新加坡公司法SEC9

新加坡兼并守则

新加坡兼并守则全文共四篇示例,供读者参考第一篇示例:新加坡兼并守则是指一系列法规和规定,旨在监管和规范公司之间的合并、收购和兼并活动。

这些规则旨在确保透明度、公平竞争和维护投资者利益。

本文将就新加坡兼并守则的背景、内容和实施情况进行详细介绍。

一、背景新加坡是一个投资兴起和经济活跃的国家,吸引了大量国际投资者和企业来此投资和经商。

随着全球化趋势的加强,各行各业的竞争日益激烈,公司之间的合并、收购和兼并活动也愈发频繁。

为了保护各方的利益,维护市场秩序,新加坡政府逐渐建立和完善了一套兼并守则。

二、内容1.兼并守则适用范围新加坡兼并守则适用于所有在新加坡上市的公司,并规定了兼并和收购的程序、条件和监管要求。

2.核准程序根据新加坡兼并守则,任何公司在进行合并、收购和兼并之前,必须向相关监管机构提出申请,获得核准。

3.信息披露要求在进行兼并活动时,公司必须按照新加坡法律和兼并守则的规定,及时向投资者和公众披露相关信息,确保透明度。

4.公平竞争原则新加坡兼并守则规定,所有的兼并和收购活动必须遵循公平竞争原则,不得利用信息不对称或其他不正当手段获取优势。

5.投资者保护为了保护投资者的权益,新加坡兼并守则规定,公司在进行兼并和收购活动时,必须充分考虑投资者的利益,保证他们合法权益不受损害。

6.违规处罚新加坡兼并守则对违反兼并规定的公司和个人给予严厉处罚,包括罚款、停牌和其他惩罚措施。

三、实施情况新加坡兼并守则的实施情况良好,得到了广泛认可和遵守。

通过该守则的规范,有效防范了不法分子利用兼并活动谋取私利,保护了广大投资者的权益,促进了市场竞争和企业发展。

总结新加坡兼并守则是新加坡特有的监管制度,具有一定的独特性和先进性。

通过该守则的落实,不仅规范了公司之间的兼并活动,还保护了投资者的利益,维护了市场秩序,促进了全球投资者对新加坡市场的信心。

相信在新的形势下,新加坡兼并守则将不断完善和发展,为新加坡经济的健康发展提供坚实保障。

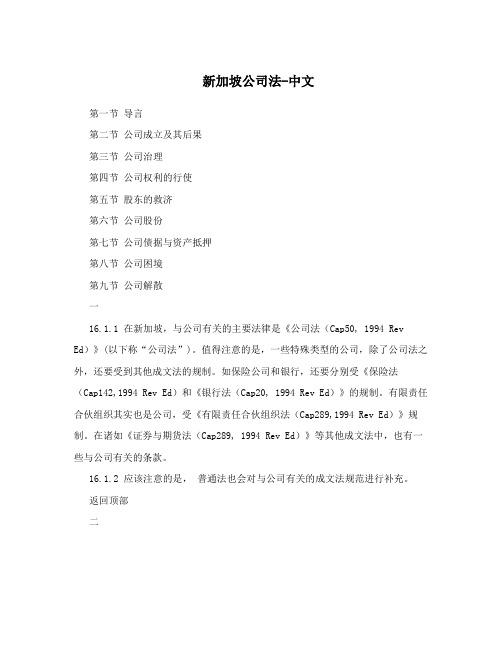

新加坡公司法-中文

新加坡公司法-中文第一节导言第二节公司成立及其后果第三节公司治理第四节公司权利的行使第五节股东的救济第六节公司股份第七节公司债据与资产抵押第八节公司困境第九节公司解散一16.1.1 在新加坡,与公司有关的主要法律是《公司法(Cap50, 1994 Rev Ed)》(以下称“公司法”)。

值得注意的是,一些特殊类型的公司,除了公司法之外,还要受到其他成文法的规制。

如保险公司和银行,还要分别受《保险法(Cap142,1994 Rev Ed)和《银行法(Cap20, 1994 Rev Ed)》的规制。

有限责任合伙组织其实也是公司,受《有限责任合伙组织法(Cap289,1994 Rev Ed)》规制。

在诸如《证券与期货法(Cap289, 1994 Rev Ed)》等其他成文法中,也有一些与公司有关的条款。

16.1.2 应该注意的是,普通法也会对与公司有关的成文法规范进行补充。

返回顶部二16.2.1 根据公司法第17(3)条的规定,拥有20名以上成员的经营组织都必须设立为公司。

但该规定并不适用于那些遵照新加坡其他成文法设立的,由从事特定职业的个人组成的合伙组织(公司法第17(3)条)。

法律职业的从业者,受《法律职业法(Cap161,1994 Rev Ed)》的规制,他们可以设立成员超过20人的合伙组织。

16.2.2 一般来说,只要提交相应的文件,缴纳规定的费用,任何人都可以在新加坡通过登记设立公司。

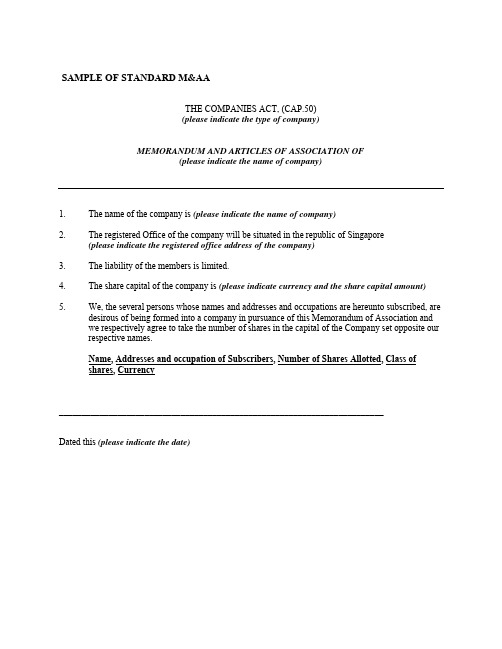

设立公司时,必须提交的最重要的文件是公司章程和组织规章,公司法第19(1)条对此作了强制性要求。

公司章程和组织规章就是公司的宪章。

根据公司法第22(1)条的规定,公司章程必须载明公司名称、公司股本[如果有的话],并表明公司成员承担的是有限责任还是无限责任。

公司组织规章是公司的规章制度,其中也有与公司治理有关的规定。

如果公司章程和组织规章有冲突,前者有优先效力。

16.2.3 公司章程一经登记,登记官便签发设立通知,宣布公司成立并在通知中载明成立的日期。

公司章程-新加坡

3. Subject to the Act, any preference shares may, with the sanction of an ordinary resolution, be issued on the terms that they are, or at the option of the company are liable, to be redeemed.

7. Except as required by law, no person shall be recognised by the company as holding any share upon any trust, and the company shall not be bound by or be compelled in any way to recognise (even when having notice thereof) any equitable, contingent, future or partial interest in any share or unit of a share or (except only as by these Regulations or by law otherwise provided) any other rights in respect of any share except an absolute right to the entirety thereof in the registered holder.

新加坡公司章程中文译本

新加坡公司章程中文译本第一章:总则第一条:公司名称本公司名称为[公司名称](以下简称“公司”),为依照新加坡公司法注册的有限责任公司。

第二条:公司地址公司的地址为[公司地址],或者根据董事长的决定在其他地方。

第三条:业务范围本公司的业务范围主要包括[业务范围]等。

第四条:股东责任本公司的股东将按照出资额承担责任。

第五条:总经理本公司设有总经理一人,由股东大会选举产生。

第二章:股东第六条:股东资格任何自然人、法人都有资格成为本公司的股东。

第七条:股份分配公司的股份可以自由转让和分配。

第三章:公司管理第八条:股东大会本公司的最高权力机关为股东大会,股东大会每年至少召开一次。

第九条:董事会本公司设有董事会,由股东大会选举产生。

董事会负责制定公司的战略规划和决策。

第十条:监事会本公司设有监事会,由股东大会选举产生。

监事会负责监督公司的财务和经营情况。

第十一条:总经理本公司的总经理负责日常的管理和运营工作,向董事会和股东大会汇报工作情况。

第四章:财务管理第十二条:财务报告本公司每年编制财务报告并提交给股东大会审议。

第十三条:分红公司每年根据盈利情况决定是否进行分红。

第十四条:财务审计公司每年进行财务审计,确保财务报告的真实性和准确性。

第五章:章程修改第十五条:章程修改对公司章程的修改必须经过股东大会的批准,并按照法律和公司章程的规定进行。

第六章:解散和清算第十六条:公司解散公司可能因经营不善、法律原因或其他决定而解散。

第十七条:清算公司解散后进行清算,清偿债务,并将剩余资产按照股东的权益进行分配。

第七章:其他事项第十八条:争议解决对于公司相关的争议,应当通过协商或者诉讼解决。

第十九条:生效本公司章程经股东大会批准后生效,并向相关机构备案。

第二十条:其他事项若本章程未涉及的事项,应根据新加坡公司法的规定进行处理。

公司治理案例分析-淡马锡模式

三、淡马锡公司治理

董事会 4名政府公务员+9名民间企业家

执行委员会

检查所有国联企业的重大项目投资事项 管理层 业务活动具体实施

财政(审计)委员会

监督公司在股票和资本市场上的投资活动

根据公司章程规定,公司仅高层领导(董事长、总裁)的任命 需经财政部复审、报总统批准,其余董事没有一个是政府派出的, 没有一位是现任的官员,全部都是市场化的人才担任。

二、淡马锡模式

淡马锡模式的核心就是董事会制度,它实现了政企分 开和决策层同经理层的分开。淡马锡控股公司不受政府决 策干扰,拥有淡马锡100%所有权的新加坡财政部在公司内 部的作用很小,真正起到关键作用的是公司特殊的董事会 架构,淡马锡与其旗下企业的关系也是如此,不直接介入 其经营决策,只是通过董事会来对其进行管理,这是一种 分层递进的控制方式和有效的约束机制。 淡马锡控股公司的经营宗旨就是以客户为导向,利用 雄厚的国家财政实力做后盾,批量处理中小企业贷款担保 申请、审批、放贷及风险控制,即建立“信贷工厂”,提 供中小企业融资。

工作经历

陈育宠 (Bobby CHIN YC) 吴友仁 (GOH Yew Lin)

自2014年6月起 自2005年8月起 2002年5月起任执行董事; 2004年1月起任首席执行长 自2010年1月起 自2014年6月起 自2006年10月起

公司现任执行董事兼CEO由现 任新加坡总理李显龙的妻子何晶女 士担任。公司董事会目前共由13名 董事组成,4名为政府公务员,另外 9名为企业界人士,其中大部分是非 执行董事,都是来自独立私营企业 的商界领袖。

的控股地位。国家以股东身份行使国有资产的所有权,通

过任免董事长、董事以及同企业签订计划合同等方式来主 导企业发展方向。

新加坡公司法

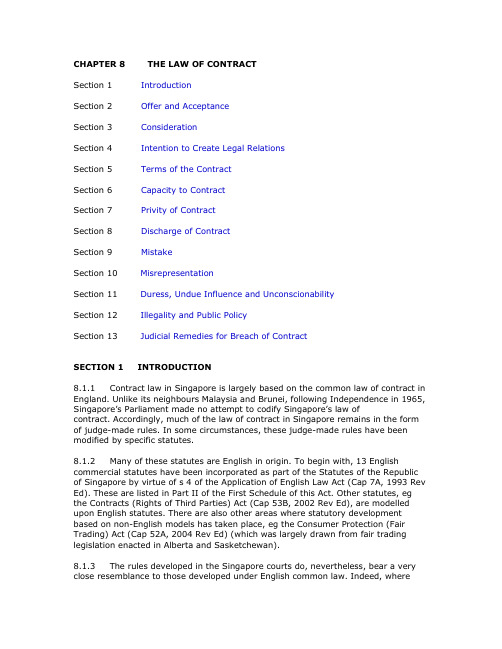

CHAPTER 8 THE LAW OF CONTRACTSection 1 IntroductionSection 2 Offer and AcceptanceSection 3 ConsiderationSection 4 Intention to Create Legal RelationsSection 5 Terms of the ContractSection 6 Capacity to ContractSection 7 Privity of ContractSection 8 Discharge of ContractSection 9 MistakeSection 10 MisrepresentationSection 11 Duress, Undue Influence and UnconscionabilitySection 12 Illegality and Public PolicySection 13 Judicial Remedies for Breach of ContractSECTION 1 INTRODUCTION8.1.1 Contract law in Singapore is largely based on the common law of contract in England. Unlike its neighbours Malaysia and Brunei, following Independence in 1965, Singapore’s Parliament made no attempt to codify Singapore’s law ofcontract. Accordingly, much of the law of contract in Singapore remains in the form of judge-made rules. In some circumstances, these judge-made rules have been modified by specific statutes.8.1.2 Many of these statutes are English in origin. To begin with, 13 English commercial statutes have been incorporated as part of the Statutes of the Republic of Singapore by virtue of s 4 of the Application of English Law Act (Cap 7A, 1993 Rev Ed). These are listed in Part II of the First Schedule of this Act. Other statutes, eg the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act (Cap 53B, 2002 Rev Ed), are modelled upon English statutes. There are also other areas where statutory development based on non-English models has taken place, eg the Consumer Protection (Fair Trading) Act (Cap 52A, 2004 Rev Ed) (which was largely drawn from fair trading legislation enacted in Alberta and Sasketchewan).8.1.3 The rules developed in the Singapore courts do, nevertheless, bear a very close resemblance to those developed under English common law. Indeed, wherethere is no Singapore authority specifically on point, it will usually be assumed that the position will, in the first instance, be no different from that in England.Return to the topSECTION 2 OFFER AND ACCEPTANCEAgreement8.2.1 A contract is essentially an agreement between two or more parties, the terms of which affect their respective rights and obligations which are enforceable at law. Whether the parties have reached agreement, or a meeting of the minds, is objectively ascertained from the facts. The concepts of offer and acceptance provide in many, albeit not all, cases the starting point for analysing whether agreement has been reached.Offer8.2.2 An offer is a promise, or other expression of willingness, by the ‘offeror’ to be bound on certain specified terms upon the unqualified acceptance of these terms by the person to whom the offer is made (the ‘offeree’). Provided the other formation elements (ie consideration and intention to create legal relations) are present, the acceptance of an offer results in a valid contract.8.2.3 Whether any particular statement amounts to an offer depends on the intention with which it is made. An offer must be made with the intention to be bound. On the other hand, if a person is merely soliciting offers or requesting for information, without any intention to be bound, at best, he or she would be making an invitation to treat. Under the objective test, a person may be said to have made an offer if his or her statement (or conduct) induces a reasonable person to believe that the person making the offer intends to be bound by the acceptance of the alleged offer, even if that person in fact had no such intention.Termination of Offer8.2.4 An offer may be terminated by withdrawal at any time prior to its acceptance, provided there is communication, of the withdrawal to the offeree, whether by the offeror or through some reliable source. Rejection of an offer, which includes the making of a counter-offer or a variation of the original terms, terminates the offer. In the absence of an express stipulation as to time, an offer will lapse after a reasonable time. What this amounts to depends on the particular facts of the case. Death of the offeror, if known to the offeree, would render the offer incapable of being accepted by the offeree. Even in the absence of such knowledge, death of either party terminates any offer which has a personal element.Acceptance8.2.5 An offer is accepted by the unconditional and unqualified assent to its terms by the offeree. This assent may be expressed through words or conduct, but cannot be inferred from mere silence save in very exceptional circumstances.8.2.6 As a general rule, acceptance must be communicated to the offeror, although a limited exception exists where the acceptance is sent by post and this method of communication is either expressly or impliedly authorised. This exception, known as the ‘postal acceptance rule’, stipulates that acceptance takes place at the point when the letter of acceptance is posted, whether or not it was in fact received by the offeror.Certainty8.2.7 Before the agreement may be enforced as a contract, its terms must be sufficiently certain. At the least, the essential terms of the agreement should be specified. Beyond this, the courts may resolve apparent vagueness or uncertainty by reference to the acts of the parties, a previous course of dealing between the parties, trade practice or to a standard of reasonableness. On occasion, statutory provision of contractual details may fill the gaps. For more on implication of terms, see Paragraphs 8.5.5 to 8.5.8 below.Completeness8.2.8 An incomplete agreement also cannot amount to an enforceablecontract. Agreements made ‘subject to contract’ may be considered incomplete if the intention of the parties, as determined from the facts, was not to be legally bound until the execution of a formal document or until further agreement is reached.Electronic Transactions Act8.2.9 The Electronic Transactions Act (Cap 88, 1999 Rev Ed) (‘ETA’) clarifies that, except with respect to the requirement of writing or signatures in wills, negotiable instruments, indentures, declarations of trust or powers of attorney, contracts involving immovable property and documents of title (s 4(1)), electronic records may be used in expressing an offer or acceptance of an offer in contract formation (s 11). A declaration of intent between contracting parties may also be made in the form of an electronic record (s 12). The ETA also clarifies when an electronic record may be attributed to a particular person (s 13) and how the time and place of despatch and receipt of an electronic record are to be determined (s 15).Return to the topSECTION 3 CONSIDERATIONDefinition8.3.1 A promise contained in an agreement is not enforceable unless it is supported by consideration or it is made in a written document made underseal. Consideration is something of value (as defined by the law), requested for bythe party making the promise (the ‘promisor’) and provided by the party who receives it (the ‘promisee’), in exchange for the promise that the promisee is seeking to enforce. Thus, it could consist of either some benefit received by the promisor, or some detriment to the promisee. This benefit/detriment may consist of a counter promise or a completed act.Reciprocity8.3.2 The idea of reciprocity that underlies the requirement for consideration means that there has to be some causal relation between the consideration and the promise itself. Thus, consideration cannot consist of something that was already done before the promise was made. However, the courts do not always adopt a strict chronological approach to the analysis.Sufficiency8.3.3 Whether the consideration provided is sufficient is a question of law, and the court is not, as a general rule, concerned with whether the value of the consideration is commensurate with the value of the promise. The performance of, or the promise to perform, an existing public duty imposed on the promisee does not, without more, constitute sufficient consideration in law to support the promisor’s promise. The performance of an existing obligation that is owed contractually to the promisor is capable of being sufficient consideration, if such performance confers a real and practical benefit on the promisor. If the promisee performs or promises to perform an existing contractual obligation that is owed to a third party, the promisee will have furnished sufficient consideration at law to support a promise given in exchange.Promissory Estoppel8.3.4 Where the doctrine of promissory estoppel applies, a promise may be binding notwithstanding that it is not supported by consideration. This doctrine applies where a party to a contract makes an unequivocal promise, whether by words or conduct, that he or she will not insist on his or her strict legal rights under the contract, and the other party acts, and thereby alters his or her position, in reliance on the promise. The party making the promise cannot seek to enforce those rights if it would be inequitable to do so, although such rights may be reasserted upon the promisor giving reasonable notice. The doctrine prevents the enforcement of existing rights, but does not create new causes of action.Return to the topSECTION 4 INTENTION TO CREATE LEGAL RELATIONSContractual Intention8.4.1 In the absence of contractual intention, an agreement, even if supported by consideration, cannot be enforced. Whether the parties to an agreement intended tocreate legally binding relations between them is a question determined by an objective assessment of the relevant facts.Commercial Arrangements8.4.2 In the case of agreements in a commercial context, the courts will generally presume that the parties intended to be legally bound. However, the presumption can be displaced where the parties expressly declare the contrary intention. This is often done through the use of honour clauses, letters of intent, memoranda of understanding and other similar devices, although the ultimate conclusion would depend, not on the label attached to the document, but on an objective assessment of the language used and on all the attendant facts.Social Arrangements8.4.3 The parties in domestic or social arrangements are generally presumed not to intend legal consequences.Return to the topSECTION 5 TERMS OF THE CONTRACTExpress Terms8.5.1 The rights and obligations of contracting parties are determined by first, ascertaining the terms of the contract, and secondly, interpreting those terms. In ascertaining the terms of a contract, it is sometimes necessary, especially where the contract has not been reduced to writing, to decide whether a particular statement is a contractual term or a mere representation. Whether a statement is contractual or not depends on the intention of the parties, objectively ascertained, and is a question of fact. In ascertaining the parties’ intention, the courts take into account a number of factors including the stage of the transaction at which the statement was made, the importance which the representee attached to the statement and the relative knowledge or skill of the parties vis-à-vis the subject matter of the statement.8.5.2 Once the terms of a contract have been determined, the court applies an objective test in construing or interpreting the meaning of these terms. What is significant in this determination therefore is not the sense attributed by either party to the words used, but how a reasonable person would understand those terms. In this regard, Singapore courts have consistently emphasised the importance of the factual matrix within which the contract was made, as this would assist in determining how a reasonable man would have understood the language of the document.8.5.3 Where the parties have reduced their agreement into writing, whether a particular statement (oral or written) forms part of the actual contract depends on the application of the parol evidence rule. In Singapore, this common law rule and its main exceptions are codified in s 93 and s 94 of the Evidence Act (Cap 97, 1997 Rev Ed). Section 93 provides that where ‘the terms of a contract…have been reduced …tothe form of a document…, no evidence shall be given in proof of the terms of such contract …except the document itself’. Thus, no evidence of any oral agreement or statement may be admitted in evidence to contradict, vary, add to, or subtract from the terms of the written contract. However, secondary evidence is admissible if it falls within one of the exceptions to this general rule found in the proviso to s94. Some controversy remains as to whether s 94 is an exhaustive statement of all exceptions to the rule, or whether other common law exceptions not explicitly covered in s 94 continue to be applicable.8.5.4 It should, however, be noted that the scope of s 93 and s 94 has been circumscribed by Parliament in certain circumstances.Implied Terms8.5.5 In addition to those expressly agreed terms, the court may sometimes imply terms into the contract.8.5.6 Generally, any term to be implied must not contradict any express term of the contract.8.5.7 Where a term is implied to fill a gap in the contract so as to give effect to the presumed intention of the parties, the term is implied in fact and depends on a consideration of the language of the contract as well as the surrounding circumstances. A term will be implied only if it is so necessary that both parties must have intended its inclusion in the contract. The fact that it would be reasonable to include the term is not sufficient for the implication, as the courts will not re-write the contract for the parties.8.5.8 Terms may also be implied because this is required statutorily, or on public policy considerations. The terms implied by the Sale of Goods Act (Cap 393, 1994 Rev Ed) (eg s 12(1) – that the seller of goods has a right to sell the goods) provide examples of the former type of implied terms. As for the latter, whilst there has been no specific authority on the point, it is not inconceivable that Singapore courts, like their English counterparts, may imply ‘default’ terms into specific classes of contracts to give effect to policies that define the contractual relationships that arise out of those contracts.Classification of Terms8.5.9 The terms of a contract may be classified into conditions, warranties or intermediate (or innominate) terms. Proper classification is important as it determines whether the contract may be discharged or terminated for breach [as to which see Paragraphs 8.8.11 to 8.8.12 below].8.5.10 The parties may expressly stipulate in the contract how a particular term is to be classed. This is not, however, conclusive unless the parties are found to have intended the technical meaning of the classifying words used. In the absence of express stipulation, the courts will look objectively at the language of the contract to determine how, in light of the surrounding circumstances, the parties intended a particular term to be classed. There are also instances where statutes may stipulatewhether certain kinds of terms are to be treated as conditions or warranties, in the absence of any specific designation by the contracting parties.Exception Clauses8.5.11 Exception clauses that seek to exclude or limit a contracting party’s liability are commonly, but not exclusively, found in standard form agreements. The law in Singapore relating to such clauses is essentially based on English law. The English Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977, which either invalidates an exception clause or limits the efficacy of such terms by imposing a requirement of reasonableness, has been re-enacted in Singapore as the Unfair Contract Terms Act (as Cap 396, 1994 Rev Ed).Incorporation8.5.12 Whether an exception clause will have its intended effect depends on a number of factors. The threshold requirement is that the clause must have been incorporated into the contract. There are generally three ways in which such incorporation may occur. Where a party has signed a contract which contains an exception clause, the signatory is bound by the clause, even if he or she had not read or was unaware of the clause. An exception clause may also be incorporated, in the absence of a signed contract, if the party seeking to rely on the clause took reasonably sufficient steps to draw the other party’s attention to the existence of the clause. The determination of this issue is heavily dependent on the facts of the particular case. Finally, exception clauses may be incorporated because there has been a consistent and regular course of dealing between the parties on terms that incorporate the exception clause. Even if no steps were taken to incorporate the clause in a particular contract between such parties, it may have been validly incorporated by the parties’ prior course of dealing.Construction8.5.13 The next consideration is one of construction (or interpretation). This is necessary to determine if the liability, which the relevant party is seeking to exclude or restrict, falls within the proper scope of the clause. Here, the courts adopt the contra proferentum rule of construction, and will construe exception clauses strictly against parties seeking to rely on them. Nevertheless, the Singapore courts appear to construe clauses which seek to limit liability more liberally than those which seek to completely exclude liability.Unfair Contract Terms Act8.5.14 Finally, the limits placed by the Unfair Contracts Terms Act (Cap 396, 1994 Rev Ed) (the ‘UCTA’) on the operation and efficacy of exceptions clauses must be considered. It should be noted that the UCTA generally applies only to terms that affect liability for breach of obligations that arise in the course of a business or from the occupation of business premises. It also gives protection to persons who are dealing as consumers. Under the UCTA, exception clauses are either rendered wholly ineffective, or are ineffective unless shown to satisfy the requirement of reasonableness. Terms that attempt to exclude or restrict a party’s liability for deathor personal injury resulting from that party’s negligence are rendered wholly ineffective by the UCTA, while terms that seek to exclude or restrict liability for negligence resulting in loss or damage other than death or personal injury, and those that attempt to exclude or restrict contractual liability, are subject to therequirement of reasonableness. The reasonableness of the exception clause is evaluated as at the time at which the contract was made. The actual consequencesof the breach are therefore, in theory at least, immaterial.Return to the topSECTION 6 CAPACITY TO CONTRACTMinors8.6.1 Under Singapore common law, a minor is a person under the age of 21. The validity of contracts entered into by minors is governed by the common law, as modified by the Minors’ Contracts Act (Cap 389, 1994 Rev Ed).Contracts with Minors8.6.2 As a general rule, contracts are not enforceable against minors. However, where a minor has been supplied with necessaries (ie goods or services suitable for the maintenance of the station in life of the minor concerned: see also s 3(3), Sale of Goods Act (Cap 393, 1999 Rev Ed)), the minor must pay for them. Contracts of service which are, on the whole, for the minor’s benefit are also valid. The minor is also bound by certain types of contracts (ie contracts concerning land or shares in companies, partnership contracts and marriage settlements), unless the minor repudiates the contract before attaining majority at age 21 or within a reasonable time thereafter.Minors’ Contracts Act8.6.3 Under s 2 of the Minors’ Contracts Act, a guarantee given in respect of a minor’s contract, which may not be enforceable against the minor, is nevertheless enforceable against the guarantor. Section 3(1) of the Minors’ Contracts Act empowers the court to order restitution against the minor if it is just and equitable to do so.Mental Incapacity and Drunkards8.6.4 A contract entered into by a person of unsound mind is valid, unless it can be shown that that person was incapable of understanding what he or she was doing and the other party knew or ought reasonably to have known of the disability. In this case, the contract may be avoided at the option of the mentally unsound person (assisted by a court-sanctioned representative where necessary). The same principle applies in the case of inebriated persons. Under s 3(2) of the Sale of Goods Act, persons incapacitated mentally or by drunkenness are required to pay a reasonable price for necessaries supplied.Corporations8.6.5 Subject to any written law and to any limits contained in its constitution, a company has full capacity to undertake any business, do any act or enter into any transaction (s 23 – Companies Act, Cap 50, 1994 Rev Ed). Where there are restrictions placed on the capacity of a company and the company acts beyond its capacity, s 25 of the Companies Act validates such ultra vires transactions if they would otherwise be valid and binding. Contracts purportedly entered into by a company prior to its incorporation may be ratified and adopted by the company after its formation (s 41 – Companies Act).8.6.6 A limited liability partnership is also a body corporate under Singapore law – see Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2005 (Act No 5 of 2005). It may, in its own name: sue and be sued in its own name; acquire, own, hold and develop property; hold a common seal; and may do and suffer such other acts and things as any body corporate may lawfully do and suffer – see s 5(1). Section 5(2) also extends s 41 of the Companies Act to apply to a limited liability partnership.Return to the topSECTION 7 PRIVITY OF CONTRACTThird party Enforcement of Contractual Rights Generally not Permitted8.7.1 As a general proposition, only persons who are party (ie ‘privy’) to a contract may enforce rights or obligations arising from that contract. This is sometimes referred to as the ‘privity rule.’8.7.2 A third party who is not privy to a contract is generally not allowed to bring any legal action in his or her own name for breach of contract against a contracting party who fails to perform his or her contractual obligations, even if such failure of performance has caused the third party to suffer a loss.When is Someone Party or Privy to a Contract?8.7.3 There is no clear definition as to when a person is/is not privy to a contract. Generally, a party who is an offeror or offeree will be privy to the contract. However, it seems that merely being mentioned in the contract is not enough.8.7.4 It is, nevertheless, possible to have a multilateral contract where there are multiple offerees (one or more of whom accept the offer on behalf of the others) or where there are multiple offerors (one or more of whom make the offer on behalf of the others). In either case, each offeree or offeror is a joint party to the contract and the privity rule will not apply to them.Non-statutory Exceptions to the Privity Rule8.7.5 The privity rule is not absolute. It is subject to many exceptions. Apart from the possibility of a multilateral or multi-party contract (mentioned above), some other exceptions can be found in the law relating to: (a) agency; (b) trusts; or (c) land (in relation to covenants which ‘run’ with the land or lease). For an in depth discussion of these other legal techniques to circumvent the privity rule, please see Chapters 15 and 18.Statutory Exceptions to the Privity Rule8.7.6 There are also statutory exceptions. Most of these are only applicable to specific and narrowly defined cases. Two examples of such statutes include: (a) the Bills of Exchange Act (Cap 23, 1985 Rev Ed) [see Chapter 22 on Banking Law]; and (b) the Bills of Lading Act (Cap 384, 1994 Rev Ed) [see Chapter 25 on Shipping Law]. Of more general application, the Singapore Parliament enacted the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act (Cap 53B, 2002 Rev Ed) in 2001.Contracts (Rights of Third Parties)Act8.7.7 Section 1 provides that the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act has no retrospective effect – it cannot apply to any contract formed before 1 January2002. Section 1 also provides that the Act does not apply to any contracts which were formed on or after 1 January 2002, but before 1 July 2002, unless the contracting parties expressly provided in their contract for it to do so. Contracts formed on or after 1 July 2002 are always subject to the Act.8.7.8 Where the Act applies, it gives a third party a statutory right to enforce a term of a contract against a party who is in breach of his or her obligations under the contract (the ‘promisor’), even though even though the third party is a volunteerwho has not provided any contractual consideration – see s 2(5).8.7.9 This may occur if either: (a) the contract expressly provides that the third party may enforce a term of the contract in his or her own right – s 2(1)(a); or (b) the contract, ‘purports to confer a benefit on the third party’ – s 2(1)(b). However, s 2(1)(b) is qualified: a third party will not be granted the direct statutory right of suit in the absence of an express provision permitting him or her to do so, ‘if, on a proper construction of the contract, it appears that the parties did not intend the term to be enforceable by the third party.’ – s 2(2).8.7.10 This statutory right of enforcement is not just limited to cases where the promisor is under an obligation to act to confer a positive benefit on the thirdparty. ‘Negative’ benefits, such as the benefit of a term excluding or limiting the third party’s legal liabilities to the promisor, may also be enforced –s 2(5).8.7.11 The third party’s statutory right of enforcement against the promisor is qualified in a number of ways. First, the third party’s statutory right of recovery may be qualified by a defence or set-off which the promisor would have been able to assert vis-à-vis the other party to the contract (the ‘promisee’) – s 4. Second, any sum to be recovered by the third party pursuant to the Act may be reduced to take into account sums recovered by the promisee from the promisor in respect of the promisor’s breach – s 6.8.7.12 Once third party rights are created under the Act, certain restrictions are imposed on the ability of the parties to the contract to vary or rescind their contract if this would extinguish or alter the third party’s rights under the Act – s 3.8.7.13 Though wider in its scope than many of the other legal techniques for circumventing privity, the Act is not of universal application. Section 7 of the Act sets out a number of situations where the Act does not apply. Excluded cases include:(a) contracts on a bill of exchange, promissory note or other negotiable instrument;(b) limited liability partnership agreements as defined under the Limited Liability Partnerships Act 2005 (Act 5 of 2005); (c) the statutory contract binding a company and its members under s39 of the Companies Act (Cap 50, 1994 Rev Ed); (d) third party enforcement of any term of an employment contract against an employee; and (e) third party enforcement of any term (apart from any exclusion or limitation of liability for the benefit of the third party) in a contract for carriage of goods by sea, or a contract for the carriage of goods or cargo by rail, road or air, if such contract is subject to certain international transport conventions.Return to the topSECTION 8 DISCHARGE OF CONTRACTDischarge by Performance8.8.1 If all the contractual obligations as defined by the terms of the contract are fully performed, the contract is brought to an end or ‘discharged’ by performance. In theory, such performance must be precise. However, trivial defects in performance may be ignored as being negligible or ‘de minimis.’ In addition, where full performance is only possible with the cooperation of the other party (as is almost invariably the case with obligations of payment or delivery), tender of performancein circumstances where the other party refuses to accept it is generally deemed to be equivalent to full performance so as to discharge the contract.Non- or Defective Performance8.8.2 In the event that a contractual obligation is not performed or is performed defectively in a non-trivial fashion, Singapore law provides for a variety of legal responses and remedies, depending on the nature of the failure of performance.Lawful Excuses for Breach of Contract8.8.3 If the failure of performance is not subject to any lawful excuse, thecontract is said to be ‘breached.’ In this context, ‘lawful excuses’ may take the following forms.Discharge by Agreement8.8.4 First, just as parties are free to agree to bind themselves to a contract, they are free to negotiate with each other to release themselves from the obligations of。

新加坡设立公司章程范本(3篇)

第1篇第一章总则第一条公司名称公司名称为【公司全称】,以下简称“公司”。

第二条公司住所公司住所位于新加坡【具体地址】,如需变更,需依照法定程序办理。

第三条公司经营范围公司经营范围为【具体经营范围】,包括但不限于以下业务:【具体业务列表】第四条公司注册资本公司注册资本为新加坡元【具体金额】,分为【股份数】股,每股面值【每股面值】新加坡元。

第二章股东第五条股东资格公司股东应当符合新加坡法律、法规规定的资格条件。

第六条股东权利与义务1. 股东有权依照章程规定,出席股东大会,参与公司重大决策。

2. 股东有权查阅公司章程、股东名册、公司债券存根、股东大会会议记录、董事会会议决议、监事会会议决议、财务会计报告。

3. 股东有权按照出资比例分取红利。

4. 股东有权按照章程规定转让其股份。

5. 股东应当遵守公司章程,执行股东大会的决议。

6. 股东应当按照出资比例承担公司债务。

第七条股东大会1. 股东大会是公司的最高权力机构。

2. 股东大会的职权包括但不限于:a. 审议和批准公司的经营方针和投资计划;b. 选举和更换董事、监事;c. 审议批准公司的年度财务预算方案、决算方案;d. 审议批准公司的利润分配方案和弥补亏损方案;e. 对公司增加或者减少注册资本作出决议;f. 对公司合并、分立、解散、清算或者变更公司形式作出决议;g. 修改公司章程;h. 公司章程规定的其他职权。

第三章董事会第八条董事会组成公司设董事会,由【董事人数】名董事组成,其中独立董事不少于【独立董事人数】名。

第九条董事会职权1. 董事会对股东大会负责,执行股东大会的决议。

2. 董事会的职权包括但不限于:a. 召集股东大会,并向股东大会报告工作;b. 执行股东大会的决议;c. 制定公司的经营计划和投资方案;d. 制定公司的年度财务预算方案、决算方案;e. 制定公司的利润分配方案和弥补亏损方案;f. 制定公司的基本管理制度;g. 决定公司的经营方针和投资计划;h. 决定公司内部管理机构的设置;i. 决定聘任或者解聘公司经理及其报酬事项;j. 根据经理的提名,决定聘任或者解聘公司副经理、财务负责人及其报酬事项; k. 决定公司的分立、合并、解散或者变更公司形式;l. 决定公司内部管理机构的设置;m. 决定公司重大事项;n. 公司章程规定的其他职权。

新加坡公司的公司治理及分析

新加坡的公司治理政府只派一位财政部官员担任新加坡董事,显示其遵循不介入新加坡商业运作的原则新加坡(私人)有限公司(以下简称“新加坡”)是新加坡财政部的全资国有控股公司。

1974年成立之初,旗下35家公司(以下简称“淡联公司”)的业务仅限于本土,资产总计仅3. 5亿新元。

截至2005年3月底,新加坡投资组合市值达到1030亿新元,年平均股东回报率达到18%。

新加坡的表现可谓出类拔萃,令他国的国有企业不能望其项背。

据2006年3月所公布资料,新加坡目前在80家公司持有5%至100%的股权,约一半资产分布在国外,在金融、电信、工程、运输、物流等领域都有较大的发展。

旗下知名企业包括新加坡航空公司、星展银行、新电信,也在中国建设银行、中国民生银行、中国银行等金融机构持股。

为借鉴新加坡管理国有资产的成功经验,中国国资委曾多次派员到新加坡对其公司治理模式进行全方位考察。

虽然2004年6月国资委的通知规定试点企业董事会的外部董事不少于2人,但对于内、外部董事人数比例并无要求。

到了2005年10月宝钢、神华成立董事会时,外部董事人数均超过半数。

随后加入改革的诚通、国旅、国药、铁通也承诺逐步增加外部董事的人数,使之超过内部董事。

新加坡影响隐约可见。

那么,新加坡到底有什么成功经验值得中国国有企业借鉴呢?我认为,可以从三方面来看:1)新加坡和股东(政府)关系;2)新加坡公司治理;3)新加坡和下属公司关系。

政府不介入新加坡商业决策过程新加坡建国初年,经济基础薄弱,私人资本不足,投资能力有限。

因此,国家担负起引导国民经济发展的重任,进入一般商家不愿涉足的高风险、高投资工业项目领域,如钢铁、造船、石油化学等,创办了一批隶属财政部的国有企业。

这批国有企业于1974年被归入新加坡旗下。

政府授权新加坡和淡联公司按照商业模式灵活运作。

同时政府也刻意自制,不干预新加坡和其他国有企业的管理与商业决策。

新加坡政府对于国有企业一向坚持能者居其位的用人原则,任命有能力的人,确保决策过程透明化,给予其充分的信任,同时也赋予其相应的责任。

新加坡企业法律摘录

新加坡企业法律摘录新加坡企业法律摘录新加坡是一个拥有良好商业环境和完善法律体系的国家,作为一个经济开放型的国家,保护企业的合法权益和营商环境是非常重要的一项工作。

在实践中,新加坡也出台一系列的法规和法律,帮助企业更好的运营和发展。

本文将会对新加坡企业法律进行摘录和分析,以便于读者更好的了解新加坡企业法律体系。

1.《新加坡公司法》新加坡公司法是新加坡的一部关于公司立法的重要法律,它规定了公司的权利和义务,建立了公司的注册、成立、运营和解散的法律框架。

下面是新加坡公司法的主要内容:- 公司的注册:所有拟成立公司必须在新加坡公司注册处进行注册。

注册所需的材料:公司名称、注册地点、公司类型等。

- 公司的资本:新加坡公司法规定了公司的资本的最大和最小限制,同时规定了公司股份的形式和股权转移的方式。

-公司治理:公司的治理主要由董事会、总经理和股东共同组成,可以选择任意数量的董事和股东,但至少要有一名董事和一个股东。

- 公司的税收制度:新加坡的公司税率在2019年为17%,对于个人和公司都非常有吸引力。

- 公司的解散:新加坡公司法规定了公司的解散程序,主要是在公司财务状况差、法务问题和管理不善的情况下发生。

2.《新加坡国际仲裁法》新加坡国际仲裁法主要是针对国际商业仲裁的一部重要法律,目的是保护企业在跨国交易中的权益,有效维护商业互信。

下面是新加坡国际仲裁法的主要内容:- 新加坡国际仲裁法规定了企业可以在新加坡的仲裁中心进行仲裁。

- 在新加坡实行的仲裁判决和裁决书均获得各国官方的认可和保护。

- 新加坡国际仲裁法规定了企业在仲裁期间如何保护自己的权益,包括但不限于保护证据材料、控制费用等。

3.《新加坡版权法》对于以创意为核心的企业,新加坡版权法是非常关键的一部法律,它保护企业的版权和知识产权,保护公司的产权和个人的创作权。

下面是新加坡版权法的主要内容:- 新加坡版权法规定了企业可以享有的版权范围,包括但不限于文学作品、音乐和图片等方面。

新加坡公司法-中文版

新加坡公司法-中文版第十六章公司法第一节导言第二节公司成立及其后果第三节公司治理第四节公司权利的行使第五节股东的救济第六节公司股份第七节公司债据与资产抵押第八节公司困境第九节公司解散第一节导言16.1.1 在新加坡,与公司有关的主要法律是《公司法(Cap50, 1994 Rev Ed)》(以下称“公司法”)。

值得注意的是,一些特殊类型的公司,除了公司法之外,还要受到其他成文法的规制。

如保险公司和银行,还要分别受《保险法(Cap142,1994 Rev Ed)和《银行法(Cap20, 1994 Rev Ed)》的规制。

有限责任合伙组织其实也是公司,受《有限责任合伙组织法(Cap289,1994 Rev Ed)》规制。

在诸如《证券与期货法(Cap289, 1994 Rev Ed)》等其他成文法中,也有一些与公司有关的条款。

16.1.2 应该注意的是,普通法也会对与公司有关的成文法规范进行补充。

第二节公司成立及其后果设立公司的义务16.2.1 根据公司法第17(3)条的规定,拥有20名以上成员的经营组织都必须设立为公司。

但该规定并不适用于那些遵照新加坡其他成文法设立的,由从事特定职业的个人组成的合伙组织(公司法第17(3)条)。

法律职业的从业者,受《法律职业法(Cap161,1994 Rev Ed)》的规制,他们可以设立成员超过20人的合伙组织。

公司的登记16.2.2 一般来说,只要提交相应的文件,缴纳规定的费用,任何人都可以在新加坡通过登记设立公司。

设立公司时,必须提交的最重要的文件是公司章程和组织规章,公司法第19(1)条对此作了强制性要求。

公司章程和组织规章就是公司的宪章。

根据公司法第22(1)条的规定,公司章程必须载明公司名称、公司股本[如果有的话],并表明公司成员承担的是有限责任还是无限责任。

公司组织规章是公司的规章制度,其中也有与公司治理有关的规定。

如果公司章程和组织规章有冲突,前者有优先效力。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Reading material新加坡公司法—公司解散、揭开公司面纱SECTION 9WINDING UP第九节公司解散16.9.1 Despite the best of efforts, an insolvent company may not be able to overcome its difficulties. In such circumstances, the company may be dissolved to enable its assets to be liquidated so that its creditors may be repaid part of what is owing to them. This process by which a company is dissolved is known as winding up or liquidation. A healthy company may also be wound up if its members no longer wish the business to continue. When a company is wound up, its assets or the proceeds thereto will be used to pay off creditors after which the balance, if any, is distributed pro rata amongst shareholders.16.9.1 即使尽了最大努力,破产公司仍有可能无法摆脱困境。

在这种情况下,公司存续便可以终结以使公司债权人能够得到部分清偿。

公司终结的过程被称为公司解散或清算。

如果公司成员不愿再继续经营,运行良好的公司也可以解散。

公司解散时,公司的资产及收益应用于向债权人清偿,如果还有余额,则应按比例分配给公司股东。

Voluntary Winding Up自愿解散16.9.2 There are two forms of liquidation, namely voluntary winding up and compulsory winding up by the court. A voluntary winding up usually occurs where the company resolves to do so by a special resolution – see section 290(1)(b) of the Act. In a voluntary winding up, the directors of the company may make a statement pursuant to section 293(1) of the Act that the directors of the company are of the view that the company will be able to pay its debts in full within a period not exceeding 12 months after the commencement of the winding up. If the directors do so, the wi nding up will proceed as a members’ voluntary winding up. In such circumstances, the shareholders will appoint the liquidator – see section 294(1) of the Act. If the directors do not make such a statement, it will be a creditors’ voluntary winding up, in w hich case the directors must call a meeting of creditors in order to appoint the liquidator – see Re Sin Teck Hong Oil Mills Ltd [1950] MLJ 232.16.9.2 公司解散的方式有两种,即司法解散和自愿解散。

公司自愿解散通常在公司通过特别的解散决议后发生[参见公司法第290(1)(b)条]。

在自愿解散的情况下,公司董事可以根据公司法第239(1)条的规定表示,他们认为公司可以在解散程序开始后不超过12个月的时间内清偿全部债务。

如果公司董事这样做,公司解散即为股东自愿解散。

在这种情况下,公司股东可以任命清算人[参见公司法第294(1)条]。

如果公司董事不作出上述表示,公司解散即为债权人自愿解散,公司董事必须召集债权人会议以任命清算人[参见Re Sin Teck Hong Oil Mills Ltd (1950) MLJ 232 一案]。

16.9.3 A members’ voluntary winding up may be converted into a creditors’ voluntarywinding up if the liquidator appointed by the members forms the opinion that the company will not be able to pay its debts in full within the period stated in the declaration made under section 293(1) of the Act. The liquidator will then have to summon a meeting of creditors and lay before them a statement of the assets and liabilities of the company – see section 295(1) of the Act. The creditors may then, pursuant to section 295(2) of the Act, appoint some other person to be the liquidator for the purpose of the winding up of the company.16.9.3 如果由公司成员任命的清算人认为,公司将无法在公司董事根据公司法第293(1)条表明的时间内清偿全部债务,股东自愿解散可以转变为债权人自愿解散。

清算人则必须召集债权人会议并向债权人发布公司资产与债务声明[参见公司法第295(1)条]。

公司债权人可以根据公司法第295(2)条的规定,另行任命清算人以完成公司解散过程。

Winding Up by the Court司法解散16.9.4 A company may also be compulsorily wound up by an order of court. Under section 253(1) of the Act, a petition to the court to wind up the company may be presented by(i) the company itself;(ii) a creditor;(iii)a contributory, the personal representative of a deceased contributory or the Official Assignee of the estate of a bankrupt contributory;(iv)the liquidator of the company;(v) a judicial manager;(vi) various Ministers on specified grounds.16.9.4 公司也可以基于法院的命令而解散。

根据公司法第253(1)条的规定,下列单位或人员可以向法院提出解散公司的请求:(1)公司本身;(2)公司债权人;(3)捐助人、已死亡之捐助人的个人代表、或者已破产之捐助人的法定资产受让人;(4)公司清算人;(5)司法接管者;(6)具有法定理由的内阁部长。

16.9.5 When such a petition is presented, the court pursuant to section 254(1) of the Act may order the winding up of the company in certain circumstances, the more important of which are the following:(i) the company has by special resolution resolved that it be wound up by the court;(ii) the company does not commence business within a year from its incorporation or suspends its business for a whole year;(iii) the company is unable to pay its debts;(iv) the directors have acted in the affairs of the company in their own interests rather than in the interests of the members as a whole;(v) the court is of opinion that it is just and equitable that the company be wound up;(vi) the company has carried on multi-level marketing or pyramid selling in contravention of any written law that prohibits such activities;(vii) the company is being used for an unlawful purpose or for purposes prejudicial to public peace, welfare or good order in Singapore or against national security or interest.16.9.5 在上述请求提出后,法院可以根据公司法第254(1)条的规定,在某些情形下命令公司解散。