Task type as a moderator of positive- negative feedback effects on motivation

东师《英语课程与教学论16秋在线作业3

B. conversion

C. affixation

D. backformation

正确答案:

9. The first of the “natural methods”is ().

A. Direct Method

B. Grammar-translation Method

C. the Audio-lingual Method

A. Describing

B. predicting

C. brainstoring

正确答案:

16. Cognitive and interactional patterns cannot affect the way in which students?

A. perceive

B. remember

C. think

A. homework

B. communication task

C. exercise

D. listening activity

正确答案:

12. ()research must be analytic

A. experimental

B. descriptive

C. Action research

D. A case study

2. ()involves teachers identifying issues and problems relevant to their own classes.

A. Literature review

B. Questionnaire

C. Action research

D. lassroom observation

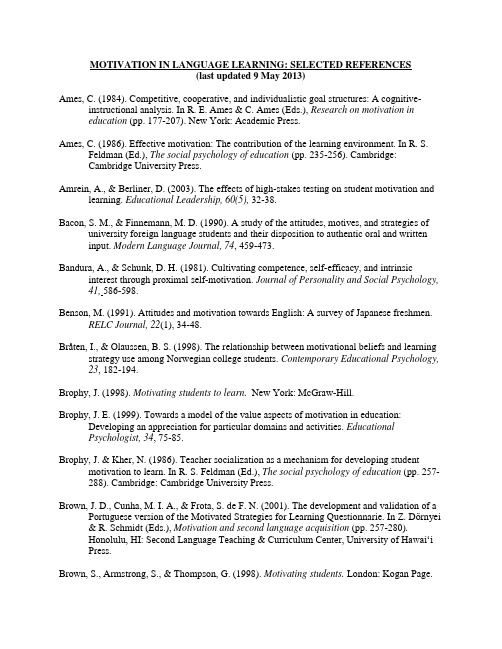

motivation in language learning tesol internation

MOTIVATION IN LANGUAGE LEARNING: SELECTED REFERENCES(last updated 9 May 2013)Ames, C. (1984). Competitive, cooperative, and individualistic goal structures: A cognitive-instructional analysis. In R. E. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation ineducation (pp. 177-207). New York: Academic Press.Ames, C. (1986). Effective motivation: The contribution of the learning environment. In R. S.Feldman (Ed.), The social psychology of education (pp. 235-256). Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.Amrein, A., & Berliner, D. (2003). The effects of high-stakes testing on student motivation and learning. Educational Leadership, 60(5), 32-38.Bacon, S. M., & Finnemann, M. D. (1990). A study of the attitudes, motives, and strategies of university foreign language students and their disposition to authentic oral and writteninput. Modern Language Journal, 74, 459-473.Bandura, A., & Schunk, D. H. (1981). Cultivating competence, self-efficacy, and intrinsic interest through proximal self-motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 586-598.Benson, M. (1991). Attitudes and motivation towards English: A survey of Japanese freshmen.RELC Journal, 22(1), 34-48.Bråten, I., & Olaussen, B. S. (1998). The relationship between motivational beliefs and learning strategy use among Norwegian college students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23, 182-194.Brophy, J. (1998). Motivating students to learn. New York: McGraw-Hill.Brophy, J. E. (1999). Towards a model of the value aspects of motivation in education: Developing an appreciation for particular domains and activities. EducationalPsychologist, 34, 75-85.Brophy, J. & Kher, N. (1986). Teacher socialization as a mechanism for developing student motivation to learn. In R. S. Feldman (Ed.), The social psychology of education (pp. 257-288). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Brown, J. D., Cunha, M. I. A., & Frota, S. de F. N. (2001). The development and validation of a Portuguese version of the Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnarie. In Z. Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 257-280).Honolulu, HI: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawai‘i Press.Brown, S., Armstrong, S., & Thompson, G. (1998). Motivating students. London: Kogan Page.Chambers, G. (1999). Motivating language learners. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. Cheng, H-F., & Dörnyei, Z. (2007). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in language learning and teaching, 1,153-174.Cohen, M., & Dörnyei, Z. (2002). Focus on the language learner: Motivation, styles and strategies. In N. Schmidt (Ed.), An introduction to applied linguistics (pp. 170-190).London, UK: Arnold.Cooper, H., & Tom, D. Y. H. 1984. SES and ethnic differences in achievement motivation. In R.E. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Motivation in education (pp. 209-242). New York:Academic Press.Cranmer, D. (1996). Motivating high level learners. Harlow, UK: Longman.Crookes, G., & Schmidt, R. W. (1991). Motivation: Re-opening the research agenda. Language Learning, 41, 469-512.Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Nakamura, J. (1989). The dynamics of intrinsic motivation: A study of adolescents. In R. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Handbook of motivation theory and research, Vol. 3: Goals and cognitions (pp. 45–71). New York, NY: Academic Press.Csizér, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). Language learners’ motivational profiles and their motivated learning behavior. Language Learning, 55, 613-659.Csizér, K., Kormos, J., & Sarkadi, Á. (2010). The dynamics of language learning attitudes and motivation: Lessons from an interview study of dyslexic language learners. ModernLanguage Journal, 94(3), 470-487.deCharms, R. (1984). Motivation enhancement in educational settings. In R. E. Ames & C.Ames (Eds.), Motivation in education (pp. 275-310). New York: Academic Press. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum.Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In R. A. Dienstbier (Ed.), Perspectives on motivation: Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1990 (pp. 237-288). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.Deci, E. L., Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). Motivation and education: The self-determination perspective. Educational Psychologist, 26(3 & 4), 325-346.De Volder, M. L., & Lens, W. (1982). Academic achievement and future time perspective as a cognitive-motivational concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 20-33Dörnyei, Z. (1990). Conceptualizing motivation in foreign language learning. Language Learning, 40, 45-78.Dörnyei, Z. (1994). Motivation and motivating in the foreign language classroom. Modern Language Journal,78, 273-284.Dörnyei, Z. (1998). Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Language Teaching, 31, 117-135.Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Motivational strategies in the language classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.Dörnyei, Z. (2001). Teaching and researching motivation. Harlow, UK: Longman.Dörnyei, Z. (2002). The motivational basis of language learning tasks. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Individual differences and instructed language learning (pp. 137-158). Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.Dörnyei, Z. (2003). Attitudes, orientations, and motivations in language learning: Advances in theory, research, and applications. Language Learning, 53(Supplement 1), 3-32.Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Creating a motivating classroom environment. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International Handbook of English Language Teaching (Vol. 2) (pp. 719-731).New York, NY: Springer.Dörnyei, Z. (2008). New ways of motivating foreign language learners: Generating vision. Links, 38(Winter), 3-4.Dörnyei, Z. (2009). The L2 motivational self system. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 9-42).Tonawanda, NY: MultilingualMatters.Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (1998). Ten commandments for motivating language learners: Results of an empirical study. Language Teaching Research, 2, 203-229.Dörnyei, Z., & Csizér, K. (2002). Some dynamics of language attitudes and motivation: Results of a longitudinal nationwide survey. Applied Linguistics, 23, 421-462.Dörnyei, Z., & K. Csizér. (2002). Some dynamics of language attitudes and motivation: Results of a longitudinal nationwide survey. Applied Linguistics, 23, 421–462.Dörnyei, Z., Csizér, K., & Németh, N. (2006). Motivation, language attitudes, and globalization:A Hungarian perspective. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.Dörnyei, Z., & Ottó, I. (1998). Motivation in action: A process model of L2 motivation. Working Papers in Applied Linguistics, 4, 43-69.Dörnyei, Z., & Schmidt, R. (Eds.). (2001). Motivation and second language acquisition.Honolulu: National Foreign Language Resource Center/ University of Hawai'i Press.Dörnyei, Z., & Skehan, P. (2003). Individual differences in second language learning. In C. J.Doughty & M. H. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 589-630). Malden, MA: Blackwell.Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41, 1040-1048.Ehrman, M. (1996). An exploration of adult language learner motivation, self-efficacy, and anxiety. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation: Pathways to the new century (pp. 81-103). Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.Gao, Y., Zhao, Y., Cheng, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2004). Motivation types of Chinese university undergraduates. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 45-64.Gardner, R. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitude and motivation. London, UK: Edward Arnold.Gardner, R. (2001). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. In Z. Dörnyei & R.Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 1-19). Honolulu, HI:University of Hawai’i Press.Gardner, R. C. (2000). Correlation, causation, motivation, and second language acquisition.Canadian Psychology, 41, 10-24.Gardner, R. C. (2001). Integrative motivation: Past, present and future. Retrieved from ://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/GardnerPublicLecture1.pdfGardner, R. (2001). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. In Z. Dörnyei & R.Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 1-19). Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.Gardner, R. C. (2005). Integrative motivation and second language acquisition. Retrieved from ://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/caaltalk5final.pdfGardner, R. C. (2009). Gardner and Lambert (1959): Fifty years and counting. Retrieved from ://publish.uwo.ca/~gardner/docs/CAALOttawa2009talkc.pdfGardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1959). Motivational variables in second language acquisition.Canadian Journal of Psychology, 13, 266-272.Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House.Gardner, R. C., Masgoret, A.-M., Tennant, J., & Mihic, L. (2004). Integrative motivation: Changes during a year-long intermediate-level language course. Language Learning, 54, 1-34.Gardner, R. C., & Smythe, P. C. (1981). On the development of the attitude/ motivation test battery. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 37, 510-525.Gardner, R. C., & Tremblay, P. F. (1994). On motivation, research agendas, and theoretical frameworks. The Modern Language Journal, 78, 359-368.Grabe, W. (2009). Motivation and reading. In W. Grabe (Ed.), Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice (pp. 175-193). New York, NY: Cambridge UniversityPress.Graham, S. (1994). Classroom motivation from an attitudinal perspective. In H. F. J. O'Neil and M. Drillings (Eds.), Motivation: Theory and research (pp. 31-48). Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum.Guilloteaux, M. J., & Dörnyei, Z. (2008). Motivating language learners: A classroom-oriented investigation of the effects of motivational strategies on student motivation. TESOLQuarterly, 42, 55-77.Hadfield, J. (2013). A second self: Translating motivation theory into practice. In T. Pattison (Ed.), IATEFL 2012: Glasgow Conference Selections (pp. 44-47). Canterbury, UK:IATEFL.Hao, M., Liu, M., & Hao, R. (2004). An empirical study on anxiety and motivation in English asa Foreign Language. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 89-104.Hara, C., & Sarver, W. T. (2010). Magic in ESL: An observation of student motivation in an ESL class. In G. Park, H. P. Widodo, & A. Cirocki (Eds.), Observation of teaching:Bridging theory and practice through research on teaching (pp. 141-153). Munich,Germany: LINCOM EUROPA.Hashimoto, Y. (2002). Motivation and willingness to communicate as predictors of reported L2 use: The Japanese ESL context. Retrieved from :///sls/uhwpesl/20(2)/Hashimoto.pdf.Hawkins, J. N. (1994). Issues of motivation in Asian education. In H. F. O’Neill & M. Drillings (Eds.), Motivation—theory and research (pp. 101-115). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Hsieh, P. (2008). Why are college foreign language students' self-efficacy, attitude, and motivation so different? International Education, 38(1), 76-94.Huang, S. (2010). Convergent vs. divergent assessment: Impact on college EFL students’ motivation and self-regulated learning strategies. Language Testing, 28(2), 251-270.Keller, J. M. (1983). Motivational design of instruction. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional design theories and models (pp. 386-433). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Kim, S. (2009). Questioning the stability of foreign language classroom anxiety and motivation across different classroom contexts. Foreign Language Annals, 42(1), 138-157. Komiyama, R. (2009). CAR: A means for motivating students to read. English Teaching Forum, 47(3), 32-37.Kondo-Brown, K. (2001). Bilingual heritage students’ language contact and motivation. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 433-460).Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.Koromilas, K. (2011). Obligation and motivation. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 44, 12-20.Lamb, M. (2004). Integrative motivation in a globalizing world. System, 32, 3-19.Lamb, T. (2009). Controlling learning: Learners’ voices and relationships between motivation and learner autonomy. In R. Pemberton, S. Toogood, & A. Barfield (Eds.), Maintaining control: Autonomy and language learning (pp. 67-86). Hong Kong: Hong KongUniversity Press.Lau, K.-l., & Chan, D. W. (2003). Reading strategy use and motivation among Chinese good and poor readers in Hong Kong. Journal of Research in Reading, 26, 177-190.Lepper, M. R. (1983). Extrinsic reward and intrinsic motivation: implications for the classroom.In J. M. Levine & M. C. Wang (eds.), Teacher and student perceptions: implications for learning (pp. 281-317). Hillsdale, NJ; Erlbaum.Li, J. (2009). Motivational force and imagined community in ‘Crazy English.’ In J. Lo Bianco, J.Orton, & Y. Gao (Eds.), China and English: Globalisation and the dilemmas of identity(pp. 211-223). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.Lopez., F. (2010).Identity and motivation among Hispanic ELLs. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 18(16), 1-29.MacIntyre, P. D. (2002). Motivation, anxiety and emotion in second language acquisition. In P.Robinson (Ed.), Individual differences and instructed language learning (pp. 45-68).Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.MacIntyre, P. D., MacMaster, K., & Baker, S. C. (2001). The convergence of multiple models of motivation for second language learning: Gardner, Pintrich, Kuhl, and McCroskey. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and language acquisition (pp. 461-492).Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.Maehr, M. L. & Archer, J. (1987). Motivation and school achievement. In L. G. Katz (ed.), Current topics in early childhood education (pp. 85-107). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.Manderlink, G., & Harackiewicz, J. M. 1984. Proximal versus distal goal setting and intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 918-928.Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224-253.Maslow, A. H. (1970). Motivation and personality. New York, NY: Harper & Row.McCombs, B. L. (1984). Processes and skills underlying continued motivation to learn.Educational Psychologist, 19(4), 199-218.McCombs, B. L. (1988). Motivational skills training: combining metacognitive, cognitive, and affective learning strategies. In C. E. Weinstein, E. T. Goetz & P. A. Alexander (Eds.),Learning and study strategies (pp.141-169). New York: Academic Press.McCombs, B. L. (1994). Strategies for assessing and enhancing motivation: keys to promoting self-regulated learning and performance. In H. F. O’Neill & M. Drillings (Eds.),Motivation: theory and research (pp. 49-69). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.McCombs, B. L., & Whisler, J. S. (1997). The learner-centered classroom and school: Strategies for increasing student motivation and achievement. San Francisco. CA:Jossey-Bass.McCrossan, L. (2011). Progress, motivation and high-level learners. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 44, 6-12.Melvin, B. S., & Stout, D. S. (1987). Motivating language learners through authentic materials.In W. Rivers (Ed.), Interactive language teaching (pp. 44–56). New York, NY:Cambridge University Press.Midraj, S., Midraj, J., O’Neil, G., Sellami, A., & El-Temtamy, O. (2007). UAE grade 12 students’ motivation & language learning. In S. Midraj, A. Jendli, & A. Sellami (Eds.), Research in ELT contexts (pp. 47-62). Dubai: TESOL Arabia.Molden, D. C., & Dweck, C. S. (2000). Meaning and motivation. In C. Sansone & J.Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimalmotivation and performance (pp. 131-159). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.Mori, S. (2002). Redefining motivation to read in a foreign language. Reading in a Foreign Language, 14, 91-110.Noels, K. A., Clément, R., & Pelletier, L. G. (1999). Perceptions of teachers’ communicative style and students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.Modern Language Journal,83, 23-34.Noels, K. A., Pelletier, L. G., Clément, R., & Vallerand, R. J. (2000). Why are you learning a second language?: Motivational orientations and self-determination theory. LanguageLearning, 50, 57-85.Oxford, R. L. (Ed.). (1996). Language learning motivation: pathways to the new century.Hono lulu: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawai’i.Oxford, R., & Shearin, J. (1994). Language learning motivation: Expanding the theoretical framework. Modern Language Journal, 78, 12-28.Papadimitriou, A. D. (2011). The impact of an extensive reading programme on vocabulary development and motivation. Cambridge ESOL Research Notes, 44, 39-47.Paris, S. C., & Turner, J. C. (1994). Situated motivation. In P. R. Pintrich, D. R. Brown, & C. E.Weinstein (Eds.), Student motivation, cognition, and learning (pp. 213-237). Hillsdale,NJ: Erlbaum.Peacock, M. (1997). The effect of authentic materials on the motivation of EFL learners. ELT Journal, 51(2), 144-156.Pedraza, P., & Ayala, J. (1996). Motivation as an emergent issue in an after-school program in El Barrio. In L. Schauble & R. Glaser (Eds.), Innovations in learning (pp. 75-91). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.Pintrich, P. R. (1999). The role of motivation in promoting and sustaining self-regulated learning.International Journal of Educational Research, 31(6), 459-470.Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of educational psychology, 82(1), 33.Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (1996). Motivation in education: Theory, research and applications. Englewood Cliffs: NJ: Prentice-Hall.Ramage, K. (1991). Motivational factors and persistence in second language learning. Language Learning, 40(2), 189-219.Rueda, R., & Moll, L. (1994). A sociocultural perspective on motivation. In H. F. O’Neill & M.Drillings (Eds.), Motivation: theory and research (pp. 117-137). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology,25, 54-67.Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78. Schmidt, R., Boraie, D., & Kassabgy, O. (1996). Foreign language motivation: Internal structure and external connections. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation:Pathways to the new century (pp. 9-70). Honolulu: Second Language Teaching &Curriculum Center, University of Hawaii Press.Schutz, P. A. (1994). Goals as the transaction point between motivation and cognition. In P. R.Pintrich, D. R. Brown, & C. E. Weinstein (Eds.), Student motivation, cognition, andlearning (pp. 135-156). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.Scott, K. (2006). Gender differences in motivation to learn French. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 62, 401-422.Syed, Z. (2001). Notions of self in foreign language learning: A qualitative analysis. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 127-147).Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaii Press.Schmidt, R., Boraie, D., & Kassabgy, O. (1996). Foreign language motivation: Internal structure and external connections. In R. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning motivation: Pathways to the new century (pp. 9-70). Honolulu, HI: Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center, University of Hawaii Press.Scott, K. (2006). Gender differences in motivation to learn French. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 62, 401-422.Sisamakis, M. (2010). The motivational potential of the European language portfolio. In B.O’Rourke & L. Carson (Eds.), Language learner autonomy: Policy, curriculum,classroom (pp. 351-371). Oxford, UK: Peter Lang.Smith, K. (2006). Motivating students through assessment. In R. Wilkinson, V. Zegers, & C. van Leeuwen (Eds.), Bridging the assessment gap in English-medium higher education (pp.109-121). Nijmegen, The Netherlands: AKS –Verlag.St. John, J. (2007). Motivation: The teachers’ perspective. In S. Midraj, A. Jendli, & A. Sellami (Eds.), Research in ELT contexts (pp. 63-84). Dubai: TESOL Arabia.Syed, Z. (2001). Notions of self in foreign language learning: a qualitative analysis. In Z.Dörnyei & R. Schmidt, (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 127-148).Honolulu: National Foreign Language Resource Center/ University of Hawai'iPress.Ushioda, E. (2003). Motivation as a socially mediated process. In D. Little, J. Ridley, & E.Ushioda (Eds.), Learner autonomy in the language classroom (pp. 90-102). Dublin,Ireland: Authentik.Ushioda, E. (2008). Motivation and good language learners. In C. Griffiths (Ed.), Lessons from good language learners (pp. 19-34). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Ushioda, E. (2009). A person-in-context relational view of emergent motivation, self and identity.In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.), Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp.215-228). Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters.Ushioda, E. (2012). Motivation. In A. Burns & J. C. Richards (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to pedagogy and practice in language teahcing (pp. 77-85). Cambridge, UK: CambridgeUniversity Press.Verhoeven, L., & Snow, C. E. (Eds.). (2001). Literacy and motivation: Reading engagement in individuals and groups. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.Wachob, P. (2006). Methods and materials for motivation and learner autonomy. Reflections on English Language Teaching, 5(1), 93-122.Walker, C. J., & Quinn, J. W. (1996). Fostering instructional vitality and motivation. In R. J.Menges and associates, Teaching on solid ground (pp. 315-336). San Francisco, SF:Jossey-Bass.Warden, C. A., & Lin, H. J. (2000). Existence of integrative motivation in an Asian EFL setting.Foreign Language Annals, 33, 535-547.Weiner, B. (1984). Principles for a theory of student motivation and their application within an attributional framework. In R. Ames & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation ineducation (pp. 15-38). New York: Academic Press.Weiner, B. (1992). Human motivation: Metaphors, theories and research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.Weiner, B. (1994). Integrating social and personal theories of achievement motivation. Review of Educational Research, 64, 557-573.Williams, M., Burden, R., & Lanvers, U. (2002). French is the language of love and stuff: Student perceptions of issues related to motivation in learning a foreign language.British Educational Research Journal, 28, 503–528.Wlodkowski, R. J. (1985). Enhancing adult motivation to learn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Wu, X. (2003). Intrinsic motivation and young language learners: The impact of the classroom environment. System, 31, 501-517.Xu, H., & Jiang, X. (2004). Achievement motivation, attributional beliefs, and EFL learning strategy use in China. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 14, 65-87.Yung, K. W. H. (2103). Bridging the gap: Motivation in year one EAP classrooms. Hong Kong Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14(2), 83-95.。

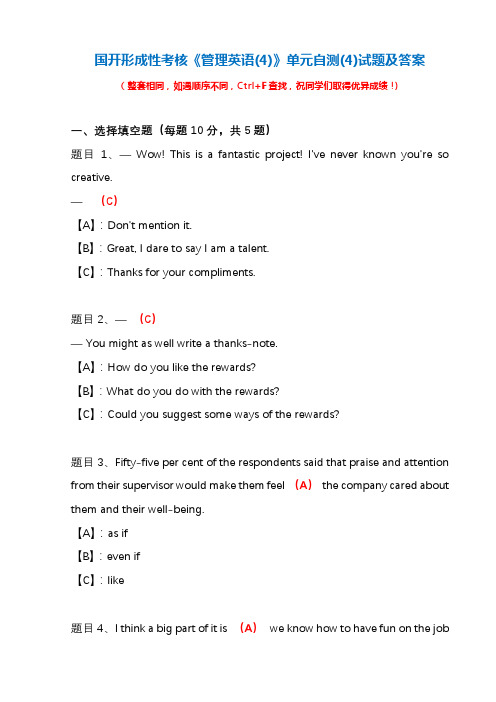

国开形成性考核《管理英语(4)》单元自测(4)试题及答案

国开形成性考核《管理英语(4)》单元自测(4)试题及答案(整套相同,如遇顺序不同,Ctrl+F查找,祝同学们取得优异成绩!)一、选择填空题(每题10分,共5题)题目1、—Wow! This is a fantastic project! I've never known you're so creative.—(C)【A】:Don't mention it.【B】:Great, I dare to say I am a talent.【C】:Thanks for your compliments.题目2、—(C)— You might as well write a thanks-note.【A】:How do you like the rewards?【B】:What do you do with the rewards?【C】:Could you suggest some ways of the rewards?题目3、Fifty-five per cent of the respondents said that praise and attention from their supervisor would make them feel (A)the company cared about them and their well-being.【A】:as if【B】:even if【C】:like题目4、I think a big part of it is (A)we know how to have fun on the job【B】:which【C】:why题目5、Self-esteem needs might include the (A)from a workplace. 【A】:rewards【B】:rewarded【C】:rewarded题目6、— You'd better not push yourself too hard. You can ask the team and listen.—(A)【A】:You are right.【B】:No, we can't do that.【C】:I think it will kill our time.题目7、— Do you mind if I use vouchers to spend in a restaurant? —(B)【A】:Yes, please.【B】:Not at all. Go ahead.【C】:No, thank you.题目8、All the team members tried their best. We lost the game, (A). 【A】:however【B】:therefore题目9、(C)clearly communicate with and actively listen to employees is essential to improve their performance.【A】:Be able to【B】:Being able【C】:Being able to题目10、(C)the job, employers don't want to hire people who are difficult to get along with.【A】:Despite of【B】:Regardless【C】:Regardless of题目11、—Can I get you a couple of tea?—(A).【A】:That's very nice of you【B】:With pleasure【C】:You can, please题目12、— Do you mind if I use vouchers to spend in a restaurant? —(B)【A】:Yes, please.【B】:Not at all. Go ahead.【C】:No, thank you.题目13、Companies are (B)interested in your soft skills (B)they are in your hard skills.【A】:so… that…【B】:as…as…【C】:not…until…题目14、An appreciated gift and the gesture of providing it will (B)your coworker's day.【A】:look up【B】:light up【C】:lift to题目15、Learning new things has always been a great (A)for me. 【A】:motivator【B】:motivate【C】:motivation题目16、The leader (C)at creating opportunities to provide rewards, recognition and thanks to his or her staff.【A】:exceeds【B】:excellent【C】:excels题目17二、阅读理解:根据文章内容,完成选择题(共50分)。

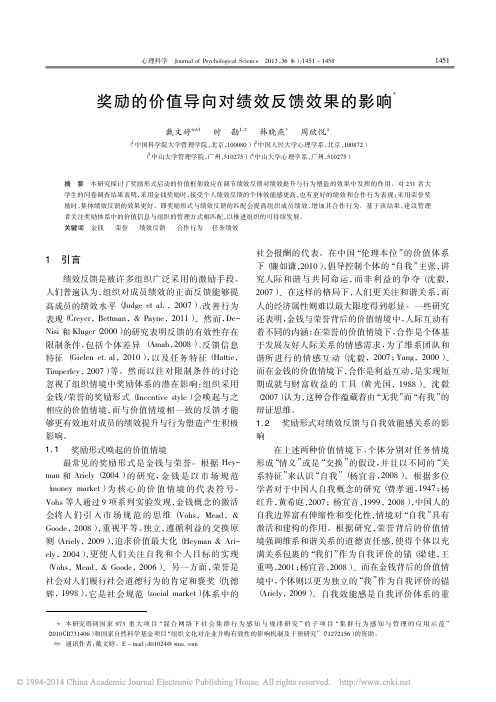

奖励的价值导向对绩效反馈效果的影响_戴文婷_时勘_韩晓燕_周欣悦

Journal of Psychological Science 2013 , 36 ( 6 ) : 1451 - 1458

1451

奖励的价值导向对绩效反馈效果的影响

* 戴文婷*

1

*

时

勘

1, 2

韩晓燕

3

周欣悦

4

( 1 中国科学院大学管理学院 , 100080 ) ( 2 中国人民大学心理学系, 100872 ) 北京, 北京, ( 3 中山大学管理学院, 510275 ) ( 4 中山大学心理学系, 510275 ) 广州, 广州,

1

引言

的价值体系 社会报酬的代表。 在中国“伦理本位 ” 2010 ) , 下( 廉如谦, 倡导控制个体的“自我 ” 主张, 讲 而 非 利 益 的 争 夺 ( 沈 毅, 究人际和 谐 与 共 同 命 运, 2007 ) 。在这样的格局下, 人们更关注和谐关系, 而 人的经济属性则难以最大限度得到彰显 。 一些研究 还表明, 金钱与荣誉背后的价值情境中, 人际互动有 着不同的内涵: 在荣誉的价值情境下, 合作是个体基 于发展友好人际关系的情感需求, 为了维系团队和 谐所进 行 的 情 感 互 动 ( 沈 毅,2007 ; Yang,2000 ) 。 而在金钱的价值情境下, 合作是利益互动, 是实现短 期成就与财 富 收 益 的 工 具 ( 黄 光 国,1988 ) 。 沈 毅 ( 2007 ) 认为, “无我” 这种合作蕴藏着由 而“有我 ” 的 辩证思维。 1. 2 奖励形式对绩效反馈与自我效能感关系的影 响 在上述两种价值情境下, 个体分别对任务情境 “情义” 形成 或是“交换 ” 的假设, 并且以不同的“关 ( 杨宜音, 2008 ) 。 根据多位 系特征” 来认识“自我 ” 1947 ; 杨 学者对于中国人自我概念的研究 ( 费孝通, 2007 ; 杨宜音, 1999 , 2008 ) , 红升, 黄希庭, 中国人的 自我边界富有伸缩性和变化性, 情境对“自我 ” 具有 激活和建构的作用。 根据研究, 荣誉背后的价值情 境强调维系和谐关系的道德责任感, 使得个体以充 满关系包裹的“我们 ” 作为自我评价的锚 ( 梁建, 王 2001 ; 杨宜音, 2008 ) 。而在金钱背后的价值情 重鸣, 境中, 个体则以更为独立的“我 ” 作为自我评价的锚 ( Ariely, 2009 ) 。 自我效能感是自我评价体系的重

深大成教UOOC工作中的心里与行为-2

一、单选题(共30.00分)根据庞迪(Pondy)的冲突五阶段模型,()是人们开始认识到与其他成员之间存在着冲突,但是并不意味着必然出现个人冲突。

A.潜在的冲突B.感知的冲突C.情感的冲突D.显性的冲突满分:1.00 分得分:0分你的答案:A正确答案:B教师评语:--以下属于双向沟通的优点的是。

()A.速度快B.有序C.灵活性强D.发讯者不被挑战满分:1.00 分得分:1.00分你的答案:C正确答案:C教师评语:--为了密切个人努力—工作绩效之间的联系,组织的正确作法是。

()A.提供高绩效员工受奖实例B.准确评估工作绩效C.表明只有达成业绩才会受奖D.提供员工成功完成任务实例满分:1.00 分得分:1.00分你的答案:D正确答案:D教师评语:--群体成员共同认为应当遵守的各种行为标准是。

()A.价值观B.角色C.规范D.地位满分:1.00 分得分:0分你的答案:A正确答案:C教师评语:--在一个企业里,有一个高管辞职,去了竞争对手公司,过不多久,又有一些中层和基层的干部辞职,老板很生气,认定是那个高管来挖墙脚。

实际上,他们之间可能毫无关系。

老板之所以会这样认为,说明受到知觉组织规律中何种规律的影响()。

A.连续性规律B.接近性规律C.封闭性规律D.境联效应满分:1.00 分得分:0分你的答案:D正确答案:B教师评语:--通过领导者个人的素质对领导有效性进行研究的理论称为领导的( )理论。

A.特质B.C.权变D.替代满分:1.00 分得分:1.00分你的答案:A正确答案:A教师评语:--主题统觉测试(TAT)是。

()A.让被试填写问卷B.完成不完整的句子C.对被试的生理反应进行测量D.请被试描述含义模糊的图片引发的想象满分:1.00 分得分:1.00分你的答案:D正确答案:D教师评语:--当两个人有矛盾时,一个人跳槽到另一家企业的冲突处理策略是()。

A.竞争B.协作C.回避D.妥协满分:1.00 分得分:1.00分你的答案:C正确答案:C教师评语:--胖东来的管理者用来分析顾客翻检蔬果堆头时运用的管理技能是()。

谦逊型领导对员工反馈规避行为的影响--学习目标导向与宽容氛围的作用

当今的商业世 界 不 仅 更 具 风 险,而 且 更 加 不 稳定、复 杂 和 模 糊,在 此 背 景 下,反 馈 行 为 管 理 成 为人力资源管理领域的一个重要课题。梳理文献 后发现,目前的研 究 对 反 馈 寻 求 行 为 给 予 了 充 分 的关注,但是 Moss指出,员工 的 反 馈 管 理 行 为 不 仅是反馈寻求行 为,还 包 括 反 馈 缓 和 行 为 和 反 馈 规避行 为 。 [1] 其 中 反 馈 规 避 作 为 一 种 消 极 的 行 为,不 利 于 员 工 及 时 发 现 问 题 和 改 进 工 作,因 此, 哪些因素会影响员工的反馈规避行为是一个很值 得研究的问 题。作 为 反 馈 规 避 行 为 的 主 体,员 工 自身因素显然会 影 响 反 馈 规 避 行 为,如 员 工 的 核 心 自 我 评 价 等 ;作 为 反 馈 规 避 行 为 的 客 体 ,领 导 因 素 也 可 能 影 响 反 馈 规 避 行 为 ,如 辱 虐 管 理 等 ;作 为 组织中的个体,员 工 的 行 为 也 会 受 到 组 织 因 素 的 影 响 ,如 组 织 发 展 性 绩 效 考 核 导 向 等 。 基 于 此 ,本 研 究 从 员 工 、领 导 和 组 织 三 个 层 面 ,综 合 分 析 员 工 反馈规避行为。

43

为倾向必然 也 会 受 到 所 处 环 境 的 影 响 。 [4] 因 此, 组织能否容忍成 员 的 失 败 或 错 误,也 是 影 响 员 工 在 绩 效 不 佳 时 ,逃 避 来 自 领 导 的 反 馈 的 重 要 因 素 。 通过梳理文献发 现,目 前 关 于 团 队 宽 容 氛 围 的 研 究主要集中于团 队 绩 效、学 习 行 为 和 组 织 公 民 行 为。虽然邓志华等认为团队宽容氛围可以调节谦 卑领导与团 队 跨 界 行 为 之 间 的 关 系[5],但 是 正 如 上文所述,“谦卑型 领 导”与 “谦 逊 型 领 导”并 不 是 同一概念,所以本 研 究 认 为 团 队 宽 容 氛 围 也 可 以 调节谦逊型领导与反馈规避行为之间的关系。具 体而言,团队倡导 宽 容 能 够 促 使 团 队 成 员 对 工 作 中的差错及失败 保 持 客 观 态 度,而 且 可 能 带 来 新 知识 。 [6] 相反,在不够宽容的团队氛围中,团队 成 员之间相互 推 诿,可 能 会 带 来 情 绪 耗 竭。基 于 这 两 种 不 同 的 情 境 ,当 宽 容 氛 围 作 为 边 界 条 件 时 ,谦 逊型领导通过员工学习目标导向进而影响反馈规 避行为的作用大小可能不同。

吉林大学网上作业-劳动关系课程-判断题答案

作业>>判断题1:企业组织中政策改革的步骤表现为需要意识、解冻、变革和再冻结。

()正确错误2:影响力是一个人在于他人的交往中,监督他人的心理与行为的能力。

()正确错误3:现代企业管理的特点是强调以效益为中心的管理。

()正确错误4:人事改革包括工作扩大化、工作丰富化、自治工作小群体和转换工作制等。

()正确错误5:企业的管理职能包括计划、组织、指挥、协调、控制和用人。

()正确错误6:目标管理迫使人们事先制订计划。

()正确错误7:能力是个人对现实的稳定的态度和习惯了的行为方式。

()正确错误8:目标管理忽视职工的个人差异,不允许每个人各自设置自己的目标。

----------专业最好文档,专业为你服务,急你所急,供你所需-------------()正确错误9:冲突有人际间、群体间和组织之间的冲突。

()正确错误10:传统型组织的学习内容包括建立共同愿景、自我超越、改善心智模式、团队学习和系统思考。

()正确错误11:时间的特征是可变性、可存储性和可替代性。

()正确错误12:心智模式是在长期的生活、学习、工作中形成的,并以价值观与世界观为基础。

()正确错误13:现代五项管理技能的修炼是指建立共同愿景、改善心智模式、实现自我超越、进行团队学习和学会系统思维。

()正确错误14:从众行为是指,群体成员企求自己的生活水平跟从群体的倾向。

()正确错误15:马斯洛认为,人们喜欢一个安全的、有秩序的、可预测的和有组织的的世界。

()正确错误----------专业最好文档,专业为你服务,急你所急,供你所需-------------16:目前国内公司的多元化特点主要表现在文化背景多元化、员工个体多元化和其他多元化因素。

()正确错误17:正式群体可分为冷淡型、乖僻型、策略型和保守型等类型。

()正确错误18:科学技术越是发展,就越要重视设备的因素。

()正确错误19:正式群体是为了完成组织所规定的特定目的与特定工作,而产生的正式的、官方的组织结构。

正向领导对员工抑制性建言的跨层次影响

关 键 词 :正 向 领 导 ;员 工 抑 制 性 建 言 ;自 我 效 能 感 ;团 队 建 言

DOI:10.6049/kjjbydc.2018040722

开 放 科 学 (资 源 服 务 )标 识 码 (OSID):

中 图 分 类 号 :F272.91

文 献 标 识 码 :A

文 章 编 号 :1001-7348(2019)13-0138-07

1 理论基础与研究假设

1.1 正向领导与员工抑制性建言 正向领导 又 称 积 极 领 导,是 变 革 时 代 对 领 导 的 新

要求,是由正 向 心 理 学、正 向 组 织 行 为 学、肯 定 式 探 询 等理论发展 而 来 的 一 个 新 兴 领 导 概 念:以 积 极 性 为 核 心,强调肯定导向,关 注 善 良 美 德,旨 在 促 进 个 体、组 织 的 积 极 结 果 ,实 现 非 凡 卓 越 绩 效 的 一 种 领 导 态 度 。 [7] 正向领 导 具 有 4 个 构 面:① 正 向 气 氛,是 指 以 积 极 情 绪 为主导的工作氛围,领 导 培 养 同 情 心、宽 容 心 和 感 恩 心 的策略,有助 于 形 成 正 向 气 氛;② 正 向 关 系,即 一 种 能 提高生产力 的 资 源,不 仅 是 指 与 他 人 友 好 相 处 或 是 不 与人闹矛盾,而 且 包 括 对 员 工 生 理、心 理、情 感 以 及 对

心理学文献报告一《与团队典型领导一起工作的追随者满意度》

文献报告题目: Followers 'satisfaction from working with group-prototypic leaders: Promotion focus as moderator中文题目:与团队典型领导一起工作的追随者满意度:促进型关注作为调节变量目录1. 根本信息 (3)题目 (3)作者信息 (3)2. 摘要 (4)3. 研究回忆 (5)基于社会认同理论的领导力效用分析 (5)调节理论与不同的群组偏私 (6)4. 研究对象、模型和方法 (7)实验1 (7)实验方法 (7)结果与讨论 (8)实验2 (9)实验方法 (9)4.2.2 结果与讨论 (10)5. 结论 (11)6. 局限 (12)7. 国内相关研究综述 (13)团队领导对团队的影响 (13)领导风格与员工满意度 (14)领导行为与员工满意度 (15)8. 未来研究方向 (16)文献总结 (16)个人观点 (16)参考文献 (18)1. 根本信息题目英文题目:Followers ' satisfaction from working with group -prototypic leaders: Promotion focus asmoderator文章来Anton io Pierro, Lavi nia Cicero,& E.Tory Higgi ns. Followers ' satisfact ion from 源:worki ng with group-prototypic leaders: Promoti on focus as moderator[J]. Jour nalof Experimental Social Psychology,2021(45):1105-1110.作者信息(1) AW Kruglanski, A Pierro, ET Higgins.Regulatory mode and preferred leadership Array styles: How fit increases job satisfaction[J].Basic and AppliedSocial Psychology,2007, 29 (2), 137-149(2) A Pierro, F Presaghi, TE Higgins, AW Kruglanski.Regulatory mode preferences forautonomy supporting versus controlling instructional styles[J].British Journal of EducationalPsychology ,2021,79 (4), 599-615(3) L Mannetti, M Giacomantonio, ET Higgins, A Pierro, AWKruglanski .Tailoring visual images to fit: Value creation in persuasivemessages[J].European Journal of Social Psychology,2021, 40 (2), 206-2152. 摘要追随者的促进性关注会对他们的满意度产生什么影响,当他们和一个自己团队的原型领导者一起工作的时候?我们认为高(vs.低)的推进型关注的追随者会更加积极的去回应一个团队的原型领导,以此作为一种推进内部(“推进我们〞)的道路,从而能够增加他们和领导一起工作的满意度。

人力资源开发teamwork英文正稿

1.1Compare different learning stylesKolb recognized that people tend to have a preference for a particular phase of the cycle, which he identified as a preferred learning style.Honey and Mumford also noted that ‘people vary not just in their learning skills but also in their learning styles. Why otherwise might two people, matched for age, intelligence and need, exposed to the same learning opportunity, react so differently?’Honey and Mumford formulated a popular classification of learning styles in terms of the attitudes and behaviours which determine an individual’s preferred way of learning.Learning styles are different ways that a person can learn. It's commonly believed that most people favor some particular method of interacting with, taking in, and processing stimuli or information. Psychologists have proposed several complementary taxonomies of learning styles. But other psychologists and neuroscientists have questioned the scientific basis for some learning style theories. A major report published in 2004 cast doubt on most of the main tests used to identify an individual's learning style.ActivistActivists involve themselves fully in new experiences. They are open-minded and enthusiastic about new things – but easily bored by long-term implementation and consolidation: act first and think about consequences later. They prefer to tackle problems by brainstorming. They easily get involved with others – but tend to centre activities on themselves.ReflectorReflectors like to stand back to observe and ponder new experiences, preferring to consider all angles and implications, and to analyse all available data, before reaching any conclusions or making any moves. When they do act, it is from awareness of the big picture. They tend to adopt a low profile, taking a back seat in meeting and discussions – though listening and observing others carefully and tend to have a slightly distant, tolerant, unruffled air.TheoristsTheorists are keen on basic assumptions, principles, theories, models and systems thinking. They are detached and analytical and like to analyse and synthesise facts and observations into coherent theories. They think problems through systematically and logically. They are interested in maximizing certainty, and so tend to be rigidly perfectionist and uncomfortable with subjectivity, ambiguity, lateral thinking and flippancy.PragmatistReflectors are eager to try out ideas, theories and technique to see if they work in practice. They like to get on with things, acting quickly and confidently on ideas that attract them-and tending to be impatient with ruminating and open-ended discussion. They are down to earth: enjoying practical decisions and responding to problems and opportunities ‘as a challenge’.Hang and Li Xiaochun are activists. Fan Jiaxin is theorist. Today our team will take reflector as an example and make some sample analysis.Reflectors like back then reflect on experience and examine them from different angles. They like to collect data, both their own data and the data obtained from others. They like to fully consider before make any conclusion.Taking our team member Lu Chen as an example, when she completed teamwork. Lu Chen is a reflector. When the team members are talking about how to finish the team work, she will not be particularly intense in group discussion. She will be quietly thinking and analysis topic in this time. After thinking and listened to the team members’ideas, she can consider put forward a perfect answer. Usually, this answer will be accepted by team members. This is the advantage of learning style. But it also has disadvantage. For example, in class, the teacher asks Lu Chen a question suddenly. Under the condition of no advance preparation, she will be nervous and incoherent.As a result, we've come to the conclusion that reflectors learning the best and the worst situation.Following activities are the best situations for reflectors:●Require or encourage them to observe and think of these activities●They listen and watch team work in the event. Sitting back in a meeting or at themovies●Allow them to have time to prepare before taking any action●They can hard study to find out the truth●they can make a decision under the condition of no pressure and no timelimitationFollowing activities are the worst situations for reflectors:●They were forced to be leadership or president●They involved in some situation need action without plan●Let them to react immediately and produce spontaneous ideas●Complete event under time constraints or pressure●Provided data is not enough to support the conclusion1.2 Explain the role of the learning curve and the importance of transferring learning to the workplaceThe role of the learning curveA learning curve is a graph showing the relationship between the time spent in learning and the level of competence attained. Hence, it describes the progress and variable pace of learning. It is common for people to say that they are on a steep learning curve when they have to acquire a lot of new knowledge or skills in a short period of time.The learning curve may be used in three ways:●To suggest typical patterns in the acquisition of a given skill or type of skill: thepace of skill acquisition, the standard at which performance levels out; the point at which performance plateaus.●To illustrate the progress of a given trainee’s learning/proficiency during thetraining progress, in order to monitor the progress and pace of training and to make allowances for different rates of learning and the steepness of the curve where necessary.●To plan the size of the chunks to be taught in one serving or stage of learning, thelength of practice periods before moving to the next stage and so on.A standard learning curve is initially steep, levelling out towards proficiency. However, in practice this will depend on the design of the learning program and the motivation and aptitude of the learner. The curve for the acquisition of skills typically shows one or more plateaus, reflecting the trainee’s need to consolidate wha t he has learned so far, to correct some aspects of performance to regain motivation and focus after the initial effort, or to establish habitual or unconscious competence in one skill prior to moving on to a new area. Momentum then gathers again, until the trainee reaches proficiency level, where the curve will level off unless there is an injection of new equipment or methods, or fresh motivation, to lift output again.Here is the learning curve:Level ofProficiencyLearning timeAs you can see, the chart is steepest at the beginning, when a person first starts learning. The beginner gains knowledge quickly, learning in just a few minutes. There is more to learn, but he will never learn as quickly as she did at the beginning of her lesson.It is known to all that learning curves can be quite complex, going down as well as up: for example, if the trainee is unable to practice or apply newly acquired skills and forgets, or refuses to accept new areas of conscious incompetence which emerge in the course of training. An up-and-down transition curve is common in cases where an individual changes jobs or work methods, or makes the transition from a non-managerial to a managerial position.the importance of transferring learning to the workplace:In my opinion, learning plays very important role in workplace. In the following text, I will discuss the importance of transferring learning to the workplace from 2 terms.Firstly, the importance for ourselves.Learning is the ladder of human progress. In the school, the knowledge we learn not only includes the knowledge in books, but also includes the following 4 aspects:1.Learning to survive. We need to learn to developing after surviving, survival and development, and striving for survival and development.2.Learning to communicate. We need to learn to adapt to the complex relationships.3.Learning to learn. We need to learn to master the art of learning.4.Learning skills.Only making the above 4 aspects achieving mastery through a comprehensive can we enter the society and our jobs with confidence.Secondly, the importance for enterprises.T he development of human is the strong power for enterprises’ development, and the most important power source of the development of human is learning. Only through learning and applying knowledge and skills got by learning to the development of the enterprise can make an enterprise get substantial progress and development. For example, high school teachers may improve their teaching ability by listening to other outstanding teachers' classes and learning the way of teaching. Again, for example, the mechanics may try to complete their work more efficiently through apprenticing other richly experienced old mechanics and learning their methods.In an enterprise, there will always have some people who prefer learning, and there also have some people who do not prefer learning. The development of the enterprise depends on those who prefer learning. When the development of the enterprise can't keep up with the development of people who prefer learning, these people might leave. And, in turn, those who can't keep up with the development of the enterprise will eventually be eliminated by enterprise. An individual's own development depends largely on whether it is interested in the industry because onlywhen it is interested in this work, it would find pleasure in work and find its insufficient in work that let it try to learn together way. When all become a virtuous cycle, work and life will be full of fun. In one word, learning is also a driving force for the development of the society.1.3Assess the contribution of learning styles and theories when planning anddesigning a learning eventMost people will clearly have a strong preference for a given learning style. The ability to switch between different styles is not one that we should assume comes easily or natural to many people.People who have a clear learning style preference will tend to learn more effectively if learning is orientated according to their preference. For example, assimilators will not be comfortable being thrown in at the deep end without notes and instructions, accommodators are likely to become frustrated if they are forced to read lots of instructions and rules and are unable to get hands-on experience as soon as possible. Tension can develop where there are differences in learning style between educators and students.Where possible it is helpful if workplace educators can identify the students learning style and provide opportunities that work to their strength, however the aim for the students is to engage in learning across different learning styles and develop abilities across a range of techniques rather than just their preferred styles.Students need to be able to adapt to the presenting situation, and develop their preferred as well as non-preferred learning styles.Learning StyleUnderstanding the way that you learn, your learning style, will help you select your learning activities to ensure you learn most effectively. This does not mean that you cannot learn from activities that are not specifically suited to your own style, in fact selecting activities outside your normal style will help you develop your learning skills.Educational ImplicationsBoth Kolb's learning stages and cycle could be used by teachers to critically evaluate the learning provision typically available to students, and to develop more appropriate learning opportunities.Educators should ensure that activities are designed and carried out in ways that offer each learner the chance to engage in the manner that suits them best. Also, individuals can be helped to learn more effectively by the identification of their lesser preferred learning styles and the strengthening of these through the application of the experiential learning cycle.Ideally, activities and material should be developed in ways that draw on abilities from each stage of the experiential learning cycle and take the students through the whole process in sequence.It is not possible to put forward a simple definition of learning, because dispite intensive scientific and practical work on the subject, there are different ways ofunderstanding how the process works, what it involves, and what we mean when we say that a person knows something. Whichever approach it is based on, learning theory offers certain useful propositions foe the design of effective training programmers.There are three basic theories how learning works. One of the basic theories is that The behaviourist ( or stimulus-response):The behaviourist (our stimulus-response) approach. Behaviourist psychology is based on empirical epistemology (the belief that the human mind operates purelyon infomation gained from the senses by experiences and concentrates on observable behaviour,since thought processes are neccery amenable to scientific study.Such as:(1) the individual should be motivated to learn. The purpose and benefits of a learning activity should be made clear, according to the individual's motives or goals: reward, challenge, competence or whatever. Organisational support is critical to the effectiveness of its member’s learning(2) clear goals and objectives should be set, so that each task has some meaning. This will help trainees in the control process that leads to learning, providing targets against which performance will constantly be measured and agjusted. Motivation to learn will be enhanced if the individual has been involved in setting his or her own learning goals.(3) learning should be structured and paced to allow learning processes to take place effectively and progressively. Each stage of learning should present a challene , without overloading trainees so that they lose confidence and the ability to assimilate information.(4) exposure to learning materials and interactive input(from learning software and /or from coaches or facilitatoes)enriches the cognitive process and encourages the internalisation of learning. Case-studies, probelm solving exercises and so on engage the purposive process of learning.(5) there should be timely, relevant feedback on performance and progress(6) positive and negative reinforcement should be judiciously used(7) active participation in the learning experience(for example, in action learning or discovery learning)is generally more effective than passive reception.1.1written by Luchen and Fanjiaxin1.2written by Qiaofei and Huating1.3written by Lixiaochun and Wenghang。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

In press: Journal of Organizational Behavior

July 26, 2010

Task Type as a Moderator of Positive/Negative

Feedback Effects on Motivation and Performance:

A Regulatory Focus Perspective

DINA VAN DIJK

Health Systems Management

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

AVRAHAM N. KLUGER

School of Business Administration

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem

ABSTRACT

Applying regulatory focus theory (Higgins, 1997), we hypothesized that the effect of

positive/negative feedback on motivation and performance is moderated by task type,

which is argued to be an antecedent to situational regulatory focus (promotion or

prevention). Thus, first we demonstrated that some tasks (e.g., tasks requiring creativity)

are perceived as promotion tasks, whereas others (e.g., those requiring vigilance and

attention to detail) are perceived as prevention tasks. Second, as expected, our tests in two

studies of the moderation hypothesis showed that positive feedback increased self-

reported motivation (meta-analysis across samples: N = 315, d = .43) and actual

performance (N = 55, d = .67) among people working on promotion tasks, relative to

negative feedback. Positive feedback, however, decreased motivation (N = 318, d = -.33)

and performance (N = 55, d = -.37) among individuals working on prevention tasks,

relative to negative feedback. These findings suggest that (a) performance of different

tasks can affect regulatory focus and (b) variability in positive/negative feedback effects

can be partially explained by regulatory focus and task type.