外文翻译--公司的股权结构、公司治理和资本结构决策——来自加纳的实证研究

毕业论文(设计)外文文献翻译及原文

金融体制、融资约束与投资——来自OECD的实证分析R.SemenovDepartment of Economics,University of Nijmegen,Nijmegen(荷兰内梅亨大学,经济学院)这篇论文考查了OECD的11个国家中现金流量对企业投资的影响.我们发现不同国家之间投资对企业内部可获取资金的敏感性具有显著差异,并且银企之间具有明显的紧密关系的国家的敏感性比银企之间具有公平关系的国家的低.同时,我们发现融资约束与整体金融发展指标不存在关系.我们的结论与资本市场信息和激励问题对企业投资具有重要作用这种观点一致,并且紧密的银企关系会减少这些问题从而增加企业获取外部融资的渠道。

一、引言各个国家的企业在显著不同的金融体制下运行。

金融发展水平的差别(例如,相对GDP的信用额度和相对GDP的相应股票市场的资本化程度),在所有者和管理者关系、企业和债权人的模式中,企业控制的市场活动水平可以很好地被记录.在完美资本市场,对于具有正的净现值投资机会的企业将一直获得资金。

然而,经济理论表明市场摩擦,诸如信息不对称和激励问题会使获得外部资本更加昂贵,并且具有盈利投资机会的企业不一定能够获取所需资本.这表明融资要素,例如内部产生资金数量、新债务和权益的可得性,共同决定了企业的投资决策.现今已经有大量考查外部资金可得性对投资决策的影响的实证资料(可参考,例如Fazzari(1998)、 Hoshi(1991)、 Chapman(1996)、Samuel(1998)).大多数研究结果表明金融变量例如现金流量有助于解释企业的投资水平。

这项研究结果解释表明企业投资受限于外部资金的可得性。

很多模型强调运行正常的金融中介和金融市场有助于改善信息不对称和交易成本,减缓不对称问题,从而促使储蓄资金投着长期和高回报的项目,并且提高资源的有效配置(参看Levine(1997)的评论文章)。

因而我们预期用于更加发达的金融体制的国家的企业将更容易获得外部融资.几位学者已经指出建立企业和金融中介机构可进一步缓解金融市场摩擦。

A Natural-resource based view of the firm

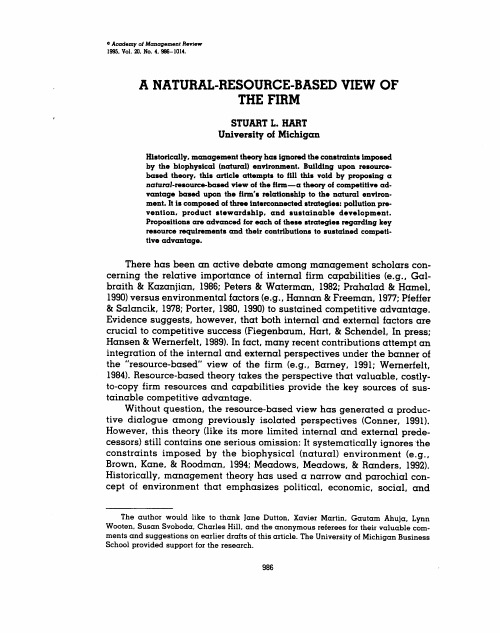

c Academy01Management Review1995.Vol.20.No.4.986-1014.A NATURAL-RESOURCE-BASED VIEW OFTHE FIRMSTUARTL.HARTUniversity of MichiganHistorically,management theory has ignored the constraints imposedby the biophysical(natural)environment.Building upon resource-based theory,this article attempts to flll this void by proposing anatural-resource-based view of the flrm-a theory of competitive ad-vantage based upon the firm's relationship to the natural environ-ment.It is composed of three interconnected strategies:pollution pre-vention,product stewardship,and sustainable development.Propositions are advanced for each of these strategies regarding keyresource requirements and their contributions to sustained competi-tive advantage.There has been an active debate among management scholars con-cerning the relative importance of internal firm capabilities(e.g.,Gal-braith&Kazanjian,1986;Peters&Waterman,1982;Prahalad&Hamel. 1990)versus environmental factors(e.g.,Hannan&Freeman,1977;Pfeffer &Salancik,1978;Porter,1980,1990)to sustained competitive advantage. Evidence suggests,however,that both internal and external factors are crucial to competitive success(Fiegenbaum,Hart,&Schendel.In press; Hansen&Wernerfelt,1989).In fact,many recent contributions attempt an integration of the internal and external perspectives under the banner of the"resource-based"view of the firm(e.g.,Barney,1991;Wernerfelt, 1984).Resource-based theory takes the perspective that valuable,costly-to-copy firm resources and capabilities provide the key sources of sus-tainable competitive advantage.Without question,the resource-based view has generated a produc-tive dialogue among previously isolated perspectives(Conner,1991). However,this theory(like its more limited internal and external prede-cessors)still contains one serious omission:It systematically ignores the constraints imposed by the biophysical(natural)environment(e.g., Brown,Kane,&Roodman,1994;Meadows,Meadows,&Randers.1992). Historically,management theory has used a narrow and parochial con-cept of environment that emphasizes political.economic,social.andThe author would like to thank Jane Dutton.Xavier Martin.Gautam Ahuja.Lynn Wooten.Susan Svoboda.Charles Hill.and the anonymous referees for their valuable com-ments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this article.The University of Michigan Business School provided support for the research.9861995Hart987 technological aspects to the virtual exclusion of the natural environment (Shrivastava,1994;Shrivastava&Hart,1992;Stead&Stead,1992).Given the growing magnitude of ecological problems,however,this omission has rendered existing theory inadequate as a basis for identifying impor-tant emerging sources of competitive advantage.The goal of this article is,therefore,to insert the natural environment into the resource-based view-to develop a natural-resource-based view of the firm.Accordingly,the first section of the paper reviews resource-based theory,highlighting the relationships among firm resources,capabilities, and sources of competitive advantage.Next,I discuss the driving forces behind the natural-resource-based view-the growing scale and scope of human activity and its potential for irreversible environmental damage on a global scale.The natural-resource-based view is then developed with the connection between the environmental challenge and firm re-sources operationalized through three interconnected strategic capabili-ties:pollution prevention,product stewardship,and sustainable devel-opment.Propositions are then developed connecting these strategies to key resource requirements and sustained competitive advantage.The article closes with suggestions for a future research agenda.THE RESOURCE-BASED VIEWResearchers in the field of strategic management have long under-stood that competitive advantage depends upon the match between dis-tinctive internal(organizational)capabilities and changing external(en-vironmental)circumstances(Andrews,1971;Chandler,1962;Hofer& Schendel,1978;Penrose,1959).However,it has only been during the past decade that a bona fide theory,known as the resource-based view of the firm,has emerged,articulating the relationships among firm resources, capabilities,and competitive advantage.Figure1provides a graphical summary of these relationships and some of the key authors associated with the core ideas.The concept of competitive advantage has been treated extensively in the management literature.Porter(1980,1985)thoroughly developed the concepts of cost leadership and differentiation relative to competitors as two important sources of competitive advantage:a low-cost position enables a firm to use aggressive pricing and high sales volume,whereas a differentiated product creates brand loyalty and positive reputation, facilitating premium pricing.Decisions concerning timing(e.g.,moving early versus late)and commitment level(e.g.,entering on a large scale versus more incrementally)also are crucial in securing competitive ad-vantage(Ghemawat,1986;Lieberman&Montgomery,1988).If a firm makes an early move or a large-scale move,it is sometimes possible to preempt competitors by setting new standards or gaining preferred ac-cess to critical raw materials,locations,production capacity,or custom-ers.Preemptive commitments thus enable firms to gain a strong focus and988Academy of Management Review OctoberFIGURE 1The Resource-Based View•Andrews (1971)•Hofer and Schendel (1978)•Prahalad &Hamel(1990)•Ulrich &Lake (1991)J ·Wernerfelt (1984)•Deirickx &Cool(1989)•Reed &DeFillippi(1990)•Barney(1991)J Competitive Advantage •Cost or differentiation •Preemption •Future position Capabilities •Technology •Production •Design •Distributio •Procurement •Service ResourcesBasic Requirements Key Characteristics•Valuable ~•Tacit (causally•Nonsubstitutable ambiguous)•Socially complex•Rare (firm specific)•Porter (1980.1985)•Ghemawat (1986)•Lieberman &Montgomery (1988)•Hamel &Prahalad(1994)•Polanyi (1962)•Rumelt (1984)•Teece (1987)•Itami (1987)dominate a particular niche.either through lower costs.differentiated products.or both (Ghemawat.1986;Porter.1980).Finally.Hamel and Pra-halad (1989.1994)have emphasized the importance of "competing for the future"as a neglected dimension of competitive advantage.According to this view.the firm must be concerned not only with profitability in the present and growth in the medium term.but also with its future position and source of competitive advantage.This view requires explicit strate-gizing about how the firm will compete when its current strategy config-uration is either copied or made obsolete.The connection between firms'capabilities and competitive advan-tage also has been well established in literature.Andrews (1971)ter.Hofer and Schendel (1978)and Snow and Hrebiniak (1980)noted the centrality of "distinctive competencies"to competitive success.More re-cently.Prahalad and Hamel (1990)and Ulrich and Lake (1991)reempha-sized the strategic importance of identifying.managing.and leveraging "core competencies"rather than focusing only on products and markets in business planning.The resource-based view takes this thinking one step further:It posits that competitive advantage can be sustained only if the capabilities creating the advantage are supported by resources that are not easily duplicated by competitors.In other words.firms'resources must raise "barriers to imitation"(Rumelt.1984).Thus.resources are the basic units of analysis and include physical and financial assets as well as employees'skills and organizational (social)processes.A firm's capabilities result from bundles of resources being brought to bear on1995Hart989 particular value-added tasks(e.g.,design for manufacturing,just-in-time production).Although the terminology has varied(Peteraf,1993),there appears to be general agreement in the management literature about the resource characteristics that contribute to a firm's sustained competitive advan-tage.At the most basic level,such resources must be valuable(Le.,rent producing)and nonsubstitutable(Barney,1991;Dierickx&Cool,1989).In other words,for a resource to have enduring value,it must contribute to a firm capability that has competitive significance and is not easily ac-complished through alternative means.Next,strategically important re-sources must be rare and/or specific to a given firm(Barney.1991;Reed& DeFillippi,1990).That is,they must not be widely distributed within an industry and/or must be closely identified with a given organization.mak-ing them difficult to transfer or trade(e.g..a brand image or an exclusive supply arrangement).Although physical and financial resources may produce a temporary advantage for a firm,they often can be readily acquired on factor markets by competitors or new entrants.Conversely,a unique path through history may enable a firm to obtain unusual and valuable resources that cannot be easily acquired by competitors(Bar-ney,1991).Finally,and perhaps most important,such resources must be diffi-cult to replicate because they are either tacit(causally ambiguous)or socially complex(Teece,1987;Winter.1987).Tacit resources are skill based and people intensive.Such resources are"invisible"assets based upon learning-by-doing that are accumulated through experience and refined by practice(Itami,1987;Polanyi,1962).Socially complex resources depend upon large numbers of people or teams engaged in coordinated action such that few individuals,if any,have sufficient breadth of knowl-edge to grasp the overall phenomenon(Barney,1991;Reed&DeFillippi, 1990).The strategic significance of firms'resources and capabilities has been heightened by recent observations that companies that are better able to understand,nurture.and leverage core competencies outperform those that are preoccupied with more conventional approaches to strate-gic business planning(Prahalad&Hamel,1990).However.a firm's com-mitment to the existing competency base also may make it difficult to acquire new resources or capabilities.Put another way,the resource-based view may lead to an organization that is like the proverbial"child with a hammer"-everything starts looking like a nail.Technological discontinuities or shifts in external circumstances may render existing competencies obsolete or,at a minimum,invite the rapid development of new resources(Tushman&Anderson,1986).Under such circumstances, core competencies might become"core rigidities"(Leonard-Barton.1992). In this article,I argue that one of the most important drivers of new resource and capability development for firms will be the constraints and challenges posed by the natural(biophysical)environment.990Academy of Management ReviewOctober THE CHALLENGE OF THE NATURAL ENVIRONMENTWhat defense has been to the world's leaders for the past40years,the environment will be for the next40.(The Economist,1990)The above quote summarizes the immensity of the challenge posed by the natural environment.Consider that since the end of World War II,•the human population has grown from about2billion to over5billion(Keyfitz,1989);•the global economy has grown over IS-fold(WorldBank,1992);•consumption of fossil fuels has increased by a factor of25(Brown,Kane&Hoodman,1994);a nd•industrial production has increased by a factor of40(Schmidheiny,1992).Unfortunately,the environmental impacts associated with this activ-ity also have multiplied.For example,air and water pollution,toxic emis-sions,chemical spills,and industrial accidents have created regional environmental and public health crises for thousands of communities around the world(Brown,Kane,&Roodman,1994;Shrivastava,1987).The composition of the atmosphere has been altered more in the past100 years-through fossil-fuel use,agricultural practices,and deforesta-tion-than in the previous18,000(Graedel&Crutzen,1989).Climate changes,which might produce both rising ocean levels and further de-sertification,could threaten the very fabric of human civilization as we know it(Schneider,1989).The world's18major fisheries already have reached or exceeded maximum sustained yield levels(Brown&Kane, 1994).If current consumption rates continue,all virgin tropical forests will be gone within50years,with a consequent loss of50percent or more of the world's species(Wilson,1989).Reduced quality of life in the devel-oped world,severe human health problems,and environmentally in-duced political upheaval in the developing world could all result(Homer-Dixon,BoutwelL&Rathjens,1993;Kaplan,1994).In short,the scale and scope of human activity have accelerated during the past40years to the point where they are now having impacts on a global scale.Consider,for example,that it took over10,000gener-ations for the human population to reach2billion,but only a single lifetime to grow from2to over5billion(Gore,1992).During the next40 years,the human population is expected to double again,to10billion, before leveling off sometime in the middle of the next century(Keyfitz, 1989).Even with world GNP currently at about$25trillion,it may be necessary to increase economic activity five-to tenfold just to provide basic amenities to this population(MacNeill,1989;Ruckelshaus,1989). This level of economic production probably will not be ecologically sus-tainable using existing technologies and production methods-a tenfold increase in resource use and waste generation would almost certainly1995Hart991 stress the earth's natural systems beyond recovery(Commoner,1992; Meadows,Meadows,&Randers,1992;Schmidheiny,1992).The next40years thus present an unprecedented challenge:either alter the nature of economic activity or risk irreversible damage to the planet's basic ecological systems.This portends nothing less than a"par-adigm shift"for the field of strategic management because it appears that few,if any,of our past economic and organizational practices can be continued for long into the future;they are simply not environmentally sustainable.Over the next decade,businesses will be challenged to cre-ate new concepts of strategy,and it seems likely that the basis for gaining competitive advantage in the coming years will be rooted increasingly in a set of emerging capabilities such as waste minimization,green product design,and technology cooperation in the developing world(Gladwin, 1992;Hart,1994;Kleiner,1991;Schmidheiny,1992).For the resource-based view to remain relevant,its creators must embrace and internalize the tremendous challenge created by the natural environment:Strategists and organizational theorists must begin to grasp how environmentally oriented resources and capabilities can yield sustainable sources of com-petitive advantage.A NATURAL-RESOURCE-BASED VIEW OF THE FIRMIn the future,it appears inevitable that businesses(markets)will be constrained by and dependent upon ecosystems(nature).1In other words, it is likely that strategy and competitive advantage in the coming years will be rooted in capabilities that facilitate environmentally sustainable economic activity-a natural-resource-based view of the firm.In this sec-tion,I introduce a conceptual framework composed of three intercon-nected strategies:pollution prevention,product stewardship,and sus-tainable development.The significant driving forces behind each of these are briefly discussed,and an introduction to the key resources and sources of competitive advantage associated with each strategy is given (Table1).Key resources and capabilities also affect the ability of the firm to sustain its competitive advantage.These theoretical linkages are de-veloped in much greater depth in the section titled"Theory Develop-ment."I In the long run.I argue that a natural-resource-based view is a physical(not a legal or regulatory)requirement.However.there may be temporary policy reversals that serve to slow this evolutionary path.For example,the current antiregulatory stance in the U.S. Congress suggests that domestIc firms and international firms operating in the United States may be under less direct environmental regulatory pressure.at least for the next few years.This anomaly,however.neither nullifies the drivers for greening in other parts of the developed world.nor does it slow the need for rethinking corporate behavior in developing markets.992Academy of Management ReviewTABLE1A Natural-Resource-Based View:Conceptual FrameworkOctoberStrategic Capability PollutionPrevention ProductStewardship SustainableDevelopmentEnvironmentalDriving ForceMinimize emissions.effluents.&wasteMinimize life-cycle cost ofproductsMinimize environmentalburden of firm growthand developmentKeyResourceContinuous improvementStakeholder integrationShared visionCompetitiveAdvantageLower costsPreempt competitorsFuture positionPollution PreventionDuring the past decade there has been tremendous pressure for firms to minimize or eliminate emissions,effluents,and waste from their oper-ations.In1986,for example,the Superfund Amendments and Reauthori-zation Act(SARA)was passed in the United States,requiring that com-panies publicly disclose their emission levels of some300toxic or hazardous chemicals through what has become known as the toxic re-lease inventory(TRI).Managers now understood the extent of their firms' impact on the environment and recognized that pollution stems from in-efficient use of material and human resources.Indeed,the first year that the TRI was used(1988)revealed that panies alone emitted10.4 billion pounds of toxic materials to the environment.This sobering real-ization caused management in the most affected industries-petro-chemicals,pulp and paper,automotive,and electronics-to fundamen-tally rethink its approach to pollution abatement.In fact,since the late 1980s,a focus on emissions reduction and pollution abatement has swept industrial operations worldwide(Smart,1992).Pollution abatement can be achieved through two primary means:(a) control:emissions and effluents are trapped,stored,treated,and dis-posed of using pollution-control equipment or(b)prevention:emissions and effluents are reduced,changed,or prevented through better house-keeping,material substitution,recycling,or process innovation(Cairn-cross,1991;Frosch&Gallopoulos,1989;Willig,1994).The latter approach reduces pollution during the manufacturing process while producing saleable goods.The former approach entails expensive,nonproductive pollution-control equipment.Pollution prevention thus appears analo-gous,in many respects,to total quality management(TQM);it requires extensive employee involvement and continuous improvement of emis-sions reduction,rather than reliance on expensive"end-of-pipe"pollu-tion-control technology(lmai,1986;Ishikawa&Lu,1985;Roome,1992).Through pollution prevention,companies can realize significant sav-ings,resulting in a cost advantage relative to competitors(Hart&Ahuja, 1994;Romm,1994).Indeed,pollution prevention may save not only the cost of installing and operating end-of-pipe pollution-control devices,but1995Hart993 it also may increase productivity and efficiency(Smart,1992;Schmid-heiny,1992).Less waste means better utilization of inputs,resulting in lower costs for raw materials and waste disposal(Young,1991).Pollution prevention also may reduce cycle times by simplifying or removing un-necessary steps in production operations(Hammer&Champy,1993;Stalk &Hout,1990).Furthermore,pollution prevention offers the potential to cut emissions well below required levels,reducing the firm's compliance and liability costs(Rooney,1993).Thus,a pollution-prevention strategy should facilitate lower costs,which,in turn,should result in enhanced cash flow and profitability for the firm.Indeed,pioneering programs like3M's Pol-lution Prevention Pays(3P)and Dow's Waste Reduction Always Pays (WRAP)have produced hundreds of millions of dollars in cost savings over the past decade(Smart,1992).At Dow,for example,it has been estimated that"end-of-pipe"pollution-control projects lose16%on every dollar invested.Conversely,the return on pollution-prevention projects has averaged better than60%for the past10years(Buzzelli,1994).Evidence also suggests that in the early stages of pollution preven-tion,there is a great deal of"low hanging fruit"-easy and inexpensive behavioral and material changes that result in large emission reductions relative to costs(Hart&Ahuja,1994;Rooney,1993).As the firm's environ-mental performance improves,however,further reductions in emissions become progressively more difficult,often requiring significant changes in processes or even entirely new production technology(Frosch&Gal-lopoulos,1989).For example,a pulp plant might make significant reduc-tions in emissions through better housekeeping,equipment maintenance, and incremental process improvement.Eventually,however,diminishing returns set in,and few significant additional reductions are possible without entirely new technology such as chlorine-free bleaching equip-ment to eliminate organochloride emissions.Thus,as the firm moves closer to"zero emissions,"reductions will become more capital intensive and may require broader changes in underlying product design and tech-nology(Walley&Whitehead,1994).Product StewardshipAs noted previously,pollution prevention focuses on new capability building in production and operations.However,activities at every step of the value chain-from raw material access,through production pro-cesses,to disposition of used products-have environmental impacts, and these will almost certainly need to be"internalized"in the future (Costanza,1991;Daly&Cobb,1989).Product stewardship thus entails integrating the"voice of environment,"that is,external(stakeholder)per-spectives,into product design and development processes(Allenby,1991; Fiksel,1993).Indeed,during the past decade,virtually every major industrialized country in the world(except the United States)has adopted a government-sponsored program for certifying products as environmentally responsi-994Academy of Management Review October ble(Abt Associates.1993).In the United States.several competing private initiatives rate products on environmental criteria.including organiza-tions such as Green Cross and Green Seal.A common feature of such programs is the use of some form of life-cycle analysis(LCA)(Davis,1993). LCA is used to assess the environmental burden created by a product system from"cradle to grave"(Keoleian&Menerey.1993).For a product to achieve low life-cycle environmental costs.designers need to(a)mini-mize the use of nonrenewable materials mined from the earth's crust,(b) avoid the use of toxic materials.and(c)use living(renewable)resources in accordance with their rate of replenishment(Robert.1995).Also,the product-in-use must have a low environmental impact and be easily com-posted.reused.or recycled at the end of its useful life(Kleiner,1991; Shrivastava&Hart.In press).Such life-cycle thinking is being pushed even a step further.In1990. for example.the German government proposed the first product"take-back"law(Management Institute for Environment and Business.1993). According to this law.for selected industries(e.g..automobiles),custom-ers were given the right to return spent products to the manufacturer at no charge.In turn.manufacturers would be prevented from disposing of these used or"junk"products.The specter of this law created a tremen-dous incentive for companies to learn to design products and packaging that could be easily composted.reused.or recycled in order to avoid what would become astronomical disposal costs and penalties.Similar initia-tives are now being considered by the European Union.Japan.and even the United States.It thus seems reasonable to conclude that firms in the developed markets will be driven increasingly to minimize the life-cycle environ-mental costs of their product systems.Through product stewardship. firms can(a)exit environmentally hazardous businesses,(b)redesign existing product systems to reduce liability.and(c)develop new products with lower life-cycle costs.The relative importance of these three activi-ties will vary according to the nature of the firm's existing product port-folio.Proctor and Gamble.for example.has dedicated much of its prod-uct-stewardship efforts toward altering its core detergent and cleaning products.which historically have been based on phosphates and sol-vents.Church and Dwight,however.whose core products are based on environmentally benign baking soda.has been able to orient its product stewardship efforts around new product development in both the con-sumer and industrial markets.For start-up firms.product stewardship can form the cornerstone for firm strategy.because there are no pre-existing commitments to products,facilities.or manufacturing processes.However.because the market for"green"products is seldom large or lucrative early on(Roper.1992).competitive advantage might best be secured initially through competitive preemption(Ghemawat.1986;Lie-berman&Montgomery.1988).This advantage can be achieved through two primary means:(a)by gaining preferred or exclusive access to1995Hart995 important,but limited resources(e.g.,raw materials,locations,produc-tive capacity,or customers)or(b)by establishing rules,regulations,or standards that are uniquely tailored to the firm's capability.Preferred access has provided the backbone for many successful com-petitive strategies(e.g.,Wal-Mart's location-based preemption of rural markets for discount stores,Dupont's capacity-based preemption of the world titanium dioxide business).Several recent start-up ventures have used preferred access as a basis for product-stewardship strategies.For example,"Reclaim"is a start-up company whose proprietary product-cold-patch paving material for road repair-is made from recycled as-phalt shingles.Although this product is patented and is highly functional at a reasonable cost,a key to the company's product-stewardship strategy was its ability to gain preferred access to the raw material(asphalt shin-gles from abandoned buildings).2The second means for competitive preemption-raising barriers through the setting of rules,regulations,or standards-also has provided the basis for many successful competitive strategies(e.g.,Matsushita's VHS strategy in video cassette recorders).BMW's product-stewardship strategy in automobile recycling offers a good example of preemption, both through preferred access and standard setting.In1990,BMW initi-ated a"design-for-disassembly"process in Germany that it hoped would preempt the proposed government"take-back"policy described previ-ously.By acting as the first mover,it was able to capture the few sophis-ticated German dismantler firms as part of an exclusive recycling infra-structure,thereby gaining a cost advantage over competitors who were left to fight over smaller,unlicensed operations or devote precious capital to building their own dismantling infrastructure.This move enabled BMW to build an early reputation by taking back and recycling its products that were already on the.road as a precursor to the introduction of its new line of design-for-environment(DfE)automobiles.Once the company had de-veloped and demonstrated the take-back infrastructure through its exclu-sive BMW dismantlers and disassemblers,executives succeeded in es-tablishing the BMW approach as the German national standard.This move required other car companies to follow BMW's lead,but at substan-tially higher costs.Market research suggests there is a vast amount of unclaimed repu-tation"space"with respect to corporate environmental performance.A2Reclaim chose the New York/NewJersey region as its supply source,given the exten-sive building demolition and high landfill tipping fees in this area.Previously,scrap ma-terials from demolished buildings were hauled to the landfill,at substantial cost to the contractor.Reclaim negotiated with the contractors for these asphalt shingles.The company gained exclusive access to a virtually free raw material.and the contractors avoided steep tipping fees.Furthermore,extensive building demolition and high tipping fees did not exist in any other major metropolitan area in the United States,making Reclaim's preemptive strategy virtually impregnable.。

基于现金流量的公司价值分析 外文原文 精品

Free Cash Flow, Enterprise Value, and Investor CautionHarlan PlattCollege of Business AdministrationNortheastern UniversitySebahattin DemirkanSchool of ManagementSUNY Binghamton UniversityMarjorie PlattCollege of Business AdministrationNortheastern UniversityAbstract:By analyzing actual cash flows in comparison with enterprise values (market capitalization plus debt minus cash) we document that the market dramaticall undervalues firms. The findings suggest that the equity market appears to have an extraordinarily high discount rate which negates future earnings in the calculus of firm value. That is, the discount rate is so high that the vast majority of future cash flows are virtually ignored.Our research finds that stock prices do not reflect future corporate earnings. This finding contrasts with the well known statement in finance textbooks that “the value of a firm equals the present discounted value of future cash flows.” In fact, we find that enterprise values are substantially less than the present discounted value of future cash flows. A one-dollar increase in future cash flows produces only a 75 cent increase in a firm’s enterprise value.The implication of our work is clear: companies are worth far more than the market believes. This provides strong support to the idea behind the private equity industry. We realize that of late private equity firms have overpaid for acquisitions and may lose their entire investment during the current phase of deleveraging. Yet, if private equity firms acquire companies at reasonable prices using less debt, they are likely to create substantial value as a consequence of the fact that companies are so undervalued by the market relative to their cash flows.There are no previous research efforts following our methodological design based on actual cash flows. Rather, .prior research studies have focused on the relationship between forecasted cash flows (by market analysts) and enterprise value. Our approach focuses on a different question – the relationship between discounted future cash flows and the current market value as posited by financial theory.Keywords: Enterprise Value, Actual Cash Flow, Cash Flow, Valuation1.IntroductionThe common explanation provided in finance textbooks for the value of the firm is that it equals the present discounted value of future free cash flows (FCF). Few analysts or market observers disagree with this statement. Despite its universal acceptance, there are few studies of the basic FCF proposition and the theory that underlies the science of valuation. In this paper, we explore the question of whether the value of the firm is related to its future cash flows. Existent literature on this subject includes a few studies conceptually similar to ours and a large body of work on questions peripheral to the basic issue addressed in this paper. Those related works use the FCF valuation theory to address issues of market efficiency. Our work is directed at valuation and not the market efficiency question.Obviously actual future cash flows are unknown when analysts estimate value. Lacking actual future cash flow data, analysts create careful projections of annual cash flows for several years, usually less than 10, and then estimate cash flows in additional years with a terminal value. Public companies have value forecasts prepared for them by many unrelated individuals and organizations. Some forecasts are too optimistic while others are too pessimistic. Presumably optimistic forecasters are buyers of securities while pessimistic forecasters are sellers. A secu rity’s market price would then be the share value that clears the market of optimists and pessimists.The specific projections of all individual forecasters are unavailable. What is known, at a point in time, is the actual market capitalization and enterprise value (EV) that results from the interactions of these many forecasts. Some researchers have tested the relationship between the value of the firm and cash flow forecasts by obtaining a sample of analyst’s forecasts or forecasts from other published so urces. We instead substitute actual cash flows for forecasted cash flows. Our null hypothesis assumes that the market-clearing forecast of future free cash flows is correct for every company. In that case, actual cash flows can be substituted for cash flow forecasts. If the market clearing forecast is too optimistic (pessimistic) then the observed EV exceeds (is less than) the present discounted value of actual free cash flows. Our first empirical test examines how closely EV compare with the present discounted value of actual subsequent cash flows. Finding the theory to be less than complete, our second empirical exercise considers additional explanatory factors to explain EV. This portion of the paper tests whether the accepted FCF theory fully explains EVs.2.LITERATURE REVIEWThe earliest written discussion of the idea that the value of something is related to its future cash flows comes from Johan de Witt (1671); though the basic idea traces back to the early Greeks1. In modern times, the idea that corporate value is related to 1See Daniel Rubinstein, Great Moments in Financial Economics, Journal of Investment Management (Winter 2003).future dividends was first described by John Williams (1938)2. Durand (1957) observed what later became known as the Gordon growth model, that a dividend growing at a constant rate forever can be capitalized to estimate a firm’s va lue.The literature that tests the FCF theory examines a variety of valuation methods. All of these tests rely on forecasts of cash flows or earnings made contemporaneously with the valuation estimate. That is, starting in a given year, they compare actual EV against forecasts, made that year, for the same company. For example, Francis, Olsson, and Oswald (2000) compared three theoretical valuation models-- discounted dividends (DD), discounted FCF, and discounted abnormal earnings (AE)3– by analyzing Value Line annual forecasts for the period 1989 – 1993 for a sample of2,907 firm years that ranges between 554 and 607 firms per year. They found that the AE model had a 27% lower absolute prediction error than the FCF model and a 57% lower absolute prediction error than the DD model.Sougiannis and Yaekura (2001) also consider three multiperiod accounting based valuation methods: an earnings capitalization model (similar to FCF), residual income (a version of AE) without a terminal value, and residual income with a terminal value4. They put analyst’s earnings forecasts into the three theoretical models and find overall that they provide greater insight than merely relying on current earnings, book values or dividends. Their sample covered 36,532 firm years over the period 1981 – 1998 of which 22,705 consisted of one year forecasts, 9,420 of two year forecasts, 1,279 of three year forecasts, and 3,128 of four year forecasts. They found that the AE model with a terminal value most accurately predicted current equity values in 48% of cases, the FCF model was most accurate in 18% of cases, and the AE without a terminal value was most accurate in 13% of cases. Current income and book values provided the best forecasts for the remaining 21% of the sample.Liu, Nissim and Thomas (LNT) (2002) in an article similar to Sougiannis and Yaekura (2001) found that multiples based on analyst’s forward earnings projections (made in the same year) explain stock prices within 15% of their actual value while historical earnings, cash flow measures, book value, and sales were not nearly as insightful. LNT argue that multiples value future profits and risk better than present value forecasts. Their multiples are derived based on current earnings and stock prices.Gentry, Whitford, Sougiannis, and Aoki (2001) took a different theoretical and empirical approach comparing an accounting method which looked at the discounted value of future net income to a finance method that looked at the discounted value of FCFs to equity. Their analysis tested the closeness with which each model predicted capital gains. The sample included both US (1981 – 1998) and Japanese companies (1985– 1998). Each year had between 881 and 1034 US companies and 166 to 3652See, Aswath Damodaran, “Valuation Approaches and Metrics: A Survey of the Theory,” Stern School of Business Working Paper, November 2006. Damodaran notes that Ben Graham saw the connection between value and dividends but not with a discounted valuation model.3Abnormal earnings as discussed by Ohlson (1995) assume that the value of equity equals the sum ofbook value plus abnormal earnings.4They also report that a 4% constant growth rate provides the best terminal value, even better than onesbased on individual firm growth forecasts.Japanese companies. They found that the FCFs to equity method were not closely related to capital gains rates of return for either US or Japanese companies. In the US they found a strong relationship between cash flows associated with operations, interest, and financing (the accounting method) to capital gains; no similar relationship was found in Japan.Finally, Dontoh, Radhakrishnan, and Ronen (2007) compared the association between stock prices and accounting figures. They found that the association between stock prices and accounting numbers has been declining over time. They suggest that this may be due to increased noise in stock prices resulting from higher trading volume driven by non-information based trading.A further related literature examines the relationship between valuation and changes in dividends . These studies are concerned with market efficiency. Dividends are a straightforward concept: they are the payments made to equity holders by a company. Dividends may also be thought to include all cash payouts to equity including share repurchases, share liquidations, and cash dividends. Several studies have examined whether changes in dividends relate to changes in equity values; among these are Shiller (1981), LeRoy and Porter (1981), and Campbell and Shiller (1987). These tests generally find that stock market volatility can not be explained by subsequent changes in dividends. Larrain and Yogo (2008) take a slightly different look at equity volatility. Using a more aggregate sample they find that the majority of the change in asset prices (88%) is explained by cash flow growth while the remaining 12% is explained by changes in asset returns. They conclude that stock prices are not explained by dividend changes.The residual income method is conceptually more similar to FCF than to dividends. Residual income at its most basic equals the firm’s net income minus the cost of its capital. In the accounting literature, Ohlson’s (1991, 1995) formulation of a residual income model (RIM) is widely accepted and has been subjected to numerous tests. RIM begins with an accounting identity; namely that the change in book value equals the difference between net income and dividends. Ohlson then defines AE as the difference between net income and lagged book value. It is then a small step to observe that the present discounted value of expected future abnormal earnings plus the book value of equity equals stock price5. Jiang and Lee (2005) test both the RIM and the dividend discount model. Their test of equity volatility finds that RIM provides more and better information than dividends.3.METHODOLOGYUnlike previous studies, we rely on actual subsequent cash flows over a period of time rather than forecasts of cash flow made contemporaneously with EV. Previous researchers can be thought of as studying the consistency between contemporaneous EV determined in the market and forecasts of future cash flows. Our study does not have that focus. We instead are interested in the actual accuracy of market determined EVs. We compare EVs at a point in time to subsequent cash flows. The closer these values are the more accurate is the market in valuing companies based on their future 5See Jiang and Lee (2005), page 1466.cash flows.In order to estimate corporate value with FCFs, annual costs of capital must be estimated for each company. An alternative is to determine value using the capital cash flow (CCF) method. CCF yields the same present value as FCF6but only requires a single cost of capital estimate for each firm. This is the approach we follow.CCF is determined following Arzac (2005) as follows:CCF = net income + depreciation - capital expenditures –Δ working capital +Δ deferred taxes + net interestEstimated enterprise value (EEV) is calculated with the CCF estimates as follows:EEV =Σ(CCFi,j ) /(1+ kj )t TVj /(1+ kj )y , (i=1….y)where k is cost of capital, TV is terminal value, i is year, y is the final year with cash flow data and j represents firm. Terminal value is estimated according to the Gordon growth model. EEV estimates are compared with EV, the firm’s actual va lue as of the last trading day of the year. EV is calculated following Arzac (2005) as follows;EV = MarketCap + Debt −CashThe comparison between EV and EEV is a test of the accuracy of the market’s valuation process. Cases where EV exceeds (is less than) EEV are ones of overly optimistic (pessimistic) market valuation.4.DataWe begin with all firms with fiscal year end for which there is data for:• cash and short-term investments (data1),• total assets (data6),• current assets (data4),• current liabilities (data5),• short-term debt (data44),• long-term debt (data9),• notes payable (data206), and• deferred taxes (data74),• capital expenditures (data128)• sales (data12),• net income (data172)• depreciation (data14)• interest expense (data15)• interest income (data62)• common shares outstanding (data25),• year-end stock price (data199).This results in an initial sample of 131,518 firm-year observations. All firms are classified into their respective industries using historical SIC codes (data324).For each firm-year in the initial sample, we compute the following variables;EV = Market Cap (data199*data25) + Debt (data9 + data44 + data206)6See Arzac (2005) or Platt (2008).- Cash (data1)WC= Net current assets (data4 - data5) – cash (data1) + notes (data206)D= Long term (data9) + short term (data44 + data206)E= Share price (data199) * Number of shares (data25)(where EV is enterprise value, WC is working capital, D is debt, and E is equity) In addition we also compute lagged values for WC and deferred taxes (data74).Next, we obtain betas for firm-years from Compustat’s Research Insight. Betas are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to account for extreme outliers in the data.Interest rates based on the 10-year constant maturity series (I10YR) are obtain from the Federal Reserve Bank’s website. After merging with the interest rate data and the betas, the sample size reduces to 69,643 firm-year observations. The loss in observations is largely due to missing data on the betas or deletions due tonon-availability of lagged firm-year data.With the merged dataset, we compute the following variables, where LWC represents the lagged value of WC and Ldata74 is the lagged value for data74: CCF = net income (data172) + depreciation (data14) - capital expenditures(data128) + WC - LWC + deferred taxes (data74) - Ldata74 +interest paid (data15) –interest received (data62);βA = (1 / (1 + D/E))*βKU1 = I10YR + βA *ERP1KU2 = I10YR + βA *ERP2KU3 = I10YR + βA *ERP3;(where CCF is capital cash flow, βA is the asset beta, ERP is the equity risk premium, and KU1, KU2 and KU3 are estimates of the unlevered cost of capital for three different ERPs (ERP1 = 0.03;ERP2 = 0.05;ERP3 = 0.07)Results were essential identical regardless of the choice of ERP and so we report on those for ERP3. We then drop all observations with fiscal year greater than 2000 to allow a sufficient numbers of years of actual cash flow data to be in the dataset.From the summary files of the Institutional Brokers Estimate System (IBES) database, we extract median values of long-term growth in sales forecasts for all firms. The median value is based on all analyst estimates of long-term (5 to 10 years) growth forecasts made for each firm. Prior studies use this as a measure of the estimated growth rate for a firm’s cash flow. Many of the growth rate forecasts were extraordinarily large, and so we followed Sougiannis and Yaekura (2001) by using the growth rate in GDP instead of the IBES values.The final dataset consists of 27,027 firm-year observations with complete data on all variables of interest. Of this 2,820 firm-years are data for companies with five or more years of information. Firm’s whose last year of data had negative FCF were dropped from the sample since terminal value could not be calculated for them. This left us with 1,821 firms.Some companies in our sample have only five years of actual cash flow data; others have as many as 12 years of data. Recently it has been argued that the terminal value estimate dominates estimates of present value, see Platt and Demirkan (2008).To insure that EEV estimates are not unduly influenced by estimates of terminal value, EEV is calculated repeatedly for each company starting with using five years of data and then using more years,12 years, depending on how much data the company has available.5.CONCLUSIONWe began this paper saying that the most common explanation in finance textbooks for the value of the firm was that it equaled the present discounted value of future cash flows. Our results suggest that a better description for textbooks is that the value of the firm is related to but unequal to the present discounted value of future cash flows. In conjunction with Platt and Demirkan (2008) which finds that the TV is the principle part of EEV (i.e., approximately 92.3%) it would seem that the market values firms based on their near term (perhaps five years or fewer) subsequent cash flows. In fact, one dollar increase in future cash flows produces far less of an increase in a firm’s EV. Theoretically this conforms to a version of the Gordon (1962)two-stage growth model with a WACC based discount rate during the early period and a very high discount rate during the future period).Supporting evidence to our surprising finding appear in everyday stock market tables. For example, the following quote from of December 8, 2008 speaks precisely to our findings.“Cheapest Stocks Since 1995 Show Cash Exceeds Market(By Michael Tsang and Alexis Xydias)Dec. 8 (Bloomberg) –“Stocks have fallen so far that 2,267companies around the globe are offering profits to investors for free. That’s eight times as many as at t he end of the last bear market, when the shares rose 115 percent over the next year.Bank of New York Mellon Corp. in New York, Danieli SpA in Buttrio, Italy and Seoul-based Namyang Dairy Products Co. Hold more cash than the value of their stock and debt as the slowing world economy wiped out $32 trillion in capitalization this year.”The Bank of New York Mellon, for example, on that day had a market capitalization of $31.71 billion, debt of $35.83 billion, and cash of $75.50 billion. In this case, the market has an infinite discount rate on any and all cash flows.A possible explanation for our higher EEV estimate than actual EV is that our unlevered cost of capital (KU) estimate is too low and therefore associated with a too high TV estimate. However, we calculated three KU estimates, based on generally accepted equity risk premium (ERP) levels and then used the highest KU. It is true however, that there is a KU which equilibrates EV with our EEV.Another possible explanation is that forecasts relied upon the valuation process are inaccurate and that future cash flows far exceed what analysts had expected. We find this to be the least satisfactory explanation.REFERENCESArzac, Enrique, 2005, Valuation For Mergers, Buyouts, and Restructuring, John Wiley & Sons.Campbell, J., and Shiller, R., 1987, Cointegration and Tests of Present Value Models, Journal of Political Economy, 95(5):1062-88.Daines, R, 2001, Does Delaware law improve firm value?, Journal of Financial Economics, 62: 525-558Damodaran, A., 2006, Valuation Approaches and Metrics: A Survey of the Theory, Working Paper, Stern School of Business..Dontoh, A., Radhakrishnan, S., and Ronen, J., 2007, Is Stock Price a Good Measure for Assessing Value-Relevance of Earnings? An Empirical Test, Review of Managerial Science, 1(1):3-45.Fama Eugene F. and Kenneth R. French, 1992, The Cross- Section of Expected Stock Returns, The Journal of Finance,47: 427-465.Fama Eugene F. and Kenneth R. French., "Size and Book-to-Market Factors in Earnings and Returns", The Journal of Finance, 1995, No. 50. -pp. 131-155. Francis, J., Olsson, P., and Oswald, D, 2000, Comparing the Accuracy and Explainability of Dividend, Free Cash Flow, and Abnormal Earnings Equity Value Estimates, Journal of Accounting Research, 38(1).Gentry, J. Whitford, D., Sougiannis, T., and Aoki S., 2001, Do Accounting Earnings or Free Cash Flows Provide a Better Estimate of Capital Gain Rates of Return on Stocks?, Security Analysts Journal, 39(5):66-78.Hovakimian, A., T. Opler, and S. Titman, 2001, The debt-equity choice, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 36(1):1–24.Larrain, B. and Yogo, M., 2008, Does firm value move too much to be justified by subsequent changes in cash flow, Journal of Financial Economics, 87(1):200-26. LeRoy, S. F. and Porter, R. D., 1981, The Present-Value Relation: Tests Based on Implied Variance Bounds, Econometrica, 49(3):555-574.20Jiang, X. and Lee B., 2005, An Empirical Test of the Accounting-Based Residual Income Model and the Traditional Dividend Discount Model, Journal of Business, 78(4):1465–1504.Larrain, B., Yogo, M., 2008. Does Firm Value Move Too Much to be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Cash Flow?, Journal of Financial Economics, 87 (1),200–226.Liu, J., Nissim, D., and Thomas, J., 2002, Equity Valuation using Multiples, Journal of Accounting Research, 40(1): 135- 172.Myers, S. C., 1977, Determinants of corporate borrowing, Journal of Financial Economics, 5:147-175.Ohlson, J., 1991, The theory of value and earnings, an introduction to the Ball-Brown analysis, Contemporary Accounting Research, 8:1-19.Ohlson, J., 1995, Earnings, book values, and dividends in security valuation, Contemporary Accounting Research, 11: 661-87.Polk, C., Thompson, S. and Vuolteenaho, T., 2006, Cross-sectional forecasts of the equity premium, Journal of Financial Economics, 1:101-141.Platt, H, 2008, Cash Flow Contradistinctions, Commercial Lending Review, 23 (2):19-24Platt, H. and Demirkan, S., 2008, Perilous Forecasts: Implications of Reliance onTerminal Value, Working Paper, Northeastern University.Shiller, R.J., 1981, Do stock prices move too much to be justified by subsequent movements in dividends?, American Economic Review,71 (3): 421-36. Sougiannis, T., and Yaekura, T.,2001, The Accuracy and Bias of Equity Values Inferred from Analysts Earnings Forecasts, The Journal of Accounting, Auditing, and Finance, 16(4):331–362.Rubinstein D.,2003, Great Moments in Financial Economics: II. Modigliani-Miller Theorem, Journal of Investment Management. 1(2).Tsang M. and Xydias A., 2008 Cheapest Stocks Since 1995 Show CashExceeds Market, , December 8, 2008.。

中国公司治理(外文期刊翻译)

中国公司治理:现代视角Corporate governance in China: A modern perspective Corporate governance in China: A modern perspective☆Fuxiu Jiang, Kenneth A. Kim ⁎School of Business, Renmin University of China, 59 Zhongguancun Street, Haidian District, Beijing, China 100872近年来,许多使用中国金融数据的学术论文发表在领先的学术期刊上。

这一增长这并不奇怪,因为中国是一个转型经济大国,正在从计划经济转向市场经济,现在已经成为世界第二大经济体。

简单地说,中国是有趣和重要的。

然而,一些研究中国的缺点。

首先,考虑到大多数现代金融理论都起源于西方,尤其是美国,因此有很多研究中国的论文使用西方理论和概念来解释他们的实证发现。

2 . However, while it may sometimes be从西方的角度来看待中国的实证结果是恰当的,但在其他时候则不然。

其次,许多报纸似乎都是如此误解(或没有意识到)重要的监管问题;法律、金融和制度环境;和业务中国的风俗习惯。

第三,许多研究中国的论文,即使是最近发表的,现在已经过时了。

的中国过去20年的经济增长是爆炸式的。

在这段时间里,发生了许多变化地方,包括许多监管的变化和引入新的规则,影响公司治理在中国。

鉴于这些不足之处,本文的主要目的有两个:(一)对公司治理现状进行概述(二)指出和探讨公司治理在很大程度上是中国所特有的特点在本期特刊中,我们将为大家提供一个更新的中国公司治理观。

因此,我们也重要的是在适当的地方描述这些论文。

本文的其余部分如下。

在第二部分,我们提供了重要的制度背景资料的中国并讨论了中国公司治理的制度和监管环境。

在第三节,我们提供并讨论与公司治理相关的重要变量的汇总统计。

1Strategic entrepreneurship_ entrepreneurial strategies for wealth creation