博弈论讲义2

博弈论讲义完整版

第一章 导论

注意两点: 1、是两个或两个以上参与者之间的对策论 当鲁滨逊遇到了“星期五”

石匠的决策与拳击手的决策的区别

第一章 导论

2、理性人假设 理性人是指一个很好定义的偏好,在面临定的约束条 件下最大化自己的偏好。 博弈论说起来有些绕嘴,但理解起来很好理解, 那就是每个对弈者在决定采取哪种行动时,不但要根 据自身的利益的利益和目的行事,而且要考虑到他的 决策行为对其他人可能的影响,通过选择最佳行动计 划,来寻求收益或效用的最大化。

不完全信息静态博弈-贝叶斯纳什均衡 海萨尼(1967-1968)

你 接受 求爱博弈: 品德优良者求爱 求爱者 求爱

100,100

不接受

-50,0 0,0

不求爱 0,0

100x+(-100)(1-x)=0 当x大于1/2时,接受求爱 求爱博弈: 品德恶劣者求爱 求爱者 接受 求爱 不求爱 0,0 你 不接受

问题:什么叫“完全而不完美信息博弈”?

第二章 完全信息静态博弈

一 博弈的基本概念及战略表述 二 占优战略(上策)均衡

三 重复剔除的占优均衡(严格下策反复消去法)

四 划线法

五 箭头法

六 纳什均衡

完全信息静态博弈

完全信息:每个参与人对所有其他参与人的特 征(包括战略空间、支付函数等)完全了解

同样的情形发生在: 公共产品的供给 美苏军备竞赛 经济改革 中小学生减负 ……

第一章 导论-囚徒困境

囚徒困境的性质:

个人理性和集体理性的矛盾; 个人的“最优策略”使整个“系统”处于不利 的状态。

思考:为什么会造成囚徒困境 是否由于“通讯”问题造成了囚徒困境? “要害”是否在于“利己主义”即“个人理 性”?

lecture_2(博弈论讲义GameTheory(MIT))

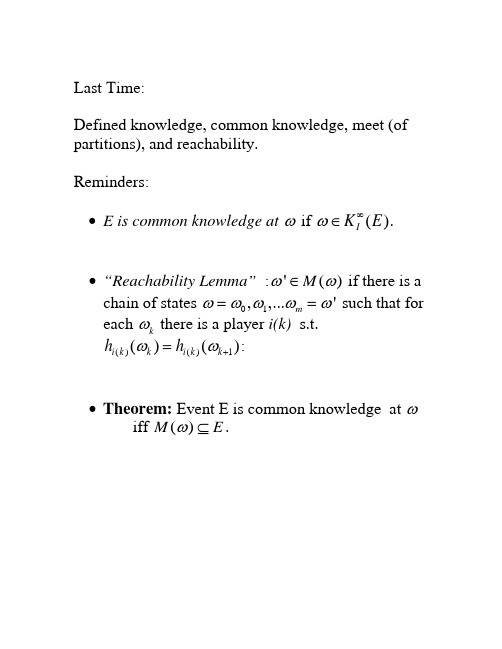

Last Time:Defined knowledge, common knowledge, meet (of partitions), and reachability.Reminders:• E is common knowledge at ω if ()I K E ω∞∈.• “Reachability Lemma” :'()M ωω∈ if there is a chain of states 01,,...m 'ωωωωω== such that for each k ω there is a player i(k) s.t. ()()1()(i k k i k k h h )ωω+=:• Theorem: Event E is common knowledge at ωiff ()M E ω⊆.How does set of NE change with information structure?Suppose there is a finite number of payoff matrices 1,...,L u u for finite strategy sets 1,...,I S SState space Ω, common prior p, partitions , and a map i H λso that payoff functions in state ω are ()(.)u λω; the strategy spaces are maps from into . i H i SWhen the state space is finite, this is a finite game, and we know that NE is u.h.c. and generically l.h.c. in p. In particular, it will be l.h.c. at strict NE.The “coordinated attack” game8,810,11,100,0A B A B-- 0,010,11,108,8A B A B--a ub uΩ= 0,1,2,….In state 0: payoff functions are given by matrix ; bu In all other states payoff functions are given by . a upartitions of Ω1H : (0), (1,2), (3,4),… (2n-1,2n)... 2H (0,1),(2,3). ..(2n,2n+1)…Prior p : p(0)=2/3, p(k)= for k>0 and 1(1)/3k e e --(0,1)ε∈.Interpretation: coordinated attack/email:Player 1 observes Nature’s choice of payoff matrix, sends a message to player 2.Sending messages isn’t a strategic decision, it’s hard-coded.Suppose state is n=2k >0. Then 1 knows the payoffs, knows 2 knows them. Moreover 2 knows that 1knows that 2 knows, and so on up to strings of length k: . 1(0n I n K n -Î>)But there is no state at which n>0 is c.k. (to see this, use reachability…).When it is c.k. that payoff are given by , (A,A) is a NE. But.. auClaim: the only NE is “play B at every information set.”.Proof: player 1 plays B in state 0 (payoff matrix ) since it strictly dominates A. b uLet , and note that .(0|(0,1))q p =1/2q >Now consider player 2 at information set (0,1).Since player 1 plays B in state 0, and the lowest payoff 2 can get to B in state 1 is 0, player 2’s expected payoff to B at (0,1) is at least 8. qPlaying A gives at most 108(1)q q −+−, and since , playing B is better. 1/2q >Now look at player 1 at 1(1,2)h =. Let q'=p(1|1,2), and note that '1(1)q /2εεεε=>+−.Since 2 plays B in state 1, player 1's payoff to B is at least 8q';1’s payoff to A is at most -10q'+8(1-q) so 1 plays B Now iterate..Conclude that the unique NE is always B- there is no NE in which at some state the outcome is (A,A).But (A,A ) is a strict NE of the payoff matrix . a u And at large n, there is mutual knowledge of the payoffs to high order- 1 knows that 2 knows that …. n/2 times. So “mutual knowledge to large n” has different NE than c.k.Also, consider "expanded games" with state space . 0,1,....,...n Ω=∞For each small positive ε let the distribution p ε be as above: 1(0)2/3,()(1)/3n p p n ee e e -==- for 0 and n <<∞()0p ε∞=.Define distribution by *p *(0)2/3p =,. *()1/3p ∞=As 0ε→, probability mass moves to higher n, andthere is a sense in which is the limit of the *p p εas 0ε→.But if we do say that *p p ε→ we have a failure of lower hemi continuity at a strict NE.So maybe we don’t want to say *p p ε→, and we don’t want to use mutual knowledge to large n as a notion of almost common knowledge.So the questions:• When should we say that one information structure is close to another?• What should we mean by "almost common knowledge"?This last question is related because we would like to say that an information structure where a set of events E is common knowledge is close to another information structure where these events are almost common knowledge.Monderer-Samet: Player i r-believes E at ω if (|())i p E h r ω≥.()r i B E is the set of all ω where player i r- believesE; this is also denoted 1.()ri B ENow do an iterative definition in the style of c.k.: 11()()rr I i i B E B E =Ç (everyone r-believes E) 1(){|(()|())}n r n ri i I B E p B E h r w w -=³ ()()n r n rI i i B E B =ÇEE is common r belief at ω if ()rI B E w ¥ÎAs with c.k., common r-belief can be characterized in terms of public events:• An event is a common r-truism if everyone r -believes it when it occurs.• An event is common r -belief at ω if it is implied by a common r-truism at ω.Now we have one version of "almost ck" : An event is almost ck if it is common r-belief for r near 1.MS show that if two player’s posteriors are common r-belief, they differ by at most 2(1-r): so Aumann's result is robust to almost ck, and holds in the limit.MS also that a strict NE of a game with knownpayoffs is still a NE when payoffs are "almost ck” - a form of lower hemi continuity.More formally:As before consider a family of games with fixed finite action spaces i A for each player i. a set of payoff matrices ,:l I u A R ->a state space W , that is now either finite or countably infinite, a prior p, a map such that :1,,,L l W®payoffs at ω are . ()(,)()w u a u a l w =Payoffs are common r-belief at ω if the event {|()}w l w l = is common r belief at ω.For each λ let λσ be a NE for common- knowledgepayoffs u .lDefine s * by *(())s l w w s =.This assigns each w a NE for the corresponding payoffs.In the email game, one such *s is . **(0)(,),()(,)s B B s n A A n ==0∀>If payoffs are c.k. at each ω, then s* is a NE of overall game G. (discuss)Theorem: Monder-Samet 1989Suppose that for each l , l s is a strict equilibrium for payoffs u λ.Then for any there is 0e >1r < and 1q < such that for all [,1]r r Î and [,1]q q Î,if there is probability q that payoffs are common r- belief, then there is a NE s of G with *(|()())1p s s ωωω=>ε−.Note that the conclusion of the theorem is false in the email game:there is no NE with an appreciable probability of playing A, even though (A,A) is a strict NE of the payoffs in every state but state 0.This is an indirect way of showing that the payoffs are never ACK in the email game.Now many payoff matrices don’t have strictequilibria, and this theorem doesn’t tell us anything about them.But can extend it to show that if for each state ω, *(s )ω is a Nash (but not necessarily strict Nash) equilibrium, then for any there is 0e >1r < and 1q < such that for all [,1]r r Î and [,1]q q Î, if payoffs are common r-belief with probability q, there is an “interim ε equilibria” of G where s * is played with probability 1ε−.Interim ε-equilibria:At each information set, the actions played are within epsilon of maxing expected payoff(((),())|())((',())|())i i i i i i i i E u s s h w E u s s h w w w w e-->=-Note that this implies the earlier result when *s specifies strict equilibria.Outline of proof:At states where some payoff function is common r-belief, specify that players follow s *. The key is that at these states, each player i r-believes that all other players r-believe the payoffs are common r-belief, so each expects the others to play according to s *.*ΩRegardless of play in the other states, playing this way is a best response, where k is a constant that depends on the set of possible payoff functions.4(1)k −rTo define play at states in */ΩΩconsider an artificial game where players are constrained to play s * in - and pick a NE of this game.*ΩThe overall strategy profile is an interim ε-equilibrium that plays like *s with probability q.To see the role of the infinite state space, consider the"truncated email game"player 2 does not respond after receiving n messages, so there are only 2n states.When 2n occurs: 2 knows it occurs.That is, . {}2(0,1),...(22,21,)(2)H n n =−−n n {}1(0),(1,2),...(21,2)H n =−.()2|(21,2)1p n n n ε−=−, so 2n is a "1-ε truism," and thus it is common 1-ε belief when it occurs.So there is an exact equilibrium where players playA in state 2n.More generally: on a finite state space, if the probability of an event is close to 1, then there is high probability that it is common r belief for r near 1.Not true on infinite state spaces…Lipman, “Finite order implications of the common prior assumption.”His point: there basically aren’t any!All of the "bite" of the CPA is in the tails.Set up: parameter Q that people "care about" States s S ∈,:f S →Θ specifies what the payoffs are at state s. Partitions of S, priors .i H i pPlayer i’s first order beliefs at s: the conditional distribution on Q given s.For B ⊆Θ,1()()i s B d =('|(')|())i i p s f s B h s ÎPlayer i’s second order beliefs: beliefs about Q and other players’ first order beliefs.()21()(){'|(('),('))}|()i i j i s B p s f s s B h d d =Îs and so on.The main point can be seen in his exampleTwo possible values of an unknown parameter r .1q q = o 2qStart with a model w/o common prior, relate it to a model with common prior.Starting model has only two states 12{,}S s s =. Each player has the trivial partition- ie no info beyond the prior.1122()()2/3p s p s ==.example: Player 1 owns an asset whose value is 1 at 1θ and 2 at 2θ; ()i i f s θ=.At each state, 1's expected value of the asset 4/3, 2's is 5/3, so it’s common knowledge that there are gains from trade.Lipman shows we can match the players’ beliefs, beliefs about beliefs, etc. to arbitrarily high order in a common prior model.Fix an integer N. construct the Nth model as followsState space'S ={1,...2}N S ´Common prior is that all states equally likely.The value of θ at (s,k) is determined by the s- component.Now we specify the partitions of each player in such a way that the beliefs, beliefs about beliefs, look like the simple model w/o common prior.1's partition: events112{(,1),(,2),(,1)}...s s s 112{(,21),(,2),(,)}s k s k s k -for k up to ; the “left-over” 12N -2s states go into 122{(,21),...(,2)}N N s s -+.At every event but the last one, 1 thinks the probability of is 2/3.1qThe partition for player 2 is similar but reversed: 221{(,21),(,2),(,)}s k s k s k - for k up to . 12N -And at all info sets but one, player 2 thinks the prob. of is 1/3.1qNow we look at beliefs at the state 1(,1)s .We matched the first-order beliefs (beliefs about θ) by construction)Now look at player 1's second-order beliefs.1 thinks there are 3 possible states 1(,1)s , 1(,2)s , 2(,1)s .At 1(,1)s , player 2 knows {1(,1)s ,2(,1)s ,(,}. 22)s At 1(,2)s , 2 knows . 122{(,2),(,3),(,4)}s s s At 2(,1)s , 2 knows {1(,2)s , 2(,1)s ,(,}. 22)sThe support of 1's second-order beliefs at 1(,1)s is the set of 2's beliefs at these info sets.And at each of them 2's beliefs are (1/3 1θ, 2/3 2θ). Same argument works up to N:The point is that the N-state models are "like" the original one in that beliefs at some states are the same as beliefs in the original model to high but finite order.(Beliefs at other states are very different- namely atθ or 2 is sure the states where 1 is sure that state is2θ.)it’s1Conclusion: if we assume that beliefs at a given state are generated by updating from a common prior, this doesn’t pin down their finite order behavior. So the main force of the CPA is on the entire infinite hierarchy of beliefs.Lipman goes on from this to make a point that is correct but potentially misleading: he says that "almost all" priors are close to a common. I think its misleading because here he uses the product topology on the set of hierarchies of beliefs- a.k.a topology of pointwise convergence.And two types that are close in this product topology can have very different behavior in a NE- so in a sense NE is not continuous in this topology.The email game is a counterexample. “Product Belief Convergence”:A sequence of types converges to if thesequence converges pointwise. That is, if for each k,, in t *i t ,,i i k n k *δδ→.Now consider the expanded version of the email game, where we added the state ∞.Let be the hierarchy of beliefs of player 1 when he has sent n messages, and let be the hierarchy atthe point ∞, where it is common knowledge that the payoff matrix is .in t ,*i t a uClaim: the sequence converges pointwise to . in t ,*i t Proof: At , i’s zero-order beliefs assignprobability 1 to , his first-order beliefs assignprobability 1 to ( and j knows it is ) and so onup to level n-1. Hence as n goes to infinity, thehierarchy of beliefs converges pointwise to common knowledge of .in t a u a u a u a uIn other words, if the number of levels of mutual knowledge go to infinity, then beliefs converge to common knowledge in the product topology. But we know that mutual knowledge to high order is not the same as almost common knowledge, and types that are close in the product topology can play very differently in Nash equilibrium.Put differently, the product topology on countably infinite sequences is insensitive to the tail of the sequence, but we know that the tail of the belief hierarchy can matter.Next : B-D JET 93 "Hierarchies of belief and Common Knowledge”.Here the hierarchies of belief are motivated by Harsanyi's idea of modelling incomplete information as imperfect information.Harsanyi introduced the idea of a player's "type" which summarizes the player's beliefs, beliefs about beliefs etc- that is, the infinite belief hierarchy we were working with in Lipman's paper.In Lipman we were taking the state space Ω as given.Harsanyi argued that given any element of the hierarchy of beliefs could be summarized by a single datum called the "type" of the player, so that there was no loss of generality in working with types instead of working explicitly with the hierarchies.I think that the first proof is due to Mertens and Zamir. B-D prove essentially the same result, but they do it in a much clearer and shorter paper.The paper is much more accessible than MZ but it is still a bit technical; also, it involves some hard but important concepts. (Add hindsight disclaimer…)Review of math definitions:A sequence of probability distributions converges weakly to p ifn p n fdp fdp ®òò for every bounded continuous function f. This defines the topology of weak convergence.In the case of distributions on a finite space, this is the same as the usual idea of convergence in norm.A metric space X is complete if every Cauchy sequence in X converges to a point of X.A space X is separable if it has a countable dense subset.A homeomorphism is a map f between two spaces that is 1-1, and onto ( an isomorphism ) and such that f and f-inverse are continuous.The Borel sigma algebra on a topological space S is the sigma-algebra generated by the open sets. (note that this depends on the topology.)Now for Brandenburger-DekelTwo individuals (extension to more is easy)Common underlying space of uncertainty S ( this is called in Lipman)ΘAssume S is a complete separable metric space. (“Polish”)For any metric space, let ()Z D be all probability measures on Borel field of Z, endowed with the topology of weak convergence. ( the “weak topology.”)000111()()()n n n X S X X X X X X --=D =´D =´DSo n X is the space of n-th order beliefs; a point in n X specifies (n-1)st order beliefs and beliefs about the opponent’s (n-1)st order beliefs.A type for player i is a== 0012(,,,...)()n i i i i n t X d d d =¥=δD0T .Now there is the possibility of further iteration: what about i's belief about j's type? Do we need to add more levels of i's beliefs about j, or is i's belief about j's type already pinned down by i's type ?Harsanyi’s insight is that we don't need to iterate further; this is what B-D prove formally.Coherency: a type is coherent if for every n>=2, 21marg n X n n d d --=.So the n and (n-1)st order beliefs agree on the lower orders. We impose this because it’s not clear how to interpret incoherent hierarchies..Let 1T be the set of all coherent typesProposition (Brandenburger-Dekel) : There is a homeomorphism between 1T and . 0()S T D ´.The basis of the proposition is the following Lemma: Suppose n Z are a collection of Polish spaces and let021201...1{(,,...):(...)1, and marg .n n n Z Z n n D Z Z n d d d d d --´´-=ÎD ´"³=Then there is a homeomorphism0:(nn )f D Z ¥=®D ´This is basically the same as Kolmogorov'sextension theorem- the theorem that says that there is a unique product measure on a countable product space that corresponds to specified marginaldistributions and the assumption that each component is independent.To apply the lemma, let 00Z X =, and 1()n n Z X -=D .Then 0...n n Z Z X ´´= and 00n Z S T ¥´=´.If S is complete separable metric than so is .()S DD is the set of coherent types; we have shown it is homeomorphic to the set of beliefs over state and opponent’s type.In words: coherency implies that i's type determines i's belief over j's type.But what about i's belief about j's belief about i's type? This needn’t be determined by i’s type if i thinks that j might not be coherent. So B-D impose “common knowledge of coherency.”Define T T ´ to be the subset of 11T T ´ where coherency is common knowledge.Proposition (Brandenburger-Dekel) : There is a homeomorphism between T and . ()S T D ´Loosely speaking, this says (a) the “universal type space is big enough” and (b) common knowledge of coherency implies that the information structure is common knowledge in an informal sense: each of i’s types can calculate j’s beliefs about i’s first-order beliefs, j’s beliefs about i’s beliefs about j’s beliefs, etc.Caveats:1) In the continuity part of the homeomorphism the argument uses the product topology on types. The drawbacks of the product topology make the homeomorphism part less important, but theisomorphism part of the theorem is independent of the topology on T.2) The space that is identified as“universal” depends on the sigma-algebra used on . Does this matter?(S T D ´)S T ×Loose ideas and conjectures…• There can’t be an isomorphism between a setX and the power set 2X , so something aboutmeasures as opposed to possibilities is being used.• The “right topology” on types looks more like the topology of uniform convergence than the product topology. (this claim isn’t meant to be obvious. the “right topology” hasn’t yet been found, and there may not be one. But Morris’ “Typical Types” suggests that something like this might be true.)•The topology of uniform convergence generates the same Borel sigma-algebra as the product topology, so maybe B-D worked with the right set of types after all.。

博弈论(第二章)讲义

纳什均衡的练习(1)

例1:囚徒困境

囚徒B

坦白

不坦白

坦白 囚徒A

不坦白

-5, -5 -8, 0

0, -8 -1, -1

纳什均衡的练习(2)

例2:智猪博弈

大猪

踩

不踩

小猪

踩 不踩

1.5, 3.5 5, 0.5

- 0.5, 6 0, 0

纳什均衡的练习(3)

例2:猜硬币的博弈

猜硬币者

正

反

正 盖硬币者

反

-1, 1 1, -1

博弈方2

U

L

R

U 博弈方1

D

1, 0 0, 3

1, 2 0, 1

0, 1 2, 0

三、划线法

其中心思想是根据博弈方策略之间的相对优劣关系,导 出博弈分析的“划线法”。

例:下图中的得益矩阵表示两博弈方的一个静态博弈,

试使用划线法进行分析。 博弈方2

左

中

右

上 博弈方1

下

1, 0 0, 4

1, 3 0, 2

二、严格下策反复消去法

(1)如果在一个博弈中,不管其它博弈方的策略如何变 化,一个博弈方的某种策略给他带来的得益,总是 比另一种策略给他带来的得益要小,那么称前一种 策略为相对于后一种策略的一个“严格下策” 。

(2)经“反复消去”博弈方的严格下策以后,每个博弈 方

可选策略都缩小为一个策略。因此,每个博弈方都 选择各自剩下的一个策略所组成的策略组合,是这 个博弈的均衡解 。

0, 1 2, 0

划线法的练习(1) 例2:囚徒困境

坦白 囚徒A

不坦白

囚徒B

坦白

不坦白

-5, -5 -8, 0

波恩大学博弈论 讲义 GameT-2

Game Theory Lecture 2A reminderLet G be a finite, two player game of perfect information without chance moves. Theorem (Zermelo, 1913):Either player 1 can force an outcome in T or player 2 can force an outcome in T’A reminder Zermelo’s proof uses Backwards InductionA reminderA game G is strictly Competitive if for any twoterminal nodes a,bab b 2a1An application of Zermelo’s theorem toStrictly Competitive GamesLet a 1,a 2,….a n be the terminal nodes of a strictly competitive game (with no chance moves and with perfectinformation) and let:a n 1a n-1 1 …. 1a 2 1a 1(i.e. a n 2a n-1 2 …. 2a 2 2a 1).?Then there exists k ,n k 1 s.t. player 1 can forcean outcome in a n , a n-1……a kAnd player 2can force an outcome in a k , a k-1……a 1?a n 1a n-1 1.. 1 a k 1 .. 1a 2 1a 1G(s,t)=a kPlayer 1has a strategy swhich forces an outcomebetter or equal to a k ( 1)Player 2has a strategy twhich forces an outcomebetter or equal to a k ( 2)Let w j= a n, a n-1……,a j wn+1=an , an-1…aj…, a2, a1w1w2w jwn+1wnPlayer 1can force an outcome in W 1 = a n , a n-1…,a 1 ,and cannot force an outcome in w n+1= .Let w j = a n , a n-1……,a j w n+1= w 1, w 2, ….w n ,w n+1can force cannot forcecan force ??Let k be the maximal integer s.t. player 1can force an outcome in W kProof :w 1, w 2, … wk , w k+1...,w n+1Player 1 can force Player 1 cannot forceLet k be the maximal integer s.t. player 1can force an outcome in W ka n , a n-1…a k+1 ,a k …, a 2, a 1 w 1w k+1w k Player 2can force an outcome in T -w k+1by Zermelo’s theorem!!!!!a n 1a n-1 1.. 1 a k 1 .. 1a 2 1a 1G(s,t)=a k Player 1has a strategy s which forces an outcome better or equal to a k ( 1)Player 2has a strategy t which forces an outcome better or equal to a k ( 2)Now consider the implications of this result for thestrategic form game s ta kplayer 1’s strategy s guarantees at least a kplayer 2’s strategy t guarantees him at least a k------+++++i.e.at most a k for player 1stak------+++++The point (s,t)is a Saddle pointstak------+++++Given that player 2plays t,Player 1hasno better strategythan sstrategy s is player 1’sbest responseto player 2’s strategy tSimilarly, strategy t is player 2’sbest responseA pair of strategies (s,t)such that eachis a best response to the other isa Nash EquilibriumJohn F. Nash Jr.This definition holds for any game,not only for strict competitive ones12 221WW LWWrlRML121 2Example3R LRrL lbackwards Induction(Zermelo)r( l , r ) ( R, , )2 221WW LWWrlRML1223RLRrLl rAll thosestrategy pairs areNash equilibriaBut there are otherNash equilibria …….( l , r ) ( L,( l , r ) ( L, , )2 221WW LWWrlRML1223RLRrLl rThe strategies obtained bybackwards inductionAre Sub-Game Perfect equilibriain each sub-game they prescribe2 221WW LWWrlRML1223RLRrLl rWhereas, thenon Sub-Game PerfectNash equilibriumprescribes a non equilibrium( l , r ) ( L, , )A Sub-Game Perfect equilibriaprescribes a Nash equilibriumin each sub-gameR. SeltenAwarding the Nobel Prize in Economics -1994Chance MovesNature (player 0),chooses randomly, with known probabilities, among some actions.+ + + = 11/61111111/6123456information setN.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .Payoffs:W (when the other dies, or when the other chosenot shoot in his turn)D (when not shooting)L (when dead)1/61111111/6123456N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .Payoffs:W (when the other dies, or when the other didnot shoot in his turn)D (when not shooting)L (when dead)W D L1/61111111/6123456N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .DDDDDDL222221/61111111/6123456N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .N.S .S .DDDDDDL22222N.S .S .DLN.S .S .DN.S .S .DN.S .S .DN.S .S .D。

博弈论导论 2

图 2-5 军备竞赛

思考:现实生活中还有哪些情况属于囚徒困境? 练习:将团队生产问题模型化成囚徒困境;如何理解囚徒困境与“看不见的手”之间 的矛盾?

2.1.5 走出囚徒困境

从社会福利的角度讲,囚徒困境不是帕累托最优的,但这与理性人的假设并不矛盾。

① ②

这实际上是 Betrand 价格竞争模型。 这是 Hardin(1968)发表在 Science 上但是被经济学引用最多的例子。但是,最近有学者提出了“反公地 悲剧”理论。董志强(2007)启发我使用这个简单的收益矩阵而非复杂的数学模型。 白鲨在线 2

2.3.2 性别战

如图 2-12。两个博弈相同的地方在于:(1)存在多重均衡,而且双方各自偏向一个 均衡;(2)任何一个均衡结果都是帕累托最优的。信念扮演了重要的作用。在这个博弈中, 假设男方是一个有名的拳击手,而女方也知道这点,那么(拳击,拳击)应该是一个均衡结 果,而(芭蕾,拳击)不应该出现。

白鲨在线 5

2.3.4 协调博弈

如图 2-14,史密斯公司和琼斯公司独立地决定选择何种智能手机操作系统。若两家公 司选择同样的操作系统,销售会更好。 特征:存在多重均衡,但是一些均衡帕累托优于另一些均衡,这与性别战和斗鸡博弈 都不同。 提示:一定要注意不同博弈模型的结构性特征,而不是过于关注具体数字。 思考:现实生活中有哪些博弈是性别战、斗鸡博弈和协调博弈?

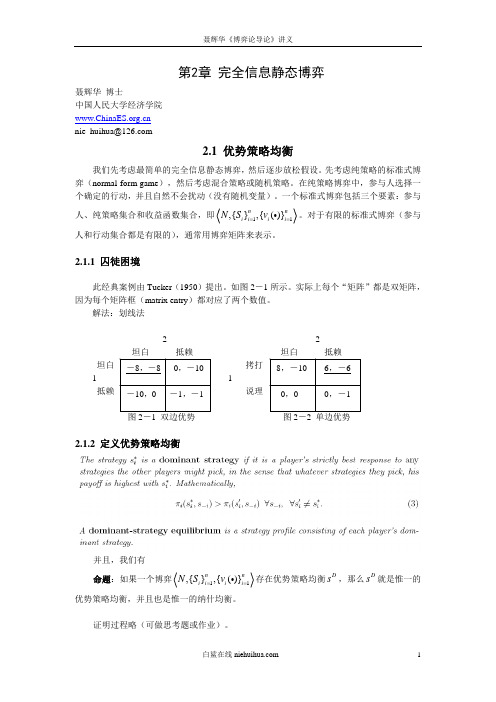

图 2-1 双边优势

图 2-2 单边优势

2.1.2 定义优势策略均衡

并且,我们有 命题:如果一个博弈 N ,{Si }i 1 ,{vi ()}i 1 存在优势策略均衡 s ,那么 s 就是惟一的 优势策略均衡,并且也是惟一的纳什均衡。 证明过程略(可做思考题或作业)。

白鲨在线 1

冯·诺伊曼-摩根斯坦的效用函数

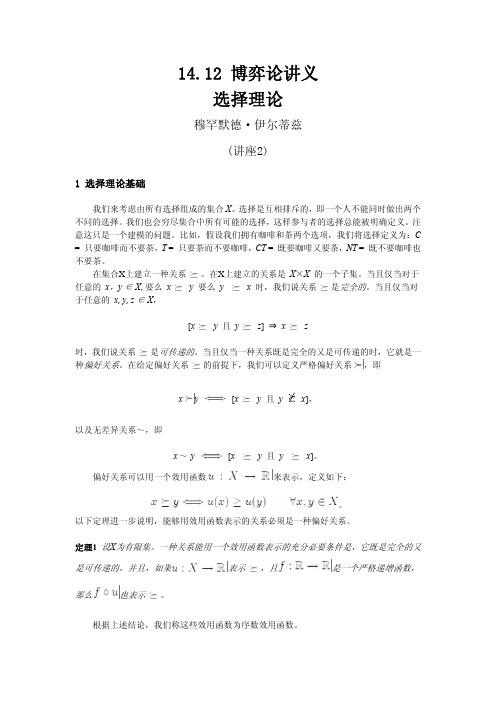

14.12 博弈论讲义选择理论穆罕默德·伊尔蒂兹(讲座2)1 选择理论基础我们来考虑由所有选择组成的集合X。

选择是互相排斥的,即一个人不能同时做出两个不同的选择。

我们也会穷尽集合中所有可能的选择,这样参与者的选择总能被明确定义。

注意这只是一个建模的问题。

比如,假设我们拥有咖啡和茶两个选项,我们将选择定义为:C = 只要咖啡而不要茶,T = 只要茶而不要咖啡,CT = 既要咖啡又要茶,NT = 既不要咖啡也不要茶。

在集合X上建立一种关系。

在X上建立的关系是X×X 的一个子集。

当且仅当对于任意的x,y ∈ X,要么x y要么y x 时,我们说关系是完全的。

当且仅当对∈,于任意的x, y, z X[x y 且y z]⇒x z时,我们说关系是可传递的。

当且仅当一种关系既是完全的又是可传递的时,它就是一种偏好关系。

在给定偏好关系的前提下,我们可以定义严格偏好关系,即x y [x y 且 y x],以及无差异关系~,即x~ y [x y 且y x]。

偏好关系可以用一个效用函数来表示,定义如下:。

以下定理进一步说明,能够用效用函数表示的关系必须是一种偏好关系。

定理1 设X为有限集。

一种关系能用一个效用函数表示的充分必要条件是,它既是完全的又是可传递的。

并且,如果表示,且是一个严格递增函数,那么也表示。

根据上述结论,我们称这些效用函数为序数效用函数。

为了运用选择的序数理论,我们应该了解参与者对各种选择的偏好。

正如我们在上次讲座里所看到的那样,在博弈论中,参与者会在他可能的各种策略中做出选择,而他的策略偏好又有赖于其他参与者所选择的策略。

一般来说,一个参与者并不知道其他参与者选择何种策略。

因此,我们需要一个不确定条件下的决策理论。

2 不确定条件下的决策我们考虑一个由奖金构成的有限集Z,以及由Z上所有概率分布构成的集合P,其中。

我们将这些概率分布称为博彩。

博彩可以用一个树形图来描述。

例如,在图1中,博彩1(lottery 1)描述了这样一种情景:参与者以1/2的概率(比如抛硬币得正面)获得10美元;以1/2的概率(比如抛硬币得到的是反面)获得0美元。

经济博弈论第二讲

▪ 请画出策略组合及得益矩阵,并分析博弈结果。

课后作业2(分析智猪博弈)

▪ 在博弈论经济学中,“智猪博弈”是一个著名例子 ▪ 假设猪圈里有一头大猪,一头小猪。猪圈的一头有猪

食槽,另一头安装着控制猪食供应的按钮,按一下按 钮会有10个单位的猪食进槽,但是谁按按钮就会首先 付出2个单位成本,若大猪先到槽边,大小猪吃到食 物的收益比是9:1;同时到槽边,收益比是7:3;小 猪先到槽边,收益比是6:4。 ▪ 在两头猪都有是有智慧的前提下,请分析猪的选择策 略。

▪ 上策均衡是反映了所有博弈方的绝对偏好,因此 非常稳定。根据上策均衡,就可以对博弈结果作 出最肯定的预测。

▪ 因此,进行博弈分析时,应首先判断各个博弈方是 否都有上策,博弈中是否存在上策均衡。

▪ 上策均衡分析采用的决策思路是一种选择法的思路, 是在所有可选择策略中选出最好的一种的思路。

▪ 因为博弈方的最优策略随其他博弈方的策略而变化 是博弈的根本特征,是博弈关系相互依存性的主要 表现形式,所以上策均衡不是普遍存在的。

1, 0 0, 4

1, 3 0, 2

囚

0, 1

徒

困

2, 0

境

-5, -5 -8, 0

0, -8 -1, -1

▪许多博弈不存在确定性的结果

猜

-1, 1

硬

币

1, -1

1, -1 -1, 1

夫 妻

2, 1

之

0, 0

争

0, 0 1, 3

2.1.4 箭头法

▪ 对博弈中每个策略组合进行分析,考察每个策略组合处各个博弈方 能否通过单独改变自己的策略而增加得益。

博弈论算法讲义

博弈论算法一、博弈的战略式表述及纳什均衡的定义在博弈论里,一个博弈可以用两种不同的方式来表述:一种是战略式表述(strategic form representation ),另一种是扩展式表述(或译为“展开式表述”)(extensive form representation )。

从分析的角度看,战略式表述更适合于静态博弈,而扩展式表述更适合于讨论动态博弈。

1.1博弈的战略式表述战略式表述又称为标准式表述(normal form representation )。

在这种表述中,所参与人同时选择各自的战略,所有参与人选择的战略一起决定每个参与人的支付。

战略式表述给出:1.博弈的参与人集合:(),1,2,,i n ∈ΓΓ=。

2.每个参与人的战略空间:,1,2,,i S i n =。

3.每个参与人的支付函数:12(,,,),1,2,,i n u s s s i n =。

我们用()11,,;,,n n G S S u u =代表战略式表述博弈。

例如在两个寡头产量博弈里,企业是参与人,产量是战略空间,利润是支付;战略式表述博弈为:{}121122120, 0; (,), (,)G q q q q q q ππ=≥≥ (1.1)这里i q 、i π别表示第i 个企业的产量和利润。

1.2纳什均衡的定义有n 个参与人的战略式表述博弈()11,,;,,n n G S S u u =,战略组合{}1,,,,i n s s s s ****=是一个纳什均衡。

如果对于每一个i 、i s *是给定其他参与人选择{}111,,,,,i i i n s s s s s *****--+=的情况下第个参与人的最优战略,即(,)(,),,i i i i i i i i u s s u s s s S i***--≥∀∈∀ (1.2)或者用另一种表述方式,i s *是下述最大化问题的解:111argmax (,...,,,,...,),1,2,..., ;i i i i i n i i s u s s s s s i n s S *****-+∈=∈(1.3)我们用这个定义来检查一个特定的战略组合是否是一个纳什均衡。

博弈论(二)—讲义

9.2 完全信息静态博弈9.2.1 博弈的战略式表述Definition A normal (strategic) form game G consists of: (1) a finite set of agent s . {1,2,,}D n = (2) strategy sets .12,,,n S S S (3) payoff functions . 12:(1,2,,)i n u S S S R i n ⨯⨯⨯→=囚徒B囚徒A完全信息静态博弈是一种最简单的博弈,在这种博弈中,战略和行动是一回事。

博弈分析的目的是预测博弈的均衡结果,即给定每个参与人都是理性的,什么是每个参与人的最优战略?什么是所有参与人的最优战略组合?纳什均衡是完全信息静态博弈解的一般概念,也是所有其他类型博弈解的基本要求。

下面,我们先讨论纳什均衡的特殊情况,然后讨论其一般概念。

9.2.2 占优战略(Dominated Strategies )均衡一般说来,由于每个参与人的效用(支付)是博弈中所有参与人的战略的函数,因此,每个参与人的最优战略选择依赖于所有其他参与人的战略选择。

但是在一些特殊的博弈中,一个参与人的最优战略可能并不依赖于其他参与人的战略选择。

也就是说,不管其他参与人选择什么战略,他的最优战略是唯一的,这样的最优战略被称为“占优战略”。

Definition Strategy s i is strictly dominated for player i if there is some such that i i s S '∈ for al .(,)(,)i i i i i i u s s u s s --'>i i s S --∈Proposition a rational player will not play a strictly dominated strategy.抵赖 is a dominated strategy. A rational player would therefore never 抵赖. This solves the game since every player will 坦白. Notice that I don't have to know anything about the other player . 囚徒困境:个人理性与集体理性之间的矛盾。

博弈论讲义2

三 重复剔除的占优均衡

重复剔除严格劣策略:

思路:首先找到某个参与人的劣策略(假定存 在),把这个劣策略剔除掉,重新构造一个不包 含已剔除策略的新的博弈,然后再剔除这个新的 博弈中的某个参与人的劣策略,一直重复这个过 程,直到只剩下唯一的策略组合为止。 这个唯一剩下的策略组合就是这个博弈的均衡 解,称为“重复剔除的占优均衡”。

独木桥

进

A

退

B

进退 -3,-3 2,0

0,2 0,0

纳什均衡:A进,B退;A退,B进

斗鸡博弈

村子里有两户富户,有两种可能:一家修,另 一家就不修;一家不修,另一家就得修。

冷战期间美苏抢占地盘:一方抢占一块地盘, 另一方就占另一块。

夫妻吵架,一方厉害,另一方就出去躲躲。

注意:在混合策略纳什均衡条件下,也可能两 败俱伤。

注意: 如果所有人都有(严格)占优策略存在,

那么占优策略均衡就是可以预测的唯一 均衡。 占优策略只要求每个参与人是理性的, 而不要求每个参与人知道其他参与人是 理性的(也就是说,不要求理性是共同 知识)。为什么?

二 占优策略均衡

案例-囚徒困境

囚徒A

囚徒 B

坦白

坦白 -8,-8

抵赖

0,-10 -8大于-10

相安无事;第二天,相安无事……;直到第100天 ,突然,每个妻子都把丈夫杀了。为什么会这样?

这是一个推理和行动的过程。如果她的丈夫不忠的话,她就杀 死他;如果没有证据证明她的丈夫不忠的话,她便相信他,不 杀死他。

如果村里只有一个男人是不忠的话,在老太太作了宣布之

后的第一天,这个男人的妻子在老太太宣布之后马上就能知道

两只猪一起去按,然后一起回槽边进食, 由于大猪吃得快可吃下8个单位的食物, 小猪只能吃到2个单位食物。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

尽管许多博弈中重复剔除的占优均衡是一个合理 的预测,但并不总是如此,尤其是大概支付是某 些极端值的时候。

参与人B

L

参与人A

R -1000,9

U

8,10

D

7, 6

6, 5

U是A的最优选择,但是,只要有1/1000的概率B选R, A就会选D

14

斗鸡博弈

进 A 独木桥 纳什均衡:A进,B退;A退,B进 对于相当多的博弈,我们无法运用重复剔除劣战略的 方法找出均衡解。

1、Cournot Model of Duopoly

按竞争程度划分的市场类型(就卖方来说):

A 完全竞争市场 B 寡头竞争市场 C 独家垄断市场

29

市场类型不同,厂商之间行为特征不同,A与C 类型中,厂商的决策都是个体优化决策,而B类 型中寡头垄断竞争的本质就构成博弈,他们都 是理性的决策者,他们的行为既影响自身,又 影响对方。尽管两寡头由于垄断能给他们带来 一些共同的利益,但是他们的根本利益并不是 完全一致的。如果两寡头之间可以签定有约束 力的协议,彼此之间达成合作,形成完全垄断, 此时的博弈是一种合作博弈。然而在大多数情 况下,彼此之间很难达成有约束力的协议,这 样就是非合作博弈。

7

注意:

与占优战略均衡中的占优战略和劣战略不同,

这里的占优战略或劣战略可能只是相对于另一个

特定战略而言。

8

案例1-智猪博弈

小猪 按 大猪 按 5,1 等待 9,-1 等待 4,4 4大于1

0,0

0大于-1

按是小猪的严格 劣战略-剔除 “按”是大猪的占优战略,纳什均衡:大猪按,小猪等待

9

案例2

U 行先生

s * 是一个纳什均衡: 或者用另一种表达方式: 当且仅当 si* 是下述最大化问题的解时,

* si* argmaxui (s1* ,, si*1 , si , si*1 ,, sn ) , i 1,, n

si S i

21

假设n个参与人在博弈之前达成一个协议, 规定每一个参与人选择一个特定的战略, * * * * s ( s , , s , , s 另 1 i n ) 代表这个协议,在没有 外在强制力的情况下,如果没有任何人有 积极性破坏这个协议,则这个协议是自动 实施的。这个协议就构成了一个纳什均衡。

22

通俗地说,纳什均衡的含义就是:

给定你的策略,我的策略是最好的策略; 给定我的策略,你的策略也是你的最好的 策略。即双方在给定的策略下不愿意调整 自己的策略。

23

需求大的情况 开发商A 开发 不开发 需求小的情况

开发商B 开发 不开发

4000,4000 8000,0

0,8000

0,0

开发商B 开发 不开发

u i ( s1*…, sn-1* , si* , sn+1*

,…, sn* )

≥ u (i s1*…, sn-1* , si , sn+1* ,…, sn* ) ……………………………………….(NE)

19

for every feasible strategy si in Si; That is , si*solves max ui( s1*…, sn-1* , si, sn+1* ,…, sn* ). si∈Si

17

4、箭头法

1, 0 0, 3 1, 2 0, 1 0, 1 2, 0

囚 徒 困 境 猜 硬 币

-5, -5 -8, 0

0, -8 -1, -1

夫 妻 之 争

2, 1 0, 0

0, 0 1, 2

-1, 1 1, -1

1, -1 -1, 1

18

2.2 纳什均衡

Definition

In the n-player normal-form game * G={S1 ,… ,Sn ; u1, … , un}, the strategies( S1* …, Sn ) are a Nash equilibrium, if for each player i, si* is (at least tied for (至少不劣于)) player i’s best response to the strategies specified for the n-1 other players, ( s1*…, sn-1* , sn+1* ,…, sn* ):

32

●无限策略博弈NE的求解

按NE定义的条件,如果策略组合( qi* ,qj*) 是NE,那么对于qj*, qi*是下列优化问题的解:

Max ui(qi ,qj*) =Max [-q 2 +(a-c-q *)q ] i j i qi∈Si qi∈Si

d ui d qi

-2qi+ (a-c-qj*)

-5大于-8 0大于-1

-1,-1

抵赖是A的严 格劣战略

3

抵赖是B的严格劣战略

上策(占优战略):不论其他人选择什么战略,

参与人的最优战略是唯一的,这样的最优战略称为

“上策或占优战略”(dominant strategy)。

上策均衡:如果一个博弈的某个策略组合中的所

有策略都是各个博弈方各自的上策,那么这个策略

开发商A

开发

不开发

-3000,-3000 0,1000

1000,0 0,0

博弈的战略式表述

24

寻找纳什均衡

参与人B C1 R1 参与人A R2 R3

0,4 4,0

C2

4,0 0,4

C3

5 ,3 5 ,3

3,5

3,5

6,6

(R3,C3)是纳什均衡

25

练习: 找出下列两对夫妻的纳什均衡

妻子 活着 恩爱夫妻 丈夫 活着 死了

12

举例:

剔除顺序:R3、C3、C2、R2,战略组合(R1,C1)

C1

R1

2,12

C2

1,10

C3

1,12

R2

R3Leabharlann 0,120,120,10

0,10

0,11

0,13

剔除顺序:C2、R2、C1、R3,战略组合(R1,C3)

故一般使用严格劣战略剔除,可以看到,(R1,C3) (R1,C1)都是纳什均衡,但在这里是不可解的。

第二章

完全信息静态博弈

2.1 基本分析思路和方法 2.2 纳什均衡

2.3 无限策略博弈分析和反应函数

2.4 混合策略和混合策略纳什均衡

2.5 纳什均衡的存在性

2.6 纳什均衡的选择和分析方法扩展

1

完全信息静态博弈

完全信息:每个参与人对所有其他参与人的特

征(包括战略空间、支付函数等)完全了解

C3

6,2 3,6 2,8

R3

11

注意:

1、重复剔除的占优均衡结果与劣战略的剔除顺 序是否有关取决于剔除的是否是严格劣战略。 2、重复剔除的占优均衡要求每个参与人是理性 的,而且要求“理性”是参与人的共同知识。 即:所有参与人知道所有参与是理性的,所有参 与人知道所有参与人知道所有参与是理性的

-1, 1 1, -1

1, -1 -1, 1

16

请用上述划线法寻找下列纳什均衡

C1 R1

2,12 0,12 0,12

C2

1,10 0,10 0,10

C3

1,12 0,11 0,13

R2

R3

剔除顺序:C2、R2、C1、R3,战略组合(R1,C3) 剔除顺序:R3、C3、C2、R2,战略组合(R1,C1)

5

案例2-智猪博弈

小猪 按 大猪 等待 4,4 4大于1 0大于-1

按

5,1

等待 9,-1

0,0

等待是小猪的严 格占优战略

大猪有无严格占优战略?

6

2、严格下策反复消去法 (重复剔除的占优均衡)

思路:首先找到某个参与人的劣战略(假定存 在),把这个劣战略剔除掉,重新构造一个不包 含已剔除战略的新的博弈,然后再剔除这个新的 博弈中的某个参与人的劣战略,一直重复这个过 程,直到只剩下唯一的战略组合为止。 这个唯一剩下的战略组合就是这个博弈的均 衡解,称为“重复剔除的占优均衡”。

30

●标准式表述

1、players:厂商1和厂商2 向市场提供无差 异的同质的产品;面临的决策是 qi=? qi Q p ui, 博弈

p是市场出清价格,假设是市场供应量Q的减函数: p=p(Q)=a-Q=a-(qi + qj)

31

2、策略:产出水平qi ,策略集Si={qi : qi ≥0} 3、支付函数: ui(si,sj)= ui(qi,qj) = qip – cqi =qi[a-(qi+qj)] – cqi =- qi2+(a-c- qj) qi 假定两厂商均无固定 成本,只有常数边际 成本c。

上述均衡概念是1951年由数学家约翰· 纳什 (John Nash)首先解释清楚的,所以将他 所解释的均衡称为纳什均衡。

20

定 义 3.6

对 于 n 人 战 略 式 表 述 博 弈 G {S1 ,, S n ; u1 ,, un } , 若 战 略 组 合

* s * (s1* ,, sn ) 满足如下条件,则称 s * 是一个纳什均衡:

* * ) ui (si* , s ) u ( s , s i i i i ) , si S i , i 1,, n (符号“ ”表示“任意的”

即 是 说 如 果 对 于 每 一 个 i 1,, n , si* 是 给 定 其 他 局 中 人 选 择

* * * * * i s ( s , , s , s , , s i 1 i 1 i 1 n ) 的情况下第 个局中人的最优战略。