信用评级机构[文献翻译]

信用评级机构介绍

Corporate Valuation Consulting

We assist clients in objectively defining, creating, and enhancing their value:

-Financial Reports and Tax Valuations; -Corporation Finance Consulting; -Applied decision Analysis

比利时:根据对整体信誉的评估确认评级机构(尤其是它们在比利 时信用机构中的有效使用),对它们的组织结构与方法进行审查, 尤其注意它们的完整性与独立性。 加拿大:尽管没有设定用来识别评级机构的标准,但通常选择那 些得到国际认可的机构,因为其给出的评级精确且公正,同时已 保持较长的历史。 意大利:根据机构的信誉、客观性、透明度,以及在意大利市场 中所起的作用选择评级机构。

457.60

1,773.40 750.00

701.50

1,714.60 600.00

753.90

1,497.70 300.00

560.80

1,457.20 300.00

穆迪公司的收入来源

Revenue Structured finance 290.8 563.9 2010 14.3% 304.9 27.8% 408.2 13.7% 258.5 2009 2008 17% 411.2 23% 300.5 263 2007 23% 873.3 17% 411.5 15% 274.3 2006 39% 872.6 18% 335.9 12% 233.1 43% 16%

政策法规驱动发展模式

2 、资信评级业务的资格认定

美国的NRSROs (Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organizations) 根据评级机构的市场表现,从监管部门使用评级结果的角度, 认定评级结果,而不是从许可评级机构开展某项评级业务的 角度,认定评级机构开展这项业务的资格。 评级机构必须满足以下条件才能获得NRSRO资质:(1)全国 认可,即该评级机构的信用评级被大多数使用者认为是可信 的和可靠的;(2)评级机构的组织结构合理;(3)有足够 的财力保持其独立经营,不受被评企业的经济压力和控制, 能确保其进行可靠的评级;(4)有足够数量的相关教育背景 和工作经验的评级分析人员,能够胜任对发行人的信用做出 独立完整的评估;(5)评级机构独立于被评级企业;(6) 使用系统化的评级程序,确保可靠和准确的评级;(7)有健 全的内部程序以防止非公开信息的不当使用,而且对该程序 的执行情况有可靠的保证。

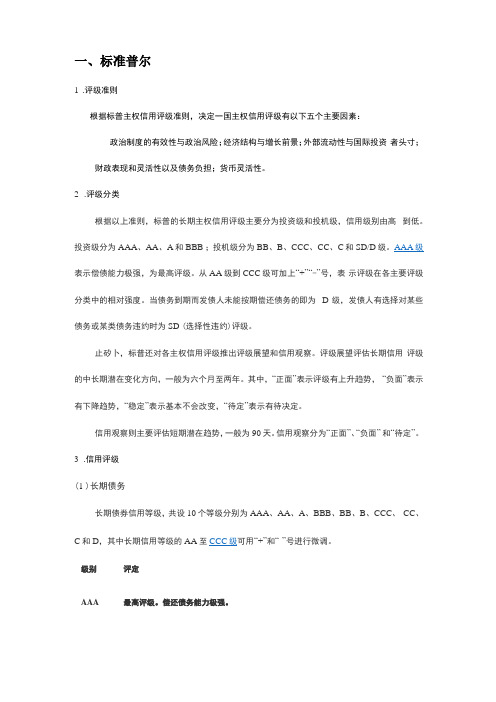

国际三大信用评级机构

一、标准普尔1.评级准则根据标普主权信用评级准则,决定一国主权信用评级有以下五个主要因素:政治制度的有效性与政治风险;经济结构与增长前景;外部流动性与国际投资者头寸;财政表现和灵活性以及债务负担;货币灵活性。

2.评级分类根据以上准则,标普的长期主权信用评级主要分为投资级和投机级,信用级别由高到低。

投资级分为AAA、AA、A和BBB ;投机级分为BB、B、CCC、CC、C和SD/D 级。

AAA级表示偿债能力极强,为最高评级。

从AA级到CCC级可加上“+”“-”号,表示评级在各主要评级分类中的相对强度。

当债务到期而发债人未能按期偿还债务的即为D级,发债人有选择对某些债务或某类债务违约时为SD (选择性违约)评级。

止矽卜,标普还对各主权信用评级推出评级展望和信用观察。

评级展望评估长期信用评级的中长期潜在变化方向,一般为六个月至两年。

其中,“正面”表示评级有上升趋势,“负面”表示有下降趋势,“稳定”表示基本不会改变,“待定”表示有待决定。

信用观察则主要评估短期潜在趋势,一般为90天。

信用观察分为“正面”、“负面” 和“待定”。

3.信用评级(1 )长期债务长期债券信用等级,共设10个等级分别为AAA、AA、A、BBB、BB、B、CCC、CC、C和D,其中长期信用等级的AA至CCC级可用“+”和“-”号进行微调。

级别评定AAA 最高评级。

偿还债务能力极强。

AA偿还债务能力很强,与最高评级差别很小。

偿还债务能力较强,但相对于较高评级的债务/发债人,其偿债 A能力较易受外在环境及经济状况变动的不利因素的影响。

目前有足够偿债能力,但若在恶劣的经济条件或外在环境下其 BBB偿债能力可能较脆弱。

相对于其它投机级评级,违约的可能性最低。

但持续的重大不稳 BB定情况或恶劣的商业、金融、经济条件可能令发债人没有足够能 力偿还债务. 违约可能性较,BB'级高,发债人目前仍有能力偿还债务,但恶劣B 的商业、金融或经济情况可能削弱发债人偿还债务的能力和意愿. CCC 目前有可能违约,发债人须倚赖良好的商业、金融或经济条件才 有能力偿还债务.如果商业、金融、经济条件恶化,发债人可能 会违约.CC目前违约的可能性较高.由于其财务状况,目前正在受监察.在 受监察期内,监管机构有权审定某一债务较其它债务有优先偿 付权. 当债务到期而发债人未能按期偿还债务时,纵使宽限期未满,标 SD/D准普尔亦会给予'D'评级,阴雨准普尔相信债款可于宽限期内清还.此外,如正在申请破产或已作出类似行动以致债务的偿付受阻时,标准普尔亦会给予①'评级。

国际三大评级机构信用评级定义及方法研究

国际三大评级机构信用评级定义及方法研究一、引言:信用评级是金融市场中的一项重要工具,能够为投资者提供有效的风险评估和参考,指导其投资决策。

国际上主要有三大评级机构,分别是标准普尔(S&P)、穆迪(Moody's)和惠誉(Fitch)。

本文旨在探讨这三大评级机构信用评级的定义及方法。

二、信用评级定义:信用评级是一种对债券、借贷机构、企业、国家或其他金融实体的信用风险进行量化分析的过程。

通过信用评级,投资者可以了解债券违约的潜在风险、财务实力以及该金融实体的还款能力。

信用评级通常采用字母级别的标示,如AAA、AA、A、BBB等,其中AAA代表最高信用等级,表示违约风险极低,而D则代表违约。

三、信用评级方法:三大评级机构在信用评级过程中通常采用以下几种主要方法来评估债券或金融实体的信用风险:1.定性分析:定性分析是评级机构对债券或金融实体的内部因素进行分析的方法。

这包括研究债券或金融实体的管理层、经营状况、财务状况、市场地位等。

通过这种分析,评级机构可以对债券或金融实体的未来发展趋势和违约风险进行评估。

2.定量分析:定量分析是评级机构通过计算债券或金融实体的财务指标来进行分析的方法。

评级机构通常会考虑债券或金融实体的财务健康状况、偿债能力、现金流等指标。

通过这种分析,评级机构可以对债券或金融实体的风险和收益进行量化评估。

3.行业分析:行业分析是评级机构对特定行业的整体风险进行评估的方法。

评级机构会研究行业的市场竞争态势、法规环境、供需状况等因素,通过这种分析可以判断债券或金融实体所在行业的潜在风险。

4.地区或国家风险分析:地区或国家风险分析是评级机构对债券或金融实体所在地区或国家的宏观经济状况进行评估的方法。

评级机构通常会考虑地区或国家的政治稳定性、经济增长前景、货币政策等因素。

四、评级的局限性和争议:尽管信用评级在金融市场中具有重要的作用,但也存在一些局限性和争议。

首先,评级机构依赖于公开的财务数据和市场情报,可能无法获取到准确的信息。

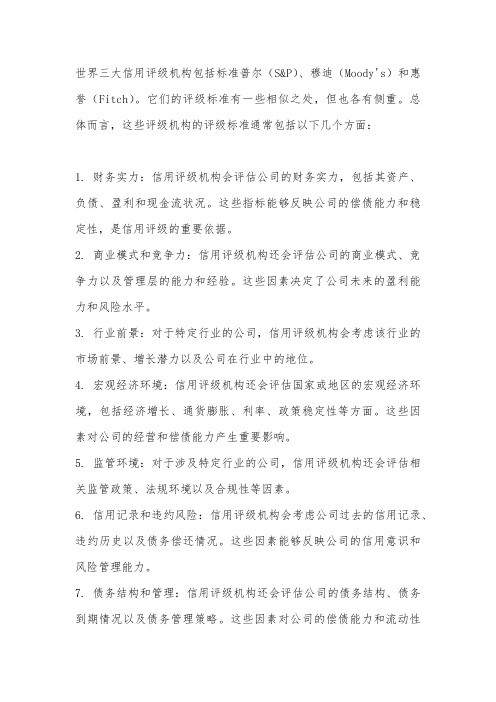

世界三大信用评级机构评级标准

世界三大信用评级机构包括标准普尔(S&P)、穆迪(Moody's)和惠誉(Fitch)。

它们的评级标准有一些相似之处,但也各有侧重。

总体而言,这些评级机构的评级标准通常包括以下几个方面:1. 财务实力:信用评级机构会评估公司的财务实力,包括其资产、负债、盈利和现金流状况。

这些指标能够反映公司的偿债能力和稳定性,是信用评级的重要依据。

2. 商业模式和竞争力:信用评级机构还会评估公司的商业模式、竞争力以及管理层的能力和经验。

这些因素决定了公司未来的盈利能力和风险水平。

3. 行业前景:对于特定行业的公司,信用评级机构会考虑该行业的市场前景、增长潜力以及公司在行业中的地位。

4. 宏观经济环境:信用评级机构还会评估国家或地区的宏观经济环境,包括经济增长、通货膨胀、利率、政策稳定性等方面。

这些因素对公司的经营和偿债能力产生重要影响。

5. 监管环境:对于涉及特定行业的公司,信用评级机构还会评估相关监管政策、法规环境以及合规性等因素。

6. 信用记录和违约风险:信用评级机构会考虑公司过去的信用记录、违约历史以及债务偿还情况。

这些因素能够反映公司的信用意识和风险管理能力。

7. 债务结构和管理:信用评级机构还会评估公司的债务结构、债务到期情况以及债务管理策略。

这些因素对公司的偿债能力和流动性产生重要影响。

8. 政治风险:对于跨国公司或涉及国际业务的企业,信用评级机构会评估相关国家的政治风险、政策稳定性和法律环境等因素。

这些因素可能对公司的经营和偿债能力产生重要影响。

总体而言,世界三大信用评级机构的评级标准都是基于上述因素进行综合评估的。

虽然各家机构的评级标准略有不同,但它们都致力于为客户提供客观、公正的信用评级服务,以帮助投资者做出明智的投资决策。

信用风险评估的机构和机制

信用风险评估的机构和机制信用风险评估是金融领域中一项重要的风险管理工具,旨在评估借款人或债务人按时履行债务的能力。

为了保障金融市场的稳定,许多机构和机制被建立起来,来进行信用风险评估并提供相应的服务。

本文将探讨信用风险评估的机构和机制,以及它们在金融市场中的作用。

一、信用风险评估的机构1. 信用评级机构信用评级机构是专门从事对借款人、发行人或发行的债务工具进行信用评级的机构。

这些机构使用一套标准化的评级方法,根据借款人的信用资质、偿债能力和偿还意愿来评估其信用风险水平。

一些知名的信用评级机构包括标准普尔、穆迪和惠誉。

2. 征信机构征信机构是收集、保存和提供个人和企业信用信息的机构。

它们通过收集借款人的财务和信用记录,为金融机构和其他利益相关方提供信用报告和评估,以帮助它们评估借款人的信用风险。

在中国,最知名的征信机构是中国人民银行征信中心。

3. 金融机构的内部风险管理部门银行和其他金融机构通常设立内部风险管理部门,负责评估和管理信用风险。

他们会使用一系列的模型和方法来评估借款人的信用风险,并制定相应的措施来规避、转移或管理这些风险。

二、信用风险评估的机制1. 信用报告和评级体系信用报告是征信机构提供给金融机构和其他利益相关方的记录借款人信用状况和历史的文件。

它们包含了借款人的个人或企业信息、财务状况、还款记录和信用评级等。

这些信用报告和评级体系为金融机构提供了评估借款人信用风险的重要参考依据。

2. 市场定价机制市场定价机制是指市场对借款人的信用风险进行定价的机制。

在金融市场上,借款人的信用状况会直接影响到借款的利率和条件。

借款人的信用评级越高,他们就越能够以较低的利率获得贷款,反之则可能需要承担更高的利率或被拒绝贷款。

3. 法律和监管机制法律和监管机制是保障金融市场稳定和保护投资者利益的重要组成部分。

这些机制旨在确保金融机构按照合规要求进行信用风险评估,并提供准确、透明和可靠的评估和报告。

结论信用风险评估的机构和机制在金融市场中起着至关重要的作用。

“信用评级”英语怎么说

“信用评级”英语怎么说中文解释:信用评级(Credit Rating),又称资信评级,是一种社会中介服务为社会提供资信信息,或为单位自身提供决策参考。

最初产生于20世纪初期的美国。

1902年,穆迪公司的创始人约翰·穆迪开始对当时发行的铁路债券进行评级。

后来延伸到各种金融产品及各种评估对象。

由于信用评级的对象和要求有所不同,因而信用评级的内容和方法也有较大区别。

我们研究资信的分类,就是为了对不同的信用评级项目探讨不同的信用评级标准和方法。

“信用评级”英语怎么说例句:The Standard & Poor's agency on Friday dealt a heavy blow to the largest world economy as it deprived the US of its top-tier AAA credit rating. Analysts said that could lead to a weakening dollar and threaten China's interests as the country holds colossal amounts of dollar assets.S&P cut the long-term US credit rating to AA-plus, citing concerns about the government's budget deficit and worsening debt prospects despite the earlier bipartisan consensus to raise the country's debt ceiling by $2.4 trillion and cut the deficit by $2.1 trillion over a decade.标准普尔机构周五剥夺了美国AAA最高信用评级,这对美国这一世界最大经济体以沉重的打击。

信用评级机构_信用管理_[共8页]

成立年份 1981 1972 1976 1986 1987 1988 1979 1985 1975 1985 1985 1979 1932 1913 1909 1922

市场定位 本地 本地 本地 本地 本地 本地 本地 本地 本地 本地 本地 银行 银行 全球 全球 全球

长期评级代号 AAA-C A++-D AAA-C AAA-D

信用管理

企业评级数据库对信用评级机构评级结果的公正性尤其重要。

八、信用评级机构

为了降低赊销而带来的坏账风险,英国于 1830 年、美国于 1837 年出现了专门收集和提供企业 信用服务的征信公司。其中,创立于 1841 年的国际著名的美国邓白氏集团(Dun & Bradstreet),奠 定了企业开展信用管理工作的基础。

1.信用评估 邓白氏公司信用评估业务主要有两种模式:一种是企业之间进行交易时的信用评级,另一种是 企业向银行贷款时的信用评级。这两种模式在咨询对象和咨询内容上都有一些区别,但信用报告大 致包括以下几个方面的内容: (1)公司概览。包括地址、电话号码、业务范围、成立时间、领导人有关资料、公司架构等基 本资料; (2)付款记录和分析。包括公司 12~24 个月的拖欠账款记录,同行业企业付款情况的比较分析, 对公司的付款能力和风险的分析预测和评估; (3)财务状况分析。依据资产负债表、损益表等财务报告的相关财务指标,对公司财务状况的 分析,对公司的财务表现、财务压力和风险的评估和预测; (4)经营表现分析。包括诉讼记录、公众记录、新闻机构对公司的评价; (5)营运状况。包括产品品种、生产能力、产量、交易方式、销售地区、原料来源、顾客类别 等资料。

国际上最著名的企业信用管理机构当属美国邓白氏公司。 邓白氏公司(Dun & Bradstreet)是美国历史最悠久的企业信用评估公司之一,成立于 1841 41 年,邓白氏公司创始人刘易斯·塔潘(Lewis Tappan)在纽约成立了第一家征信事务所 The Mercantile Agency;随后 The Mercantile Agency 在 1851 年由其唯一所有者 R.G.Dun 改名为 R.G.Dun & Co;同期,辛辛那提的律师 Jhon M.Bradstreet 在 1849 年创建了 The Bradstreet Company,到 1933 年 R.G.Dun & Co 和 The Bradstreet Company 两公司最终合并成 Dun & Bradstreet。

信贷基本词汇英汉对照(1)-译国译民

信贷基本词汇英汉对照(1)-译国译民翻译公司2M method 2M法3M method 3M法A scores A值Accounting convention 会计惯例Accounting for acquisitions 购并的会计处理Accounting for debtors 应收账款核算Accounting for depreciation 折旧核算Accounting for foreign currencies 外汇核算Accounting for goodwill 商誉核算Accounting for stocks 存货核算Accounting policies 会计政策Accounting standards 会计准则Accruals concept 权责发生原则Achieving credit control 实现信用控制Acid test ratio 酸性测试比率Actual cash flow 实际现金流量Adjusting company profits 企业利润调整Advance payment guarantee 提前偿还保金Adverse trading 不利交易Advertising budget 广告预算Advising bank 通告银行Age analysis 账龄分析Aged debtors analysis 逾期账款分析Aged debtors’ exception report 逾期应收款的特殊报告Aged debtors’ exception report 逾期账款特别报告Aged debtors’ report逾期应收款报告Aged debtors’ report逾期账款报告All—monies clause 全额支付条款Amortization 摊销Analytical questionnaire 调查表分析Analytical skills 分析技巧Analyzing financial risk 财务风险分析Analyzing financial statements 财务报表分析Analyzing liquidity 流动性分析Analyzing profitability 盈利能力分析Analyzing working capital 营运资本分析Annual expenditure 年度支出Anticipating future income 预估未来收入Areas of financial ratios 财务比率分析的对象Articles of incorporation 合并条款Asian crisis 亚洲(金融)危机Assessing companies 企业评估Assessing country risk 国家风险评估Assessing credit risks 信用风险评估Assessing strategic power 战略地位评估Assessment of banks 银行的评估Asset conversion lending 资产转换贷款Asset protection lending 资产担保贷款Asset sale 资产出售Asset turnover 资产周转率Assets 资产Association of British Factors and Discounters 英国代理人与贴现商协会Auditor's report 审计报告Aval 物权担保Bad debt 坏账Bad debt level 坏账等级Bad debt risk 坏账风险Bad debts performance 坏账发生情况Bad loans 坏账Balance sheet 资产负债表Balance sheet structure 资产负债表结构Bank credit 银行信贷Bank failures 银行破产Bank loans.availability 银行贷款的可获得性Bank status reports 银行状况报告Bankruptcy 破产Bankruptcy code 破产法Bankruptcy petition 破产申请书Basle agreement 塞尔协议Basle Agreement 《巴塞尔协议》Behavioral scoring 行为评分Bill of exchange 汇票Bill of lading 提单BIS 国际清算银行BIS agreement 国际清算银行协定Blue chip 蓝筹股Bonds 债券Book receivables 账面应收账款Borrowing money 借人资金Borrowing proposition 借款申请Breakthrough products 创新产品Budgets 预算Building company profiles 勾画企业轮廓Bureaux (信用咨询)公司Business development loan 商业开发贷款Business failure 破产Business plan 经营计划Business risk 经营风险Buyer credits 买方信贷Buyer power 购买方力量Buyer risks 买方风险CAMPARI 优质贷款原则Canons of lending 贷款原则Capex 资本支出Capital adequacy 资本充足性Capital adequacy rules 资本充足性原则Capital commitments 资本承付款项Capital expenditure 资本支出Capital funding 资本融资Capital investment 资本投资Capital strength 资本实力Capital structure 资本结构Capitalization of interest 利息资本化Capitalizing development costs 研发费用资本化Capitalizing development expenditures 研发费用资本化Capitalizing interest costs 利息成本资本化Cascade effect 瀑布效应Cash assets 现金资产Cash collection targets 现金托收目标Cash cycle 现金循环周期Cash cycle ratios 现金循环周期比率Cash cycle times 现金循环周期时间Cash deposit 现金储蓄Cash flow adjustments 现金流调整Cash flow analysis 现金流量分析Cash flow crisis 现金流危机Cash flow cycle 现金流量周期Cash flow forecasts 现金流量预测Cash flow lending 现金流贷出Cash flow profile 现金流概况Cash flow projections 现金流预测Cash flow statements 现金流量表Cash flows 现金流量Cash position 现金头寸Cash positive JE现金流量Cash rich companies 现金充足的企业Cash surplus 现金盈余Cash tank 现金水槽Cash-in-advance 预付现金Categorized cash flow 现金流量分类CE 优质贷款原则CEO 首席执行官Chairman 董事长,总裁Chapter 11 rules 第十一章条款Charge 抵押Charged assets 抵押资产Chief executive officer 首席执行官Collateral security 抵押证券Collecting payments 收取付款Collection activity收款活动Collection cycle 收款环节Collection procedures 收款程序Collective credit risks 集合信用风险Comfortable liquidity positi9n 适当的流动性水平Commercial mortgage 商业抵押Commercial paper 商业票据Commission 佣金Commitment fees 承诺费Common stock 普通股Common stockholders 普通股股东Company and its industry 企业与所处行业Company assets 企业资产Company liabilities 企业负债Company loans 企业借款Competitive advantage 竞争优势Competitive forces 竞争力Competitive products 竞争产品Complaint procedures 申诉程序Computerized credit information 计算机化信用信息Computerized diaries 计算机化日志Confirmed letter of credit 承兑信用证Confirmed letters of credit 保兑信用证Confirming bank 确认银行Conservatism concept 谨慎原则Consistency concept 一贯性原则Consolidated accounts 合并报表Consolidated balance sheets 合并资产负债表Contingent liabilities 或有负债Continuing security clause 连续抵押条款Contractual payments 合同规定支出Control limits 控制限度Control of credit activities 信用活动控制Controlling credit 控制信贷Controlling credit risk 控制信用风险Corporate credit analysis 企业信用分析Corporate credit controller 企业信用控制人员Corporate credit risk analysis 企业信用风险分析Corporate customer 企业客户Corporate failure prediction models 企业破产预测模型Corporate lending 企业贷款Cost leadership 成本领先型Cost of sales 销售成本Costs 成本Country limit 国家限额Country risk 国家风险Court judgments 法院判决Covenant 贷款保证契约Covenants 保证契约Creative accounting 寻机性会计Credit analysis 信用分析Credit analysis of customers 客户信用分析Credit analysis of suppliers 供应商的信用分析Credit analysis on banks 银行信用分析Credit analysts 信用分析Credit assessment 信用评估Credit bureau reports 信用咨询公司报告Credit bureaux 信用机构Credit control 信贷控制Credit control activities 信贷控制活动Credit control performance reports 信贷控制绩效报告Credit controllers 信贷控制人员Credit cycle 信用循环Credit decisions 信贷决策Credit deterioration 信用恶化Credit exposure 信用敞口Credit granting process 授信程序Credit information 信用信息Credit information agency 信用信息机构Credit insurance 信贷保险Credit insurance advantages 信贷保险的优势Credit insurance brokers 信贷保险经纪人Credit insurance limitations 信贷保险的局限Credit limits 信贷限额Credit limits for currency blocs 货币集团国家信贷限额Credit limits for individual countries 国家信贷限额Credit management 信贷管理Credit managers 信贷经理Credit monitoring 信贷监控Credit notes 欠款单据Credit period 信用期Credit planning 信用计划Credit policy 信用政策Credit policy issues 信用政策发布Credit proposals 信用申请Credit protection 信贷保护Credit quality 信贷质量Credit rating 信用评级Credit rating agencies 信用评级机构Credit rating process 信用评级程序Credit rating system 信用评级系统Credit reference 信用咨询Credit reference agencies 信用评级机构Credit risk 信用风险Credit risk assessment 信用风险评估Credit risk exposure 信用风险敞口Credit risk insurance 信用风险保险Credit risk.individual customers 个体信用风险Credit risk:bank credit 信用风险:银行信用Credit risk:trade credit 信用风险:商业信用Credit scoring 信用风险评分Credit scoring model 信用评分模型Credit scoring system 信用评分系统Credit squeeze 信贷压缩Credit taken ratio 受信比率Credit terms 信贷条款Credit utilization reports 信贷利用报告Credit vetting 信用审查Credit watch 信用观察Credit worthiness 信誉Creditor days 应付账款天数Cross-default clause 交叉违约条款Currency risk 货币风险Current assets 流动资产Current debts 流动负债Current ratio requirement 流动比率要求Current ratios 流动比率Customer care 客户关注Customer credit ratings 客户信用评级Customer liaison 客户联络Customer risks 客户风险Cut-off scores 及格线Cycle of credit monitoring 信用监督循环Cyclical business 周期性行业Daily operating expenses 经营费用Day’s sales outstanding 收回应收账款的平均天数Debentures 债券Debt capital 债务资本Debt collection agency 债务托收机构Debt issuer 债券发行人Debt protection levels 债券保护级别Debt ratio 负债比率Debt securities 债券Debt service ratio 还债率Debtor days 应收账款天数Debtor's assets 债权人的资产Default 违约Deferred payments 延期付款Definition of leverage 财务杠杆率定义Deposit limits 储蓄限额Depositing money 储蓄资金Depreciation 折旧Depreciation policies 折旧政策Development budget 研发预算Differentiation 差别化Direct loss 直接损失Directors salaries 董事薪酬Discretionary cash flows 自决性现金流量Discretionary outflows 自决性现金流出Distribution costs 分销成本Dividend cover 股息保障倍数Dividend payout ratio 股息支付率Dividends 股利Documentary credit 跟单信用证DSO 应收账款的平均回收期Duration of credit risk 信用风险期Eastern bloc countries 东方集团国家EBITDA 扣除利息、税收、折旧和摊销之前的收益ECGD 出口信贷担保局Economic conditions 经济环境Economic cycles 经济周期Economic depression 经济萧条Economic growth 经济增长Economic risk 经济风险Electronic data interchange(EDI) 电子数据交换Environmental factors 环境因素Equity capital 权益资本Equity finance 权益融资Equity stake 股权EU countries 欧盟国家EU directives 欧盟法规EU law 欧盟法律Eurobonds 欧洲债券European parliament 欧洲议会European Union 欧盟Evergreen loan 常年贷款Exceptional item 例外项目Excessive capital commitments 过多的资本承付款项Exchange controls 外汇管制Exchange-control regulations 外汇管制条例Exhaust method 排空法Existing competitors 现有竞争对手Existing debt 未清偿债务Export credit agencies 出口信贷代理机构Export credit insurance 出口信贷保险Export factoring 出口代理Export sales 出口额Exports Credit Guarantee Department 出口信贷担保局Extending credit 信贷展期External agency 外部机构External assessment methods 外部评估方式External assessments 外部评估External information sources 外部信息来源Extraordinary items 非经常性项目Extras 附加条件Facility account 便利账户Factoring 代理Factoring debts 代理收账Factoring discounting 代理折扣Factors Chain International 国际代理连锁Failure prediction scores 财务恶化预测分值FASB (美国)财务会计准则委员会Faulty credit analysis 破产信用分析Fees 费用Finance,new business ventures 为新兴业务融资Finance,repay existing debt 为偿还现有债务融资Finance, working capital 为营运资金融资Financial assessment 财务评估Financial cash flows 融资性现金流量Financial collapse 财务危机。

信用经济下的信用评级机构

信用经济下的信用评级机构摘要正确引导信用评级机构的发展,对我国经济的腾飞具有重要作用。

关键词信用经济信用评级信用评级机构本土化监管私营征信机构信用评级机构(CRA)是伴随着信用经济的诞生而产生的,在现代经济的运行中起到了重大的作用。

但是,信用经济时代信息不对称的特点使得我们在判断一个经济体有无信用的问题上存在着很多难以解决的问题,因此现代意义上的评级机构就应运而生了。

信用评级机构的诞生在金融史上具有里程碑式的意义。

但是,在为投资者提供准确全面的信用评估的同时,信用评级机构也存在着严重的问题,制约着信用经济的发展,所以,正确引导信用评级机构的发展对我国经济的腾飞具有重要作用。

信用评级机构的作用:信用评级机构出现伊始就在经济运行中起了重要的作用。

世界的三大评级机构,美国标准普尔公司、穆迪投资服务公司、惠誉国际信用评级有限公司的评级成为了上市公司证券发行的通行证。

而同时在信用也迅速证券化,产生了相应的CDS等衍生工具,很大程度上促进了金融市场的发展,也极大地减少了由于利率提升等原因而导致的逆向选择,一定程度上降低了投资风险。

而在我国的经济社会情形下,由于金融市场的方兴未艾,诚信建设被摆到了越来越重要的位置上,成为了政策决策人和许多投资者以及金融机构关注的重点问题。

于是这样的信用评级机构的出现和发展能够极大的完善我国的金融体系,使得现代经济的运转更好的建立在信用这个重要的概念之上。

信用评级机构多以私人机构的组织形式出现。

它所提供的信息和评价成为市场主体对金融工具进行定价和确定利率水平的依据,也会直接作用于投资者的投资取向。

信用评级在一定程度上减少了投资者与发行者之间由于信息的不对称所带来的负面影响。

故而“信息”的准确度全面性是信用评级机构信誉的关键之所在。

信用评级机构存在的缺陷:但是近年来,信用评级机构越来越多的被经济学家所批评。

最主要的是评级机构已经和利益主体眼中挂钩,和被评公司的联系越来越密切,极大的影响了评级公司自身的信誉。

三大信用评级机构介绍

三大信用评级机构介绍摘要:标准普尔公司、穆迪投资者服务公司和惠誉国际信用评级公司为三大信用评级机构,三者评级均有长期和短期之分,但有不同的级别序列。

本文为大家简单的介绍一下三大信用评级机构简单常识性知识。

三大信用评级机构分别是标准普尔公司、穆迪投资者服务公司和惠誉国际信用评级公司。

三者评级均有长期和短期之分,但有不同的级别序列。

下面分别来介绍一下这三大信用评级机构。

标普评级——标准普尔公司标普的长期评级主要分为投资级和投机级两大类,投资级的评级具有信誉高和投资价值高的特点,投机级的评级则信用程度较低,违约风险逐级加大。

投资级包括AAA、AA、A和BBB,投机级则分为BB、B、CCC、CC、C和D。

信用级别由高到低排列,AAA级具有最高信用等级;D级最低,视为对条款的违约。

从AA至CCC级,每个级别都可通过添加"+"或"-"来显示信用高低程度。

例如,在AA序列中,信用级别由高到低依次为AA+、AA、AA-。

此外,标普还对信用评级给予展望,显示该机构对于未来(通常是6个月至两年)信用评级走势的评价。

决定评级展望的主要因素包括经济基本面的变化。

展望包括"正面"(评级可能被上调)、"负面"(评级可能被下调)、"稳定"(评级不变)、"观望"(评级可能被下调或上调)和"无意义"。

标普还会发布信用观察以显示其对评级短期走向的判断。

信用观察分为"正面"(评级可能被上调)、"负面"(评级可能被下调)和"观察"(评级可能被上调或下调)。

标普目前对126个国家和地区进行了主权信用评级。

美国失去AAA评级后,目前拥有AAA评级的国家和地区还有澳大利亚、奥地利、加拿大、丹麦、芬兰、法国、德国、中国香港特别行政区、马恩岛、列支敦士登、荷兰、新西兰、挪威、新加坡、瑞典、瑞士和英国。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

一、外文原文The Credit Rating Agencies: How Did We Get Here? Where Should We Go?Lawrence J. White*"…an insured state savings association…may not acquire or retain any corporate debt securities not of investment grade." 12 Code of Federal Regulations § 362.11 " …any user of the information contained herein should not rely on any credit rating or other opinion contained herein in making any investment decision." The usual disclaimer that is printed at the bottom of Standard & Poor’s credit ratings The U.S. subprime residential mortgage debacle of 2007-2008, and the world financial crisis that has followed, will surely be seen as a defining event for the U.S. economy -- and for much of the world economy as well -- for many decades in the future. Among the central players in that debacle were the three large U.S.-based credit rating agencies: Moody's, Standard & Poor's (S&P), and Fitch.These three agencies' initially favorable ratings were crucial for the successful sale of the bonds that were securitized from subprime residential mortgages and other debt obligations. The sale of these bonds, in turn, were an important underpinning for the U.S. housing boom of 1998-2006 -- with a self-reinforcing price-rise bubble. When house prices ceased rising in mid 2006 and then began to decline, the default rates on the mortgages underlying these bonds rose sharply, and those initial ratings proved to be excessively optimistic -- especially for the bonds that were based on mortgages that were originated in 2005 and 2006. The mortgage bonds collapsed, bringing down the U.S. financial system and many other countries’ financial systems as well.The role of the major rating agencies has received a considerable amount of attention in Congressional hearings and in the media. Less attention has been paid to the specifics of the financial regulatory structure that propelled these companies to the center of the U.S. bond markets –and that thereby virtually guaranteed that when they did make mistakes, those mistakes would have serious consequences for the financial sector. But an understanding of that structure is essential for any reasoned debate about the future course of public policy with respect to the rating agencies.This paper will begin by reviewing the role that credit rating agencies play in the bond markets. We then review the relevant history of the industry, including the crucial role that the regulation of other financial institutions has played in promoting the centrality of the major credit rating agencies with respect to bond information. In the discussion of this history, distinctions among types of financial regulation –especially between the prudential regulation of financial institutions (which, as we will see, required them to use the specific bond creditworthiness information that was provided by the major rating agencies) and the regulation of the rating agencies themselves –are important.We next offer an assessment of the role that regulation played in enhancing the importance of the three major rating agencies and their role in the subprime debacle. We then consider the possible prospective routes for public policy with respect to the creditrating industry. One route that has been widely discussed –and that is embodied in legislation that the Obama Administration proposed in July 2009 –would tighten the regulation of the rating agencies, in efforts to prevent the reoccurrence of those disastrous judgmental errors. A second route would reduce the required centrality of the rating agencies and thereby open up the bond information process in way that has not been possible since the 1930s.Why Credit Rating Agencies?A central concern of any lender -- including the lender/investors in bonds -- is whether a potential or actual borrower is likely to repay the loan. This is, of course, a standard problem of asymmetric information: The borrower is likely to know more about its repaying proclivities than is the lender. There are also standard solutions to the problem: Lenders usually spend considerable amounts of time and effort in gathering information about the likely creditworthiness of prospective borrowers (including their history of loan repayments and their current and prospective financial capabilities) and also in gathering information about the actions of borrowers after loans have been made.The credit rating agencies (arguably) help pierce the fog of asymmetric information by offering judgments -- they prefer the word "opinions"-- about the credit quality of bonds that are issued by corporations, governments (including U.S. state and local governments, as well as "sovereign" issuers abroad), and (most recently) mortgage securitizers. These judgments come in the form of “ratings”, which are usually a letter grade. The best known scale is that used by S&P and some other rating agencies: AAA, AA, A, BBB, BB, etc., with pluses and minuses as well.4Credit rating agencies are thus one potential source of such information for bond investors; but they are far from the only potential source. There are smaller financial services firms that offer advice to bond investors. Some bond mutual funds do their own research, as do some hedge funds. There are “fixed income analysts” at many financial services firms who offer recommendations to those firms’ clients with respect to bondinvestments.Although there appear to be well over 100 credit rating agencies worldwide,6 the three major U.S.-based agencies are clearly the dominant entities. All three operate on a worldwide basis, with offices on all six continents; each has ratings outstanding on tens of trillions of dollars of securities. Only Moody’s is a free-standing company, so the most information is known about Moody’s: Its 2008 annual report listed the company’s total revenues at $1.8 billion, its net revenues at $458 million, and its total assets at year-end at $1.8 billion.7 Slightly more than half (52%) of its total revenue came from the U.S.; as recently as 2006 that fraction was two-thirds. Over two-thirds (69%) of the company’s revenues comes from ratings; the rest comes from related services. At year-end 2008 the company had approximately 3,900 employees, with slightly more than half located in the U.S.Because S&P’s and Fitch’s ratings operations are components of larger enterprises (that report on a consolidated basis), comparable revenue and asset figures are not possible. But S&P is roughly the same size as Moody’s, while Fitch is somewhat smaller. Table 1 provides a set of roughly comparable data on each company’s analytical employees and numbers of issues rated. As can be seen, all three companies employ about the same numbers of analysts; however, Moody’s and S&P rate appreciably morecorporate and asset-backed securities than does Fitch.The history of the credit rating agencies and their interactions with financial regulators is crucial for an understanding of how the agencies attained their current central position in the market for bond information. It is to that history that we now turn. What Is to Be Done?In response to the growing criticism (in the media and in Congressional hearings) of the three large bond raters' errors in their initial, excessively optimistic ratings of the complex mortgage-related securities (especially for the securities that were issued and rated in 2005 and 2006) and their subsequent tardiness in downgrading those securities, the SEC in December 2008 promulgated NRSRO regulations that placed mild restrictions on the conflicts of interest that can arise under the rating agencies' "issuer pays" business model (e.g., requiring that the agencies not rate debt issues that they have helped structure, not allowing analysts to be involved in fee negotiations, etc.) and that required greater transparency (e.g., requiring that the rating agencies reveal details on their methodologies and assumptions and track records) in the construction of ratings.Political pressures to do more -- possibly even to ban legislatively the "issuer pays" model –have remained strong. In July 2009 the Obama Administration, as part of its larger package of proposed financial reforms, offered legislation that would require further, more stringent efforts on the part of the rating agencies to deal with the conflicts and enhance transparency.This regulatory response –the credit rating agencies made mist akes; let’s try to make sure that they don’t make such mistakes in the future –is understandable. But it ignores the history of the other kind of financial regulation – the prudential regulation of banks and other financial institutions -- that pushed the rating agencies into the center of the bond information process and that thereby greatly exacerbated the consequences for the bond markets when the rating agencies did make those mistakes. It also overlooks the stultifying consequences for innovation in the development and assessment ofinformation for judging the creditworthiness of bonds.Regulatory efforts to fix problems, by prescribing specified structures and processes, unavoidably restrict flexibility, raise costs, and discourage entry. Further, although efforts to increase transparency may help reduce problems of asymmetric information, they also have the potential for eroding a rating firm’s intellectual property and, over the longer run, discouraging the creation of future intellectual property.There is another, quite different direction in which public policy might proceed in the wake of the credit rating agencies’ mistakes. Rather than trying to fix them through regulation, it would provide a more markets-oriented approach that would likely reduce the importance of the incumbent rating agencies and thus reduce the importance (and consequences) of any future mistakes that they might make. This approach would call for the withdrawal of all of those delegations of safety judgments by financial regulators to the rating agencies. The rating agencies’ judgments would no longer have the force of law. Those financial regulators should persist in their goals of having safe bonds in the portfolios of their regulated institutions (or that, as in the case of insurance companies and broker-dealers, an institution's capital requirement would be geared to the risk ness of the bonds that it held); but those safety judgments should remain the responsibility of theregulated institutions themselves, with oversight by regulators.Under this alternative public policy approach, banks (and insurance companies, etc.) would have a far wider choice as to where and from whom they could seek advice as to the safety of bonds that they might hold in their portfolios. Some institutions might choose to do the necessary research on bonds themselves, or rely primarily on the information yielded by the credit default swap (CDS) market. Or they might turn to outside advisors that they considered to be reliable -- based on the track record of the advisor, the business model of the advisor (including the possibilities of conflicts of interest), the other activities of the advisor (which might pose potential conflicts), and anything else that the institution considered relevant. Such advisors might include the incumbent credit rating agencies. But the category of advisors might also expand to include the fixed income analysts at investment banks (if they could erect credible "Chinese walls") or industry analysts or upstart advisory firms that are currently unknown.The end-result -- the safety of the institution's bond portfolio -- would continue to be subject to review by the institution's regulator.That review might also include a review of the institution's choice of bond-information advisor (or the choice to do the research in-house) -- although that choice is (at best) a secondary matter, since the safety of the bond portfolio itself (regardless of where the information comes from) is the primary goal of the regulator. Nevertheless, it seems highly likely that the bond information market would be opened to new ideas -- about ratings business models, methodologies, and technologies -- and to new entry in ways that have not actually been possible since the 1930s.It is also worth asking whether, under this approach, the "issuer pays" business model could survive. The answer rests on whether bond buyers are able to ascertain which advisors do provide reliable advice (as does any model short of relying on government regulation to ensure accurate ratings). If the bond buyers can so ascertain,then they would be willing to pay higher prices (and thus accept lower interest yields) on the bonds of any given underlying quality that are "rated" by these reliable advisors. In turn, issuers -- even in an "issuer pays" framework -- would seek to hire these recognized-to-be-reliable advisers, since the issuers would thereby be able to pay lower interest rates on the bonds that they issue.That the "issuer pays" business model could survive in this counter-factual world is no guarantee that it would survive. That outcome would be determined by the competitive process.ConclusionWhither the credit rating industry and its regulation? The central role -- forced by seven decades of financial regulation -- that the three major credit rating agencies played in the subprime debacle has brought extensive public attention to the industry and its practices. The Securities and Exchange Commission has recently (in December 2008) taken modest steps to expand its regulation of the industry. The Obama Administration has proposed further efforts.There is, however, another direction in which public policy could proceed: Financial regulators could withdraw their delegation of safety judgments to the credit ratingagencies. The policy goal of safe bond portfolios for regulated financial institutions would remain. But the financial institutions would bear the burden of justifying the safety of their bond portfolios to their regulators. The bond information market would be opened to new ideas about rating methodologies, technologies, and business models and to new entry in ways that have not been possible since the 1930s.Those who are interested in this public policy debate should ask themselves the following questions: Is a regulatory system that delegates important safety judgments about bonds to third parties in the best interests of the regulated financial institutions and of the bond markets more generally? Will more extensive regulation of the rating agencies actually succeed in forcing the rating agencies to make better judgments in the future? Would such regulation have consequences for flexibility, innovation, and entry in the bond information market? Or instead, could the financial institutions be trusted to seek their own sources of information about the creditworthiness of bonds, so long as financial regulators oversee the safety of those bond portfolios?二、翻译文章信用评级机构:我们怎么会在这里?我们到哪去?劳伦斯 J 怀特美国联邦法规法典第362章11节12条指出:“…任何已投保的国家储蓄机构…不得取得或者保留任何公司债券投资级别的债券。