Reflections from The Black Cat

《黑猫英语分级读物》初二有哪些篇目

《黑猫英语分级读物》初二有哪些篇目The "Black Cat Graded Readers" for the second year of junior high school (Grade 8) include the following titles:

1. The Canterville Ghost by Oscar Wilde

2. The Hound of the Baskervilles by Arthur Conan Doyle

3. The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

4. Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson

5. White Fang by Jack London

这套"黑猫英语分级读物"是针对初二学生设计的,包含了以下几个篇目:

1. 奥斯卡·王尔德的《坎特维尔的幽灵》

2. 阿瑟·柯南·道尔的《巴斯克维尔的猎犬》

3. 奥斯卡·王尔德的《道连·格雷的画像》

4. 罗伯特·路易斯·史蒂文森的《金银岛》

5. 杰克·伦敦的《白牙》

这些作品涉及了推理小说、恐怖小说、经典名著等多个流派,能够为初二学生提供丰富多样的英语阅读材料,提升他们的英语语言能力和文学素养。

- 1 -。

黑布林英语阅读《霍莉的新朋友》英文读后感

黑布林英语阅读《霍莉的新朋友》英文读后感Title: Reflections on "Holly"s New Friend" from the Black Cat English Reading SeriesIntroduction:"Holly"s New Friend," a story from the Black Cat English Reading series, serves as an engaging and heartwarming tale that not only teaches English but also imparts valuable life lessons.This read-aloud story captures the essence of friendship and growth, making it an enjoyable and educational experience for readers of all ages.Below is my detailed reflection on this delightful narrative.Reflections on "Holly"s New Friend":The charming story of "Holly"s New Friend" immediately draws readers into its pages, as we witness Holly"s initial struggle to adapt to her new environment after moving to a different town.This relatable situation sets the stage for the themes of friendship and resilience that resonate throughout the tale.One of the most significant takeaways from the story is the importance of stepping out of one"s comfort zone.Holly"s encounter with her new friend, Max, serves as a powerful reminder that sometimes we need to be brave and initiate conversations, as this can lead to unexpected and beautiful friendships.Their shared experiences ofexploring the town together and overcoming obstacles highlight the strength of their bond, which is a heartening message for readers.The language used in "Holly"s New Friend" is both accessible and rich in vocabulary, making it an excellent resource for English language learners.The story"s structure and clear narrative progression help readers grasp context and nuances, while the emotions portrayed by Holly and Max are described vividly, allowing readers to empathize with the characters.Moreover, the story subtly addresses the challenges of being the "new kid" and the social anxiety that comes with it.Holly"s growth from a shy and uncertain girl to a confident individual who values friendship is a testament to the positive impact that a supportive peer can have on our lives.From a pedagogical standpoint, "Holly"s New Friend" incorporates elements that foster critical thinking and comprehension skills.As readers, we are encouraged to reflect on our own experiences with making friends and how we can apply the story"s lessons to our daily lives.In conclusion, "Holly"s New Friend" from the Black Cat English Reading series is a treasure trove of learning and emotional depth.It successfully combines the joy of reading with the timeless values of friendship, courage, and personal growth.Whether you are a student,teacher, or simply a lover of stories, this narrative will undoubtedly leave a lasting impression and inspire you to seek out new friendships and experiences.ote: This reflection has been crafted with the utmost consideration for the story"s content and educational value, adhering to the guidelines provided.It does not contain any sensitive or inappropriate content, ensuring a safe and enriching reading experience.。

MJ关键词整句咒语分享

MJ关键词/咒语形容词,名词,描述词语均可按需求进行更改。

神圣风格用niji的模型会更好看。

关键词前可垫图(图片的链接最后需要空两格再接关键词)皮克斯/迪斯尼盲盒风插画风POP玛特盲盒风港风头像神圣风透明玻璃图标可爱拟人风科技感ICON剪纸风画面复古风格白色石膏风格画面写实风格扁平风UI插画blender搅拌机风超现实主义风格尘土爆炸风Commercial photography, powerful explosion of golden dust, large soft makeup brush, white lighting, studio light, 8k octane rendering, high resolution photography, insanely detailed, fine details, isolated plain, stock photo, professional color grading, award winning photography商业摄影,金黄灰尘,大软的构成刷子,白色照明,演播室光,8k辛烷翻译,高分辨率摄影,疯狂详细,细细节,被隔绝的平原,股票照片,专业颜色分级,获奖摄影的强有力的爆炸Commercial photography, powerful explosion of red dust, designer lipstick, whitelighting, studio light, 8k octane rendering, high resolution photography, insanely detailed, fine details, isolated plain, stock photo, professional color grading, award winning photography商业摄影,红色尘土,设计师口红,白色照明,演播室光,8k辛烷值翻译,高分辨率摄影,疯狂详细,细细节,被隔绝的平原,股票照片,专业颜色分级,获奖摄影的强大的爆炸。

墙上的斑点 英文

THE MARK ON THE WALLPerhaps it was the middle of January in the present that I first looked up and saw the mark on the wall. In order to fix a date it is necessary to remember what one saw. So now I think of the fire; the steady film of yellow light upon the page of my book; the three chrysanthemums in the round glass bowl on the mantelpiece. Yes, it must have been the winter time, and we had just finished our tea, for I remember that I was smoking a cigarette when I looked up and saw the mark on the wall for the first time. I looked up through the smoke of my cigarette and my eye lodged for a moment upon the burning coals, and that old fancy of the crimson flag flapping from the castle tower came into my mind, and I thought of the cavalcade of red knights riding up the side of the black rock. Rather to my relief the sight of the mark interrupted the fancy, for it is an old fancy, an automatic fancy, made as a child perhaps. The mark was a small round mark, black upon the white wall, about six or seven inches above the mantelpiece.How readily our thoughts swarm upon a new object, lifting it a little way, as ants carry a blade of straw so feverishly, and then leave it. . . If that mark was made by a nail, it can't have been for a picture, it must have been for a miniature--the miniature of a lady with white powdered curls, powder-dusted cheeks, and lips like red carnations. A fraud of course, for the people who had this house before us would have chosen pictures in that way--an old picture for an old room. That is the sort of people they were--very interesting people, and I think of them so often, in such queer places, because one will never see them again, never know what happened next. They wanted to leave this house because they wanted to change their style of furniture, so he said, and he was in process of saying that in his opinion art should have ideas behind it when we were torn asunder, as one is torn from the old lady about to pour out tea and the young man about to hit the tennis ball in the back garden of the suburban villa as one rushes past in the train.But as for that mark, I'm not sure about it; I don't believe it was made by a nail after all; it's too big, too round, for that. I might get up, but if I got up and looked at it, ten to one I shouldn't be able to say for certain; because once a thing's done, no one ever knows how it happened. Oh! dear me, the mystery of life; The inaccuracy of thought! The ignorance of humanity! To show how very little control of our possessions we have--what an accidental affair this living is after all our civilization--let me just count over a few of the things lost in one lifetime, beginning, for that seems always the most mysterious of losses--what cat would gnaw, what rat would nibble--three pale blue canisters of book-binding tools? Then there were the bird cages, the iron hoops, the steel skates, the Queen Anne coal-scuttle, the bagatelle board, the hand organ--all gone, and jewels, too. Opals and emeralds, they lie about the roots of turnips. What a scraping paring affair it is to be sure! The wonder is that I've any clothes on my back, that I sit surrounded by solid furniture at this moment. Why, if one wants to compare life to anything, one must liken it to being blown through the Tube at fifty miles an hour--landing at the other end without a single hairpin in one's hair! Shot out at the feet of God entirely naked! Tumbling head over heels in the asphodel meadows like brown paper parcels pitched down a shoot in the post office! With one's hair flying back like the tail of a race-horse. Yes, that seems to express the rapidity of life, the perpetual waste and repair; all so casual, all so haphazard. . . But after life. The slow pulling down of thick green stalks so that the cup of the flower, as it turns over, deluges one with purple and red light. Why, after all, should one not be born thereas one is born here, helpless, speechless, unable to focus one's eyesight, groping at the roots of the grass, at the toes of the Giants? As for saying which are trees, and which are men and women, or whether there are such things, that one won't be in a condition to do for fifty years or so. There will be nothing but spaces of light and dark, intersected by thick stalks, and rather higher up perhaps, rose-shaped blots of an indistinct colour--dim pinks and blues--which will, as time goes on, become more definite, become--I don't know what. . .And yet that mark on the wall is not a hole at all. It may even be caused by some round black substance, such as a small rose leaf, left over from the summer, and I, not being a very vigilant housekeeper--look at the dust on the mantelpiece, for example, the dust which, so they say, buried Troy three times over, only fragments of pots utterly refusing annihilation, as one can believe.The tree outside the window taps very gently on the pane. . . I want to think quietly, calmly, spaciously, never to be interrupted, never to have to rise from my chair, to slip easily from one thing to another, without any sense of hostility, or obstacle. I want to sink deeper and deeper, away from the surface, with its hard separate facts. To steady myself, let me catch hold of the first idea that passes. . . Shakespeare. . . Well, he will do as well as another. A man who sat himself solidly in an arm-chair, and looked into the fire, so--A shower of ideas fell perpetually from some very high Heaven down through his mind. He leant his forehead on his hand, and people, looking in through the open door,--for this scene is supposed to take place on a summer's evening--But how dull this is, this historical fiction! It doesn't interest me at all. I wish I could hit upon a pleasant track of thought, a track indirectly reflecting credit upon myself, for those are the pleasantest thoughts, and very frequent even in the minds of modestmouse-coloured people, who believe genuinely that they dislike to hear their own praises. They are not thoughts directly praising oneself; that is the beauty of them; they are thoughts like this:"And then I came into the room. They were discussing botany. I said how I'd seen a flower growing on a dust heap on the site of an old house in Kingsway. The seed, I said, must have been sown in the reign of Charles the First. What flowers grew in the reign of Charles the First?" I asked--(but, I don't remember the answer). Tall flowers with purple tassels to them perhaps. And so it goes on. All the time I'm dressing up the figure of myself in my own mind, lovingly, stealthily, not openly adoring it, for if I did that, I should catch myself out, and stretch my hand at once for a book in self-protection. Indeed, it is curious how instinctively one protects the image of oneself from idolatry or any other handling that could make it ridiculous, or too unlike the original to be believed in any longer. Or is it not so very curious after all? It is a matter of great importance. Suppose the looking glass smashes, the image disappears, and the romantic figure with the green of forest depths all about it is there no longer, but only that shell of a person which is seen by other people--what an airless, shallow, bald, prominent world it becomes! A world not to be lived in. As we face each other in omnibuses and underground railways we are looking into the mirror that accounts for the vagueness, the gleam of glassiness, in our eyes. And the novelists in future will realize more and more the importance of these reflections, for of course there is not one reflection but an almost infinite number; those are the depths they will explore, those the phantoms they will pursue, leaving the description of reality more and more out of their stories, taking a knowledge of it for granted, as the Greeks did and Shakespeare perhaps--but these generalizations are very worthless.The military sound of the word is enough. It recalls leading articles, cabinet ministers--a whole class of things indeed which as a child one thought the thing itself, the standard thing, the real thing, from which one could not depart save at the risk of nameless damnation. Generalizations bring back somehow Sunday in London, Sunday afternoon walks, Sunday luncheons, and also ways of speaking of the dead, clothes, and habits--like the habit of sitting all together in one room until a certain hour, although nobody liked it. There was a rule for everything. The rule for tablecloths at that particular period was that they should be made of tapestry with little yellow compartments marked upon them, such as you may see in photographs of the carpets in the corridors of the royal palaces. Tablecloths of a different kind were not real tablecloths. How shocking, and yet how wonderful it was to discover that these real things, Sunday luncheons, Sunday walks, country houses, and tablecloths were not entirely real, were indeed half phantoms, and the damnation which visited the disbeliever in them was only a sense of illegitimate freedom. What now takes the place of those things I wonder, those real standard things? Men perhaps, should you be a woman; the masculine point of view which governs our lives, which sets the standard, which establishes Whitaker's Table of Precedency, which has become, I suppose, since the war half a phantom to many men and women, which soon--one may hope, will be laughed into the dustbin where the phantoms go, the mahogany sideboards and the Landseer prints, Gods and Devils, Hell and so forth, leaving us all with an intoxicating sense of illegitimate freedom--if freedom exists. . . In certain lights that mark on the wall seems actually to project from the wall. Nor is it entirely circular. I cannot be sure, but it seems to cast a perceptible shadow, suggesting that if I ran my finger down that strip of the wall it would, at a certain point, mount and descend a small tumulus, a smooth tumulus like those barrows on the South Downs which are, they say, either tombs or camps. Of the two I should prefer them to be tombs, desiring melancholy like most English people, and finding it natural at the end of a walk to think of the bones stretched beneath the turf. . . There must be some book about it. Some antiquary must have dug up those bones and given them a name. . . What sort of a man is an antiquary, I wonder? Retired Colonels for the most part, I daresay, leading parties of aged labourers to the top here, examining clods of earth and stone, and getting into correspondence with the neighbouring clergy, which, being opened at breakfast time, gives them a feeling of importance, and the comparison of arrow-heads necessitates cross-country journeys to the county towns, an agreeable necessity both to them and to their elderly wives, who wish to make plum jam or to clean out the study, and have every reason for keeping that great question of the camp or the tomb in perpetual suspension, while the Colonel himself feels agreeably philosophic in accumulating evidence on both sides of the question. It is true that he does finally incline to believe in the camp; and, being opposed, indites a pamphlet which he is about to read at the quarterly meeting of the local society when a stroke lays him low, and his last conscious thoughts are not of wife or child, but of the camp and that arrowhead there, which is now in the case at the local museum, together with the foot of a Chinese murderess, a handful of Elizabethan nails, a great many Tudor clay pipes, a piece of Roman pottery, and thewine-glass that Nelson drank out of--proving I really don't know what.No, no, nothing is proved, nothing is known. And if I were to get up at this very moment and ascertain that the mark on the wall is really--what shall we say?--the head of a gigantic old nail, driven in two hundred years ago, which has now, owing to the patient attrition of manygenerations of housemaids, revealed its head above the coat of paint, and is taking its first view of modern life in the sight of a white-walled fire-lit room, what should I gain?--Knowledge? Matter for further speculation? I can think sitting still as well as standing up. And what is knowledge? What are our learned men save the descendants of witches and hermits who crouched in caves and in woods brewing herbs, interrogating shrew-mice and writing down the language of the stars? And the less we honour them as our superstitions dwindle and our respect for beauty and health of mind increases. . . Yes, one could imagine a very pleasant world. A quiet, spacious world, with the flowers so red and blue in the open fields. A world without professors or specialists or house-keepers with the profiles of policemen, a world which one could slice with one's thought as a fish slices the water with his fin, grazing the stems of the water-lilies, hanging suspended over nests of white sea eggs. . . How peaceful it is drown here, rooted in the centre of the world and gazing up through the grey waters, with their sudden gleams of light, and their reflections--if it were not for Whitaker's Almanack--if it were not for the Table of Precedency!I must jump up and see for myself what that mark on the wall really is--a nail, a rose-leaf, a crack in the wood?Here is nature once more at her old game of self-preservation. This train of thought, she perceives, is threatening mere waste of energy, even some collision with reality, for who will ever be able to lift a finger against Whitaker's Table of Precedency? The Archbishop of Canterbury is followed by the Lord High Chancellor; the Lord High Chancellor is followed by the Archbishop of York. Everybody follows somebody, such is the philosophy of Whitaker; and the great thing is to know who follows whom. Whitaker knows, and let that, so Nature counsels, comfort you, instead of enraging you; and if you can't be comforted, if you must shatter this hour of peace, think of the mark on the wall.I understand Nature's game--her prompting to take action as a way of ending any thought that threatens to excite or to pain. Hence, I suppose, comes our slight contempt for men ofaction--men, we assume, who don't think. Still, there's no harm in putting a full stop to one's disagreeable thoughts by looking at a mark on the wall.Indeed, now that I have fixed my eyes upon it, I feel that I have grasped a plank in the sea; I feel a satisfying sense of reality which at once turns the two Archbishops and the Lord High Chancellor to the shadows of shades. Here is something definite, something real. Thus, waking from a midnight dream of horror, one hastily turns on the light and lies quiescent, worshipping the chest of drawers, worshipping solidity, worshipping reality, worshipping the impersonal world which is a proof of some existence other than ours. That is what one wants to be sure of. . . Wood is a pleasant thing to think about. It comes from a tree; and trees grow, and we don't know how they grow. For years and years they grow, without paying any attention to us, in meadows, in forests, and by the side of rivers--all things one likes to think about. The cows swish their tails beneath them on hot afternoons; they paint rivers so green that when a moorhen dives one expects to see its feathers all green when it comes up again. I like to think of the fish balanced against the stream like flags blown out; and of water-beetles slowly raiding domes of mud upon the bed of the river. I like to think of the tree itself:--first the close dry sensation of being wood; then the grinding of the storm; then the slow, delicious ooze of sap. I like to think of it, too, on winter's nights standing in the empty field with all leaves close-furled, nothing tender exposed to the iron bullets of the moon, a naked mast upon anearth that goes tumbling, tumbling, all night long. The song of birds must sound very loud and strange in June; and how cold the feet of insects must feel upon it, as they make laborious progresses up the creases of the bark, or sun themselves upon the thin green awning of the leaves, and look straight in front of them with diamond-cut red eyes. . . One by one the fibres snap beneath the immense cold pressure of the earth, then the last storm comes and, falling, the highest branches drive deep into the ground again. Even so, life isn't done with; there are a million patient, watchful lives still for a tree, all over the world, in bedrooms, in ships, on the pavement, lining rooms, where men and women sit after tea, smoking cigarettes. It is full of peaceful thoughts, happy thoughts, this tree. I should like to take each one separately--but something is getting in the way. . . Where was I? What has it all been about? A tree? A river? The Downs? Whitaker's Almanack? The fields of asphodel? I can't remember a thing. Everything's moving, falling, slipping, vanishing. . . There is a vast upheaval of matter. Someone is standing over me and saying—"I'm going out to buy a newspaper.""Yes?""Though it's no good buying newspapers. . . Nothing ever happens. Curse this war; God damn this war! . . . All the same, I don't see why we should have a snail on our wall."Ah, the mark on the wall! It was a snail.。

黑猫系列英语读物

黑猫系列英语读物Title: The Black Cat Chronicles: An Exploration of Mystery, Myth, and MagicIntroduction:In the realm of literature, certain motifs captivate the imagination with an irresistible allure. Among these, the figure of the black cat stands as an enigmatic symbol, weaving its way through the tapestry of storytelling across cultures and centuries. From ancient mythologies to modern fiction, the black cat's presence evokes a sense of mystery, intrigue, and even superstition. In this exploration, we delve into the rich tapestry of black cat narratives, tracing their origins, unraveling their significance, and unraveling the threads that bind them to the human psyche.Chapter 1: Origins and MythologiesThe black cat's association with mystery and magic finds its roots in ancient mythologies. In Egyptian culture, the goddess Bastet, depicted with the head of a lioness or domestic cat, was revered as a guardian of home and hearth. Her counterpart, the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet, embodied ferocity and protection. Cats, especially black ones, were considered sacred symbols of these deities, and their presence was believed to ward off evil spirits.Similarly, in Celtic folklore, black cats were associated with the Otherworld and supernatural powers. They were believed to be shape-shifters, capable of crossing between realms and serving as guides to the spirit world. Their sleek forms and piercing eyes inspired both fear and reverence among ancient Celts, who saw them as omens of fortune or doom depending on the circumstances.Chapter 2: Superstitions and FolkloreAs civilizations evolved, so too did the superstitions surrounding black cats. In medieval Europe, the association between black cats and witchcraft reached its zenith. During the witch hunts of the Middle Ages, these animals were often scapegoated as familiars of witches, accused of carrying out malevolent deeds under the cover of darkness. Their sleek, shadowy appearance and nocturnal habits fueled fears of the unknown, leading to widespread persecution and superstition.Even today, remnants of these superstitions persist in certain cultures, where black cats are still viewed with suspicion or fear. In some communities, crossing paths with a black cat is considered an omen of bad luck, while in others, it is seen as a harbinger of prosperity. These contradictory beliefs speak to the enduring enigma of the black cat and its ability to evoke a myriad of emotions in the human psyche.Chapter 3: Literary RepresentationsIn literature, the black cat has served as a potentsymbol of mystery and ambiguity. Edgar Allan Poe's seminal tale, "The Black Cat," explores themes of guilt, madness, and the uncanny through the lens of a narrator tormented byvisions of a malevolent feline. The cat, named Pluto, becomes a manifestation of the protagonist's inner demons, haunting him with its spectral presence and driving him to the brinkof insanity.Similarly, in Neil Gaiman's "The Price," a black cat named Tibbles serves as a guardian of the border between life and death, guiding souls to their final resting place.Gaiman's portrayal of the black cat as a wise and enigmatic figure reflects the enduring mystique of these creatures in popular culture.Chapter 4: Contemporary InterpretationsIn the modern era, black cats continue to inspire writers, artists, and filmmakers with their timeless allure. From themagical realism of Haruki Murakami's "Kafka on the Shore" to the whimsical charm of Studio Ghibli's animated film "Kiki's Delivery Service," black cats often feature prominently in contemporary narratives as symbols of intuition, mystery, and companionship.Conclusion:In conclusion, the black cat stands as a multifaceted symbol, embodying themes of mystery, magic, and the unknown. From ancient mythologies to modern literature, its presence resonates across cultures and centuries, captivating the human imagination with its enigmatic allure. Whether feared as an omen of misfortune or revered as a guardian of thespirit world, the black cat continues to fascinate and intrigue, reminding us of the enduring power of storytelling to illuminate the mysteries of the human experience.。

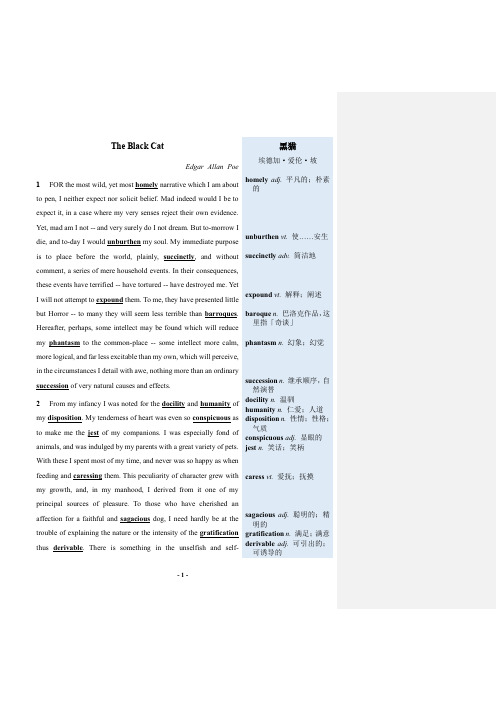

The Black Cat 原典阅读

The Black CatEdgar Allan Poe 1FOR the most wild, yet most homely narrative which I am about to pen, I neither expect nor solicit belief. Mad indeed would I be to expect it, in a case where my very senses reject their own evidence. Yet, mad am I not -- and very surely do I not dream. But to-morrow I die, and to-day I would unburthen my soul. My immediate purpose is to place before the world, plainly, succinctly, and without comment, a series of mere household events. In their consequences, these events have terrified -- have tortured -- have destroyed me. Yet I will not attempt to expound them. To me, they have presented little but Horror -- to many they will seem less terrible than barroques. Hereafter, perhaps, some intellect may be found which will reduce my phantasm to the common-place -- some intellect more calm, more logical, and far less excitable than my own, which will perceive, in the circumstances I detail with awe, nothing more than an ordinary succession of very natural causes and effects.2From my infancy I was noted for the docility and humanity of my disposition. My tenderness of heart was even so conspicuous as to make me the jest of my companions. I was especially fond of animals, and was indulged by my parents with a great variety of pets. With these I spent most of my time, and never was so happy as when feeding and caressing them. This peculiarity of character grew with my growth, and, in my manhood, I derived from it one of my principal sources of pleasure. To those who have cherished an affection for a faithful and sagacious dog, I need hardly be at the trouble of explaining the nature or the intensity of the gratification thus derivable. There is something in the unselfish and self-黑猫埃德加·爱伦·坡homely adj.平凡的;朴素的unburthen vt. 使……安生succinctly adv.简洁地expound vt.解释;阐述baroque n.巴洛克作品,这里指「奇谈」phantasm n.幻象;幻觉succession n.继承顺序,自然演替docility n.温驯humanity n.仁爱;人道disposition n.性情;性格;气质conspicuous adj.显眼的jest n.笑话;笑柄caress vt.爱抚;抚摸sagacious adj.聪明的;精明的gratification n.满足;满意derivable adj.可引出的;可诱导的- 1 -sacrificing love of a brute, which goes directly to the heart of him who has had frequent occasion to test the paltry friendship and gossamer fidelity of mere Man.3I married early, and was happy to find in my wife a disposition not uncongenial with my own. Observing my partiality for domestic pets, she lost no opportunity of procuring those of the most agreeable kind. We had birds, gold-fish, a fine dog, rabbits, a small monkey, and a cat.4This latter was a remarkably large and beautiful animal, entirely black, and sagacious to an astonishing degree. In speaking of his intelligence, my wife, who at heart was not a little tinctured with superstition, made frequent allusion to the ancient popular notion, which regarded all black cats as witches in disguise. Not that she was ever serious upon this point -- and I mention the matter at all for no better reason than that it happens, just now, to be remembered.5Pluto -- this was the cat's name -- was my favorite pet and playmate. I alone fed him, and he attended me wherever I went about the house. It was even with difficulty that I could prevent him from following me through the streets.6Our friendship lasted, in this manner, for several years, during which my general temperament and character -- through the instrumentality of the Fiend Intemperance -- had (I blush to confess it) experienced a radical alteration for the worse. I grew, day by day, more moody, more irritable, more regardless of the feelings of others. I suffered myself to use intemperate language to my wife. At length, I even offered her personal violence. My pets, of course, were made to feel the change in my disposition. I not only neglected, but ill-used them. For Pluto, however, I still retained sufficient regard to paltry n.微不足道的;毫无价值的gossamer adj.轻而薄的;虚无飘渺的uncongenial adj.志趣不相投的tincture vt. 使……染上颜色allusion n. 影射;暗指attend vt.陪伴;伴随the Fiend Intemperance 恶魔的放纵moody adj.喜怒无常的;情绪多变的irritable adj.易怒的;急躁的intemperate adj.无节制的;放纵的- 2 -restrain me from maltreating him, as I made no scruple of maltreating the rabbits, the monkey, or even the dog, when by accident, or through affection, they came in my way. But my disease grew upon me -- for what disease is like Alcohol! -- and at length even Pluto, who was now becoming old, and consequently somewhat peevish -- even Pluto began to experience the effects of my ill temper. 7One night, returning home, much intoxicated, from one of my haunts about town, I fancied that the cat avoided my presence. I seized him; when, in his fright at my violence, he inflicted a slight wound upon my hand with his teeth. The fury of a demon instantly possessed me. I knew myself no longer. My original soul seemed, at once, to take its flight from my body; and a more than fiendish malevolence, gin-nurtured, thrilled every fibre of my frame. I took from my waistcoat-pocket a pen-knife, opened it, grasped the poor beast by the throat, and deliberately cut one of its eyes from the socket! I blush, I burn, I shudder, while I pen the damnable atrocity. 8When reason returned with the morning -- when I had slept off the fumes of the night's debauch -- I experienced a sentiment half of horror, half of remorse, for the crime of which I had been guilty; but it was, at best, a feeble and equivocal feeling, and the soul remained untouched. I again plunged into excess, and soon drowned in wine all memory of the deed.9In the meantime the cat slowly recovered. The socket of the lost eye presented, it is true, a frightful appearance, but he no longer appeared to suffer any pain. He went about the house as usual, but, as might be expected, fled in extreme terror at my approach. I had so much of my old heart left, as to be at first grieved by this evident dislike on the part of a creature which had once so loved me. But this feeling soon gave place to irritation. And then came, as if to my final maltreat vt.虐待scruple n. 顾忌;良心上的不安Pluto这个名字有什么含义?peevish adj.脾气坏的intoxicated adj. 醉醺醺的fury n.狂怒;暴怒demon n.恶魔malevolence n.恶意gin-nurtured adj.酒性大发的thrill vt.使……激动damnable adj.极坏的atrocity n.暴行;凶残fume n.愤怒;烦恼debauch n.放纵,这里意为「罪孽」sentiment n.情绪;多愁善感remorse adj. 悔恨;自责feeble adj.虚弱的;衰弱的equivocal adj.模糊的grieve vt.使……伤心- 3 -and irrevocable overthrow, the spirit of PERVERSENESS. Of this spirit philosophy takes no account. Yet I am not more sure that my soul lives, than I am that perverseness is one of the primitive impulses of the human heart -- one of the indivisible primary faculties, or sentiments, which give direction to the character of Man. Who has not, a hundred times, found himself committing a vile or a silly action, for no other reason than because he knows he should not? Have we not a perpetual inclination, in the teeth of our best judgment, to violate that which is Law, merely because we understand it to be such? This spirit of perverseness, I say, came to my final overthrow. It was this unfathomable longing of the soul to vex itself -- to offer violence to its own nature -- to do wrong for the wrong's sake only -- that urged me to continue and finally to consummate the injury I had inflicted upon the unoffending brute. One morning, in cool blood, I slipped a noose about its neck and hung it to the limb of a tree; -- hung it with the tears streaming from my eyes, and with the bitterest remorse at my heart; -- hung it because I knew that it had loved me, and because I felt it had given me no reason of offence; -- hung it because I knew that in so doing I was committing a sin -- a deadly sin that would so jeopardize my immortal soul as to place it -- if such a thing were possible -- even beyond the reach of the infinite mercy of the Most Merciful and Most Terrible God.10On the night of the day on which this cruel deed was done, I was aroused from sleep by the cry of fire. The curtains of my bed were in flames. The whole house was blazing. It was with great difficulty that my wife, a servant, and myself, made our escape from the conflagration. The destruction was complete. My entire worldly wealth was swallowed up, and I resigned myself thenceforward to irrevocable adj. 不可改变的;不能挽回的overthrow n.征服;打倒perverseness n. 邪恶vile adj.恶劣的,这里活用作名词「恶事」perpetual adj.永恒的;永久性inclination n. 倾向;爱好unfathomable adj.高深莫测的,难以了解的vex vt. 使……烦恼;使……苦恼consummate vt.使……完成noose n. 套索jeopardize vt.危机;损害conflagration n.大火resign oneself to 听从;顺从thenceforward adv.从那以后- 4 -- 5 -despair.11 I am above the weakness of seeking to establish a sequence ofcause and effect, between the disaster and the atrocity. But I am detailing a chain of facts -- and wish not to leave even a possible link imperfect. On the day succeeding the fire, I visited the ruins. The walls, with one exception, had fallen in. This exception was found in a compartment wall, not very thick, which stood about the middle of the house, and against which had rested the head of my bed. The plastering had here, in great measure, resisted the action of the fire -- a fact which I attributed to its having been recently spread. About this wall a dense crowd were collected, and many persons seemed to be examining a particular portion of it with very minute and eager attention. The words "strange!" "singular!" and other similar expressions, excited my curiosity. I approached and saw, as if gravenin bas relief upon the white surface, the figure of a gigantic cat. The impression was given with an accuracy truly marvellous. There was a rope about the animal's neck. 12 When I first beheld this apparition -- for I could scarcely regardit as less -- my wonder and my terror were extreme. But at length reflection came to my aid. The cat, I remembered, had been hung ina garden adjacent to the house. Upon the alarm of fire, this garden had been immediately filled by the crowd -- by some one of whomthe animal must have been cut from the tree and thrown, through an open window, into my chamber. This had probably been done withthe view of arousing me from sleep. The falling of other walls had compressed the victim of my cruelty into the substance of thefreshly-spread plaster; the lime of which, with the flames, and the ammonia from the carcass , had then accomplished the portraiture asI saw it.plastering n. 石膏工艺grave vi. 雕刻bas relief 基线浮雕gigantic adj. 巨大的;庞大的behold vt. 看到;注释at length 终于adjacent adj. 相邻的;邻近的compress vt. 压缩;压紧ammonia n. 氨气carcass n. (动物的)尸体13Although I thus readily accounted to my reason, if not altogether to my conscience, for the startling fact just detailed, it did not the less fail to make a deep impression upon my fancy. For months I couldnot rid myself of the phantasm of the cat; and, during this period, there came back into my spirit a half-sentiment that seemed, but was not, remorse. I went so far as to regret the loss of the animal, and to look about me, among the vile haunts which I now habitually frequented, for another pet of the same species, and of somewhat similar appearance, with which to supply its place.14One night as I sat, half stupified, in a den of more than infamy, my attention was suddenly drawn to some black object, reposing upon the head of one of the immense hogsheads of Gin, or of Rum, which constituted the chief furniture of the apartment. I had been looking steadily at the top of this hogshead for some minutes, and what now caused me surprise was the fact that I had not sooner perceived the object thereupon. I approached it, and touched it with my hand. It was a black cat -- a very large one -- fully as large as Pluto, and closely resembling him in every respect but one. Pluto had not a white hair upon any portion of his body; but this cat had a large, although indefinite splotch of white, covering nearly the whole region of the breast.15Upon my touching him, he immediately arose, purred loudly, rubbed against my hand, and appeared delighted with my notice. This, then, was the very creature of which I was in search. I at once offered to purchase it of the landlord; but this person made no claim to it -- knew nothing of it -- had never seen it before.16I continued my caresses, and, when I prepared to go home, the animal evinced a disposition to accompany me. I permitted it to do rid oneself of 摆脱请仔细分析此处叙述者的心理活动和情感变化。

英语作文神奇的猫怎么写

When crafting an essay about a magical cat, you want to weave a narrative that is both enchanting and engaging. Heres a stepbystep guide to writing an English essay on this topic:1. Introduction: Start with a captivating opening sentence that introduces the magical cat. You could begin with a description of the cats appearance or a scene where its magic is first revealed.Example: In the heart of a mystical forest, where the moonlight danced upon the leaves, lived a cat unlike any other. Its fur shimmered with the colors of the rainbow, and its eyes held the wisdom of the ages.2. Background: Provide some background information about the cat. How did it become magical? Is it a guardian of a secret or a companion to a magical being?Example: This cat, named Luna, was no ordinary feline. It was born from the union of a star and a wish, given the gift of magic by the ancient spirits of the forest.3. Characteristics: Describe the cats magical abilities. What can it do? How do these powers manifest?Example: Luna had the power to speak in any language, to heal with a gentle touch of its paw, and to transform into a ball of light, traveling across great distances in the blink of an eye.4. Adventures: Narrate some adventures or experiences that highlight the cats magical nature. This could include helping other creatures, solving problems, or exploring magical realms.Example: One day, Luna encountered a lost traveler in the forest. With a flick of its tail, it created a path of glowing lights that led the traveler safely to their destination.5. Challenges: Introduce a challenge or conflict that the magical cat faces. This could be a villain trying to steal its powers or a dilemma that tests its wisdom.Example: However, the magic of Luna was not without its dangers. A cunning sorcerer sought to capture Luna and harness its powers for his own nefarious purposes.6. Resolution: Describe how the cat overcomes the challenge. This should showcase its intelligence, bravery, or the strength of its magical abilities.Example: Luna, using its wit and the guidance of the forest spirits, outsmarted the sorcerer, leading him into a maze of illusions where he was trapped by his own greed.7. Conclusion: End the essay with a reflection on the cats journey and the lessons learned. You could also hint at future adventures or the ongoing impact of the cats magic.Example: As the sun set on another day in the forest, Luna returned to its secret glade, its magic now more cherished than ever. The forest creatures knew that as long as Luna was among them, their world would remain a place of wonder and enchantment.8. Review and Edit: After writing your essay, review it for clarity, grammar, and flow. Ensure that the narrative is cohesive and that the magical elements are wellintegrated into the story.Remember, the key to a successful essay about a magical cat is to let your imagination run wild while maintaining a clear and engaging narrative. Happy writing!。

动画片《花木兰》片尾曲Christina Aguilera《Reflection》双语歌词MV

动画片《花木兰》片尾曲Christina Aguilera《Reflection》双语歌词MV导语:《reflection》为1998年迪士尼公司拍摄的反映中国古代经典人物花木兰故事的卡通片《Mulan》(中文名:花木兰)中的主题曲!以下是小编整理的动画片《花木兰》片尾曲Christina Aguilera 《Reflection》双语歌词MV,欢迎阅读参考!《reflection》为1998年迪士尼公司拍摄的反映中国古代经典人物花木兰故事的卡通片《Mulan》(中文名:花木兰)中的主题曲,演唱者是克里斯汀娜·阿圭莱拉。

当年这首歌还被提名为金球奖最佳原创歌曲,1999年被收录于Christina的第一张同名专辑中。

该曲为中英双版,中文版歌曲名为《自己》,由李玟演唱。

Christina在经理人的面前清唱了自己最喜欢的歌手Etta James 的At Last,唱出了高音“E”音阶(比高音"C"还要高),之后她被挑选演唱其电影的主题曲"Reflection"。

两天之内,Christina在日本就录制好了这首歌,录制这首歌曲使她在同一周内得到了RCA Records的唱片合约。

"Reflection"在成人单曲榜最高名次为第十九名,不仅如此,当年这首歌还被提名为金球奖最佳原创歌曲。

1999年该曲被收录于Christina的第一张同名专辑中。

该曲为中英双版,中文版歌曲名为《自己》,由李玟演唱。

Reflection——Christina AguileraLook at me看着我You may think you see who I really am 也许你认为这就是我But you’ll never know me但你不了解我Everyday每一天It’s as if I play a part都像是演戏Now I see现在我已觉醒If I wear a mask如果我永远遮掩自己I can fool the world只能欺骗世界But i cannot fool my heart却无法欺骗自己的心Who is that girl I see我看到的女孩是谁Staring straight back at me?那个直盯着我的女孩When will my reflection showWho I am inside?真正的自己I am now in a world where I have to hide my heart 我现在在这个世界上,我必须隐藏我的心And what I believe in我相信But somehow I will show the world但不知何故在这遮掩信仰的世界里What’s inside my heart这里面有我的心声And be loved for who I am它也爱着我Who is that girl I see我看到的女孩是谁Staring straight back at me?那个直盯着我的女孩Why is my reflection someone I don’t know?为什么我的倒影只是一个陌生人Must I pretend that I’m someone else for all time? 难道我必须躲藏起来装扮成他人When will my reflection showWho I am inside?真正的自己There’s a heart that must be free to fly那里一定是一个可以自由飞翔的灵魂That burns with a need to know the reason why它焚毁了我们必须隐藏自己Why must we all conceal为什么我们必须隐藏吗What we think我们会怎么想How we feel?怎么感觉Must there be a secret me难道我只能成为秘密I’m forced to hide?我不得不隐藏I won’t pretend that I’m someone else for all time 我不会假装别人When willl my reflection show当我的倒影里Who I am inside?是我真正的自己When will my reflection show当我的倒影里Who I am inside?是我真正的自己[动画片《花木兰》片尾曲Christina Aguilera《Reflection》双语歌词MV]。