英语报刊选读 读者文摘原文版INSPIRING STORIES (4)

高考英语复习训练-阅读理解-得分练(含解析)

阅读理解得分练第一节(共15小题;每小题2分,满分30分)阅读下列短文,从每题所给的A、B、C和D四个选项中,选出最佳选项。

A(2022·厦门市第二次质量检测)Letter1Your article mentioned a doctor's visit for“heat and compression”treatment.I bought an inexpensive microwavable moist—heat eye compress online and use it for severalminutes at bedtime to help open the oil glands.Plus,the warmth helps me relax and fall asleep.No more messy washcloth compresses for me!—Julie EvansMinneapolis,MinnesotaLetter2The Quality Inn in Kodak,Tennessee,turning into a shelter during a historic winter storm showed so much kindness that I read the story twice.For Sean Patel to open hishotel to the locals in need during the storm at holiday time at just$25(the lowest pricethe corporate regulations would allow),was priceless.The town is a better place because of Patel and his staff.—Annette WolfeShelton,ConnecticutLetter3You suggested using toothpicks to raise a pot lid and prevent the liquid in the pot from boiling over.I prevent that by just laying a wooden spoon over the open pot.Thespoon will pop most of the bubbles on contact,but it hasn't failed me yet!—Pam SnellgroveLaGrange,GeorgiaLetter4The story about a diver,Carter Viss,who lost his arm after getting hit by a speedboat and then forgave the driver—is among the most compelling stories I've ever read.Here is a story of health and loss,sea and shore,healing and the hope to endure out of thedarkness into the light.Simply marvelous!—Leander JonesNorthport,Alabama 语篇解读:本文是一篇应用文。

读者文摘英文美文——圣诞节故事

What did that mean? I didn’t want her bike—it had the girly bar that sloped down to the ground and a flowery white basket on the handlebars. I could turn it in for a new set of action figures, I figured, but she’d been on it every day since Christmas—no way they’d let me take it back now. I eventually got over it, chalking it up to elf error (the naughty and nice list can be cumbersome).

It’s important to note that while my mom and dad were fantastic parents, they couldn’t be trusted with the awesome responsibility of buying appropriate Christmas presents. They were too quick to pass off gloves, sneakers, and shirts as “presents.” And while we might say a prayer over the Baby Jesus in the manger on our way to church, He seemed too busy at this time of year to leave presents under the tree. We outsourced our requests for the really good presents to Santa.

介绍读者杂志英文作文

介绍读者杂志英文作文英文:As a reader, I would like to introduce a magazine thatI enjoy reading Reader's Digest. This magazine is a monthly publication that features a wide range of articles,including inspiring stories, health tips, and interesting facts.One of the things I love about Reader's Digest is the variety of content. Each issue has something for everyone, whether you're interested in personal finance or travel. I also appreciate the fact that the articles are written in a way that is easy to understand, making it accessible to readers of all ages.Another great feature of Reader's Digest is the jokes and humor section. It's always nice to have a good laugh, and this magazine delivers with its funny stories and jokes.I find myself sharing them with my friends and family allthe time.Lastly, I appreciate the positive and uplifting tone of the magazine. It's refreshing to read stories about people doing good in the world, and it reminds me that there is still kindness and compassion out there.Overall, I highly recommend Reader's Digest to anyone looking for a magazine that is both informative and entertaining.中文:作为一位读者,我想介绍一本我喜欢阅读的杂志——《读者文摘》。

高三英语二轮复习五月美国读者文摘改编语法填空6

2024年五月美国读者文摘改编 练习版语法填空1Roughly 42% of Americans are nearsighted today, 1____________ (pare) to 25% in 1971. The World Health Organization (WHO) predicts that about half of the _____________ (world) population will have myopia, or nearsightedness, by 2050. It’s clear that our vision is being 2____________ (increasing) blurry, 3_________ researchers are only now beginning to understand why. 4______________ (general), a childhood phenomenon, myopia happens when the eyeball grows too long from front to back, 5___________ (take) on more of an oval shape versus a sphere. Eyes have a “stop signal”6_______________ they grow proportionally with the head, explains Gregory Schwartz, 7________ associate professor at the Departments of Ophthalmology and Neuroscience at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. However, that signal can be interrupted by genetic and environmental factors, 8__________ leads to our eyeballs growing a bit too much, 9__________ (make) them too big for the optics (the lens and the cornea, 10_____________ are responsible for focusing your vision).生词注释:1.nearsighted: 近视的2.myopia: 近视3.blurry: 模糊的4.general: 一般来说5.take on: 呈现6.ophthalmology: 眼科学7.neuroscience: 神经科学8.optics: 光学The mismatch between the eyeballs 1_________ the optics leads to faroff objects looking out of focus. Telltale signs you might have myopia also include headaches, as well as eye strain and tiredness when doing certain activities such as driving 2_______ playing sports.While our first instinct is 3________________ (blame) the increased use of screens, experts believe the real reason is not that, exactly, but it’s related: namely less time spent outdoors. Natural light is essential for healthy eye development, says Schwartz. A 2017 study 4______________ (publish) in JAMA Ophthalmology found a correlation between 5___________ (increase) UVB exposure and a decrease in myopia, 6____________ (particular) in children and young adults.Exposure to natural light stimulates dopamine, 7____________ helps regulate normal growth and development of the eyeball. Indoor lighting 8________________ (not do) the trick. Ideally, kids should get at least two hours of natural light a day.That said, our increased use of screens is a problem. Most screens are high contrast—like black text on a white page, or light text on a dark background, says Schwartz. It’s still 9_______ theory, but some scientists think that the contrast of reading a book or looking at a bright screen in a dark room might be overstimulating 10__________ (we) retinas (视网膜), causing more eye growth in children.生词注释:1.mismatch:不匹配2.eyeball:眼球3.optics:光学4.out of focus:失焦5.myopia:近视6.blame:归咎于7.instinct:本能8.UVB:紫外线B9.dopamine:多巴胺10.retina:视网膜My friend Tom runs a whale watch cruise. Recently, his avid whale watcher and friend, Buddy, died. So Tom canceled his nightly cruise and 1_____________ (organize) a private memorial service. More than 80 of Buddy’s friends and family members came to say a last goodbye. Among the passengers 2________ (be) a seriouslooking young woman 3__________ sat quietly by herself and 4___________ no one seemed to know.The service went well, with lots of laughter, a few tears and great 5____________ (story) about Buddy. Then the boat returned to the dock, and, as the young woman departed, Captain Tom thanked her for attending. “6___________ (honest),” she said, “this was the 7____________ (bad) whale watch cruise I have ever been on.”A frantic woman approached my coworker outside of the healthcare facility 8___________ we work. Her dog had escaped from her home while she was out, she said, and was last seen 9___________ (run) near the busy freeway.My coworker and I ran toward the freeway, spotted the dog, and spent the next hour running around until finally catching it. Hot and winded, we returned to work and handed the woman her dog.Fifteen minutes later, she pulled back up.“This isn’t my dog,” she said. “My dog was safe at home.” She then handed us 10________ extra dog and drove off.生词注释:1.whale watch cruise:观鲸游2.avid:热衷的3.memorial service:追悼会4.frantic:焦急的5.healthcare facility:医疗机构6.freeway:高速公路2024年五月美国读者文摘改编 解析版语法填空1Roughly 42% of Americans are nearsighted today, 1____________ (pare) to 25% in 1971. The World Health Organization (WHO) predicts that about half of the _____________ (world) population will have myopia, or nearsightedness, by 2050. It’s clear that our vision is being 2____________ (increasing) blurry, 3_________ researchers are only now beginning to understand why. 4______________ (general), a childhood phenomenon, myopia happens when the eyeball grows too long from front to back, 5___________ (take) on more of an oval shape versus a sphere. Eyes have a “stop signal”6_______________ they grow proportionally with the head, explains Gregory Schwartz, 7________ associate professor at the Departments of Ophthalmology and Neuroscience at the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University. However, that signal can be interrupted by genetic and environmental factors, 8__________ leads to our eyeballs growing a bit too much, 9__________ (make) them too big for the optics (the lens and the cornea, 10_____________ are responsible for focusing your vision).生词注释:1.nearsighted: 近视的2.myopia: 近视3.blurry: 模糊的4.general: 一般来说5.take on: 呈现6.ophthalmology: 眼科学7.neuroscience: 神经科学8.optics: 光学文章翻译:如今,大约42%的美国人患有近视,与1971年的25%相比。

英语报刊杂志课文翻译汇总

第一单元When the University of California at Los Angeles put Rep. Jerry Lewis (R-Calif.) on the cover of this winter’s alumni bulletin, it was a tribute to a distinguished graduate who is so close to his alma mater that he named his dog Bruin, after UCLA’s revered symbol.美国加州大学洛杉矶分校在今年冬季毕业生期刊封面刊登美国国会议员杰尔. 刘易斯(加州共和党人),对与其母校的关系密切得能用美国加州大学洛杉矶分校吉祥物将其宠狗取名为布轮熊的杰出毕业生大肆颂扬。

But the cover story, which was engineered in part by the University of California’s government relation office in Washington, was also a shrewd ploy to cement relations with a key member of the House Appropriations Committee.但是在某种程度上由加州大学华盛顿政府关系办公室策划的这一封面故事也是密切与美国国会众院拨款委员会某一关键委员的精明手段。

As Congress takes up President Bush’s fiscal 2005 budget proposal, which cuts some basic research programs vital to universities, the higher education community is using every lobbying tool at its disposal to protect its interests.在美国国会受理布什总统提交的砍掉了对大学至关重要的一些基本研究计划的2005财政年度预算案之际,高等教育团体无不竭尽游说之能来保护自己的利益。

英美报刊文章选读feature story2

If you ask the question "how and why" things happen, then you probably like reading feature stories in newspapers and magazines. What is a feature story? A feature takes an in-depth look at what’s going on behind the news.

It gets into the lives of people. It tries to explain why and how a trend developed. Unlike news, a feature does not have to be tied to a current event or a breaking story. But it can grow out of something that’s reported in the news.

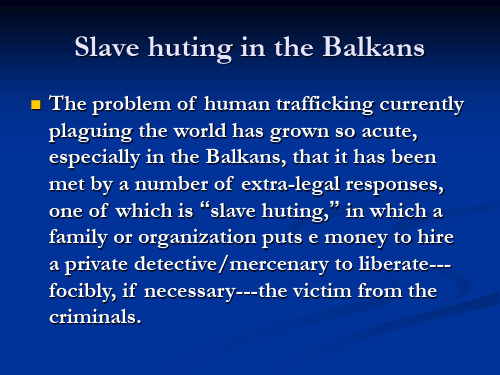

UNICEF estimates that about 1.2 million women and children are trafficked annually. The majority of them are trafficked out of Asia and Eastern Europe, especially the republics of the former Soviet Union. UN officials say that governments who signed onto the global antichild trafficking drive in Japan in 2001 must urgently tackle the root causes of the human slave trade, such as povery and inequality.

《读者杂志》作文翻译英文

《读者杂志》作文翻译英文英文:Reader's Digest is a magazine that has been around for decades, and it has always been a source of inspiration and entertainment for me. The magazine is known for its interesting articles, inspiring stories, and helpful tips, and I always look forward to receiving my monthly subscription.One of the things I love about Reader's Digest is that it covers a wide range of topics. From health and wellness to travel and adventure, there is something for everyone in this magazine. I also appreciate the fact that the articles are written in a way that is easy to understand, even if you are not an expert in the subject matter.Another thing I appreciate about Reader's Digest isthat it features real-life stories of people who have overcome adversity or achieved great things. These storiesare always inspiring and remind me that anything ispossible if you put your mind to it.Overall, I would highly recommend Reader's Digest to anyone who is looking for a magazine that is both entertaining and informative. Whether you are looking for tips on how to live a healthier lifestyle or just want to read some inspiring stories, Reader's Digest has something for you.中文:《读者杂志》是一本我非常喜欢的杂志,它已经存在了几十年,一直是我灵感和娱乐的来源。

Inspiring_readers_to_take_action_激励读者——来自世界的善意

疯狂英语 (新悦读) 主题语境:公益事业 篇幅:351词 建议用时:7分钟 Good Good Good 传媒机构致力于分享世界各地积极向上的故事。

自2017年成立以来,它通过多种平台传递正能量,激励人们在艰难时期寻找并成为助人者,实现“行善”而非仅仅“感善”。

1“We believe that no matter what piece of bad news there is in the world, there s also astory of a helper, somebody who s showing upand making a difference,” says Branden Harvey, founder and chief executive officer of Good Good Good.2 Harvey founded Good Good Good in2017. Before that, he was a professional pho⁃tographer. A lot of his work was with nonprofit organizations. Good Good Good shares stories from around the world. Eight staff members, as well as contributing writers and artists, help Harvey tell inspiring stories about social justice, education and animals, among other topics. The articles in Good Good Good reach people through the organization s web⁃site, email newsletter, podcast, and monthly print newspaper. A digital version of the news⁃paper is available at most libraries in the United States through Libby, a reading app. Good Good Good also provides readers with opportunities to take action, to not just feel good but do good.3Harvey explained why positive stories are important, especially in difficult times. He was inspired by the late Fred Rogers. For several decades, Rogers hosted Mister Rogers Neighborhood , a children s television program. He was known for saying, “When I wasaInspiring readers to take action激励读者——来自世界的善意陕西 吕 品37Crazy English2024.3boy, I would see scary things in the news, and my mother would say to me, ‘Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.’”4Harvey talked about some of the Good Good Good stories that have stayed with him. One is about Terence Lester, an activist and author who was once homeless. Lester started a nonprofit organization called Love Beyond Walls, which provides food, clothing and other resources for people in need. He also created a museum inside a shipping container. The Dignity Museum, which can be transported, helps visitors understand what it s like to experience homelessness. “It s really cool that he s been able to take his personal experience and find a way to make a difference to others,” Harvey said.5Harvey added that stories like Lester s can inspire people to help others. Heencourages young journalists to look for similarly hopeful stories, especially when events make them feel sad, overwhelmed or nervous.Reading CheckInference Detail Detail 1. What is the primary goal of Good Good Good according to Branden Harvey?A. To provide food, clothing and other resources for people in need.B. To focus exclusively on social justice and education issues.C. To share positive stories that motivate readers to take positiveaction.D. To only tell stories related to animals.2. What did Branden Harvey do before founding Good Good Good?A. He was a social justice worker.B. He worked as a professional photographer.C. He worked for a profitable organization.D. He hosted a children s television program.3. Who inspired Branden Harvey to share positive stories?A. Terence Lester. B. His mother.C. Fred Rogers. D. A photographer.38疯狂英语 (新悦读)Detail 4. What did Terence Lester start at first?A. Good Good Good. B. Mister Rogers Neighborhood.C. The Dignity Museum. D. Love Beyond Walls.Language StudyⅠ. 日积月累nonprofit adj . 非营利的podcast n . 播客scary adj. 可怕的journalist n . 记者overwhelmed adj . 不知所措的monthly print newspaper 月刊纸质报纸take action 采取行动Ⅱ. 语法填空Branden Harvey 1. (start) Good Good Good in 2017, aiming to share happyand helpful 2. (story) from all over the world. Before this, he 3. (be) a photographer working with charities. Harvey, along with eight workers and other writers and artists, talks about good things 4. (happen) in topics like fairness in society, school and animals. They spread these stories through 5. (they) website, emails, audio shows and a paper that comes out every month. There is also a way to read the paper on computer or phone using 6. app called Libby in many libraries.Harvey got his idea of looking for the good in life from a famous man, Fred Rogers, 7. made a TV show for kids. Rogers taught kids 8. (look) for kind people when bad things happened. Harvey remembers one story about Terence Lester, a man who was once 9. (home). Lester started Love Beyond Walls to give food and clothes to those 10. need. He also made a museum in a big metal box that tells people what it s like to not have a home. Harvey encourages young reporters to find and share these happy stories, which can make people feel better when they are sad or worried.39。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

A Sailor’s SaviorWhen worried mother Marianne Naslund saw her 16-year-old neighbor Andy Livasy was in trouble, she opened up her heart and home to him.The blistering fights that erupted from the house down the street were legendary in Marianne and Kevin Naslund’s neighborhood. “They echoed off the hillside,” says Marianne. “Everyone got to hear the yelling.” During one particularly nasty fight in February 2008, the neighbors’ 16-year-old son, Andy Livasy, was hit by his stepfather. Watching police cars swarm the street, Marianne realized that she had to help Andy beforehe ran away or “became an angry personwho turned to drugs and alcohol” forcomfort.A few days later, she offered Andy a spoton the Naslunds’ living room couch. Overhis parents’ objections, Andy, who knewMarianne’s sons, Nick, then 15, and Jake,then 13, accepted. No one understood whyMarianne, a dynamo who sat on the Sultan city council and coaches the high school cheerleading squad, would take in a troubled teen like Andy.Then a high school sophomore, Andy scowled at the world from beneath a mess of shaggy blond hair and picked fights with Nick and Jake. At the local high school, he either slept through classes or made them a nightmare for teachers.But Marianne saw herself in Andy. She, too, had grown up in an unsettled household, “with a lot of yelling and not a lot of love.” No matter what, she told people, “kids are not disposable.” Surprisingly, her children understood. “Sometimes Andy could be a downright bully to me,” says Jake, “but when I thought about the future Andy would face if we turned him away, I just couldn’t let myself be a part of that.”It wasn’t easy. For Andy, moving in with the Naslunds was like entering a foreign country of chores and consequences and family dinners—after years of eating most meals alone. “I was used to getting screamed at if I ever messed up, so I was kind of waiting for that,” says Andy. But the day he was suspended from high school for fighting, the screaming and epithets never materialized. Instead, Ma rianne calmly asked why he did it, listened to Andy’s explanation, and declared computers and TV off-limits for the duration of the suspension.“Marianne did it so that instead of fearing a punishment, I didn’t want to let her down,” says Andy. “I didn’t get into another fight for the rest of high school.”With his biological family, Andy had yelled himself into regular migraines. With the Naslunds, his headaches disappeared, along with most of his angry meltdowns. After six months, he asked Kevin to cut his hair. Two years later, he volunteered to coach youth soccer. And though few adults expected it from the boy with the grade-F mouth, in 2010 he graduated on time from Sultan’s alternative high school.“If I hadn’t moved in with the Naslunds, I probably would have dropped out,” Andy says.After four years, Marianne calls Andy her third son, and “if someone asks about my family, I say that he’s one of my brothers,” says Jake. Andy has had no contact with his mom and stepdad since moving out, even though they still live in the neighborhood and say they’re pleased with how their son has turned out. And Andy, who recently joined the Navy, at age 19, knows where he’s heading when he comes home on leave.Says Andy, “What were the chances of my living across the st reet from someone who had a similar childhood, like Marianne, who would take me in and explain, ‘You can change your life around’?”How a Rwandan Teen Overcame a Legacy of GenocideFar from home, in a war-torn land, a charity worker met a child who had every reason to hate—and yet taught volumes about love.He works with the energy and intensity, if not the skill, of a mechanic twice his age. He keeps his head down, focusing on his task, talking to himself—threading greased pedals onto one of 120 sturdy b lack bikes we’re here to build and donate to a Rwandan charity so people can ride to work, to school, to a well with clean water. He looks to be the same age as my third-grade twins. We’ve been working together for an hour in a small auditorium in a walled compound outside Kigali. A choir practices somewhere outside, the ethereal music blending with the clouds that descend down the green ravines of thehills that define Rwanda. Although hespeaks no English and I no Kinyarwanda,we use the universal signs of thumbs-ups,head nods, and “no problem.” We work asa team.And we smile. A lot. The kid has a smilelike no other I’ve seen in more than sixyears of working with African relief agencies to build and donate bikes to charitable groups. I’ve seen lots of hard workers. Lots of incredible people. But there’s something about this one that has a hold, quite unexpectedly, of my heart, more so than the other kids working with volunteers around the compound.Maybe because he’s about the same age as my own three children, a world away in an American suburb. Maybe it’s his warmth, laid bare by a complete absence of any artifice. His eyes glow and his teeth sparkle, and my jet lag melts away as this kid, whose name I don’t know and can’t seem to find out, beams with pride and happiness at finally getting the pedals onto the bike. I give him a thumbs-up, and he beams anew. Over the course of this humid morning, we’ll assemble 15 or so bikes, half of what I could do working alone. But I have a new friend.And he likes me. Anytime we stop work so I can explain something to him, he holds my hand. When we stop for tea, he holds my hand again, and I slip him some Skittles. A woman in traditional dress comes over, ignoring me, and speaks to him sharply, then raps his hand. I’m shocked, but parenting methods are different in central Africa than in New Jersey, so I say nothing as he struggles to hold back tears. Then he takes my hand and pulls me back to the bikes. Within two minutes, he’s beaming, and this time, I’m the one trying to hold back tears.At lunch, I tell Jules Shell, the director of Foundation Rwanda, the charity group we’re working with, what a great hustler we have on our hands. I ask again what his name is. She says, “Well, we call him Jean-Paul. But he doesn’t have a real name.”I must look confused. She smiles a little. “I don’t think his mom could bring herself to call him anything at the time.”I don’t get it, but she continues. “How old do you think he is?” she asks.“Nine, maybe ten,” I say.She looks at me with the tired eyes of a relief worker exhausted by explaining the unexplainable. “He’s 16,” she says. I say it can’t be; he’s tiny. “Sixteen. All these kids are. The genocide was in 1994. Do the math.”At the Vietnam Veterans MemorialOn March 26, 1982, Emogene Cupp stood on a grassy site in Washington, D.C. to take part in a historic event: the breaking of ground for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the luminescent black wall now inscribed with the names of more than 58,000 Americans who were killed inVietnam or remain missing. One of those names belongs to Cupp’s son, Robert. Today, March 26, 2012, she was back to attend an official ceremonycelebrating the memorial’s 30th anniversary. Carrying theshovel she received at the groundbreaking three decadesago, Cupp, now 92, was there to honor her son, who waskilled in June 1968 and buried on his 21st birthday. “I misshim,” she said.On this glorious spring day, Cupp, along with other familymembers, Vietnam veterans, elected officials and decorated war heroes joined Jan C. Scruggs, founder and president of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF), for the commemoration. Speakers, including Brigadier General George B. Price and General Barry McCaffrey, saluted the nation’s servicemen and women, past and present. They lauded the memorial as a place for healing, and applauded the VVMF’s future education center, which will include photos and stories of those who served. Scruggs, who conceived the idea of a memorial and helped raise more than $8 million to bu ild it, told Reader’s Digest, “It’s a great example of three million people who were willing to do what their country asked them to do.” He continued, “These are people who loved their country—and that’s their legacy.”Steve Nelson feels that legacy very personally. Nelson was 19 when he went to serve in Vietnam and Cambodia between April 1969 and October 1970. Eleven men from his unit and his best friend were killed. Among other injuries, Nelson took a bullet in his back and his shoulder. Twenty-five years ago, Nelson spent two nights sleeping in shrubs near the memorial, where he contemplated ending his life. A fellow vet helped save him. Today, he was back to commemorate the wall and the people on it. “I live for these guys, because they didn’t live,” sai d Nelson, now 62, as he pointed to the memorial. “This here makes me feel good.”The Birth of a FamilyDavid Marin was in his early 40s, longing to be a dad.“I’d led an interesting life,” he writes in his new book, “traveled to 11 countries, jumped out of airplanes, graduated from law school, and I’d had three holes in one.” But as a divorced single man, his dream of raising kids eluded him.“At night, I imagined the worst: sittingalone and retired … watching familiesdrive by.” Marin decided to adopt f romfoster care. Although more than 500,000kids are in the foster system in the UnitedStates — one quarter of them available foradoption — the process of winningapproval proved arduous. Marin, who wasvice president of advertising at Pulitzer Newspapers in Santa Maria, California, endured miles of bureaucratic red tape, vetting by two counties, three rounds of fingerprinting, and frustrating delays (a required home-safety class, for instance, was postponed twice). In September 2003, 14 months after he’d first made inquiries about adoption, Social Services called him about three siblings (from the same mother, different fathers —all felons). In December, Marin met the kids. Then came a month of “Family Practice” — weekend and evening visits, with follow-up calls to a social worker.Finally, on February 27, 2004, Marin brought home Craig, two; Adriana, four; and Javier, six, for good. The new family was often met with stares and suspicion (one woman at a restaurant where they were eating called the police, worried that Marin was doing something inappropriate). But the hurdles of this adoption were nothing compared with its joys, says Marin. In this excerpt, he writes about the challenges with his youngest child, Craig, and how, together, he and the kids overcame them.Craig’s life was a cartoon. He was the prey, like Jerry the mouse running away from Tom the cat, or the Road Runner chased by Wile E. Coyote. But two-year-old Craig was neither clever like Jerry nor fast like the Road Runner, so in real life, he probably only whimpered when the predators, his mother and her boyfriends, laid into him. When I first held Craig to smell his baby hair — my dumbbells weighed more than he did — he just held on, waiting for the drop or the throw.Craig didn’t speak; he pointed and grunted. When I told people he didn’t talk, they would ask me his age. After I said he was almost two and a half, they’d turn away. That’s not good, the turning away.He put his clothes on backward and had a hard time keeping up on walks to the Santa Maria river levee, so he rode in the stroller. If we walked for long and his little legs grew tired, I’d hoist him onto my shoulders. He liked heights and a breeze in his face, and when I pushed him in the swing, he wanted to go higher than the clouds, away from it all. He fearlessly climbed the jungle gym, but if a dog came near, he ran toward me until he saw it was a squirrel the dog chased, not him. Nothing was smaller than Craig. He was always looking around; there was danger ahead and behind and, with hawks, above. He could not communicate the truths of his early life, and I had no records or files for him —Social Services didn’t even know his name was Craig; they’d been calling him Chris. He just came along with Javier and Adriana.I worried because he was so frail. During Family Practice, a social worker called me.“Hi, David. Has anyone told you that you have to wake Chris up every night?”“No. His name is Craig.”“Craig? Well, anyway, you have to wake him up every two hours to see if his nose is bleeding. He has bad nosebleeds.”I was game but ill-prepared. One morning I found Craig lying in a pool of blood in his bed. I rushed him to a doctor, who said Craig’s fingernails could be shorter and maybe he was picking his nose. I felt ashamed: It was my job to notice that.To Serve and ProtectHernandez says the real heroes are the doctors, paramedics, and public servants.Daniel Hernandez always knew he wanted to help people. Before he’d even graduated high school, he trained to be a certified nursing assistant and volunteered at a nursing home. A big kid with a gentle, efficient manner, he learned to use needles to draw blood, to lift patients in his strong arms, and to respond swiftly andcalmly to emergencies.He never quite got around to taking theexam to become fully certified, though,because by then he’d decided he wanted towork in public service. He felt inspired bythe good that responsible lawmakers cando, so in his junior year at the Universityof Arizona, he declared a major in politicalscience and began volunteering in political campaigns. One of his heroes was his local congresswoman, Gabrielle Giffords. He’d met Giffords while he was working on Hillary Clinton’spresidential campaign and thought Giffords was not just a trailbla zer but “the kindest, warmest human being you will ever meet in your entire life.”He was elated when he was picked for an internship with her, and he gladly gave up a part-time sales job for the chance to work on her team. So eager was he that he started work four days early. On Saturday morning, January 8, he arrived at La Toscana Village mall north of Tucson and began setting up tables in front of a Safeway store where 30 or so people were gathering to meet Giffords. It was Hernandez’s job to sign people in and guide them into a queue so each could get a photo taken with the congresswoman between an American and an Arizona State flag.At 10:10 a.m., Hernandez heard loud popping sounds. “Gun!” someone yelled. He heard people screaming, saw them falling to the ground. Hernandez was standing 30 feet away from Giffords when she collapsed. In seconds, he was at her side. “When I heard gunfire, I figured there was danger to the congresswoman,” he recalls. “I started toward her.”Everywhere around him was chaos, but Hernandez willed himself to remain calm. “I tried to tune everything out and keep an intense focus. I didn’t want to let my emotions become part of the problem.”Giffords was lying on the sidewalk; blood was streaming down her face from a bullet wound to her head. Gently, Hernandez lifted her into a sitting position against his shoulder so she wouldn’t choke on her blood. Then, with his bare hand, he applied pressure to the wound on her forehead to staunch the flow of blood. She was conscious; he calmed her and told her all would be well. Minutes later, ambulances and paramedics arrived on the scene. Still Hernandez stayed with Giffords, holding her hand and talking. “I just made sure she knew she wasn’t alone,” he says. “When I told her I’d contact [her husband] Mark, she squeezed my hand hard.”Nineteen people fell victim to a deranged man with a deadly weapon that day. Six died. Giffords, though gravely wounded, survived —in no small part because of Hernandez’s quick and selfless actions. Says surgeon Peter Rhee, chief of trauma at University Medical Center in Tucson, where Giffords was taken, Hernandez “was quick to act —he did a heroic thing.”Hernandez never talks about those horrible minutes in a Tucson parking lot without mentioning the people he sees as the real miracle workers: the paramedics and doctors and the public servants who spend their lives helping others —and sometimes give their lives that way. He doesn’t see himself as a hero. The people of Tucson and the nation beg to differ. They’re grateful Daniel Hernandez felt driven to be of service — felt called so strongly, in fact, that he was there at that fateful moment, four days earlier than he was supposed to be. He puts it simply. “Sometimes,” he says, “I wonder if there was a reason for me to be there.”The Memorial Garden MiracleHurricane Irene might have been gentler than expected in some quarters, but in West Hartford, Vermont, it produced a surreal and frightening landscape. The White River jumped its banks and sent waves of contaminated water into nearby homes. Shipping containers, propane tanks, and even entire trucks were spotted washing down the river near Patriots’ Bridge in the middle of the night.Patti and Scott Holmes had a specialconnection to the flood zone. Their son,Marine Lance Cpl. Jeffery Holmes, wasone of three fallen warriors honored on amonument in a memorial garden next to thebridge. Jeffery died on Thanksgiving Day2004 in Fallujah during Operation IraqiFreedom. He was shot in the neck duringan ambush and a rocket-propelled grenade destroyed his legs. Patti took some comfort knowing that her son had perished instantly, serving the military he wanted to join since he was nine years old.The August hurricane spared Patti and Scott’s home. Patti didn’t realize how bad the situation had been at the monument site until one of Jeff’s friends sent a photo the next day. “When I opened it, I just started crying,” she says. All the flowers that volunteers lovingly tended were gone. The granite monument had toppled off its concrete base and was likely ruined. Alone at her desk, Patti wept for the fun-loving blue-eyed son who didn’t live to see his 21st birthday, the boy she still wrote on Christmas and birthdays. Now another piece of him had slipped away.Scott drove to the bridge that night to see exactly what had happened but was forced to turn back. The torrential flooding had destroyed roads, dented railings on the bridge, and propelled a modular home into the middle of a street. Who knows how the angry waters had ravaged the monument? But when Patti and Scott were finally able to get there later in the week, they were greeted with an extraordinary sight. Local residents had returned the monument to its proper place, unharmed. “I didn’t see a scratch, not even on top of it,” Patti marveled in joy and relief.Friends have vowed to help Patti and Scott replant the garden. Come spring, irises, daisies and other flowers in hues of red, white, and blue will surround this community treasure, which is once again standing tall.Merry, Silly ChristmasMy best Christmas was the year we had Ken and Barbie at the top of our tree. We had an angel first, for Christmas Day, but then we had Ken and Barbie. Let me explain. When my daughter was four, I hired a ballet dancer to babysit for a few afternoons a week. Randy was tall and confident, with that dancer’s chest-first carriage, and, though he was only 27, a sure, cheerful bossiness. For four years, he and Halley roamed the city on adventures: to climb the Alice in Wonderland statuein Central Park, to smile at the waddling,pint-sized penguins at the zoo. They hadtheir own world, their own passions: adevotion to ice cream, to Elmo, to Pee-weeHerman.He orchestrated Halley’s birthday partiesto a fare-thee-well: One year he declared aPeter Pan theme, made Halley a TinkerBell outfit with little jingle bells at the hem, and talked my father into making a scary appearance in a big-brimmed pirate hat and a fake hook for a hand. Randy took charge of my grown-up parties, too, dictating what I wore, foraging in thrift shops to find the right rhinestone necklace to go with the dress he’d made me buy.When Halley was eight, Randy left New York to take over a sleepy ballet company in a small city in Colorado. He taught, he choreographed, he coaxed secretaries and computer salesmen intopliéing across the stage.Halley missed him terribly, we all did, but he called her and sent her party dresses, and he came to see us at Christmas when he could. The year Halley was ten, we had a new baby. That same year, Randy was diagnosed with AIDS. He told me over the phone, without an ounce of self-pity, that he had so few T cells left that he’d named them Huey, Dewey, and Louie.It seemed insane for him to travel, insane for him to risk one of us sneezing on him and giving him pneumonia, but he had decided, and that was it. He was as cheerful and bossy as ever. Terribly thin, his cheeks hollow but eyes bright, he took Halley all over the city once again, with baby Julie strapped to his chest in a cloth carrier.“We’ve got to do something about this tree,” he said one day. The tree, with its red ribbon bows, looked fine to me; I was even a little vain about the way every branch shone with ornaments.A few days later, on New Year’s Eve morning, he sum moned our little family. He was wearing the old pirate’s hat, fished out of a costume box and, for hair, curly colored streamers that stuck out of the hat and tumbled down to his shoulders.As we watched — me irritable at first, wondering how much you were supposed to yield to a dying houseguest, even if you loved him like a brother — he stripped the tree. Then he brought out more curly streamers, heaps of them, and tooters and little party-favor plastic champagne bottles. “Now we’ll turn it into a New Year’s tree,” he declared.A New Year’s tree! Of course! We threw the streamers all over the tree, we covered it with the tooters and the tiny champagne bottles. “And now, for the pièce de résistance,” Randy said. Stretching his tall self way up to the top of the tree, he removed its gold papier-mâché angel. Solemnly, carefully, he placed on top Halley’s tuxedoed Ken and her best Barbie, the one in a sparkly ball gown.“Ta da!” he said, and beamed. It was a wonderful tree, happy and goofy and perfect.Randy lived for another year and a half. None of us will ever get over his death, not really. But every Christmastime, I raise a glass to Randy — to his tree, to his bossiness, to the Christmas he taught us that courage is a man in a pirate hat with silly streamers for hair.Sharing the SweetnessOn the 25th of December, my mother expects her children to be present and accounted for, exchanging gifts and eating turkey. When she pulls on that holiday sweater, everybody better get festive. Of course, I would be the first Jones sibling to go rogue. As the middle, artist child, I was going to strike out and do my own thing, make some new traditions. From a biography of Flannery O’Connor, I drew inspiration —I would spend the holiday at an artistcolony!No one took the news very well. From theway my mother carried on, you wouldthink that I was divorcing the family. Still,I held my ground and made plans for mywinter adventure in New Hampshire. TheMacDowell Colony was everything Icould have wished for. About 25 to 30 artists were in attendance, and it was as, well, artsy as I had imagined. It felt like my life had become a quirky independent film.By Christmas Eve, I had been at the colony more than a week. The novelty of snowy New England was wearing off, but I would never admit it. Everyone around me was having too much fun. Sledding and bourbon! Deep conversations by the fireplace! And that guy with the piercings. So cute! What was wrong with me? This was the holiday I’d always dreamed of. No plasticreindeer grazing on the front lawn. No football games on TV. Not a Christmas sweater anywhere in sight. People here didn’t even say “Christmas,” they said “holiday.” Utter sophistication. Then why was I so sad?Finally, I called home on the pay phone in the common room. My dad answered, but I could barely hear him for all the good-time noise in the background. He turned down the volume on the Stevie Wonder holiday album and told me that my mother was out shopping with my brothers. Now it was my turn to sulk. They were having a fine Christmas without me.Despite a massive blizzard, a large package showed up near my door at the artist colony on Christmas morning. Tayari Jones was written in my mother’s beautiful handwriting. I pounced on that parcel like I was five years old. Inside was a gorgeous red-velvet cake, my favorite, swaddled in about 50 yards of bubble wrap. Merry Christmas, read the simple card inside. We love you very much.As I sliced the cake, everyone gathered around — the young and the old, the cynical and the earnest. Mother had sent a genuine homemade gift, not trendy or ironic. It was a minor Christmas miracle that one cake managed to feed so many. We ate it from paper towels with our bare hands, satisfying a hunger we didn’t know we had.Some Assembly RequiredMy five-year-old daughter knew exactly what she wanted for Christmas of 1977, and told me so. Yes, she still would like the pink-and-green plastic umbrella with a clear top she’d been talking about. Great to observe patterns of rain spatters. Books, long flannel nightgown, fuzzy slippers —fine. But really, there was only one thing that mattered: a Barbie Townhouse, with all the accessories.This was a surprise. Rebecca was not aBarbie girl, preferred stuffed animals todolls, and wasn’t drawn to play in astructured environment. Always a make-up-the-rules, design-your-own-world,do-it-my-way kid. Maybe, I thought, thepoint wasn’t Barbie but house, adomicile she could claim for herself,since we’d already moved five times during her brief life.Next day, I stopped at the mall. The huge Barbie Townhouse box was festooned with exclamations: “3 Floors of High-Styled Fun! Elevator Ca n Stop on All Floors!” Some Assembly Required.Uh-oh. My track record for assembling things was miserable. Brooklyn-born, I was raised in apartment buildings in a family that didn’t build things. A few years earlier, I’d spent one week assembling a six-foot-tall jungle gym from a kit containing so many parts, I spent the first four hours sorting and weeping and the last two hours trying to figure out why there were so many leftover pieces. The day after I finished building it, as if to remind me of my limitations, a tornado touched down close enough to scatter the jungle gym across an acre of field.I assembled the Barbie Townhouse on Christmas Eve. Making it level, keeping the columns from looking like they’d melted and been refrozen, and getting that eleva tor to work were almost more than I could manage. And building it in curse-free silence so my daughter would continue sleeping — if, in fact, she was sleeping — added a layer of challenge. By dawn I was done.Shortly thereafter, my daughter walked into the living room, stuffed bear tucked under her arm, feigning shock and looking as tired as I did. Her surprise may have been sham, but her delight was utterly genuine and moves me to this day, 34 years later. Rebecca had spurred me to do something I didn’t th ink I could do. It was for her, and — like so much of the privilege of being her father —it brought me further outside myself and let me overcome doubts about my capacities.Now that I think about it, there probably was real surprise in her first glimpse of her Barbie Townhouse. Not, perhaps, at the gift itself but that it had been built and remained standing in the morning light. Or maybe it was simpler than that: Maybe she was surprised because she’d planned on building the thing herself.All I’m Asking ForI must have been about nine years old, too dignified to sit on Santa’s lap at the Mason’s department store in Anniston, Alabama, but still young enough to ask — please, please, please —for a G.I. Joe. “You’re too old to play withdolls,” my brother Sam hissed at me. Samnever was a child. My kin liked to say theday he was born, he dusted himself off inthe delivery room and walked home.“G.I. Joe ain’t no doll,” I hissed back, myface red.“Is,” Sam said.。