APA 范文格式以及文献格式

Sample APA Research Paper

Sample Title Page

Running on Empty 1

Running on Empty:

The Effects of Food Deprivation on Concentration and Perseverance Thomas Delancy and Adam Solberg

Dordt College

Place manuscript page headers

one-half inch from the top. Put five spaces between the page header and the page

number.

Full title, authors, and school name are centered on the page,

typed in uppercase and

lowercase.

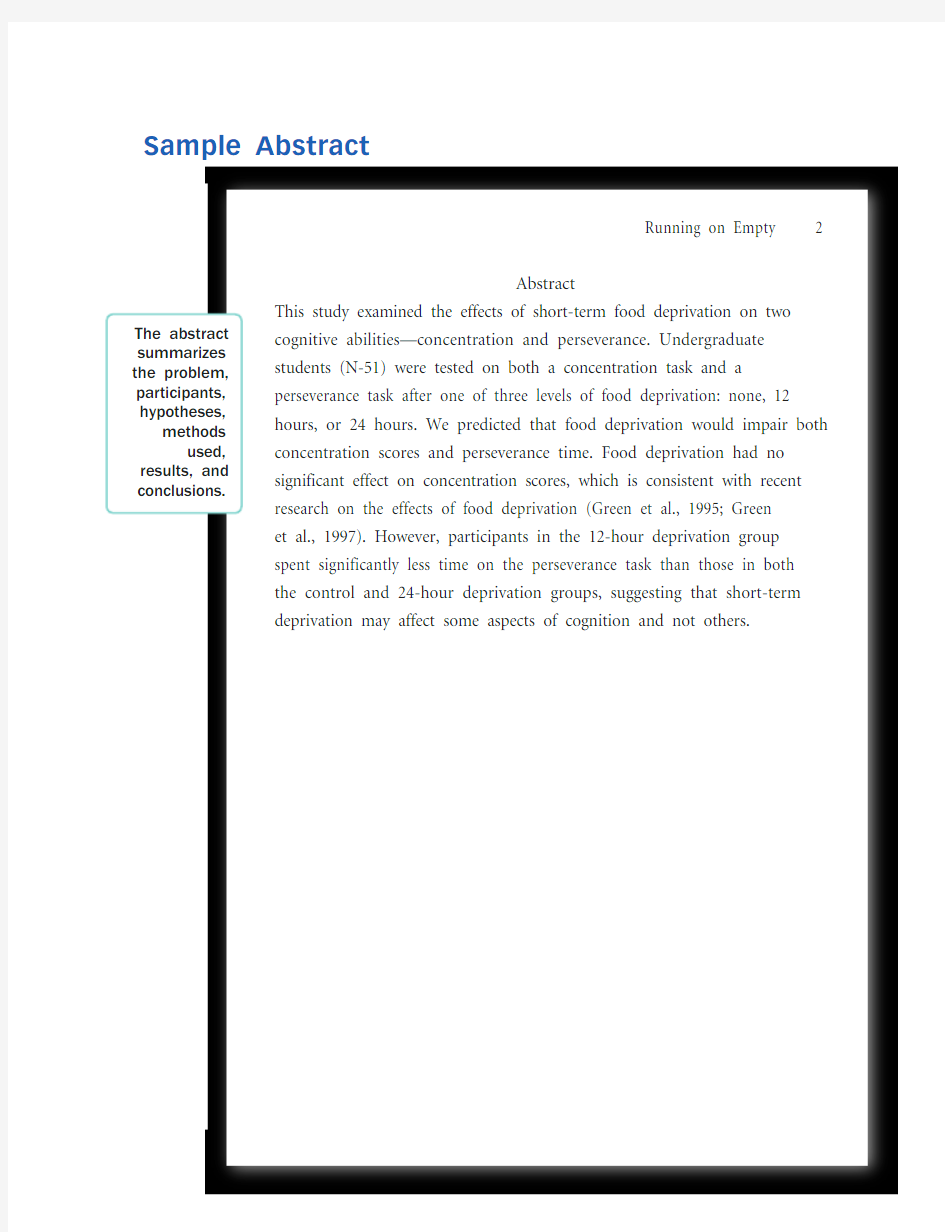

The abstract summarizes the problem, participants, hypotheses,

methods

used, results, and conclusions.

Running on Empty 2

Abstract

This study examined the effects of short-term food deprivation on two cognitive abilities—concentration and perseverance. Undergraduate students (N-51) were tested on both a concentration task and a perseverance task after one of three levels of food deprivation: none, 12 hours, or 24 hours. We predicted that food deprivation would impair both concentration scores and perseverance time. Food deprivation had no significant effect on concentration scores, which is consistent with recent research on the effects of food deprivation (Green et al., 1995; Green

et al., 1997). However, participants in the 12-hour deprivation group spent significantly less time on the perseverance task than those in both the control and 24-hour deprivation groups, suggesting that short-term deprivation may affect some aspects of cognition and not others.

An APA Research Paper Model

Thomas Delancy and Adam Solberg wrote the following research paper for a psychology class. As you review their paper, read the side notes and examine the following:

●The use and documentation of their numerous sources.

●The background they provide before getting into their own study results.

●The scientific language used when reporting their results.

The introduction

states the

topic and

the main questions to be explored.

The researchers

supply background information by discussing past research on the topic.

Extensive referencing establishes

support

for the discussion.

Running on Empty 3

Running on Empty: The Effects of Food Deprivation

on Concentration and Perseverance

Many things interrupt people’s ability to focus on a task: distractions, headaches, noisy environments, and even psychological disorders. To some extent, people can control the environmental factors that make it difficult to focus. However, what about internal factors, such as an empty stomach? Can people increase their ability to focus simply by eating regularly?

One theory that prompted research on how food intake affects the average person was the glucostatic theory. Several researchers in the

1940s and 1950s suggested that the brain regulates food intake in order

to maintain a blood-glucose set point. The idea was that people become hungry when their blood-glucose levels drop significantly below their set point and that they become satisfied after eating, when their blood-glucose levels return to that set point. This theory seemed logical because glucose

is the brain’s primary fuel (Pinel, 2000). The earliest investigation of the general effects of food deprivation found that long-term food deprivation (36 hours and longer) was associated with sluggishness, depression, irritability, reduced heart rate, and inability to concentrate (Keys, Brozek, Henschel, Mickelsen, & Taylor, 1950). Another study found that fasting

for several days produced muscular weakness, irritability, and apathy or depression (Kollar, Slater, Palmer, Docter, & Mandell, 1964). Since that time, research has focused mainly on how nutrition affects cognition. However, as Green, Elliman, and Rogers (1995) point out, the effects of food deprivation on cognition have received comparatively less attention in recent years.

Center the title one inch from the top. Double-space throughout.

Running on Empty 4

The relatively sparse research on food deprivation has left room for

further research. First, much of the research has focused either on chronic starvation at one end of the continuum or on missing a single meal at the other end (Green et al., 1995). Second, some of the findings have been contradictory. One study found that skipping breakfast impairs certain aspects of cognition, such as problem-solving abilities (Pollitt, Lewis, Garza, & Shulman, 1983). However, other research by M. W. Green, N. A. Elliman, and P. J. Rogers (1995, 1997) has found that food deprivation ranging from missing a single meal to 24 hours without eating does not significantly impair cognition. Third, not all groups of people have been sufficiently studied. Studies have been done on 9–11 year-olds (Pollitt et

al., 1983), obese subjects (Crumpton, Wine, & Drenick, 1966), college-age men and women (Green et al., 1995, 1996, 1997), and middle-age males (Kollar et al., 1964). Fourth, not all cognitive aspects have been studied. In 1995 Green, Elliman, and Rogers studied sustained attention, simple reaction time, and immediate memory; in 1996 they studied attentional bias; and in 1997 they studied simple reaction time, two-finger tapping, recognition memory, and free recall. In 1983, another study focused on reaction time and accuracy, intelligence quotient, and problem solving (Pollitt et al.).

According to some researchers, most of the results so far indicate that cognitive function is not affected significantly by short-term fasting (Green et al., 1995, p. 246). However, this conclusion seems premature due to the relative lack of research on cognitive functions such as concentration and

perseverance. To date, no study has tested perseverance, despite its

importance in cognitive functioning. In fact, perseverance may be a better

indicator than achievement tests in assessing growth in learning and thinking abilities, as perseverance helps in solving complex problems (Costa, 1984). Another study also recognized that perseverance, better

learning techniques, and effort are cognitions worth studying (D’Agostino, 1996). Testing as many aspects of cognition as possible is key because the nature of the task is important when interpreting the link between food deprivation and cognitive performance (Smith & Kendrick, 1992).

Clear transitions guide readers through the researchers’ reasoning.

The

researchers explain how their study will add to past research on the topic.

The

researchers support their decision to focus on concentration

and

perseverance.

Running on Empty 5

Therefore, the current study helps us understand how short-term food deprivation affects concentration on and perseverance with a difficult task. Specifically, participants deprived of food for 24 hours were expected to perform worse on a concentration test and a perseverance task than those deprived for 12 hours, who in turn were predicted to perform worse than those who were not deprived of food.

Method

Participants

Participants included 51 undergraduate-student volunteers (32 females, 19 males), some of whom received a small amount of extra credit in a college course. The mean college grade point average (GPA) was 3.19. Potential participants were excluded if they were dieting, menstruating, or taking special medication. Those who were struggling with or had

struggled with an eating disorder were excluded, as were potential participants addicted to nicotine or caffeine. Materials

Concentration speed and accuracy were measured using an online numbers-matching test (https://www.360docs.net/doc/8e296813.html,/tests/iq/concentration.html) that consisted of 26 lines of 25 numbers each. In 6 minutes, participants were required to find pairs of numbers in each line that added up to 10. Scores were calculated as the percentage of correctly identified pairs out of

a possible 120. Perseverance was measured with a puzzle that contained five octagons—each of which included a stencil of a specific object (such as an animal or a flower). The octagons were to be placed on top of each other in a specific way to make the silhouette of a rabbit. However, three of the shapes were slightly altered so that the task was impossible. Perseverance scores were calculated as the number of minutes that a participant spent on the puzzle task before giving up. Procedure

At an initial meeting, participants gave informed consent. Each consent form contained an assigned identification number and requested the participant’s GPA. Students were then informed that they would be notified by e-mail and telephone about their assignment to one of the

The

researchers state their

initial hypotheses.

Headings and subheadings show the paper’s organization.

The

experiment’s method is described, using the terms and acronyms of the discipline.

Passive voice

is used to emphasize

the

experiment,

not the researchers; otherwise, active voice

is used.

Running on Empty 6

three experimental groups. Next, students were given an instruction sheet. These written instructions, which we also read aloud, explained the experimental conditions, clarified guidelines for the food deprivation period, and specified the time and location of testing.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of these conditions using a matched-triplets design based on the GPAs collected at the initial meeting. This design was used to control individual differences in cognitive ability. Two days after the initial meeting, participants were informed of their group assignment and its condition and reminded that, if they were in a food-deprived group, they should not eat anything after 10 a.m. the next day. Participants from the control group were tested at 7:30 p.m. in a designated computer lab on the day the deprivation started. Those in the 12-hour group were tested at 10 p.m. on that same day. Those in the 24-hour group were tested at 10:40 a.m. on the following day.

At their assigned time, participants arrived at a computer lab for testing. Each participant was given written testing instructions, which were also read aloud. The online concentration test had already

been loaded on the computers for participants before they arrived for testing, so shortly after they arrived they proceeded to complete the test. Immediately after all participants had completed the test and their scores were recorded, participants were each given the silhouette puzzle and instructed how to proceed. In addition, they were told that (1) they would have an unlimited amount of time to complete the task, and (2) they were not to tell any other participant whether they had completed the puzzle or simply given up. This procedure was followed to prevent the group influence of some participants seeing others give up. Any participant still working on the puzzle after 40 minutes was stopped to keep the time of the study manageable. Immediately after each participant stopped working on the puzzle, he/she gave demographic information and completed a few manipulation-check items. We then debriefed and dismissed each participant outside of the lab.

Attention is

shown to

the control features.

The

experiment is laid out step

by step, with time transitions like “then” and “next.”

Running on Empty 7

Results

Perseverance data from one control-group participant were

eliminated because she had to leave the session early. Concentration data from another control-group participant were dropped because he did not complete the test correctly. Three manipulation-check questions indicated that each participant correctly perceived his or her deprivation condition and had followed the rules for it. The average concentration score was 77.78 (SD = 14.21), which was very good considering that anything over 50 percent is labeled “good” or “above average.” The average time spent on the puzzle was 24.00 minutes (SD = 10.16), with a maximum of 40 minutes allowed.

We predicted that participants in the 24-hour deprivation group would perform worse on the concentration test and the perseverance task than those in the 12-hour group, who in turn would perform worse than those in the control group. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed no significant effect of deprivation condition on concentration, F(2,46) = 1.06, p = .36 (see Figure 1). Another one-way ANOVA indicated

Figure 1.

No deprivation 12-hour deprivation

24-hour deprivation

Deprivation Condition

100

90

80

70

60

50

M e a n s c o r e o n c o n c e n t r a t i o n t e s t

The writers summarize their findings,

including problems encountered.

“See Figure 1” sends readers to a figure (graph, photograph,

chart, or drawing) contained in the paper.All figures

and

illustrations (other than tables) are numbered in the order that they are first mentioned in

the text.

Running on Empty 8

a significant effect of deprivation condition on perseverance time, F(2,47) = 7.41, p < .05. Post-hoc Tukey tests indicated that the 12-hour deprivation group (M = 17.79, SD = 7.84) spent significantly less time on the perseverance task than either the control group (M = 26.80, SD = 6.20) or the 24-hour group (M = 28.75, SD = 12.11), with no significant difference between the latter two groups (see Figure 2). No significant effect was found for gender either generally or with specific deprivation conditions, Fs < 1.00. Unexpectedly, food deprivation had no significant effect on concentration scores. Overall, we found support for our hypothesis that 12 hours of food deprivation would significantly impair perseverance when compared to no deprivation. Unexpectedly, 24 hours of food deprivation did not significantly affect perseverance relative to the control group. Also unexpectedly, food deprivation did not significantly affect concentration scores. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to test how different levels of food deprivation affect concentration on and perseverance with difficult tasks.

302826242220181614121086420

M e a n s c o r e o n p e r s e v e r a n c e t e s t

Figure 2.

No deprivation 12-hour deprivation 24-hour deprivation

Deprivation Condition

The

researchers restate their hypotheses

and the results, and go on to interpret those results.

Running on Empty 9

We predicted that the longer people had been deprived of food, the lower they would score on the concentration task, and the less time they would spend on the perseverance task. In this study, those deprived of food did give up more quickly on the puzzle, but only in the 12-hour group. Thus, the hypothesis was partially supported for the perseverance task. However, concentration was found to be unaffected by food deprivation, and thus the hypothesis was not supported for that task.

The findings of this study are consistent with those of Green et al.

(1995), where short-term food deprivation did not affect some aspects of cognition, including attentional focus. Taken together, these findings suggest that concentration is not significantly impaired by short-term food deprivation. The findings on perseverance, however, are not as easily explained. We surmise that the participants in the 12-hour group gave up more quickly on the perseverance task because of their hunger produced by the food deprivation. But why, then, did those in the 24-hour group fail to yield the same effect? We postulate that this result can be explained by the concept of “learned industriousness,” wherein participants who perform one difficult task do better on a subsequent task than the participants who never took the initial task (Eisenberger & Leonard, 1980; Hickman, Stromme, & Lippman, 1998). Because participants had successfully completed 24 hours of fasting already, their tendency to persevere had already been increased, if only temporarily. Another possible explanation is that the motivational state of a participant may be a significant determinant of behavior under testing (Saugstad, 1967). This idea may also explain the short perseverance times in the 12-hour group: because these participants took the tests at 10 p.m., a prime time of the night for conducting business and socializing on a college campus, they may have been less motivated to take the time to work on the puzzle.

Research on food deprivation and cognition could continue in several directions. First, other aspects of cognition may be affected by short-term food deprivation, such as reading comprehension or motivation. With respect to this latter topic, some students in this study reported decreased motivation to complete the tasks because of a desire to eat immediately

The writers speculate on possible explanations

for the unexpected

results.

Running on Empty 10

after the testing. In addition, the time of day when the respective groups took the tests may have influenced the results: those in the 24-hour group took the tests in the morning and may have been fresher and more relaxed than those in the 12-hour group, who took the tests at night. Perhaps, then, the motivation level of food-deprived participants could be effectively tested. Second, longer-term food deprivation periods, such as those experienced by people fasting for religious reasons, could be explored. It is possible that cognitive function fluctuates over the duration of deprivation. Studies could ask how long a person can remain focused despite a lack of nutrition. Third, and perhaps most fascinating, studies could explore how food deprivation affects learned industriousness. As stated above, one possible explanation for the better perseverance times in the 24-hour group could be that they spontaneously improved their perseverance faculties by simply forcing themselves not to eat for 24 hours. Therefore, research could study how food deprivation affects the acquisition of perseverance.

In conclusion, the results of this study provide some fascinating

insights into the cognitive and physiological effects of skipping meals. Contrary to what we predicted, a person may indeed be very capable of concentrating after not eating for many hours. On the other hand, if one is taking a long test or working long hours at a tedious task that requires perseverance, one may be hindered by not eating for a short time, as shown by the 12-hour group’s performance on the perseverance task. Many people—students, working mothers, and those interested in fasting, to mention a few—have to deal with short-term food deprivation, intentional or unintentional. This research and other research to follow will contribute to knowledge of the disadvantages—and possible advantages—of skipping meals. The mixed results of this study suggest that we have much more to learn about short-term food deprivation.

The

conclusion summarizes

the

outcomes, stresses the experiment’s value, and anticipates

further advances on the topic.

Running on Empty 11

References

Costa, A. L. (1984). Thinking: How do we know students are getting better

at it? Roeper Review, 6, 197–199.

Crumpton, E., Wine, D. B., & Drenick, E. J. (1966). Starvation: Stress

or satisfaction? Journal of the American Medical Association, 196, 394–396.

D’Agostino, C. A. F. (1996). Testing a social-cognitive model of

achievement motivation.-Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities & Social Sciences, 57, 1985.

Eisenberger, R., & Leonard, J. M. (1980). Effects of conceptual task

difficulty on generalized persistence. American Journal of Psychology, 93, 285–298.

Green, M. W., Elliman, N. A., & Rogers, P. J. (1995). Lack of effect of

short-term fasting on cognitive function. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 29, 245–253.

Green, M. W., Elliman, N. A., & Rogers, P. J. (1996). Hunger, caloric

preloading, and the selective processing of food and body shape words. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 35, 143–151.

Green, M. W., Elliman, N. A., & Rogers, P. J. (1997). The study effects of

food deprivation and incentive motivation on blood glucose levels and cognitive function. Psychopharmacology, 134, 88–94. Hickman, K. L., Stromme, C., & Lippman, L. G. (1998). Learned

industriousness: Replication in principle. Journal of General Psychology, 125, 213–217.

Keys, A., Brozek, J., Henschel, A., Mickelsen, O., & Taylor, H. L. (1950).

The biology of human starvation (Vol. 2). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kollar, E. J., Slater, G. R., Palmer, J. O., Docter, R. F., & Mandell, A. J.

(1964). Measurement of stress in fasting man. Archives of General Psychology, 11, 113–125.

Pinel, J. P. (2000). Biopsychology (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

All works referred to in the paper appear on the reference page, listed alphabetically

by author

(or title).

Each entry follows APA guidelines for listing authors, dates, titles, and publishing information.

Capitalization, punctuation, and hanging indentation are consistent

with APA format.

Running on Empty 12 Pollitt, E., Lewis, N. L., Garza, C., & Shulman, R. J. (1982–1983). Fasting and cognitive function. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 17, 169–174. Saugstad, P. (1967). Effect of food deprivation on perception-cognition:

A comment [Comment on the article by David L. Wolitzky].

Psychological Bulletin, 68, 345–346.

Smith, A. P., & Kendrick, A. M. (1992). Meals and performance. In A. P.

Smith & D. M. Jones (Eds.), Handbook of human performance: Vol. 2, Health and performance (pp. 1–23). San Diego: Academic Press. Smith, A. P., Kendrick, A. M., & Maben, A. L. (1992). Effects of breakfast and caffeine on performance and mood in the late morning and

after lunch. Neuropsychobiology, 26, 198–204.

APA格式要求reference

《心理科学》参考文献(作者-出版年制)详细要求 本刊来稿自2010年4月1日起废止参考文献著录“顺序编码制”,采用APA“作者-出版年制”。详细规定请查阅美国心理协会写作手册(2003)。 总体要求 1 正文中引用的文献与文后的文献列表必须完全一致。 正文中所引用的文献可以在正文后的文献列表中找到;文献列表中所列文献只能包括正文中所引用的文献。 2 文献列表中的文献著录必须正确而完整。 因为列出著录参考文献的目的之一就是使读者能够检索并查找有关的资料来源,因此参考文献著录必须正确且完整。 3 文献列表的顺序 先列中文文献,后列英文文献。 文献按作者姓氏字母顺序排列。请记住,后面没有附随的名字排在有附随的名字之前。 例如,“Brown,J. R.”排在“Browning,A. R.”之前。 当作者相同,且只有一位作者时,按出版年排列,先出版的排在前面,例如:Hewlett, L. S. (2008). Hewlett, L. S. (2009). 如果作者和出版年都相同,则按文题的首字母顺序排列,并出版年后加a、b、c… Hewlett, L. S. (2009a). Emotional Self-regulation…… Hewlett, L. S. (2009b). Developmental…… Hewlett, L. S. (2009c). Implicit Attitude Towards…… 如果只有第一位作者相同,则只有一位作者的排在有多位作者的条目前面。例如:Alleyne, R. L.(2001). Alleyne, R. L., & Evans, A. J. (1999). 如果第一位作者相同,第二位或第三位作者不同,则依第二位作者姓氏字母顺序排列。 假如第一位、第二位作者都相同,则依第三位作者姓氏字母顺序排列,依次类推。 4 缩写

APA参考文献格式

《心理学报》参考文献著录格式(著者-出版年制)详细要求 本刊参照文献要求基本参照了Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (2010) 第6版的相关规定,中文文献有细节上的特殊要求。 总体要求 1 正文中引用的文献与文后的文献列表要完全一致。 ?文中引用的文献可以在正文后的文献列表中找到;文献列表的文献必须在正文中引用。 2 文献列表中的文献著录必须准确和完备。 3 文献列表的顺序 ?文献列表按著者姓氏字母(或汉语拼音)顺序排列;姓相同,按名的字母顺序排列;著 者姓和名相同,按出版年排列。 ?相同著者,相同出版年的不同文献,需在出版年后面加a、b、c、d……来区分,按文 题的字母顺序排列。如: Wang, M. Y. (2008a). Emotional…… Wang, M. Y. (2008b). Monitor…… Wang, M. Y. (2008c). Weakness…… 4 缩写 chap. chapter 章 ed. edition 版 Rev. ed. revised edition 修订版 2nd ed. second edition 第2版 Ed. (Eds.) Editor (Editors) 编 Trans. Translator(s) 译 n.d. No date 无日期 p. (pp.) page (pages) 页 V ol. Volume (as in V ol. 4) 卷 vols. volumes (as in 4 vols.) 卷 No. Number 第 Pt. Part 部分 Tech. Rep. Technical Report 技术报告 Suppl. Supplement 增刊 5 元分析报告中的文献引用 ?元分析中用到的研究报告直接放在文献列表中,但要在文献前面加星号*。并在文献列 表的开头就注明*表示元分析用到的的文献。 6 中文文献应给出相应的英文。先给出英文,然后把中文放在下面的方括号中。

APA格式参考文献示例

APA格式参考文献示例 期刊文章 1. 一位作者写的文章 Hu, L. X.[胡莲香].(2014).走向大数据知识服务:大数据时代图书馆服务模式创新.农业图书情报学刊(2): 173-177. Olsher, D. (2014). Sema ntically-based priors and nuan ced kno wledge core for Big Data, Social Al, and Ian guage un dersta ndin gNeural Networks, 58 131-147. 2. 两位作者写的文章 Li, J. Z., & Liu, X. M.[李建中,刘显敏].(2013).大数据的一个重要方面:数据可用性. 计算机研究与发展(6): 1147-1162. Men del, J. M., & Korja ni, M. M. (2014). On establishi ng non li near comb in atio ns of variables from small to big data for use in later process ingln formati on Scie nces, 280, 98-110. 3. 三位及以上的作者写的文章 Weichselbraun, A. et al. (2014). Enriching semantic knowledge bases for opinion mi ning in big data applicati ons. Kno wledge-Based Systems, 6978-85. Zhang, P. et al.张鹏等].(2013).云计算环境下适于工作流的数据布局方法.计算机研究与发展(3): 636-647. 专著 1. 一位作者写的书籍 Rossi, P. H. (1989).Dow n and out in America: The origi ns of homeless nessChicago: Uni versity of Chicago Press. Wang, B. B.[王彬彬].(2002).文坛三户:金庸王朔余秋雨一一当代三大文学论争辨析.郑州:大象出版社. 2. 两位作者写的书籍 Plant, R., & Hoover, K. (2014). Conservative capitalism in Britain and the United States: A critical appraisal. London: Routledge. Yin, D., & Shang, H.[隐地,尚海].(2001).到绿光咖啡屋听巴赫读余秋雨.上海: 上海世

参考文献APA格式

APA格式主要用于心理学、教育学、社会科学领域的论文写作。其规范格式主要包括文内文献引用(Reference Citations in Text)和文后参考文献列举(Reference List)两大部分。APA格式强调出版物的年代(Time of the Publication Year)而不大注重原文作者的姓名。引文时常将出版年代置于作者缩写的名( the Initial of Author's First Name)之前。中国的外语类期刊(语言学刊物为主)及自然科学类的学术刊物喜欢使用APA格式。 APA格式APA格式是一个为广泛接受的研究论文撰写格式,特别针对社会科学领域的研究,规范学术文献的引用和参考文献的撰写方法,以及表格、图表、注脚和附录的编排方式。APA格式因采用哈佛大学文章引用的格式而广为人知,其“作者和日期”的引用方式和“括号内引用法”相当著名。 正式来说,APA格式指的就是美国心理学会(A merican P sychological A ssociation)出版的《美国心理协会刊物准则》,目前已出版至第五版(ISBN 1-55798-791-2),总页数超过400页,而此协会是目前在美国具有权威性的心理学学者组织。APA格式起源于1929年,当时只有7页,被刊登在《心理学期刊(Psychological Bulletin)》。 另一种相当有名的论文格式为MLA格式(The MLA Style Manual),主要被应用在人文学科,如文学、比较文学、文学批评和文化研究等。 虽然有些作者对于APA格式其中的一些规范感到不妥,但APA格式仍备受推崇。期刊采用同一种格式能够让读者有效率的浏览和搜集文献资料,写作时感到不确定的学者们发现这样的格式手册非常有帮助。譬如,手册中的“非歧视语言”章节明文禁止作者针对女性和弱势团体使用歧视的文字,不过使用APA格式的学术期刊有时也会为了让文章更有条理而允许作者忽略此规定。 标题是用来组织文章,使得其有层次架构。APA格式规定了文章内“标题”的特定格式(1到5级),此详细内容可参阅《美国心理协会刊物手册》第五版的第113页,级数和格式如下: 第1级:置中大小写标题(Centered Uppercase and Lowercase Heading)第2级:置中、斜体、大小写标题(Centered, Italicized, Uppercase and Lowercase Heading) 第3级:靠左对齐、斜体、大小写标题(Flush Left, Italicized, Uppercase and Lowercase Side Heading) 第4级:缩排、斜体、小写标题,最后加句号(Indented, italicized, lowercase paragraph heading ending with a period) 第5级:置中大写标题(CENTERED UPPERCASE HEADING) 根据APA格式,若文章标题有: 1个级数:使用第1级标题

APA参考文献格式

《心理科学进展》参考文献著录格式(著者-出版年制)基本要求 (投稿指南) 本刊来稿从即日起废止顺序编码制的参考文献著录格式,采用APA的著者-出版年制。进一步的说明请到本刊网站“下载中心”下载。详细规定请查阅Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association,2003年第5版。 1 正文中的文献引用标志 正文中的文献引用标志是著者(外国人只写姓,中国人的中文需写全姓名)和出版年,可以作为句子的一个成分,也可放在引用句尾的括号中,可以根据行文的需要灵活选用一种方式。 2 正文后的文献列表 ?文献列表按著者姓氏字母顺序排列;著者相同,按出版年排列;著者和出版年都相同, 按文题的首字母顺序排列,出版年后加a、b、c… ?先列中文文献,后列英文文献。 ?中文文献中的著录符号需用英文(半角)符号。 ?英文逗号、点号、冒号后要留一空格。 ?著者姓名、出版年、文题、书名、出版信息等各个文献成分末尾用点号结束。 ?排版时需悬挂缩进。 常见的文献类型要求如下: 2.1 期刊论文 著者姓, 名. (出版年份). 文题. 刊名,卷号,起止页码. 示例: Tversky, B. (1981). Distortions in memory for maps. Cognitive Psychology,13, 407–433. Zhuang, J., & Zhou, X. L. (2001). Word length effect in speech production of Chinese. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 33, 214–218. 庄捷, 周晓林. (2001). 言语产生中的词长效应. 心理学报, 33, 214–218. ?姓需全拼,名只写首字母;姓氏后面有逗号,名的缩写字母后面有缩写点。 ?6个作者以后才能用“et al.”或“等”。 ?著者之间都用逗号隔开。两个或两个以上著者之间只有最后两个著者之间用“&”。?文题只有第一个单词的首字母大写,其余为小写(特殊要求大写的除外)。 ?刊名和卷号后用为逗号,字体为斜体。不需要写期刊的期号,除非期刊的每一期都是从 第1页开始编页码,才要写期号(期号和两边的括号为正体);如果全年各期页码是连续编号,则不需要写出期号,只需要写出卷号即可。 ?页码范围符号不是“-”,而是“–”。

APA参考文献格式

《心理学报》参考文献着录格式(着者-出版年制)详细要求 本刊参照文献要求基本参照了Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (2010) 第6版的相关规定,中文文献有细节上的特殊要求。 总体要求 1 正文中引用的文献与文后的文献列表要完全一致。 ?文中引用的文献可以在正文后的文献列表中找到;文献列表的文献必须在正文中引用。 2 文献列表中的文献着录必须准确和完备。 3 文献列表的顺序 ?文献列表按着者姓氏字母(或汉语拼音)顺序排列;姓相同,按名的字母顺序排列;着者姓和名相 同,按出版年排列。 ?相同着者,相同出版年的不同文献,需在出版年后面加a、b、c、d……来区分,按文题的字母顺序 排列。如: Wang, M. Y. (2008a). Emotional…… Wang, M. Y. (2008b). Monitor…… Wang, M. Y. (2008c). Weakness…… 4 缩写 chap. chapter 章 ed. edition 版 Rev. ed. revised edition 修订版 2nd ed. second edition 第2版 Ed. (Eds.) Editor (Editors) 编 Trans. Translator(s) 译 n.d. No date 无日期 p. (pp.) page (pages) 页 Vol. Volume (as in Vol. 4) 卷 vols. volumes (as in 4 vols.) 卷 No. Number 第 Pt. Part 部分 Tech. Rep. Technical Report 技术报告 Suppl. Supplement 增刊 5 元分析报告中的文献引用 ?元分析中用到的研究报告直接放在文献列表中,但要在文献前面加星号*。并在文献列表的开头就注 明*表示元分析用到的的文献。 6 中文文献应给出相应的英文。先给出英文,然后把中文放在下面的方括号中。 正文中的文献引用标志 在着者-出版年制中,文献引用的标志就是“着者”和“出版年”,主要有两种形式: (1)正文中的文献引用标志可以作为句子的一个成分,如:Dell(1986)基于语误分析的结果提出了音韵编码模型,……。汉语词汇研究有庄捷和周晓林(2001)的研究。 (2)也可放在引用句尾的括号中,如:在语言学上,音节是语音结构的基本单位,也是人们自然感到的最小语音片段。按照汉语的传统分析方法,汉语音节可以分析成声母、韵母和声调(胡裕树,1995;

APA参考文献格式-最新版

参考文献著录格式示例 (APA格式,选题报告和论文以此为准) 参考文献按先英文后中文排列,全部按首写字母排序 A.1专著 例: 龙文佩,(1988),《外国当代剧作选》。北京:中国戏剧出版社。 Grice, H. P. (2002). Studies in the way of words. Beijing: Foreign Languages Teaching and Research Press. (出版年份加括号,中文书目用书名号,中文标点;英文专著只大写第一个字母,用斜体;) A.2学位论文 例: 张筑,(2010),学术摘要中的主位研究,硕士学位论文。北京:北京大学。 Cairns, R. B. (2012). Infared spectroscopic studies on solid oxygen, M.A. Thesis. Berkeley: University of California. (中文学位论文标明“硕士/博士学位论文”,英文对应用M.A. Thesis或Ph.D. Dissertation,后加地点和学校,英文论文标题需斜体,第一个字母大写,格式同专著) A.3文集中析出的文献 例: 黄蕴慧,(2003),国际矿物学研究的动向,见程裕淇等编,《世界地质科技发展动向》。北京:地质出版社,38-39 Rivers, S. (2010). Bringing it all together: Applying metaphor analysis to online discussions in a doctorate study. In Cameron, L. & Maslen, R. (eds.). Metaphor analysis: Research practice in

APA参考文献格式 (3)

【参考文献】 文献引用,有两种主要方法,其中之一是作为直接参考的名字,如改为: Razik(1995)的研究...,另一种是直接参照或参数的研究,如结果:教学领导副主席的重要职能(康威,1993年)校长....阿帕对文学的格式引用主要是11种(见该手册,207-214),分述如下: (一)基本格式:在同一段中,已被引用作者,第一次写的日期,第二时代之后,日期可以省略。 1。英国文学:在最近的反应时间的研究,沃克(2000年)所描述 该方法...沃克还发现.... 2。华文文学:秦梦群(中国90)的重点是教育券的重要性上,...;秦梦群 还建议.... (二) 作者为一个人时,格式为: 1. 英文文献:姓氏(出版或发表年代) 或(姓氏,出版或发表年代). 例如:Porter (2001)…或…(Porter, 2001). 认识APA格式3 2. 中文文献:姓名(出版或发表年代) 或(姓名,出版或发表年代). 例如:吴清山(民90)…或…(吴清山,民90). (三) 作者为二人以上时,必须依据以下原则撰写(括弧中注解为中文建议格式): 1. 原则一:作者为两人时,两人的姓氏(名) 全列. 例如:Wassertein and Rosen (1994)…或…(Wassertein & Rosen (1994) 例如:吴清山与林天佑(民90)…或…(吴清山,林天佑,民90) 2. 原则二:作者为三至五人时,第一次所有作者均列出,第二次以后仅写出第一位作者并加et al. (等人). 例如: [第一次出现] Wasserstein, Zappula, Rosen, Gerstman, and Rock (1994) found…或(Wasserstein, Zappula, Rosen, Gerstman, & Rock, 1994)…. [第二次以后] Wasserstein et al. (1994)…或(Wasserstein et al., 1994)…. 例如: [第一次出现] 吴清山,刘春荣与陈明终(民84)指出…或…(吴清山,刘春荣,陈明终,民84). [第二次以后] 吴清山等人(民84)指出…或…(吴清山等人,民84). 3. 原则三:作者为六人以上时,每次仅列第一位作者并加et al. (等人),但在参考文献中要列出所有作者姓名. 4. 原则四:二位以上作者时,文中引用时作者之间用and (与) 连接,在括弧内以及参考文献中用& ( ) 连接. (四) 作者为组织团体或单位时,依下列原则撰写: 1. 易生混淆之单位,每次均用全名. 2. 简单且广为人知的单位,第一次加注其缩写方式,第二次以后可用缩写,但在参考文献中一律要写出全名. 例如: [第一次出现] National Institute of Mental Health[NIMH] (1999) 或 (National Institute of Mental Health[NIMH], 1999). [第二次以后] NIMH (1999)…或(NIMH, 1999)…. 例如: [第一次出现] 行政院教育改革审议委员会[行政院教改会](民

参考文献格式apa6

References/Bibliography APA Based on the “Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association” 6th edition. The “APA style” is an author-date style for citing and referencing information in assignments and publications. This guide is based on the American Psychological Association’s Publication Manual, 6th edition (2010). Note: Before you write your list of references, check with your lecturer or tutor for the bibliographic style preferred by the School. There may be differences in the style recommended by the School. What is referencing? Referencing is a standardised way of acknowledging the sources of information and ideas that you have used in your assignments. This allows the sources to be identified. Why reference? Referencing is important to avoid plagiarism, to verify quotations and to enable readers to identify and follow up works you have referred to. Steps in referencing ?Record the full bibliographic details and relevant page numbers of the source from which information is taken. ?Note the DOI (digital object identifier), if present. When a DOI is used, do not provide the URL or date of retrieval. ?Insert the citation at the appropriate place in the text of your document. ?Include a reference list that includes all in-text citations at the end of your document. In-text citations ?In an author-date style, in-text citations usually require the name of the author(s) and the year of publication. ? A page number is included if you have a direct quote. When you paraphrase a passage, or refer to an idea contained in another work, providing a page number is not required, but is "encouraged", especially if you are referring to a long work and the page numbers might be useful to the reader. How to create a reference list/bibliography ? A reference list includes just the books, articles, and web pages etc that are cited in the text of the document. A bibliography includes all sources consulted for background reading. ? A reference list is arranged alphabetically by author. If an item has no author, it is cited by title, and included in the alphabetical list using the first significant word of the title. ?If you have more than one item with the same author, list the items chronologically, starting with the earliest publication. ?Each reference appears on a new line. ?Each item in the reference list is required to have a hanging indent. ?References should not be numbered. Referencing Software The University of Queensland Library provides access to EndNote and RefWorks software, which assist in creating reference lists. An APA 6th style is provided in the Endnote X4 software.(22/11/2011)

APA简单参考文献格式

APA格式 一.英语原版材料 引用英语著作: Rossi (姓), P. H. (名的首字母缩写)(1989) (出版年). Down and out in America: The origins of homelessness. (著作名)Chicago (出版地): University of Chicago Press. (出版商) 引用编撰的著作: Campbell, J. P., Campbell, R. J., & Associates. (Eds.). (1988). Productivity in organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. 引用翻译的著作: Michotte, A. E. (1963). The perception of causality (T. R. Miles & E. Miles, Trans.). (翻译者的名和姓不需要改变次序)London: Methuen. (Original work published 1946) 引用重版书: Ebbinghaus, H. (1964). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York: Dover. (Original work published 1885; translated 1913) 引用收集在英语著作中的文章: Wilson, S. F. (1990). Community support and integration: New directions for outcome research. In S. Rose (Ed.) (代表“编”), Case management: An overview and assessment (pp. 13-42). White Plains, NY: Longman. 引用英语期刊文章: Roediger, H. L. (1990). Implicit memory: A commentary. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society (文章名), 28 (第几期), 373-380. (文章页码) 引用英语硕博士论文: Thompson, L. (1988). Social perception in negotiation. (论文名)Unpublished doctoral

APA参考文献著录格式

APA参考文献著录格式(著者-出版年制)详细要求 正文中的文献引用标志 正文中的文献引用标志可以作为句子的一个成分,如: Dell(1986)基于语误分析的结果提出了音韵编码模型,…… 汉语词汇研究有庄捷和周晓林(2001)的研究。 也可放在引用句尾的括号中,如: 在语言学上,音节是语音结构的基本单位,也是人们自然感到的最小语音片段。按照汉语的传统分析方法,汉语音节可以分析成声母、韵母和声调(胡裕树,1995;黄伯荣,廖序东,2001)。 音韵编码模型假设音韵表征包含多个层次(Dell,1986)。 可以根据行文的需要灵活选用一种方式。 总体要求 1 正文中引用的文献与文后的文献列表要完全一致。 ?文中引用的文献可以在正文后的文献列表中找到;文献列表的文献必须在正文中引用。 2 文献列表中的文献著录必须准确和完备。 3 文献列表的顺序 ?文献列表按著者姓氏字母顺序排列;姓相同,按名的字母顺序排列;著者姓和名相同, 按出版年排列。 ?相同著者,相同出版年的不同文献,需在出版年后面加a、b、c、d……来区分,按文 题的字母顺序排列。如: Wang, M. Y. (2008a). Emotional…… Wang, M. Y. (2008b). Monitor…… Wang, M. Y. (2008c). Weakness…… 4 缩写 chap. chapter 章 ed. edition 版 Rev. ed. revised edition 修订版 2nd ed. second edition 第2版 Ed. (Eds.) Editor (Editors) 编 Trans. Translator(s) 译 n.d. No date 无日期 p. (pp.) page (pages) 页

2-参考文献格式(APA格式)

References (in APA style papers) In an APA style paper, the citation sources are listed in References on a separate page, which follows the final page of the text. Entries appear alphabetically according to the last name of the author; two or more works by the same author are listed in chronological order by the date of publication. All entries in the References page must correspond to the sources cited in the main text. The writers are supposed to observe the following rules: (1)All lines after the first line of each entry in the reference list should have one-half-inch hanging indentation from the left margin. (2)Authors’ names are inverted (last name first). If the work has more than seven authors, list the first six authors and then use ellipses after the sixt h author’s name. After the ellipses, list the last author’s name of the work. (3)Reference list entries should be alphabetized by the last name of the first author of each work. (4)If you have more than one article by the same author, single-author references or multiple-author references with the exact same authors in the exact same order are listed in order by the year of publication, starting with the earliest. (5)All major words in journal titles are capitalized. (6)When referring to books, chapters, articles, or Web pages, capitalize only the first letter of the first word of a title and subtitle, the first word after a colon or a dash in the title, and proper nouns. Do not capitalize the first letter of the second word in a hyphenated compound word. (7)Italicize titles of longer works such as books and journals. (8)Do not italicize, underline, or put quotes around the titles of shorter works such as journal articles or essays in edited collections. 1. Single-Author Book Aitchison, J. (1987). Words in the mind: An introduction to the mental lexicon. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd. Bach, K. (1987). Thought and reference. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2. Book with Two or More Authors Fodor, J., & Lepore, E. (2002). The compositionality papers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Hatch, E., & Brown, C. (1995). Vocabulary, semantics, and language education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 3. An Edited Volume Cole, P. (Ed). (1981). Radical pragmatics. New York: Academic Press. 4. Book without Author or Editor Listed Webster’s new collegiate dictionary. (1961). Springfield, MA: G. & C. Merriam. 5. Secondary Resources Sperber, D. (1994). The modularity of thought and the epistemology of representation. In L. A. Hirschfeld, & S. A. Gelman (Eds.), Mapping the mind: Domain specificity in cognition and culture (pp.39-67). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 6. Journals Barsalou, L. W. (1982). Context-independent information and context-dependent information in concepts. Memory & Cognition, 10, 82-93.

APA格式要求

APA格式要求: 每一段的开头应当按一下键盘上的Tab键再开始写而不是直接空格Indent(首行缩进) 双倍行间距 Double Space 字体要求Times New Roman 字体大小要求11-12号(教授的不同要求) 需要有页眉第一页的页眉要有Running head:(你的文章标题的简版,要求全部大写)还有页码在页眉的最右边,而第二页的页眉内容不需要Running head,只需要你的文章标题的简版+大写纸张的边距要求1英寸(2.54cm) 需要Title Page,上面要有文章名,作者名(你的),指导老师,科目,学校,日期,甚至于班级(这条按照不同的教授稍有不同的要求) 标题 标题是用来组织文章,使得其有层次架构。APA格式规定了文章内“标题”的特定格式(1到5级),第六版APA修订和简化的之前的标题格式。级数和格式如下: 第1级:居中、加粗的大小写标题(Centered, Boldface, Uppercase and Lowercase Headings) 第2级:左对齐、加粗的大小写标题(Left-aligned, Boldface, Uppercase and Lowercase Heading)

第3级:缩进、加粗,以句号结尾的小写标题(Indented, boldface, lowercase heading with a period.Begin body text after the period.) 第4级:缩进、加粗、斜体,以句号结尾的小写标题(Indented, boldface, italicized, lowercase heading with a period.Begin body text after the period.) 第5级:缩进、斜体,以句号结尾的小写标题(Indented, italicized, lowercase heading with a period.Begin body text after the period.) 总是从第1级标题开始使用,例如:(此处由于百科的问题无法显示格式,用文字解释,欢迎修改) (居中) Method(Level 1) (左对齐)Site of Study(Level 2) (左对齐)Participant Population(Level 2) (缩进) Teachers.(Level 3) (缩进) Students.(Level 3) (居中) Results(Level 1) (左对齐)Spatial Ability(Level 2) (缩进) Test one.(Level 3) (缩进) Teachers with experience.(Level 4) (缩进) Teachers in training.(Level 4) (缩进) Test two.(Level 3)

APA参考文献格式

APA文献参考文献著录格式(著者-出版年制)基本要求 1 正文中的文献引用标志 正文中的文献引用标志是著者(外国人只写姓,中国人的中文需写全姓名)和出版年,可以作为句子的一个成分,也可放在引用句尾的括号中,可以根据行文的需要灵活选用一种方式。 例如: Zhuang和Zhou (2001)的研究表明,省略~~~~~~. 过去的研究说明,省略~~~~(Zhuang & Zhou,2001) 2 正文后的文献列表 ?文献列表按著者姓氏字母顺序排列;著者相同,按出版年排列;著者和出版年都相同, 按文题的首字母顺序排列,出版年后加a、b、c… ?先列中文文献,后列英文文献。 ?中文文献中的著录符号需用英文(半角)符号。 ?英文逗号、点号、冒号后要留一空格。 ?著者姓名、出版年、文题、书名、出版信息等各个文献成分末尾用点号结束。 ?排版时需悬挂缩进。 常见的文献类型要求如下: 2.1 期刊论文 著者姓, 名. (出版年份). 文题. 刊名,卷号,起止页码. 示例: Tversky, B. (1981). Distortions in memory for maps. Cognitive Psychology,13, 407–433. Zhuang, J., & Zhou, X. L. (2001). Word length effect in speech production of Chinese. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 33, 214–218. 庄捷, 周晓林. (2001). 言语产生中的词长效应. 心理学报, 33, 214–218. ?姓需全拼,名只写首字母;姓氏后面有逗号,名的缩写字母后面有缩写点。 ?6个作者以后才能用“et al.”或“等”。 ?著者之间都用逗号隔开。两个或两个以上著者之间只有最后两个著者之间用“&”。?文题只有第一个单词的首字母大写,其余为小写(特殊要求大写的除外)。 ?刊名和卷号后用为逗号,字体为斜体。不需要写期刊的期号,除非期刊的每一期都是从 第1页开始编页码,才要写期号(期号和两边的括号为正体);如果全年各期页码是连续编号,则不需要写出期号,只需要写出卷号即可。 ?页码范围符号不是“-”,而是“–”。

APA格式参考文献清单制作简明规则

APA格式参考文献清单制作 简明规则 一、总的说明 1. 各个条目均不用给出文献标记类型(因为不是给国内期刊投稿),也不用。 2. 各个条目的后续行缩四个字符,即两个汉字的空间。 3. 英文的参考文献在上,中文的参考文献在下。 4. 中英文的条目均用字母升序排列,不用多余地以方括号括住的阿拉伯数字排 列(因为不是给国内期刊投稿)。 5. 结合本规则里的第一至第三部分,一一读懂本规则里的第四部分的实例,将 大有裨益。 6. 第四部分里的实例不能涵盖全部的情况,所以碰到本规则外的未尽情况时, 要多查阅权威参考书。 二、条目的制作 1. 姓名 1.1 姓在前,名在后,中间加逗号。 1.2 名字一律缩略,以缩略点结束。缩略点也就是结束点。 1.3 两个作者之间用&或and连接(前后保持一致),第一个作者的缩略名之后用 逗号。第二个作者也是姓名颠倒,中间用逗号。 1.4 三个作者时,头两个作者的缩略名后面均用逗号,第三个作者前用&或and。 第二个和第三个作者的姓名也颠倒,中间用逗号。 1.5 四个或四个以上的作者时,第一个作者的处理方法如第1条,其余作者只用 斜体的et al.代替。 1.6 没有作者姓名但有机构名称时,用该机构名代替作者姓名。 1.7 既没有作者名又没有机构名时,则顺延将文章名或书名代替(即条目的第一 部分是文章名或书名) 1.8 对书籍的篇章的条目而言,书籍本身的编者的姓名不颠倒。 2. 出版年份

2.1 放在作者名的后面,用圆括号。以句点结束。 2.2 杂志、报纸等出版物的文章除了提供年份之外,需要提供月份或月份加日子。 3. 出版物名称 3.1 书、期刊、报纸、长诗、长篇小说等用斜体。 3.2 书、长诗、长篇小说等用句子格式,但是名称内的专有名词和形容词仍需大 写。期刊、杂志、报纸等的文章用句子格式,但期刊、杂志和报纸等的名称用标题格式。 3.3 上述名称内如有副标题,则副标题后的首字母需要大写(即冒号后的首字母 要大写)。 3.4 文章不斜体,也不加引号。 4. 出版社所在的城市 4.1 凡是书籍的条目,一定要给出出版社所在的城市名。 4.2 如是不知名或容易搞错的外国城市名,则要给出城市所在的州名或郡名(不 是国名),州名(美国的州名)用缩略语。城市名和州名之间用逗号。城市名或州名后面用冒号。 4.3 城市名不要用缩略语。 4.4 出版社封面、扉页或版权页上给出两个城市,则可以照写这两个城市,用& 或and连接。如书上提供多个城市,则只写出最前的那个城市或最靠前的两个城市。 4.5 5. 出版社名称 5.1 出版社一般要用全称,不用缩略语。但出版社的非关键字眼应该省去,以便 简明扼要,如Co.、Inc.和Ltd.。 6. 书的章节(由各个作者撰写,引用某个章节) 6.1 首先给出章节的作者姓和名,做法一如1.1~1.7。 6.2 然后给出章节名称,用句子格式,不斜体。句点结束。 6.3 接着用介词in(首字母大写),给出编者的姓名,姓名不颠倒,但名字用缩