The boundaries of copyright

十大经典知识产权案例

十大经典知识产权案例1. iPhone vs. Samsung: Battle over PatentsIntroduction:The intellectual property battle between Apple and Samsung has been one of the most prominent legal disputes in the technology industry. This case marked a turning point in the struggle to protect and enforce patents in the global market. In this article, we will explore the key details and implications of this high-profile dispute.2. Oracle vs. Google: The Copyright ClashIntroduction:The ongoing legal feud between Oracle and Google revolves around the use of Java programming language in the Android operating system. This groundbreaking case has significant implications for software copyright protection and fair use in the tech industry. In this section, we will delve into the facts and analysis of this iconic intellectual property dispute.3. Coca-Cola vs. Pepsi: The Battle for Trademark SupremacyIntroduction:The rivalry between Coca-Cola and Pepsi extends beyond the supermarket shelves. It has spilled over into legal battles over trademark infringement and unfair competition. This case serves as a classic example of how large corporations protect their brand identities and safeguard their market share. In this part, we will examine the details and outcomes of this famous intellectual property clash.4. Microsoft vs. Apple: The GUI LawsuitIntroduction:The historic lawsuit between Microsoft and Apple focused on the graphical user interface (GUI) and its potential copyright infringements. This case illuminated the importance of interface design and its legal protection in the software industry. In this section, we will analyze the key arguments and implications of this significant intellectual property case.5. Barbie vs. Bratz: The Doll WarsIntroduction:The legal battle between Mattel's Barbie and MGA Entertainment's Bratz dolls captivated the toy industry. This case brought attention to the protection of product design, trade dress, and the importance of intellectual property in the lucrative toy market. In this part, we will explore the details and impact of this landmark intellectual property dispute.6. Gucci vs. Forever 21: The Fashion Copyright ShowdownIntroduction:The fashion industry has been no stranger to intellectual property disputes. The case between luxury brand Gucci and fast-fashion retailer Forever 21 shed light on copyright infringement in the world of fashion and the challenges of protecting designs. In this section, we will delve into the facts and outcomes of this influential legal tussle.7. Nintendo vs. Commodore: The Video Game Copyright ConflictIntroduction:The legal clash between Nintendo and Commodore centered around the copyright infringement of video games. This case had far-reaching implications for the gaming industry and established the importance of copyright protection for creative works in the digital realm. In this part, we will analyze the details and significance of this significant intellectual property case.8. Louboutin vs. YSL: The Battle of the Red-Soled ShoesIntroduction:The trademark dispute between shoe designers Christian Louboutin and Yves Saint Laurent (YSL) grabbed headlines worldwide. This case highlighted the significance of trademarks in the fashion industry and the challenges of protecting brand identity. In this section, we will examine the intricacies and consequences of this iconic intellectual property clash.9. Google vs. Oracle: The API ControversyIntroduction:The protracted legal feud between Google and Oracle over the use of Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) in Android brought the issue of copyrightability of APIs to the forefront. This case has significant implications for software developers and the boundaries of copyright protection. In this part, we will explore the facts and analysis of this influential intellectual property dispute.10. Walt Disney vs. The Air Pirates: Protecting Original CharactersIntroduction:The legal battle between Walt Disney Productions and The Air Pirates comic book showcased the importance of protecting original characters from unauthorized use and infringement. This case set a precedent for intellectual property protection in the comic industry. In this section, we will delve into the details and impact of this historic intellectual property clash.Conclusion:These ten iconic intellectual property cases have shaped the landscape of patent, copyright, and trademark laws. Each dispute had its unique circumstances and implications, reflecting the complex nature of protecting intellectual property rights. By studying these cases, we gain valuable insights into the evolving legal frameworks and challenges of safeguarding creative works and innovations.。

2023-2024学年山东普高大联考高二上学期10月联合质量测评英语试题

2023-2024学年山东普高大联考高二上学期10月联合质量测评英语试题Whether you want a slow pace of life or to surf off white-sand beaches, find your perfect remote getaway in the Indian Ocean.Alphonse, SeychellesThe surrounding pancake-flat atolls (环礁) are a Noah’s Ark for rare wedge-tailed shearwaters, boobies and other astonishing sea life; highlights of the BBC’s Blue Planet series were shot here. Visit to join conservation projects such as ocean clean-ups and turtle-tracking, as much as to drop off the radar. Tourism is such a recent arrival that div e sites are still being mapped out.Zanzibar, TanzaniaIn Zanzibar’s historical capital city, the Stone Town neighbourhood remains a fascinating African-Arabian co mbination, with former Sultans’ palaces in the confusing lanes (小路). Zanzibar is in a sweet spot where resort-level comforts can be found, but they haven’t come at the expense of its charms. Beaches here remain as good as any in the Indian Ocean, but the hotels typically cheaper than Alphonse.Mafia, TanzaniaProbably a mispronunciation of morfiyeh—the Arabic word for group—Mafia is a terrific name for a Tanzanian island that somehow escapes attention. Here Mafia Island Marine Park offers around 320sq miles of diving opportunities just off shore: expect to see healthy coral reefs, wall dives and channels where dugong graze. Humpback whales and hawksbill turtles also call this region home. Havelock, Andaman Islands, IndiaHavelock, the most developed island, is effortlessly beautiful: mi le upon mile of wild beach; barefoot luxury in hotels set within lush jungle; great diving and kayaking through mangrove forests. Havelock’s charm is its authenticity: in villages, families ride in rickshaws, roadside eateries rustle up fish curry and there’s chai at street stalls. By the time you leave you’ll question why you didn’t book for longer.1. What makes Zanzibar stand out as a destination in the Indian Ocean?A.Historical architecture. B.Beautiful beaches.C.Affordable accommodations. D.Confusing lanes.2. What do the Alphonse and Mafia have in common?A.They offer free diving opportunities.B.They are rich in diverse marine life.C.They have environmental initiatives.D.They are popular tourist attractions.3. If you want to taste local specialties, where should you go?A.Zanzibar, Tanzania. B.Alphonse, Seychelles.C.Mafia, Tanzania. D.Havelock, Andaman Islands, India.As I grow up, our shelves were full of cookbooks, each full of my mum’s handwriting. Included in the handwriting were dates when recipes had been cooked, who they’d been cooked for, whether or not they were any good, and any alterations that had to be made (“too salty,” “double the recipe,” “didn’t have this, used that instead”). Where other forms of literature can feel rare, even precious to some, cookbooks permit this kind of writing.Truth be told, cookbooks I often go back to are obvious before you even turn to them—wrinkled paper, spotted and marked. I’ve halved the amount of sugar in a cake recipe from Rukmini Iyers’ The Green Roasting Tin. I’ve added a spicy mix to a carrot salad from Ruby Tandoh’s Flavour. For better or worse, the cookbooks I own are owned by nobody else.If you do this too, and feel guilty about writing through thoroughly tested recipes or messing up beautiful paper, you needn’t. The practice of writing on cookbooks is essential to the experience of reading, and indeed, using them. Often these notes can provide a window into the owner’s life, which is one of the reasons why cookbooks are often handed down within families. In many cases they are the only written records we have from our loved ones. I think that they are telling stories and inviting conversations. Implied in conversation is talking back, exchanging something with the loved ones, and maybe exchanging something with a version of yourself in the future.Sometimes I wonder what I’m buying when I buy cookbooks. Is it inspiration to do something I’ve not done before, or permission to give myself the time to feel addicted to a hobby? My friend Ella sums up her own insight into food writing simply with “writing about food is writing about being alive,” so maybe that’s what I’m buying, and what we all are.4. What can we know about the author’s mom?A.She was a professional cook. B.She collected literature works.C.She often made notes on cookbooks. D.She wrote popular cookbooks.5. What does the author think of the writing in cookbooks?A.It improves life quality. B.It carries future dreams.C.It helps comprehend its writer. D.It makes recipes easy to read.6. Why does the author buy cookbooks?A.To record her life of cooking. B.To meet her hobby.C.To share ideas with friends. D.To gain cooking inspiration.7. What is the best title of the text?A.Why We Need to Buy CookbooksB.How We Adjust Recipes in CookbooksC.Why We Should Be Writing in CookbooksD.How We Pass Down Cookbooks with NotesDo you use the weekends to catch up on sleep? If so, you may want to rethink that. Since the 1990s, scientists have understood that lacking sleep can harm people’s health. The changes it causes can lead to obesity and diabetes. Yet in a recent survey, a little more than one in every three U. S. adults reported sleeping fewer than the recommended seven hours a night.Weekends may seem like a great time to catch up on sleep. Scientists, however, weren’t sure that would work. So Christopher Diner, a sleep physiologist at the University of Colorado and his colleagues decided to test it out.The team looked at three groups of people in their mid-20s. For roughly two weeks, each group followed a set sleep schedule. One group slept about eight hours every night. Another group only got about five hours of shuteye a night. The third group slept some five hours each weeknight, but could sleep whenever and however much they wanted over the weekend.The groups with less sleep snacked more at night, gained more weight, and saw their insulin (胰岛素) sensitivity drop compared to the group getting nine hours a night, said the study. The group that received two days to catch up on sleep saw some small improvements that were lost once they returned to a shorter sleep schedule. People in the study who got too little sleep every night gained weight. So did the weekend sleep-in crowd.“In the end, we didn’t see any benefit in any metabolic (新陈代谢的) outcome in the people who got to sleep in on the weekend,” Chris Depner, an assistant research professor of the study said in a statement. In some cases, insulin sensitivity among members of the group with the weekend to catch up declined more than those who consistently slept five hours a night, said the study.8. Why did Diner and his team conduct the study?A.To assist doctors’ work.B.To finish an assignment.C.To prove their assumption. D.To remove their doubt.9. How did the researchers carry out the test?A.By using a questionnaire. B.By comparing three sleep patterns.C.By tracking one group for two weeks. D.By making cause-and-effect analyses. 10. What do we know about catching up on sleep according to the study?A.It requires further study. B.It makes no difference to health.C.It may lead to a regular sleep pattern. D.It may bring more harm than benefits.11. What may the following paragraph probably focus on?A.Ways of catching up on sleep. B.Benefits of exercise for sleep.C.Suggestions on healthy sleep. D.Disorders from lacking sleep.Comedian Sara Silverman recently joined forces with bestselling writers Christopher Golden and Richard Kadrey against two unlikely opponents: ChatGPT’s creator OpenAI and Meta Platforms. The writers filed a copyright infringement (侵犯) case in early July in which they claim their copyrighted books were used without their permission as part of training dataset for ChatGPT and similar AI models.Here’s a critical point to remember: AIs like ChatGPT don’t parrot books word for word. They generate new content based on patterns learned from the training data. The specific words and sentences formed aren’t direct copies from copyrigh ted books, blurring the lines of traditional infringement. I have a vision there’s a slim chance this case will hold up, but the final call is in the hands of the courts.The cornerstone of human-learning is imitation (模仿). The nature of intelligence—whether biological or artificial rests on the ability to recognize patterns and apply them in innovative ways. AI, such as ChatGPT, operates similarly. It learns from its environment—in this case, the extensive databasets of text—and imitates patterns it finds. That’s how it can compose a strikingly human-like string of text despite having no consciousness or creativity.The current case challenges this understanding, claiming that AI’s method of learning breaks copyright law.Some publishers provide a compensation (补偿) strategy. But there are potential issues with this approach. First, its being in effect might pose enormous, even unovercome challenges. The large scale of data that AI models like ChatGPT take in for training thousands of books, millions of articles, and more makes it impractical to track down every single copyright holder and negotiate terms for use. This could result in high expenses for AI developers, potentially preventing innovation and destroying public models.But here’s an interesting para dox (悖论) to consider: The victory of writers against formal AI service providers may not end the issue. Far from it. The outcome of this unfolding drama could be more than a simple courtroom win or loss; it could fundamentally redefine the boundaries of artificial intelligence and copyright law.12. What may be the result of the case in the author’s view?A.AI may get away with it. B.Writers may gain huge benefit.C.AI’s works may be banned.D.Met a platforms may be closed.13. What is Paragraph 3 mainly about?A.The reliance of AI on humans.B.The application of AI’s imitation.C.The role of AI in human learning.D.The common feature of AI and human brain.14. What will the compensation strategy bring about?A.The ceasing of AI development. B.Lack of sustainable quality data.C.The protests from the publishers. D.Financial burdens for AI developers. 15. What does the author intend to do in the last paragraph?A.To clarify his or her stand. B.To present an example.C.To make some comparison. D.To add background information.When it starts to smell like homeIn casual conversations, government documents, and formal job interviews, there is a simple question: “Where are you from?” 16 I could say I am from Peru—my birthplace, or Mexico where I spent the majority of my childhood, or the United States whose culture is deeply rooted into my life.No matter what answer I choose, a small voice whispers in my head: I am not enough to say I am from Peru, Mexico, or the United States. To be from somewhere carries expectations of understanding, accepting, and reforming “your” culture, “your” home. 17 Like dandelion (蒲公英), dragged by the waves of the wind, broken parts of me are spread across the three countries and in three different times, and further torn apart in many more smaller moments.18 They are “going home” for school breaks. As students who frequently move may also understand, I have never seen my living space as “home”. So, does t his mean I do not have, and will never have a home? Yes or so, I thought. I resigned myself to live with this sense of sadness until very recently.When I was walking through a supermarket, a memorable smell of bread drifted into my nose. Whenever Mom and I would stop by the bakery section of HEB, a Mexican supermarket, she would buy me this cheap sausage bread, the kind where the sausage would fall out of it on the first bite and you’re left eating the buttery, salty bread by itself. 19Sadly, even with this inner feeling, nothing outer has changed. I will always feel a sense of loss in not having a physical home to “go back to”. Yet when a smell catches me off guard with the memories it brings, I am lucky enough to feel like I am “at home” in these brief moments. 20Valentina Dominguez, a 9-year-old Plano, Texas, faced every child’s nightmare when she accidentally ______ her beloved American Girl doll, Beatrice, on a plane in Tokyo. Beatrice wasn’t just any ______ she was, as Valentina ______, her “best friend”.The family’s initial efforts to recover Beatrice proved ______. Without losing hope, they ______ to the airline and also posted about the missing doll on Facebook. The family’s prayers were ______ when James Danen, a First Officer with American Airlines, came across the ______. Having flown to Tokyo frequently since 1993, Danen took it upon himself t o help. He said, “It’s my ______. I like helping people... that’s just what I like doing.”Danen ______ the Lost and Found at Tokyo’s Haneda Airport. It took a second attempt, but he was eventually able to ______ the treasured doll. Adding a sprinkle of joy to the journey, Danen ______ Beatrice’s travels, capturing photos of her in various airports and during flights on the way back to Texas.August 21 turned out to be a day of ______ for the Dominguez family. Living only a few miles away, Danen ______ delivered Beatrice to an overjoyed Valentina. The ______ was made even more special with the addition of a large map, ______ the adventurous journey Beatrice had undertaken.21.A.packed B.received C.tore D.left22.A.toy B.present C.classmate D.friend23.A.doubts B.proposes C.describes D.discovers24.A.useful B.fruitless C.innovative D.indefinite25.A.gave in B.reached out C.looked up D.set off26.A.answered B.performed C.recited D.commented 27.A.pilot B.girl C.doll D.post28.A.hobby B.job C.nature D.turn29.A.founded B.surveyed C.managed D.contacted30.A.purchase B.possess C.locate D.label31.A.documented B.canceled C.reserved D.monitored32.A.adventure B.celebration C.learning D.relaxation33.A.personally B.gratefully C.shyly D.frequently34.A.campaign B.participation C.reunion D.transformation 35.A.defining B.admiring C.perceiving D.illustrating阅读下面短文,在空白处填入1个适当的单词或括号内单词的正确形式。

我与版权的故事作文

我与版权的故事作文英文回答:My journey with copyright has been a winding path marked by both flashes of inspiration and moments of uncertainty. From the early days of my creative pursuits, I have grappled with the intricacies of copyright law, seeking to understand how it protects and empowers creators while balancing the need for public access and dissemination of knowledge.Navigating the nuances of copyright can be a daunting task, especially in today's digital landscape where information flows freely and boundaries between personal and public domains blur. Yet, it is precisely in this complex environment that copyright becomes essential, providing a framework for protecting the rights of creators and fostering a vibrant and diverse creative ecosystem.As a creator, I have experienced firsthand theimportance of copyright in safeguarding my intellectual property. From safeguarding my written works to protecting my designs and images, copyright has empowered me tocontrol the use and distribution of my creations, ensuring that they are not misappropriated or exploited without my consent.However, understanding the limitations of copyright has also been a crucial part of my journey. Recognizing the importance of fair use and public domain principles has allowed me to appreciate the delicate balance between protecting creators' rights and ensuring the free flow of information.My evolving understanding of copyright has shaped my approach to creating and sharing my work. I strive to balance the desire for recognition and protection with the recognition that my creations can also contribute to a larger body of knowledge and culture. By embracing the principles of openness and collaboration, I hope to create works that both respect the rights of others and inspire new generations of creators.中文回答:我的版权故事。

short video英文作文

short video英文作文English Answer:Short videos are rapidly gaining popularity due to their brevity, engaging nature, and widespread accessibility. The advent of smartphones and high-speed internet has made it possible to create and share short videos effortlessly. Platforms such as TikTok, Vine, and Instagram Reels have emerged as popular destinations for short video content, attracting a massive audience of viewers.The appeal of short videos lies in their conciseness and immediate gratification. They allow users to quickly consume and digest information, stories, or entertainment without committing significant time or attention. The brevity of short videos also makes them highly shareable, enabling content to spread rapidly across social media platforms.Short videos are also an effective way to connect with audiences on a personal level. They often feature relatable content, such as personal experiences, funny anecdotes, or behind-the-scenes glimpses. This personal touch allows creators to establish a stronger bond with their followers, leading to increased engagement and loyalty.In the context of marketing and advertising, short videos represent a powerful tool to capture attention and drive brand awareness. Brands can use short videos to showcase their products or services, engage with potential customers, and build a positive brand image. The visual nature of short videos makes them particularly effective in conveying messages and evoking emotions.Short videos have significantly impacted the entertainment industry. They have given rise to a new generation of content creators who are pushing the boundaries of storytelling and entertainment. Short-form video series have gained immense popularity, providing viewers with bite-sized episodes that can be consumed on the go.However, the proliferation of short videos also brings with it concerns regarding content quality, privacy, and intellectual property. It is crucial for creators to ensure the quality and accuracy of their content, while platforms must implement effective measures to protect user privacy and combat copyright infringement.中文回答:什么是视频?视频是一种短小精悍的视频,深受大众喜爱。

个人信息删除权之限制

Open Journal of Legal Science 法学, 2023, 11(4), 2097-2102 Published Online July 2023 in Hans. https:///journal/ojls https:///10.12677/ojls.2023.114300个人信息删除权之限制裴浩辰宁波大学法学院,浙江 宁波收稿日期:2023年4月21日;录用日期:2023年5月6日;发布日期:2023年7月7日摘要 个人信息删除权是个人信息主体所具有的一项重要权利,是信息主体基于自身意志决定处理个人信息的具体表现方式,同时也为信息处理者确保信息主体享有其个人信息决定权提供立法保障。

纵观我国民事立法对该项权利具有明确规定。

在《网络安全法》中首次对个人信息删除权进行明确,并在《民法典》第1037条中加以明确细化。

但上述规定都过于笼统。

2021年出台的《个人信息保护法》中第47条对个人信息删除权有所细化,个人信息的保护程度有所提升。

然而在实践中,却存在个人信息删除权滥用的情形,目前立法对哪些情形不能行使个人信息删除权并没有明确规定。

如不对权利的行使进行必要的限制会突破权利的边界。

本文通过比较法上的对比分析,分析论证当哪些情形发生时,应当对个人信息删除权的行使进行必要的限制,确保该项权利得以适当行使。

关键词个人信息,删除权,限制Limitation of the Right to Delete Personal InformationHaochen PeiLaw School of Ningbo University, Ningbo Zhejiang Received: Apr. 21st , 2023; accepted: May 6th , 2023; published: Jul. 7th , 2023AbstractThe right to delete personal information is an important right of the subject of personal informa-tion, which is a specific way for the subject of personal information to decide on the processing of personal information based on his own will, and also provides legislative protection for the in-formation processor to ensure that the subject of information enjoys the right to decide on his own information. Throughout China’s civil legislation, it has clear provisions on this right. The裴浩辰right to delete personal information was first stipulated in the Network Security Law, and was clear-ly refined in Article 1037 of the Civil Code. Article 47 of the Personal Information Protection Law, which was introduced in 2021, has refined the right to delete personal information and increased the level of protection of personal information. However, in practice, there are cases of abuse of the right to delete personal information, and the current legislation does not clearly stipulate the cir-cumstances in which the right to delete personal information cannot be exercised. Without the ne-cessary restrictions on the exercise of the right, the boundaries of the right will be breached. In this paper, we analyze and argue, through comparative analysis, the circumstances in which the right to erasure of personal information should be exercised with the necessary restrictions.KeywordsPersonal Information, Right to Delete, Restrictions Array Copyright © 2023 by author(s) and Hans Publishers Inc.This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0)./licenses/by/4.0/1. 引言互联网作为一项伟大的发明应用,极大的改变了人们的生活方式。

分享电子书英语作文带翻译

分享电子书英语作文带翻译In the digital age, the concept of sharing has taken on new dimensions, especially when it comes to literature and educational materials. E-books, or electronic books, have become a popular alternative to traditional paper books, offering convenience, portability, and often a more interactive reading experience. In this essay, I will discuss the benefits of sharing e-books and the impact it has on readers and the publishing industry.Firstly, sharing e-books is an environmentally friendly practice. With the increasing awareness of the need toprotect our planet, e-books play a crucial role in reducing the consumption of paper and the impact on forests. By sharing e-books, we are not only conserving resources but also reducing our carbon footprint.Secondly, e-books offer a more accessible form of reading for individuals with visual impairments or learning disabilities. Many e-books come with adjustable font sizes, customizable backgrounds, and text-to-speech features that can make reading more comfortable and enjoyable for a wider audience.Moreover, sharing e-books can also foster a sense of community among readers. Online platforms and social media groups dedicated to book sharing allow readers to connect with like-minded individuals, exchange recommendations, and engage in discussions about the books they are reading.However, the sharing of e-books also presents challenges. One of the primary concerns is copyright infringement. It is essential to ensure that e-books are shared legally and ethically to protect the rights of authors and publishers. Many platforms offer legal lending and borrowing services for e-books, which can be a great way to share without violating any laws.In conclusion, sharing e-books is a practice that has the potential to enrich our reading experiences while promoting sustainability and inclusivity. It is crucial to approachthis practice responsibly, respecting the rights of content creators and ensuring that sharing is done within the boundaries of the law.翻译:在数字化时代,分享的概念已经采取了新的维度,尤其是在文学和教育材料方面。

phytomedicine author agreement 模板

phytomedicine author agreement 模板一. IntroductionIn this article, we will discuss and provide a step-by-step guide on the Phytomedicine Author Agreement template. The template aims to outline the key points and responsibilities of authors when submitting their articles to the journal Phytomedicine. By following this agreement, authors can ensure a smooth submission process and adhere to the guidelines set by the journal.II. Agreement Terms1. Title and ScopeThe article should clearly state the title and scope of the research being conducted. This section should provide a concise overview of the study's objectives and its relevance to the field of phytomedicine.2. Authorship and ContributionsAuthors must clearly state their contribution to the research. This includes conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, writing, editing, and funding acquisition. Each author should review and agree to the order of authorship, ensuring it accurately reflects their level of contribution to the study.3. Research Ethics and ComplianceAuthors must declare and comply with all research ethics and compliance guidelines set by their respective institutions. Any potential conflicts of interest, funding sources, and ethical approval for human or animal experiments must be disclosed properly.4. Plagiarism and OriginalityAuthors should ensure that their work is original and has not been previously published elsewhere. Proper citations and references should be provided when using others' work in the research. Any potential plagiarism issues should be addressed and resolved before submission.5. Data Accuracy and ValidationAuthors are responsible for ensuring the accuracy and validity of the data presented in their article. This includes proper statistical analysis, data verification, and reproducibility. Any potential errors or discrepancies should be acknowledged and clarified in the article.6. Intellectual Property RightsAuthors must acknowledge and respect the intellectual property rights of others. If the research involves the use of copyrighted materials, authors should seek permission and properly credit the original creators.7. Manuscript FormattingThe article should adhere to the required formatting guidelines of Phytomedicine. This includes font size, line spacing, referencing style, and manuscript length. Authors should carefully review and follow the journal's instructions for manuscript preparation.8. Copyright TransferAuthors will be required to transfer the copyright of their article to Phytomedicine upon acceptance for publication. This allows the journal to protect and distribute the work within the legal boundaries of copyright law.9. Open Access and LicensingAuthors may have the option to publish their article under an open access license. This allows for wider dissemination and accessibility of the research. Authors should carefully review and agree to the terms of the chosen open access license, if applicable.III. ConclusionIn this article, we have provided a step-by-step guide on the Phytomedicine Author Agreement template. By following this agreement, authors can ensure a smooth submission process and adhere to the guidelines set by the journal. It is essential for authors to carefully review and comply with each term of the agreement to promote ethical research practices and facilitate the publication of their work in Phytomedicine.。

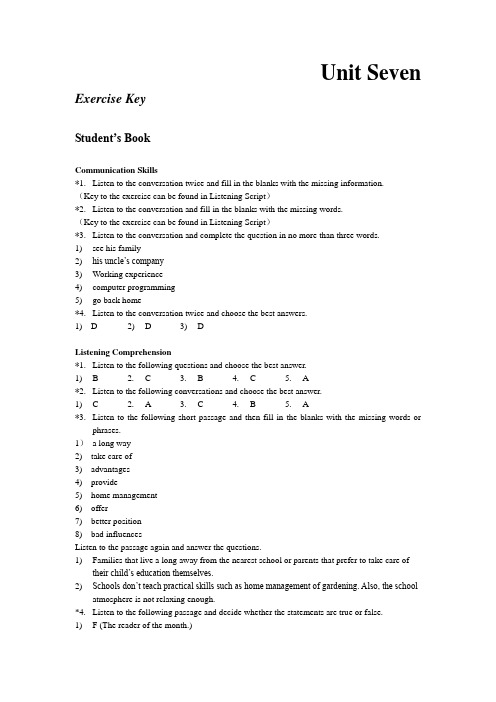

英语习题答案Unit7

Unit Seven Exercise KeyStudent’s BookCommunication Skills*1. Listen to the conversation twice and fill in the blanks with the missing information.(Key to the exercise can be found in Listening Script)*2. Listen to the conversation and fill in the blanks with the missing words.(Key to the exercise can be found in Listening Script)*3. Listen to the conversation and complete the question in no more than three words.1) see his family2) his uncle’s company3) Working experience4) computer programming5) go back home*4. Listen to the conversation twice and choose the best answers.1) D 2) D 3) DListening Comprehension*1. Listen to the following questions and choose the best answer.1) B 2. C 3. B 4. C 5. A*2. Listen to the following conversations and choose the best answer.1) C 2. A 3. C 4. B 5. A*3. Listen to the following short passage and then fill in the blanks with the missing words or phrases.1)a long way2) take care of3) advantages4) provide5) home management6) offer7) better position8) bad influencesListen to the passage again and answer the questions.1) Families that live a long away from the nearest school or parents that prefer to take care oftheir child’s education themselves.2) Schools don’t teach practical skills such as home management of gardening. Also, the schoolatmosphere is not relaxing enough.*4. Listen to the following passage and decide whether the statements are true or false.1) F (The reader of the month.)2) F (She is in the 5th grade of Harvey Primary School.)3) T (She lives with her mom, dad, and three brothers.)4) F (Through reading, she can visit new places, travel to different periods of time, and learnabout other people.)5) F (It can be inferred from the last sentence that this is a speech given at a celebration.)Text A*2. Answering Questions1) Mrs. Bush admired her second grade teacher Miss Gnagy so much that she wanted to becomea teacher like her one day.2) She would create her own imaginary classroom in which to teach her dolls.3) She felt that she was unprepared for the job, and she felt that it was more difficult than shehad imagined.4) With a group of students -- both quiet and fidgety children, and a class clown, Mrs. Bush hadto find ways to direct class so that all the students received the attention they needed.5) As a teacher, Mrs. Bush found that students had different levels of interest, energy, andattention. She realized that she had a rather short amount of time to teach important skills to her students, skills that she believed they would use throughout their lives.6) Although Mrs. Bush had instruction to teach students to read, she did not know how to put itin to practice.7) A) Witnessing a child’s development into a young reader; B) watching students’ eyes light upwith understanding; C) knowing that she was playing some part in ensuring their future success.8) A) Some students have an advantage by having strong pre-reading skills when they enterschool. B) New studies show success in early school strongly correlates to how often parents have spent time with their children on reading and language activities.9) Repetition of the rhythm of speech is important to help the developing brain understand howlanguage is organized.10) Reading motivates and inspires and sparks the imagination in a way that television cannot.Language Focus*1. Words1)technique2)beyond3)appreciate4)meaningful5)relatively6)ensure7)amount8)obvious9)success10)totally★2. Phrases1)work its spell on2)in practice3)be sure of4)admired John for5)One day6)in public7) In a way8) make much difference9)play an important part in10) light up★3. Structure1) The researchers say this makes the test cheap enough to be used in developing countries.2) He said it was the first time he had seen the enemy close enough to shoot at.3) You need a roof strong enough to support the weight of a small garden.4) The doctors say Mr. Smith should be well enough to carry out his duties as president of thecommittee after the operation.5) He says they will be able to create a medicine that is strong enough to prevent the disease.6) Some women's groups felt the meeting did not go far enough to guarantee women's rights.★4. Word Formation1)enclosed2)enable3)enrich4)encourages5)endangering6)enlarge★5. Translation1) The government urges the public to play a part in caring for the poor in our society.2) Your technique in public relations will one day be recognized.3) In a way, the impact of education on children is something that many people don't appreciate.4) How often parents spend time on reading with their very young children makes a hugedifference in childhood development.5) You must be sure of what you want to achieve before you sit down and talk with them.6) Nursery rhymes can be meaningful as they can stretch the boundaries of imagination forchildren.Translate the following sentences into Chinese.3)尽管拥有教育学学位并有过教学实习,我还是感到没有做好充分的教学准备——这工作比我预料的要艰难得多。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Westlaw UK Delivery SummaryRequest made by: IPUSERCP3395681957IPUSERCP3395681957Request made on: Saturday, 19 July, 2008 at 03:02 BSTClient ID: kclkkxj4157Title: The boundaries of copyright: its properlimitations and exceptions: internationalconventions and treatiesDelivery selection: Current DocumentNumber of documents delivered: 1© 2008 Sweet & Maxwell LimitedIntellectual Property Quarterly1999The boundaries of copyright:its proper limitations and exceptions:international conventions and treatiesSam RicketsonSubject: Intellectual property. Other related subjects: International lawKeywords: Copyright; International law*I.P.Q.56 1.INTRODUCTIONThe purpose of this paper is to sketch the international framework against which the topic of exceptions and limitations to copyright protection falls to be considered. As will be seen, this framework is far from precise or complete in the prescriptions which it contains. Furthermore, matters of fundamental principle are more frequently hinted at, or left as a matter for implication, rather than contained in clear and unambiguous statements. This is particularly so when one comes to consider the limitations and exceptions which can be made to protection. Nonetheless, the international framework sets the broad parameters within which policy makers and legislators at the national level must work; while other policies and purposes will be relevant, no nation can depart lightly, and without some attempt at principled justification, from the obligations they have assumed under international instruments relating to the protection of authors' rights.2.SCOPE OF THE PAPERIn the discussion which follows, I have focused on the following international conventions and agreements, both existing and proposed:• the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works 1886, as amended up to the Paris Act 1971;• the Agreement relating to Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights 1995 (the “ TRIPs Agreement” ); • the W.I.P.O. Copyright Treaty, Geneva, 1996.*I.P.Q.57 The membership of the first two is now so extensive that it covers virtually all nation states in the developed, developing and former socialist bloc categories; the third, while not yet in force, is the focus of present policy making at the national level in most of these countries. An omission from the above list is the Universal Copyright Convention 1952, as amended in Paris 1971. This has been done on the (possibly) arbitrary assumption that this Convention no longer remains of direct relevance in light of the wide coverage of the Berne Convention and TRIPs Agreement.3.SOME GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS1Although there are markedly different philosophical and policy attitudes that underlie national copyright laws, almost all laws are familiar with the concepts of “ exclusive rights” , “ compulsory licences” and “free uses” . Historically, authors' rights have been defined as exclusive rights, meaning rights to exclude third parties from the use covered by the right in question. Thus, if third parties wish to use protected material, they must seek the permission of the owner, make such payment as is required, and use the work in accordance with any conditions laid down by the owner. In civil law countries, this exclusive formulation of rights would seem to have some natural law backing, in the sense that the legal prescriptions in such systems can be seen as giving effect to rights already existing in nature, with the logical consequence that these rights should therefore be of perpetual duration and universal in character. While this is not, in fact, the case under any existing national law, it seems true to say that, under such an approach, the author is viewed as the subject or focus of rights, which should therefore be framed in as absolute a manner as possible. Exceptions or limitations to these rights should accordingly only be made in unusual or extraordinary circumstances, with the onus being upon those seeking the exception or limitation to establish their case in the clearest and most unambiguous way. In common law systems, however, authors' rights have usually been viewed in a more instrumentalist fashion, as a means of advancing and achieving certain desired and desirable social and economicgoals. As a consequence, the grant of exclusive rights is more usually viewed as a device for achieving ulterior goals, such as the advancement of learning, the progress of science, and wider economic and social development. This approach was apparent in the preamble to the first modern British copyright law (the Statute of Anne 1709):“ An Act for the Encouragement of Learning, by Vesting the Copies of Printed Books in the Authors or Purchasers of such Copies, during the Times therein mentioned.”Likewise, in the United States, the Congress was empowered under the Constitution “ to promote the progress of science and the useful arts, by securing for limited times *I.P.Q.58 to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries” .2Under instrumentalist approaches of this kind, exceptions or limitations to protection are more readily justified, in that interests other than those of individual creators are given a more equal weighing with those of authors. In other words, the laws of these countries are predicated as involving a balancing of competing interests, a process which has been described by Professor Goldstein as a “ calculus” of both private and public benefit.3 Indeed, the balancing of interests seems to be unavoidable under any copyright law, even those in which the exclusive rights of authors are apparently given a more central place. The following reasons can be advanced for this:1. The continuing impact of technological development, which makes the administration and enforcement of exclusive rights more difficult, perhaps even impossible, and makes the recognition of lesser rights to remuneration, or even free use, more acceptable. In economists' terms, transaction costs become over-whelming, and individual right owners are incapable of identifying and negotiating with those who are using their material. Hence, collective solutions and/or compulsory licences appear to be the most acceptable way of resolving this problem, on the basis that “ half a loaf of bread is better than none at all” . However, the balance sheet is not entirely one-sided in this regard, as technological advances can also bring great benefits to authors, both in the shape of new modes of exploitation and in the reduction of transaction costs that is sometimes made possible by the use of new communications and computer technologies.2. The fact that there are some uses and applications of copyright works which are truly de minimis or incidental in character, and can lead to no measurable detriment to the interests (economic and non-economic) of authors. For copyright laws to insist upon “ capturing” the fruits of such uses would add unacceptably to transaction costs, and might lead ultimately to a reduction in creative activity.3. The fact that some other uses and applications of copyright works have always been regarded as possessing a social or cultural significance to which the interests of authors should be deferred. As will be seen below, even the Berne Convention has long acknowledged the existence of such claims in the areas of education and reporting of news. More recently, the claims of developing countries have been accepted as justifying the curtailment of authors' exclusive rights in particular circumstances. Others are clearly possible.In all national copyright systems, it will be clear that the notion of exclusive rights is under considerable pressure. Questions of principle and practicality become readily mixed, as one tries to determine how rights should be reformulated or modified, and there can be no doubt that the emphasis of particular countries will differ according to *I.P.Q.59 whether they fall within what may be crudely described as “ authors' rights” regimes or instrumentalist regimes. Yet under both approaches (and any falling in between), it will become necessary, at some point, to accept limitations or abridgments of exclusive rights, either in the form of some kind of compulsory licensing system or free use provision. In this regard, “ compulsory licence” refers to any mechanism under which third parties can have access to copyright material upon payment of a stipulated fee or royalty. The net effect of such schemes is that the right is question loses its exclusive character, and becomes limited to a right to remuneration, with the owner no longer having the untrammelled right to control the identity of those using her work or the conditions under which this occurs (these might be termed “ limitations” to copyright). “ Free use” , on the other hand, can be simply explained as any provision which provides for unauthorised use by third parties without payment, although it may be subject to other conditions such as precise quantitative restrictions, careful limitations as to purpose, requirements of sufficient acknowledgment, and so on (such uses could be described as “ exceptions” to copyright, rather than limitations). When does one move along the spectrum from “ exclusive right” at one end through “ remuneration right” to “ free use”at the other? Economic considerations suggest certain guidelines that can be taken as a starting point: 1. No exclusive right, however precious, will be worth maintaining unless it is capable of being administered or enforced. In economic terms, this will occur when it becomes difficult to recover some at least of the externalities or free rider effects created by the use, or when the costs of transactingpermissions outstrip the fees that the user is prepared to pay.2. In the event that these circumstances arise, collective administration may then represent a viable alternative, although inevitably this involves a diminution of the exclusive right in question as the individual's interest is absorbed into that of the collective.3. Transmutation of the exclusive right into a right to remuneration represents an attempt to approximate what would otherwise be freely negotiated by the rights owner (whether individually or collectively) and the user. In economic terms, this means that there must be some kind of market breakdown or market failure before compulsory licensing should be adopted.4There must exist externalities which arise from the use in question, or transaction or other costs, which the parties cannot deal with in their bargaining, even collectively. It is only in these circumstances that regulated solutions should be adopted, and, even then it is always an uncertain enterprise to attempt simulated market solutions. Furthermore, such solutions should not be set in concrete, as circumstances can change rapidly, for example, with the introduction of new technologies which can now reduce transaction and information seeking costs in ways unthought of even a short time ago.*I.P.Q.60 4. Free use provisions should only arise where the benefit of allowing the use in question outweighs the losses to the right owner and where transaction costs would otherwise prevent a negotiated licence. By way of illustration, Professor Goldstein gives the example of the use of a short extract of a work for the purposes of a review in a newspaper or magazine. This has some value to the copyright owner as well as to the public, and it is likely that the use would not occur if the newspaper or magazine had to sustain the necessary transaction costs required to obtain permission. Accordingly, so long as the value of the proposed use outweighs the value of any alternative use that is foreclosed, it is sensible to allow this as a free use.5Economic considerations cannot be applied exclusively in determining the matters referred to above; at the same time, they provide a useful starting point for analysis. It then remains to add in the other values or interests of a more public kind that should be included in the calculus, for example, educational and literacy concerns, religious and social requirements, the needs of economic and cultural development, and so on. These will all be matters on which individuals and nations will have differing views, but ultimately both private and public benefit will need to be weighed in the balance in determining where the dividing lines between exclusive rights, compulsory licences and free use respectively should be drawn. It must be acknowledged, from the outset, that these matters are only incompletely addressed in the international instruments that provide the present framework for national laws, and some of the gaps have been filled in by the use of commonsense constructions and the technique of implication. Moreover, very recent developments have seen a move towards greater coherence in approach, involving the articulation of broad criteria rather than the continued accumulation of specific exceptions and limitations. It remains to be seen, however, whether these developments will really meet the challenges now posed by converging technologies and digital networks.4.THE INTERNATIONAL FRAMEWORK--GENERAL PRINCIPLESAt both the national and international levels, it has become the practice in recent years to begin with broad statements as to the objectives sought to be achieved by the particular instrument under consideration. In my own country, Australia, this has almost become something of an art form, as successive amendments to legislation will commence with a useful list of objectives or reasons for the adoption of the particular measure, followed by a mass of detailed provisions which often make it easy to lose sight of those objectives.6 In the European Union, an obvious parallel is to be found in *I.P.Q.61 the weighty list of “ whereas” statements which appear in the preambles to Directives and which may often exceed in length the specific provisions of the Directive.7International agreements in the area of copyright have tended to be more economical in this regard, but general statements of reasons and objectives in a preamble or the like can nonetheless be of considerable assistance in interpreting and applying the specific obligations contained in such agreements.8 In the case of the Berne Convention, this is a matter of elegant simplicity: the preamble states that this is a Convention which has been “ animated by the desire [on the part of countries of the Union] to protect, in as effective and uniform a manner as possible, the rights of authors in their literary and artistic works” . Nothing more is said, and there is no reference to any other competing principle or concern. At the time of its formation (in 1884-1886), this is understandable enough, given that the Berne Convention was the culmination of a long series of efforts to bring about a multilateral arrangement for the protection of authors' rights that would replace the previous piecemeal and incomplete network of bilateral agreements.9 At the same time, it is worth noting that, even at this time, and within the civil law countries which constituted the vast majority of original Berne signatories, it was recognised that therewas a need for there to be some restrictions or limitations upon the exercise of authors' rights in particular situations. These matters were raised in several of the sessions of the 1884-1886 Diplomatic Conferences that had preceded the formation of the Convention, where concerns over translation rights and the need for more general exceptions or limitations for particular purposes such as teaching, instruction and news reporting was raised by a number of delegates.10 In addition, Numa Droz, the distinguished Swiss official who presided over the first diplomatic conference in 1884, reminded delegates in his closing speech that “limitations on absolute protection are dictated, rightly in my opinion, by the public interest” .11 He went on to state that:“ The ever-growing need for mass instruction could never be met if there were reservation of certain reproduction facilities, which at the same time should not generate into abuses. These were the various viewpoints and interests that we have sought to reconcile in the draft Convention ”12In consequence, it was accepted, even from the outset, that there was a need for the new Convention to strike a balance between authors' rights and the competing public *I.P.Q.62 interests of education, news reporting and the like. As will be seen below, from its original version and through its subsequent revisions, the Berne Convention has come to contain a number of express and implied exceptions to, and limitations on, the exclusive rights of authors, although it is, perhaps, difficult to enunciate any coherent principle or criteria on which these exceptions or limitations are based.By contrast, the W.I.P.O. Copyright Treaty adopted in 1996 is more explicit about such matters. While its preamble begins by reiterating the desire of members to “ develop and maintain the protection of the rights of their authors in their literary or artistic works in a manner as effective and uniform as possible” , it goes on to state that members also recognise (among a list of other things, including the need to adopt to the changing technological environment):“ the need to maintain a balance between the rights of authors and the larger public interest, particularly education, research and access to information, as reflected in the Berne Convention, ”Likewise, in the TRIPs Agreement, while emphasising the need to reduce distortions and impediments to international trade, the preamble states the need for Contracting States to recognise, among other things:“ that intellectual property rights are private rights;[and]the underlying public policy objectives of national systems for the protection of intellectual property, including developmental and technological objectives;” .Both these later instruments, therefore, acknowledge directly the need for there to be limits to protection and this obviously takes us to the central concern of this paper, namely what latitude is allowed by the present international framework governing the protection of authors' rights to take account of these other interests? To what extent may authors' rights be made subject to exceptions and limitations?5.THE PRESCRIPTIONS OF THE BERNE CONVENTION13This is obviously the starting point. While the number of exceptions and limitations provided under the Berne Convention is relatively small, directly or indirectly they can be justified by reference to the kind of criteria discussed above. For purposes of analysis, they can be categorised as follows:*I.P.Q.63 1. Provisions excluding protection altogether in the case of particular categories of works. 2. Provisions (both express and implied) permitting free use for particular kinds of purposes or in particular circumstances.3. Provisions permitting certain uses subject to payment of remuneration to the copyright owner (compulsory or obligatory licences).These are examined in more detail below.Provisions excluding protection altogether in the case of particular categories of works These provisions apply to those limited categories of works where claims of authorship and exclusivity might be thought to be secondary to the predominant public purpose that such works serve. For this reason, official texts of a legislative, administrative and legal nature, and official translations of these texts may be denied protection under national laws: Article 2(4). In the same way, protection is denied to “news of the day”and “miscellaneous facts having the character of mere items of pressinformation” : Article 2(8). Finally, Member States are free to determine for themselves the copyright status of political speeches and speeches delivered in the course of legal proceedings: Article 2bis (1). In the first and third of these exceptions, the Convention is permissive: countries may provide for the exclusion of protection if they wish, but not all do so by any means.14 In the second case, however, the exception appears to be mandatory, although its correct interpretation is probably more restricted than might at first appear. Thus, it does not withhold protection from the writings of journalists and reporters, but only with respect to the facts or items of news which they recount. Viewed in this way, it is no more than a restatement of the basic proposition that copyright does not extend to the protection of ideas and information per se, which has now been expressly adopted as Article 2 of the W.I.P.O. Copyright Treaty 1996. As such, Article 2(8) of Berne is probably unnecessary, but it serves to underline this basic principle of copyright law. Although this interpretation is arguable, it seems to find support in the various background papers of the various revision conferences of the Berne Convention, most recently at the time of the Stockholm Revision Conference.15At the same time, such an exclusion can be readily supported by reference to the public interest in the free flow of information.*I.P.Q.64Provisions permitting free use for particular kinds of purposes or inparticular circumstancesThere are a number of provisions which are of interest here. The first three are of a fairly specific character; the fourth is more general in its scope. In addition, underpinning these are a number of implied limitations which may be taken advantage of by Member States, as well as an exception relating to cinematographic work and certain other restrictions (express and implied) relating to matters of public order and restrictive trade practices.Rights of quotationQuotation of short passages of works has generally been seen in national laws as a permissible use. In the example given above by Professor Goldstein, such usages are usually of advantage to the copyright owner (in bringing knowledge of the work to a wider public), the loss to the copyright owner is minimal in the sense that no alternative use of the work is thereby foreclosed, and the transaction costs involved in obtaining permission would usually lead to no use occurring if permission were required. In addition, other obvious public benefits from allowing free rights of quotation can be readily postulated, including the promotion of critical discussion, the free circulation of ideas, and the general enhancement of scientific and intellectual discourse. Article 10(1) of the Convention contains reasonably generous boundaries within which such usage may occur, providing that it is permissible to make quotations from a work which has been “ lawfully made available to the public so long as their making is compatible with fair practice and their extent does not exceed that justified by the purpose ” . This provision has only been in the Convention since the Brussels Revision of 1948 and its present form dates from the Stockholm Revision of 1967. However, there has been some provision for the making of quotations in the Convention from the outset, although there was continuing debate about the scope of such an exception.16As noted above, the scope of the present Article 10(1) is generous:1. It is not limited to “ published works” , but extends to works “ lawfully made available to the public” . The latter phrase is wide enough to include works which have been disseminated by means of public performance or broadcasting, although neither forms of dissemination would fall within the scope of publication under Article 3(3). It would also apply to works which have been made available pursuant to some kind of compulsory licence provision (another question, of course, would be whether the making of copies under such a provision would itself be within the parameters of the Convention, as to which see below).*I.P.Q.65 2. Although the act of “ quotation” usually arises in the context of reproduction rights, there is nothing in Article 10(1) to indicate that it is so limited. Accordingly, it extends to quotations made in the course of non-material disseminations of a work, such as public performance, recitation or broadcasting.3. No limitation is placed on the amount which may be taken: this is left as a matter to be determined in each case, subject to the general criteria of purpose and fair practice. In some instances, for example, quite lengthy quotations may be justified in order to ensure that it is presented properly, as in the case of critical review or work of scholarship. In others, quotation of the whole work may be justified, as in the example given by Professor Nordemann of a commentary on the history of twentieth century art where representative pictures of particular schools of art would be required by way of illustration.174. It applies generally to “ works” , not simply to one or more categories such as literary works.5. The making of the quotation must be “compatible with fair practice” . Little guidance as to the meaning of this expression is to be found in the discussions at the Stockholm Conference,18 and it is clear that what is “fair practice”may depend upon the particular case. However, it also seems reasonable to suppose that the criteria referred to in Article 9(2) (discussed below) are equally applicable here, namely that the quotation will be “ fair” if it does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author. As noted below, in certain circumstances this may permit the imposition of compulsory licences.6. No guidance is provided as to the kinds of purpose that are relevant to satisfy the requirement that the quotation must “ not exceed that justified by the purpose” . No list of suitable purposes was included at the time of the Stockholm Revision because of the difficulties of making such a list exhaustive. However, it seems clear from the preparatory work for the Revision and from the discussions in Main Committee I of that Conference that quotation for “scientific, critical, informatory or educational purposes”are within the scope of the Article19; use for judicial, political (perhaps satirical?) and entertainment purposes have also been suggested as appropriate,20as has quotation for “artistic effect” .21 Article 10(1) also makes reference to one particular kind of quotation, namely quotation from newspaper articles and periodicals in the form of press summaries. This reference is difficult to understand, as the making of a summary is not the same thing as the making of a quotation, and this appears to be a remnant of a provision of an earlier text of the Convention.22*I.P.Q.66 7. Any quotation that occurs in accordance with Article 10(1) requires explicit protection of the author's right of attribution: mention must be made of the source and the name of the author, if it appears on the work.23 No explicit mention is made of integrity rights, but it would hardly be consistent with “ fair practice” if an author were quoted out of context, inaccurately or the extract was edited in some inappropriate way.Use for teaching purposesEducational use of copyright material is clearly one of those uses where a strong public interest can be placed in the balance against the private interests of the copyright owner. Nonetheless, the scale of such usage can clearly have profound effects on the owner's pecuniary and non-pecuniary interests, particularly where the work in question has been written with an educational purpose and audience in mind. In such cases, it can be forcefully argued that the copyright owner should not have to subsidise educational activities, however worthy the latter may be. Educational use of copyright material has therefore been a highly contentious issue in most countries. This has also been the case with the Berne Convention, Article 10(2) of which deals with particular kinds of usage which can be made for “ teaching purposes” . This provision leaves it to national law, or to any special agreements existing, or to be concluded, between Union members, to permit:“ the utilisation, to the extent justified by the purpose, of literary or artistic works by way of illustration in publications, broadcasts or sound or visual recordings for teaching, provided that such utilisation is compatible with fair practice” .The origins of this provision are to be found in the original 1886 text of the Convention,24 but the range and magnitude of permitted uses25 is now considerably wider. Thus, it extends beyond utilisations in printed form ("?ublications”) to broadcasts and sound and visual recordings. There is also no necessary quantitative limitation on the amount that may be utilised, as was the case with earlier versions of the provision which referred to “ portions” and “ extracts” . Thus, the provision is more open-ended, and might include the use of the whole of a work in appropriate circumstances, subject to the conditions that this be only to the extent that this is necessary “ by way of illustration for teaching”and is “ compatible with fair practice” . Thus, in the case of works such as pictures or short poems, the use of the whole might be justified, but this would clearly not be so in the case of longer works. The word “ illustration” is clearly of vital significance here, and it would be difficult to argue in the case of longer works *I.P.Q.67that the use of the whole could be justified “by way of illustration for teaching purposes” .26 In this regard, it should also be noted that “ teaching” is to be interpreted in a restrictive fashion, and does not extend to instruction outside the normal primary, secondary and tertiary sectors. That is, it would not include uses in adult education and other public educational activities.27Finally, while Article 10(2) contains no limit on the number of copies that may be made in the case of publications and sound or visual recordings, the making of such multiple copies, even if justified by teaching purposes, will need to be compatible with “ fair practice” . As in Article 10(1), the concept of “ fair practice” is not defined, but it seems reasonable to apply the criteria referred to in Article 9(2), namely that it does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author. In certain circumstances, this might extend to justifying。