克鲁格曼国贸理论第十版课后习题集答案解析CH04

克鲁格曼 国际经济学第10版 英文答案 国际贸易部分krugman_intlecon10_im_06_GE

Chapter 6The Standard Trade Model⏹Chapter OrganizationA Standard Model of a Trading EconomyProduction Possibilities and Relative SupplyRelative Prices and DemandThe Welfare Effect of Changes in the Terms of TradeDetermining Relative PricesEconomic Growth: A Shift of the RS CurveGrowth and the Production Possibility FrontierWorld Relative Supply and the Terms of TradeInternational Effects of GrowthCase Study: Has the Growth of Newly Industrializing Countries Hurt Advanced Nations?Tariffs and Export Subsidies: Simultaneous Shifts in RS and RDRelative Demand and Supply Effects of a TariffEffects of an Export SubsidyImplications of Terms of Trade Effects: Who Gains and Who Loses?International Borrowing and LendingIntertemporal Production Possibilities and TradeThe Real Interest RateIntertemporal Comparative AdvantageSummaryAPPENDIX TO CHAPTER 6: More on Intertemporal Trade⏹Chapter OverviewPrevious chapters have highlighted specific sources of comparative advantage that give rise to international trade. This chapter presents a general model that admits previous models as special cases. This “standard trade model” is the workhorse of international trade theory and can be used to address a wide range of issues. Some of these issues, such as the welfare and distributional effects of economic growth, transfers between nations, and tariffs and subsidies on traded goods, are considered in this chapter.© 2015 Pearson Education LimitedThe standard trade model is based upon four relationships. First, an economy will produce at the point where the production possibilities curve is tangent to the relative price line (called the isovalue line). Second, indifference curves describe the tastes of an economy, and the consumption point for that economy is found at the tangency of the budget line and the highest indifference curve. These two relationships yield the familiar general equilibrium trade diagram for a small economy (one that takes as given the terms of trade), where the consumption point and production point are the tangencies of the isovalue line with the highest indifference curve and the production possibilities frontier, respectively.You may want to work with this standard diagram to demonstrate a number of basic points. First, an autarkic economy must produce what it consumes, which determines the equilibrium price ratio; and second, opening an economy to trade shifts the price ratio line and unambiguously increases welfare. Third, an improvement in the terms of trade (ratio of export prices to import prices) increases welfare in the economy. Fourth, it is straightforward to move from a small country analysis to a two-country analysis by introducing a structure of world relative demand and supply curves, which determine relative prices.These relationships can be used in conjunction with the Rybczynski and the Stolper-Samuelson theorems from the previous chapter to address a range of issues. For example, you can consider whether the dramatic economic growth of China has helped or hurt the United States as a whole and also identify the classes of individuals within the United States who have been hurt by China’s particular growth biases. In teaching these points, it might be interesting and useful to relate them to current events. For example, you can lead a class discussion on the implications for the United States of the provision of forms of technical and economic assistance to the emerging economies around the world or the ways in which a world recession can lead to a fall in demand for U.S. exports.The example provided in the text considers the popular arguments in the media that growth in China hurts the United States. The analysis presented in this chapter demonstrates that the bias of growth is important in determining welfare effects rather than the country in which growth occurs. The existence of biased growth and the possibility of immiserizing growth are discussed. The Relative Supply (RS) and Relative Demand (RD) curves illustrate the effect of biased growth on the terms of trade. The new termsof trade line can be used with the general equilibrium analysis to find the welfare effects of growth. A general principle that emerges is that a country that experiences export-biased growth will have a deterioration in its terms of trade, while a country that experiences import-biased growth has an improvement in its terms of trade. A case study argues that this is really an empirical question, and the evidence suggests that the rapid growth of countries like China has not led to a significant deterioration of the U.S. terms of trade nor has it drastically improved China’s terms of trade.The second area to which the standard trade model is applied is the effects of tariffs and export subsidies on welfare and terms of trade. The analysis proceeds by recognizing that tariffs or subsidies shift both the relative supply and relative demand curves. A tariff on imports improves the terms of trade, expressed in external prices, while a subsidy on exports worsens terms of trade. The size of the effect depends upon the size of the country in the world. Tariffs and subsidies also impose distortionary costs upon the economy. Thus, if a country is large enough, there may be an optimum, nonzero tariff. Export subsidies, however, only impose costs upon an economy. Internationally, tariffs aid import-competing sectors and hurt export sectors, while subsidies have the opposite effect.The chapter then closes with a discussion of international borrowing and lending. The standard trade model is adapted to trade in consumption across time. The relative price of future consumption is defined as 1/(1 r), where r is the real interest rate. Countries with relatively high real interest rates (newly industrializing countries with high investment returns for example) will be biased toward future consumption and will effectively “export” future consumption by borrowing from established developed countries with relatively lower real interest rates.Chapter 6 The Standard Trade Model 29Answers to Textbook Problems1.If the relative price of palm oil increases in relation to the price of lubricants, this would increase theproduction of palm oil, because Indonesia exports palm oil. Similarly, an increase in relative price of lubricants leads to a shift along the indifference curve, towards lubricants and away from palm oil for Indonesia. This is because Palm oil is relatively expensive, hence reducing palm oil consumption in Indonesia.Expensive palm oil increases the relative income of Indonesia. The income effect would induce more for the consumption of palm oil whereas the substitution effect acts to make the economy consume less of palm oil and more of lubricants. However, if the income effect outweighs the substitution effect, then the consumption of palm oil would increase in Indonesia.2.In panel a, the re duction of Norway’s production possibilities away from fish cause the production of fish relative to automobiles to fall. Thus, despite the higher relative price of fish exports, Norway moves down to a lower indifference curve representing a drop in welfare.In panel b, the increase in the relative price of fish shifts causes Norway’s relative production of fish to rise (despite the reduction in fish productivity). Thus, the increase in the relative price of fish exports allows Norway to move to a higher indifference curve and higher welfare.3. The terms of trade of the home country would worsen. This is because a strong biased productiontowards cloth would increase the home country’s supply of cloth and shifts the supply curve to the right. At the same time, the production of wheat would decline relative to the production of cloth. An increased supply of cloth would reduce the price at the domestic and at the international market. The reduction in international price of cloth would worsen the terms of trade of the home country as the home country exports. On the other hand, if the home country’s production grows in favor of wheat, the terms of trade would improve in favor of the home country. This is because wheat is imported by the home country.© 2015 Pearson Education Limited。

完整版克鲁格曼国际经济学第十版重点笔记

《国际经济学》(第10版)保罗·R·克鲁格曼重点笔记第三章劳动生产率与比较优势:李嘉图模型1.机会成本:利用一定资源或时间生产一种商品时,而失去的利用这些资源生产其他最佳替代品的机会。

2.比较优势:如果一个国家在本国生产一种产品的机会成本(用其他产品来衡量)低于在其他国家生产该种产品的机会成本,则这个国家在生产该种产品上就具有比较优势。

比较优势和国际贸易的基本原理:如果每个国家都出口本国具有比较优势的商品,则两国之间的贸易能使两国都受益。

英国经济学家大卫·李嘉图提出的国际贸易模型。

他指出,国际劳动生产率的不同是国际贸易的唯一决定因素。

该理论被称为李嘉图模型。

3.单一要素经济单位产品劳动投入(a):生产率的倒数,用来表示劳动生产率。

L生产可能性边界(PPF):一个国家的资源是有限的,它所能生产的产品也是有限的,因此就存在着产品替代的问题:多生产一种产品就意味着要牺牲另一种产品的产量。

一个经济体的生产可能性边界(PPF)显示了其固定数量资源所能生产的商品的最大数量。

本国资源对产出的限制:aQ + aQ ≤ L WLWLCC(斜率的绝对值等于横轴商品的机会成本)奶酪的机会成本k= - a /a = (a – /a )Q ,Q = L/a LWCLCLWLCWLW相对价格与供给而劳奶酪和葡萄酒的供给是由劳动力的流向决定的,简化模型中,劳动是唯一的生产要素,等工资率单一要素模型中不存在利润,奶酪部门每小时的动力总会流向工资比较高的部门。

/a。

,葡萄酒部门每小时的工资率等于小时内创造的价值P/aP于一个工人在1LWWCLC < /P时,奶酪部门的工资率就比较高,该国会专业化生产奶酪;当 > a/aP当P /P WLC CLWWC/a = aP /P/aa时,葡萄酒部门的工资率就比较高,该国会专业化生产葡萄酒;当LWCLC LC WLW时,该国会生产奶酪和葡萄酒两种产品。

最新克鲁格曼国经第十版课后习题03-04

解答 2

世界相对供给和相对需求

苹果的相对价格, Pa/Pb

a*La/a*Lb =5

RS

aLa/aLb =3/2

(1/2,,2) RD

Q 400 苹果的相对产量, Qa + Q*a

800

Qb + Q*b

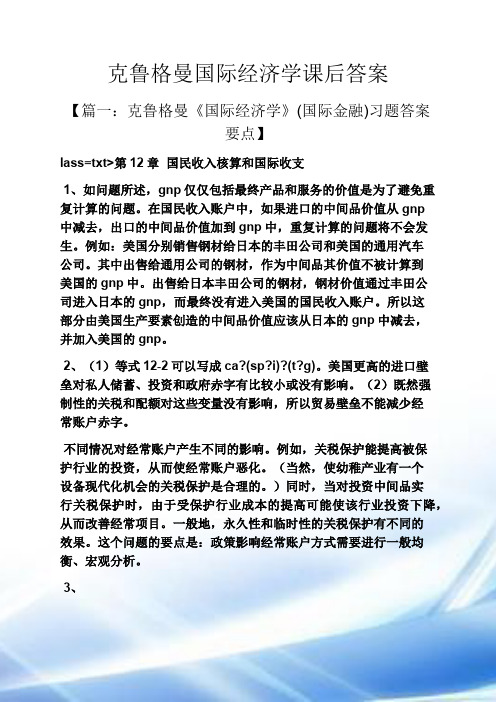

• 横轴:苹果数量/香蕉数量,即Qaw/Qbw; 纵轴:苹果的相对价格,即Pa/Pb

• 供给曲线:起点从纵轴3/2处水平向右到横轴 400/800(该点为本国专业化生产苹果,外 国专业化生产香蕉的相对产量,即本国在苹 果价格为3/2下苹果的最大生产量),然后垂 直向上到纵轴为5处水平一直向右

(1/2,,2)

(2/3,3/2) RD

Q 400

Q' 800

800

800 苹果的相对产量, Qa w

Qbw

• 本国工人数量2400时,供给曲线起点从纵轴 3/2处水平向右到横轴800/800(该点为本国 专业化生产苹果,外国专业化生产香蕉的相 对产量,即本国在苹果价格为3/2下苹果的最 大生产量),然后垂直向上到纵轴为5处水平 一直向右,需求曲线与供给曲线交点为: (2/3,3/2),苹果的世界均衡相对价格 Paw/Pbw=3/2

2.假定世界相对需求的表示为:对苹果的需求/对香蕉的需求=香蕉价格/苹果价格 ① 画出世界的相对供给曲线和相对需求曲线。 ② 苹果的世界均衡相对价格是多少? ③ 描述本题的贸易模式。 ④ 说明本国和外国都可以从贸易中获利。

3. 假设本国有2400名工人,画出世界相对供给曲线,并确定均衡的相对价格。 如果本国2400名工人的生产效率只有前述习题中假设的一半,情况如何? 比较 不同情况下的贸易所得

• 此时本国既生产苹果又生产香蕉,外国专业 化生产香蕉

克鲁格曼国际经济学课后答案

克鲁格曼国际经济学课后答案【篇一:克鲁格曼《国际经济学》(国际金融)习题答案要点】lass=txt>第12章国民收入核算和国际收支1、如问题所述,gnp仅仅包括最终产品和服务的价值是为了避免重复计算的问题。

在国民收入账户中,如果进口的中间品价值从gnp中减去,出口的中间品价值加到gnp中,重复计算的问题将不会发生。

例如:美国分别销售钢材给日本的丰田公司和美国的通用汽车公司。

其中出售给通用公司的钢材,作为中间品其价值不被计算到美国的gnp中。

出售给日本丰田公司的钢材,钢材价值通过丰田公司进入日本的gnp,而最终没有进入美国的国民收入账户。

所以这部分由美国生产要素创造的中间品价值应该从日本的gnp中减去,并加入美国的gnp。

2、(1)等式12-2可以写成ca?(sp?i)?(t?g)。

美国更高的进口壁垒对私人储蓄、投资和政府赤字有比较小或没有影响。

(2)既然强制性的关税和配额对这些变量没有影响,所以贸易壁垒不能减少经常账户赤字。

不同情况对经常账户产生不同的影响。

例如,关税保护能提高被保护行业的投资,从而使经常账户恶化。

(当然,使幼稚产业有一个设备现代化机会的关税保护是合理的。

)同时,当对投资中间品实行关税保护时,由于受保护行业成本的提高可能使该行业投资下降,从而改善经常项目。

一般地,永久性和临时性的关税保护有不同的效果。

这个问题的要点是:政策影响经常账户方式需要进行一般均衡、宏观分析。

3、(1)、购买德国股票反映在美国金融项目的借方。

相应地,当美国人通过他的瑞士银行账户用支票支付时,因为他对瑞士请求权减少,故记入美国金融项目的贷方。

这是美国用一个外国资产交易另外一种外国资产的案例。

(2)、同样,购买德国股票反映在美国金融项目的借方。

当德国销售商将美国支票存入德国银行并且银行将这笔资金贷给德国进口商(此时,记入美国经常项目的贷方)或贷给个人或公司购买美国资产(此时,记入美国金融项目的贷方)。

最后,银行采取的各项行为将导致记入美国国际收支表的贷方。

克鲁格曼 国际经济学第10版 英文答案 国际贸易部分krugman_intlecon10_im_12_GE

Chapter 12Controversies in Trade Policy⏹Chapter OrganizationSophisticated Arguments for Activist Trade PolicyTechnology and ExternalitiesImperfect Competition and Strategic Trade PolicyBox: A Warning from Intel’s FounderCase Study: When the Chips Were UpGlobalization and Low-Wage LaborThe Anti-Globalization MovementTrade and Wages RevisitedLabor Standards and Trade NegotiationsEnvironmental and Cultural IssuesThe WTO and National IndependenceCase Study: A Tragedy in BangladeshGlobalization and the EnvironmentGlobalization, Growth, and PollutionThe Problem of “Pollution Havens”The Carbon Tariff DisputeSummary⏹Chapter OverviewAlthough the text has shown why, in general, free trade is a good policy, this chapter considers two controversies in trade policy that challenge free trade. The first regards strategic trade policy. Proponents of activist government trade intervention argue that certain industries are desirable and may be underfunded by markets or dominated by imperfect competition and warrant some government intervention. The second controversy regards the recent debate over the effects of globalization on workers, the environment, and sovereignty. While the anti-globalization arguments often lack sound structure, their visceral nature demonstrates that the spread of trade is extremely troubling to some groups.As seen in the previous chapters, activist trade policy may be justified if there are market failures. One important type of market failure involves externalities present in high-technology industries due to their knowledge creation. Existence of externalities associated with research and development and high technology make the private return to investing in these activities less than their social return. This means© 2015 Pearson Education, Inc.64 Krugman/Obstfeld/Melitz •International Economics: Theory & Policy, Tenth Editionthat the private sector will tend to invest less in high-technology sectors than is socially optimal. Although there may be some case for intervention, the difficulties in targeting the correct industry and understanding the quantitative size of the externality make effective intervention complicated. To address this market failure of insufficient knowledge creation, the first best policy may be to directly support research and development in all industries. Still, although it is a judgment call, the technology spillover case for industrial policy probably has better footing in solid economics than any other argument.Another set of market failures arises when imperfect competition exists. Strategic trade policy by a government can work to deter investment and production by foreign firms and raise the profits of domestic firms.An example is provided in the text that illustrates the case where the increase in profits following the imposition of a subsidy can actually exceed the cost of a subsidy to an imperfectly competitive industryif domestic firms can capture profits from foreign firms. Although this is a valid theoretical argument for strategic policy, it is nonetheless open to criticism in choosing the industries that should be subsidized and the levels of subsidies to these industries. These criticisms are associated with the practical aspects of insufficient information and the threat of foreign retaliation. The case study on the attempts to promote the semiconductor chips industry shows that neither excess returns nor knowledge spillovers necessarily materialize even in industries that seem perfect for activist trade policy.The next section of the chapter examines the anti-globalization movement. In particular, it examines the concerns over low wages in poor countries. Standard analysis suggests that trade should help poor countries and, in particular, help the abundant factor (labor) in those countries. Protests in Seattle, which shut down WTO negotiations, and subsequent demonstrations at other meetings showed, though, that protestors either did not understand or did not agree with this analysis.The concern over low wages in poor countries is a revision of arguments in Chapter 2. Analysis in the current chapter shows again that trade should help the purchasing power of all workers and that if anyone is hurt, it is the workers in labor-scarce countries. The low wages in export sectors of poor countriesare higher than they would be without the export-oriented manufacturing, and although the situation of these workers may be more visible than before, that does not make it worse. Practically, the policy issue is whether or not labor standards should be part of trade pacts. Although such standards may act in ways similar to a domestic minimum wage, developing countries fear that such standards would be used as a protectionist tool. A case study on the 2013 collapse of a garment factory in Bangladesh highlights this tension. The Bangladeshi garment industry would not be globally competitive if it had to raise labor standards to rich country standards. Bangladeshi garment workers, though very poorly paid by rich country standards, earn more than workers in non-export sectors. A potential solution would be for consumers in rich countries to pay more for goods certified to have been produced under improved labor standards, thereby giving producers in poor countries both the means and the incentive to improve labor standards,Anti-globalization protestors were by no means united in their cause. There were also strong concerns that export manufacturing in developing countries was bad for the environment. Again, the issue is whether these concerns should be addressed by tying environmental standards into trade negotiations, and the open question is whether this can be done without destroying the export industries in developing countries. Globalization raises questions of cultural independence and national sovereignty. Specifically, many countries are disturbed by the WTO’s ability to overturn laws that do not seem to be trade restrictions but which nonetheless have trade impacts. This point highlights the difficulty of advancing trade liberalization when the clear impediments to trade—tariffs or quotas—have been removed, yet national policies regarding industry promotion or labor and environmental standards still need to be reformed.© 2015 Pearson Education LimitedThe final section of the chapter examines the link between trade and the environment. In general, production and consumption can cause environmental damage. Yet, as a country’s GDP per capita grows, the environmental damage done first grows and then eventually declines as the country gets rich enough to begin to protect the environment. As trade has lifted incomes of some countries, it may have been bad for the environment—but largely by making poor countries richer, an otherwise good thing. In theory, there could be a concern about “pollution havens,” that is countries with low environmental standards that attract “dirty” industries. There is relatively little evidence of this ph enomenon thus far. Furthermore, the pollution in these locations tends to be localized and is therefore better left to national rather than international policy. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the cap and trade system for greenhouse gases (an example of transboundary pollution) currently being debated in the U.S. Congress. Part of this policy aimed at reducing carbon emissions is an imposition of a “carbon tariff” on imports from countries that do not have their own carbon taxes. Proponents argue that such tariffs are necessary to prevent production from shifting to pollution havens and to reduce the overall level of carbon emissions, while opponents argue that these tariffs are simply more protectionism masquerading as environmental regulation.Answers to Textbook Problems1. The main disadvantage is that strategic trade policy can lead to both “rent-seeking” and beggar-thy-neighbor policies, which can increase one country’s welfare at the other country’s expense. Such policies can lead to a trade war in which every country is worse off, even though one country could become better off in the absence of retaliation. This is the danger in enacting strategic trade policy: It often provokes retaliation, which, in the long run, can make everyone worse off. Furthermore, it can be difficult to identify both which industries to subsidize and how much to subsidize them. Failure to correctly identify these factors can lead to a net loss from a subsidy.2. Globalization has many pros and cons, well-illustrated in famous controversies—like the onestimulated by Joseph Stiglitz’s book, Globalization and Its Discontents. Initiatives like the Doha Development Agenda try to address some of them and find solutions acceptable to every country. 3. The results of basic research may be appropriated by a wider range of firms and industries thanthe results of research applied to specific industrial applications. The benefits to the United States of Japanese basic research would exceed the benefits from Japanese research targeted to specific problems in Japanese industries. A specific application may benefit just one firm in Japan, perhaps simply subsidizing an activity that the market is capable of funding. General research will provide benefits that spill across borders to many firms and may be countering a market failure, externalities present in the advancement of general knowledge.4. The reason why strategic trade policies attract retaliation from other countries is because they presentthe same problems that are faced when considering the use of a tariff to improve the terms of trade.Strategic policies are, in essence, a type of beggar-thy-neighbor policies that increase one country’s welfare at other countries’ expense. A good example is represented by export quot as on scarcemineral ores—like the one adopted by China for Rare Earth Elements (REE) exports since 2006—that have already provoked filing a complaint to the WTO by the US, the EU, and Japan.。

克鲁格曼-国际经济学第十版 课件C04

•© Pearson Education Limited 2015. All rights reserved.

•1-4

The Specific Factors Model (cont.)

•1-2

Introduction

• If trade is so good for the economy, why is there such opposition?

• Two main reasons why international trade has strong effects on the distribution of income within a country:

•© Pearson Education Limited 2015. All rights reserved.

•1-15

Production Possibilities (cont.)

• Opportunity cost of producing one more yard of cloth is MPLF/MPLC pounds of food.

– Land and capital are both specific factors used only in the production of one good.

•© Pearson Education Limited 2015. All rights reserved.

•1-5

The Specific Factors Model (cont.)

•1-7

克鲁格曼国际经济学课后答案

克鲁格曼国际经济学课后答案【篇一:克鲁格曼《国际经济学》(国际金融)习题答案要点】lass=txt>第12章国民收入核算与国际收支1、如问题所述,gnp仅仅包括最终产品和服务的价值是为了避免重复计算的问题。

在国民收入账户中,如果进口的中间品价值从gnp中减去,出口的中间品价值加到gnp中,重复计算的问题将不会发生。

例如:美国分别销售钢材给日本的丰田公司和美国的通用汽车公司。

其中出售给通用公司的钢材,作为中间品其价值不被计算到美国的gnp中。

出售给日本丰田公司的钢材,钢材价值通过丰田公司进入日本的gnp,而最终没有进入美国的国民收入账户。

所以这部分由美国生产要素创造的中间品价值应该从日本的gnp中减去,并加入美国的gnp。

2、(1)等式12-2可以写成ca?(sp?i)?(t?g)。

美国更高的进口壁垒对私人储蓄、投资和政府赤字有比较小或没有影响。

(2)既然强制性的关税和配额对这些变量没有影响,所以贸易壁垒不能减少经常账户赤字。

不同情况对经常账户产生不同的影响。

例如,关税保护能提高被保护行业的投资,从而使经常账户恶化。

(当然,使幼稚产业有一个设备现代化机会的关税保护是合理的。

)同时,当对投资中间品实行关税保护时,由于受保护行业成本的提高可能使该行业投资下降,从而改善经常项目。

一般地,永久性和临时性的关税保护有不同的效果。

这个问题的要点是:政策影响经常账户方式需要进行一般均衡、宏观分析。

3、(1)、购买德国股票反映在美国金融项目的借方。

相应地,当美国人通过他的瑞士银行账户用支票支付时,因为他对瑞士请求权减少,故记入美国金融项目的贷方。

这是美国用一个外国资产交易另外一种外国资产的案例。

(2)、同样,购买德国股票反映在美国金融项目的借方。

当德国销售商将美国支票存入德国银行并且银行将这笔资金贷给德国进口商(此时,记入美国经常项目的贷方)或贷给个人或公司购买美国资产(此时,记入美国金融项目的贷方)。

最后,银行采取的各项行为将导致记入美国国际收支表的贷方。

克鲁格曼国贸理论第十版课后习题集答案解析CH04

Chapter 4Specific Factors and Income Distribution⏹Chapter OrganizationThe Specific Factors ModelBox: What Is a Specific Factor?Assumptions of the ModelProduction PossibilitiesPrices, Wages, and Labor AllocationRelative Prices and the Distribution of IncomeInternational Trade in the Specific Factors ModelIncome Distribution and the Gains from TradeThe Political Economy of Trade: A Preliminary ViewIncome Distribution and Trade PoliticsCase Study: Trade and UnemploymentInternational Labor MobilityCase Study: Wage Convergence in the Age of Mass MigrationCase Study: Foreign Workers: The Story of the GCCSummaryAPPENDIX TO CHAPTER 4: Further Details on Specific FactorsMarginal and Total ProductRelative Prices and the Distribution of Income⏹Chapter OverviewIn Chapter 3, the Ricardian model of trade was introduced with labor as the single factor of production exhibiting constant returns to scale. Although informative, this model fails to highlight the observed opposition to free trade. In this chapter, the Specific Factors model is presented to gain a better understanding of the distributional effects of trade. After trade, the exporting industry expands, while the import competing industry shrinks. As a result, the factor specific© 2015 Pearson Education Limitedto the exporting industry gains from trade, while the factor specific to the import competing industry loses from trade. However, the aggregate gains from trade are greater than the losses.The Specific Factors model assumes that there is one factor that is mobile between sectors (commonly thought of as labor) and production factors that are specific to each sector. The chapter begins with a simple economy producing two goods: cloth and food. Cloth is produced using labor and its specific factor, capital. Food is produced using labor and its specific factor, land. Given that capital and labor are specific to their respective industries, the mix of goods produced by a country is determined by share of labor employed in each industry. The key difference between the Ricardian model and the Specific Factors model is that in the latter, there are diminishing returns to labor. For example, production of food will increase as labor is added, but given a fixed amount of land, each additional worker will add less and less to food production.As we assume that labor is perfectly mobile between industries, the wage rate must be identical between industries. With competitive labor markets, the wage must be equal to the price of each good times the marginal product of labor in that sector. We can use the common wage rate to show that the economy will produce a mix of goods such that the relative price of one good in terms of the other is equal to the relative cost of that good in terms of the other. Thus, an increase in the relative price of one good will cause the economy to shift its production toward that good.With international trade, the country will export the good whose relative price is below the world relative price. The world relative price may differ from the domestic price before trade for two reasons. First, as in the Ricardian model, countries differ in their production technologies. Second, countries differ in terms of their endowments of the factors specific to each industry. After trade, the domestic relative price will equal the world relative price. As a result, the relative price in the exporting sector will rise, and the relative price in the import competing sector will fall. This will lead to an expansion in the export sector and a contraction of the import competing sector.Suppose that after trade, the relative price of cloth increases by 10 percent. As a result, the country will increase production of cloth. This will lead to a less than 10 percent increase in the wage rate because some workers will move from the food to the cloth industry. The real wage paid to workers in terms of cloth (w/P C) will fall, while the real wage paid in terms of food (w/P F) will rise. The net welfare effect for labor is ambiguous and depends on relative preferences for cloth and food. Owners of capital will unambiguously gain because they pay their workers a lower real wage, while owners of land will unambiguously lose as they now face higher costs. Thus, trade benefits the factor specific to the exporting sector, hurts the factor specific to the import competing sector, and has ambiguous effects on the mobile factor. Despite these asymmetric effects of trade, the overall effect of trade is a net gain. Stated differently, it is theoretically possible to redistribute the gains from trade to those who were hurt by trade and make everyone better off than they were before trade.Given these positive net welfare effects, why is there such opposition to free trade? To answer© 2015 Pearson Education LimitedChapter 4 Specific Factors and Income Distribution 15this question, the chapter looks at the political economy of protectionism. The basic intuition is that the though the total gains exceed the losses from trade, the losses from trade tend to be concentrated, while the gains are diffused. Import tariffs on sugar in the United States are used to illustrate this dynamic. It is estimated that sugar tariffs cost the average person $7 per year. Added up across all people, this is a very large loss from protectionism, but the individual losses are not large enough to induce people to lobby for an end to these tariffs. However, the gains from protectionism are concentrated among a small number of sugar producers, who are able to effectively coordinate and lobby for continued protection. When the losses from trade are concentrated among politically influential groups, import tariffs are likely to be seen. Ohio, a key swing state in U.S. presidential elections and a major producer of both steel and tires, is used as an example to illustrate this point with both Presidents Bush and Obama supporting tariffs on steel and tires, respectively.Although the losers from trade are often able to successfully lobby for protectionism, the chapter highlights three reasons why this is an inefficient method of limiting the losses from trade. First, the actual impact of trade on unemployment is fairly low, with estimates of only 2.5 percent of unemployment directly attributable to international trade. Second, the losses from trade are driven by one industry expanding at the expense of another. This phenomenon is not specific to international trade and is also seen with changing preferences or new technology. Why should policy be singled out to protect people hurt by trade and not for those hurt by these other trends? Finally, it is more efficient to help those hurt by trade—by redistributing the gains from trade in the form of safety nets for those temporarily unemployed and worker retraining programs to ease the transition from import competing to export sectors—than it is to limit trade to protect existing jobs.Finally, the chapter uses the framework of the Specific Factors model to analyze the distributional effects of international labor migration. With free migration of labor across borders, wages must equalize among countries. Workers will migrate from low-wage countries to high-wage countries. As a result, wages in the low-wage countries will rise, and those in the high-wage countries will fall. Though the net effect of free migration is positive, there will be both winners and losers from migration. Workers who stayed behind in the low-wage country will benefit, as will owners of capital in the high-wage country. Workers in the high-wage country will be hurt, as will owners of capital in the low-wage country. We also need to consider the education levels of migrants relative to the country they move to. Immigrants to the United States, for example, tend to be concentrated in the lowest educational groups. Thus, migration is likely to only have negative effects on the wages of the least educated Americans while raising the wages of those with more education.Answers to Textbook Problems1. A country would opt for international trade even though the workers in the importcompetitive sector face the risk of losing their jobs. This is mainly because if the gains that the consumer realizes if more imports were allowed and the associated increase in employment in the export sectors. Under perfect labor mobility, if the real wage inThailand is higher than Bangladesh, then labor movement from Bangladesh to Thailand takes place. This reduces the labor force and raises the wage rates in Bangladesh.Similarly a movement in labor to Thailand increases the labor force and reduces the real wage rate in Thailand. The movement between two countries will continue until the wages in these two countries are equalized.2. a.b.The curve in the PPF reflects diminishing returns to labor. As production of Q1increases, the opportunity cost of producing an additional unit of Q1 will rise. Basically,as you increase the number of workers producing Q1 with a fixed supply of capital, each additional worker will contribute less to the production of Q1 and represents anincreasingly large loss of potential production of Q2.3. a. Draw the marginal product of labor times the price for each sector given that the totallabor allocated between these sectors must sum to 100. Thus, if there are 10 workers© 2015 Pearson Education LimitedChapter 4 Specific Factors and Income Distribution 17employed in Sector 1, then there are 90 workers employed in Sector 2. If there are 50workers employedin Sector 1, then there are 50 workers employed in Sector 2. For simplicity, define P 1 = 1 andP 2 = 2 (it does not matter what the actual prices are in determining the allocation oflabor, only that the relative price P 2/P 1 =2).In competitive labor markets, the wage is equal to price times the marginal product oflabor. With mobile labor between sectors, the wage rate must be equal betweensectors. Thus, the equilibrium wage is determined by the intersection of the two P ⨯MPL curves. Looking at the diagram above,it appears that this occurs at a wage rate of 10 and a labor supply of 30 workers inSector 1(70 workers in Sector 2).b. From part (a), we know that 30 units of labor are employed in Sector 1 and 70 units oflabor are employed in Sector 2. Looking at the table in Question 2, we see that theselabor allocations will produce 48.6 units of good 1 and 86.7 units of good 2.At this production point (Q 1 = 48.6, Q 2 = 86.7), the slope of the PPF must be equal to-P 1/P 2, which is -½. Looking at the PPF in Question 2a, we see that it is roughly equalto -½.© 2015 Pearson Education Limitedc. If the relative price of good 2 falls to 1.3, we simply need to redraw the P ⨯ MPLdiagram withP 1 = 1 and P 2 =1.3.The decrease in the price of good 2 leads to an increase in the share of labor accruingto Sector 1. Now, the two sectors have equal wages (P ⨯ MPL ) when there are 50workers employed in both sectors.Looking at the table in Question 2, we see that with 50 workers employed in bothSectors 1 and 2, there will be production of Q 1 = 66 and Q 2 = 75.8.The PPF at the production point Q 1 = 66, Q 2 = 75.78 must have a slope of -P 1/P 2 = -1/1.3 = -0.77. d. The decrease in the relative price of good 2 led to an increase in production of good 1and a decrease in the production of good 2. The expansion of Sector 1 increases the income of the factor specific to Sector 1 (capital). The contraction of Sector 2decreases the income of thefactor specific to Sector 2 (land).Chapter 4 Specific Factors and Income Distribution 194. a. The increase in the capital stock in Home will increase the possible production of good 1,but have no effect on the production of good 2 because good 2 does not use capital inproduction. As a result, the PPF shifts out to the right, representing the greaterquantity of good 1 that Home can now produce.b. Given the increased production possibility for Home, the relative supply of home (definedas Q 1/Q 2) is further to the right than the relative supply for Foreign. As a result, therelative price of good 1 is lower in Home than it is in Foreign.c. If both countries open to trade, Home will export good 1, and Foreign will export good 2.d. Owners of capital in Home and owners of land in Foreign will benefit from trade, whileowners of land in Home and owners of capital in Foreign will be hurt. The effects onlabor will be ambiguous because the real wage in terms of good 1 will fall (rise) in Home(Foreign) and the real wage in terms of good 2 will rise (fall) in Home (Foreign). The net welfare effect for labor will depend on preferences in each country. For example, iflabor in Home consumes relatively more of good 2, they will gain from trade. If labor in Home consumes relatively more of good 1, they will lose from trade.5. The real wage in Home is 10, while real wage in Foreign is 18. If there is free movement oflabor, then workers will migrate from Home to Foreign until the real wage is equal in each country. If 4 workers move from Home to Foreign, then there will be 7 workers employed in each country, earning a real wage of 14 in each country.We can find total production by adding up the marginal product of each worker. After trade, total production is 20 + 19 + 18 + 17 + 16 + 15 + 14 = 119 in each country for total world production of 238. Before trade, production in Home was 20 + 19 + 18 = 57. Production in Foreign was 20 + 19 + … + 10 = 165. Total world production before trade was 57 + 165 = 222. Thus, trade increased total output by 16.Workers in Home benefit from migration, while workers in Foreign are hurt. Landowners in Home are hurt by migration (their costs rise), while landowners in Foreign benefit.6. If only 2 workers can move from Home to Foreign, there will be a real wage of 12 in Homeanda real wage of 16 in Foreign.a. Workers in Foreign are hurt as their wage falls from 18 to 16.b. Landowners in Foreign benefit as their costs fall by 2 for each worker employed.c. Workers who stay at home benefit as their wage rises from 10 to 12.d. Landowners in Home are hurt as their costs rise by 2 for each worker employed.e. The workers who do move benefit by seeing their wages rise from 10 to 16.7. If the price of wheat increases by 10%, then the labor demand in the wheat sector wouldincrease by the same 10 percent. In other words, the curve defined by MPLw × Pw would increase by 10 percent. On the other hand, if the price of paddy remains the same and only there is an increase in the price of wheat, this result in an increase in the wage rate less than the increase in the price of wheat. In the present case the wage rate will increase less than 10 percent.© 2015 Pearson Education Limited。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Chapter 4Specific Factors and Income Distribution⏹Chapter OrganizationThe Specific Factors ModelBox: What Is a Specific Factor?Assumptions of the ModelProduction PossibilitiesPrices, Wages, and Labor AllocationRelative Prices and the Distribution of IncomeInternational Trade in the Specific Factors ModelIncome Distribution and the Gains from TradeThe Political Economy of Trade: A Preliminary ViewIncome Distribution and Trade PoliticsCase Study: Trade and UnemploymentInternational Labor MobilityCase Study: Wage Convergence in the Age of Mass MigrationCase Study: Foreign Workers: The Story of the GCCSummaryAPPENDIX TO CHAPTER 4: Further Details on Specific FactorsMarginal and Total ProductRelative Prices and the Distribution of Income⏹Chapter OverviewIn Chapter 3, the Ricardian model of trade was introduced with labor as the single factor of production exhibiting constant returns to scale. Although informative, this model fails to highlight the observed opposition to free trade. In this chapter, the Specific Factors model is presented to gain a better understanding of the distributional effects of trade. After trade, the exporting industry expands, while the import competing industry shrinks. As a result, the factor specific© 2015 Pearson Education Limitedto the exporting industry gains from trade, while the factor specific to the import competing industry loses from trade. However, the aggregate gains from trade are greater than the losses.The Specific Factors model assumes that there is one factor that is mobile between sectors (commonly thought of as labor) and production factors that are specific to each sector. The chapter begins with a simple economy producing two goods: cloth and food. Cloth is produced using labor and its specific factor, capital. Food is produced using labor and its specific factor, land. Given that capital and labor are specific to their respective industries, the mix of goods produced by a country is determined by share of labor employed in each industry. The key difference between the Ricardian model and the Specific Factors model is that in the latter, there are diminishing returns to labor. For example, production of food will increase as labor is added, but given a fixed amount of land, each additional worker will add less and less to food production.As we assume that labor is perfectly mobile between industries, the wage rate must be identical between industries. With competitive labor markets, the wage must be equal to the price of each good times the marginal product of labor in that sector. We can use the common wage rate to show that the economy will produce a mix of goods such that the relative price of one good in terms of the other is equal to the relative cost of that good in terms of the other. Thus, an increase in the relative price of one good will cause the economy to shift its production toward that good.With international trade, the country will export the good whose relative price is below the world relative price. The world relative price may differ from the domestic price before trade for two reasons. First, as in the Ricardian model, countries differ in their production technologies. Second, countries differ in terms of their endowments of the factors specific to each industry. After trade, the domestic relative price will equal the world relative price. As a result, the relative price in the exporting sector will rise, and the relative price in the import competing sector will fall. This will lead to an expansion in the export sector and a contraction of the import competing sector.Suppose that after trade, the relative price of cloth increases by 10 percent. As a result, the country will increase production of cloth. This will lead to a less than 10 percent increase in the wage rate because some workers will move from the food to the cloth industry. The real wage paid to workers in terms of cloth (w/P C) will fall, while the real wage paid in terms of food (w/P F) will rise. The net welfare effect for labor is ambiguous and depends on relative preferences for cloth and food. Owners of capital will unambiguously gain because they pay their workers a lower real wage, while owners of land will unambiguously lose as they now face higher costs. Thus, trade benefits the factor specific to the exporting sector, hurts the factor specific to the import competing sector, and has ambiguous effects on the mobile factor. Despite these asymmetric effects of trade, the overall effect of trade is a net gain. Stated differently, it is theoretically possible to redistribute the gains from trade to those who were hurt by trade and make everyone better off than they were before trade.Given these positive net welfare effects, why is there such opposition to free trade? To answer© 2015 Pearson Education LimitedChapter 4 Specific Factors and Income Distribution 15this question, the chapter looks at the political economy of protectionism. The basic intuition is that the though the total gains exceed the losses from trade, the losses from trade tend to be concentrated, while the gains are diffused. Import tariffs on sugar in the United States are used to illustrate this dynamic. It is estimated that sugar tariffs cost the average person $7 per year. Added up across all people, this is a very large loss from protectionism, but the individual losses are not large enough to induce people to lobby for an end to these tariffs. However, the gains from protectionism are concentrated among a small number of sugar producers, who are able to effectively coordinate and lobby for continued protection. When the losses from trade are concentrated among politically influential groups, import tariffs are likely to be seen. Ohio, a key swing state in U.S. presidential elections and a major producer of both steel and tires, is used as an example to illustrate this point with both Presidents Bush and Obama supporting tariffs on steel and tires, respectively.Although the losers from trade are often able to successfully lobby for protectionism, the chapter highlights three reasons why this is an inefficient method of limiting the losses from trade. First, the actual impact of trade on unemployment is fairly low, with estimates of only 2.5 percent of unemployment directly attributable to international trade. Second, the losses from trade are driven by one industry expanding at the expense of another. This phenomenon is not specific to international trade and is also seen with changing preferences or new technology. Why should policy be singled out to protect people hurt by trade and not for those hurt by these other trends? Finally, it is more efficient to help those hurt by trade—by redistributing the gains from trade in the form of safety nets for those temporarily unemployed and worker retraining programs to ease the transition from import competing to export sectors—than it is to limit trade to protect existing jobs.Finally, the chapter uses the framework of the Specific Factors model to analyze the distributional effects of international labor migration. With free migration of labor across borders, wages must equalize among countries. Workers will migrate from low-wage countries to high-wage countries. As a result, wages in the low-wage countries will rise, and those in the high-wage countries will fall. Though the net effect of free migration is positive, there will be both winners and losers from migration. Workers who stayed behind in the low-wage country will benefit, as will owners of capital in the high-wage country. Workers in the high-wage country will be hurt, as will owners of capital in the low-wage country. We also need to consider the education levels of migrants relative to the country they move to. Immigrants to the United States, for example, tend to be concentrated in the lowest educational groups. Thus, migration is likely to only have negative effects on the wages of the least educated Americans while raising the wages of those with more education.Answers to Textbook Problems1. A country would opt for international trade even though the workers in the importcompetitive sector face the risk of losing their jobs. This is mainly because if the gains that the consumer realizes if more imports were allowed and the associated increase in employment in the export sectors. Under perfect labor mobility, if the real wage inThailand is higher than Bangladesh, then labor movement from Bangladesh to Thailand takes place. This reduces the labor force and raises the wage rates in Bangladesh.Similarly a movement in labor to Thailand increases the labor force and reduces the real wage rate in Thailand. The movement between two countries will continue until the wages in these two countries are equalized.2. a.b.The curve in the PPF reflects diminishing returns to labor. As production of Q1increases, the opportunity cost of producing an additional unit of Q1 will rise. Basically,as you increase the number of workers producing Q1 with a fixed supply of capital, each additional worker will contribute less to the production of Q1 and represents anincreasingly large loss of potential production of Q2.3. a. Draw the marginal product of labor times the price for each sector given that the totallabor allocated between these sectors must sum to 100. Thus, if there are 10 workers© 2015 Pearson Education LimitedChapter 4 Specific Factors and Income Distribution 17employed in Sector 1, then there are 90 workers employed in Sector 2. If there are 50workers employedin Sector 1, then there are 50 workers employed in Sector 2. For simplicity, define P 1 = 1 andP 2 = 2 (it does not matter what the actual prices are in determining the allocation oflabor, only that the relative price P 2/P 1 =2).In competitive labor markets, the wage is equal to price times the marginal product oflabor. With mobile labor between sectors, the wage rate must be equal betweensectors. Thus, the equilibrium wage is determined by the intersection of the two P ⨯MPL curves. Looking at the diagram above,it appears that this occurs at a wage rate of 10 and a labor supply of 30 workers inSector 1(70 workers in Sector 2).b. From part (a), we know that 30 units of labor are employed in Sector 1 and 70 units oflabor are employed in Sector 2. Looking at the table in Question 2, we see that theselabor allocations will produce 48.6 units of good 1 and 86.7 units of good 2.At this production point (Q 1 = 48.6, Q 2 = 86.7), the slope of the PPF must be equal to-P 1/P 2, which is -½. Looking at the PPF in Question 2a, we see that it is roughly equalto -½.© 2015 Pearson Education Limitedc. If the relative price of good 2 falls to 1.3, we simply need to redraw the P ⨯ MPLdiagram withP 1 = 1 and P 2 =1.3.The decrease in the price of good 2 leads to an increase in the share of labor accruingto Sector 1. Now, the two sectors have equal wages (P ⨯ MPL ) when there are 50workers employed in both sectors.Looking at the table in Question 2, we see that with 50 workers employed in bothSectors 1 and 2, there will be production of Q 1 = 66 and Q 2 = 75.8.The PPF at the production point Q 1 = 66, Q 2 = 75.78 must have a slope of -P 1/P 2 = -1/1.3 = -0.77. d. The decrease in the relative price of good 2 led to an increase in production of good 1and a decrease in the production of good 2. The expansion of Sector 1 increases the income of the factor specific to Sector 1 (capital). The contraction of Sector 2decreases the income of thefactor specific to Sector 2 (land).Chapter 4 Specific Factors and Income Distribution 194. a. The increase in the capital stock in Home will increase the possible production of good 1,but have no effect on the production of good 2 because good 2 does not use capital inproduction. As a result, the PPF shifts out to the right, representing the greaterquantity of good 1 that Home can now produce.b. Given the increased production possibility for Home, the relative supply of home (definedas Q 1/Q 2) is further to the right than the relative supply for Foreign. As a result, therelative price of good 1 is lower in Home than it is in Foreign.c. If both countries open to trade, Home will export good 1, and Foreign will export good 2.d. Owners of capital in Home and owners of land in Foreign will benefit from trade, whileowners of land in Home and owners of capital in Foreign will be hurt. The effects onlabor will be ambiguous because the real wage in terms of good 1 will fall (rise) in Home(Foreign) and the real wage in terms of good 2 will rise (fall) in Home (Foreign). The net welfare effect for labor will depend on preferences in each country. For example, iflabor in Home consumes relatively more of good 2, they will gain from trade. If labor in Home consumes relatively more of good 1, they will lose from trade.5. The real wage in Home is 10, while real wage in Foreign is 18. If there is free movement oflabor, then workers will migrate from Home to Foreign until the real wage is equal in each country. If 4 workers move from Home to Foreign, then there will be 7 workers employed in each country, earning a real wage of 14 in each country.We can find total production by adding up the marginal product of each worker. After trade, total production is 20 + 19 + 18 + 17 + 16 + 15 + 14 = 119 in each country for total world production of 238. Before trade, production in Home was 20 + 19 + 18 = 57. Production in Foreign was 20 + 19 + … + 10 = 165. Total world production before trade was 57 + 165 = 222. Thus, trade increased total output by 16.Workers in Home benefit from migration, while workers in Foreign are hurt. Landowners in Home are hurt by migration (their costs rise), while landowners in Foreign benefit.6. If only 2 workers can move from Home to Foreign, there will be a real wage of 12 in Homeanda real wage of 16 in Foreign.a. Workers in Foreign are hurt as their wage falls from 18 to 16.b. Landowners in Foreign benefit as their costs fall by 2 for each worker employed.c. Workers who stay at home benefit as their wage rises from 10 to 12.d. Landowners in Home are hurt as their costs rise by 2 for each worker employed.e. The workers who do move benefit by seeing their wages rise from 10 to 16.7. If the price of wheat increases by 10%, then the labor demand in the wheat sector wouldincrease by the same 10 percent. In other words, the curve defined by MPLw × Pw would increase by 10 percent. On the other hand, if the price of paddy remains the same and only there is an increase in the price of wheat, this result in an increase in the wage rate less than the increase in the price of wheat. In the present case the wage rate will increase less than 10 percent.© 2015 Pearson Education Limited。