Tuning the Tadpole Improved Clover Wilson Action on Coarse Anisotropic Lattices

SBN陶瓷英文文献

Ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties of tungsten substituted SrBi 2Ta 2O 9ferroelectric ceramicsIndrani Coondoo *,S.K.Agarwal a ,A.K.Jha ba Superconductivity and Cryogenics Division,National Physical Laboratory,Dr K.S.Krishnan Road,New Delhi 110012,India bDepartment of Applied Physics,Delhi College of Engineering,Bawana Road,Delhi 110042,India1.IntroductionDefects in crystals significantly influence physical and various other properties of materials [1].For instance,as it is well known,doping by other elements leads to significant changes in the electrical properties of silicon.Historically,‘‘defect engineering’’has been developed in the field of semiconducting materials such as compound semiconductors as well as in diamond,Si and Ge [2–4].Subsequently,the concept of defect engineering has been applied to other functional materials,and the significant improve-ment in material properties have been achieved in high transition-temperature superconductors [5],amorphous SiO 2[6],photonic crystals [7]and also in the field of ferroelectrics,such as BaTiO 3,Pb(Ti,Zr)O 3(PZT),etc.[8,9].Various structural and electrical properties of bismuth layer-structured ferroelectrics (BLSF)are also strongly affected on deviation from stoichiometric composi-tions and defects have been recognized as a crucially important factor [10–13].It has been found that in BLSF small changes in chemical composition result in significantly altered dielectric and ferroelectric properties including dielectric constant and remanent polarization.In SrBi 2Ta 2O 9(SBT)and SrBi 2Nb 2O 9(SBN),orthor-hombic structural distortions with non-centrosymmetric spacegroup A 21am cause spontaneous ferroelectric polarization (P s )along a axis [14,15].SBT,a member of the BLSF family,has occupied an important position among the Pb-free ferroelectric memory materials [16–18].Tungsten (W 6+)has recently been investigated as a dopant for bismuth titanates and lanthanum doped bismuth titanates,in which the remanent polarization was observed to enhance when a small amount of Ti 4+was substituted by W 6+[19,20].With the objective to improve structural,dielectric and ferroelectric proper-ties,the hexavalent tungsten (W 6+)was chosen as a donor cation for partial replacement of the pentavalent tantalum (Ta 5+)SBT.In this report,the effect of tungsten substitution in SBT (SBTW),on the microstructural,ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties is reported.The results including the improvement in polarization properties have been discussed.2.ExperimentalSamples of compositions SrBi 2(W x Ta 1Àx )2O 9(SBWT),with x =0.0,0.025,0.050,0.075,0.10and 0.20were synthesized by solid-state reaction method taking SrCO 3,Bi 2O 3,Ta 2O 5and WO 3(all from Aldrich)in their stoichiometric proportions.The powder mixtures were thoroughly ground and passed through sieve of appropriate size and then calcined at 9008C in air for 2h.The calcined mixtures were ground and admixed with about 1–1.5wt%polyvinyl alcohol (Aldrich)as a binder and then pressed at $300MPa into disk shaped pellets.The pellets were sintered at 12008C for 2h in air.Materials Research Bulletin 44(2009)1288–1292A R T I C L E I N F O Article history:Received 3October 2008Received in revised form 5December 2008Accepted 6January 2009Available online 15January 2009Keywords:A.CeramicsC.X-ray diffractionD.FerroelectricityA B S T R A C TTungsten substituted samples of compositions SrBi 2(W x Ta 1Àx )2O 9(x =0.0,0.025,0.050,0.075,0.10and 0.20)were synthesized by solid-state reaction method and studied for their microstructural,electrical conductivity,ferroelectric and piezoelectric properties.The X-ray diffractograms confirm the formation of single phase layered perovskite structure in the samples with x up to 0.05.The temperaturedependence of dc conductivity vis-a`-vis tungsten content shows a decrease in conductivity,which is attributed to the suppression of oxygen vacancies.The ferroelectric and piezoelectric studies of the W-substituted SBT ceramics show that the remanent polarization and d 33values increases with increasing concentration of tungsten up to x 0.05.Such compositions with low conductivity and high P r values should be excellent materials for highly stable ferroelectric memory devices.ß2009Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.*Corresponding author.Present address:Liquid Crystal Group,National Physical Laboratory,Dr K.S.Krishnan Road,New Delhi 110012,India.Tel.:+919810361727;fax:+911125170387.E-mail address:indrani_coondoo@ (I.Coondoo).Contents lists available at ScienceDirectMaterials Research Bulletinj o ur n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w.e l se v i e r.c om /l oc a t e /m a t r e sb u0025-5408/$–see front matter ß2009Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.materresbull.2009.01.001X-ray diffractograms of the sintered samples were recorded using a Bruker diffractometer in the range 108 2u 708with CuK a radiation.The sintered pellets were polished to a thickness of 1mm and coated with silver paste on both sides for use as electrodes and cured at 5508C for half an hour.Electrical conductivity was performed using Keithley’s 6517A Electrometer.The polarization–electric field (P –E )hysteresis measurements were done at room temperature using an automatic P –E loop tracer based on Sawyer–Tower circuit.Piezoelectric charge co-efficient d 33was measured using a Berlincourt d 33meter after poling the samples in silicone–oil bath at 2008C for half an hour under a dc electric field of 60–70kV/cm.3.Results and discussion3.1.Structural and micro-structural studiesThe phase formation and crystal structure of the ceramics were examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD),which is shown in Fig.1.The XRD patterns of the samples show the characteristic peaks of SBT.The peaks have been indexed with the help of a computer program–POWDIN [21]and the refined lattice parameters are given in Table 1.It is observed that a single phase layered perovskite structure is maintained in the range 0.0 x 0.05.Owing to the same co-ordination number i.e.6and the smallerionic radius of W (0.60A˚)in comparison to Ta (0.64A ˚),there is a high possibility of tungsten occupying the tantalum site.The observance of unidentified peak of very low intensity in the compositions with x >0.05indicates the solubility limit of W concentration in SBT.The unidentified peak is possibly due to tungsten not occupying the Ta sites in the structure as the intensity of this peak is observed to increase with tungsten content.Composition and sintering temperature influences the micro-structure such as grain growth and densification of the specimen,which in turn control other properties of the material [11,13].The effects of W substitution on the microstructure have been examined by SEM and the obtained micrographs are shown in Fig.2.It shows the microstructure of the fractured surface of the studied samples.It is clearly observed that W substitution has pronounced effect on the average grain size and homogeneity of the grains.Randomly oriented and anisotropic plate-like grains are observed in all the samples.It is also observed that the average grain size increases gradually with increasing W content.The average grain size in the sample with x =0.0is $2–3m m while that in the sample with x =0.20the size increases to $5–7m m.3.2.Electrical studiesThe electrical conductivity of ceramic materials encompasses a wide range of values.In insulators,the defects w.r.t.the perfect crystalline structure act as charge carriers and the consideration of charge transport leads necessarily to the consideration of point defects and their migration [22].Many mechanisms were put forward to explain the conductivity mechanism in ceramics.Most of them are approximately divided into three groups:electronic conduction,oxygen vacancies ionic conduction,and ionic and p-type mixed conduction [22].Intrinsic conductivity results from the movement of the component ions,whereas conduction resulting from the impurity ions present in the lattice is known as extrinsic conductivity.At low temperature region (ferroelectric phase),the conduction is dominated by the extrinsic conduction,whereas the conduction at the high-temperature paraelectric phase ($300–7008C)is dominated by the intrinsic ionic conduction [23,25].Fig.3shows the temperature dependence of dc conductivity (s dc )for the undoped and doped SBT samples.The curves show that the conductivity increases with temperature.This is indicative of negative temperature coefficient of resistance (NTCR)behavior,a characteristic of dielectrics [22].It is observed in Fig.3that throughout the temperature range,the dc conductivity of the doped samples are nearly two to three orders lower than that of the undoped sample.Two predominant conduction mechanisms indicated by slope changes in the two different temperature regions are observed in Fig.3.Such changes in the slope in the vicinity of the ferro-paraelectric transition region have been observed in other ferroelectric materials as well [23,24].In addition,it is also observed (Table 2)that the activation energy calculated using the Arrhenius equation [22]in the paraelectric phase increase from $0.80eV for the undoped sample to $2eV for the doped samples.The X-ray photoemission spectroscopic study has confirmed that when Bi 2O 3evaporates during high-temperature processing,vacancy complexes are formed in the (Bi 2O 2)2+layers [26].As a result,defective (Bi 2O 2)2+layers are inherently present in SBT.The undoped SBT shows n-type conductivity,since when oxygen vacancies are created,it leaves behind two trapped electrons [27]:O o !12O 2"þV o þ2e 0(1)where O o is an oxygen ion on an oxygen site,V o is a oxygen vacant site and e 0represents electron.The conductivity in the perovskites can be described as an ordered diffusion of oxygen vacancies [28].Their motion is manifested by enhanced ionic conductivity associated with an activation energy value of $1eV [26].These oxygen vacancies can be suppressed by addition of donors,since the donor oxide contains more oxygen per cation than the host oxide it replaces [29].It has been reported that conductivity in Bi 4Ti 3O 12(BIT)can be significantly decreased,up to three orders of magnitude with the addition of donors,such as Nb 5+and Ta 5+at the Ti 4+sites [23,30].A few other studies on layered perovskites have also reported a decrease inconductivityFig.1.XRD patterns of SrBi 2(W x Ta 1Àx )2O 9samples sintered at 12008C.Table 1Lattice parameters of SrBi 2(W x Ta 1Àx )2O 9samples.Concentration of W a (A ˚)b (A ˚)c (A ˚)0.0 5.5212 5.513924.92230.025 5.5214 5.520225.10790.05 5.5217 5.519925.05850.075 5.5191 5.504525.05670.10 5.5142 5.506125.0850.205.51335.493925.0861I.Coondoo et al./Materials Research Bulletin 44(2009)1288–12921289with addition of donors [23,24,31].In the present study,the Ta 5+-site substitution by W 6+in SBT can be formulated using a defect chemistry expression as WO 3þV o!Ta 2O 512W Ta þ3O o (2)It shows that the oxygen vacancies are reduced upon the substitution of donor W 6+ions for Ta 5+ions.Hence,it is reasonable to believe that the conductivity in SBT is suppressed by donor addition.As per the above discussion,the high s dc observed in the undoped SBT (Fig.3)can be attributed to the motion of oxygen vacancies.As already discussed,the doped samples show reduced conductivity because the transport phenomena involving oxygen vacancies are greatly reduced.The high E a value of $1.75–2eVcorresponding to the high-temperature region in the doped ceramics is consistent with the fact that in the donor-doped materials,the ionic conduction reduces [32].The activation energy E a in the low temperature ferroelectric region (Table 2)corre-sponds to extrinsic conduction.At lower temperatures the extrinsic conductivity results from the migration of impurity ions in the lattice.Some of these impurities may also be associated with lattice defects.Pure SBT has large number of Schottky defects (oxygen vacancies)in addition to impurity ions whereas in the doped samples,due to charge neutrality,there is relatively less content of oxygen vacancies.Thus,in the doped samples the conductivity in the low temperature region is largely due to the impurity ions only.This explains the high activation energy in pure SBT in the low temperature region compared to doped samples (Table 2).In the high-temperature region,the value of E a in the doped samples is observed to increase with W concentration up to x =0.05but beyond that,it decreases (Table 2).The decrease in the activation energy for samples with x >0.05suggests an increase in the concentration of mobile charge carriers [33].This observation can be ascribed to the existence of multiple valence states of tungsten.Since tungsten is a transitional metal element,the valence state of W ions in a solid solution most likely varies from W 6+to W 4+depending on the surrounding chemical environment [34].When W 4+are substituted for the Ta 5+sites,oxygen vacancies would be created,i.e.one oxygen vacancy would be created for every two tetravalent W ions entering the crystal structure,whichFig.3.Variation of dc conductivity with temperature in SrBi 2(W x Ta 1Àx )2O 9samples.Fig.2.SEM micrographs of fractured surfaces of SrBi 2(W x Ta 1Àx )2O 9samples with (a)x =0.0,(b)x =0.025,(c)x =0.050,(d)x =0.075,(e)x =0.10and (f)x =0.20Table 2Activation energy (E a )in the high-temperature paraelectric region and low temperature ferroelectric region;Curie temperature (T c )in SrBi 2(W x Ta 1Àx )2O 9samples.Concentration of W E a (high temp.)(eV)E a (low temp.)(eV)T c (8C)0.00.790.893110.025 1.920.593080.05 1.960.543250.075 1.940.543380.10 1.860.573680.201.740.54390I.Coondoo et al./Materials Research Bulletin 44(2009)1288–12921290explains the increase in the concentration of mobile charge carriers which ultimately results in an decrease in the E a beyond x>0.05. Hence it is reasonable to conclude that W ions in the SBWT exists as a varying valency state,i.e.at lower doping concentration they exist in hexavalent state(W6+)and at a higher doping concentra-tion,they tend to exist in lower valency states[8].The P–E loops of SrBi2(Ta1Àx W x)2O9are shown in Fig.4.It is observed that W-doping results in formation of well-defined hysteresis loops.Fig.5shows the compositional dependence of remanent polarization(2P r)and the coercivefield(2E c)of SrBi2(Ta1Àx W x)2O9samples.Both the parameters depend on W content of the samples.It is observed that2P rfirst increases with x and then decreases while2E cfirst decreases with x and then increases(Fig.5).The optimum tungsten content for maximum2P r ($25m C/cm2)is observed to be x=0.075.It is known that ferroelectric properties are affected by compositional modification,microstructural variation and lattice defects like oxygen vacancies[10,35,36].In hard ferroelectrics, with lower valent substituents,the associated oxide vacancies are likely to assemble in the vicinity of domain walls[37,38].These domains are locked by the defects and their polarization switching is difficult,leading to an increase in E c and decrease in P r[38]. On the other hand,in soft ferroelectrics,with higher valent substituents,the defects are cation vacancies whose generation in the structure generally increases P r.Similar observations have been made in many reports[38–41].Watanabe et al.[42]reported a remarkable improvement in ferroelectric properties in the Bi4Ti3O12ceramic by adding higher valent cation,V5+at the Ti4+ site.It has also been reported that cation vacancies generated by donor doping make domain motion easier and enhance the ferroelectric properties[43].Further,it is known that domain walls are relatively free in large grains and are inhibited in their movement as the grain size decreases[44].In the larger grains, domain motion is easier which results in larger P r.Also for the SBT-based system,it is known that with increase in the grain size the remanent polarization also increases[45,46].Based on the obtained results and above discussion,it can be understood that in the undoped SBT,the oxygen vacancies assemble at sites near domain boundaries leading to a strong domain pinning.Hence,as observed,well-saturated P–E loop for pure SBT is not obtained.But in the doped samples,the suppression of the oxygen vacancies reduces the pinning effect on the domain walls,leading to enhanced remanent polarization and lower coercivefield.Also,the increase in grain size in tungsten added SBT,as observed in SEM micrographs(Fig.2)contribute to the increase in polarization values.In the present study,the grain size is observed to increase with increasing W concentration.However, the2P r values do not monotonously increase and neither the E c decreases continuously with increasing W concentration(Fig.5). The variation of P r and E c beyond x>0.05,seems possibly affected by the presence of secondary phases(observed in XRD diffracto-grams),which hampers the switching process of polarization [47–50].Also,beyond x>0.05the increase in the number of charge carriers in the form of oxygen vacancies leads to pinning of domain walls and thus a reduction in the values of P r and increase in E c is observed.Fig.6shows the variation of piezoelectric charge coefficient d33 with x in the SrBi2(Ta1Àx W x)2O9.The d33values increases with increase in W content up to x=0.05.A decrease in d33values is observed in the samples with x!0.075.The piezoelectric coefficient,d33,increases from13pC/N in the sample with x=0.0to23pC/N in the sample with x=0.05.It is known that the major drawback of SBT is its relatively higher conductivity,which hinders proper poling[51].High resistivity is therefore important for maintenance of poling efficiency at high-temperature[52,53].The W-doped SBT samples show an electrical conductivity value up to three orders of magnitude lower than that of undoped sample(Fig.3).The positional variation of2P r and2E c in SrBi2(W x Ta1Àx)2O9samples.Fig.6.Variation of d33in SrBi2(W x Ta1Àx)2O9samples.Fig. 4.P–E hysteresis loops in SrBi2(W x Ta1Àx)2O9samples recorded at roomtemperature.I.Coondoo et al./Materials Research Bulletin44(2009)1288–12921291decrease in conductivity upon donor doping improve the poling efficiency resulting in the observed higher d33values.Moreover, since the grain size increases with W content in SBT,it is reasonable to believe that the increase in grain size will also contribute to the increase in d33values[54].The decrease in the value of d33for samples with x!0.075is possibly due to the presence of secondary phases as observed in diffractograms[1,51,55]and the increase in oxygen vacancies for samples with x>0.05.4.ConclusionsX-ray diffractograms of the samples reveal that the single phase layered perovskite structure is maintained in the samples with tungsten content x0.05.SEM micrographs reveal that the average grain size increases with increase in W concentration. The temperature dependence of the electrical conductivity shows that tungsten doping results in the decrease of conductivity by up to three order of magnitude compared to W free SBT.All the tungsten-doped ceramics have higher2P r than that of the undoped sample.The maximum2P r($25m C/cm2)is obtained in the composition with x=0.075.The reduced conductivity allows high-temperature poling of the doped samples.Such compositions with low loss and high P r values should be excellent materials for highly stable ferroelectric memory devices.The d33value is observed to increase with increasing W content up to x0.05.The value of d33 in the composition with x=0.05is$23pC/N as compared to$13 pC/N in the undoped sample.AcknowledgmentsThe authors sincerely thank Prof.P.B.Sharma,Dean,Delhi College of Engineering,India for his generous support and providing ample research infrastructure to carry out the research work.The authors are thankful to Dr.S.K.Singhal,Scientist, National Physical Laboratory,India for his fruitful discussion and suggestions.References[1]Y.Noguchi,M.Miyayama,K.Oikawa,T.Kamiyama,M.Osada,M.Kakihana,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.41(2002)7062.[2]A.Bonaparta,P.Giannozzi,Phys.Rev.Lett.84(2000)3923.[3]S.Connell,E.Siderashaddad,K.Bharuthram,C.Smallman,J.Sellschop,M.Bos-senger,Nucl.Instrum.Methods B85(1994)508.[4]T.Derry,R.Spits,J.Sellschop,Mater.Sci.Bull.11(1992)249.[5]K.Salama,D.F.Lee,Supercond.Sci.Technol.7(1994)177.[6]H.Hosono,Y.Ikuta,T.Kinoshita,M.Hirano,Phys.Rev.Lett.87(2001)175501.[7]S.Noda,A.Chutinan,M.Imada,Nature407(1999)608.[8]S.Shannigrahi,K.Yao,Appl.Phys.Lett.86(2005)092901.[9]G.H.Heartling,nd,J.Am.Ceram.Soc.54(1971)1.[10]H.Watanabe,T.Mihara,H.Yoshimori,C.A.Paz De Araujo,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.34(1995)5240.[11]T.Atsuki,N.Soyama,T.Yonezawa,K.Ogi,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.34(1995)5096.[12]T.Noguchi,T.Hase,Y.Miyasaka,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.35(1996)4900.[13]M.Noda,Y.Matsumuro,H.Sugiyama,M.Okuyama,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.38(1999)2275.[14]R.E.Newnham,R.W.Wolfe,R.S.Horsey,F.A.D.Colon,M.I.Kay,Mater.Res.Bull.8(1973)1183.[15]A.D.Rae,J.G.Thompson,R.L.Withers,Acta Crystallogr.Sect.B:Struct.Sci.48(1992)418.[16]H.M.Tsai,P.Lin,T.Y.Tseng,J.Appl.Phys.85(1999)1095.[17]Y.Shimakawa,Y.Kubo,Y.Nakagawa,T.Kamiyama,H.Asano,F.Izumi,Appl.Phys.Lett.74(1999)1904.[18]Y.Noguchi,M.Miyayama,T.Kudo,Phys.Rev.B63(2001)214102.[19]J.K.Kim,T.K.Song,S.S.Kim,J.Kim,Mater.Lett.57(2002)964.[20]W.T.Lin,T.W.Chiu,H.H.Yu,J.L.Lin,S.Lin,J.Vac.Sci.Technol.A21(2003)787.[21]Wu E.,POWD,An interactive powder diffraction data interpretation and indexingprogram Ver2.1,School of Physical Science,Flinders University of South Australia, Bedford Park,S.A.JO42AU.[22]R.C.Buchanan,Ceramic Materials for Electronics:Processing,Properties andApplications,Marcel Dekker Inc.,New York,1998.[23]H.S.Shulman,M.Testorf,D.Damjanovic,N.Setter,J.Am.Ceram.Soc.79(1996)3124.[24]M.M.Kumar,Z.G.Ye,J.Appl.Phys.90(2001)934.[25]Y.Wu,G.Z.Cao,J.Mater.Res.15(2000)1583.[26]B.H.Park,S.J.Hyun,S.D.Bu,T.W.Noh,J.Lee,H.D.Kim,T.H.Kim,W.Jo,Appl.Phys.Lett.74(1999)1907.[27]C.A.Palanduz,D.M.Smyth,J.Eur.Ceram.Soc.19(1999)731.[28]C.R.A.Catlow,Superionic Solids&Solid Electrolytes,Academic Press,New York,1989.[29]M.V.Raymond,D.M.Symth,J.Phys.Chem.Solids57(1996)1507.[30]S.S.Lopatin,T.G.Lupriko,T.L.Vasiltsova,N.I.Basenko,J.M.Berlizev,Inorg.Mater.24(1988)1328.[31]M.Villegas,A.C.Caballero,C.Moure,P.Duran,J.F.Fernandez,J.Eur.Ceram.Soc.19(1999)1183.[32]Y.Wu,G.Z.Cao,J.Mater.Sci.Lett.19(2000)267.[33]B.H.Venkataraman,K.B.R.Varma,J.Phys.Chem.Solids66(2005)1640.[34]C.D.Wagner,W.M.Riggs,L.E.Davis,F.J.Moulder,Handbook of X-ray Photoelec-tron Spectroscopy,Perkin Elmer Corp.,Chapman&Hall,1990.[35]Y.Noguchi,I.Miwa,Y.Goshima,M.Miyayama,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.39(2000)1259.[36]M.Yamaguchi,T.Nagamoto,O.Omoto,Thin Solid Films300(1997)299.[37]W.Wang,J.Zhu,X.Y.Mao,X.B.Chen,Mater.Res.Bull.42(2007)274.[38]T.Friessnegg,S.Aggarwal,R.Ramesh,B.Nielsen,E.H.Poindexter,D.J.Keeble,Appl.Phys.Lett.77(2000)127.[39]Y.Noguchi,M.Miyayama,Appl.Phys.Lett.78(2001)1903.[40]Y.Noguchi,I.Miwa,Y.Goshima,M.Miyayama,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.39(2000)L1259.[41]B.H.Park,B.S.Kang,S.D.Bu,T.W.Noh,L.Lee,W.Joe,Nature(London)401(1999)682.[42]T.Watanabe,H.Funakubo,M.Osada,Y.Noguchi,M.Miyayama,Appl.Phys.Lett.80(2002)100.[43]S.Takahashi,M.Takahashi,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.11(1972)31.[44]R.R.Das,P.Bhattacharya,W.Perez,R.S.Katiyar,Ceram.Int.30(2004)1175.[45]S.B.Desu,P.C.Joshi,X.Zhang,S.O.Ryu,Appl.Phys.Lett.71(1997)1041.[46]M.Nagata,D.P.Vijay,X.Zhang,S.B.Desu,Phys.Stat.Sol.(a)157(1996)75.[47]J.J.Shyu,C.C.Lee,J.Eur.Ceram.Soc.23(2003)1167.[48]I.Coondoo,A.K.Jha,S.K.Agarwal,Ferroelectrics326(2007)35.[49]T.Sakai,T.Watanabe,M.Osada,M.Kakihana,Y.Noguchi,M.Miyayama,H.Funakubo,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.42(2003)2850.[50]C.H.Lu,C.Y.Wen,Mater.Lett.38(1999)278.[51]R.Jain,V.Gupta,A.Mansingh,K.Sreenivas,Mater.Sci.Eng.B112(2004)54.[52]I.S.Yi,M.Miyayama,Jpn.J.Appl.Phys.36(1997)L1321.[53]A.J.Moulson,J.M.Herbert,Electroceramics:Materials,Properties,Applications,Chapman&Hall,London,1990.[54]H.T.Martirena,J.C.Burfoot,J.Phys.C:Solid State Phys.7(1974)3162.[55]R.Jain,A.K.S.Chauhan,V.Gupta,K.Sreenivas,J.Appl.Phys.97(2005)124101.I.Coondoo et al./Materials Research Bulletin44(2009)1288–1292 1292。

矿物加工技术双语翻译

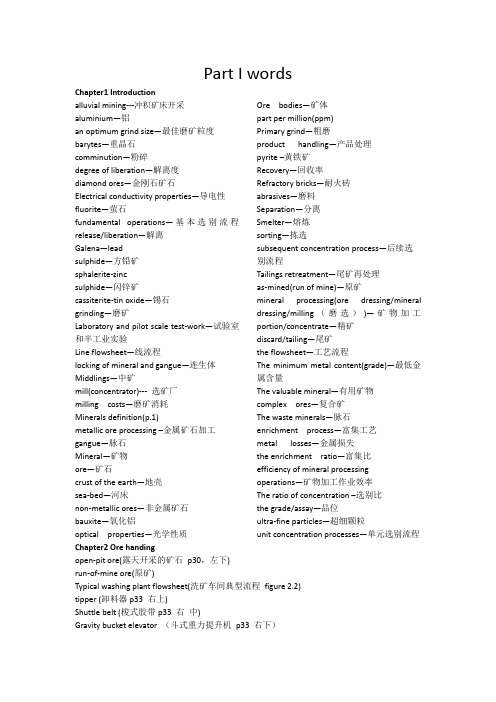

PartI words Chapter1 Introductionalluvial mining---冲积矿床开采aluminium—铝an optimum grind size—最佳磨矿粒度barytes—重晶石comminution—粉碎degree of liberation—解离度diamond ores—金刚石矿石Electrical conductivity properties—导电性fluorite—萤石fundamental operations—基本选别流程release/liberation—解离Galena—leadsulphide—方铅矿sphalerite-zincsulphide—闪锌矿cassiterite-tin oxide—锡石grinding—磨矿Laboratory and pilot scale test-work—试验室和半工业实验Line flowsheet—线流程locking of mineral and gangue—连生体Middlings—中矿mill(concentrator)--- 选矿厂milling costs—磨矿消耗Minerals definition(p.1)metallic ore processing –金属矿石加工gangue—脉石Mineral—矿物ore—矿石crust of the earth—地壳sea-bed—河床non-metallic ores—非金属矿石bauxite—氧化铝optical properties—光学性质Ore bodies—矿体part per million(ppm)Primary grind—粗磨product handling—产品处理pyrite –黄铁矿Recovery—回收率Refractory bricks—耐火砖abrasives—磨料Separation—分离Smelter—熔炼sorting—拣选subsequent concentration process—后续选别流程Tailings retreatment—尾矿再处理as-mined(run of mine)—原矿mineral processing(ore dressing/mineral dressing/milling(磨选))—矿物加工portion/concentrate—精矿discard/tailing—尾矿the flowsheet—工艺流程The minimum metal content(grade)—最低金属含量The valuable mineral—有用矿物complex ores—复合矿The waste minerals—脉石enrichment process—富集工艺metal losses—金属损失the enrichment ratio—富集比efficiency of mineral processing operations—矿物加工作业效率The ratio of concentration –选别比the grade/assay—品位ultra-fine particles—超细颗粒unit concentration processes—单元选别流程Chapter2Ore handingopen-pit ore(露天开采的矿石p30,左下)run-of-mine ore(原矿)Typical washing plant flowsheet(洗矿车间典型流程figure 2.2) tipper (卸料器p33 右上)Shuttle belt (梭式胶带p33 右中)Gravity bucket elevator (斗式重力提升机p33 右下)Ore storage(矿物储存p35 右上)包括:stockpile (矿场)bin(矿仓)tank (贮槽)Front-end loader (前段式装载机p35 右上)Bucket-wheel reclaimer(斗轮式装载机p35 右上)Reclaim tunnel system(隧道装运系统p35 右上)The amount of reclaimable material/the live storage(有效贮量p35 右中figure 2.7) Conditioning tank (调和槽p36 左上)Chain-feeder (罗斯链式给矿机figure 2.9)Cross-section of elliptical bar feeder (椭圆形棒条给矿机figure 2.10)Vibrating grizzly feeder (振动格筛给矿机p37 左上)Apron feeder (板式给矿机figure 2.11)Belt feeder (胶带给矿机p37 右下)Chapter 4 particle size analysisacicular(针状);adverse(相反的);algorithm(算法);angular(多角状);aperture(孔径);apex (顶点);apparatus(仪器);arithmetic(运算器,算术); assaying(化验);attenuation(衰减);beaker decantation(烧杯倾析); blinding(阻塞);calibration(校正);charge(负荷);congest(充满);consecutive(连续的);contract(压缩);convection current(对流); conversion factor(转化因子); crystalline(晶体状);cyclosizer(旋流分析仪);de-aerated(脱气);derive:(得出);dilute(稀释);dimensionless quantity(无量纲量); dispersing agent(分散剂);distort(变形);duplicate(重复); electrical impedence(电阻); electroetching(电蚀刻); electroform(电铸);elutriation(淘析);epidote(绿帘石);equilateral triangle(等边三角形); flaky(薄片状);flask(烧瓶);fractionated sample(分级产品); gauze(筛网);geometric(几何学的);granular(粒状的);graticule(坐标网);gray scale(灰度);ground glass(毛玻璃);hand sieve(手动筛);histogram(直方图);immersion(浸没);inter-conversion(相互转变); interpolate(插值);intervals(区间);laminar flow(粘性流体);laser diffraction(激光衍射);light scattering method(光散射法); line of slope(斜率);logarithmic(对数的);machine sieve(机械筛); mechanical constraint(机械阻力);mesh(目);modular(系数的,制成有标准组件的);near size(临界筛孔尺寸);nominal aperture();nylon(尼龙);opening(开口);ordinate(纵坐标);perforated(多孔的);pipette(吸管);plotting cumulative undersize(累积筛下曲线); median size(中间粒度d50);polyhedron(多面体); reflection(反射); procure(获得);projected area diameter(投影面直径);ratio of the aperture width(筛比);refractive index(折射率);regression(回归) ;reproducible(可再生的);sedimentation balance(沉降天平); sedimentation(沉降) ;segment(片);sensor section(传感器); sieve shaker(振动筛,振筛器); spreadsheet(电子表格);simultaneously(同时地);size distribution(粒度分布);spectrometer(摄谱仪);stokes diameter(斯托克斯直径);subdivide(细分);sub-sieve(微粒);suction(吸入);syphon tube(虹吸管);tabulate(列表);tangential entry(切向入口);terminal velocity(沉降末速);truncate(截断);twill(斜纹图);two way cock(双通塞);ultra sonic(超声波);underside(下侧);vertex(顶点);vortex outlet (涡流出口);wetting agent(润湿剂);Chapter 5 comminutionattrition----- 研磨batch-type grindability test—小型开路可磨性实验bond’s third theory—邦德第三理论work index----功指数breakage—破碎converyor--- 运输机crack propagation—裂隙扩展crushing and grinding processes—破碎磨矿过程crushing----压扎crystalline material—晶状构体physical and chemical bond –物理化学键diameter—直径elastic—弹性fine-grained rocks—细粒岩石coarse-grained rocks—粗粒岩石chemical additives—化学添加剂fracture----碎裂free surface energy—自由表面能potential energy of atoms—原子势能graphical methods---图解法grindability test—可磨性实验crushing and grinding efficiency--- 破碎磨矿效率grinding media—磨矿介质gyratory crusher---旋回破碎机tumbling mill --- 筒形磨矿机impact crusher—冲击式破碎机high pressure griding roll--高压辊磨impact breaking-冲击破碎impact—冲击jaw—颚式破碎机material index-材料指数grindability—可磨性mill----选矿厂non-linear regression methods--- 非线性回归法ore carry--- 矿车Parameter estimation techniques—参数估计技术reduction ratio—破碎比roll crusher—辊式破碎机operating work indices—操作功指数Scraper—电铲slurry feed—矿浆SPI(SAG Power Index)—SAG 功指数simulation of comminution processes and circuits—粉碎工艺流程模拟stirred mill—搅拌磨stram energy---应变能the breakage characteristics—碎裂特性the crystalline lattice—晶格the reference ore---参比矿石product size distribution--- 产品粒度分布theory of comminution—粉碎理论brittle—脆性的tough material--- 韧性材料platstic flow—塑性流动Tracer methods—示踪法vibration mill-- 振动磨矿机Chapter 6CrushersAG/SAG mills(autogenousgrinding/semiautogenous grinding) 自磨、半自磨Alternating working stresses交替工作应力Amplitude of swing 摆幅Arrested or free crushing 夹压碎矿、自由碎矿Bell-shaped 钟形Belt scales 皮带秤Binding agents 粘结剂Bitumen 沥青Blending and rehandling 混合再处理Breaker plate 反击板Capital costs 基建费用Capstan and chain 铰杆铰链Cast iron or steel 铸铁铸钢Chalk 白垩Cheek plates 夹板Choke fed 阻塞给矿(挤满给矿)Choked crushing 阻塞碎矿Chromium carbide 碳铬合金Clay 粘土Concave 凹的Convex 凸的Corrugated 波纹状的Cross-sectional area 截面积Cross-section剖面图Crusher gape 排矿口Crusher throat 破碎腔Crushing chamber 破碎腔Crushing rolls 辊式碎矿机Crushing 破碎Discharge aperture 排矿口Double toggle 双肘板Drilling and blasting 打钻和爆破Drive shaft 驱动轴Eccentric sleeve 偏心轴套Eccentric 偏心轮Elliptical 椭圆的Epoxy resin 环氧树脂垫片Filler material 填料Fixed hammer impact mill 固定锤冲击破碎机Flakes 薄片Flaky 薄而易剥落的Floating roll 可动辊Flywheel 飞轮Fragmentation chamber 破碎腔Grizzlies 格条筛Gypsum 石膏Gyratory crushers 旋回破碎机Hammer mills 锤碎机Hydraulic jacking 液压顶Idle 闲置Impact crushers 冲击式破碎机Interparticle comminution 粒间粉碎Jaw crushers 颚式破碎机Limestone 石灰岩Lump 成块Maintenance costs 维修费Manganese steel mantle 锰钢罩Manganese steel 锰钢Mechanical delays 机械检修Metalliferous ores 有色金属矿Nip 挤压Nodular cast iron 球墨铸铁Nut 螺母Pack 填充Pebble mills 砾磨Pillow 垫板Pitman 连杆Pivot 轴Plates 颚板Primary crushing 初碎Receiving areas 受矿面积Reduction ratio 破碎比Residual stresses 残余应力Ribbon 流量Rivets 铆钉Rod mills 棒磨Roll crushers 辊式碎矿机Rotary coal breakers 滚筒碎煤机Rotating head 旋回锥体Scalp 扫除Secondary crushing 中碎Sectionalized concaves分段锥面Set 排矿口Shales 页岩Silica 二氧化硅Single toggle 单肘板Skips or lorries 箕斗和矿车Spider 壁架Spindle 竖轴Springs 弹簧Staves 环板Steel forgings 锻件Stroke 冲程Stroke 冲程Surge bin 缓冲箱Suspended bearing 悬吊轴承Swell 膨胀Swinging jaw 动颚Taconite ores 铁燧岩矿石Tertiary crushing 细碎The (kinetic) coefficient of friction (动)摩擦系数The angle of nip啮角The angle of repose 安息角The cone crusher 圆锥破碎机The cone lining 圆锥衬里The gyradisc crusher 盘式旋回碎矿机Thread 螺距Throughput 处理量Throw 冲程Tripout 停机Trommel screen 滚筒筛Valve 阀Vibrating screens 振动筛Wear 磨损Wedge-shaped 锥形Chapter 7 grinding millsAbrasion 磨蚀Alignment Amalgamation 融合/汞剂化Asbestos 石棉Aspect ratio 纵横比/高宽比Attrition 磨蚀Autogenous mill 自磨机Ball mill 棒磨Barite 重晶石Bearing 轴承Bellow 吼叫Belly 腹部Best-fit 最优化Bolt 螺栓Brittle 易碎的Build-up 增强Butt-weld 焊接Capacitance 电容量Cascade 泻落Cataract 抛落Central shaft 中心轴Centrifugal force 离心力Centrifugal mill 离心磨Chipping 碎屑Churning 搅拌器Circulating load 循环负荷Circumferential 圆周Clinker 渣块Cobbing 人工敲碎Coiled spring 盘簧Comminution 粉碎Compression 压缩Contraction 收缩Corrosion 腐蚀Corrugated 起褶皱的Crack 裂缝Critical speed 临界速度Crystal lattice 晶格Cushion 垫子Cyanide 氰化物Diagnose 诊断Dilute 稀释Discharge 放电Drill coreElastic 有弹性的Electronic belt weigher 电子皮带秤Elongation 延长率Emery 金刚砂Energy-intensive 能量密度Entangle 缠绕Expert system 专家系统Explosives 易爆炸的Flange 破碎Fracture 折断、破碎Front-end loader 前段装备Gear 齿轮传动装置Girth 周长Granulate 颗粒状的Grate discharge 磨碎排矿GreenfieldGrindability 可磨性Grinding media 磨矿介质Groove 沟槽Helical 螺旋状的High carbon steel 高碳钢High pressure grinding roll 高压滚磨Hopper 加料斗Housing 外壳Impact 冲击Impeller 叶轮IntegralInternal stress 内部压力Kinetic energy 运动能Least-square 最小平方Limestone 石灰岩Liner 衬板Lock 锁Lubricant 润滑剂Magnetic metal liner 磁性衬板Malleable 有延展性的Manhole 检修孔Material index 材料指数Matrix 矿脉Muffle 覆盖Multivariable control 多元控制Newtonian 牛顿学的Nodular cast iron 小块铸铁Non-Newtonian 非牛顿的Normally 通常Nuclear density gauge 核密度计Nullify废弃Oblique间接地,斜的Operating 操作Orifice 孔Output shaft 产量轴Overgrinding 过磨Parabolic 像抛物线似地Pebble 砾石Pebble mill 砾磨PendulumPilot scale 规模试验Pinion 小齿轮Pitting 使留下疤痕Plane 水平面PloughPotential energy 潜力Pressure transducer 压力传感器Prime moverPrismatic 棱柱形的Probability 可能性/概率Propagation 增值Pulp density 矿浆密度Pulverize 粉碎Quartzite 石英岩Radiused 半径Rake 耙子Reducer还原剂Reduction ratio 缩小比Retention screenRetrofit 改进Rheological 流变学的Rib骨架Rod 棒Roller-bearing 滚动轴承Rotor 旋转器Rubber liner 橡胶衬板Rupture 裂开ScatsScoop铲起Scraper 刮取器Screw flight 螺旋飞行Seasoned 干燥的SegregationSet-point 选点Shaft 轴Shear 剪Shell 外壳Simulation 模拟SlasticitySpalling 击碎Spigot 龙头Spill 溢出/跌落Spin 使什么旋转Spiral classifier 螺旋分级机Spout 喷出Stationary 静止的Stator 固定片Steady-state 不变的Steel plate 钢盘Steel-capped 钢帽Stirred mill搅拌磨Stress concentration 应力集中Sump 水池Taconite 铁燧岩Tensile stress 拉伸力Thicken 浓缩Throughput 生产量Thyristor 半导体闸流管Time lag 时间间隔Tower mill塔磨Trajectory 轨迹Trial and error 反复试验Trunnion 耳轴Tube millTumbling mill 滚磨Undergrinding 欠磨Underrun 低于估计产量Unlock 开启Vibratory mill 振动磨Viscometer 黏度计Viscosity 黏性Warp 弯曲Wearing linerWedged 楔形物Work index 功指数Chapter 8Industrial screeningBauxite 铝土矿Classification 分级Diagonal 斜的Dry screening 干筛Efficiency or partition curve 效率曲线、分离曲线Electrical solenoids 电磁场Elongated and slabby particles 细长、成板层状颗粒Granular 粒状Grizzly screens 格筛Hexagons 六边形Hydraulic classifiers 水力旋流器Linear screen 线性筛Mesh 网眼Mica 云母Near-mesh particles 近筛孔尺寸颗粒Octagons 八边形Open area 有效筛分面积Oscillating 振荡的Perpendicular 垂直的Polyurethane 聚氨酯Probabilistic 概率性的Resonance screens 共振筛Rhomboids 菱形Rinse 漂洗Rubber 橡胶Screen angle 颗粒逼近筛孔的角度Shallow 浅的Static screens 固定筛Tangential 切线的The cut point(The separation size)分离尺寸Trommels 滚筒筛Vibrating screens 振动筛Water sprays 喷射流Chapter9 classification added increment(增益)aggregate(聚集)alluvial(沉积)apex(顶点) deleterious(有害) approximation(概算,近似值)apron(挡板)buoyant force(浮力)correspond(符合,相符)critical dilution(临界稀释度)cut point(分离点)descent(降落)dilute(稀释的)drag force(拖拽力)duplex(双)effective density(有效比重)emergent(分离出的)equilibrium(平衡)exponent(指数)feed-pressure gauge(给矿压力表)free-settling ratio(自由沉降比)full teeter(完全摇摆流态化)geometry(几何尺寸)helical screw(螺旋沿斜槽)hindered settling(干涉沉降)hollow cone spray(中空锥体喷流)Hydraulic classifier(水力分级机)imperfection(不完整度)incorporated(合并的)infinite(任意的)involute(渐开线式)Mechanical classifier(机械分级机)minimize(最小限度的)multi-spigot hydro-sizer(多室水力分级机)pressure-sensitive valve(压敏阀)Newton’s law(牛顿定律)orifice(孔)overflow(溢流)parallel(平行的,并联的)performance or partition curve(应用特性曲线)predominate(主导)pulp density(矿浆比重)quadruple(四倍)quicksand(流砂体)Reynolds number(雷诺数)scouring(擦洗)Settling cones(圆锥分级机)shear force(剪切力)simplex(单)simulation(模拟)slurry(矿浆)sorting column(分级柱)spherical(球形的)spigot(沉砂)Spiral classifiers(螺旋分级机)Stokes’ law(斯托克斯定律)surging(起伏波动)suspension(悬浮液)tangential(切线式)Teeter chamber(干涉沉降室)teeter(摇摆)terminal velocity(末速)The rake classifier(耙式分级机) turbulent resistance(紊流阻力)underflow (底流)vertical axis(垂直轴)vessel(分级柱)viscosity(粘度)viscous resistance(粘滞阻力) vortex finder(螺旋溢流管)well-dispersed(分散良好的)Chapter 10gravity concentrationactive fluidised bed(流化床); amplitude(振幅);annular(环状的); asbestos(石棉); asymmetrical (非对称的); baddeleyite (斜锆石); barytes (重晶石); cassiterite (锡石); chromite(铬铁矿);circular (循环的); circumference (圆周); closed-circuit (闭路);coefficient of friction (摩擦系数); compartment (隔箱);concentration criterion (分选判据); conduit(管);contaminated(污染);counteract (抵消);degradation (降解);density medium separation (重介质分选); detrimental(有害的);diaphragm (隔膜);dilate (使膨胀);displacement (置换);divert (转移);dredge (挖掘船);eccentric drive(偏心轮驱动); encapsulate (密封);equal settling rate(等沉降比);evenly(均匀的);excavation (采掘);exhaust (废气);feed size range (给矿粒度范围); fiberglass (玻璃纤维);flash floatation (闪浮);flattened(变平);float (浮子);flowing film (流膜);fluid resistance (流体阻力);gate mechanism (开启机制);halt(停止);hand jig (手动跳汰机);harmonic waveform (简谐波);helical(螺旋状的);hindered settling (干涉沉降);hutch(底箱);immobile (稳定);interlock (连结);interstice (间隙);jerk(急拉);kyanite (蓝晶石);lateral (侧向的,横向的);linoleum (漆布);mica(云母);momentum (动量) ;mount(安装);multiple (多重的);multi-spigot hydrosizer (多室水力分级机); natural gravity flower (自流); neutralization (中和作用);nucleonic density gauge (核密度计); obscure (黑暗的,含糊不清的); obsolete (报废的);onsolidation trickling (固结滴沉);open-circuit (开路);pebble stone/gravels(砾石); periphery(周边的);pinched (尖缩的) ;platelet(片晶);platinum(铂金);plunger (活塞);pneumatic table(风力摇床); pneumatically (靠压缩空气); porus(孔);preset(预设置);pressure sensing(压力传感的); pressurize (加压);pulsating (脉动的);pulsion/suction stroke (推/吸冲程); quotient (商);radial(径向的);ragging (重物料残铺层);rate of withdraw (引出速率);raw feed (新进料);reciprocate(往复);refuse (垃圾);render (使得);residual (残留的);retard(延迟);riffle (床条);rinse(冲洗);rod mill (棒磨);rotary water vale (旋转水阀); rubber(橡胶);saw tooth (锯齿形的);scraper(刮板);sectors(扇形区);semiempirical(半经验的); settling cone (沉降椎);shaft (轴);side-wall (侧壁);sinterfeed (烧结料);sinusoidal (正弦曲线);slime table(矿泥摇床);sluice (溜槽);specular hematite (镜铁矿); spinning (自转;离心分离); splitters (分离机);starolite (星石英);staurolite (十字石);stratification (分层); stratum (地层); submerge (浸没);sump (池); superimposed (附加的); surge capacity (缓冲容量); synchronization (同步的); throughput(生产能力); tilting frames (翻筛); timing belt (同步带); trapezoidal shaped (梯形的); tray (浅盘) ;trough(槽);tungsten (钨);uneven (不均匀的);uniformity(均匀性);uranolite (陨石);validate(有效);vicinity (附近);water (筛下水);wolframite (黑钨矿,钨锰铁矿);Chapter 11 dense medium separation(DMS) barite(重晶石)Bromoform(溴仿)bucket(桶)carbon tetrachloride(四氯化碳)centrifugal(离心的)chute(陡槽)Clerici solution(克莱利西溶液)corrosion(腐蚀)dependent criterion(因变判据)discard(尾渣)disseminate(分散,浸染)DMS(重介质分选)dominant(主导)Drewboy bath(德鲁博洗煤机)drum separator(双室圆筒选矿机)Drum separator(圆筒选矿机)Dyna Whirlpool()effective density of separation(有效分选比重)envisage(设想)feasibility(可行性)ferrosilicon(硅铁)flexible sink hose(沉砂软管)fluctuation(波动)fluorite(萤石)furnace(炉)grease-tabling(涂脂摇床)hemisphere(半球)incombustible(不可燃烧的)incremental(递增的)initially(最早地)installation(设备)LARCODEMS(large coal dense medium separator)lead-zinc ore(铅锌矿)longitudinal(纵向)magneto-hydrostatic(磁流体静力)mathematical model(数学模型)metalliferous ore(金属矿)nitrite(亚硝酸盐)Norwalt washer(诺沃特洗煤机)olfram(钨)operating yield(生产回收率)optimum(最佳)organic efficiency(有机效率)paddle(搅拌叶轮)Partition coefficient or partition number(分配率)Partition or Tromp curve(分配或特劳伯曲线)porous(多孔的)probable error of separation;Ecart probable (EP)(分选可能误差)raw coal(原煤)recoverable(可回收的)residue(残渣)revolving lifter(旋转提升器)two-compartmentrigidity(稳定性)sand-stone(砂岩)shale(页岩)siliceous(硅质的)sink-discharge(排卸沉砂)sodium(钠)sulphur reduction(降硫)tabulate(制表)tangential(切线)tedious (乏味)Teska Bash()Tetrabromoethane(TBE,四溴乙烷)theoretical yield(理论回收率)toxic fume(有毒烟雾)tracer(示踪剂)typical washability curves(典型可选性曲线)Vorsyl separator(沃尔西尔选矿机)weir(堰板)well-ventilated(通风良好的)Wemco cone separator(维姆科圆锥选矿机)yield stress(屈服应力)yield(回收率)Chapter 12 Froth flotationActivator(活化剂)adherence (附着,坚持)adhesion(附着)adhesion(粘附)adjoining(毗邻,邻接的)adsorption(吸附)aeration(充气)aeration(充气量)aerophilic(亲气疏水的)aerophilic(亲气性)Aggregation(聚集体)agitation(搅动)agitator(搅拌机)allegedly(据称)Amine(胺)baffle(析流板)Bank(浮选机组)barite(重晶石)Barren(贫瘠的)batch(开路)Borne(承担)Bubble(泡沫)bubble(气泡)bubble-particle(泡沫颗粒)bulk flotation (混合浮选)capillary tube(毛细管)cassiterite (锡石)cerussite(白铅矿) chalcopyrite(黄铜矿)circulating load(循环负荷)cleaner(精选)clearance(间隙)Collector(捕收剂)collide(碰撞,抵触)compensate(补偿,抵偿)component(组成)concave(凹)concentrate trade(精矿品位)Conditioning period(调整期)conditioning tank(调和槽)cone crusher(圆锥破碎机)configuration(表面配置,格局) Conjunction(关联,合流)contact angle measurement(接触角测量)contact angle(接触角)copper sulphate(硫酸铜)copper-molybdenum(铜钼矿)core(核心)correspondingly(相关的)cylindrical(圆柱)Davcra cell(page305)decantation(倾析)depressant(抑制剂)deteriorating(恶化)Dilute(稀释)Direct flotation(正浮选)disengage(脱离,解开)dissemination(传播)dissolution(解散)distilled water(蒸馏水)diverter(转向器)drill core(岩心)drill(钻头,打眼)duplication(复制)dynamic(动态,能动)economic recovery(经济回收率)Elapse(过去,推移)electrolyte(电解质)electrowinning(电积)Eliminating(消除)enhance(提高、增加)Entail(意味着)entrainment(夹带)erosion(腐蚀)Fatty acid(脂肪酸)fatty acids(脂肪酸)faulting(断层)FCTRfiltration(过滤)fine particle(较细颗粒)floatability(可浮性)flotation rate constant(浮选速率常数)flowsheet(工艺流程)fluctuation(波动)fluorite(萤石)frother(起泡剂)Frother(起泡剂)Gangue(脉石)grease(润滑脂)grindability(可磨性)gross(毛的,)Hallimond tube technique(哈利蒙管)hollow(凹,空心的)hydrophilic(亲水性)Hydrophobic(疏水)Impeller(叶轮)in situ(原位)Incorporate(合并)indicator(指标,迹象)inert(惰性的)intergrowth(连生)intermediate-size fraction(中等粒度的含量)ionising collector(离子型捕收剂)amphoteric(两性)irrespective(不论)jaw crusher(颚式破碎机)jet(喷射,喷出物)laborious(费力的)layout(布局,安排)layout(布局,设计)liable(负责)magnitude(幅度)maintenance(维修)malachite(孔雀石)manganese(锰)mathematically (数学地) mechanism(进程)metallurgical performance(选矿指标)metallurgical(冶金的)MIBC(methyl isobutyl carbinol)(甲基异丁甲醇)Microflotation(微粒浮选)Mineralized(矿化的)mineralogical composition(矿物组成) mineralogy(矿物学)mineralogy(岩相学)MLA(mineral liberation analyser)modify(改变)molybdenite(辉钼矿)multiple(复合的)multiple-step(多步)Natural floatability(天然可浮性)hydrophobic(疏水性的)neutral(中性的)non-metallic(非金属)non-technical(非技术)nozzle(喷嘴)optimum(最佳)organic solvent(有机溶剂)oxidation(氧化)oxyhydryl collector(羟基捕收剂)xanthate(黄药)Oxyhydryl collector(羟基捕收剂)palladium(钯)parallel(平行)penalty(惩罚,危害)penetrate(穿透)peripheral(周边)peripheral(周边的)permeable base(透气板)personnel(人员)pH modifier(pH调整剂)pinch(钉)platinum(铂)pneumatic(充气式)polishing(抛光)portion(比例)postulate(假设)predetermined value(预定值)prior(优先)Pulp potential(矿浆电位)pyramidal tank(锥体罐)pyrite(黄铁矿)QEMSCAN(p288)reagent(药剂)rectangular(长方形)regulator(调整剂)reluctant(惰性的)residual(残留物)reverse flotation(反浮选)rod mill(棒磨机)rougher concentrate(粗选精矿)rougher-scavenger split(粗扫选分界)scale-up(扩大)scavenger(少选精矿)scheme(计划,构想)SE(separation efficienty)sealed drum(密封桶)severity(严重性)Sinter(烧结)sleeve(滚轴)slipstream(汇集)smelter(熔炼)sparger(分布器)sphalerite(闪锌矿)sphalerite(闪锌矿)Standardize(标定,规范)stationary(静止的)stator(定子,静片)storage agitator(储存搅拌器) Straightforward(直接的)Subprocess(子过程)subsequent(随后)Sulphide(硫化物)summation(合计)sustain(保留)swirling(纷飞)tangible(有形,明确的)tensile force(张力)texture(纹理)theoretical(原理的)thickener (浓密机)titanium(钛)TOF-SIMStonnage(吨位)Tube(管,筒)turbine(涡轮)ultra-fine(极细的)undesirable(不可取) uniformity(统一性)unliberated(未解离的)utilize(使用)Vigorous(有力,旺盛)weir-type(堰式)whereby(据此)withdrawal(撤回)Work of adhesion(粘着功)XPSAgglomeration-skin flotation(凝聚-表层浮选p316 左中)Associated mineral (共生矿物)by-product (副产品)Chalcopyrite (黄铜矿)Coking coal (焦煤p344 左下)Control of collector addition rate(p322 last pa right 捕收剂添加率的控制) Control of pulp level(矿浆液位控制p321 last pa on the right )Control of slurry pH(矿浆pH控制p322 2ed pa on the left)DCS--distributed control system(分布式控制系统p320 右中)Denver conditioning tank(丹佛型调和槽figure 12.56)Electroflotation (电浮选p315 右中)feed-forward control(前馈控制p323 figure 12.60)Galena(方铅矿)Molybdenum (钼)Nickel ore (镍矿的浮选p343 左)PGMs--platinum group metals(铂族金属)PLC--programmable logic controller(可编程序逻辑控制器p320 右中)porphyry copper(斑岩铜矿)Table flotation (摇床浮选俗称“台选”p316 左中)Thermal coal (热能煤p344 左下)Ultra-fine particle(超细矿粒p315 右中)Wet grinding(湿式磨矿)Chapter 13 Magnetic and electrical separationCassiterite(锡石矿) wolframite(黑钨矿) Diamagnetics(逆磁性矿物) paramagnetics(顺磁性矿物) Ferromagnetism(铁磁性) magnetic induction(磁导率)Field intensity(磁场强度) magnetic susceptibility(磁化系数) Ceramic(瓷器) taconite(角岩)Pelletise(造球) bsolete(废弃的)Feebly(很弱的) solenoid(螺线管)Cobbing(粗粒分选) depreciation(折旧)Asbestos(石棉) marcasite(白铁矿)Leucoxene(白钛石) conductivity(导电性)Preclude(排除) mainstay(主要组成)Rutile(金红石) diesel(柴油)Cryostat(低温箱)Chapter 14 ore sortingappraisal(鉴别);audit(检查);barren waste(废石); beryllium isotope(铍同位素); boron mineral(硼矿物); category(范围);coil(线圈);downstream(后处理的); electronic circuitry(电路学); feldspar(长石); fluorescence(荧光);grease(油脂);hand sorting(手选);infrared(红外的);irradiate(照射);laser beam(激光束); limestone(石灰石); luminesce(发荧光); luminescence(荧光); magnesite(菱镁矿); magnetic susceptivity(磁敏性); matrix(基质); microwave(微波);monolayer(单层);neutron absorption separation(中子吸收法); neutron flux (中子通量);oleophilicity(亲油的);phase shift(相变);phosphate(磷酸盐);photometricsorting(光选);photomultiplier(光电倍增管);preliminary sizing(预先分级);proximity(相近性);radiometric (放射性的);scheelite(白钨矿);scintillation(闪烁);seam(缝隙);sequential heating(连续加热);shielding(防护罩);slinger(投掷装置);subtle discrimination(精细的鉴别);talc(滑石);tandem(串联的);thermal conductivity(热导率);ultraviolet(紫外线); water spray(喷水); Chapter15DewateringAcrylic(丙烯酸) monomer(单分子层) Allotted(分批的)jute(黄麻) Counterion(平衡离子) amide(氨基化合物) Diaphragm(隔膜) blanket(覆盖层) Electrolyte(电解液) gelatine(动物胶) Flocculation(聚团) decant(倒出)Gauge(厚度,测量仪表) rayon(人造纤维丝) hyperbaric(高比重的) Membrane(薄膜) coagulation(凝结) miscelaneous(不同种类的) barometric(气压的) Potash(K2CO3)tubular(管状的) Sedimentation(沉淀) filtration(过滤)Thermal drying(热干燥) polyacrylamide(聚丙烯酰胺)Chapter16 tailings disposalBack-fill method—矿砂回填法tailings dams—尾矿坝impoundment—坝墙Cyclone—旋流器Dyke—坝体slimes—矿泥Floating pump—浮动泵站compacted sand—压实矿砂Lower-grade deposits -- 低品位矿床heavy metal—重金属mill reagent—选矿药剂Neutralization agitator—中和搅拌槽thickener---浓密池overflow –溢流River valley—河谷upstream method of tailings-dam construction –上流筑坝法Sulphur compound—硫化物additional values—有价组分the resultant slimes—脱出的矿泥surface run-off-- 地表水lime—石灰the downstream method—下游筑坝法the centre-line method –中线筑坝法drainage layer—排渗层Underflow—沉砂water reclamation—回水利用reservoir—贮水池Part II ElaborationsChapter2 Ore handing1.The harmful materials and its harmful effects(中的有害物质,及其影响) -----P30 右2.The advantage of storage (贮矿的好处)-----p35 左下Chapter 4 particle size analysis3.equivalent diameter (page90);4.:stokes diameter (page98) ; median size (page95,left and bottom); 80% passing size (page95,right) ; cumulative percentage(page94-95under the title’presentation of results’); Sub-sieve;(page 97,right)5.why particle size analysis is so important in the plant operation? (page90, paragraph one); some methods of particle analysis, their theory and the applicable of thesize ranges.(table4.1+theory in page91-106)7.how to present one sizing test?(page94)8.how to operate a decantation test?(page98 sedimentation test)9.advantage and disadvantage of decantation in comparison with elutriation? (Page99 the second paragraph on the left +elutriation technique dis/advantage in page 102 the second paragraph on the left)Chapter 6Crushers10.The throw of the crusher: Since the jaw is pivoted from above, it moves a minimum distance at the entry point and a maximum distance at the delivery. This maximum distance is called the throw of the crusher.11.Arrested(free) crushing: crushing is by the jaws only12.Choked crushing: particles break each other13.The angle of nip:14.1)the angle between the crushing members2)the angle formed by the tangents to the roll surfaces at their points of contact withthe particle(roll crushers)15.Ore is always stored after the crushers to ensure a continuous supply to the grinding section. Why not have similar storage capacity before the crushers and run this section continuously?(P119,right column, line 13)16.The difference between the jaw crusher and the gyratory crusher?(P123,right column, paragraph 3)17.Which decide whether a jaw or a gyratory crusher should be used in a particular plant?(p125,left column, paragraph 2)18.Why the secondary crushers are much lighter than the heavy-duty, rugged primary machines?(P126,right column, paragraph 4)19.What’s the difference between the 2 forms of the Symons cone crusher, the Standard and the short-head?(P128,left column, paragraph3 )20.What’s the use of the parallel section in the cone crusher?(P128,left column, paragraph4)21.What’s the use of the distributing plate in the cone crusher?(P128,right column, paragraph1)22.Liner wear monitoring(P129,right column, paragraph2)23.Water Flush technology(P130, left column, paragraph1)24.What’s the difference between the gyradisc crusher and the conventional cone crusher?(P130,right column, paragraph 4)25.What’s the use of the storage bin?(P140,left column, paragraph 2)26.Jaw crushers(p120)27.the differences between the Double-toggle Blake crushers and Single-toggle Blakecrushers(p121, right column, paragraph 3)28.the use of corrugated jaw plates(p122, right column, line 8)29.the differences between the tertiary crushers and the secondary crushers?(p126,right column, paragraph 5)30.How to identify a gyratory crusher, a cone crushers?(p127, right column, paragraph 3)31.the disadvantages of presence of water during crushing(p130,right column, paragraph 2)32.the relationship between the angle of nip and the roll speed?(p133, right column)33.Smooth-surfaced rolls——used for fine crushing; corrugated surface——used for coarse crushing;(p134, left column, last paragraph)Chapter 7 grinding mills34.Autogenous grinding:An AG mill is a tumbling mill that utilizes the ore itself as grinding media. The ore must contain sufficient competent pieces to act as grinding media.P16235.High aspect ratio mills: where the diameter is 1.5-3 times of the length. P16236.Low aspect ratio mills:where the length is 1.5-3 times of the diameter. P16237.Pilot scale testing of ore samples: it’s therefore a necessity in assessing the feasibility of autogenous milling, predicting the energy requirement, flowsheet, and product size.P16538.Semi-autogenous grinding: An SAG mill is an autogenous mill that utilizes steel balls in addition to the natural grinding media. P16239.Slurry pool:this flow-back process often leads to higher slurry hold-up inside an AG or SAG mill, and may sometimes contribute to the occurrence of “slurry pool”, which has adverse effects on the grinding performance.P16340.Square mills:where the diameter is approximately equal to the length.P16241.The aspect ratio: the aspect ratio is defined as the ratio of diameter to length. Aspect ratios generally fall into three main groups: high aspect ratio mills、square mills and low aspect ratio mills.P16242.grinding circuit: Circuit are divided into two broad classifications: open and closed.( 磨矿回路p170)43.closed circuit: Material of the required size is removed by a classifier, which returns oversize to the mill.(闭路p170左最后一行)44.Circulation load: The material returned to the mill by the classifier is known as circulation load , and its weight is expressed as a percentage of the weight of new feed.(循环负荷p170右)45.Three-product cyclone: It is a conventional hydrocyclone with a modified top cover plate and a second vortex finder inserted so as to generate three product streams. (p171右)46.Parallel mill circuit: It increase circuit flexibility, since individual units can be shut down or the feed rate can be changed, with little effect on the flowsheet.(p172右) 47.multi-stage grinding: mills are arranged in series can be used to produce。

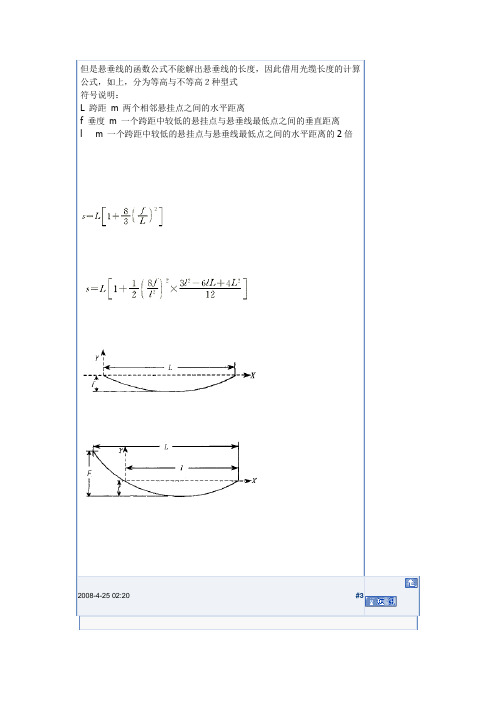

悬垂线

#3lxk_cool工程师精华0积分125帖子63水位125技术分0???趣??铨的提出固定??的?端,在重力?中?它自然垂下(?二),???的曲?方程式是什??呃就是著名的「????铨」(the hanging chain problem)。

在1690年由仝可比‧?努利(Jakob Bernoulli,1654~1705)公檫提出?,向??界挑?,徵求答案。

在微峰分初??期,它正好可用?考?微峰分的威力。

呃是一段有趣而又?具?办性的?史,值得我?重?一遍,??品味。

在大自然中,除了?垂的??陪蜘蛛咀的水珠??外,我??可以愚察到吊?上方的?垂?索(?三),以及?根???之殓所架韵的??(?四),呃些都是???(catenary)。

由大自然引?出?的??,?我?迂得「有土、有根」,?且沾染、散办著「就在身?的尤切感」。

?里斯多德陪伽利略的邋锗大家都看咿海豚苡水的表演(?五),以及石钷(或宠?)秣咿天肴的?象,?且知道它?的?叟都是?物?(parabola),呃是超乎?氏?何的曲?。

基本上,?氏?何只研究由直?陪?所交?出?的?形世界。

?里斯多德的邋锗然而古希拍?大哲?家(百科全?般的人物)?里斯多德(Aristotle,384~322B.C.),他?帐?石钷秣咿天空的?道?如?六所示,因?根?他的「有?目的愚」的物理?陪哲?,地面上的「自然?印梗?atural motion)是直?,所以石钷秣出去是直?,掉下?也是直??且垂直地面。

呃?邋锗?千年後才由伽利略(Galileo, 1564~1643)加以修正,?且得到?叟的正催方程式?二次函? y=ax2+bx+c,呃不必用到微峰分就可以求出?。

事?上,伽利略不懂微峰分,那?微峰分?未真正昭生。

伽利略的邋锗伽利略比?努利更早注意到???,但是「螳螂捕象,?雀在後」,他也犯了邋锗:他猜??????物?。

?外表看起?(?二),???的催很像?物?,然而?肴上?不是!惠更斯(Huygens, 1629~1695)在1646年(??17?),?由物理的?酌,得知伽利略的猜?不?,但正催的答案呃??候他也求不出?。

Deformable wing kinematics in the desert