Knowledge and Social Capital

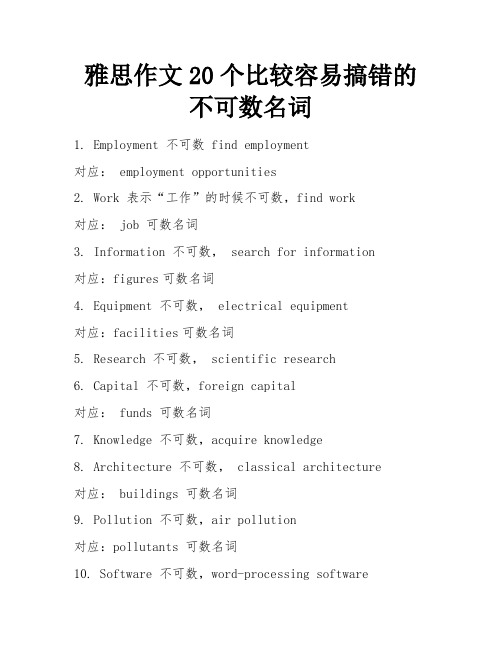

雅思作文20个比较容易搞错的不可数名词

雅思作文20个比较容易搞错的不可数名词1. Employment 不可数 find employment对应: employment opportunities2. Work 表示“工作”的时候不可数,find work对应: job 可数名词3. Information 不可数, search for information对应:figures可数名词4. Equipment 不可数, electrical equipment对应:facilities可数名词5. Research 不可数, scientific research6. Capital 不可数,foreign capital对应: funds 可数名词7. Knowledge 不可数,acquire knowledge8. Architecture 不可数, classical architecture对应: buildings 可数名词9. Pollution 不可数,air pollution对应:pollutants 可数名词10. Software 不可数,word-processing software对应:software packages11. Aid 不可数, financial aid12. News不可数, breaking news对应: news stories13. training不可数, staff training对应:courses14. travel不可数, air travel对应:trips15. Advice不可数, practical advice对应:ideas16. Waste不可数, toxic waste对应:Landfills17. Progress不可数, social progress对应:advances18. Labour不可数, manual labour对应:workers19. Access不可数, internet access20. Transport不可数, means of transport21 workforce 不可数对应: workers22 Advertising 不可数对应:advertisements, or mercials 23 Well-being不可数(自动识别)。

知识管理和知识资本讲义.pptx

何谓知识管理(续)

The majority of Knowledge Management implementations are unsatisfactory as inappropriate, standardised approaches are forced upon the varying predicament of the uninformed by the uninformed.

这是一种以多对少(或对一)的活动,人 们通过这个过程收集已知的相关信息。这 种知识行为可以是隐性的,也可以是显性 的。

This is carried out for the team by the individual researcher or a small group.

这一步骤由个体的研究者或小组完成,其服 务对象是一个团队。

Step 1 - Scanning (2) 第一步:审视(2)

Helped by 促进因素

多数知识管理执行方案之所以不尽如人意,是因为其制定和 执行者的无知。由于为不同的窘境所迫,他们采取了千人一 面这样欠妥的方式。

AUTOPOIETICS 自我创生性

SOCIAL CAPITAL Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology

Annu.Rev.Sociol.1998.24:1–24Copyright ©1998by Annual Reviews.All rights reservedSOCIAL CAPITAL:Its Origins andApplications in Modern Sociology Alejandro Portes Department of Sociology,Princeton University,Princeton,New Jersey 08540KEY WORDS:social control,family support,networks,sociabilityA BSTRACTThispaper reviews the origins and definitionsof social capital in the writings of Bourdieu,Loury,and Coleman,among other authors.It distinguishes foursources of social capital and examines their dynamics.Applications of the concept in the sociological literature emphasize its role in social control,infamilysupport,and in benefits mediated by extrafamilial networks.I provideexamples of each of these positive functions.Negative consequences of thesame processes also deserve attention for a balanced picture of the forces at play.I review four such consequences and illustrate them with relevant ex-amples.Recent writings on social capital have extended the concept from an individual asset to a feature of communities and even nations.The final sec-tionsdescribe this conceptual stretch and examine its limitations.I argue that,as shorthand for the positive consequences of sociability,social capitalhas a definite place in sociological theory.However,excessive extensions of the concept may jeopardize its heuristic value.Alejandro Portes:Biographical SketchAlejandroPortes is professor of sociology at Princeton University andfaculty associate of the Woodrow Wilson School of Public Affairs.He for-merly taught at Johns Hopkins where he held the John Dewey Chair in Artsand Sciences,Duke University,and the University of Texas-Austin.In 1997he heldthe Emilio Bacardi distinguished professorship at the University ofMiami.In the same year he was elected president of the American Sociologi-cal Association.Born in Havana,Cuba,he came to the United States in 1960.He was educated at the University of Havana,Catholic University of Argen-tina,and Creighton University.He received his MA and PhD from the Uni-versity of Wisconsin-Madison.0360-0572/98/0815-0001$08.001A n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b yS w i ssAca dem icLi bra ryC onsor t iaon3/24/9.F orpe rsonaluseo nl y.Portes is the author of some 200articles and chapters on national devel-opment,international migration,Latin American and Caribbean urbaniza-tion,and economic sociology.His most recent books include City on the Edge,the Transformation of Miami (winner of the Robert Park award for best book in urban sociology and of the Anthony Leeds award for best book in urban anthropology in 1995);The New Second Generation (Russell Sage Foundation 1996);Caribbean Cities (Johns Hopkins University Press);and Immigrant America,a Portrait.The latter book was designated as a centen-nial publication by the University of California Press.It was originally pub-lished in 1990;the second edition,updated and containing new chapters on American immigration policy and the new second generation,was published in 1996.Introduction During recent years,the concept of social capital has become one of the most popular exports from sociological theory into everyday language.Dissemi-nated by a number of policy-oriented journals and general circulation maga-zines,social capital has evolved into something of a cure-all for the maladies affecting society at home and abroad.Like other sociological concepts that have traveled a similar path,the original meaning of the term and its heuristic value are being put to severe tests by these increasingly diverse applications.As in the case of those earlier concepts,the point is approaching at which so-cial capital comes to be applied to so many events and in so many different contexts as to lose any distinct meaning.Despite its current popularity,the term does not embody any idea really new to sociologists.That involvement and participation in groups can have positive consequences for the individual and the community is a staple notion,dating back to Durkheim’s emphasis on group life as an antidote to anomie and self-destruction and to Marx’s distinction between an atomized class-in-itself and a mobilized and effective class-for-itself.In this sense,the term social capital simply recaptures an insight present since the very beginnings of the disci-pline.Tracing the intellectual background of the concept into classical times would be tantamount to revisiting sociology’s major nineteenth century sources.That exercise would not reveal,however,why this idea has caught on in recent years or why an unusual baggage of policy implications has been heaped on it.The novelty and heuristic power of social capital come from two sources.First,the concept focuses attention on the positive consequences of sociability while putting aside its less attractive features.Second,it places those positive consequences in the framework of a broader discussion of capital and calls atten-tion to how such nonmonetary forms can be important sources of power and in-fluence,like the size of one’s stock holdings or bank account.The potential fungi-bility of diverse sources of capital reduces the distance between the sociologi-2PORTESA n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b y S w i s s A c a d e m i c L i b r a r y C o n s o r t i a o n 03/24/09. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .cal and economic perspectives and simultaneously engages the attention of policy-makers seeking less costly,non-economic solutions to social problems.In the course of this review,I limit discussion to the contemporary reemer-gence of the idea to avoid a lengthy excursus into its classical predecessors.To an audience of sociologists,these sources and the parallels between present so-cial capital discussions and passages in the classical literature will be obvious.I examine,first,the principal authors associated with the contemporary usage of the term and their different approaches to it.Then I review the various mechanisms leading to the emergence of social capital and its principal appli-cations in the research literature.Next,I examine those not-so-desirable con-sequences of sociability that are commonly obscured in the contemporary lit-erature on the topic.This discussion aims at providing some balance to the fre-quently celebratory tone with which the concept is surrounded.That tone is es-pecially noticeable in those studies that have stretched the concept from a property of individuals and families to a feature of communities,cities,and even nations.The attention garnered by applications of social capital at this broader level also requires some discussion,particularly in light of the poten-tial pitfalls of that conceptual stretch.Definitions The first systematic contemporary analysis of social capital was produced by Pierre Bourdieu,who defined the concept as “the aggregate of the actual or po-tential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance or recognition”(Bourdieu 1985,p.248;1980).This initial treatment of the concept appeared in some brief “Provisional Notes”published in the Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales in 1980.Because they were in French,the article did not gar-ner widespread attention in the English-speaking world;nor,for that matter,did the first English translation,concealed in the pages of a text on the sociol-ogy of education (Bourdieu 1985).This lack of visibility is lamentable because Bourdieu’s analysis is arguably the most theoretically refined among those that introduced the term in contem-porary sociological discourse.His treatment of the concept is instrumental,fo-cusing on the benefits accruing to individuals by virtue of participation in groups and on the deliberate construction of sociability for the purpose of cre-ating this resource.In the original version,he went as far as asserting that “the profits which accrue from membership in a group are the basis of the solidarity which makes them possible”(Bourdieu 1985,p.249).Social networks are not a natural given and must be constructed through investment strategies oriented to the institutionalization of group relations,usable as a reliable source of other benefits.Bourdieu’s definition makes clear that social capital is decomposable into two elements:first,the social relationship itself that allows individuals to SOCIAL CAPITAL:ORIGINS AND APPLICATIONS 3A n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b y S w i s s A c a d e m i c L i b r a r y C o n s o r t i a o n 03/24/09. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .claim access to resources possessed by their associates,and second,the amount and quality of those resources.Throughout,Bourdieu’s emphasis is on the fungibility of different forms of capital and on the ultimate reduction of all forms to economic capital,defined as accumulated human labor.Hence,through social capital,actors can gain di-rect access to economic resources (subsidized loans,investment tips,protected markets);they can increase their cultural capital through contacts with experts or individuals of refinement (i.e.embodied cultural capital);or,alternatively,they can affiliate with institutions that confer valued credentials (i.e.institu-tionalized cultural capital).On the other hand,the acquisition of social capital requires deliberate invest-ment of both economic and cultural resources.Though Bourdieu insists that the outcomes of possession of social or cultural capital are reducible to economic capital,the processes that bring about these alternative forms are not.They each possess their own dynamics,and,relative to economic exchange,they are characterized by less transparency and more uncertainty.For example,trans-actions involving social capital tend to be characterized by unspecified obliga-tions,uncertain time horizons,and the possible violation of reciprocity expec-tations.But,by their very lack of clarity,these transactions can help disguise what otherwise would be plain market exchanges (Bourdieu 1979,1980).A second contemporary source is the work of economist Glen Loury (1977,1981).He came upon the term in the context of his critique of neoclassical theories of racial income inequality and their policy implications.Loury ar-gued that orthodox economic theories were too individualistic,focusing exclu-sively on individual human capital and on the creation of a level field for com-petition based on such skills.By themselves,legal prohibitions against em-ployers’racial tastes and implementation of equal opportunity programs would not reduce racial inequalities.The latter could go on forever,according to Loury,for two reasons—first,the inherited poverty of black parents,which would be transmitted to their children in the form of lower material resources and educational opportunities;second,the poorer connections of young black workers to the labor market and their lack of information about opportunities:The merit notion that,in a free society,each individual will rise to the level justified by his or her competence conflicts with the observation that no one travels that road entirely alone.The social context within which individual maturation occurs strongly conditions what otherwise equally competent in-dividuals can achieve.This implies that absolute equality of opportunity,…is an ideal that cannot be achieved.(Loury 1977,p.176)Loury cited with approval the sociological literature on intergenerational mobility and inheritance of race as illustrating his anti-individualist argument.However,he did not go on to develop the concept of social capital in any detail.4PORTESA n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b y S w i s s A c a d e m i c L i b r a r y C o n s o r t i a o n 03/24/09. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .He seems to have run across the idea in the context of his polemic against or-thodox labor economics,but he mentions it only once in his original article and then in rather tentative terms (Loury 1977).The concept captured the differen-tial access to opportunities through social connections for minority and nonmi-nority youth,but we do not find here any systematic treatment of its relations to other forms of capital.Loury’s work paved the way,however,for Coleman’s more refined analy-sis of the same process,namely the role of social capital in the creation of hu-man capital.In his initial analysis of the concept,Coleman acknowledges Loury’s contribution as well as those of economist Ben-Porath and sociolo-gists Nan Lin and Mark Granovetter.Curiously,Coleman does not mention Bourdieu,although his analysis of the possible uses of social capital for the ac-quisition of educational credentials closely parallels that pioneered by the French sociologist.1Coleman defined social capital by its function as “a vari-ety of entities with two elements in common:They all consist of some aspect of social structures,and they facilitate certain action of actors—whether per-sons or corporate actors—within the structure”(Coleman 1988a:p.S98,1990,p.302).This rather vague definition opened the way for relabeling a number of dif-ferent and even contradictory processes as social capital.Coleman himself started that proliferation by including under the term some of the mechanisms that generated social capital (such as reciprocity expectations and group en-forcement of norms);the consequences of its possession (such as privileged access to information);and the “appropriable”social organization that pro-vided the context for both sources and effects to materialize.Resources ob-tained through social capital have,from the point of view of the recipient,the character of a gift.Thus,it is important to distinguish the resources themselves from the ability to obtain them by virtue of membership in different social structures,a distinction explicit in Bourdieu but obscured in Coleman.Equat-ing social capital with the resources acquired through it can easily lead to tau-tological statements.2Equally important is the distinction between the motivations of recipients and of donors in exchanges mediated by social capital.Recipients’desire toSOCIAL CAPITAL:ORIGINS AND APPLICATIONS 51The closest equivalent to human capital in Bourdieu’s analysis is embodied cultural capital,which is defined as the habitus of cultural practices,knowledge,and demeanors learned through exposure to role models in the family and other environments (Bourdieu 1979).2Saying,for example,that student A has social capital because he obtained access to a large tuition loan from his kin and that student B does not because she failed to do so neglects the possibility that B’s kin network is equally or more motivated to come to her aid but simply lacks the means to do.Defining social capital as equivalent with the resources thus obtained is tantamount to saying that the successful succeed.This circularity is more evident in applications of social capital that define it as a property of collectivities.These are reviewed below.A n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b y S w i s s A c a d e m i c L i b r a r y C o n s o r t i a o n 03/24/09. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .gain access to valuable assets is readily understandable.More complex are the motivations of the donors,who are requested to make these assets available without any immediate return.Such motivations are plural and deserve analy-sis because they are the core processes that the concept of social capital seeks to capture.Thus,a systematic treatment of the concept must distinguish among:(a )the possessors of social capital (those making claims);(b )the sources of social capital (those agreeing to these demands);(c )the resources themselves.These three elements are often mixed in discussions of the concept following Coleman,thus setting the stage for confusion in the uses and scope of the term.Despite these limitations,Coleman’s essays have the undeniable merit of introducing and giving visibility to the concept in American sociology,high-lighting its importance for the acquisition of human capital,and identifying some of the mechanisms through which it is generated.In this last respect,his discussion of closure is particularly enlightening.Closure means the existence of sufficient ties between a certain number of people to guarantee the obser-vance of norms.For example,the possibility of malfeasance within the tightly knit community of Jewish diamond traders in New York City is minimized by the dense ties among its members and the ready threat of ostracism against vio-lators.The existence of such a strong norm is then appropriable by all members of the community,facilitating transactions without recourse to cumbersome legal contracts (Coleman 1988a:S99).After Bourdieu,Loury,and Coleman,a number of theoretical analyses of social capital have been published.In 1990,WE Baker defined the concept as “a resource that actors derive from specific social structures and then use to pursue their interests;it is created by changes in the relationship among actors”(Baker 1990,p.619).More broadly,M Schiff defines the term as “the set of elements of the social structure that affects relations among people and are in-puts or arguments of the production and/or utility function”(Schiff 1992,p.161).Burt sees it as “friends,colleagues,and more general contacts through whom you receive opportunities to use your financial and human capital”(Burt 1992,p.9).Whereas Coleman and Loury had emphasized dense net-works as a necessary condition for the emergence of social capital,Burt high-lights the opposite situation.In his view,it is the relative absence of ties,la-beled “structural holes,”that facilitates individual mobility.This is so because dense networks tend to convey redundant information,while weaker ties can be sources of new knowledge and resources.Despite these differences,the consensus is growing in the literature that so-cial capital stands for the ability of actors to secure benefits by virtue of mem-bership in social networks or other social structures.This is the sense in which it has been more commonly applied in the empirical literature although,as we will see,the potential uses to which it is put vary greatly.6PORTESA n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b y S w i s s A c a d e m i c L i b r a r y C o n s o r t i a o n 03/24/09. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .Sources of Social CapitalBoth Bourdieu and Coleman emphasize the intangible character of social capital relative to other forms.Whereas economic capital is in people’s bank accounts and human capital is inside their heads,social capital inheres in the structure of their relationships.To possess social capital,a person must be related to others,and it is those others,not himself,who are the actual source of his or her advan-tage.As mentioned before,the motivation of others to make resources avail-able on concessionary terms is not uniform.At the broadest level,one may dis-tinguish between consummatory versus instrumental motivations to do so.As examples of the first,people may pay their debts in time,give alms to charity,and obey traffic rules because they feel an obligation to behave in this manner.The internalized norms that make such behaviors possible are then ap-propriable by others as a resource.In this instance,the holders of social capital are other members of the community who can extend loans without fear of nonpayment,benefit from private charity,or send their kids to play in the street without concern.Coleman (1988a:S104)refers to this source in his analysis of norms and sanctions:“Effective norms that inhibit crime make it possible to walk freely outside at night in a city and enable old persons to leave their houses without fear for their safety.”As is well known,an excessive emphasis on this process of norm internalization led to the oversocialized conception of human action in sociology so trenchantly criticized by Wrong (1961).An approach closer to the undersocialized view of human nature in modern economics sees social capital as primarily the accumulation of obligations from others according to the norm of reciprocity.In this version,donors pro-vide privileged access to resources in the expectation that they will be fully re-paid in the future.This accumulation of social chits differs from purely eco-nomic exchange in two aspects.First,the currency with which obligations are repaid may be different from that with which they were incurred in the first place and may be as intangible as the granting of approval or allegiance.Sec-ond,the timing of the repayment is unspecified.Indeed,if a schedule of repay-ments exists,the transaction is more appropriately defined as market exchange than as one mediated by social capital.This instrumental treatment of the term is quite familiar in sociology,dating back to the classical analysis of social ex-change by Simmel ([1902a]1964),the more recent ones by Homans (1961)and Blau (1964),and extensive work on the sources and dynamics of reciproc-ity by authors of the rational action school (Schiff 1992,Coleman 1994).Two other sources of social capital exist that fit the consummatory versus instrumental dichotomy,but in a different way.The first finds its theoretical underpinnings in Marx’s analysis of emergent class consciousness in the in-dustrial proletariat.By being thrown together in a common situation,workers learn to identify with each other and support each other’s initiatives.This soli-SOCIAL CAPITAL:ORIGINS AND APPLICATIONS 7A n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b y S w i s s A c a d e m i c L i b r a r y C o n s o r t i a o n 03/24/09. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .darity is not the result of norm introjection during childhood,but is an emer-gent product of a common fate (Marx [1894]1967,Marx &Engels [1848]1947).For this reason,the altruistic dispositions of actors in these situations are not universal but are bounded by the limits of their community.Other members of the same community can then appropriate such dispositions and the actions that follow as their source of social capital.Bounded solidarity is the term used in the recent literature to refer to this mechanism.It is the source of social capital that leads wealthy members of a church to anonymously endow church schools and hospitals;members of a suppressed nationality to voluntarily join life-threatening military activities in its defense;and industrial proletarians to take part in protest marches or sym-pathy strikes in support of their fellows.Identification with one’s own group,sect,or community can be a powerful motivational force.Coleman refers to extreme forms of this mechanism as “zeal”and defines them as an effective an-tidote to free-riding by others in collective movements (Coleman 1990,pp.273–82;Portes &Sensenbrenner 1993).The final source of social capital finds its classical roots in Durkheim’s ([1893]1984)theory of social integration and the sanctioning capacity of group rituals.As in the case of reciprocity exchanges,the motivation of donors of socially mediated gifts is instrumental,but in this case,the expectation of re-payment is not based on knowledge of the recipient,but on the insertion of both actors in a common social structure.The embedding of a transaction into suchstructure has two consequences.First,the donor’s returns may come not8PORTESFigure 1Actual and potential gains and losses in transactions mediated by social capitalA n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b y S w i s s A c a d e m i c L i b r a r y C o n s o r t i a o n 03/24/09. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .directly from the recipient but from the collectivity as a whole in the form of status,honor,or approval.Second,the collectivity itself acts as guarantor that whatever debts are incurred will be repaid.As an example of the first consequence,a member of an ethnic group may endow a scholarship for young co-ethnic students,thereby expecting not re-payment from recipients but rather approval and status in the collectivity.The students’social capital is not contingent on direct knowledge of their benefac-tor,but on membership in the same group.As an example of the second effect,a banker may extend a loan without collateral to a member of the same relig-ious community in full expectation of repayment because of the threat of com-munity sanctions and ostracism.In other words,trust exists in this situation precisely because obligations are enforceable,not through recourse to law or violence but through the power of the community.In practice,these two effects of enforceable trust are commonly mixed,as when someone extends a favor to a fellow member in expectation of both guaranteed repayment and group approval.As a source of social capital,en-forceable trust is hence appropriable by both donors and recipients:For recipi-ents,it obviously facilitates access to resources;for donors,it yields approval and expedites transactions because it ensures against malfeasance.No lawyer need apply for business transactions underwritten by this source of social capi-tal.The left side of Figure 1summarizes the discussion in this section.Keeping these distinctions in mind is important to avoid confusing consummatory and instrumental motivations or mixing simple dyadic exchanges with those em-bedded in larger social structures that guarantee their predictability and course.Effects of Social Capital:Recent Research Just as the sources of social capital are plural so are its consequences.The em-pirical literature includes applications of the concept as a predictor of,among others,school attrition and academic performance,children’s intellectual de-velopment,sources of employment and occupational attainment,juvenile de-linquency and its prevention,and immigrant and ethnic enterprise.3Diversity of effects goes beyond the broad set of specific dependent variables to which social capital has been applied to encompass,in addition,the character and meaning of the expected consequences.A review of the literature makes it pos-sible to distinguish three basic functions of social capital,applicable in a vari-ety of contexts:(a )as a source of social control;(b )as a source of family sup-port;(c )as a source of benefits through extrafamilial networks.SOCIAL CAPITAL:ORIGINS AND APPLICATIONS 93The following review does not aim at an exhaustive coverage of the empirical literature.That task has been rendered obsolete by the advent of computerized topical searches.My purpose instead is to document the principal types of application of the concept in the literature and to highlight their interrelationships.A n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b y S w i s s A c a d e m i c L i b r a r y C o n s o r t i a o n 03/24/09. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .As examples of the first function,we find a series of studies that focus on rule enforcement.The social capital created by tight community networks is useful to parents,teachers,and police authorities as they seek to maintain dis-cipline and promote compliance among those under their charge.Sources of this type of social capital are commonly found in bounded solidarity and en-forceable trust,and its main result is to render formal or overt controls unnec-essary.The process is exemplified by Zhou &Bankston’s study of the tightly knit Vietnamese community of New Orleans:Both parents and children are constantly observed as under a “Vietnamese microscope.”If a child flunks out or drops out of a school,or if a boy falls into a gang or a girl becomes pregnant without getting married,he or she brings shame not only to himself or herself but also to the family.(Zhou &Bankston 1996,p.207)The same function is apparent in Hagan et al’s (1995)analysis of right-wing extremism among East German beling right-wing extremism a sub-terranean tradition in German society,these authors seek to explain the rise of that ideology,commonly accompanied by anomic wealth aspirations among German adolescents.These tendencies are particularly strong among those from the formerly communist eastern states.That trend is explained as the joint outcome of the removal of social controls (low social capital),coupled with the long deprivations endured by East Germans.Incorporation into the West has brought about new uncertainties and the loosening of social integration,thus allowing German subterranean cultural traditions to re-emerge.Social control is also the focus of several earlier essays by Coleman,who laments the disappearance of those informal family and community structures that produced this type of social capital;Coleman calls for the creation of for-mal institutions to take their place.This was the thrust of Coleman’s 1992presidential address to the American Sociological Association,in which he traced the decline of “primordial”institutions based on the family and their re-placement by purposively constructed organizations.In his view,modern soci-ology’s task is to guide this process of social engineering that will substitute obsolete forms of control based on primordial ties with rationally devised ma-terial and status incentives (Coleman 1988b,1993).The function of social capital for social control is also evident whenever the concept is discussed in conjunction with the law (Smart 1993,Weede 1992).It is as well the central focus when it is defined as a property of collectivities such as cities or nations.This latter approach,associated mainly with the writings of political scientists,is discussed in a following section.The influence of Coleman’s writings is also clear in the second function of social capital,namely as a source of parental and kin support.Intact families and those where one parent has the primary task of rearing children possess 10PORTESA n n u . R e v . S o c i o l . 1998.24:1-24. D o w n l o a d e d f r o m a r j o u r n a l s .a n n u a l r e v i e w s .o r g b y S w i s s A c a d e m i c L i b r a r y C o n s o r t i a o n 03/24/09. F o r p e r s o n a l u s e o n l y .。

Audit fees and social captial 审计费用与社会资本

THE ACCOUNTING REVIEW American Accounting Association Vol.90,No.2DOI:10.2308/accr-50878 2015pp.611–639Audit Fees and Social CapitalAnand JhaYu ChenTexas A&M International UniversityABSTRACT:We examine the impact of social capital on audit fees.We find that firmsheadquartered in U.S.counties with high social capital pay lower audit fees.Socialcapital measures the level of mutual trust in a region.Our results suggest that auditorsjudge the trustworthiness of their clients based on where the firm is headquartered andcharge a premium when they trust the firm less.The basis of our results is theexamination of more than28,000audit fees for more than5,000firms spanning theperiod of2000to2009.The results are robust to controlling for a large number of firm-level and county-level characteristics.Keywords:audit fees;social capital;client risk;audit effort.JEL Classifications:M42;M14.I.INTRODUCTIONI n a seminal paper,Simunic(1980)considers afirm’s audit fees to be dependent on theauditor’s effort and the expected losses from litigation.Subsequently,researchers have investigated the impact of numerous variables as possible determinants of audit fees (Causholli,De Martinis,Hay,and Knechel2010).These variables are expected to affect either the auditor’s effort or litigation risk,both of which affect the audit fees.Prior research has not investigated the possible impact of the clientfirm’s local social environment,which is the focal point of this study.Our purpose is to use a well-understood setting to investigate the role of social capital on economic decisions,a topic that is much less understood.Social capital is often defined as the mutual trust in society.We propose that the social capital in the county where a U.S.firm is headquartered can have an impact on how much the auditors trust the managers of thefirm.As we discuss below,auditors arguably have less trust when afirm is headquartered in a county with low social capital.We argue that this lack of trust will increase the auditor’s effort and his or her fear of litigation and,therefore,will increase fees.We test this idea by exploiting the variation in social capital at the county level in the United States. Using the zip code of thefirm’s headquarters,we gather data for variables proxying for the county-levelWe thank Michael L.Ettredge(editor),John Harry Evans III(senior editor),and two anonymous referees for their valuable feedback.We also thank the participants at the2013FMA Annual Conference,2012AAA Annual Meeting, and2012Research Seminar at Texas A&M International University for their suggestions.Editor’s note:Accepted by Michael L.Ettredge.Submitted:November2012Accepted:July2014Published Online:July2014611social capital for each firm-year.We then conduct a regression analysis that examines the association between audit fees and the level of social capital where the firm is headquartered.In our analysis,we control for firm characteristics based on the audit-fee literature and also include a large set of controls at the county level.We find that audit fees are significantly lower in high social-capital counties.Our results are also economically significant because we find that a firm that is headquartered in a county with social capital in the 75th percentile pays about 12percent less in audit fees compared to a firm headquartered in a county with social capital in the 25th percentile,ceteris paribus .According to Simunic (1980),audit fees can increase due to more audit work and/or more expected losses.To further investigate which particular element drives up audit fees,we examine the impact of social capital on the auditor’s report lag,which is a proxy for the auditor’s effort,and on the firm’s litigation risk,which is a proxy for the auditor’s expected losses.We find that auditors take more time to sign off on their report for low social-capital clients.Furthermore,the probability of litigation involving the auditor is also higher in low social-capital counties.We also conduct two tests of moderating effects that examine whether the influence of social capital is stronger under certain environments.First,we investigate whether the effect of social capital is stronger when the audit office is located closer to the client.The idea is that the auditors might have more confidence in their judgment of the client’s trustworthiness when they reside closer.We find results consistent with our expectation because when the auditors are either located within a 100-kilometer (62.13miles)radius of the client or in the same metropolitan statistical area (MSA)as the client,the effect of social capital on audit fees is tripled compared to when they are further away.Second,we investigate if the effect of social capital is stronger for the year 2004and subsequent years,when auditing became more complex due to the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX).We find that,indeed,social capital’s effect is stronger post-2004.Based on prior literature (Guiso,Sapienza,and Zingales 2004,2008b ;Grullon,Kanatas,and Weston 2010),we argue that these two additional results give us greater confidence that our results are causal instead of correlational.Taken together,these results provide strong evidence that auditors take into consideration the social capital of where the firms are headquartered in assessing their audit fees.We note here that our results do not necessarily suggest that auditors are violating professional guidelines that require that they exercise ‘‘professional skepticism ’’in auditing their clients.Rather,the results suggest that the extent of the skepticism can vary based on where their clients are headquartered.Our results can be interpreted as indicating that auditors are prudent in their assessments because the social environment affects the quality of the financial reporting (Kang,Han,Salter,and Yoo 2010;McGuire,Omer,and Sharp 2012).Jha (2013),in particular,finds that when a firm is headquartered in a low social-capital county,the financial report’s quality is poor.Specifically,the accrual management,real earnings management,propensity to commit financial fraud,and the ‘‘fogginess ’’of financial reports are all high.Prudence should dictate that auditors take into account the poor quality of reporting that can generally be expected of clients located in low social-capital counties,and that auditors be more skeptical in those cases.Our results are also consistent with the experimental and archival studies that show that auditors consider the integrity of the management when deciding how much effort to exert in auditing,and how much to charge their client (Beaulieu 2001).By showing that the social capital where the firm is headquartered affects audit fees,our study makes an important contribution to the auditing literature.It shows that the social environment where the firm is headquartered can affect its relation with auditors and,consequently,the audit fees.This is a new way of looking at the auditor and client’s relation.Although the audit-fee literature is extensive,no studies we know of have investigated the possible impact of the social environment on how much the auditors charge.More broadly,our study contributes to an emerging strand of accounting literature that documents the effect of the social environment on managerial decisions (Hilary and Hui 2009;McGuire et al.2012).We show that the social environment not only affects managerial decisions,but also the relations612Jha andChen The Accounting ReviewMarch 2015with other stakeholders,such as auditors.Further,this study is among the few in the accounting literature to examine the role of social capital on thefirm’s behavior.Although the concept of social capital is extensively studied in sociology,economics,management,and political science,the role of social capital in accounting settings is largely unexplored.Our study raises the possibility that other accounting decisions might be affected by the level of social capital where thefirm is headquartered.II.BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENTWhat is Social Capital?Following Woolcock(2001),we define social capital as the norms and the networks that facilitate collective action.A high social-capital region has individuals with a greater propensity to honor an obligation and a greater mutual trust within a much denser network,all of which facilitate collective action.The predominant approach in the economics literature is to view social capital as a‘‘norm’’that facilitates cooperation.Guiso et al.(2004)define social capital as the mutual level of trust and altruistic tendency in a society.Fukuyama(1997)defines social capital as‘‘the existence of a certain set of informal values or norms shared among members of a group that permits cooperation among them.’’Portes(1998)defines social capital as the propensity to honor obligations.Guiso, Sapienza,and Zingales(2008a)provide a more comprehensive definition of social capital as‘‘the set of beliefs and values that foster cooperation.’’In contrast to the‘‘norm’’approach,many studies,particularly in the management literature,model social capital as a set of networks from which benefits are derived(Payne,Moore,Griffis,and Autry 2011).Atfirst glance,these approaches appear as two distinct ways of viewing social capital.In fact,the distinction is not clear.The network definition also implicitly incorporates norms.A strong social network enhances the punishment for deviant behavior and encourages good behavior(Coleman1994; Spagnolo1999).A vigorous network fosters greater trust over time among its members and creates a culture that is more conducive to cooperation.Fukuyama(1997)notes that in a dense network,there are repeated games in which people rely on each other.Over time,this leads to a code of conduct in the society that encourages the propensity to honor obligations and develop mutual trust.Portes(1998) argues that,over time,these morals get passed from one generation to another and get internalized into society.Consequently,people feel obligated to behave in a certain way.Putnam(2001)provides a more detailed analysis of this view.Because of the difficulty of disentangling the effect due to norms versus a network,we do not make this distinction;instead,we focus on the common aspects of both the norms and the network views,following the Woolcock(2001)definition.Social capital gained popularity after Coleman(1988)laid its theoretical foundation by drawing parallels with other types of capital,such asfinancial,physical,and human.Since then,a large body of the literature in different disciplines,such as economics,political science,and management,has examined the impact of social capital(Putnam2000;Woolcock2010;Payne et al. 2011).Documenting the dramatic rise in understanding the role of social capital,Woolcock(2010) notes that in the early1980s,the phrase‘‘social capital’’was used in scholarly articles less than100 times a year,and by2008,it was used16,000times a year.This research shows that social capital is negatively associated with opportunistic behavior such as corruption(La Porta,Lopez-De-Silanes, Shleifer,and Vishny1997),crime(Buonanno,Montolio,and Vanin2009),and transaction costs associated withfinancial exchanges,such as buying stocks and getting loans(Guiso et al.2004). How Can Social Capital Affect Audit Fees?Managers Are More Likely to be Honest in High Social-Capital RegionsThe social norms of high social-capital regions induce managers to behave more honestly.A classic stream of literature supports the view that social norms affect individuals’decisions Audit Fees and Social Capital613The Accounting Review March2015(Milgram,Bickman,and Berkowitz 1969;Cialdini,Kallgren,and Reno 1991).This stream of literature argues that human beings develop a set of ideals for how they should behave based on what they see around them.When a person deviates from these ideals,there is a sense of guilt and,therefore,a cost.Managers might take this cost into account when making decisions (Akerlof 2007).Social norms are also self-enforcing (Hilary and Huang 2013)because there is a desire to conform to a group’s expectations—partly by nature (Akerlof 2007;Hilary and Huang 2013)and partly because deviations are costly (Coleman 1994;Portes 1998).The dense networks in high social-capital regions also encourage honest behavior from managers.In the context of managerial reporting behavior,a dense network means that stakeholders,such as institutional investors,bankers,and managers,are more likely to interact regularly with each other.More frequent interactions among these parties lead to greater information exchange and,therefore,more effective monitoring (Wu 2008),which subsequently leads to more truthful and forthcoming financial reporting.Auditors Factor in the Manager’s Honesty in the Fees They ChargeThe two most important determinants of audit fees are the auditor’s effort and the litigation risk (Simunic 1980;Venkataraman,Weber,and Willenborg 2008).Both are likely to be lower in a high social-capital environment,thus driving down the fees the auditors charge.Social capital arguably affects auditor effort via the audit planning process.Examining entire populations of accounts is too costly,so auditors need to balance the costs and benefits of audit procedures.During the planning process,auditors identify more risky areas and spend more resources on those areas to reduce the audit risk.If auditors feel that management is more prone to misbehavior,then they conduct more substantive procedures to ensure that the financial statements are fairly presented (Beaulieu 2001).In contrast,if auditors trust their clients more,then they place greater reliance on internal controls and perform fewer substantive procedures to reduce their effort.When a firm is located in a high social-capital county,its managers are likely to be more forthcoming and honest in their financial reports,as discussed earlier and as documented in Jha (2013).If the firm’s auditors have this perception,then they will trust the client to a greater extent and thereby reduce their total effort.1Auditors also hire third parties to assess the integrity of management,review past financial information,and communicate with previous auditors (Rittenberg,Johnstone,and Gramling 2012).In a high social-capital county,because of its dense network and the honest reputation of its citizens,the auditor can obtain such evidence more easily,and probably with more precision.For example,the auditor might much more easily obtain a higher quality and quantity of audit evidence from banks,suppliers,customers,and other stakeholders in a high social-capital county.Therefore,the auditor is likely to expend less effort in obtaining sufficient and appropriate audit evidence,resulting in lower audit fees.Auditors also perceive a higher lawsuit risk when firms are located in low social-capital counties because these firms are more likely to misbehave,and third parties might have less favorable opinions about the management.The fear of litigation risk can increase the audit fees because the cost of litigation relative to the audit fees can be severe.An example in Dye (1993)is illustrative:‘‘Max Rothenberg &Company performed an audit review for $600for 1136Tenants’Corporation,but because of alleged deficiencies in the conduct of its engagement,was found liable for $232,278.30.’’A report from the Advisory Committee on the Auditing Profession (ACAP)notes that between 1996and 2008,the six largest auditing firms paid approximately $5.16billion to settle 1The idea that auditors adjust their extent of auditing according to how much they trust their clients is not new.Shaub (1996)notes that ‘‘trust is inherent in the audit process.’’He argues that auditors assess higher inherent risk and control risk when they trust their client less.614Jha andChen The Accounting ReviewMarch 2015lawsuits(ACAP2008).Given the concern about the risk and the cost associated with litigation relative to the fees charged,auditors are likely to take into consideration the trustworthiness of their client,even if the impact of the trust is only at the margin.The discussion above suggests that in a low-trust environment,the auditor’s effort and the litigation risk are both higher.Therefore,auditors likely will exert more effort and demand higher audit fees forfirms located in low social-capital counties.Conversely,they will exert less effort and demand lower audit fees if afirm is headquartered in a high social-capital county.2Based on the above discussion,we propose the following hypothesis:H:Ceteris paribus,thefirms headquartered in a high social-capital county pay lower audit fees.This hypothesis rests on the idea that thefirms headquartered in high social-capital counties have corporate cultures that are high in social capital.This concept is based on the recent accounting andfinance literature on social environment and corporate decisions(Hilary and Hui 2009;Grullon et al.2010).As in these studies,we borrow from the psychology literature and argue thatfirms hire and retain employees who share their own values and that employees prefer to work forfirms that share their own values(Vroom1966;Tom1971;Holland1976;McGuire et al.2012). Over time,assuming that the key employees reside close to thefirm’s headquarters,these shared values mean that the culture of the headquarters also reflects the culture of its location.Therefore,if the county where thefirm is headquartered has low social capital,then the auditor is likely to have less trust in managers employed at thefirm’s headquarters.3III.RESEARCH METHOD AND DATAEmpirical ModelTo test our hypothesis,we use a multivariate regression in which the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of the audit fees charged by the external auditor.The key variable of interest is the social capital of the county where thefirm is headquartered:LNðAUDIT FEEÞ¼b0þb1SOCIAL CAPITALþb2LNASSETSþb3DEBTþb4ROAþb5BIG4þb6LOSSþb7FISCAL YEAR ENDþb8DAYS TO SIGNþb9PUBLIC EXCHNGþb10UNQUALIFED OPINIONþb11GOING CONCERNþb12INHERENT RISKþb13LITIGATIONþb14AUDITOR CHANGEþb15SEGMENTSþb16COUNTY PRESENCEþb17LARGE SCALEþb18SPECIALISTþb19AUDITOR COMPETITIONþb20COST OF LIVINGþb21RELIGIOSITYþb22DIST FROM SECþb23RURALþb24INCOMEþb25POPGþb26LNPOPþb27LITERACYþIndustry IndicatorsþYear Indicatorsþe:ð1ÞThe variables are defined in detail in Appendix A.Our unit of analysis is afirm-year, where the subscript it is suppressed for expositional ease.Thefirm-level control variables are2We acknowledge that the county in which the auditor resides might also matter.We address this issue in additional analyses later in the paper.3Firms can change their headquarters over time,and this change could add noise to our method.Although this noise is possible,firms seem to rarely change their headquarters.For example,Pirinsky and Wang(2006)find only118 changes in headquarters in a sample of5,000firms spanning15years.Audit Fees and Social Capital615The Accounting Review March2015based on Hay,Knechel,and Wong (2006),who include controls for the size,complexity,inherent risk,profitability,leverage,auditor type,auditor report lag,and the busy season for audits.We expect audit fees to be higher for large,complex,and risky firms,when the firm is audited by the Big 4audit firms and when the audit is conducted in a busy season.Because Fung,Gul,and Krishnan (2012)find that the city-level industry specialization of the auditors and their economies of scale have an impact on audit fees,we also add a measure for the city-level industry specialization and economies of scale.We also control for the extent of the audit market competition in the county,as in Newton,Wang,and Wilkins (2013),and the number of clients’geographic segments.Although the key managers who influence financial reporting are located in the firm’s headquarters,the employees in other geographic locations also have an effect on the accounting information systems and the firm’s financial reports.We control for this effect by including the number of geographic segments in our model.And,consistent with Fung et al.(2012),we add industry indicator variables based on the two-digit SIC code,as well as year indicator variables,to control for the impact from changes in the financial reporting regulations.Because recent finance and accounting research shows that the religiosity in a county has a significant impact on the firm’s financial reporting quality (Grullon et al.2010;McGuire et al.2012),we control for religiosity at the county level.We control for other related county-level characteristics,including the cost of living in the county,the distance from the nearest regional Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)office,the population density,the county population,the population growth,the income per capita,and the literacy rate.We expect audit fees to be lower for firms that are located in religious counties because misconduct is expected to be lower in these counties.We also expect audit fees to be higher where the cost of living index is higher.The impact of the distance from the SEC is unclear.Firms further away from the SEC are likely to have more financial reporting irregularities,which results in higher audit fees.But firms further away from the SEC are also less prone to scrutiny by the SEC,reducing litigation risk and lowering audit fees.4To control for the possibility that the error terms might be correlated,we cluster the standard errors at the county level.Because we cluster at the county level,we automatically control for clustering at the firm level (Bertrand,Duflo,and Mullainathan 2004;Dinc 2005;Cameron and Miller 2011).5,6In our main regression,we do not control for corporate governance characteristics,such as the characteristics of the board and the relative power of management compared to the shareholders,because doing so would severely limit our sample size.However,we do control for them in our robustness tests,and our results continue to hold.Because our entire sample is from the U.S.,we automatically control for differences in legal origin,laws,and institutions.Measure of Social CapitalWe construct a social-capital index for each county following the steps in Rupasingha and Goetz (2008).They use two measures of norms and two measures of networks,and conduct a principal component analysis to construct an index for each county for the years 1997,2005,and 4Given that we have a large set of control variables,we check for multicollinearity by measuring the variance inflation factor (VIF).Because the VIFs of the explanatory variables are well below 10,and the average VIF of the explanatory variables is 2.42,multicollinearity does not appear to be a problem.5In our case,the firms are nested in the counties.Therefore,we have a nested level of clustering.In such a case,‘‘cluster-robust standard errors are computed at the most aggregate level of clustering ’’(Cameron and Miller 2011,7).6However,our main results continue to hold if we (1)cluster at the firm level,(2)adopt two-way clustering (firm and year or county and year)(Petersen 2009;Gow,Ormazabal,and Taylor 2010),or (3)use the Huber-White standard error without clustering.616Jha andChen The Accounting ReviewMarch 20152009.The social-capital index for each county and the underlying data used to construct the index are available at the Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development(NERCRD).7 As far as we know,the Rupasingha and Goetz(2008)approach to measuring social capital is the most comprehensive measure of social capital at the county level.Putnam(2007)uses their measure of social capital as an alternative measure for individual trust.Besides Putnam(2007), many authors in different disciplines have used Rupasingha and Goetz’s(2008)index or followed their approach,including S.Deller and M.Deller(2010)and Hopkins(2011).Following Rupasingha and Goetz(2008),the two measures of social norms we use are voter turnout in presidential elections and the census response rate.Higher values for these variables represent higher social capital.The literature has used both of these measures,either independently or as a component of a social-capital index.For example,Guiso et al.(2004)use participation in referenda in Italy as a measure of social capital,Alesina and La Ferrara(2000)use participation in a presidential election as a component in the construct of a social-capital index,and Knack(2002) uses the census response rate as a measure of social capital.The two measures of networks are the number of social and civic associations and the number of nongovernment organizations(NGO)in counties.Social and civic associations include physical fitness facilities,public golf courses,religious organizations,sports clubs,managers and promoters, political organizations,professional organizations,business associations,and labor organizations in the county,but we exclude NGOs with an international focus.Both of these measures are normalized by the population in the county.The literature also uses these two measures independently as measures of social capital(Knack2002;Hopkins2011).Because the measures of the norms and the network are highly correlated,8we follow Rupasingha and Goetz(2008)by conducting a principal component analysis to construct an index of social capital for each county for the years1997,2005,and2009.We extract thefirst component as a measure of the social capital.9We then linearly interpolate the data tofill in the years1998to2004 and2006to2008,10following the same approach as Hilary and Hui(2009)and many other studies.11 Appendix A provides a more detailed description of how we construct the social-capital measures.We present the variation in social capital at the county level in Figure1for the year2000.For brevity,we do not present thefigures for2005and2009because they are similar.The correlation between the2000and the2009social-capital index is0.91.This is consistent with the idea that unlike physical and human capital,social capital is‘‘sticky’’(Anheier and Gerhards1995).When constructing the social-capital index,we assume that all types of association memberships increase the general trust in the society.We acknowledge that not all researchers agree with this view.In the context of social capital,the common approach is to view associations as one of two types:those that act like‘‘bridges’’between groups,such as religious organizations, civic and social associations,bowling centers,physicalfitness facilities,public golf courses,and sports clubs;and those that strengthen the‘‘bonding’’between members within a group,such as 7The data is available upon request from Northeast Regional Center for Rural Development(NERCRD)at:http://aese./nercrd.8For example,the correlation between the voter turnout in the election and number of organizations in the county is0.30in2005.9The eigenvalues of thefirst component for1997,2005,and2009are2.06,1.94,and1.84,respectively.The eigenvalues of the other components are less than1except in2009,when the second component has an eigenvalue of1.03.To maintain consistency between the years,we use only thefirst component for each year and consider it thesocial-capital index.10The results continue to hold when we use Rupasingha and Goetz’s(2008)index and test for only those years for which their index is available.11The use of linear interpolation tofill in the missing values of the in-between years is a common practice in the prior literature(Kumar,Page,and Spalt2011;Alesina and La Ferrara2000).Audit Fees and Social Capital617The Accounting Review March2015。

马克思英文简介_英文简历模板

马克思英文简介卡尔·海因里希·马克思,马克思主义的创始人之一,被称为全世界无产阶级和劳动人民的伟大导师。