,0 is the hypothesized value under the null(β1,0是一个具体的数).Null hypothesis and one-sided alternative:H0: β1 = β1,0 vs. H1: β1 < β1,0In economics, it is almost always possible to come up with stories in which an effect could “go either way,” so it is34standard to focus on two-sided alternatives.Recall hypothesis testing for population mean using Y :t=Y μ−then reject the null hypothesis if |t | >1.96.where the SE of the estimator is the square root of an estimator of the variance of the estimator.Applied to a hypothesis about β1:t = estimator - hypothesized value standard error of the estimator56sot = 11,01ˆˆ()SE βββ−where β1 is the value of β1,0 hypothesized under the null (for example, if the null value is zero, then β1,0 = 0.What is SE (1ˆβ)? SE (1ˆβ) = the square root of an estimator of the variance7of the sampling distribution of 1ˆβRecall the expression for the variance of 1ˆβ (large n ):var(1ˆβ) = 22var[()]()i X i X X u n μσ− = 24v Xn σσwhere v i = (X i –X )u i . Estimator of the variance of 1ˆβ:812ˆˆβσ = 2221estimator of (estimator of )v Xn σσ× = 2212211ˆ()121()ni i i n i i X X u n n X X n ==−−×⎡⎤−⎢⎥⎣⎦∑∑.OK, this is a bit nasty, but:• There is no reason to memorize this• It is computed automatically by regression software• SE (1ˆβis reported by regression software9• It is less complicated than it seems. The numerator estimates the var(v ), the denominator estimates var(X )2.Return to calculation of the t -statsitic:t = 11,01ˆˆ()SE βββ− =11,0ˆββ−• Reject at 5% significance level if |t| > 1.96•p-value is p = P(|t| > |t act|) = probability in tails of normal outside |t act|•Both the previous statements are based on large-n approximation; typically n = 50 is large enough for the approximation to be excellent.1011 Example: Test Scores and STR , California dataEstimated regression line: n TestScore = 698.9 – 2.28×STRRegression software reports the standard errors:SE (0ˆβ) = 10.4 SE (1ˆβ) = 0.52t -statistic testing “β1,0 = 0” = 11,01ˆˆ()SE βββ− = 2.2800.52−− = –4.38•The 1% 2-sided significance level is 2.58, so we reject the null at the 1% significance level.•Alternatively, we can compute the p-value. You can do this easily in Stata:. di normal(-4.38)*2. 00001187注:在Stata中,normal表示标准正态分布的cdf。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

AppliedEconomics,1996,28,663—672Testingforsuperexogeneityofwageequations

GUGLIELMOMARIACAPORALECentreforEconomicForecasting,¸ondonBusinessSchool,SussexPlace,Regent’sPark,¸ondonNW14SA,ºK

ThesuperexogeneityofwageequationsistestedinfourmajorEuropeancountries.Thisisanimportantissuebecausewhileonlyweakexogeneityisneededforestima-tionpurposesandfortesting,andstrongexogeneityforforecasting,superexogeneityisrequiredforpolicyanalysis.TheproceduresuggestedbyEngleandHendry(1993)isadoptedtocarryouttheempiricalanalysis.Inallcasestheconditionalmodelisnotaffectedbythefirstandsecondmomentsoftheresidualsfromthemarginalmodels.ThisinvarianceresultimpliesthattheestimatedlinearregressionmodelsarenotsubjecttotheLucascritiqueovertheperiodexamined.Differencesinwagedeter-minationbetweenthevariouscountriescanbeplausiblyinterpretedasresultingfromthebargainingenvironment.

I.INTRODUCTIONTestsforthesuperexogeneityofwageequationsarecarriedoutforfourmajorEuropeancountries.Thisisanimportantissuebecause,asiswellknown,whileonlyweakexogeneityisneededforestimationpurposesandfortesting,andstrongexogeneityforforecasting,superexogeneityisrequiredforpolicyanalysis.AfterreviewinginSectionIItherelevanteconometricandstatisticaltheoryanddefiningthecon-ceptofexogeneity,theproceduresuggestedbyEngleandHendry(1993)isadoptedinSectionIIItocarryouttheempiricalanalysis.Theresultsindicatethatthe‘Lucascri-tique’isnotapplicableinthecaseofthewageequation,andthatitmaynotberelevanttotheproblemofmodellingwagedetermination,inthesensethattheeconometricequa-tionsremainconstantinresponsetochangesinthecondi-tioningprocess.Differencesinwagedeterminationbetweenthevariouscountriesarethenplausiblyinterpretedasre-sultingfromthebargainingenvironment.Concludingre-marksfollowinSectionIV.Inhisinfluential1976study,Lucasmadeitclearthat,iftheeconomycanbecharacterizedadequatelyasastochasticdynamicenvironmentwithoptimizingagents,thenitispossiblethattheparametersofanestimatedmacro-econometricmodelwillnotbeinvarianttochangeseitherintheexpectations-generatingmechanismsorinpolicyrules.Sincethen,anumberofstudieshaveinvestigatedthe

relevanceoftheso-calledLucascritiqueformacro-modelling,andmosthaveconcludedthatitisnotofanyempiricalsignificanceinaccountingforthefailuresoftheeconometricmodels(seeFischer,1988).Taylor(1989),forinstance,findsthatthereduced-formparametersofthePhillipscurvearestableacrossalterna-tiveexchangerateregimes.Blanchard(1984)considersoneparticularpolicyshift—thechangeinmonetarypolicyannouncedin1979bytheFederalReserveBoard,whichthenstartedtotargetthemoneystockinsteadofinterestrates,and,again,reportsthattherewasnomajorshiftinthePhillipscurve.AlogouskoufisandSmith(1991),onthecontrary,showthattheswitchfromfixedtofloatingratesincreasedthepersistenceofinflationandwagesintheUSAandintheUK.Sims(1982)arguedthatLucas’sframeworkappliesonlytoasmallnumberofregimechangeswhichoccurratherinfrequentlyand,toalargeextent,arenotanticipated(see,also,Cooley,LeRoyandRaymon,1984).Ontheotherhand,ifpolicychangesarejustsmalldeviationsfromthepolicypre-viouslypursued,itshouldbepossibletomodelaggregaterelationshipsadequatelybysimplyspecifyingtime-vary-ingcoefficientsinBayesianvectorautoregressions(BVAR’s).Thisistheso-calledDoan—Litterman—Sims(DLS)approach,criticizedbyMillerandRoberds(1991a),whoholdthattheLucascritiqueisquantitativelyimportant,eveninBVARmacro-models.

0003—68461996Chapman&Hall663AnadditionalreasonwhycautioniscalledforindrawingconclusionsabouttherelevanceoftheLucascritiqueinappliedeconomicsisthepossibilityof‘spuriousstructuralstability’(seeSmith,1991).Theomissionofvariablesfromamodelwithunstableparameterscanmakethemodelpassstandardstabilitytests(theothercaseofparameterinstabil-ityderivingfromtheomissionofrelevantvariablesiswellknown).Onemorefundamentalpointconcernstheinterpreta-tionoftheLucascritiqueasapplyingtoreduced-formequationsortostructuralrelationships.Ifitistakentomeanthatachangeinoneparticularstructuralequa-tionwillnecessarilyresultinacorrespondingchangeinalltheotherstructuralequationswithforward-lookingvariables,thenanytestsappliedtoreducedformequationswouldnothaveanybearingonthevalidityoftheLucascritique;theywouldjustbeanassessmentoftheadequacy,inpractice,ofreduced-formequationsforthepurposeofconductingpolicyanalysisexercises(seeHamilton,1991).MillerandRoberds’s(1991b)interpretationisthattestingtheLucascritique,andtestingthestabilityofreduced-formequationsinthepresenceofregimeshifts,amounttothesamething,sinceLucas’sinsightisthatnotonlyreduced-formmodelsbutalsostructuralmodels,arenotinvarianttopolicychanges;onlythe‘deep’para-metersofthesystemhavetheinvarianceproperty.Thus,totesttheinvarianceoftheseparametersistantamounttoevaluatingtheempiricalusefulnessofreduced-formrelationships.II.SOMETHEORYEngle,HendryandRichard(1983)defineavariablexRasweaklyexogenousforasetofparametersofinterestinaconditionalmodelofavariableyRwithparametersif:i)isafunctionoftheparametersalone;andii)andtheparametersofthemarginalmodelforxRarevariationfree,whichimpliesthatthereisnolossofinformationaboutfromneglectingthemarginalmodel.Furthermore,xRissaidtobestronglyexogenousforifxRisweaklyexo-genousforand½R\doesnotGranger-causexR,where½R\"(y2yR\)denotesthehistoryofyR.Finally,xRisdefinedassuperexogenousforifxRisweaklyexogenousforandisinvarianttochangesin.Forillustrativepurposes,letitbeassumedthatthejointdistributionofyRandxRisconditionalnormal,withcondi-tionalmeansE[yR"IR]"WR(1)E[xR"IR]"VRSeeFaveroandHendry(1992)forareviewoftheLucascritique.andcovariancematrixR"