The Third Way- Beyond Shareholder or Board Primacy

AvailabilityCascadesandRiskRegulation

315. Lior J. Strahilevitz, Wealth without Markets? (November 2006)

Timur Kuran

Follow this and additional works at:/

public_law_and_legal_theory

Part of the Law Commons

This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Working Papers at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Law and Legal Theory Working Papers by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact

312. Dennis W. Carlton and Randal C. Picker, Antitrust and Regulation (October 2006)

313. Robert Cooter and Ariel Porat, Liability Externalities and Mandatory Choices: Should Doctors Pay Less? (November 2006)

University of Chicago Law School

简述马云的人生经历英语作文

简述马云的人生经历英语作文The Remarkable Journey of Jack Ma: Founder of Alibaba.Jack Ma, a name that has become synonymous with innovation and entrepreneurship in China, has carved out an extraordinary path in the world of business. Born in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, in 1964, Ma Yun, better known as Jack Ma, is the epitome of perseverance and vision. His life story is an inspiration to millions who dream of making it big in the cut-throat world of corporate America.Ma's early life was nothing short of ordinary. He attended a local university, Hangzhou Normal University, where he majored in English. After graduating, he taught English for five years at a local university, a far cry from the glitz and glamour of the corporate world. However, it was during this time that he cultivated a keen interest in technology and entrepreneurship.In 1995, when the internet was still in its nascentstage in China, Ma was exposed to it for the first time. This exposure marked a turning point in his life. Hequickly realized the potential of this new technology and its immense possibilities for business. In 1999, Ma along with his team of 18 founders, launched Alibaba, an e-commerce platform that has revolutionized the way business is done in China and beyond.The journey of Alibaba has been nothing short of meteoric. From its humble beginnings as a small e-commerce platform, it has grown to become a global conglomerate with diverse business interests spanning e-commerce, cloud computing, digital media, and entertainment, among others. Ma's vision and leadership have been the driving force behind this phenomenal growth.Ma's approach to business is unique. He believes in the power of collaboration and has always encouraged a culture of inclusivity and diversity at Alibaba. This philosophy has been instrumental in attracting talent from across the globe and has contributed significantly to the company's success.Despite his immense success, Ma remains unassuming and down-to-earth. He is often quoted as saying that he is just a "common man" who was lucky enough to have great opportunities. His humility and commitment to social causes have earned him widespread respect and admiration.Ma's impact on the Chinese economy and beyond cannot be overstated. His vision and leadership have not only transformed Alibaba into a global powerhouse but have also sparked a wave of entrepreneurship and innovation in China. His philosophy of "customer first, employee second, shareholder third" has become a mantra for businesses across the globe.In recent years, Ma has stepped back from the day-to-day operations of Alibaba to focus on philanthropy and education. He has been actively involved in promoting entrepreneurship and innovation, especially among the younger generation. His foundation, the Jack Ma Foundation, has been involved in various social causes, including education, healthcare, and environmental conservation.In conclusion, the life of Jack Ma is an inspiration to millions. His story is a testament to the power of perseverance, vision, and leadership. His impact on the Chinese economy and beyond is immeasurable, and his contributions to society are truly remarkable. As we look towards the future, it is certain that the influence of Jack Ma and his legacy will continue to inspire generations to come.。

文学几大主义

1. Naturalism 自然主义•American literary naturalism emerged in the 1890s as an outgrowth of American realism.•Naturalism is sometimes claimed to give an even more accurate depiction of life than realism.•It is more than that, for it is a mode of fiction that was developed by a school of writers in accordance witha particular philosophical thesis.Philosophical foundations 哲学基础This thesis is a product of post-Darwinian biology in the nineteenth century.1) a human being exists entirely in the order of nature and does not have a soul nor any mode of participating in a religious or spiritual world beyond the natural world.2) a human being is merely a higher-order animal whose character and behavior are entirely determined by two kinds of forces, heredity and environment.3) A person inherits compulsive instincts--especially hunger, the drive to accumulate possessions, and sexuality--and is then subject to the social and economic forces in the family, the class, and the milieu into which that person is born.•Briefly, Naturalist writers believed that a human being is no more than a higher-order animal, who is governed by heredity and environment, natural or socioeconomic, thus, acquirng no free will and living in an amoral world.•"the survival of the fittest", "the human beast"•Naturalistic works exposed the dark harshness of life, including poverty, racism, violence, prejudice, disease, corruption, prostitution, and filth. As a result, naturalistic writers were frequently criticized for focusing too much on human vice and misery.Naturalist WritersStephen CraneFrank NorrisTheodore DreiserEdwin Arlington RobinsonJack LondonO’ HenryStephen Crane (1871-1900)•Maggie: A Girl of the Streets (1893)•The Red Badge of Courage (1895)•"The Open Boat"•"The Monster"•"The Brides Comes to Yellow Sky"•"The Blue Hotel"poems:•The Black Riders and Other Lines《黑衣骑士及其他》•War is Kind《战争是仁慈的》•Stephen Crane and Emily Dickinson are now recognized as the two presursors of Imagist poetry.2. TRANSCENDENTALISM (Transcendentalism超验主义)◆When did Transcendentalism come into being?◆Who were the spokesmen of Transcendentalism?◆What is Transcendentalism?◆Where did Transcendentalism originate?WHEN:◆In 1836 an informal group, the Transcendentalist Club, met in Concord, Massachusetts, to discusstheology, philosophy, and literature.◆Between 1840 and 1844, the Club published sixteen issues of The Dial, a quarterly. They established in1841 Brook Farm, a utopian community in which individuals were suppoesd to be better enabled towards self-realization. The experiment ended in failure in 1847.WHO:◆William Ellery Channing◆Ralph Waldo Emerson◆Henry David Thoreau◆Bronson Alcott◆Margaret Fuller◆Nathaniel HarthorneWHAT:◆Centered in Concord and Boston from 1836 till just before the Civil War, Transcendentalism is a NewEngland literary movement which held that spiritual realtiy, discernible through intution, transcended empirical or scientific knowledge.◆There are three major features of New England Transcendentalism being summarized as follows:◆Firstly, the Transcendentalists placed emphasis on spirit, or the Oversoul(超灵), as the most importantthing in the universe.◆Secondly, the Transcendentalists stressed the importance of the individual.◆Thirdly, the Transcendentalists offered a fresh perception of nature as symbolic of the Spirit or God.◆The Oversoul was an all-pervading power for goodness, omnipresent and omnipotent, from which allthings came and of which all were a part.◆It existed in nature and man alike and constituted the chief element of the universe.◆It was a reaction to the eighteenth-century Newtonian concept of the universe.◆It was also a reaction against the direction that a mechanized, capitalist America was taking.◆As the regeneration of society could only come about through the regeneration of the individual, hisperfection, his self-culture and self-improvement, and not the frenzed effort to get rich, should become the first concern of his life.◆The ideal type of man was the self-reliant individual.◆The individual soul communed with the Oversoul and was therefore divine.◆This new notion of the individual and his importance represented a new way of looking at man.◆It was a reaction against the Calvinist concept that man is totally depraved, he is sinful and perseveres insinhood, and can not hope to be saved except through the grace of God.◆It was also a reaction against the process of dehumanization that came in the wake of developingcapitalism.◆Nature was, to the Transcendentalists, not purely matter. It was alive, filled with God's overwhelmingpresence. It was the garment of the Oversoul.◆Nature could exercise a healthy and restorative influences on the human mind.◆Things in nature tended to become symbolic, and the physical world was a symbol of the spiritual."Go back to nature, sink yourself back into its influence, and you'll become spiritually whole again." WHERE:◆New England Transcendentalism was the product of a combination of foreign influences and theAmerican Puritan tradition. It was, in actuality, Romanticism on the Puritan soil. It could be called Romantic idealism.◆ First, neo-Platonism , the belief that spirit prevails over matter and there is an ascending scale of spiritualvalues rising to absolute Good.◆ Second, German Romanticism as transmitted through the writings of Coleridge and Carlyle, whichemphasized intuition as a means of piercing to the real essence of things.◆ Third, an Oriental mysticism as embodied in such Hindu works as Upanishads (《奥义书》)andBhagavad-Gita (《薄伽梵歌》), and to the doctrine and philosophy of the Chinese Confucius and Mencius. ◆ Fourth, Puritan principle of self-culture and self-improvement.3. Impressionism 印象主义• Impressionism is a 19th-century art movement that originated with a group of Paris-based artists. Theirindependent exhibitions brought them to prominence during the 1870s and 1880s, in spite of harsh opposition from the conventional art community in France.• The name of the style derives from the title of a Claude Monet work, Impression, soleil levant (Impression,Sunrise), which provoked the critic Louis Leroy to coin the term in a satirical review published in the4. Local Color 乡土特色◆ The detailed representation in prose fiction of the setting, dialect, customs, dress, and ways of thinking andfeeling which are distinctive of a particular region. --M.A.Abrams in the late 1860s and early seventies The distinction between regionalism and local colorism:◆ A regional work relies on the cultural, social and historical settings of a region. If the setting is removed,the work is destroyed.◆ Local color writings are just as dependent upon a specific geographical location, but theygive moreemphasis to the local details by tapping into its folklore, history, mannerism(特殊习惯), customs, beliefs and speech. Dailect peculiarities are the defining characteristic of local color writings.Character analysis 主要人物Carrie Meeber or Sister Carrie 嘉莉妹妹•Carrie Meeber: the protagonist of the novel, an ordinary girl who rises from a low-paid, arduous position in a factory to a famous, high-paid actress in New York city.•She is driven by desire and catches blindly at any opportunity for a better exsitence, first offered by Drouet and then by Hursthood. She is totally at the mercy of forces that she cannot understand. She is a slave to her heredity and environment.•Strong determination to have a better life•Her goals are clothes, money and fame, and the means by which she achieves them are relatively unimportant.•Rise by the means of a male stepladder• A seeker, not satisfied, always has a new world to conquer, new goals to achieve.•“a naive, dreaming girl from the country, driven this way and that by the promptings of biology and economy, and pursued on her course by the passions of her rival lovers.”•“Her desire is illimitable, but her imagination is limited to the worlds o f goods. Carrie is always looking to see what else in the world she could want, and as Dreiser shows, she is conditioned biologically and culturally to want and buy what she sees.”Timid•“To avoid a certain indefinable shame she felt at being caught spying about for a position, she quickened her steps and assumed an air of indifference supposedly common to one upon an errand.”“为了避免在找工作中的那种莫名其妙的害羞,她加快了步子,装出一副不在乎的样子,她像是要办什么事似的。

商务英语阅读(第二版) 王关富 Unit8 The decade of Steve 课后答案

Unit 8The decade of SteveExercises1.Answer the questions on the text.1)What makes the story of Steve Jobs so incredible and remarkable?So perseverant in his goals;Experiencing and overcoming so many difficulties and frustrations;Dominating in as many as four distinct industries;Running Apple so well------creatively, competitively, and profitably;Miraculously returning from his fatal diseases.2)What are the four markets that Steve Jobs reorganized and dominated?Music, movies, mobile telephones as well as computing.3)Why is he regarded as the rare businessman?Predilections unique to him.Distinctive design taste and elegant retail stores.Outside-the box approach to advertisingA showman, born salesman, and a magician.Legitimate worldwide celebrityAlways making products customers want to buy.Visionary but grounded in reality.Motivated not by money, but by a visceral ardor for Apple.4)What astounding achievements has Steve Jobs made up to date?Increasing corporate worth from $5 billion in 2000 to $170 billion now.Moving from cash drain and near bankruptcy to $34 billion in cash and market securities.275 retail stores in 9 countries with 73% share of US MP3 player market, and undisputed leadership in mobile phone innovation.His personal net worth about $5 billion.5)What was the first important success of Steve’s team?It created the first Macintosh (iMac), a breakthrough all-in-one computer and monitor. With drastic cost cutting and lucrative sales, it greatly improved the Apple’s balance sheet and financially got Apple well prepared for big investments and business leap.6)Why did Steve object to Ellison buy out Apple in 1997?Because he didn’t like people to second-guess the intention of his return (as making money) and wanted to take high moral ground so that he could easy and graceful decisions.7)Why did Steve build Apple-owned retail stores and some have doubts?Because through the building of retail stores, Steve could establish direct contact with customers, get to know what they really want, and fill the stores with allthose products.But some people at the time, even members of the board had great doubts about establishing retail stores. They are extremely nervous that the stores might become a risky cash drain.8)What are the outstanding qualities reflected from Jobs’integration ofmicromanagement with big-picture vision?# Micro-management:Consciousness/ dedication/ concentrationHe tries to know everything about Apple. He is involved in so many details that people can hardly believe. He is so detailed that he might tell an ad writer that the third word in the fourth paragraph wasn’t right.# Big-picture vision:Acumen for market changeHe recognized gorgeous design as differentiator for Apple.Creative, innovative and visionary in product developmentClients responded “Give me the next Steve Jobs”Knack for taking opportunities at the right momentHe made iTunes compatible with Windows and expanded Apple market to all PCs.He developed Apple’s own digital-music sales stores.9)How did Steve Jobs master the message?Carefully consider what he and Apple say and don’t say to the public.Rehearse time and again before speaking publicly.Authorize only a small number of executives to speak publicly.He is careful to avoid overexposure.Nobody is supposed to speak without the permission of Apple’s media relations team reporting directly Steve Jobs.10) How did Steve Jobs handle Apple’s stock options backdating scandal?He remained silent initially but later in the report to SEC he admitted and apologized for the change of option grant dates for employee benefits. He said it was totally inappropriate for Apple to do.11) Whom did Steve Jobs thank and why when he returned?He thanked Tim Cook (Apple’s chief operating officer) for excellent running of the company during his absence.He also thanked a twentysomething who died in a car crash for donating his liver.12) How do people feel about the future of Apple?Though some are worried about its future due to Steve’s health problem, most are confident about its future because:He is a fabulous brand and irreplaceable person.He has educated and influenced Apple employees well enough to think and behave like him.His influence has gone beyond Apple and become a hero for the IT industry.His pursuit for secrecy and surprise and proven brilliance will ensure greater successes for Apple in the future.2.Fill in each blank of the following sentences with one of the phrases in the listgiven below. Make changes when necessary.1)When the starlet was asked about her new boyfriend, she couldn’t help but gushabout him and their intimate plans for Valentine’s Day.2)The leaking of as many as 251,000 State Department documents, including secretembassy reports from around the world, is nothing short of a political meltdown for US foreign policy.3)With very critical views on the government economic policies, she often palsaround with those scholars who also take rather radical stance on economic issues.4)It is high time for everyone in the department to kick into full gear and fulfill oursales quota by the end of the year.5)The mother did whatever possible to prevent her son from hanging out with theguy who she thought was up to nothing good.6)Obama’s victory in the election was viewed by many as progress in the UnitedStates. But I think his ethnicity is beside the point.7)The neighbors said what happened was totally out of character for the womanthey knew as quiet and friendly.8)Unfortunately, the firm has not been able to pare) production cost to the level thatmatches its competitors in the market.9)On the back of strong corporate earnings reports from a number of firms last week,coupled with the improving unemployment rate, investor sentiment was bolstered on the first trading day of the week.10)The team is expected to take a vote tonight that could set in motion a new plan torevitalize the financial market.11)It was a long time before our business partners could catch on to what we reallyintended.12)As a shrewd man, he successfully pounced at the opportunity last year to becomethe marketing manager.3.Match the terms in column A with the definitions in column B:A______________________ B________________________________________ 1)market share A) A group of advisors, originally to a political candidate,for their expertise in particular fields, but now to anydecision makers, whether or not in politics. 62)cash drain B) The rate of new product development, which isgetting faster with more severe competition andfaster technological advancement. 103)shareholder wealth C) Percentage or proportion of the total availablemarket or market segment that a product orcompany takes. 14)net worth D) A group of executives employed to manage aproject, department, or company with theirparticular expertise or skills. 55)management team E) A person, project, business or company thatcontinues to consume large amounts of cash withno end in sight. 26)brain trust F) A person or firm that invests in a businessventure, providing capital for start-up orexpansion, and expecting a higher rate of returnthan that for traditional investments. 97)balance sheet G) The wealth shareholders get to accrue from theirownership of shares in a firm, which can beincreased by raising either share prices ordividend payments. 38)captains of industry H) A financial statement that summarizes acompany's assets, liabilities and shareholders'equity at a specific point in time. 79)Venture capitalist I) Total assets minus total liabilities, an importantdeterminant of the value of a company, primarilycomposed of all the money that has been investedand the retained earnings for the duration of itsoperation. 410)product cycle L) A business leader who is especially successfuland powerful and whose means of amassing apersonal fortune contributes substantially to thecountry in some way. 84.Translate the following passage into Chinese:头已秃顶,留着胡须的他坐在其超大的华盛顿办公室内谈论着经济话题,从眼神可看出显得疲劳。

中国公司法 英文

中国公司法英文As a constantly evolving legal system, China's company law has undergone significant changes over the past few decades. With the rapid growth of China's economy and the increasing number of foreign investors, the Chinese government has been revising and refining its company law to strengthen corporate governance and protect the rights and interests of all stakeholders. In this article, we will provide a step-by-step overview of China's company law.Step 1: Types of CompaniesThe first step is to understand the different types of companies that exist in China. There are several types of companies, including:- Limited Liability Company (LLC)- Joint-stock Company (JSC)- Cooperative Company (CC)- Sole Proprietorship Enterprise (SPE)LLC and JSC are the two most common types of companies. An LLC is a company where the shareholders' liability is limited to their contribution to the registered capital. A JSC is a company where the shareholders' liability is limited to the par value of their shares.Step 2: Company RegistrationThe second step is to understand the companyregistration process. The process involves several steps, including:- Choosing a company name- Applying for a business license- Registering with the relevant authorities- Obtaining a tax registration certificate- Opening a bank accountThe application for a business license is the most important step in the registration process. The application should include information about the company's name,registered capital, business scope, and corporate structure.Step 3: Corporate GovernanceThe third step is to understand corporate governance in China. Corporate governance refers to the systems, structures, and processes by which a company is directed and managed. In China, corporate governance is regulated by different lawsand regulations, including the Company Law, Securities Law, and Corporate Governance Guidelines.Corporate governance in China is based on the principleof shareholder supremacy. However, the role of the board of directors and management is also important. Under Chinese law, the board of directors is responsible for overseeing the management of the company and protecting the interests of shareholders.Step 4: Rights and Obligations of ShareholdersThe fourth step is to understand the rights and obligations of shareholders. Shareholders have the right to participate in the company's management, share in the profits, and receive dividends. They are also entitled to inspect the company's financial statements and attend general meetings.Shareholders also have obligations, including the obligation to pay their capital contributions, the obligation to comply with the company's articles of association and relevant laws and regulations, and the obligation to informthe company of any changes to their personal information.Step 5: Amendments and TerminationThe final step is to understand how to make amendments to the company's articles of association and how to terminate the company. Amendments to the articles of association can be made by the shareholders' meeting or the board of directors. Termination of the company can be initiated by the shareholders or by the relevant authorities.In conclusion, China's company law is a complex andever-changing system that requires careful attention todetail and compliance with relevant regulations. By understanding the different types of companies, the registration process, corporate governance, shareholders' rights and obligations, and amendments and termination, investors can navigate the legal landscape and build successful companies in China.。

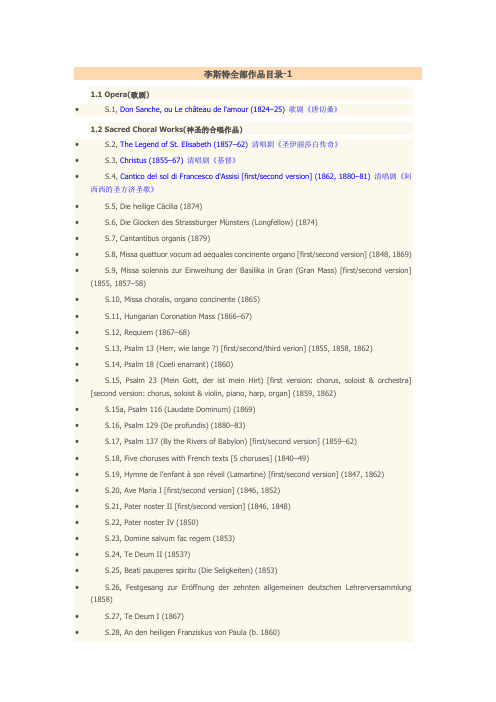

李斯特的作品列表

1.1 Opera(歌剧)•S.1, Don Sanche, ou Le château de l'amour (1824–25) 歌剧《唐切桑》1.2 Sacred Choral Works(神圣的合唱作品)•S.2, The Legend of St. Elisabeth (1857–62) 清唱剧《圣伊丽莎白传奇》•S.3, Christus (1855–67) 清唱剧《基督》•S.4, Cantico del sol di Francesco d'Assisi [first/second version] (1862, 1880–81) 清唱剧《阿西西的圣方济圣歌》•S.5, Die heilige Cäcilia (1874)•S.6, Die Glocken des Strassburger Münsters (Longfellow) (1874)•S.7, Cantantibus organis (1879)•S.8, Missa quattuor vocum ad aequales concinente organo [first/second version] (1848, 1869)•S.9, Missa solennis zur Einweihung der Basilika in Gran (Gran Mass) [first/second version] (1855, 1857–58)•S.10, Missa choralis, organo concinente (1865)•S.11, Hungarian Coronation Mass (1866–67)•S.12, Requiem (1867–68)•S.13, Psalm 13 (Herr, wie lange ?) [first/second/third verion] (1855, 1858, 1862)•S.14, Psalm 18 (Coeli enarrant) (1860)•S.15, Psalm 23 (Mein Gott, der ist mein Hirt) [first version: chorus, soloist & orchestra] [second version: chorus, soloist & violin, piano, harp, organ] (1859, 1862)•S.15a, Psalm 116 (Laudate Dominum) (1869)•S.16, Psalm 129 (De profundis) (1880–83)•S.17, Psalm 137 (By the Rivers of Babylon) [first/second version] (1859–62)•S.18, Five choruses with French texts [5 choruses] (1840–49)•S.19, Hymne de l'enfant à son réveil (Lamartine) [first/second version] (1847, 1862)•S.20, Ave Maria I [first/second version] (1846, 1852)•S.21, Pater noster II [first/second version] (1846, 1848)•S.22, Pater noster IV (1850)•S.23, Domine salvum fac regem (1853)•S.24, Te Deum II (1853?)•S.25, Beati pauperes spiritu (Die Seligkeiten) (1853)•S.26, Festgesang zur Eröffnung der zehnten allgemeinen deutschen Lehrerversammlung (1858)•S.27, Te Deum I (1867)•S.28, An den heiligen Franziskus von Paula (b. 1860)•S.29, Pater noster I (b. 1860)•S.30, Responsorien und Antiphonen [5 sets] (1860)•S.31, Christus ist geboren I [first/second version] (1863?)•S.32, Christus ist geboren II [first/second version] (1863?)•S.33, Slavimo Slavno Slaveni! [first/second version] (1863, 1866)•S.34, Ave maris stella [first/second version] (1865–66, 1868)•S.35, Crux! (Guichon de Grandpont) (1865)•S.36, Dall' alma Roma (1866)•S.37, Mihi autem adhaerere (from Psalm 73) (1868)•S.38, Ave Maria II (1869)•S.39, Inno a Maria Vergine (1869)•S.40, O salutaris hostia I (1869?)•S.41, Pater noster III [first/second version] (1869)•S.42, Tantum ergo [first/second version] (1869)•S.43, O salutaris hostia II (1870?)•S.44, Ave verum corpus (1871)•S.45, Libera me (1871)•S.46, Anima Christi sanctifica me [first/second version] (1874, ca. 1874)•S.47, St Christopher. Legend (1881)•S.48, Der Herr bewahret die Seelen seiner Heiligen (1875)•S.49, Weihnachtslied (O heilige Nacht) (a. 1876)•S.50, 12 Alte deutsche geistliche Weisen (Chorales) [12 chorals] (ca. 1878-79) •S.51, Gott sei uns gnädig und barmherzig (1878)•S.52, Septem Sacramenta. Responsoria com organo vel harmonio concinente (1878) •S.53, Via Crucis (1878–79)•S.54, O Roma nobilis (1879)•S.55, Ossa arida (1879)•S.56, Rosario [4 chorals] (1879)•S.57, In domum Domino imibus (1884?)•S.58, O sacrum convivium (1884?)•S.59, Pro Papa (ca. 1880)•S.60, Zur Trauung. Geistliche Vermählungsmusik (Ave Maria III) (1883)•S.61, Nun danket alle Gott (1883)•S.62, Mariengarten (b. 1884)•S.63, Qui seminant in lacrimis (1884)•S.64, Pax vobiscum! (1885)•S.65, Qui Mariam absolvisti (1885)•S.66, Salve Regina (1885)• 1.3 Secular Choral Works(世俗的合唱作品)•S.67, Beethoven Cantata No. 1: Festkantate zur Enthüllung (1845)•S.68, Beethoven Cantata No. 2: Zur Säkularfeier Beethovens (1869–70)•S.69, Chöre zu Herders Entfesseltem Prometheus (1850)•S.70, An die Künstler (Schiller) [first/second/third verion] (1853, 1853, 1856)•S.71, Gaudeamus igitur. Humoreske (1869)•S.72, Vierstimmige Männergesänge [4 chorals] (for Mozart-Stiftung) (1841)•S.73, Es war einmal ein König (1845)•S.74, Das deutsche Vaterland (1839)•S.75, Über allen Gipfeln ist Ruh (Goethe) [first/second version] (1842, 1849)•S.76, Das düstre Meer umrauscht mich (1842)•S.77, Die lustige Legion (A. Buchheim) (1846)•S.78, Trinkspruch (1843)•S.79, Titan (Schobert) (1842–47)•S.80, Les quatre éléments (Autran) (1845)•S.81, Le forgeron (de Lamennais) (1845)•S.82, Arbeiterchor (de Lamennais?) (1848)•S.83, Ungaria-Kantate (Hungaria 1848 Cantata) (1848)•S.84, Licht, mehr Licht (1849)•S.85, Chorus of Angels from Goethe's Faust (1849)•S.86, Festchor zur Enthüllung des Herder-Dankmals in Weimar (A. Schöll) (1850)•S.87, Weimars Volkslied (Cornelius) [6 versions] (1857)•S.88, Morgenlied (Hoffmann von Fallersleben) (1859)•S.89, Mit klingendem Spiel (1859–62 ?)•S.90, Für Männergesang [12 chorals] (1842–60)•S.91, Das Lied der Begeisterung. A lelkesedes dala (1871)•S.92, Carl August weilt mit uns. Festgesang zur Enthüllung des Carl-August-Denkmals in Weimar am 3 September 1875 (1875)•S.93, Ungarisches Königslied. Magyar Király-dal (Ábrányi) [6 version] (1883)•S.94, Gruss (1885?)1.4 Orchestral Works(管弦乐作品)1.4.1 Symphonic Poems(交响诗)•S.95, Poème symphonique No. 1, Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne (Berg Symphonie) [first/second/third version] (1848–49, 1850, 1854) 第一交响诗山间所闻•S.96, Poème symphonique No. 2, Tasso, Lamento e Trionfo [first/second/third version] (1849, 1850–51, 1854) 《塔索,哀叹与胜利》•S.97, Poème symphonique No. 3, Les Préludes (1848) 第三交响诗“前奏曲”•S.98, Poème symphonique No. 4, Orpheus (1853–54) 第四交响诗《奥菲欧》•S.99, Poème symphonique No. 5, Prometheus [first/second version] (1850, 1855) 第五交响诗《普罗米修斯》•S.100, Poème symphonique No. 6, Mazeppa [first/second version] (1851, b. 1854) 第六交响诗《马捷帕》•S.101, Poème symphonique No. 7, Festklänge [revisions added to 1863 pub] (1853) 第七交响诗《节日之声》•S.102, Poème symphonique No. 8, Héroïde funèbre [first/second version] (1849–50, 1854) 第八交响诗《英雄的葬礼》•S.103, Poème symphonique No. 9, Hungaria (1854) 第九交响诗《匈牙利》•S.104, Poème symphonique No. 10, Hamlet (1858) 第十交响《哈姆雷特》•S.105, Poème symphonique No. 11, Hunnenschlacht (1856–57) 第十一交响诗《匈奴之战》•S.106, Poème symphonique No. 12, Die Ideale (1857) 第十二交响诗《理想》•S.107, Poème symphonique No. 13, Von der Wiege bis zum Grabe (From the Cradle to the Grave) (1881–82) 第十三交响诗《从摇篮到坟墓》1.4.2 Other Orchestral Works(其他管弦乐作品)•S.108, Eine Faust-Symphonie [first/second version] (1854, 1861)•S.109, Eine Symphonie zu Dante's Divina Commedia (1855–56)•S.110, Deux épisodes d'apres le Faust de Lenau [2 pieces] (1859–61)•S.111, Zweite Mephisto Waltz (1881)•S.112, Trois Odes Funèbres [3 pieces] (1860–66)•S.113, Salve Polonia (1863)•S.114, Künstlerfestzug zur Schillerfeier (1857)•S.115, Festmarsch zur Goethejubiläumsfeier [first/second version] (1849, 1857)•S.116, Festmarsch nach Motiven von E.H.z.S.-C.-G. (1857)•S.117, Rákóczy March (1865)•S.118, Ungarischer Marsch zur Krönungsfeier in Ofen-Pest (am 8 Juni 1867) (1870)•S.119, Ungarischer Sturmmarsch (1875)1.5 Piano and Orchestra(钢琴与乐队)•S.120, Grande Fantaisie Symphonique on themes from Berlioz Lélio (1834)•S.121, Malédiction (with string orchestra) (1833) 诅咒钢琴与弦乐队•S.122, Fantasie über Beethovens Ruinen von Athen [first/second version] (1837?, 1849) •S.123, Fantasie über ungarische Volksmelodien (1852) 匈牙利民歌主题幻想曲为钢琴与乐队而作•S.124, Piano Concerto No. 1 in E flat [first/second version] (1849, 1856) 降E大调第一钢琴协奏曲•S.125, Piano Concerto No. 2 in A major [first/second version] (1839, 1849) A大调第二钢琴协奏曲•S.125a, Piano Concerto No. 3 in E flat (1836–39)•S.126, Totentanz. Paraphrase on Dies Irae [Feruccio Busoni's 'De Profundis'/final version] (1849, 1859) 死之舞为钢琴与乐队而作•S.126a, Piano Concerto "In the Hungarian Style" [probably by Sophie Menter] (1885)1.6 Chamber Music(室内乐等)S.126b, Zwei Waltzer [2 pieces] (1832)•S.127, Duo (Sonata) - Sur des thèmes polonais (1832-35 ?)•S.128, Grand duo concertant sur la romance de font Le Marin [first/second version] (ca.1835-37, 1849)•S.129, Epithalam zu Eduard. Reményis Vermählungsfeier (1872)•S.130, Élégie No. 1 [first/second/third version] (1874)•S.131, Élégie No. 2 (1877)•S.132, Romance oubliée (1880)•S.133, Die Wiege (1881?)•S.134, La lugubre gondola [first/second version] (1883?, 1885?)•S.135, Am Grabe Richard Wagners (1883)1.7 Piano Solo1.7.1 Studies(钢琴练习曲)•S.136, Études en douze exercices dans tous les tons majeurs et mineurs [first version, 12 pieces] (1826) 12首钢琴练习曲•S.137, Douze grandes études [second version, 12 pieces] (1837) 《12首超技练习曲》•S.138, Mazeppa [intermediate version of S137/4] (1840) 练习曲“玛捷帕”•S.139, Douze études d'exécution transcendante [final version, 12 pieces] (1852) 12首超技练习曲•S.140, Études d'exécution transcendante d'après Paganini [first version, 6 pieces] (1838) 帕格尼尼超技练习曲•S.141, Grandes études de Paganini [second version, 6 pieces] (1851) 6首帕格尼尼大练习曲•S.142, Morceau de salon, Étude de perfectionnement [Ab Irato, first version] (1840) 高级练习曲“沙龙小品”•S.143, Ab Irato, Étude de perfectionnement [second version] (1852) 高级练习曲“愤怒”•S.144, Trois études de concert [3 pieces] (1848?) 3首音乐会练习曲1. Il lamento2. La leggierezza3. Un sospiro•S.145, Zwei Konzertetüden [2 pieces] (1862–63) 2首音乐会练习曲1. Waldesrauschen2. Gnomenreigen•S.146, Technische Studien [68 studies] (ca. 1868-80) 钢琴技巧练习1.7.2 Various Original Works(各种原创作品)•S.147, Variation on a Waltz by Diabelli (1822) 狄亚贝利圆舞曲主题变奏曲•S.148, Huit variations (1824?) 降A大调原创主题变奏曲•S.149, Sept variations brillantes dur un thème de G. Rossini (1824?)•S.150, Impromptu brilliant sur des thèmes de Rossini et Spontini (1824) 罗西尼与斯蓬蒂尼主题即兴曲•S.151, Allegro di bravura (1824) 华丽的快板•S.152, Rondo di bravura (1824) 华丽回旋曲•S.152a, Klavierstück (?)•S.153, Scherzo in G minor (1827) g小调谐谑曲•S.153a, Marche funèbre (1827)•S.153b, Grand solo caractèristique d'apropos une chansonette de Panseron [private collection, score inaccessible] (1830–32) [1]•S.154, Harmonies poétiques et religieuses [Pensée des morts, first version] (1833, 1835) 宗教诗情曲•S.155, Apparitions [3 pieces] (1834) 显现三首钢琴小品•S.156, Album d'un voyageur [3 sets; 7, 9, 3 pieces] (1835–38) 旅行者札记•S.156a, Trois morceaux suisses [3 pieces] (1835–36)•S.157, Fantaisie romantique sur deux mélodies suisses (1836) 浪漫幻想曲•S.157a, Sposalizio (1838–39)•S.157b, Il penseroso [first version] (1839)•S.157c, Canzonetta del Salvator Rosa [first version] (1849)•S.158, Tre sonetti del Petrarca [3 pieces, first versions of S161/4-6] (1844–45) 3首彼特拉克十四行诗•S.158a, Paralipomènes à la Divina Commedia [Dante Sonata original 2 movement version] (1844–45)•S.158b, Prologomènes à la Divina Commedia [Dante Sonata second version] (1844–45)•S.158c, Adagio in C major (Dante Sonata albumleaf) (1844–45)•S.159, Venezia e Napoli [first version, 4 pieces] (1840?) 威尼斯和拿波里•S.160, Années de pèlerinage. Première année; Suisse [9 pieces] (1848–55) 旅行岁月(第一集)- 瑞士游记•S.161, Années de pèlerinage. Deuxième année; Italie [7 pieces] (1839–49) 旅行岁月(第二集)- 意大利游记•S.162, Venezia e Napoli. Supplément aux Années de pèlerinage 2de volume [3 pieces] (1860) 旅行岁月(第二集补遗)- 威尼斯和拿波里•S.162a, Den Schutz-Engeln (Angelus! Prière à l'ange gardien) [4 drafts] (1877–82) •S.162b, Den Cypressen der Villa d'Este - Thrénodie II [first draft] (1882)•S.162c, Sunt lacrymae rerum [first version] (1872)•S.162d, Sunt lacrymae rerum [intermediate version] (1877)•S.162e, En mémoire de Maximilian I [Marche funèbre first version] (1867)•S.162f, Postludium - Nachspiel - Sursum corda! [first version] (1877)•S.163, Années de pèlerinage. Troisième année [7 pieces] (1867–77) 旅行岁月(第三集)•S.163a, Album-Leaf: Andantino pour Emile et Charlotte Loudon (1828) [2] 降E大调纪念册的一页•S.163a/1, Album Leaf in F sharp minor (1828)降E大调纪念册的一页•S.163b, Album-Leaf (Ah vous dirai-je, maman) (1833)•S.163c, Album-Leaf in C minor (Pressburg) (1839)•S.163d, Album-Leaf in E major (Leipzig) (1840)•S.164, Feuille d'album No. 1 (1840) E大调纪念册的一页•S.164a, Album Leaf in E major (Vienna) (1840)•S.164b, Album Leaf in E flat (Leipzig) (1840)•S.164c, Album-Leaf: Exeter Preludio (1841)•S.164d, Album-Leaf in E major (Detmold) (1840)•S.164e, Album-Leaf: Magyar (1841)•S.164f, Album-Leaf in A minor (Rákóczi-Marsch) (1841)•S.164g, Album-Leaf: Berlin Preludio (1842)•S.165, Feuille d'album (in A flat) (1841) 降A大调纪念册的一页•S.166, Albumblatt in waltz form (1841) A大调圆舞曲风格纪念册的一页•S.166a, Album Leaf in E major (1843)•S.166b, Album-Leaf in A flat (Portugal) (1844)•S.166c, Album-Leaf in A flat (1844)•S.166d, Album-Leaf: Lyon prélude (1844)•S.166e, Album-Leaf: Prélude omnitonique (1844)•S.166f, Album-Leaf: Braunschweig preludio (1844)•S.166g, Album-Leaf: Serenade (1840–49)•S.166h, Album-Leaf: Andante religioso (1846)•S.166k, Album Leaf in A major: Friska (ca. 1846-49)•S.166m-n, Albumblätter für Prinzessin Marie von Sayn-Wittgenstein (1847)•S.167, Feuille d'album No. 2 [Die Zelle in Nonnenwerth, third version] (1843) a小调纪念册的一页•S.167a, Ruhig [catalogue error; see Strauss/Tausig introduction and coda]•S.167b, Miniatur Lieder [score not accessible at present] (?)•S.167c, Album-Leaf (from the Agnus Dei of the Missa Solennis, S9) (1860–69)•S.167d, Album-Leaf (from the symphonic poem Orpheus, S98) (1860)•S.167e, Album-Leaf (from the symphonic poem Die Ideale, S106) (1861)•S.167f, Album Leaf in G major (ca. 1860)•S.168, Elégie sur des motifs du Prince Louis Ferdinand de Prusse [first/second version] (1842, 1851) 悲歌•S.168a, Andante amoroso (1847?)•S.169, Romance (O pourquoi donc) (1848) e小调浪漫曲•S.170, Ballade No. 1 in D flat (Le chant du croisé) (1845–48) 叙事曲一•S.170a, Ballade No. 2 [first draft] (1853)•S.171, Ballade No. 2 in B minor (1853) 叙事曲二•S.171a, Madrigal (Consolations) [first series, 6 pieces] (1844)•S.171b, Album Leaf or Consolation No. 1 (1870–79)•S.171c, Prière de l'enfant à son reveil [first version] (1840)•S.171d, Préludes et harmonies poétiques et religie (1845)•S.171e, Litanies de Marie [first version] (1846–47)•S.172, Consolations (Six penseés poétiques) (1849–50) 6首安慰曲•S.172a, Harmonies poétiques et religieuses [1847 cycle] (1847)•S.172a/3&4, Hymne du matin, Hymne de la nuit [formerly S173a] (1847)•S.173, Harmonies poétiques et religieuses [second version] (1845–52) 诗与宗教的和谐•S.174, Berceuse [first/second version] (1854, 1862) 摇篮曲•S.175, Deux légendes [2 pieces] (1862–63) 2首传奇•1. St. François d'Assise. La prédication aux oiseaux (Preaching to the Birds)•2. St. François de Paule marchant sur les flots (Walking on the Waves)•S.175a, Grand solo de concert [Grosses Konzertsolo, first version] (1850)•S.176, Grosses Konzertsolo [second version] (1849–50 ?) 独奏大协奏曲•S.177, Scherzo and March (1851) 谐谑曲与进行曲•S.178, Piano Sonata in B minor (1852–53) b小调钢琴奏鸣曲•S.179, Prelude after a theme from Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen by J. S. Bach (1859) 前奏曲“哭泣、哀悼、忧虑、恐惧”S.179 - 根据巴赫第12康塔塔主题而作•S.180, Variations on a theme from Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen by J. S. Bach (1862) 巴赫康塔塔主题变奏曲•S.181, Sarabande and Chaconne from Handel's opera Almira (1881)•S.182, Ave Maria - Die Glocken von Rom (1862) 圣母颂“罗马的钟声”•S.183, Alleluia et Ave Maria [2 pieces] (1862) 哈利路亚与圣母颂•S.184, Urbi et orbi. Bénédiction papale (1864)•S.185, Vexilla regis prodeunt (1864)•S.185a, Weihnachtsbaum [first version, 12 pieces] (1876)•S.186, Weihnachtsbaum [second version, 12 pieces] (1875–76) 钢琴曲集《圣诞树》•S.187, Sancta Dorothea (1877) 圣多萝西娅•S.187a, Resignazione [first/second version] (1877)•S.188, In festo transfigurationis Domini nostri Jesu Christi (1880) 我主耶稣基督之变形•S.189, Klavierstück No. 1 (1866)•S.189a, Klavierstück No. 2 (1845)•S.189b, Klavierstück (?)•S.190, Un portrait en musique de la Marquise de Blocqueville (1868)•S.191, Impromptu (1872) 升F大调即兴曲“夜曲”•S.192, Fünf Klavierstücke (for Baroness von Meyendorff) [5 pieces] (1865–79) 5首钢琴小品•S.193, Klavierstuck (in F sharp major) (a. 1860) 升F大调钢琴小品•S.194, Mosonyis Grabgeleit (Mosonyi gyázmenete) (1870) 在莫佐尼墓前•S.195, Dem andenken Petofis (Petofi Szellemenek) (1877) 纪念裴多菲•S.195a, Schlummerlied im Grabe [Elegie No 1, first version] (1874)•S.196, Élégie No. 1 (1874)•S.196a, Entwurf der Ramann-Elegie [Elegie No 2, first draft] (1877)•S.197, Élégie No. 2 (1877)•S.197a, Toccata (1879–81) 托卡塔•S.197b, National Hymne - Kaiser Wilhelm! (1876)•S.198, Wiegenlied (Chant du herceau) (1880) 摇篮曲•S.199, Nuages gris (Trübe Wolken) (1881) 灰色的云•S.199a, La lugubre gondola I (Der Trauergondol) [Vienna draft] (1882)•S.200, La lugubre gondola [2 pieces] (1882, 1885) 葬礼小船。

OSHA现场作业手册说明书

DIRECTIVE NUMBER: CPL 02-00-150 EFFECTIVE DATE: April 22, 2011 SUBJECT: Field Operations Manual (FOM)ABSTRACTPurpose: This instruction cancels and replaces OSHA Instruction CPL 02-00-148,Field Operations Manual (FOM), issued November 9, 2009, whichreplaced the September 26, 1994 Instruction that implemented the FieldInspection Reference Manual (FIRM). The FOM is a revision of OSHA’senforcement policies and procedures manual that provides the field officesa reference document for identifying the responsibilities associated withthe majority of their inspection duties. This Instruction also cancels OSHAInstruction FAP 01-00-003 Federal Agency Safety and Health Programs,May 17, 1996 and Chapter 13 of OSHA Instruction CPL 02-00-045,Revised Field Operations Manual, June 15, 1989.Scope: OSHA-wide.References: Title 29 Code of Federal Regulations §1903.6, Advance Notice ofInspections; 29 Code of Federal Regulations §1903.14, Policy RegardingEmployee Rescue Activities; 29 Code of Federal Regulations §1903.19,Abatement Verification; 29 Code of Federal Regulations §1904.39,Reporting Fatalities and Multiple Hospitalizations to OSHA; and Housingfor Agricultural Workers: Final Rule, Federal Register, March 4, 1980 (45FR 14180).Cancellations: OSHA Instruction CPL 02-00-148, Field Operations Manual, November9, 2009.OSHA Instruction FAP 01-00-003, Federal Agency Safety and HealthPrograms, May 17, 1996.Chapter 13 of OSHA Instruction CPL 02-00-045, Revised FieldOperations Manual, June 15, 1989.State Impact: Notice of Intent and Adoption required. See paragraph VI.Action Offices: National, Regional, and Area OfficesOriginating Office: Directorate of Enforcement Programs Contact: Directorate of Enforcement ProgramsOffice of General Industry Enforcement200 Constitution Avenue, NW, N3 119Washington, DC 20210202-693-1850By and Under the Authority ofDavid Michaels, PhD, MPHAssistant SecretaryExecutive SummaryThis instruction cancels and replaces OSHA Instruction CPL 02-00-148, Field Operations Manual (FOM), issued November 9, 2009. The one remaining part of the prior Field Operations Manual, the chapter on Disclosure, will be added at a later date. This Instruction also cancels OSHA Instruction FAP 01-00-003 Federal Agency Safety and Health Programs, May 17, 1996 and Chapter 13 of OSHA Instruction CPL 02-00-045, Revised Field Operations Manual, June 15, 1989. This Instruction constitutes OSHA’s general enforcement policies and procedures manual for use by the field offices in conducting inspections, issuing citations and proposing penalties.Significant Changes∙A new Table of Contents for the entire FOM is added.∙ A new References section for the entire FOM is added∙ A new Cancellations section for the entire FOM is added.∙Adds a Maritime Industry Sector to Section III of Chapter 10, Industry Sectors.∙Revises sections referring to the Enhanced Enforcement Program (EEP) replacing the information with the Severe Violator Enforcement Program (SVEP).∙Adds Chapter 13, Federal Agency Field Activities.∙Cancels OSHA Instruction FAP 01-00-003, Federal Agency Safety and Health Programs, May 17, 1996.DisclaimerThis manual is intended to provide instruction regarding some of the internal operations of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and is solely for the benefit of the Government. No duties, rights, or benefits, substantive or procedural, are created or implied by this manual. The contents of this manual are not enforceable by any person or entity against the Department of Labor or the United States. Statements which reflect current Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission or court precedents do not necessarily indicate acquiescence with those precedents.Table of ContentsCHAPTER 1INTRODUCTIONI.PURPOSE. ........................................................................................................... 1-1 II.SCOPE. ................................................................................................................ 1-1 III.REFERENCES .................................................................................................... 1-1 IV.CANCELLATIONS............................................................................................. 1-8 V. ACTION INFORMATION ................................................................................. 1-8A.R ESPONSIBLE O FFICE.......................................................................................................................................... 1-8B.A CTION O FFICES. .................................................................................................................... 1-8C. I NFORMATION O FFICES............................................................................................................ 1-8 VI. STATE IMPACT. ................................................................................................ 1-8 VII.SIGNIFICANT CHANGES. ............................................................................... 1-9 VIII.BACKGROUND. ................................................................................................. 1-9 IX. DEFINITIONS AND TERMINOLOGY. ........................................................ 1-10A.T HE A CT................................................................................................................................................................. 1-10B. C OMPLIANCE S AFETY AND H EALTH O FFICER (CSHO). ...........................................................1-10B.H E/S HE AND H IS/H ERS ..................................................................................................................................... 1-10C.P ROFESSIONAL J UDGMENT............................................................................................................................... 1-10E. W ORKPLACE AND W ORKSITE ......................................................................................................................... 1-10CHAPTER 2PROGRAM PLANNINGI.INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 2-1 II.AREA OFFICE RESPONSIBILITIES. .............................................................. 2-1A.P ROVIDING A SSISTANCE TO S MALL E MPLOYERS. ...................................................................................... 2-1B.A REA O FFICE O UTREACH P ROGRAM. ............................................................................................................. 2-1C. R ESPONDING TO R EQUESTS FOR A SSISTANCE. ............................................................................................ 2-2 III. OSHA COOPERATIVE PROGRAMS OVERVIEW. ...................................... 2-2A.V OLUNTARY P ROTECTION P ROGRAM (VPP). ........................................................................... 2-2B.O NSITE C ONSULTATION P ROGRAM. ................................................................................................................ 2-2C.S TRATEGIC P ARTNERSHIPS................................................................................................................................. 2-3D.A LLIANCE P ROGRAM ........................................................................................................................................... 2-3 IV. ENFORCEMENT PROGRAM SCHEDULING. ................................................ 2-4A.G ENERAL ................................................................................................................................................................. 2-4B.I NSPECTION P RIORITY C RITERIA. ..................................................................................................................... 2-4C.E FFECT OF C ONTEST ............................................................................................................................................ 2-5D.E NFORCEMENT E XEMPTIONS AND L IMITATIONS. ....................................................................................... 2-6E.P REEMPTION BY A NOTHER F EDERAL A GENCY ........................................................................................... 2-6F.U NITED S TATES P OSTAL S ERVICE. .................................................................................................................. 2-7G.H OME-B ASED W ORKSITES. ................................................................................................................................ 2-8H.I NSPECTION/I NVESTIGATION T YPES. ............................................................................................................... 2-8 V.UNPROGRAMMED ACTIVITY – HAZARD EVALUATION AND INSPECTION SCHEDULING ............................................................................ 2-9 VI.PROGRAMMED INSPECTIONS. ................................................................... 2-10A.S ITE-S PECIFIC T ARGETING (SST) P ROGRAM. ............................................................................................. 2-10B.S CHEDULING FOR C ONSTRUCTION I NSPECTIONS. ..................................................................................... 2-10C.S CHEDULING FOR M ARITIME I NSPECTIONS. ............................................................................. 2-11D.S PECIAL E MPHASIS P ROGRAMS (SEP S). ................................................................................... 2-12E.N ATIONAL E MPHASIS P ROGRAMS (NEP S) ............................................................................... 2-13F.L OCAL E MPHASIS P ROGRAMS (LEP S) AND R EGIONAL E MPHASIS P ROGRAMS (REP S) ............ 2-13G.O THER S PECIAL P ROGRAMS. ............................................................................................................................ 2-13H.I NSPECTION S CHEDULING AND I NTERFACE WITH C OOPERATIVE P ROGRAM P ARTICIPANTS ....... 2-13CHAPTER 3INSPECTION PROCEDURESI.INSPECTION PREPARATION. .......................................................................... 3-1 II.INSPECTION PLANNING. .................................................................................. 3-1A.R EVIEW OF I NSPECTION H ISTORY .................................................................................................................... 3-1B.R EVIEW OF C OOPERATIVE P ROGRAM P ARTICIPATION .............................................................................. 3-1C.OSHA D ATA I NITIATIVE (ODI) D ATA R EVIEW .......................................................................................... 3-2D.S AFETY AND H EALTH I SSUES R ELATING TO CSHO S.................................................................. 3-2E.A DVANCE N OTICE. ................................................................................................................................................ 3-3F.P RE-I NSPECTION C OMPULSORY P ROCESS ...................................................................................................... 3-5G.P ERSONAL S ECURITY C LEARANCE. ................................................................................................................. 3-5H.E XPERT A SSISTANCE. ........................................................................................................................................... 3-5 III. INSPECTION SCOPE. ......................................................................................... 3-6A.C OMPREHENSIVE ................................................................................................................................................... 3-6B.P ARTIAL. ................................................................................................................................................................... 3-6 IV. CONDUCT OF INSPECTION .............................................................................. 3-6A.T IME OF I NSPECTION............................................................................................................................................. 3-6B.P RESENTING C REDENTIALS. ............................................................................................................................... 3-6C.R EFUSAL TO P ERMIT I NSPECTION AND I NTERFERENCE ............................................................................. 3-7D.E MPLOYEE P ARTICIPATION. ............................................................................................................................... 3-9E.R ELEASE FOR E NTRY ............................................................................................................................................ 3-9F.B ANKRUPT OR O UT OF B USINESS. .................................................................................................................... 3-9G.E MPLOYEE R ESPONSIBILITIES. ................................................................................................. 3-10H.S TRIKE OR L ABOR D ISPUTE ............................................................................................................................. 3-10I. V ARIANCES. .......................................................................................................................................................... 3-11 V. OPENING CONFERENCE. ................................................................................ 3-11A.G ENERAL ................................................................................................................................................................ 3-11B.R EVIEW OF A PPROPRIATION A CT E XEMPTIONS AND L IMITATION. ..................................................... 3-13C.R EVIEW S CREENING FOR P ROCESS S AFETY M ANAGEMENT (PSM) C OVERAGE............................. 3-13D.R EVIEW OF V OLUNTARY C OMPLIANCE P ROGRAMS. ................................................................................ 3-14E.D ISRUPTIVE C ONDUCT. ...................................................................................................................................... 3-15F.C LASSIFIED A REAS ............................................................................................................................................. 3-16VI. REVIEW OF RECORDS. ................................................................................... 3-16A.I NJURY AND I LLNESS R ECORDS...................................................................................................................... 3-16B.R ECORDING C RITERIA. ...................................................................................................................................... 3-18C. R ECORDKEEPING D EFICIENCIES. .................................................................................................................. 3-18 VII. WALKAROUND INSPECTION. ....................................................................... 3-19A.W ALKAROUND R EPRESENTATIVES ............................................................................................................... 3-19B.E VALUATION OF S AFETY AND H EALTH M ANAGEMENT S YSTEM. ....................................................... 3-20C.R ECORD A LL F ACTS P ERTINENT TO A V IOLATION. ................................................................................. 3-20D.T ESTIFYING IN H EARINGS ................................................................................................................................ 3-21E.T RADE S ECRETS. ................................................................................................................................................. 3-21F.C OLLECTING S AMPLES. ..................................................................................................................................... 3-22G.P HOTOGRAPHS AND V IDEOTAPES.................................................................................................................. 3-22H.V IOLATIONS OF O THER L AWS. ....................................................................................................................... 3-23I.I NTERVIEWS OF N ON-M ANAGERIAL E MPLOYEES .................................................................................... 3-23J.M ULTI-E MPLOYER W ORKSITES ..................................................................................................................... 3-27 K.A DMINISTRATIVE S UBPOENA.......................................................................................................................... 3-27 L.E MPLOYER A BATEMENT A SSISTANCE. ........................................................................................................ 3-27 VIII. CLOSING CONFERENCE. .............................................................................. 3-28A.P ARTICIPANTS. ..................................................................................................................................................... 3-28B.D ISCUSSION I TEMS. ............................................................................................................................................ 3-28C.A DVICE TO A TTENDEES .................................................................................................................................... 3-29D.P ENALTIES............................................................................................................................................................. 3-30E.F EASIBLE A DMINISTRATIVE, W ORK P RACTICE AND E NGINEERING C ONTROLS. ............................ 3-30F.R EDUCING E MPLOYEE E XPOSURE. ................................................................................................................ 3-32G.A BATEMENT V ERIFICATION. ........................................................................................................................... 3-32H.E MPLOYEE D ISCRIMINATION .......................................................................................................................... 3-33 IX. SPECIAL INSPECTION PROCEDURES. ...................................................... 3-33A.F OLLOW-UP AND M ONITORING I NSPECTIONS............................................................................................ 3-33B.C ONSTRUCTION I NSPECTIONS ......................................................................................................................... 3-34C. F EDERAL A GENCY I NSPECTIONS. ................................................................................................................. 3-35CHAPTER 4VIOLATIONSI. BASIS OF VIOLATIONS ..................................................................................... 4-1A.S TANDARDS AND R EGULATIONS. .................................................................................................................... 4-1B.E MPLOYEE E XPOSURE. ........................................................................................................................................ 4-3C.R EGULATORY R EQUIREMENTS. ........................................................................................................................ 4-6D.H AZARD C OMMUNICATION. .............................................................................................................................. 4-6E. E MPLOYER/E MPLOYEE R ESPONSIBILITIES ................................................................................................... 4-6 II. SERIOUS VIOLATIONS. .................................................................................... 4-8A.S ECTION 17(K). ......................................................................................................................... 4-8B.E STABLISHING S ERIOUS V IOLATIONS ............................................................................................................ 4-8C. F OUR S TEPS TO BE D OCUMENTED. ................................................................................................................... 4-8 III. GENERAL DUTY REQUIREMENTS ............................................................. 4-14A.E VALUATION OF G ENERAL D UTY R EQUIREMENTS ................................................................................. 4-14B.E LEMENTS OF A G ENERAL D UTY R EQUIREMENT V IOLATION.............................................................. 4-14C. U SE OF THE G ENERAL D UTY C LAUSE ........................................................................................................ 4-23D.L IMITATIONS OF U SE OF THE G ENERAL D UTY C LAUSE. ..............................................................E.C LASSIFICATION OF V IOLATIONS C ITED U NDER THE G ENERAL D UTY C LAUSE. ..................F. P ROCEDURES FOR I MPLEMENTATION OF S ECTION 5(A)(1) E NFORCEMENT ............................ 4-25 4-27 4-27IV.OTHER-THAN-SERIOUS VIOLATIONS ............................................... 4-28 V.WILLFUL VIOLATIONS. ......................................................................... 4-28A.I NTENTIONAL D ISREGARD V IOLATIONS. ..........................................................................................4-28B.P LAIN I NDIFFERENCE V IOLATIONS. ...................................................................................................4-29 VI. CRIMINAL/WILLFUL VIOLATIONS. ................................................... 4-30A.A REA D IRECTOR C OORDINATION ....................................................................................................... 4-31B.C RITERIA FOR I NVESTIGATING P OSSIBLE C RIMINAL/W ILLFUL V IOLATIONS ........................ 4-31C. W ILLFUL V IOLATIONS R ELATED TO A F ATALITY .......................................................................... 4-32 VII. REPEATED VIOLATIONS. ...................................................................... 4-32A.F EDERAL AND S TATE P LAN V IOLATIONS. ........................................................................................4-32B.I DENTICAL S TANDARDS. .......................................................................................................................4-32C.D IFFERENT S TANDARDS. .......................................................................................................................4-33D.O BTAINING I NSPECTION H ISTORY. .....................................................................................................4-33E.T IME L IMITATIONS..................................................................................................................................4-34F.R EPEATED V. F AILURE TO A BATE....................................................................................................... 4-34G. A REA D IRECTOR R ESPONSIBILITIES. .............................................................................. 4-35 VIII. DE MINIMIS CONDITIONS. ................................................................... 4-36A.C RITERIA ................................................................................................................................................... 4-36B.P ROFESSIONAL J UDGMENT. ..................................................................................................................4-37C. A REA D IRECTOR R ESPONSIBILITIES. .............................................................................. 4-37 IX. CITING IN THE ALTERNATIVE ............................................................ 4-37 X. COMBINING AND GROUPING VIOLATIONS. ................................... 4-37A.C OMBINING. ..............................................................................................................................................4-37B.G ROUPING. ................................................................................................................................................4-38C. W HEN N OT TO G ROUP OR C OMBINE. ................................................................................................4-38 XI. HEALTH STANDARD VIOLATIONS ....................................................... 4-39A.C ITATION OF V ENTILATION S TANDARDS ......................................................................................... 4-39B.V IOLATIONS OF THE N OISE S TANDARD. ...........................................................................................4-40 XII. VIOLATIONS OF THE RESPIRATORY PROTECTION STANDARD(§1910.134). ....................................................................................................... XIII. VIOLATIONS OF AIR CONTAMINANT STANDARDS (§1910.1000) ... 4-43 4-43A.R EQUIREMENTS UNDER THE STANDARD: .................................................................................................. 4-43B.C LASSIFICATION OF V IOLATIONS OF A IR C ONTAMINANT S TANDARDS. ......................................... 4-43 XIV. CITING IMPROPER PERSONAL HYGIENE PRACTICES. ................... 4-45A.I NGESTION H AZARDS. .................................................................................................................................... 4-45B.A BSORPTION H AZARDS. ................................................................................................................................ 4-46C.W IPE S AMPLING. ............................................................................................................................................. 4-46D.C ITATION P OLICY ............................................................................................................................................ 4-46 XV. BIOLOGICAL MONITORING. ...................................................................... 4-47CHAPTER 5CASE FILE PREPARATION AND DOCUMENTATIONI.INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 5-1 II.INSPECTION CONDUCTED, CITATIONS BEING ISSUED. .................... 5-1A.OSHA-1 ................................................................................................................................... 5-1B.OSHA-1A. ............................................................................................................................... 5-1C. OSHA-1B. ................................................................................................................................ 5-2 III.INSPECTION CONDUCTED BUT NO CITATIONS ISSUED .................... 5-5 IV.NO INSPECTION ............................................................................................... 5-5 V. HEALTH INSPECTIONS. ................................................................................. 5-6A.D OCUMENT P OTENTIAL E XPOSURE. ............................................................................................................... 5-6B.E MPLOYER’S O CCUPATIONAL S AFETY AND H EALTH S YSTEM. ............................................................. 5-6 VI. AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSES............................................................................. 5-8A.B URDEN OF P ROOF. .............................................................................................................................................. 5-8B.E XPLANATIONS. ..................................................................................................................................................... 5-8 VII. INTERVIEW STATEMENTS. ........................................................................ 5-10A.G ENERALLY. ......................................................................................................................................................... 5-10B.CSHO S SHALL OBTAIN WRITTEN STATEMENTS WHEN: .......................................................................... 5-10C.L ANGUAGE AND W ORDING OF S TATEMENT. ............................................................................................. 5-11D.R EFUSAL TO S IGN S TATEMENT ...................................................................................................................... 5-11E.V IDEO AND A UDIOTAPED S TATEMENTS. ..................................................................................................... 5-11F.A DMINISTRATIVE D EPOSITIONS. .............................................................................................5-11 VIII. PAPERWORK AND WRITTEN PROGRAM REQUIREMENTS. .......... 5-12 IX.GUIDELINES FOR CASE FILE DOCUMENTATION FOR USE WITH VIDEOTAPES AND AUDIOTAPES .............................................................. 5-12 X.CASE FILE ACTIVITY DIARY SHEET. ..................................................... 5-12 XI. CITATIONS. ..................................................................................................... 5-12A.S TATUTE OF L IMITATIONS. .............................................................................................................................. 5-13B.I SSUING C ITATIONS. ........................................................................................................................................... 5-13C.A MENDING/W ITHDRAWING C ITATIONS AND N OTIFICATION OF P ENALTIES. .................................. 5-13D.P ROCEDURES FOR A MENDING OR W ITHDRAWING C ITATIONS ............................................................ 5-14 XII. INSPECTION RECORDS. ............................................................................... 5-15A.G ENERALLY. ......................................................................................................................................................... 5-15B.R ELEASE OF I NSPECTION I NFORMATION ..................................................................................................... 5-15C. C LASSIFIED AND T RADE S ECRET I NFORMATION ...................................................................................... 5-16。

英文版股权转让协议8篇

英文版股权转让协议8篇篇1equity transfer agreementThis Equity Transfer Agreement (hereinafter referred to as the "Agreement") is hereby executed by and between _________ (Transferor)and _________ (Transferee). In accordance with relevant laws and regulations, the parties agree as follows:I. Definition of Terms and BackgroundThis Agreement refers to the transfer of certain equity ownership from the Transferor to the Transferee in the context of a specific business entity (hereinafter referred to as the "Company").II. Purpose and Scope of the TransferThe purpose of this Agreement is to clarify the transfer of equity ownership in the Company from the Transferor to the Transferee. The transfer shall be carried out in accordance with the terms and conditions stipulated in this Agreement.III. Transfer of Equity Ownership1. Transferor hereby transfers to Transferee the equity ownership of _______ % (percentage)of the total equity ownership in the Company.2. After the completion of the transfer, Transferee shall become a shareholder of the Company and shall be entitled to all corresponding rights and obligations under relevant laws and regulations as well as the Company's articles of association.IV. Transfer Price and Payment Term1. The transfer price for the equity ownership is fixed atUS$_________ (price).2. Transferee shall make full payment for the equity ownership within ________ (payment deadline).V. Pre-existing Rights and Obligations1. Prior to the transfer, Transferor shall ensure that there are no disputes or legal proceedings related to the equity ownership being transferred.2. Transferor shall be responsible for all liabilities arising from the equity ownership prior to the transfer date. Any unfulfilled obligations shall be borne by Transferor.VI. Post-transfer Rights and Obligations1. After the completion of the transfer, Transferee shall be entitled to all corresponding rights and benefits of a shareholder in accordance with relevant laws and regulations as well as the Company's articles of association.2. Transferee shall assume all obligations related to the equity ownership after the transfer date, including fulfilling relevant responsibilities stipulated in relevant laws and regulations as well as the Company's articles of association.VII. ConfidentialityBoth parties shall keep confidential all information related to this Agreement, except for disclosure required by law or with consent from both parties.VIII. Termination and Repudiation1. If any party breaches any term or condition of this Agreement, the other party may terminate this Agreement in accordance with relevant laws and regulations.2. In case of any dispute arising from this Agreement, both parties shall seek to resolve it through friendly consultation. If consultation fails, either party may submit the dispute to a court of law for resolution.IX. Legal Effects of Agreement Execution篇2SHARE TRANSFER AGREEMENTThis Share Transfer Agreement (hereinafter referred to as the "Agreement") is made and executed on [Date] by and between [Name of the Seller] (hereinafter referred to as the "Seller"), and [Name of the Buyer] (hereinafter referred to as the "Buyer").PREAMBLEThe Seller is the rightful owner of shares representing ___% equity in [Name of the Company] (hereinafter referred to as the "Company"), and desires to transfer said shares to the Buyer. The Buyer desires to acquire said shares from the Seller.TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SHARE TRANSFER1. DEFINITION OF SHARESThe Seller holds ____ shares of the Company, representing ____% equity in the Company. The shares are being transferred as specified in this Agreement.2. TRANSFER OF SHARESUpon receipt of full payment as specified in this Agreement, the Seller agrees to transfer ownership of the shares to the Buyer. The transfer shall be evidenced by proper share transfer documents filed with the Company and its shareholder registry.3. PRICE AND PAYMENTThe total price for the shares is ____ USD. The Buyer shall make payment in full to the Seller's account within __ days from the date of this Agreement.4. WARRANTIES AND REPRESENTATIONSThe Seller hereby warrants and represents that:(a) The Seller is the rightful owner of the shares being transferred, and has full power and authority to execute this Agreement;(b) The shares are not subject to any litigation, encumbrance or claim by any third party; and(c) The transfer of shares shall not violate any provision of the Company's Articles of Association or other agreements binding on the Seller.5. INDEMNITYThe Seller shall indemnify and hold harmless the Buyer from any claims, suits or proceedings arising out of a breach of any warranties or representations made in this Agreement.6. TAXES AND OTHER COSTSAll taxes, duties, expenses and other costs associated with the transfer of shares shall be borne by the Buyer, except for any taxes arising from the transfer itself, which shall be borne by the Seller.7. TRANSFER OF COMPANY BOOKS AND RECORDSUpon completion of the transfer, all books, records and other documents pertaining to the shares shall be transferred to the Buyer. The Seller shall provide reasonable assistance to facilitate smooth transition of ownership.8. CONFIDENTIALITYBoth parties shall keep confidential all information related to this Agreement and its execution except as required by law or court order. Any disclosure in breach of confidentiality obligations shall be subject to appropriate legal action.9. TERMINATIONThis Agreement may be terminated prior to its intended expiry date if: (a) there is a breach of any term or condition of this Agreement by either party; or (b) if the Company becomes subject to bankruptcy or liquidation proceedings or any similar action that could affect adversely the transfer of shares under this Agreement. Any termination shall be subject to mutual agreement or legal provisions as applicable.10. MISCELLANEOUSTHE SELLER:Name:Address:Date:Signature:THE BUYER:Name:Address:Date:Signature:This Share Transfer Agreement has been executed on________ day of _______ at ___________. witnesses whereunto, parties have affixed their hands on said day in order to manifest their due execution hereof.(见证人在此附签名盖章,各方已签署本协议以证明其正式执行)鉴此。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。