International Diversification and Firm Value

国际商业英文作文

国际商业英文作文Paragraph 1: The Importance of International Business。

International business plays a crucial role in the global economy. It allows companies to expand their market reach beyond national borders and tap into new opportunities. By engaging in international trade and investment, businesses can access a wider customer base, benefit from economies of scale, and diversify their operations. Moreover, international business fosters cultural exchange and collaboration among nations, contributing to mutual understanding and economic growth.Paragraph 2: Challenges in International Business。

While international business offers numerous benefits, it also presents various challenges. One of these challenges is cultural differences. Every country has its unique customs, traditions, and business practices, which can create misunderstandings and hinder effectivecommunication. Additionally, legal and regulatory frameworks differ across countries, making it essential for businesses to navigate complex legal systems and comply with international trade laws. Moreover, fluctuations in currency exchange rates and political instability incertain regions can pose risks to international business operations.Paragraph 3: Strategies for Success in International Business。

Diversification and Corporate Strategy

5

Major Corporate Level Strategies

Single Business Dominant Business Related Diversification Unrelated Diversification

6

What is Related Diversification?

Diversification and Corporate Strategy

Corporate Level Strategy – the strategy for a company and all of its business units as a whole Diversification – the primary approach to corporate level strategy Diversified firms vary according to Level of diversification Degree of relatedness

Pharmaceutical segment

Products for anti-infective, antipsychotic, cardiovascular, contraceptive, dermatology, gastrointestinal, hematology, immunology, neurology, oncology, pain management, urology, and virology

11

What is Unrelated Diversification?

Involves diversifying into businesses with No strategic fit No meaningful value chain relationships No unifying strategic theme Approach is to venture into “any business in which we think we can make a profit” Firms pursuing unrelated diversification are often referred to as conglomerates

International Diversification, Ownership Structure, Legal Origin, and Earnings Management

International Diversification,Ownership Structure,Legal Origin,and Earnings Management:Evidence from TaiwanC HEN-L UNG C HIN*Y U-J U C HEN**T SUN-J UI H SIEH***The primary objective of this study is to investigate the impact of corpo-rate internationalization on earnings management.We also explore themitigating roles of corporate ownership structure,as measured by diver-gence of controlling owner’s control and cash rights,and the proportionof firms that operate in common law countries on earnings management.Using a sample drawn from Taiwan,we find that greater corporateinternationalization is associated with a higher level of earnings man-agement,as proxied by discretionary accruals and the likelihood ofexactly meeting or just beating analyst forecast.Corporate internation-alization is measured by the ratio of foreign assets to total assets,foreign operational country scope,and the number of foreign investees,respectively.In addition,we find that companies can reduce the nega-tive effects of internationalization on earnings management by improv-ing their corporate ownership structures or investing in a higherproportion of common law countries where there is a better investorlegal protection environment and higher information transparency.1.IntroductionOver the past decade,a growing number of listed firms in developed and developing markets have substantially expanded their operations abroad.1Despite the prevalence of international diversification,there is surprisingly little evidence of its effect on earnings management.This paper explores the association between the extent of a firm’s international diversification and earnings *National Chengchi University**Providence University***Providence University1.For example,cross-border investments of U.S.firms have grown by more than700percent (World Trade Organization[2000]),and S&P500firms report that foreign sales account for more than24percent of total sales.In addition,of the ten largest panies listed on the NYSE, almost one-half of their revenues are generated from foreign operations(Meek and Thomas[2004]). In the case of Taiwan,the volume of international trade and foreign direct investment has approached 50percent of gross national product in recent years(Chang[2007]).233234JOURNAL OF ACCOUNTING,AUDITING&FINANCE management.Furthermore,we investigate whether an effective corporate owner-ship structure plays a critical role in mitigating earnings management induced by corporate internationalization.The ownership structure is measured as the diver-gence between the ultimate owner’s voting rights and cash flow rights.Finally, we examine whether the association between corporate internationalization and earnings management is reduced when companies operate in a higher proportion of countries with better legal protections to investors.The first question to be addressed in this paper is whether corporate interna-tional diversification results in a higher degree of earnings management.First, while domestic earnings refers to a single country,foreign earnings encompasses countries from around the world differing drastically in terms of economic condi-tions,political stability,competitive forces,growth opportunities,governmental regulations,and so on(Thomas[2000]).With increased geographic dispersion of firm assets,corporate international diversification thus increases organizational complexity,and in turn increases information asymmetry between managers and investors.Managers may exploit these discretions to make self-maximizing deci-sion,which decreases firm value.For example,Hope and Thomas(2008)show that when information asymmetries induced by international diversification increase,managers are more likely to engage in foreign empire building.To mask the adverse effect of these suboptimal decisions arising from their discre-tion on firm performance,managers have the incentive to engage in aggressive earnings management.Second,expansion into international markets increases the complexity of information processing for investors(Thomas[1999];Callen,Hope, and Segal[2005])and analysts(Duru and Reeb[2002];Tihanyi and Thomas [2005];Herrmann,Hope,and Thomas[2008]).2These results,in conjunction with the findings that managers tend to engage in a higher level of earnings management as information asymmetry increases(e.g.,Dye[1988];Beatty and Harris[1999]; Richardson[2000]),lead to our expectation that managers exploit this additional level of information asymmetry to engage in earnings management.Next,we explore the association between ownership structures of multina-tional firms and earnings management.The primary agency problem in most countries outside the United States is reflected in the conflict of interest between controlling owners and minority owners(La Porta,Lopez-de-Silanes,and Shleifer[1999];Haw,Hu,Hwang,and Wu[2004];Francis,Schipper,and Vin-cent[2005]),and the former generally possess control rights in excess of cash flow rights via stock pyramids and cross-ownership structures.When control divergence increases,the controlling owner’s ability and incentive to expropri-ate minority investors increases also.3Insiders(such as controlling owners or2.For example,Duru and Reeb(2002)document that greater corporate international diversifi-cation is associated with less accurate analyst forecasts.3.Claessens,Djankov,and Lang(2000,84)cite La Porta,Lopez-de-Silanes,and Shleifer’s (1999)statement that,in East Asia,corporate control can be achieved while holding much less than an absolute majority of the stock.In that area,the probability that a single controlling owner holds less than20percent of the stock is very high.This held true in80percent of the cases,across the four East Asian countries.Claessens,Djankov,and Lang(2000)report that the average voting rights held by controlling shareholders in Taiwan is about18.96percent,while the average cash flow rights held by controlling shareholders in Taiwan is about15.98percent.managers)have incentives to conceal private control benefits from outsiders because,if these benefits are detected,outsiders will take disciplinary actions against them (Shleifer and Vishny [1997];Leuz,Nanda,and Wysocki [2003]).Therefore,controlling owners and managers tend to manage earnings in an attempt to mask true firm’s performance and to conceal their private control benefits from outsiders (Leuz,Nanda,and Wysocki [2003];Haw et al.[2004]),particularly in the context of internationalization.In this paper,we hypothesize that an effective corporate ownership structure,as measured by the divergence between controlling owners’cash flow rights and voting rights,plays a critical role in mitigating earnings management induced by corporate internationalization.We further examine whether the degree of earnings management decreases when companies invest in a higher proportion of common law countries.Prior studies (e.g.,La Porta,Lopez-de-Silanes,Shleifer,and Vishny [1997,2000])show that the common law countries (e.g.,the United States and the United Kingdom)offer the best investor protection,while the French-based code law countries offer the least protection.Better law protection limits insiders’ability to acquire private control benefits and reduces their incentives to mask a firm’s performance and manage earnings (Leuz,Nanda,and Wysocki [2003]).Further-more,in market-oriented common law countries,the base of shareholders typi-cally is larger and more diverse,and information asymmetry is more efficiently resolved through public disclosure.Hence,there is a larger demand for account-ing quality (Ball,Kothari,and Robin [2000];Ball,Robin,and Wu [2003]).Therefore,we expect that the pervasiveness of earnings management declines when companies invest in a higher proportion of common law countries.The motivations for using Taiwanese firms’data stem from the following four reasons.First,internationalization may become an indispensable strategy for a firm’s growth in the emerging countries.Taiwan is characterized by a heavy reliance on exports,smaller stock markets,higher ownership concentrations,weaker investor protections,and lower disclosure requirements.Therefore,the effect of internationalization on earnings management in Taiwanese firms should be more pronounced,providing a stronger test of our hypotheses.Second,the relationship between ownership structure and financial report-ing has not been studied in a concentrated ownership context like that in Taiwan,the dominant context outside the United States.In East Asian corpora-tions,the high concentration of ownership nullifies the principal-agent problem between owners and managers as well as the related role of accounting-based managerial contracts.It is interesting to see how the ownership structure of a multinational firm interacts with the extent of earnings management using Taiwanese data.Third,prior literature focuses primarily on the effects of legal protection on a company’s earnings quality and investigates how the legal protection in differ-ent regimes affects a firm’s earnings quality.Unlike prior studies,the current pa-per explores how the earnings quality of a multinational firm is affected by a proportion of foreign investees with better legal protection environment (i.e.,common law countries).We believe that using Taiwanese firms is appropriate to 235INTERNATIONAL DIVERSIFICATION,OWNERSHIP STRUCTURE236JOURNAL OF ACCOUNTING,AUDITING&FINANCE examine whether foreign legal systems have an impact on firms’earnings management.4Finally,the Generally Accepted Accounting Principles(GAAP)in Taiwan are similar to those in the United States.In particular,Taiwan’s segment disclosure rule, Taiwan’s Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No.20,Disclosure of Seg-ment Financial Information(hereafter TSFAS20),is almost identical to U.S.State-ment of Financial Accounting Standards No.131(SFAS131)5and International Accounting Standards No.14(IAS14).Thus,although not many countries require segment disclosures,our findings suggest the importance of these disclosures.Our evidence supports the prediction that in the context of an emerging mar-ket,such as the Taiwanese market,the pervasiveness of earnings management increases in aggressive internationalization.However,such earnings management behavior effects can be mitigated through specific mechanisms.These mecha-nisms include improving ownership structures of multinational firms or investing more heavily in common law countries.This paper contributes to several streams of literature.First,our study con-tributes to literature on the association between internationalization and earnings management.Unlike prior studies(e.g.,Bodnar and Weintrop[1997];Bodnar, Hwang,and Weintrop[2003])that focus on countries of Anglo-Saxon cultural derivation,we use Taiwan’s data and find that corporate internationalization exacerbates earnings management in the context of the code law system.Due to the fact that Taiwan’s GAAP for segment reporting is similar to the USFAS131 and IAS14,and that the nature of corporate ownership structures differs between Taiwan and the Anglo-Saxon countries examined in Bodnar and Weintrop(1997) and Bodnar,Hwang,and Weintrop(2003),our findings provide further under-standing of the impact of corporate ownership structure on earnings management outside the United States and other Anglo-Saxon countries.64.With regard to the legal protection environment of Taiwanese firms engaging in internation-alization,in our sample,some50percent of investees were in common law countries,with the re-mainder in civil law countries.See the median of LAW in Table2.5.TSFAS20requires firms to identify their reportable segments;disclose operating perform-ance based on geographic area,industry classifications,and sales to critical customers and exports overseas classifications.Furthermore,additional reporting of both income statement and balance sheet data are required.This includes information on foreign investee revenue,sales to external customers, and intersegment sales or transfers when these equal or exceed10percent of the combined revenue of all reportable operating segments.These requirements are similar to those of SFAS131.However, SFAS131allows firms not to disclose earnings for nonoperating segments.According to Herrmann and Thomas(2000),only16percent of the companies in their sample continue to disclose geographic earnings after implementation of SFAS131.In addition,the Taiwan Stock Exchange Corporation stipulates that the publicly listed firms must disclose information about their overseas investments through the Market Observation Post System.The information to be disclosed includes the amount invested,foreign investee locations,and the profit or loss from these investments.6.Recent developments in the United States highlight the importance of understanding the quality of financial reporting using IFRS standards(e.g.,Reason[2005];Cook and Taub[2007]; Johnson[2007]).These developments include recent moves by the U.S.Securities and Exchange Commission to allow foreign-private issuers to use IAS as the reporting scheme rather than requiring the use of U.S.GAAPs;joint standard development activities under way by the FASB and the IASB; and suggestions that even U.S.-based issuers may be required to abandon GAAP in favor of IFRS.Second,we contribute to the literature on internationalization and corporate ownership structure by exploring and documenting the effects of the controlling owner’s control divergence of a multinational firm on earnings management.The fundamental agency in most countries stems from the conflict of interest between controlling owner and minority.The results,in combination with the fact that multinational firms possess a higher level of information asymmetry,allow man-agers to engage in a higher degree of earnings management.Hence,it is impor-tant to understand the influence of corporate ownership structure,as measured by control divergence,on earnings management by multinational firms.Obviously,investing corporate assets overseas partially removes them from the domestic court system and judicial processes.Therefore,our third contribution is to exam-ine the effects of the legal regime governing investor protection in the investee companies on earnings management.Prior literature on internationalization im-plicitly assumes that the effects of expansion outside the home country are the same regardless of the countries into which firms expand (e.g.,Duru and Reeb[2002]).However,corporate internationalization may have a differential impact on the degree of earnings management across legal protection regimes within which foreign investees operate.Hence,a combination of better corporate owner-ship structures and foreign legal regimes that protect the investor may mitigate earnings management behavior.Furthermore,this study contributes to the literature on the effectiveness of regulation in providing information valuable to investors.Regulation issues exist both within and across national boundaries,consistent with increasing levels of economic globalization of economic activities and investments.In that regard,there is an increasing emphasis on harmonization of accounting standards,with pressure growing for convergence between International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS)and U.S.GAAPs.Our findings imply that segment disclosure seems to have great value to investors in understanding foreign operation and seems to decrease information asymmetry between managers and investors,as well as to further reduce earnings management.The rest of this paper is organized as follows.Section 2presents the hypoth-eses we test.Section 3describes our data,sample selection procedure,and research designs.Section 4presents the empirical results and some additional tests.Section 5presents our conclusions.2.HypothesesIt is well documented that expansion into international markets increases the overall organizational complexity and in turn the complexity of information proc-essing for investors (Thomas [1999];Callen,Hope,and Segal [2005])and analysts (Duru and Reeb [2002];Tihanyi and Thomas [2005];Herrmann,Hope,and Thomas [2008]).International expansion typically leads to an increase in overall organizational complexity and in turn hampers the firm’s information 237INTERNATIONAL DIVERSIFICATION,OWNERSHIP STRUCTURE238JOURNAL OF ACCOUNTING,AUDITING&FINANCE environment.As mentioned above,in contrast to domestic earnings,foreign earn-ings encompasses countries from around the world differing drastically in terms of economic conditions,competitive forces,political stability,growth opportuni-ties,governmental regulations,and so on(Thomas[2000]).Thus,with increased geographic dispersion of firm assets,it is presumably more difficult for investors or even analysts to carefully scrutinize the firm’s earnings reports and make accurate assessment of foreign operations.For example,Thomas(1999)shows that investors underestimate the persistence of foreign earnings.Thomas posits that one possible explanation for the existence of market mispricing is that it is difficult for investors to understand fully the origin of firms’foreign earnings (Thomas[1999,265]).7Similarly,Duru and Reeb(2002)and Tihanyi and Thomas(2005)further find that international diversification leads to less accurate analyst earnings forecasts.Thus,the degree of information asymmetry increases with the extent of corporate international diversification.Analytical models(e.g.,Dye[1988];Trueman and Titman[1988])indicate that the level of earnings management increases as information asymmetry increases.In addition,empirical studies(e.g.,Schipper[1989];Warfield,Wild,and Wild[1995];Beatty and Harris[1999];Richardson[2000])further provide support-ing evidence that managers may exploit the informational asymmetry and engage in a higher degree of earnings management.For example,Schipper(1989)and Warfield,Wild,and Wild(1995)argue that when shareholders have insufficient resources,incentives,or access to relevant information to monitor manager’s actions,earnings management can also occur.Thus,we expect that managers of multinational firms may engage in a higher degree of earnings management,by exploiting this additional level of information asymmetry,than otherwise would be the case if listed firms were not internationally diversified.With increased geographic dispersion of firm assets,corporate international diversification leads to not only an increase in overall organizational complexity, but also an increase in managers’discretion over operating decision.Kogut (1983)argues that expansion into international markets increases firms’opera-tional flexibility and allows firms to change value by exploiting the increased uncertainty of the international environment.For example,global manufacturing gives managers additional opportunities to exercise discretion by shifting produc-tion to lower-or higher-cost locations.Bodnar,Tang,and Weintrop(1999)note that operating in multiple geographic locations creates additional options.Thus, corporate internationalization increases the possibility for managers to enjoy more discretion.Under this circumstance,it is presumably apparent that managers may exploit these discretions to make self-maximizing decision,which decreases firm value.For example,Hope and Thomas(2008)show that managers are more7.Khurana,Pereira,and Raman(2003)find that analysts fail to fully incorporate the higher persistence of foreign earnings.They argue that their findings help explain the market mispricing documented by Thomas(2000).likely to engage in foreign ‘‘empire building’’when information asymmetries induced by international diversification increase.Stulz (1990)also documents that increased information asymmetry between managers and investors,arising from international diversification,is likely to lead to overinvestment and misallo-cation of resources.To mask the adverse effect of their discretion and suboptimal decision on firm performance,managers of multinational firms may have strong incentives to engage in aggressive earnings management.The preceding arguments thus suggest a positive association between the firm’s international diversification and the extent of earnings management.These discussions and predictions lead to the first testable hypothesis:H 1:Greater corporate internationalization is associated with a higher degreeof earnings management.Widely dispersed ownership is not the most common form of ownership struc-ture in listed firms around the world.Despite some concentration of ownership in the United States,an even higher ownership concentration exits in other developed and developing countries (La Porta,Lopez-de-Silanes,and Shleifer [1999];Haw et al.[2004];Francis,Schipper,and Vincent [2005]).The fundamental agency problem for listed firms in these countries stems from the conflict of interest between minority shareholders and controlling owners.The latter typically exercise control power in excess of their cash flow rights via stock pyramids and cross-ownership structures.Because a smaller fraction of the firm’s cash flow rights rela-tive to voting rights fails to align controlling owner incentive with those of minor-ity shareholders,controlling owners thus possess incentives and the ability to extract private control benefits (expropriation of the firm’s assets and opportunities,and outright theft)that are not shared by minority shareholders in proportion to the shares owned.Extracting private control benefits,if detected,is likely to invite external intervention by minority shareholders,analysts,stock exchanges,or regu-lators (Haw et al.[2004]).The desire to avoid external monitoring and loss of rep-utation induces insiders to mask or conceal their private control benefits by managing reported earnings (Leuz,Nanda,and Wysocki [2003];Haw et al.[2004]).Haw et al.(2004)also document that earnings management increases as the control divergence of the controlling shareholders increases.In the context of multinational firms,where additional organizational com-plexity and a greater degree of information asymmetry exists between managers and investors,managers might have greater discretion over opportunistic behav-iors.In this paper,we thus hypothesize that a decrease in the degree of diver-gence between the controlling owner’s voting rights and cash flow rights mitigates the effects of international diversification on earnings management.Hence,we propose the second hypothesis as follows:H 2:The association between earnings management and corporate internation-alization is less pronounced when the control divergence of controlling owners decreases.239INTERNATIONAL DIVERSIFICATION,OWNERSHIP STRUCTURE240JOURNAL OF ACCOUNTING,AUDITING&FINANCE An important difference between common law(e.g.,United States)and code law countries(e.g.,Germany)is the manner of resolving information asymmetry between managers and potential users of accounting information.In market-oriented common law countries,the base of shareholders typically is larger and more diverse,and information asymmetry is more efficiently resolved through public disclosure.The demand for high-quality financial disclosure is enforced in a market system,so there is also a higher frequency and expected cost of share-holder litigation(Ball,Kothari,and Robin[2000];Ball,Robin,and Wu[2003]). On the other hand,in planning-oriented code law countries,information asymme-try is more likely to be resolved by‘‘insider’’communication with stakeholder representatives,so demand is lower for high-quality public financial reporting and disclosure(Ball,Kothari,and Robin[2000];Ball,Robin,and Wu[2003]). Consequently,it is well documented that common law countries typically have stronger protection for outside investors(both shareholders and creditors)(i.e., La Porta et al.[2000])8and better accounting quality(La Porta et al.[1998]) than code law countries.9Prior studies show that strong shareholder protection in the marketplace should attenuate management opportunism(Jensen and Mecking[1976];Holmstrom [1979])and in turn reduce their incentives to mask private control benefits by manipulating earnings(Jensen and Mecking[1976];Hung[2001];Leuz,Nanda, and Wysocki[2003]).Stated differently,managers are less likely to behave oppor-tunistically and manipulate earnings in common law countries with strong protec-tion than in code law countries with weak protection.For example,there are many mechanisms for oppressed shareholders to make legal claims against directors in the United States,while there are few such mechanisms in Germany(La Porta et al. [1998]).U.S.managers who materially misstate earnings generally face shareholders’class-action suits and securities regulators’investigations,but German managers rarely face such consequences.As a consequence,U.S.managers are less likely to exhibit such behavior,compared with German managers,due to the higher cost of opportunistic behavior(La Porta et al.[1998];Hung[2001]).Recent research on the effect of legal origin system on earnings quality gen-erally lends support to the above arguments.For example,Hung(2001)finds that the use of accrual accounting negatively affects the value relevance of financial statements in civil law countries with weak shareholder protection.This negative effect,however,does not exist in common law countries.Haw et al.(2004) Porta et al.(1997)also examined legal rules associated with protection of corporate shareholders and the quality of their enforcement in forty-nine countries.In addition,compared with common law countries,civil law countries have the weakest investor protections and the least devel-oped capital markets.9.For example,strict,well-enforced laws that protect minority investors are more a feature of countries with common law traditions than those with civil law traditions.9Well-functioning legal and judicial systems limit insiders’private control benefits by making wealth expropriation legally riskier and more expensive(La Porta et al.[2000]),and shareholder litigation is a mechanism to enforce high-quality financial reporting in common law countries(Ball,Kothari,and Robin[2000]).indicate that earnings management influenced by control divergence is limited more in common law countries than in code law countries.10The stream of literature on cross-listing further shows that cross-listing in common law countries provides a credible commitment to higher-quality disclo-sure.For example,a U.S.cross-listing typically improves transparency by impos-ing disclosure requirements on firms that are more stringent than the disclosure requirements they face in their home country (e.g.,Coffee [1999,2002];Lang,Lins,and Miller [2003]).11As a consequence,firms listing on a U.S.exchange accept the consequence of being subject to an additional layer of monitoring by a variety of U.S.market intermediaries.12A firm’s willingness to be listed in markets with higher transparencies may be considered a signal to investors that the controlling owners will be less willing to exploit the minority owners’inter-ests (Doidge,Karolyi,and Stulz [2004]).In the same vein,companies with greater investments in common law countries are taking actions that render them less capable of exploiting minority investors and in turn are more likely to pro-vide accounting reporting of higher quality.In this paper,we expect,in the context of internationally diversified corpora-tions,that pervasiveness of earnings management declines when companies invest in a higher proportion of common law countries.Unlike the preceding research (Ball,Kothari,and Robin [2000];Leuz,Nanda,and Wysocki [2003];Haw et al.[2004]Leuz,Nanda,and Wysocki ),13where the focus is exclusively on the association between a firm’s financial reporting quality and the legal protection of its home country,this study further examines,in the context of corporate international diversification,the association between the earnings10.In addition to managers’behavior,the legal origin system also has an effect on analysts’forecast behavior.Analysts play an increasingly important role of monitoring managers’behavior in capital markets.Khanna,Palepu,and Chang (2000)and Hope (2003)indicate that in common law countries stronger enforcement of accounting standards and higher quality of accounting are associ-ated with higher analysts earnings forecast accuracy (Hope [2003]).11.For example,cross-listing subjects them to enforcement actions initiated by the U.S.Secur-ities and Exchange Commission,to class action lawsuits filed in the U.S.court,and to scrutiny from U.S.media and analysts.Furthermore,if they raise funds in the United States,these firms are sub-jected to monitoring by underwriters.12.The extant evidence documents that firms listed in countries with better investor protection or transparency (e.g.,United States)experience positive abnormal returns (Foerster and Karolyi[1999]),that they subsequently raise more capital after listing (Lins,Strickland,and Zenner [2005]),that their cost of capital is lower (Hail and Leuz [2004]),that estimates of private benefits of control are lower (Doidge,Karolyi,and Stulz,[2004]),and that firms are valued more highly (Doidge,Karolyi,and Stulz [2004]).13.Haw et al.(2004)found that there was less apparent earnings management by firms when the controlling owner had more voting than cash flow rights in countries where the legal code pro-vided more protection to investors than in countries where the legal code did not so protect the investors.Leuz,Nanda,and Wysocki (2003)found that earnings management was higher in countries where the legal system provided minority owners with fewer rights than in countries where the legal system provided minority owners with greater rights.This finding is consistent with Chin,Kleinman,Lee,and Lin (2006)in the context of the Taiwanese market.Finally,Ball,Kothari,and Robin (2000)reported that less timely and less conservative earnings reports tended to be issued in so-called civil law countries (called code countries by Ball,Kothari,and Robin [2000])than in common law countries.241INTERNATIONAL DIVERSIFICATION,OWNERSHIP STRUCTURE。

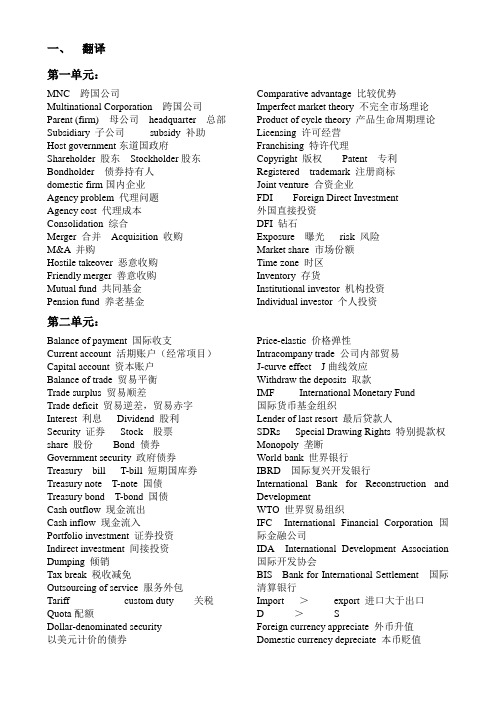

国际金融翻译

一、翻译第一单元:MNC 跨国公司Multinational Corporation 跨国公司Parent (firm) 母公司headquarter 总部Subsidiary 子公司subsidy 补助Host government东道国政府Shareholder 股东Stockholder股东Bondholder 债券持有人domestic firm国内企业Agency problem 代理问题Agency cost 代理成本Consolidation 综合Merger 合并Acquisition 收购M&A 并购Hostile takeover 恶意收购Friendly merger 善意收购Mutual fund 共同基金Pension fund 养老基金Comparative advantage 比较优势Imperfect market theory 不完全市场理论Product of cycle theory 产品生命周期理论Licensing 许可经营Franchising 特许代理Copyright 版权Patent 专利Registered trademark 注册商标Joint venture 合资企业FDI Foreign Direct Investment外国直接投资DFI 钻石Exposure 曝光risk 风险Market share 市场份额Time zone 时区Inventory 存货Institutional investor 机构投资Individual investor 个人投资第二单元:Balance of payment 国际收支Current account 活期账户(经常项目)Capital account 资本账户Balance of trade 贸易平衡Trade surplus 贸易顺差Trade deficit 贸易逆差,贸易赤字Interest 利息Dividend 股利Security 证券Stock 股票share 股份Bond 债券Government security 政府债券Treasury bill T-bill 短期国库券Treasury note T-note 国债Treasury bond T-bond 国债Cash outflow 现金流出Cash inflow 现金流入Portfolio investment 证券投资Indirect investment 间接投资Dumping 倾销Tax break 税收减免Outsourcing of service 服务外包Tariff custom duty 关税Quota配额Dollar-denominated security以美元计价的债券Price-elastic 价格弹性Intracompany trade 公司内部贸易J-curve effect J曲线效应Withdraw the deposits 取款IMF International Monetary Fund国际货币基金组织Lender of last resort 最后贷款人SDRs Special Drawing Rights 特别提款权Monopoly 垄断World bank 世界银行IBRD 国际复兴开发银行International Bank for Reconstruction and DevelopmentWTO 世界贸易组织IFC International Financial Corporation 国际金融公司IDA International Development Association 国际开发协会BIS Bank for International Settlement 国际清算银行Import >export 进口大于出口D >SForeign currency appreciate 外币升值Domestic currency depreciate 本币贬值第三单元:Fixed exchange rate system 固定汇率制度Floating exchange rate system 浮动汇率制度Appreciate 货币升值Depreciate 货币贬值Revalue 法定升值Devalue 法定贬值Nominal interest rate 名义利率Real interest rate 实际利率Fisher Effect 费舍效应International diversification 国际多元化Creditor 贷款人,债权人Borrower 借款人Convert euro into pound 欧元兑换英镑Exchange yen for U.S. dollar 美元兑换日元Great Depression 大萧条Gold standard 金本位制Bretton Woods System 布雷顿森林体系Spot market 即期市场Spot exchange rate 即期汇率Security firm 证券公司Interbank market 银行同业市场Broker 经纪人,中间人Liquidity 流动性Forward exchange market 远期外汇市场Forward exchange rate 远期汇率Hedge 对冲,保值Speculator 投机者Bid rate 买入价Ask rate 卖出价Bid-ask spread价差Direct quotation 直接标价法Indirect quotation 间接标价法Cross exchange rate 交叉汇率Currency future contract 货币期货合约Currency call option 买入期权Currency put option 卖出期权Strike price exercise price 执行价格Eurodollar 欧洲美元Eurocurrency 欧洲货币OPEC Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries国际石油出口国Petrodollar 石油美元LIBOR London Interbank Offer Rate伦敦银行同业拆借利率NIBOR 纽约银行同业拆借利率HIBOR 香港银行同业拆借利率SIBOR 新加坡银行同业拆借利率Syndicate 辛迪加贷款The lead bank 牵头银行Foreign bond 外国债券Parallel bond 并行债券Samurai bond 武士债券Bulldog bond 猛犬债券Yankee bond 扬基债券Panda bond 熊猫债券Eurobond 欧洲债券List 上市IPO Initial Public Offering首次公开放行Debt financing 债务性融资Equity financing 股权性融资Retail transaction 零售交易Wholesale transaction 批发交易Opportunity cost 机会成本第四单元:Equilibrium exchange rate 均衡利率Macro variable 宏观变量Micro variable 微观变量Emerging market 新兴市场Institutional investor 机构投资者Yield 收入,收益第五单元:Forward 远期合约forward rate 远期汇率Non-deliverable forward contract不交割远期合约Swap 掉期Brazilian real 巴西雷亚尔Norwegian krone 挪威克朗South African rand南非兰特CzecH koruna 捷克克朗Polish zloty波兰兹罗提Hungarian forint匈牙利福林Initial margin 初始保证金Variation margin 变动保证金Production level 生产规模Call option 买入期权(看涨期权)Put option 卖出期权Exercise price 协定价格Strike price 执行价格Chicago Mercantile Exchange芝加哥商品交易所Chicago Board Options Exchange 芝加哥期权交易所Security and Exchange Commission 美国证券交易委员会Collateral 抵押Open position 敞开头寸Long position 多头Short position 空头Bid 招标,投标Break-even point盈亏相抵点第六单元:Freely floating 无管制浮动Clean float 自由浮动汇率制度Managed floating Dirty float 管理浮动Pegged exchange rate system 盯住汇率制度Currency board 货币局制度Dollarization 美元化Exchange rate target zone 汇率目标区General Motor (GM) 通用汽车Dollar-denominated goods 美元计价商品Finished goods 滞成品,产成品A stagnant economy 滞涨经济A recession 萧条Aggregate demand 总需求Aggregate supply 总供给European Currency Unit (ECU)欧洲货币单位A tight monetary policy 紧缩的货币政策An expansionary monetary policy扩张的货币政策A stimulative monetary policy刺激性的货币政策An easy monetary policy 简单的货币政策Fiscal policy 财政政策Budget deficit 预算赤字The stock price plummets 股票价格骤跌Withdraw the investment 撤资Default on the debt 债务违约Adverse effect 不利影响Favorable effect 有利影响Government outlay 政府支出Stimulate the economy 刺激经济增长Risk premium 风险溢价Credit risk 信用风险European Union 欧盟The euro zone 欧元区A consolidated monetary policy统一的货币政策A common monetary policy 共同的货币政策European Central Bank (ECB)欧洲中央银行The Federal Resere System (the Fed)美联储Money supply 货币供给Business cycle 经济中心Flooding the market with dollars美元充斥市场Direct intervention 直接干预Indirect intervention 间接干预Plaza Accord 广场协议Industrialized country 工业化国家Sterilized intervention 冲销式干预Nonsterilized intervention 非冲销式干预Louvre Accord 卢浮宫协议Manipulate exchange rate 操纵汇率第七单元:Interest rate parity IRP 利率平价Arbitrage 套汇Arbitrager 套利International arbitrage 国际套汇Interest arbitrage 套利Commodity arbitrage 商品套利Security arbitrage 安全套利Locational arbitrage 两角套汇Triangular arbitrage 三角套汇covered Interest arbitrage 抵补套利Uncovered interest arbitrage 无担保套利Risk-free profit riskless profit 无风险利润Discrepancy 差异Shopping aroundDeposit interest rate 存款利率Loan interest rate 贷款利率Malaysian ringgit 马来西亚林吉特Exchange dollars for pounds 英镑兑换美元Purchase pounds with dollars 美元购买英镑Convert dollars to pounds 英镑兑换美元The return on the deposit 关于存款的回报第八单元:PPP Purchasing Power Parity购买力平价理论Absolute form of PPP 绝对购买力平价理论Law of one price 一价定律Relative form of PPP相对购买力平价理论A basket of products 一篮子商品International Fisher effect IFE国际费舍效应二、简答第一章International Business: Theories:1.Theory of Comparative Advantage2、Imperfect Markets Theory3、Product Cycle Theory 有哪些国际商务理论:比较优势理论不完全市场理论产品周期理论International Business Methods:(1)International trade(2)Licensing(3)Franchising(4)Joint venture(5)Acquisitions of existing operations 6 Establishing new foreign subsidiaries 有哪些国际商业法国际贸易许可特许经营合资企业收购现有业务建立新的外国子公司第二章International Trade Flow Factors (1)Inflation(2)National Income(3)Government Restrictions (4)Exchange Rates 影响国际贸易流通的因素通货膨胀国民收入政府限制汇率第四章Factors that Influence Exchange Rates 影响极其汇率的因素()EXPGCINCINTINFfe∆∆∆∆∆=,,,,e = percentage change in the spot rate 在即期汇率变化的百分比∆ INF = change in the relative inflation rate 相对通货膨胀率∆ INT = change in the relative interest rate 相对利率∆ INC = change in the relative income level 相对收入水平∆ GC = change in government controls 政府管制∆ EXP=change in expectations of future exchange rates 对未来汇率的预期三、课后习题P113,8、9、138. (1)the large amount of imports and lack of exports place downword pressure on Ruble.(2)High inflation also place downword pressure on Ruble.9. (1)A relative decline in economic growth will reduce Asia demand for U.S. products, which will place upward pressure on Asia currencies.(2)the decline in interest rate will place downward pressure on Asia currencies.(3)the overall impact depends on the magnitude of the factors just describe.13. (1) the interest rate in Canada declines to a level below the U.S. interest rate, places downward pressure on Canadian dollar’s value against USD.(2)Japanese investors that previously invested in Canada may shift to U.S., which will place downward pressure on the CAD’a value against JPY.P196,2、11、12、15、192. lower interest rate may reduce capital inflow to U.S., which could have reduced the value of $. If $ weakens, the export would increased, thus to stimulate the economy.11. U.S. Fed would normally consider a loose monetay policy to stimulate the economy. However, it could weaken $, a weak $ is expect to favorably affect US exporting firms and adversely affect U.S. importing firms.12. it can not apply intervention on its own. Because the monetary policy is consolidated.15.A. the volume of the sales should decline as the costs to consumers would rise due to the higher interest rate.B. the cost of purchasing materials should decline because the A$ appreciates against HK$.C. the interest expenses should decline because it will take fewer A$s to make the monthly payment of $100,000.19. the ECB could sell euros in the foreign exchange market, which may weaken euro, and cause an increase in the demand for European imports.Small Besiness Dilemma (p199)1. there will be downward pressure on the value of pounds.2. the performance would be adversely affected by BOE policy. Because if pound weaken, the receivables will convert to fewer $s, which reflect a reduction in revenue.P2301.£1=$1.50=C$2The crosed rate quoted equal to the rate calculated, therefore triangular arbitrage cannot be used to earn a profit.2. if invest in U.S. 1+0.03=$1.03if make covered interest arbitrage in U.K.[(1/1.60)×(1+0.04)] ×1.56=$1.014Because 1.014﹤1.03, it is not feasible.(1.014-1)/1=1.4% ﹤3%, it is not feasible.14.(1) yes, one could buy NZD at yardley Bank at $.40/NZD, and sell to Beal Bank for $.401/NZD. (1millon/0.4) ×0.401-1million=$2500(2) The ask price on NZD of Yardley Bank will increase.The bid price on NZD of Beal Bank will derease.16.(1) if invest locally:1+6%=1.06 pesos(2) If covered interest arbitrage in U.S.[(1×0.1)(1+5%)] ÷0.098=1.07 pesos(3) Because 1.06<1.07, the arbitrage is feasible17.[(1/0.80) ×(1+4%)×0.79—1]÷1=2.7%Because 2.7% exceeds the yield in U.S. over the 90 day period, the covered interes arbitrage is worthwhile. The Canadian dollars spot rate should rise, and its forward rate should fall, the 90-day Canadian interest rate may fall and that in U.S. may rise.21.For U.S. investor engaging covered interest arbitrage in New Zealand[(1/0.5)(1+6%)0.54-1] ÷1=14.48%14.48%>10%, it is feasible.。

国际财务管理(原书第8版)教学课件Eun8e_Ch_015_PPT

0.44 Swiss stocks

0.27 0.12

1

U.S. stocks

International stocks

10 20 30 40 50

Number of Stocks

Copyright © 2018 by the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 15-6

Copyright © 2018 by the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 15-7

Optimal International Portfolio Selection

• The correlation of the U.S. stock market with the returns on the stock markets in other nations varies.

Copyright © 2018 by the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 15-2

Focus on the Issues

• In this chapter, we focus on the following issues:

– (i) why investors diversify their portfolios internationally, – (ii) how much investors can gain from international

Copyright © 2018 by the McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. 15-12

国际金融课件internationalfinance

06

中国国际金融的实践与展望

中国国际金融业在规模和业务范围上不断扩大,成为全球金融市场的重要参与者。

中国国际金融业在推动经济增长、促进国际贸易和投资等方面发挥了重要作用。

改革开放以来,中国国际金融业经历了从无到有、从小到大的发展历程,逐步建立起较为完善的金融机构体系和金融市场体系。

中国国际金融的发展历程与现状

Global financial markets facilitate the flow of capital across borders, allowing for the efficient allocation of resources and the hedging of risks.

Regional financial markets serve specific geographical regions and are often associated with trade blocs or economic unions.

01

国际金融危机的定义

由于国际金融市场上的过度投机、金融监管缺失等原因,导致国际金融市场出现大规模动荡,影响各国经济的稳定。

02

国际金融危机的传染机制

通过贸易、金融和信息等渠道,将危机从一个国家传递到另一个国家。

国际金融危机及其传染机制

1

2

3

通过监测和分析国际金融市场的相关信息,及时发现潜在的风险点,采取应对措施。

02

03

04

05

Main International Financial Centers and Their Characteristics 主要国际金融中心及其特点

ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้

国际多元化投资组合 (英文版)International Portfolio Diversification

Key results of portfolio theory

The extent to which risk is reduced by portfolio diversification depends on the correlation of assets in the portfolio.

Foreign bonds U.S. bonds

“Asset Allocation.” Jorion, Journal of Portfolio Management, Summer 1989.

20-16

Return on a foreign asset

Recall Ptd = PtfStd/f (Ptd/Pt-1d) = (1+rd)

20-6

Key results of portfolio theory

The extent to which risk is reduced by portfolio diversification depends on the correlation of assets in the portfolio.

Diversification 20.4 Variances on Foreign Stock and Bond

Investments 20.5 Home Bias 20.6 Summary

20-1

Perfect financial markets ...a starting point

Frictionless markets

- no government intervention or taxes - no transaction costs or other market frictions

多元化折价的解释 Explaining the diversification discount 作者Campa, J

EXPLAINING THE DIVERSIFICATION DISCOUNTJose Manuel Campa Simi KediaStern School of Business Graduate School of Business AdministrationNew York University Harvard University44 West 4th Street Morgan Hall 483New York, NY 10012 Boston, MA 02163Phone: (212)998-0429Phone: (617)495-5057Email: jcampa@ Email: skedia@First Draft: November 1998Current Draft: September 2001ABSTRACTDiversified firms trade at a discount relative to similar single-segment firms. We argue in this paper that this observed discount is not per se evidence that diversification destroys value. Firms choose to diversify. Firm characteristics, which make firms diversify, might also cause them to be discounted. Not taking into account these firm characteristics might wrongly attribute the observed discount to diversification. Data from the Compustat Industry Segment File from 1978 to 1996 is used to select a sample of single segment and diversifying firms. We use three alternative econometric techniques to control for the endogeneity of the diversification decision. All three methods suggest the presence of self-selection in the decision to diversify and a negative correlation between firm's choice to diversify and firm value. The diversification discount always drops, and sometimes turns into a premium, when we control for the endogeneity of the diversification decision. We do a similar analysis in a sample of refocusing firms. Again, some evidence of self-selection by firms exists and we now find a positive correlation between firm's choice to refocus and firm value. These results consistently suggest the importance of taking the endogeneity of the diversification status into account, in analyzing its effect on firm value.We thank Philip Berger, Ben Esty, Stuart Gilson, Bill Greene, Charles Himmelberg, Kose John, Vojislav Maksimovic, Scott Mayfield, Richard Ruback, Henri Servaes Myles Shaver, Jeremy Stein, Emilio Venezian and seminar participants at Harvard Business School, 1999 Western Finance Association Meetings at Los Angeles, NBER Summer Conference in Corporate Finance, 2001 European Finance Association meetings at Barcelona, 2001 European Financial Management Association Meetings in Lugano, Cornell University, Georgetown University and Rutgers for helpful comments. We thank Chris Allen and Sarah Eriksen for help with the data. Simi Kedia gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Division of Research at Harvard Business School. All errors remain our responsibility.Firms choose to diversify. They choose to diversify when the benefits of diversification outweigh the costs of diversification and stay focused when they do not. The characteristics of firms that diversify, which make the benefits of diversification greater than the costs of diversification, may also cause firms to be discounted. A proper evaluation of the effect of diversification on firm value should take into account the firm-specific characteristics, which bear both on firm value and on the decision to diversify.Research by Lang and Stulz (1994), Berger and Ofek (1995) and Servaes (1996) show unambiguously that diversified firms trade at a discount relative to non-diversified firms in their industries. Other research confirms the existence of this discount on diversified firms and this result seems to be robust to different time periods and different countries.1 There is a growing consensus that the discount on diversified firms implies a destruction of value on account of diversification i.e. on account of firms operating in multiple divisions.This study shows that the failure to control for firm characteristics which lead firms to diversify and to be discounted, may wrongly attribute the discount to diversification instead of the underlying characteristics. For example, consider a firm facing technological change, which adversely affects its competitive advantage in its industry. This poorly performing firm will trade at a discount relative to other firms in the industry. Such a firm will also have lower opportunity costs of assigning its scarce resources in other industries, and this might lead it to diversify. If poorly performing firms tend to diversify, then not taking into account past performance and its effect on the decision to diversify will result in attributing the discount to diversification activity rather than to the poor performance of the firm.1 Servaes (1996) finds a discount for conglomerates during the 1960’s while Matsusaka (1993) documents gains to diversifying acquisitions in the late 1960's, in the United States. Lins and Servaes (1999) document a significant discount in Japan and UK, though none exists for Germany. The evidence from emerging economies is mixed. While Khanna and Palepu (1999), Fauver, Houston and Naranjo (1998) find little evidence of a diversificationAlso consider the case of a firm that possesses some unique organizational capability that it wants to exploit. Incomplete information may force this firm to enter into costly search through diversification to find industries with a match to its organizational capital. Matsusaka (1995) proposes a model in which a value maximizing firm forgoes the benefits of specialization to search for a better match. During the search period the market value of the firm will be lower than the value of a comparable single segment firm. Maksimovic and Philips (1998) also develop a model where the firm optimally chooses the number of segments in which it operates depending on its comparative advantage. Not taking into account firm characteristics, which make diversification optimal, in this case searching for a match, may again attribute the discount wrongly to value destruction arising from diversification.This does not imply that there are no agency costs associated with firms operating in multiple divisions. Consider the impact of cross sectional variation in private benefits of managers. A firm with a manager who has high private benefits will undertake activities, which are at conflict with shareholder value maximization. Such a firm will be discounted relative to other firms in its industry. Such a manager is also more likely to undertake value-destroying diversification. However, even in this case the observed discount on multi-segment years is partially accounted for by the ex ante discount at which the firm is trading, on account of high private benefits, before diversification. Not taking into account firm characteristics, in this case high agency costs, leads to an over estimation of the value destruction attributed to diversification.In this paper, we attempt to control for this endogeneity of firm’s decision to diversify in evaluating the effect of diversification on firm value. The arguments suggest that the decision todiscount in emerging markets, Lins and Servaes (1998) report a diversification discount in a sample of firms from seven emerging markets.diversify depends on the presence of some firm-specific characteristics that lead some firms to generate more value from diversification than others. Choice of organization structure should therefore be treated as an endogenous outcome that maximizes firm value, given a set of exogenous determinants of diversification i.e. the set of firms characteristics. Evaluating the impact of diversification on firm value therefore requires taking into account the endogeneity of the diversification decision.Controlling for the endogeneity of the diversification decision requires identifying variables that affect the decision to diversify while being uncorrelated with firm value. This becomes difficult as most variables that bear on the diversification decision also impact firm value. We build on the methodology of Berger and Ofek (1995) and the insights of Lang and Stulz (1994) to control for the endogeneity of the diversification decision. As Berger and Ofek (1995), we value firms relative to the median single segment firm in the industry. This measure has the advantage of being neutral to industry and time shocks that affect all firms in a similar way. However, Lang and Stulz (1994) show that industry characteristics are important in firm's decision to diversify.2 We explore the data for systematic industry differences among single-segment and diversifying firms that might help explain the decision to diversify.We first reproduce the results existing in the literature and identify a diversification discount in our sample. Preliminary data analysis shows that conglomerates differ from single segment firms in their underlying characteristics. We control for the endogeneity of the diversification decision in three ways. Firstly, we control for unobservable firm characteristics that affect the diversification decision by introducing fixed firm effects. Secondly, we model the firm's decision to diversify as a function of industry, firm and macroeconomic characteristics.We use the probability of diversifying as an instrument for the diversification status in evaluating the effect of multiple segment operations on firm value. Lastly, we model an endogenous self-selection model and use Heckman's correction to control for the self-selection bias induced on account of firm's choosing to diversify.The diversification discount always drops, and sometimes turns into a premium, when we control for the endogeneity of the diversification decision. The evidence in all three methods indicates that the discount on multiple segment firm-years is partly due to endogeneity. The coefficient of the correction for self-selection is negative, indicating that there is a negative correlation between a firm's choice to diversify and firm value. This supports the view that firm characteristics, which cause firms to diversify, also cause them to be discounted.Finally, we do a similar analysis in a sample of refocusing firms. Comment and Jarrell (1995), John and Ofek (1995) and Berger and Ofek (1996) document an increase in firm value associated with the decision to refocus. Much like the decision to diversify, the decision to refocus is also endogenous: Firms choose to refocus when the presence of firm-specific characteristics, make the benefits of refocusing greater than the costs of refocusing.3 Consider the case when changes in industry conditions generate higher than expected growth opportunities in one segment. This might increase the cost of an inefficient internal capital markets, increasing the cost of operating in multiple divisions and making refocusing optimal. In this case firm characteristics, which make the refocusing decision optimal, i.e. growth opportunities, also cause 2 Lang and Stulz (1994) find that firms that diversify tend to be in slow growing industries. They also report that diversified firms have lower Tobin's q than focused firms, but this difference was driven by differences among firms across industries rather than within an industry.3 In a static model, the above arguments would suggest that when the net benefit to operating in multiple segments is negative, the firm should immediately refocus. In practice, the decision to diversify and refocus involve large amounts of sunk and irreversible costs that lead to a lot of persistence in diversification status. There is yet, no clear understanding of the dynamic theory of firm's diversification status but one can draw an analog from recent theory on irreversible investment decisions (see Dixit and Pindyck (1994). This literature has emphasized that temporarythe firms to be more highly valued. Unlike the diversification decision, the refocusing decision is positively correlated with firm value. Not taking into account firm characteristics prior to refocusing, in this case growth opportunities, may erroneously attribute the associated premium to multi-segment operations of firms. This would lead to an underestimation of the discount associated with multi-segment operations prior to refocusing. Controlling for firm characteristics, which make the refocusing decision optimal, may further increase the discount associated with multi-segments operations of these firms. We document evidence in support of this view.The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In the next section we briefly discuss related literature. Section III describes the data, sample selection criteria and preliminary analysis. Section IV discusses the estimation methodology. Section V presents the evidence for diversifying firms and Section VI does the same for refocusing firms. Section VII concludes.II. RELATED LITERATUREThere is a vast and well-developed literature on the benefits and costs of diversification. The gains from diversification could arise from many sources. Gains to diversification arise from managerial economies of scale as proposed by Chandler (1977) and from increased debt capacity as argued by Lewellen (1971). Diversified firms also gain from more efficient resource allocation through internal capital markets. Weston (1970) argues that the larger internal capital markets in diversified firms help them allocate resources more efficiently. Stulz (1990) shows that larger internal capital markets help diversified firms reduce the under investment problem described by Myers (1977). Stein (1997) argues that the winner picking ability of headquartersshocks can have permanent effects due to hysteresis, which is consistent with an observed discount of multiple segment firms prior to refocusing.may allow internal capital markets in diversified firms to work more efficiently than external capital markets. Gains to diversification also arise from the ability of diversified firms to internalize market failures. Khanna and Palepu (1999) document gains to business group affiliation in India and emphasize the role of diversified groups in replicating the functions of institutions that are missing in emerging markets. Hadlock, Ryngaert and Thomas (1998) argue that diversified firms gain from a reduction of the adverse selection problem at the time of equity issues. Montgomery and Wernerfelt (1988), Matsusaka and Nanda (1994) and Bodnar, Tang and Weintrop (1998) propose gains to diversification based on the presence of firm specific assets, which can be exploited in other markets. Schoar (1999) finds that diversified firms are more productive than within their industry on average, though they still appear to be discounted.There are costs to diversification as well. The costs can arise from inefficient allocation of capital among divisions of a diversified firm. Stulz (1990) and Scharfstein (1998) show that diversified firms invest more than single segment firms in the poor lines of business or in businesses with low Tobin’s q. Lamont (1997) and Rajan, Servaes and Zingales (1997) also report evidence on inefficient allocation of capital within conglomerates. Meyer, Milgrom and Roberts (1992) make a related argument of cross subsidization of failing business segments. The difficulty of designing optimal incentive compensation for managers of diversified firms, also generate costs of multi-segment operations. Aron (1988, 1989), Rotemberg and Saloner (1994) and Hermalin and Katz (1994) show the greater difficulty of motivating managers in diversified firms in comparison to focused firms. Information asymmetries between central management and divisional managers will also lead to higher costs of operating in multiple segments, as has been shown by Myerson (1982) and Harris, Kriebel and Raviv (1982). Lastly, costs of operating in multiple segments could arise on account of increased incentive for rent seeking by managerswithin the firm (see Scharfstein and Stein (1997)) and opportunities for managers of firms with free cash flow to engage in value destroying investments (see Jensen (1986), (1988)). Denis, Denis and Sarin (1997) provide empirical evidence that agency costs are related to the diversification decision. They find that the level of diversification is negatively related to managerial ownership. Hyland (1999) examines firm characteristics including agency costs, and finds no support that agency costs explain the decision of firm’s to diversify.Our focus in the paper is not in identifying any of the above mentioned individual benefits and costs of diversification, but rather to concentrate on the net gain to diversification. Firms are likely to diversify when there are net gains to diversification and stay focused when there are net costs to diversifying. Most importantly for us the above research shows that the benefits and costs of diversification are related to firm-specific characteristics. We control for firm characteristics, which cause firms to diversify i.e. which generate a net gain to multi-segment operations, and isolate the net impact of the diversification decision.Our paper is not the first to take into account the endogeneity of the diversification decision. A growing theoretical literature has been modeling the decision to diversify as a value increasing strategy for the firm. Matsusaka (1995) develops a model in which the firm chooses to diversify when the gains from searching for a better organizational fit outweigh the costs of reduced specialization. Fluck and Lynch (1999) propose that diversification allows marginally profitable projects, which could not get financed as stand-alone entities, to get financed. Perold (1999) models the diversification decision in financial intermediaries and shows that diversification reduces firm’s deadweight costs of capital and so permits divisions to operate on a larger scale than stand-alone firms. Maksimovic and Philips (1998) also develop a model where the firm optimally chooses the number of segments in which it operates, depending on itscomparative advantage. They further show empirically that conglomerates allocate resources optimally, based on the relative efficiency of divisions.There has been other recent empirical work that provides evidences in support of the importance of selection bias and the endogeneity of the diversification decision. Chevalier (2000) finds that even prior to merging, diversifying firms display investment patterns that could be identified as cross subsidization. Whited (1999) finds that after controlling for the measurement problems in Tobins Q , there is no evidence of inefficient allocation of resources in diversified firms. Graham, Lemmon and Wolf (1999) propose that diversified firms are discounted because they acquire discounted firms and Villalonga (2000) finds that with a suitable benchmark the diversification discount diappears.III. DATA3.1 Sample SelectionThe sample consists of all firms with data reported on the Compustat Industry Segment database from 1978 to 1996. We follow the Berger and Ofek (1995) [from here on BO(95)] sample selection criteria and exclude from the sample years where firms report segments in financial sector (SIC 6000-6999), years with sales less than $20 million, years with a missing value of total capital and years in which the sum of segment sales deviated from total sales by more than 1%.4 Additionally, we also excluded years where the firm did not report four-digit SICs for all its segments. The final sample consists of 8,815 firms with a total of 58,965 firm years.3.2 Measure of Excess Value4 Years with segments in the financial services were excluded on account of the difficulty in valuing financial firms using multipliers. Years with sales less than 20 million dollars were excluded to prevent distortions caused by including very small firms.To examine whether diversification increases or decreases value, we use the excess value measure developed by BO (95), which compares a firm's value to its imputed value if each of its segments operated as single segment firms. Each segment of a multiple-segment firm is valued using median industry sales and asset multipliers of single segment firms. The imputed value of the firm is the sum of the segment values. Excess value is defined as the log of the ratio of firm value to imputed value. Negative excess value implies that the firm trades at a discount while positive excess values are indicative of a premium.53.3 Documenting the DiscountIn this section, we document the existence of a discount in line with prior work. We find that the median discount on multi-segment years is 10.9% (11.6%) using sales (asset) multipliers for the entire sample from 1978 to 1996 similar to the discount of 10.6% (16.2%) reported by BO (95) for the years 1986 to 1991. 6 We begin by estimating a model of excess value as specified by BO (95) so as to guarantee that any differences in the final results are not driven by differences in sample or methodology. They model excess value as a function of firm size,5 The imputed value of a segment is obtained by multiplying segment sales (asset) with the median sales (asset) multiplier of all single segment firm years in that SIC. The sales (asset) multipliers are the median value of the ratio of total capital over sales (assets). Total capital is the sum of market value of equity, long and short term debt and preferred stock. The industry definitions are based on the narrowest SIC grouping that includes at least 5 firms. Extreme excess values, where the natural log of the ratio of actual to imputed value is greater than 1.386 or less than –1.386, were excluded. The imputed value using sales multipliers of about 50% of all firms were based on matches at the four-digit SIC code, 26.5% were based on matches at the three-digit SIC code and 23.5% were based on matches at the two-digit or lower SIC code. The results using asset multipliers are similar. This is in line with the results reported in BO (95) of 44.6% matches at the four-digit level, 25.4% matches at the three-digit level and the 30% matches at the two-digit level or lower. See BO (95) for further details on methodology.6 For the years 1986 to 1991, we find that the median multiple segment discount in our sample is 7.6% (10.3%) using sales (asset) multiplier This difference with the BO (95) results is possibly on account of a difference in sample size. The number of firm years, in the period 1986 to 1991, in our sample is 17875 greater than 16181 reported by BO (95). There are 4565 firms in our sample as opposed to 3659 firms reported by BO (95). Our sample size is larger by 1142 (977) observations when using sales (asset) multiplier regressions. This increase in the sample size could arise on two accounts. Firstly, if firms restate their results such that they are no longer excluded due to one or more sample selection criteria, they might be included in our sample while not being included in BO (95) sample. Secondly, Compustat might add firms to the database along with the data for prior years. The largest category in this group (according to Compustat sources) consists of small firms which trade on OTC markets and are added when they change listing or on client request. Our overall sample, from 1978 to 1996, of 8815 firms andproxied by log of total assets, profitability (EBIT/SALES), investment (CAPX/SALES) and diversification, proxied by D, a dummy which takes the value 1 for years when the firm operates in multiple segments and zero otherwise. As seen in Table I, the coefficient of D is –0.13 (-0.12) and significant at the 1% (1%) level when sales (assets) multipliers are used. When we restrict the sample to the years 1986-1991, the coefficient of D is –0.12 (-0.13) using sales (asset) multipliers which is very close to the value of –0.144 (-0.127) reported by BO (95). The estimated discount in our sample is similar to that documented by BO (95).We test the robustness of the estimated discount to model specification by including lagged values of firm size, profitability and investment. Past profitability and investment may control for firm characteristics, which affect firm value. We also include log of total assets squared to control for the possibility of a non-linear effect of firm size on firm value. The coefficient of the square of firm size, is negative suggesting that the positive effect of firm size on excess value diminishes as firm size increases. We also include the ratio of long-term debt to total assets. The results reported in columns 3 and 6 of Table 1, show that the estimated discount is about 11% with both sales and asset multipliers. There is weak evidence that firm’s with high past profitability (high EBIT/SALES) and high past investments (high CAPX/SALES) are valued higher than the median single segment firm in the industry though the coefficients are not significant. Summarizing, multiple segment firms show a significant discount and this discount is robust to the inclusion of additional variables in the valuation equation. We report all results with this extended model. As a comparison, the results with the basic BO (95) model are similar and are discussed in Sections 5.5 and 6.5.3.4 Are multi-segment firms different?58965 observations is similar to the sample of 8467 firms and 58332 observations reported by Graham, Lemmon and Wolf (1999).In this section, we examine the characteristics of conglomerates, which might cause them to diversify. We also examine if conglomerates differ from single segment firms in their underlying characteristics.The 8,815 firms in our sample differ in their diversification profiles. The largest group consists of 5,387 single segment firms, which accounted for 30,284 firm years, as shown in Table II. The rest are firms which report operating in multiple segments at some point in the time period under consideration. These firms will be referred to as multiple segment firms or conglomerates in the paper. Among these multiple segment firms, there were broadly four kinds: Firms which diversify, those that refocus, those that do both and lastly conglomerate firms which do not change the number of segments in which they operate. The largest group consists of1,371 firms (13,133 firm years) which report both increasing and decreasing the number of segments in this time period. The next largest group consists of 873 firms (7,987 firm years) who refocused. There are 606 firms (4,326 firm years) which report diversifying in this period.7 Next we examine the characteristics of single segment and multiple segment firms years. Table III, reports average value of firm size, investment, profitability, leverage, research and development and industry growth rates for the different diversification profiles. Industry growth rate is the increase in industry sales, defined at the two-digit SIC level. SIC classification was obtained from the business segment data. Divisional sales for conglomerates were included in the respective SIC’s for the calculation of total industry sales.8Single segment years of conglomerates are significantly different from single segment firms in their characteristics. Single segment years of conglomerates are bigger, have higher7 Firms were classified using all available data i.e. the years excluded on account of sample selection criteria were also taken into account for the purpose of categorizing firms. This ensures that restructuring activity in years that were excluded from the sample is also taken into account.leverage and lower R&D than single segment firms. This is consistent with Hyland (1999) who finds that diversifying firms have lower research and development expenses. With regard to CAPX/SALES and EBIT/SALES, not only do single segment years of conglomerates differ from single segment firms, but they also differ significantly among them. Single segment years of diversified firms have higher CAPX/SALES and higher EBIT/SALES while single segment years of refocusing firms and firms which both refocus and diversify, have lower CAPX/SALES and lower EBIT/SALES than single segment firms. In summary, firm characteristics differ across single segment years in different diversification profiles.There are also significant differences in the characteristics of multi-segment years of conglomerates. Multiple segment years of diversifying firms tend to invest more in research and development (RND/SALES) than others. They also have higher capital investment(CAPX/SALES) and higher profitability (EBIT/SALES) than multiple segment years of refocusing firms and firms which both refocus and diversify. Conglomerates that do not change diversification status seem to be in mature industries with lower growth industries, have low research and development costs while enjoying a higher profitability (EBIT/SALES) and higher capital investment (CAPX/SALES). Multiple segment years of refocusing firms tend to have the lowest profitability and capital investment. This suggests that difference in characteristics of multiple segment years might be related to the choice of diversification strategy.Next we examine the characteristics of the discount over time and across the different diversification profiles. Table IVa documents the average annual discount from 1978 to 1996 estimated using sales and asset multipliers. There is substantial variation, with the median discount using sales multipliers being as low as –0.058 in 1982 and zero for years 1987 to 1991.8 Total industry sales is a function of firms entering and leaving Compustat, of restructuring activities of firms as well as accounting changes which cause firms to report sales in different SICs over the years. These growth rates。

政府会计制度下长期股权投资核算及列报问题

理财视耔[5] Hitt M A,HoskissonRE,Kim H.International Diversification:Effects on Innovation and Firm Performance in Product — di—versified FirmsfJ],Academy of Management Journal,1997,40,(4) : 767-798.[6] Drobetz W,Gounopoulos D,Merika A,et al.Determinants of management earnings forecasts:The case of global shipping IPOs[J].European Financial Management, 2017,23(5):975-1015.[7] Richartl C S.Accounting and the credibility of management forecasts[J],Contemporary Accounting Research,1992,9( 1) :33- 45.[8] 王浩,向显湖,许毅.高管经验、高管持股与公司业绩预告行为丨J].现代财经(天津财经大学学报),2015(9) :52-66.[9] 朱永明,李雪.制度环境、内部控制与技术创新[J].财会通讯,2018(33) :71-76.[10] 池国华.企业内部控制规范实施机制构建:战略导向与系统整合[J].会计研究,2009(9) :66-71.[11] 张向丽,池国华.企业内部控制与机构投资者羊群行为:“反向”治理效果及异质性分析[J].财贸研究,20丨9(1):99-110.丨12]曾琦,傅绍正,胡国强.会计诚信影响审计定价吗?—基于管理层业绩预告准确性视角[J].审计研究,2018(6): 105-112.[13] 袁振超,岳衡,谈文峰.代理成本、所有权性质与业绩预告精确度[J].南开管 理评论,2014(3) :49-61.[14] 杨德明,史亚雅.内部控制质量会影响企业战略行为吗?—基于互联网商业模式视角的研究[J].会计研究,2018(2) :69-75.丨15]张艺琼,冯均科,彭珍珍.公司战略变革、内部控制质量与管理层业绩预告[J].审计与经济研究,2019,34 (06):68-77.|16]廖义刚,邓贤琨.业绩预告偏离度、内部控制质量与审计收费丨J】.审计研究,2017(04):56-64.117]高敬忠,周晓苏.管理层持股能减轻自愿性披露中的代理冲突吗—以我国A股上市公司业绩预告数据为例[J].财经研究,2013(11): 123-133.[18] 张娆,薛翰玉,赵健宏.管理层自利、外部监督与盈利预测偏差[J].会计研究,20丨7(丨):32-38+95.[19] 易靖韬,张修平,王化成.企业异质性、高管过度自信与企业创新绩效[J].南开管理评论,2015(6): 101-112.00]赵息,麻环宇,张硕.研发投入管理层预期与营业成本黏性行为—基于中国A股市场的实证研究[J].中国会计评论,20丨6(4):565-580.[21]李常青,陈泽艺,黄玉清.内部控制与业绩快报质量[J].审计与经济研究,2018(1):21-33,P2]李姝,梁郁欣,田马飞.内部控制质量、产权性质与盈余持续性[J].审计与经济研究,2017(1):23-37.作者单位:天津师范大学管理学院河北省农业农村厅财务服务中心(责任编辑:秫黍)自2019年1月1日起,修订后的《政府会计制度》开始正式施行,新旧会计制度的衔接成功落下帷幕双报告”也完成了第一次正式编报。

国际贸易实务双语教程第二版习题参考复习资料