英文文献及中文翻译撰写格式

毕业论文外文翻译格式【范本模板】

因为学校对毕业论文中的外文翻译并无规定,为统一起见,特做以下要求:1、每篇字数为1500字左右,共两篇;2、每篇由两部分组成:译文+原文.3 附件中是一篇范本,具体字号、字体已标注。

外文翻译(包含原文)(宋体四号加粗)外文翻译一(宋体四号加粗)作者:(宋体小四号加粗)Kim Mee Hyun Director, Policy Research & Development Team,Korean Film Council(小四号)出处:(宋体小四号加粗)Korean Cinema from Origins to Renaissance(P358~P340) 韩国电影的发展及前景(标题:宋体四号加粗)1996~现在数量上的增长(正文:宋体小四)在过去的十年间,韩国电影经历了难以置信的增长。

上个世纪60年代,韩国电影迅速崛起,然而很快便陷入停滞状态,直到90年代以后,韩国电影又重新进入繁盛时期。

在这个时期,韩国电影在数量上并没有大幅的增长,但多部电影的观影人数达到了上千万人次。

1996年,韩国本土电影的市场占有量只有23.1%。

但是到了1998年,市场占有量增长到35。

8%,到2001年更是达到了50%。

虽然从1996年开始,韩国电影一直处在不断上升的过程中,但是直到1999年姜帝圭导演的《生死谍变》的成功才诞生了韩国电影的又一个高峰。

虽然《生死谍变》创造了韩国电影史上的最高电影票房纪录,但是1999年以后最高票房纪录几乎每年都会被刷新。

当人们都在津津乐道所谓的“韩国大片”时,2000年朴赞郁导演的《共同警备区JSA》和2001年郭暻泽导演的《朋友》均成功刷新了韩国电影最高票房纪录.2003年康佑硕导演的《实尾岛》和2004年姜帝圭导演的又一部力作《太极旗飘扬》开创了观影人数上千万人次的时代。

姜帝圭和康佑硕导演在韩国电影票房史上扮演了十分重要的角色。

从1993年的《特警冤家》到2003年的《实尾岛》,康佑硕导演了多部成功的电影。

外文翻译规范要求及模版格式

外文翻译规范要求及模版格式

外文中文翻译规范要求及模板格式可以根据具体需求和要求有所不同,以下是一般常见的外文中文翻译规范要求及模板格式:

1.规范要求:

-符合语法、语言规范和语义准确性;

-译文流畅自然,符合中文表达习惯;

-忠实准确地传达原文信息;

-注意统一使用特定的术语翻译;

-文章结构、段落、标题等要与原文一致;

-保持适当的篇幅,不过度增加或删减内容;

-遵守保密原则。

2.模板格式:

-文章标题(与原文保持一致,可放在正文上方);

-标题(与原文保持一致);

-段落(与原文保持一致,首行缩进);

-字体(常用宋体或黑体,一般字号12或14);

-行间距(一般1.5倍,可根据需要调整);

-页边距(上下左右均为2.5厘米);

-段落间距(一般1.5倍,可根据需要调整);

以上是一般常见的外文中文翻译规范要求及模板格式,具体要求和格式可以根据具体的翻译项目和要求进行调整。

在翻译过程中,保持准确、流畅、专业是非常重要的。

外文翻译与文献综述模板格式以及要求说明

外文翻译与文献综述模板格式以及要求说明

外文中文翻译格式:

标题:将外文标题翻译成中文,可以在括号内标明外文标题

摘要:将外文摘要翻译成中文,包括问题陈述、研究目的、方法、结果和结论等内容。

关键词:将外文关键词翻译成中文。

引言:对外文论文引言进行翻译,概述问题的背景、重要性和研究现状。

方法:对外文论文方法部分进行翻译,包括研究设计、数据采集和分析方法等。

结果:对外文论文结果部分进行翻译,介绍研究结果和统计分析等内容。

讨论:对外文论文讨论部分进行翻译,对研究结果进行解释和评价。

结论:对外文论文结论部分进行翻译,总结研究的主要发现和意义。

附录:如果外文论文有附录部分,需要进行翻译并按照指定的格式进行排列。

文献综述模板格式:

标题:文献综述标题

引言:对文献综述的背景、目的和方法进行说明。

综述内容:按照时间、主题或方法等进行分类,对相关文献进行综述,可以分段进行描述。

讨论:对综述内容进行解释和评价,概括主要研究成果和趋势。

结论:总结文献综述,概括主要发现和意义。

要求说明:

1.外文中文翻译要准确无误,语句通顺流畅,做到质量高、符合学术

规范。

2.文献综述要选择与所研究领域相关的文献进行综述,覆盖面要广,

内容要全面、准确并有独立思考。

4.文献综述要注重整体结构和逻辑连贯性,内容要有层次感,段落间

要过渡自然。

5.外文中文翻译和文献综述要进行查重,确保原文与译文的一致性,

并避免抄袭和剽窃行为。

英译汉格式规范

英译中翻译格式规范I 格式规范1. 如非引用英文原文,则译稿中中文的标点应全部为中文全角字符标点。

2. 多个词组并列时,英文中的“,”为中文中的“、”,英文中的省略号“…”应为六个字符的中文省略号“……”,左括号和右括号也都应为中文全角括号“(”和“)”3. 数字和金额可以加分节号“,”(如5,000),也可以不加,但在全文中应统一。

4. 译文中中文的字体形式应与英文原文尽量一致,例如原文用粗体、斜体(但文献标题除外)或加下划线,则译文应也用粗体、斜体或加下划线;5. 数值范围的表示形式可以采用110 kV~220 kV,也可以采用110~220 kV,但在原文中应统一;注意:数字和波浪线之间没有空格,而数字与单位之间要加一个空格,但“°C”、“°F”和“%”除外;6. 公式中的符号从“插入公式”中选择;7. 原文中用斜体表示的书籍、手册、期刊及报纸名称,大型音乐会作品曲名,戏曲及电影剧名,广播电视节目名称或诗歌标题,在译文中应使用书名号“《》”8. 全文统一采用宋体,英文字母或阿拉伯数字采用Times New Roman字体;9. 当翻译合同或招投标文件时,“定义与解释”一条中首字母全部为大写的术语(如The Owner, The Supplier等),在译成中文时应用双引号突出(“业主”、“供货商”)。

10. 一级标题和二级标题应用不同字号区别开,例如一级标题可采用2或3号字,二级标题可以用四号或小四;11. 正文采用小四或五号字。

12. 翻译中,数字应重点关注,均应与原文核对;13. 译文的章节与条款编号,应与原文一致,有问题提出;14. 直径符号φ的输入方法:插入,符号,字体选择Symbol,然后选择输入φ,并采用斜体;II 术语和表达规范1. 原文中的“General”,一般译为“概述”。

如果是标准或规范,一般译为“一般规定”或“总则”,其余视情况处理;2. 缩写词首次出现(整个文件中第一次出现)时要译出,此后用缩写;3. 原文中的单位符号、公式等可直接引用,单位(如cm2)不必再译为中文;4. 原文中的人名不译出。

毕业设计(论文)外文资料和译文格式要求(模板)

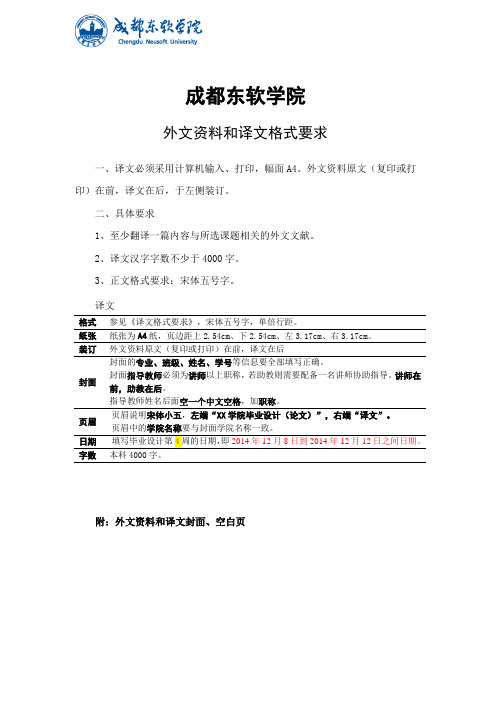

成都东软学院外文资料和译文格式要求一、译文必须采用计算机输入、打印,幅面A4。

外文资料原文(复印或打印)在前,译文在后,于左侧装订。

二、具体要求1、至少翻译一篇内容与所选课题相关的外文文献。

2、译文汉字字数不少于4000字。

3、正文格式要求:宋体五号字。

译文格式参见《译文格式要求》,宋体五号字,单倍行距。

纸张纸张为A4纸,页边距上2.54cm、下2.54cm、左3.17cm、右3.17cm。

装订外文资料原文(复印或打印)在前,译文在后封面封面的专业、班级、姓名、学号等信息要全部填写正确。

封面指导教师必须为讲师以上职称,若助教则需要配备一名讲师协助指导。

讲师在前,助教在后。

指导教师姓名后面空一个中文空格,加职称。

页眉页眉说明宋体小五,左端“XX学院毕业设计(论文)”,右端“译文”。

页眉中的学院名称要与封面学院名称一致。

字数本科4000字。

附:外文资料和译文封面、空白页成都东软学院外文资料和译文专业:软件工程移动互联网应用开发班级:2班姓名:罗荣昆学号:12310420216指导教师:2015年 12月 8日Android page layoutUsing XML-Based LayoutsW hile it is technically possible to create and attach widgets to our activity purely through Java code, the way we did in Chapter 4, the more common approach is to use an XML-based layout file. Dynamic instantiation of widgets is reserved for more complicated scenarios, where the widgets are not known at compile-time (e g., populating a column of radio buttons based on data retrieved off the Internet).With that in mind, it’s time to break out the XML and learn how to lay out Android activities that way.What Is an XML-Based Layout?As the name suggests, an XML-based layout is a specification of widgets’ relationships to each other—and to their containers (more on this in Chapter 7)—encoded in XML format. Specifi cally, Android considers XML-based layouts to be resources, and as such layout files are stored in the res/layout directory inside your Android project.Each XML file contains a tree of elements specifying a layout of widgets and their containers that make up one view hierarchy. The attributes of the XML elements are properties, describing how a widget should look or how a container should behave. For example, if a Button element has an attribute value of android:textStyle = "bold", that means that the text appearing on the face of the button should be rendered in a boldface font style.Android’s SDK ships with a tool (aapt) which uses the layouts. This tool should be automatically invoked by your Android tool chain (e.g., Eclipse, Ant’s build.xml). Of particular importance to you as a developer is that aapt generates the R.java source file within your project, allowing you to access layouts and widgets within those layouts directly from your Java code. Why Use XML-Based Layouts?Most everything you do using XML layout files can be achieved through Java code. For example, you could use setTypeface() to have a button render its textin bold, instead of using a property in an XML layout. Since XML layouts are yet another file for you to keep track of, we need good reasons for using such files.Perhaps the biggest reason is to assist in the creation of tools for view definition, such as a GUI builder in an IDE like Eclipse or a dedicated Android GUI designer like DroidDraw1. Such GUI builders could, in principle, generate Java code instead of XML. The challenge is re-reading the UI definition to support edits—that is far simpler if the data is in a structured format like XML than in a programming language. Moreover, keeping generated XML definitions separated from hand-written Java code makes it less likely that somebody’s custom-crafted source will get clobbered by accident when the generated bits get re-generated. XML forms a nice middle ground between something that is easy for tool-writers to use and easy for programmers to work with by hand as needed.Also, XML as a GUI definition format is becoming more commonplace. Microsoft’s XAML2, Adobe’s Flex3, and Mozilla’s XUL4 all take a similar approach to that of Android: put layout details in an XML file and put programming smarts in source files (e.g., JavaScript for XUL). Many less-well-known GUI frameworks, such as ZK5, also use XML for view definition. While “following the herd” is not necessarily the best policy, it does have the advantage of helping to ease the transition into Android from any other XML-centered view description language. OK, So What Does It Look Like?Here is the Button from the previous chapter’s sample application, converted into an XMLlayout file, found in the Layouts/NowRedux sample project. This code sample along with all others in this chapter can be found in the Source Code area of .<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><Button xmlns:android="/apk/res/android"android:id="@+id/button"android:text=""android:layout_width="fill_parent"android:layout_height="fill_parent"/>The class name of the widget—Button—forms the name of the XML element. Since Button is an Android-supplied widget, we can just use the bare class name. If you create your own widgets as subclasses of android.view.View, you would need to provide a full package declara tion as well.The root element needs to declare the Android XML namespace:xmlns:android="/apk/res/android"All other elements will be children of the root and will inherit that namespace declaration.Because we want to reference this button from our Java code, we need to give it an identifier via the android:id attribute. We will cover this concept in greater detail later in this chapter.The remaining attributes are properties of this Button instance:• android:text indicates the initial text to be displayed on the button face (in this case, an empty string)• android:layout_width and android:layout_height tell Android to have the button’swidth and height fill the “parent”, in this case the entire screen—these attributes will be covered in greater detail in Chapter 7.Since this single widget is the only content in our activity, we only need this single element. Complex UIs will require a whole tree of elements, representing the widgets and containers that control their positioning. All the remaining chapters of this book will use the XML layout form whenever practical, so there are dozens of other examples of more complex layouts for you to peruse from Chapter 7 onward.What’s with the @ Signs?Many widgets and containers only need to appear in the XML layout file and do not need to be referenced in your Java code. For example, a static label (TextView) frequently only needs to be in the layout file to indicate where it should appear. These sorts of elements in the XML file do not need to have the android:id attribute to give them a name.Anything you do want to use in your Java source, though, needs an android:id.The convention is to use @+id/... as the id value, where the ... represents your locally unique name for the widget in question. In the XML layout example in the preceding section, @+id/button is the identifier for the Button widget.Android provides a few special android:id values, of the form @android:id/.... We will see some of these in various chapters of this book, such as Chapters 8 and 10.We Attach These to the Java How?Given that you have painstakingly set up the widgets and containers in an XML layout filenamed main.xml stored in res/layout, all you need is one statement in your activity’s onCreate() callback to use that layout:setContentView(yout.main);This is the same setContentView() we used earlier, passing it an instance of a View subclass (in that case, a Button). The Android-built view, constructed from our layout, is accessed from that code-generated R class. All of the layouts are accessible under yout, keyed by the base name of the layout file—main.xml results in yout.main.To access our identified widgets, use findViewById(), passing in the numeric identifier of the widget in question. That numeric identifier was generated by Android in the R class asR.id.something (where something is the specific widget you are seeking). Those widgets are simply subclasses of View, just like the Button instance we created in Chapter 4.The Rest of the StoryIn the original Now demo, the button’s face would show the current time, which would reflect when the button was last pushed (or when the activity was first shown, if the button had not yet been pushed).Most of that logic still works, even in this revised demo (NowRedux). However,rather than instantiating the Button in our activity’s onCreate() callback, we can reference the one from the XML layout:package youts;import android.app.Activity;import android.os.Bundle;import android.view.View;import android.widget.Button; import java.util.Date;public class NowRedux extends Activity implements View.OnClickListener { Button btn;@Overridepublic void onCreate(Bundle icicle) { super.onCreate(icicle);setContentView(yout.main);btn=(Button)findViewById(R.id.button);btn.setOnClickListener(this);upd ateTime();}public void onClick(View view) { updateTime();}private void updateTime() {btn.setText(new Date().toString()); }}The first difference is that rather than setting the content view to be a view we created in Java code, we set it to reference the XML layout (setContentView(yout.main)). The R.java source file will be updated when we rebuild this project to include a reference to our layout file (stored as main.xml in our project’s res/l ayout directory).The other difference is that we need to get our hands on our Button instance, for which we use the findViewById() call. Since we identified our button as @+id/button, we can reference the button’s identifier as R.id.button. Now, with the Button instance in hand, we can set the callback and set the label as needed.As you can see in Figure 5-1, the results look the same as with the originalNow demo.Figure 5-1. The NowRedux sample activity Employing Basic WidgetsE very GUI toolkit has some basic widgets: fields, labels, buttons, etc. Android’s toolkit is no different in scope, and the basic widgets will provide a good introduction as to how widgets work in Android activities.Assigning LabelsThe simplest widget is the label, referred to in Android as a TextView. Like in most GUI toolkits, labels are bits of text not editable directly by users. Typically, they are used to identify adjacent widgets (e.g., a “Name:” label before a field where one fills in a name).In Java, you can create a label by creating a TextView instance. More commonly, though, you will create labels in XML layout files by adding a TextView element to the layout, with an android:text property to set the value of the label itself. If you need to swap labels based on certain criteria, such as internationalization, you may wish to use a resource reference in the XML instead, as will be described in Chapter 9. TextView has numerous other properties of relevance for labels, such as:• android:typeface to set the typeface to use for the label (e.g., monospace) • android:textStyle to indicate that the typeface should be made bold (bold), italic (italic),or bold and italic (bold_italic)• android:textColor to set the color of the label’s text, in RGB hex format (e.g., #FF0000 for red)For example, in the Basic/Label project, you will find the following layout file:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><TextView xmlns:android=/apk/res/androidandroid:layout_width="fill_parent"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="You were expecting something profound?" />As you can see in Figure 6-1, just that layout alone, with the stub Java source provided by Android’s p roject builder (e.g., activityCreator), gives you the application.Figure 6-1. The LabelDemo sample applicationButton, Button, Who’s Got the Button?We’ve already seen the use of the Button widget in Chapters 4 and 5. As it turns out, Button is a subclass of TextView, so everything discussed in the preceding section in terms of formatting the face of the button still holds. Fleeting ImagesAndroid has two widgets to help you embed images in your activities: ImageView and ImageButton. As the names suggest, they are image-based analogues to TextView and Button, respectively.Each widget takes an android:src attribute (in an XML layout) to specify what picture to use. These usually reference a drawable resource, described in greater detail in the chapter on resources. You can also set the image content based on a Uri from a content provider via setImageURI().ImageButton, a subclass of ImageView, mixes in the standard Button behaviors, for responding to clicks and whatnot.For example, take a peek at the main.xml layout from the Basic/ImageView sample project which is found along with all other code samples at : <?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><ImageView xmlns:android=/apk/res/androidandroid:id="@+id/icon"android:layout_width="fill_parent"android:layout_height="fill_parent"android:adjustViewBounds="true"android:src="@drawable/molecule" />The result, just using the code-generated activity, is shown in Figure 6-2.Figure 6-2. The ImageViewDemo sample applicationFields of Green. Or Other Colors.Along with buttons and labels, fields are the third “anchor” of most GUI toolkits. In Android, they are implemented via the EditText widget, which is a subclass of the TextView used for labels.Along with the standard TextView properties (e.g., android:textStyle), EditText has many others that will be useful for you in constructing fields, including:• android:autoText, to control if the fie ld should provide automatic spelling assistance• android:capitalize, to control if the field should automatically capitalize the first letter of entered text (e.g., first name, city) • android:digits, to configure the field to accept only certain digi ts • android:singleLine, to control if the field is for single-line input or multiple-line input (e.g., does <Enter> move you to the next widget or add a newline?)Beyond those, you can configure fields to use specialized input methods, such asandroid:numeric for numeric-only input, android:password for shrouded password input,and android:phoneNumber for entering in phone numbers. If you want to create your own input method scheme (e.g., postal codes, Social Security numbers), you need to create your own implementation of the InputMethod interface, then configure the field to use it via android: inputMethod.For example, from the Basic/Field project, here is an XML layout file showing an EditText:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><EditTextxmlns:android=/apk/res/androidandroid:id="@+id/field"android:layout_width="fill_parent"android:layout_height="fill_parent"android:singleLine="false" />Note that android:singleLine is false, so users will be able to enter in several lines of text. For this project, the FieldDemo.java file populates the input field with some prose:package monsware.android.basic;import android.app.Activity;import android.os.Bundle;import android.widget.EditText;public class FieldDemo extends Activity { @Overridepublic void onCreate(Bundle icicle) { super.onCreate(icicle);setContentView(yout.main);EditText fld=(EditText)findViewById(R.id.field);fld.setText("Licensed under the Apache License, Version 2.0 " + "(the \"License\"); you may not use this file " + "except in compliance with the License. You may " + "obtain a copy of the License at " +"/licenses/LICENSE-2.0");}}The result, once built and installed into the emulator, is shown in Figure 6-3.Figure 6-3. The FieldDemo sample applicationNote Android’s emulator only allows one application in the launcher per unique Java package. Since all the demos in this chapter share the monsware.android.basic package, you will only see one of these demos in your emulator’s launcher at any one time.Another flavor of field is one that offers auto-completion, to help users supply a value without typing in the whole text. That is provided in Android as the AutoCompleteTextView widget and is discussed in Chapter 8.Just Another Box to CheckThe classic checkbox has two states: checked and unchecked. Clicking the checkbox toggles between those states to indicate a choice (e.g., “Ad d rush delivery to my order”). In Android, there is a CheckBox widget to meet this need. It has TextView as an ancestor, so you can use TextView properties likeandroid:textColor to format the widget. Within Java, you can invoke: • isChecked() to determi ne if the checkbox has been checked• setChecked() to force the checkbox into a checked or unchecked state • toggle() to toggle the checkbox as if the user checked itAlso, you can register a listener object (in this case, an instance of OnCheckedChangeListener) to be notified when the state of the checkbox changes.For example, from the Basic/CheckBox project, here is a simple checkbox layout:<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><CheckBox xmlns:android="/apk/res/android"android:id="@+id/check"android:layout_width="wrap_content"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="This checkbox is: unchecked" />The corresponding CheckBoxDemo.java retrieves and configures the behavior of the checkbox:public class CheckBoxDemo extends Activityimplements CompoundButton.OnCheckedChangeListener { CheckBox cb;@Overridepublic void onCreate(Bundle icicle) { super.onCreate(icicle);setContentView(yout.main);cb=(CheckBox)findViewById(R.id.check);cb.setOnCheckedChangeListener(this);}public void onCheckedChanged(CompoundButton buttonView,boolean isChecked) {if (isChecked) {cb.setText("This checkbox is: checked");}else {cb.setText("This checkbox is: unchecked");}}}Note that the activity serves as its own listener for checkbox state changes since it imple ments the OnCheckedChangeListener interface (via cb.setOnCheckedChangeListener(this)). The callback for the listener is onCheckedChanged(), which receives the checkbox whose state has changed and what the new state is. In this case, we update the text of the checkbox to reflect what the actual box contains.The result? Clicking the checkbox immediately updates its text, as you can see in Figures 6-4 and 6-5.Figure 6-4. The CheckBoxDemo sample application, with the checkbox uncheckedFigure 6-5. The same application, now with the checkbox checkedTurn the Radio UpAs with other implementations of radio buttons in other toolkits, Android’s radio buttons are two-state, like checkboxes, but can be grouped such that only one radio button in the group can be checked at any time.Like CheckBox, RadioButton inherits from CompoundButton, which in turn inherits fromTextView. Hence, all the standard TextView properties for font face, style, color, etc., are available for controlling the look of radio buttons. Similarly, you can call isChecked() on a RadioButton to see if it is selected, toggle() to select it, and so on, like you can with a CheckBox.Most times, you will want to put your RadioButton widgets inside of aRadioGroup. The RadioGroup indicates a set of radio buttons whose state is tied, meaning only one button out of the group can be selected at any time. If you assign an android:id to your RadioGroup in your XML layout, you can access the group from your Java code and invoke:• check() to check a specific radio button via its ID (e.g., group.check(R.id.radio1))• clearCheck() to clear all radio buttons, so none in the group are checked• getCheckedRadioButtonId() to get the ID of the currently-checked radio button (or -1 if none are checked)For example, from the Basic/RadioButton sample application, here is an XML layout showing a RadioGroup wrapping a set of RadioButton widgets: <?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?> <RadioGroupxmlns:android=/apk/res/androidandroid:orientation="vertical"android:layout_width="fill_parent"android:layout_height="fill_parent" ><RadioButton android:id="@+id/radio1"android:layout_width="wrap_content"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="Rock" /><RadioButton android:id="@+id/radio2"android:layout_width="wrap_content"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="Scissors" /><RadioButton android:id="@+id/radio3"android:layout_width="wrap_content"android:layout_height="wrap_content"android:text="Paper" /></RadioGroup>Figure 6-6 shows the result using the stock Android-generated Java forthe project and this layout.Figure 6-6. The RadioButtonDemo sample application Note that the radio button group is initially set to be completely unchecked at the outset. To pre-set one of the radio buttons to be checked, use either setChecked() on the RadioButton or check() on the RadioGroup from within your onCreate() callback in your activity.It’s Quite a ViewAll widgets, including the ones previously shown, extend View, and as such give all widgets an array of useful properties and methods beyond those already described.Useful PropertiesSome of the properties on View most likely to be used include:• Controls the focus sequence:• android:nextFocusDown• android:nextFocusLeft• android:nextFocusRight• android:nextFocusUp• android:visibility, which controls wheth er the widget is initially visible• android:background, which typically provides an RGB color value (e.g., #00FF00 for green) to serve as the background for the widgetUseful MethodsYou can toggle whether or not a widget is enabled via setEnabled() and see if it is enabled via isEnabled(). One common use pattern for this is to disable some widgets based on a CheckBox or RadioButton selection.You can give a widget focus via requestFocus() and see if it is focused via isFocused(). You might use this in concert with disabling widgets as previously mentioned, to ensure the proper widget has the focus once your disabling operation is complete.To help navigate the tree of widgets and containers that make up an activity’s overall view, you can use:• get Parent() to find the parent widget or container• findViewById() to find a child widget with a certain ID• getRootView() to get the root of the tree (e.g., what you provided to the activity via setContentView())Android 页面布局使用XML进行布局虽然纯粹通过Java代码在activity上创建和添加部件,在技术上是可行的,我们在第4章中做的一样,更常见的方法是使用一种基于XML的布局文件。

参考文献中英文格式

参考文献中英文格式

当涉及到引用参考文献时,不同的学科领域和期刊会有不同的要求和规范。

一般来说,英文参考文献的格式遵循着作者、文章标题、期刊名、出版日期和页码等信息的排列顺序。

下面是一些常见的参考文献格式示例:

期刊文章:

英文格式,Author(s). (Year). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page range.

中文格式,作者. (年份). 文章标题. 期刊名称, 卷号(期号), 页码范围。

书籍:

英文格式,Author(s). (Year). Title of book. Publisher.

中文格式,作者. (年份). 书名. 出版社。

网页:

英文格式,Author(s). (Year). Title of webpage. Site name. URL (Accessed date).

中文格式,作者. (年份). 网页标题. 网站名称. 网址 (访问日期)。

这只是一些常见的引用格式示例,具体的要求可能会因期刊或学术机构的要求而有所不同。

在撰写学术论文或提交文章时,最好参考目标期刊的官方引用格式指南,以确保引用格式符合要求。

中英文双语文章格式

中英文双语文章格式在当今全球化时代,中英文双语文章的应用越来越广泛。

无论是学术交流、商务沟通还是文化传播,双语文章都能有效地跨越语言障碍,促进国际间的理解与合作。

本文将为您详细介绍中英文双语文章的格式要求,帮助您规范撰写高质量的双语文章。

一、中英文双语文章的基本结构1.标题(Title)中英文双语文章的标题应简洁明了,反映文章主题。

中文标题在前,英文标题在后,两者之间用斜杠“/”隔开。

2.段落(Paragraph)双语文章的段落应保持一致性,即中文段落与英文段落一一对应。

每个段落首行缩进两个字符。

3.正文(Main Body)正文是文章的核心部分,包括引言、论述、结论等。

中英文双语文章的正文部分应遵循以下原则:a.中英文内容应保持一致性,确保信息传递的准确性。

b.中文部分采用宋体字体,英文部分采用Times New Roman字体。

c.字号大小保持一致,一般为小四号。

d.行间距设置为1.5倍行距。

4.参考文献(References)双语文章的参考文献部分应列出作者在撰写文章过程中引用的所有文献。

中文参考文献在前,英文参考文献在后,两者之间用分号“;”隔开。

二、中英文双语文章的注意事项1.术语统一在撰写双语文章时,应注意中英文术语的统一。

对于专业术语,应使用权威词典或学术界的通用译法。

2.语言表达双语文章的语言表达应简洁、准确、通顺。

避免使用过于复杂的句子结构,以免造成阅读困难。

3.标点符号中英文双语文章的标点符号应遵循各自的语言规范。

中文标点符号包括句号、逗号、顿号、引号等;英文标点符号包括句号、逗号、引号、破折号等。

4.排版格式双语文章的排版格式应保持整洁、美观。

注意调整段落间距、行间距、字体大小等,使文章更具可读性。

总结:中英文双语文章的格式要求主要包括标题、段落、正文、参考文献等方面。

在撰写过程中,应注意术语统一、语言表达、标点符号和排版格式等方面,以确保文章质量。

毕业论文文献内容编排中文与英文对照

毕业论文文献内容编排中文与英文对照在毕业论文的写作过程中,文献内容的编排是非常重要的一环。

其中,中文与英文对照是必不可少的部分。

在撰写毕业论文时,如何合理地安排中文和英文文献内容,是需要认真考虑的问题。

下面将从文献引用、文献列表和文献翻译等方面进行详细介绍。

一、文献引用在毕业论文中,引用文献是非常常见的做法。

当引用中文文献时,应在引用的文献后标注中文作者姓名和出版年份,如“张三,2000”。

而引用英文文献时,则需要标注英文作者姓名和出版年份,如“Smith, 2010”。

在引用文献时,要注意中英文对照的一致性,确保中英文作者姓名和出版年份的对应准确无误。

二、文献列表在毕业论文的文献部分,通常会列出所有引用过的文献。

在文献列表中,中文文献和英文文献的排列顺序可以根据引用的先后顺序或按照作者姓氏的字母顺序排列。

对于中文文献,应按照作者姓名的汉语拼音首字母顺序排列;对于英文文献,则按照作者姓氏的字母顺序排列。

在文献列表中,中文文献和英文文献之间可以用空行或其他方式进行区分,以便读者清晰地识别。

三、文献翻译在撰写毕业论文时,有时会需要引用外文文献。

对于外文文献的引用,需要进行准确的翻译。

在翻译文献时,要确保翻译的准确性和流畅性。

对于中文文献,如果需要引用英文文献的内容,可以在引用的内容后附上英文原文,以便读者查阅。

同样,对于英文文献,如果需要引用中文文献的内容,也可以在引用的内容后附上中文原文。

这样做不仅可以提高文献内容的可读性,还可以确保翻译的准确性。

总之,在毕业论文的文献内容编排中,中文与英文对照是非常重要的一环。

合理地安排中英文文献内容,不仅可以提高论文的质量,还可以让读者更好地理解论文的内容。

希望以上介绍对你在撰写毕业论文时有所帮助。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

关于毕业设计说明书(论文)英文文献及中文翻译撰写格式

为提高我校毕业生毕业设计说明书(毕业论文)的撰写质量,做到毕业设计说明书(毕业论文)在内容和格式上的统一和规范,特规定如下:

一、装订顺序

论文(设计说明书)英文文献及中文翻译内容一般应由3个部分组成,严格按以下顺序装订。

1、封面

2、中文翻译

3、英文文献(原文)

二、书写格式要求

1、毕业设计(论文)英文文献及中文翻译分毕业设计说明书英文文献及中文翻译和毕业论文英文文献及中文翻译两种,所有出现相关字样之处请根据具体情况选择“毕业设计说明书” 或“毕业论文”字样。

2、毕业设计说明书(毕业论文)英文文献及中文翻译中的中文翻译用Word 软件编辑,英文文献用原文,一律打印在A4幅面白纸上,单面打印。

3、毕业设计说明书(毕业论文)英文文献及中文翻译的上边距:30mm;下边距:25mm;左边距:3Omm;右边距:2Omm;行间距1.5倍行距。

4、中文翻译页眉的文字为“中北大学2019届毕业设计说明书” 或“中北大学××××届毕业论文”,用小四号黑体字,页眉线的上边距为25mm;页脚的下边距为18mm。

5、中文翻译正文用小四号宋体,每章的大标题用小三号黑体,加粗,留出上下间距为:段前0.5行,段后0.5行;二级标题用小四号黑体,加粗;其余小标题用小四号黑体,不加粗。

6、文中的图、表、附注、公式一律采用阿拉伯数字分章编号。

如图1.2,表2.3,附注3.2或式4.3。

7、图表应认真设计和绘制,不得徒手勾画。

表格与插图中的文字一律用5号宋体。

每一插图和表格应有明确简短的图表名,图名置于图之下,表名置于表之上,图表号与图表名之间空一格。

插图和表格应安排在正文中第一次提及该图表的文字的下方。

当插图或表格不能安排在该页时,应安排在该页的下一页。

图表居中放置,表尽量采用三线表。

每个表应尽量放在一页内,如有困难,要加“续表X.X”字样,并有标题栏。

图、表中若有附注时,附注各项的序号一律用阿拉伯数字加圆括号顺序排,如:注①。

附注写在图、表的下方。

文中公式的编号用圆括号括起写在右边行末顶格,其间不加虚线。

8、文中所用的物理量和单位及符号一律采用国家标准,可参见国家标准《量和单位》(GB3100~3102-93)。

9、文中章节编号可参照《中华人民共和国国家标准文献著录总则》。