市场微结构Market Microstructure

拾穗多因子系列(20):市场微观结构研究:如何度量股市流动性?

拾穗多因子系列(20):市场微观结构研究:如何度量股市流动性?投资要点►引言该如何度量股市流动性?美国股票市场发生了“流动性危机”吗?A股市场的流动性情况如何?本期“拾穗”专题,我们从微观市场结构的研究视角出发,介绍几种度量市场流动性的指标,并对中美两市近期的流动性情况进行比较,以供投资者参考。

►“流动性是市场的一切”市场微观结构理论是研究交易价格的形成与发现过程与交易运作机制的一个金融分支,市场结构的研究主要包括流动性、透明性、有效性、稳定性、公平性、可靠性,而其中“流动性是市场的一切”。

流动性是在一定时间内完成交易所需的时间或成本,概括起来流动性包含速度(交易时间)、价格(交易成本)、交易数量和弹性四个方面。

►股市流动性度量指标介绍从市场流动性冲击出发,对Amihud非流动性指标、PastorGamma指标、LOT Zeros方法进行介绍。

从股票买卖价格出发,对采用日内高频交易数据构建的有效价差指标和采用日度低频价量指标的Roll价差,Corwin and Schultz指标进行介绍。

►实证检验通过对美股市场的整体流动性进行监测发现,近期美股市场的流动性冲击达到一个高峰,部分指标甚至高过2008年金融危机时刻。

近期美股市场确实承受了较大的卖压,由于投资者的恐慌性抛售导致的市场信心不足从多个流动性指标维度得到了验证。

相较之下,A股市场受近期全球波动影响虽然也出现了一定的波动放大情况,但总体而言A股市场流动性情况比较良好,并没有出现股市流动性紧张的情况。

►风险提示本报告统计结果基于历史数据,过去数据不代表未来,市场风格变化可能导致模型失效。

►更多交流,欢迎联系张宇,联系方式:176****8421(注明机构+姓名)欢迎在Wind研报平台中搜索关键字“星火“和”拾穗”,下载阅读专题报告的PDF版本。

本期是该系列报告的第20期,随着新冠疫情在全球范围内的扩散以及OPEC与俄罗斯之间的石油冲突爆发,近期外围市场出现了剧烈的波动,其中以美国市场的波动最为明显。

procast-初级教程

ProCAST软件综合培训教程 CopyRight cax2001@ ProCAST 3.20 简体中文基础应用教程版权所有:软件猎手cax2001@第一章 软件及基本操作介绍ProCAST软件是由美国UES公司开发的铸造过程模拟软件,采用基于有限元(FEM)的数值计算和综合求解的方法,对铸件充型、凝固和冷却过程中的流场、温度场、应力场、电磁场进行模拟分析。

一、软件模块:如图1所示,ProCAST软件包括8个模块:1、基本模块Base Module:基本模块包括温度场、凝固、材料数据库及前后处理。

2、剖分模块Meshing:产生输入模型的四面体体网格3、流动模块Fluid:对铸造过程中的流场进行模拟分析4、应力模块Stress:对铸造过程中的应力场进行模拟分析5、微结构模块Microstructure:对铸件的微观组织结构进行模拟分析6、电磁模块Electromagnetic:对铸造过程中的电磁场进行模拟分析7、辐射模块Radiation:对铸造过程中的辐射能量进行模拟分析8、逆运算模块Inverse:采用逆运算计算界面条件参数和边界条件参数二、模拟过程ProCAST软件的模拟流程包括:1、创建模型:可以分别用I-Deas、Pro/E、UG、Patran、Ansys 作为前处理软件创建模型,输出ProCAST可接受的模型或网格文件。

2、MeshCAST:对输入的模型或网格文件进行剖分,最终产生四面体体网格,生成xx.mesh文件,文件中包含节点数量、单元数量、材料数量等信息。

3、PreCAST:分配材料、设定界面条件、边界条件、初始条件、模拟参数,生成xxd.out和xxp.out文件,4、DataCAST:检查模型及PreCAST中对模型的定义是否有错误,如有错误,输出错误信息,如无错误,将所有的模型信息转换为二进制,生成xx.unf文件。

5、ProCAST:对铸造过程模拟分析计算,生成xx.unf文件。

无私奉献解构高考英语阅读试题

词·清平乐禁庭春昼,莺羽披新绣。

百草巧求花下斗,只赌珠玑满斗。

日晚却理残妆,御前闲舞霓裳。

谁道腰肢窈窕,折旋笑得君王。

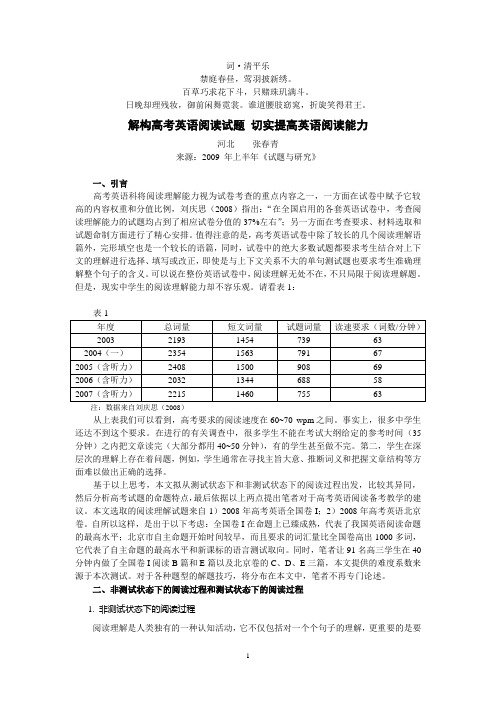

解构高考英语阅读试题切实提高英语阅读能力河北张春青来源:2009 年上半年《试题与研究》一、引言高考英语科将阅读理解能力视为试卷考查的重点内容之一,一方面在试卷中赋予它较高的内容权重和分值比例,刘庆思(2008)指出:“在全国启用的各套英语试卷中,考查阅读理解能力的试题均占到了相应试卷分值的37%左右”;另一方面在考查要求、材料选取和试题命制方面进行了精心安排。

值得注意的是,高考英语试卷中除了较长的几个阅读理解语篇外,完形填空也是一个较长的语篇,同时,试卷中的绝大多数试题都要求考生结合对上下文的理解进行选择、填写或改正,即使是与上下文关系不大的单句测试题也要求考生准确理解整个句子的含义。

可以说在整份英语试卷中,阅读理解无处不在,不只局限于阅读理解题。

但是,现实中学生的阅读理解能力却不容乐观。

请看表1:注:数据来自刘庆思(2008)从上表我们可以看到,高考要求的阅读速度在60~70 wpm之间。

事实上,很多中学生还达不到这个要求。

在进行的有关调查中,很多学生不能在考试大纲给定的参考时间(35分钟)之内把文章读完(大部分都用40~50分钟),有的学生甚至做不完。

第二,学生在深层次的理解上存在着问题,例如,学生通常在寻找主旨大意、推断词义和把握文章结构等方面难以做出正确的选择。

基于以上思考,本文拟从测试状态下和非测试状态下的阅读过程出发,比较其异同,然后分析高考试题的命题特点,最后依据以上两点提出笔者对于高考英语阅读备考教学的建议。

本文选取的阅读理解试题来自1)2008年高考英语全国卷I;2)2008年高考英语北京卷。

自所以这样,是出于以下考虑:全国卷I在命题上已臻成熟,代表了我国英语阅读命题的最高水平;北京市自主命题开始时间较早,而且要求的词汇量比全国卷高出1000多词,它代表了自主命题的最高水平和新课标的语言测试取向。

市场微观结构

组合收益率的矩

• 假设对所有证券按照不交易的概率来进 行分组,在此基础上组成等权重的证券 组合:组合A包含有 N a 个证券(不交易 概率均为 π a),组合B包含有 N b 个证券 0 0 π b )。定义 rat 和 rbt (不交易概率均为 为这两个组合在 t 时刻的观察收益率。 则

1 r ≈ Nk

• 三、不交易概率 • 假设在每一个t时期,证券i不交易的概 率为 π i ,证券交易与否独立于真实收益 率 {rit },且独立于任何其他随机变量。 这样,不同的证券有不同的不交易概率, 而每一种证券的不交易过程可以被视为 是一种抛硬币的独立同分布过程(IID)。

模型的推导

• 引入两个伯奴力(Bernoulli)指示变量:

k =1 j =1 ∞ k

• 则 kt 为 t 期前连续不交易的期数。

rit0 = ∑ rit − k

k =0

kt

(3)

rit0 = ∑ rit − k

k =0

kt

• 这说明观察收益率是所有过去真实收益 0 率的随机函数,即 rit 可以表示为随机 期数 (kt ) 的随机变量 ( rit ) 的和。 • 该等式概率为 (1 − π i )2 π ik = (1 − π i )π ik (1 − π i ) • 其中,第一个 (1 − π i ) 意味着第 t 期交易, 而后一个 (1 − π i ) 意味着第 kt −1 期交易, 而 π ikt 则意味着中间 kt 期均不交易。

• 3、真实收益过程的数字特征: • 根据假设,每一时期的真实收益率都是 随机的,并且反映消息到达和非系统噪 声。且有:

E[rit ] = µi (由于E ( ft ) = 0,且E (ε it ) = 0)

什么是电泳显示技术

什么是电泳显示技术(EPD)?电泳显示技术(EPD)又称电泳显示器,是类纸式显示器较早发展的显示技术,是利用有颜色的带电球,藉由外加电场,在液态环境中移动,呈现不同颜色的显示效果,其代表厂商包括E-Ink与Sipix。

日本Bridgestone所推出的高速响应液态显示器(QR-LPD),其工作原理与EPD 相似,只是其成像的物质不是使用带电球,而是由黑白2色的粉末在电场之间移动产生显示效果。

另外发展较早的胆固醇液晶(ChLC),是一种结构相似于胆固醇分子的液晶。

胆固醇反射式显示器在不加电压时,可存在两种稳定的状态,利用两个状态之间的转换,呈现亮暗态的显示效果。

其它还有强诱电性液晶(FerroelectricLiquid Crystal;FLC)等。

电泳显示(Electrophoretic,E-Paper)技术由于结合了普通纸张和电子显示器的优点,是最有可能实现电子纸张产业化的技术。

目前它已从众多显示技术中脱颖而出,成为极具发展潜力的柔性电子显示技术之一。

据iSuppli预测,电泳显示全球市场2006年仅仅900万美元,但是预计到2013年将增加到2.47亿美元,年均增长率高达60.5%。

该增长的大部分市场在指示标和新颖的直接驱动显示器,另外电子显示卡、柔性电子阅读器、电子纸张和数字签字等产品也将获得应用。

一、电泳技术及其优势何为电泳技术?照字面意味着“在一定的电压下可泳动”,其显示的工作原理是靠浸在透明或彩色液体之中的电离子移动,即通过翻转或流动的微粒子来使像素变亮或变暗,并可以被制作在玻璃、金属或塑料衬底上。

具体技术是将直径约为1mm的二氧化钛粒子被散布在碳氢油中,黑色染料、表面活性剂以及使粒子带电的电荷控制剂也被加到碳氢油中;这种混合物被放置在两块间距为10—100mm的平行导电板之间,当对两块导电板加电压时,这些粒子会以电泳的方式从所在的薄板迁移到带有相反电荷的薄板上。

当粒子位于显示器的正面(显示面)时,显示屏为白色,这是因为光通过二氧化钛粒子散射回阅读者一方;当粒子位于显示器背面时,显示器为黑色,这是因为彩色染料吸收了入射光。

triz理论的40个原理

triz理论的40个原理1. 1. 矛盾 (Contradiction)2. 2. 聚合 (Aggregation)3. 3. 优化传递 (Transferring)4. 4. 整合 (Integration)5. 5. 分离 (Separation)6. 6. 宇宙相似性 (Similarity)7. 7. 中介 (Mediator)8. 8. 统一 (Uniformity)9. 9. 反馈 (Feedback)10. 10. 副本 (Replication)11. 11. 增加热量、增加温度 (Increase heat, increase temperature)12. 12. 减少热量、减少温度 (Decrease heat, decrease temperature)13. 13. 分级 (Gradation)14. 14. 最大与最小 (Maximum and minimum)15. 15. 动态平衡 (Dynamic equilibrium)16. 16. 时空因果关系 (Cause and effect)17. 17. 薄层 (Thin layer)18. 18. 耐用与脆弱 (Durability and fragility)19. 19. 数量效应 (Quantity effect)20. 20. 助推 (Boost)21. 21. 过滤 (Filtering)22. 22. 倒置 (Inversion)23. 23. 反向 (Opposite)24. 24. 反馈优化 (Feedback optimization)25. 25. 极点 (Polarity)26. 26. 振动 (Vibration)27. 27. 安全储存 (Safe storage)28. 28. 光照、照明 (Lighting)29. 29. 引导 (Guiding)30. 30. 柔性 (Flexibility)31. 31. 过程偶然性 (Process randomness)32. 32. 多级反馈 (Multi-feedback)33. 33. 生物模仿 (Biomimicry)34. 34. 相变 (Phase change)35. 35. 传感器 (Sensor)36. 36. 微结构 (Microstructure)37. 37. 切割 (Cutting)38. 38. 扩展 (Expansion)39. 39. 孔洞、通道 (Holes, channels)40. 40. 精确度与精密度 (Accuracy and precision)。

第09章 市场微观结构与流动性建模

第九章市场微观结构与流动性建模[学习目标]掌握市场微观结构的基本理论;熟悉流动性的主要计量方法;掌握市场流动性的计量与实证分析;了解高频数据在金融计量中的的主要应用。

第一节市场微观结构理论的发展一、什么是市场微观结构市场微观结构的兴起,是近40年来金融经济学最具开创性的发展之一。

传统的金融市场理论中,一直将金融资产价格作为一个宏观变量加以考察。

但是,从Demsetz发表《交易成本》(Transaction Cost)之后,金融资产价格研究视角发生了重大变化——从研究宏观经济现象转而关注于金融市场内在的微观基础,金融资产价格行为被描述为经济主体最优化规划的结果。

这种转变包含两方面的含义:一是由于资产价格是由特定经济主体和交易机制决定,因而对经济主体行为或交易机制分析可以考察价格形成;二是这一分析可以将市场行为看作是个体交易行为的加总,这样从单个交易者的决策行为,可以预测金融资产价格的变化情况。

金融市场微观结构(market microstructure)的最主要功能是价格发现(price discovery),即如何利用公共信息和私有信息进行决定一种证券的价格。

在金融市场微观结构理论中,市场交易机制处于基础性作用,当前世界各交易所采用的交易方式大致可分为报价驱动(quote-driven)和指令驱动(order-driven)两大类。

美国的NASDAQ以及伦敦的国际证券交易所等都属于报价驱动交易机制。

在这种市场上,投资者在递交指令之前就能够从做市商那里得到证券价格的报价。

这种交易方式主要由做市商充当交易者的交易对手,主要适合于流动性较差的市场。

与此相反,在指令驱动制度下,投资者递交指令要通过一个竞价过程来执行。

我国各大证券交易所以及日本的东京证券交易所等都采用这种交易方式。

在指令驱动机制下,交易既可以连续地进行,又可以定期地进行。

前者主要指连续竞价(continuous auction),投资者递交指令可以通过早已由公众投资者或市商递交的限价指令立即执行。

高阶讲解:什么是SOIwafer?

高阶讲解:什么是SOIwafer?今天我们就讲讲衬底材料的SOI制程,到底它牛在哪里?在过去五十多年中,从肖克莱等人发明第一个晶体管到超大规模集成电路出现,硅半导体工艺取得了一系列重大突破,使得以硅材料为主体的CMOS集成电路制造技术为主流,逐渐成为性能价格比最优异、应用最广泛的集成电路产业。

如果说在亚微米/深亚微米(Sub-Micron)时代,器件的主要bottleneck在热载流子效应(HCE: Hot Carrier Effect)以及短沟道效应(SCE: Short Channel Effect)。

那么在纳米(or Sub-0.1um)时代,随着器件特征尺寸的缩小,器件内部pn结之间以及器件与器件之间通过衬底的相互作用愈来愈严重,出现了一系列材料、器件物理、器件结构和工艺技术等方面的新问题,使得亚0.1微米硅集成电路的集成度、可靠性以及电路的性能价格比受到影响。

这些问题主要包括:(1) 体硅CMOS电路的寄生可控硅闩锁效应以及体硅器件在宇宙射线辐照环境中出现的软失效效应等使电路的可靠性降低;(2) 随着器件尺寸的缩小,体硅CMOS器件的各种多维及非线性效应如表面能级量子化效应、隧穿效应、短沟道效应、窄沟道效应、漏感应势垒降低效应、热载流子效应、亚阈值电导效应、速度饱和效应、速度过冲效应等变得十分显著,影响了器件性能的进一步改善;(3) 器件之间隔离区所占的芯片面积随器件尺寸的减小相对增大,使得寄生电容增加,互连线延长,影响了集成度及速度的提高。

虽然深槽隔离(STI->DTI, Deep Trench Isolation)、电子束刻蚀、硅化物、中间禁带栅电极等工艺技术能够降低这种效应,但是只要PN 结存在就会有耗尽区,只要有Well就会有衬底漏电,所以根本无法解决。

所以绝缘衬底上硅(Silicon-On-Insulator,简称SOI)技术以其独特的材料结构有效地克服了体硅材料不足,以前最早是在well底部做一个oxide隔离层,业界称之为BOX (Buried OXide),隔离了well的bulk的漏电,但是这种PN结依然在well里面,所以PN结电容和结漏电还是无法解决,这种结构我们称之为部分耗尽型SOI (PD-SOI)。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Market MicrostructureHans R. StollOwen Graduate School of ManagementVanderbilt UniversityNashville, TN 37203Hans.Stoll@Financial Markets Research CenterWorking paper Nr. 01- 16First draft: July 3, 2001This version: May 6, 2002For Handbook of the Economics of FinanceMarket MicrostructureHans R. StollAbstractThe field of market microstructure deals with the costs of providing transaction services and with the impact of such costs on the short run behavior of securities prices. Costs are reflected in the bid-ask spread (and related measures) and commissions. The focus of this chapter is on the determinants of the spread rather than on commissions. After an introduction to markets, traders and the trading process, I review the theory of the bid-ask spread in section II and examine the implications of the spread for the short run behavior of prices in section III. In section IV, the empirical evidence on the magnitude and nature of trading costs is summarized, and inferences are drawn about the importance of various sources of the spread. Price impacts of trading from block trades, from herding or from other sources, are considered in section V. Issues in the design of a trading market, such as the functioning of call versus continuous markets and of dealer versus auction markets, are examined in section VI. Even casual observers of markets have undoubtedly noted the surprising pace at which new trading markets are being established even as others merge. Section VII briefly surveys recent developments in U.S securities markets and considers the forces leading to centralization of trading in a single market versus the forces leading to multiple markets. Most of this chapter deals with the microstructure of equities markets. In section VIII, the microstructure of other markets is considered. Section IX provides a brief discussion of the implications of microstructure for asset pricing. Section X concludes.Market MicrostructureHans R. StollMarket microstructure deals with the purest form of financial intermediation -- the trading of a financial asset, such as a stock or a bond. In a trading market, assets are not transformed (as they are, for exam ple, by banks that transform deposits into loans) but are simply transferred from one investor to another. The financial intermediation service provided by a market, first described by Demsetz (1968) is immediacy. An investor who wishes to trade immediately – a demander of immediacy – does so by placing a market order to trade at the best available price – the bid price if selling or the ask price if buying. Bid and ask prices are established by suppliers of immediacy. Depending on the market design, suppliers of immediacy may be professional dealers that quote bid and ask prices or investors that place limit orders, or some combination.Investors are involved in three different markets – the market for information, the market for securities and the market for transaction services. Market microstructure deals primarily with the market for transaction services and with the price of those services as reflected in the bid-ask spread and commissions. The market for securities deals with the determination of securities prices. The literature on asset pricing often assumes that markets operate without cost and without friction whereas the essence of market microstructure research is the analysis of trading costs and market frictions. The market for information deals with the supply and demand of information, including the incentives of securities analysts and the adequacy of information. This market, while conceptually separate, is closely linked to the market for transaction services since the difficulty and cost of a trade depends on the information possessed by the participants in the trade.Elements in a market are the investors who are the ultimate demanders and suppliers of immediacy, the brokers and dealers who facilitate trading, and the market facility within which trading takes place. Investors include individual investors and institutional investors such as pension plans and mutual funds. Brokers are of two types: upstairs brokers, who deal with investors, and downstairs brokers, who help process transactions on a trading floor. Brokers are agents and are paid by a commission. Dealerstrade for their own accounts as principals and earn revenues from the difference between their buying and selling prices. Dealers are at the heart of most organized markets. The NYSE (New York Stock Exchange) specialist and the Nasdaq (National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation) market makers are dealers who maintain liquidity by trading with brokers representing public customers. Bond markets and currency m arkets rely heavily on dealers to post quotes and maintain liquidity.The basic function of a market – to bring buyers and sellers together -- has changed little over time, but the market facility within which trading takes place has been greatly influenced by technology. In 1792, when the New York Stock Exchange was founded by 24 brokers, the market facility was the buttonwood tree under which they stood. Today the market facility, be it the NYSE, Nasdaq or one of the new electronic markets, is a series of high-speed communications links and computers through which the large majority of trades are executed with little or no human intervention. Investors may enter orders on-line, have them routed automatically to a trading location and executed against standing orders entered earlier, and automatically sent for clearing and settlement. Technology is changing the relationship among investors, brokers and dealers and the facility through which they interact.Traditional exchanges are membership organizations for the participating brokers and dealers. New markets are computer communications and trading systems that have no members and that are for-profit businesses, capable in principal of operating without brokers and dealers. Thus while the function of markets – to provide liquidity to investors – will become increasingly important as markets around the world develop, the exact way in which markets operate will undoubtedly change.The field of market microstructure deals with the costs of providing transaction services and with the impact of such costs on the short run behavior of securities prices. Costs are reflected in the bid-ask spread (and related measures) and commissions. The focus of this chapter is on the determinants of the spread rather than on commissions. After an introduction to markets, traders and the trading process, I review the theory of the bid-ask spread in section II and examine the implications of the spread for the short run behavior of prices in section III. In section IV, the empirical evidence on the magnitude and nature of trading costs is summarized, and inferences are drawn about theimportance of various sources of the spread. Price impacts of trading from block trades, from herding or from other sources, are considered in section V. Issues in the design of a trading market, such as the functioning of call versus continuous markets and of dealer versus auction markets, are examined in section VI. Even casual observers of markets have undoubtedly noted the surprising pace at which new trading markets are being established even as others merge. Section VII briefly surveys recent developments in U.S securities markets and considers the forces leading to centralization of trading in a single market versus the forces leading to multiple markets. Most of this chapter deals with the microstructure of equities markets. In section VIII, the microstructure of other markets is considered. Section IX provides a brief discussion of the implications of microstructure for asset pricing. Section X concludes.1I.Markets, traders and the trading process.I.A. Types of markets.It is useful to distinguish major types of market structures, although most real-world markets are a mixture of market types. An important distinction is between auction and dealer markets. A pure auction market is one in which investors (usually represented by a broker) trade directly with each other without the intervention of dealers. A call auction market takes place at specific times when the security is called for trading. In a call auction, investors place orders – prices and quantities – which are traded at a specific time according to specific rules, usually at a single market clearing price. For example, the NYSE opens with a kind of call auction market in which the clearing price is set to maximize the volume of trade at the opening.While many markets, including the NYSE and the continental European markets, had their start as call auction markets, such markets have become continuous auction markets as volume has increased. In a continuous auction market, investors trade against resting orders placed earlier by other investors and against the “crowd” of floor brokers. Continuous auction markets have two-sides: Investors, who wish to sell, trade at the bid1 For other overviews of the field of market microstructure, see Madhavan (2000), the chapter in this volume by Easley and O’Hara, and O’Hara (1995).price established by resting buy orders or at prices in the “crowd,” and investors, who wish to buy, trade at the asking price established by resting sell orders or at prices in the “crowd.” The NYSE is said to be a continuous auction market with a “crowd”. Electronic markets are continuous auction markets without a “crowd.”A pure dealer market is one in which dealers post bids and offers at which public investors can trade. The investor cannot trade directly with another investor but must buy at the dealers ask and sell at the dealers bid. Bond markets and currency markets are dealer markets. The Nasdaq Stock Market started as a pure dealer market, although it now has many features of an auction market because investors can enter resting orders that are displayed to other investors.Dealer markets are physically dispersed and trading is conducted by telephone and computer. By contrast, auction markets have typically convened at a particular location such as the floor of an exchange. With improvements in communications technology, the distinction between auction and dealer markets has lessened. Physical centralization of trading on an exchange floor is no longer necessary. The purest auction market is not the NYSE, but an electronic market (such as Island or the Paris Bourse) that takes place in a computer. The NYSE, in fact is a mixed auction/dealer market because the NYSE specialist trades for his own account to maintain liquidity in his assigned stocks. The Nasdaq Stock market is in fact also a mixed dealer/auction market because public orders are displayed and may be executed against incoming orders.I.B. Types of ordersThe two principal types of orders are a market order and a limit order. A market order directs the broker to trade immediately at the best price available. A limit order to buy sets a maximum price that will be paid, and a limit order to sell sets a minimum price that will be accepted. In a centralized continuous auction market, the best limit order to buy and the best limit order to sell (the top of the book) establish the market, and the quantities at those prices represent the depth of the market. Trading takes place as incoming market orders trade with the best posted limit orders. In traditional markets, dealers and brokers on the floor may intervene in this process. In electronic markets the process is fully automated.In a pure dealer market, limit orders are not displayed but are held by the dealer to whom they are sent, and market orders trade at the dealers bid or ask, not with the limit orders. In some cases, such as Nasdaq before the reforms of the mid 1990s, a limit order to buy only executes if the dealer’s ask falls to the level of the limit price. For example suppose the dealer’s bid and ask are 20 to 20 ¼ , and suppose the dealer holds a limit order to buy at 20 1/8. Incoming sell market orders would trade at 20, the dealer bid, not at 20 1/8, the limit order. The limit order to buy would trade only when the ask price fell to 20 1/8. Nasdaq rules have been modified to require that the dealer trade customer limit orders at the same or better price before trading for his own account (Manning Rule), and to require the display of limit orders (the SEC’s order handling rules of 1997).Orders may also be distinguished by size. Small and medium orders usually follow the standard process for executing trades. Large orders, on the other hand, often require special handling. Large orders may be “worked” by a broker over the course of the day. The broker uses discretion when and how to trade segme nts of the order. Large orders may be traded in blocks. Block trades are often pre-negotiated “upstairs” by a broker who has identified both sides of the trade. The trade is brought to a trading floor, as required by exchange rules and executed at the pre-arranged prices. The exchange specifies the rules for executing resting limit orders.I.C. Types of tradersTraders in markets may be classified in a variety of ways.Active versus passiveSome traders are active (and normally employ market orders), while others are passive (and normally employ limit orders). Active traders demand immediacy and push prices in the direction of their trading, whereas passive traders supply immediacy and stabilize prices. Dealers are typically passive traders. Passive traders tend to earn profits from active traders.Liquidity versus informedLiquidity traders trade to smooth consumption or to adjust the risk-return profiles of their portfolios. They buy stocks if they have excess cash or have become more risk tolerant, and they sell stocks if the need cash or have become less risk tolerant. Informedtraders trade on private information about an asset’s value. Liquidity traders tend to trade portfolios, whereas informed traders tend to trade the specific asset in which they have private information. Liquidity traders lose if they trade with informed traders. Consequently they seek to identify the counterparty. Informed traders, on the other hand, seek to hide their identity. Many models of market microstructure involve the interaction of informed and liquidity traders.Individual versus institutionalInstitutional investors – pension funds, mutual funds, foundations and endowments – are the dominant actors in stock and bond markets. They hold and manage the majority of assets and account for the bulk of share volume. They tend to trade in larger quantities and face special problems in minimizing trading costs and in benefiting from any private information. Individual investors trade in smaller amounts and account for the bulk of trades. The structure of markets must accommodate these very different players. Institutions may wish to cross a block of 100,000 shares into a market where the typical trade is for 3,000 shares. Markets must develop efficient ways to handle the large flow of relatively small orders while at the same time accommodating the needs of large investors to negotiate large transactions.Public versus professionalPublic traders trade by placing an order with a broker. Professional traders trade for their own accounts as market makers or floor traders and in that process provide liquidity. Computers and high speed communications technology have changed the relative position of public and professional traders. Public traders can often trade as quickly from upstairs terminals (supplied to them by brokers) as professional traders can trade from their terminals located in offices or on an exchange floor. Regulators have drawn a distinction between professional and public traders and have imposed obligations on professional traders. Market makers have an affirmative obligation to maintain fair and orderly markets, and they are obligated to post firm quotes. However, as the distinction between a day trader trading from an upstairs terminal and a floor trader becomes less clear, the appropriate regulatory policy becomes more difficult.I.D. Rules of precedenceMarkets specify the order in which resting limit orders and/or dealer quotes execute against incoming market orders. A typical rule is to give first priority to orders with the best price and secondary priority to the order posted first at a given price. Most markets adhere to price priority, but many modify secondary priority rules to accommodate large transactions. Suppose there are two resting orders at a bid price of $40. Order one is for 2,000 shares and has time priority over order two, which is for 10,000 shares. A market may choose to allow an incoming market order for 10,000 shares to trade with resting order two rather than break up the order into multiple trades. Even price priority is sometimes difficult to maintain, particularly when different markets are involved. Suppose the seller of the 10,000 shares can only find a buyer for the entire amount at $39.90, and trades at that price. Such a trade would “trade-through” the $40 price of order one for 2,000 shares. Within a given market, such trade-throughs are normally prohibited – the resting limit order at $40 must trade before the trade at $39.90. In a dealer market, like Nasdaq, where each dealer can be viewed as a separate market, a dealer may not trade through the price of any limit order he holds, but he may trade through the price of a limit order held by another dealer. When there are many competing markets each with its own rules of precedence, there is no requirement that rules of precedence apply across markets. Price priority will tend to rule because market orders will seek out the best price, but time priority at each price need not be satisfied across markets.The working of rules of precedence is closely tied to the tick size, the minimum allowable price variation. As Harris (1991) first pointed out, time priority is meaningless if the tick size is very small. Suppose an investor places a limit order to buy 1000 shares at $40. If the tick size is $0.01, a dealer or another trader can step in front with a bid of 40.01 – a total cost of only $10. On the other hand, the limit order faces the danger of being “picked off” should new information warrant a lower price. If the tick size were $0.10, the cost of stepping in front of the investor’s limit order would be greater ($100). The investor trades off the price of buying immediately at the current ask price, say $40.20, against giving up immediacy in the hope of getting a better price with the limit order at $40. By placing a limit order the investor supplies liquidity to the market. Thesmaller tick size reduces the incentive to place limit orders and hence adversely affects liquidity.Price matching and payment for order flow are other features of today’s markets related to rules of precedence. Price matching occurs when market makers in a satellite market promise to match the best price in the central market for orders sent to them rather than to the central market. The retail broker usually decides which market maker receives the order flow. Not only is the broker not charged a fee, he typically receives a payment (of one to two cents a share) from the market maker. Price matching and payment for order flow are usually bilateral arrangements between a market making firm and a retail brokerage firm. Price matching violates time priority: When orders are sent to a price matching dealer, they are not sent to the market that first posted the best price. Consequently the incentive to post limit orders is reduced because the limit order may be stranded. Similarly, the incentive of dealers to post good quotes is eliminated if price matching is pervasive: A dealer who quotes a better price is unable to attract additional orders because orders are preferenced to other dealers who match the price.I.E. The trading processThe elements of the trading process may be divided into four components – information, order routing, execution, and clearing. First, a market provides information about past prices and current quotes. Earlier in its history, the NYSE jealously guarded ownership of its prices, making data available only to its members or licensed recipients. But today transaction prices and quotes are disseminated in real-time over a consolidated trade system (CTS) and a consolidated quote system (CQS). Each exchange participating in these systems receives tape revenue for the prices and quotes it disseminates. The real-time dissemination of these prices makes all markets more transparent and allows investors to determine which markets have the best prices, thereby enhancing competition.Second, a mechanism for routing orders is required. Today brokers take orders and route them to an exchange or other market center. For example, the bulk of orders sent to the NYSE are sent via DOT (Designated Turnaround System), an electronic system that sends an order directly to the specialist. Retail brokers establish proceduresfor routing orders and may route orders in return for payments. Orders may not have the option of being routed to every trading center and may therefore have difficulty in trading at the best price. Central to discussions about a national market system, is the mechanism for routing orders among different market centers, and the rules, if any, that regulators should establish.The third phase of the trading process is execution. In today’s automated world this seems a simple matter of matching an incoming market order with a resting quote. However this step is surprisingly complex and contentious. Dealers are reluctant to execute orders automatically because they fear being “picked off” by speedy and informed traders, who have better information. Instead, they prefer to delay execution, if even for only 15 seconds, to determine if any information or additional trades arrive. Automated execution systems have been exploited by speedy customers to the disadvantage of dealers. Indeed, as trading becomes automated the distinction between dealers and customers decreases because customers can get nearly as close to “the action” as dealers.A less controversial but no less important phase of the trading process is clearing and settlement. Clearing involves the comparison of transactions between buying and selling brokers. These comparisons are made daily. Settlement in U.S. equities markets takes place on day t+3, and is done electronically by book entry transfer of ownership of securities and cash payment of net amounts to the clearing entity.II.Microstructure theory – determinants of the bid-ask spread.Continuous markets are characterized by the bid and ask prices at which trades can take place. The bid-ask spread reflects the difference between what active buyers must pay and what active sellers receive. It is an indicator of the cost of trading and the illiquidity of a market. Alternatively, illiquidity could be measured by the time it takes optimally to trade a given quantity of an asset [Lippman and McCall (1986)]. The two approaches converge because the bid-ask spread can be viewed as the amount paid to someone else (i.e. the dealer) to take on the unwanted position and dispose of it optimally. Our focus is on the bid-ask spread. Bid-ask spreads vary widely. In inactive markets – for example, the real estate market – the spread can be wide. A house could beoffered at $500,000 with the highest bid at $450,000. On the other hand the spread for an actively traded stock is today often less than 10 cents per share. A central issue in the field of microstructure is what determines the bid-ask spread and its variation across securities.Several factors determine the bid-ask spread in a security. First, suppliers of liquidity, such as the dealers who maintain continuity of markets, incur order handling costs for which they must be compensated. These costs include the costs of labor and capital needed to provide quote information, order routing, execution, and clearing. In a market without dealers, where limit orders make the spread, order handling costs are likely to be smaller than in a market where professional dealers earn a living. Second the spread may reflect non competitive pricing. For example, market makers may have agreements to raise spreads or may adopt rules, such as a minimum tick size, to increase spreads. Third, suppliers of immediacy, who buy at the bid or sell at the ask, assume inventory risk for which they must be compensated. Fourth, placing a bid or an ask grants an option to the rest of the market to trade on the basis of new information before the bid or ask can be changed to reflect the new information. Consequently the bid and ask must deviate from the consensus price to reflect the cost of such an option. A fifth factor has received the most attention in the microstructure literature; namely the effect of asymmetric information. If some investors are better informed than others, the person who places a firm quote (bid or ask) loses to investors with superior information.The factors determining spreads are not mutually exclusive. All may be present at the same time. The three factors related to uncertainty – inventory risk, option effect and asymmetric information – may be distinguished as follows. The inventory effect arises because of possible adverse public information after the trade in which inventory is acquired. The expected value of such information is zero, but uncertainty imposes inventory risk for which suppliers of immediacy must be compensated. The option effect arises because of adverse public information before the trade and the inability to adjust the quote. The option effect really results from an inability to monitor and immediately change resting quotes. The adverse selection effect arises because of the presence of private information before the trade, which is revealed sometime after the trade. The information effect arises because some traders have superior information.The sources of the bid-ask spread may also be compared in terms of the services provided and the resources used. One view of the spread is that it reflects the cost of the services provided by liquidity suppliers. Liquidity suppliers process orders, bear inventory risk, using up real resources. Another view of the spread is that it iscompensation for losses to informed traders. This informational view of the spread implies that informed investors gain from uninformed, but it does not imply that any services are provided or that any real resources are being used.Let us discuss in more detail the three factors that have received most attention in the microstructure literature – inventory risk, free trading option, and asymmetric information.II.A. Inventory risk Suppliers of immediacy that post bid and ask prices stand ready take on inventory and to assume the risk associated with holding inventory. If a dealer buys 5000 shares at the bid, she risks a drop in the price and a loss on the inventory position. An investor posting a limit order to sell 1000 shares at the ask faces the risk that the stock he is trying to sell with the limit order will fall in price before the limit order is executed. In order to take the risk associated with the limit order, the ask price must be above the bid price at which he could immediately sell by enough to offset the inventory risk. Inventory risk was first examined theoretically in Garman (1976), Stoll (1978a), Amihud andMendelson (1980), Ho and Stoll (1981, 1983). This discussion follows Stoll (1978a).To model the spread arising from inventory risk, consider the determination of a dealer’s bid price. The bid price must be set at a discount below the consensus value of the stock to compensate for inventory risk. Let P be the consensus price, let P b be the bid price, and let C be the dollar discount on a trade of Q dollars. The proportional discountof the bid price from the consensus stock price, P , is b P P C c P Q−=≡ . The problem is to derive C or equivalently, c . This can done by solving the dealer’s portfolio problem. Let the terminal wealth of the dealer’s optimal portfolio in the absence of making markets be °W. The dealer’s terminal wealth if he stands ready to buy Q dollars of stock at a discount of C dollars is °(1)(1)()f Wr Q r Q C ++−+−%, where r % is the return on the stock。