水青科室会幻灯P3-Bacterial Vaginosis,Atopobium vaginae and Nifuratel

腔肠动物和扁形动物-2022年学习资料

繁殖方式-出芽生殖-群体生活的-种类,芽体-不离开母体-而形成一个-复杂的群体。

水螅的运动-借助触手和身体弯曲作尺蠖样运动或翻筋斗运动。-图5-5水螅的运动(甘刘凌云)-1.收指:2.伸 :3…7.翻筋斗运动:8…0.尺蠖样运动;-1】-12,俏粘液气泡上升及漂动

Hale Waihona Puke 珊瑚虫腔肠动物和扁形动物PPT课件

扁形动物身体扁平,身体是由内胚层、-中胚层、外胚层三个胚层形成的,由于中-胚层形成了肌肉层,是扁形动物的运 能-力比腔肠动物强。消化道有口无肛门,虽-然组织、器官、系统有了进一步的分化,-但仍没有呼吸系统和循环系统 所以,扁形动物中像涡虫这样自由生活的种-类很少,大多数扁形动物寄生在人和动物体-内。-24

hp水6/B腔肠动物和扁形动物PPT课件

第一节-腔肠动物和扁形动物-2

学习目标-1、识别腔肠动物、扁形动物。-2、概述腔肠动物和扁形动物的主要特征及-它们与人类的关系。-3、初 形成动物体的形态结构、生理机能-及生活习性与其生活环境相适应的基本生-物学基-4、养成良好的生活卫生习惯。

腔肠动物代表动物一水螅-水螅的生活环境-水螅生活在淡水中,通-常会固着在水草上,身-体浅褐色,体长约1cm

30腔肠动物和扁形动物PPT课件

猪肉绦虫病的预防措施-预防猪肉绦虫病,要搞好粪便管-理;加强猪的检疫和市场管理,对-“米猪肉”严加处理;注 饮食卫-生。-31

Schistosoma japcnicum-Male and famale incopue-Female0m-血吸虫-32

日本血吸虫-1、危害:血吸虫病,肝脾肿大、腹水、丧失劳动力,死亡-2、寄生部位:哺乳动物的门静脉和肠系膜静 ;-3、中间宿主:钉螺-4、感染状态:尾蚴-合抱的成虫-雄虫长12~20mm,-腹吸盘以下虫体向两侧-延展 并向腹面卷曲,-形成抱雌沟,雌虫前细-后粗,形似线虫,体长-20~25mm,常居于抱-雌沟内。而且只有通过 合抱,成虫才能顺利发-育成熟。-33

水处理生物学ppt课件

应用: 一般不作应用

精选编辑ppt

11

(2)以活细菌重量变化绘制的生长曲线 生长率上升阶段(对数生长阶段) 适应期、对数期 初:菌体个数不增加,菌体体积增大 后:生长率达最高,分解速率最大。 食料:供 〉求

精选编辑ppt

膜不让细菌流出。滤菌。将膜放在固体培养基表面 培养。计数类似平板计数法。

精选编辑ppt

4

(3)重量法 测定细胞干重 离心法,过滤法。 105℃~110℃干燥。 水处理构筑物内细菌生长量常采用该法。 做法:取一定体积的待测污泥样品,放于蒸发皿中

干燥,然后称重。 活性污泥法中采用的指标是混合液悬浮固体

的温度下培养,并定时取样测定活细菌的数目和重量的 变化,以活细菌个数的对数或活细菌重量为纵坐标,以 培养时间为横坐标作图,所得的曲线即为细菌的生长曲 线。

这种培养方式为间歇培养或分批培养。

精选编辑ppt

6

(1)以活细菌数目的对数绘制的生长曲线 适应期 对数期 稳定期 衰亡期

精选编辑ppt

7

适应期(缓慢期) lag phase 特点:

初:细菌数目不增加,体积增长快。 后:个别菌体繁殖,个数少许增加。 曲线平缓。大量诱导酶的合成。

应用: 缩短此期,提高设备利用率 用处于对数期的活性污泥接种

精选编辑ppt

8

对数期 log phase 特点:

分裂快,数目增多; 活菌数 ≈总菌数; 曲线直线上升。 此时细胞的大小、组成、生理特征等均趋于一 致,代谢活跃,生长速率高,代时稳定。 应用: ➢ 接种用的好种子 ➢ 代谢、生理研究的好材料

14

三、细菌的生长曲线和废水生物处理的关系 (1)大多数活性污泥处理系统运行范围是:

水处理微生物学(第十讲)PPT课件

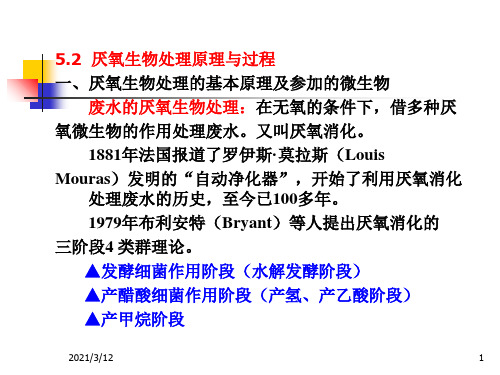

2021/3/12

14

五、厌氧法处理废水的应用 主要用于处理城市废水厂的污泥和固体含量很高的

废水。 厌氧消化池→沼气 、稳定性好的腐殖质。 污泥体积减少1/2以上。

2021/3/12

浮盖式消化池

15

六、厌氧颗粒污泥的形成及影响因素 (1)污泥颗粒化的定义

在上流式厌氧污泥床(UASB)反应器内,厌氧污 泥可以以絮状的聚集体(絮状污泥)或直径 0.5 ~ 6.0mm 的球形、椭球形颗粒污泥形态存在。

2021/3/12

12

四、厌氧法处理废水的特征 (1)处理对象:有机污泥和高浓度的有机废水。 ① 有机污泥:不溶性有机质、纤维素含量高的污水; ② 高浓度有机废水:一般先厌氧处理将污物,后好氧处理。 大量稀释或降低好氧处理进水量,则处理费用较昂贵。 (2) 时间长:30~35℃ ,需1~5天。

BOD去除率 50~90%。 (3) 能量需求大大降低:不需供氧气,同时还可产生甲烷。

污泥颗粒化:在厌氧反应器内颗粒污泥形成的过程。 颗粒污泥的形成可以使 UASB 内保留高浓度的厌氧 污泥,它是大多数 UASB 反应器启动的目标和启动成功 的标志。

原理:

H2、CO2、3COOH

CH3NH2、CH3OH → CH4

参加的微生物:

产甲烷细菌群:产甲烷杆菌属;

产甲烷短杆菌属;产甲烷球菌属。

特性

严格厌氧菌;中温菌对温度敏感;

pH 适宜6.8~7.2;增殖速率慢。

2021/3/12

4

废水中有机物

Ⅰ

↓ 发酵性细菌

脂肪酸(丙酸、丁酸)、醇类

Ⅱ

↓ 产氢产乙酸细菌

2021/3/12

7

三、厌氧废水处理的影响因素 (1)温度

水处理生物学真核PPT学习教案

(1)无机营养:

叶绿素 CO2+H2O 光合作用 [CH2O]+O2

藻类多的池塘

白天溶解氧过饱和 夜晚溶解氧低。

第42页/共66页

(2)各种藻类的主要特性 绿藻:春夏之交、秋季生长旺。微碱环境生活。 引起水体富营养化。 硅藻:春夏两季、冬季生长旺,有的能发出鱼腥气。 金藻:其中的黄群藻能发出臭味,水发苦。

。 (3)>2000 “标准面积单位” ,有明显的臭味。 含有黄群藻的水不宜饮用。

第45页/共66页

2 排水工程:

大量繁殖,会造成富营养化污染。

N、P是藻类生长的关键元素。 含N、P合成洗涤剂

的水引起水体富营养化,需深度处理!

污水养殖藻类: (1)收获有营养价值的藻类(螺旋藻) 。

(2)净化污水。

一 藻类的形态及生理特性

按形态构造、色素组成分10纲。

蓝藻(讲过) 绿藻 硅藻 裸藻 金藻

褐藻 甲藻 轮藻 红藻 黄藻

第38页/共66页

1 形态

几

种

绿

藻

栅列

藻

盘星藻

小球 藻

第39页/共66页

衣 藻

几

种

硅 藻

鼓藻

隔板硅藻

旋星第硅40页藻/共66页

新月藻

几 种 金 藻

第41页/共66页

2 生理特性

特征: 1. 个体一般以单细胞状态存在; 2. 多数营出芽生殖,有的裂殖; 3. 能发酵糖类产能; 4. 细胞壁常含有甘露聚糖; 5. 喜在含糖量较高、酸度较大的水生环境中生长。

分布:偏酸性的含糖环境。水果、蔬菜、蜜饯的表面,果园 土壤中与环境有关。

种类:据1982年的资料,已知的酵母有56属,500多种。酵 母菌与人类的关系极其密切。

《水生生物学硅藻门》PPT课件

44

D、假壳缝: 壳面上无壳缝,仅在

壳面中央或偏壳面一侧 有纵向无纹平滑区。

E、管壳缝: 为1条纵走或围绕着壳

缘的管沟,以极狭的裂 缝与外界相通,以小孔 与内部相通。

完整版课件ppt

45

完整版课件ppt

46

2.原生质体:

(1)色素:叶绿素a、c和β—胡萝卜素, 还具有岩藻黄素和硅藻黄素。

(2)颜色:黄褐色、黄绿色 (3)色素体:1—多个,盘状、板状、分

完整版课件ppt

53

四、硅藻的生态分布和意义

• 该门大约有1600种。

• 淡海水中都有分布,为海水中的主要藻类。

• 分布广,喜在较低温的硬水水体中生活, 营浮游、底栖或着生,在岩石、墙、树皮 上也能附生,在干燥处以休眠状态渡过旱 季,在热带的潮湿地区与蓝藻共生。春秋 两季出现高峰,在水温60℃温泉中某些硅 藻能正常生长、繁殖。

1.壳面有壳缝、假壳缝、管壳缝;

2.壳缝或假壳缝的两侧有细点连成的横纹;

3.壳面一般就有中央节和极节。

此纲分5个目:无壳缝目(假壳缝目)、 短壳缝目、双壳缝目、单壳缝目、管壳缝 目。

完整版课件ppt

38

二、体制及细胞形状

• 单细胞:大多数为单细 胞种类。

• 群体:

• 圆柱形、鼓形、圆盘形、

小盒形、线形、披针形、

枝状、颗粒状、星状等。 (4)贮存物质:油滴(脂肪) (5)细胞核:1个,通常位于细胞中央。

完整版课件ppt

47

三、繁殖

1.营养生殖(细胞分裂):

硅藻最普遍的一种繁殖方式;一般在夜间 进行,开始时原生质略膨大,然后核进行 分裂,原生质也一分为二;两核同时分别 靠近上下两壳,每一半壳各自长出一个新 的下壳,形成新个体,刚形成壳薄,以后 逐渐增厚,直至与母壳相等为止。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

36 Current Clinical Pharmacology, 2012, 7, 36-401574-8847/12 $58.00+.00© 2012 Bentham Science PublishersBacterial Vaginosis, Atopobium vaginae and NifuratelFranco Polatti *Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Policlinico San Matteo, University of Pavia, Pavia, ItalyAbstract: As bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a potential cause of obstetric complications and gynecological disorders, there issubstantial interest in establishing the most effective treatment. Standard treatment - metronidazole or clindamycin, by either vaginal or oral route – is followed by relapses in about 30% of cases, within a month from treatment completion. This inability to prevent recurrences reflects our lack of knowledge on the origins of BV. Atopobium vaginae has been recently reported to be associated with BV in around 80% of the cases and might be involved in the therapeutic failures. This review looks at the potential benefits of nifuratel against A. vaginae compared to the standard treatments with metroni-dazole and clindamycin. In vitro, nifuratel is able to inhibit the growth of A. vaginae , with a MIC range of 0.125-1 g/mL; it is active against G. vaginalis and does not affect lactobacilli. Metronidazole is active against A. vaginae only at very high concentrations (8-256 g/mL); it is partially active against G. vaginalis and also has no effect on lactobacilli. Clindamycin acts against A. vaginae with an MIC lower than 0.125 g/mL and is active on G. vaginalis but it also affects lactobacilli, altering the vaginal environment. These observations suggest that nifuratel is probably the most valid thera-peutic agent for BV treatment.Keywords: Antibiotic resistance, Atopobium vaginae, bacterial vaginosis, nifuratel, review. BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS Epidemiology and PathogenesisBacterial vaginosis (BV) is one of the most frequent female lower genital tract infections, not only in pregnancy but throughout the reproductive life. Studies from Europe and the USA have found prevalence between 4.9% and 36.0% [1]. The first signs of BV are radical changes in the vaginal ecosystem. H 202-producing lactobacilli, which are present in 96% of women with normal vaginal bacterial flora, are markedly reduced or lost, while microorganisms like Gardnerella vaginalis and obligate anaerobes prevail [2]. The cause of this change is not clear [3] and the microorganisms responsible for the shift in the flora have still to be identified [4]. BV may be due not only to the excessive bacterial growth, but also to the formation of a dense bacterial biofilm adherent to the vaginal mucosa.Which is the Role of the Biofilm?The biofilm formed by Gardnerella vaginalis in BV was first identified by electron microscopy as a dense tissue strongly adherent to the vaginal epithelium, and made up of bacterial cells packed inside a network of polysaccharide fibrils [5, 6]. Later, Swidsinki et al ., investigating vaginal biopsies by bacterial rDNA fluorescent in situ hybridization, suggested that the bacterial biofilm played a primary role in the development of BV [7].*Address correspondence to this author at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Policlinico San Matteo, University of Pavia, Piazzale Golgi 2, 27100 Pavia, Pavia, Italy; Tel: +39 524309; Fax: +39 524309; E-mail: polattif@libero.it Costerton et al . and Swidsinki et al . found a dense bacte-rial biofilm, coating at least half the epithelial surface, in 90% of biopsies from women with BV, and in only 10% of healthy women [7, 8]. The presence of the biofilm enables the bacterial cells to reach higher concentrations (up to 1011 bacteria/mL) than in vaginal fluid and boosts their resistance to both the host immune system and the antimicrobials [9, 10]. In fact, the drugs hardly reach the bacteria, residing inside the film in a quiescent state, leading to an up to 1000-fold antimicrobial decreased activity [9, 11]. This observa-tion might provide an explanation of the high rates of BV relapses [10, 12]. Complications of BVBV has aroused interest in the last few years being con-sidered as a predisposing factor for HIV, Type II Herpes symplex virus, Chlamydia trachomatis infections, as well as for trichomoniasis and gonorrhea [13, 14]; BV can be also a cause for complications like late abortion [15], premature rupture of the amniotic membrane [16], chorio-amnionitis [17], post-partum endometritis [18, 19, 20], and failure of in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer [13, 14]. Particular attention has been recently paid to Atopobium vaginae , a newly identified bacterium, belonging to the Coriobacte-riaceae family, which is believed to be at least a partial cause of the above mentioned complications [13]. The genus Atopobium , described for the first time in 1992, includes bacteria previously classified as lactobacilli. Rodriguez first identified A. vaginae in a study on vaginal lactobacilli [21]. A. vaginae 16s rRNA gene differs from the other species belonging to Atopobium genus by approximately 3-8% [22, 23]; this enabled Rodriguez to identify it as a new species. The isolate can be distinguished from A. minutum, A. parvulum,Bacterial Vaginosis, Atopobium vaginae and Nifuratel Current Clinical Pharmacology, 2012, Vol. 7, No. 1 37and A. rimae by biochemical tests and protein electrophoresis of the whole cell (Table 1). Gram stain shows A. vaginae as a small coccus, rounded or oval, or rods, visible as single cells, in pairs or in short chains (Fig. 1).Fig. (1). A) Grey-white colonies of A. vaginae after 48h culture in anaerobic conditions. B) Gram staining shows Gram-positive bacte-ria, with A. vaginae visible as single cells, in pairs or short chains. Geissdorfer et al. 2003 [41].This aerobic facultative, gram-positive bacterium cannot be easily isolated by classical microbiological methods [14, 24]. It is hardly detected in healthy women vaginal fluid but is commonly found in the vagina of patients with BV: 50% according to Burton [25, 26], 70% according to Ferris [27], and more than 95% according to Verhelst et al. [24] and Verstraelen et al. [28]. In symptomatic BV it has been de-tected together with Gardnerella vaginalis in the biofilm adherent to the vaginal mucosa [24]. This was confirmed by Swidsinski et al. [7] who, by examining the composition and structural organization of the biofilm, found that Gardnerella vaginalis accounted for 60-95% of the film mass. In addition, in 70% of bioptic samples, Atopobium vaginae accounted for the 1-40% of the film mass. Lactobacillus concentrations were lower than 106 CFU/mL, making up only 5% of the biofilm (Fig. 2).TherapyConcerning the pharmacological therapy, CDC recom-mends either oral or topical (vaginal gel) metronidazole once a day for 5 days as first choice for BV. Efficacy is compara-ble to topical clindamycin [29]. Cure rates, following intrav-aginal treatment with metronidazole or clindamycin, account for 80-90% at the end of treatment and one month after the end of therapy [13, 14, 30]. However, three months after the end of therapy the rate of relapses can overcome 30%. Persistence of an adherent bacterial biofilm, containing mostly G. vaginalis and A. vaginae, seems to be the main reason for failure of BV treatment [30]. Suppressive treat-ment with metronidazole gel and physiological approaches (use of probiotics or acidifying) have been investigated with variable results [31]. Moreover, long-term treatment with metronidazole is not recommended because of the high incidence of gastrointestinal adverse reactions, the risk of peripheral neuropathy, and Candida super infection [32].Table 1. Biochemical Tests to Distinguish A. vaginae from the other Atopobium SpeciesEnzyme A. vaginae A. minutum A. parvulum A. rimaeAcid phosphatase + - + +Alanine arylamidase - - + -Arginine dihydrolase + + - -Argininearylamidase+ + + - Histidine arylamidase + - - --Galactosidase - - + - Leucinearylamidase+ + - - Prolinearylamidase+ + - - Pyroglutamic acid arylamidase - v + +Glycine arylamidase + - + -Serine arylamidase + - - -Thyroxinearylamidase- - + -+, the enzyme is expressed constitutively;-, the enzyme is absent and cannot be induced; v, expression of the enzyme is variableModified, from Rodriguez et al. 1999 [21].AB38 Current Clinical Pharmacology, 2012, Vol. 7, No. 1 Franco PolattiAntibiotic SensitivityFailures with metronidazole in patients with recurrent or persistent BV [33, 34] might conceivably reflect the newly found mechanism of formation of a biofilm containing G. vaginalis together with A. vaginae [7, 9, 13, 28] (Fig. 3). The fact that A. vaginae is resistant to metronidazole, and that the bacterium creates a biofilm in which it is associatedwith G. vaginalis, complicates the response to the antibiotic [9, 13, 28]. Though clindamycin is more active than metron-idazole against both G. vaginalis and A. vaginae , its negative effects on lactobacilli leave the way open to microbial disor-ders that can cause frequent super infections and recurrences. Moreover, an increasing resistance to antibiotics that act like clindamycin, by blocking protein synthesis has been reported.A randomized prospective trial compared 119 womenassigned to two therapeutic regimens for BV: either metroni-dazole vaginal gel for five days, or clindamycin vaginal tab-lets for three days. The clinical efficacy was comparable in the two arms: after 7-12 days about 80% of the patients were cured, but this percentage fell down to about 50% after 35-45 days. Following clindamycin treatment – but not metron-idazole - there was a steep rise in the percentage of women with at least one clindamycin resistant strain isolated. Moreover, 70-90 days after the end of treatment, about 80% of the women who received clindamycin presented in their vaginal swabs anaerobic bacteria resistant to that drug [35]. Togni et al . [36] compared the in vitro susceptibility of A. vaginae to nifuratel, metronidazole and clindamycin. Sus-ceptibility to metronidazole was variable, with MIC ranging from 8 to 256 g/mL. Nifuratel and clindamycin inhibited the growth of all the tested strains, with MIC from 0.125 to 1 g/mL and below 0.125 g/mL, respectively (Table 2). The findings related to metronidazole and clindamycin are in line with previously published studies [37].Table 2. MIC Ranges ( g/mL) and MIC 50 ( g/mL) ofMetronidazole, Clindamycin and Nifuratel against Atopobium vaginaeAntimicrobial Agent MIC Range ( g/ml) MIC 50 ( g/ml)Metronidazole 8 - 256 32 Clindamycin < 0.125 < 0.125 Nifuratel0.125 - 10.5Togni et al . 2011 [30].In the same study, the activity of these antibiotics was assayed on lactobacilli and G. vaginalis . Either nifuratel and metronidazole did not affect the normal lactobacterial flora, while clindamycin inhibited all tested strains of lactobacilli. Nifuratel and metronidazole were both highly active against G. vaginalis (Fig. 4). The susceptibility of Atopobium vaginae to metronidazole and clindamycin, and the action on lactobacilli and G. vaginalis were in line with previous reports [37-39]. To summarise, nifuratel was active against A. vaginae and G. vaginalis strains without affecting lacto-bacilli; metronidazole was active against A. vaginae, but only at very high concentrations, partially active against G. vaginalis, and did not affect lactobacilli; clindamycin was extremely effective against A. vaginae and G. vaginalis, but it also affected the lactobacilli, altering the vaginal ecosystem. CONCLUSIONSThe discovery of the presence of Atopobium vaginae in the vaginal ecosystem improves the basic understanding ofFig. (2). These microscopy images (A ,B ,C ) show an unbroken Gardnerella vaginalis biofilm completely coating the vaginal epi-thelium. The lower panels show the same microscopic field (Ca ) in dark-red fluorescence and (Cb ) in orange fluorescence. Lactoba-cilli, interwoven with G. vaginalis in the film, only account for 5% of the bacterial population. Swidsinki et al . 2005 [7].Fig. (3). Microscopic images of the biofilm during and after treat-ment with metronidazole. A ) Bacterial biofilm (x 400) in a patient at the third day of metronidazole therapy. The film is thin. B ) Bacterial biofilm (x 400) in the same patient on day 35. The film has reformed almost completely. Swidsinki et al . 2008 [9].ABBacterial Vaginosis, Atopobium vaginae and Nifuratel Current Clinical Pharmacology, 2012, Vol. 7, No. 1 39the pathogenesis of BV [28]. This bacterium is presumably the main reason for failures or recurrences after BV treat-ment with metronidazole, since it is found in 80-90% of cases of relapse [40]. Prospective studies are now needed to show whether metronidazole–resistant microorganisms, such as Atopobium vaginae, are involved in recurrences. Informa-tion to date suggests that nifuratel is probably the most valid therapeutic agent for BV, as it is highly active against Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae, without affecting lactobacilli which are fundamental for the system health and balance [30].CONFLICT OF INTERESTDeclarednone.ACKNOWLEDGEMENTDeclarednone.REFERENCES[1]Morris M, Nicoll A, Simms I, Wilson J, Catchpole M. Bacterialvaginosis: a public health review. BJOG 2001; 108: 439-50.[2]Nam H, Whang K, Lee Y. Analysis of vaginal lactic acid producingbacteria in healthy women. J Microbiol 2007; 45: 515-20.[3]Cauci S, Monte R, Driussi S, Lanzafame P, Quadrifoglio F.Impairment of the mucosal immune system: IgA and IgM cleavagedetected in vaginal washing of a subgroup of patients with bacterialvaginosis. J Infect Dis 1998; 178: 1698-1706.[4]Sobel JD. Bacterial vaginosis. Annu Rev Med 2000; 51: 349-56.[5]van der Meijden WI, Koerten H, van Mourik W, de Bruijn WC.Descriptive light and electron microscopy of normal and clue-cell-positive discharge. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1988; 25: 47-57.[6]Scott TG, Curran B, Smyth CJ. Electron microscopy of adhesiveinteractions between Gardnerella vaginalis and vaginal epithelialcells, McCoy cells and human red blood cells. J Gen Microbiol1989; 135: 475-80.[7]Swidsinki A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, Ladhoff A,Swidsinki S, Hale LP, Lochs H. Adherent biofilms in bacterialvaginosis. Obstet Gynecol 2005; 106: 1013-23.[8]Costerton W, Veeh R, Shirtliff M, Pasmore M, Post C, Ehrlich G.The application of biofilm science to the study and control ofchronic bacterial infections. J Clin Invest 2003; 112: 1466-77. [9]Swidsinki A, Mendling W, Loening-Baucke V, Swidsinski S,Dörffel Y, Scholze J, Lochs H, Verstraelen H. An adherentGardnerella vaginalis biofilm persists on the vaginal epitheliumafter standard therapy with metronidazole. Am J Obstet Gynecol2008; 198: 97.e1-6.[10]Hay P. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2000; 2:506-12. [11]Hoiby N, Bjarnsholt T, Givskov M, Molin S, Ciofu O. Antibioticresistance of bacterial biofilms. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010; 35:322-32.[12]Pirotta M, Fethers KA, Bradshaw CS. Bacterial vaginosis - Morequestions than answers. Aust Fam Physician 2009; 38: 394-7. [13]Fredricks DN, Fiedler TL, Marrazzo JM. Molecular identificationof bacteria associated with bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med 2005;353: 1899-911.[14]Livengood CH. Bacterial vaginosis: an overview for 2009. RevObstet Gynecol 2009; 2: 28-37.[15]Donati L, Di Vico A, Nucci M, Quagliozzi L, Spagnuolo T,Labianca A, Bracaglia M, Ianniello F, Caruso A, Paradisi G.Vaginal microbial flora and outcome of pregnancy. Arch GynecolObstet 2010; 281: 589-600.[16]McDonald HM, Brocklehurst P, Gordon A. Antibiotics for treatingbacterial vaginosis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev2007; 24 (1): CD000262.[17]Fahey JO. Clinical management of intra-amniotic infection andchorioamnionitis: a review of the literature. J Midwifery Women’sHealth 2008; 53: 227-35.[18]Hillier SL; Kiviat NB; Hawes SE, Hasselquist MB, Hanssen PW,Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Role of bacterial vaginosis-associated microorganisms in endometritis. Am J Obstet Gynecol1996; 175: 435-41.[19]Sweet RL. Role of bacterial vaginosis in pelvic inflammatorydisease. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20: S271-5.[20]Pellati D, Mylonakis I, Bertoloni G, Fiore C, Andrisani A, AmbrosiniG, Armanini D. Genital tract infections and infertility. Eur J ObstetGynecol Reprod Biol 2008; 140: 3-11.[21]Rodriguez Jovita M, Collins MD, Sjoden B, Falsen E. Characteri-zation of a novel Atopobium isolate from the human vagina: de-scription of Atopobium vaginae sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1999;49: 1573-76.[22]Collins MD, Wallbanks S. Comparative sequence analysis of the16s rRNA genes of Lactobacillus minutus, Lactobacillus rimae andStreptococcus parvulus: proposal for the creation of a new genusAtopobium. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1992; 74: 235-40.[23]Stackebrandt E, Ludwig W. The importance of using outgroupreference organisms in phylogenetic studies: the Atopobium case.Syst Appl Microbiol 1994; 117: 3943.[24]Verhelst R, Vestraelen H, Claeys G, Verschraegen G, DelangheJ, Van Simaey L, De Ganck C, Temmerman M, VaneechoutteM. Cloning of 16S rRNA genes amplified from normal anddisturbed vaginal microflora suggests a strong association betweenAtopobium vaginae, Gardnerella vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis.BMC Microbiol 2004; 4: 16.[25]Burton JP, Devillard E, Cadieux PA, Hammond JA, Reid G. Detec-tion of Atopobium vaginae in postmenopausal women: cultivation-independent methods warrants further investigation. J Clin Micro-biol 2004; 42: 1829-31.[26]Burton JP, Chilcott CN, Al-Qumber M, Brooks HJ, Wilson D,Tagg JR, Devenish C. A preliminary survey of Atopobium vaginaein women attending the Dunedin gynaecology out-patients clinic: isFig. (4). Activity of nifuratel, metronidazole and clindamycin on lactobacilli, Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae.40 Current Clinical Pharmacology, 2012, Vol. 7, No. 1Franco Polattithe contribution of the hard-to-culture microbiota overlooked ingynaecological disorders? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2005; 45:450-2.[27]Ferris MJ, Masztal A, Martin DH. Use of species-directed 16S rRNAgene PCR primers for detection of Atopobium vaginae in patientswith bacterial vaginosis. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 5892-4.[28]Vestraelen H, Verhelst R, Claeys G, Temmerman M, VaneechoutteM. Culture-independent analysis of vaginal microflora: the unrec-ognized association of Atopobium vaginae with bacterial vaginosis.Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191: 1130-2.[29]Workwoski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control andPrevention. Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines 2010.Recommandation and Reports, December 17, 2010 59 (RR12);1-110.[30]Togni G, Battini V, Bulgheroni A, Mailland F, Caserini M,Mendling W. In vitro activity of nifuratel on vaginal bacteria:could it be a good candidate for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis?Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 2490-2.[31]Hay P. Recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Current Opinion in infectiousdiseases 2009; 22: 82-86.[32]Dickey LJ, Nailor MD, Sobel JD. Guidelines for the treatment ofbacterial vaginosis: focus on tinidazole. Ther Clin Risk Management2009; 5: 485-9.[33]Ferris DG, Litaker MS, Woodward L, Mathis D, Hendrich J.Treatment of bacterial vaginosis: a comparison of oral metronida-zole, metronidazole vaginal gel and clindamycin vaginal cream. JFam Pract 1995; 41: 443-9. [34]Larsson PG, Forsum U. Bacterial vaginosis: a disturbed bacterialflora and treatment enigma. APMIS 2005; 113: 305-16.[35]Fredricks DN, Fiedler TL, Thomas KK, Mitchell CM, MarrazzoJM. Changes in vaginal bacterial concentrations with intravaginalmetronidazole therapy for bacterial vaginosis as assessed by quanti-tative PCR. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47: 721-26.[36]Beigi RH, Austin MN, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Antimi-crobial resistance associated with the treatment of bacterial vagino-sis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 191: 1124-9.[37]De Backer E, Verhelst R, Vestraelen H, et al. Antibiotic susceptibi-lity of Atopobium vaginae. BMC Infect Dis 2006; 6: 51.[38]Goldstein EJ, Citron DM, Merriam CV, Warren YA, Tyrrell KL,Fernandez HT. In vitro activities of Garenoxacin (BMS 284756)against 108 clinical isolates of Gardnerella vaginalis. AntimicrobAgents Chemother 2002; 46: 3995-6.[39]Nagaraja P. Antibiotic resistance of Gardnerella vaginalis in recur-rent bacterial vaginosis. Indian J Med Microbiol 2008; 26: 155-7. [40]Hillier SL, Homes KK. Bacterial vaginosis, in Sexually Transmit-ted Diseases. Edited by Homes KK, Sparling PF, Mardh PA,Lemon SM, Stamm WE, Piot P and Wasserheit. New YorkMcGraw-Hill 1999; 563-86.[41]Geissdorfer W, Bohmer C, Pelz K, Schoerner C, Frobenius W,Bogdan C. Tubo-ovarian abscess caused by Atopobium vaginaefollowing transvaginal oocyte recovery. J Clin Microbiol 2003; 41:2788-90.Received: June 05, 2011 Revised: October 05, 2011 Accepted: October 20, 2011。