性别与文学概论参考书目(理论部分)

《文学概论》课程纲要(《文学理论教程》、《文学基本原理》)教学大纲

讲授

或者期中作业集中展示

期中作业PPT展示

十四

文学消费与接受

1.文学消费和一般消费的关系

*2.文学消费的意义

#3.文学消费与文学接受的特点

2

讲授

案例分析

十五

文学接受的过程

1.文学接受的动机

*2.期待遇挫的概念

#3.文学接受的高潮

2

讲授

案例分析

十六

文学批评

1.文学批评的性质

*2.文学批评的意识形态

#3.各类文学批评的特征

XXXXXXX大学

《文学概论》课程纲要

一、课程基本情况

课程名称

(中/英文)

文学概论

TheoryofLiterary

学时/学分

32/2

课程编码

课程性质

专业基础课

周学时

2

课程简介

《文学概论》是一门研究一切文学现象,探索文学本质规律的人文科学,主要讲授文学理论基本原理和基本知识的课程。使学生初步形成分析文学现象,解决文学实践中的问题的理论思维模式,为学习各门文学史和文艺理论史的课程作好理论准备。

2

讲授

案例分析

九

文学创作的原则

1.文学创作的原则

*2.艺术真实与艺术概括

#3.文学形象的典型化

2

讲授

案例分析

十

文学创作的主客体

1.文学创作主体是什么

*2.文学创作的主客体之间的关系

#3.作家与外部环境的关系

2

讲授

案例分析

[作业3]:

1.内容:作家的个性对创作有什么影响,通过你自己的创作属于自己的作品?

2

讲授

案例分析

备注:在知识点一栏中,“*”、“#”分别为重点、难点标注,放置在知识点序号前。

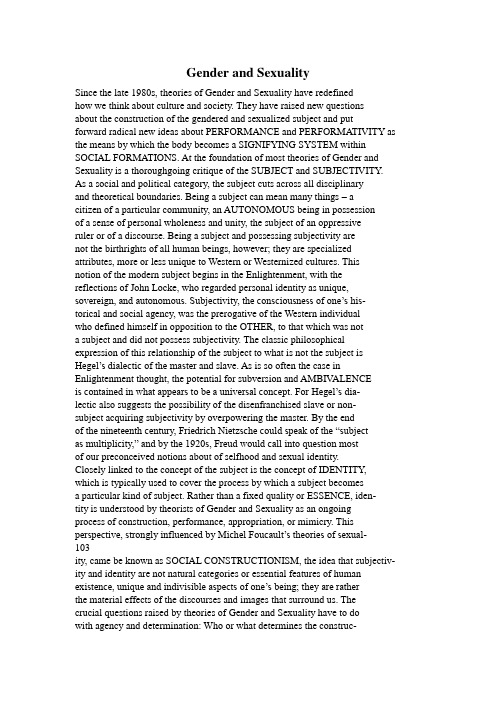

完整综述版-文学理论之性别与性文论(英语)Gender and Sexuality

Gender and SexualitySince the late 1980s, theories of Gender and Sexuality have redefinedhow we think about culture and society. They have raised new questionsabout the construction of the gendered and sexualized subject and putforward radical new ideas about PERFORMANCE and PERFORMATIVITY as the means by which the body becomes a SIGNIFYING SYSTEM within SOCIAL FORMATIONS. At the foundation of most theories of Gender and Sexuality is a thoroughgoing critique of the SUBJECT and SUBJECTIVITY. As a social and political category, the subject cuts across all disciplinaryand theoretical boundaries. Being a subject can mean many things – acitizen of a particular community, an AUTONOMOUS being in possessionof a sense of personal wholeness and unity, the subject of an oppressiveruler or of a discourse. Being a subject and possessing subjectivity arenot the birthrights of all human beings, however; they are specialized attributes, more or less unique to Western or Westernized cultures. Thisnotion of the modern subject begins in the Enlightenment, with the reflections of John Locke, who regarded personal identity as unique, sovereign, and autonomous. Subjectivity, the consciousness of one’s his- torical and social agency, was the prerogative of the Western individualwho defined himself in opposition to the OTHER, to that which was nota subject and did not possess subjectivity. The classic philosophical expression of this relationship of the subject to what is not the subject is Hegel’s dialectic of the master and slave. As is so often the case in Enlightenment thought, the potential for subversion and AMBIV ALENCEis contained in what appears to be a universal concept. For Hegel’s dia-lectic also suggests the possibility of the disenfranchised slave or non-subject acquiring subjectivity by overpowering the master. By the endof the nineteenth century, Friedrich Nietzsche could speak of the “subjectas multiplicity,” and by the 1920s, Freud would call into question mostof our preconceived notions about of selfhood and sexual identity.Closely linked to the concept of the subject is the concept of IDENTITY, which is typically used to cover the process by which a subject becomesa particular kind of subject. Rather than a fixed quality or ESSENCE, iden-tity is understood by theorists of Gender and Sexuality as an ongoingprocess of construction, performance, appropriation, or mimicry. This perspective, strongly influenced by Michel Foucault’s theories of sexual-103ity, came be known as SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM, the idea that subjectiv- ity and identity are not natural categories or essential features of human existence, unique and indivisible aspects of one’s being; they are ratherthe material effects of the discourses and images that surround us. Thecrucial questions raised by theories of Gender and Sexuality have to dowith agency and determination: Who or what determines the construc-tion of gender and sexuality? How is social AGENCY acquired and main- tained by these constructions? Is one constructed solely by social ideologies and institutions? Or do individuals have the freedom toact reflexively, to engage in what Anthony Giddens calls “projects ofthe self ”? For Foucault, sexuality has played a fundamental role in developing modern modes of social organization and regulation. In his landmark study, History of Sexuality (1976), Foucault argues that sexual- ity, far from being proscribed or repressed in the nineteenth century, became part of a discourse that sought to identify and regulate all forms of sexua l behavior. “Instead of a massive censorship,” he claimed, “what was involved was a regulated and polymorphous incitement to dis- course” (34). Religious confession, Psychoanalysis, sexology, literature–all were instrumental in this incitement, which simultaneously made sexuality a public matter and a target of social administration. “Underthe authority of a language that had been carefully expurgated so thatit was no longer directly named, sex was taken charge of, trackeddown as it were, by a discourse that aimed to allow it no obscurity, no respite” (20).Foucault’s critique of sexuality brilliantly exposed the ideological mechanisms by which sexual identities are maintained and regulated by institutional authorities. In this regard, his work paralleled that of Louis Althusser whose theory of IDEOLOGY held that the subject is always already “interpellated,” coercively recruited by ideological apparatusesof the State. (On Althusser, see pp. 112–13.) Subjectivity, selfhood, and citizenship are the products of socialization; agency, that quantum ofwill that enables the subject to move within social spheres, is a productof those very spheres. In another direction, Giddens argues that the individual has many significant opportunities to intervene in the ideo- logical construction of subjectivity; she is able to choose from an arrayof available discursive strategies and write the narrative of herself. These techniques of self-development guarantee freedom even in contexts of overwhelming social power. In his later work, Foucault recognized that 104the individual possessed a necessary freedom from POWER, which is “exercised only over free subjects . . . and only insofar as they are free. By this we mean individual or collective subjects who are faced with a field of possibilities in which several ways of behaving, several reactions and diverse comportments may be realized” (“Subject” 221).Judith Butler is perhaps the most influential theorist to explore theidea of sexual and gender identity as a social PERFORMANCE, a site of power and discourse. “To what extent,” she asks, “do regulatory practices of gender formation and division constitute identity, the internal coher- ence of the subject, indeed, the self-identical status of the person?”(Gender Trouble 16). As an alternative to such naturalized regulatorypractices, she developed a model of PERFORMATIVITY, which she distin- guished from a normative model of PERFORMANCE:[performance] presumes a subject, but [performativity] contests the very notion of the subject. . . . What I’m trying to do is think about performa-tivity as that aspect of discourse that has the capacity to produce what it names. Then I take a further step, through the Derridean rewriting of [ J. L.] Austin, and suggest that this production actually always happens througha certain kind of repetition and recitation. So if you want the ontology of this, I guess performativity is the vehicle through which ontologicaleffects are established. Performativity is the discursive mode by whichont ological effects are installed. (“Gender” 111–12)According to Butler, gender and sexual identity (self-consciousness aboutthe ontology or “being” of the self) has always been a matter of perfor- mance, acquiescence to social norms and to mystifications about sexual-ity and gender derived from philosophy, religion, psychology, medicine,and popular culture. Performativity upsets these norms, sometimes appropriating them in a transformed fashion, at other times parodyingor miming them in a way that draws out their salient elements for criti- cism. The “ontological effects” to which Butler refers are all that we cansee or know of “true” gender or sexual identity, a situation dramatizedmost clearly in drag and other forms of transvestism. For while the drag queen prides himself on getting every detail right and being true to a particular vision of femininity, his performance is in the end a critiqueof the very category of woman he strives to imitate faithfully. These reflections on the ontology of sexual identity have led Butler and othersto argue that the so-called biological notion of “sex” may itself not be105free from a performative dimension. Performativity, as a mode of subject-and identity-formation, is clearly indebted to poststructuralist notions of language and TEXTUALITY premised on the idea of the subject as the subject of a discourse. It is the quintessential expression of personal agencyin a context of late MODERNITY, a context in which naturalistic, biologi- cal, or ESSENTIALIST conceptions of the subject and of gender and sexual identity are no longer operative. Performativity is, paradoxically, the provisional result of a process of construction and the material sign ofan authentic self. Butler’s later work, especially Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative (1997), indicates the decisive role that public language–her chief example is “hate speech” – plays in constituting the performa- tive element of social life.Innovations in queer theory have made it evident that performativityis a function of the choices that gay and lesbian individuals make everyday and in all walks of life. To a certain extent, such individuals havealways known that the performative is the real. This is why, as AlanSinfield argues in The Wilde Centur y (1994), Oscar Wilde’s life experienceis as valuable for queer theory as his literary works, for it posits perfor- mativity at the foundation of queer identity.Queer theory seeks, among other things, to describe or map out theways homosexual or homoerotic desire manifests itself in literary and cultural texts. It is strongly reliant on psychoanalytic categories and concepts, but seeks to overcome the heterosexual limits of psychoana-lytic theory. Teresa de Lauretis, who was one of the first to use theterm queer theory, has since rejected it because of its appropriation by mainstream media. Certainly popular television shows like Queer Eye for the Straight Guy have made the word “queer,” which had been appropri- ated by the gay and lesbian movement as a symbol of political empower- ment, into a sanitized label for homosexuals with no political agenda. Others feel that queer theory privileges gay male experience at the expense of lesbian and bisexual experience. To some degree, the malebias is due to the strong influence of gay male theorists. It is also due tothe enormous influence of Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Between Men (1985), which, along with Foucault’s History of Sexuality, provided the theoretical scaffolding for academic queer theory. One of her most powerful formu- lations, the concept of homosociality, has come to enjoy rather widespread use across academic disciplines. HOMOSOCIAL DESIRE is grounded in René Girard’s theory of “triangular desire” and in Gayle Rubin’s theory106of the “sex/gender system,” specifically her critique of Lévi-Strauss’s analysis of kinship systems in which women function as gifts in eco-nomic exchanges between men. According to Sedgwick, homosocialdesire between men is expressed in a triangular structure with a woman(or a “discourse” of “woman”) standing as a putative object of at leastone of them: “the ultimate function of women is to be conduits of homo- social desire” (99). These relationships need not be sexual; in fact theyare far more potent whenever the sexual element is sublimated in the MIMICRY of a heterosexual identity that effectively disguises homosexual “deviancy.” Homosocial structures frequently elicit homophobia as an institutionalized check on repressed homosexual desire, but they moreoften lead to “changes in men’s experience of living within the shifting terms of compulsory heterosexuality” (134). Her chapter on HenryJames in her Epistemology of the Closet (1990) illustrates the divide between homosocial networking, which confirms the heterosexual status quo,and “homosexual panic,” which reacts violently against any manifesta-tion of eroticism or “genitalized” behavior that might emerge out of such networks.Queer theory has come to encompass a substantial body of work inlesbian studies. Moniqu e Wittig’s Lesbian Body attacks the tradition of anatomy based on the orderly and ordered male body and offers insteadthe lesbian body as a model of the desiring subject. Like other feministswho challenge the authority of PATRIARCHAL discourse, Wittig openly confronts the problem of the SUBJECT POSITION she occupies as a theorist and writer; she disrupts the texture of her writing and thus repeats atthe level of her discourse the disorderly nature of the lesbian body itself. Adrienne Rich, in her much-an thologized essay, “Compulsory Hetero- sexuality and the Lesbian Existence,” attacks “heterocentricity” as acovert mode of socialization that seeks willfully to repress the “enor-mous potential counterforce” (39) of lesbian experience. Because hetero- sexuality is the compulsory cultural norm, the oppression of women–their sexual slavery – is more difficult to name. Rich revalues the so-called perversity of lesbian desire, more frightening even than male homosexuality, and posits a “lesbian continuum” f ree of invidious binarysexual typologies. Lesbian Feminism is not concerned with hating menbut rather with celebrating the life choices of women who love women.It is not that heterosexuality is in and of itself oppressive, it is that “theabsence of cho ice remains the great unacknowledged reality” (67).107Acknowledging this reality and creating and preserving choice is what motivates the successors of Rich and Wittig. Thus Theresa de Lauretis,in The Practice of Love: Lesbian Sexuality and Perverse Desire (1994), chal- lenges psychoanalytical theories of normative sexuality that would limitsuch choices, and Lynda Hart, Fatal Women: Lesbian Sexuality and theMark of Aggression (1994), attacks the pathologization and appropriationof lesbian sexuality by the “male Imaginary” and defends women whorespond criminally to men who attempt to foreclose lesbian desire.In both cases free choice is celebrated, for without it there can be nochance for free subjects to combat the fortified positions of social andcultural power.Note. For more on issues related to gender and sexuality, see Femi-nism, Ethnic Studies, and Postcolonial Studies.WORKS CITEDButler, Judith. “Gender as Performance.” Interview. In A Critical Sense: Interviews with Intellectuals. Ed. Peter Osborne. London: Routledge, 1996.108–25.——. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Rout- ledge, 1990.Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality. 1976. V ol. 1. Trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978.——. “The Subject and Power.” In Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics. Eds. Herbert L. Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow. Chicago: Univer-sity of Chicago Press, 1984. 208–26.Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men: English Literature and Male Homosocial Desire. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.Rich, Adrienne. “Compulsory Heterosexuality and the Lesbian Existence.” InBlood, Bread and Poetry: Selected Prose 1979–1985. New York: Norton, 1986. 23–75.119/352。

文学概论书目

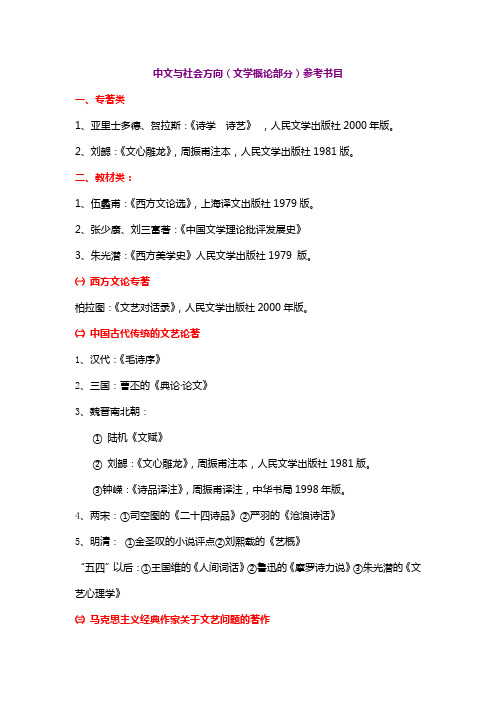

中文与社会方向(文学概论部分)参考书目

一、专著类

1、亚里士多德、贺拉斯:《诗学诗艺》,人民文学出版社2000年版。

2、刘勰:《文心雕龙》,周振甫注本,人民文学出版社1981版。

二、教材类:

1、伍蠡甫:《西方文论选》,上海译文出版社1979版。

2、张少康、刘三富著:《中国文学理论批评发展史》

3、朱光潜:《西方美学史》人民文学出版社1979 版。

㈠西方文论专著

柏拉图:《文艺对话录》,人民文学出版社2000年版。

㈡中国古代传统的文艺论著

1、汉代:《毛诗序》

2、三国:曹丕的《典论〃论文》

3、魏晋南北朝:

①陆机《文赋》

②刘勰:《文心雕龙》,周振甫注本,人民文学出版社1981版。

③钟嵘:《诗品译注》,周振甫译注,中华书局1998年版。

4、两宋:①司空图的《二十四诗品》②严羽的《沧浪诗话》

5、明清:①金圣叹的小说评点②刘熙载的《艺概》

“五四”以后:①王国维的《人间词话》②鲁迅的《摩罗诗力说》③朱光潜的《文艺心理学》

㈢马克思主义经典作家关于文艺问题的著作

1、傅腾霄主编:《马列文论选注》,社会科学文献出版社1999年版。

2、毛泽东《在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话》。

《文学概论》课程参考书目

3-4-3:参考书籍、文献、网站等《文学理论》课程教学参考书目和专业杂志介绍一、《文学理论》参考书目:第一编:《金玫瑰》(戴骢译),帕乌斯托夫斯基,百花文艺出版社;第二编:《基础诗学》,徐岱著,浙江大学出版社2005;第三编:《艺术创造工程》,余秋雨,上海文艺出版社;第四编:《艺术本体论》,王岳川,上海三联出版社;第五编:《文学理论》,王一川,四川人民出版社;其他综合类:1、《文学理论》,韦勒克、沃伦著,三联书店1984;2、《二十世纪文学理论》,佛克马、易布斯著,三联书店1988;3、《当代西方文学理论》,特里.伊格尔顿著,中国社会科学出版社1988;4、《西方二十世纪文论史》,胡经之、张首映著,中国社会科学出版社1988;5、《中国文学批评史》(上、下卷),敏泽著,人民文学出版社1981;6、《中国古代文论译讲》,赵则诚等著,吉林人民出版社1984;7、《中国文学批评通史》,王运熙、顾易生主编,上海古籍出版社1996;8、《中国古代文论的现代转换》,钱中文等主编,陕西师范大学出版社1997年;9、《最新西方文论选》,王逢振等编,漓江出版社1991;10、《美学》(第一卷),黑格尔著,商务印书馆1986;11、《判断力批判》(上、下卷),康德著,商务印书馆1987;12、《叙述学研究》,张寅德编,中国社会科学出版社1991;13、《小说修辞学》,布斯著,北京大学出版社1987;14、《西方哲学史》(上、下卷),罗素著,商务印书馆1991;15、《文学理论》(李平译),乔纳森·卡勒,辽宁教育出版社;16.《文学理论》(伍晓明译),特雷·伊格尔顿,陕西师范大学出版社;17.《追忆》(郑学勤译),宇文所安,上海古籍出版社;三联出版社;18.《中国文论》,宇文所安,上海社会科学出版社;19.《沉重的肉身》,刘小枫,上海人民出版社,华夏出版社;20.《我能否相信自己》,余华,人民日报出版社;21.《谈艺录》,钱钟书,中华书局。

2024年自考专业计划调整 教材 文学概论

2024年自考专业计划调整教材文学概论引言自考专业计划的调整是为了更好地适应个人的学习需求和目标。

本文将介绍2024年自考文学概论课程的教材选择和相关建议,以帮助考生进行合理的学习规划和备考准备。

教材选择文学概论是一门系统介绍文学发展史和文学理论的课程,旨在培养学生对文学作品的分析和鉴赏能力。

以下是一些常用的教材供考生参考:1.《中国文学史纲要》(作者:陈寅恪)该教材系统概述了中国文学的发展历程,包括先秦文学、唐宋元明清文学等各个时期的重要作品和流派,有利于学生全面了解中国文学的演进过程。

2.《西方文学史纲要》(作者:胡适)这本教材简明扼要地介绍了西方文学的主要发展阶段和代表作品,包括古希腊罗马文学、中世纪文学、文艺复兴文学、现代主义文学等。

适合对西方文学发展有基本了解的学生。

3.《文学概论》(作者:杜传军)这本教材系统讲述了文学理论的基本概念和流派,包括形式主义、新批评、后现代主义等。

同时介绍了文学批评的方法和技巧,培养学生分析和鉴赏文学作品的能力。

备考建议1.熟悉教材内容:认真阅读所选教材,理解其中的重要观点和理论,掌握文学发展史和文学理论的核心知识。

2.扩展阅读:除了教材,考生还可以阅读相关的文学作品、评论和研究资料,拓宽自己的文学视野和知识面。

3.做笔记总结:在学习过程中,及时做好笔记和总结,整理出重要的概念和观点,方便日后复习和回顾。

4.制定学习计划:根据自身的时间安排和学习进度,制定合理的学习计划,保证每个章节都有足够的时间进行深入学习和思考。

5.划重点和重点突破:根据考试大纲,划出重点内容,并加强对这些内容的学习和理解。

同时,关注一些常考的题目类型和解题技巧,进行有针对性的突破。

6.多做练习题:通过做题,巩固所学知识,培养解题思路和分析能力。

可以找一些历年真题或模拟题进行练习,提高应试能力。

总结在2024年自考文学概论课程的教材选择和备考建议中,考生应选择合适的教材,全面了解中国文学和西方文学的发展史,并掌握相关的文学理论和批评方法。

文学理论必读书目(最新全面)

文学理论必读书目(最新全面)《文学理论》阅读书目一,理论著作1.【美】M·H·艾布拉姆斯《镜与灯——浪漫主义文论及批评传统》,郦稚牛等译,北京大学出版社,2004年第一版.2.【美】韦勒克,沃伦《文学理论》,刘象愚等译,三联书店,1984年第一版.3.钱钟书《谈艺录》,中华书局,1984年第一版.4.海德格尔《诗·语言·思》,彭富春译,文化艺术出版社,1991年第一版.5.伍蠡甫《西方文论选》,上海译文出版社,1979年版.6.伍蠡甫《现代西方文论选》,上海译文出版社,1983年版.7.郭绍虞《中国文学批评史》,上海古籍出版社,1979年版.8.袁行沛《中国文学史》,高等教育出版社,1999年版.9.黑格尔《美学》,商务印书馆,1981年版.10.鲁迅《中国小说史略》,《鲁迅全集》,人民文学出版社1981年版.11.伊格尔顿《二十世纪西方文学理论》,伍晓明译,陕西师范大学出版社1986年版.12.宗白华《美学散步》,上海人民出版社.1981年版.13.王国维《人间词话》.14.韦恩·布斯《小说修辞学》,广西人民出版社1987年版15.弗吉尼亚·沃尔夫《论小说与小说家》,上海译文出版社1986年版16.康德:《判断力批判》,商务印书馆1987年版17.英伽登:《文学的艺术作品》,《二十世纪西方美学名著选》下,复旦大学出版社1988年18.苏珊·朗格:《情感与形式》,中国社会科学出版社1986年版.19.朱光潜:《朱光潜美学文集》,上海文艺出版社1982年版.20.索绪尔:《普通语言学教程》,商务印书馆1980年版.21.佛斯特:《小说面面观》,花城出版社1981年版.22.高尔基:《论文学》,人民文学出版社1978年版.23.亚里士多德:《诗学》,人民文学出版社1962年版.24.《文心雕龙》(梁·刘勰)二,精品教材1.童庆炳主编《文学理论教程》高等教育出版社1998年版2.刘安海,孙文宪主编《文学理论》,武汉华中师大出版社1999年版3.王耀辉《文学文本解读》武汉华中师大出版社1999年版4.王先沛主编《文学批评原理》武汉华中师大出版社1999年版三,专业刊物1.文学评论2.文艺理论研究3.当代作家评论4.人大复印资料·文艺理论。

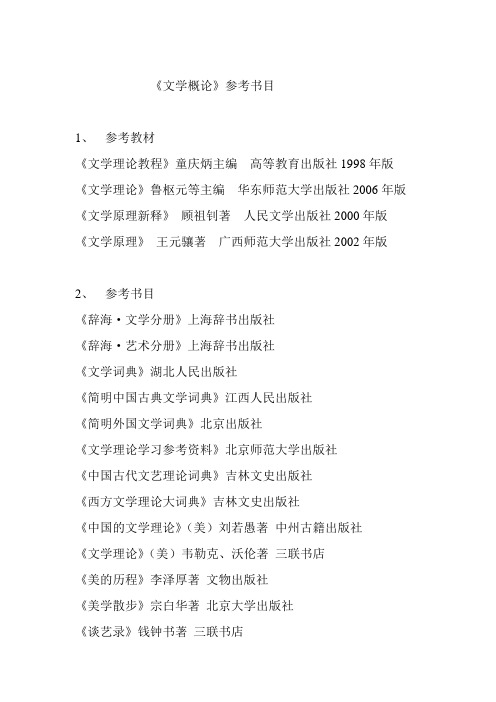

《文学概论》参考书目

《文学概论》参考书目1、参考教材《文学理论教程》童庆炳主编高等教育出版社1998年版《文学理论》鲁枢元等主编华东师范大学出版社2006年版《文学原理新释》顾祖钊著人民文学出版社2000年版《文学原理》王元骧著广西师范大学出版社2002年版2、参考书目《辞海·文学分册》上海辞书出版社《辞海·艺术分册》上海辞书出版社《文学词典》湖北人民出版社《简明中国古典文学词典》江西人民出版社《简明外国文学词典》北京出版社《文学理论学习参考资料》北京师范大学出版社《中国古代文艺理论词典》吉林文史出版社《西方文学理论大词典》吉林文史出版社《中国的文学理论》(美)刘若愚著中州古籍出版社《文学理论》(美)韦勒克、沃伦著三联书店《美的历程》李泽厚著文物出版社《美学散步》宗白华著北京大学出版社《谈艺录》钱钟书著三联书店《中国美学史大纲》叶郎著北京大学出版社《中国艺术精神》徐复观著春风文艺出版社《中国文学精神》徐复观著上海书店出版社《中国文学理论发展史》张少康著北京大学出版社《中国诗学》叶维廉著三联书店《中国文学批评史略》滕福海著吉林人民出版社2002年《西方文论选》伍蠡甫主编上海译文出版社《西方美学史》朱光潜著上海文艺出版社《当代西方文艺理论》朱立元著华东师范大学出版社《外国文学评论选》湖南人民出版社《诗学》亚里士多德著商务印书馆《诗艺》贺拉斯著人民文学出版社《拉奥孔》莱辛著人民文学出版社《汉堡剧评》莱辛著人民文学出版社《歌德谈话录》人民文学出版社《美育书简》席勒著中国文联出版公司《美学》黑格尔著商务印书馆《判断力批判》康德著商务印书馆《艺术哲学》丹纳著商务印书馆《十九世纪文学主潮》勃兰兑斯著《发生认识论原理》(瑞士)皮亚杰著商务印书馆《艺术的起源》(德)格罗塞著商务印书馆《罗丹艺术论》葛赛尔著人民日报出版社2000版《法国作家论文学》三联书店《十九世纪英国文论选》人民文学出版社《别林斯基选集》(一、二、三卷)上海译文出版社《车尔尼雪夫斯基论文学》(上、中、下卷)上海译文出版社《杜勃罗留波夫选集》(第一、二卷)上海译文出版社《普列汉诺夫美学论文集》(Ⅰ.Ⅱ集)人民出版社《论文学》高尔基著人民出版社《契珂夫手记》浙江人民出版社1982年版《现代西方文论选》伍蠡甫主编上海译文出版社1983年版《二十世纪西方现代文论述评》张隆溪三联出版社《精神分析引论》弗洛伊德著商务印书馆《艺术与视知觉》阿思海姆中国社会科学出版社1984年《美感》(美)乔治.桑塔耶纳著中国社会科学出版社《艺术问题》(美)苏珊.朗格著中国社会科学出版社《艺术即经验》(美)约翰.杜威著中国社会科学出版社《符号学美学》(法)R.巴特著辽宁文艺出版社《接受美学与接受理论》(德)姚斯.(美)霍拉勃辽宁文艺出版社《存在主义美学》(日)今道友信著辽宁文艺出版社《真理与方法》(德)H.G伽达默尔著辽宁文艺出版社《抽象与移情》(德)W.沃林格著辽宁文艺出版社《人的潜能和价值》(美)马斯洛著华夏出版社《第三思潮:马斯洛心理学》(英)弗兰克.戈布尔著上海译文出版社《结构主义和符号学》(英)特伦斯.霍克斯著上海文艺出版社《读者反应批评:理论与实践》(美)斯坦利.费什著中国社会科学出版社《作品.文学史与读者》(德)瑙曼著文化艺术出版社《艺术》(英)克莱夫.贝尔著中国文联出版公司《走向科学的美学》(美)托马斯.门罗著中国文联出版公司《小说修辞学》(美)韦思.布斯著广西人民出版社《现代小说美学》(美)利昂.塞米利安著陕西人民出版社《小说面面观》(英)佛斯特花城出版社《当说者被说的时候》比较叙述学导论赵毅衡著中国人民大学出版社《艺术形态学》(苏)列.谢.维戈茨基著上海文艺出版社《艺术类型学》李心峰主编文化艺术出版社《艺术心理学》(苏)莫.卡冈著三联书店《艺术社会学》(匈)阿诺德.豪泽尔著学林出版社《艺术与宗教》(苏)乌格里诺维奇著三联出版社《艺术与科学》(苏)米.贝京著文化艺术出版社《文艺伦理学论纲》赵红梅戴茂堂著中国社会科学出版社《法律与文学》苏力著三联书店《文学批评原理》(英)艾.阿.瑞恰慈著百花洲文艺出版社《批评的概念》(美)雷内.韦勒克著中国美术学院出版社《批评的剖析》(美)弗赖著百花洲文艺出版社《比较文学》陈、孙景尧、谢天振主编高等教育出版社《比较诗学》(美)厄尔.迈纳著中央编译出版社《悲剧的诞生—尼采美学文选》三联书店《裸体艺术论》陈醉著文化艺术出版社.。

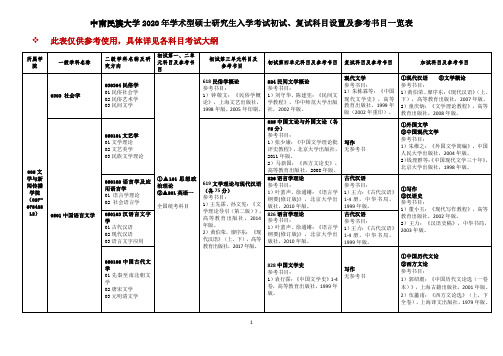

此表仅供参考使用,具体详见各科目考试大纲

2012 年版。

语言学理论

参考书目:

1)叶蜚声、徐通锵:《语 言学纲要(修订版)》,北京 大学出版社,2010 年版。

①社会语言学 ②汉语史 参考书目: 1)刘宝俊:《社会语言 学》,科学出版社,2016 年版。 2)王力:《汉语史稿》, 中华书局,2003 年版。

说明: 1.用▲标注的,为全国统考或联考科目。 2.第一单元考试科目为 101-思想政治理论(工商管理硕士、公共管理硕士为“▲199-管理类联考综合能力)。 3.第二单元考试科目为 204-英语二,(法律硕士(法学)、法律硕士(非法学)为 201-英语一,翻译硕士各领域为 211 翻译硕士)。

2008 年。

论》(第六版),复旦大 告学概论》,高等教育出版社, 2017 年。

2)高卫华:《新闻传播学导论》,武

学出版社,2018 年。

2018 年。

3)谢新洲:《媒介经 汉大学出版社,2011 年版。 营与管理》,北京大

学出版社,2011 年。

新闻传播史+媒介理

论与实务

620 新闻与传播理论

832 传播实务研究

中南民族大学 2020 年学术型硕士研究生入学考试初试、复试科目设置及参考书目一览表

此表仅供参考使用,具体详见各科目考试大纲

所属学 院

一级学科名称

0303 社会学

005 文 学与新 闻传播

学院 (027678428

12)

0501 中国语言文学

二级学科名称及研 究方向

030304 民俗学 01 民俗社会学 02 民俗艺术学 03 民间文学

民大学出版社,2011 年。 年。

2)程曼丽:《外国新 论》(第二版),清华大学出版社,

2)李良荣:《新闻学概