WordNet. An electronic lexical database.

WordNet和词向量相结合的句子检索方法

第18卷第4期2017年8月信息工程大学学报Journal of Information Engineering UniversityYol. 18 No. 4Aug. 2017DOI:10. 3969/j.is s n. 1671-0673.2017.04. 020WordNet和词向量相结合的句子检索方法刘欣\席耀一2,王波\魏晗1(1.信息工程大学,河南郑州450001&2解放军外国语学院,河南洛阳471000)摘要:针对当前句子检索方法中因数据稀疏而存在的“词不匹配”问题,提出了一种W o d N e t和词向量相结合的句子检索方法。

首先在W o d N e t语义关系图中应用个性化P a g e R a n k算法计算与查询项最相关的同义词集合,实现查询项扩展,从而在一定程度上解决了查询项数据稀疏的问题;然后利用在大规模语料中训练神经网络语言模型获取的词向量对查询项和句子进行表示;最后引入W M D% w o rd m o v e r's d is ta n c e&计算查询项与句子的语义相似度,从而利用语义信息进一步降低“词不匹配”问题带来的影响,将句子按相似度值从高到低排序作为句子检索结果。

文章方法在T R E C2003和T R E C2004会议的项目中进行评测,M A P和R-P r e c is io n值相较于次优结果分别提高了13.29%和13.54%。

关键词!W o r d N e t;查询项扩展;词向量;语义相似度;句子检索中图分类号:T P391. 1 文献标识码:A文章编号:1671-0673(2017)04-0486-06W ordNet and W ord Em bedding Based Sentence Retrieval MetliodLIU Xin1,XI Yaoyi2,WANG Bo1,WEI Han1(1. I n formation Engineering University,Zhengzhou 450002,China;2. PLA University of Foreign Language,Luoyang 471000,China )Abstract:A W o n iN e t an d W ood E m b e d d in g based sentence re trie v a l m e tlio d is p ro p o se d in th is p ap e r to solve th e v o c a b u la ry m is m a tc h p ro b le m roo te d in th e s p a rs ity o f sentences ly,w e ru n th e p e rs o n a liz e d P a g e R a n k a lg o rith m o v e r th e g ra p h re p re s e n ta tio n o f W o rd N e t co n ce ptsa nd re la tio n s to ob ta inc o n c e p ts re la ted to the q u e rie s,w h ic h c o u ld p a rtia lly se ttle th e s p aq u e rie s.S e c o n d ly,th e w o rd e m b e d d in g s th a t re p re s e n t s e m a n tics o f th e q u e ry a nd se n ten ce areg a in e d th ro u g h tra in in g in la rg e-s c a le c o rp u s w ith th e C o n tin o u s S k ip-gram M o d e l.F in a lly,thera n k e d lis t o f re trie v a l re s u lts is a c h ie v e d b y a p p ly in g W o rd M o v e r’s D is ta n c e(W M D)to c a lc u la tes e m a n tic s im ila rity o f q u e ry a n d s e n te n c e,w h ic h ca n fu r tiie r h a n d le th e v o c a b u la ry m is le m.T h e e v a lu a tio n on T R E C2003a n d T R E C2004re ve a ls th a t th e p ro p o se d m e th o d is s u p e rio r to th e b a s e lin e se n ten ce re trie v a l m e th o d.T h e M A P a n d R-P re c is io n are13. 29%a nd13.54%h ig h e r th a n th e second b e st r e s u lt.Key words:W o r d N e t;q u e ry e xp a n s io n;w o rd e m b e d d in g;s e m a n tic s im ila rity;sentence re trie v a l一般来说,句子检索是根据给定的查询主题从 多个文档中查找相关的句子,在自动问答(q u e s tio n a n s w e rin g,Q A)、文档摘要(s u m m a riz a tio n)、新话题检测(n o v e lty d e te c tio n)'和信息起源(in fo rm a tio n p ro v e n a n c e)等系统中,句子检索模块起着文本预处理作用,这些系统的性能与句子检索模块的性能收稿日期:2016-04-08;修回日期:2016-05-12基金项目:国家社会科学基金资助项目(14B X W028)作者筒介:刘欣(1990 -),男,硕士生,主要研究方向为自然语言处理,E-mail:syliuxinlyl@163. c o m 。

高中英语科技论文翻译单选题40题答案解析版

高中英语科技论文翻译单选题40题答案解析版1.The term “artificial intelligence” is often abbreviated as _____.A.AIB.IAC.AIID.IIA答案:A。

“artificial intelligence”的常见缩写是“AI”。

B 选项“IA”并非此词组的缩写。

C 和D 选项都是错误的组合。

2.In a scientific research paper, “data analysis” can be translated as _____.A.数据分析B.数据研究C.数据调查D.数据理论答案:A。

“data analysis”的正确翻译是“数据分析”。

B 选项“数据研究”应为“data research”。

C 选项“数据调查”是“data survey”。

D 选项“数据理论”是“data theory”。

3.The phrase “experimental results” is best translated as _____.A.实验结论B.实验数据C.实验结果D.实验过程答案:C。

“experimental results”的准确翻译是“实验结果”。

A 选项“实验结论”是“experimental conclusion”。

B 选项“实验数据”是“experimental data”。

D 选项“实验过程”是“experimental process”。

4.“Quantum mechanics” is translated as _____.A.量子物理B.量子力学C.量子化学D.量子技术答案:B。

“Quantum mechanics”是“量子力学”。

A 选项“量子物理”是“quantum physics”。

C 选项“量子化学”是“quantum chemistry”。

D 选项“量子技术”是“quantum technology”。

Lexicology

Lexicology (from lexiko-, in the Late Greek lexikon) is that partof linguistics which studies words, their nature and meaning, words' elements, relations between words (semantical relations), words groups and the whole lexicon.The term first appeared in the 1820s, though there were lexicologists in essence before the term wascoined. Computational lexicology as a related field (in the same way that computational linguistics is related to linguistics) deals with the computational study of dictionaries and their contents. An allied science to lexicology is lexicography, which also studies words in relation with dictionaries - it is actually concerned with the inclusion of words in dictionaries and from that perspective with the whole lexicon. Therefore lexicography is the theory and practice of composing dictionaries. Sometimes lexicography is considered to be a part or a branch of lexicology, but the two disciplines should not be mistaken:lexicographers are the people who write dictionaries, they are at the same time lexicologists too, but notall lexicologists are lexicographers. It is said that lexicography is the practical lexicology, it is practically oriented though it has its own theory, while the pure lexicology is mainly theoretical.[hide]1 Lexical semanticso 1.1 Domaino 1.2 History▪ 1.2.1 Prestructuralist semantics▪ 1.2.2 Structuralist and neostructuralist semantics▪ 1.2.3 Chomskyan school▪ 1.2.4 Cognitive semantics2 Phraseology3 Etymology4 Lexicographyo 4.1 Noted lexicographers5 Lexicologists6 Bibliography7 References8 See also9 External linkso9.1 Societieso9.2 Theory[edit]Lexical semanticsMain article: Semantics[edit]DomainSemantical relations between words are manifested in respectof homonymy, antonymy, paronymy, etc. Semantics usually involved in lexicological work is called lexical semantics. Lexical semantics is somewhat different from other linguistic types of semantics like phrase semantics, semantics of sentence, and text semantics, as they take the notion of meaning in much broader sense. There are outside (although sometimes related to) linguistics types of semantics like cultural semantics and computational semantics, as the latest is not relatedto computational lexicology but to mathematical logic. Among semantics of language, lexical semantics is most robust, and to some extend the phrase semantics too, while other types of linguistic semantics are new and not quite examined.[edit]HistoryLexical semantics may not be understood without a brief exploration of its history.[edit]Prestructuralist semanticsSemantics as a linguistic discipline has its beginning in the middle of the 19th century, and because linguistics at the time was predominantly diachronic, thus lexical semantics was diachronic too - it dominated the scene between the years of 1870 and 1930.[1] Diachronic lexical semantics was interested without a doubt in the change of meaning withpredominantly semasiological approach, taking the notion of meaning in a psychological aspect: lexical meanings were considered to be psychological entities), thoughts and ideas, and meaning changes are explained as resulting from psychological processes.[edit]Structuralist and neostructuralist semanticsWith the rise of new ideas after the ground break of Saussure's work, prestructuralist diachronic semantics was considerably criticized for the atomic study of words, the diachronic approach and the mingle of nonlinguistics spheres of investigation. The study became synchronic, concerned with semantic structures and narrowly linguistic.Semantic structural relations of lexical entities can be seen in three ways:▪semantic similarity▪lexical relations such as synonymy, antonymy, and hyponymy▪syntagmatic lexical relations were identifiedAs structuralist lexical semantics was revived by neostructuralist not much work was done by them, it is actually admitted by the followers.It may be seen that WordNet "is a type of an online electronic lexical database organized on relational principles, which now comprises nearly 100,000 concepts" as Dirk Geeraerts[2] states it. [edit]Chomskyan schoolMain article: Generative semanticsFollowers of Chomskyan generative approach to grammar soon investigated two different types of semantics, which, unfortunately, clashed in an effusive debate[3], these were interpretativeand generative semantics.[edit]Cognitive semanticsMain article: Cognitive semanticsCognitive lexical semantics is thought to be most productive of the current approaches.[edit]PhraseologyMain article: PhraseologyAnother branch of lexicology, together with lexicographyis phraseology. It studies compound meanings of two or more words, as in "raining cats and dogs". Because the whole meaning of that phrase is much different from the meaning of words included alone, phraseology examines how and why such meanings come in everyday use, and what possibly are the laws governing these word combinations. Phraseology also investigates idioms.[edit]EtymologyMain article: EtymologySince lexicology studies the meaning of words and their semantic relations, it often explores the origin and history of a word, i.e. its etymology. Etymologists analyse related languages using a technique known as the comparative method. In this way, word roots have been found that can be traced all the way back to the origin of, for instance, the Indo-European language family. However, the comparative method is unhelpful in the case of "multiplecausation"[4], when a word derives from several sources simultaneously as in phono-semantic matching.[5]Etymology can be helpful in clarifying some questionable meanings, spellings, etc., and is also used in lexicography. For example, etymological dictionaries provide words with their historical origins, change and development.[edit]LexicographyMain article: LexicographyA good example of lexicology at work, that everyone is familiar with, is that of dictionaries and thesaurus. Dictionaries are books or computer programs (or databases) that actually represent lexicographical work, they are opened and purposed for the use of public.As there are many different types of dictionaries, there are many different types of lexicographers.Questions that lexicographers are concerned with are for example the difficulties in defining what simple words such as 'the' mean, and how compound or complex words, or words with many meanings can be clearly explained. Also which words to keep in and which not to include in a dictionary.[edit]Noted lexicographersMain article: LexicographerSome noted lexicographers include:▪Dr. Samuel Johnson (September 18, 1709 – December 13, 1784)▪French lexicographer Pierre Larousse (October 23, 1817-January 3, 1875)▪Noah Webster (October 16, 1758 – May 28, 1843)▪Russian lexicographer Vladimir Dal (November 10, 1801 –September 22, 1872)[edit]Lexicologists▪Damaso Alonso, (Oct. 22, 1898-) Spanish literary critic and lexicologist▪Roland Barthes, (Nov. 12, 1915-Mar. 25, 1980) French writer, critic and lexicologist[edit]Bibliography▪Lexicology/Lexikologie: International Handbook on the Nature and Structure of Words and Vocabulary/EinInternationales Handbuch Zur Natur and Struktur Von Wortern Und Wortschatzen, Vol 1. & Vol 2. (Eds. A. Cruse et al.)▪Words, Meaning, and Vocabulary: An Introduction to Modern English Lexicology, (ed. H. Jackson); ISBN 0-304-70396-6▪Toward a Functional Lexicology, (ed. G. Wotjak); ISBN 0-8204-3526-0▪Lexicology, Semantics, and Lexicography, (ed. J.Coleman); ISBN 1-55619-972-4▪English Lexicology: Lexical Structure, Word Semantics & Word-formation,(Leonhard Lipka.); ISBN 9783823349952▪Outline of English Lexicology , (Leonhard Lipka.); ISBN 3484410035[edit]References1. ^ Dirk Geeraerts, The theoretical and descriptivedevelopment of lexical semantics, Prestructuralist semantics, Published in: The Lexicon in Focus. Competition andConvergence in Current Lexicology, ed. Leila Behrens andDietmar Zaefferer, p. 23-422. ^ Dirk Geeraerts, The theoretical and descriptivedevelopment of lexical semantics, Structuralist andneostructuralist semantics, Published in: The Lexicon inFocus. Competition and Convergence in Current Lexicology, ed. Leila Behrens and Dietmar Zaefferer, p. 23-423. ^ Harris, Randy Allen (1993) The Linguistics Wars, Oxford,New York: Oxford University Press4. ^ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2009), Hybridity versusRevivability: Multiple Causation, Forms andPatterns, Journal of Language Contact, Varia 2: 40-67.5. ^ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003), ‘‘Language Contact andLexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew’’, Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, (Palgrave Studies in Language History andLanguage Change, Series editor: Charles Jones). ISBN1-4039-1723-X.。

郑大远程教育《信息检索03》答案

A B

C D 、《全国报刊索引》是

A B

C D 、《中国博士学位论文提要》是

A B

C D 、实用型专利的有效期,我国自申请日算起是

A B

C D 、下列专利说明书编号中表示实用型专利的是

A B

C D

A、分类途径

B、主题途径

C、著者工作单位途径

D、著者途径

3、《中国专利索引》的检索途径有( )

A、分类途径

B、专利权人途径

C、主题途径

D、专利序号途径

4、我国专利法规定,一件发明创造要获得专利权必须应当具有( )

A、新颖性

B、规范性

C、实用性

D、创造性

5、我国标准按其适用范围分为( )

A、国家标准

B、行业标准

C、地方标准

D、企业标准

第三题、判断题(每题1分,5道题共5分)

1、《全国报刊索引》是一种综合性检索工具。

正确错误2、《国外科技文献检索工具简介》是一种文献指南。

正确错误3、在专利有效期内,别人未经专利权人许可,不得随意使用该项专利。

正确错误、实用型专利的有效期,我国是自申请日算起

正确错误、对产品的形状所提出的新的技术方案属于发明专利。

正确错误。

WORD ASSOCIATION NORMS, ] IUTUAL INFORMATION, AND LEXICOGRAPHY

![WORD ASSOCIATION NORMS, ] IUTUAL INFORMATION, AND LEXICOGRAPHY](https://img.taocdn.com/s3/m/6d7535240722192e4536f663.png)

The term word association is used in a very particular sense in the psycholinguistic literature. (Generally speaking, subjects respond quicker than normal to the word nurse if it follows a highly associated word such as doctor.) We will extend the term to provide the basis for a statistical description of a variety of interesting linguistic phenomena, ranging from semantic relations of the doctor/nurse type (content word/content word) to lexico-syntactic co-occurrence constraints between verbs and prepositions (content word/function word). This paper will propose an objective measure based on the information theoretic notion of mutual information, for estimating word association norms from computer readable corpora. (The standard method of obtaining word association norms, testing a few thousand :mbjects on a few hundred words, is both costly and unreliable.) The proposed measure, the association ratio, estimates word association norms directly from computer readable corpora, making it possible to estimate norms for tens of thousands of words.

江南大学上半信息检索与利用第1阶段练习题题目

江南大学现代远程教育第一阶段练习题考试科目:《信息检索与利用》第1章至第3章(总分100分)学习中心(教学点)批次:层次:专业:学号:身份证号:姓名:得分:一、单项选择题(每题2分,共20分)1、经过人类加工、有使用价值或者潜在使用价值的信息称为()。

A、知识B、文献C、情报D、信息资源2、以下资源中()不是三次信息资源。

A、百科全书B、索引C、手册D、指南3、《中国图书馆分类法》分为五大部类,在此基础上扩展为()大类。

A、25B、10C、22D、164、期刊的国际标准连续出版物号简称()。

A、ISSNB、ISDSC、ISOD、ISBN5、Google检索框中输入多个词,词与词之间用空格隔开表示()关系。

A、逻辑或B、逻辑非C、逻辑与D、短语或词组6、短语或词组检索常用运算符为( )。

A、()B、*C、?D、“”7、目录与题录的主要不同点在于( )不同。

A、著录对象B、著录方法C、著录格式D、著录载体8、用百度(Baidu)搜索“能源”但排除“核能”方面的信息,使用检索式()。

A、能源|核能B、能源 -核能C、能源+核能D、能源核能9、()服务主要通过复制、拷贝、扫描原文,然后采用邮寄、传真、e-mail等方式将文献传递到用户。

A、资源共享B、文献递传C、OPACD、一站式检索10、( )是指检出的相关文献量与检索系统中相关文献总量的百分比。

A、查准率B、漏检率C、查全率D、误检率二、多项选择题(每题2分,共20分)1、信息资源从信息载体的角度可分为()。

A、纸质信息资源B、缩微型信息资源C、声像型信息资源D、电子信息资源2、以下文献中()是特种文献。

A、科技报告B、产品样本C、会议录D、丛书3、以下信息资源中()不是二次信息资源。

A、目录B、述评C、教材D、索引4、检索方法一般包括()方法。

A、工具法B、引文法C、主题法D、循环法5、以下搜索引擎中()是全文搜索引擎。

A、百度(Baidu)B、GoogleC、Yahoo!D、InfoSpace6、影响用户查全率的因素有( )。

2007试卷(B)答案

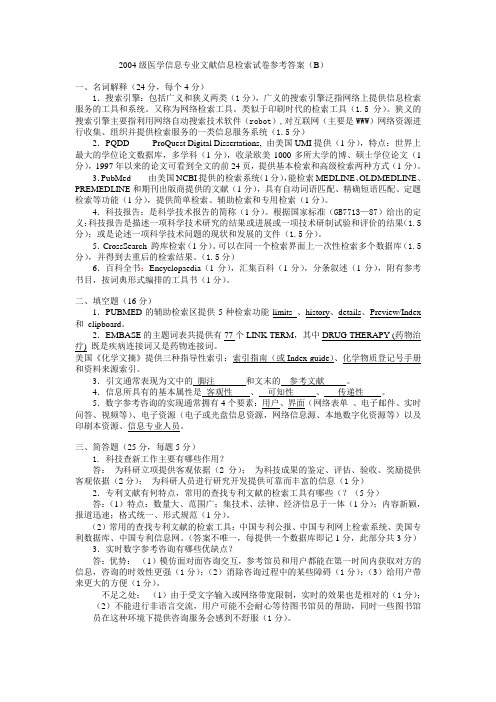

2004级医学信息专业文献信息检索试卷参考答案(B)一、名词解释(24分,每个4分)1.搜索引擎:包括广义和狭义两类(1分),广义的搜索引擎泛指网络上提供信息检索服务的工具和系统。

又称为网络检索工具。

类似于印刷时代的检索工具(1.5分)。

狭义的搜索引擎主要指利用网络自动搜索技术软件(robot),对互联网(主要是WWW)网络资源进行收集、组织并提供检索服务的一类信息服务系统(1.5分)2.PQDD--------ProQuest Digital Dissertations, 由美国UMI提供(1分),特点:世界上最大的学位论文数据库,多学科(1分),收录欧美1000多所大学的博、硕士学位论文(1分),1997年以来的论文可看到全文的前24页,提供基本检索和高级检索两种方式(1分)。

3.PubMed------由美国NCBI提供的检索系统(1分),能检索MEDLINE、OLDMEDLINE、PREMEDLINE和期刊出版商提供的文献(1分),具有自动词语匹配、精确短语匹配、定题检索等功能(1分),提供简单检索、辅助检索和专用检索(1分)。

4.科技报告:是科学技术报告的简称(1分)。

根据国家标准(GB7713—87)给出的定义:科技报告是描述一项科学技术研究的结果或进展或一项技术研制试验和评价的结果(1.5分);或是论述一项科学技术问题的现状和发展的文件(1.5分)。

5.CrossSearch 跨库检索(1分)。

可以在同一个检索界面上一次性检索多个数据库(1.5分),并得到去重后的检索结果。

(1.5分)6.百科全书:Encyclopaedia(1分),汇集百科(1分),分条叙述(1分),附有参考书目,按词典形式编排的工具书(1分)。

二、填空题(16分)1.PUBMED的辅助检索区提供5种检索功能limits 、history、details、Preview/Index 和clipboard。

2.EMBASE的主题词表共提供有77个LINK TERM,其中DRUG THERAPY (药物治疗) 既是疾病连接词又是药物连接词。

浙江省诸暨中学2017-2018学年高一上学期第二阶段考信息技术试卷(含答案)(2018.01)

诸暨中学2017-2018学年上期第二次阶段性考试高一信息技术2018.01(说明:本试卷全部试题均答在答题纸上)一、选择题(本大题共9小题,共18分)1.下列关于信息和信息技术的说法,正确的是()A.书本不是信息,但文字属于信息B.信息具有载体依附性,但也有少部分信息不具备载体C.信息和物质、能源最大的不同在于它具有共享性D.由于电子计算机是近代才出现的,因此古代没有信息技术2.小王用IE浏览器打开“百度”主页,下列说法不正确的是()A.该网页采用文件传输协议ftp协议来发送和接收信息B.网页文件遵循HTML语言标准,可以用记事本打开并编辑C.如果只需保存网页中的文字信息,可以选择的保存类型为“文本(*.txt)”D.收藏该网站就是保存百度主页的地址“”3.下列描述属于人工智能应用范畴的是()A.地铁站使用X光机对旅客行李进行安检扫描B.地图软件在有wifi连接的地方自动升级数据C.高速公路ETC通道自动识别车牌号码进行收费D.医生使用B超探测病人身体4.下图所示为在UltraEdit软件中观察字符内码的部分界面:以下说法正确的是()A.存储字符“℃”需要1ByteB.气温之后的冒号(:)采用ASCII表示C.字符“38”的内码用二进制表示为00111000D.符号(~)的内码用十六进制表示为A1AB5.下图所示是ACCESS数据库中的数据表,以下说法正确的是()A.当前状态下执行“新记录(W)”命令,则新添加的记录位于第3行位置B.当前为数据视图,无法修改“性别”字段名称C.某字段数据类型若为“自动编号”,则新值不一定是递增的D.该数据库的名称为student.accdb6.使用Word软件编辑某文档,部分界面如图所示,下列说法正确的是()A.文档中图片的文字环绕方式为“嵌入型”B.用户t1和用户s2添加了批注C.文章中共有两处修订,两处批注D.拒绝所有修订后,开头的文字是“记者从今天浙江省政府新闻信息办召开的…”7.使用GoldWave软件打开某音频文件,其编辑界面如图所示:下列说法不正确...的是()A.该音频的采样频率为44.1KHz,比特率为1411kbpsB.如果插入10秒“静音”,以当前参数保存,音频文件容量将增加1/6C.当前状态下执行“剪裁”操作,以当前参数保存,文件存储容量不变D.当前状态下执行“删除”操作,以当前参数保存,文件存储容量约为8MB8.某未经压缩的图像文件和视频文件相关信息分别如下图所示:由此可知图像文件与视频文件的存储容量比例约为()A.9:15B.1:25C.9:25D.18:259.有一个魔方共有6种不同的颜色,对魔方的任意一面进行二进制编码,至少需要多少位二进制()A.54 B.36 C.27 B.18二、非选择题(本大题共4小题,其中第1小题6分,第2小题5分,第15小题8分,第16小题6分,第3小题8分,第4小题12分,共32分)1、小王收集了2017年5月美国SUV销量排行榜数据,并用Excel进行数据处理,如图所示。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

WordNet. An electronic lexical database. Edited by Christiane Fellbaum, with a preface by George Miller. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. 422 p. $50.00This is a landmark book. For anyone interested in language, in dictionaries and thesauri, or natural language processing, the introduction, Chapters 1- 4, and Chapter 16 are must reading. (Select other chapters according to your special interests; see the chapter-by-chapter review). These chapters provide a thorough introduction to the preeminent electronic lexical database of today in terms of accessibility and usage in a wide range of applications. But what does that have to do with digital libraries? Natural language processing is essential for dealing efficiently with the large quantities of text now available online: fact extraction and summarization, automated indexing and text categorization, and machine translation. Another essential function is helping the user with query formulation through synonym relationships between words and hierarchical and other relationships between concepts. WordNet supports both of these functions and thus deserves careful study by the digital library community.The introduction and part I, which take almost a third of the book, give a very clear and very readable overview of the content, structure, and implementation of WordNet, of what is in WordNet and what is not; these chapters are meant to replace Five papers on WordNet(ftp:///pub/WordNet/5papers.ps), which by now are partially outdated. However, I did not throw out my copy of the Five papers; they give more detail and interesting discussions not found in the book. Chapter 16 provides a very useful complement; it includes a very good overview of WordNet relations (with examples and statistics) and describes possible extensions of content and structure.Part II, about 15% of the book, describes "extensions, enhancements, and new perspectives on WordNet", with chapters on the automatic discovery of lexical and semantic relations through analysis of text, on the inclusion of information on the syntactic patterns in which verbs occur, and on formal mathematical analysis of the WordNet structure.Part III, about half the book, deals with representative applications of WordNet, from creating a "semantic concordance" (a text corpus in which words are tagged with their proper sense), to automated word sense disambiguation, to information retrieval, to conceptual modeling. These are good examples of pure knowledge-based approaches and of approaches where statistical processing is informed by knowledge from WordNet.As one might expect, the papers in this collection (which are reviewed individually below), are of varying quality; Chapters 5, 12, and 16 stand out. Many of the authors pay insufficient heed to the simple principle that the reader needs to understand the overall purpose of work being discussed in order to best assimilate the detail. Repeatedly, one finds small differences in performance discussed as if they meant something, when it is clear that they are not statistically significant (or at least it is not shown that they are), a problem that afflicts much of information retrieval and related research. The application papers demonstrate the many uses of WordNet but also make a number of suggestions for expanding the types of information included in WordNet to make it even more useful. They also uncover weaknesses in the content of WordNet by tracing performance problems to their ultimate causes.The papers are tied together into a coherent whole, and that unity of the book is further enhanced by the presence of an index, which is often missing from such collections. One would wish the index a bit more detailed.. The reader wishing for a comprehensive bibliography on WordNet can find it at /~josephr/wn-biblio.html (and more information on WordNet can be found at /~wn).The book deals with WordNet 1.5, while WordNet 1.6 was released at just about the same time. For the papers on applications it could not be otherwise, but the chapters describing WordNet might have been updated to include the 1.6 enhancements. One would have wished for a chapter or at least a prominent mention of EuroWordNet (www.let.uva.nl/~ewn), a multilingual lexical database using WordNet's concept hierarchy.It would have been useful to enforce common use at least of key terms throughout the papers; for example, the introduction says "WordNet makes the commonly accepted distinction between conceptual-semantic relations, which link concepts, and lexical relations, which link individual words [emphasis added], yet in Chapter 1 George Miller states that "the basic semantic relation in WordNet is synonymy" [emphasis added] and in Chapter 5 Marti Hearst uses the term lexical relationships to refer to both semantic relationships and lexical relationships. Priss (p. 186) confuses the issue further in the following statements: "Semantic relations, such as meronymy, synonymy, and hyponymy, are according to WordNet terminology relations that are defined among synsets. They are distinguished from lexical relations, such as antonymy, which are defined among words and not among synsets." [Emphasis added]. Synonymy is, of course, a lexical relation, and terminology relations are relations between words or between words and concepts, but not relations between concepts.This terminological confusion is indicative of a deeper problem. The authors of WordNet vacillate somewhat between a position that stays entirely in the plane of words and deals with conceptual relationships in terms of the relationships between words, and the position, commonly adopted in information science, of separating the conceptual plane from the terminological plane.What follows is a chapter-by-chapter review. By necessity, this often gets into a discussion how things are done in WordNet, rather than just staying with the quality of the description per se.Part I. The lexical database (p. 1 - 127)George Miller's preface is well worth reading for its account of the history and background of WordNet. It also illustrates the lack of communication between fields concerned with language: Thesaurus makers could learn much from WordNet, and WordNet could learn much from thesaurus-makers. The introduction gives a concise overview of WordNet and a preview of the book. It might still make clear more explicitly the structure of WordNet: The smallest unit is the word/sense pair identified by a sense key (p. 107); word/sense pairs are linked through WordNet's basic relation, synonymy, which is expressed by grouping word/sense pairs into synonym sets or synsets; each synset represents a concept, which is often explained through a brief gloss (definition). Put differently, WordNet includes the relationship word W designates concept C, which is coded implicitly by including W in the synset for C. (This is made explicitin Table 16.1.) Two words are synonyms if they have a designates relationship to the same concept. Synsets (concepts) are the basic building blocks for hierarchies and other conceptual structures in WordNet.The following three chapters each deal with a type of word. In Chapter 1, Nouns in WordNet, George Miller presents a cogent discussion of the relations between nouns: synonymy, a lexical relation, and hyponymy (has narrower concept) and meronymy (has part), semantic relations. Hyponymy gives rise to the WordNet hierarchy. Unfortunately, it is not easy to get well-designed display of that hierarchy. Meronymy (has part) / holonymy (is part of) always are subject to confusion, not completely avoided in this chapter, which stems from ignoring the fact that airplane has-part wing really means "an individual object 1 which belongs to the class airplane has-part individual object 2 which belongs to the class wing". While it is true that bird has-part wing, it is by no means the same wing or even the same type of wing. Thus the strength of a relationship established indirectly between two concepts due to a has-part relationship to the same concept may vary widely. Miller sees meronymy and hyponymy as structurally similar, both going down. But it is equally reasonable to consider a wing as something more general than an airplane and thus construe the has-part relationship s going up, as is done in Chapter 13. Chapter 2, Modifiers in WordNet by Katherine J. Miller describes how adjectives and adverbs are handled in WordNet. It is claimed that nothing like hyponymy/hypernymy is available for adjectives. However, especially for information retrieval purposes, the following definition makes sense: Adj A has narrower term (NT) Adj B if A applies whenever B applies and A and B are not synonyms (the scope of A includes the scope of B and more). For example, red NT ruby (and conversely, ruby BT red) or large NT huge. To the extent that WordNet includes specific color values, their hierarchy is expressed only for the noun form of the color names. Hierarchical relationships between adjectives are expressed as similarity. The treatment of antonymy is somewhat tortured to take account of the fact that large vs small and big vs. little are antonym pairs, but *large vs. little or *prompt vs. slow are not. In general, when speakers express semantic opposition, they do not use just any term for each of the opposite concepts, but they apply lexical selection rules. The simplest way to deal with this problem is to establish an explicit semantic relationship of opposition between concepts and separately record antonymy as a lexical relationship between words (in their appropriate senses). Participial adjectives are maintained in a separate file and have a pointer to the verb unless they fit easily into the cluster structure of descriptive adjectives "rather than" having a pointer to the verb. Why a participial adjective in the cluster structure cannot also have a pointer to the verb is not explained.In Chapter 3, A semantic network of English verbs, Christiane Fellbaum presents a carefully reasoned analysis of the semantic relations between verbs (as presented in WordNet and as presented in alternate approaches) and of the other information for verbs, especially sentence structures, given in WordNet. Much of this discussion is based on results from psycholinguistics. The relationships between verbs are all forms of a broadly defined entailment relationship: troponymy establishes a verb hierarchy (verb A has the troponym verb B if B is a particular way of doing A, corresponding to hyponymy between nouns; the reverse relation is verb B has hypernym verb A); entailment in a more specific sense (to snore entails to sleep); cause; and backward presupposition (one must know before one can forget, not given inWordNet). More refined relationship types could be defined but are not for WordNet, since they do not seem to be psychologically salient and would complicate the interface. The last is not a good reason, since detailed relationship types could be coded internally and mapped to a more general set to keep the interface simple; the additional information would be useful for specific applications. In Section 3.3.1.3 on basic level categories in verbs, the level numbers are garbled (talk is both level L+1 and level L), making the argument unclear.In Chapter 4, Design and implementation of the WordNet lexical database and searching software, Randee I. Tengi lays out the technical issues. While it is hard to argue with a successful system, one might observe that this is not the most user-friendly system this reviewer has seen. The lexicographers have to memorize a set of special characters that encode relationship types (for example, ~ for hyponym, @ for hypernym); {apple, edible_fruit, @} means: apple has the hypernym edible_fruit. The interface is on a par with most online thesaurus interfaces, that is to say, poor. In particular, one cannot see a simple outline of the concept hierarchy; for many thesauri that is available in printed form. P. 108 says that "many relations being reflexive", when it should say reciprocal (such as hyponym / hypernym); a reflexive relation has a precise definition in mathematics (for all a, a R a holds).Chapter 16, Knowledge processing on an extended WordNet by Sanda M. Harabagiu and Dan I. Moldovan is discussed here because it should be read here. Table 16.1 gives the best overview of the relations in WordNet, with a formal specification of the entities linked, examples, properties (symmetry, transitivity, reverse of), and statistics. Table 16.2 gives further types of relationships that can be derived from the glosses (definitions) provided in WordNet. Still further relationships can be derived by inferences on relationship chains. The application of this extended WordNet to knowledge processing (for example, marker propagation, testing a text for coherence) is less well explained.Part II. Extensions, enhancements, and new perspectives on WordNet p. 129 - 196Chapter 5, Automated discovery of WordNet relations, by Marti A. Hearst is a well-written account of using Lexico-Syntactic Pattern Extraction (LSPE) to mine text for hyponym relationships. This is important to reduce the enormous workload in the strictly intellectual compilation of the large lexical databases needed for NLP and retrieval tasks. The following examples illustrate two sample patterns (the implied hyponym relationships should be obvious):red algae, such as Gelidiumbruises, broken bones, or other injuriesPatterns can be hand-coded and/or identified automatically. The results presented are promising. In the discussion of Automatic acquisition from corpora (p. 146, under Related work), only fairly recent work from computational linguistics is cited. Resnik, in Chapter 10, cites work back to 1957. There is also early work done in the context of information retrieval, for example, Giuliano 1965; for more references on early work see Soergel 1974, Chapter H.Chapter 6, Representing verb alternations in WordNet, by Karen T. Kohl, Douglas A. Jones, Robert C. Berwick, and Naoyuki Nomura discusses a format for representing syntactic patterns of verbs in WordNet. It is clearly written for linguists and a heavy read for others. It is best to look at the appendix first to get an idea of the ultimate purpose.Chapter 7, The formalization of WordNet by methods of relational concept analysis, by Uta E. Priss is somewhat of an overkill in formalization. Formal concept analysis might be a useful method, but the starkly abbreviated presentation given here is not enough to really understand it. The paper does reveal a proper analysis of meronymy, once one penetrates the formalism and the notation. The WordNet problems identified on p. 191-195 are quite obvious to the experienced thesaurus builder once the hierarchy is presented in a clear format and could in any event be detected automatically based on simple componential analysis.Part III Applications of WordNet. p. 197-406Chapters 8 Building semantic concordances, by Shari Landes, Claudia Leacock, and Randee I. Tengi and Chapter 9, Performance and confidence in a semantic annotation task, by Christiane Fellbaum, Joachim Grabowski, and Shari Landes both deal with manually tagging each word in a corpus (in the example, 103 passages from the Brown corpus and the complete text of Crane's The red badge of courage) with the appropriate WordNet sense. This is useful for many purposes: detecting new senses, obtaining statistics on sense occurrence, testing the effectiveness of correct disambiguation for retrieval or clustering of documents, and training disambiguation algorithms. The tagged corpus is available with WordNet.Chapter 10, WordNet and class-based probabilities, by Philip Resnik, presents an interesting and discerning discourse on "how does one work with corpus-based statistical methods in the context of a taxonomy?" or, put differently, how does one exploit the knowledge inherent in a taxonomy to make statistical approaches to language analysis and processing (including retrieval) more effective. However, the real usefulness of the statistical approach does not appear clearly until Section 10.3, where the approach is applied to the study of selectional preferences of verbs (another example of mining semantic and lexical information from text), and thus the reader lacks the motivation to understand the sophisticated statistical modeling. The reader deeply interested in these matters might prefer to turn to the fuller version in Resnik's thesis (access from /~Resnik),Chapters 11, Combining local context and WordNet similarity for word sense identification, by Claudia Leacok and Martin Chodorov and 13, Lexical chains as representations of context for the detection and correction of malapropisms, by Graeme Hirst and David St-Onge present methods for sense disambiguation. Chapter 11 uses a statistical approach, computing from a sense-tagged corpus (the training corpus) three distributions that measure the associations of a word in a given sense with part-of-speech tags, open-class words, and closed-class words. These distributions are then used to predict the sense of a word in arbitrary text. The key idea of the paper is very close to the basic idea of Chapter 10: exploit knowledge to improve statistical methods, in this case use knowledge on word sense similarity gleaned from WordNet to extend the usefulness of the training corpus by using the distributions for a sense A1 of word A todisambiguate word B, one of whose senses is similar to A1. Results of experiments are inconclusive (they lack statistical significance), but he idea seems definitely worth pursuing. Hirst and St-Onge take an entirely different approach. Using semantic relations from WordNet they build what they call lexical chains (semantic chain would be a better term) of words that occur in the text. Initially there are many competing chains, corresponding to different senses of the words occurring in the text, but eventually some chains grow long and others do not, and the word senses in the long chains are selected. (Instead of chains one might use semantic networks.) Various patterns of direct and indirect relationships are defined as allowable chain links, and each pattern has a given strength. In the paper, this method is used to detect and correct malapropisms, defined here as misspellings that are valid words (and therefore not detected by a spell checker), for example, “Much of the data is available toady electronically” or “Lexical relations very in number within the text”. (Incidentally, this sense of malapropism is not found in standard dictionaries, including WordNet; in a book on WordNet, one should use language carefully.) The problem of detecting misspellings that are themselves words is the same as the homonym problem: If one accepts, for example, both today and toady as variations of the word today and of the word toady, then [today. toady] becomes a homonym having all the senses of the two words that are misspellings of each other; that is to say, the occurrence of either word in the text may indicate any of the senses of both words. Finding the sense that fits the context selects the form correctly associated with that sense. This is an ingenious application of sense disambiguation methods to spell checking.Chapter 14, Temporal indexing through lexical chaining, by Reem Al-Halimi and Rick Kazman uses a very similar approach to indexing text, an idea that seems quite good (as opposed to the writing). The texts in question are transcripts from video conferences, but that is tangential and their temporal nature is not considered in the paper. Instead of chains they build lexical trees (again, semantic tree would be a better name, and why not use more general semantic networks).A text is represented by one or more trees (presumably each tree representing a logical unit of the text). Retrieval then is based on these trees as target objects. A key point in this method, not stressed in the paper, is the word sense disambiguation that comes about in building the semantic trees. The method appears promising, but no retrieval test results are reported.In Chapter 12, Using WordNet for text retrieval, Ellen M. Voorhees reports on retrieval experiments using WordNet for query term expansion and word sense disambiguation. No conclusions as to the usefulness of these methods should be drawn from the results. The algorithms for query term expansion and for word sense disambiguation performed poorly —partially due to problems in the algorithms themselves, partially due to problems in WordNet —so it is not surprising that retrieval results were poor. Later work on improved algorithms, including work by Voorhees, is cited.In Chapter 15, COLOR-X: Using knowledge from WordNet for conceptual modeling [in software engineering], J. F. M. Burg and R. P. van de Riet describe the use of WordNet to clarify word senses in software requirement documents and for detecting semantic relationships between entity types and relationship types in an E-R model. The case they make is not very convincing. They also bring the art of making acronym soup to new heights, misleading the reader in the process (the chapter has nothing to do with colors).All in all, this is a useful collection of papers and a rich source of ideas.ReferencesGiuliano, Vincent E. 1965 The interpretation of word associations. In Stevens, Mary E.; Giuliano, Vincent E.; Heilprin, Lawrence B., eds. Statistical association methods for mechanical documentation. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1965 December. 261 p. (National Bureau of Standards Miscellaneous Publication 269)Soergel, Dagobert. 1974. Indexing languages and thesauri: Construction and maintenance. Los Angeles, CA: Melville; 1974. 632 p., 72 fig., ca 850 ref. (Wiley Information Science Series)。