脊柱外科临床指南

强直性脊柱炎临床诊疗指南(简洁国内版)

强直性脊柱炎临床诊疗指南(简洁国内版)强直性脊柱炎(Ankylosing Spondylitis,AS)是⼀种慢性进⾏性疾病,主要侵犯骶髂关节,脊柱⾻突,脊柱旁软组织及外周关节,并可伴发关节外表现。

严重者可发⽣脊柱畸形和关节强直。

AS是脊柱关节病的原型或称原发性AS;其它脊柱关节病并发的骶髂关节炎为继发性AS。

通常所指及本指南所指均为前者。

AS 的患病率以往认为本病男性多见,男⼥之⽐为10.6:1;现报告男⼥之⽐为为2:1到3:1,只不过⼥性发病较缓慢及病情较轻。

发病年龄通常在13-31岁,30岁以后及8岁以前发病者少见。

AS的病因未明。

基因和环境因素共同在发病中发挥作⽤。

HLA-B27(下称B27)与AS的发病密切相关,并有明显家族发病倾向,我国阳性率为2%-7%,AS患者B27的阳性率达91%。

普通⼈群AS的患病率约为0.1%,在AS患者的家系中为4%,在B27阳性的AS患者中,其⼀级亲属中AS患病率⾼达11%-25%。

⼤约80%的B27阳性者并不发⽣AS,以及⼤约10%的AS患者为B27阴性。

AS的发⽣还有如肠道细菌及肠道炎症等其他因素参与。

AS的病理性标志和早期表现之⼀为骶髂关节炎。

脊柱受累到晚期的典型表现为⽵节状脊柱。

本病发病隐袭。

最常见的症状是腰背痛,⾮典型者可以周围关节炎开始。

患者逐渐出现腰背部或骶髂部疼痛和/或发僵,半夜痛醒,翻⾝困难,晨起或久坐后起⽴时腰部发僵明显,但活动后减轻。

有些患者感臀部钝痛或骶髂部剧痛,偶向周边放射。

咳嗽、打喷嚏、突然扭动腰部疼痛可加重。

疾病早期疼痛多在⼀侧呈间断性,数⽉后疼痛多为双侧呈持续性。

随病变由腰椎向胸颈部脊椎发展,则出现相应部位疼痛、活动受限或脊柱畸形。

24%-75%的AS患者在病初或病程中出现外周关节病变,以膝、髋、踝和肩关节居多,肘及⼿和⾜⼩关节偶有受累。

⾮对称性、少数关节或单关节,及下肢⼤关节的关节炎为本病外周关节炎的特征。

我国患者除髋关节外,膝和其他关节的关节炎或关节痛多为暂时性,极少或⼏乎不引起关节破坏和残疾。

诊疗指南 脊椎骨折

诊疗指南脊椎骨折

诊疗指南:脊椎骨折

概述

脊椎骨折是一个常见的骨折类型,常见于骨质疏松、高峰时段

和外伤等因素影响下。

本指南旨在提供脊椎骨折的诊断和治疗指导,以便提高患者的治疗效果和预后。

诊断

1. 病史询问:详细询问患者受伤情况和症状表现,包括疼痛部位、活动受限等。

2. 体格检查:进行脊柱检查,包括感觉和运动功能评估。

3. 影像学检查:常规使用X射线、CT或MRI进行检查,以确

定骨折类型和程度。

分类

脊椎骨折按照骨折位置和类型进行分类,其中常见的骨折类型

包括:

1. 横行骨折:横向断裂脊椎骨的一种骨折。

2. 纵行骨折:纵向断裂脊椎骨的一种骨折。

3. 压缩性骨折:脊椎骨在一个方向上受到压缩而发生的骨折。

治疗

1. 保守治疗:适用于稳定骨折,包括卧床休息、疼痛控制、牵

引等。

2. 手术治疗:适用于不稳定骨折,包括内固定和植骨等手术方法。

预后

1. 随访:对患者进行定期随访,评估治疗效果和功能恢复情况。

2. 康复训练:提供康复训练指导,帮助患者恢复脊柱功能和日

常活动能力。

以上是脊椎骨折的诊疗指南,旨在为医生提供明确的诊断和治

疗策略,以便改善患者的治疗效果和预后。

脊柱外科临床路径

根据《临床诊疗指南-骨科学分册》(年制和7年制教材临床医学专用,人民卫生出版社)

1。病史:单侧或双侧神经根损伤或马尾神经损伤的症状。

2。体征:单侧或双侧神经根损伤或马尾神经损伤的阳性体征。

3.影像学检查:有椎间盘突出或脱出压迫神经根或马尾神经的表现。

(2)术前可能需要肌电图、诱发电位检查;

(3)有相关疾病者必要时请相应科室会诊。

(七)选择用药。

抗菌药物:按照《抗菌药物临床应用指导原则》(卫医发〔2004〕285号)执行。

(八)手术日为入院第4-6天。

1。麻醉方式:局麻+强化或全麻。

2.手术方式:颈前路减压植骨固定、颈后路减压植骨固定、颈前后联合入路减压植骨固定术。

3.有上胸椎同时累及者,可能同期手术。

4。内植物的选择:由于病情不同,使用不同的内植物,可能导致住院费用存在差异。

二、颈椎病(脊髓型)临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为颈椎病(ICD-10:M47。1↑G99。2*)

行颈前路减压植骨固定、颈后路减压植骨固定、颈前后联合入路减压植骨固定术(ICD—9-CM-3:81。02—81.03)

3.手术内植物:前路钛板、Cage或后路螺钉、固定板(棒)、钛缆、钛网、人工椎间盘、各种植骨材料。

4。输血:视术中情况而定。

(九)术后住院恢复5—11天.

1.必须复查的检查项目:颈椎正侧位片.

2.术后处理:

(1)抗菌药物:按照《抗菌药物临床应用指导原则》(卫医发〔2004〕285号)执行;

(2)术后镇痛:参照《骨科常见疼痛的处理专家建议》;

□注意神经功能变化

□注意伤口情况

□上级医师查房,进行手术及伤口评估,确定有无手术并发症和切口愈合不良情况,明确是否出院

脊柱骨折诊疗常规指南骨科及治疗方案

脊柱骨折诊疗常规指南骨科及治疗方案【概述】脊柱骨折十分常见,约占全身骨折的5%〜6%,胸腰段脊柱骨折多见。

脊柱骨折可并发脊髓或马尾神经损伤,特别是颈椎骨折一脱位合并有脊髓损伤者,据报告可达70%,能严重致残甚至丧失生命。

1、解剖概要每块脊柱骨分椎体与附件两部分。

可将整个脊柱分为前、中、后三柱。

前柱包含了椎体的前2/3、纤维环的前半部分和后纵韧带;中柱包含了椎体的后1/3、纤维环的后半部分和后纵韧带;而后柱包含了后关节囊、黄韧带、脊椎的附件、关节突和脊上以及脊间韧带。

中柱和后柱包裹了脊髓和马尾神经,该区的损伤能够累及神经系统,特别是中柱的损伤,碎骨片和髓核组织能够突入椎管的前半部,损伤脊髓,所以对每个脊柱骨折病例都必须了解有无中柱损伤。

胸腰段脊柱(胸10〜腰2)处于两个生理弧度的交汇处,活动度达,是应力集中之处,所以该处骨折十分常见。

2、病因和分类暴力是引起胸腰椎体骨折的主要原因。

暴力的方向能够通过X、Y、Z轴。

脊柱右六中运动:在Y轴上有压缩、牵拉和旋转;在X轴上有屈、伸和侧方移动;在Z轴上则有侧屈和前后方向移动。

有三种力量能够作用于中轴:轴向的压缩、轴向的牵拉和在横面上的移动。

三种病因不会同时存在,例如轴向的压痛和轴向的牵拉就不可能同时存在。

所以胸腰椎骨折和颈椎骨折分别能够有六中类型损伤。

【诊断标准】1、诊断依据(1)外伤史,伤后右局部疼痛,站立即翻身困难。

(2)胸腰段后突畸形。

(3)X线影像学检查有助于明确诊断,明确损伤部位,类型和移位情况。

2.分类诊断(1)胸腰椎骨折的分类1)单纯性楔形压缩性骨折:这是脊柱前柱损伤的结果。

该型骨折部损伤脊柱,脊柱仍可保持其稳定性。

此类骨折通常为高空坠落伤,足、臀部着地,身体猛烈屈曲,产生了椎体前半部压痛。

2)稳定性爆破型骨折:这是脊柱前柱和中柱损伤的结果。

暴力来自Y轴的轴向压缩。

通常亦为高空坠落伤,足臀部着地,脊柱保持正直,胸腰段脊柱的椎体受力最大,因挤压而破碎,因为不存在旋转力量,脊柱的后柱不受影响,因而仍保留了脊柱的稳定性,但破碎的椎体及椎间盘能够突出于椎管前方,损伤脊髓而产生神经症状。

脊柱外科临床路径表单3.19-1

脊柱外科临床路径表单3.19-1

脊柱外科临床路径表单

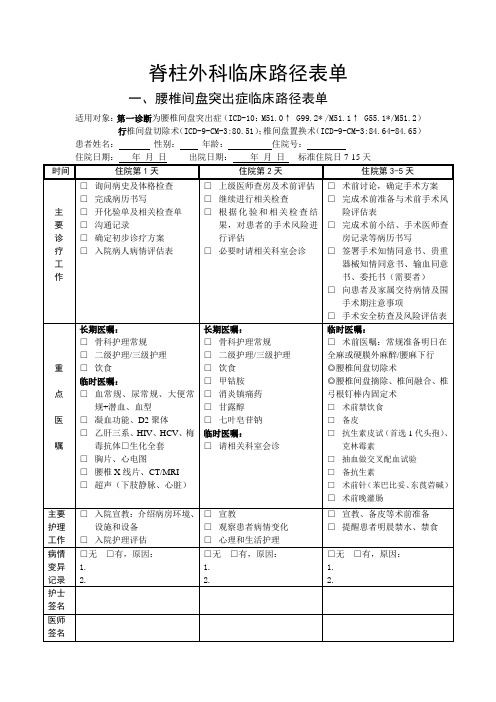

一、腰椎间盘突出症临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为腰椎间盘突出症(ICD-10:M51.0↑ G99.2* /M51.1↑ G55.1*/M51.2)行椎间盘切除术(ICD-9-CM-3:80.51);椎间盘置换术(ICD-9-CM-3:84.64-84.65)患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

二、颈椎病(脊髓型)临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为颈椎病(ICD-10:M47.1↑G99.2*)

行颈前路减压植骨固定、颈后路减压植骨固定、颈前后联合入路减压植骨固定术

(ICD-9-CM-3:81.02-81.03)

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

住院日期:年月日出院日期:年月日标准住院日7-15天

三、腰椎管狭窄症临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为腰椎管狭窄症

行椎间盘切除椎间融合内固定术

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

四、骨质疏松症临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为骨质疏松伴有病理性骨折

行经皮椎体成形术或静滴唑来膦酸治疗

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

住院日期:年月日出院日期:年月日标准住院日10-28天

五、脊柱骨折临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为颈椎、胸腰椎骨折

行颈胸腰椎切开复位内固定术

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

六、骨折取内固定装置临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为胸腰椎骨折术后

行胸腰椎椎骨取内固定术

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

七、坐骨神经痛临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为坐骨神经痛、腰椎间盘突出症行保守治疗

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:。

脊柱外科临床路径表单3.19-1

脊柱外科临床路径表单

一、腰椎间盘突出症临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为腰椎间盘突出症(ICD-10:M51.0↑ G99.2* /M51.1↑ G55.1*/M51.2)行椎间盘切除术(ICD-9-CM-3:80.51);椎间盘置换术(ICD-9-CM-3:84.64-84.65)患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

二、颈椎病(脊髓型)临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为颈椎病(ICD-10:M47.1↑G99.2*)

行颈前路减压植骨固定、颈后路减压植骨固定、颈前后联合入路减压植骨固定术

(ICD-9-CM-3:81.02-81.03)

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

住院日期:年月日出院日期:年月日标准住院日7-15天

三、腰椎管狭窄症临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为腰椎管狭窄症

行椎间盘切除椎间融合内固定术

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

四、骨质疏松症临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为骨质疏松伴有病理性骨折

行经皮椎体成形术或静滴唑来膦酸治疗

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

住院日期:年月日出院日期:年月日标准住院日10-28天

五、脊柱骨折临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为颈椎、胸腰椎骨折

行颈胸腰椎切开复位内固定术

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

六、骨折取内固定装置临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为胸腰椎骨折术后

行胸腰椎椎骨取内固定术

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:

七、坐骨神经痛临床路径表单

适用对象:第一诊断为坐骨神经痛、腰椎间盘突出症

行保守治疗

患者姓名:性别:年龄:住院号:。

NASS循证临床指南:脊柱外科手术中的抗凝治疗(2009版)

North American Spine SocietyEvidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine CareAntithrombotic Therapies in Spine SurgeryNASS Evidence-Based Guideline Development CommitteeChristopher M. Bono, MD, Committee Chair William C. Watters III, MD, Committee Chair Michael H. Heggeness, MD, PhD Daniel K. Resnick, MD, William O. Shaffer, MD Jamie Baisden, MD Peleg Ben-Galim, MD John E. Easa, MDRobert Fernand, MD Tim Lamer, MD Paul G. Matz, MDRichard C. Mendel, MD Rajeev K. Patel, MD Charles A. Reitman, MD John F . T oton, MDFinancial StatementThis clinical guideline was developed and funded in its entirety by the North American Spine Society (NASS). All participating authors have submitted a disclosure form relative to potential conflicts of interest which is kept on file at NASS.CommentsComments regarding the guideline may be submitted to the North American Spine Society and will be consid-ered in development of future revisions of the work.North American Spine SocietyEvidence-Based Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine CareAntithrombotic Therapies in Spine SurgeryCopyright © 2009 North American Spine Society7075 Veterans BoulevardBurr Ridge, IL 60527630.230.3600ISBN: 1-929988-26-5This clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specific procedure or treatment is toI. IntroductionObjectiveThe objective of the North American Spine So-ciety (NASS) Evidence-Based Clinical Guideline on Antithrombotic Therapies in Spine Surgery is to provide evidence-based recommendations to address key clinical questions surrounding the use of antithrombotic therapies in spine surgery. The guideline is intended to address these questions based on the highest quality clinical literature avail-able on this subject as of February 2008. The goals of the guideline recommendations are to assist in delivering optimum, efficacious treatment with the goal of preventing thromboembolic events.Scope, Purpose and Intended User This document was developed by the North American Spine Society Evidence-based Guideline Development Committee as an educational toolto assist spine surgeons in minimizing the risk of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). The NASS Clinical Guideline on Antithrombotic Therapies in Spine Surgery dis-cusses the incidence of DVT/PE in the population of patients undergoing spinal surgery. Recom-mendations are made to address the utilization of chemoprophylaxis and mechanical prophylaxis, with discussion of wound complications and risks associated with prophylactic measures.THIS GUIDELINE DOES NOT REPRESENT A “STANDARD OF CARE,” nor is it intended as a fixed treatment protocol. It is anticipated that there will be patients who will require less or more extensive prophylaxis than the average. It is also ac-knowledged that in atypical cases, treatment falling outside this guideline will sometimes be necessary. This guideline should not be seen as prescribing the type, frequency or duration of intervention. Treat-ment should be based on the individual patient’s need and doctor’s professional judgment. This document is designed to function as a guideline and should not be used as the sole reason for denial of treatment and services. This guideline is not in-tended to expand or restrict a health care provider’s scope of practice or to supersede applicable ethical standards or provisions of law.Patient PopulationThe patient population for this guideline encom-passes adults (18 years or older) undergoing spine surgery.This clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specific procedure or treatment is toII. Guideline Development MethodologyThrough objective evaluation of the evidence and transparency in the process of making recom-mendations, it is NASS’ goal to develop evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of adult patients with various spinal conditions. These guidelines are developed for educational purposes to assist practitioners in their clinical decision-making processes. It is anticipated that where evidence is very strong in support of recommendations, these recommendations will be operationalized into performance measures.Multidisciplinary CollaborationWith the goal of ensuring the best possible carefor adult patients suffering with back pain, NASS is committed to multidisciplinary involvement in the process of guideline and performance measure development. To this end, NASS has ensured that representatives from medical, interventional and surgical spine specialties have participated in the development and review of all NASS guidelines.It is also important that primary care providers and musculoskeletal specialists who care for pa-tients with spinal complaints are represented in the development and review of guidelines that address treatment by first contact physicians, and NASS has involved these providers in the development process as well. To ensure broad-based representa-tion, NASS has invited and welcomes input from other societies and specialties.Evidence Analysis T raining of All NASS Guideline DevelopersNASS has initiated, in conjunction with the Uni-versity of Alberta’s Centre for Health Evidence, an online training program geared toward educat-ing guideline developers about evidence analysis and guideline development. All participants in guideline development for NASS have completed the training prior to participating in the guide-line development program at NASS. This train-ing includes a series of readings and exercises, or interactivities, to prepare guideline developers for systematically evaluating literature and developing evidence-based guidelines. The online course takes approximately 15-30 hours to complete and partici-pants are awarded CME credit upon completion of the course.Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of InterestAll participants involved in guideline development have disclosed potential conflicts of interest to their colleagues and their potential conflicts have been documented for future reference. They will not be published in any guideline, but kept on file for ref-erence, if needed. Participants have been asked to update their disclosures regularly throughout the guideline development process.Levels of Evidence and Grades of RecommendationNASS has adopted standardized levels of evidence (Appendix B) and grades of recommendation (Appendix C) to assist practitioners in easily un-derstanding the strength of the evidence and rec-ommendations within the guidelines. The levels of evidence range from Level I (high quality random-ized controlled trial) to Level V (expert consensus). Grades of recommendation indicate the strength of the recommendations made in the guideline based on the quality of the literature.Grades of Recommendation:A: Good evidence (Level I studies with consistent finding) for or against recommending intervention.B: Fair evidence (Level II or III studies with consistent findings) for or against recommending intervention.This clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specific procedure or treatment is toC: Poor quality evidence (Level IV or V studies) for or against recommending intervention.I: Insufficient or conflicting evidence not allow-ing a recommendation for or against intervention.The criteria for assigning these levels of evidence and grades of recommendation are the same as those used by the Journal of Bone and Joint Sur-gery, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Re-search, the journal Spine and the Pediatric Ortho-paedic Society of North America.In evaluating studies as to levels of evidence for this guideline, the study design was interpretedas establishing only a potential level of evidence. As an example, a therapeutic study designed as a randomized controlled trial would be considered a potential Level I study. The study would then be further analyzed as to how well the study design was implemented and significant short comings in the execution of the study would be used to down-grade the levels of evidence for the study’s conclu-sions. In the example cited previously, reasons to downgrade the results of a potential Level I ran-domized controlled trial to a Level II study would include, among other possibilities, an underpow-ered study (patient sample too small, variance too high), inadequate randomization or masking of the group assignments and lack of validated outcome measures.In addition, a number of studies were reviewed several times in answering different questions within this guideline. How a given question was asked might influence how a study was evaluated and interpreted as to its level of evidence in an-swering that particular question. For example, a randomized control trial reviewed to evaluate the differences between the outcomes of patients who received antibiotic prophylaxis with those who did not might be a well designed and implemented Level I therapeutic study. This same study, howev-er, might be classified as giving Level II prognostic evidence if the data for the untreated controls were extracted and evaluated prognostically.Guideline Development Process⏹Step 1: Identification of Clinical Questions Trained guideline participants were asked to submit a list of clinical questions that the guideline should address. The lists were compiled into a master list, which was then circulated to each member with a request that they independently rank the questions in order of importance for consideration in the guideline. The most highly ranked questions, as determined by the participants, served to focus the guideline.⏹Step 2: Identification of Work Groups Multidisciplinary teams were assigned to work groups and assigned specific clinical questions to address. Because NASS is comprised of surgical, medical and interventional specialists, it is impera-tive to the guideline development process that a cross section of NASS membership is represented on each group whenever feasible. This also helps to ensure that the potential for inadvertent biases in evaluating the literature and formulating recom-mendations is minimized.⏹Step 3: Identification of Search T erms andParametersOne of the most crucial elements of evidence analysis to support development of recommenda-tions for appropriate clinical care is the compre-hensive literature search. Thorough assessment of the literature is the basis for the review of existing evidence and the formulation of evidence-based recommendations. In order to ensure a thorough literature search, NASS has instituted a Literature Search Protocol (Appendix D) which has been fol-lowed to identify literature for evaluation in guide-line development. In keeping with the Literature Search Protocol, work group members have iden-This clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specific procedure or treatment is totified appropriate search terms and parameters to direct the literature search.Specific search strategies, including search terms, parameters and databases searched, are documented in the appendices (Appendix E).⏹Step 4: Completion of the LiteratureSearchAfter each work group identified search terms/ parameters, the literature search was implemented by a medical/research librarian, consistent with the Literature Search Protocol.Following these protocols ensures that NASS rec-ommendations (1) are based on a thorough review of relevant literature; (2) are truly based on a uni-form, comprehensive search strategy; and (3) rep-resent the current best research evidence available. NASS maintains a search history in EndNote,™ for future use or reference.⏹Step 5: Review of Search Results/Identification of Literature to Review Work group members reviewed all abstracts yield-ed from the literature search and identified the literature they would review in order to address the clinical questions, in accordance with the Litera-ture Search Protocol. Members identified the best research evidence available to answer the targeted clinical questions. That is, if Level I, II and/or III literature is available to answer specific questions, the work group was not required to review Level IV or V studies.⏹Step 6: Evidence AnalysisMembers of the work group independently devel-oped evidentiary tables summarizing study conclu-sions, identifying strengths and weaknesses and assigning levels of evidence. In order to systemati-cally control for potential biases, at least two work group members reviewed each article selected and independently assigned levels of evidence to the literature using the NASS levels of evidence. Any discrepancies in scoring have been addressed by two or more reviewers. The consensus level (the level upon which two thirds of reviewers were in agreement) was then assigned to the article.As a final step in the evidence analysis process, members identified and documented gaps in the evidence to educate guideline readers about where evidence is lacking and help guide further needed research by NASS and other societies.⏹Step 7: Formulation of Evidence-BasedRecommendations and Incorporation ofExpert ConsensusWork groups held Web casts to discuss the evi-dence-based answers to the clinical questions, the grades of recommendations and the incorporation of expert consensus. Expert consensus has been incorporated only where Level I-IV evidence is insufficient and the work group has deemed that a recommendation is warranted. Transparency in the incorporation of consensus is crucial, and all con-sensus-based recommendations made in this guide-line very clearly indicate that Level I-IV evidence is insufficient to support a recommendation and that the recommendation is based only on expert con-sensus.Consensus Development ProcessVoting on guideline recommendations was con-ducted using a modification of the nominal group technique in which each work group member independently and anonymously ranked a recom-mendation on a scale ranging from 1 (“extremely inappropriate”) to 9 (“extremely appropriate”). Consensus was obtained when at least 80% of work group members ranked the recommendation as 7, 8 or 9. When the 80% threshold was not at-tained, up to three rounds of discussion and voting were held to resolve disagreements. If disagree-ments were not resolved after these rounds, no recommendation was adopted.This clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specific procedure or treatment is toAfter the recommendations were established, work group members developed the guideline content, addressing the literature which supports the recom-mendations.⏹Step 8: Submission of the Draft Guidelinesfor Review/CommentGuidelines were submitted to the full Evidence-based Guideline Development Committee, the Research Council Director and the Advisory Panel for review and comment. The Advisory Panel is comprised of representatives from physical medi-cine and rehab, pain medicine/management, or-thopedic surgery, neurosurgery, anesthesiology, rheumatology, psychology/psychiatry and family practice. Revisions to recommendations were con-sidered for incorporation only when substantiated by a preponderance of appropriate level evidence.⏹Step 9: Submission for Board Approval After any evidence-based revisions were incorpo-rated, the drafts were prepared for NASS Board review and approval. Edits and revisions to recom-mendations and any other content were considered for incorporation only when substantiated by a preponderance of appropriate level evidence.⏹Step 10: Submission for Endorsement,Publication and National GuidelineClearinghouse (NGC) InclusionFollowing NASS Board approval, the guidelines were slated for publication, submitted for endorse-ment to all appropriate societies and submitted for inclusion in the National Guidelines Clearinghouse (NGC). No revisions were made at this point in the process, but comments have been and will be saved for the next iteration.⏹Step 11: Identification and Development ofPerformance MeasuresThe recommendations will be reviewed by a group experienced in performance measure development (eg, the AMA Physician’s Consortium for Per-formance Improvement) to identify those recom-mendations rigorous enough for measure develop-ment. All relevant medical specialties involved in the guideline development and at the Consortium will be invited to collaborate in the developmentof evidence-based performance measures related to spine care.⏹Step 12: Review and Revision ProcessThe guideline recommendations will be reviewed every three years by an EBM-trained multidisci-plinary team and revised as appropriate based on a thorough review and assessment of relevant litera-ture published since the development of this ver-sion of the guideline.This clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specific procedure or treatment is toThis clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of care reasonably directed to obtaining the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding any specific procedure or treatment is to III. Incidence of DVT/PE in Spine SurgeryIn order to appreciate the incidence of these thrombo-sis-related complications in patients undergoing spinal surgery without antithrombotic prophylaxis, the work group performed a comprehensive literature search and analysis. The group reviewed 45 articles that were selected from a search of MEDLINE (PubMed), Co-chrane Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science and EMBASE Drugs & Pharmacology that addressed the incidence and natural history of DVT and PE as-sociated with spinal surgery.Analysis of the questions related to the natural history of DVT in spinal surgery patients not receiving any prophylactic therapies was difficult due to a number of issues.1. Very few studies have been done in recent years inwhich absolutely no prophylaxis was used. Me-chanical pumps and/or compressive stockings are widely and routinely used after spinal surgery so that studies without such are rare.2. The diagnostic method for DVT and PE varywidely between publications. Older studies report only clinically evident thrombotic events. More recent studies, in large part due to evolving tech-nology, rely on a variety of different diagnostic methods including radionuclide scans, venogramsor ultrasound-based imaging. Thus, comparison of outcomes between different studies that use distinctly different diagnostic criteria is of ques-tionable validity.3. The patient populations addressed in the worldliterature vary widely. The study groups varied in age, ethnicity (potentially influencing genetic susceptibility), magnitude and length of surgery, and postoperative mobilization, all of which might influence the risk for thromboembolic disease. For example, it is well-established that bed rest isa risk factor for DVT. However, the pace at which patients are mobilized after spinal surgery varies widely. Mobilization protocols are rarely reported in detail in spine surgical studies.Because of these issues, the work group was unable to definitively answer the posed questions related to incidence of DVT/PE in spinal surgery patients not re-ceiving prophylactic antithrombotic therapies. How-ever, the work group felt that several important sug-gestions can be made based on the literature reviewed. These are included below along with a detailed analy-sis of the small subset of papers that met the guide-line’s inclusion criteria and provided information that was germane to the discussion of incidence in this patient population.The body of scientific and clinical literature on the topic of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) is extensive. Either can occur spon-taneously or after a risk-enhancing event such as an injury or a surgical procedure. A variety of factors, including the patient’s health and genetic background, can influence the risk of this life threatening complica -tion.A. Incidence of DVT/PE in Unprophylaxed PatientsManaging this risk in patients undergoing spinalsurgery can pose substantial challenges. Treatment of DVT or a PE using anticoagulants in the immediate postoperative period may potentially lead to cata-strophic neurologic decline from epidural bleeding at the surgical site.What is the overallrate (symptomatic and asymptomatic) of DVT or PE following elective spinal surgery without any form of prophylaxis? What are the relative rates of clinically symptomatic DVT or PE (including fatal PE) without any form or prophylaxis following elective cervical, thoracic, and lumbar surgery?Work Group Conclusions/Suggestions:1. Deep vein thrombosis and subsequent pulmonary embolus can occur following spinal surgery, which in turn can lead to morbidity and death. Anyone participating in the careof spinal surgery patients should be aware of these conditions as known potential events.2. The incidence of DVT and PE in patients undergoing spinal surgery likely varies according to the magnitude of the surgery and perioperative mobilization.3. The use of “historical controls” to address the incidence of DVT or PE in a perioperative population is probably not appropriate.4. Clinical examination alone is not a reliable method to confirm the diagnosisof a DVT. Objective diagnostic methods,such as venography or Doppler ultrasound, should be used to confirm a suspected DVTin postoperative spine patients. Future studies to characterize the incidence ofDVT in postoperative spine patients should use objective diagnostic methods such as venography or Doppler ultrasound.Gruber et al18 performed a prospective comparative study to determine the incidence of bleeding compli-cations in patients undergoing lumbar disc surgery treated with minidose heparin-dihydroergotamine (DHE) or placebo. Of the 50 patients included in the study, 25 received 2500IU heparin-DHE twice daily and 25 were assigned to the placebo group. Injections were administered two hours preoperatively, with postoperative administration at 12-hour intervals for at least seven days or until the patient was discharged from the hospital. Of the 25 assigned to the control group, five had received heparin at another hospi-tal and were excluded from the analysis. Surgeons reported bleeding and, if clinically suspected, DVT was diagnosed by phlebogram, plethysmography, Doppler ultrasound or I125 fibrinogen test. If a PE was suspected, a chest radiograph, ECG, ventilation-perfusion scan or pulmonary angiogram was obtained. The authors reported no clinically evident DVT or PE events in this small series of consecutive patients. The authors noted increased intraoperative bleeding in 24% (6/25) of patients in the heparin-DHE group and 28% in the placebo group, a difference that was not statistically significant.In critique of this study, diagnostic methods for DVT were not standardized and only conducted when prompted by clinical suspicion. Furthermore, patient numbers were quite low and the definition of “lum-bar disc operations” was unclear. Due to these meth-odological limitations, this potential Level II study provides Level III evidence of a low risk of DVT/PE in patients undergoing lumbar disc surgery.Joffe et al20 reported results of a prospective case se-ries investigating the incidence of DVT in patients un-dergoing elective neurosurgical procedures. Of the 23 neurosurgical patients included in the study, only 10 were spinal cases. All patients were screened daily for the duration of their hospital stay (which was at least seven days) for DVT with an I125 fibrinogen test and Doppler ultrasound. The authors reported that 60% of the spinal patients (6/10) developed asymptomatic postoperative DVT. They concluded that neurosurgi-cal patients are at risk for DVT and that these patientsThis clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods ofare often asymptomatic. Based on their findings, the authors further suggested that DVT will be underdiag-nosed by clinical criteria alone.In critique, this was a very small study consisting of only a few spinal patients without details about the type and extent of spine surgery. Due to these weak-nesses, this potential Level IV study provides Level V evidence that asymptomatic DVT is not uncommon in a nonselect group of patients undergoing elective spinal surgery likely followed by prolonged periods of bed rest, an assumption made based on the year the study was published. The applicability of these find-ings today is questionable given that prolonged peri-ods of bed rest are no longer recommended following surgery.Lee et al22 conducted a prospective comparative study to determine the rate of DVT following elective major reconstructive spinal surgery without antithrombotic therapies in an East Asian (Korean) population. All 313 patients included in the study were screened via duplex ultrasonography between the fifth and seventh postoperative days. Authors reported a 1.3% (4/313) overall incidence of DVT, with a clinically symptom-atic presentation in only 0.3% (1/313) of patients. The authors concluded that East Asians undergoing these procedures do not get DVT often enough to warrant prophylaxis. The authors further suggested that rou-tine screening and prophylaxis in this specific patient population is not warranted.In critique of this study, an unknown number of pe-diatric patients were included. A subgroup analysis addressing the adult population was not provided. In addition, patients were treated with postoperative bed rest for a mean of 7.4 days. This potential Level I study provides Level II evidence suggesting a lower incidence of DVT after elective major reconstructive spinal surgery without antithrombotic therapy than previously reported. Although the authors concluded this incidence was related to the ethnicity of the pa-tient group, it should be noted that other unidentified factors may have influenced the DVT rate.Oda et al30 reported a prospective comparative study documenting the prevalence of DVT after posterior spinal surgery in patients not receiving antithrombotic therapies. Of the 134 patients included in the study, 110 were screened for DVT by venography within 14 days of surgery (mean = 7.2 days) and clinically fol-lowed for at least three months. Authors reported that 15.5% (17/110) of patients had venographic evidence of DVT, while none had clinical manifestations of DVT. The authors also indicated the prevalence of DVT by surgical region; 26.5% of lumbar, 14.3% of thoracic and 5.6% of cervical patients had venograph-ic evidence of DVT. Statistical comparison between patients who did and did not have DVT demonstrated that increased age was a statistically significant risk factor (Mann–Whitney test; P< 0.05). The authors concluded that the incidence of DVT after posterior spinal surgery is higher than generally appreciated. Therefore, they felt that further study is necessary to clarify the appropriate screening method for and pro-phylaxis of DVT after spinal surgery.This study provides Level II evidence that the rateof DVT in postoperative spine surgery patients may be underestimated. Clinical manifestations are not reliable for the diagnosis of DVT. Increased age and posterior lumbar surgery are risk factors. It should also be noted that all patients included in this study had an interval of bed rest following surgery. The applicability of these findings today is questionable given that prolonged periods of bed rest are no longer recommended following surgery.Uden et al40 described a retrospective case series documenting the rate of clinically evident DVT in a population of 1229 patients treated surgically with Harrington instrumentation followed by three to five weeks of bed rest. Diagnosis of DVT was confirmed via contrast and/or isotope phlebography only when clinically suspected or by autopsy. The authors re-ported a 0.65% (8/1229) incidence of DVT and 0.08% (1/1229) incidence of PE in this scoliosis patient population.In critique of this study, patients were not enrolled at the same point in their disease and some patients wereThis clinical guideline should not be construed as including all proper methods of care or excluding other acceptable methods of。

脊柱疾病患者指南

脊柱疾病患者指南疾病描述退变性椎间盘疾病老化和/或外伤导致椎间盘(脊柱椎体间的减震器)磨损。

退变性脊柱不稳退变性脊柱不稳脊柱关节(椎间盘和小关节)软骨随年龄增加而磨损,导致脊柱不稳。

坐骨神经痛疼痛、麻木、麻刺感、一侧或双侧下肢无力,这是由于一个或多个坐骨神经分支的炎症或压迫导致的(神经症状)。

椎间盘脱出椎间盘破裂,有时会导致对神经或脊髓的压迫,产生一侧或双侧上肢或下肢的疼痛、麻木、无力(神经症状),椎间盘脱出导致的神经疼痛在坐位时通常会加重。

狭窄狭窄椎管面积缩小,如果狭窄压迫神经,则导致神经分布区疼痛。

通常站立或是行走一段时间后,压迫会导致一侧或双侧腿痛,坐位可缓解疼痛。

腰椎滑脱症由于椎间盘退变或是儿童或青少年时期的骨折导致一个椎体相对于另一个椎体滑移,滑移和不稳可能导致神经压迫症状,除此之外,还造成活动能力丧失的疼痛。

脊柱侧凸脊柱曲度通常是由于先天原因,或是未知或退变的原因导致的,最常见的原因是青少年特发性胸椎侧凸,青春期女孩多见。

骨质疏松脊柱钙质丢失,最常见于绝经后老年妇女,它是一种悄无声息的疾病,可能直到脆弱的骨骼出现骨折才被发现。

骨折/脱位脊柱骨折通常由外伤导致(最常见的原因是交通事故)和高空坠落,也可能出现在骨质疏松症患者的轻微创伤后。

另一方面,脊柱脱位几乎总是由高能量损伤导致。

肿瘤肿瘤可能是良性或恶性,尽管肿瘤可以是脊柱原发性的,但大多数情况下,是由其他器官的恶性肿瘤转移导致的(转移灶),脊柱肿瘤典型的是夜间痛,全身不适,偶尔出现截瘫。

感染脊柱的骨骼和椎间盘可能发生感染,通常是由血液或尿液源性细菌引起的,它通常发生在很老的患者或是很年轻的患者,另外就是免疫功能低下的患者。

可选择的治疗方式治疗退化性椎间盘疾病,脊柱不稳,坐骨神经痛,椎间盘脱出,狭窄和滑脱,通常最初先使用止痛药、物理治疗、脊柱类固醇注射进行治疗,当这些治疗失败后,可采用手术治疗,手术通常为神经减压,然后可进行脊柱融合或者不进行融合。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

脊柱脊髓损伤定义:脊柱脊髓损伤常发发生于工矿,交通事故,战时和自然灾害时可成批发生。

伤情严重复杂,多发伤、复合伤较多,并发症多,合并脊髓伤时预后差,甚至造成终生残废或危及生命。

症状体征一,脊柱骨折1,有严重外伤史,如高空落下,重物打击头颈或肩背部,塌方事故,交通事故等。

2,病人感受伤局部疼痛,颈部活动障碍,腰背部肌肉痉挛,不能翻身起立,骨折局部可扪及局限性后突畸形。

3,由于腹膜后血肿对植物神经刺激,肠蠕动减慢,常出现腹胀,腹痛等症状,有时需与腹腔脏器损伤相鉴别。

二,合并脊髓和神经根损伤脊髓损伤后,在损伤平面以下的运动,感觉,反射及括约肌和植物神经功能受到损害。

1,感觉障碍损伤平面以下的痛觉,温度觉,触觉及本体觉减弱或消失。

2,运动障碍脊髓休克期,脊髓损伤节段以下表现为软瘫,反射消失,休克期过后若是脊髓横断伤则出现上运动神经元性瘫痪,肌张力增高,腱反射亢进,出现髌阵挛和踝阵挛及病理反射。

3,括约肌功能障碍脊髓休克期表现为尿潴留,系膀胱逼尿肌麻痹形成无张力性膀胱所致,休克期过后,若脊髓损伤在骶髓平面以上,可形成自动反射膀胱,残余尿少于100ml,但不能随意排尿,若脊髓损伤平面在圆锥部骶髓或骶神经根损伤,则出现尿失禁,膀胱的排空需通过增加腹压(用手挤压腹部)或用导尿管来排空尿液,大便也同样出现便秘和失禁。

4,不完全性脊髓损伤损伤平面远侧脊髓运动或感觉仍有部分保存时称之为不完全性脊髓损伤,临床上有以下几型:(1)脊髓前部损伤:表现为损伤平面以下的自主运动和痛觉消失,由于脊髓后柱无损伤,病人的触觉、位置觉、振动觉、运动觉和深压觉完好。

(2)脊髓中央性损伤:在颈髓损伤时多见,表现上肢运动丧失,但下肢运动功能存在或上肢运动功能丧失明显比下肢严重,损伤平面的腱反射消失而损伤平面以下的腱反射亢进。

(3)脊髓半侧损伤综合症(Brown-Sequards Symdrome):表现损伤平面以下的对侧痛温觉消失,同侧的运动功能,位置觉,运动觉和两点辨觉丧失。

(4)脊髓后部损伤:表现损伤平面以下的深感觉,深压觉,位置觉丧失,而痛温觉和运动功能完全正常,多见于椎板骨折伤员。

检查方法本病的辅助检查方法有以下几种:1. X线检查常规摄脊柱正侧位,必要时照斜位,阅片时测量椎体前部和后部的高度与上下邻椎相比较;测量椎弓根间距和椎体宽度;测量棘突间距及椎间盘间隙宽度并与上下邻近椎间隙相比较,测量正侧位上椎弓根高度,X片基本可确定骨折部位及类型。

2. CT检查有利于判定移位骨折块侵犯椎管程度和发现突入椎管的骨块或椎间盘。

3. MRI(磁共振)检查对判定脊髓损伤状况极有价值,MRI可显示脊髓损伤早期的水肿,出血,并可显示脊髓损伤的各种病理变化,脊髓受压,脊髓横断,脊髓不完全性损伤,脊髓萎缩或囊性变等。

4. SEP(体感诱发电位) 是测定躯体感觉系统(以脊髓后索为主)的传导功能的检测法,对判定脊髓损伤程度有一定帮助,现在已有MEP(运动诱导电位)。

本病的治疗有包括以下几点:(一)急救和搬运1. 脊柱脊髓伤有时合并严重的颅脑损伤、胸部或腹部脏器损伤、四肢血管伤,危及伤员生命安全时应首先抢救。

2. 凡疑有脊柱骨折者,应使病人脊柱保持正常生理曲线。

切忌使脊柱作过伸、过屈的搬运动作,应使脊柱在无旋转外力的情况下,三人用手同时平抬平放至木板上,人少时可用滚动法。

对颈椎损伤的病人,要有专人扶托下颌和枕骨,沿纵轴略加牵引力,使颈部保持中立位,病人置木板上后用砂袋或折好的衣物放在头颈的两侧,防止头部转动,并保持呼吸道通畅。

(二)单纯脊柱骨折的治疗1. 胸腰段骨折轻度椎体压缩属于稳定型。

患者可平卧硬板床,腰部垫高。

数日后即可背伸肌锻炼。

经功能疗法可使压缩椎体自行复位,恢复原状。

3~4周后即可在胸背支架保护下下床活动。

2. 胸腰段重度压缩超过三分之一应予以闭合复位。

可用两桌法过伸复位。

用两张高度相差30cm左右的桌子,桌上各放一软枕,伤员俯卧,头部置于高桌上,两手把住桌边,两大腿放于低桌上,要使胸骨柄和耻骨联合部悬空,利用悬垂的体重逐渐复位。

复位后在此位置上石膏背心固定。

固定时间为3个月。

3. 胸腰段不稳定型脊柱骨折椎体压缩超过1/3以上、畸形角大于20°、或伴有脱位可考虑开放复位内固定。

4. 颈椎骨折或脱位压缩移位轻者,用颌枕带牵引复位,牵引重量3 ~ 5kg。

复位后用头胸石膏固定3个月。

压缩移位重者,可持续颅骨牵引复位。

牵引重量可增加到6 ~ 10kg。

摄X线片复查,复位后用头胸石膏或头胸支架固定3个月,牵引复位失败者需切开复位内固定。

(三)脊柱骨折合并脊髓损伤脊髓损伤的功能恢复主要取决于脊髓损伤程度,但及早解除对脊髓的压迫是保证脊髓功能恢复的首要问题。

手术治疗是对脊髓损伤患者全面康复治疗的重要部分。

手术目的是恢复脊柱正常轴线,恢复椎管内径,直接或间接地解除骨折块或脱位对脊髓神经根的压迫,稳定脊柱(通过内固定加植骨融合)。

其手术方法有:1.颈椎前路减压植骨融合术对颈3以下的颈椎骨折可行牵引复位,前路减压或次全椎体切除、植骨融合术,用钢板螺钉内固定或颈围外固定。

明显不稳者可继续颅骨牵引或头胸石膏固定。

2.颈椎后路手术脱位为主者牵引复位后可行后路金属夹内固定及植骨融合术或用钢丝棘突内固定植骨融合,必要时行后路减压钢板螺钉内固定植骨融合术。

3.胸腰段骨折前路手术对胸腰段椎体爆裂性或粉碎性骨折,多行前路减压、植骨融合、钢板螺钉内固定术。

对陈旧性骨折可行侧前方减压术。

4.胸腰段骨折后路手术后路手术包括椎板切除减压、用椎弓根螺定钢板或钢棒复位内固定,必要时行植骨融合术也可用哈灵顿棒或鲁凯棒钢丝内固定。

(四)综合症法1.脱水疗法应用20%甘露醇250ml;2次/d,目的是减轻脊髓水肿。

2. 激素治疗应用地塞米松10 ~ 20mg静脉滴注,一次/d。

对缓解脊髓的创伤性反应有一定意义。

3. 一些自由基清除剂如维生素E、A、C及辅酶Q等,钙通道阻滞剂,利多卡因等的应用被认为对防止脊髓损伤后的继发损害有一定好处。

4. 促进神经功能恢复的药物如三磷酸胞苷二钠、维生素B1、B6、B12等。

支持疗法注意维持伤员的水和电解质平衡,热量、营养和维生素的补充。

骨质疏松性骨折骨质疏松性骨折是中老年最常见的骨骼疾病,也是骨质疏松症的严重阶段,具有发病率高、致残致死率高、医疗花费高的特点。

而我国骨质疏松性骨折的诊疗现状是诊断率低、治疗率低、治疗依从性和规范性低。

一、定义(一)骨质疏松性骨折为低能量或非暴力骨折,指在日常生活中未受到明显外力或受到“通常不会引起骨折外力”而发生的骨折,亦称脆性骨折(“通常不会引起骨折外力”指人体从站立高度或低于站立高度跌倒产生的作用力。

骨质疏松性骨折与创伤性骨折不同,是基于全身骨质疏松存在的一个局部骨组织病变,是骨强度下降的明确体现,也是骨质疏松症的最终结果(二)骨质疏松症(osteoporosis,OP)以骨强度下降、骨折风险增加为特征的骨骼系统疾病。

骨强度反映骨骼的两个主要方面,即骨密度和骨质量。

骨质疏松症分为原发性和继发性两大类。

二、骨质疏松性骨折具有以下特点:①骨折患者卧床制动后,将发生快速骨丢失,会加重骨质疏松症;②骨重建异常、骨折愈合过程缓慢,恢复时间长,易发生骨折延迟愈合甚至不愈合;③同一部位及其他部位发生再骨折的风险明显增大;④骨折部位骨量低,骨质量差,且多为粉碎性骨折,复位困难,不易达到满意效果;⑤内固定治疗稳定性差,内固定物及植入物易松动、脱出,植骨易被吸收;⑥多见于老年人群,常合并其他器官或系统疾病,全身状况差,治疗时易发生并发症,增加治疗的复杂性。

骨质疏松性骨折多见于老年人群,尤其是绝经后女性。

发生的常见部位有:胸腰段椎体、髋部(股骨近端)、腕部(桡骨远端)、肱骨近端等;发生了脆性骨折临床上即可诊断骨质疏松症三、骨质疏松性骨折的诊断:(一)临床表现可有疼痛、肿胀和功能障碍,可出现畸形、骨擦感(音)、反常活动;但也有患者缺乏上述典型表现。

具有骨质疏松症的一般表现。

(二)影像学检查1.X线:可确定骨折的部位、类型、移位方向和程度,对骨折诊断和治疗具有重要价值。

X线片除具有骨折的表现外,还有骨质疏松的表现。

2.CT:常用于判断骨折的程度和粉碎情况、椎体压缩程度、椎体周壁是否完整、椎管内的压迫情况。

3.MRI:常用于判断椎体压缩骨折是否愈合、疼痛责任椎及发现隐匿性骨折,并进行鉴别诊断等。

4.全身骨扫描(ECT):适用于无法行MR检查或排除肿瘤骨转移等。

(三)行骨密度检查。

双能X线吸收法测量值是世界卫生组织推荐的骨质疏松症评估方法,是公认的骨质疏松诊断的金标准。

参照WHO推荐的诊断标准,DXA测定骨密度值低于同性别、同种族健康成人的骨峰值不足1个标准差为正常(T值≥-1.0SD);降低1~2.5个标准差为骨量低下或骨量减少(-2.5SD<T值<-1.0SD);降低程度等于或大于2.5个标准差为骨质疏松(T值≤-2.5SD);降低程度符合骨质疏松诊断标准,同时伴有一处或多处骨折为严重骨质疏松。

(四)实验室检查在诊断原发性骨质疏松性骨折时,应排除转移性骨肿瘤、胸腰椎结核、多发性骨髓瘤、甲状旁腺功能亢进等内分泌疾病、类风湿关节炎等免疫性疾病、长期服用糖皮质激素或其他影响骨代谢药物以及各种先天或获得性骨代谢异常疾病。

1.基本检查项目:血尿常规,肝肾功能,血钙、磷、碱性磷酸酶等。

2.选择性检查项目:红细胞沉降率、性腺激素、血清25羟基维生素D (25hydroxyvitaminD,25OHD)、1,25(OH)2D、甲状旁腺激素、24h尿钙和磷、甲状腺功能、皮质醇、血气分析、血尿轻链、肿瘤标志物、放射性核素骨扫描、骨髓穿刺或骨活检等。

3.骨转换生化标志物:IOF推荐Ⅰ型骨胶原氨基末端肽(P1NP)和Ⅰ型胶原羧基末端肽(S⁃CTX),有条件的单位可检测。

(五)诊疗原则及流程骨质疏松性骨折的诊断应结合患者的年龄、性别、绝经史、脆性骨折史、临床表现及影像学和(或)骨密度检查结果进行综合分析,作出诊断。

四、骨质疏松性骨折的治疗原则复位、固定、功能锻炼和抗骨质疏松治疗是治疗骨质疏松性骨折的基本原则。

骨质疏松性骨折的治疗应强调个体化,可采用非手术或手术治疗。

2.治疗(1)非手术治疗适用于症状和体征较轻,影像学检查显示为轻度椎体压缩骨折,或不能耐受手术者。

治疗可采用卧床、支具及药物等方法,但需要定期进行X线片检查,以了解椎体压缩是否进行性加重。

(2)手术治疗椎体强化手术,包括椎体成形术(PVP)和椎体后凸成形术(PKP),是目前最常用的微创手术治疗方法[25-36],适用于非手术治疗无效,疼痛剧烈;不稳定的椎体压缩性骨折;椎体骨折不愈合或椎体内部囊性变、椎体坏死;不宜长时间卧床;能耐受手术者。