欧洲危重患者肠内营养支持指南2006(英文版)ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition

ESPEN 危重症 译文(DOC)

欧洲肠内肠外营养指南---危重症Clinical Nutrition (2006) 25, 210–223摘要肠内营养即通过肠道喂养,被认为是危重症患者最好的喂养方式,也是对抗因严重疾病引起的高分解代谢的重要办法之一。

这些指南旨在为病情复杂的危重症患者住ICU期间肠内营养的使用提供循证建议,尤其是那些已经发展为严重炎性反应的患者,比如在住ICU期间至少有一个器官功能衰竭的患者。

这些指南是由跨学科专家小组根据官方认可的标准及自1985年开始所有的相关出版物的基础上制定的。

这些指南在共识会议上讨论并被接受。

肠内营养应该用于所有3日内不能接受完全经口饮食的ICU患者。

在最初的24小时内即开始应给予标准的高蛋白饮食配方。

在急性起病和危重病初始阶段,外源性能量供应不应超过20-25kcal/kg/d,相反的,在恢复期则应提供25-30kcal/kg/d。

对于仅通过肠内营养不能达标的患者肠外营养仍然可作为一种补充工具。

对于有严重疾病或脓毒症或APACHEⅡ评分>15分的患者没有免疫调节方式的适应症。

烧伤或外伤的患者应该给予谷氨酰胺。

摘要—危重症所有3日内不能经口饮食的患者应接受肠内营养。

C级目前没有数据显示危重症患者早期使用肠内营养能改善相关结果数据。

尽管如此,专家委员会仍推荐血液动力学稳定、具有胃肠道功能的危重症患者应在24小时内给予适当的喂养。

C级没有数据能推荐肠内营养治疗一定对病程及肠道耐受性有调节作用。

肠外能量供应:●在急性起病和危重病初始阶段,超过20-25kcal/kg/d可能带来更加不良的后果。

C级●在合成代谢的恢复阶段,营养目标为25-30 kcal/kg/d。

C级严重营养不良患者应给予超过25-30 kcal/kg/d,如目标不能达成应给予补充性肠外营养。

C级对于不能耐受胃肠道喂养的患者(如胃潴留明显)可考虑予胃复安或和红霉素。

C级对能使用胃肠道喂养的患者应给予肠内营养。

C级危重症患者经空肠喂养对比经胃喂养在效果上并没有显著的差异。

欧洲肠外肠内营养学会(ESPEN)关于肝病肠内营养的指南(2006)

良(C)。 点评:《美国退伍军人事务》报告了营养不良的

ASH患者有较高的并发症发生率和病死率11-31。为了 确定营养不良.在这些研究中应用了一个含有多个 变量的评分系统.如实际/理想体重、人体测量学参

数、肌酐指数、内脏蛋白、淋巴细胞绝对数、迟发型皮 肤反应等。这个综合评分系统中的一些不可靠的变 量.如内脏蛋白浓度或24 h尿肌酐清除率已被修改 多次.最近发表的文献也报道了有预后意义的变量。 如CD8+T淋巴细胞的绝对值、手握力13]。此外,也明 确了食物摄入不足和高病死率之间的关系121。

4.肠内营养能改善营养状况、肝功能和预后吗? 肠内营养可改善肝硬化患者的营养状况和肝功 能。减少并发症,延长生存期。因此建议应用(A)。 点评:这项建议是建立在5个随机研究共245 例患者的结果基础上15.7.8圆·311(Ib).其中大部分是酒 精性肝硬化。肠内营养可以改善患者肝功能【7tSl、营养

2.何种情况适合给予肠内营养.何种情况禁忌 肠内营养?

当ASH患者不能通过正常的饮食满足能量需 求且无肠梗阻等禁忌证时。应给予肠内营养补充 (C)。

点评:这些建议是基于6个试验研究制定的IM, 共包括465例ASH患者.但其中只有3个研究是随 机的l州(Ib)。《美国退伍军人事务》的研究比较了合 成类固醇与安慰剂之间的疗效差异.以及高能量、 高蛋白质且富含支链氨基酸的经口营养补充与低能 量、低蛋白质的经口营养补充之间的疗效差异【2’31。 1993—1995年发表的一些相关文献包含了《美国退 伍军人事务)#275文献和#119文献的联合及总结 评价.而这些之前是单独发表的【l】。因此。这些相关文 献的结果难以解释说明。然而,这些文献也提示,即 使严重营养不良的ASH患者也可通过经口营养补 充和管饲达到较高的能量和蛋白质摄入。虽然肠内 营养比肠外营养更可取.但没有大样本的随机试验 在ASH患者中进行验证。

ESPEN关于家庭肠内营养的指南(完整版)

ESPEN关于家庭肠内营养的指南(完整版)摘要该指南将告知医生,护士,营养师,药剂师,护理人员和其他家庭肠内营养(HEN)提供者关于HEN的适应症和禁忌症及其实施和监测。

家庭肠外营养不包括在内,但将在单独的ESPEN指南中解决。

该指南还将告知需要HEN的感兴趣的患者。

该指南基于当前的证据和专家意见,包括61项建议,涉及HEN的指示,相关的访问设备及其使用,推荐的产品,终止HEN的监测和标准,以及执行HEN所需的结构要求。

我们根据PICO 格式根据临床问题搜索了荟萃分析,系统评价和单一临床试验。

评估证据并用于制定实施SIGN方法的临床建议。

该指南由ESPEN委托并获得财政支持,指南组成员由ESPEN选出。

介绍自20世纪70年代推出以来,HEN已被确立为可靠和有效的营养干预措施,特别是由于越来越依赖门诊治疗而相关。

通常,HEN在住院期间开始并继续作为长期家庭治疗。

通常,对于HEN和院内肠内营养(EN)的适应症仅存在微小差异。

在HEN中,需要仔细考虑其他标准,例如预后,与健康相关的生活质量(QoL)以及治疗的任何伦理方面。

为了启动HEN,应遵循以下原则:如果没有针对基础医疗条件的有效治疗,则在没有EN 的情况下,期望患者的营养状态显着恶化,影响预后和QoL,这是一个复杂的决定。

肠内营养支持是一种医学治疗,但营养支持的途径,内容和管理决策最好由多学科营养团队做出。

本指南提供了有关HEN使用的基于证据的信息。

有许多常常是复杂的疾病导致对HEN的需求,其描述不是本指南的一部分,但它们包括:由于神经系统疾病吞咽障碍,由于恶性肿瘤导致的障碍,由于癌症,恶病质,慢性阻塞性肺疾病,心脏病,慢性感染,和由于肝脏,胰腺或肠道疾病导致的吸收不良/消化不良。

这些疾病的具体营养需求在最近发表的其他ESPEN指南中有详细描述(参见ESPEN 网站和临床营养学杂志)。

本指南重点关注HEN的方法和临床实践,相关监测以及避免并发症的策略。

危重症营养支持指南2006

危重病人营养支持指导意见(2006)发表者:鲁召欣(访问人次:1472)危重病人营养支持指导意见(2006)中华医学会重症医学分会目录1 危重症与营养支持1.1 营养支持概念的发展1.2 危重病人营养支持目的1.3 危重病人营养支持原则1.4 营养支持途径与选择原则1.5 危重病人能量补充原则2 肠外营养支持(PN)2.1 应用指征;2.2 经肠外补充的主要营养素及其应用原则;2.3 肠外营养支持途径和选择原则。

3 肠内营养支持(EN)3.1 肠内营养应用指征3.2 肠内营养途径选择与营养管放置3.3 肠内营养的管理与肠道喂养安全性评估3.4 常用肠内营养制剂选择4 不同危重病人的代谢特点与营养支持原则4.1 sepsis/MODS病人的营养支持4.2 创伤病人的营养支持4.3 急性肾功能衰竭(ARF)病人的营养支持4.4 肝功能不全及肝移植围术期的营养支持4.5 急性重症胰腺炎(SAP)病人的营养支持4.6 急慢性呼吸衰竭病人的营养支持4.7 心功能不全病人的营养支持5 营养支持的相关问题5.1特殊营养素的药理作用5.1.1 谷氨酰胺在重症病人的应用5.1.2 精氨酸在重症病人的应用5.1.3 鱼油在重症病人的应用5.2 重症病人的血糖控制与强化胰岛素治疗5.3 生长激素在重症病人的应用6 附表—主要营养制剂成分与含量表1 肠内营养制剂主要成分表2 氨基酸注射液表3 脂肪乳剂注射液1.危重症与营养支持1.1 营养支持概念的发展现代重症医学与临床营养支持理论和技术的发展几乎是同步的,都已经历了约半个世纪的历史。

数十年来大量强有力的证据表明,住院病人中存在着普遍的营养不良;而这种营养不良(特别是低蛋白性营养不良)不仅增加了住院病人死亡率,并且显著增加了平均住院时间和医疗费用的支出;而早期适当的营养支持治疗,则可显著地降低上述时间与费用。

近年来,虽然医学科学有了长足的进步,但住院重症病人营养不良的发生比率却未见下降。

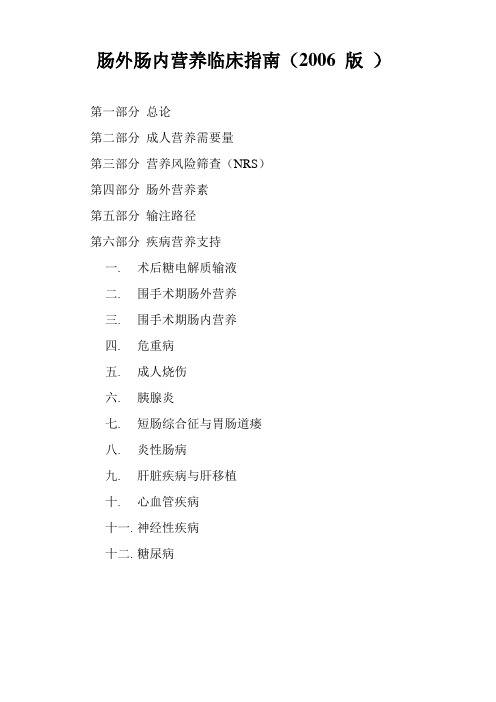

肠外肠内营养临床指南2006版1

肠外肠内营养临床指南(2006 版)第一部分总论第二部分成人营养需要量第三部分营养风险筛查(NRS)第四部分肠外营养素第五部分输注路径第六部分疾病营养支持一.术后糖电解质输液二.围手术期肠外营养三.围手术期肠内营养四.危重病五.成人烧伤六.胰腺炎七.短肠综合征与胃肠道瘘八.炎性肠病九.肝脏疾病与肝移植十.心血管疾病十一.神经性疾病十二.糖尿病Ⅱ.肠外肠内营养临床指南(2006 版)第一部分总论中华医学会肠外肠内营养学分会(Chinese Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, CSPEN)于2004年12月在京成立。

作为一个多学科学术组织,CSPEN的愿景(vision)是倡导循证营养实践,促进我国肠外肠内营养的合理应用,为患者提供安全、有效和具有良好效价比的营养治疗。

编写、制定与推广临床指南是实现上述目标的重要途径。

指南定义为:按照循证医学原则,以当前最佳证据为依据,按照系统和规范方法,在多学科专家、大中规模医院的临床医师和护理人员合作下达成的共识。

本指南的宗旨是为临床医师、护理工作者、营养师和患者在特定临床条件下,制定和/或接受肠外肠内营养治疗方案提供帮助,并为卫生政策的制定者提供决策依据。

2005年,CSPEN组织我国临床营养、儿科、外科、内科等多学科专家成立了第一届《肠外肠内营养指南》编写委员会,于当年制定和公布了第一版《肠外肠内营养学临床“指南”系列一:住院患者肠外营养支持的适应证》,先后在《中国临床营养杂志》、《中华医学杂志》和《中华外科杂志》登载。

这是我国首个按照循证医学原则制定的肠外肠内营养指南,出版后受到国内同行的关注。

2006年版指南制订过程在2005年版的基础上,2006年1月,CSPEN开始组织《肠外和肠内营养临床指南》修订工作。

在广泛听取和收集国内同行意见和建议的基础上,2006年4月,召开了2006版指南第一次“共识工作会议”,讨论重症患者应用营养支持的共识。

欧洲ESPEN关于危重症患者的肠内营养指南

Subject

indication Application

Recommendations

All patients who are not expected to be on a full oral diet within 3 days There are no data support using early EN can improve their Prognosis,but the committee still recommend the early (<24h)appropriate amount of feeding, once the patient have a haemo-dynamically stable and a functioning gastrointestinal tract. Exogenous energy supply: the acute and initial phase:≥25kcal/kg/d less favourable Recovery: ≥25kcal/kg/d severe under-nutrition:the EN energy supply should up to 25kcal/kg/d,if not reached,please add PN If the patient intolerance (such as high gastric residuals) to EN, metoclopramide(胃复安)or Erythromycin(红霉素) should be considered.

欧洲肠外肠内营养学会重症患者肠外肠内 营养指南简介

·诊治指南·欧洲肠外肠内营养学会重症患者肠外肠内营养指南简介何振扬2006年4月,欧洲肠外肠内营养学会(ESPEN)在Clinical Nutrition杂志公布了重症患者肠内营养指南(ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition:Intensive care.Clin Nutr,2006,25:210-223);2009年8月,ESPEN又在该杂志公布了重症患者肠外营养指南(ESPEN Guidelines on Parenteral Nutrition:Intensive care.Clin Nutr,2009, 28:387-400.)。

这两套指南均由欧洲重症医学领域专家基于循证医学以及广泛征求意见和建议后推出,既拥有权威性又保留了随时根据证据变化而更新的特点,反映了当前关于重症患者肠内肠外营养治疗领域的普遍认识,提供了关于一些特殊问题基于循证的信息,如选时、定量、成分和应用途径,同时也表明了哪些方面需要补充研究,在何种情况下(如其他治疗可能已经足够)应该限制或取消营养支持,具有很高的实用性。

我们对这两套指南的部分内容解读如下,供同行参考。

一、指南中建议等级的科学背景基于循证和共识程序,ESPEN的两套指南通过文献的系统评价而产生,主要研究工具是M EDLINE、MBASE、PubM ed和经筛选的Cochrane数据库(人类),主要发表类型包括原著、指南、建议、荟萃分析(meta-analysis)、系统评价(systemic reviews)、随机对照试验和观察研究。

依照SIGN标准(苏格兰学院间指南网络,No39,1999)和AHCPR标准(卫生保健政策与研究机构,No92-0023,1993),将有关建议的证据质量和强度分为A、B、C三个等级:A级为多个随机临床试验或荟萃分析;B级一个随机对照或非随机临床试验;C级为专家共识、病例观察或医疗标准。

欧洲肠外肠内营养学会(ESPEN)发布《癌症患者营养指南》

欧洲肠外肠内营养学会(ESPEN)发布《癌症患者营养指南》 2016年8⽉6⽇,欧洲肠外肠内营养学会(欧洲临床营养代谢学会)官⽅期刊《临床营养》在线发表《癌症患者营养指南》⼿稿(尚未排版),⽬前全⽂共109页,分为6个章节:⽅法、背景、癌症患者总论、特定患者类型相关⼲预、参考⽂献、证据列表。

Clin Nutr. 2016 Aug 6. [Epub ahead of print]ESPEN guidelines on nutrition in cancer patients.Jann Arends, Patrick Bachmann, Vickie Baracos, Nicole Barthelemy, Hartmut Bertz, FedericoBozzetti, Ken Fearon, Elisabeth Hütterer, Elizabeth Isenring, Stein Kaasa, Zeljko Krznaric,Barry Laird, Maria Larsson, Alessandro Laviano, Stefan Mühlebach, Maurizio Muscaritoli, LineOldervoll, Paula Ravasco, Tora Solheim, Florian Strasser, Marian van Bokhorst- De van derSchueren, Jean-Charles Preiser.University of Freiburg, Germany.Centre Régional de Lutte Contre le Cancer Léon Bérard, Lyon, France.University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada.Centre hospitalier universitaire, Liége, Belgium.University of Milan, Milan, Italy.Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.Medical University of Vienna, Austria.Bond University, Gold Coast, Australia.Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.University Hospital Center and School of Medicine, Zagreb, Croatia.Beatson West of Scotland Cancer Centre, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.Karlstad University, Karlstad, Sweden.University of Rome La Sapienza, Roma, Italy.University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland.The Norwegian Heart and Lung Association (LHL), Oslo, Norway.Faculty of Medicine, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal.European Palliative Care Research Centre (PRC), Norwegian University of Science andTechnology and Cancer Clinic, St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital, Trondheim,Norway.Cantonal Hospital St. Gallen, Switzerland.VU University Medical Center (VUmc), Amsterdam, Netherlands.HAN University of Applied Sciences, Nijmegen, Netherlands.Erasme University Hospital, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium.O. METHODSO1. Basic informationTerms and abbreviations1. Goals (Objectives and health questions) of the guideline2. Target Population3. Professional groups involved4. Patient views5. Target users6. Conflict of interest and fundingO2. Methods1. Design2. Searches3. Recommendations4. Consensus5. Review before publication6. Updating guidelineO3. Post-publication impact1. Facilitators and barriers2. Tools for application3. Costs4. Monitoring and auditing / Quality indicatorsA. BACKGROUND1. Metabolism2. Clinical effects3. Aims of nutritionB. GENERAL CONCEPTS FOR ALL CANCER PATIENTS1. Screening2. Energy and substrate requirements3. Nutritional interventions4. Exercise training5. Pharmaconutrients and pharmacological agentsC. INTERVENTIONS RELEVANT TO SPECIFIC PATIENT CATEGORIES1. Surgery2. Radiotherapy3. Curative chemotherapy4. High-dose chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation5. Cancer survivors6. Advanced cancer R. ReferencesE. Evidence Tables。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Clinical Nutrition (2006)25,210–223ESPEN GUIDELINESESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition:Intensive care$K.G.Kreymann a,Ã,M.M.Berger b ,N.E.P .Deutz c ,M.Hiesmayr d ,P .Jolliet e ,G.Kazandjiev f ,G.Nitenberg g ,G.van den Berghe h ,J.Wernerman i ,DGEM:$$C.Ebner,W.Hartl,C.Heymann,C.SpiesaDepartment of Intensive Care Medicine,University Hospital Eppendorf,Hamburg,Germany b Soins Intensifs Chirurgicaux et Centre des Bru ˆles,Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Vaudois (CHUV)-BH 08.660,Lausanne,Switzerland cDepartment of Surgery,Maastricht University,Maastricht,The Netherlands dDepartment of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care,Medical University of Vienna,Vienna,Austria eDepartment of Intensive Care,University Hospital Geneva,Geneva,Switzerland fDepartment of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care,Military Medical University,Sofia,Bulgaria gDepartment of Anaesthesia,Intensive Care and Infectious Diseases,Institut Gustave-Roussy,Villejuif,France hDepartment of Intensive Care Medicine,University Hospital Gasthuisberg,Leuven,Belgium iDepartment of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine,Karolinska University Hospital,Huddinge,Stockholm,SwedenReceived 20January 2006;accepted 20January 2006KEYWORDSGuideline;Clinical practice;Evidence-based;Enteral nutrition;T ube feeding;Oral nutritional sup-plements;Parenteral nutrition;Immune-modulating nutrition;Summary Enteral nutrition (EN)via tube feeding is,today,the preferred way of feeding the critically ill patient and an important means of counteracting for the catabolic state induced by severe diseases.These guidelines are intended to give evidence-based recommendations for the use of EN in patients who have a complicated course during their ICU stay,focusing particularly on those who develop a severe inflammatory response,i.e.patients who have failure of at least one organ during their ICU stay.These guidelines were developed by an interdisciplinary expert group in accordance with officially accepted standards and are based on all relevant publica-tions since 1985.They were discussed and accepted in a consensus conference.EN should be given to all ICU patients who are not expected to be taking a full oral diet within three days.It should have begun during the first 24h using a standard/journals/clnu0261-5614/$-see front matter &2006European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2006.01.021$For further information on methodology see Schu ¨tz et al.69For further information on definition of terms see Lochs et al.70ÃCorresponding author .Tel.:+4940428037010;fax:+4940428037020.E-mail address:kreymann@uke.uni-hamburg.de (K.G.Kreymann).$$The authors of the DGEM (German Society for Nutritional Medicine)guidelines on enteral nutrition in intensive care are acknowledged for their contribution to this article.Intensive care; Undernutrition; Malnutrition; Catabolism; Prognosis; Outcome high-protein formula.During the acute and initial phases of critical illness an exogenous energy supply in excess of20–25kcal/kg BW/day should be avoided, whereas,during recovery,the aim should be to provide values of25–30total kcal/ kg BW/day.Supplementary parenteral nutrition remains a reserve tool and should be given only to those patients who do not reach their target nutrient intake on EN alone.There is no general indication for immune-modulating formulae in patients with severe illness or sepsis and an APACHE II Score415.Glutamine should be supplemented in patients suffering from burns or trauma.The full version of this article is available at .&2006European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism.All rights reserved.Summary of statements:Intensive careSubject Recommendations Grade69Number Indications All patients who are not expected to be on a full oraldiet within3days should receive enteral nutrition(EN).C1Application There are no data showing improvement in relevantoutcome parameters using early EN in critically illpatients.2Nevertheless,the expert committee recommendsthat haemodynamically stable critically ill patientswho have a functioning gastrointestinal tract shouldbe fed early(o24h)using an appropriate amount offeed.C2No general amount can be recommended as ENtherapy has to be adjusted to the progression/course of the disease and to gut tolerance.3Exogenous energy supply:during the acute and initial phase of critical illness:in excess of20–25kcal/kg BW/day may be associated with a less favourable outcome.C3during the anabolic recovery phase,the aimshould be to provide25–30kcal/kg BW/day.C3Patients with a severe undernutrition should receiveEN up25–30total kcal/kg BW/day.If these targetvalues are not reached supplementary parenteralnutrition should be given.C9Consider i.v.administration of metoclopramide orerythromycin in patients with intolerance to enteralfeeding(e.g.with high gastric residuals).C6Route Use EN in patients who can be fed via the enteralroute.C7There is no significant difference in the efficacy ofjejunal versus gastric feeding in critically illpatients.C4Avoid additional parenteral nutrition in patients who tolerate EN and can be fed approximately to the target values.A8ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition211Use supplemental parenteral nutrition in patientswho cannot be fed sufficiently via the enteral route.C8 Consider careful parenteral nutrition in patientsintolerant to EN at a level equal to but notexceeding the nutritional needs of the patient.C8Type of formula Whole protein formulae are appropriate in mostpatients because no clinical advantage of peptide-based formulae could be shown.C5Immune-modulating formulae(formulae enrichedwith arginine,nucleotides and x-3fatty acids)aresuperior to standard enteral formulae:in elective upper GI surgical patients(see guidelines surgery).A10.1in patients with a mild sepsis(APACHE II o15).B10.2in patients with severe sepsis,however, immune-modulating formulae may be harmful and are therefore not recommended.B10.2in patients with trauma(see guidelines surgery)A10.3in patients with ARDS(formulae containing o-3fatty acids and antioxidants).B10.5No recommendation for immune-modulatingformulae can be given for burned patients due toinsufficient data.10.4In burned patients trace elements(Cu,Se and Zn)should be supplemented in a higher than standarddose.A10.4ICU patients with very severe illness who do nottolerate more than700ml enteral formulae per dayshould not receive an immune-modulating formulaenriched with arginine,nucleotides and o-3fattyacids.B10.6Glutamine should be added to standard enteralformula inburned patients A12.1trauma patients A12.1There are not sufficient data to support glutaminesupplementation in surgical or heterogenouscritically ill patients.12.2 Grade:Grade of recommendation;Number:refers to statement number within the text.Preliminary remarksPatientsA major methodological problem in this chapter are the terms‘‘ICU patients’’and‘‘critically ill’’as they do not refer to homogenous populations.Patients included in original trials as well as those consid-ered in review articles vary widely in terms of diagnosis,severity of disease,metabolic derange-ments,therapeutic procedures,and gastrointest-inal function.Overlap with other chapters concerning patients in need of intensive care(surgery, trauma and transplant patients)is therefore in-evitable.K.G.Kreymann et al.212In order to minimise overlap,only trials that met the following criteria were evaluated:The severity of disease could be deduced from the available data.The patients included in the study could not be explicitly assigned to categories discussed in other chapters(e.g.patients undergoing elec-tive surgery).The patients were not routinely managed in ICUs for a short term.The recommendations are thus focused on patients who develop an intense inflammatory response with failure of at least one organ or patients with an acute illness necessitating support of their organ function during their ICU stay.The results were then classified into the follow-ing categories:surgical,medical,trauma,trans-plant,burns and sepsis.TerminologyAs oral intake is almost always impossible in these patients,in this chapter the term‘‘EN’’is confined to tube feeding exclusively without regard to any kind of oral nutritional supplement.Outcome measuresICU mortality,28-day mortality and hospital mortal-ity as well as length of stay in ICU or hospital were listed as primary outcome measures.Data on long-term survival would have been useful but were, unfortunately,not given in any of the studies.As post-ICU mortality is high,6-month mortality was also considered a relevant outcome measure.The rate of septic complications was listed as a secondary outcome measure.Particular emphasis was placed on identifying nutrition-related compli-cations,e.g.infections,when such information was available.Indications for and implementation of enteral nutrition(EN)1.When is EN indicated in ICU patients?All patients who are not expected to be on a full oral diet within3days should receive EN(C). Comment:Studies investigating the maximum time ICU patients can survive without nutritional support would be considered unethical and are therefore not available.Owing to increased substrate metabolism,under-nutrition is more likely to develop in critical illness than in uncomplicated starvation or in less acute illness.A Scandinavian study1showed that patients on glucose treatment only(250–300g)over a period of14days,had a10times higher mortality rate than patients on continuous total parenteral nutri-tion.These data imply that,with an inadequate oral intake,undernutrition is likely to develop within 8–12days following surgery.However,most of the trials studying early EN in various patient groups (see below)have compared a regimen of early EN with standard care and oral intake or with late EN after4–6days.As most of these studies have shown a positive effect of early EN,we have come to the conclusion that all patients who are not expected be on an full oral diet within three days should receive nutritional support.2.Is early EN(o24–48h after admission to ICU)superior to delayed EN in the critically ill?There are no data showing improvement in relevant outcome parameters using early EN in critically ill patients.The expert committee, however favours the view that critically ill patients,who are haemodynamically stable and have a functioning gastrointestinal tract, should be fed early(o24h),if possible,using an appropriate amount of feed(C).Comment:Only one study evaluating early EN was performed specifically in critically ill patients.2 Most studies were performed after trauma or abdominal surgery and these were summarised in 2meta-analyses3,4and2systematic reviews.5,6 Meta-analyses and reviewsA meta-analysis of15randomised controlled trials4 evaluated the effects of early EN in adult patients after surgery,trauma,head injury,burns or suffer-ing from acute medical conditions.Early EN was associated with a significant reduction in infectious complications and length of stay.Owing to the heterogeneity between the studies however,the results of this meta-analysis have to be interpreted with caution.Zaloga,6in a systematic review of19studies of early EN,found a positive effect of early EN on survival rate in one study.In15trials a positive impact on length of treatment,the rate of septic and other complications,and on other secondary parameters was found.They concluded that there was level1evidence to support the use of early EN.ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition213The results of the Cochrane Library review by Heyland5however,differed in its conclusions. Heyland concluded that early EN should be recom-mended in the critically ill(B)whereas it should only be considered in other ICU patients(C).The problem with this review is that it included6trials of which only one was performed in truly critically ill patients.Zaloga6included this trial in his review but not the other5.Individual studiesAfter screening all the studies we have included only6studies in our evaluation,since the other trials on early EN did not meet our initial criteria.In contrast to the meta-analysis by Marik4or the review of Zaloga6we were only able to reach recommendation level C for early EN.This is due to some of the difficulties in interpreting some of the published data concerning critically ill patients. Furthermore,most of the trials had substantial methodological shortcomings which weakened their keyfindings.The concept of early enteral versus inadequate oral or versus oral and parenteral nutrition has been best investigated in polytrauma patients.The first published trial on this topic by Moore and Jones7in1986randomised75patients with abdominal trauma.The control group received approximately100g carbohydrates for5days after surgery.If the patients were then not able to consume an oral diet,PN was initiated.In the study group early EN(12–24h after trauma)was deliv-ered via a needle catheter jejunostomy placed during emergency laparotomy.On the fourth day, the patients in the study group had a caloric intake 1.5times higher than their energy expenditure, whereas the control group only received1/3of their energy expenditure.The control group devel-oped infectious complications(intra-abdominal abscesses,pneumonia)more frequently than the study group over an unspecified period.However, the frequency of all infections as well as mortality were comparable between the groups.No data were available on length of stay.A critical issue is that total parenteral nutrition had to be provided in30%of the control group due to insufficient oral intake.It is possible that the better outcome in the jejunostomy group had more to do with the complications associated with total parenteral nutrition in the control group than the advantages of EN in the study group.Graham and coworkers8randomised32polytrau-ma patients with head injury to receive either early jejunal feeding or delayed gastric feeding.With the early jejunal feedings,daily caloric intake im-proved(2102versus1100kcal/day)and the inci-dence of bacterial infections and length of stay in ICU was significantly reduced.There were no data on mortality.Chiarelli et al.9randomised20patients with burns ranging between25%and75%total body surface area.EN was initiated within4h after injury in the study group and57h after injury in the control group who had received no nutrition up to that time.Early EN did not reduce length of stay but was associated with a significantly reduced incidence of positive blood cultures as well as with a normal-isation of endocrine status.Precise data on morbidity as well as on the total caloric intake during the immediate days after injury are lacking. Eyer et al.10randomised52patients with blunt trauma to receive either early or late feeding.The early EN group received nutritional therapy within 24h,whereas the control group only received nutritional therapy after3days.In total,14of the52patients had to be excluded from the study, because they either died within48h or because the target protein intake of1.5g/kg BW/day was not achieved.The authors concluded that early EN had no positive effect on ICU length of stay,ventilator days,organ system failure or mortality.The group receiving early EN even suffered a greater number of total infections(pneumonia,infections of the urinary tract).These negative results were met with massive criticism by the advocates of early EN,11,12who suggested that nutritional therapy had been in-itiated too late in the study group(424h)and had not been administered via a jejunostomy, which would have allowed an earlier initiation of feeding.The study was also criticised because significantly more patients with severe thoracic trauma and significantly reduced lung function (lower Horowitz quotient)had been entered in the study group and this was suggested as a possible cause for the higher infection rate(esp.pneumo-nia)in this group.Hasse et al.13investigated the impact of early EN on the outcome of50liver transplant patients.The patients were randomised to receive either EN within12h after transplantation or maintenance i.v.fluid until oral intake was initiated on day2. Caloric intake was3–4times higher in the group receiving early EN during3–4days after transplan-tation and80–110%of the actual energy expendi-ture was therefore met early.Despite the higher caloric intake in the early EN group,no significant effect was found on length of time on ventilatory support,length of stay in ICU and hospital,number of readmissions,infections, or rejection during thefirst21post-transplantK.G.Kreymann et al.214days.However,viral infections occurred less frequently in the early EN group.Singh et al.14compared the effect of early postoperative EN with spontaneous oral intake in patients with nontraumatic intestinal perforation and peritonitis.Early EN was delivered,via an intra-operatively placed jejunostomy,within12h of surgery.In total,42patients were included(21in the study group,22in the control group).On day1 the EN group received a higher intake(800versus 400kcal)and by day4this had increased further to 42000kcal,while the control group still had a very low oral intake.With the early EN,a significant decrease of infectious complication rates was observed,although mortality did not differ be-tween the groups.None of the above trials met the current standards for a controlled trial(prospective, randomised and double blind)with power calcula-tions and error estimation for the anticipated effects.Because of the small number of patients studied, the data on mortality are difficult to interpret and a classification of observed effects according to the underlying diseases does not make sense.In contrast to animal models,it remains unclear whether early EN—even in small amounts,might prevent alterations of intestinal permeability in man.A newer study,2published after the two meta-analyses cited above,evaluated early versus late (day1versus day5)EN in mechanically ventilated patients.Patients in the early feeding group had statistically greater incidences of ventilator-associated pneumonia(49.3%versus30.7%; P¼0:020)as well as a longer intensive care unit (13.6714.2days versus9.877.4days;P¼0:043) and hospital lengths of stay(22.9719.7days versus 16.7712.5days;P¼0:023).It should be noted, that patients randomised to late EN also received 20%of their estimated daily nutritional require-ments during thefirst4days.This study therefore, actually compared early aggressive versus less aggressive feeding rather than early versus late feeding.Unfortunately,the study was also not randomised,since group assignment was based on the day of enrolment(odd-versus even-numbered days).In summary,the evidence in favour of early EN in critical illness is not as strong as suggested by Zaloga6We conclude however—based more on current data and our own experience than on conclusive scientific data—that early EN in an appropriate amount(see statement3)and with the aim of avoiding gut failure can be recom-mended at level C.3.How much EN should critically ill patients receive?No general amount can be recommended as EN therapy has to be adjusted according to the progression/course of the disease and to gut tolerance.During the acute and initial phase of critical illness an exogenous energy supply in excess of20–25kcal/kg BW/day may be asso-ciated with a less favourable outcome(C). During recovery(anabolicflow phase),the aim should be to provide25–30total kcal/kg BW/day(C).Comment:There is general agreement that hyper-alimentation(provision of more energy than actu-ally expended)should be avoided in the critically ill,although this has not yet been confirmed by randomised controlled trials.Even generally re-ported target values of25–30total kcal/kg BW/day for men and20–25total kcal/kg BW/day for women may be too much during thefirst72–96h of critical illness.A prospective observational cohort study15on patients with an ICU length of stay of at least96h showed that patients who received only33–66%of the target energy intake had a significantly greater likelihood of being discharged from hospital alive (odds ratio 1.22,95%confidence interval 1.15–1.29)than those who received66–100%of the target intake(odds ratio0.71,95%confidence interval0.66–0.75).The results are difficult to interpret as the severity of illness,the incidence of undernutrition,and the length of stay in relation to the level of caloric feeding were not reported. Although this was not a randomised clinical trial, the results raise the same concern as those reported by Ibrahim et al.2and support the idea that,during the acute phase of critical illness,the provision of higher amounts of nutrients is asso-ciated with a less advantageous outcome.However, this is an area which is in particular need of prospective studies,since hypocaloric feeding in the initial phase of ICU-stay may or may not be a disadvantage for the patient.In particular,caution is warranted in patients with prior undernutrition.A recent trial has put emphasis on the relation between growing energy deficit and the number of complications16There seems to be a cut off of cumulated energy deficit(10,000kcal)beyond which the complications increase(infections, wound healing).During stabilisation and recovery(anabolicflow phase)larger amounts of energy(25–30total kcal/kg)are required to support the anabolic reconstitution.ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition2154.Which route is preferable for EN?There is no significant difference in the efficacy of jejunal versus gastric feeding in critically ill patients(C).Comment:When jejunal feeding can be easily carried out(post abdominal trauma or elective abdominal surgery),it is likely to be the best option.Other critically ill patients may be fed via a jejunal tube only after they have shown intoler-ance to gastric feeding.In these patients jejunal feeding should be initiated under strict clinical observation.Jejunal feeding was compared with gastric feeding in11randomised trials.17–26Five of these studies reported the amount of nutrition received by each method.17,18,23–25It was found to be equal in three studies,better with gastric in one,and better with jejunal feeding in another.Although the rate of development of pneumonia was less with jejunal feeding in three stu-dies,21,23,26there was no difference between the two methods of feeding with respect to mortality or length of stay.We conclude that these results do not justify a general recommendation for jejunal feeding in critically ill patients(A).Otherwise,as most of the studies reporting positive effects of early postoperative enteral feeding were per-formed with jejunal feeding via a needle catheter jejunostomy,we recommend that,when jejunal feeding can be carried out easily,it should be given(C).In other patients it should be per-formed only after they prove intolerant to gastric feeding(C).5.Is a peptide-based formula preferable to a whole protein formula?No clinical advantage could be shown for such a formula in critically ill patients(Ia).Therefore, whole protein formulae are appropriate in most patients(C).Comment:The observation that exocrine pan-creatic function is reduced in sepsis27gave rise to concerns about the digestion and ab-sorption of whole protein formulae in critical illness.Peptide-based(low molecular)formulae have therefore been evaluated in four randomised trials27–30with contradictory results.While two of them28,30described a reduction in the incidence and/or frequency of diarrhoea using a peptide-based formula,another study29found a higher frequency of diarrhoea with such a formula and the fourth one27found no difference.As no clear cut advantage of peptide-based formulae has been demonstrated in these studies and taking into account the higher price,we concluded that the use of peptide-based formulas should not be recommended(C).6.When should motility agents be used in critically ill patients?IV administration of metoclopramide or erythro-mycin should be considered in patients with intolerance to enteral feeding e.g.with high gastric residuals(C).Comment:Eighteen randomised studies evaluating the use of motility agents in critically ill patients that were published before2002have been summarised in a meta-analysis by Booth et al.31 Six of these studies evaluated the use of motility agents for the placement of jejunal feeding tubes, 11examined the gastrointestinal function and one study tested the use of metoclopramide for the prevention of pneumonia.Eight of ten studies that evaluated the effect of motility agents on measures of gastrointestinal transit demonstrated positive effects.However,the study reported by Yavagal et al.32found that the incidence of pneumonia was not influenced by metoclopramide. On the contrary,there was even a non-significant trend towards a higher incidence of pneumonia (16.8%versus13.7%)in patients that received the drug.The results of this meta-analysis are further supported by three studies published subse-quently.33–35One study34found no advantage from the use of erythromycin in terms of the time taken to achieve full EN in children after primary repair of uncomplicated gastrochisis.The second study35 reported no positive effect of metoclopramide on gastric emptying in patients with severe head injury.The third33found a significant difference in the amount of feed tolerated at48h(58%versus 44%,P¼0:001)using erythromycin versus placebo. There was no effect on the amount of feed tolerated throughout the entire duration of the study.We concluded that the results of these studies do not support the routine use of motility agents in critically ill patients(A).Metoclopramide(doses, regimen)or erythromycin(idem)can be used for the symptomatic treatment of patients who do not tolerate sufficient enteral feed(C).Cisapride is no longer approved and should not be used in these patients.K.G.Kreymann et al.216EN versus PN7.Should EN be preferred to PN?Patients who can be fed via the enteral route should receive EN(C).Comment(Meta-analyses and reviews):One meta-analysis36and one systematic review37investigated this issue.The meta-analysis36of27trials including 1829patients evaluated20trials comparing EN by tube with PN and7trials comparing oral nutrition with PN.Most of these trials,however,were not performed on critically ill‘‘ICU’’patients but on elective surgical patients and whether the results can be extrapolated to the critically ill remains uncertain.The aggregated results showed no significant difference in mortality rate with tube feeding[RR0.96;95%CI0.55–1.65]nor with oral feeding[RR1.14;95%CI0.69–1.88]versus parenteral nutrition. Clinically,the most relevantfinding was a signifi-cantly lower cumulative risk of infections with either enteral or oral nutrition than with parenteral nutrition(EN versus parenteral nutrition RR0.66; 95%CI0.56–0.79,oral nutrition versus parenteral nutrition RR0.77;95%CI0.65–0.91).ICU or hospital length of stay was not evaluated.In a systematic review,Lipman37considered decreased costs to be the only relevant difference between EN and parenteral nutrition.He concluded that there was no reduction in complications with tube feeding,no reduced rate of infections,no functional or morphological improvement of the intestinal tract,no reduced rate of bacterial translocation,no benefit on relevant outcome measures such as survival,length of stay or rate of infections;nor did he consider EN to be more ‘‘physiological’’.Only in patients with abdominal trauma,was EN found to decrease septic morbidity (see below).Individual studiesWe found only7studies which met our criteria for ICU patients.11,38–43All of these trials compared EN with PN.No significant difference in mortality was found between those receiving EN or PN.There was also no significant difference between length of stay in ICU or hospital between the two regimens.Only2 studies11,42showed a significant reduction in the rate of septic complications.The study by Kudsk et al.11comparing EN versus PN in89patients after blunt or penetrating trauma,showed that there were significantly fewer infections with EN in patients with an injury severity score420and abdominal trauma index424(15%versus67%). The study by Moore et al.42assessed75patients with abdominal trauma.Infections developed in 17%of the enterally and37%of the parenterally fed patientsðP¼0:03Þ.The clinical relevance of these results is lessened by the fact that there was no improvement in length of stay or mortality in the studies that reported a significant decrease in septic complica-tions.In addition,these studies were undertaken when blood sugar control was not on the agenda, and it is well known that PN is more commonly associated with hyperglycemia than EN.In summary we conclude that the available studies do not show a definite advantage of EN over PN except for cost reduction.However,we support the expert opinion that,although over aggressive EN may cause harm,patients who can be fed enterally should receive it,but that care must be taken to avoid overfeeding.8.Under what conditions should PN be added to EN?In patients who tolerate EN and can be fed approximately to the target values no addi-tional PN should be given(A).In patients who cannot be fed sufficient enter-ally the deficit should be supplemented parent-erally(C).In patients intolerant to EN,careful parenteral nutrition may be proposed at a level equal to but not exceeding the nutritional needs of the patient(C).Overfeeding should be avoided.Comment:Five studies comparing EN alone with EN plus PN were analysed in a meta-analysis published by Dhaliwal et al.44The analysis revealed that the addition of PN to EN had no significant effect on mortality.Also,there was no difference between the two groups in the rate of infectious complica-tions,length of hospital stay,or days on the ventilator.The majority of the trials were carried out before the era of glucose control which started after the Louvain trial in2001.68The ancient parenteral trials are likely to have been associated with major hyperglycemia—their poor outcomes are therefore not to be considered as being due to PN alone.In most of the studies,patients who were on EN alone already met the lower target values of caloric intake cited above.As the provision of more energy can be associated with a worse outcome,adding PN is unlikely to improve outcome under these circumstances.For this reason additional PN shouldESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition217。