Infectiou Causes Impacting Reproduction

进一步重视创(烧)伤脓毒症的免疫监控

进一步重视创(烧)伤脓毒症的免疫监控创(烧)伤脓毒症(sepsis)是指来源于创(烧)伤创面或其他途径,并证实有细菌存在或有高度可疑感染灶引起的全身性炎症反应综合征(SIRS),进一步发展可导致脓毒性休克、多器官功能障碍综合征(MODS),是创(烧)伤患者死亡的独立危险因素[1]。

因此,加强对创(烧)伤脓毒症病理过程的监控和预警非常重要,有助于严重脓毒症及MODS的及时干预与治疗。

1 创(烧)伤脓毒症免疫学进展近年来创(烧)伤免疫学研究借助生物信息学技术得以迅猛发展,不仅揭示了创(烧)伤时免疫细胞基因表达的动态规律和重要信号转导通路的变化,而且提出宿主免疫防御反应可能的新模式。

同时,不断发现的新型免疫细胞及其调节途径,为创(烧)伤脓毒症的免疫监控提供新的策略。

1.1 严重创(烧)伤后机体反应模式的再认识已被广泛接受的宿主对严重创(烧)伤免疫反应模式是,机体早期出现SIRS,然后继发代偿性抗炎反应综合征(compensatory antiinflammatory responses syndrome,CARS)。

但传统的SIRS/CARS模式最近受到了挑战,美国大规模针对“损伤炎症和宿主反应合作研究项目”通过高通量生物信息学技术,对严重损伤患者和注射低剂量内毒素的志愿者进行外周血白细胞基因转录组学研究。

结果发现,机体在对创伤的基因组反应中不仅激活大量参与炎性反应、模式识别和抗感染的基因表达,同时也抑制参与抗原识别、T细胞增殖和凋亡、T细胞受体功能和NK细胞功能的基因表达。

因此提出新的创(烧)伤打击后机体免疫反应模式,即严重损伤后经典的炎症和抗炎反应,与获得性免疫反应基因表达的改变是同时而不是依次发生的[2]。

1.2 创(烧)伤后免疫功能的改变除了对创(烧)伤后机体免疫反应模式的新认识,对脓毒症免疫状态及调节机制的研究也日益加深。

创(烧)伤脓毒症病理过程中,机体固有免疫反应[包括中性粒细胞、单核/巨噬细胞、淋巴细胞、树突状细胞(dendritic cell,DC)等]障碍已倍受关注,被认为是诱发脓毒症的重要因素。

可溶性髓系细胞触发受体-1与呼吸机相关性肺炎

可溶性髓系细胞触发受体一1与呼吸机相关性肺炎徐园园许启霞刘超【摘要】髓系细胞触发受体一1是新近发现的与炎症相关的免疫球蛋白超家族成员之一,其表达于中性粒细胞、成熟的单核细胞、巨噬细胞表面。

多种细菌性成分能使细胞表面的髓系细胞触发受体一1表达增加,后者与Toll样受体协同作用。

激发炎症因子的产生。

最新的研究发现,感染过程中一种可溶性髓系细胞触发受体一1可释放进入体液,在呼吸机相关性肺炎患者的肺泡灌洗液中可溶性髓系细胞触发受体一1显.著增高,有望成为呼吸机相关性肺炎早期诊断的特异性生物指标。

【关键词】。

可溶性髓系细胞触发受体一1;呼吸机相关性肺炎;生物指标Solubletriggeringreceptorexpressedonmyeloidcells-Iandventilator-associatedpneumoniaXUYuan—yuan,XUQi~xia,LIUChao.DepartmentofRespiratoryMedicine、theFirstA{{iliatedHospitalofBengbuMedicalCollege,Bengbu233000,ChinaQrrespondingauthor:XUQi—xia,Email:xuqixiall@sina.tom[Abstract]Thetriggeringreceptorexpressedonmyeloidcells一1(TREM一1)isoneofrecentlyidentifiedimmunoglobulinsuperfamilymembersinvolvedintheinflammatoryresponse.Itexpressesonthesurfaceofneutrophils,maturemonocytesandmacrophages.ManymicrobialcomponentscanamplifyTREM一1onthesurfaceofthecellswhichattachesthecooperativefunctiontothetoll—likereceptors。

手性样品前处理

MIP-based chiral recognition sets an exotic trend in development of chiral sensors.

Analytica Chimica Acta 853 (2015) 1–18

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Analytica Chimica Acta

journal homepage: /locate/aca

Molecularly imprinted polymer based enantioselective sensing devices: A review

We present about rational design of chiral sensors as selective and sensitive devices.

GRAPArticle history: Received 20 December 2013 Received in revised form 8 June 2014 Accepted 9 June 2014 Available online 12 June 2014

ã 2014 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

* Corresponding author at: N 16/62 E-K, Sudamapur, Vinayaka, Varanasi 221010, Uttar Pradesh, India. Tel.: +91 9450239133. E-mail addresses: mahavirtiwari@, krineshtiwari@ (M.P. Tiwari).

外周炎症性疼痛刺激诱导丘脑中胶质细胞激活及细胞因子的表达

i h diea d itaa n rt aa c n ce b o lt e n s a jv n CF - d c d ifa nt emil n n r lmia h lmi u li y c mpee Fru d du a t( A)i u e n lmmaoy p i n r t. n n tr an i as

A src O j ci :T b e v ea t aino src ts n co l , n e x rsino r if mmao yc tkn s bt t a b et e o sr et ci t f t y e dmi gi a dt p e s f onl v o h v o a o a r a h e o p a t r yo ie

( 通 大 学 ,l医 学 Fra bibliotek 解 剖 学 教研 室 , 南 2附属 医院 骨 科 ,3航 海 医 学 研 究所 , 通 南 260) 20 1

摘要 目的 : 究 完 全 弗 氏佐 剂 ( F 外 周刺 激 后 , 鼠丘 脑 中 线 核 群 和 板 内 核 群 中 星形 胶 质 细 胞 标 记 物 ( A 、 胶 质 研 C A) 大 GF P)小 细胞 标 记 物 (b ) Ia 以及 细胞 因子 (L 1 , 卜 a 的表 达 变 化 。 方 法 : 转 录 聚 合 酶链 式 反 应 ( T P R , 疫 印 迹 法 , 疫 I-1 TN ) 3 逆 R -C )免 免 组织 化 学 。结 果 : 炎 症 刺 激 后 的 4h 3d和 1 , 脑 中线 核 群 和板 内核 群 中 小 胶 质 细 胞 的标 记 物 C 1 、 胞 因子 I『 在 、 4d 丘 D4细 L l, 8TNFn的 mR _ NA 和 蛋 白均 有 增 加 ; 形 胶 质 细 胞 标 记 物 G AP在 炎 症 后 的 3d和 1 , mR 星 F 4d 其 NA 和 蛋 白有 显 著 增 加 。

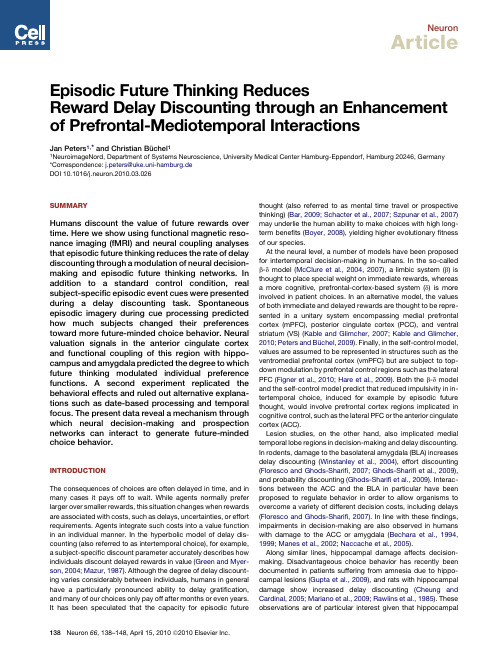

Peters (2010) Episodic Future Thinking Reduces Reward Delay Discounting

NeuronArticleEpisodic Future Thinking ReducesReward Delay Discounting through an Enhancement of Prefrontal-Mediotemporal InteractionsJan Peters1,*and Christian Bu¨chel11NeuroimageNord,Department of Systems Neuroscience,University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf,Hamburg20246,Germany*Correspondence:j.peters@uke.uni-hamburg.deDOI10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.026SUMMARYHumans discount the value of future rewards over time.Here we show using functional magnetic reso-nance imaging(fMRI)and neural coupling analyses that episodic future thinking reduces the rate of delay discounting through a modulation of neural decision-making and episodic future thinking networks.In addition to a standard control condition,real subject-specific episodic event cues were presented during a delay discounting task.Spontaneous episodic imagery during cue processing predicted how much subjects changed their preferences toward more future-minded choice behavior.Neural valuation signals in the anterior cingulate cortex and functional coupling of this region with hippo-campus and amygdala predicted the degree to which future thinking modulated individual preference functions.A second experiment replicated the behavioral effects and ruled out alternative explana-tions such as date-based processing and temporal focus.The present data reveal a mechanism through which neural decision-making and prospection networks can interact to generate future-minded choice behavior.INTRODUCTIONThe consequences of choices are often delayed in time,and in many cases it pays off to wait.While agents normally prefer larger over smaller rewards,this situation changes when rewards are associated with costs,such as delays,uncertainties,or effort requirements.Agents integrate such costs into a value function in an individual manner.In the hyperbolic model of delay dis-counting(also referred to as intertemporal choice),for example, a subject-specific discount parameter accurately describes how individuals discount delayed rewards in value(Green and Myer-son,2004;Mazur,1987).Although the degree of delay discount-ing varies considerably between individuals,humans in general have a particularly pronounced ability to delay gratification, and many of our choices only pay off after months or even years. It has been speculated that the capacity for episodic future thought(also referred to as mental time travel or prospective thinking)(Bar,2009;Schacter et al.,2007;Szpunar et al.,2007) may underlie the human ability to make choices with high long-term benefits(Boyer,2008),yielding higher evolutionaryfitness of our species.At the neural level,a number of models have been proposed for intertemporal decision-making in humans.In the so-called b-d model(McClure et al.,2004,2007),a limbic system(b)is thought to place special weight on immediate rewards,whereas a more cognitive,prefrontal-cortex-based system(d)is more involved in patient choices.In an alternative model,the values of both immediate and delayed rewards are thought to be repre-sented in a unitary system encompassing medial prefrontal cortex(mPFC),posterior cingulate cortex(PCC),and ventral striatum(VS)(Kable and Glimcher,2007;Kable and Glimcher, 2010;Peters and Bu¨chel,2009).Finally,in the self-control model, values are assumed to be represented in structures such as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex(vmPFC)but are subject to top-down modulation by prefrontal control regions such as the lateral PFC(Figner et al.,2010;Hare et al.,2009).Both the b-d model and the self-control model predict that reduced impulsivity in in-tertemporal choice,induced for example by episodic future thought,would involve prefrontal cortex regions implicated in cognitive control,such as the lateral PFC or the anterior cingulate cortex(ACC).Lesion studies,on the other hand,also implicated medial temporal lobe regions in decision-making and delay discounting. In rodents,damage to the basolateral amygdala(BLA)increases delay discounting(Winstanley et al.,2004),effort discounting (Floresco and Ghods-Sharifi,2007;Ghods-Sharifiet al.,2009), and probability discounting(Ghods-Sharifiet al.,2009).Interac-tions between the ACC and the BLA in particular have been proposed to regulate behavior in order to allow organisms to overcome a variety of different decision costs,including delays (Floresco and Ghods-Sharifi,2007).In line with thesefindings, impairments in decision-making are also observed in humans with damage to the ACC or amygdala(Bechara et al.,1994, 1999;Manes et al.,2002;Naccache et al.,2005).Along similar lines,hippocampal damage affects decision-making.Disadvantageous choice behavior has recently been documented in patients suffering from amnesia due to hippo-campal lesions(Gupta et al.,2009),and rats with hippocampal damage show increased delay discounting(Cheung and Cardinal,2005;Mariano et al.,2009;Rawlins et al.,1985).These observations are of particular interest given that hippocampal138Neuron66,138–148,April15,2010ª2010Elsevier Inc.damage impairs the ability to imagine novel experiences (Hassa-bis et al.,2007).Based on this and a range of other studies,it has recently been proposed that hippocampus and parahippocam-pal cortex play a crucial role in the formation of vivid event repre-sentations,regardless of whether they lie in the past,present,or future (Schacter and Addis,2009).The hippocampus may thus contribute to decision-making through its role in self-projection into the future (Bar,2009;Schacter et al.,2007),allowing an organism to evaluate future payoffs through mental simulation (Johnson and Redish,2007;Johnson et al.,2007).Future thinking may thus affect intertemporal choice through hippo-campal involvement.Here we used model-based fMRI,analyses of functional coupling,and extensive behavioral procedures to investigate how episodic future thinking affects delay discounting.In Exper-iment 1,subjects performed a classical delay discounting task(Kable and Glimcher,2007;Peters and Bu¨chel,2009)that involved a series of choices between smaller immediate and larger delayed rewards,while brain activity was measured using fMRI.Critically,we introduced a novel episodic condition that involved the presentation of episodic cue words (tags )obtained during an extensive prescan interview,referring to real,subject-specific future events planned for the respective day of reward delivery.This design allowed us to assess individual discount rates separately for the two experimental conditions,allowing us to investigate neural mechanisms mediating changes in delay discounting associated with episodic thinking.In a second behavioral study,we replicated the behavioral effects of Exper-iment 1and addressed a number of alternative explanations for the observed effects of episodic tags on discount rates.RESULTSExperiment 1:Prescan InterviewOn day 1,healthy young volunteers (n =30,mean age =25,15male)completed a computer-based delay discounting proce-dure to estimate their individual discount rate (Peters and Bu ¨-chel,2009).This discount rate was used solely for the purpose of constructing subject-specific trials for the fMRI session (see Experimental Procedures ).Furthermore,participants compiled a list of events that they had planned in the next 7months (e.g.,vacations,weddings,parties,courses,and so forth)andrated them on scales from 1to 6with respect to personal rele-vance,arousal,and valence.For each participant,seven subject-specific events were selected such that the spacing between events increased with increasing delay to the episode,and that events were roughly matched based on personal rele-vance,arousal,and valence.Multiple regression analysis of these ratings across the different delays showed no linear effects (relevance:p =0.867,arousal:p =0.120,valence:p =0.977,see Figure S1available online).For each subject,a separate set of seven delays was computed that was later used as delays in the control condition.Median and range for the delays used in each condition are listed in Table S1(available online).For each event,a label was selected that would serve as a verbal tag for the fMRI session.Experiment 1:fMRI Behavioral ResultsOn day 2,volunteers performed two sessions of a delay dis-counting procedure while fMRI was measured using a 3T Siemens Scanner with a 32-channel head-coil.In each session,subjects made a total of 118choices between 20V available immediately and larger but delayed amounts.Subjects were told that one of their choices would be randomly selected and paid out following scanning,with the respective delay.Critically,in half the trials,an additional subject-specific episodic tag (see above,e.g.,‘‘vacation paris’’or ‘‘birthday john’’)was displayed based on the prescan interview (see Figure 1)indicating which event they had planned on the particular day (episodic condi-tion),whereas in the remaining trials,no episodic tag was pre-sented (control condition).Amount and waiting time were thus displayed in both conditions,but only the episodic condition involved the presentation of an additional subject-specific event tag.Importantly,nonoverlapping sets of delays were used in the two conditions.Following scanning,subjects rated for each episodic tag how often it evoked episodic associations during scanning (frequency of associations:1,never;to 6,always)and how vivid these associations were (vividness of associa-tions:1,not vivid at all;to 6,highly vivid;see Figure S1).Addition-ally,written reports were obtained (see Supplemental Informa-tion ).Multiple regression revealed no significant linear effects of delay on postscan ratings (frequency:p =0.224,vividness:p =0.770).We averaged the postscan ratings acrosseventsFigure 1.Behavioral TaskDuring fMRI,subjects made repeated choices between a fixed immediate reward of 20V and larger but delayed amounts.In the control condi-tion,amounts were paired with a waiting time only,whereas in the episodic condition,amounts were paired with a waiting time and a subject-specific verbal episodic tag indicating to the subjects which event they had planned at the respective day of reward delivery.Events were real and collected in a separate testing session prior to the day of scanning.NeuronEpisodic Modulation of Delay DiscountingNeuron 66,138–148,April 15,2010ª2010Elsevier Inc.139and the frequency/vividness dimensions,yielding an‘‘imagery score’’for each subject.Individual participants’choice data from the fMRI session were then analyzed byfitting hyperbolic discount functions to subject-specific indifference points to obtain discount rates (k-parameters),separately for the episodic and control condi-tions(see Experimental Procedures).Subjective preferences were well-characterized by hyperbolic functions(median R2 episodic condition=0.81,control condition=0.85).Discount functions of four exemplary subjects are shown in Figure2A. For both conditions,considerable variability in the discount rate was observed(median[range]of discount rates:control condition=0.014[0.003–0.19],episodic condition=0.013 [0.002–0.18]).To account for the skewed distribution of discount rates,all further analyses were conducted on the log-trans-formed k-parameters.Across subjects,log-transformed discount rates were significantly lower in the episodic condition compared with the control condition(t(29)=2.27,p=0.016),indi-cating that participants’choice behavior was less impulsive in the episodic condition.The difference in log-discount rates between conditions is henceforth referred to as the episodic tag effect.Fitting hyperbolic functions to the median indifference points across subjects also showed reduced discounting in the episodic condition(discount rate control condition=0.0099, episodic condition=0.0077).The size of the tag effect was not related to the discount rate in the control condition(p=0.56). We next hypothesized that the tag effect would be positively correlated with postscan ratings of episodic thought(imagery scores,see above).Robust regression revealed an increase in the size of the tag effect with increasing imagery scores (t=2.08,p=0.023,see Figure2B),suggesting that the effect of the tags on preferences was stronger the more vividly subjects imagined the episodes.Examples of written postscan reports are provided in the Supplemental Results for participants from the entire range of imagination ratings.We also correlated the tag effect with standard neuropsychological measures,the Sensation Seeking Scale(SSS)V(Beauducel et al.,2003;Zuck-erman,1996)and the Behavioral Inhibition Scale/Behavioral Approach Scale(BIS/BAS)(Carver and White,1994).The tag effect was positively correlated with the experience-seeking subscale of the SSS(p=0.026)and inversely correlated with the reward-responsiveness subscale of the BIS/BAS scales (p<0.005).Repeated-measures ANOVA of reaction times(RTs)as a func-tion of option value(lower,similar,or higher relative to the refer-ence option;see Experimental Procedures and Figure2C)did not show a main effect of condition(p=0.712)or a condition 3value interaction(p=0.220),but revealed a main effect of value(F(1.8,53.9)=16.740,p<0.001).Post hoc comparisons revealed faster RTs for higher-valued options relative to similarly (p=0.002)or lower valued options(p<0.001)but no difference between lower and similarly valued options(p=0.081).FMRI DataFMRI data were modeled using the general linear model(GLM) as implemented in SPM5.Subjective value of each decision option was calculated by multiplying the objective amount of each delayed reward with the discount fraction estimated behaviorally based on the choices during scanning,and included as a parametric regressor in the GLM.Note that discount rates were estimated separately for the control and episodic conditions(see above and Figure2),and we thus used condition-specific k-parameters for calculation of the subjective value regressor.Additional parametric regressors for inverse delay-to-reward and absolute reward magnitude, orthogonalized with respect to subjective value,were included in theGLM.Figure2.Behavioral Data from Experiment1Shown are experimentally derived discount func-tions from the fMRI session for four exemplaryparticipants(A),correlation with imagery scores(B),and reaction times(RTs)(C).(A)Hyperbolicfunctions werefit to the indifference points sepa-rately for the control(dashed lines)and episodic(solid lines,filled circles)conditions,and thebest-fitting k-parameters(discount rates)and R2values are shown for each subject.The log-trans-formed difference between discount rates wastaken as a measure of the effect of the episodictags on choice preferences.(B)Robust regressionrevealed an association between log-differences indiscount rates and imagery scores obtained frompostscan ratings(see text).(C)RTs were signifi-cantly modulated by option value(main effectvalue p<0.001)with faster responses in trialswith a value of the delayed reward higher thanthe20V reference amount.Note that althoughseven delays were used for each condition,somedata points are missing,e.g.,onlyfive delay indif-ference points for the episodic condition areplotted for sub20.This indicates that,for the twolongest delays,this subject never chose the de-layed reward.***p<0.005.Error bars=SEM.Neuron Episodic Modulation of Delay Discounting140Neuron66,138–148,April15,2010ª2010Elsevier Inc.Episodic Tags Activate the Future Thinking NetworkWe first analyzed differences in the condition regressors without parametric pared to those of the control condi-tion,BOLD responses to the presentation of the delayed reward in the episodic condition yielded highly significant activations (corrected for whole-brain volume)in an extensive network of brain regions previously implicated in episodic future thinking (Addis et al.,2007;Schacter et al.,2007;Szpunar et al.,2007)(see Figure 3and Table S2),including retrosplenial cortex (RSC)/PCC (peak MNI coordinates:À6,À54,14,peak z value =6.26),left lateral parietal cortex (LPC,À44,À66,32,z value =5.35),and vmPFC (À8,34,À12,z value =5.50).Distributed Neural Coding of Subjective ValueWe then replicated previous findings (Kable and Glimcher,2007;Kable and Glimcher,2010;Peters and Bu¨chel,2009)using a conjunction analysis (Nichols et al.,2005)searching for regions showing a positive correlation between the height of the BOLD response and subjective value in the control and episodic condi-tions in a parametric analysis (Figure 4A and Table S3).Note that this is a conservative analysis that requires that a given voxel exceed the statistical threshold in both contrasts separately.This analysis revealed clusters in the lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC,À36,50,À10,z value =4.50)and central OFC (À18,12,À14,z value =4.05),bilateral VS (right:10,8,0,z value =4.22;left:À10,8,À6,z value =3.51),mPFC (6,26,16,z value =3.72),and PCC (À2,À28,24,z value =4.09),representing subjective (discounted)value in both conditions.We next analyzed the neural tag effect,i.e.,regions in which the subjective value correlation was greater for the episodic condi-tion as compared with the control condition (Figure 4B and Table S4).This analysis revealed clusters in the left LPC (À66,À42,32,z value =4.96,),ACC (À2,16,36,z value =4.76),left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC,À38,36,36,z value =4.81),and right amygdala (24,2,À24,z value =3.75).Finally,we performed a triple-conjunction analysis,testing for regions that were correlated with subjective value in both conditions,but in which the value correlation increased in the episodic condition.Only left LPC showed this pattern (À66,À42,30,z value =3.55,see Figure 4C and Table S5),the same region that we previously identified as delay-specific in valuation (Petersand Bu¨chel,2009).There were no regions in which the subjective value correlation was greater in the control condition when compared with the episodic condition at p <0.001uncorrected.ACC Valuation Signals and Functional Connectivity Predict Interindividual Differences in Discount Function ShiftsWe next correlated differences in the neural tag effect with inter-individual differences in the size of the behavioral tag effect.To this end,we performed a simple regression analysis in SPM5on the single-subject contrast images of the neural tag effect (i.e.,subjective value correlation episodic >control)using the behavioral tag effect [log(k control )–log(k episodic )]as an explana-tory variable.This analysis revealed clusters in the bilateral ACC (right:18,34,18,z value =3.95,p =0.021corrected,left:À20,34,20,z value =3.52,Figure 5,see Table S6for a complete list).Coronal sections (Figure 5C)clearly show that both ACC clusters are located in gray matter of the cingulate sulcus.Because ACC-limbic interactions have previously been impli-cated in the control of choice behavior (Floresco and Ghods-Sharifi,2007;Roiser et al.,2009),we next analyzed functional coupling with the right ACC from the above regression contrast (coordinates 18,34,18,see Figure 6A)using a psychophysiolog-ical interaction analysis (PPI)(Friston et al.,1997).Note that this analysis was conducted on a separate first-level GLM in which control and episodic trials were modeled as 10s miniblocks (see Experimental Procedures for details).We first identified regions in which coupling with the ACC changed in the episodic condition compared with the control condition (see Table S7)and then performed a simple regression analysis on these coupling parameters using the behavioral tag effect as an explanatory variable.The tag effect was associated with increased coupling between ACC and hippocampus (À32,À18,À16,z value =3.18,p =0.031corrected,Figure 6B)and ACC and left amygdala (À26,À4,À26,z value =2.95,p =0.051corrected,Figure 6B,see Table S8for a complete list of activa-tions).The same regression analysis in a second PPI with the seed voxel placed in the contralateral ACC region from the same regression contrast (À20,34,22,see above)yielded qual-itatively similar,though subthreshold,results in these same structures (hippocampus:À28,À32,À6,z value =1.96,amyg-dala:À28,À6,À16,z value =1.97).Experiment 2We conducted an additional behavioral experiment to address a number of alternative explanations for the observed effects of tags on choice behavior.First,it could be argued thatepisodicFigure 3.Categorical Effect of Episodic Tags on Brain ActivityGreater activity in lateral parietal cortex (left)and posterior cingulate/retrosplenial and ventro-medial prefrontal cortex (right)was observed in the episodic condition compared with the control condition.p <0.05,FWE-corrected for whole-brain volume.NeuronEpisodic Modulation of Delay DiscountingNeuron 66,138–148,April 15,2010ª2010Elsevier Inc.141tags increase subjective certainty that a reward would be forth-coming.In Experiment 2,we therefore collected postscan ratings of reward confidence.Second,it could be argued that events,always being associated with a particular date,may have shifted temporal focus from delay-based to more date-based processing.This would represent a potential confound,because date-associated rewards are discounted less than delay-associated rewards (Read et al.,2005).We therefore now collected postscan ratings of temporal focus (date-based versus delay-based).Finally,Experiment 1left open the question of whether the tag effect depends on the temporal specificity of the episodic cues.We therefore introduced an additional exper-imental condition that involved the presentation of subject-specific temporally unspecific future event cues.These tags (henceforth referred to as unspecific tags)were obtained by asking subjects to imagine events that could realistically happen to them in the next couple of months,but that were not directly tied to a particular point in time (see Experimental Procedures ).Episodic Imagery,Not Temporal Specificity,Reward Confidence,or Temporal Focus,Predicts the Size of the Tag EffectIn total,data from 16participants (9female)are included.Anal-ysis of pretest ratings confirmed that temporally unspecific and specific tags were matched in terms of personal relevance,arousal,valence,and preexisting associations (all p >0.15).Choice preferences were again well described by hyperbolic functions (median R 2control =0.84,unspecific =0.81,specific =0.80).We replicated the parametric tag effect (i.e.,increasing effect of tags on discount rates with increasing posttest imagery scores)in this independent sample for both temporally specific (p =0.047,Figure 7A)and temporally unspecific (p =0.022,Figure 7A)tags,showing that the effect depends on future thinking,rather than being specifically tied to the temporal spec-ificity of the event cues.Following testing,subjects rated how certain they were that a particular reward would actually be forth-coming.Overall,confidence in the payment procedure washighFigure 4.Neural Representation of Subjective Value (Parametric Analysis)(A)Regions in which the correlation with subjective value (parametric analysis)was significant in both the control and the episodic conditions (conjunction analysis)included central and lateral orbitofrontal cortex (OFC),bilateral ventral striatum (VS),medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC),and posterior cingulate cortex(PCC),replicating previous studies (Kable and Glimcher,2007;Peters and Bu¨chel,2009).(B)Regions in which the subjective value correlation was greater for the episodic compared with the control condition included lateral parietal cortex (LPC),ante-rior cingulate cortex (ACC),dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC),and the right amygdala (Amy).(C)A conjunction analysis revealed that only LPC activity was positively correlated with subjective value in both conditions,but showed a greater regression slope in the episodic condition.No regions showed a better correlation with subjective value in the control condition.Error bars =SEM.All peaks are significant at p <0.001,uncorrected;(A)and (B)are thresholded at p <0.001uncorrected and (C)is thresholded at p <0.005,uncorrected for display purposes.NeuronEpisodic Modulation of Delay Discounting142Neuron 66,138–148,April 15,2010ª2010Elsevier Inc.(Figure 7B),and neither unspecific nor specific tags altered these subjective certainty estimates (one-way ANOVA:F (2,45)=0.113,p =0.894).Subjects also rated their temporal focus as either delay-based or date-based (see Experimental Procedures ),i.e.,whether they based their decisions on the delay-to-reward that was actually displayed,or whether they attempted to convert delays into the corresponding dates and then made their choices based on these dates.There was no overall significant effect of condition on temporal focus (one-way ANOVA:F (2,45)=1.485,p =0.237,Figure 7C),but a direct comparison between the control and the temporally specific condition showed a significant difference (t (15)=3.18,p =0.006).We there-fore correlated the differences in temporal focus ratings between conditions (control:unspecific and control:specific)with the respective tag effects (Figure 7D).There were no correlations (unspecific:p =0.71,specific:p =0.94),suggesting that the observed differences in discounting cannot be attributed to differences in temporal focus.High-Imagery,but Not Low-Imagery,Subjects Adjust Their Discount Function in an Episodic ContextFor a final analysis,we pooled the samples of Experiments 1and 2(n =46subjects in total),using only the temporally specific tag data from Experiment 2.We performed a median split into low-and high-imagery participants according to posttest imagery scores (low-imagery subjects:n =23[15/8Exp1/Exp2],imagery range =1.5–3.4,high-imagery subjects:n =23[15/8Exp1/Exp2],imagery range =3.5–5).The tag effect was significantly greater than 0in the high-imagery group (t (22)=2.6,p =0.0085,see Figure 7D),where subjects reduced their discount rate by onaverage 16%in the presence of episodic tags.In the low-imagery group,on the other hand,the tag effect was not different from zero (t (22)=0.573,p =0.286),yielding a significant group difference (t (44)=2.40,p =0.011).DISCUSSIONWe investigated the interactions between episodic future thought and intertemporal decision-making using behavioral testing and fMRI.Experiment 1shows that reward delay dis-counting is modulated by episodic future event cues,and the extent of this modulation is predicted by the degree of sponta-neous episodic imagery during decision-making,an effect that we replicated in Experiment 2(episodic tag effect).The neuroi-maging data (Experiment 1)highlight two mechanisms that support this effect:(1)valuation signals in the lateral ACC and (2)neural coupling between ACC and hippocampus/amygdala,both predicting the size of the tag effect.The size of the tag effect was directly related to posttest imagery scores,strongly suggesting that future thinking signifi-cantly contributed to this effect.Pooling subjects across both experiments revealed that high-imagery subjects reduced their discount rate by on average 16%in the episodic condition,whereas low-imagery subjects did not.Experiment 2addressed a number of alternative accounts for this effect.First,reward confidence was comparable for all conditions,arguing against the possibility that the tags may have somehow altered subjec-tive certainty that a reward would be forthcoming.Second,differences in temporal focus between conditions(date-basedFigure 5.Correlation between the Neural and Behavioral Tag Effect(A)Glass brain and (B and C)anatomical projection of the correlation between the neural tag effect (subjective value correlation episodic >control)and the behav-ioral tag effect (log difference between discount rates)in the bilateral ACC (p =0.021,FWE-corrected across an anatomical mask of bilateral ACC).(C)Coronal sections of the same contrast at a liberal threshold of p <0.01show that both left and right ACC clusters encompass gray matter of the cingulate gyrus.(D)Scatter-plot depicting the linear relationship between the neural and the behavioral tag effect in the right ACC.(A)and (B)are thresholded at p <0.001with 10contiguous voxels,whereas (C)is thresholded at p <0.01with 10contiguousvoxels.Figure 6.Results of the Psychophysiolog-ical Interaction Analysis(A)The seed for the psychophysiological interac-tion (PPI)analysis was placed in the right ACC (18,34,18).(B)The tag effect was associated with increased ACC-hippocampal coupling (p =0.031,corrected across bilateral hippocampus)and ACC-amyg-dala coupling (p =0.051,corrected across bilateral amygdala).Maps are thresholded at p <0.005,uncorrected for display purposes and projected onto the mean structural scan of all participants;HC,hippocampus;Amy,Amygdala;rACC,right anterior cingulate cortex.NeuronEpisodic Modulation of Delay DiscountingNeuron 66,138–148,April 15,2010ª2010Elsevier Inc.143。

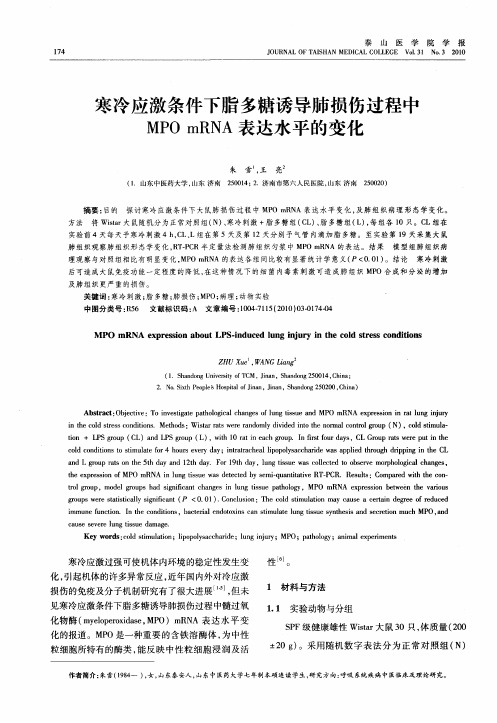

寒冷应激条件下脂多糖诱导肺损伤过程中MPO mRNA表达水平的变化

摘要 : 目的 探讨寒冷应激条件下大鼠肺损伤过 程 中 MP R A表达水平 变化, Om N 及肺 组织病理 形态学变化 。 方法 将 Wia 大鼠随机分 为正常对照组( ) 寒冷刺 激 +脂 多糖组 ( L 、 多糖 组( ) 每 组各 1 sr t N 、 C )脂 L , 0只。C L组在

c l o d t n o si lt o o r v r a ;i t ta h a i o 0y a c a i ewa p l d t r u h d p ig i h L od c n i o st t i mu ae fr4 h u se e d y n r rc e l p ls c h r sa p i h o g r p n n t e C y a l p d e i a d L go p rt n te 5 h d y a d 1 t a .F r1 t a n r u aso h t a n 2 h d y o 9 h d y,l n su a ol ce o o s re mop oo ia h n e , u g t s e w s c l td t b e v r h lgc lc a g s i e t e e p e so fMP h x rs in o O mRN i u g t s e w sd tce y s miq a t aie RT P R Re ut :C mp d w t h o — A n l n i u a ee td b e ・u n i t — C . s t v sl s o  ̄e i t ec n h t lgo p r u ,mo e o p a i i c n h n e n ln is e p t oo y MP o r d lg u s h d sg f a t c a g s i u g t u a h lg , r ni s O mRN e p e s n b t e n t e v r u A x rs i e w e h ai s o o

Inhibitory effects of microinjection

Inhibitory effects of microinjection2010-07-31Objective To examine whether microinjectlon of morphine into the rat thaiamle nucleus submedlus (Sin) could depress the bee venom (BV)-induced nociceptive behaviours. Methods In inflammatory pain model induced by BV subcutaneous injection into rat unilateral hind paw, the inhibitory effects of morphine microinjection into thalamic nucleus suhmedius (Sin) on the spontaneous nociecptlve behavior, heat hyperalgesia and tactile ailodynia, and the influence of naioxone on the morphine effects were observed in the rat. Results A single dose of morphine (5.0μg, 0. 5μL) applied into the Sm ipsilaterni to the BV injected paw significantly depressed the spontaneous paw flinching response. Morphine also significantly increased the heat paw withdrawal iateneies in the bilateral hind paw and the tactile paw withdrawal threshold in the ipsilnteral hind paw 2 hours after BV injection. All these depressive effects could be effectively antagonized by pre-treatment with the opiuld receptor antagonist naloxone (1.0μg, 0. 5μL) in the Sm 5rain prior to morphine administration. Naloxone alone injected to the Sm had no effect on the BV-induecd nociceptive behavior. Conclusion These results suggest that Sm is involved in opioid receptor-mediated antt-nociception in the rat with the BV-induced inflammatory pain. Together with results from previous studies, it is likely that this effect is produced by activation of the Sm-ventrolateral orbital cortex-periaqueductal gray pathway, leading to activation of the brainstem descending inhibitory system and depression of the nodceptive inputs at the spinal cord level.作 者:Jie Feng Ning Jia Jun-yang Wang Xin-ai Song Xiao-ying Li Jing-shi Tang ä½œè€…å •ä½ ï¼šJie Feng,Ning Jia,Xin-ai Song,Xiao-ying Li,Jing-shi Tang(Department of Physiology and Pathoph ysiology,Key Laboratory of Environment and Genes Relatedto Diseases,Ministry of Education,Medical School of Xi'an Jiaotong University,Xi'an 710061)Jun-yang Wang(Department of Immunology and Pathogenic Biology,Medical School of Xi'an Jiaotong University,Xi'an 710061,China)刊 å :西安交通大å¦å¦æŠ¥ï¼ˆè‹±æ–‡ç‰ˆï¼‰è‹±æ–‡åˆŠå :ACADEMIC JOURNAL OF XI'AN JIA OTONGUNIVERSITY(ENGLISHEDITION) å¹´ï¼Œå ·(期):2009 21(2) åˆ†ç±»å ·ï¼šQ426å…³é”®è¯ ï¼šnucl eus submedius morphine hyperaigesia ailodynia bee venom model rat。

REVIEW AND ANALYSIS OF REPORTS ON CONTROLLED CLINICAL

A CUPUNCTURE: R EVIEW AND A NALYSIS OF R EPORTS ON C ONTROLLED C LINICAL T RIALSiiAcknowledgementsAcknowledgements The World Health Organization acknowledges its indebtedness to the experts who participated in the WHO Consultation on Acupuncture held in Cervia, Italy in 1996, at which the selection criteria for the data included in this publication were set. Special thanks are due to Dr Zhu-Fan Xie, Honorary Director of the Institute of Integrated Medicines, First Hospital of Beijing Medical University, China, who drafted, revised and updated this report. Further, Dr Xie made numerous Chinese language documents available in English. We also thank Dr Hongguang Dong, Geneva University Hospital, Switzerland for providing additional information.Appreciation is extended to the Norwegian Royal Ministry of Health and Social Affairs for providing the financial support to print this review.iiiivContentsContentsAcknowledgements (iii)Contents (v)Introduction (1)Background (1)Objectives (2)Use of the publication (2)1. General considerations (3)1.1 Definition (3)1.2 Need for evaluation (3)1.3 Evaluation methodology (3)1.4 Safety (5)1.5 Availability and practicability (5)1.6 Studies on therapeutic mechanisms (6)1.7 Selection of clinical trial reports (7)2. Review of clinical trial reports (9)2.1 Pain (9)Head and face (9)Locomotor system (9)Gout (10)Biliary and renal colic (10)Traumatic or postoperative pain (11)Dentistry (11)Childbirth (11)Surgery (11)2.2 Infections (12)2.3 Neurological disorders (12)2.4 Respiratory disorders (14)2.5 Digestive disorders (14)2.6 Blood disorders (15)2.7 Urogenital disorders (15)2.8 Gynaecological and obstetric disorders (16)v2.9 Cardiovascular disorders (17)2.10 Psychiatric disorders and mental disturbances (18)2.11 Paediatric disorders (19)2.12 Disorders of the sense organs (19)2.13 Skin diseases (20)2.14 Cancers (20)2.15 Other reports (21)3. Diseases and disorders that can be treated with acupuncture (23)4. Summary table of controlled clinical trials (27)References (67)viIntroductionIntroductionBackgroundOver its 2500 years of development, a wealth of experience has accumulated inthe practice of acupuncture, attesting to the wide range of diseases andconditions that can be effectively treated with this approach. Unlike many othertraditional methods of treatment, which tend to be specific to their national orcultural context, acupuncture has been used throughout the world, particularlysince the 1970s. In recognition of the increasing worldwide interest in the subject,the World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a symposium on acupuncturein June 1979 in Beijing, China. Physicians practising acupuncture in differentcountries were invited to identify the conditions that might benefit from thistherapy. The participants drew up a list of 43 suitable diseases. However, this listof indications was not based on formal clinical trials conducted in a rigorousscientific manner, and its credibility has been questioned.The past two decades have seen extensive studies on acupuncture, and greatefforts have been made to conduct controlled clinical trials that include the use of“sham” acupuncture or “placebo” acupuncture controls. Although still limited innumber because of the difficulties of carrying out such trials, convincing reports,based on sound research methodology, have been published. In addition,experimental investigations on the mechanism of acupuncture have been carriedout. This research, while aimed chiefly at answering how acupuncture works,may also provide evidence in support of its effectiveness.In 1991, a progress report on traditional medicine and modern health care wassubmitted by the Director-General of WHO to the Forty-fourth World HealthAssembly.1The report pointed out that in countries where acupuncture formspart of the cultural heritage, its use in an integrated approach to modern andtraditional medicine presents no difficulty. However, in countries where modernWestern medicine is the foundation of health care, the ethical use of acupuncturerequires objective evidence of its efficacy under controlled clinical conditions.In 1996, a draft report on the clinical practice of acupuncture was reviewed at theWHO Consultation on Acupuncture held in Cervia, Italy. The participantsrecommended that WHO should revise the report, focusing on data fromcontrolled clinical trials. This publication is the outcome of that process.1Traditional medicine and modern health care. Progress report by the Director-General. Geneva,World Health Organization, 1991 (unpublished document A44/10).1Acupuncture: review and analysis of controlled clinical trials ObjectivesThe objective of this publication is to provide a review and analysis of controlledclinical trials of acupuncture therapy, as reported in the current literature, with aview to strengthening and promoting the appropriate use of acupuncture inhealth care systems throughout the world. Information on the therapeuticmechanisms of acupuncture has also been incorporated.Since the methodology of clinical research on acupuncture is still under debate, itis very difficult to evaluate acupuncture practice by any generally acceptedmeasure. This review is limited to controlled clinical trials that were publishedup to 1998 (and early 1999 for some journals), in the hope that the conclusionswill prove more acceptable. Such trials have only been performed for a limitednumber of diseases or disorders. This should not be taken to mean, however, thatacupuncture treatment of diseases or disorders not mentioned here is excluded. Use of the publicationThis publication is intended to facilitate research on and the evaluation andapplication of acupuncture. It is hoped that it will provide a useful resource forresearchers, health care providers, national health authorities and the generalpublic.It must be emphasized that the list of diseases, symptoms or conditions coveredhere is based on collected reports of clinical trials, using the descriptions given inthose reports. Only national health authorities can determine the diseases,symptoms and conditions for which acupuncture treatment can be recommended.The data in the reports analysed were not always clearly recorded. We havemade every effort to interpret them accurately, in some cases maintaining theoriginal wording in the text and summary table presented here. Research ontraditional medicine, including acupuncture is by no means easy. However,researchers should be encouraged to ensure the highest possible standards ofstudy design and reporting in future research in order to improve the evidencebase in this field.Dr Xiaorui ZhangActing CoordinatorTraditional Medicine (TRM)Department of Essential Drugsand Medicines Policy (EDM)World Health Organization 21. General considerations1. General considerations1.1 DefinitionAcupuncture literally means to puncture with a needle. However, the application of needles is often used in combination with moxibustion—the burning on or over the skin of selected herbs—and may also involve the application of other kinds of stimulation to certain points. In this publication the term “acupuncture” is used in its broad sense to include traditional body needling, moxibustion, electric acupuncture (electro-acupuncture), laser acupuncture (photo-acupuncture), microsystem acupuncture such as ear (auricular), face, hand and scalp acupuncture, and acupressure (the application of pressure at selected sites).1.2 Need for evaluationAcupuncture originated in China many centuries ago and soon spread to Japan, the Korean peninsula and elsewhere in Asia. Acupuncture is widely used in health care systems in the countries of this region; it is officially recognized by governments and well received by the general public.Although acupuncture was introduced to Europe as long ago as the early seventeenth century, scepticism about its effectiveness continues to exist in countries where modern Western medicine is the foundation of health care, especially in those where acupuncture has not yet been widely practised. People question whether acupuncture has a true therapeutic effect, or whether it works merely through the placebo effect, the power of suggestion, or the enthusiasm with which patients wish for a cure. There is therefore a need for scientific studies that evaluate the effectiveness of acupuncture under controlled clinical conditions.This publication reviews selected studies on controlled clinical trials. Some of these studies have provided incontrovertible scientific evidence that acupuncture is more successful than placebo treatments in certain conditions. For example, the proportion of chronic pain relieved by acupuncture is generally in the range 55–85%, which compares favourably with that of potent drugs (morphine helps in 70% of cases) and far outweighs the placebo effect (30–35%) (1–3). In addition, the mechanisms of acupuncture analgesia have been studied extensively since the late 1970s, revealing the role of neural and humoral factors.1.3 Evaluation methodologyUnlike the evaluation of a new drug, controlled clinical trials of acupuncture are extremely difficult to conduct, particularly if they have to be blind in design and the acupuncture has to be compared with a placebo. Various “sham” or “placebo” acupuncture procedures have been designed, but they are not easy to3Acupuncture: review and analysis of controlled clinical trials perform in countries such as China where acupuncture is widely used. In these countries, most patients know a great deal about acupuncture, including the special sensation that should be felt after insertion or during manipulation of the needle. Moreover, acupuncturists consider these procedures unethical because they are already convinced that acupuncture is effective. In fact, most of the placebo-controlled clinical trials have been undertaken in countries where there is scepticism about acupuncture, as well as considerable interest.A more practical way to evaluate the therapeutic effect of acupuncture is tocompare it with the effect of conventional therapy through randomized controlled trials or group studies, provided that the disease conditions before treatment are comparable across the groups, with outcome studies developed for all patients.Because of the difficulty of ruling out the placebo effect, a comparative study with no treatment as the control may not be convincing in the evaluation of acupuncture practice. Retrospective surveys, in which the effect of acupuncture therapy is compared with past treatments, may not be of significance either, particularly if they have not been well designed. Non-comparative studies are certainly of little significance, particularly when acupuncture is used for the treatment of a self-limited disease. However, if rapid improvement can be achieved in the treatment of a long-standing, chronic disease, or if there is definite improvement in a disease that is generally recognized as intractable to conventional treatment, the effect of acupuncture should be viewed in a more favourable light, even when a well-designed, controlled study has not been carried out.Another difficulty in evaluating acupuncture practice is that the therapeutic effect depends greatly on the proficiency of the acupuncturists—their ability and skill in selecting and locating the acupuncture points and in manipulating the needles. This may partly explain the disparities or inconsistencies in the results reported by different authors, even when their studies were carried out on equally sound methodological bases.Evaluating acupuncture practice and arriving at generally accepted conclusions is no easy task, therefore. While effectiveness is doubtless of the utmost importance, other factors, including safety, cost, availability and the condition of local health services must also be considered. Given the same effectiveness, these other factors may lead to different evaluations of acupuncture in different countries and areas. However, conclusions are needed that apply to worldwide use, particularly for countries and areas where proper development of acupuncture practice would bring a great deal of benefit. Evaluations should not therefore be confined to those diseases for which modern conventional treatments are inadequate or ineffective.Because of the success of surgical procedures carried out under acupuncture analgesia, the treatment of pain with acupuncture has been extensively studied.For other conditions often treated with acupuncture, there are fewer reports that have adequate methodology.41. General considerations 1.4 SafetyGenerally speaking, acupuncture treatment is safe if it is performed properly by a well-trained practitioner. Unlike many drugs, it is non-toxic, and adverse reactions are minimal. This is probably one of the chief reasons why acupuncture is so popular in the treatment of chronic pain in many countries. As mentioned previously, acupuncture is comparable with morphine preparations in its effectiveness against chronic pain, but without the adverse effects of morphine, such as dependency.Even if the effect of acupuncture therapy is less potent than that of conventional treatments, acupuncture may still be worth considering because of the toxicity or adverse effects of conventional treatments. For example, there are reports of controlled clinical trials showing that acupuncture is effective in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (4–6), although not as potent as corticosteroids. Because, unlike corticosteroids, acupuncture treatment, does not cause serious side-effects, it seems reasonable to use acupuncture for treating this condition, despite the difference in effectiveness.1.5 Availability and practicabilityThe availability and practicability of acupuncture are also important factors to consider. The advantages of acupuncture are that it is simple, convenient and has few contraindications. Although the success rate of acupuncture therapy in treating kidney stones, for example, is confirmed by comparative studies with other therapies (7), it is by no means as high as that of surgical intervention. However, acupuncture treatment of kidney stones is still worth recommending because of its simplicity, which makes it more acceptable to patients.There are also instances where acupuncture is not more practicable than conventional therapy. For example, the effectiveness of acupuncture treatment of acute bacillary dysentery has been shown to be comparable with that of furazolidone (8–10), but this is of rather academic significance because oral administration of furazolidone or other antidysenteric drugs is more convenient. The conditions of the health service in a given country or area should also be considered in evaluating acupuncture practice. In developing countries, where medical personnel and medicines are still lacking, the need for acupuncture may be considerable and urgent; proper use of this simple and economic therapy could benefit a large number of patients. On the other hand, in developed countries, where the health system is well established, with sophisticated technology, adequate personnel and a well-equipped infrastructure, acupuncture might be considered to be of great value in only a limited number of conditions. It could still serve as a valuable alternative treatment for many diseases or conditions for which modern conventional treatments are unsuccessful. It is also valuable in situations where the patient is frightened of the potential risks or adverse effects of modern conventional treatments. In fact, in some developed countries, the diseases for which patients seek help from acupuncturists tend to be beyond the scope of orthodox medicine.Acupuncture: review and analysis of controlled clinical trials 1.6 Studies on therapeutic mechanismsClinical evaluations indicate whether the therapy works; research on the mechanisms involved indicates how it works and can also provide important information on efficacy. Knowing that acupuncture is effective and why makes the practitioner confident in its use, and also allows the technique to be used in a more appropriate way.The clinical evaluation may precede studies on the mechanisms, or vice versa. For acupuncture, in most instances the clinical effect has been tested first. Use of the technique may then be further expanded on the basis of the results of research on the mechanisms. For example, experimental studies of the effect of acupuncture on white blood cells led to a successful trial of the treatment of leukopenia caused by chemotherapy.To date, modern scientific research studies have revealed the following actions of acupuncture:• inducing analgesia• protecting the body against infections• regulating various physiological functions.In reality, the first two actions can also be attributed to the regulation of physiological functions. The therapeutic effects of acupuncture are thus brought about through its regulatory actions on various systems, so that it can be regarded as a nonspecific therapy with a broad spectrum of indications, particularly helpful in functional disorders. Although it is often used as a symptomatic treatment (for pain, for instance), in many cases it actually acts on one of the pathogenic links of a disease.Although different acupuncture points and manipulations may have an effect through different actions, the most important factor that influences the direction of action is the condition of the patient. Numerous examples reveal that the regulatory action of acupuncture is bi-directional. Acupuncture lowers the blood pressure in patients with hypertension and elevates it in patients with hypotension; increases gastric secretion in patients with hypoacidity, and decreases it in patients with hyperacidity; and normalizes intestinal motility under X-ray observation in patients with either spastic colitis or intestinal hypotonia (11). Therefore, acupuncture itself seldom makes the condition worse. In most instances, the main danger of its inappropriate application is neglecting the proper conventional treatment.Since its therapeutic actions are achieved by mobilization of the organism’s own potential, acupuncture does not produce adverse effects, as do many drug therapies. For example, when release of hydrocortisone plays an important role in the production of a therapeutic effect, the doses of this substance released by acupuncture are small and finely regulated, thereby avoiding the side-effects of hydrocortisone chemotherapy (12). On the other hand—and for the same reason—acupuncture has limitations. Even under conditions where acupuncture is indicated, it may not work if the mobilization of the individual’s potential is not adequate for recovery.1. General considerations 1.7 Selection of clinical trial reportsIn recent decades, numerous clinical trials have been reported; however, only formally published articles that meet one of the following criteria are included in this review:• randomized controlled trials (mostly with sham acupuncture or conventional therapy as control) with an adequate number of patients observed;• nonrandomized controlled clinical trials (mostly group comparisons) with an adequate number of patients observed and comparable conditions in the various groups prior to treatment.In many published placebo-controlled trials, sham acupuncture was carried out by needling at incorrect, theoretically irrelevant sites. Such a control really only offers information about the most effective sites of needling, not about the specific effects of acupuncture (13). Positive results from such trials, which revealed that genuine acupuncture is superior to sham acupuncture with statistical significance, provide evidence showing the effectiveness of acupuncture treatment. On the other hand, negative results from such trials, in which both the genuine and sham acupuncture showed considerable therapeutic effects with no significant difference between them, can hardly be taken as evidence negating the effectiveness of acupuncture. In the latter case, especially in treatment of pain, most authors could only draw the conclusion that additional control studies were needed. Therefore, these reports are generally not included in this review.The reports are first reviewed by groups of conditions for which acupuncture therapy is given (section 2). The clinical conditions covered have then been classified into four categories (section 3):1. Diseases, symptoms or conditions for which acupuncture has beenproved—through controlled trials—to be an effective treatment.2. Diseases, symptoms or conditions for which the therapeutic effect ofacupuncture has been shown, but for which further proof is needed.3. Diseases, symptoms or conditions for which there are only individualcontrolled trials reporting some therapeutic effects, but for which acupuncture is worth trying because treatment by conventional and othertherapies is difficult.4. Diseases, symptoms or conditions in which acupuncture may be triedprovided the practitioner has special modern medical knowledge andadequate monitoring equipment.Section 4 provides a tabulated summary of the controlled clinical trials reviewed, giving information on the number of subjects, the study design, the type of acupuncture applied, the controls used and the results obtained.Acupuncture: review and analysis of controlled clinical trials2. Review of clinical trial reports2. Review of clinical trial reports 2.1 PainThe effectiveness of acupuncture analgesia has already been established in controlled clinical studies. As mentioned previously, acupuncture analgesia works better than a placebo for most kinds of pain, and its effective rate in the treatment of chronic pain is comparable with that of morphine. In addition, numerous laboratory studies have provided further evidence of the efficacy of acupuncture’s analgesic action as well as an explanation of the mechanism involved. In fact, the excellent analgesic effects of acupuncture have stimulated research on pain.Because of the side-effects of long-term drug therapy for pain and the risks of dependence, acupuncture analgesia can be regarded as the method of choice for treating many chronically painful conditions.The analgesic effect of acupuncture has also been reported for the relief of eye pain due to subconjunctival injection (14), local pain after extubation in children (15),and pain in thromboangiitis obliterans (16).2.1.1 Head and faceThe use of acupuncture for treating chronic pain of the head and face has been studied extensively. For tension headache, migraine and other kinds of headache due to a variety of causes, acupuncture has performed favourably in trials comparing it with standard therapy, sham acupuncture, or mock transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) (17–27). The results suggest that acupuncture could play a significant role in treating such conditions.Chronic facial pain, including craniomandibular disorders of muscular origin, also responds well to acupuncture treatments (28–31). The effect of acupuncture is comparable with that of stomatognathic treatments for temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction. Acupuncture may be useful as complementary therapy for this condition, as the two treatments probably have a different basis of action (2, 32).2.1.2 Locomotor systemChronically painful conditions of the locomotor system accompanied by restricted movements of the joints are often treated with acupuncture if surgical intervention is not necessary. Acupuncture not only alleviates pain, it also reduces muscle spasm, thereby increasing mobility. Joint damage often results from muscle malfunction, and many patients complain of arthralgia before anyAcupuncture: review and analysis of controlled clinical trials changes are demonstrable by X-ray. In these cases, acupuncture may bring about a permanent cure. Controlled studies on common diseases and conditions in this category have been reported by different authors, with favourable results for acupuncture treatments compared with standard therapy, delayed-treatment controls, control needling, mock TENS, or other sham acupuncture techniques. The conditions concerned include cervical spondylitis or neck pain due to other causes (33–37), periarthritis of the shoulder (38, 39) fibromyalgia (40), fasciitis (41), epicondylitis (tennis elbow) (42–44), low back pain (45–49), sciatica (50–53), osteoarthritis with knee pain (54–56), and radicular and pseudoradicular pain syndromes (57). In some reports, comparison was made between standard care and acupuncture as an adjunct to standard care. The conclusion from one such randomized controlled trial was that acupuncture is an effective and judicious adjunct to conventional care for patients with osteoarthritis of the knee (58). Rheumatoid arthritis is a systemic disease with extra-articular manifestations in most patients. In this disease, dysfunction of the immune system plays a major role, which explains the extra-articular and articular features. Acupuncture is beneficial in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (4–6). While acupuncture may not improve the damage that has been done to the joints, successful pain relief has been verified in the majority of controlled studies (58). The action of acupuncture on inflammation and the dysfunctional immune system is also beneficial (5, 59).2.1.3 GoutIn a randomized controlled trial, blood-pricking acupuncture was compared with conventional medication (allopurinol). The acupuncture group showed greater improvement than the allopurinol group. In addition, a similar reduction of uric acid levels in the blood and urine of both groups was noted (60). Plum-blossom needling (acupuncture using plum-blossom needles), together with cupping (the application to the skin of cups which are then depressurized), has been recommended for treating gouty arthritis (61).2.1.4 Biliary and renal colicAcupuncture is suitable for treating acute pain, provided the relief of pain will not mask the correct diagnosis, for which other treatments may be needed. Biliary and renal colic are two conditions for which acupuncture can be used not only as an analgesic but also as an antispasmodic. In controlled studies on biliary colic (62–64) and renal colic (7, 65, 66), acupuncture appears to have advantages over conventional drug treatments (such as intramuscular injection of atropine, pethidine, anisodamine (a Chinese medicine structurally related to atropine, isolated from Anisodus tanguticus), bucinnazine (also known as bucinperazine) or a metamizole–camylofin combination). It provides a better analgesic effect in a shorter time, without side-effects. In addition, acupuncture is effective for relieving abdominal colic, whether it occurs in acute gastroenteritis or is due to gastrointestinal spasm (67).2. Review of clinical trial reports2.1.5 Traumatic or postoperative painFor traumas such as sprains, acupuncture is not only useful for relieving pain without the risk of drug dependence, but may also hasten recovery by improving local circulation (68–70). Acupuncture analgesia to relieve postoperative pain is well recognized and has been confirmed in controlled studies (71–76). The first successful operation under acupuncture analgesia was a tonsillectomy. This was, in fact, inspired by the success of acupuncture in relieving post-tonsillectomy pain. Post-tonsillectomy acupuncture was re-evaluated in a controlled study in 1990, which not only showed prompt alleviation of throat pain, but also reduction in salivation and promotion of healing in the operative wound (76). 2.1.6 DentistryAcupuncture has been widely used in dentistry. There are reports of randomized controlled trials on the analgesic effect of acupuncture for postoperative pain from various dental procedures, including tooth extraction (77–78), pulp devitalization (79), and acute apical periodontitis (80). According to a systematic review of papers on the use of acupuncture in dentistry published between 1966 and 1996, 11 out of 15 randomized controlled studies with blind controls, appropriate statistics and sufficient follow-up showed standard acupuncture to be more effective than a placebo or sham acupuncture. It was therefore concluded that acupuncture should be considered a reasonable alternative or supplement to current dental practice as an analgesic (81). Its use in the treatment of temporomandibular dysfunction was also supported in these studies.2.1.7 ChildbirthIn childbirth, acupuncture analgesia is useful for relieving labour pain and can significantly reduce the duration of labour (82).In the case of weakened uterine contractions, acupuncture increases the activity of the uterus. Episiotomy and subsequent suturing of the perineum can also be carried out with acupuncture analgesia. In addition, the avoidance of narcotics is advantageous for newborn infants.2.1.8 SurgeryAcupuncture analgesia has the following advantages in surgical operations. It is a very safe procedure compared with drug anaesthesia; no death has ever been reported from acupuncture analgesia. There is no adverse effect on physiological functions, whereas general anaesthesia often interferes with respiration and blood pressure, for example. There are fewer of the postoperative complications that sometimes occur after general anaesthesia, such as nausea, urinary retention, constipation, and respiratory infections. The patient remains conscious and able to talk with the medical team during the operation so that injury of the facial and recurrent laryngeal nerve can be avoided. However, remaining conscious may be a disadvantage if the patient cannot tolerate the emotional stress of the procedure.。