第十三届“沪江杯”翻译竞赛原文(德语组)

第七届翻译大赛英文原文

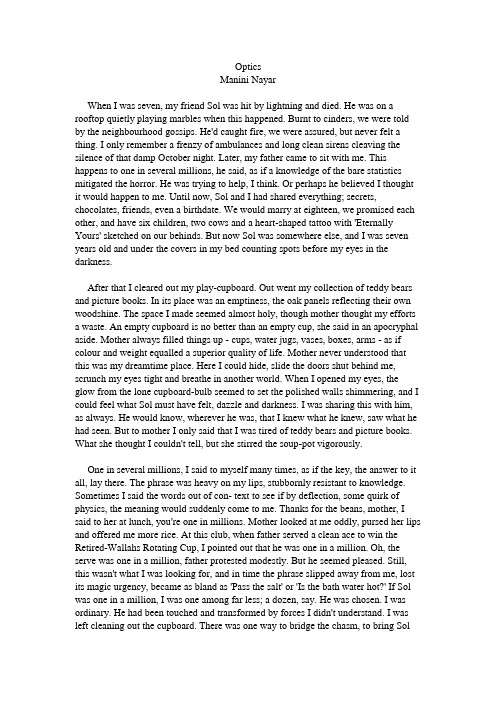

OpticsManini NayarWhen I was seven, my friend Sol was hit by lightning and died. He was on a rooftop quietly playing marbles when this happened. Burnt to cinders, we were told by the neighbourhood gossips. He'd caught fire, we were assured, but never felt a thing. I only remember a frenzy of ambulances and long clean sirens cleaving the silence of that damp October night. Later, my father came to sit with me. This happens to one in several millions, he said, as if a knowledge of the bare statistics mitigated the horror. He was trying to help, I think. Or perhaps he believed I thought it would happen to me. Until now, Sol and I had shared everything; secrets, chocolates, friends, even a birthdate. We would marry at eighteen, we promised each other, and have six children, two cows and a heart-shaped tattoo with 'Eternally Yours' sketched on our behinds. But now Sol was somewhere else, and I was seven years old and under the covers in my bed counting spots before my eyes in the darkness.After that I cleared out my play-cupboard. Out went my collection of teddy bears and picture books. In its place was an emptiness, the oak panels reflecting their own woodshine. The space I made seemed almost holy, though mother thought my efforts a waste. An empty cupboard is no better than an empty cup, she said in an apocryphal aside. Mother always filled things up - cups, water jugs, vases, boxes, arms - as if colour and weight equalled a superior quality of life. Mother never understood that this was my dreamtime place. Here I could hide, slide the doors shut behind me, scrunch my eyes tight and breathe in another world. When I opened my eyes, the glow from the lone cupboard-bulb seemed to set the polished walls shimmering, and I could feel what Sol must have felt, dazzle and darkness. I was sharing this with him, as always. He would know, wherever he was, that I knew what he knew, saw what he had seen. But to mother I only said that I was tired of teddy bears and picture books. What she thought I couldn't tell, but she stirred the soup-pot vigorously.One in several millions, I said to myself many times, as if the key, the answer to it all, lay there. The phrase was heavy on my lips, stubbornly resistant to knowledge. Sometimes I said the words out of con- text to see if by deflection, some quirk of physics, the meaning would suddenly come to me. Thanks for the beans, mother, I said to her at lunch, you're one in millions. Mother looked at me oddly, pursed her lips and offered me more rice. At this club, when father served a clean ace to win the Retired-Wallahs Rotating Cup, I pointed out that he was one in a million. Oh, the serve was one in a million, father protested modestly. But he seemed pleased. Still, this wasn't what I was looking for, and in time the phrase slipped away from me, lost its magic urgency, became as bland as 'Pass the salt' or 'Is the bath water hot?' If Sol was one in a million, I was one among far less; a dozen, say. He was chosen. I was ordinary. He had been touched and transformed by forces I didn't understand. I was left cleaning out the cupboard. There was one way to bridge the chasm, to bring Solback to life, but I would wait to try it until the most magical of moments. I would wait until the moment was so right and shimmering that Sol would have to come back. This was my weapon that nobody knew of, not even mother, even though she had pursed her lips up at the beans. This was between Sol and me.The winter had almost guttered into spring when father was ill. One February morning, he sat in his chair, ashen as the cinders in the grate. Then, his fingers splayed out in front of him, his mouth working, he heaved and fell. It all happened suddenly, so cleanly, as if rehearsed and perfected for weeks. Again the sirens, the screech of wheels, the white coats in perpetual motion. Heart seizures weren't one in a million. But they deprived you just the same, darkness but no dazzle, and a long waiting.Now I knew there was no turning back. This was the moment. I had to do it without delay; there was no time to waste. While they carried father out, I rushed into the cupboard, scrunched my eyes tight, opened them in the shimmer and called out'Sol! Sol! Sol!' I wanted to keep my mind blank, like death must be, but father and Sol gusted in and out in confusing pictures. Leaves in a storm and I the calm axis. Here was father playing marbles on a roof. Here was Sol serving ace after ace. Here was father with two cows. Here was Sol hunched over the breakfast table. The pictures eddied and rushed. The more frantic they grew, the clearer my voice became, tolling like a bell: 'Sol! Sol! Sol!' The cupboard rang with voices, some mine, some echoes, some from what seemed another place - where Sol was, maybe. The cup- board seemed to groan and reverberate, as if shaken by lightning and thunder. Any minute now it would burst open and I would find myself in a green valley fed by limpid brooks and red with hibiscus. I would run through tall grass and wading into the waters, see Sol picking flowers. I would open my eyes and he'd be there,hibiscus-laden, laughing. Where have you been, he'd say, as if it were I who had burned, falling in ashes. I was filled to bursting with a certainty so strong it seemed a celebration almost. Sobbing, I opened my eyes. The bulb winked at the walls.I fell asleep, I think, because I awoke to a deeper darkness. It was late, much past my bedtime. Slowly I crawled out of the cupboard, my tongue furred, my feet heavy. My mind felt like lead. Then I heard my name. Mother was in her chair by the window, her body defined by a thin ray of moonlight. Your father Will be well, she said quietly, and he will be home soon. The shaft of light in which she sat so motionless was like the light that would have touched Sol if he'd been lucky; if he had been like one of us, one in a dozen, or less. This light fell in a benediction, caressing mother, slipping gently over my father in his hospital bed six streets away. I reached out and stroked my mother's arm. It was warm like bath water, her skin the texture of hibiscus.We stayed together for some time, my mother and I, invaded by small night sounds and the raspy whirr of crickets. Then I stood up and turned to return to my room.Mother looked at me quizzically. Are you all right, she asked. I told her I was fine, that I had some c!eaning up to do. Then I went to my cupboard and stacked it up again with teddy bears and picture books.Some years later we moved to Rourkela, a small mining town in the north east, near Jamshedpur. The summer I turned sixteen, I got lost in the thick woods there. They weren't that deep - about three miles at the most. All I had to do was cycle forall I was worth, and in minutes I'd be on the dirt road leading into town. But a stir in the leaves gave me pause.I dismounted and stood listening. Branches arched like claws overhead. The sky crawled on a white belly of clouds. Shadows fell in tessellated patterns of grey and black. There was a faint thrumming all around, as if the air were being strung and practised for an overture. And yet there was nothing, just a silence of moving shadows, a bulb winking at the walls. I remembered Sol, of whom I hadn't thought in years. And foolishly again I waited, not for answers but simply for an end to the terror the woods were building in me, chord by chord, like dissonant music. When the cacophony grew too much to bear, I remounted and pedalled furiously, banshees screaming past my ears, my feet assuming a clockwork of their own. The pathless ground threw up leaves and stones, swirls of dust rose and settled. The air was cool and steady as I hurled myself into the falling light.光学玛尼尼·纳雅尔谈瀛洲译在我七岁那年,我的朋友索尔被闪电击中死去了。

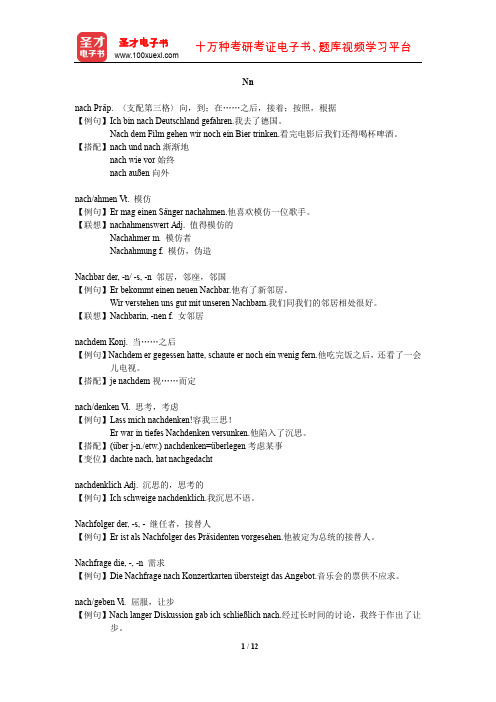

全国翻译专业资格(水平)考试德语三级口笔译核心词汇全突破(Nn)【圣才出品】

Nnnach Präp. 〈支配第三格〉向,到;在……之后,接着;按照,根据【例句】Ich bin nach Deutschland gefahren.我去了德国。

Nach dem Film gehen wir noch ein Bier trinken.看完电影后我们还得喝杯啤酒。

【搭配】nach und nach渐渐地nach wie vor始终nach außen向外nach/ahmen Vt. 模仿【例句】Er mag einen Sänger nachahmen.他喜欢模仿一位歌手。

【联想】nachahmenswert Adj.值得模仿的Nachahmer m.模仿者Nachahmung f.模仿,伪造Nachbar der, -n/ -s, -n 邻居,邻座,邻国【例句】Er bekommt einen neuen Nachbar.他有了新邻居。

Wir verstehen uns gut mit unseren Nachbarn.我们同我们的邻居相处很好。

【联想】Nachbarin, -nen f.女邻居nachdem Konj. 当……之后【例句】Nachdem er gegessen hatte, schaute er noch ein wenig fern.他吃完饭之后,还看了一会儿电视。

【搭配】je nachdem视……而定nach/denken Vi. 思考,考虑【例句】Lass mich nachdenken!容我三思!Er war in tiefes Nachdenken versunken.他陷入了沉思。

【搭配】(über j-n./etw.) nachdenken=überlegen考虑某事【变位】dachte nach, hat nachgedachtnachdenklich Adj. 沉思的,思考的【例句】Ich schweige nachdenklich.我沉思不语。

卡西欧杯翻译竞赛历年赛题及答案

第九届卡西欧杯翻译竞赛原文(英文组)来自: FLAA(《外国文艺》)Meansof Delive ryJoshua CohenSmuggl ing Afghan heroin or womenfrom Odessa wouldhave been morerepreh ensib le, but more logica l. Youknowyou’reafoolwhenwhatyou’redoingmakeseven the post office seem effici ent. Everyt hingI was packin g into thisunwiel dy, 1980s-vintag e suitca se was availa ble online. Idon’tmeanthatwhenIarrive d in Berlin I couldhave ordere dmoreLevi’s510s for next-day delive ry. I mean, I was packin g books.Not just any books— thesewere all the same book, multip le copies. “Invali d Format: An Anthol ogy of Triple Canopy, Volume 1”ispublis hed, yes, by Triple Canopy, an online magazi ne featur ing essays, fictio n, poetry and all variet y of audio/visualcultur e, dedica ted — click“About”—“toslowin g down the Intern et.”Withtheirbook, the firstin a planne d series, the editor s certai nly succee ded. They were slowin g me down too, just fine.“Invali d Format”collec ts in printthe magazi ne’sfirstfour issues and retail s, ideall y, for $25. But the 60 copies I was courie ring, in exchan ge for a couchand coffee-pressaccess in Kreuzb erg, wouldbe givenaway. For free.Untillately the printe d book change d more freque ntly, but less creati vely, than any othermedium. If you though t“TheQuotab le Ronald Reagan”wastooexpens ive in hardco ver, you couldwait a year or less for the same conten t to go soft. E-books, whichmade theirdebutin the 1990s, cut costseven more for both consum er and produc er, though as the Intern et expand ed thoserolesbecame confus ed.Self-publis hed book proper tiesbeganoutnum berin g, if not outsel ling, theirtradeequiva lents by the mid-2000s, a situat ion furthe r convol utedwhen the conglo merat es starte d“publis hing”“self-publis hed books.”Lastyear, Pengui n became the firstmajortradepressto go vanity: its Book Countr y e-imprin t will legiti mizeyour “origin al genrefictio n”forjustunder$100. Theseshifts make small, D.I.Y.collec tives like Triple Canopy appear more tradit ional than ever, if not just quixot ic — a word derive d from one of the firstnovels licens ed to a publis her.Kenned y Airpor t was no proble m, my connec tionat Charle s de Gaulle went fine. My luggag e connec ted too, arrivi ng intact at Tegel. But immedi ately afterimmigr ation, I was flagge d. A smalle r wheeli e bag held the clothi ng. As a custom s offici alrummag ed throug h my Hanes, I prepar ed for what came next: the larger case, caster s broken, handle rusted—I’mpretty sure it had alread y been Used when it was givento me for my bar mitzva h.Before the offici al couldopen the clasps and startpoking inside, I presen ted him with the docume nt the Triple Canopy editor, Alexan der Provan, had e-mailed me — the nightbefore? two nights before alread y? I’dbeenuponeofthosenights scouri ng New York City for a printe r. No one printe d anymor e. The docume nt stated, inEnglis h and German, that thesebookswere books. They were promot ional, to be givenaway at univer sitie s, galler ies, the Miss Read art-book fair at Kunst-Werke.“Allaresame?”theoffici al asked.“Allegleich,”Isaid.An olderguardcame over, prodde d a spine, said someth ingIdidn’tget. The younge r offici al laughe d, transl ated,“Hewantsto know if you read everyone.”At lunchthe next day with a musici an friend. In New York he played twicea month, ate food stamps. In collap singEuropehe’spaid2,000 eurosa nightto play aquattr ocent o church.“Whereare you handin g the booksout?”heasked.“Atanartfair.”“Whyanartfair?Whynotabookfair?”“It’sanart-bookfair.”“Asoppose d to a book-bookfair?”I told him that at book-book fairs, like the famous one in Frankf urt, they mostly gave out catalo gs.Taking trains and tramsin Berlin, I notice d: people readin g. Books, I mean, not pocket-size device s that bleepas if censor ious, on whicheven Shakes peare scanslike a spread sheet. Americ ans buy more than half of all e-bookssold intern ation ally—unless Europe ans fly regula rly to the United States for the sole purpos e ofdownlo ading readin g materi al from an Americ an I.P. addres s. As of the evenin g I stoppe d search ing the Intern et and actual ly went out to enjoyBerlin, e-booksaccoun ted for nearly 20 percen t of the salesof Americ an publis hers. In German y, howeve r, e-booksaccoun ted for only 1 percen t last year. I beganasking themultil ingua l, multi¬ethnic artist s around me why that was. It was 2 a.m., at Soho House, a privat eclubI’dcrashe d in the former Hitler¬jugend headqu arter s. One instal latio nistsaid, “Americ ans like e-booksbecaus ethey’reeasier to buy.”Aperfor mance artist said, “They’realsoeasier not to read.”Trueenough: theirpresen ce doesn’tremindyouofwhatyou’remissin g;theydon’ttake up spaceon shelve s. The next mornin g, Alexan der Provan and I lugged the booksfor distri butio n, gratis. Questi on: If booksbecome mere art object s, do e-booksbecome concep tualart? Juxtap osing psychi atric case notesby the physic ian-noveli st RivkaGalche n with a dramat icall y illust rated invest igati on into the devast ation of New Orlean s, “Invali d Format”isamongthe most artful new attemp ts to reinve nt the Web by the codex, and the codexby the Web. Its texts“scroll”: horizo ntall y, vertic ally; titlepagesevoke“screen s,”refram ing conten t that follow s not unifor mly and contin uousl y but rather as a welter of column shifts and fonts. Its closes t predec essor s mightbe mixed-mediaDada (Ducham p’sloose-leafed, shuffl eable“GreenBox”); or perhap s“ICanHasCheezb urger?,”thebest-sellin g book versio n of the pet-pictur es-with-funny-captio ns Web site ICanHa sChee zburg ; or simila r volume s fromStuffW hiteP eople Like.com and Awkwar dFami lyPho . Theselatter booksare merely the kitsch iestproduc ts of publis hing’srecent enthus iasmfor“back-engine ering.”They’repseudo liter ature, commod ities subjec t to the samerevers ing proces s that for over a centur y has paused“movies”into“stills”— into P.R. photos and dorm poster s — and notate d pop record ingsfor sheetmusic.Admitt edlyIdidn’thavemuchtimetoconsid er the implic ation s of adapti ve cultur e in Berlin. I was too busy dancin gto“IchLiebeWie Du Lügst,”aka“LovetheWayYou Lie,”byEminem, and fallin g asleep during“Bis(s) zum Ende der Nacht,”aka“TheTwilig ht Saga: Breaki ng Dawn,”justafterthe dubbed Bellacriesover herunlike ly pregna ncy, “Dasistunmögl ich!”— indeed!Transl ating medium s can seem just as unmögl ich as transl ating betwee n unrela ted langua ges: therewill be confus ions, distor tions, techni cal limita tions. The Web ande-book can influe nce the printbook only in matter s of styleand subjec t — no links, of course, just theirmetaph or. “Theghostin the machin e”can’tbeexorci sed, onlyturned around: the machin e inside the ghost.As for me, I was haunte d by my suitca se. The extraone, the empty. My last day in Kreuzb erg was spentconsid ering its fate. My wheeli e bag was packed. My laptop was stowed in my carry-on. I wanted to leavethe pleath er immens ity on the corner of Kottbu sserDamm, down by the canal,butI’ve neverbeen a waster. I brough t it back. It sits in the middle of my apartm ent, unreve rtibl e, only improv able, hollow, its lid floppe d open like the coverof a book.传送之道约书亚·科恩走私阿富汗的海洛因和贩卖来自敖德萨的妇女本应受到更多的谴责,但是也更合乎情理。

第八届中德文学翻译大赛翻译文章(德文)

König SalomoNach einer tatsächlichen BegebenheitNach der ersten …Aussprache“ war ihm klar, dass sie irgendwo Wanzen eingebaut hatten.Er suchte alles ab, baute das Transistorradio in der Küche auseinander. Leider wusste er nicht, wie eine Wanze aussah, und in dem Transistorradio waren hunderte von Dingern, die Wanzen sein konnten. Deshalb warf er das Radio weg, gegen Angelikas Protest.Aber Angelika wusste ja nicht, wie es war, wenn man dort saß und das Gefühl hatte, dass sie einem in den Kopf gucken konnten.Nach der zweiten Aussprache zog er das Telefon raus. Und warf den ganzen Krempel weg, der seit Jahren auf demKüchenbord herumlungerte, all die kleinen Vasen undTöpfchen und Mitbringsel und Geschenke, alles weg.Nach der dritten Aussprache brachte er den Kühlschrank in den Keller.Nach der vierten Aussprache ging er mit einem Seitenschneider durch die Wohnung und suchte nach kleinen Drähten und kniff schließlich die Klingel und die Telefonleitung durch, aber das Telefon stand sowieso schon im Keller.Nach der fünften Aussprache ging Loos zum Zahnarzt und ließ sich, unerträgliche Schmerzen vorschützend, zwei Zähne in der rechten, unteren Mundhälfte extrahieren.Die beiden Zähne hatten eine Amalgamfüllung gehabt.Als er nach Hause kam, ließ die Betäubung bereits ein wenig nach. Er kam in die Küche, wo Angelika gerade einen Auflauf in die Backröhre schob, nahm sich ein Handtuch und ein paar Eiswürfel.…Ach du lieber Gott“, sagte Angelika. …Was haben sie denn mit dir gemacht?“Aber Loos war schon wieder aus der Küche verschwunden. Er nahm zwei von den Tabletten, die ihm der Zahnarzt mitgegeben hatte, legte sich ins Bett und packte sich das Handtuch mit den Eiswürfeln auf die rechte Gesichtshälfte. Nach einer Weile schaute Angelika herein, aber Loos stellte sich schlafend. Dann schlief er aber tatsächlich ein. Er erwachte in einem durch und durch feuchten Kopfkissen.Er stand auf und wankte in die Küche, wo Angelika rasch die Wodkaflasche verschwinden ließ, aber das Glas stand noch auf dem Tisch.…Gib mir auch einen“, sagte er.Sie holte die Wodkaflasche wieder raus und stellte ein Glas hin, aber noch bevor sie ihm einschenkte, blieb ihr Blick an seinem Gesicht hängen.…Du siehst ja grausam aus.“, sagte sie. …Hat er einen gezogen?“…Zwei“, sagte Loos.…Waaaas?!“Er nahm ihr die Flasche aus der Hand und goss sich ein. …Das gibt’s doch nicht“, sagte Angelika.Loos trank.…Bei wem warst du?“, fragte Angelika.…Bei Lindstedt“, log er.…Und der hat dir zwei Zähne gezogen?“Loos überlegte einen Moment. Dann riss er einen Zettel vom Küchenblock ab und schrieb etwas drauf, in viel zu großen Druckbuchstaben, so groß, dass ein Zettel nicht ausreichte, und er einen zweiten dazunehmen musste. Dann legte er beide vor Angelika auf die Tischplatte. Auf den Zetteln stand: ZÄHNE: WANZENAngelika starrte ihn an.…In den Zähnen?“…Pssst“, mache Loos und legte den Finger über diegeschürzten Lippen.Angelikas Stimme bekam diesen drohenden Ton:…Du hast Wanzen in deinen Zähnen?“…Nicht so laut!“, flüsterte Loos. Er zeigte nach draußen ins Dunkel, wo seit Wochen die schneegraue Limousine stand: immer mit zwei Mann Besatzung.…Das darf doch nicht wahr sein.“, sagte Angelika.Sie griff sich ins Haar und strich es zurück, so dass der Haaransatz sichtbar wurde. Jetzt sah sie aus wie ein Marder. …Die waren sowieso hin.“, sagte Loos.Angelika stand auf.…Du hast dir zwei Zähne ziehen lassen, weil du Wanzen drin hast?“, sagte sie.…Nicht so laut!“…Ist das so richtig. Ja? Habe ich das richtig verstanden?“Loos sagte nichts mehr. Er trank seinen Wodka aus und schaute im Kühlschrank nach Eiswürfeln und stellte fest, dass er vergessen hatte, neues Eis anzusetzen.…Du bist ja irre.“, sagte Angelika.Er goss Wasser in das Eisschälchen und balancierte es zum Gefrierfach.…Du bist ja verrückt! Verrückt!“, sagte sieSie schlug ihm das Eisschälchen aus der Hand.…Verrückt!“, schrie sie.Plötzlich schlug er zu. Angelika machte ein helles Geräusch, wie früher beim Sex, wenn er das erste Mal in sie eindrang. Dann schlug er noch mal. Sie krümmte sich zusammen, und Loos schlug auf den gekrümmten Körper ein, der jetzt keine Geräusche mehr machte. Als er wieder zur Besinnung kam, lag Angelika auf dem Fußboden und weinte. Sie weinte fast lautlos. Nur hin und wieder atmete sie geräuschvoll ein, danach strömte die gepresste Luft durch ihre Kehle wie durch die Klappen eines kaputten Akkordeons.Das war nach der fünften Aussprache.Nach der sechsten Aussprache zog Angelika aus, und Loosließ sich von zwei verschiedenen Zahnärzten noch einmal je zwei plombierte Zähne extrahieren.Nun war er sicher, dass sie ihm nichts mehr anhaben konnten. Aber als sie ihm bei der siebenten Aussprache eines von seinen Gedichten vorlegten – und zwar eines, das er gefaltet im doppelten Boden einer Streichholzschachtel in seinem verschlossenen Schreibtischschubfach verwahrt hatte – , musste er seine Hände fest zwischen die Oberschenkel klemmen, damit sie nicht zitterten. Und dann zitterten sie immer noch.…Ist das Ihr Gedicht, Herr Loos?“Der Mann mit der Fleischnase schob das Blatt zu ihm herüber. …Ist das auch eines von Ihren unpolitischen Gedichten, Herr Loos?“ fragte der Mann mit der Fleischnase und tippte mehrmals mit dem Zeigefinger auf das Blatt. …Ist der Inhalt hier auch bloß...“ Er suchte das passende Wort... …christli ch-humanistisch?“Der Mann mit der Fleischnase stand auf und nahm das Blattin die Hand.Plötzlich hasste Loos das Gedicht.…Die Vogelscheuche“, las der Mann.Die beiden anderen kicherten: der ältere Mann, der wie das Staatsoberhaupt aussah, dessen Porträt an der Wand hing, und der junge Leutnant in Uniform, der immer mitschrieb. Die Fleischnase räusperte sich. Großer Ansatz: …Uniform, im Wind schlotternd...“, las die Fleischnase, unterbrach sich aber sofort: …Hm ... hm ... Was soll das bedeuten? Soll das heißen, dass unsere Nationale Volksarmee vor dem Feind schlottert?“Die anderen beiden lachten schallend, und die Fleischnase fragte:…Oder meinen Sie die Uniform des Bundesgrenzschutzes?“Er kam näher zu Loos, beugte sich zu ihm herunter. …Kriegen Sie vielleicht noch mal die Zähne auseinander!“, schrie die Fleischnase plötzlich.Loos starrte ihn an. Es wurde sehr hell, wie auf einemüberbelichteten Foto. Überdeutlich spürte er die Zahnlücken im ausgetrockneten Mundraum.…Junge, Junge...“, sagte die Fleis chnase und warf das Blatt in die Luft. …Irgendwann platzt mir hier noch der Kragen, und dann sind Sie aber woanders ... Vogelscheuche.“Der Mann, der dem Staatsoberhaupt ähnlich sah, kam zu Loos und setzte sich auf die Kante des Schreibtischs. …Herr Loos“, sagte er Mann. Seine Stimme war freundlich, fast bittend. …Gegen Sie liegen Mitteilungen vor. Verstehen Sie? Wir könnten auch andere Maßnahmen ergreifen. Aber wir versuchen, mit Ihnen zu sprechen. Sie sind ein sensibler Mensch. Sie schreiben Gedichte. Wir haben nichts gegen Gedichte. Wir haben Ihnen den Vorschlag gemacht, Mitglied im Zirkel Junger Lyriker zu werden. Sie wollen nicht. Sie wollen nicht mit uns reden. Sie lehnen alles immer nur ab. Sie haben immer den negativen Standpunkt. Was nützt Ihnen da s?“Loos starrte geradeaus an die Wand. Dort hing das Porträt des echten Staatsoberhaupts.…Wir wollen mit Ihnen reden!“, sagte das falsche Staatsoberhaupt. …Oder reden Sie nicht mehr mit uns?“…Oder wollen Sie hier einen auf durchgedreht machen?“, fragte die Fleischnase.Loos rührte sich nicht.Die drei Männer schauten einander an.…Puh“, machte die Fleischnase.…Mannohmann!“, sagte das falsche Staatsoberhaupt.Der junge Leutnant schüttelte missbilligend seinen Kopf.Das echte Staatsoberhaupt lächelte.N och am selben Tag baute sich Loos einen Faraday’schenKäfig aus Karnickeldraht. Mit Ausbuchtungen für die Ohren. Er setzte den Käfig auf und ging in den Keller. Er nahm Wodka und Tabletten mit. Er schluckte zwei Tabletten, trank die noch halbvolle Flasche Wodka aus und schlief mit demKäfig auf dem Kopf ein.Am nächsten Morgen wachte er ziemlich früh auf.Merkwürdigerweise hatte er keinen Brummschädel. Im Gegenteil, sein Kopf war ganz klar, seine Gedanken gingen leicht und flüssig. Und auf einmal wusste er, was er tun musste.Er ging in die Küche und kochte sich einen Tee und machte sich ein Weißbrot mit Pflaumenmus. Er frühstückte stehend. Er sah dabei aus dem Fenster, wo der schneegraue Wartburg stand, und er sah, dass die beiden Leute im Auto eingeschlafen waren. Das war gut.Das war ein gutes Zeichen.Dann zog er seine alte Pudelmütze über den Karnickeldraht-käfig und ging zum Bahnhof.S – stand für Schnellzug.A – stand für Bahnsteig A.L – stand für Berlin-Lichtenberg.Alles stimmte.Vom Bahnhof Berlin-Lichtenberg aus ging er nach Osten –das war das …O“! Menschen kam en ihm entgegen. Sie warfen ihm scheue Blicke zu und schauten rasch wieder zu Boden. Nur das Kind schaute ihn unverhohlen an, mit glänzenden, großen Augen.Die Straße machte eine paar Schlenker; er folgte ihnen mit ungutem Gefühl, wobei er versuchte, seine Richtung(…O“ wie Ost) beizubehalten. Lange ging er eine stark befahrene Straße entlang. Er schwitzte unter der Pudelmütze, aber er ging unbeirrt. Es stank jetzt nach Abgasen. Er atmete flach. Es war ihm klar, dass man die Autos abschaffen musste. Dann kam der Kreisverkehr. Loos schaute auf. Auf einem Schild stand: Marzahn –…M“. Da war es. Jetzt fehlte nur noch ein …O“.Er ging weiter in Richtung …M“. Das Gehen tat gut. Langsam hörten die Gedanken in seinem Kopf auf zu tanzen. Bald hatte er Klarheit. Er begann leise zu singen. Überall war jetzt Beton. Schwarze Drähte durchzogen den Himmel. Aber der Himmel war rot. Groß und rot. Die Lichter in den Häusergingen an, und die Sterne antworteten ihnen zögerlich aus der Ferne. Dann ging der Mond auf, und Loos wusste auf einmal: der Mond war das …O“ – der letzte fehlende Buchstabe.Er stand vor einem riesigen Neubaublock. Er studiertegründlich die Namen am ersten Aufgang ... Viele Namen. Aber der Name war nicht dabei. Zweiter Aufgang ... Ebenfalls nichts. Aber Loos war ganz ruhig. Er wusste: Hier musste es sein! Beim dritten Aufgang war die Klingelschildbeleuchtung kaputt. Loos entzündete ein Streichholz ... Selmer ... Schmidt ... Albrecht ... Frenzen ... Ein zweites Streichholz war nötig ... Brasch ... Neubert ... Da war er. Der Name, den er gesucht hatte:S A L O M O.Loos drückte den Knopf. Es vergingen lange Sekunden. Dann endlich eine helle weibliche Stimme:…Hallo?“Loos beugte sich ein kleines Stückchen vor.…Ich suche den König Salomo.“, sagte er.Dann wartete er auf das Surren des Türöffners.。

第十三届沪江杯翻译竞赛英语组原文及获奖译文

第十三届“沪江杯”翻译竞赛原文(英语组)Reading(excerpt)The Writer in WinterJohn Updike YOUNG OR OLD,a writer sends a book into the world,not himself.There is no Senior Tour for authors,with the tees shortened by twenty yards and carts allowed. No mercy is extended by the reviewers;but,then,it is not extended to the rookie writer,either.He or she may feel,as the gray-haired scribes of the day continue to take up space and consume the oxygen in the increasingly small room of the print world,that the elderly have the edge,with their established names and already secured honors.How we did adore and envy them,the idols of our college years—Hemingway and Faulkner,Frost and Eliot,Mary McCarthy and Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty!We imagined them aswim in a heavenly refulgence,as joyful and immutable in their exalted condition as angels forever singing.Now that I am their age—indeed,older than a number of them got to be—I can appreciate the advantages,for a writer,of youth and obscurity.You are not yet typecast.You can take a distant,cold view of the entire literary scene.You are full of your material—your family,your friends,your region of the country,your generation—when it is fresh and seems urgently worth communicating to readers.No amount of learned skills can substitute for the feeling of having a lot to say,of bringing news.Memories,impressions,and emotions from your first twenty years on earth are most writers’main material;little that comes afterward is quite so rich and resonant.By the age of forty,you have probably mined the purest veins of this precious lode;after that,continued creativity is a matter of sifting the leavings.You become playful and theoretical;you invent sequels,and attempt historical novels.The novels and stories thus generated may be more polished,more ingenious,even more humane than their predecessors;but none does quite the essential earthmoving work that Hawthorne,a writer who dwelt in the shadowland“where the Actual and the Imaginary may meet,”specified when he praised the novels of Anthony Trollope asbeing“as real as if some giant had hewn a great lump out of the earth and put it under a glass case.”This second quotation—one writer admiring a virtue he couldn’t claim—meant a lot to me when I first met it,and I have cited it before.A few images,a few memorable acquaintances,a few cherished phrases circle around the aging writer’s head like gnats as he strolls through the summertime woods at gloaming.He sits down before the word processor’s humming,expectant screen,facing the strong possibility that he has already expressed what he is struggling to express again.My word processor—a term that describes me as well—is the last of a series of instruments of self-expression that began with crayons and colored pencils held in my childish fist.My hands,somewhat grown,migrated to the keyboard of my mother’s typewriter,a portable Remington,and then,schooled in touch-typing,to my own machine,a beige Smith Corona expressly bought by loving parents for me to take to college.I graduated to an office model,on the premises of The New Yorker,that rose up,with an exciting heave,from the surface of a metal desk.Back in New England as a freelancer,I invested in an electric typewriter that snatched the letters from my fingertips with a sharp,premature clack;it held,as well as a black ribbon,a white one with which I could correct my many errors.Before long,this clever mechanism gave way to an even more highly evolved device,an early Wang word processor that did the typing itself,with a marvellous speed and infallibility.My next machine,an IBM, made the Wang seem slow and clunky and has been in turn superseded by a Dell that deals in dozens of type fonts and has a built-in spell checker.Through all this relentlessly advancing technology the same brain gropes through its diminishing neurons for images and narratives that will lift lumps out of the earth and put them under the glass case of published print.With ominous frequency,I can’t think of the right word.I know there is a word;I can visualize the exact shape it occupies in the jigsaw puzzle of the English language. But the word itself,with its precise edges and unique tint of meaning,hangs on the misty rim of consciousness.Eventually,with shamefaced recourse to my well-thumbed thesaurus or to a germane encyclopedia article,I may pin the worddown,only to discover that it unfortunately rhymes with the adjoining word of the sentence.Meanwhile,I have lost the rhythm and syntax of the thought I was shaping up,and the paragraph has skidded off(like this one)in an unforeseen direction.When,against my better judgment,I glance back at my prose from twenty or thirty years ago,the quality I admire and fear to have lost is its carefree bounce,its snap,its exuberant air of slight excess.The author,in his boyish innocence,is calling, like the sorcerer’s apprentice,upon unseen powers—the prodigious potential of this flexible language’s vast vocabulary.Prose should have a flow,the forward momentum of a certain energized weight;it should feel like a voice tumbling into your ear.An aging writer wonders if he has lost the ability to visualize a completed work, in its complex spatial relations.He should have in hand a provocative beginning and an ending that will feel inevitable.Instead,he may arrive at his ending nonplussed, the arc of his intended tale lying behind him in fragments.The threads have failed to knit.The leap of faith with which every narrative begins has landed him not on a far safe shore but in the middle of the drink.The failure to make final sense is more noticeable in a writer like Agatha Christie,whose last mysteries don’t quite solve all their puzzles,than in a broad-purposed visionary like Iris Murdoch,for whom puzzlement is part of the human condition.But in even the most sprawling narrative, things must add up.The ability to fill in a design is almost athletic,requiring endurance and agility and drawing upon some of the same mental muscles that develop early in mathematicians and musicians.Though writing,being partly a function of experience, has few truly precocious practitioners,early success and burnout are a dismally familiar American pattern.The mental muscles slacken,that first freshness fades.In my own experience,diligent as I have been,the early works remain the ones I am best known by,and the ones to which my later works are unfavorably compared.Among the rivals besetting an aging writer is his younger,nimbler self,when he was the cocky new thing.From the middle of my teens I submitted drawings,poems,and stories to The New Yorker;all came back with the same elegantly terse printed rejection slip.Myfirst break came late in my college career,when a short story that I had based on my grandmother’s slow dying of Parkinson’s disease was returned with a note scrawled in pencil at the bottom of the rejection slip.It read,if my failing memory serves:“Look—we don’t use stories of senility,but try us again.”Now“stories of senility”are about the only ones I have to tell.My only new experience is of aging,and not even the aged much want to read about it.We want to read,judging from the fiction that is printed,about life in full tide,in love or at war—bulletins from the active battlefields,the wretched childhoods,the poignant courtships,the fraught adulteries,the big deals,the scandals,the crises of sexually and professionally active adults.My first published novel was about old people;my hero was a ninety-year-old man.Having lived as a child with aging grandparents,I imagined old age with more vigor,color,and curiosity than I could bring to a description of it now.I don’t mean to complain.Old age treats free-lance writers pretty gently.There is no compulsory retirement at the office,and no athletic injuries signal that the game is over for good.Even with modern conditioning,a ballplayer can’t stretch his career much past forty,and at the same age an actress must yield the romantic lead to a younger woman.A writer’s fan base,unlike that of a rock star,is post-adolescent,and relatively tolerant of time’s scars;it distressed me to read of some teenager who, subjected to the Rolling Stones’halftime entertainment at a recent Super Bowl, wondered why that skinny old man(Mick Jagger)kept taking his shirt off and jumping around.The literary critics who coped with Hemingway’s later,bare-chested novel Across the River and Into the Trees asked much the same thing.By and large,time moves with merciful slowness in the old-fashioned world of writing.The eighty-eight-year-old Doris Lessing won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Elmore Leonard and P.D.James continue,into their eighties,to produce best-selling thrillers.Although books circulate ever more swiftly through the bookstores and back to the publisher again,the rhythms of readers are leisurely.They spread recommendations by word of mouth and“get around”to titles and authors years after making a mental note of them.A movie has a few weeks to find its audience,andtelevision shows flit by in an hour,but books physically endure,in public and private libraries,for generations.Buried reputations,like Melville’s,resurface in academia; avant-garde worthies such as Cormac McCarthy attain,late in life,best-seller lists and The Oprah Winfrey Show.A pervasive unpredictability lends hope to even the most superannuated competitor in the literary field.There is more than one measurement of success.A slender poetry volume selling fewer than a thousand copies and receiving a handful of admiring reviews can give its author a pride and sense of achievement denied more mercenary producers of the written word.As for bad reviews and poor sales,they can be dismissed on the irrefutable hypothesis that reviewers and book buyers are too obtuse to appreciate true excellence.Over time,many books quickly bloom and then vanish;a precious few unfold,petal by petal,and become classics.An aging writer has the not insignificant satisfaction of a shelf of books behind him that,as they wait for their ideal readers to discover them,will outlast him for a while.The pleasures,for him,of bookmaking—the first flush of inspiration,the patient months of research and plotting,the laserprinted final draft,the back-and-forthing with Big Apple publishers,the sample pages,the jacket sketches, the proofs,and at last the boxes from the printers,with their sweet heft and smell of binding glue—remain,and retain creation’s giddy bliss.Among those diminishing neurons there lurks the irrational hope that the last book might be the best.第十三届“沪江杯”翻译竞赛获奖译文(英语组)作家入冬陈以侃译作家不管岁数大小,送入世界的总是一本书,而不是他自己。

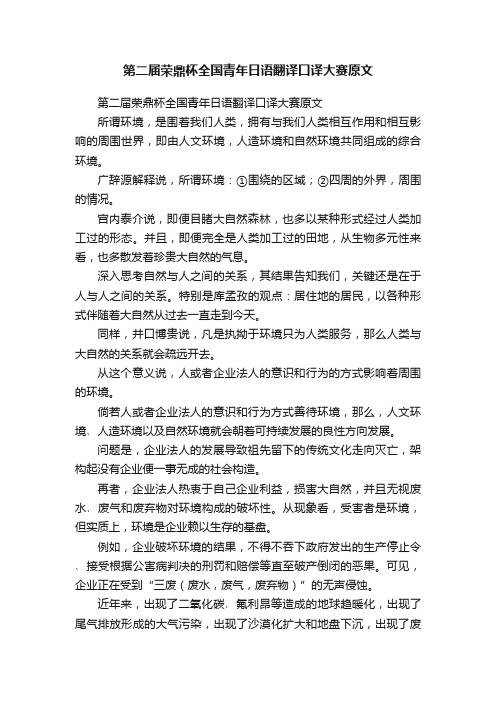

第二届荣鼎杯全国青年日语翻译口译大赛原文

第二届荣鼎杯全国青年日语翻译口译大赛原文第二届荣鼎杯全国青年日语翻译口译大赛原文所谓环境,是围着我们人类,拥有与我们人类相互作用和相互影响的周围世界,即由人文环境,人造环境和自然环境共同组成的综合环境。

广辞源解释说,所谓环境:①围绕的区域;②四周的外界,周围的情况。

宫内泰介说,即便目睹大自然森林,也多以某种形式经过人类加工过的形态。

并且,即便完全是人类加工过的田地,从生物多元性来看,也多散发着珍贵大自然的气息。

深入思考自然与人之间的关系,其结果告知我们,关键还是在于人与人之间的关系。

特别是库孟孜的观点:居住地的居民,以各种形式伴随着大自然从过去一直走到今天。

同样,井口博贵说,凡是执拗于环境只为人类服务,那么人类与大自然的关系就会疏远开去。

从这个意义说,人或者企业法人的意识和行为的方式影响着周围的环境。

倘若人或者企业法人的意识和行为方式善待环境,那么,人文环境﹑人造环境以及自然环境就会朝着可持续发展的良性方向发展。

问题是,企业法人的发展导致祖先留下的传统文化走向灭亡,架构起没有企业便一事无成的社会构造。

再者,企业法人热衷于自己企业利益,损害大自然,并且无视废水﹑废气和废弃物对环境构成的破坏性。

从现象看,受害者是环境,但实质上,环境是企业赖以生存的基盘。

例如,企业破坏环境的结果,不得不吞下政府发出的生产停止令﹑接受根据公害病判决的刑罚和赔偿等直至破产倒闭的恶果。

可见,企业正在受到“三废(废水,废气,废弃物)”的无声侵蚀。

近年来,出现了二氧化碳﹑氟利昂等造成的地球趋暖化,出现了尾气排放形成的大气污染,出现了沙漠化扩大和地盘下沉,出现了废弃物的非法扔弃﹑填埋场污水和工厂废水带来的河水与海水严重污染,还出现了由焚烧造成的二次污染等不忍目睹的现象。

因此,研究如何改善上述动摇人类生存基盘的环境问题和制定对策则成了燃眉之急。

也许,应该从战略高度根本解决日益严峻的环境问题之角度出发,以环境法和环境道德为基准,例如,也许应该把构筑回收再生利用体系﹑构筑环境教育体系﹑构筑申领ISO认证体系作为最优先考虑的课题吧?!中国的上海城,被称之为国际大都市,也被称之为世界最大工厂集结地。

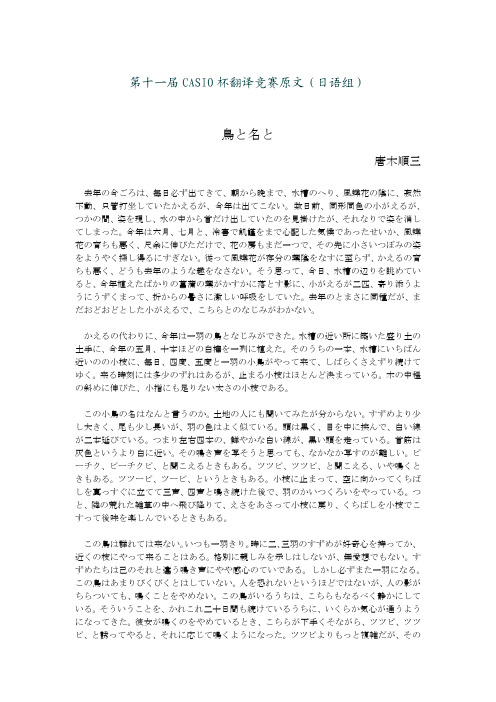

第十一届CASIO杯翻译竞赛原文(日语组)

第十一届CASIO杯翻译竞赛原文(日语组)鳥と名と唐木順三去年の今ごろは、毎日必ず出てきて、朝から晩まで、水槽のへり、風蝶花の陰に、寂然不動、只管打坐していたかえるが、今年は出てこない。

数日前、同形同色の小がえるが、つかの間、姿を現し、水の中から首だけ出していたのを見掛けたが、それなりで姿を消してしまった。

今年は六月、七月と、冷害で飢饉をまで心配した気候であったせいか、風蝶花の育ちも悪く、尺余に伸びただけで、花の房もまだ一つで、その先に小さいつぼみの姿をようやく探し得るにすぎない。

従って風蝶花が存分の葉陰をなすに至らず、かえるの育ちも悪く、どうも去年のような趣をなさない。

そう思って、今日、水槽の辺りを眺めていると、今年植えたばかりの菖蒲の葉がかすかに落とす影に、小がえるが二匹、寄り添うようにうずくまって、折からの暑さに激しい呼吸をしていた。

去年のとまさに同種だが、まだおどおどとした小がえるで、こちらとのなじみがわかない。

かえるの代わりに、今年は一羽の鳥となじみができた。

水槽の近い所に築いた盛り土の土手に、今年の五月、十本ほどの白樺を一列に植えた。

そのうちの一本、水槽にいちばん近いのの小枝に、毎日、四度、五度と一羽の小鳥がやって来て、しばらくさえずり続けてゆく。

来る時刻には多少のずれはあるが、止まる小枝はほとんど決まっている。

木の中程の斜めに伸びた、小指にも足りない太さの小枝である。

この小鳥の名はなんと言うのか。

土地の人にも聞いてみたが分からない。

すずめより少し大きく、尾も少し長いが、羽の色はよく似ている。

頭は黒く、目を中に挟んで、白い線が二本延びている。

つまり左右四本の、鮮やかな白い線が、黒い頭を走っている。

首筋は灰色というより白に近い。

その鳴き声を写そうと思っても、なかなか写すのが難しい。

ピーチク、ピーチクピ、と聞こえるときもある。

ツツピ、ツツピ、と聞こえる、いや鳴くときもある。

ツツーピ、ツーピ、というときもある。

翻译大赛第一届“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛原文及参考译文

翻译大赛第一届“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛原文及参考译文第一届“《英语世界》杯”翻译大赛原文及参考译文2010年原文Plutoria Avenue By Stephen LeacockThe Mausoleum Club stands on the quietest corner of the best residential street in the city. It is a Grecian building of white stone. Above it are great elm-trees with birds—the most expensive kind of birds—singing in the branches. The street in the softer hours of the morning has an almost reverential quiet. Great motors move drowsily along it, with solitary chauffeurs returning at 10.30 after conveying the earlier of the millionaires to their down-town offices. The sunlight flickers through the elm-trees, illuminating expensive nursemaids wheeling valuable children in little perambulators. Some of the children are worth millions and millions. In Europe, no doubt, you may see in the Unter den Linden Avenue or the Champs Elysées a little prince or princess go past with a chattering military guard to do honour. But that is nothing. It is not half so impressive, in the real sense, as what you may observe every morning on Plutoria Avenue beside the Mausoleum Club in the quietest part of the city. Here you may see a little toddling princess in a rabbit suit who owns fifty distilleries in her own right. There, in a lacquered perambulator, sails past a little hooded head that controls from its cradle an entire New Jersey corporation. The United States attorney-general is suing her as she sits, in a vain attempt to make her dissolve herself into constituent companies. Nearby is a child of four, in a khaki suit, who represents the merger of two trunk line railways. You may meet in the flickered sunlight any number of little princes and princesses for more real than the poor survivals of Europe. Incalculable infants wave their fifty-dollar ivory rattles in an inarticulate greeting to one another. A million dollars of preferred stock laughs merrily in recognition of a majority control going past in a go-cart drawn by an imported nurse. And through it all the sunlight falls through the elm-trees, and the birds sing and the motors hum, so that the whole world as seen from the boulevard of Plutoria Avenue is the very pleasantest place imaginable. Just below Plutoria Avenue, and parallel with it, the trees die out and the brick and stone of the city begins in earnest. Even from the avenue you see the tops of the sky-scraping buildings in the big commercial streets and can hear or almost hear the roar of the elevate railway, earning dividends. And beyond that again the city sinks lower, and is choked and crowded with the tangled streets and little houses of the slums. In fact, if you were to mount to the roof of the Mausoleum Club itself on Plutoris Avenue you could almost see the slums from there. But why should you? And on the other hand, if you never went up on the roof, but only dined inside among the palm-trees, you would never know that the slums existed—which is much better.参考译文普路托利大道李科克著曹明伦译莫索利俱乐部坐落在这座城市最适宜居住的街道最安静的一隅。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

第十三届“沪江杯”翻译竞赛原文(德语组)(前十二届冠名为“CASIO杯”)Der Weg hinaus(Auszug)Herbert Eisenreich Als wate er im Schlamm, so mühsam ging er; die Fußballschuhe hingen wie mit Blei gefüllt an seinen Beinen. Nur gewaltsam, wie gegen einen Orkan ankämpfend, hielt er die Richtung auf den dunklen, unbewegten Halbkreis vor ihm am Grunde der sich steilenden, von wimmelndem Leben quellenden Stufenwand des Stadions, auf jenen Halbkreis, der der Kabineneingang war. Den steuerte er an, wie ein leckes Schiff bei schwerem Seegang den Hafen. Hinter ihm war das unterbrochene Spiel wieder angepfiffen worden, das lenkte die meisten Augen von seinem Hinausgehen ab. Die aber, die neben und über dem Kabineneingang standen, sahen ihn näher kommen, und je näher er kam, desto mehr Blicke sammelten sich auf ihm; wie eiserne Pfeilspitzen von einem Magneten angezogen, lenkten diese Blicke sich auf ihn, gebündelt stachen sie auf ihn, einen unfreiwilligen Winkelried, ein. Pfui-Salven, das Knattern zahlloser winziger Hass-Explosionen, herangetragen auf den Wellenlinien greller Pfiffe. Gesichter sah er keine; aber er wusste, dass es dieselben Münder waren, die früher, all die stolzen Jahre lang, allsonntäglich ihren Beifall über ihn ergossen haben, wenn er so spielte, wie sie es gerne sahen. Wenn er, den Ball am Fuß wie unsichtbar angebunden, durch die Reihen der Gegner lief, dann liefen tausend Jubelrufe mit; wenn er den Ball auf den Zentimeter genau übers halbe Spielfeld passte, dann raunte es ringsum voll Ehrfurcht; und wenn er schoss, stockte dem ganzen Stadion der Atem, und dann erst riss es ihnen den Schrei aus der Kehle. O ja, er war ein Spieler gewesen wie nicht bald einer: kein Schwerathlet, der mit seinem Körpergewicht alles niederwalzt, was sich ihm in den Weg stellt, sondern der Artist, der seine Körperkraft nicht spüren, sondern nur wirken lässt. Meistens wurde er als Läufer aufgestellt, aber wenn Not am Manne war, führte er den Angriff oder verteidigte vor dem Tor. Dort, wo er eingesetzt war, gehörte das Spielfeld, so weit er es erlaufen konnte, ihm. Und wenn sein Nebenmann versagte, rackerte er für zwei.Und was hatte man ihm, war wieder ein Spiel gewonnen, nicht alles nachgerühmt! Dass er der beständigste Spieler sei, zuverlässig auf jedem Posten, ohne Formkrisen, ohne Launen; kein Star, sondern immer Teil der Mannschaft, ihr Motor und ihre Seele zugleich; und der fairste Fußballer seit langem, die Zeitungenbrachten Fotos, wie er über den hechtenden Tormann, um ihn nicht zu verletzen, hinwegspringt; wie er zum Kopfstoß mit regelrecht angelegten Armen hochschnellt; wie er dem Gegenspieler, der im Zweikampf zu Fall gekommen, kameradschaftlich auf die Beine hilft. Und jetzt stapfte er schwankenden Schrittes hinein in die Mauer vor ihm aus Gejohle, Pfiffen und Flüchen. Und alles, was ihn früher über das Spielfeld getragen, was seine Läufe beflügelt, was seinen Einsatz befeuert hatte: der Beifall, der Jubel, diese Woge von einem aufbrausendem Schrei, die aus dem Beton-Oval, einer einzigen Kehle, zum Himmel stieg und alsdann wie ein linder Frühlingsregen erquickend über ihm niederfiel: Das alles kam ihm jetzt, im Nachhinein, unwirklich vor; ja, ihm schien, als habe er sich all die Jahre lang verhört und als vernehme er jetzt erst, was die da oben all die Jahre lang wirklich geschrien hatten und als verstünde er erst jetzt, was dieses Schreien schon damals in Wahrheit bedeutet hatte. So torkelte er, wie ein blindgeschlagener Boxer auf den Schatten seines Gegners, darauf zu, im vernebelten Blick tat sich schwarz, mit jedem seiner Schritte sich in die Tiefe verfinsternd, der überdeckte Gang zu den Kabinen auf: ein brüllendes Maul inmitten einer zuckenden Grimasse. Und dieser Rachen tat sich auf, ihn zu verschlingen auf Nimmerwiedersehen.Und alles nur, weil er den Flügel nicht hatte halten können; der Bursche mit seinen einundzwanzig Jahren war eben schneller als er, der schon zehn Jahre mehr auf dem Buckel hatte, und was für Jahre! Mit einundzwanzig war er ebenso schnell gewesen oder noch schneller. Auch mit fünfundzwanzig, mit sechs- und siebenundzwan zig noch. Gegen die dreißig zu spürte er’s dann: die Muskeln verkrampften sich öfter, die Lunge pfiff im Hals, das Herz klopfte, als wollte es raus aus diesem Körper, der es pumpen hieß wie verrückt. Gegen die dreißig zu spürt man’s eben allmählich, dass m an die Zehen gebrochen, die Rippen geprellt und sich den Schädel brummig gestoßen hat, dass man sich Sonntag für Sonntag das halbe Leben aus dem Leib gelaufen hat, und dann natürlich auch die Sorge um die Zukunft. Das Kaffeehaus war anfangs gut besucht, aber es kamen zu viele Schnorrer hin, und die Erika taugte halt nicht fürs Geschäft, und gar nicht für ein solches! Und wenn er selber bediente, dann war’s ja auch kein Wunder, dass er ein Achtel mittrank und manchmal auch zwei oder drei. Mehr als drei oder vier Achtel aber waren es selten, da hatte Rudi einfach Unrecht, wenn er alles aufs Trinken schob! Und auf das bisschen Rauchen! Geraucht hatten schließlich fast alle; natürlich nicht grad vor dem Spiel, aber nachher, und abends, man wollte ja schließlich auch sein Endchen Privatleben haben, wie auch Rudi seines hatte, überhaupt der! Der hatte frühzeitig Schluss gemacht, ging dann als Trainer insAusland, da war er ein feiner Herr mit einer Mordsgage und nichts wie Kommandieren, so wie er jetzt ihn kommandierte, seit er zurück und jetzt hier bei ihnen Trainer war.。