The kinetics of cytokine production and CD25 expression by porcine lymphocyte subpopulations follow

(英文)生物外文文献

FIG. 3

SK-BR-3 cell,HER2过表达的乳腺癌细胞,STAT3可以通 过特定的细胞因子激活。HER2是重要的乳腺癌预后判 断因子,HER2阳性(过表达或扩增)的乳腺癌,其临 床特点和生物学行为有特殊表现,治疗模式也与其他 类型的乳腺癌有很大的区别。

36%

FIG. 4 LIF刺激

FIG. 1

15.5%

FIG. 2

GRN knockdown reduced the mRNA expression of these genes, similar to the effects of STAT3 knockdown

58%

染色质免疫共沉淀技术( chromatin immunoprecipitation assay, CHIP )

70%

Suggesting that some but not all phenotypes associated with GRN knockdown can be rescued by constitutively active STAT3.

FIG. 6

42.9%

13.5%

These findings indicate that in primary breast cancers, GRN expression specifically correlates with enhanced STAT3 transcriptional activity in the presence of tyrosinephosphorylated STAT3

• 皮尔森相关系数(Pearson correlation coefficient)也称皮尔森积矩 相关系数(Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient) ,是一种 线性相关系数。皮尔森相关系数是用来反映两个变量线性相关程 度的统计量。相关系数用r表示,其中n为样本量,分别为两个变 量的观测值和均值。r描述的是两个变量间线性相关强弱的程度。 r的绝对值越大表明相关性越强。

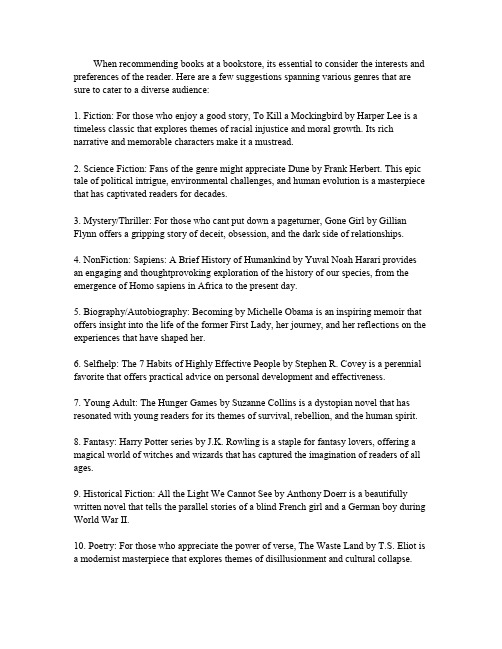

英语作文推荐书店的书

When recommending books at a bookstore, its essential to consider the interests and preferences of the reader. Here are a few suggestions spanning various genres that are sure to cater to a diverse audience:1. Fiction: For those who enjoy a good story, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee is a timeless classic that explores themes of racial injustice and moral growth. Its rich narrative and memorable characters make it a mustread.2. Science Fiction: Fans of the genre might appreciate Dune by Frank Herbert. This epic tale of political intrigue, environmental challenges, and human evolution is a masterpiece that has captivated readers for decades.3. Mystery/Thriller: For those who cant put down a pageturner, Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn offers a gripping story of deceit, obsession, and the dark side of relationships.4. NonFiction: Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari provides an engaging and thoughtprovoking exploration of the history of our species, from the emergence of Homo sapiens in Africa to the present day.5. Biography/Autobiography: Becoming by Michelle Obama is an inspiring memoir that offers insight into the life of the former First Lady, her journey, and her reflections on the experiences that have shaped her.6. Selfhelp: The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey is a perennial favorite that offers practical advice on personal development and effectiveness.7. Young Adult: The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins is a dystopian novel that has resonated with young readers for its themes of survival, rebellion, and the human spirit.8. Fantasy: Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling is a staple for fantasy lovers, offering a magical world of witches and wizards that has captured the imagination of readers of all ages.9. Historical Fiction: All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr is a beautifully written novel that tells the parallel stories of a blind French girl and a German boy during World War II.10. Poetry: For those who appreciate the power of verse, The Waste Land by T.S. Eliot isa modernist masterpiece that explores themes of disillusionment and cultural collapse.When recommending books, its also important to consider the readers current mood or what they hope to gain from their reading experience. Whether theyre looking for escapism, knowledge, or inspiration, theres a book out there to suit every need.。

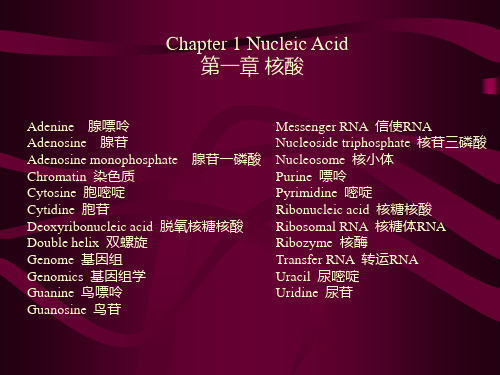

生化中英对照单词

Chapter 14 Protein Biosynthesis

第十四章 蛋白质的生物合成

Antibiotics 抗生素 Cap-site binding protein 帽子结合蛋白 Chloromycetin 氯霉素 Diphtheria toxin 白喉毒素 Eukaryote 真核生物 Genetic code 遗传密码 Insulin 胰岛素 Interferon 干扰素 Molecular chaperone 分子伴侣 Parathyroid hormone 甲状旁腺激素 Streptomycin 链霉素 Translational initiation complex 翻译起始复合物 Transpeptidase 转肽酶

丝氨酸/苏氨酸蛋白磷酸酶

Chapter 12 DNA Biosynthesis 第十二章 DNA生物合成

Bidirectional replication 双向复制 Endonuclease 内切核酸酶 Exonuclease 外切核酸酶 Gene expression 基因表达 Polymerases 聚合酶类 Primase 引发酶 Primosome 引发体 Proliferating cell nuclear antigen 增殖细胞核抗原 Recombination repairing 重组修复 Replicon 复制子 Reverse transcriptase 逆转录酶 Semiconservative replication 半保留复制 Single stranded DNA binding protein 单链DNA结合蛋白 Telomerase 端粒酶 Telomere 端粒 DNA topoisomerase DNA拓扑异构酶

Chapter 1 Nucleic Acid 第一章 核酸

CytokineELISA

BD Biosciences1-2900 Argentia RoadMississauga, ON • L5N 7X9 • CANADALocal Tel: (905) 542-8028 • Toll-Free Tel: (888) 259-0187Local Fax: (905) 542-9391 • Toll-Free Fax: (888) 229-9918Cytokine ELISAIntroductionDue to the amplifying potential of enzyme labels, immunoassays which utilize enzyme-conjugated antibodies have become increasingly popular because of their high specificity and sensitivity.1 In 1971, Engvall and Perlmann2 coined the term “enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay” which is perhaps better known by the acronym, “ELISA”, to describe an enzyme-based immunoassay method which is useful for measuring antigen concentrations.Cytokine sandwich ELISA are sensitive enzyme immunoassays that can specifically detect and quantitate the concentration of soluble cytokine and chemokine proteins. The basic cytokine sandwich ELISA method makes use of highly-purified anti-cytokine antibodies (capture antibodies) which are noncovalently adsorbed (“coated” – primarily as a result of hydrophobic interactions) onto plastic microwell plates. After plate washings, the immobilized antibodies serve to specifically capture soluble cytokine proteins present in samples which were applied to the plate. After washing away unbound material, the captured cytokine proteins are detected by biotin-conjugated anti-cytokine antibodies (detection antibodies) followed by an enzyme-labeled avidin or streptavidin stage. Following the addition of a chromogenic substrate-containing solution, the level of coloured product generated by the bound, enzyme-linked detection reagents can be conveniently measured spectrophotometrically using an ELISA-plate reader at an appropriate optical density (OD). Data storage and reanalysis are greatly simplified when the plate reader is connected to a computer.By including serial dilutions of a standard cytokine protein solution of known concentration, the sandwich ELISA supports the development of standard curves. Standard curves (aka“calibration curves”) are generally plotted as the standard cytokine protein concentration (typically ng or pg of cytokine/ml) versus the corresponding mean OD value of replicates. The concentrations of the putative cytokine-containing samples can be interpolated from the standard curve. This process is made easier by using an ELISA computer software program.3 Generally, it is useful to perform a dilution series of the unknown samples to be assured that the OD will fall within the linear portion of the standard curve. Depending on the nature of the ELISA reagents used, investigators may choose to apply different curve fit analysis to their data, including either linear-log, log-log, or four-parameter transformations.1,4,5Although opinions differ, one convention for determining the ELISA sensitivity isto choose the lowest cytokine concentration that gives a signal which is at leasttwo or three standard deviations above the mean background signal value.6,7Because of the enzyme-mediated amplification of the detection antibody signal,the sandwich ELISA can measure physiologically relevant (i.e., > 5-10 pg/ml)concentrations of specific cytokine and chemokine proteins, which are present inmixed cytokine milieus, e.g., from stimulated lymphocyte culture supernatants.Although many different types of enzymes have been used, horseradishperoxidase (HRP) and alkaline phosphatase (AKP) are the enzymes that are oftenemployed in ELISA methods.1,8Application NotesCytokine sandwich ELISA are exquisitely specific because antibodies directedagainst two or more distinct epitopes are required.9 Therefore, sandwich ELISAcan discriminate between cytokines that can have overlapping biologicalfunctions which are not resolvable in a bioassay. Although cytokine sandwichELISA are very useful for cytokine detection and measurement, several limitationsfor the interpretation of ELISA data must be mentioned.9 For example, becausetest samples often come from tissue culture supernatants or biological fluidswhich are conditioned with cytokines produced by mixed cell populations, theELISA data does not provide direct information on the identities and frequenciesof individual cytokine producing cells. Techniques such as the"Immunofluorescent Staining of Intracellular Cytokines" are required for thislatter type of analysis.Several key issues need to be considered when designing experiments that involvecytokine and chemokine protein measurements using sandwich ELISA. Forinstance, it is well known that cytokine production by stimulated cell populationsis transient and that the kinetics of expression of different cytokine genes canvary. For these reasons, it may therefore be necessary to collect test samples atseveral time points to better characterize cytokine-production by an experimentalanimal or by a cultured cell population. As an example, in the case of stimulated mouse CD4+ T cell populations, the levels of IL-2 produced are detected relativelyearly after stimulation whereas the accumulated levels of IL-5 protein rise later inculture.10It should also be noted that cytokine production can be stimulus- and cell subset-dependent. For example, in the case of T cells, it is well known that naive T cellshave a limited cytokine production capability (i.e., primarily can produce IL-2)whereas memory T cells can produce high levels and different types of cytokineproteins including IFN-g and IL-4, as well as IL-2. 11,12 Moreover, T cell subsetshave been found to produce cytokines differentially in response to differentstimuli.12,13 Another consideration is that cytokine protein concentrations,measured at any one time point, may reflect the concurrent processes of cytokinesecretion, cytokine uptake by cells and cytokine protein degradation. Because ofthese processes, the measured level of cytokine protein may significantlyunderestimate the actual cytokine-producing potential of cells. In these cases, itmay be necessary to use complementary techniques such as multi-proberibonuclease protection assay analysis or immunofluorescent intracellular cytokinestaining with flow cytometric analysis to gauge the relative levels of cytokineexpression by various test cell populations.The levels of immunoreactive cytokine proteins detected by ELISA may or may notcorrelate directly with the levels of bioactive cytokine protein.9,14 For example, anELISA may utilize anti-cytokine antibodies that cannot discriminate between theprecursor (inactive) and mature (bioactive) forms of a cytokine protein such as TGFb1. Moreover, an ELISA may detect partially-degraded cytokine proteins which have retained their immunoreactive properties (i.e., at least two recognizable epitopes) but may have lost their bioactivity. In conclusion, cytokine sandwich ELISA are useful indicators of the presence and levels of cytokine and chemokine proteins but they do not actually provide information concerning the biological potency of the detected proteins.With these caveats in mind, one can infer from the presence and amount of cytokine protein detected, the potential mechanisms by which particular effector cell populations perform their functions. Moreover, sandwich ELISAs can detect soluble cytokine receptors which may be important for cytokine regulation. Soluble cytokine receptors may act as antagonists or as carrier proteins in vivo and may serve as disease markers in in vitro tests.15 It should be noted that in addition to providing a rich source of information for clinical and basic science research studies, sandwich ELISA for measuring cytokines and their receptors have become increasingly important as diagnostic tools and for monitoring therapeutic regimens,16 e.g., biological response modification regimens utilizing recombinant cytokine proteins. In the latter cases, highly optimized sandwich ELISA kits designed to minimize interference or nonspecific reactivities presented by patient samples is highly desirable.ELISA Protocol General ProcedureCapture antibody:1.Dilute the purified anti-cytokine capture antibody to 1-4 µg/ml a in BindingSolution. Add 50 µl of diluted antibody to the wells of an enhanced protein-binding ELISA plate (e.g.,Nunc Maxisorb; cat. no. 446469).2.Seal plate to prevent evaporation. Incubate overnight at 4°C.Blocking:3.Bring the plate to RT, remove the capture antibody solution, and block non-specific binding by adding 200 µl of Blocking Buffer per well.4.Seal plate and incubate at RT for 1-2 hr.5.Wash ≥3 times d with PBS/Tween ® .Standards and Samples:6.Add standards b,c and samples (diluted in Blocking Buffer/Tween ®h at 100 µl perwell.7.Seal the plate and incubate it for 2-4 hr at RT or overnight at 4°C.e8.Wash ≥4 times d with PBS/Tween® .Detection antibody:9.Dilute the biotinylated anti-cytokine detection antibody to 0.5-2 µg/ml inBlocking Buffer/Tween®.h Add 100 µl of diluted antibody to each well.10.Seal the plate and incubate it for 1 hr at RT.11.Wash ≥4 times d with PBS/Tween® .Avidin-Horseradish Peroxidase (Av-HRP):12. Dilute the Av-HRP conjugate (cat. no. 13007E) or other enzyme conjugate c,f toits pre-titered optimal concen-tration in Blocking Buffer/Tween ®. Add 100 µl per well.13. Seal the plate and incubate it at RT for 30 min.14. Wash ≥5 times d with PBS/Tween ® .Substrate:15. Thaw ABTS Substrate Solution c,f within 20 min of use. Add 100 µl of 3% H2O2per 11 ml of substrate and vor-tex. Immediately dispense 100 µl into each well. Incubate at RT (5-80 min) for colour development. The colour reaction can be stopped by adding 50 µl of Stopping Solution.16. Read the optical density (OD) for each well with a microplate reader set to 405nm.gSOLUTIONS:§ Binding Solution: 0.1 M Na 2HPO 4 , adjust pH to 9.0 with 0.1 M NaH 2PO 4.§ PBS Solution: 80.0 g NaCl, 11.6 g Na 2HPO 4 , 2.0 g KH2PO4 , 2.0 g KCl; q.s. to 10L; pH to 7.0.§ PBS/Tween ®: 0.5 ml of Tween ® -20 in 1 L PBS.§ Blocking Buffer: Prepare 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10% newborn calf serum (NBCS ) or 1% BSA (immunoassay grade) in PBS. The Blocking Buffershould be filtered to remove particulates before use.§ Blocking Buffer/Tween ®: Add 0.5 ml Tween ® -20 to 1 L Blocking Buffer.§ ABTS Substrate Solution: Add 150 mg 2,2’-Azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (e.g., Sigma, cat. no. A-1888) to 500 ml of 0.1 M anhydrous citricacid (e.g., Fisher; cat. no. A-940) in dd H 20; pH to 4.35 with NaOH. Aliquot 11ml per vial and store at -20°C. Add 100 µl 3% H 2O 2 prior to use.§ 3% H 2O 2 Solution: Add 10 ml of 30% H 2O 2 to 90 ml of H 2O 2. Protect from prolonged exposure to light.§ Stopping Solution: (20% SDS/50% DMF): Add 50 ml of dimethylformamide (DMF) (Pierce, cat. no. 20672) to 50 ml dd H 20, then add 20.0 g sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) (CMS, cat. no. 424-749).Cytokine ELISA Helpful Hintsa. To determine the optimal signal and lowest background for the ELISA, thecapture antibody (1-4 µg/ml) and detection antibody (0.25-2 µg/ml should be titrated against each other in a preliminary experiment. An appropriate range of serial dilutions for the cytokine standard should be included. A suggested range is generally provided on the Technical Data Sheet (TDS) for ELISAreagents. Generally, use of the capture antibody at 2 µg/ml and the detecting antibody at 1 µg/ml provides strong ELISA signals with low back-ground.b. CYTOKINE STANDARD HANDLING: Please read the TDS for each recombinantcytokine carefully. Handling instructions are lot-specific. For maximumrecovery of cytokine, the vial of cytokine should be quick-spun beforeopening. Lyophilized cytokines should be reconstituted as indicated in the lot-specific TDS. BD Biosciences recommends keeping the cytokine solution in a concentrated form (e.g., ≥1 µg/ml) and in the presence of a protein carrier for long-term storage.c. The linear region of cytokine ELISA standard curves are generally obtainable ina series of eight two-fold dilutions of the cytokine standard, from 2000 pg/ml to 15 pg/ml. To increase sensitivity beyond that obtainable with the standardELISA protocol, amplification kits, tertiary reagents, or alternateenzyme/substrate systems can be used.d.High backgrounds in blank wells (i.e., OD > 0.20) or poor consistency ofreplicates can be overcome by increasing the stringency of washes andoptimizing the concentration of capture and detection antibodies. Forexample, during washes, the wells can be soaked for ~ 1 minute intervals.Moreover, lower concentrations of detecting antibody or more washes after the detecting antibody stage can reduce background.e.For optimal sensitivity, overnight incubation of standards and samplesis recommended.f.If using peroxidase as the enzyme for colour development, avoid sodium azidein wash buffers and diluents, as this is an inhibitor of peroxidase activity.g.If no signal is observed, check the following: a) verify that appropriateantibody clones were used; b) check the activity of the enzyme/substratesystem: e.g.,coat 1 µg/ml of biotinylated detecting antibody in several wells in binding buffer for a few hr. After blocking, wash several times then proceed with the cytokine ELISA protocol from Step 13. If the enzyme/substrate system is active, then a strong signal should be seen; c) verify the activity of cytokine standard or try a new sample of standard.h.When measuring cytokines in complex fluids, such as serum, samplediluents which include irrelevant Ig are suggested.17References:1.Crowther, J. R. 1995. ELISA. Theory and Practice. Methods Mol. Biol. 42:1-223.2.Engvall, E., and P. Perlmann. 1971. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Quantitativeassay of immunoglobulin G. I mmunochem.8:871-874.3.Davies, C. 1994. Principles. In The Immunoassay Handbook. D. Wild, ed. Stockton Press, NewYork, p. 3-47.4.Rogers, R. P. C. 1984. Data Analysis and Quality Control of Assays: A Practical Primer. InPractical Immuno Assay. W. R. Butt, ed. Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York.5.Davies, C. 1994. Calibration curve fitting. In The Immunoassay Handbook. D. Wild, ed, NewYork, p. 118-123.6.Davies, C. 1994. Concepts. In The Immunoassay Handbook. D. Wild, ed. Stockton Press, NewYork, p. 83-115.7.Pathak, S. S., A. van Oudenaren, and H. F. J. Savelkoul. 1997. Quantification ofimmunoglobulin concentration by ELISA. In Immunology Methods Manual, vol. 2. I. Lefkovitz, ed. Academic Press Inc., San Diego, p. 1056-1075.8.Wild, D., and C. Davies. 1994. Components. In The Immunoassay Handbook. D. Wild, ed. Press,New York, p. 49-82.9.Mosmann, T. R., and T. A. T. Fong. 1989. Specific assays for cytokine production by T cells. J.Immunol. Meth.116:151-158.10.Hobbs, M. V., W. O. Weigle, D. J. Noonan, B. E. Torbett, R. J. McEvilly, R. J. Koch, G. J. Cardenas,and D. N. Ernst. 1993. Patterns of cytokine gene expression by CD4 + T cells from young and old mice. J. Immunol. 150:3602-3614.11.Ehlers, S., and K. A. Smith. 1991. Differentiation of T cell lymphokine gene expression: The invitro acquisition of T cell memory. J. Exp. Med.173:25-36.12.Cerottini, J.C., and H. R. MacDonald. 1989. The cellular basis of T-cell memory. Annu. Rev.Immunol. 7:77-89.13.Farber, D. L., M. Luqman, O. Acuto, and K. Bottomly. 1995. Control of memory CD4 T cellactivation: MHC class II molecules on APCs and CD4 ligation inhibit memory but not naive CD4 T cells. Immunity 2:249-259.14.Carter, L. L., and S. L. Swain. 1997. Single cell analyses of cytokine production. Curr. Opin.Immunol.9:177-182.15.Callard, R. E., and A. J. H. Gearing. 1994. Cytokine receptor superfamilies. In The Cytokine FactsBook. Academic Press Inc., San Diego, p. 18-27.16.Rossio, J. L. 1997. Cytokines and immune cell products. In Weir's Handbook of ExperimentalImmunology. Fifth Edition. D. M. Weir, L. A. Herzenberg, L. A. Herzenberg, and C. Blackwell, eds. Blackwell Science, Inc., Cambridge, MA.17.Abrams, J.S. 1995. Immunoenzymetric assay of mouse and human cytokines using NIP-labeledanti-cytokine antibodies. Current Protocols in Immunology (J. Coligan, A. Kruisbeek, D.Margulies, E. Shevach, W. Strober, eds). John Wiley and Sons, New York. Unit 6.20.。

ELISPOT技术原理与应用

经过预孵育,斑点更分散,清晰 可以除去贴壁的巨噬细胞,从而减少小斑点的影响;

粒细胞的影响(虫啃)也可以大大减轻 某些细胞因子通常很难用直接法得到结果,比如颗粒

267 SFC

我们自己的试验结果:PHA/10,000 Hu-PBMC

上:5%小牛血清(杭州)下:无血清培养基U-cytech)

DAKEWE BIOTECH COMPANY Ltd.

达科为生物

7. 刺激物选择

非特异性刺激物

有丝分裂原 ConA,PMA,PHA,Ionomycin

特异性刺激物

10~40min;

8

8. 获得斑点,计数。

DAKEWE BIOTECH COMPANY Ltd.

达科为生物

2. ELISPOT技术要点

细胞培养和培养前阶段无菌操作,避免污染 细胞在ELISPOT板上孵育时要避免震动,包括开关

CO2孵箱 洗涤要充分,尤其是裂解细胞之后的洗涤 洗涤时,枪头不能接触到膜,从孔中移出液体采用倾倒

DAKEWE BIOTECH COMPANY Ltd.

达科为生物

8.建立阳性对照

非特异性刺激阳性对照:

ConA

伴刀豆蛋白A

PHA

植物血球凝集素

Ionomycin 伊诺霉素

PMA

14烷酰佛波乙酯

0.4-1.0ug/well 0.3-1.0ug/well 50-100ng/well 5.0-10ng/well

844 492

355

192

40万 20万 10万

5万

人PBMC/CEF刺激 U-cytech无血清培养基

DAKEWE BIOTECH COMPANY Ltd.

CXC趋化因子配体16与冠心病关系的研究进展

・246・虫国塞旦匡蕴!!!Q生!旦箜!鲞筮!塑£!i塑№丛鲤:坠垫!Q:!堂:§,丛!:2CXC趋化因子配体16与冠心病关系的研究进展陈静文严激在冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病的发病机制学说中,除了已被人们接受的脂质浸润学说和损伤反应学说外,炎症反应的作用也逐渐被人们所认识。

炎症反应贯穿于粥样硬化斑块的形成、演变以及破裂的整个病理过程。

炎症细胞与血管内环境中的细胞、细胞因子、炎症介质等的相互作用极其复杂,而趋化因子则是联系炎症与动脉粥样硬化(atherosclerosis,AS)发生的枢纽。

CXC趋化因子配体16(cxCLl6/SR-PSOX)是一种具有结合磷脂酰丝氨酸和氧化型低密度脂蛋白(OX-LDL)作用的趋化因子,同时也是清道夫受体家族成员之一。

近年来,国内外学者在其与冠心病关系方面研究甚多,争议也较多,现就其目前的研究进展作一综述。

lCXCLl6概述血管壁上的几乎所有细胞如平滑肌细胞、内皮细胞和巨噬细胞都有表达CXCLl6,尤其是在已存在AS斑块内膜上的脂质负荷的巨噬细胞中表达极为丰富…。

CXC趋化因子受体6(CXCR6)是其唯一受体,主要在CD4+T细胞、CD8+T细胞、B细胞、NKT细胞、树突状细胞中表达口1。

CXCLl6在人体内有两种存在形式,即跨膜结合型和分泌型。

不同形式的CXCLl6生物学作用不同而又相互关联:以分泌型存在时,主要作为CD8+T细胞的趋化诱导剂;以跨膜结合型存在时,通过它的趋化因子活性区参与活化T淋巴细胞与血管内皮细胞之问的识别和粘附,促进大量的特异性炎症细胞浸润。

金属蛋白水解酶10(adisintegrinandmetalloprotease10,ADAM一10)是两种形式转化的关键因素,跨膜结合型CXCLl6被ADAM-10水解后脱落形成分泌型CXCLl6,分布于外周血中。

而作为清道夫受体,发挥着从血管壁清除OX-LDL等有害物质的作用。

CXCLl6作为一种具有多种功能的蛋白,其在冠心病炎症反应中具有不可忽视的地位。

LPS刺激TNFα释放的时间曲线

174,

No.

1, 1991

BIOCHEMICAL

AND

BIOPHYSICAL

RESEARCH

COMMUNICATIONS Pages 18-24

15, 1991

KINETICS OF TNF, IL-6, AND IL-8 GENE EXPRESSION IN LPS-STIMULATED HUMAN WHOLE BLOOD L.E. DeForge and D.G. Remick Department of Pathology, University

Received November 20, 1990

of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-0602

While the production of tumor necrosisfactor (TNF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in septic shock and other inflammatory states is well established,the role of interleukin-8 (n-8), a recently describedneutrophil chemoattractantand activator, hasyet to be fully elucidated. Using lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated human whole blood as an ex viva model of sepsis,the kinetics of messenger RNA (mRNA) up-regulation and protein releaseof these cytokines were examined. Two waves of cytokine gene activation were documented. TNF and IL-6 were induced in the first wave with mRNA levels peaking between 2-4 hours and then rapidly declining. TNF and IL-6 protein peaked at 4-6 hours and then stabilized. IL-8 mRNA and protein were induced in the first wave, reacheda plateau between6-12 hours, and rose again in a second wave which continued to escalate until the end of the 24 hour study. These data demonstratethe complex patterns of cytokine gene expression and suggestthat production of early mediatorsmay augment continued expressionof IL-8 to recruit and retain neutrophils at a site of inflammation. 0 1991 Academic FJre.55, Inc. The morbidity and mortality associated with septic shock are primarily attributable to the endogenousmediators released during the host’s responseto bacterial LPS (1). One such

酵母聚糖等 TLR2-MyD88 信号通路

The TLR2-MyD88-NOD2-RIPK2signalling axis regulates a balanced pro-inflammatory and IL-10-mediatedanti-inflammatory cytokine response to Gram-positive cell wallsLilian O.Moreira,1,2‡Karim C.El Kasmi,1†‡Amber M.Smith,1,2David Finkelstein,3Sophie Fillon,1†Yun-Gi Kim,4Gabriel Núñez,4Elaine Tuomanen 1and Peter J.Murray 1,2*1Department of Infectious Diseases,St.Jude Children’s Research Hospital,332North Lauderdale,Memphis,TN 38105,USA.2Department of Immunology,St.Jude Children’sResearch Hospital,332North Lauderdale,Memphis,TN 38105,USA.3Hartwell Center for Biotechnology and Bioinformatics,St.Jude Children’s Research Hospital,332North Lauderdale,Memphis,TN 38105,USA.4Department of Pathology,University of Michigan,1500East Medical Center Drive,Ann Arbor,MI 48109,USA.SummarySystemic infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae is associated with a vigorous pro-inflammatory response to structurally complex cell wall fragments (PnCW)that are shed during cell growth and antibiotic-induced autolysis.Consistent with previ-ous studies,inflammatory cytokine production induced by PnCW was dependent on TLR2but independent of NOD2,a cytoplasmic NLR protein.However,in parallel with the pro-inflammatory response,we found that PnCW also induced pro-digious secretion of anti-inflammatory IL-10from macrophages.This response was dependent on TLR2,but also involved NOD2as absence of NOD2-reduced IL-10secretion in response to cell wall and translated into diminished downstream effects on IL-10-regulated target gene expression.PnCW-mediated production of IL-10via TLR2required RIPK2a kinase required for NOD2function,and MyD88but differed from that known for zymosan in that ERK pathway activation was not detected.As mutations inNOD2are linked to aberrant immune responses,the temporal and quantitative effects of activation of the TLR2-NOD2-RIPK2pathway on IL-10secretion may affect the balance between pro-and anti-inflammatory responses to Gram-positive bacteria.IntroductionIL-10secretion from T cells,macrophages and dendritic cells is an essential regulatory mechanism to temper excessive inflammatory responses (Murray,2006).Mice lacking IL-10are extremely sensitive to a wide variety of pro-inflammatory stimuli including LPS,and systemic infections with bacteria and parasites that provoke a strong inflammatory response (Murray,2006).In all cases,IL-10is required to restrain the inflammatory response and protect the host against the damaging effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines.Systemic infection with S.pneumoniae provokes a generalized inflammatory response linked with devastating neurological sequelae and a fatality rate of ~15%(Tuomanen et al .,1995).Administration of purified pneumococcal cell wall (PnCW)recapitulates the majority of the inflammatory responses observed in systemic S.pneumoniae infection,suggest-ing that the pro-inflammatory properties of PnCW are a primary driver of inflammatory pathology (Moreillon and Majcherczyk,2003;Fillon et al.,2006;Orihuela et al .,2006).Because PnCW is mainly composed of peptidogly-can,teichoic acid,cell wall linked proteins and lipoteichoic acids,TLR2is considered especially important in the process of PnCW detection by macrophages and den-dritic cells that are then stimulated to produce inflam-matory cytokines (Yoshimura et al .,1999).IL-10can modulate PnCW induced inflammation (Orihuela et al .,2006),but the mechanism leading to IL-10production is entirely unclear.Modulation of inflammation has been suggested to involve NOD2,a cytoplasmic protein of the larger NLR family (Inohara and Nunez,2003;Inohara et al .,2005;Murray,2005;Strober et al .,2006;Kanneganti et al .,2007).For example,single nucleotide polymorphisms in NOD2have been observed at an increased frequency in Crohn’s disease (Lesage et al .,2002).However,severalReceived 2May,2008;revised 31May,2008;accepted 2June,2008.*For correspondence.E-mail peter.murray@;Tel.(+1)9014953219;Fax (+1)9014953099.†Present address:University of Colorado Health Sciences Center,Denver,CO,USA;‡Contributed equally to this work.Cellular Microbiology (2008)10(10),2067–2077doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01189.xFirst published online 8July 2008©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation ©2008Blackwell Publishing Ltdloss-of-function mice in the Nod2gene do not have gut immunopathology when maintained under normal condi-tions(Pauleau and Murray,2003;Kobayashi et al.,2005; Maeda et al.,2005;Mariathasan et al.,2006;Barreau et al.,2007).These data are consistent with the fact that some people have mutations in one or both NOD2 alleles but have no clinical inflammatory bowel disease (Hugot et al.,2007).Thus NOD2likely plays a role in more complex pathways modulating pro-inflammatory responses(Strober et al.,2007;Xavier and Podolsky, 2007).NOD2-deficient mice,their immune cells and human cells bearing predicted loss-of-function NOD2alleles,are non-responsive to muramyl dipeptide(MDP),a‘minimal’component of bacterial peptidoglycan able to induce pro-inflammatory responses.A second pathway of MDP sensing appears to be involved in IL-1b processing and is mediated by NLR family members Cryopyrin(NLRP3)and Nalp1(NLRP1)(Faustin et al.,2007;Pan et al.,2007; Marina-Garcia et al.,2008).At this stage it is unclear whether human cells bearing two copies of the NOD2 frame-shift mutation are completely non-responsive to MDP because the truncated mutant protein should still be pared with other bacterial components such as LPS,peptidoglycan or CpG DNA,MDP is a very weak agonist of myeloid-derived cells,especially when considered by molar comparison.However,MDP syner-gizes with other TLR agonists to stimulate cytokine, chemokine and nitric oxide production.This effect is the basis of variants of the‘MDP synergy’assay,a common ‘readout’of NOD2function.In contrast to the lack of MDP responsiveness,macrophages from all NOD2-deficient mice have been generally reported to have‘normal’responses to highly defined TLR agonists.At present,the specific roles of MDP,the origin of MDP in mammalian infection systems and the link between NOD2and MDP remain unresolved.In the studies described here,we observed that TLR2 and NOD2were together responsible for IL-10production when macrophages were exposed to PnCW.By contrast, inflammatory cytokine production in response to PnCW was TLR2dependent and NOD2-independent.Our studies reveal an unexpected pathway of signal integra-tion in response to a complex microbial product that stimulates multiple signalling pathways in macrophages.ResultsWhen S.pneumoniae grow in vivo,cell wall components are released into the host environment by several pro-cesses:cell wall turnover that occurs during normal growth,antibiotics that induce autolysis,and subpopula-tions that undergo spontaneous autolysis as a mecha-nism of interbacterial gene transfer.The latter process lead in part to the discovery of DNA as the source of genetic information.Released cell wall fragments stimu-late a complex pathway of local and systemic inflamma-tory responses including neuronal damage and memory loss(Tuomanen et al.,1995).Because cell wall fragments derived from yeast(zymosan)induce robust IL-10secre-tion from myeloid-derived cells(Dillon et al.,2004;2006; Rogers et al.,2005;Slack et al.,2007),we tested if puri-fied PnCW(Fillon et al.,2006)also induced IL-10produc-tion from bone marrow-derived macrophages(BMDMs). PnCW induced previously unsuspected high amounts of IL-10(Fig.1).As purified PnCW is composed primarily of peptidoglycan,a TLR2agonist,this response was predict-ably TLR2dependent(Fig.1).In parallel experiments we also observed that IL-10and IL-10mRNA production in response to PnCW was also dependent on NOD2 (Figs1B,D and E).The reduction in IL-10production from PnCW-stimulated NOD-deficient macrophages was not to the same extent as Tlr2-/-BMDMs but nevertheless highly reproducible.We also observed that BMDMs derived from Tlr2-/-;Nod2-/-mice secreted undetectable IL-10,demonstrating that TLR2and NOD2might function in the same or related pathways for IL-10production (Figs1B,D and E).By contrast,IL-10production in response to LPS was indistinguishable in Tlr2-/-,Nod2-/-or Tlr2-/-;Nod2-/-cells(Fig.1C).We tested if NOD2was required for IL-10production in response to Pam3CSK4,a synthetic lipid that signals via exclusively TLR2.We observed that Nod2-/-BMDMs produced IL-10in response to Pam3CSK4similar to control cells(data not shown).In contrast,Pam3CSK4did not induce IL-10in Tlr2-/-or Tlr2-/-;Nod2-/-cells as expected(data not shown).NOD2was therefore not required for the‘canoni-cal’TLR2activation pathway stimulated by Pam3CSK4 but was important to the physiological PnCW stimulus. Because PnCW is a complex macromolecule,we tested its cellular fate after exposure to BMDMs.We visu-alized PnCW fragments in macrophages through the use of FITC-labelled PnCW(Fig.1F and G).Macroph-ages consumed all the PnCW over a period of~24h and thereafter,the PnCW remained internalized and appar-ently unchanged over7days when the experiments were paring these data with the kinetics of cytokine secretion,we suspect that macrophages are stimulated with early,external contact with PnCW.By contrast,phagocytosed PnCW appeared to persist within macrophages.Further experiments will be necessary to determine if macrophages can generate MDP from the PnCW and any signalling connections between NOD2 and in-dwelling PnCW.We next asked how broadly NOD2influenced overall macrophage transcriptional responses to PnCW.We per-formed transcriptome analysis of BMDMs derived from background-matched C57BL/6Nod2+/+or Nod2-/-mice2068L.O.Moreira et al.©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Cellular Microbiology,10,2067–2077stimulated for 0,1or 4h with PnCW at a concentration and conditions identical to that used for the experiments in Fig.1.We analysed the data first by principal component analysis (data not shown)and then by ordering gene expression according to degree of induction relative to the untreated (0h)time point data (Table 1).We observed that the absence of NOD2had limited effects on the overall inflammatory response to PnCW (Table 1,Fig.2A)consistent with the notion that other receptors,especially TLR2,mediate a strong cellular activation by PnCW.Of the mRNAs whose expression was altered,we noted that IL-10mRNA expression was reduced in NOD2-deficient cells relative to controls consistent with the ELISA and mRNA data shown in Fig.1.Because IL-10has essential autocrine-paracrine inhibitory effects on activated mac-rophages,we next asked if a panel of known downstream target genes of IL-10signalling (Lang et al .,2002;El Kasmi et al .,2007)were affected by the reduction of IL-10after PnCW stimulation of NOD2-deficient macrophages.We observed that expression of multiple IL-10target genes was lowered relative to controls in NOD2-deficient macrophages at 4h post stimulation (Fig.2B).This is consistent with the data that PnCW stimulates IL-10production in a NOD2-dependent way that leads,in part,to autocrine-paracrine downstream effects on IL-10-responsive gene expression.By contrast to the requirement for both TLR2and NOD2in IL-10production,we observed that alltestedbined signals from TLR2and NOD2are required for PnCW-induced IL-10production.A.Schematic representation of the composition of PnCW obtained by biochemical purification from whole lysed pneumococci.The upper part of the figure is cartoon of the bacteria cell membrane and wall indicating that the wall composed primarily of peptidoglycan,to which multiple proteins,lipopeptides and lipids are tethered,surrounds the cell membrane of pneumococci.Following purification,PnCW is predominantly peptidoglycan and teichoic acids.This fraction is particulate is nature,analogous to zymosan fractions from yeast cell walls.B.IL-10production from BMDMs stimulated with PnCW measured over time by ELISA.Results are combined from independent experiments (n =7).C.IL-10production from LPS stimulation of BMDMs from the same genotypes used in (B).D.Northern blotting analysis of IL-10mRNA over time (h)following PnCW stimulation of BMDMs from the indicated genotypes.Data from Nod2-/-;Tlr2-/-BMDMs were obtained from a different part of the gel as shown the separation from the other part of the gel.E.qRT-PCR analysis of IL-10mRNA production following PnCW stimulation.Data points are averages of duplicate samples.Data are representative of three independent experiments.F.Confocal microscopy to follow the fate of PnCW after contact with BMDMs.FITC-labelled PnCW was added to C57BL/6BMDMs andfollowed over time.Representative images at times 0,5,24and 48h are shown.At each time,cultures were fixed and labelled with phalloidin to visualize actin.Note that the FITC signal is not visible until sufficient PnCW particle have been phagocytosed and concentrated inside macrophages (24h).All images were collected using a 10¥objective,except the 48h time point (20¥).G.Higher power image of PnCW inside BMDMs at 48h (40¥objective).The TLR2-MyD88-NOD2-RIPK2signalling axis 2069©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation ©2008Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Cellular Microbiology ,10,2067–2077pro-inflammatory genes induced by PnCW were depen-dent on TLR2(Fig.3),but independent of NOD2as shown by the microarray data(Table1).These results are consistent with the notion that TLR2is the primary pathway by which macrophages detect PnCW and that NOD2plays a downstream role infine tuning the signal-ling response,in this case by regulating IL-10production. NOD2has been reported to form heterotypic com-plexes with another CARD domain protein,RIPK2(Kobayashi et al.,2002;Park et al.,2007;Hasegawa et al.,2008).Like NOD2-deficient cells,macrophages lacking RIPK2cannot respond to MDP,suggesting that NOD2and RIPK2function in the same pathway for MDP responsiveness(Park et al.,2007).Furthermore,RIPK2 is also required for NOD1function(which does not‘sense’MDP),suggesting that RIPK2is genetically and biochemi-cally linked to both NOD1and NOD2activity(Park et al., 2007).We therefore used macrophages derived from twoTable1.Gene expression increased by PnCW treatment.Gene Rank(WT)Fold(4h)Rank(Nod2-/-)Fold(4h)P(time)P(genotype) Gm19601222.141205.56 1.41E-130.5314Irg12124.622145.62 4.32E-110.8515Cxcl13102.854111.82 2.17E-110.3880Tnf482.043124.60 1.02E-110.8967Cxcl1578.065102.79 4.75E-110.3036Ccl3677.61676.38 4.39E-110.9913Saa3776.27854.01 2.37E-140.1997Ptgs2857.721629.27 4.13E-090.9574Ccl4954.471432.23 3.61E-120.6201Il1b1051.931532.008.30E-070.7485Gpr109a1151.731037.097.80E-140.2307Slc7a111251.721924.34 4.11E-140.6030Ptgs21351.634616.038.02E-080.1154Il1a1445.045015.37 6.39E-070.7571Il61544.031135.24 1.02E-060.3773Socs31643.811332.65 2.46E-110.2271Socs31740.921726.16 1.79E-110.4451Fpr11838.412621.24 2.66E-090.8110 Tnfaip31936.912024.25 6.30E-090.4238Cxcl22036.81760.84 6.79E-140.9650BB5485872136.547111.55 1.85E-060.7213Tnfsf92235.176412.63 5.17E-080.9962Socs32335.101825.02 1.24E-120.2296Ccl22434.012123.20 1.41E-090.5926Ccl72533.98942.028.91E-100.3433Fpr-rs22631.152721.21 3.19E-120.6983Il1rn2729.496911.71 2.74E-100.0624Ets22829.254915.50 3.77E-090.5326Ccrl22929.133019.91 2.75E-080.7250LOC6229763028.831233.45 6.43E-120.1185Il1rn3128.083218.99 4.52E-110.1198 Tnfaip33227.382421.82 1.42E-100.8902Zc3h12c3325.122322.497.12E-100.3216Ccl123425.125913.15 1.25E-080.2671Cdc42ep23524.164416.31 1.03E-080.7966Gpr843623.463119.54 3.15E-100.2886Il1rn3723.357311.359.55E-120.1113Nr4a33822.464815.73 2.80E-080.7223Ccl53922.153618.02 1.01E-070.2819Ch25h4021.836512.599.66E-110.2134Cd404121.426612.25 2.74E-110.8623Cd404221.315413.89 6.89E-120.3615Zc3h12c4321.072821.05 3.52E-100.7250Clec4e4420.752920.40 2.51E-090.9522Malt14520.223318.56 5.46E-120.8940 Hivep34619.932222.60 3.95E-150.4636 Ptges4719.705314.23 2.23E-100.2554Cd694819.603418.55 3.57E-070.5920Cd404919.486013.08 2.69E-120.7930Traf15019.184316.55 5.61E-080.2824 Probe sets from the top50induced targets in PnCW-stimulated control cells are ordered1through50based on fold induction relative to the untreated control cells at4h.The correlative rank of genes expressed in PnCW-stimulated NOD2-deficient macrophages relative to the control ranking is listed along with the P-values(ANOVA)by time relative to unstimulated cells and by genotype.2070L.O.Moreira et al.©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Cellular Microbiology,10,2067–2077strains of Ripk2-/-mice and mice lacking both NOD1and NOD2(Nod1-/-;Nod2-/-)to probe if IL-10production was inhibited.We observed by ELISA and qRT-PCR analysis that RIPK2-deficient cells had a similar phenotype to NOD2-deficient BMDMs(Fig.4)in terms of reduced IL-10 production in response to PnCW.Furthermore,macroph-ages from Nod1-/-;Nod2-/-mice,which have been reported to have similar phenotypes to Ripk2-/-macroph-ages(Park et al.,2007),also had a deficiency in IL-10production when stimulated with PnCW.Finally, when introduced into Nod2-/-macrophages by retroviral-mediated transduction,human NOD2rescued IL-10in response to PnCW and MDP responsiveness (Fig.4E–G).Analogous studies with NOD1were not pos-sible because human NOD1producer lines do not make virus at sufficiently high titre to infect stem cells.Collec-tively,these data provide evidence that NOD2and RIPK2 function in the same pathway that mediated IL-10produc-tion in response to PnCW.Zymosan,a complex cell wall fraction from yeast,has been shown to induce IL-10production by the TLR2-DECTIN1-SYK pathway and the TLR2-DECTIN1-ERK pathway(Dillon et al.,2004;2006;Rogers et al.,2005;Slack et al.,2007).We therefore asked if PnCW also stimulated ERK activation with the idea that ERK could be a common downstream mediator of multiple TLR2-driven pathways,including the TLR2-NOD2pathway.However, we observed that PnCW induced low or negligible ERK phosphorylation(Fig.5).Therefore,PnCW seems to stimulate IL-10production via pathways distinct from those induced by zymosan,even though both the DECTIN1-SYK and NOD2-RIPK2pathways depend on TLR2.Finally,IL-10production in response to PnCW was dependent on MyD88(Fig.5E),suggesting that the TLR2-MyD88pathway is absolutely necessary for PnCW-induced IL-10production.MyD88was not,however, required for MDP sensing(Fig.5F)as expected as shown by the use of a sensitive MDP stimulation assay where nitric oxide production is measured in response to MDP and IFN-g(Totemeyer et al.,2006).By contrast,MDP sensing was dependent on NOD2.DiscussionOur data suggest that NOD2is a component of a signalling module that regulates IL-10production in aFig.2.Absence of NOD2has a limited effecton PnCW-induced inflammatory transcription.A.Select inflammatory targets induced byPnCW in control or NOD2-deficient BMDMs.Data for each target mRNA is plotted as theaverage difference signal intensity.Data areaverages from independent(n=4)Affymetrixarrays performed per genotype and per time.No significant differences(paired t-test)weredetected between plete datasets for this experiment have been depositedin the GEO database.B.Expression of IL-10target genes isaffected in the absence of NOD2function.Signal intensity for IL-10(left most in thepanel)and selected genes whose expressionis dependent,in part,on autocrine-paracrineIL-10production.*P<0.05,paired t-testcomparing4h time points between controland Nod2-/-BMDMs(n=4).The TLR2-MyD88-NOD2-RIPK2signalling axis2071©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Cellular Microbiology,10,2067–2077stimulus-specific and cell type-specific way(Fig.6).Acti-vation of TLR2-MyD88by Pam3CSK4leads to ERK acti-vation and IL-10induction.In contrast,activation of TLR2-MyD88by PnCW invokes NOD2and RIPK2and bypasses ERK activation to produce IL-10.Activation of TLR2and DECTIN by zymosan leads to ERK activation and IL-10induction.It is well accepted that IL-10is essen-tial for regulating the amplitude of most,if not all inflam-matory responses in vivo.Therefore,mutant forms of NOD2may be a component of homeostatic regulation of IL-10in myeloid-derived cells.Notably,Netea and col-leagues have demonstrated that human monocyte-derived macrophages and dendritic cells isolated from people bearing NOD2mutations have reduced IL-10pro-duction in response to peptidoglycan and MDP(Netea et al.,2004;2005;Kullberg et al.,2008).We found parallels between PnCW stimulation of IL-10 production and the activation of dendritic cells by zymosan,a large fragmentary remnant of yeast cell walls. In both cases,immune cells are exposed to particulate fractions of cell walls of varying sizes and displaying a variety of different sugars,lipids and structural biopolymers.Zymosan stimulates IL-10production by a MyD88-independent pathway involving TLR2,DECTIN1, SYK and ERK(Dillon et al.,2004;2006;Rogers et al., 2005;Slack et al.,2007).PnCW stimulation of IL-10also requires TLR2,but does not seem to activate substantial ERK phosphorylation(Fig.5).Instead,MyD88,NOD2 and RIPK2are required.The PnCW and zymosan recog-nition pathways present a considerable contrast to the activation of immune cells with Pam3CSK4through TLR2, a pathway that has an absolute requirement for MyD88 but not NOD2.Therefore,there are different signalling routes to IL-10production following TLR2activation (Fig.6).Similarly,additional diversity of signalling for IL-10production has been observed for receptors such as the LPS-mediated pathway that requires TLR4and p38 (Park et al.,2005),and the immune complex pathway that enhances IL-10production via FcR ligation(Edwards et al.,2006).BTK also plays a key role in stimulus-specific IL-10production:the absence of BTK leads to a decrease in IL-10produced from macrophages and a correspond-ing increase in inflammatory mediators normally blocked by IL-10(e.g.IL-12,IL-6)(Kawakami et al.,2006;SchmidtFig.3.Pro-inflammatory cytokinetranscription in response to PnCW isdependent on TLR2.BMDMs from theindicated genotypes were stimulated withPnCW for the times shown.Cytokine mRNAswere measured by qRT-PCR.Data arerepresentative of three independentexperiments.2072L.O.Moreira et al.©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Cellular Microbiology,10,2067–2077et al .,2006).However,the reduced amounts of IL-10made in the absence of BTK,like the absence of NOD2,is insufficient to initiate the severe inflammatory bowel disease observed in the complete absence of IL-10(Schmidt et al .,2006)(L.M.and P .J.M.,unpubl.data).Therefore,NOD2and BTK both seem to function to tune stimulus-specific IL-10production.We found that neither TLR2nor NOD2were absolutely required for PnCW stimulation of IL-10production.IL-10was made,although in much lower amounts,in the absence of either TLR2or NOD2.However,cells lacking both TLR2and NOD2had a complete abrogation of IL-10production.These data suggest that TLR2and NOD2have a genetic interaction.A similar finding has been made in the ECOVA gut inflammation system where pathology observed in the absence of NOD2was reversed in the combined deficiency of both NOD2and TLR2(Watanabe et al .,2006).It is however,prematuretoFig.4.IL-10expression in response to PnCW is dependent on the RIPK2pathway.A.BMDMs from Ripk2-/-or Nod1-/-;Nod2-/-mice were stimulated with PnCW and IL-10measured over time by ELISA.B.As in (A),but following LPS stimulation.C and D.Analysis of BMDMs from an independent Ripk2mutant strain showing IL-10and IL-10mRNA produced in response to PnCW requires RIPK2.E and F.Reconstitution of Nod2-/-hematopoietic stem cells with human or mouse NOD2cDNAs rescues IL-10production in response to PnCW.Stem cells from Nod2-/-mice were infected with retroviruses containing hNOD2or mNOD2cDNAs and selected by cell sorting for YFP and plated into media containing CSF-1to drive differentiation into macrophages.After differentiation,macrophages were stimulated with LPS or LPS and MDP to measure the MDP synergy with TLR4signalling (E)or IFN-g signalling (F)or IL-10production after PnCW treatment (G).Data are representation of two independent infection studies.In the case of mNOD2,sufficient cells were obtained to perform the MDP-IFN-g synergy assay only.The TLR2-MyD88-NOD2-RIPK2signalling axis 2073©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation ©2008Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Cellular Microbiology ,10,2067–2077suggest that TLR2and NOD2function in a linear pathway where NOD2is downstream of TLR2.Instead,we suggest that cross-talk between the TLR2and NOD2pathways occurs in a stimulus-and cell-specific context.Cross-talk is not revealed when TLR2is stimulated with Pam 3CSK4but instead is exposed by agents such as PnCW and peptidoglycan,at least in the BMDMs used here.This idea may help resolve previous reports that suggested that NOD2was not involved in TLR2signalling (Kobayashi et al .,2005):dependence on both stimulus and cell type is needed to expose differences among pathways.Recent data from human monocytes bearing NOD2mutations has also revealed a complex interplay between NOD2and TLR2(Borm et al .,2008).Using transcriptome profiling,we also found that the absence of NOD2affected a surprisingly low number of mRNAs when BMDMs were stimulated with PnCW.These data are in keeping with published studies suggestingthatFig.6.Model of IL-10production myeloid lineage cells(macrophages and DCs)stimulated by agents that activate TLR2,alone or in combination with other cell surface molecules.Fig.5.PnCW activation of BMDMs does not activate the ERK or p38pathways but requires MyD88signalling.A.C57BL/6BMDMs were stimulated with Pam 3CSK4,LPS or PnCW over time and ERK phosphorylation measured byimmunoblotting for phosphorylated forms of ERK or reprobed for total ERK amounts.B.A similar experiment to (A)was performed using BMDMs from the genotypes indicated on the right.C.The same lysates from (B)were probed for phospho-p38.Note that PnCW does not activate ERK or p38in any of these experiments.D.BMDMs from control,Nod2-/-,Tlr2-/-or MyD88-/-mice were stimulated with PnCW for 8h and IL-10measured by ELISA.Data are average ϮSD from independent samples (n =3).E.BMDMs were stimulated with MDP orMDP +IFN-g overnight and nitrites measured by the Griess assay.Stimulation with IFN-g alone did not produce detectable nitrites (data notshown).2074L.O.Moreira et al.©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation ©2008Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Cellular Microbiology ,10,2067–2077loss of NOD2has minimal effects on pro-inflammatory TLR signalling(Pauleau and Murray,2003;Kobayashi et al.,2005;Park et al.,2007).However,PnCW is an example of a pathogen‘signal’that can activate multiple pathways including the TLR2pathway.It is not surprising that NOD2plays limited roles in the overall transcriptional response as the mammalian immune system most likely has developed multiple,overlapping ways to recognize and respond to such a complex material.Nevertheless, thefinding that IL-10was one of the most affected mRNAs,along with a cohort of IL-10-regulated genes, suggests that further work is warranted to determine the role of NOD2in IL-10production in humans bearing muta-tions in NOD2.It is tempting to speculate that IL-10regulation has key functional significance in chronic inflammatory states such as the inflammatory bowel diseases.Most research-ers agree that common pathways of inflammatory media-tor production,arrived at by a multitude of genetic and environmental mechanisms,drive disease and are the central focus of therapeutic intervention through anticy-tokine antagonists.IL-10plays an essential regulatory role in controlling the products of the common inflamma-tory pathway:IL-12,TNF-a,IL-6,etc.Therefore,small disturbances in temporal,anatomic or quantitative IL-10 amounts may translate into greater inflammation.Experimental proceduresMiceNod2-/-mice have been previously described(Pauleau and Murray,2003).Nod2-/-;Tlr2-/-mice on a C57BL/6background (n=5generations)have been described(Watanabe et al., 2006).Tlr2-/-mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories.Mice were bred and genotyped according to pub-lished protocols.For some experiments,Nod2-/-mice were backcrossed10generations to the C57BL/6background.All animal experiments were performed in accordance with protocols governed by the St Jude Animal Care and Use Committee(P.J. M.,Principal Investigator).Nod1-/-;Nod2-/-and Rip2k-/-mice have been described previously(Chin et al.,2002;Kobayashi et al.,2002;Park et al.,2007).Cell preparation and stimulus conditionsBone marrow-derived macrophages were isolated and cultured as described(Lang et al.,2002).Macrophages were stimulated with highly purified PnCW prepared as described previously (Tuomanen et al.,1985a,b).Briefly,S.pneumoniae unencapsu-lated strain R6were grown in C+Y medium,bacteria were boiled in SDS,mechanically broken by shaking with acid-washed glass beads,and treated sequentially with DNase,RNase,trypsin,LiCl, EDTA and acetone.PnCW was confirmed to be free of protein by analysis for non-cell wall amino acids using mass spectrometry. The absence of contaminating endotoxin was confirmedfirst by the Limulus test(Associates of Cape Cod)and then by ELISA measurement of hIL-8production by HEK293cells transfected with plasmids designed to express TLR4and MD2(a generous gift of Dr Doug Golenbock,UMass)in the presence of purified PnCW.Forfluorescence microscopy experiments,BMDMs were labelled with Phalloidin and4′,6-diamidino-3-phenylindole (DAPI),a nuclear stain.PnCW was directly labelled with 1mg ml-1FITC(Sigma-Aldrich)solution in carbonate buffer (pH9.2)for1h at room temperature in the dark and washed twice with PBS containing calcium and magnesium(Gosink et al., 2000).ELISAELISA was performed as previously described(El Kasmi et al., 2006).Capture and detection antibodies used were purchased from BD Pharmingen.Detection limits for the ELISAs were 50pg ml-1(IL-10)and10pg ml-1(IL-12p40).Northern blotting,RT-PCR and immunoblottingTotal RNA was isolated from primary macrophages using Trizol. Reverse transcription(qRT-PCR)was performed as described previously using primers and probes(Applied Biosciences)spe-cific for each cytokine mRNA(Lang et al.,2002).Immunoblotting was performed using the following rabbit polyclonal antibodies: antiphospho-p42,p44ERK and anti-phospho-p38from Cell Sig-naling Technology used at1:500final dilution.Anti-p42,p44ERK and anti-p38were from the same source and were used at afinal concentration of1:1000.Transcriptome analysisRNA samples from BMDM cultures representing four PnCW preparations,two genotypes(wild-type and the NOD2deficient) and three time points(0,1and4h)were arrayed on Affymetrix GeneChip analysis murine430v2GeneChip arrays.Signal was acquired with MAS5.0software and natural log transformed [ln(signal+20)]to stabilize variance and better conform the data to the normal distribution.Principal components analysis(Partek 6.1)revealed a batch effect which,being orthogonal to hour and genotype,was removed by capturing and mean adjusting residu-als of a one-way ANOVA-based on PnCW batch(STATA/SE9.2). The batch-corrected transformed signal was tested for exposure time and genotype effects in a two-way ANOVA using Partek.The P-values for the time effect were corrected for multiple compari-sons using the false discovery rate(Benjamini et al.,2001).Fold change calculations were based on the geometric means of the batch corrected data between the4h and0h time points for each genotype.Array data has been submitted to the GEO data-base(accession GSE8960).Retroviral-mediated transduction of stem cellsRetroviral transduction of murine bone marrow cells was per-formed as described previously(El Kasmi et al.,2006;Holst et al.,2006a,b).For the transduction experiments,we used fetal liver stem cells isolated from E14pregnant Nod2-/-female mice. Fetal liver cells were cultured for48h in complete DMEM with 20%FBS,20ng ml-1murine IL-3,50ng ml-1human IL-6and The TLR2-MyD88-NOD2-RIPK2signalling axis2075©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishing Ltd,Cellular Microbiology,10,2067–2077。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。