最新平新乔《微观经济学》18讲彩色答案

平狄克《微观经济学》课后答案 18

CHAPTER 18EXTERNALITIES AND PUBLIC GOODSThis chapter extends the discussion of market failure begun in Chapter 17. To avoid over-emphasis on definitions, stress the main theme of the chapter: the characteristics of some goods lead to situations where price is not equal to marginal cost. Rely on the discussion of market power (Chapter 10) as an example of market failure. Also, point out with each case that government intervention might not be required if property rights can be defined and transaction costs are small (Section 18.3). The first four sections present positive and negative externalities and solutions to market failure. The last two sections discuss public goods and public choice.The consumption of many goods involves the creation of externalities. Stress the divergence between social and private costs. Exercise (5) presents the classic beekeeper/apple-orchard problem, originally popularized in Meade, “External Economies and Diseconomies in a Competitive Situation,” Economic Journal (March 1952). Empirical research on this example has shown that beekeepers and orchard owners have solved many of their problems: see Cheung, “The Fable of the Bees: An Economic Investigation,” Journal of Law and Economics (April 1973).Solutions to the problems of externalities are presented in Sections 18.2 and 18.3. Section 18.2, in particular, discusses emission standards, fees, and transferable permits. Example 18.1 and Exercise (3) are simple applications of these concepts.One of the main themes of the law and economics literature since 1969 is the application of Coase’s insight on the assignment of property rights. The original article is clear and can be understood by students. Stress the problems posed by transactions costs. For a lively debate, ask students whether non-smokers should be granted the right to smokeless air in public places (see Exercise (4)). For an extended discussion of the Coase Theorem at the undergraduate level, see Polinsky, Chapters 3-6, An Introduction to Law & Economics (Little, Brown & Co., 1983).The section on common property resources emphasizes the distinction between private and social marginal costs. Example 18.5 calculates the social cost of unlimited access to common property, and the information provided is used in Exercise (7). Exercise (8) provides an extended example of managing common property.The last two sections focus on public goods and private choice. Point out the similarities and differences between public goods and other activities with externalities. Since students confuse nonrival and nonexclusive goods, create a table similar to the following and give examples to fill in the cells:The next stumbling block for students is achieving an understanding of why we add individual demand curves vertically rather than horizontally. Exercise (6) compares vertical and horizontal summation of individual demand.The presentation of public choice is a limited introduction to the subject, but you can easily expand on this material. A logical extension of this chapter is an introduction to cost-benefit analysis. For applications of this analysis, see Part III, “Empirical Analysis of Policies and Programs,” in Haveman and Margolis (eds.), Public Expenditure and Policy Analysis (Houghton Mifflin, 1983).1. Which of the following describes an externality and which does not? Explain the difference.a. A policy of restricted coffee exports in Brazil causes the U.S. price of coffee to rise,which in turn also causes the price of tea to increase.Externalities cause market inefficiencies by preventing prices from conveying accurateinformation. A policy of restricting coffee exports in Brazil causes the U.S. price ofcoffee to rise, because supply is reduced. As the price of coffee rises, consumers switchto tea, thereby increasing the demand for tea, and hence, increasing the price of tea.These are market effects, not externalities.b. An advertising blimp distracts a motorist who then hits a telephone pole.An advertising blimp is producing information by announcing the availability of somegood or service. However, its method of supplying this information can be distractingfor some consumers, especially those consumers who happen to be driving neartelephone poles. The blimp is creating a negative externality that influences thedrivers’ safety. Since the price charged by the advertising firm does not incorporate theexternality of distracting drivers, too much of this type of advertising is produced fromthe point of view of society as a whole.2. Compare and contrast the following three mechanisms for treating pollution externalities when the costs and benefits of abatement are uncertain: (a) an emissions fee, (b) an emissions standard, and (c) a system of transferable emissions permits.Since pollution is not reflected in the marginal cost of production, its emission createsan externality. Three policy tools can be used to reduce pollution: an emissions fee, anemissions standard, and a system of transferable permits. The choice between a feeand a standard will depend on the marginal cost and marginal benefit of reducingpollution. If small changes in abatement yield large benefits while adding little to cost,the cost of not reducing emissions is high. Thus, standards should be used. However, ifsmall changes in abatement yield little benefit while adding greatly to cost, the cost ofreducing emissions is high. Thus, fees should be used.A system of transferable emissions permits combines the features of fees and standardsto reduce pollution. Under this system, a standard is set and fees are used to transferpermits to the firm that values them the most (i.e., a firm with high abatement costs).However, the total number of permits can be incorrectly chosen. Too few permits willcreate excess demand, increasing price and inefficiently diverting resources to ownersof the permits. Typically, pollution control agencies implement one of threemechanisms, measure the results, reassess the success of their choice, then reset newlevels of fees or standards or select a new policy tool.3. When do externalities require government intervention, and when is such intervention unlikely to be necessary?Economic efficiency can be achieved without government intervention when theexternality affects a small number of people and when property rights are wellspecified. When the number of parties is small, the cost of negotiating an agreementamong the parties is small. Further, the amount of required information (i.e., the costsof and benefits to each party) is small. When property rights are not well specified,uncertainty regarding costs and benefits increases and efficient choices might not bemade. The costs of coming to an agreement, including the cost of delaying such anagreement, could be greater than the cost of government intervention, including theexpected cost of choosing the wrong policy instrument.4. An emissions fee is paid to the government, whereas an injurer who is sued and is held liable pays damages directly to the party harmed by an externality. What differences in the behavior of victims might you expect to arise under these two arrangements?When the price of an activity that generates an externality reflects social costs, anefficient level of the activity is maintained. The producer of the externality reduces (fornegative externalities) or increases (for positive externalities) activity away from(towards) efficient levels. If those who suffer from the externality are not compensated,they find that their marginal cost is higher (for negative externalities) or lower (forpositive externalities), in contrast to the situation in which they would be compensated.5. Why does free access to a common property resource generate an inefficient outcome?Free access to a resource means that the marginal cost to the user is less than the socialcost. The use of a common property resource by a person or firm excludes others fromusing it. For example, the use of water by one consumer restricts its use by another.Because private marginal cost is below social marginal cost, too much of the resource isconsumed by the individual user, creating an inefficient outcome.6. Public goods are both nonrival and nonexclusive. Explain each of these terms and state clearly how they differ from each other.A good is nonrival if, for any level of production, the marginal cost of providing the goodto an additional consumer is zero (although the production cost of an additional unitcould be greater than zero). A good is nonexclusive if it is impossible or very expensiveto exclude individuals from consuming it. Public goods are nonrival and nonexclusive.Commodities can be (1) exclusive and rival, (2) exclusive and nonrival, (3) nonexclusiveand rival, or (4) nonexclusive and nonrival. Most of the commodities discussed in thetext to this point have been of the first type. In this chapter, we focus on commodities ofthe last type.Nonrival refers to the production of a good or service for one more customer. It usuallyinvolves a production process with high fixed costs, such as the cost of building ahighway or lighthouse. (Remember that fixed cost depends on the period underconsideration: the cost of lighting the lamp at the lighthouse can vary over time, butdoes not vary with the number of consumers.) Nonexclusive refers to exchange, wherethe cost of charging consumers is prohibitive. Incurring the cost of identifyingconsumers and collecting from them would result in losses. Some economists focus onthe nonexclusion property of public goods because it is this characteristic that poses themost significant problems for efficient provision.7. Public television is funded in part by private donations, even though anyone with a television set can watch for free. Can you explain this phenomenon in light of the free rider problem?The free-rider problem refers to the difficulty of excluding persons from consuming anonexclusive commodity. Non-paying consumers can “free-ride” on commoditiesprovided by paying customers. Public television is funded in part by contributions.Some viewers contribute, but most watch without paying, hoping that someone else willpay so they will not. To combat this problem these stations (1) ask consumers to assesstheir true willingness to pay, then (2) ask consumers to contribute up to this amount,and (3) attempt to make everyone else feel guilty for free-riding.8. Explain why the median voter outcome need not be efficient when majority rule voting determines the level of public spending.The median voter is the citizen with the middle preference: half the voting population ismore strongly in favor of the issue and half is more strongly opposed to the issue.Under majority-rule voting, where each citizen’s vote is weighted equally, the preferredspending level on public-goods provision of the median voter will win an electionagainst any other alternative.However, majority rule is not necessarily efficient, because it weights each citizen’spreferences equally. For an efficient outcome, we would need a system that measuresand aggregates the willingness to pay of those citizens consuming the public good.Majority rule is not this system. However, as we have seen in previous chapters,majority rule is equitable in the sense that all citizens are treated equally. Thus, weagain find a trade-off between equity and efficiency.1. A number of firms located in the western portion of a town after single-family residences took up the eastern portion. Each firm produces the same product and, in the process, emits noxious fumes that adversely affect the residents of the community.a. Why is there an externality created by the firms?Noxious fumes created by firms enter the utility function of residents. We can assumethat the fumes decrease the utility of the residents (i.e., they are a negative externality)and lower property values.b. Do you think that private bargaining can resolve the problem with the externality?Explain.If the residents anticipated the location of the firms, housing prices should reflect thedisutility of the fumes; the externality would have been internalized by the housingmarket in housing prices. If the noxious fumes were not anticipated, privatebargaining could resolve the problem of the externality only if there are a relativelysmall number of parties (both firms and families) and property rights are well specified.Private bargaining would rely on each family’s willingness to pay for air quality, buttruthful revelation might not be possible. All this will be complicated by theadaptability of the production technology known to the firms and the employmentrelations between the firms and families. It is unlikely that private bargaining willresolve the problem.c. How might the community determine the efficient level of air quality?The community could determine the economically efficient level of air quality byaggregating the families’ willingne ss to pay and equating it with the marginal cost ofpollution reduction. Both steps involve the acquisition of truthful information.2. A computer programmer lobbies against copyrighting software. He argues that everyone should benefit from innovative programs written for personal computers and that exposure to a wide variety of computer programs will inspire young programmers to create even more innovative programs. Considering the marginal social benefits possibly gained by his proposal, do you agree with the programmer’s position?Computer software as information is a classic example of a public good. Since it can becostlessly copied, the marginal cost of providing software to an additional user is nearzero. Therefore, software is nonrival. (The fixed costs of creating software are high, butthe variable costs are low.) Furthermore, it is expensive to exclude consumers fromcopying and using software because copy protection schemes are available only at highcost or high inconvenience to users. Therefore, software is also nonexclusive. As bothnonrival and nonexclusive, computer software suffers the problems of public goodsprovision: the presence of free-riders makes it difficult or impossible for markets toprovide the efficient level of software. Rather than regulating this market directly, thelegal system guarantees property rights to the creators of software. If copyrightprotection were not enforced, it is likely that the software market would collapse.Therefore, we do not agree with the computer programmer.3. Four firms located at different points on a river dump various quantities of effluent into it. The effluent adversely affects the quality of swimming for homeowners who live downstream. These people can build swimming pools to avoid swimming in the river, and firms can purchase filters that eliminate harmful chemicals in the material that is dumped in the river. As a policy advisor for a regional planning organization, how would you compare and contrast the following options for dealing with the harmful effect of the effluent:a. An equal-rate effluent fee on firms located on the river.First, one needs to know the value to homeowners of swimming in the river. Thisinformation can be difficult to obtain, because homeowners will have an incentive tooverstate this value. As an upper boundary, if there are no considerations other thanswimming, one could use the cost of building swimming pools, either a pool for eachhomeowner or a public pool for all homeowners. Next, one needs to know the marginalcost of abatement. If the abatement technology is well understood, this informationshould be readily obtainable. If the abatement technology is not understood, anestimate based on the firms’ knowledge must be used.The choice of a policy tool will depend on the marginal benefits and costs of abatement.If firms are charged an equal-rate effluent fee, the firms will reduce effluents to thepoint where the marginal cost of abatement is equal to the fee. If this reduction is nothigh enough to permit swimming, the fee could be increased. Alternatively, revenuefrom the fees could be to provide swimming facilities, reducing the need for effluentreduction.b. An equal standard per firm on the level of effluent each firm can dump.Standards will be efficient only if the policy maker has complete information regardingthe marginal costs and benefits of abatement. Moreover, the standard will notencourage firms to reduce effluents further when new filtering technologies becomeavailable.c. A transferable effluent permit system, in which the aggregate level of effluent isfixed and all firms receive identical permits.A transferable effluent permit system requires the policy maker to determine theefficient effluent standard. Once the permits are distributed and a market develops,firms with a higher cost of abatement will purchase permits from firms with lowerabatement costs. However, unless permits are sold initially, rather than merelydistributed, no revenue will be generated for the regional organization.4. Recent social trends point to growing intolerance of smoking in public areas. Many people point out the negative effects of “second hand” smoke. If you are a smoker and you wish to continue smoking despite tougher anti smoking laws, describe the effect of the following legislative proposals on your behavior. As a result of these programs, do you, the individual smoker, benefit? Does society benefit as a whole?Since smoking in public areas is similar to polluting the air, the programs proposedhere are similar to those examined for air pollution. A bill to lower tar and nicotinelevels is similar to an emissions standard, and a tax on cigarettes is similar to anemissions fee. Requiring a smoking permit is similar to a system of emissions permits,assuming that the permits would not be transferable. The individual smoker in all ofthese programs is being forced to internalize the externality of “second-hand” smokeand will be worse off. Society will be better off if the benefits of a particular proposaloutweigh the cost of implementing that proposal. Unfortunately, the benefits ofreducing second-hand smoke are uncertain, and assessing those benefits is costly.a. A bill is proposed that would lower tar and nicotine levels in all cigarettes.The smoker will most likely try to maintain a constant level of consumption of nicotine,and will increase his or her consumption of cigarettes. Society may not benefit fromthis plan if the total amount of tar and nicotine released into the air is the same.b. A tax is levied on each pack of cigarettes sold.Smokers might turn to cigars, pipes, or might start rolling their own cigarettes. Theextent of the effect of a tax on cigarette consumption depends on the elasticity ofdemand for cigarettes. Again, it is questionable whether society will benefit.c. Smokers would be required to carry smoking permits at all times. These permitswould be sold by the government.Smoking permits would effectively transfer property rights to clean air from smokers tonon-smokers. The main obstacle to society benefiting from such a proposal would bethe high cost of enforcing a smoking permits system.5. A beekeeper lives adjacent to an apple orchard. The orchard owner benefits from thebees because each hive pollinates about one acre of apple trees. The orchard owner pays nothing for this service, however, because the bees come to the orchard without his having to do anything. There are not enough bees to pollinate the entire orchard, and the orchard owner must complete the pollination by artificial means, at a cost of $10 per acre of trees.Beekeeping has a marginal cost of MC = 10 + 2Q, where Q is the number of beehives.Each hive yields $20 worth of honey.a. How many beehives will the beekeeper maintain?The beekeeper maintains the number of hives that maximizes profits, when marginalrevenue is equal to marginal cost. With a constant marginal revenue of $20 (there is noinformation that would lead us to believe that the beekeeper has any market power)and a marginal cost of 10 + 2Q:20 = 10 + 2Q, or Q = 5.b. Is this the economically efficient number of hives?If there are too few bees to pollinate the orchard, the farmer must pay $10 per acre forartificial pollination. Thus, the farmer would be willing to pay up to $10 to thebeekeeper to maintain each additional hive. So, the marginal social benefit, MSB, ofeach additional hive is $30, which is greater than the marginal private benefit of $20.Assuming that the private marginal cost is equal to the social marginal cost, we setMSB = MC to determine the efficient number of hives:30 = 10 + 2Q, or Q = 10.Therefore, the beekeeper’s private choice of Q = 5 is not the socially efficient number ofhives.c. What changes would lead to the more efficient operation?The most radical change that would lead to more efficient operations would be themerger of the farmer’s business with the beekeeper’s business. This merger wouldinternalize the positive externality of bee pollination. Short of a merger, the farmerand beekeeper should enter into a contract for pollination services.7. Reconsider the common resource problem as given by Example 18.5. Suppose that crawfish popularity continues to increase, and that the demand curve shifts from C = 0.401 - 0.0064F to C = 0.50 - 0.0064F. How does this shift in demand affect the actual crawfish catch, the efficient catch, and the social cost of common access? (Hint: Use the marginal social cost and private cost curves given in the example.)The relevant information is now the following:Demand: C = 0.50 - 0.0064FMSC: C = -5.645 + 0.6509F.With an increase in demand, the demand curve for crawfish shifts upward, intersectingthe price axis at $0.50. The private cost curve has a positive slope, so additional effortmust be made to increase the catch. Since the social cost curve has a positive slope, thesocially efficient catch also increases. We may determine the socially efficient catch bysolving the following two equations simultaneously:0.50 - 0.0064F = -5.645 + 0.6509F, or F* = 9.35.To determine the price that consumers are willing to pay for this quantity, substituteF* into the equation for marginal social cost and solve for C:C = -5.645 + (0.6509)(9.35), or C = $0.44.Next, find the actual level of production by solving these equations simultaneously:Demand: C = 0.50 - 0.0064FMPC: C = -0.357 + 0.0573F0.50 - 0.0064F = -0.357 + 0.0573F, or F** = 13.45.To determine the price that consumers are willing to pay for this quantity, substituteF** into the equation for marginal private cost and solve for C:C = -0.357 + (0.0573)(13.45), or C = $0.41.Notice that the marginal social cost of producing 13.45 units isMSC = -5.645 +(0.6509)(13.45) = $3.11.With the increase in demand, the social cost is the area of a triangle with a base of 4.1million pounds (13.45 - 9.35) and a height of $2.70 ($3.11 - 0.41), or $5,535,000 morethan the social cost of the original demand.8. The Georges Bank, a highly productive fishing area off New England, can be divided into two zones in terms of fish population. Zone 1 has the higher population per square mile but is subject to severe diminishing returns to fishing effort. The daily fish catch (in tons) in Zone 1 isF 1 = 200(X1) - 2(X1) 2where X1is the number of boats fishing there. Zone 2 has fewer fish per mile but is larger, and diminishing returns are less of a problem. Its daily fish catch isF 2 = 100(X2) - (X2) 2where X2is the number of boats fishing in Zone 2. The marginal fish catch MFC in each zone can be represented asMFC1 = 200 - 4(X1) MFC2= 100 - 2(X2).There are 100 boats now licensed by the U.S. government to fish in these two zones. The fish are sold at $100 per ton. The total cost (capital and operating) per boat is constant at $1,000 per day. Answer the following questions about this situation.a. If the boats are allowed to fish where they want, with no government restriction,how many will fish in each zone? What will be the gross value of the catch?Without restrictions, the boats will divide themselves so that the average catch (AF 1and AF 2) for each boat is equal in each zone. (If the average catch in one zone is greaterthan in the other, boats will leave the zone with the lower catch for the zone with thehigher catch.) We solve the following set of equations:AF 1 = AF 2 and X 1 + X 2 = 100 where 11121120022002AF X X X X =-=- and 222222100100AF X X X X =-=-. Therefore, AF 1 = AF 2 implies200 - 2X 1 = 100 - X 2,200 - 2(100 - X 2) = 100 - X 2, or X 21003= and 320031001001=⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛-=X . Find the gross catch by substituting the value of X 1 and X 2 into the catch equations:()(),,,,F 444488983331332002320020021=-=⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛-⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛= and ().,,,F 2222111133333100310010022=-=⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛-⎪⎭⎫ ⎝⎛= The total catch is F 1 + F 2 = 6,666. At the price of $100 per ton, the value of the catch is$666,600. The average catch for each of the 100 boats in the fishing fleet is 66.66 tons.To determine the profit per boat, subtract total cost from total revenue:π = (100)(66.66) - 1,000, or π = $5,666.Total profit for the fleet is $566,000.b. If the U.S. government can restrict the boats, how many should be allocated to eachzone? What will the gross value of the catch be? Assume the total number of boats remains at 100.Assume that the government wishes to maximize the net social value of the fish catch,i.e., the difference between the total social benefit and the total social cost. Thegovernment equates the marginal fish catch in both zones, subject to the restrictionthat the number of boats equals 100:MFC 1 = MFC 2 and X 1 + X 2 = 100,MFC 1 = 200 - 4X 1 and MFC 2 = 100 - 2X 2.Setting MFC 1 = MFC 2 implies:200 - 4X 1 = 100 - 2X 2, or 200 - 4(100 - X 2) = 100 - 2X 2, or X 2 = 50 andX 1 = 100 - 50 = 50.Find the gross catch by substituting X 1 and X 2 into the catch equations:F 1 = (200)(50) - (2)(502) = 10,000 - 5,000 = 5,000 andChapter 18: Externalities and Public Goods242 F 2 = (100)(50) - 502 = 5,000 - 2,500 = 2,500.The total catch is equal to F 1 + F 2 = 7,500. At the market price of $100 per ton, thevalue of the catch is $750,000. Total profit is $650,000. Notice that the profits are notevenly divided between boats in the two zones. The average catch in Zone A is 100 tonsper boat, while the average catch in Zone B is 50 tons per boat. Therefore, fishing inZone A yields a higher profit for the individual owner of the boat.c. If additional fishermen want to buy boats and join the fishing fleet, should agovernment wishing to maximize the net value of the fish catch grant them licenses to do so? Why or why not?To answer this question, first determine the profit-maximizing number of boats in eachzone. Profits in Zone A areππA A X X X X X =--=-1002002100019000200112112b g e j,,, or . To determine the change in profit with a change in X 1 take the first derivative of theprofit function with respect to X 1:d dX X A π1119000400=-,. To determine the profit-maximizing level of output, setd dX A π1equal to zero and solve for X 1:19,000 - 400X 1 = 0, or X 1 = 47.5.Substituting X 1 into the profit equation for Zone A gives: ()()()()()()()()250,451$5.47000,15.4725.472001002=--=A π.For Zone B follow a similar procedure. Profits in Zone B areππB B X X X X X =--=-100100100090002002222222b g e j,,, or . Taking the derivative of the profit function with respect to X 2 givesd X B π229000200=-,. Setting d B π2equal to zero to find the profit-maximizing level of output gives 9,000 - 200X 2 = 0, or X 2 = 45.Substituting X 2 into the profit equation for Zone B gives:πB = (100)((100)(45) - 452) - (1,000)(45) = $202,500.Total profit from both zones is $653,750, with 47.5 boats in Zone A and 45 boats in ZoneB. Because each additional boat above 92.5 decreases total profit, the governmentshould not grant any more licenses.。

平新乔《微观经济学十八讲》课后习题详解(策略性博弈与纳什均衡)

第10讲 策略性博弈与纳什均衡1.假设厂商A 与厂商B 的平均成本与边际成本都是常数,10A MC =,8B MC =,对厂商产出的需求函数是50020D Q p =-(1)如果厂商进行Bertrand 竞争,在纳什均衡下的市场价格是多少? (2)每个厂商的利润分别为多少? (3)这个均衡是帕累托有效吗?解:(1)如果厂商进行Bertrand 竞争,纳什均衡下的市场价格是10B p ε=-,10A p =,其中ε是一个极小的正数。

理由如下:假设均衡时厂商A 和B 对产品的定价分别为A p 和B p ,那么必有10A p ≥,8B p ≥,即厂商的价格一定要高于产品的平均成本。

其次,达到均衡时,A p 和B p 都不会严格大于10。

否则,价格高的厂商只需要把自己的价格降得比对手略低,它就可以获得整个市场,从而提高自己的利润。

所以均衡价格一定满足10A p ≤,10B p ≤。

但是由于A p 的下限也是10,所以均衡时10A p =。

给定10A p =,厂商B 的最优选择是令10B p ε=-,这里ε是一个介于0到2之间的正数,这时厂商B 可以获得整个市场的消费者。

综上可知,均衡时的价格为10A p =,10B p ε=-。

(2)由于厂商A 的价格严格高于厂商B 的价格,所以厂商A 的销售量为零,从而利润也是零。

下面来确定厂商B 的销售量,此时厂商B 是市场上的垄断者,它的利润最大化问题为:max pq cq ε>- ①其中10p ε=-,()5002010q ε=-⨯-,把这两个式子代入①式中,得到:()()0max 1085002010εεε>----⎡⎤⎣⎦解得0ε=,由于ε必须严格大于零,这就意味着ε可以取一个任意小的正数,所以厂商B 的利润为:()()500201010εε-⨯--⎡⎤⎣⎦。

(3)这个结果不是帕累托有效的。

因为厂商B 的产品的价格高于它的边际成本,所以如果厂商B 和消费者可以为额外1单位的产品协商一个介于8到10ε-之间的价格,那么厂商B 的利润和消费者的剩余就都可以得到提高,同时又不损害厂商A 的剩余(因为A 的利润还是零)。

平新乔《微观经济学十八讲》课后习题详解(一般均衡与福利经济学的两个基本定理)

第16讲 一般均衡与福利经济学的两个基本定理1.考虑一种两个消费者、两种物品的交易经济,消费者的效用函数与禀赋如下()()211212,u x x x x = ()118,4e = ()()()21212,ln 2ln u x x x x =+ ()23,6e =(1)描绘出帕累托有效集的特征(写出该集的特征函数式); (2)发现瓦尔拉斯均衡。

解:(1)由消费者1的效用函数()()211212,u x x x x =,可得121122MU x x =,122122MU x x =,故消费者1的边际替代率为1211112212121212122MU x x x MRS MU x x x ===。

同理可得消费者2的边际替代率为22212212x MRS x =。

在帕累托有效集上的任一点,每个消费者消费两种物品的边际替代率都相同,即:121212MRS MRS = 从而有:122212112x x x x = ① 又因为212210x x =-,211121x x =-,把这两个式子代入①式中,就得到了帕累托有效集的特征函数:1122111110422x x x x -=- ② (2)由于瓦尔拉斯均衡点必然位于契约曲线上,所以在均衡点②式一定成立。

此外在均衡点处,预算线和无差异曲线相切(如图16-1所示),这就意味着边际替代率等于预算线的斜率,即:1112121211211418x p x MRS p x x -===- ③联立②、③两式,解得:1158/4x =,1258/11x =。

进而有21112126/4x x =-=,21221052/11x x =-=。

图16-1 均衡时边际替代率等于预算线的斜率2.证明:一个有n 种商品的经济,如果(1n -)个商品市场上已经实现了均衡,则第n 个市场必定出清。

证明:假设第k 种商品的价格为k p ,{}1,2,,k n ∈。

系统内存在I (I 为正整数)个消费者,第i 个消费者拥有第k 种物品的初始禀赋为ik e ,而第i 个消费者对第k 种商品的消费量为k i x ,根据瓦尔拉斯定律可知系统中的超额的市场价值为零,即:()10ni ik k k k i Ii Ip x e =∈∈-=∑∑∑当前1n -个商品市场已经实现均衡,即前1n -个商品市场的超额需求为零,这时有:()()()11n i i i ik k k n k k k i Ii Ii Ii Ii i nkki Ii Ii i k ki Ii Ip x e p x e p x e x e -=∈∈∈∈∈∈∈∈-+-=∑∑∑∑∑-=∑∑=∑∑由此就可以得出第n 个市场的超额需求也为零,即第n 个商品市场也实现了均衡。

平新乔《微观经济学十八讲》课后习题详解(第2讲 间接效用函数与支出函数)

平新乔《微观经济学十八讲》第2讲 间接效用函数与支出函数跨考网独家整理最全经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题解析资料库,您可以在这里查阅历年经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题,经济学考研参考书等内容,更有跨考考研历年辅导的经济学学哥学姐的经济学考研经验,从前辈中获得的经验对初学者来说是宝贵的财富,这或许能帮你少走弯路,躲开一些陷阱。

以下内容为跨考网独家整理,如您还需更多考研资料,可选择经济学一对一在线咨询进行咨询。

1.设一个消费者的直接效用函数为12ln u q q α=+。

求该消费者的间接效用函数。

并且运用罗尔恒等式去计算其关于两种物品的需求函数。

并验证:这样得到的需求函数与从直接效用函数推得的需求函数是相同的。

解:(1)①当20y p α->时,消费者的效用最大化问题为:12122,112m ln ax q q s t q p p yq q q α..+=+构造拉格朗日函数:()121122ln L q q q y p p q αλ--=++L 对1q 、2q 和λ分别求偏导得:1110L p q q αλ∂=-=∂ ① 2210Lp q λ∂=-=∂ ② 11220q Ly p p q λ∂=--=∂ ③ 从①式和②式中消去λ后得:211p q p α*=④再把④式代入③式中得:222y p p q α*-=⑤ 从而解得马歇尔需求函数为:211p q p α*=222y p p q α*-= 由⑤式可知:当20y p α->时,20q *>,消费者同时消费商品1和商品2。

将商品1和商品2的马歇尔需求函数代入效用函数中得到间接效用函数:()()2112122,,,ln p v p p y p q q y u p ααα**=+-=②当20y p α-≤时,消费者只消费商品1,为角点解的情况。

从而解得马歇尔需求函数为:11q y p *=20q *= 将商品1和商品2的马歇尔需求函数代入效用函数中得到间接效用函数:()()12121,,,lnv p p y u q p y q α**== (2)①当20y p α->时,此时的间接效用函数为:()()2112122,,,lnp v p p y p q q yu p ααα**=+-= 将间接效用函数分别对1p 、2p 和y 求偏导得:11v p p α∂=-∂ 2222v y p p p α∂=-∂ 21v y p ∂=∂ 由罗尔恒等式,得到:1112121v p p p v y p q p αα*∂∂=-==∂∂ 22222221y p v p p y p y q v p p αα*-∂∂-=-==∂∂②当20y p α-≤时,间接效用函数为()()12121,,,lnv p p y u q p yq α**==,将间接效用函数分别对1p 、2p 和y 求偏导得:11v p p α∂=-∂ 20v p ∂=∂ v y yα∂=∂ 由罗尔恒等式,得到:1111v p p y v y p y q αα*∂∂=-==∂∂ 2200v p v y yq α*∂∂=-==∂∂ (3)比较可知,通过效用最大化的方法和罗尔恒等式的方法得出的需求函数相同。

平新乔《微观经济学十八讲》课后习题详解(第2讲 间接效用函数与支出函数).doc

平新乔《微观经济学十八讲》第2讲 间接效用函数与支出函数跨考网独家整理最全经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题解析资料库,您可以在这里查阅历年经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题,经济学考研参考书等内容,更有跨考考研历年辅导的经济学学哥学姐的经济学考研经验,从前辈中获得的经验对初学者来说是宝贵的财富,这或许能帮你少走弯路,躲开一些陷阱。

以下内容为跨考网独家整理,如您还需更多考研资料,可选择经济学一对一在线咨询进行咨询。

1.设一个消费者的直接效用函数为12ln u q q α=+。

求该消费者的间接效用函数。

并且运用罗尔恒等式去计算其关于两种物品的需求函数。

并验证:这样得到的需求函数与从直接效用函数推得的需求函数是相同的。

解:(1)①当20y p α->时,消费者的效用最大化问题为:12122,112m ln ax q q s t q p p yq q q α..+=+构造拉格朗日函数:()121122ln L q q q y p p q αλ--=++L 对1q 、2q 和λ分别求偏导得:1110L p q q αλ∂=-=∂ ① 2210Lp q λ∂=-=∂ ② 11220q Ly p p q λ∂=--=∂ ③ 从①式和②式中消去λ后得:211p q p α*=④再把④式代入③式中得:222y p p q α*-=⑤ 从而解得马歇尔需求函数为:211p q p α*=222y p p q α*-= 由⑤式可知:当20y p α->时,20q *>,消费者同时消费商品1和商品2。

将商品1和商品2的马歇尔需求函数代入效用函数中得到间接效用函数:()()2112122,,,ln p v p p y p q q y u p ααα**=+-=②当20y p α-≤时,消费者只消费商品1,为角点解的情况。

从而解得马歇尔需求函数为:11q y p *=20q *=将商品1和商品2的马歇尔需求函数代入效用函数中得到间接效用函数:()()12121,,,lnv p p y u q p yq α**== (2)①当20y p α->时,此时的间接效用函数为:()()2112122,,,lnp v p p y p q q yu p ααα**=+-= 将间接效用函数分别对1p 、2p 和y 求偏导得:11v p p α∂=-∂ 2222v y p p p α∂=-∂ 21v y p ∂=∂由罗尔恒等式,得到:1112121v p p p v y p q p αα*∂∂=-==∂∂ 222222221y p v p p y p y q v p p αα*-∂∂-=-==∂∂②当20y p α-≤时,间接效用函数为()()12121,,,lnv p p y u q p yq α**==,将间接效用函数分别对1p 、2p 和y 求偏导得:11v p p α∂=-∂ 20vp ∂=∂ v y y α∂=∂由罗尔恒等式,得到:1111v p p y v y p y q αα*∂∂=-==∂∂ 2200v p v y yq α*∂∂=-==∂∂ (3)比较可知,通过效用最大化的方法和罗尔恒等式的方法得出的需求函数相同。

微观经济学十八讲答案

微观经济学十八讲答案【篇一:平新乔《微观经济学十八讲》课后习题详解(第13讲委托—代理理论初步)】t>经济学考研交流群点击加入平新乔《微观经济学十八讲》第13讲委托—代理理论初步跨考网独家整理最全经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题解析资料库,您可以在这里查阅历年经济学考研真题,经济学考研课后习题,经济学考研参考书等内容,更有跨考考研历年辅导的经济学学哥学姐的经济学考研经验,从前辈中获得的经验对初学者来说是宝贵的财富,这或许能帮你少走弯路,躲开一些陷阱。

以下内容为跨考网独家整理,如您还需更多考研资料,可选择经济学一对一在线咨询进行咨询。

1.一家厂商的短期收益由r?10e?e2x给出,其中e为一个典型工人(所有工人都假设为是完全一样的)的努力水平。

工人选择他减去努力以后的净工资w?e(努力的边际成本假设为1)最大化的努力水平。

根据下列每种工资安排,确定努力水平和利润水平(收入减去支付的工资)。

解释为什么这些不同的委托—代理关系产生不同的结果。

(1)对于e?1,w?2;否则w?0。

(2)w?r/2。

(3)w?r?12.5。

解:(1)对于e?1,w?2;否则w?0,此时工人的净工资为:?2?ee?1w?e???ee?1?所以e*?1时,工人的净工资最大。

雇主利润为:?*?r?w?10e?e2x?2?10?x?2?8?x工人的净工资线如图13-1所示。

图13-1 代理人的净工资最大化(2)当w?r/2时,工人的净工资函数为:11w?e?5e?e2x?e??e2x?4e22净工资最大化的一阶条件为:d?w?e?de??ex?4?0解得:e??4。

x?2111?4?4??12雇主利润??r?r?r??10?????x??。

222?x?x????xborn to win经济学考研交流群点击加入(3)当w?r?12.5时,工人的净工资函数为:w?e?10e?e2x?12.5?e??e2x?9e?12.5净工资最大化的一阶条件为:d?w?e?de??2ex?9?0解得:e??4.5。

平新乔 微观十八讲习题答案

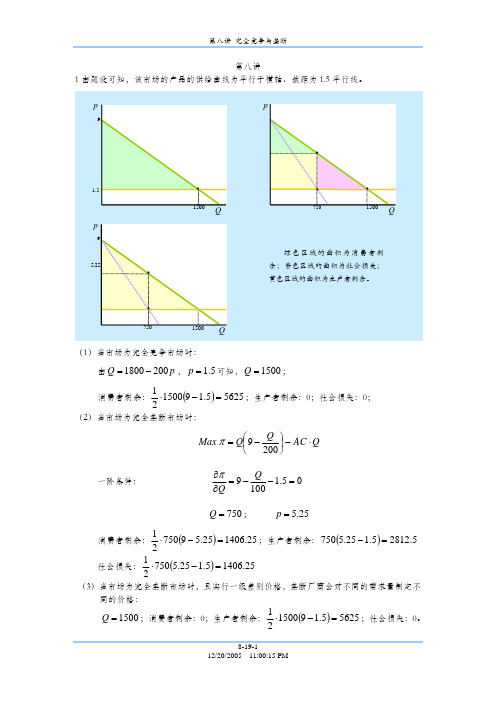

第八讲 完全竞争与垄断

5

Max

π = pQ C

π = (100 qa )qa + (120 2qb )qb 8 20(qa + qb )

一阶条件:

π = 100 2qa 20 = 0 qa π = 120 4qb 20 = 0 qb

q a , qb

s.t.

构造拉氏方程: 一阶条件:

Q = qa + qb

L(q, λ ) = Ca (qa ) + Cb (qb ) + λ (Q qb qa )

L = 8qa λ = 0 qa L = 4qb λ = 0 q2 L = Q qa qb = 0 λ

(1)

(2)

(3)

8-19-5 12/20/2005 11:00:15 PM

一阶条件:

π = 100 4qa 4qb 8qa = 0 qa π = 100 4qa 4qb 4qa = 0 qa

(1)

(2)

qa = 5 ; qb = 10 ; Q = qa + qb = 15 ; p = 70 ; π = 735

另一种解法,先求出成本函数:

min Ca (qa ) + Cb (qb )

Il =

3(1)由霍特林引理 S ( p ) =

1 dp Q 15 9 = = 3 = ∈ dQ p 175 35

π p, k π p, k 1 可得厂商的供给函数: S p, k = = kp p 8 p

( )

( )

( )

(2)由长期均衡可知,企业的长期利润为零, π ( p ) =

p2 1 = 0 ;得 p = 4 16

十八讲平新乔答案

十八讲平新乔答案中级微观经济学(2班)作业四(4月27日上课前交)一、已知一个企业的成本函数为2()1000005016000y TC y y =++,该企业面临的反需求函数为()250400y p y =-,请问:(1)当产量处于什么区间时,该企业的利润为正?)()(y TC y y p TC TR -?=-=π16000411000002001600050100000400250222y y y y y y --=----= 如果让企业的利润为正,必须016000411000002002≥--y y ,解之得:当84775503≤≤y 时企业的利润为正。

(2)当产量处于什么区间时,平均成本上升?当产量处于什么区间时,平均成本下降?企业的平均成本为5016000100000)(++=y y y AC 。

1600011000002+-=??y y AC 。

所以当0≥??yAC ,即40000≥y 时平均成本上升。

当40000<="">由第一小题知企业的总利润是:16000411000002002y y --=π,所以000841200y y -=??π 从而,当0y=??π,即39024=y 时企业的总利润最大。

(4)当产量处于什么水平时,该企业的产出(产量)利润率最高?16000411000002002y y --=π,利润率定义为:1600041100000200)(y y y y --==πρ。

对其利用一阶条件:1600041100000)(2-=??y y y ρ=0,知当95.6246=y 时利润率最高。

(5)当产量处于什么区间时,该企业利润上升?当产量处于什么区间时,企业利润下降?根据第3小题的结论,只当39024≤y 时利润上升,当39024>y 时利润下降。

(6)当产量处于什么水平时,()AVC y 最低?5016000)(+==y y AC y AVC ,所以当0=y 的时候()AVC y 最低。