the history of education

中学历史教学的英文

中学历史教学的英文The Importance of History Education in Secondary SchoolsHistory is a fundamental subject that plays a crucial role in shaping the understanding and perspective of students in secondary schools. It not only provides a comprehensive understanding of the past but also equips students with the necessary skills to navigate the complexities of the present and prepare them for the challenges of the future. In this essay, we will explore the significance of history education in secondary schools and why it should be a core component of the curriculum.Firstly, history education fosters a deeper understanding of the human experience. By studying the events, cultures, and civilizations of the past, students gain a comprehensive perspective on the human condition. They learn about the triumphs and struggles of humanity, the evolution of societies, and the complex interplay of political, social, and economic forces that have shaped the world we live in today. This knowledge not only satisfies students' natural curiosity about the past but also helps them develop a more nuanced understanding of the present.Secondly, history education cultivates critical thinking skills. The study of history requires students to analyze and interpret a wide range of primary and secondary sources, evaluate the reliability and bias of information, and draw logical conclusions. These skills are not only essential for success in history but are also transferable to other academic disciplines and real-world problem-solving. By engaging in the process of historical inquiry, students learn to question assumptions, challenge dominant narratives, and think critically about the world around them.Moreover, history education fosters a sense of cultural awareness and global citizenship. By exploring the diverse histories and experiences of different societies and civilizations, students develop a deeper appreciation for cultural diversity and the interconnectedness of the global community. This understanding encourages students to be more empathetic, tolerant, and respectful of different perspectives and backgrounds, which is crucial in an increasingly globalized world.In addition, history education plays a vital role in shaping national and personal identity. By studying the history of their own country or region, students develop a stronger sense of belonging and a deeper understanding of their cultural heritage. This knowledge can instill a sense of pride and patriotism, while also encouraging students to reflect on their own place in the larger historical narrative and theirresponsibility as citizens.Furthermore, history education can provide valuable insights into contemporary issues and challenges. By examining the root causes and historical precedents of current events, students can better understand the complexities of the present and develop more informed and nuanced perspectives on complex social, political, and economic problems. This knowledge can empower students to become active and engaged citizens, capable of participating in the democratic process and contributing to the betterment of their communities.Finally, history education can inspire and motivate students to pursue further learning and personal growth. The stories and narratives of the past can be captivating and inspiring, igniting students' curiosity and fostering a lifelong love of learning. By engaging with the rich tapestry of human history, students can develop a deeper appreciation for the resilience, creativity, and ingenuity of the human spirit, which can serve as a source of inspiration and motivation throughout their lives.In conclusion, history education in secondary schools is essential for developing well-rounded, critical-thinking, and globally-minded citizens. By providing students with a comprehensive understanding of the past, cultivating essential skills, fostering cultural awareness,and inspiring personal growth, history education plays a vital role in preparing students for the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century. Therefore, it is crucial that history education remains a core component of the secondary school curriculum, empowering students to become active and engaged members of their communities and the world at large.。

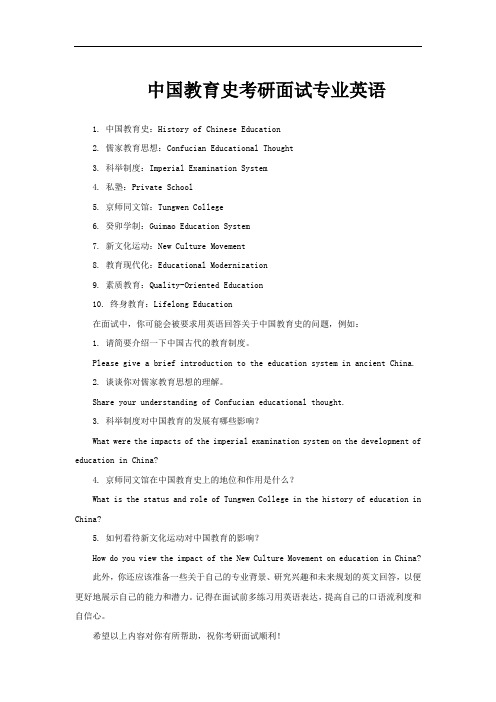

中国教育史考研面试专业英语

中国教育史考研面试专业英语1. 中国教育史:History of Chinese Education2. 儒家教育思想:Confucian Educational Thought3. 科举制度:Imperial Examination System4. 私塾:Private School5. 京师同文馆:Tungwen College6. 癸卯学制:Guimao Education System7. 新文化运动:New Culture Movement8. 教育现代化:Educational Modernization9. 素质教育:Quality-Oriented Education10. 终身教育:Lifelong Education在面试中,你可能会被要求用英语回答关于中国教育史的问题,例如:1. 请简要介绍一下中国古代的教育制度。

Please give a brief introduction to the education system in ancient China.2. 谈谈你对儒家教育思想的理解。

Share your understanding of Confucian educational thought.3. 科举制度对中国教育的发展有哪些影响?What were the impacts of the imperial examination system on the development of education in China?4. 京师同文馆在中国教育史上的地位和作用是什么?What is the status and role of Tungwen College in the history of education in China?5. 如何看待新文化运动对中国教育的影响?How do you view the impact of the New Culture Movement on education in China?此外,你还应该准备一些关于自己的专业背景、研究兴趣和未来规划的英文回答,以便更好地展示自己的能力和潜力。

中国教育体系 History of education in China

The introduction of modern education

Following the defeat of the Chinese empire in the Opium Wars, modern western education was eagerly sought out in the domains of foreign languages, national defence, and new techniques of industrial production. The Capital Foreign Language House (zh:京师 同文馆) (jīng-shī tóng-wén-guǎn) was set up in 1862. Countless overseas students were sent by the government or by their families to Europe, USA, and Japan. In the late 19th century, several modern universities were founded, such as Peking University and Jiaotong University.

History of education in China

History of education in China

• The history of education in China began with the birth of Chinese civilization. The nobles often set up the educational establishments for their offspring. The Shang Hsiang was a legendary school to teach the youth nobles. The government later established the civil service exam, where people from the lower classes could take tests in order to obtain prominent governmental positios BC, Qin Shi Huang favored Legalism (Chinese philosophy),and regarded others as either dangerous to his rule or useless,so he carried out burning of books and burying of scholars. He suppressed all non-state official ideas. Similar to ancient Greece and Rome, the patriarchal nature of Qin society meant that women were usually not educated and stayed home to do housework.

教育史总结汇报英文

教育史总结汇报英文Education has played a pivotal role in shaping societies and individuals throughout history, providing a means to impart knowledge, skills, and values to future generations. In this summary report, we will explore the major milestones and significant developments in the history of education.The origins of education can be traced back to ancient civilizations, such as Mesopotamia and Egypt, where formal systems of education emerged to train priests and bureaucrats. In ancient Greece, education underwent a significant transformation, as philosophers like Plato emphasized the importance of education for the moral and intellectual development of individuals. This period also saw the establishment of the Academy, an institution that laid the foundation for modern universities.During the Middle Ages, education became closely linked to religious institutions. Monasteries and cathedrals became centersof education, offering instruction in subjects like theology, philosophy, and Latin. However, education was largely limited to the elite and clergy, with most of the population remaining illiterate.The Renaissance marked a turning point in the history of education. Humanist scholars like Erasmus and Vittorino da Feltre championed the idea of a well-rounded education that included the humanities, sciences, and physical education. The printing press played a crucial role in disseminating knowledge, making books more accessible and facilitating learning outside traditional educational institutions.The Enlightenment period brought about a significant shift in thinking about education. Thinkers like John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau advocated for education as a means to foster individual freedom, self-expression, and critical thinking. The establishment of public schools and the spread of literacy became central goals in many European countries.The 19th century witnessed a surge in educational reforms worldwide. The industrial revolution necessitated new skills and knowledge, leading to the introduction of the first comprehensive education systems. Prominent figures like Horace Mann in the United States and Friedrich Fröbel in Germany advocated for compulsory education and the establishment of kindergartens, respectively. Girls' education also gained recognition during this period, challenging gender inequalities in education.The 20th century witnessed remarkable advancements in education across the globe. Mass education became a reality in many countries, improving literacy rates and providing educational opportunities for a wider population. The introduction of educational psychology and pedagogical theories, such as behaviorism and constructivism, shaped teaching methodologies and curriculum development.The advent of technology in the late 20th century revolutionized education. Computers, internet, and digital media transformed the way knowledge is accessed, processed, and communicated. E-learning and distance education gained popularity, allowing individuals to pursue education at their own pace and convenience.In recent years, there has been a growing emphasis on alternative forms of education. Montessori, Waldorf, and homeschooling approaches have gained traction, offering personalized and flexible learning experiences. Additionally, there is a greater recognition of the importance of lifelong learning, with adult education programs and vocational training becoming integral parts of education systems.As we reflect on the history of education, it becomes evident that education is a dynamic field that constantly adapts to societal, economic, and technological changes. From ancient civilizations to the modern era, education has been instrumental in advancing knowledge, fostering personal growth, and promoting social mobility.。

传统教育_中国_PPT

•

Song Dynasty above Tang Dynasty training school education development foundation, also set up has trained the military talented person specially military study and raises the calligraphy and painting talented person's picture study specially.After Song Dynasty, the medicine, the masculine and feminine elements study has also obtained the development.

In the sui dynasty, China has formed complete education system of school. 在隋朝,我国形成较完备的学校教育制度。

The emperor SUI WEN advocates to opening schools, set up offical schools from central to local.This offical school also called Guo ZI Jian . In that time ,the department and officials of specially manage with education began to appear .

教育是原始人适应当时社会生活和生产 劳动的需要而产生的一种活动,并且随 着人类生产生活的进行而发展变化着。

History of the development of traditional Chinese education

The Aims of Education (luo)

The Aims of Education口A.N.Whitehead作者简介A·N·怀特海(Alfred North Whitehead,1861—1947)是英国数学家、教育家、逻辑学家和20世纪40年代中期杰出的哲学家。

怀特海最主要的学术成就是他对哲学的贡献。

在哈佛期间,他创立了过程哲学——20世纪最庞大的形而上学体系,并在《过程与实在》中阐明了其哲学理论。

过程哲学又称活动过程哲学或有机体哲学,主张宇宙全部由生成变化所构成,世界即是过程,要求以机体概念代替物质概念。

选文内容《教育的目的》(The Aims of Education,1929)是怀特海的一本关于教育的论文集。

本书选文是该论文集中的第1篇。

在这篇文章中,怀特海指出文化是一种思想活动,是对美和人类情感的领悟,与零碎的知识无关。

一个仅仅满腹经纶的人对于世界是最无裨益的。

教育的目标是培养同时具备文化修养和专业知识的人才。

因此,最重要的是教会学生如何思考,帮助他们独立发展。

怀特海坚决反对灌输那些仅仅为大脑被动地接受,而没有经过运用、检验或从新的角度观察的僵化观念。

他提出防止这种蛀蚀性疾病的教育方法就是“少而精”,学生必须把所学知识变为自己的东西,并了解这些知识是如何与实际生活息息相关并得以运用的。

怀特海的教育思想中渗透着他的哲学观点。

他不仅注意数学和其他自然科学的论据,也重视社会科学以及美学、伦理学和宗教经验的论据。

虽然他常常以晦涩的术语表达其思想,但援引了许多历史和日常生活中有代表性的材料作为佐证,使文章很有说服力。

文中所谈实例取自英国,尽管英国的教育制度与他国并不完全相同,但怀特海提出的一般教育原则是广泛适用的。

The Aims of Education--A Plea for Reform (by Whitehead)by Alfred North Whitehead1. Culture is activity of thought, and receptiveness to beauty and humane feeling. Scraps of information have nothing to do with it. A merely well-informed man is the most useless bore on God's earth. What we should aim at producing is men who possess both culture and expert knowledge in some special direction. Their expert knowledge will give them the ground to start from, and their culture will lead them as deep as philosophy and as high as art. We have to remember that the valuable intellectual development is self-development, and that it mostly takes place between the ages of sixteen and thirty. As to training, the most important part is given by mothers before the age of twelve. A saying due to Archbishop Temple illustrates my meaning. Surprise was expressed at the success in after-life of a man, who as a boy at Rugby had been somewhat undistinguished. He answered, “It is not what they are at eighteen, it is what they become afterwards that matters.”2. In training a child to activity of thought, above all things we must beware of what I will call “inert ideas” — that is to say, ideas that are merely received into the mind without being utilised, or tested, or thrown into fresh combinations.3. In the history of education, the most striking phenomenon is that schools of learning, which at one epoch are alive with a ferment of genius, in a succeeding generation exhibit merely pedantry and routine. The reason is, that they are overladen with inert ideas. Education with inert ideas is not only useless: it is, above all things, harmful —Corruptio optimi, pessima. Except at rare intervals of intellectual ferment, education in the past has been radically infected with inert ideas. That is the reason why uneducated clever women, who have seen much of the world, are in middle life so much the most cultured part of the community. They have been saved from this horrible burden of inert ideas. Every intellectual revolution which has ever stirred humanity into greatness has been a passionate protest against inert ideas. Then, alas, with pathetic ignorance of human psychology, it has proceeded by some educational scheme to bind humanity afresh with inert ideas of its own fashioning.4. Let us now ask how in our system of education we are to guard against this mental dryrot. We enunciate our two educational commandments, “Do not teach too many subjects,” and again, “What you teach, teach thoroughly.”5. The result of teaching small parts of a large number of subjects is the passive reception of disconnected ideas, not illumined with any spark of vitality. Let the main ideas which are introduced into a child's education be few and important, and let them be thrown into every combination possible. The child should make them his own, and should understand their application here and now in the circumstances of his actual life. From the very beginning of his education, the child should experience the joy of discovery. The discovery which he has to make, is that general ideas give an understanding of that stream of events which pours through his life, which is his life. By understanding I mean more than a mere logical analysis, though that is included. I mean "understanding" in the sense in which it is used in the French proverb, "To understand all, is to forgive all." Pedants sneer at an education which is useful. But if education is not useful, what is it? Is it a talent, to be hidden away in a napkin? Of course, education should be useful, whatever your aim in life. It was useful to Saint Augustine and it was useful to Napoleon. It is useful, because understanding is useful.6. I pass lightly over that understanding which should be given by the literary side of education. Nor do I wish to be supposed to pronounce on the relative merits of a classical or a modern curriculum. I would only remark that the understanding which we want is an understanding of an insistent present. The only use of a knowledge of the past is to equip us for the present. No more deadly harm can be done to young minds than by depreciation of the present. The present contains all that there is. It is holy ground; for it is the past, and it is the future. At the same time it must beobserved that an age is no less past if it existed two hundred years ago than if it existed two thousand years ago. Do not be deceived by the pedantry of dates. The ages of Shakespeare and of Molière are no less past than are the ages of Sophocles and of Virgil. The communion of saints is a great and inspiring assemblage, but it has only one possible hall of meeting, and that is, the present, and the mere lapse of time through which any particular group of saints must travel to reach that meeting-place, makes very little difference.Passing now to the scientific and logical side of education, we remember that here also ideas which are not utilised are positively harmful. By utilising an idea, I mean relating it to that stream, compounded of sense perceptions, feelings, hopes, desires, and of mental activities adjusting thought to thought, which forms our life. I can imagine a set of beings which might fortify their souls by passively reviewing disconnected ideas. Humanity is not built that way—except perhaps some editors of newspapers.7. In scientific training, the first thing to do with an idea is to prove it. But allow me for one moment to extend the meaning of "prove"; I mean -- to prove its worth. Now an idea is not worth much unless the propositions in which it is embodied are true. Accordingly an essential part of the proof of an idea is the proof, either by experiment or by logic, of the truth of the propositions. But it is not essential that this proof of the truth should constitute the first introduction to the idea. After all, its assertion by the authority of respectable teachers is sufficient evidence to begin with. In our first contact with a set of propositions, we commence by appreciating their importance. That is what we all do in after-life. We do not attempt, in the strict sense, to prove or to disprove anything, unless its importance makes it worthy of that honour. These two processes of proof, in the narrow sense, and of appreciation, do not require a rigid separation in time. Both can be proceeded with nearly concurrently. But in so far as either process must have the priority, it should be that of appreciation by use.8. Furthermore, we should not endeavour to use propositions in isolation. Emphatically I do not mean, a neat little set of experiments to illustrate Proposition I and then the proof of Proposition I, a neat little set of experiments to illustrate Proposition II and then the proof of Proposition II, and so on to the end of the book. Nothing could be more boring. Interrelated truths are utilised en bloc, and the various propositions are employed in any order, and with any reiteration. Choose some important applications of your theoretical subject; and study them concurrently with the systematic theoretical exposition. Keep the theoretical exposition short and simple, but let it be strict and rigid so far as it goes. It should not be too long for it to be easily known with thoroughness and accuracy. The consequences of a plethora of half-digested theoretical knowledge are deplorable. Also the theory should not be muddled up with the practice. The child should have no doubt when it is proving and when it is utilising. My point is that what is proved should be utilised, and that what is utilised should -- so far, as is practicable -- be proved. I am far from asserting that proof and utilisation are the same thing.9. At this point of my discourse, I can most directly carry forward my argument in the outward form of a digression. We are only just realising that the art and science of education require a genius and a study of their own; and that this genius and this science are more than a bare knowledge of some branch of science or of literature. This truth was partially perceived in the past generation; and headmasters, somewhat crudely, were apt to supersede learning in their colleagues by requiring left-hand bowling and a taste for football. But culture is more than cricket, and more than football, and more than extent of knowledge.10. Education is the acquisition of the art of the utilisation of knowledge. This is an art very difficult to impart. Whenever a textbook is written of real educational worth, you may be quite certain that some reviewer will say that it will be difficult to teach from it. Of course it will be difficult to teach from it. If it were easy, the book ought to be burned; for it cannot be educational. In education, as elsewhere, the broad primrose path leads to a nasty place. This evil path is represented by a book or a set of lectures which will practically enable the student to learn by heart all the questions likely to be asked at the next external examination. And I may say in passing that no educational system is possible unless every question directly asked of a pupil at any examination is either framed or modified by the actual teacher of that pupil in that subject. The external assessor may report on the curriculum or on the performance of the pupils, but never should be allowed to ask the pupil a question which has not been strictly supervised by the actual teacher, or at least inspired by a long conference with him. There are a few exceptions to this rule, but they are exceptions, and could easily be allowed for under the general rule.11. We now return to my previous point, that theoretical ideas should always find important applications within the pupil's curriculum. This is not an easy doctrine to apply, but a very hard one. It contains within itself the problem of keeping knowledge alive, of preventing it from becoming inert, which is the central problem of all education.12. The best procedure will depend on several factors, none of which can be neglected, namely, the genius of the teacher, the intellectual type of the pupils, their prospects in life, the opportunities offered by the immediate surroundings of the school and allied factors of this sort. It is for this reason that the uniform external examination is so deadly. We do not denounce it because we are cranks, and like denouncing established things. We are not so childish. Also, of course, such examinations have their use in testing slackness. Our reason of dislike is very definite and very practical. It kills the best part of culture. When you analyse in the light of experience the central task of education, you find that its successful accomplishment depends on a delicate adjustment of many variable factors. The reason is that we are dealing with human minds, and not with dead matter. The evocation of curiosity, of judgment, of the power of mastering a complicated tangle of circumstances, the use of theory in givingforesight in special cases -- all these powers are not to be imparted by a set rule embodied in one schedule of examination subjects.13. I appeal to you, as practical teachers. With good discipline, it is always possible to pump into the minds of a class a certain quantity of inert knowledge. You take a text-book and make them learn it. So far, so good. The child then knows how to solve a quadratic equation. But what is the point of teaching a child to solve a quadratic equation? There is a traditional answer to this question. It runs thus: The mind is an instrument, you first sharpen it, and then use it; the acquisition of the power of solving a quadratic equation is part of the process of sharpening the mind. Now there is just enough truth in this answer to have made it live through the ages. But for all its half-truth, it embodies a radical error which bids fair to stifle the genius of the modern world. I do not know who was first responsible for this analogy of the mind to a dead instrument. For aught I know, it may have been one of the seven wise men of Greece, or a committee of the whole lot of them. Whoever was the originator, there can be no doubt of the authority which it has acquired by the continuous approval bestowed upon it by eminent persons. But whatever its weight of authority, whatever the high approval which it can quote, I have no hesitation in denouncing it as one of the most fatal, erroneous, and dangerous conceptions ever introduced into the theory of education. The mind is never passive; it is a perpetual activity, delicate, receptive, responsive to stimulus. You cannot postpone its life until you have sharpened it. Whatever interest attaches to your subject-matter must be evoked here and now; whatever powers you are strengthening in the pupil, must be exercised here and now; whatever possibilities of mental life your teaching should impart, must be exhibited here and now. That is the golden rule of education, and a very difficult rule to follow.14. The difficulty is just this: the apprehension of general ideas, intellectual habits of mind, and pleasurable interest in mental achievement can be evoked by no form of words, however accurately adjusted. All practical teachers know that education is a patient process of the mastery of details, minute by minute, hour by hour, day by day. There is no royal road to learning through an airy path of brilliant generalisations. There is a proverb about the difficulty of seeing the wood because of the trees. That difficulty is exactly the point which I am enforcing. The problem of education is to make the pupil see the wood by means of the trees.15. The solution which I am urging, is to eradicate the fatal disconnection of subjects which kills the vitality of our modern curriculum. There is only one subject-matter for education, and that is Life in all its manifestations. Instead of this single unity, we offer children -- Algebra, from which nothing follows; Geometry, from which nothing follows; Science, from which nothing follows; History, from which nothing follows; a Couple of Languages, never mastered; and lastly, most dreary of all, Literature, represented by plays of Shakespeare, with philological notes and short analyses of plot and character to be in substance committed to memory. Can such a list be said to represent Life, as it is known in the midst of the living of it? The best that can be saidof it is, that it is a rapid table of contents which a deity might run over in his mind while he was thinking of creating a world, and has not yet determined how to put it together.16. Let us now return to quadratic equations. We still have on hand the unanswered question. Why should children be taught their solution? Unless quadratic equations fit into a connected curriculum, of course there is no reason to teach anything about them. Furthermore, extensive as should be the place of mathematics in a complete culture, I am a little doubtful whether for many types of boys algebraic solutions of quadratic equations do not lie on the specialist side of mathematics. I may here remind you that as yet I have not said anything of the psychology or the content of the specialism, which is so necessary a part of an ideal education. But all that is an evasion of our real question, and I merely state it in order to avoid being misunderstood in my answer.17. Quadratic equations are part of algebra, and algebra is the intellectual instrument which has been created for rendering clear the quantitative aspects of the world. There is no getting out of it. Through and through the world is infected with quantity. To talk sense, is to talk in quantities. It is no use saying that the nation is large, -- How large? It is no use saying that radium is scarce, -- How scarce? You cannot evade quantity. You may fly to poetry and to music, and quantity and number will face you in your rhythms and your octaves. Elegant intellects which despise the theory of quantity, are but half developed. They are more to be pitied than blamed, The scraps of gibberish, which in their school-days were taught to them in the name of algebra, deserve some contempt.18. This question of the degeneration of algebra into gibberish, both in word and in fact, affords a pathetic instance of the uselessness of reforming educational schedules without a clear conception of the attributes which you wish to evoke in the living minds of the children. A few years ago there was an outcry that school algebra, was in need of reform, but there was a general agreement that graphs would put everything right. So all sorts of things were extruded, and graphs were introduced. So far as I can see, with no sort of idea behind them, but just graphs. Now every examination paper has one or two questions on graphs. Personally I am an enthusiastic adherent of graphs. But I wonder whether as yet we have gained very much. You cannot put life into any schedule of general education unless you succeed in exhibiting its relation to some essential characteristic of all intelligent or emotional perception. It is a hard saying, but it is true; and I do not see how to make it any easier. In making these little formal alterations you are beaten by the very nature of things. You are pitted against too skilful an adversary, who will see to it that the pea is always under the other thimble.19. Reformation must begin at the other end. First, you must make up your mind as to those quantitative aspects of the world which are simple enough to be introduced into general education; then a schedule of algebra should be framed which will about findits exemplification in these applications. We need not fear for our pet graphs, they will be there in plenty when we once begin to treat algebra as a serious means of studying the world. Some of the simplest applications will be found in the quantities which occur in the simplest study of society. The curves of history are more vivid and more informing than the dry catalogues of names and dates which comprise the greater part of that arid school study. What purpose is effected by a catalogue of undistinguished kings and queens? Tom, Dick, or Harry, they are all dead. General resurrections are failures, and are better postponed. The quantitative flux of the forces of modern society is capable of very simple exhihition. Meanwhile, the idea of the variable, of the function, of rate of change, of equations and their solution, of elimination, are being studied as an abstract science for their own sake. Not, of course, in the pompous phrases with which I am alluding to them here, but with that iteration of simple special cases proper to teaching.20. If this course be followed, the route from Chaucer to the Black Death, from the Black Death to modern Labour troubles, will connect the tales of the mediaeval pilgrims with the abstract science of algebra, both yielding diverse aspects of that single theme, Life. I know what most of you are thinking at this point. It is that the exact course which I have sketched out is not the particular one which you would have chosen, or even see how to work. I quite agree. I am not claiming that I could do it myself. But your objection is the precise reason why a common external examination system is fatal to education. The process of exhibiting the applications of knowledge must, for its success, essentially depend on the character of the pupils and the genius of the teacher. Of course I have left out the easiest applications with which most of us are more at home. I mean the quantitative sides of sciences, such as mechanics and physics.21. Again, in the same connection we plot the statistics of social phenomena against the time. We then eliminate the time between suitable pairs. We can speculate how far we have exhibited a real causal connection, or how far a mere temporal coincidence. We notice that we might have plotted against the time one set of statistics for one country and another set for another country, and thus, with suitable choice of subjects, have obtained graphs which certainly exhibited mere coincidence. Also other graphs exhibit obvious causal connections. We wonder how to discriminate. And so are drawn on as far as we will.22. But in considering this description, I must beg you to remember what I have been insisting on above. In the first place, one train of thought will not suit all groups of children. For example, I should expect that artisan children will want something more concrete and, in a sense, swifter than I have set down here. Perhaps I am wrong, but that is what I should guess. In the second place, I am not contemplating one beautiful lecture stimulating, once and for all, an admiring class. That is not the way in which education proceeds. No; all the time the pupils are hard at work solving examples drawing graphs, and making experiments, until they have a thorough hold on thewhole subject. I am describing the interspersed explanations, the directions which should be given to their thoughts. The pupils have got to be made to feel that they are studying something, and are not merely executing intellectual minuets.23. Finally, if you are teaching pupils for some general examination, the problem of sound teaching is greatly complicated. Have you ever noticed the zig-zag moulding round a Norman arch? The ancient work is beautiful, the modern work is hideous. The reason is, that the modern work is done to exact measure, the ancient work is varied according to the idiosyncrasy of the workman. Here it is crowded, and there it is expanded. Now the essence of getting pupils through examinations is to give equal weight to all parts of the schedule. But mankind is naturally specialist. One man sees a whole subject, where another can find only a few detached examples.I know that it seems contradictory to allow for specialism in a curriculum especially designed for a broad culture. Without contradictions the world would be simpler, and perhaps duller. But I am certain that in education wherever you exclude specialism you destroy life.24. We now come to the other great branch of a general mathematical education, namely Geometry. The same principles apply. The theoretical part should be clear-cut, rigid, short, and important. Every proposition not absolutely necessary to exhibit the main connection of ideas should be cut out, but the great fundamental ideas should be all there. No omission of concepts, such as those of Similarity and Proportion. We must remember that, owing to the aid rendered by the visual presence of a figure, Geometry is a field of unequalled excellence for the exercise of the deductive faculties of reasoning. Then, of course, there follows Geometrical Drawing, with its training for the hand and eye.25. But, like Algebra, Geometry and Geometrical Drawing must be extended beyond the mere circle of geometrical ideas. In an industrial neighbourhood, machinery and workshop practice form the appropriate extension. For example, in the London Polytechnics this has been achieved with conspicuous success. For many secondary schools I suggest that surveying and maps are the natural applications. In particular, plane-table surveying should lead pupils to a vivid apprehension of the immediate application of geometric truths. Simple drawing apparatus, a surveyor's chain, and a surveyor's compass, should enable the pupils to rise from the survey and mensuration of a field to the construction of the map of a small district. The best education is to be found in gaining the utmost information from the simplest apparatus. The provision of elaborate instruments is greatly to be deprecated. To have constructed the map of a small district, to have considered its roads, its contours, its geology, its climate, its relation to other districts, the effects on the status of its inhabitants, will teach more history and geography than any knowledge of Perkin Warbeck or of Behren's Straits. I mean not a nebulous lecture on the subject, but a serious investigation in which the real facts are definitely ascertained by the aid of accurate theoretical knowledge. A typical mathematical problem should be: Survey such and such a field, draw a plan of it to such and such a scale, and find the area. It would be quite a good procedure toimpart the necessary geometrical propositions without their proofs. Then, concurrently in the same term, the proofs of the propositions would be learnt while the survey was being made.26. Fortunately, the specialist side of education presents an easier problem than does the provision of a general culture. For this there are many reasons. One is that many of the principles of procedure to be observed are the same in both cases, and it is unnecessary to recapitulate. Another reason is that specialist training takes place—or should take place—at a more advanced stage of the pupil's course, and thus there is easier material to work upon. But undoubtedly the chief reason is that the specialist study is normally a study of peculiar interest to the student. He is studying it because, for some reason, he wants to know it. This makes all the difference. The general culture is designed to foster an activity of mind; the specialist course utilises this activity. But it does not do to lay too much stress on these neat antitheses. As we have already seen, in the general course foci of special interest will arise; and similarly in the special study, the external connections of the subject drag thought outwards.27. Again, there is not one course of study which merely gives general culture, and another which gives special knowledge. The subjects pursued for the sake of a general education are special subjects specially studied; and, on the other hand, one of the ways of encouraging general mental activity is to foster a special devotion. You may not divide the seamless coat of learning. What education has to impart is an intimate sense for the power of ideas, for the beauty of ideas, and for the structure of ideas, together with a particular body of knowledge which has peculiar reference to the life of the being possessing it.28. The appreciation of the structure of ideas is that side of a cultured mind which can only grow under the influence of a special study. I mean that eye for the whole chess-board, for the bearing of one set of ideas on another. Nothing but a special study can give any appreciation for the exact formulation of general ideas, for their relations when formulated, for their service in the comprehension of life. A mind so disciplined should be both more abstract and more concrete. It has been trained in the comprehension of abstract thought and in the analysis of facts.29. Finally, there should grow the most austere of all mental qualities; I mean the sense for style. It is an aesthetic sense, based on admiration for the direct attainment of a foreseen end, simply and without waste. Style in art, style in literature, style in science, style in logic, style in practical execution have fundamentally the same aesthetic qualities, namely, attainment and restraint. The love of a subject in itself and for itself, where it is not the sleepy pleasure of pacing a mental quarter-deck, is the love of as manifested in that study.30. Here we are brought back to the position from which we started, the utility of education , in its finest sense, is the last acquirement of the educated mind; it is also。

Education is one of the most important things in the world

Education is one of the most important things in the world. Every country spends a lot of money to develope their education every year. So education is very important to every country. Any developed countries must have a strong educational system. But different countries have different educational systems. It’s necessary to have a good educational system. This paper will compare to see the differences between two countries’ educational systems. As we know each country has its own different educational system such as China and Germany. These two countries’ educational systems have many differences.Germany is a developed country. Germany has a long history of education and it has enjoyed a good education for a long time. However its system also has some problems. The education of Germany is complex, and a variety of ways and principals exist. They introduced compulsory education much earlier than China. Since 1871, many schools have been built, in order to enable more people to study. At the same time, four different schools were built: Gymnasium, Realgymnasium, Realschule, Oberrealschule. Gymnasium teach Latin Greek or Hebrew and the other languages, and students have 9 years to study. Realgymnasium teaches students Latin and the other languages and math or science. Students study 9 years. Realschule has 6 years of study. After studying in the school, students haven’t qualifications to go to university. After graduating, students can go to to work as blue-colar works.Oberrealschule is like Realgymnasium. In Germany, different places has different educational systems, because every prefecture institutes an educational system by themselves, so in Germany, different place has different educational system and different history of education. Germany educational system is divided into three parts, Basic education, secondary education and college or university education. They have a mandatory 12 year education. Every student must take part in basic education, which means they need to study 4 years or 6 years. The secondary education has 4 different schools, Hauptschule Realschule Gymnasium and Gesamtschule. Hauptschule is a vocational education school. Realschule is a high vocational education school. Gymnasium is like Chinese high school. Gesamtschule has a goal to help all students with lower scores and less money. And not just because some of the subjects lost the unsatisfactory results of better learning opportunities, they can be based on consideration of personal preferences and interests to develop, such as social-out mechanism is not the same as better development of the vulnerable and lost. The university or college education, it’s the highest education in Germany. Germany has 340 high schools, 160 universities, divinity school, and Academy of fine arts. It also has other schools called Fachhochschule and Berufsakademin. The main purpose of higher education is to cultivate talent and academic research for new knowledge and creation. The developed modern Germany has about 190 millionpeople in the universities, yet it will grow in 2011 to 220-240 million. In Germany, there is no organized college entrance examination; because each different locality has different educational system. So in Germany, if you want to go to university, you must have a good grade and you must understand which school you want to go, it’s necessary. So in Germany, different students have different choice which school you want to go. Last, have some funny things to me. In Germany, parents never force child to study better, they are respect child that which kinds of school they wantto choice.Now, regarding progress and development, China has become stronger and stronger nation. The education in China, began at Sui dynasty, education just helped country choose good official. After Tang dynasty the education became better. Long time ago, if you wanted to study, you must have much money, it was a status symbol. It’s so bad to many students. But now, the education in China, has become better, at the same time, Chinese educational system has more problems. China is a big country, has too much people, so if you want to find a good job, you must go to school to study. Chinese educational system has differences and commons to Germany. China has an old system about the education. Now, Chinese education has 12 years compulsory education too. In China, every parent hopes their child lives better and has a better job than them. Children of 5 or 6 years old must go to primary school, and must have 6years of mandatory study. These primary schools have 9 kinds of subject, but primary schools don’t have a uniform exam. Students just need to pass the graduation exam. It’s help you chose a better school. About 11 or 12 years, the child needs to go to middle school. In China, middle school education is divided into 3 years. The middle school educational system has some difference to Germany, because in China, child must study many subjects. It has 12 different subjects that the student must study. In middle school, students must pass the entrance exam of high school, a difficult exam. For must students, the Entrance exam of high school is an important exam, because the Entrance exam of high school can predict you future, chose a good high school can help you study better. At the age of 14 or 15, students has two ways to study, one is go to the high school, the other choose vocational school. For must students, they would chose going to high school, because high school could help students finish their dream of going to university. In Chinese high schools, they have two different study paths, one is arts, the other is science, and they have different subjects and different exams. But in high school, students have to work hard, because when they graduate from high school, student will have to pass the Entrance exam of college and will receive a high school diploma. The Entrance exam of college, is the highest exam to students, it’s very difficult. The Entrance exam of college is organized by Chinese government. On the other hand , the Entrance exam of college isconsidered to be unfair, different localities has different exam. Now, many terrible things affect the exam, by using money, you could go to school,which you want to go. It’s very unfair to most students.If you want to go to a good university, students must work hard and have good grades, it’s necessary.Encourage that you are never too old to learn. Education is very important to every country, different country has different educational system. Regard to progress and development, the education will get better. Maybe in the future, student will have a best educational system. They can study better, without affect by prejudices, and only have to communicate and compete between students. Different countries have different educational system, but no matter how they change, I believe communication could help us to develop education. Even if the culture has differences, we are a big family in the world, let us make it better.。

The History of Education in Myanmar 缅甸教育史

The History of Education in MyanmarJuanitaBasically, education of Myanmar can divide into three developing stages:1、The ancient education of feudal dynastic period2、The modern education of colonial period3、The contemporary education after independence.1、The ancient education of feudal dynastic periodThe ancient education is a kind of traditional temple education; it was the base of education of Myanmar.2、The modern education of colonial periodBritain carried out the British educational system since Britain occupied Myanmar in 1885; meanwhile, the western culture filtered into Myanmar, education of Myanmar came into modern educational stage.The colonial education arose the two-faced influence: one was that established the base of contemporary education, the other was that limited the development of education; The colonialist just cultivated the "tool" which served for colonial domination and they trained the modern intelligentsia and promoted the national liberation movement.4、The contemporary education after independenceSince became independent from the Unite Kingdom in 1948, Myanmar was about to developed its own contemporary education. However, their education system is deteriorating under Myanmar’s military rule.(1)Public education is free, but the opportunity of rural education is limited.(2)Not all children have the chance to receive education, especially the workers and peasants’children.(3)In 1960, their education system is still half colonialism and half the nation. There is not yetspecific education policy.(4)Their education tools is still in EnglishCurrent education in Myanmar政府重视发展教育和扫盲工作,全民识字率94.75%。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

The History of Education

Education as a science cannot be separated from the educational traditions that existed before. Adults trained the young of their society in the knowledge and skills they would need to master and eventually pass on. The evolution of culture, and human beings as a species depended on this practice of transmitting knowledge.

In pre-literate societies this was achieved orally and through imitation. Story-telling continued from one generation to the next. Oral language developed into written symbols and letters. The depth and breadth of knowledge that could be preserved and passed soon increased exponentially. When cultures began to extend their knowledge beyond the basic skills of communicating, trading, gathering food, religious practices, etc., formal education, and schooling, eventually followed. Schooling in this sense was already in place in Egypt between 3000 and 500BC.

In the West, Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC. Plato was the Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician and writer of philosophical dialogues who founded the Academy in Athens which was the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Plato and his student, the political scientist Aristotle, helped lay the foundations of Western philosophy and science.The city of Alexandria in Egypt was founded in 330BC, became the successor to Athens as the intellectual cradle of the Western World. The city hosted such leading lights as the mathematician Euclid and anatomist Herophilus; constructed the great Library of Alexandria; and translated the Hebrew Bible into Greek. Greek civilization was subsumed within the Roman Empire. Western civilization suffered a collapse of literacy and organization following the fall of Rome in AD 476.

In the East, Confucius(551-479), of the State of Lu, was China's most influential ancient philosopher, whose educational outlook continues to influence the societies of China and neighbors like Korea, Japan and Vietnam. He gathered disciples and searched in vain for a ruler who would adopt his ideals for good governance, but his Analects were written down by followers and have continued to influence education in the East into the modern era.

In Western Europe after the Fall of Rome, the Catholic Church emerged as the unifying force. Initially the sole preserver of literate scholarship in Western Europe, the church established Cathedral schools in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education. Some of these ultimately evolved into medieval universities and forebears of many of Europe's modern universities. During the High Middle Ages, Chartres Cathedral operated the famous and influential Chartres Cathedral School. The medieval universities of Western Christendom were well-integrated across all of Western Europe, encouraged freedom of enquiry and produced a great variety of fine scholars and natural philosophers, including Thomas Aquinas of the University of Naples, Robert Grosseteste of the University of Oxford, an early expositor of a systematic method of scientific experimentation;and Saint Albert the Great, a pioneer

of biological field research. The University of Bologne is considered the oldest continually operating university.

The Renaissance in Europe ushered in a new age of scientific and intellectual inquiry and appreciation of ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. Around 1450, Gutenberg developed a printing press, which allowed works of literature to spread more quickly. The European Age of Empires saw European ideas of education in philosophy, religion, arts and sciences spread out across the globe. Missionaries and scholars also brought back new ideas from other civilizations - as with the Jesuit China missions who played a significant role in the transmission of knowledge, science, and culture between China and the West, translating Western works like Euclids Elements for Chinese scholars and the thoughts of Confucius for Western audiences. The Enlightenment saw the emergence of a more secular educational outlook in the West.。