古扎拉蒂第五版数据Table 11_8

行为科学统计精要 (8)[58页]

![行为科学统计精要 (8)[58页]](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/15d6d6ee580216fc710afd29.png)

Tools You Will Need

• z-Scores (Chapter 5) • Distribution of sample means (Chapter 7)

– Expected value – Standard error – Probability and sample means

8.1 Hypothesis Testing Logic

Chapter 8 Introduction to Hypothesis Testing

PowerPoint Lecture Slides

Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences

Eighth Edition by Frederick J. Gravetter and Larry B. Wallnau

Chapter 8 Learning Outcomes

1 • Understand logic of hypothesis testing 2 • State hypotheses and locate critical region(s) 3 • Conduct z-test and make decision 4 • Define and differentiate Type I and Type II errors 5 • Understand effect size and compute Cohen’s d 6 • Make directional hypotheses and conduct one-tailed test

Figure 8.2 Unknown Population in Basic Experimental Design

计量经济学导论 第五版 答案

APPENDIX ASOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMSA.1 (i) $566.(ii) The two middle numbers are 480 and 530; when these are averaged, we obtain 505, or $505.(iii) 5.66 and 5.05, respectively.(iv) The average increases to $586 while the median is unchanged ($505).A.3 If price = 15 and income = 200, quantity = 120 – 9.8(15) + .03(200) = –21, which is nonsense. This shows that linear demand functions generally cannot describe demand over a wide range of prices and income.A.5 The majority shareholder is referring to the percentage point increase in the stock return, while the CEO is referring to the change relative to the initial return of 15%. To be precise, the shareholder should specifically refer to a 3 percentage point increase.$45,935.80.≈ $40,134.84. When exper = 5, salary = exp[10.6 + .027(5)] ≈A.7 (i) When exper = 0, log(salary) = 10.6; therefore, salary = exp(10.6) (ii) The approximate proportionate increase is .027(5) = .135, so the approximate percentage change is 13.5%.14.5%, so the exact percentage increase is about one percentage point higher.≈(iii) 100[(45,935.80 – 40,134.84)/40,134.84)A.9 (i) The relationship between yield and fertilizer is graphed below. (ii) Compared with a linear function, the functionyieldhas a diminishing effect, and the slope approaches zero as fertilizer gets large. The initial pound of fertilizer has the largest effect, and each additional pound has an effect smaller than the previous pound.APPENDIX BSOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMSB.1 Before the student takes the SAT exam, we do not know – nor can we predict with certainty – what the score will be. The actual score depends on numerous factors, many of which we cannot even list, let alone know ahead of time. (The student’s innate ability, how the student feels on exam day, and which particular questions were asked, are just a few.) The eventual SAT score clearly satisfies the requirements of a random variable.B.3 (i) Let Yit be the binary variable equal to one if fund i outperforms the market in year t. By assumption, P(Yit = 1) = .5 (a 50-50 chance of outperforming the market for each fund in each year). Now, for any fund, we are also assuming that performance relative to the market isP(Yi2 = 1) P(Yi,10 = 1) = (.5)10 = 1/1024 (which is slightly less than .001). In fact, if we define a binary random variable Yi such that Yi = 1 if and only if fund i outperformed the market in all 10 years, then P(Yi = 1) =1/1024.⋅independent across years. But then the probability that fund i outperforms the market in all 10 years, P(Yi1 = 1,Yi2 = 1, , Yi,10 = 1), is just the product of the probabilities: P(Yi1 = 1).983. This means, if performance relative to the market is random and independent across funds, it is almost certain that at least one fund will outperform the market in all 10 years.≈P(Y4,170 = 0) = 1 –(1023/1024)4170 ⋅⋅⋅ P(Y2 = 0)⋅= 1/1024. We want to compute P(X ≥ 1) =1 – P(X = 0) = 1 –P(Y1 = 0, Y2 = 0, …, Y4,170 = 0) = 1 – P(Y1 = 0)θ)distribution with n = 4,170 and θ(ii) Let X denote the number of funds out of 4,170 that outperform the market in all 10 years. Then X = Y1 + Y2 + + Y4,170. If we assume that performance relative to the market is independent across funds, then X has the Binomial (n,(iii) Using the Stata command Binomial(4170,5,1/1024), the answer is about .385. So there is a nontrivial chance that at least five funds will outperform the market in all 10 years..931.≈ 1) = 1 – P(X = 0) = 1 – (.8)12 ≥B.5 (i) As stated in the hint, if X is the number of jurors convinced of Simpson’s innocence, then X ~ Binomial(12,.20). We want P(X(ii) Above, we computed P(X = 0) as about .069. We need P(X = 1), which we obtain from1 – (.069 + .206) = .725, so there is almost a three in four chance that the jury had at least two members convinced of Simpson’s innocence prior to the trial.≈ 2) ≥ .206. Therefore, P(X ≈ (.2)(.8)11 ⋅ = .2, and x = 1:P(X = 1) = 12θ(B.14) with n = 12,B.7 In eight attempts the expected number of free throws is 8(.74) = 5.92, or about six free throws.X, and so the expected value of Y is 1,000 times the expected value of X, and the standard deviation of Y is 1,000 times the standard deviation of X. Therefore, the expected value and standard deviation of salary, measured in dollars, are $52,300 and $14,600, respectively.⋅B.9 If Y issalary in dollars then Y = 1000。

第8章 干预性或观察性研究的meta分析

差值的均数和标准差;另外,有些研究没有报道

标准差,只报道了95%可信区间,这时则需要按照 Cochrane Handbook的要求对结果进行转化。

异质性检验

1.检验原理

不可避免地,纳入同一个Meta分析的所有研 究都存在差异,不同研究间的各种变异被称为异 质性。 Meta- 分析的统计学原理要求只有同质的 资料才能进行统计量的合并,即假设各个不同研 究都是来自非同一个总体( H0 ),各个不同样本 来自不同总体,存在异质性(备择假设 H1 )。如 果检验结果 P>0.10 ,拒绝 H1 ,接受 H0 ,可认为多 个同类研究具有同质性;当异质性检验结果 P≤0.10,可认为多个研究结果有异质性。

合并效应量

随机效应模型目前多用 D-L 法( DerSimonian & Laird 法) 。随机效应模型估计合并效应量,实际上是计算多个原始 研究效应量的加权平均值。以研究内方差与研究间方差之

和的倒数作为权重,调整的结果是样本量较大的研究给予

较小的权重,而样本量较小的研究则给予较大的权重。因 此,随机效应模型处理的结果可能消弱了质量较好的大样 本研究的信息,而夸大了质量可能较差的小样本研究的信 息,故采用随机效应模型的Meta-分析在下结论时应慎重。

Meta-分析结果的解释

Meta- 分析最常使用森林图( forest plots )来

展示其统计分析的结果。在森林图中,以一条数 值为0或1的中心垂直线为无效标尺线,即无统计

学意义的值。RR或OR的无效线对应的横轴尺度是

1 ,而 RD 、 MD 、 WMD 和 SMD 的无效线对应的横轴尺

度是0。

(4)生存资料的效应量可用风险比(HR)。

MINITAB使用教程(共129张PPT)

什么是子群? 处理数据常分成组。例如,运送数据用发 货分组,化学处理数据用批而半导体处理

数据用 lot。这些数据组被称为子群。这 些子群还用在短期和长期处理能力中。

寻找

工具栏(Tool Bar)

任务栏(Task Bar)

文件管理 数据修改

数据操作

计算功能

统计分析 图表制作

数据管理

表示窗口

六西格玛

帮助

任务栏(Task Bar)

文件管理

数据修改 数据操作

计算功能

统计分析 图表制作

数据管理

表示窗口

六西格玛 帮助

任务栏(Task Bar)

文件管理

计算功能

数据修改

统计分析

数据操作

图表制作

数据管理

第1节 数据操作(Manip)-3/6

2.如何将数据从‘代码化数据’转变成‘自然码数据’呢? Manip>Code>Numeric to Text

第1节 数据操作(Manip)-4/6

3.改变数据的排列,将数据由‘行’转变成‘列’呢?

Manip>Stack>Stack Rows

C2—C6

C8

C1

MINITAB-Data-Files>

从1开始 到20结束 间隔1

每个数重复1次 整体数重复1次

第2节 计算功能(Calc)-4/5

4.如何取‘随机顺序’?。如何‘取样’?。

Calc>Random Data>Sample From Columns MINITAB-Data-Files>

世界各国GDP能耗对比

Energy Information Administration International Energy Annual 2006 Table Posted: December 19, 2008 Next Update: August 2009 Table Notes and Sources

E.1g World Energy Intensity--Total Primary Energy Consumption per Dollar of Gross Domestic Product Using Market Exchange Rates, 1980-2006

Page 1

Table E.1g World Energy Intensity--Total Primary Energy Consumption per Dollar of Gross Domestic Product Using Market Exchange Rates, 1980-2006 (Btu per (2000) U.S. Dollars)

Energy Information Administration International Energy Annual 2006 Table Posted: December 19, 2008 Next Update: August 2009 Table Notes and Sources

E.1g World Energy Intensity--Total Primary Energy Consumption per Dollar of Gross Domestic Product Using Market Exchange Rates, 1980-2006

( Btu per (2000) U.S. Dollars) Region/Country Bermuda Canada Greenland Mexico Saint Pierre and Miquelon United States North America Antarctica Antigua and Barbuda Argentina Aruba Bahamas, The Barbados Belize Bolivia Brazil Cayman Islands Chile Colombia Costa Rica Cuba Dominica Dominican Republic Ecuador El Salvador Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas) French Guiana Grenada Guadeloupe Guatemala Guyana Haiti Honduras Jamaica Martinique Montserrat Netherlands Antilles Nicaragua 1988 3,873 20,911 NA 11,143 NA 12,283 12,813 NA 12,911 10,021 5,742 8,456 7,310 5,948 14,422 10,474 3,666 12,699 15,417 7,947 12,574 4,462 9,762 18,976 6,947 NA 7,594 4,215 NA 6,644 30,484 6,740 9,159 13,207 3,501 NA 60,745 13,463 1989 4,694 20,648 NA 11,283 NA 12,167 12,696 NA 12,240 10,428 7,076 9,411 7,603 7,605 15,636 10,447 3,475 12,949 15,454 8,161 12,736 4,700 8,910 18,529 6,986 NA 7,680 4,153 NA 6,716 21,445 6,235 10,155 14,171 4,690 NA 59,484 15,534 1990 3,310 20,233 NA 11,197 NA 11,902 12,418 NA 12,481 10,279 6,655 9,945 8,158 9,672 15,837 11,514 3,434 13,924 13,876 7,737 12,817 4,463 10,257 19,244 6,897 NA 8,179 6,095 NA 7,018 21,311 4,121 11,438 14,171 4,917 NA 57,191 14,621 1991 2,978 20,893 NA 11,091 NA 11,916 12,455 NA 12,054 9,810 6,977 9,061 8,569 9,683 14,852 11,877 3,552 12,864 14,721 8,068 13,244 4,439 10,345 19,356 6,588 NA 8,266 5,882 NA 6,606 23,158 3,949 11,014 14,332 4,224 NA 53,295 14,279 1992 2,395 21,328 NA 10,921 NA 11,716 12,285 NA 11,920 9,369 7,205 7,753 9,333 7,395 15,712 12,117 3,510 12,287 14,248 8,213 13,254 4,251 9,712 20,788 6,865 NA 6,128 5,971 NA 6,863 24,536 4,908 10,704 15,288 4,631 NA 50,903 15,779 1993 2,697 21,300 NA 10,661 NA 11,630 12,191 NA 11,924 9,463 6,957 8,137 9,381 6,916 14,948 12,009 3,183 12,392 14,681 8,364 15,404 4,453 8,616 19,703 6,595 NA3,799 10,139 15,221 6,211 NA 49,106 16,007 1994 2,654 20,905 NA 10,578 NA 11,392 11,956 NA 11,764 8,806 7,006 8,949 8,496 6,541 15,886 11,867 3,289 12,476 14,432 8,687 15,561 4,992 8,860 20,606 6,824 NA 8,077 7,589 NA 7,684 26,243 3,583 10,274 15,556 6,031 NA 48,435 15,701 1995 2,529 20,634 NA 11,101 NA 11,352 11,939 NA 12,606 9,367 7,893 10,470 8,493 8,167 17,285 12,043 3,411 12,494 13,658 8,796 15,478 5,508 9,113 19,719 7,838 NA 9,062 6,855 NA 7,593 21,354 5,365 10,529 16,733 6,064 NA 50,879 15,670

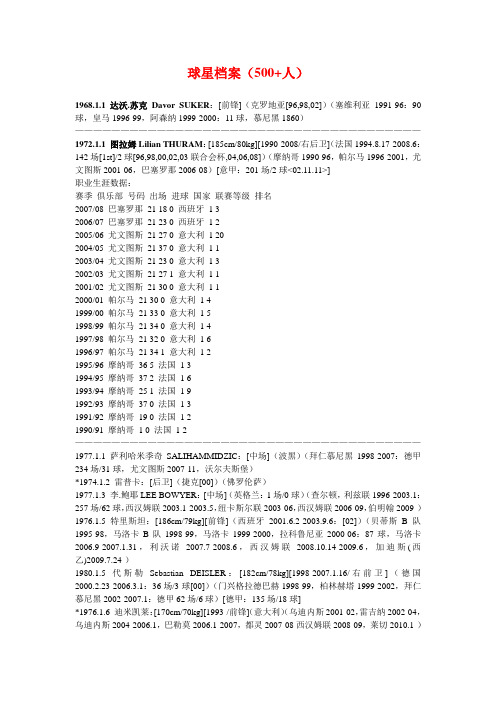

国际足球 球员档案

球星档案(500+人)1968.1.1 达沃.苏克Davor SUKER:[前锋](克罗地亚[96,98,02])(塞维利亚1991-96:90球,皇马1996-99,阿森纳1999-2000:11球,慕尼黑1860)——————————————————————————————————————1972.1.1 图拉姆Lilian THURAM:[185cm/80kg][1990-2008/右后卫](法国1994.8.17-2008.6:142场[1st]/2球[96,98,00,02,03联合会杯,04,06,08])(摩纳哥1990-96,帕尔马1996-2001,尤文图斯2001-06,巴塞罗那2006-08)[意甲:201场/2球<02.11.11>]职业生涯数据:赛季俱乐部号码出场进球国家联赛等级排名2007/08 巴塞罗那21 18 0 西班牙1 32006/07 巴塞罗那21 23 0 西班牙1 22005/06 尤文图斯21 27 0 意大利1 202004/05 尤文图斯21 37 0 意大利1 12003/04 尤文图斯21 23 0 意大利1 32002/03 尤文图斯21 27 1 意大利1 12001/02 尤文图斯21 30 0 意大利1 12000/01 帕尔马21 30 0 意大利1 41999/00 帕尔马21 33 0 意大利1 51998/99 帕尔马21 34 0 意大利1 41997/98 帕尔马21 32 0 意大利1 61996/97 帕尔马21 34 1 意大利1 21995/96 摩纳哥36 5 法国1 31994/95 摩纳哥37 2 法国1 61993/94 摩纳哥25 1 法国1 91992/93 摩纳哥37 0 法国1 31991/92 摩纳哥19 0 法国1 21990/91 摩纳哥1 0 法国1 2 ——————————————————————————————————————1977.1.1 萨利哈米季奇SALIHAMMIDZIC:[中场](波黑)(拜仁慕尼黑1998-2007:德甲234场/31球,尤文图斯2007-11,沃尔夫斯堡)*1974.1.2 雷普卡:[后卫](捷克[00])(佛罗伦萨)1977.1.3 李.鲍耶LEE BOWYER:[中场](英格兰:1场/0球)(查尔顿,利兹联1996-2003.1:257场/62球,西汉姆联2003.1-2003.5,纽卡斯尔联2003-06,西汉姆联2006-09,伯明翰2009-)1976.1.5 特里斯坦:[186cm/79kg][前锋](西班牙2001.6.2-2003.9.6:[02])(贝蒂斯B队1995-98,马洛卡B队1998-99,马洛卡1999-2000,拉科鲁尼亚2000-06:87球,马洛卡2006.9-2007.1.31,利沃诺2007.7-2008.6,西汉姆联2008.10.14-2009.6,加迪斯(西乙)2009.7.24-)1980.1.5 代斯勒Sebastian DEISLER:[182cm/78kg][1998-2007.1.16/右前卫](德国2000.2.23-2006.3.1:36场/3球[00])(门兴格拉德巴赫1998-99,柏林赫塔1999-2002,拜仁慕尼黑2002-2007.1:德甲62场/6球)[德甲:135场/18球]*1976.1.6 迪米凯莱:[170cm/70kg][1993-/前锋](意大利)(乌迪内斯2001-02,雷吉纳2002-04,乌迪内斯2004-2006.1,巴勒莫2006.1-2007,都灵2007-08西汉姆联2008-09,莱切2010.1-)1972.1.8 法瓦利Giuseppe FA V ALLI:[181cm/77kg][1988-2010.5.6/左后卫,中后卫](意大利:47场/3球[04])(克雷莫纳1988-92,拉齐奥1992-2004,国际米兰2004-06,AC米兰2006-10)*1977.1.8 科科COCO:[181cm/78kg][1995-2007/左后卫,左前卫](意大利:17场/0球[02])(AC米兰1995-97,维琴察(租借)1997-98,AC米兰1998-99,都灵1999-2000(租借),AC 米兰2000-2002.1,巴塞罗那(租借)2002.1-2002.6,国际米兰2002-05,利沃诺2005-06,都灵2006-07)1979.1.8 穆图Adrian MUTU:[前锋](罗马尼亚:74场/35球[00,08])(帕尔马2002-03,切尔西2003-04,锡耶纳2004-2005.1,尤文图斯2005.1-2006.7,佛罗伦萨2006-2011,切塞纳2011-)1967.1.9 卡尼吉亚:[172cm/68kg][1985-2005.2.19/前锋](阿根廷1987-2002:50场/16球[90,91美洲杯,92洲际杯,93美洲杯,94,02])(河床1985-88,维罗纳1988-89,亚特兰大1989-92,罗马1992-94,本菲卡1994-95,博卡青年1995-96,1997-98,亚特兰大1999-2000,邓迪2000-01,格拉斯哥流浪者2001-03,卡塔尔SC队2003-04)[职业生涯数据:394场/106球]1974.1.9 萨维奥SA VIO:[中场](巴西)(弗拉门戈1992-1997.11,皇马1997.12-2002.8:192场/52球,波尔多2002-03,萨拉戈萨2003-2006.1,)——————————————————————————————————————1978.1.9 加图索GA TTUSO:[176cm/77kg][1995-/中场](意大利2000.11.15-2010:73场/1球[02,04,06,08,09联合会杯,10])(佩鲁贾1995-97:联赛10场/0球,格拉斯哥流浪者1997-98:47场/9球[苏超40场/7球],萨莱尼塔纳1998-99:意甲25场/0球,AC米兰1999-2012:468场/11球[意甲:335场/9球,国内杯赛:26场/0球,欧战:101场/2球,其它:6场/0球])职业生涯数据:俱乐部549场/20?球赛季转会俱乐部联赛出场进球欧战出场进球1995-1996 佩鲁贾意乙2 01996-1997 佩鲁贾意甲8 01997-1998 格拉斯哥流浪者苏超36 7 联盟杯2 11998-1999 格拉斯哥流浪者苏超4 0 联盟杯5 11998-1999 萨勒尼塔纳意甲25 01999-2000 AC米兰意甲22 1 冠军杯5 02000-2001 AC米兰意甲24 0 冠军杯10 02001-2002 AC米兰意甲32 0 冠军杯10 02002-2003 AC米兰意甲25 0 冠军杯14 02003-2004 AC米兰意甲33 1 冠军杯7 12004-2005 AC米兰意甲32 0 冠军杯11 02005-2006 AC米兰意甲35 3 冠军杯11 02006-2007 AC米兰意甲30 1 冠军杯13 02007-2008 AC米兰意甲31 1 冠军杯8 02008-2009 AC米兰意甲12 0 联盟杯4 12009-2010 AC米兰意甲22 0 冠军杯1 02010-2011 AC米兰意甲31 2 冠军杯2011-2012 AC米兰意甲 6 0 冠军杯——————————————————————————————————————*1974.1.10 马莱:[前锋](法国)(里昂)1978.1.11 赫斯基Emile HESKEY:[190cm/88kg][1994-/前锋](英格兰1999.4.28-2010.6.27:62场/7球[02,04,10])(莱斯特1994-2000.3,利物浦2000.3-2004.7:150场/39球,伯明翰2004-06,维冈竞技2006.7-2009.1,阿斯顿维拉2009.1-)1957.1.11 布赖恩.罗布森Bryan ROBSON:[中场](英格兰:90场/26球[82,86,88,90])(西布罗姆维奇1975-81,曼联1981-94:461场/99球,米德尔斯堡1994-96)*1973.1.12 伊布拉辛.巴:[中场](法国)(AC米兰)*1972.1.13 博斯尼奇:[门将](澳大利亚)(曼联)*1973.1.15 贝托托:[后卫](意大利)(乌迪内斯)*1981.1.15 迪乌夫:[1998-/前锋,中场](塞内加尔[02])(朗斯2000-02,利物浦2002-04,博尔顿2004-08,桑德兰2008-09,布莱克本2009-11)*1983.1.15 维亚纳:[中场](葡萄牙[02,12])(纽卡斯尔联)*1976.1.16 莫费奥:[中场](意大利)(国际米兰,AC米兰,帕尔马)——————————————————————————————————————1967.1.18 萨莫拉诺Ivan ZAMORANO:[178cm/72kg][1985-2003.12.22/前锋](智利1987.6.19-1999.7:69场/34球[98])(科布塞尔1985-88,瑞士圣加伦1988-90,塞维利亚1990-92,皇马1992-96:101球,国际米兰1996-2000:41球,墨西哥美洲2001-02,科洛科洛2002-03)[636场/314球(西甲:76球)]职业生涯数据:赛季俱乐部号码出场进球国家联赛等级排名2003 科洛科洛14 82001/02 墨西哥城美洲36 202000/01 国际米兰18 2 1 意大利1 51999/00 国际米兰18 30 7 意大利1 41998/99 国际米兰18 25 9 意大利1 81997/98 国际米兰9 13 2 意大利1 21996/97 国际米兰9 31 7 意大利1 31995/96 皇家马德里29 12 西班牙1 61994/95 皇家马德里38 28 西班牙1 11993/94 皇家马德里36 11 西班牙1 41992/93 皇家马德里34 25 西班牙1 21991/92 塞维利亚30 12 西班牙1 121990/91 塞维利亚29 9 西班牙1 81990/91 圣加伦6 1 瑞士2 11989/90 圣加伦33 23 瑞士1 51988/89 圣加伦17 10 瑞士2 11988 科布塞尔10 141987 科布塞尔16 211986 科布塞尔0 01985 科布塞尔0 0 ——————————————————————————————————————1971.1.18 瓜迪奥拉Josep GUARDIOLA:[180cm/70kg][1988-2006.11/后腰](西班牙1992.10.14-2001:47场/5球[94,00])(巴塞罗那B队1988-1990,巴塞罗那1990-2001:268场/6球,布雷西亚2001-2002.1,罗马2002.1-2002.6,布雷西亚2002-03,卡塔尔阿尔阿赫利2003-05,墨西哥多拉多斯2005-06)1976.1.18 加拉尔多:[1992-2011/前腰](阿根廷1994.11.16-2003.4.30:44场/14球[97美洲杯,98])(河床1992-99,摩纳哥1999-2003,河床2003-06,巴黎圣日耳曼2006.7-2008.1,美国华盛顿特区联2008.1-2009.2,河床2009.2-2010.7,乌拉圭民族2010.8-2011.7)1977.1.19 劳伦:[右后卫](喀麦隆[98,02])(马洛卡,阿森纳2001-08)*1979.1.20 博纳佐利:[门将](意大利)(罗马)*1978.1.20 扎乌利:(意大利)(拉齐奥)1977.1.21 菲尔.内维尔Phil NEVILLE:[1994-/后卫,后腰](英格兰[96,00,04])(曼联1994-2005:386场/8球,埃弗顿2005-)1975.1.21 巴特Nicky BUTT:[178cm/76kg][1992-2010,2010.12-2011.5/后腰](英格兰1997.3.29-2004.11.17:39场/0球[02])(曼联1992-2004:387场/26球[英超:269场/21球],纽卡斯尔联2004-05,伯明翰(租借)2005-06,纽卡斯尔联2006-10,香港南华2010.12-2011.5)[英超:424场/29球]1971.1.22 科利莫尔:[1990-2001.3/前锋](英格兰:3场/0球)(诺丁汉森林1993-95,利物浦1995-97:35球,阿斯顿维拉1997-99)1980.1.22 伍德盖特:[中后卫](英格兰)(利兹联1998.8-2003.1,纽卡斯尔联2003.1-2004.8,皇马2004-06,米德尔斯堡2006.8-2008.1,托特纳姆热刺2008.1-2009.7,斯托克城)——————————————————————————————————————1977.1.22 中田英寿:[175cm/72kg][1995-2006.6/前腰](日本1997.5-2006.6:40场/7球[98,01联合会杯,02,03联合会杯,05联合会杯,06])(平冢贝尔马尔1995-1998.7,佩鲁贾1998.7-2000.1,罗马2000.1-2001.7,帕尔马2001.7-2003.12,博洛尼亚2003.12-2004.7,佛罗伦萨2004.7-2005.7,博尔顿(租借)2005.8-2006.6)[意甲:182场/24球]年份俱乐部出场进球1995 平冢贝尔马尔26 81996 平冢贝尔马尔26 21997 平冢贝尔马尔21 31998 平冢贝尔马尔12 398/99 佩鲁贾33 1099/00 佩鲁贾15 299/00 罗马15 300/01 罗马15 201/02 帕尔马24 102/03 帕尔马31 403/04 帕尔马12 003/04 博洛尼亚17 204/05 佛罗伦萨20 005/06 博尔顿27 1 ——————————————————————————————————————1984.1.23 罗本ROBBEN:[2002-/边前卫,前锋](荷兰:52场/15球<10.7.13>[04,06,08,10,12])(埃因霍温2002-04,切尔西2004-07,皇马2007-09:[08-09:8球7助攻],拜仁慕尼黑2009-:德甲57场/39球19助攻<12.4.1>)——————————————————————————————————————1967.1.25 吉诺拉David GINOLA:[186cm/82kg][1985-2002/中场](法国1991-1993.11.17:17场/3球)(巴黎圣日耳曼1992.1-1995.7,纽卡斯尔联1995-97,托特纳姆热刺1997-2000,阿斯顿维拉2000.7-2002.1)——————————————————————————————————————1980.1.25 哈维XA VI Hernandez:[170cm/68kg][1997-/中场](西班牙2000.11.15-:114场[3rd]/11球<12.7.2>[02,04,06,08,09联合会杯,10,12])(巴塞罗那B队1997-99,巴塞罗那1998.8.18-:628场[1st]/72球<11-12>[西甲:414场[1st]/48球,国王杯:57场/9球,西班牙超级杯:10场/3球,欧冠:126场/10球,联盟杯:13场/1球,欧洲超级杯:3场/0球,世俱杯:5场/1球])[07-08:51场/10球,08-09:49场/10球38助攻,09-10,10-11:5球,11-12:48场/14球13?助攻]职业生涯数据:赛季俱乐部联赛出场进球欧战出场进球1997-1998 巴塞罗那B 西乙B3组联赛33 21998-1999 巴塞罗那B 西乙28 01998-1999 巴塞罗那西甲17 1 冠军杯6 01999-2000 巴塞罗那B 西乙B3组联赛 4 11999-2000 巴塞罗那西甲24 0 冠军杯10 12000-2001 巴塞罗那西甲20 2 冠军杯3 0 联盟杯6 02001-2002 巴塞罗那西甲35 4 冠军杯14 02002-2003 巴塞罗那西甲29 2 冠军杯14 12003-2004 巴塞罗那西甲36 4 联盟杯7 12004-2005 巴塞罗那西甲36 3 冠军杯8 02005-2006 巴塞罗那西甲16 0 冠军杯4 02006-2007 巴塞罗那西甲35 3 冠军杯7 02007-2008 巴塞罗那西甲35 7 冠军杯12 12008-2009 巴塞罗那西甲35 6,20 冠军杯14 32009-2010 巴塞罗那西甲34 3,14 冠军杯11 12010-2011 巴塞罗那西甲31 3,7 冠军杯9 22011-2012 巴塞罗那西甲31 10,7 冠军杯9 1助攻数据(01/02-11/12):139次[01-02:13助攻,02-03:5助攻,03-04:13助攻,04-05:11助攻,05-06:2助攻,06-07:7助攻,07-08:9助攻,08-09:31助攻,09-10:19助攻,10-11:16助攻,11-12:13助攻]官方数据:104次(西甲69,欧冠20,国王杯11,世俱杯1,西班牙超级杯3,欧洲超级杯0)个人荣誉:2008年欧洲杯最佳球员;2009年世界足球先生第三名,2009年欧洲金球奖第三名;2010年国际足联金球奖第三名;2011年国际足联金球奖第三名——————————————————————————————————————*1981.1.25 杰弗斯:[前锋](英格兰)(阿森纳)*1976.1.25 巴勃罗.伊瓦涅斯:[后卫](西班牙[06])(塞维利亚)1978.1.28 布冯BUFFON:[191cm/83kg][1995-/门将](意大利1997.10.29-:119场[3rd]<11.6.29>[98,02,04,06,08,09联合会杯,10,12])(帕尔马1995-2001:意甲168场,尤文图斯2001-:397场<11-12>)1978.1.28 卡拉格Jamie CARRAGHER:[182cm/76kg][1996-/后卫](英格兰1999.4.28-2007,2010:38场/0球[06,10])(利物浦1996.10-:699场[2th][英超:483场]<11-12>)[欧洲三大杯:127场/1球(欧冠:80场/0球)] ——————————————————————————————————————1966.1.29 罗马里奥ROMARIO de Souza Faria身高/体重:167cm/70kg职业生涯:1983-2008.4.15场上位置:前锋国家队:巴西1987.5.23-2005.4.27:70场/55球[3rd](总共71球[3rd])[89美洲杯,90,94,97美洲杯,97联合会杯](世界杯预选赛11球)俱乐部:奥拉里亚1983-85,达伽马1985-88,埃因霍温1988-93:(荷甲:138场/127球),巴塞罗那1993-1995.1:65场/39球(西甲:46场/34球),弗拉门戈1995.1-1996,瓦伦西亚1996-1997.12,弗拉门戈1997.12-2000,达伽马2000-01,弗卢米嫩塞2002-03,卡塔尔阿尔萨德(租借)2003.2-2003.4,弗卢米内塞2003.4-2004.10,达伽马2005.1.22-2006.4,迈阿密溶合(租借)2006.4-2006.9,阿德莱德联(租借)2006.10-2006.11,达伽马2007.2-2008.4职业生涯数据:[职业生涯数据:1000+球,正式比赛:993场/771球]赛季俱乐部出场进球国家联赛等级排名2008 瓦斯科达伽马2007 瓦斯科达伽马2006/07 阿德莱德联 4 1 澳大利亚 1 22006 迈阿密熔合23 18 美国2005 瓦斯科达伽马31 22 巴西 1 122004 弗卢米嫩塞13 5 巴西 1 92003 弗卢米嫩塞21 13 巴西 1 192002/03 萨德 3 0 卡塔尔2002 弗卢米嫩塞22 15 巴西2001 瓦斯科达伽马18 212000 瓦斯科达伽马20 141999 弗拉门戈19 121998 弗拉门戈20 141997/98 瓦伦西亚 6 1 西班牙 1 91996/97 瓦伦西亚 5 4 西班牙 1 101996 弗拉门戈30 231995 弗拉门戈16 81994/95 巴塞罗那13 4 西班牙 1 41993/94 巴塞罗那33 30 西班牙 1 11992/93 埃因霍温26 22 荷兰 1 21991/92 埃因霍温14 9 荷兰 1 11990/91 埃因霍温25 25 荷兰 1 11989/90 埃因霍温20 23 荷兰 1 21988/89 埃因霍温24 19 荷兰 1 11988 瓦斯科达伽马41 321987 瓦斯科达伽马40 321986 瓦斯科达伽马32 91985 瓦斯科达伽马28 11荣誉:2次巴西里约州冠军(1987、88)、2次荷兰联赛冠军、3次荷兰杯冠军(1988-92)、1次西甲冠军(1994)、1次世界杯冠军(1994)、2次美洲杯冠军(1997、99)、1次巴西全国冠军(2000);1次世界杯最佳球员(1994)、1次世界足球先生(1994)、1次奥运会最佳射手(1988)、1次世俱杯(2000)、2次美洲杯最佳射手、2次南美足球先生。

Chap008金融机构管理课后题答案

Chapter EightInterest Rate Risk IChapter OutlineIntroductionThe Central Bank and Interest Rate RiskThe Repricing ModelRate-Sensitive AssetsRate-Sensitive LiabilitiesEqual Changes in Rates on RSAs and RSLsUnequal Changes in Rates on RSAs and RSLsWeaknesses of the Repricing ModelMarket Value EffectsOveraggregationThe Problem of RunoffsCash Flows from Off-Balance Sheet ActivitiesThe Maturity ModelThe Maturity Model with a Portfolio of Assets and Liabilities Weakness of the Maturity ModelSummaryAppendix 8A: Term Structure of Interest RatesUnbiased Expectations TheoryLiquidity Premium Theory Market Segmentation TheorySolutions for End-of-Chapter Questions and Problems: Chapter Eight1. What was the impact on interest rates of the borrowed reserves targetingregime used by the Federal Reserve from 1982 to 1993The volatility of interest rates was significantly lower than under the nonborrowed reserves target regime used in the three years immediately prior to 1982. Figure 8-1 indicates that both the level and volatility of interest rates declined even further after 1993 when the Fed decided that it would target primarily the fed funds rate as a guide for monetary policy.2. How has the increased level of financial market integration affectedinterest ratesIncreased financial market integration, or globalization, increases the speed with which interest rate changes and volatility are transmitted among countries. The result of this quickening of global economic adjustment is to increase the difficulty and uncertainty faced by the Federal Reserve as it attempts to manage economic activity within the U.S. Further, because FIs have become increasingly more global in their activities, any change in interest rate levels or volatility caused by Federal Reserve actions more quickly creates additional interest rate risk issues for these companies.3. What is the repricing gap In using this model to evaluate interest raterisk, what is meant by rate sensitivity On what financial performance variable does the repricing model focus Explain.The repricing gap is a measure of the difference between the dollar value of assets that will reprice and the dollar value of liabilities that will reprice within a specific time period, where reprice means the potential to receive a new interest rate. Rate sensitivity represents the time interval where repricing can occur. The model focuses on the potential changes in the net interest income variable. In effect, if interest rates change, interest income and interest expense will change as the various assets and liabilities are repriced, that is, receive new interest rates.4. What is a maturity bucket in the repricing model Why is the length oftime selected for repricing assets and liabilities important when using the repricing modelThe maturity bucket is the time window over which the dollar amounts of assets and liabilities are measured. The length of the repricing period determines which of the securities in a portfolio are rate-sensitive. The longer the repricing period, the more securities either mature or need to be repriced, and, therefore, the more the interest rate exposure. An excessively short repricing period omits consideration of the interest rate risk exposure of assets and liabilities are that repriced in the period immediately following the end of the repricing period. That is, it understates the rate sensitivity of the balance sheet. An excessively long repricing period includes many securities that are repriced at different times within the repricing period, thereby overstating the rate sensitivity of the balance sheet.5. Calculate the repricing gap and the impact on net interest income of a 1percent increase in interest rates for each of the following positions:Rate-sensitive assets = $200 million. Rate-sensitive liabilities =$100 million.Repricing gap = RSA - RSL = $200 - $100 million = +$100 million.NII = ($100 million)(.01) = +$ million, or $1,000,000.Rate-sensitive assets = $100 million. Rate-sensitive liabilities =$150 million.Repricing gap = RSA - RSL = $100 - $150 million = -$50 million.NII = (-$50 million)(.01) = -$ million, or -$500,000.Rate-sensitive assets = $150 million. Rate-sensitive liabilities =$140 million.Repricing gap = RSA - RSL = $150 - $140 million = +$10 million.NII = ($10 million)(.01) = +$ million, or $100,000.a. Calculate the impact on net interest income on each of the abovesituations assuming a 1 percent decrease in interest rates.NII = ($100 million) = -$ million, or -$1,000,000.NII = (-$50 million) = +$ million, or $500,000.NII = ($10 million) = -$ million, or -$100,000.b. What conclusion can you draw about the repricing model from theseresultsThe FIs in parts (1) and (3) are exposed to interest rate declines(positive repricing gap) while the FI in part (2) is exposed to interest rate increases. The FI in part (3) has the lowest interest rate riskexposure since the absolute value of the repricing gap is the lowest,while the opposite is true for part (1).6. What are the reasons for not including demand deposits as rate-sensitiveliabilities in the repricing analysis for a commercial bank What is the subtle, but potentially strong, reason for including demand deposits inthe total of rate-sensitive liabilities Can the same argument be madefor passbook savings accountsThe regulatory rate available on demand deposit accounts is zero. Although many banks are able to offer NOW accounts on which interest can be paid, this interest rate seldom is changed and thus the accounts are not really sensitive. However, demand deposit accounts do pay implicit interest in the form of not charging fully for checking and other services. Further, when market interest rates rise, customers draw down their DDAs, which may cause the bank to use higher cost sources of funds. The same or similar arguments can be made for passbook savings accounts.7. What is the gap ratio What is the value of this ratio to interest raterisk managers and regulatorsThe gap ratio is the ratio of the cumulative gap position to the total assets of the bank. The cumulative gap position is the sum of the individual gaps over several time buckets. The value of this ratio is that it tells the direction of the interest rate exposure and the scale of that exposure relative to the size of the bank.8. Which of the following assets or liabilities fit the one-year rate or repricing sensitivity test91-day . Treasury bills Yes1-year . Treasury notes Yes20-year . Treasury bonds No20-year floating-rate corporate bonds with annual repricing Yes30-year floating-rate mortgages with repricing every two years No30-year floating-rate mortgages with repricing every six months YesOvernight fed funds Yes9-month fixed rate CDs Yes1-year fixed-rate CDs Yes5-year floating-rate CDs with annual repricing YesCommon stock No9. Consider the following balance sheet for WatchoverU Savings, Inc. (in millions):Assets Liabilities and EquityFloating-rate mortgages Demand deposits(currently 10% annually) $50 (currently 6% annually) $7030-year fixed-rate loans Time deposits(currently 7% annually) $50 (currently 6% annually $20Equity $10 Total Assets $100 Total Liabilities & Equity$100a. What is WatchoverU’s expected net interest income at year-endCurrent expected interest income:$5m + $3.5m = $8.5m.Expected interest expense: $4.2m + $1.2m = $5.4m.Expected net interest income: $8.5m - $5.4m = $3.1m.b. What will be the net interest income at year-end if interest ratesrise by 2 percentAfter the 200 basis point interest rate increase, net interest incomedeclines to:50 + 50 - 70 - 20(.06) = $9.5m - $6.8m = $2.7m, a decline of $0.4m.c. Using the cumulative repricing gap model, what is the expected netinterest income for a 2 percent increase in interest rates Wachovia’s' repricing or funding gap is $50m - $70m = -$20m. The change in net interest income using the funding gap model is (-$20m) = -$.4m.d.What will be the net interest income at year-end if interest ratesincrease 200 basis points on assets, but only 100 basis points onliabilities Is it reasonable for changes in interest rates to affectbalance sheet in an uneven manner WhyAfter the unbalanced rate increase, net interest income will be 50 +50 - 70 - 20(.06) = $9.5m - $6.1m = $3.4m, an increase of $0.3m. It isnot uncommon for interest rates to adjust in an uneven manner over two sides of the balance sheet because interest rates often do not adjust solely because of market pressures. In many cases the changes areaffected by decisions of management. Thus you can see the difference between this answer and the answer for part a.10. What are some of the weakness of the repricing model How have largebanks solved the problem of choosing the optimal time period forrepricing What is runoff cash flow, and how does this amount affect the repricing model’s analysisThe repricing model has four general weaknesses:(1) It ignores market value effects.(2) It does not take into account the fact that the dollar value of ratesensitive assets and liabilities within a bucket are not similar. Thus, if assets, on average, are repriced earlier in the bucket thanliabilities, and if interest rates fall, FIs are subject to reinvestment risks.(3) It ignores the problem of runoffs, that is, that some assets are prepaidand some liabilities are withdrawn before the maturity date.(4) It ignores income generated from off-balance-sheet activities.Large banks are able to reprice securities every day using their own internal models so reinvestment and repricing risks can be estimated for each day ofthe year.Runoff cash flow reflects the assets that are repaid before maturity and the liabilities that are withdrawn unsuspectedly. To the extent that either of these amounts is significantly greater than expected, the estimated interest rate sensitivity of the bank will be in error.11. Use the following information about a hypothetical government securitydealer named . Jorgan. Market yields are in parenthesis, and amounts are in millions.Assets Liabilities and EquityCash $10 Overnight Repos $1701 month T-bills %) 75 Subordinated debt3 month T-bills %) 75 7-year fixed rate % 1502 year T-notes %) 508 year T-notes %) 1005 year munis (floating rate)% reset every 6 months) 25 Equity 15 Total Assets $335 Total Liabilities & Equity$335a. What is the funding or repricing gap if the planning period is 30 days91 days 2 years Recall that cash is a noninterest-earning asset.Funding or repricing gap using a 30-day planning period = 75 - 170 = -$95 million.Funding gap using a 91-day planning period = (75 + 75) - 170 = -$20 million.Funding gap using a two-year planning period = (75 + 75 + 50 + 25) - 170 = +$55 million.b. What is the impact over the next 30 days on net interest income if allinterest rates rise 50 basis points Decrease 75 basis pointsNet interest income will decline by $475,000. NII = FG(R) = -95(.005) = $0.475m.Net interest income will increase by $712,500. NII = FG(R)= -95(.0075) = $0.7125m.c.The following one-year runoffs are expected: $10 million for two-yearT-notes, and $20 million for eight-year T-notes. What is the one-year repricing gapFunding or repricing gap over the 1-year planning period = (75 + 75 + 10 + 20 + 25) - 170 = +$35 million.d. If runoffs are considered, what is the effect on net interest incomeat year-end if interest rates rise 50 basis points Decrease 75 basispointsNet interest income will increase by $175,000. NII = FG(R) = 35 = $0.175m.Net interest income will decrease by $262,500, NII = FG(R) = 35 = -$0.2625m.12. What is the difference between book value accounting and market valueaccounting How do interest rate changes affect the value of bank assets and liabilities under the two methods What is marking to marketBook value accounting reports assets and liabilities at the original issue values. Current market values may be different from book values because they reflect current market conditions, such as interest rates or prices. This is especially a problem if an asset or liability has to be liquidated immediately. If the asset or liability is held until maturity, then the reporting of book values does not pose a problem.For an FI, a major factor affecting asset and liability values is interestrate changes. If interest rates increase, the value of both loans (assets) and deposits and debt (liabilities) fall. If assets and liabilities are held until maturity, it does not affect the book valuation of the FI. However, ifdeposits or loans have to be refinanced, then market value accounting presents a better picture of the condition of the FI.The process by which changes in the economic value of assets and liabilities are accounted is called marking to market. The changes can be beneficial as well as detrimental to the total economic health of the FI.13. Why is it important to use market values as opposed to book values whenevaluating the net worth of an FI What are some of the advantages ofusing book values as opposed to market valuesBook values represent historical costs of securities purchased, loans made, and liabilities sold. They do not reflect current values as determined by market values. Effective financial decision-making requires up-to-date information that incorporates current expectations about future events. Market values provide the best estimate of the present condition of an FI and serve as an effective signal to managers for future strategies.Book values are clearly measured and not subject to valuation errors, unlike market values. Moreover, if the FI intends to hold the security until maturity, then the security's current liquidation value will not be relevant. That is, the paper gains and losses resulting from market value changes will never be realized if the FI holds the security until maturity. Thus, the changes in market value will not impact the FI's profitability unless the security is sold prior to maturity.14. Consider a $1,000 bond with a fixed-rate 10 percent annual coupon (Cpn %)and a maturity (N) of 10 years. The bond currently is trading to amarket yield to maturity (YTM) of 10 percent. Complete the followingtable.From Par, $ From Par, %N Cpn % YTM Price Change in Price Change in Price8 10% 9% $1, $ %9 10% 9% $1, $ %10 10% 9% $1, $ %10 10% 10% $1,10 10% 11% $ -$ %11 10% 11% $ -$ %12 10% 11% $ -$ %Use this information to verify the principles of interest rate-pricerelationships for fixed-rate financial assets.Rule One: Interest rates and prices of fixed-rate financial assets move inversely. See the change in price from $1,000 to $ for the change in interest rates from 10 percent to 11 percent, or from $1,000 to $1, when rates change from 10 percent to 9 percent.Rule Two: The longer is the maturity of a fixed-income financial asset, the greater is the change in price for a given change in interest rates.A change in rates from 10 percent to 11 percent has caused the 10-yearbond to decrease in value $, but the 11-year bond will decrease in value $, and the 12-year bond will decrease $.Rule Three: The change in value of longer-term fixed-rate financialassets increases at a decreasing rate. For the increase in rates from 10 percent to 11 percent, the difference in the change in price between the 10-year and 11-year assets is $, while the difference in the change in price between the 11-year and 12-year assets is $.Rule Four: Although not mentioned in the text, for a given percentage () change in interest rates, the increase in price for a decrease in ratesis greater than the decrease in value for an increase in rates. Thus for rates decreasing from 10 percent to 9 percent, the 10-year bond increases $. But for rates increasing from 10 percent to 11 percent, the 10-year bond decreases $.15. Consider a 12-year, 12 percent annual coupon bond with a required returnof 10 percent. The bond has a face value of $1,000.a. What is the price of the bondPV = $120*PVIFAi=10%,n=12 + $1,000*PVIFi=10%,n=12= $1,b. If interest rates rise to 11 percent, what is the price of the bondPV = $120*PVIFAi=11%,n=12 + $1,000*PVIFi=11%,n=12= $1,c. What has been the percentage change in priceP = ($1, - $1,/$1, = or – percent.d. Repeat parts (a), (b), and (c) for a 16-year bond.PV = $120*PVIFAi=10%,n=16 + $1,000*PVIFi=10%,n=16= $1,PV = $120*PVIFAi=11%,n=16 + $1,000*PVIFi=11%,n=16= $1,P = ($1, - $1,/$1, = or – percent.e. What do the respective changes in bond prices indicateFor the same change in interest rates, longer-term fixed-rate assets have a greater change in price.16. Consider a five-year, 15 percent annual coupon bond with a face value of$1,000. The bond is trading at a market yield to maturity of 12 percent.a. What is the price of the bondPV = $150*PVIFAi=12%,n=5 + $1,000*PVIFi=12%,n=5= $1,b. If the market yield to maturity increases 1 percent, what will be thebond’s new pricePV = $150*PVIFAi=13%,n=5 + $1,000*PVIFi=13%,n=5= $1,c. Using your answers to parts (a) and (b), what is the percentage changein the bond’s price as a result of the 1 percent increase in interest ratesP = ($1, - $1,/$1, = or – percent.d. Repeat parts (b) and (c) assuming a 1 percent decrease in interestrates.PV = $150*PVIFAi=11%,n=5 + $1,000*PVIFi=11%,n=5= $1,P = ($1, - $1,/$1, = or percente. What do the differences in your answers indicate about the rate-pricerelationships of fixed-rate assetsFor a given percentage change in interest rates, the absolute value of the increase in price caused by a decrease in rates is greater than the absolute value of the decrease in price caused by an increase in rates.17. What is maturity gap How can the maturity model be used to immunize anFI’s portfolio What is the critical requirement to allow maturitymatching to have some success in immunizing the balance sheet of an FIMaturity gap is the difference between the average maturity of assets and liabilities. If the maturity gap is zero, it is possible to immunize the portfolio, so that changes in interest rates will result in equal but offsetting changes in the value of assets and liabilities and net interest income. Thus, if interest rates increase (decrease), the fall (rise) in the value of the assets will be offset by a perfect fall (rise) in the value of the liabilities. The critical assumption is that the timing of the cash flows on the assets and liabilities must be the same.18. Nearby Bank has the following balance sheet (in millions):Assets Liabilities and EquityCash $60 Demand deposits $1405-year treasury notes $60 1-year Certificates of Deposit $160 30-year mortgages $200 Equity $20Total Assets $320 Total Liabilities and Equity$320What is the maturity gap for Nearby Bank Is Nearby Bank more exposed to an increase or decrease in interest rates Explain whyM A = [0*60 + 5*60 + 200*30]/320 = years, and ML= [0*140 + 1*160]/300 = .Therefore the maturity gap = MGAP = – = years. Nearby bank is exposed toan increase in interest rates. If rates rise, the value of assets will decrease much more than the value of liabilities.19. County Bank has the following market value balance sheet (in millions,annual rates):Assets Liabilities and EquityCash $20 Demand deposits $10015-year commercial loan @ 10% 5-year CDs @ 6% interest,interest, balloon payment $160 balloon payment $21030-year Mortgages @ 8% interest, 20-year debentures @ 7% interest$120monthly amortizing $300 Equity $50Total Assets $480 Total Liabilities & Equity $480a. What is the maturity gap for County BankMA= [0*20 + 15*160 + 30*300]/480 = years.ML= [0*100 + 5*210 + 20*120]/430 = years.MGAP = – = years.b. What will be the maturity gap if the interest rates on all assets andliabilities increase by 1 percentIf interest rates increase one percent, the value and average maturity of the assets will be:Cash = $20Commercial loans = $16*PVIFAn=15, i=11% + $160*PVIFn=15,i=11%= $Mortgages = $,294*PVIFAn=360,i=9%= $MA= [0*20 + *15 + *30]/(20 + + = yearsThe value and average maturity of the liabilities will be: Demand deposits = $100CDs = $*PVIFAn=5,i=7% + $210*PVIFn=5,i=7%= $Debentures = $*PVIFAn=20,i=8% + $120*PVIFn=20,i=8%= $ML= [0*100 + 5* + 20*]/(100 + + = yearsThe maturity gap = MGAP = – = years. The maturity gap increased because the average maturity of the liabilities decreased more than the average maturity of the assets. This result occurred primarily because of the differences in the cash flow streams for the mortgages and the debentures.c. What will happen to the market value of the equityThe market value of the assets has decreased from $480 to $, or $. The market value of the liabilities has decreased from $430 to $, or $. Therefore the market value of the equity will decrease by $ - $ = $, or percent.d. If interest rates increased by 2 percent, would the bank be solvent The value of the assets would decrease to $, and the value of the liabilities would decrease to $. Therefore the value of the equity would be $. Although the bank remains solvent, nearly 65 percent of the equity has eroded because of the increase in interest rates.20. Given that bank balance sheets typically are accounted in book valueterms, why should the regulators or anyone else be concerned about howinterest rates affect the market values of assets and liabilitiesThe solvency of the balance sheet is an important variable to creditors of the bank. If the capital position of the bank decreases to near zero, creditors may not be willing to provide funding for the bank, and the bank may need assistance from the regulators, or may even fail. Thus any change in the market value of assets or liabilities that is caused by changes in the level of interest rate changes is of concern to regulators.21. If a bank manager is certain that interest rates were going to increasewithin the next six months, how should the bank manager adjust thebank’s maturity gap to take advantage of this antici pated increase What if the manager believed rates would fall Would your suggestedadjustments be difficult or easy to achieveWhen rates rise, the value of the longer-lived assets will fall by more the shorter-lived liabilities. If the maturity gap (or duration gap) is positive, the bank manager will want to shorten the maturity gap. If the repricing gap is negative, the manager will want to move it towards zero or positive. If rates are expected to decrease, the manager should reverse these strategies. Changing the maturity, duration, or funding gaps on the balance sheet often involves changing the mix of assets and liabilities. Attempts to make these changes may involve changes in financial strategy for the bank which may notbe easy to accomplish. Later in the text, methods of achieving the same results using derivatives will be explored.22. Consumer Bank has $20 million in cash and a $180 million loan portfolio.The assets are funded with demand deposits of $18 million, a $162 million CD and $20 million in equity. The loan portfolio has a maturity of 2years, earns interest at the annual rate of 7 percent, and is amortized monthly. The bank pays 7 percent annual interest on the CD, but theinterest will not be paid until the CD matures at the end of 2 years.a. What is the maturity gap for Consumer Bank= [0*$20 + 2*$180]/$200 = yearsMA= [0*$18 + 2*$162]/$180 = yearsMLMGAP = – = 0 years.b. Is Consumer Bank immunized or protected against changes in interestrates Why or why notIt is tempting to conclude that the bank is immunized because thematurity gap is zero. However, the cash flow stream for the loan and the cash flow stream for the CD are different because the loan amortizesmonthly and the CD pays annual interest on the CD. Thus any change in interest rates will affect the earning power of the loan more than the interest cost of the CD.c. Does Consumer Bank face interest rate risk That is, if marketinterest rates increase or decrease 1 percent, what happens to thevalue of the equityThe bank does face interest rate risk. If market rates increase 1percent, the value of the cash and demand deposits does not change.However, the value of the loan will decrease to $, and the value of the CD will fall to $. Thus the value of the equity will be ($ + $20 - $18 - $ = $. In this case the increase in interest rates causes the marketvalue of equity to increase because of the reinvestment opportunities on the loan payments.If market rates decrease 1 percent, the value of the loan increases to $, and the value of the CD increases to $. Thus the value of the equitydecreases to $.d. How can a decrease in interest rates create interest rate riskThe amortized loan payments would be reinvested at lower rates. Thuseven though interest rates have decreased, the different cash flowpatterns of the loan and the CD have caused interest rate risk.23. FI International holds seven-year Acme International bonds and two-yearBeta Corporation bonds. The Acme bonds are yielding 12 percent and the Beta bonds are yielding 14 percent under current market conditions.a. What is the weighted-average maturity of FI’s bond portfolio if 40percent is in Acme bonds and 60 percent is in Beta bondsAverage maturity = x 7 years + x 2 years = 4 yearsb. What proportion of Acme and Beta bonds should be held to have aweighted-average yield of percentLet X* + (1 - X)* = . Solving for X, we get 25 percent. In order to get an average yield of percent, we need to hold 25 percent of Acme and 75 percent of Beta.c. What will be the weighted-average maturity of the bond portfolio ifthe weighted-average yield is realizedThe average maturity of the portfolio will decrease to x 7 + x 2 = years.24. An insurance company has invested in the following fixed-incomesecurities: (a) $10,000,000 of 5-year Treasury notes paying 5 percentinterest and selling at par value, (b) $5,800,000 of 10-year bonds paying7 percent interest with a par value of $6,000,000, and (c) $6,200,000 of20-year subordinated debentures paying 9 percent interest with a parvalue of $6,000,000.a. What is the weighted-average maturity of this portfolio of assets= [5*$10 + 10*$ + 20*$]/$22 = 232/22 = yearsMAb. If interest rates change so that the yields on all of the securitiesdecrease 1 percent, how does the weighted-average maturity of theportfolio changeTo determine the weighted-average maturity of the portfolio for a rate decrease of 1 percent, the new value of each security must be determined. This calculation will require knowing the YTM of each security before the rate change.T-notes are selling at par, so the YTM = 5 percent. Therefore, the new value will bePV = $500,000*PVIFAn=5,i=4% + $10,000,000*PVIFn=5,i=4%= $10,445,182.10-year bonds: Par = $6,000,000, PV = $5,800,000, Cpn = 7 percent YTM= %. The new PV = $420,000*PVIFAn=10,i=% + $6,000,000*PVIFn=10,i=%= $6,222,290.Debentures: Par = $6,000,000, PV = $6,200,000, Cpn = 9 percentpercent. The new PV = $540,000*PVIFAn=20,i=% + $6,000,000*PVIFn=20,i==$6,820,418.The total value of the assets after the change in rates will be$23,487,890, and the weighted-average maturity will be [5*10,445,182 +10*6,222,290 + 20*6,820,418]/23,487,890 = 250,857,170/23,487,890 = years.c. Explain the changes in the maturity values if the yields increase by 1 percent.。

伍德里奇《计量经济学导论》(第5版)笔记和课后习题详解-第8章 异方差性【圣才出品】

第8章异方差性8.1复习笔记一、异方差性对OLS 所造成的影响1.异方差性对无偏性的影响多元线性回归模型表达式为:01122k k y x x x uββββ=+++⋅⋅⋅+异方差性并不会导致j β的OLS 估计量出现偏误或产生不一致性,但诸如省略一个重要变量之类的情况出现则具有这种影响。

2.异方差性对拟合优度的影响对拟合优度指标R 2和2R 的解释不受异方差性的影响。

通常的R 2和调整2R 都是估计总体R 2的不同方法,而总体R 2无非就是221/u y σσ-(因为2/11/SSR SSR n R SST SST n=-=-),其中2u σ是总体误差方差,2y σ是y 的总体方差。

关键是,由于总体R 2中这两个方差都是无条件方差,所以总体R 2不受()1Var | k u x x ⋅⋅⋅,,中出现异方差性的影响。

无论()1Var | k u x x ⋅⋅⋅,,是否为常数,SSR/n 都一致地估计了2u σ,SSR/n 也一致地估计了2y σ。

当使用自由度调整时,依然如此。

因此,无论同方差假定是否成立,R 2和2R 都一致地估计了总体R 2。

3.估计量的方差()ˆVar jβ在没有同方差假定的情况下,估计量的方差ˆ()jVar β是有偏的。

由于OLS 标准误直接以这些方差为基础,所以它们都不能用来构造置信区间和t 统计量。

4.对统计检验的影响在出现异方差性的情况下,在高斯-马尔可夫假定下用来检验假设的统计量都不再成立。

(1)在出现异方差性时,通常普通最小二乘法的t 统计量就不具有t 分布,使用大样本容量也不能解决这个问题。

(2)F 统计量也不再是F 分布。

(3)LM 统计量也不服从渐近2χ分布。

二、OLS 估计后的异方差—稳健推断1.单个自变量模型01i i iy x u ββ=++假定前4个高斯-马尔可夫假定成立。

如果误差包含异方差性,那么()2Var |i i iu x σ=其中,给2σ加上下标i,表示误差方差2i σ不再是固定的值,而是随着x i 的不同而不同。

CorporateSocialResponsibilityandAccesstoFinance

Copyright © 2011 by Beiting Cheng, Ioannis Ioannou, and George SerafeimWorking papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of workingCorporate Social Responsibilityand Access to FinanceBeiting Cheng Ioannis Ioannou George SerafeimWorking Paper11-130CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY AND ACCESS TO FINANCEBeiting ChengHarvard Business SchoolIoannis IoannouLondon Business SchoolGeorge SerafeimHarvard Business SchoolMay 18th, 2011AbstractIn this paper, we investigate whether superior performance on corporate social responsibility (CSR) strategies leads to better access to finance. We hypothesize that better access to finance can be attributed to reduced agency costs, due to enhanced stakeholder engagement through CSR and reduced informational asymmetries, due to increased transparency through non-financial reporting. Using a large cross-section of firms, we show that firms with better CSR performance face significantly lower capital constraints. The results are confirmed using an instrumental variables and a simultaneous equations approach. Finally, we find that the relation is primarily driven by social and environmental performance, rather than corporate governance. Keywords: corporate social responsibility, sustainability, capital constraints, ESG (environmental, social, governance) performanceI.INTRODUCTIONIn recent decades, a growing number of academics as well as top executives have been allocating a considerable amount of time and resources to Corporate Social Responsibility1 (CSR) strategies. According to the latest UN Global Compact – Accenture CEO study2 (2010), 93 percent of the 766 participant CEOs from all over the world declared CSR as an “important” or “very important” factor for their organizations’ future success. On the demand side, consumers are becoming increasingly aware of firms’ CSR performance: a recent 5,000-people survey3 by Edelman4revealed that nearly two thirds of those interviewed cited “transparent and honest business practices” as the most important driver of a firm’s reputation. Although CSR has received such a great amount of attention, a fundamental question still remaining unanswered is whether CSR leads to value creation, and if so, in what ways? The extant research so far has failed to give a definitive answer (Margolis and Walsh, 2003). In this paper, we examine one specific mechanism through which CSR may lead to better long-run performance: by lowering the constraints that the firm is facing when accessing funds to finance operations and undertake strategic projects.To date, many studies have investigated the link between CSR and financial performance, and have found rather conflicting results5. According to McWilliams and Siegel (2000), conflicting results were due to the studies’ “several important theoretical and empirical 1 Here, we follow a long list of studies (e.g. Carroll, 1979; Wolfe and Aupperle, 1991; Waddock and Graves, 1997; Hillman and Keim, 2001; Waldman et al., 2006) in defining corporate social responsibility as: “a business organization’s configuration of principles of social responsibility, processes of social responsiveness, and policies, programs, and observable outcomes as they relate to the firm’s social relationships” (Wood, 1991: p.693).2 “A New Era of Sustainability. UN Global Compact-Accenture CEO Study 2010” last accessed July 28th, 2010 at: (https:///sustainability/research_and_insights/Pages/A-New-Era-of-Sustainability.aspx)3Mckinght, L., 2011. “Companies that do good also do well”, Market Watch, The Wall Street Journal (Digital Network), last accessed April 11th, 2011 at: /story/companies-that-do-good-also-do-well-2011-03-234 Edelman is a leading independent global PR firm that has been providing public relations counsel and strategic communications services for more than 50 years. /5 Margolis and Walsh (2003) and Orlitzky, Schidt and Rynes (2003) provide comprehensive reviews of the extant literature.limitations” (p.603). Others have argued that the studies suffered from “stakeholder mismatching” (Wood and Jones, 1995), the neglect of “contingency factors” (e.g. Ullmann, 1985), “measurement errors” (e.g. Waddock and Graves, 1997) and, omitted variable bias (Aupperle, Carrol and Hatfield, 1985; Cochran and Wood, 1984; Ullman, 1985).In this paper, we focus on the impact of CSR on the firm’s capital constraints. By “capital constraints” we refer to market frictions6that may prevent a firm from funding all desired investments. This inability to obtain finance may be “due to credit constraints or inability to borrow, inability to issue equity, dependence on bank loans, or illiquidity of assets” (Lamont et al., 2001). Prior studies have suggested that capital constraints play an important role in strategic decision-making, since they directly affect the firm’s ability to undertake major investment decisions and, also influence the firm’s capital structure choices (e.g., Hennessy and Whited, 2007). Moreover, past research has found that capital constraints are associated with a firm’s subsequent stock returns (e.g. Lamont et al., 2001).There are several reasons why investors would pay attention to a firm’s CSR strategies. First, firm activities that may affect7 long-term financial performance are taken into account by market participants when assessing a firm’s long-run value-creating potential (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2010a; Groysberg et al., 2011; Previts and Bricker, 1994). Moreover, a growing number of investors use CSR information as an important criterion for their investment decisions – what is currently known as “socially responsible investing” (SRI). For example, in 2007 mutual funds that invested in socially responsible firms had assets under management of more than $2.5 and $2 trillion dollars in the United States and Europe respectively. In Canada, Japan 6Consistent with prior literature in corporate finance (e.g. Lamont et al., 2001), we do not use the term to mean financial distress, economic distress or bankruptcy risk.7 Margolis and Walsh (2003) perform a meta-analysis of the CSR studies and find that the link between CSR and financial performance is small, albeit it is positive and statistically significant.and Australia, the corresponding numbers were $500, $100 and $64 billion respectively (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2010a). Total assets under management by socially responsible investors have grown considerably in the last ten years in countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada. In addition, the emergence of several CSR rankings and ratings firms (such as Thomson Reuters ASSET4 and KLD), the widespread dissemination of data on ESG performance by Bloomberg terminals, as well as the formation of teams to analyze CSR data within large banks such as J.P. Morgan Chase and Deutsche Bank,8highlight the growing demand and subsequent increasing use of CSR information. Furthermore, projects like the Enhanced Analyst Initiative9(EAI) that allocate a minimum of 5 percent of trading commissions to brokers that integrate analysis of CSR data into their mainstream research has further increased investor incentives to incorporate CSR data in their analysis10. Finally, in several countries around the world, governments have adopted laws and regulations that mandate CSR reporting (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2011) as part of efforts to increase the availability of CSR data and bring transparency around nonfinancial performance.The thesis of this paper is that firms with better CSR performance face fewer capital constraints. This is due to several reasons. First, superior CSR performance is directly linked to better stakeholder engagement, which in turn implies that contracting with stakeholders takes place on the basis of mutual trust and cooperation (Jones, 1995). Furthermore, as Jones (1995) argues, “because ethical solutions to commitment problems are more efficient than mechanisms designed to curb opportunism, it follows that firms that contract with their stakeholders on the basis of mutual trust and cooperation […] will experience reduced agency costs, transaction costs8 Cobley, M. 2009. “Banks Cut Back Analysis on Social Responsibility”, The Wall Street Journal, June 11th 2009.9 An initiative established by institutional investors with assets totaling more than US$1 trillion.10 “Universal Ownership: Exploring Opportunities and Challenges”, Conference Report, April 2006, Saint Mary’s College of California, Center for the study of Fiduciary Capitalism and Mercer Investment Consulting.and costs associated with team production” (Foo, 2007). In other words, superior stakeholder engagement may directly limit the likelihood of short-term opportunistic behavior (Benabou and Tirole, 2010; Ioannou and Serafeim, 2011) by reducing overall contracting costs (Jones, 2005).Moreover, firms with better CSR performance are more likely to disclose their CSR activities to the market (Dhaliwal et al., 2011) to signal their long-term focus and differentiate themselves (Spence, 1973; Benabou and Tirole, 2010). In turn, reporting of CSR activities: a) increases transparency around the social and environmental impact of companies, and their governance structure and b) may change internal management practices by creating incentives for companies to better manage their relationships with key stakeholders such as employees, investors, customers, suppliers, regulators, and civil society (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2011). Therefore, the increased availability of data about the firm reduces informational asymmetries between the firm and investors (e.g. Botosan, 1997; Khurana and Raman, 2004; Hail and Leuz, 2006; Chen et al., 2009; El Ghoul et al., 2010), leading to lower capital constraints (Hubbard, 1998).In fact, the rapid growth of available capital through SRI funds in recent years (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2010a), and the corresponding expansion of potential financiers that base their investment decisions on non-financial information (Kapstein, 2001), may well be partially due to the increased transparency and an endorsement of the long-term orientation that firms with superior CSR performance adopt. In sum, because of lower agency costs through stakeholder engagement and increased transparency through nonfinancial reporting, we predict that a firm with superior CSR performance will face lower capital constraints.To investigate the impact that CSR has on capital constraints, we use data from Thompson Reuters ASSET411for 2,439 publicly listed firms during the period 2002 to 2009. Thompson Reuters ASSET4 rates firms’ performance on three dimensions (“pillars”) of CSR: social, environmental and corporate governance. The dependent variable of interest is the “KZ index”, first advocated by Kaplan and Zingales (1997) and subsequently used extensively by scholars (e.g. Lamont et al., 2001; Baker et al., 2003; Almeida et al., 2004; Bakke and Whited, 2010; Hong et al., 2011) as a measure of capital constraints.The results confirm that firms with better CSR performance face lower capital constraints. We test the robustness of the results, by substituting the KZ index with an indicator variable for stock repurchase activity, to proxy for capital constraints, and we find similar results. Importantly, the results remain unchanged when we implement an instrumental variables approach and a simultaneous equations model, mitigating potential endogeneity concerns or correlated omitted variables issues, and providing evidence for a causal argument. Finally, we disaggregate CSR performance into its three components to gain insight as to which pillars have the greatest impact on capital constraints. We find that the result is driven primarily by social and environmental performance.This paper contributes to both the theoretical and empirical literature on CSR. Although many studies have explored the link between CSR and value creation, few have focused on the crucial role that capital markets play as a mechanism through which CSR may translate into tangible benefits for firms (e.g. Derwall and Verwijmeren, 2007; Goss and Roberts, 2011; Sharfman and Fernando, 2008; Chava, 2010). We contribute to this literature by showing the impact that CSR has on the firm’s ability to access finance in capital markets.11ASSET 4 is widely used by investors as a source for environmental, social and governance performance data. Some of the most prominent investment houses in the world, such as BlackRock, use the ASSET 4 data. See: /content/financial/pdf/491304/2011_04_blackrock_appoints_esg.pdfFurthermore, this study sheds light on the core strategic problem: understanding persistent performance heterogeneity across firms in the long-run. We argue that differential ability across firms to implement CSR strategies, results in significant variation in terms of CSR performance which in turn, is directly linked to the firm’s ability to access capital. Differential access to capital implies variation in the ability of firms to finance major strategic investments, leading to direct performance implications in the long-run. In other words, by understanding the consequences of variability in CSR strategies we contribute towards understanding performance heterogeneity across firms in the long-run.The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section II discusses the prior literature linking CSR to value creation, and prior literature linking capital constraints with firm performance. Section III presents the theoretical argument and derives our main hypothesis. Section IV presents the data sources and the empirical methods. Section V presents the results and section VI provides a discussion of the findings, the limitations of the study and concludes.II.PRIOR LITERATURECorporate Social Responsibility and Firm PerformanceMany studies have investigated the link between CSR and financial performance, both from a theoretical as well as from an empirical standpoint. On the one hand, prior theoretical work rooted in neoclassical economics argued that CSR unnecessarily raises a firm’s costs, and thus, puts the firm in a position of competitive disadvantage vis-à-vis competitors (Friedman, 1970; Aupperle et al., 1985; McWilliams and Siegel, 1997; Jensen, 2002). Other studies have argued that employing valuable firm resources to engage in socially responsible strategies results insignificant managerial benefits rather than financial benefits to the firm’s shareholders (Brammer and Millington, 2008).On the other hand, several scholars have argued that CSR may have a positive impact on firms by providing better access to valuable resources (Cochran and Wood, 1984; Waddock and Graves, 1997), attracting and retaining higher quality employees (Turban and Greening, 1996; Greening and Turban, 2000), better marketing for products and services (Moskowitz, 1972; Fombrun, 1996), creating unforeseen opportunities (Fombrun et al., 2000), and gaining social legitimacy (Hawn et al., 2011). Furthermore, others have argued that CSR may function in similar ways as advertising does and therefore, increase overall demand for products and services and/or reduce consumer price sensitivity (Dorfman and Steiner, 1954; Navarro, 1988; Sen and Bhattacharya, 2001; Milgrom and Roberts, 1986) as well as enable the firm to develop intangible resources (Gardberg and Fomburn, 2006; Hull and Rothernberg, 2008; Waddock and Graves, 1997). Within stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984; Freeman et al., 2007; Freeman et al., 2010), which suggests that CSR is synonymous to effective management of multiple stakeholder relationships, scholars have argued that identifying and managing ties with key stakeholders can mitigate the likelihood of negative regulatory, legislative or fiscal action (Freeman, 1984; Berman et al., 1999; Hillman and Keim, 2001), attract socially conscious consumers (Hillman and Keim, 2001), or attract financial resources from socially responsible investors (Kapstein, 2001). CSR may also lead to value creation by protecting and enhancing corporate reputation (Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Fombrun, 2005; Freeman et al., 2007).Empirical examinations of the link between CSR and corporate financial performance have resulted in contradictory findings, ranging from a positive to a negative relation, to a U-shaped or even to an inverse-U shaped relation (Margolis and Walsh, 2003). According toMcWilliams and Siegel (2000), conflicting results were due to “several important theoretical and empirical limitations” (p.603) of prior studies; others have argued that prior work suffered from “stakeholder mismatching” (Wood and Jones, 1995), the neglect of “contingency factors” (e.g. Ullmann, 1985), “measurement errors” (e.g. Waddock and Graves, 1997) and, omitted variable bias (Aupperle et al.,, 1985; Cochran and Wood, 1984; Ullman, 1985).In this paper, we shed light on the link between CSR and value creation, by focusing on the role of capital markets, as a specific mechanism through which CSR strategies may translate into economic value in the long run. More specifically, we argue that better CSR performance leads to lower capital constraints, which in turn has a positive impact on performance. Accordingly, the following subsection briefly reviews prior literature on the link between capital constraints and firm performance.Capital Constraints and Firm PerformanceFirms undertake strategic investments to achieve competitive advantage and thus, superior performance. The ability of the firms to undertake such investments is, in turn, directly linked to the idiosyncratic capital constraints that the firm is facing. Therefore, to understand the link between capital constraints and performance we first focus on the impact of capital constraints on investments. The theory of investment was shaped by Modigliani and Miller's seminal paper in 1958, which predicted that “a firm's financial status is irrelevant for real investment decisions in a world of perfect and complete capital markets.” The neoclassical economists derived the investment function from the firm's profit-maximizing behavior and showed that investment depends on the marginal productivity of capital, interest rate, and tax rules (Summers et. al. 1981; Mankiw 2009). However, subsequent studies in equity and debtmarkets showed that cash flow (i.e. internal funds) also plays a significant role in determining the level of investment (Blundell et. al. 1990; Whited 1992; Hubbard and Kashyap 1992). Importantly, studies have shown that financially constrained firms are more likely to reduce investments in a broad range of strategic activities (Hubbard, 1998; Campello et al., 2010), including inventory investment (Carpenter et al., 1998) and R&D expenditures (Himmelberg and Petersen, 1994; Hall and Lerner, 2010), thus significantly constraining the capacity of the firm to grow over time.Another set of studies has explored the relation between capital constraints and firm entry and exit decisions. Using entrepreneurs' personal tax-return data, Holtz-Eakin, Joulfaian, and Rosen (1994a) considered inheritance as an exogenous shock on the individual’s wealth and found that the size of the inheritance had a significant effect on the probability of becoming an entrepreneur. A follow-up paper (Holtz-Eakin, Joulfaian, and Rosen 1994b) has shown that firms founded by entrepreneurs with a larger inheritance (thus, lower capital constraints) are more likely to survive. Aghion, Fally and Scarpetta (2007) develop a similar argument by using firm-level data from 16 economies, comparing new firm entry and their post-entry growth trajectory.Another stream of literature, that considers incumbents as well as new entrants, (see Levine (2005) for a review of relevant studies) argues that capital constraints tend to affect relatively more the smaller, newer and riskier firms and channel capital to where the return is highest. As a result, countries with better-functioning financial systems that can ease such constraints, experience faster industrial growth. Given the idiosyncratic levels of constraints faced by companies of various sizes, scholars started to look at capital constraints as an explanation for why small companies pay lower dividends, become more highly levered and grow more slowly (Cooley and Quadrini 2001; Cabral and Mata 2003). For example, Carpenterand Petersen (2002) showed that a firm's asset growth is constrained by internal capital for small U.S. firms, and that firms who are able to raise more external funds enjoy a higher growth rate. Becchetti and Trovato (2002) found comparable results with a sample of Indian firms, and Desai, Foley and Forbes (2008) confirmed the same relation in a currency crisis setting. Finally, Beck et al. (2005), using survey data of a panel of global companies, documented that firm performance is vulnerable to various financial constraints and small companies are disproportionately affected due to tighter limitations. In sum, the literature to date has revealed that seeking ways to relax capital constraints is crucial to the firm-level survival and growth, the industry-level expansion and the country-level development.III.THEORETICAL DEVELOPMENTBased on neoclassical economic assumptions that postulate a flat supply curve for funds in the capital market at the level of the risk-adjusted real interest rate, Hennessy and Whited (2007) argued that “a CFO can neither create nor destroy value through his financing decisions in a world without frictions”. However, because of market imperfections such as informational asymmetries (Greenwald, Stiglitz and Weiss 1984; Myers and Majluf 1984) and agency costs (Bernanke and Gertler 1989, 1990), the supply curve for funds is effectively upward sloping rather than horizontal12 at levels of capital that exceed the firm’s net worth. In other words, when the likelihood of agency costs is high (e.g. opportunistic behavior by managers) and the capital required by the firm for investments exceeds the firm’s net worth (and it is thus uncollateralized), lenders are compensated for their information (and/or monitoring) costs by charging a higher interest rate. The greater these market frictions are, the steeper the supply curve and the higher the cost of external financing.12 For a full exposition of the model, based on neoclassical assumptions, see Hubbard (1998), p. 195-198.It follows then that adoption and implementation of firm strategies that reduce informational asymmetries or reduce the likelihood of agency costs, can shrink the wedge between the external and the internal cost of capital by making the supply curve for funds less steep. Equivalently, for a given interest rate, the firm is able to obtain higher amounts of capital. Better access to capital in turn, favorably impacts overall strategy by enabling the firm to undertake major investment decisions that otherwise would have been unprofitable, and/or by influencing the firm’s capital structure choices (e.g., Hennessy and Whited, 2007).We argue that firms with better CSR performance face lower capital constraints compared to firms with worse CSR performance. This is because superior CSR performance reduces market frictions through two mechanisms. First, superior CSR performance is the result of the firm committing to and contracting with stakeholders on the basis of mutual trust and cooperation (Jones, 1995; Andriof and Waddock, 2002). Consequently, as Jones (1995) argues, “because ethical solutions to commitment problems are more efficient than mechanisms designed to curb opportunism, it follows that firms that contract with their stakeholders on the basis of mutual trust and cooperation […] will experience reduced agency costs, transaction costs and costs associated with team production” (Foo, 2007). More specifically, such agency and transaction costs include “monitoring costs, bonding costs, search costs, warranty costs and residual losses”, according to Jones (2005, p.422). In other words, superior stakeholder engagement may not only directly limit the likelihood of short-term opportunistic behavior (Benabou and Tirole, 2010; Ioannou and Serafeim, 2011), but it also represents a more efficient form of contracting (Jones, 1995), which in turn is rewarded by the markets.In addition, firms with superior CSR performance are more likely to disclose their CSR strategies by issuing sustainability reports (Dhaliwal et al., 2011) and are more likely to provideassurance of such reports by third parties, thus increasing their credibility (Simnett et al., 2009; Benabou and Tirole, 2010). In turn, reporting and assurance of CSR activities: a) increases transparency around the long-term social and environmental impact of companies, and their governance structure and b) may change internal management practices by creating incentives for managers to better manage their relationships with key stakeholders such as employees, investors, customers, suppliers, regulators, and civil society (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2011). The increased availability of credible data about the firm’s strategies reduces informational asymmetries leading to lower capital constraints (Hubbard, 1998). Moreover, because reporting of CSR activities can also directly affect managerial practices by incentivizing managers to focus on long-term value creation, CSR reporting reduces the likelihood of agency costs in the form of short-termism.Indicatively, we note that the rapid growth of available capital for investment through SRI funds in recent years (Ioannou and Serafeim, 2010a), and the corresponding expansion of potential financiers that base their investment decisions on non-financial information (Kapstein, 2001), may well be due, to an extent, to the increased availability of information about the firm, and the resulting investor endorsement of the long-term focus that firms with superior CSR performance adopt. For example, many SRI funds use a positive screening model in which they overweight firms with good CSR performance in their portfolio, or a negative screening model in which they exclude from their investment universe companies with bad CSR performance, or an ESG integration model in which they integrate ESG data into their valuation models. Under all these investment models, SRI funds fully incorporated non-financial information in their decision making, over and above the traditional use of financial information.In sum, firms with better CSR performance are more likely to face lower capital constraints because of reduced informational asymmetries and reduced agency costs. This implies the following hypothesis:Hypothesis: Firms with better CSR performance face fewer capital constraints.IV. DATA AND EMPIRICAL METHODSDependent Variable: The KZ index of capital constraintsTo measure the level of capital constraints we follow the extant literature in corporate finance (e.g. Lamont et al. 2001; Almeida et al., 2004; Bakke and Whited, 2010) and construct the KZ index 13, using results from Kaplan and Zingales (1997). Specifically, as reported in Lamont et al. (2001), Kaplan and Zingales (1997) classify firms into discrete categories of capital constraints and then employ an ordered logit specification to relate these classifications to accounting variables. In this paper, and consistent with the prior literature, we use their regression coefficients to construct the KZ index 14 consisting of a linear combination of five accounting ratios: cash flow to total capital, the market to book ratio, debt to total capital, dividends to total capital, and cash holdings to capital. Firms with higher values of cash flow to total capital, dividends to total capital, and cash holdings to capital, and with lower values for the market to book ratio and debt to total capital are less capital constrained. The intuition behind these variables is that firms with high cash flows and large cash balances have more internal funds to deploy for new projects and as a result they are less capital constrained (Baker et al., 2003). 13 A variety of approaches including investment-cash flow sensitivities (Fazzari et al., 1988), the Whited and Wu (WW) index of constraints (Whitted and Wu, 2006) and other sorting criteria based on firm characteristics have been proposed in the literature as measures of capital constraints. Here, we use the KZ index because it has been the most prevalently used measure in the literature to date (Hadlock and Pierce, 2010). 14 More specifically we calculate the KZ index following Baker, Stein and Wurgler (2003) as: -1.002 CF it /A it-1 -39.368 DIV it /A it-1 - 1.315 C it /A it-1 + 3.139 LEV it + 0.283 Q it , where CF it /A it-1 is cash flow over lagged assets; DIV it /A it-1 is cash dividends over lagged assets; C it /A it-1 is cash balances over assets; LEV it is leverage and Q it is the market value of equity (price times shares outstanding plus assets minus the book value of equity over assets. The original odered logit regression and full exposition of the index may be found in Kaplan and Zingales (1997).。

实况足球8妖人大全

妖人大全,你可以收藏一下,我也是收藏别人的:GK皮波洛18 193 (罗马、意大利,GK一般都可以培养的不错,这里只推荐个最最BT的)CB科姆潘尼18 190 (比利时)V·博雷16 188 (比利时)拉维19 185 (索肖、法国)阿夸朗蒂18 180 (佛罗伦萨、意大利)菲利佩19 182 (阿贾克斯、巴西)沃尔夫冈20 183 (海伦芬、荷兰)德罗茨17 183 (海伦芬、荷兰)SB祖维隆17 183 (费因诺德、荷兰)麦克马霍18 191(米德斯堡、英格兰)特鲁切18 182 (埃斯特尔斯、法国、法甲)T·泰勒19 178 (马赛、尼日利亚)卡依比18 167 (伊朗)DH蒙塔里19 180 (乌迪内斯、加纳)特塞贝里德斯18 180 (帕那辛奈克斯、希腊)泰兰19 175 (费内巴切、土耳其)CH比隆17 182(巴斯蒂亚、喀麦隆、法甲)马蒂厄20 189 (索肖、法国)克鲁斯卡17 178 (多特蒙德、德国)法布雷加斯17 177 (阿森纳、西班牙)巴雷托20 178 (NEC奈梅亨、巴拉圭、荷甲)哈维·加西亚17 187 (皇家马德里、西班牙)奥斯坎17 178 (贝西克塔斯、土耳其)古尔汉17 177 (费内巴切、土耳其)SH蒂亚比18 178(欧塞尔、法国)约翰·奥布里恩17 177(自由球员、英格兰)雅希奥伊17 175 (马赛、法国)卡姆斯19 180 (马赛、法国)布努19 171 (雷恩、法国、法甲)萨维17 175 (帕尔马、意大利)M·加西亚17 178 (比利亚雷亚尔、西班牙)N·卡多索17 172 (博卡青年、阿根廷)普罗沃斯特20 185 (布鲁日、比利时)OH本·阿尔法17 177 (里昂、法国)埃德森19 180 (尼斯、巴西、法甲)皮特罗伊帕18 170 (布基那法索、弗赖堡)简加18 179 (阿尔克马尔AZ、荷兰、荷甲)梅西17 169 (巴塞罗那、阿根廷)卡尔莫纳17 186 (马洛卡、西班牙)亚当18 180 (格拉斯哥流浪者、苏格兰)CF鲁尼18 180 (曼联、英格兰)瓦兹特17 188(博尔顿、葡萄牙)巴里17 180 (马赛、塞内加尔)伊比塞维奇20 191 (巴黎圣日尔曼、波黑)M·科利19 190 (朗斯、塞内加尔、法甲)梅内兹17 180 (索肖、法国)伊尔迪斯18 191 (比勒非尔德、德国)鲍姆约翰17 177 (沙尔克04、德国)洪特17 183 (云达不莱梅、德国)切尔奇17 180 (罗马、意大利)博季诺夫18 178 (佛罗伦萨、保加利亚)巴贝尔17 185 (阿贾克斯、荷兰)阿博拉17 169 (阿贾克斯、比利时)希星18 177 (德格拉夫斯查、荷兰、荷甲)法尔范19 176 (埃因霍温、秘鲁)布劳里奥19 174 (马德里竞技、西班牙)托什21 188 (努曼西亚、西班牙)奥斯基茨17 170(皇家社会、西班牙)霍纳坦17 188 (比利亚雷亚尔、西班牙)埃希亚库21 183 (布鲁日、尼日利亚)卡维纳吉20 185 (莫斯科斯巴达、阿根廷)阿克苏17 179 (加拉塔萨雷、土耳其)马里卡18 182 (顿涅斯克矿工、罗马尼亚)梅西 18 165 (巴萨西班牙)姓名位置俱乐部国籍V。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Table 11.8MEDIAN SALARIES OF FULL PROFESSORS IN STATISTICS, 2007

Years in RankYearYear^2CountMedian

0 to 10.50.2540101478

2 to 32.56.2524102400

4 to 54.520.2535124578

6 to 76.542.2534122850

8 to 98.572.2533116900

10 to 141214473119465

15 to 191728969114900

20 to 242248454129072

25 to 3027.5756.2544131704

31 or more32102425143000

Source: American Statistical Association, "2007 Salary Report"