Key Words Product Liability Strict Liability

论我国自动驾驶汽车侵权责任体系的构建——德国《道路交通法》的修订及其借鉴

2021年2月第19卷第1期㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀时代法学PresentdayLawScience㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀Feb.㊀2021Vol.19No.1论我国自动驾驶汽车侵权责任体系的构建德国«道路交通法»的修订及其借鉴∗何㊀坦(长沙学院ꎬ湖南长沙㊀410022)摘㊀要:针对自动驾驶汽车可能带来的法律问题ꎬ德国立法者在坚持既有的机动车侵权责任框架和归责传统的同时ꎬ还针对自动驾驶汽车的准入以及驾驶人的权利义务等问题ꎬ对德国«道路交通法»进行了修订ꎮ按照我国侵权责任理论框架来处理自动驾驶汽车侵权问题ꎬ会出现责任主体认定模糊㊁过错判断标准滞后㊁归责原则混杂等困境ꎮ通过对德国理论的分析与借鉴ꎬ针对我国自动驾驶汽车侵权问题ꎬ有必要重新解读相关规定㊁明确缺陷认定标准㊁尽快制定专门的法律规范ꎮ关键词:自动驾驶汽车ꎻ机动车责任ꎻ产品责任ꎻ危险责任ꎻ过失相抵中图分类号:D923.8㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀文献标识码:A㊀㊀㊀㊀㊀文章编号:1672 ̄769X(2021)01 ̄0046 ̄13ConstructionofChina sAutonomousVehicleTortLiabilitySystem RevisionoftheGermanRoadTrafficLawandItsReferenceHETan(ChangshaUniversityꎬChangshaꎬHunan410022ꎬChina)Abstract:Accordingtotheexistingtheoreticalframeworkoftortliabilityinourcountryꎬtoreg ̄ulatetheinfringementofautonomousvehiclesꎬtherewillbeproblemssuchasvagueidentificationoftheresponsiblesubjectꎬlaggingfaultjudgmentstandardsꎬandmixedliabilityprinciples.Whilead ̄heringtotheexistingtraditionalmotorvehicleinfringementliabilityframeworkandtraditionofliabil ̄ityꎬGermanlegislatorsalsorevisedtheGermanRoadTrafficLawinresponsetoissuessuchastheaccessofautonomousvehiclesandtherightsandobligationsofdrivers.Throughtheanalysisandref ̄erenceofGermantheoriesꎬitisnecessarytoreinterprettherelevantregulationsꎬclarifythedefecti ̄dentificationstandardsꎬandformulatespeciallegalregulationsassoonaspossibleinresponsetotheinfringementofautonomousvehiclesinmycountry.Keywords:self ̄drivingcarꎻmotorvehicleliabilityꎻproductliabilityꎻdangerousliabilityꎻcon ̄tributorynegligence引言随着全球汽车保有量持续增高ꎬ因之而生的交通㊁环境㊁能源等问题日益凸现ꎮ为降低交通事故㊁提高通行效率㊁践行绿色出行ꎬ自动驾驶汽车的研发与投放被提上日程ꎮ经研究统计ꎬ自动驾驶汽车技术的采用可以减少50%~80%的汽车交通事故ꎬ并提升10%~30%的交通通行效率ꎮ自动驾驶汽车在全64∗收稿日期㊀2020-10-15㊀作者简介㊀何坦ꎬ长沙学院讲师ꎬ法学博士ꎬ主要研究方向:侵权责任法ꎮ球范围内已成潮流ꎬ美国交通部于2018年10月4日发布了新版«准备迎接未来交通:自动汽车驾驶3.0»的指导文件ꎬ为自动驾驶汽车与智能交通系统的融合奠定了基础ꎮ欧盟也于2018年发布了«通往自动化出行之路:欧盟未来出行战略»ꎬ明确到2020年将实现高速公路自动驾驶ꎬ2030年进入完全自动驾驶社会ꎮ传统的人类驾驶已经跨越到人车交替操控ꎬ甚至是无人驾驶汽车的时代ꎮ但不可忽视的是ꎬ在此新兴领域中风险与机遇并存ꎬ受限于技术水平与研发水准ꎬ因自动驾驶导致的交通事故如今并不鲜见ꎮ因此自动驾驶事故归责等问题就成为侵权法研究的热点和待解决的难题ꎮ2017年德国联邦议院专门针对自动驾驶汽车修订了«道路交通法»(Straßenverkehrsgesetz)ꎬ详细就概念㊁准入条件㊁责任归属等问题进行规定ꎮ德国«道路交通法»的最新修订以及经此形成的自动驾驶汽车侵权归责体系ꎬ对于我国相关法规的制订及制度构建具有借鉴意义ꎮ因此ꎬ本文从德国«道路交通法»的最新修订切入ꎬ廓清德国与自动驾驶汽车侵权归责问题相关的规范与理论ꎬ进而借鉴德国的最新经验并结合我国的具体情况相应地提出完善建议ꎮ一㊁德国法上自动驾驶汽车的侵权责任:修法㊁体系与特点在自动驾驶汽车的侵权问题上ꎬ德国法仍然延续了机动车交通事故责任以及与产品相关的责任体系ꎮ新修订的德国«道路交通法»虽然并未更改既有的道路交通责任归责主体和原则ꎬ但为自动驾驶汽车归责专门增设了第1a和1b条ꎬ从而赋予了自动驾驶汽车道路交通责任与产品责任新的内容ꎮ(一)德国«道路交通法»的最新修订2017年德国«道路交通法»专门针对自动驾驶汽车增设了第1a条和1b条的规定ꎮ其中ꎬ第1a条第1款肯定了 高度自动或全自动驾驶汽车(Kraftfahrzeugmittelshoch ̄odervollautomatisierterFahrfunk ̄tion) 的法律地位ꎬ即 当机动车辆符合装备高度或全自动化驾驶功能的相关规定时ꎬ允许高度或全自动化驾驶功能汽车运行ꎮ 第1a条第2款进一步界定了 高度自动或全自动驾驶汽车 的内涵ꎬ规定: 本法所称的具有高度或全自动驾驶功能的机动车辆应配备以下技术:1.能够为完成驾驶任务(包括纵向和横向引导)而灵活操控机动车辆ꎻ2.能够在高度或全自动车辆操控期间遵守调整机动车驾驶的交通法规ꎻ3.随时可由驾驶人手动接管或停用ꎻ4.能够识别驾驶人亲手操控车辆的必要性ꎻ5.在将车辆操控交由驾驶人之前ꎬ能够时间充裕地通过视觉㊁声学㊁触觉或其他方式向驾驶人传达亲自驾驶车辆的要求ꎻ6.能够提示与系统要求相悖的使用行为ꎮ 据此ꎬ自动驾驶汽车的主要特性在于车辆自动控制属性以及车辆与驾驶员之间的互动能力ꎮ相应地ꎬ配备有自动巡航等驾驶辅助系统的车辆并非自动驾驶汽车ꎻ如除尘车之类的作业车辆等具有部分自动功能的车辆也不属于自动驾驶汽车的范畴ꎻ而完全不配备驾驶人ꎬ由车辆完全独立承担所有驾驶任务的无人驾驶车辆ꎬ因目前从技术上无法达到投放公共道路交通的水准ꎬ也非德国«道路交通法»所欲调整的自动驾驶汽车 1 ꎮ第1b条对 操控高度或全自动驾驶汽车的驾驶员的权利和义务 做出了规定ꎮ其中ꎬ第1款的内容为: 车辆驾驶人可以通过高度或全自动驾驶功能在车辆行驶期间从交通与驾车事宜中抽身ꎬ但其必须保持一定的警觉ꎬ从而可以随时履行第2款规定的义务ꎮ 第2款规定了 车辆驾驶人有义务立即重新控制车辆 的两种情形ꎬ即 1.当高度自动化或全自动系统要求他进行接管ꎻ2.当他认识到或基于明显的状况应当认识到ꎬ设定的使用高度或全自动驾驶功能的条件不再存在ꎮ 通过开启车辆自动驾驶功能ꎬ驾驶人可从驾车与交通的烦劳中获得解放ꎬ对此并无疑意ꎻ但是ꎬ车辆驾驶人究竟应当随时保持何种程度的警觉ꎬ以及警觉义务与自动驾驶之间的关系ꎬ仅就条文内容来看仍存在不够明确之处ꎮ(二)德国法上自动驾驶汽车侵权现行归责体系1.自动驾驶汽车之产品相关责任(1)自动驾驶汽车 产品缺陷 之德国标准的确立因自动驾驶汽车具有更为强大的科技属性ꎬ自动驾驶汽车的保有人和驾驶人可能并不完全了解自动汽车的性能ꎬ也无法完全有效防控可能发生的权益侵害ꎮ因此ꎬ对于自动驾驶汽车导致的侵权案件而言ꎬ受害人可以从自动驾驶车辆制造商处要求获取赔偿ꎮ按照德国«产品责任法(Produkthaftungsge ̄1 LGKleveꎬUrteilvom23.12.2016-5S146/15ꎬBeckRS2016ꎬ112174ꎻNZV2017ꎬ235ff.74setz)»第1条的规定ꎬ制造商对其产品所造成的损害应承担无过错责任ꎮ当因设计缺陷㊁制造或指令错误导致自动驾驶车辆事故时ꎬ受害人可以根据«产品责任法»第1条的规定要求制造商进行损害赔偿 2 ꎮ按照德国«产品责任法»第4条和第5条的规定ꎬ自动驾驶汽车的 制造商 主要包括车辆的生产商㊁进口商或者缺陷零部件的供应商ꎬ他们应作为共同债务人ꎬ对造成受害人的损害承担连带责任ꎮ由于制造商承担无过错责任ꎬ因此受害人只须对产品缺陷㊁损害结果以及缺陷与损害之间的因果关系进行举证ꎮ当产品不能提供符合一般预期的合理的安全性能时ꎬ可视其为符合德国«产品责任法»第3条规定的产品缺陷ꎮ此外ꎬ由于德国«道路交通法»第1a条第2款第2项明确规定了自动驾驶车辆需要具有 能够使高度自动化或全自动车辆在其运行期间遵守引导车辆的交通法规 的技术ꎬ这意味着该项技术是类似于人类驾驶汽车时识别交通标识和指引装置ꎬ并按其指示进行操控或驾驶人根据具体情况做出刹车㊁躲避等反应ꎮ即使制造商可以开发出优于人类反应能力的系统ꎬ这一标准对于衡量过错仍然具有重要意义ꎮ因此当自动驾驶汽车软件设计或功能缺失导致事故发生或未能预防事故发生ꎬ造成或未能预防原本人类驾驶员尽到合理的注意就可以避免的损害时ꎬ就可以认定该系统具有缺陷ꎮ只有出现德国«产品责任法»第1条第2款第4项所规定的情况ꎬ即造成损害的车辆在投放市场时已遵循有效的强制性法规ꎬ但损害的发生是因车辆投放时的科技水平尚不能发现的缺陷所导致ꎬ即所谓的 发展缺陷 ꎬ才可以免除制造商责任ꎮ具体到符合自动驾驶汽车制造的强制性法规ꎬ主要是指德国«道路交通法»第1a条第3款中列举的规定ꎮ按照该条内容ꎬ自动驾驶汽车制造应当符合并遵循德国以及国际性相关规定ꎮ与此同时还需要满足欧洲议会和理事会于2007年9月5日第2007/46/EC号第20条构建的许可机动车㊁挂斗及其组件以及系统㊁配件和独立技术单元的框架性指令ꎮ当自动驾驶汽车可能因其缺陷导致损害发生时ꎬ制造商必须就该车辆的设计㊁制造等是否符合德国«道路交通法»第1a条第3款规定范围内的所有制造标准进行证明ꎮ如果车辆制造符合相关标准ꎬ那么按照德国«产品责任法»第1条第2款的规定ꎬ制造商可以基于现有科技条件未能识别错误为由ꎬ无须承担损害赔偿责任ꎮ(2)德国法上 生产者 之特别责任的承担尽管我国学者通常将德国的产品责任也称为 生产者责任(Produzentenhaftung) ꎬ但事实上德国法的二者在责任主体㊁责任构成㊁诉讼基础㊁赔偿额度以及举证责任上都有区别ꎬ属于两种不同的责任ꎮ如前所论ꎬ汽车制造商按照德国«产品责任法»第1条承担无过错责任ꎬ但同时根据该法第1条第1款㊁第10条以及第11条规定ꎬ产品责任中的产品限于用户私用产品ꎬ对于缺陷产品造成的损失受害人应当自行承担500欧的损失ꎬ超出该范畴才能向生产者提出索赔ꎬ且索赔也以8500万欧为最高限额ꎮ由于最终制造商把控产品生产的全部流程ꎬ具有较强的赔付能力ꎬ责任也相对重大ꎬ如果其在生产任一流程中出现纰漏㊁生产出侵害用户合法权益的缺陷产品时ꎬ仅仅依靠产品责任的规定显然不利于对用户的保护ꎬ因此当出现超出赔偿限额或侵害的是非私有物的情况下ꎬ德国法上就要求按照以德国«民法典»第823条第1款为基础 3 ꎬ结合该法第276条规定的交往安全义务对生产者苛以 生产者责任 ꎮ如果生产者因故意或过失对产品设计㊁制造㊁警示未能达到合理期待标准ꎬ既生产者违反一般交往安全义务ꎬ就应当对缺陷产品造成的损害进行赔偿ꎮ因此和产品责任不同ꎬ生产者责任是过错责任ꎮ此外ꎬ生产者责任中的 生产者 也被立法者限制为 成品生产者以及必要情况下的销售商 4 ꎮ虽然生产者责任属于过错责任ꎬ但是鉴于司法实践中可能存在生产者与用户之间存在信息掌握不平衡的情况ꎬ法官通常要求生产者自行证明对生产设计㊁制造以及警示没有过错ꎬ即在过错证明上实现举证责任倒置ꎮ在目前阶段ꎬ需要由受害人证明的情况主要涉及违反义务营销和启用自动驾驶汽车的情况ꎮ具体而言ꎬ当自动驾驶汽车未达到德国«道路交通法»第1a条规定的准入条件时ꎬ通常情况下经销商或研发84 234JänichꎬVolker/SchraderꎬPaul/ReckꎬVivianꎬRechtsproblemdesautonomenFahrensꎬNZV2015ꎬS.316.德国«民法典»第823条第1款规定: 因故意或者过失不法侵害他人生命㊁身体㊁健康㊁自由㊁所有权或者其他权利者ꎬ对他人所遭受的损害承担赔偿责任ꎮFuchsꎬMaximilianꎬDelikts ̄undSchadensersatzrechtꎬ9.Auflageꎬ2016ꎬS.143ꎻBGHNJW1994ꎬ517.单位出于经销或研发等需求会对车辆进行展示或操作ꎮ如果在其销售或测试过程中造成他人合法权益损害ꎬ那么除了自动驾驶车辆的保有人外ꎬ制造商㊁供应商㊁技术人员㊁测试工程师等人都须为其违反一般交往安全义务承担责任 5 ꎮ他们应当尽到的注意必须包括认识到自动驾驶车辆尚未达到准入条件这一事实ꎮ由于自动驾驶系统是具有创新性的高风险产品ꎬ因此应当致力于研究其可能产生的损害风险并对此提出严格的要求 6 ꎮ制造商需要承担产品观察(Produktbeobachtungspflicht)义务 7 ꎻ经销商则必须在他认识到产品具有危险或风险时ꎬ至少进行一定回应 8 ꎮ转交车辆的人必须告知驾驶人德国«道路交通法»第1a条第1款所规定的全部使用条款ꎬ并应当向其演示如何操作自动驾驶系统ꎬ否则该转交人会因缺乏指导而对驾驶人造成的损害承担责任 9 ꎮ演示者可以根据德国«道路交通法»第1a条第2款规定的系统描述进行演示ꎮ如果演示者对车辆使用进行了不充分地㊁与技术状况不相符合的描述ꎬ则其应当就车辆造成的损害承担相应的责任ꎮ维护指引自动驾驶车辆行驶所必须的设置的人ꎬ如果未能保证设备的正常运行同样应当承担侵权责任 10 ꎮ通过黑客技术入侵自动驾驶系统造成损害事故的人或已经认识到有黑客入侵ꎬ但可被非难的地(vorwurfbar)未阻止入侵的人也应当承担侵权责任 11 ꎮ2.自动驾驶汽车保有人和所有人之道路交通责任面对新生的自动驾驶汽车侵权责任归责ꎬ德国«道路交通法»并未改变传统的道路交通责任归责原则与规则ꎬ德国«道路交通法»第7条和第18条ꎬ分别针对机动车辆保有人与驾驶人规定了不同的责任承担原则ꎮ针对机动车辆保有人ꎬ第7条第1款规定: 如果驾驶机动车辆或挂斗ꎬ造成他人人身伤亡或财产损害ꎬ则保有人有义务赔偿受害人的损失ꎮ 据此ꎬ保有人应对因其车辆导致的人身与财产损害承担危险责任(Gefährdungshaftung)ꎮ另根据第7条第2㊁3款的规定ꎬ只有损害系由 不可抗力 (höhereGewalt)或 无权驾驶 (Schwarzfahren)所导致ꎬ才可免除保有人的赔偿责任ꎮ而对于车辆驾驶人的责任认定ꎬ第18条第1款第2句规定: 如果损害不是由驾驶人的过错引起的ꎬ免除其赔偿责任ꎮ 可见ꎬ机动车驾驶人承担的是过错推定责任ꎮ(1)自动驾驶汽车保有人之责任归责根据德国司法实践的相关判例ꎬ机动车 保有人 指的是以自己的名义暂时或长期使用或处置机动车或挂斗的人 12 ꎮ在 使用 之外ꎬ机动车的 处置 行为一般包括确定驾驶的原因㊁时间以及时机等 13 ꎮ在机动车外借或租赁情况下ꎬ因承租人将机动车或挂斗用于自己的用途并进行处置ꎬ故承租人是除了所有权人之外的车辆保有人 14 ꎻ但如果承租人完全不受出租人的影响而使用机动车或挂斗ꎬ则出租人丧失保有人身份 15 ꎮ在机动车买卖的场合ꎬ买受人因车辆交付成为保有人 16 ꎻ即使出买方仍然保留对机动车辆的所有权ꎬ买受人也因交付而成为保有人 17 ꎮ以上基本规则同样适用于确定自动驾驶汽车的保有人ꎬ且其亦应按照德国«道路交通法»第7条的规定承担危险责任 18 ꎮ94 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 类似价值链中的责任分配 ꎬBodungen/HoffmannꎬAutonomesFahren ̄HaftungsverschiebungentlangderSupplyChainꎬNZV2016ꎬS.507.EifertꎬMartin/Hoffmann ̄RiemꎬWolfgangꎬInnovationsverantwortungꎬ1.Auflageꎬ2009ꎬS.335.MünchenerKommentar/WagnerꎬBGBɦ823ꎬRn.836ff.VogtꎬWolfgangꎬFahrerassistenzsysteme:NeueTechnik ̄NeueRechtsfragen?NZV2003ꎬS.159.VogtꎬWolfgangꎬFahrerassistenzsysteme:NeueTechnik ̄NeueRechtsfragen?NZV2003ꎬS.156.Jänich/Schrader/ReckꎬRechtsproblemdesautonomenFahrensꎬNZV2015ꎬS.317.Bodungen/HoffmannꎬAutonomesFahren ̄HaftungsverschiebungentlangderSupplyChainꎬNZV2016ꎬS.505.BGHNJW54ꎬ1198ꎻ83ꎬ2492ꎻ92ꎬ900.Vgl.BurmannꎬMichaelꎬStraßenverkehrsrechtKommentarꎬɦ7ꎬ25Auflageꎬ2018ꎬRn.5ꎻKönigꎬPeterꎬStraßenverkehrsrechtKom ̄mentarꎬɦ7ꎬ45AuflageꎬRn.14.OLGHammZfS90ꎬ165.BGHZ173ꎬ182=NJW07ꎬ3120ꎻBGHZ87ꎬ133=NJW83ꎬ1492.OLGKölnDAR95ꎬ485.MichaelꎬStraßenverkehrsrechtKommentarꎬɦ7ꎬ25Auflageꎬ2018ꎬRn.5.GregerꎬReinhardꎬHaftungbeimautomatisiertenFahren:ZumArbeitskreisIIdesVerlehrsgerichtstags2018ꎬNeueZeitschriftfürVerke ̄hrsrecht(Abk.:NZV)2018ꎬS.113.同传统的保有人所具有的免责事由相同ꎬ只有自动驾驶汽车的保有人能够按照根据新修订的德国«道路交通法»第7条第2款和第3款证明损害的发生系因不可抗力或他人无权驾驶所致ꎬ始可免除其赔偿责任ꎮ第7条第3款规定的 无权驾驶 导致责任免除ꎬ主要是指当驾驶人在没有告知保有人或在违背保有人意愿的情况下使用车辆ꎬ则保有人免除赔偿责任ꎮ按照德国«道路交通法»新修订的内容ꎬ自动驾驶汽车保有人的法律地位得以肯定ꎬ因此当保有人符合上述特征时ꎬ其责任可以得以免除ꎮ但其不能将自动控制系统失灵视为可以免除责任的不可抗力ꎬ因为操控失灵并非极不寻常的外部影响ꎬ而是属于自动驾驶汽车典型的潜在风险 19 ꎮ(2)自动驾驶汽车驾驶人之责任归责①自动驾驶汽车驾驶人之归责原则根据德国«道路交通法»第18条第1款第2项规定ꎬ机动车驾驶人应承担过错推定责任ꎬ驾驶人只要证明损害不是其过错造成ꎬ则无须担责ꎮ归结自动驾驶汽车的驾驶人应承担的侵权责任ꎬ目前德国通说认为亦应适用过错推定原则ꎬ即只有当自动汽车的驾驶人可以证明其不具备导致事故发生并造成损害的过错时ꎬ才可以免除损害赔偿责任ꎮ自动驾驶汽车驾驶人可以从正反两个方面推翻过错推定原则ꎮ按照新添加的德国«道路交通法»第63a条第3款的规定ꎬ自动驾驶汽车的数据存储系统(Datenspeicherung)可以确定事故发生时操控系统的状态 20 ꎬ因此驾驶人可以依据第63b条的规定要求保有人提供为免除其责任所必需的数据ꎬ通过数据分析得出事故是由爆胎㊁刹车失灵等机械错误导致ꎬ即可证明驾驶人对于汽车失控没有过错ꎬ因此也无须就所造成的损害进行赔偿ꎮ此外ꎬ自动汽车的驾驶人还可以证明即使其履行了应尽的义务仍不能避免损害的发生来否定其过错ꎮ②自动驾驶汽车驾驶人之义务类型德国学者从德国«道路交通法»第1b条第2款总结出目前阶段自动汽车驾驶人应当履行的义务ꎬ主要包括违规操作㊁接管不当㊁未及时接管㊁未认识到接管必要等ꎮa.违规操作根据德国«道路交通法»第1a条第1款的规定ꎬ只有当机动车辆符合装备高度或全自动化驾驶功能的相关规定时ꎬ才允许自动驾驶汽车准入ꎮ据此ꎬ自动驾驶系统的启动和使用需要满足特定的条件ꎬ对此ꎬ自动驾驶汽车的制造商会做出诸多的禁止性提示ꎬ如禁止在非高速公路行驶ꎬ禁止下雪天行驶ꎬ禁止低于一定速度行驶ꎬ等等 21 ꎮ倘若自动汽车驾驶人并未遵守甚至有意违反此类规定ꎬ则其对于事故的产生具有过错ꎮ此外ꎬ根据第1b条第2款第2项的规定ꎬ当驾驶人认识到或应当认识到自动驾驶车辆的条件已不复存在ꎬ但却未能及时接管车辆驾驶ꎬ也属于违规操作ꎮ对于自动驾驶汽车的具体条件ꎬ也需以自动驾驶汽车制造商制定的规定为标准ꎬ对此ꎬ自动汽车的驾驶人理应熟知 22 ꎮb.接管不当接管的必要性取决于接管控制功能时的危险情况ꎮ接管不当大致可分为不当接管以及接管后操作不当两类情形ꎮ在前一种情形下ꎬ如果驾驶员主动介入了自动驾驶系统ꎬ在意识到危险存在时ꎬ未待系统提示而主动制动或刹车ꎬ并因此导致了损害发生ꎬ则驾驶人必须证明ꎬ该操作符合道路交通所必需的注意义务ꎬ如在行人乱穿马路时紧急刹车ꎬ或者是ꎬ即便驾驶人未曾主动干预ꎬ损害结果也必将发生ꎬ可免除其赔偿责任ꎮ在驾驶人主动或遵循系统提示接管车辆驾驶之后ꎬ驾驶人的行为当然应当符合道路交通安全的要求ꎮ当然ꎬ倘若行人本应尽到必要的谨慎义务ꎬ通过观察交通状况而避免损害ꎬ而自动汽05 19202122BGHZ7ꎬ338ꎬ339ꎻNZV1988ꎬ100.SchmidtꎬAlexander/WesselsꎬFerdinandꎬEventDataRecordingfürdashoch ̄undvollautomatisierteKfz ̄einekritischeBetrachtungderneuenRegelungenimStVGꎬNZV2017ꎬ357ff.GregerꎬReinhardꎬHaftungbeimautomatisiertenFahren:ZumArbeitskreisIIdesVerlehrsgerichtstags2018ꎬNZV2018ꎬ114ꎬ115.KritischeMeinungvgl.ꎬGrünvogelꎬThomasꎬDasFahrenvonAutosmitautomatisiertenFunktionenꎬMonatsschriftfürdeutschesRecht2017ꎬS.974.车驾驶人不论是否介入驾驶均无法避免损害发生ꎬ则驾驶人亦无需承担责任ꎮc.未及时接管当自动驾驶系统提示驾驶人需接管车辆驾驶 23 ꎬ而驾驶人并未及时接管因而造成损失时ꎬ只有当驾驶人能够证明ꎬ即便其及时接管驾驶系统ꎬ损害仍然会发生时ꎬ才能免除其赔偿责任ꎮ«道路交通法»第1b条第1款明确要求自动汽车驾驶人必须保持一定程度的警觉ꎬ即 随时(jed ̄erzeit) 可以 立即(unverzüglich) 操控车辆ꎮ受 随时 的限定ꎬ自动驾驶汽车的自动操控范围应控制在一定范围内ꎬ否则会导致驾驶人在收到系统提示后难以立即接管驾驶操控ꎮ按照德国联邦议院的说明ꎬ 立即 应具有特定的法律含义 24 ꎮ德国司法实践将 立即 界定为ꎬ根据案件的具体情况ꎬ驾驶人应实施可测度的(bemessend)㊁快速的(beschleunigt)㊁非可责的延迟(nichtvorwerfbarverzügert)行为 25 ꎮ按照具体情况下的期待可能ꎬ驾驶员应尽可能快速地回应系统的要求 26 ꎮ德国联邦议院将自动汽车的驾驶人的反应时间确定为1.5至2秒 27 ꎬ驾驶人在这种情况下未被给予检查与思考的时间ꎮ在法律允许的自动汽车驾驶人的反应时间区间里ꎬ驾驶人必须 随时 准备好接管操控系统ꎮ只有严格限定驾驶人的应急时间ꎬ«道路交通法»第1a条第2款第5项关于自动驾驶汽车应及时地向驾驶人发出危险信号警示的规定才有意义ꎮ如果驾驶人无法迅速地做出反应ꎬ则因其并未及时接管操控系统ꎬ而应对造成的损害承担赔偿责任ꎮ由于 立即 接管的要求ꎬ在目前的自动驾驶汽车操控过程中ꎬ驾驶员不得离开驾驶座位㊁躺卧或从事其他无法立即停止的活动ꎮd.未认识到接管必要按照德国«道路交通法»第1b条第2款第2项的规定ꎬ如果自动汽车的驾驶人认识到或基于明显的情况应当认识到使用高度自动或全自动驾驶功能的条件不复存在ꎬ则其有义务立即接管车辆ꎮ也即ꎬ当驾驶人认识到或基于明显的情况应当认识到自动驾驶的条件不再存在㊁需要其立即接管车辆驾驶ꎬ在能够立即接管的情况下却未及时操控车辆ꎬ则被视为具有过错ꎮ但该条款并未对驾驶人的行为准则作出进一步的明确规定ꎮ虽然按照«道路交通法»第1a条第1款的规定ꎬ自动驾驶汽车制造商必须对禁止自动驾驶的具体情形予以明示ꎬ但对于驾驶人过错有无的判断ꎬ并非依据汽车制造商所制定的细则ꎬ而是基于驾驶人对于合规驾驶自动汽车的一般认知或理解 28 ꎮ对于 基于明显的情况应当认识到 的规定ꎬ类似于德国«民法典»第122条第2款规定的情形ꎬ即 如果受害人明知或因过失而不知(可知的)意思表示无效或可撤销的原因时ꎬ则表意人不负损害赔偿责任ꎮ 但 基于明显的情况 之规定ꎬ与第122条第2款规定的情形存在明显的区别ꎬ即只要 明显的情况 如特殊交通状态㊁特殊道路状况㊁特异天气条件或不规则驾驶行为等 客观存在ꎬ即便驾驶人主观上未能意识到ꎬ未对车辆进行接管ꎬ也应认定其具有过错而需承担责任ꎮ由此ꎬ在驾驶人享受自动驾驶的权利与负有的警觉义务之间ꎬ存在着明显的紧张关系 29 ꎮ事实上ꎬ在«道路交通法»草案审议的过程中ꎬ德国联邦议院就曾明确提出ꎬ对驾驶人的义务内容应作出更为具体和明确的规定 30 ꎮ 明显的情况 这一表述过于模糊和概括ꎬ哪些情况应该纳入考察的范围ꎬ以及情况明显与否的判断标准ꎬ均不明了ꎮ相应地ꎬ驾驶人在驾驶自动汽车过程中应尽到何种程15 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 此处主要指出现德国«道路交通法»第1a条第2款第5项和第1b条第2款第1项规定的高度自动化或全自动系统识别出需要驾驶人接管并要求其进行接管的情况ꎮDieBundesregierungDrucksache18/11534ꎬ15[EB/OL].(2018-01-15)[2019-03-30].http://dipbt.bundestag.de/doc/btd/18/115/1811534.pdfꎬ2019年3月30日访问ꎮBVerwGꎬNJW1989ꎬ52(53)ꎻKönigꎬCarstenꎬDiegesetzlichenNeuregelungenzumautomatisiertenFahrenꎬNeueZeitschriftfürVerkehrsrecht2017ꎬS.125ꎻDieBundesregierungDrucksache18/11534ꎬS.15.BGHꎬNJW2008ꎬ985(986).DieBundesregierungDrucksache18/11534ꎬ4.GregerꎬReinhardꎬHaftungbeimautomatisiertenFahren:ZumArbeitskreisIIdesVerlehrsgerichtstags2018ꎬNZV2018ꎬ115ꎬ116.SchirmerꎬNV2017ꎬ253(255).DieBundesregierungDrucksache18/11534ꎬ4.度的注意义务以及如何采取具体措施避免损害发生ꎬ也未进行规定ꎮ针对审议草案的相关规定ꎬ德国联邦政府亦认为应当详细规定自动汽车驾驶人的具体义务 31 ꎮ但 联邦议院交通委员会(Verkehrsauss ̄chussdesBundestags) 的多数成员对此表示反对 32 ꎬ所以在修订后的德国«道路交通法»中ꎬ最终并未对自动汽车驾驶人的注意义务加以详细规定ꎮ虽然如此ꎬ值得注意的是ꎬ在修订草案的释义备忘录中ꎬ 从交通与驾车事宜中抽身 被予以严格的限制ꎬ即驾驶人只能短暂和偶然地脱离于驾驶ꎬ驾驶人释放方向盘或视线偶尔偏移道路并无问题ꎻ但对于诸如照顾后排安全座椅上的儿童㊁更换衣服㊁观看视频或玩游戏等活动ꎬ因其需要驾驶人明显且持续地转移其注意力ꎬ则不被允许ꎮ一般情况下ꎬ在驾驶过程中使用导航设备并不被禁止ꎬ即便驾驶人在驾驶过程中处理邮件或者回发信息ꎬ只要其并未长时间地使用技术设备或从事其他妨碍双手使用的活动ꎬ只要驾驶人能够满足 随时立即接管 的要求ꎬ则其可以享受自动驾驶带来的便利ꎮ总体来看ꎬ限于研发水平的限制ꎬ德国立法者在目前阶段并未赋予自动驾驶者太多的权利与空间ꎬ相反ꎬ立法的重点无疑在于对驾驶人审慎与警觉的强调ꎮ(三)自动驾驶汽车侵权归责的德国 特色籍由德国«道路交通法»的最新修订ꎬ关于自动驾驶汽车的侵权责任归责体系ꎬ德国现行法明显呈现如下特点:1.传统归责体系之坚守新近德国«道路交通法»修订ꎬ并未带来侵权责任归责体系的全面革新ꎮ与传统汽车的归责体系一致ꎬ统观自动驾驶汽车侵权归责的整个过程ꎬ主要涵括作为危险责任的产品责任㊁作为过错责任的生产者责任㊁驾驶人承担的过错推定责任和保有人承担的危险责任等不同类型ꎮ对于归责原则体系及关系ꎬ均以某一主体承担危险责任为基础ꎬ辅以其他主体的过错(推定)责任为补充ꎬ以实现对受害人的多重保护ꎮ具言之ꎬ在道路交通领域ꎬ自动汽车驾驶人以必要的交通注意义务为标准ꎬ证明尽到驾驶义务则不承担损害赔偿责任ꎻ而保有人基于其对事故车辆的实际掌控以及对事故补偿的实现可能ꎬ在不具备免责事由的情况下ꎬ无论过错都应当对受害人所遭受的损害进行赔偿ꎮ在生产环节ꎬ如受害人索赔数额在限度内ꎬ且标的物为私人动产ꎬ产品责任和生产者责任存在竞合ꎬ受害人可以根据案件的实际情况ꎬ针对不同的责任主体选择不同的诉因与诉求ꎻ若当受害人提出超过索赔限额以外的赔偿或受损物为非私人动产时ꎬ则以生产者责任为最终兜底ꎮ在不同的领域与原则之间ꎬ机动车致损相关责任主体之间环环相扣的责任框架清晰可见:当自动驾驶汽车造成损害时ꎬ受害人可以向自动汽车驾驶人㊁保有人㊁生产商等进行索赔ꎮ再区分不同的情况ꎬ当驾驶人不能证明对于损害的发生没有过错ꎬ应当与保有人㊁生产商一起承担连带责任ꎻ如果驾驶人可以证明其对于损害的发生没有过错ꎬ免除其赔偿责任ꎬ原则上由保有人和制造商承担连带责任ꎻ如果保有人可以证明其具有德国«道路交通法»第7条第2款规定的不可抗力时ꎬ可以免除其责任ꎬ由生产者承担责任ꎻ如果保有人可以证明德国«道路交通法»第7条第3款规定的无权驾驶情况时ꎬ其无须就造成的损害进行赔偿ꎬ而由无权驾驶人承担责任ꎮ2.自动驾驶汽车归责内容之进化在既有归责体系和原则框架内ꎬ德国立法者通过修订«道路交通法»ꎬ专门为自动驾驶汽车增设第1a㊁1b条ꎬ分别对自动驾驶汽车的定义㊁自动驾驶汽车的驾驶人作出详细规定ꎮ其中ꎬ第1a条第2款对自动驾驶汽车的定义以及第3款所列举的自动驾驶汽车制造所应当遵照的规定ꎬ对于确定自动驾驶汽车生产商的义务具有重要指示作用ꎬ自动驾驶汽车的准入㊁产品缺陷认定标准都可以以此为依据ꎻ第1b条的内容则专门规定自动驾驶汽车驾驶人的权利㊁义务关系ꎮ德国学者以该款项内容为基础ꎬ对条款中25 3132DieBundesregierungDrucksache18/11534ꎬ13.DieBundesregierungDrucksache18/11534ꎬ9.。

Strict Liability

6

• Disclaimers and waivers of liability for products are often invalidated by courts as against public policy (courts should not condone <宽舒,赦免> the manufacture and distribution of defective products) and typically warranties are limited so that manufacturers and retailers are held responsible for personal injuries caused by the use of the product.

须证明过失伤害或故意伤害的)严格法律责任,绝对法律 责任

• Strict liability is a legal doctrine that makes some persons responsible for damages their actions or products cause, regardless of any “fault” on their part.

2

• 严格责任(Strict Liability)又称侵权法上的无过失责 任,是近代发展起来的一种产品责任理论。按照严 格责任的原则,只要产品存在缺陷,对使用者或消 费者具有不合理的危险(Unreasonably Dangerous) ,并因此而使他们的人身或财产遭受损失,该产品 的生产者和销售者都应承担赔偿责任。 • 由于严格责任减轻了原告的举证责任范围,扩大了 对消费者权益的保护,成为产品责任原则的发展趋 势。 • 美国法学会在1965年出版的《侵权行为重述》中确 认了这一原则。我国的《产品质量法》规定了生产 者应承担严格责任,销售者在特殊情况下也承担严 格责任。

前面面板操作器产品说明书

Product DescriptionThere are many variations and con gurations available for front-of-panel operators. Momentary push buttons, selector switches, push-pull devices, and pilot lights are available for a wide range of industrial applications. Operators are available as individual components,compatible with Bulletin 800G base mount and panel mount contact blocks, power modules, and power module with contact block combination units.Front-of-panel operators can be used with an assortment of accessories including legend plates, locking covers, locking guards and engravedcolor cap inserts.ATTENTION: T o help prevent electrical shock, disconnect from power source before installing or servicing. Follow NFPA 70E requirements. Install in suitable enclosure. Keep free from contaminants.Only suitably trained personnel can install, adjust, commission, use, assemble, disassemble, and maintain the product in accordance with applicable code of practice. If a malfunction or damage occurs, do not attempt to repair the product.IMPORTANTWhen working in hazardous areas, the safety of personnel and equipment depends on compliance with the relevant safety regulations. The people in charge of installation and maintenance bear a special responsibility. They must be knowledgeable of the applicable rules and regulations.These instructions provide a summary of the most important installation measures. Everyone working with the product must read these instructions so that they are familiar with the correct handling of the product.Keep these instructions for future reference as they must be available throughout the expected life of the product.Cat. No.DescriptionBack of Panel Compatibility800G-F-EX 800G-U2FX-EX 800G-V2FX-EX800G-M2-EX 800G-MPE-EX 800G-MKE-EX 800G-Kx-EX 800G-Sx-EX 800G-KSx-EXContact block800G-Px -EX 800G-LFx-EXPower module with contact block800G-N2-EX Flush push buttonContact blockDouble push button Contact blockMomentary mushroom Contact blockPush-pull mushroom Contact blockKey-release mushroom Contact blockKey-release push button Contact blockKnob selector switch Contact blockKey-operated selectorswitchPilot light (illuminated)Power ModuleIlluminated push button( ush)Hole plug -Montageanweisung Notice de montage Istruzioni di montaggioInstrucciones de montaje Инструкция по монтажуInstruções de instalaçãode fr it zh es ru pt koDIR 10001392681 (Version 03)At the end of its life, this equipment should be collected separately from any unsorted municipalwaste.Safety InstructionsImproper installation can cause malfunctioning and the loss of explosion protection.All front-of-panel operators can only be used within the speci ed ambient temperature range (depending on the hazardous areaclassi cation).Use in areas other than those areas speci ed or the modi cation of the product by anyone other than the manufacturer is not permitted and exempts Rockwell Automation from liability for defects and anyfurther liability.The applicable statutory rules and other binding directives that relate to workplace safety, accident prevention, and environmentalprotection must be observed.Before you commission or restart operation, check compliance with allapplicable laws and directives.All front -of-panel operators can be used only if they are in a clean and undamaged condition. Do not modify these operators in any way.Special Conditions for Safe UseWhen 800G operators are installed in electrical equipment, care must be taken to con rm that the temperature at the mounting place is within the ambient temperature range: -55…+70 °C (-67…+158 °F).Harmonized/Designated Standards Conformed ToAssemble, Install, and Commission•Only quali ed personnel are allowed to assemble, disassemble,install, and commission the device.•Protect devices against mechanical damage or electrostaticdischarge.•Only use recommended tools for installation. Do not modifythe front-of-panel operators in any way.Assemble and DisassembleT o prepare the enclosure for installation, consider the following:•Verify that all components are intact (no cracks).•Installation of operators permissible in enclosures with wallthickness between 1…6 mm (0.039…0.236 in.).•Installation of operators permissible in enclosures withM30x1.5 threading or a through-hole of 30.3+0.3 mm.•Reference the following mounting hole layout for a30.3+0.3mm diameter through-hole with cut-out for anti-rotation of the operator.InstallationProceed with installation per the following assembly drawings.•Color insert is compatible with ush push button (catalognumber 800G-F-EX) and double push button (catalog number s 800G-U2FX-EX, 800G-V2FX-EX) operators.Front-of-Panel Operators CertificationsCML 14ATEX3033U ATEX IECEx CM L 14.0014U IECEx 2020322313001867CCC UL-BR 14.0834UINMETROGas Protection Type Dust Protection Type Ambient Temperature RangeMechanical RatingsThermoplastic housing, silicone sealsMaterialsIngress Protection (Operator and Module, Assembled Station)IP64/IP66Ingress Protection (Operator, Module, and Cat. No. 800G-APMC)IP67•EN 60079-0•EN 60079-7•EN 60079-31•IEC 60079-0•IEC 60079-7•IEC 60079-31ATTENTION: Risk of serious injury due to incorrectassembly, installation and commissining.A BDE C[mm (in.)]A(1)(1)Recommended spacing for mushroom push button,emergency stop, and dual push button devices: 100mm (3.9 in). Horizontal (E); Vertical (A)70 (2.75)B 16.5 (0.65)CØ30 (Ø1.181)D 3 (0.118)E (1)40 (1.578)Operator OpérateurBedienelement Operatore Operador1…6 mm (3/64…15/64 in.)2.8…3.4 N·m (25…30 lb·in)800G-AW1800G-AMN1Color InsertInserer des Couleurs Farbige Druckplatte Inserire di Colore Insertar de Colores“Click”II 2 G Ex eb IIC Gb II 2 D Ex tb IIIC Db-55…+70 °C (-67…+158 °F)UKEx CML 21 UKEX 31391U DIR 10001392681 (Version 03)Publication 800G-IN004C-EN-P - May 2022 Installation instruction for Bul. 800G Front-of-Panel Operators2/4•Legend plate frame is not compatible with mushroom (catalog numbers 800G-MPEx-EX, 800G-MKE-EX, 800G-M2-EX) operators.Maintenance•Only quali ed personnel are allowed to do any maintenanceand fault clearance.•IEC/EN 60079-17 must be observed.Y ou must keep all front-of-panel operators in good condition, operate them properly, monitor them, and clean them regularly.The front-of-panel operators, seals, and glands must be checked for cracks, damage, or physical defects regularly.Repair and Replacement•Front-of-panel devices are defective if any of the followingapply:–They no longer actuate the attached back-of-panelcomponents –The lens is damaged on illuminated operators –The integrity of the device or sealing is compromised. •Devices must be replaced with an equivalent catalog numberfrom the manufacturer.Accessories and Replacement PartsFor more accessories and replacement parts that Rockwell Automation o ers, see https:///Push-Buttons/Hazardous-Location/800G .DisposalAt the end of its life, this equipment must be collected separately from any unsorted municipal waste. Follow all local and national requirements for disposal of this product.Approximate DimensionsDimensions are shown in millimeters (inches).Flush Push Button (Cat. No. 800G-F-EX), Illuminated Push Button (Cat. No. 800G-LFx-EX)Momentary Mushroom (Cat. No. 800G-M2-EX)Push-Pull Mushroom (Cat. No. 800G-MPE-EX)Key Release Mushroom (Cat. No. 800G-MKE-EX)Pilot Light (Cat. No. 800G-Px-EX)ATTENTION: Risk of serious injury due toincorrect maintenance.IMPORTANT You can clean front-of-panel operators with compressed air.ATTENTION: Defective front-of-panel operators cannot berepaired; they must be replaced.Legend LégendeBeschriftungsschild Legenda LeyendaInstallation Montage Installation Montaggio InstalaciónRemoval RetraitDemontage Smontaggio ExtracciónDIR 10001392681 (Version 03)Publication 800G-IN004C-EN-P - May 2022 3/4Installation instruction for Bul. 800G Front-of-Panel OperatorsApproximate Dimensions, ContinuedDimensions are shown in millimeters (inches).Key Release Push Button (Cat. No. 800G-Kx-EX)Knob Selector Switch (Cat. No. 800G-Sx-EX)Hole Plug (Cat. No. 800G-N2-EX)Double Push Button —Curved Base (Cat. No. 800G-U2FX-EX)Declaration of ConformityRockwell Automation, Inc. declares that the 800G-xxxxx-EX Series A operators (control and signaling device adapters) are in compliance with Essential Health and Safety Requirements of Directive 2014/34/EU (ATEX) and Directive UKSI 2016:1107 (as amended) as follows:•Equipment Group II, Equipment Category 2•Type of Protection “Ex eb IIC Gb/Ex tb IIIC Db”•Compliance to standards EN 60079-0:2018, EN 60079-1:2014,and EN 60079-7:2015+A1:2018 per ATEX Type Examination Certi cates CML 14ATEX3033U and UKEx Type Examination Certi cate CML 21UKEX31391UThe full text of the EU declaration of conformity is available at the following website:/global/certi cation(0.03…0.23)DIR 10001392681 (Version 03 )Copyright © 2021 Rockwell Automation, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Printed in USA.Publication 800G-IN004C-EN-P - May 2022Product certificates are located in the Rockwell Automation Literature Library: rok.auto/certifications.Rockwell Automation maintains current product environmental compliance information on its website at rok.auto/pec.EEE Yönetmeliğine Uygundur .For Technical Support, visit rok.auto/support.ASIA PACIFIC: Rockwell Automation, Level 14, Core F, Cyberport 3, 100 Cyberport Road, Hong Kong, Tel: (852) 2887 4788, Fax: (852) 2501846expanding human possibilityEUROPE/MIDDLE EAST/AFRICA: Rockwell Automation NV, Pegasus Park, De Kleetlan 12a, 1831 Diegem, Belgium, Tel: (32) 2663 0600, Fax: (32) 2663 0640AMERICAS: Rockwell Automation, 1201 South Second Street, Milwaukee, WI 53204-2496 USA, Tel: 414.382.2000, Fax: (1) 414.382.4444Installation instruction for Bul. 800G Front-of-Panel Operators4/4。

Chapter One Introduction商法翻译!! 2

Chapter One Introduction第一章绪论1. International business law1。

国际商业法2. internationality2。

国际性3. International treaties and conventions3。

国际条约和公约4. International Trade Customs and Usages4。

国际贸易惯例5. the principle of party autonomy5。

当事人意思自治原则6. UN Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods (CISG) (1980)6。

联合国国际货物销售合同公约(公约)的货物(1980)《联合国国际销售合同公约》《联合国国际销售合同公约》7. Convention on International Bill of Exchange and International Promissory Note of the United Nations 《联合国国际汇票和国际本票公约》7。

比尔的国际公约和国际本票联合国《联合国国际汇票和国际本票公约》8. Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards8。

关于承认和执行外国仲裁裁决《承认与执行外国仲裁裁决公约》《承认与执行外国仲裁裁决公约》9. International Rules for the Interpretation of Trade Terms (2000) 《国际贸易术语解释通则》9。

国际贸易术语解释通则(2000)《国际贸易术语解释通则》10. Uniform Customs and Practice for Documentary Credits (UCP600) 《跟单信用证统一惯例》10。

全球供应链管理的效率_均衡和风险问题

全球化是现代企业达成降低成本、满足客户个性化需求、构建企业的核心竞争力等目标的有效策略。

供应链是基于企业间竞争与合作的契约关系,共享供应链各结点企业间的信息资源,实现整个供应链的低成本和高利润,被誉为企业的第三利润源[1]。

借助于立足全球市场、现代信息技术、非核心业务外包、集中生产和销售、减少供应商数量,极力满足顾客苛刻的个性化需求的供应链运营管理理念,使业界一度认识到市场的竞争不再是企业与企业之间的竞争,更多的是供应链与供应链之间的竞争,价值链与价值链之间的竞争。

但同时,由于全球化市场中各企业间的竞争日趋激烈,竞争策略的不可持续性,全球供应链管理正面临新的危机。

如2000年爱立信公司的手机业务由于唯一的芯片供应商断供,而最终被迫退出手机市场;2002年的美国西海岸码头工人罢工;以及2003年中国的“非典”风波和2009年“三聚氰胺”等事件的发生,严重暴露出企业在全球市场追利润最大化的同时所面临的新挑战。

理论研究和实证调查都已经注意到供应链联盟中的诸多合作风险和不确定性。

那么,是什么因素导致了供应链这种较为新型的合作联盟体的不稳定性,多种经典管理策略和新型管理模式频频失效的原因何在,在全球化背景下,供应链管理面临的新挑战和瓶颈是什么等等,深入剖析这些问题,对维持供应链联盟实体的成功和可持续发展有一个全面的视角。

本文将具体分析全球化背景下供应链的几个悖论,效率与均衡和供应链风险管理问题。

一、供应链的复杂性和脆弱性在经济全球化的背景下,为了追求最优的边际成本,企业将生产,采购和销售等环节扩展至全球范围。

随着全球供应链的和国际外包的出现,供应链管理的范围和规模的不断延伸,其管理的复杂程度也大大增加。

供应链管理的复杂性主要源于全球供应链管理的效率、均衡和风险问题郭捷(中央民族大学管理学院,北京100081)收稿日期:2010-11-08基金项目:中央民族大学自主科研青年骨干项目。

作者简介:郭捷(1976-),女,湖南常德人,副教授,博士,主要从事运营管理,风险管理等研究。

key words unit 1

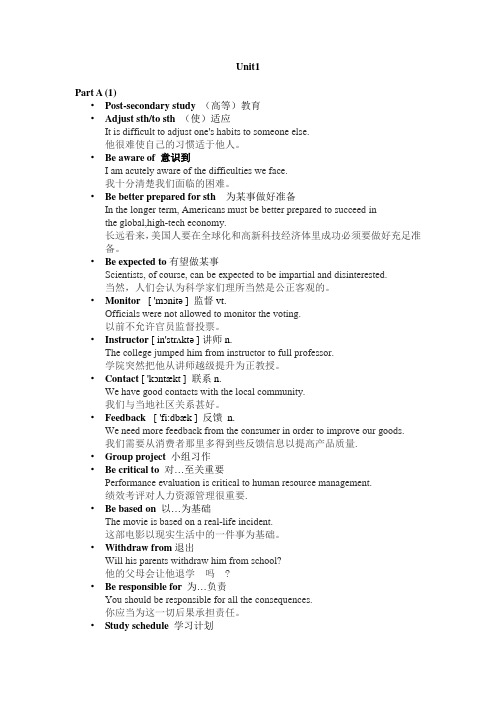

Unit1Part A (1)•Post-secondary study(高等)教育•Adjust sth/to sth (使)适应It is difficult to adjust one's habits to someone else.他很难使自己的习惯适于他人。

•Be aware of 意识到I am acutely aware of the difficulties we face.我十分清楚我们面临的困难。

•Be better prepared for sth 为某事做好准备In the longer term, Americans must be better prepared to succeed inthe global,high-tech economy.长远看来,美国人要在全球化和高新科技经济体里成功必须要做好充足准备。

•Be expected to有望做某事Scientists, of course, can be expected to be impartial and disinterested.当然,人们会认为科学家们理所当然是公正客观的。

•Monitor [ 'mɔnitə ] 监督vt.Officials were not allowed to monitor the voting.以前不允许官员监督投票。

•Instructor [ in'strʌktə ] 讲师n.The college jumped him from instructor to full professor.学院突然把他从讲师越级提升为正教授。

•Contact [ 'kɔntækt ] 联系n.We have good contacts with the local community.我们与当地社区关系甚好。

•Feedback [ 'fi:dbæk ] 反馈n.We need more feedback from the consumer in order to improve our goods.我们需要从消费者那里多得到些反馈信息以提高产品质量.•Group project 小组习作•Be critical to 对…至关重要Performance evaluation is critical to human resource management.绩效考评对人力资源管理很重要.•Be based on 以…为基础The movie is based on a real-life incident.这部电影以现实生活中的一件事为基础。

突发公共卫生事件处置中的隐私权保护探析——兼论《民法典》中的“人格权编”与“侵权责任编”的适用协调

一、问题的提出新型冠状病毒肺炎(以下简称“新冠”)在我国开始传播后,各省陆续启动了重大突发公共卫生事件一级响应。

此后,各级卫生健康委员会都会定期发布疫情报告;各地媒体也会以“行程轨迹”为名,公布某患者的活动轨迹;还有些民众以“提醒远离”为名,不加任何处理地将确诊患者的信息或者疑似患者的信息发布到微信群等网络社区——更有甚者,还对确诊患者和疑似患者进行“人肉搜索”,这让患者和其他民众的隐私权遭到了不同程度的侵害。

可见,如何在患者和其他民众的隐私权与公共利益保护之间进行平衡,是一个我们在“依法抗疫”中不得不面对的法律问题。

2020年5月28日,全国人大表决通过了《中华人民共和国民法典》,其中用了8个条款对自然人的隐私权和个人信息的保护作了规定;而且,隐私权同时作为“人格权编”和“侵权责任编”的客体的二分立法形式也得到了确认,人格权请求权与侵权损害赔偿请求权相分离的规范体系也初步得到了确定,由此,人格请求权的规范意旨便涵盖了对隐私权的保护。

在此法理背景下,有几个问题需要得到解决:一是在对突发公共卫生事件的处置中,隐私权会与哪些权利、权力发生冲突?在该冲突之下,隐私权是否应受到克减?如果受到克减,那么其限度是什么?二是人格权请求权和侵权损害赔偿请求权在保护隐私权时,其构成条件、适用关系和法律效果的区别是什么?厘清这些问题,将有助于在“依法抗疫”之背景下,为个人隐私权的保护与突发公共卫生事件的应突发公共卫生事件处置中的隐私权保护探析——兼论《民法典》中的“人格权编”与“侵权责任编”的适用协调覃榆翔摘要:在突发公共卫生事件中,个人隐私权应受到合法性原则、公共利益优位原则和当事人同意原则的临时性克减。

克减后的隐私权仍受到来自人格权请求权和侵权损害赔偿请求权的保护,且二者在适用上为递进关系:人格权请求权相较于侵权损害赔偿请求权,对损害结果的发生具有预防性;若损害结果发生并符合其他侵权责任构成要件的,则可行使侵权损害赔偿请求权。

浅谈汽车产品的生产一致性管理

浅谈汽车产品的生产一致性管理鲁岩平海马轿车有限公司 河南省郑州市航海东路1689号 邮编450016[摘要] 为切实维护国家、社会及公众利益,规范汽车生产企业行为,国家对汽车产品的生产一致性管理日益严格、完善。

本文旨在通过对国家关于汽车产品强制性认证及生产一致性管理的相关法规研究,结合企业自身实际情况,研究生产一致性管理模型,建立和完善企业生产一致性管理体系,保证企业实际生产销售车辆产品的有关技术参数、配置和性能指标,与《车辆生产企业及产品公告》批准的车辆产品、用于试验的车辆样品、产品《合格证》及出厂车辆上传信息中的有关技术参数、配置和性能指标一致,以满足相关法规要求,规避企业运营的法规风险。

[关键词]质量管理、强制性认证、生产一致性、法规风险Brief Discussion on Automobile Products’Conformity ofProductionAbstract:In order to protect the nation, society and public’s interests, discipline the automobile company’s production behaviour, the nation’s management on automobile products’ conformity of production (COP) is becoming more strict and impeccable. By combining the research on nations’ regulation of automobile products’ compulsory certificate & management of COP with company’s practical situation, this paper is to build and complete the company’s COP management system based on the research of the management model of COP, to ensure the produced & sold vehicles’ technical specifications, configurations and performance index are in accordance with these of the vehicles approved in vehicle production enterprise and product announcement, usedin experiments, in product certificate of quality and uploaded information of the vehicles leaving the factory. This will help the company to fulfill the relative regulation, and to avoid regulatory risks in company operations.Key words:Quality management,Compulsory Certification, Conformity of Production (COP), Regulatory Risks 1 引言2011年6月23日,工信部下发《关于查处江门市华龙摩托车有限公司等企业违规行为及处理决定的通报》,对实际生产车辆与《产品公告》批准参数不一致的江门华龙等3家摩托车厂,做出了撤销其产品公告、责令整改、在整改期间暂停新产品申报的处理决定;对不配合监督检查的21家摩托车企业,责令限期提交整改报告,在整改期间暂停新产品申报;要求各地工业和信息化主管部门切实加强对本地区车辆生产企业及产品的监管力度,督促车辆生产企业以此为鉴,规范企业生产经营秩序,避免发生类似问题。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

LAW AND ECONOMICSSEMINAR, WT 07/08PRODUCT LIABILITYName: Velik MitrevStudent ID: 176164Field of Study: B. Sc. in Economics and Management, 5th Semester Address: Schifferstraße, 24, Magdeburg, 39106Email: velikmitrev@yahoo.vomAbstract:The aim of this paper is to broaden people’s knowledge about the problems arising from defective products and the way they can be managed. Accordingly, the text will consider a detailed description of the importance of product liability law. Special attention is paid to the forms of product liability: strict liability, negligence and breach of warranty. The content of the paper focuses on the different kinds of defects and the costs generated by product liability. It highlights John Brown’s Model, Judge Hand’s BLP Formula, the relationship between product liability and game theory illustrated by the ‘‘prisoner’s dilemma’’ and the rule ‘‘lex loci delictus.’’Key WordsProduct LiabilityStrict LiabilityNegligenceDefective Products‘‘The common law of products liability and oftorts may experience rapid evolutionary jolts,such as the meteoric rise of strict products liabilityin the 1960’s and 1970’s, but quick growth spurtssuch as this are not the end of the story.’’11 Cupp, R. (2006), p. 19.1. Introduction.‘‘The essence of product liability is the apportionment of the risksinherent in the modern mass production of consumer goods.’’2Products liability is a modern phenomenon. It is the responsibility given to customers by manufactures, sellers and distributors to deliver products free of defects. The law of product liability is often connected with conflicts between consumers and industry. When there is a product liability, it has to be decided who should bear the risk: the manufacturer, the victim or the state? There has to be a correct provision of compensation for accidents caused by defective products and it should include financial support, social security awards and insurance payments.32.Product liability.‘‘Product liability suits are subject to an intrinsic bias that substantially increases the likelihood of unwarranted liability.’’4There is a great expansion of individual product liability lawsuits based on strict liability, negligence, or breach of warranty. Product liability prevails only when it is proven that the injuries are caused by a defective product, whose defect existed at the time of the injury and at the time the product left the manufacture’s control. When liability is not proved, victims have to bear their own losses.52.1Strict liability and negligence.For economists, the analysis of strict liability and negligence is very important. The difference between them is that only the negligence requires proof of unreasonable care, while both require proof of defect. Furthermore, strict liability defers from negligence in the extent to which producers must take account of risks. Product risks are borne by the producers under strict liability; under no liability the risks are borne by consumers.6 According to Geraint Howells from the Faculty of Law in University of Sheffield, five stages can be presented at which liability might be imposed:2 Fairgrieve, D. /Vaque, L. (2005), p. 1.3 See loc. cit., p. 2.4 Krauss, M. (2002), p. 13.5 See Polinsky, A. (2003), p. 115.6 See loc. cit., p. 118.•pre -discovery stage (unknowable risks);•discovery stage;•post-discovery stage - dissemination - minority opinion;•post-discovery stage - dissemination - majority acceptance and•recognition stage.7Negligence would impose liability only at the recognition stage. Under negligence, the manufacturer, responsible for the defective product, is liable only in the case when he did not take the proper amount of care to prevent the injury. However, in the case of contributory negligence, any action made by the victim causing the injury, will make the manufacturer not liable for the injury. In the case of comparative negligence, the consumer injured by a product will be compensated in proportion to the fraction of injury caused.8However, when a consumer is injured, it is very difficult for him to prove that the manufacturer was careless in producing the product. Sometimes, the plaintiff cannot prove negligence because in many cases the only witnesses of the negligence are the defendant manufacturer and the employees working in the manufacturing company. Then strict liability may apply and the plaintiff will be expected to prove only the current condition of the product and its impact on the injury.9One of the characteristics of strict product liability is the judgment of the condition of a product.10 It does not have to be proven negligence. The injured party must only prove that the product was defective. Strict liability is most common in the case of manufacturing products. The manufacturer is responsible for any injuries caused by the defective product, no matter what efforts he has put to prevent the injury. Anybody, who is engaged in manufacturing the product, can be liable for the injury as well. If there is a manufacturing defect that causes harm, the supplier of the product is also liable for the defect, regardless cautiousness of the supplier.11 When a single component of a product is defective, then the producer of the component as well as the producer of7 See Howells, G. (1999), p. 3.8 See Rubin, P. (1999), p. 122-124.9 See Boivin, D. (1995), p. 529.10 See Howells, G. (1999), p. 2.11 See Personal Injury Lawyer, (2005).the product will be liable for the accidents caused by the defective component.12 However, when the firm can prove that all necessary procedures were done according to the dictated standards, then the company will be not liable for the damages caused by its product.13Furthermore, a manufacturer is not liable, when the product was substantially altered after it was produced and the changes of the product were the main reason for the injury. There are products such as drugs and vaccines that cannot be made safe for their ordinary use. In this case, product risks can be reduced by giving consumers complete information concerning the product; regulations also decrease the likelihood of product problems.2.2Product liability costs.Product liability is the driver of a lot of costs. The requirement of negligence causes expenses, delays and consequently, the incentive to sue decreases. For each dollar received by a victim, at least a dollar is incurred in costs. There are other costs like lawyers’ fees and litigation costs.14 When the court decides to impose costs for injury caused by a defective product, then these costs will be included in the price of the product. If the injurer is required to compensate the victim, this will deter him from causing inefficient future harms.3.John Brown’s model.The Model discussed by John Brown in his paper ‘‘Toward an economic theory of liability’’, published in ‘‘The Journal of Legal Studies’’ in 1973, explains the basic liability rules15:12 See Howells, G. (1999), p. 8.13 See Trienekens, J./Beulens, A. (2001), p. 4.14 See Polinsky, A./Shavel, S. (2007), p. 22.15 See Brown, J. (1973), p. 324.Figure 1 from John Brown’s paper ‘‘Toward an economic theory of liability’’, represents the relationship between X, Y and P(X, Y). X and Y are two inputs and P(X, Y) is the output produced by these two inputs. In the case discussed in the paper of John Brown, P(X, Y) is the probability that an accident will not occur. Consequently, the probability that an accident will occur is 1-P(X, Y). It has to be found the least combination of X and Y, that will yield to accident avoidance. If the cost of X is Cx and the cost of Y is Cy then the total cost would be Cx*X+Cy*Y. Let the liability of the manufacturer, who has produced the product, is Lm(X, Y) and Lv(X, Y) the liability of the victim. We assume that16:Lm(X, Y) ≥ 0 and Lv(X, Y) ≥ 0 for all X and Y andLm(X, Y) + Lv(X, Y) = 1 for all X and YThen the amount which will be paid by the manufacturer, in case it will be proven that he is liable for the injury of the victim, will be A*Lm(X, Y), where A is money. Using the model above, Brown explains the liability rules.17 Below are explained five of the liability rules discussed in Brown’s paper:•When the manufacturer is not proven to be liable for the injury, then the victim is liable for his own injury - no liabilityLm(X, Y) = 0 Lv(X, Y) = 1 for all X and Y•When the manufacturer is liable for the injury, then he has to compensate the victim – strict liabilityLm(X, Y) = 1 Lv(X, Y) = 0 for all X and Y•The manufacturer will be liable for the injury only in the case when the plaintiff can prove that the manufacturer was negligent – the negligence rule Let (X*Y*) be a standard of negligence. A manufacturer is negligent in the case when X*>X.16 See loc. cit., p. 245, 327.17 See loc. cit., p. 328.•Strict liability with contributory negligence - the injurer is liable unless the victim is found negligent•The negligence rule with contributory negligence4.Defects.There are three types of product defects that can lead to liability: manufacturing, design defects and defects in warning.4.1Manufacturing defects occurring during the production of the item.There is a manufacturing defect when a product cannot meet its advertised specifications. Such defects are relatively rare and do not lead to high costs. They are independent, which means that when a single unit of a product is defective, the other products will not be defective. The consumer cannot avoid the risk of a manufacturing defect, since they occur in the manufacturing process in the company where the product is produced.184.2Design defects existing before the product is manufactured.There is a design defect, when the producer was able to design a product in a way that would have been safer for the consumers. When there is a design defect, all production units are defective, since all of them have the same design. This leads to higher costs for the company because they cannot sell defective products. Plaintiffs usually claim that it has been possible to produce a product with a better design, while defendants claim not. It is not easy to be determined when a product design is defective. It’s needed a second18 See Rubbin, P. (1999), p. 123.guess for whether an alternative design was possible or not. However, this is very difficult and very costly. The cases that are not normally filed are the most expensive and difficult, consequently there is a great saving for the states from eliminating them.194.3Marketing defects.The last type of defects is associated with the warnings that a producer fails to give regarding the dangerousness of a product. Manufacturers are often found liable for not properly warning the consumers, leading to misuse. A manufacturer is required to warn the consumers of hidden danger that may occur by using the product and he must instruct consumers how to use safely the product. When warnings are properly written, the social costs of injuries and accidents will decrease. Warning also helps consumers to decide which product to buy and from which manufacturer to buy it. This will enable them to reduce their costs of potential accidents.5.Product liability, Prisoner’s Dilemma and Lex Loci Delictus.‘‘A Prisoner’s Dilemma is a predicament in which a number of individuals, acting independently, are each rationally impelled to make choices that, when combined with the other individuals’ equally rational choices, generate a very poor outcome for each individual.’’20 In most typical product liability cases, the usage and the purchase of the product take place near the home of the consumer. Consequently, the product liability suit is initiated by a plaintiff, who has been injured in his home state. However, the majority of products consumed in a state are produced outside the jurisdiction of that state. This is the reason why in USA a product liability Prisoner’s Dilemma cannot be neutralized by industrialization. The Prisoner’s Dilemma comes from the fact that plaintiffs of one state and out-of-state defendants are combatants in a product liability suit. That is why; state legislatures are unlikely to adopt product liability rules in ways favorable to out-of-state interest. However, if each state has an efficient product liability rules, national consumer surplus would be maximized while the cost of doing business between states would be lowered.21The commerce among states would increase and19 See loc. cit., p. 123.20 Krauss, M. (2002), p. 25.21 See loc. cit., p. 25, 27.there will be more out-of-state investments. However, if states apply exploitative rules, this will lead to high increase in production costs and consumer surplus will get lower.22Prisoner’s dilemma as Conceptualized by Justice NeelyNebraska can optimize its reward if it adopts rule exploiting the defendants. If Montana has a neutral rule, Nebraska’s payoff increases from 30 to 45 by adopting an exploiting rule. If Montana uses exploiting rule, Nebraska increases its payoff from -10 to 5. If Montana and Nebraska cooperate by promising to adopt neutral rules, Nebraska’s agents will have incentives to break the agreement. Nebraska will be better to adopt exploiting rule even thought there will be a social loss of 25 if Montana adopts exploitive rule, when compared to the neutral rules of the states. (Total payoff in the upper left box is 30 + 30 = 60, total payoff in the lower left box is 45 + (-10) = 35. L= 60 – 35 = 25, where L is loss.) It is better for Montana to adopt an exploiting rule no matter what rule will be adopted by Nebraska. The expected outcome will be (5, 5), which is worse from each state’s perspective. This is the so called Pareto-inferior position.23The lex loci rule applies the law of the place where the injury occurred to determine the liability.24Let’s look the case, when a customer living in Nebraska wants to travel to Montana to buy a product produced in West Virginia. After the purchase, the customer will return to his state where he will use the product. If the consumer is injured using the product, then courts in Nebraska will apply the product liability law of state Nebraska to determine the liability of the manufacturer for the injury. Courts in other states would also apply the product liability law of state Nebraska, when the injury wasin state Nebraska. Under this rule, the location of the manufacturing facilities plays no role in determining the manufacturer’s liability. The manufacturer will be liable for the injury caused in Nebraska under the product liability law of Nebraska no matter in22 See loc. cit., p. 26.23 See loc. cit., p. 27.24 See loc. cit., p. 31.which state are the facilities of the company. Manufacturers will be not able to price their products differently in different states because of the adverse selection caused by the arbitrage. Out-of-state purchase causes the arbitrage. 256.Product liability directive.The main purpose of the Product liability Directive is to protect EU consumers from damages caused by a defective product or service. It covers any defective product manufactured or imported into the European Union that causes damages to consumers. Factors that can make the product defective can be: the presentation of the product, the time the product is put into consideration as well as whether the product is being put into reasonable use from the side of the consumers.26When there is an injury caused by a defective product, the victim has three years for compensation, while the manufacturer’s liability expires after ten years from the date on which the product was placed on the market.27 There are three types of damage payments: pecuniary damages, no pecuniary damages and punitive damages.28Pecuniary damages compensate consumers for money loses. No pecuniary damages compensate individuals for non-monetary losses. Example of no pecuniary damage payment is for pain and suffering. When there is a punitive damage, the goal is not only to compensate the victim, but also to punish the party responsible for the injury.Damage payments are seen like insurance. The manufacturer will increase the price of a product; the consumer will pay the higher price and will be compensated if he is injured by the defective product. However, individuals do not buy insurance against pain because injuries reduce the marginal utility of the victims. This can be easily seen by the shape of the utility function of an individual.7.Examples of product liability.Smoking can cause disease, suffering, and even death. Cigarette smoking and exposure to secondhand smoke kills 440,000 Americans each year. The annual number of deaths due to cigarette smoking is much higher than the total annual number of deaths due to25 See loc. cit., p.31-35.26 See Delaney, H./Zande, R. (2001), p. 1-3.27 See loc. Cit., p. 5.28 See Rubbin, (1999), p. 124-125.alcohol consumption, drug use, automobile accidents, fires, suicides, and AIDS.29On May 2007, Richard Schwarz, personal representative of his wife Michelle Schwarz, was awarded compensatory damages of $ 168,514.22 and punitive damages of $ 150 million against the defendant Philip Morris Incorporated. Michelle Schwarz died at the age of 53 on July 13, 1999.30 The plaintiff stated that Michelle Schwarz’s death was a result from lung cancer, caused by cigarettes manufactured by Philip Morris Incorporated. It was stated that the cigarettes used by Michelle Schwarz were defective and dangerous. The plaintiff stated that Philip Morris is negligent for selling light cigarettes as a safer cigarette and as an alternative to cessation and for the intentionally misrepresentations of its tobacco products. On February 20, 2007, the Supreme Court decided Philip Morris to pay $32 million to the plaintiff. 31The McDonald’s Coffee Case.32A 79-year-old woman ordered a cup of coffee from McDonalds. When she attempted to open the lid, the coffee spilled. The coffee was 135-140 degrees Fahrenheit causing third degree burns. The decision of the jury was that the coffee was a defective product. The victim was awarded $200 000 in compensatory damages and $2 700 000 in punitive damages. Later, the punitive damage was reduced to $480 000 and the compensatory damage by 20% (the jury had decided that the victim had 20% fault and McDonalds 80%).The Ford Pinto Case33 – How much costs a human life?In 1968, Ford Ponto was produced on an accelerated schedule. A defective fuel system design caused the explosion of the car. This led to the death of Lily Gray. The family of Lily Gray was awarded $560 000. Ford had a new design, the use of which would have decreased the likelihood of Ford Pinto to explode. This new design would have cost only $11 per produced car and would have saved 180 Ford Pinto’s drivers. According to Ford’s analysis, the monetary cost of changing the design would have been $137 million versus the social benefits of $49.5 million price on the deaths and car damages.29 See Kessler, (2006), p. 219, 220.30See The Court of Appeals of the State of Oregon, (2006).31 See Dreier, W. /Thompson, K. (2007).32 See Inman Flynn Biesterfeld & Brentlinger.33 See Leggett, C. (1999).Consequently, because of the high costs, Ford decided to use the previous more dangerous model. This decision was explained by Judge Hand’s BLP formula.Judge Hand represented the theory of negligence as an algebraic equation, the BLP formula:Burden/Injury BLP ProbabilityCost of accident if it did occurIf B<PL, then the person is found to be negligent and liable for the damages. B is the burden of a precaution, the accident avoidance cost. L is the cost of the accident if it occurred. PL is the expected liability of the discounted accident cost. A company must take precaution in the case when the expected harm exceeds the cost to take the precaution.34 Let us consider the example of the company producing soda in cans and bottles illustrated in ‘‘An introduction to law and economics’’ in chapter 14th by A. Mitchell Polinsky. If the company produces soda in bottles, the cost per unit will be $1.00. The chances of an injury will be 1/10 000. If the product is manufactured using cans, the cost per unit produced will be $1.03 and the likelihood of an injury will be 1/200 000. If the company uses cans, this will cause an additional cost of $0.03 per unit produced, but it will decrease the accidents losses by $0.08.35 In this case, according to the Judge Hand’s BLP formula, the company has to produce soda in cans.8.Conclusion.In our daily lives, we use different products. We used them as it is directed on the label of the product, assuming right away that the products are reliable and safe. However, each year thousands of people are injured or even die because of dangerously defective products. According to The Consumer Product Safety Commission, over 22 million injuries are related to defective products each year. Injuries, property damage and deaths caused by defective products, costs the USA more than $700 billion each year.36Product liability is a field of the law which has evolved through the years. Today, there are a lot of product liability rules which are used to determine who is liable: the34 See loc. cit.35 See Polinsky, A. (2003), p. 113, 114.36 See The Consumer Product Safety Commission USA.producer, the consumer or the state. However, when all of the effects of product liability rules are taken into account, it is clear that no one rule is the best in each respect. What liability rule should be used depends always on the product liability case and on the relative importance of the competing consideration in the particular case.3737 See Polinsky, A. (2003), p. 123.List of ReferencesBoivin, D. (1995): Strict products liability (revisited): in Osgoode Hall Law Journal, Volume 33, No. 3, Osgoode Hall Law School York University, Canada, p. 529. Brown, J: (1973): Toward an Economic Theory of Liability, The Journal of Legal Studies 1973, The University of Chicago Law School, 245, 324, 327, 328. Consumer Product Safety Commission (2007): CPSC Overview:/about/about.html, 02.11.2007.Cupp, R. (2006): Believing in products liability: Reflections on Daubert, doctrinal evolution, and David Owen’s ‘‘product liability law’’, The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress), Pepperdine University School of Law, p. 19.Delaney, H. /Zande, R. (2001): A Guide to the EU Directive Concerning Liability for Defective Products (Product Liability Directive): U.S. Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology, /Standards/Global/upload/product-liability-guide-824.pdf,20.11.2007, 1-3, 5.Dreier, W. /Thompson, K. (2007): Recent Court Rulings affect Punitive Damages: New Jersey Lawyer, (reprinted 14.05.2007), Volume 6, No. 20.Fairgrieve, D. /Vaque, L. (2005): Product liability in comparative perspective: Product liability and overlapping interests, 1st published 2005, Cambridge U niversityPress: New York, USA, 1, 2.Howells, G. (1999): The Millennium Bug and Product Liability, The Journal of Information, Law and Technology (JILT), University of Warwick – WarwickLaw School, United Kingdom,/fac/soc/law/elj/jilt/1999_2/howells/#fn1,04.12.2007, 2, 3, 8.Inman Flynn Biesterfeld & Brentlinger: Colorado Products Liability Law: Explaining the McDonald's Coffee Case:/2000/Aug/1/130741.html, 02.11.2007.Kessler, G. (2006): Civil Action No. 99-2496 (GK):/litigation/cases/DOJ/20060817KESSLEROPINIONAME NDED.pdf, 20.11.2007, 219, 220.Krauss, M. (2002): Product liability and game theory: One more trip to the choice-of- law well, working paper No. 02-09, Arlington, VA: George Mason UniversitySchool of Law, USA, 25- 27, 31-35.Leggett, C. (1999): The Ford Pinto Case: The Valuation of Life as it applies to the Negligence-efficiency Agreement: Wake Forest University,/~palmitar/Law&Valuation/Papers/1999/Leggett-pinto.html,20.11.2007.Personal Injury Lawyer: Strict Product Liability Law:/productliability.cfm, 20.11.2007.Polinsky, A. (2003): An introduction to law and economics: Product liability, 3rd Edition, Aspen Publishers, New York, USA, 113-115, 118, 123.Polinsky, A./Shavel, S. (2007): American Law & Economics Association Annual Meetings: The Uneasy Case for Product Liability, Berkley Electronic Press,/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2216&context=alea,20.11.2007, p. 22.Rubin, P. (1999): Courts and the Tort-Contract Boundary in Product Liability, in Buckley, F.: The Fall and Rise of Freedom of Contract: Duke University Press1999, USA, 122-125The Court of Appeals of the State of Oregon, (2006),/litigation/cases/supportdocs/schwarz_v_pm_en_banc_5-17-06.htm, 20.11.2007.Trienekens, J. /Beulens, A. (2001): The implications of EU food safety legislation and consumer demands on supply chain information systems: Netherlands,/conferences/2001Conference/Papers/Area%20IV/Trienekens_Jacques.PDF 20.11.2007, p. 4.Table of ContentsAbstract (iii)Key Words (iii)1. Introduction (1)2. Product liability (1)2.1 Strict liability and negligence (1)3. John Brown’s model (3)4. Defects (5)4.1 Manufacturing defects occurring during the production of the item (5)4.2 Design defects existing before the product is manufactured (5)4.3 Marketing defects (6)5. Product liability, Prisoner’s Dilemma and Lex Loci Delictus (6)6. Product liability directive (8)7. Examples of product liability (8)8. Conclusion (10)List of References (12)。