8法律 外文翻译 外文文献 英文文献 法律中的违约责任

关于合同违约的外文文献

关于合同违约的外文文献

对于合同违约的外文文献,我们可以从以下几个角度来进行全面的回答。

首先,我们可以从法律角度来探讨合同违约的外文文献。

在这方面,我们可以查阅美国法学期刊,如《Yale Law Journal》、《Harvard Law Review》等,这些期刊经常刊登关于合同法和违约责任的研究成果。

另外,英国的《Oxford Journal of Legal Studies》、澳大利亚的《Melbourne University Law Review》也是不错的选择。

这些期刊会有专家学者对合同违约案例进行深入分析,对合同法的理论进行探讨,对违约责任的认定进行讨论,对合同违约的救济措施进行研究等。

其次,我们可以从商业角度来研究合同违约的外文文献。

在这方面,可以查阅《Harvard Business Review》、《Journal of Marketing》等商业类期刊,这些期刊经常会有关于合同履行与违约的案例分析,对于商业合同中常见的违约行为进行探讨,对于合同管理与风险控制的实践经验进行分享等内容。

此外,还可以从经济学角度来研究合同违约的外文文献。

可以

查阅《The Quarterly Journal of Economics》、《The American Economic Review》等期刊,这些期刊会有关于合同理论、契约经济学、信息经济学等方面的研究成果,这些研究对于合同违约的成本、信息不对称下的合同履行问题等有着重要的启发作用。

总之,从法律、商业和经济等不同角度来研究合同违约的外文

文献,可以帮助我们全面了解合同违约的相关理论、案例和实践经验,对于解决实际合同纠纷、规避合同风险等具有重要的参考价值。

民法典对违约责任的规定

民法典对违约责任的规定违约责任是指当事人在合同履行过程中未按照合同约定的义务履行,引起对方遭受损失时,应当承担的法律责任。

根据《中华人民共和国民法典》(以下简称民法典)的相关规定,违约责任分为迟延履行、不履行和瑕疵履行三种情况,并对应有相应的法律后果。

一、迟延履行责任迟延履行责任是指当事人未能在约定期限内履行合同义务的情况。

根据民法典第169条的规定,债务人未按照合同约定的期限履行债务的,属于迟延履行。

债务人在迟延履行期间,应当向债权人支付迟延履行利息。

迟延履行利息的计算方法可以按照合同约定的利率计算,也可以依照法定利率计算。

此外,根据民法典第170条的规定,债务人迟延履行债务,造成债权人损失的,债务人应当承担赔偿责任。

债务人需赔偿的损失包括实际损失和合理支出两个方面。

实际损失是指债权人因债务人迟延履行行为所遭受的具体经济损失,如合同另有约定,则按照约定计算;合理支出是指债务人因追偿而发生的合理费用,如诉讼费用、律师费等。

二、不履行责任不履行责任是指当事人明确表示或者以其行为表明不能履行合同义务的情形。

根据民法典第171条的规定,当事人不履行合同义务,给对方造成损失的,应当承担不履行责任。

对于不履行责任,债权人有权选择请求债务人履行、请求债务人赔偿损失以及请求债务人支付违约金等多种救济方式。

其中,请求赔偿损失的救济方式是最为常见的。

债权人有权依照民法典第173条的规定,请求债务人支付由此造成的实际损失。

此外,根据民法典第176条的规定,债务人迟延履行或者不履行债务,情节严重的,债权人还可以请求支付违约金。

违约金是对当事人违约行为给对方造成的损失进行补偿的一种形式。

三、瑕疵履行责任瑕疵履行责任是指当事人在履行合同义务时,履行的结果与合同约定的要求不符合的情形。

根据民法典第154条的规定,当事人交付的标的物、提供的服务或者肖像权作品有瑕疵的,受益人可以选择要求修理、更换、退货、减少价款或者解除合同。

学术论文中的外文引用与翻译法律要求与规范

学术论文中的外文引用与翻译法律要求与规范引言学术研究是推动学科发展和知识进步的重要方式之一。

在学术论文中,外文引用与翻译是不可避免的环节。

然而,为了保证学术研究的严谨性和可信度,外文引用与翻译需要符合一定的法律要求与规范。

本文将探讨学术论文中外文引用与翻译的法律要求与规范。

一、外文引用的法律要求在学术论文中,外文引用是为了支持自己的观点和研究成果,增加论文的可信度和权威性。

然而,在外文引用时,需要遵守相关的法律要求,以避免侵权行为的发生。

首先,学术论文中的外文引用应遵循著作权法的相关规定。

根据著作权法,引用他人的作品需要符合合理引用的原则,即引用的范围、目的和方式不得超过合理范围,且必须标明出处。

因此,在学术论文中引用外文文献时,需要明确标注作者、文章标题、期刊名称、出版年份等信息,以确保引用的合法性。

其次,外文引用还需要考虑国际版权保护的相关规定。

在跨国引用外文文献时,需要关注目标国家的版权法律,以确保引用的合法性。

不同国家对版权的保护程度和要求可能存在差异,因此,学者在引用外文文献时需要对目标国家的版权法律有一定的了解,以避免侵权行为。

最后,学术论文中的外文引用还需要遵守学术道德的规范。

学术界强调学术诚信和知识的共享,因此,在引用外文文献时应尊重原作者的权益,不得进行恶意篡改或歪曲他人观点的行为。

同时,引用外文文献时应注重引用的准确性和完整性,避免断章取义或失真引用的情况发生。

二、外文引用的翻译规范在学术论文中,外文引用的翻译是将外文文献转化为读者所熟悉的语言,以便于理解和阅读。

为了确保翻译的准确性和一致性,外文引用的翻译需要遵守一定的规范。

首先,翻译应保持原文的准确性和完整性。

在翻译外文引用时,应尽量保留原文的意思和表达方式,不得随意添加、删除或修改原文的内容。

同时,翻译的语言应简明扼要,符合学术论文的风格和要求。

其次,翻译应注重语言的规范和准确性。

在翻译外文引用时,应遵循语法规则和词汇用法,确保翻译的语言通顺、准确。

违约责任的概念和原则

违约责任的概念和原则

违约责任是指当一方未履行合同义务,使得合同的履行受到影响或无法履行时,应承担的法律责任。

违约责任的原则包括以下几点: 1. 非履行方应承担损害赔偿责任:当一方未履行合同义务造成了对另一方的损失时,非履行方应承担损害赔偿责任,包括直接损失、间接损失和利润损失等。

2. 违约方应承担违约责任:当一方未履行合同义务时,应该承担相应的违约责任。

违约责任可以是履行责任、损害赔偿责任或者违约金等方式。

3. 追溯效力原则:违约责任的适用应当追溯到违约行为发生时,而非追溯到合同终止时或者起效时。

4. 等价交换原则:合同双方应当在合同中达成等价交换,即合同的价值应当相等。

当一方未履行合同义务时,应当承担对方所应得的价值。

5. 风险承担原则:在合同履行过程中,各方应当承担自己应当承担的风险。

当一方无法履行合同义务时,应当承担由此带来的风险和损失。

综上所述,违约责任的概念和原则是合同法律体系中非常重要的一部分,它规范了各方在合同履行中应当承担的责任和义务,保障了合同的有效履行。

- 1 -。

英文法律知识点

英文法律知识点随着全球化趋势的加速,英语已经成为国际交流中最为普及和重要的语言之一。

不管是商务往来、国际合作还是留学移民,对英文法律知识的了解都显得至关重要。

在这篇文章中,我们将探讨一些常见的英文法律知识点,帮助读者更好地掌握和理解这一重要领域。

1. 合同法(Contract Law)合同法是英文法律体系中的关键部分,它规定了人们在购买商品、签订合作协议以及其他经济交易中的权利和义务。

在英文合同中,常见的术语包括offer(提议)、acceptance(接受)、consideration(对价)和breach(违约)等。

了解这些术语和相关法律规定,对于商务谈判和合同起草至关重要。

2. 知识产权法(Intellectual Property Law)知识产权法保护创作者和发明家的权益,包括专利、商标、版权和商业秘密等。

英文法律术语中,patent(专利)、trademark(商标)、copyright(版权)和infringement(侵权)等是我们需要熟悉的关键词汇。

尤其是在国际知识产权保护中,了解相关的法律制度和规定,对于维护自身权益至关重要。

3. 劳动法(Labor Law)劳动法涉及雇佣关系和劳动者权益保护。

英文法律术语中,常见的有employment contract(雇佣合同)、minimum wage(最低工资)、dismissal(解雇)和discrimination(歧视)等。

在员工与雇主之间发生纠纷时,对劳动法的了解能够帮助我们明确权益,并且寻求公正的解决方式。

4. 不动产法(Real Estate Law)不动产法涉及土地和建筑物的买卖、租赁和产权等问题。

在英文法律术语中,我们需要熟悉的词汇有property(财产)、title(产权)、mortgage(抵押)和tenancy agreement(租赁合同)等。

了解不动产法知识有助于我们在购买房产、租赁房屋或处理产权纠纷时,保护自身合法权益。

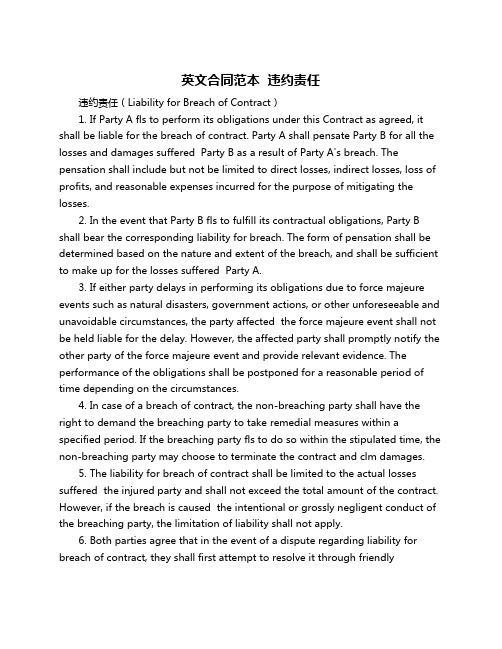

英文合同范本 违约责任

英文合同范本违约责任违约责任(Liability for Breach of Contract)1. If Party A fls to perform its obligations under this Contract as agreed, it shall be liable for the breach of contract. Party A shall pensate Party B for all the losses and damages suffered Party B as a result of Party A's breach. The pensation shall include but not be limited to direct losses, indirect losses, loss of profits, and reasonable expenses incurred for the purpose of mitigating the losses.2. In the event that Party B fls to fulfill its contractual obligations, Party B shall bear the corresponding liability for breach. The form of pensation shall be determined based on the nature and extent of the breach, and shall be sufficient to make up for the losses suffered Party A.3. If either party delays in performing its obligations due to force majeure events such as natural disasters, government actions, or other unforeseeable and unavoidable circumstances, the party affected the force majeure event shall not be held liable for the delay. However, the affected party shall promptly notify the other party of the force majeure event and provide relevant evidence. The performance of the obligations shall be postponed for a reasonable period of time depending on the circumstances.4. In case of a breach of contract, the non-breaching party shall have the right to demand the breaching party to take remedial measures within a specified period. If the breaching party fls to do so within the stipulated time, the non-breaching party may choose to terminate the contract and clm damages.5. The liability for breach of contract shall be limited to the actual losses suffered the injured party and shall not exceed the total amount of the contract. However, if the breach is caused the intentional or grossly negligent conduct of the breaching party, the limitation of liability shall not apply.6. Both parties agree that in the event of a dispute regarding liability for breach of contract, they shall first attempt to resolve it through friendlynegotiation. If the negotiation fls, either party may resort to legal means to protect its legitimate rights and interests.Please note that the above is a general template and may need to be tlored to the specific circumstances and requirements of your contract. It is remended to seek legal advice when drafting and finalizing a contract to ensure its legality and enforceability.。

论合同法违约责任论文

论合同法违约责任论文论合同法违约责任论文合同法违约责任论文违约责任是我国《合同法》中的一项最重要的制度,《合同法》对以往的违约责任制度进行若干补充和完善,其最大的特点在于:第一,增加预期违约责任和加害给付责任,从而构筑了违约责任的真正内涵。

第二,以严格责任作为违约责任的一般归责原则,从而强化了违约责任的功能,顺应了合同法的发展趋势。

第三,将预期违约制度和不安抗辩兼容并蓄,从而弥补了预期违约和不安抗辩权适用上的缺陷。

第四,将完全赔偿原则和可预见规则相结合,从而兼顾合同双方当事人的利益平衡。

第五,允许违约责任与侵权责任竞合,最大限度地保护了当事人的合法权益,并给当事人行使权利提供充分的空间。

[1]本文拟结合我国现行《合同法》对违约责任制度的相关问题作粗略的论析。

一、违约责任的性质违约责任即违反了合同的民事责任,是指合同当事人一方不履行合同义务或者履行合同义务不符合约定时,依照法律规定或者合同的约定所应承担的法律责任。

1999年3月15日颁布的《中华人民共和国合同法》(以下简称《合同法》)对违约责任的内容进行了一定的修改和补充,其中的违约责任制度吸收了以往三部合同法行之有效的规定和借鉴了国外的有益经验,体现了我国违约责任制度的稳定性、连续性和发展性。

在英美法系中违约责任通常被称为违约的补救,而在大陆法系中,则被包括在债务不履行责任之中,或被视为债的效力的范畴。

违约责任制度是保障债权实现及债务履行的重要措施,它与合同义务有密切联系,合同义务是违约责任产生的前提,违约责任则是合同义务不履行的结果。

在我国违约责任具有以下特点:第一,违约责任是合同当事人违反合同义务所产生的责任。

这里包含两层意思:其一,违约责任产生的基础是双方当事人之间存在合法有效的合同关系,若当事人之间不存在有效的合同关系,则无违约责任可言;其二,违约责任是以违反合同义务为前提,没有违反合同义务的行为,便没有违约责任。

第二,违约责任具有相对性。

英文合同范本 违约责任

英文合同范本违约责任违约责任(Liability for Breach of Contract)1. If either Party fls to perform any of its obligations under this Contract, such Party shall be liable for the breach of contract and shall pensate the other Party for all losses and damages suffered there.(如果任何一方未能履行本合同项下的任何义务,该方应承担违约责任,并应赔偿另一方因此遭受的所有损失和损害。

)2. In the event of a breach the Buyer of its payment obligations, the Buyer shall pay interest on the overdue amount at a rate of [X]% per annum from the due date until the date of actual payment.(如果买方违反其付款义务,买方应就逾期金额按年利率[X]%支付利息,从到期日起至实际付款日止。

)3. If the Seller fls to deliver the goods in accordance with the terms of this Contract, the Seller shall be obligated to rectify the situation within a reasonable time. If the Seller fls to do so, the Buyer shall have the right to clm damages equivalent to the loss suffered.(如果卖方未能按照本合同的条款交付货物,卖方有义务在合理时间内纠正该情况。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

The breach of contract in French law: between safety ofexpectations and efficiencyPierre Garello∗1.Introduction: which path will lead us to a better understanding of French contract law?Contracts are marvellous tools to help us to live in a world of uncertainty. They allow us to project ourselves into an unknowable future, to invest. Lawyers who have inspired the French Civil law and contributed to its evolution, as well as most lawyers in the world, have clearly perceived the necessity to protect t hat institution. “The contract is, as far as the individual is concerned, the best forecasting instrument generating legal security, and the favored path to freedom and responsibility that is necessary for the flourishing of human beings in a society.Contracts are far from miraculous tools, however. If they make life easier, they do not necessarily make life easy. As the future unfolds, one or both contracting parties may be tempted, or compelled, to break his or her promise. But, the mere fact that the contract is running into difficulties does not force the law to do something!2 It is only when one of the parties does not perform that the law (the court, the legislation), backed with coercive power, has to give an opinion, to decide the case. In order to do so some principles, or theories, are required to reach a judgment as to what is the best thing to do.The present study of the French contract law is based on the premise that, from a law and economics point of view, there exists basically two possible ways to address this concern: the first approach requires that whenever a problem arises, an assessment be made of all costs and benefits incurred by the parties. In other words, one must attempt to evaluate in a sufficiently precise way the consequences of the court decision—or of the rule of law under consideration—for both parties as well as for third parties (including potential future contractors). The lawthen—and more precisely here, contract law—should aim primarily at providing the right incentiv es to contracting parties, where by “right incentives” one meansincentives to behave in such a way that the difference between social benefits and social costs be maximized. It will be argued below that French contract law sometimes follows this approach.The second possible attitude looks, apparently, pretty much like the first. The guiding principle is again that the law should provide to members of the society the right incentives. But one must immediately add that the judge—or the legislator, or the expert—is not in a position to evaluate and compare the social costs and benefits of alternative rules of law. He or she just does not know enough. One does not know, for instance, all the effects of a rule that would allow one party to breach a contract, without the consent of the other party. Indeed, even if the victim of the breach is promised a fair compensation, allowing such a rule globally might have a negative effect on the very purpose of the institution, which is to reduce uncertainty. As a consequence, the law should adopt a goal less ambitious than the maximization of social well being. That goal could be “to protect contracts,” or, in other terms, to create a set of incentives that lead individuals to feel confident that their legitimate expectations will be fulfilled.As pointed out, those two attitudes may appear the same, differing just in degree. The first one assumes more knowledge on the part of lawyers and legislators than the second. However, when it comes to practical decision-making, differences turn out to be important, because the more knowledgeable you think you are, the stronger will be the incentive to regulate the contract, and the lower will be the respect for tradition and customs on which daily expectations are based.The two approaches outlined above are well known to economists. The first one is the so-called “mainstream” (Paretian) approach and underlines most of the existing economic analysis of law.3 The second one, stressing the problem of knowledge, is far less developed.4 We will call it the “safety-of-expectations approach,” or the Austrian approach to law and economics, because it can be found primarily in thework of the Austrian school of economic thought, and especially in Hayek’s studies.“The rationale,” says Hayek, “of securing to each individual a known range within which he can decide on his actions is to enable him to make the fullest use of his knowledge, especially of his concrete and often unique knowledge of the particular circumstances of time and place. The law tells him what facts he may count on and thereby extends the range within which he can predict the consequences of his actions. At the same time it tells him what possible consequences of his actions he must take into account or what he will be held responsible for.The reason why these two approaches are mentioned at the outset is that, when one studies French contract law, it is difficult to reconcile all of it with a single approach. True, the mainstream, neoclassical approach, based on the assumption that rules be chosen that maximize social wealth (or, at other times, that lead to a Pareto-efficient outcome), can help us to understand an important part of that body of law. But, as will be shown, certain French doctrines cannot be reconciled with neither a Paretian approach, nor a wealth maximizing approach. In some instances, the lawseems to be more concerned with the safety of expectations.In the next two sections we will examine the main doctrines and rules of French contract law trying to identify those that are compatible with both principles and those that are compatible with only one. If none of those sets are empty, it will mean that the French law of contract is not totally coherent; it cannot be brought under a unique unifying principle of explanation. The next natural questionwould then be whether French lawismoving towards one principle and away from the other. However, this paper will not address this question.The paper is organized in two parts. Indeed, for reasons briefly mentioned above, it is important to underline in a first part the many things the law does in order to avoid breach of contract: what can be done in order to save a contract when the parties are having difficulties performing, and what is forbidden? The second part deals directly with the breach of contract. It will be shown that French law differs in some important respects from other contract laws. 2.Saving the contract63.We will study the various attempts to “save” the contract by looking first at the conditions for invalidity (Section 2.1), then at the various possibilities left to the judge to interpret the terms of the contract (Section 2.2) and end with the study of the cases where the judge is authorized to change the terms of the contract (Section 2.3).2.1. Invalid contractsOne way to save the contract is to prove that there was no valid contract in the first place! Formation defenses as defined in the French law are roughly identical to those found in the contract laws of other countries. The main defenses are: incompetency (incapacité), mistakes (erreur), fraud (dol), duress (violence), absence of cause (reminding us of the doctrine of consideration in the bargaining theory), failure to disclose information, lésion (a defense close to unconscionability),7 or, may be more specific to French law, a conflict between the private agreement and ordre public, i.e. public policy, or “law and order” (see art. 6 and 1134 of the French Civil Code, henceforth C.civ.). In all these instances, an action may be taken for annulment of the contract, the judge being the only one entitled to invalidate a contract.But, what exactly is meant by invalidity in the French law? What are the consequences? The French law distinguishes between absolute invalidity (nullitéabsolue) and relative invalidity (nullité relative). The first category includes all the contracts that are against what is called ordre public de direction, that is to say, contracts that violate a public policy judged to be beneficial to the society as a whole and not only to those individuals involved in that particular contract. For such contracts nothing can be done and complete nullity cannot be avoided. The second category is made of contracts that violate the ordre public de protection, that is, contracts in which one party does not respect a public policy designed to protect weaker parties. In those circumstances, the victim who the law is trying to protect may choose to let the contract stand after modifications to the contract.In both cases, however, the result is as if the contract had never existed, and retroactivity with restitution is the general principle: one is supposed to go back to the situation that prevailed before the contract was created: the status quo ante. Parties are relieved of their obligations, and damages can no longer be awarded, but it is still possible to bring a tort law action.From an economic point of view, most of the formation defenses mentioned have already been analyzed in various places, the bottom line being: any contract that is not voluntary must be considered as invalid. One can see however that, from a strictly Paretian point of view, it is not clear that all involuntary contracts—e.g. contracts relying on a mistake—will always be dominated by the situation prevailing before the contract. If one chooses the Hayekian, safety-of-expectations point of view, such a dilemma is less likely to occur to the extent that people expect transactions to be voluntary. Consequently, any involuntary transaction violates some “legitimate exp ectations.Before leaving the topic of nullity, two interesting facts deserve attention. First, it must be pointed out that exceptions exist to the general principle of retroactivity with restitution. In particular, if the contract is null due to the deliberate action of one of the parties (e.g. In the case of fraud), the principle is softened; the victim sometimes will not have to return the object, or the payment. The action for annulment can even be rejected by the judge if this favors the victim. Finally, because few cases of fraud are brought to court, the legislator has stepped in to regulate the contractual process. This is the case, for instance, with the law of August 1, 1905 on fraud (now part of consumer law, Code de la Consommation, article L. 213–1), or the law of December 27, 1973 on advertising (today C. Consommation a. L.124–1).10 Legislation sometimes seeks to protect potential victims of fraudulent behaviour. This type of intervention can be easily justified in the Paretian or wealth-maximization frameworks because it reduces some transaction costs. It is better that the law sends clear signals to potential wrongdoers thanto correct wrongdoings once they have occurred. From an Hayekian perspective, the benefits of such intervention are less evident because you have to take into account the fact that the potential victims may, as a result, be less careful, and behave in a less responsible way. In any case, one should keep in mind that courts consider invalidity to be something exceptional. “T o restrict as much as possible the number of nullity cases seems to fit with the contemporary need to bring more security to business.”11.2.2. Interpreting the contractTo save the contract, the judge may have to interpret its terms or to modify them. When reading legal scholars on the topics, one comes rapidly to the conclusion that there is no unanimity in France about what is the proper role for the judge when performance is problematic. As explains Ghestin: “Hence, always referring to justice, it is po ssible to forbid to the judge any intervention, or at the opposite, and as is done today, to justify his/her corrective interference, so that he/she can guarantee that there is at least a relative balance between the promises that are being exchanged.”12 This analysis can also be found in Delebecque, Pansier: The role of the judge in appreciating the terms of the contract is a matter of great controversy.On one hand, you may wish to deprive the judge of any power arguing that he is not a party to the contract; consequently, the judge should never intervene, nor modify such and such elements of the contract. On the other hand, one can admit the intervention of the judge in contractual matters in order to introduce a light wind of fairness in the contract. The law is rather based on the first approach.Indeed, as we have noticed already, the legislator allows himself or herself the right to perfect and regulate some contracts, and the judge, stimulated and reassured by such intervention, has decided that he also as a right to step in.13 Keeping in mind this controversy, let us see what the French written law says.A major principle of French law is juridical consensualism (consensualisme juridique). Deeply rooted in French tradition—it goes back to the 18th century and became prominent in the 15th century14—this principle is closely related to a more recent one: the autonomy of the will.15 In contractual matters this means that the contract should be interpreted, not literally, but according to good faith. This is also called the subjective method of interpretation and is grounded in art. 1156 to 1164 C.civ.: “As far as conventions are concerned, one must look for the common intention of the contracting parties rather than look for the literal meaning of the terms” (art. 1156 C.civ.). Now, if to interpret is to try to rediscover what the parties really wanted, does this method make sense from an economic point of view, or should it be changed for the objective method?On the bright side, whether you are Paretian or Austrian, you can argue that this method of interpretation reduces transaction costs since the parties may leave the contract incomplete: if necessary, the judge—or more generally, the law through default rules—will interpret thecontract as they would have written it, if it was not for the cost of writing done a complete contract. Not only that, but the very possibility to leave gaps in the contract may be desirable to allow the parties to signal a high degree of confidence that promises will be performed; in other words, gaps may be useful strategic tools.On the dark side, it may be pointed out that the objective method, chosen in other countries such as Germany, forces the parties to be more explicit on what they expect and this, in turn, may reduce future transaction costs. Also it should be recalled that it is not always easy to interpret the will of the parties, and it is good for that reason to give them strong incentives to fill up as many gaps as possible.Anyway, the French law will not let the judge interpret the terms of the contract, or fill gaps as it pleases her. The judge will have to follow certain rules. Here are some of them.16 First maxim: better to interpret the contract in such a way that it will survive (art. 1157 C.civ.). Again one can read here an a priori in favour of voluntary exchanges which, as was pointed out earlier, is economically sound. It is also the desire to avoid that efforts invested in the contractual relationship be wasted.Second maxim (only for unilateral contracts such as loan contracts): the judge should interpret the contract in the way which is most favorable to the debtor (art. 1162 C.civ.). One can perceive two economic reasons to this rule. Firstly, it increases the probability of performance since it is the debtor who is having difficulties. Secondly, the maxim let the creditor bears the risks related to a lack of precision in the terms of the contract. This in average is a good thing since the creditor is often the one who has the greatest influence on the choice of the terms of the contracts and is therefore in a position to avoid risk at least cost. The same logic can be found when the French law stipulates that, in contracts of adhesion, whoever has written the contract should bear the risks associated with ambiguity in the terms of the contract, and consequently, the contract should be interpreted against him or her. It is always desirable from an efficiency point of view, as well as from a safety of expectations point of view, to unify knowledge and decision-making.The third maxim of interpretation is derived from art. 1136 of C.civ.: “Conventions compel the parties to perform not only according to what is written, but also according to the requirements of fairness, customs and existing legislation.” This s omehow echoes the famous article 6 of C.civ. It is based on this philosophy that the courts have recently established some new bonds for the parties. Hence, each party ought to inform properly the other parties, especially as far as safety is concerned: a surgeon must inform the client of the likely consequences of the operation, the producer must inform the client of the composition of the product, the transporter must safely perform his/her job. In each case, if the obligation is not fulfilled, the party who has failed to disclose information will be held liable.17 Now, what is the economist’s point of view on those matters? For a Paretian, one could argue that this maximallows a reduction of transaction costs. But it can also be seen as a desire to protect legitimate expectations. Everyone, including third parties, expect others to behave according to custom, state-of-the-art, and the law. Therefore, such expectations should not be disappointed. One can add, however, a proviso to that opinion: if one accepts that the parties might in some cases be surprised by the interpretation given by a judge based on customs, state-of-the-art and legislation,18 it should nonetheless be added that, as soon as the law becomes too complex, to follow this line of thought would not be reasonable and wouldwork basically against the safety of expectations. As Carbonnier puts it with humour: “laws and contracts are valid to the extent that they take into account the capacity of our brains.”19Finally let us recall that in French law, if the judge goes beyond the mere interpretation of the contract, the judgment will be broken by the Cour de Cassation. This, surely, is compatible with the safety of expectations.2.3. Modification of the contract by the judge“To interpret the contract is to pay due homage to the autonomy of the will. To modify a contract is to testify against it.”20The life of a contract being full of unexpected events, there is nothing more economically sound as far as Paretian efficiency is concerned as well as for the safety of expectations, to let the parties renegotiate to the extent, of course, that both parties agree to the change. French contract law understands this and facilitates such commonly agreed upon changes. It can even go further: if the contract includes a revision clause, the courts have the possibility to impose a revision if the negotiation fails. Also, if one of the parties refuses to negotiate, it can be condemned to pay damages for an amount corresponding to the loss incurred by the other party because of that refusal.21 In the same spirit, in order to facilitate the revision of the contract, clauses establishing an automatic revision of the contract are lawful. Such clauses, that reduce further transaction costs, are nonetheless controlled by the judge. In particular, the event triggering off the revision should be beyond the control of the parties, this in order to avoid any moral hazard problem.Difficulties arise of course whenever one of the parties refuses to negotiate. In such circumstances French contract law takes a path different from the one taken by most other contract laws, and forbid any modification of the contract by the judge. Exceptions exist to this reject of the so-called théorie de l’imprévision, but they are few. Hence, it is possible to rescind a contract (this is called rescision pour lésion) following the realization of an unforeseeable event (art. 1675 C.civ.), but one should recall that “l’aléa exclut la lésion,” which means that if the contract is contingent by nature (for instance an insurance contract), then there cannot be any lesion and therefore there exists no way to modify such contract following an unforeseen event.This position against a modification of the contract by the judge has a long standing inFrench law, going back to the famous 1876 decision of the supreme court of appeal in the Canal de Craponne case. In that case, the heirs of Mr. Adam de Craponne wanted the price for maintenance of a canal to be raised, a price that was contractually fixed in 1567 by Adam de Craponne. Relying on art. 1134 C.civ., the court replied that: “It is not the business of the courts to take into account time and circumstances in order to modify the conventions decided previously upon by the parties, even if such a modi fication appears fair.”Two last remarks before leaving that topic. First, let us note that if the position of the French courts has been accepted by the business community, it is because parties always keep the possibility to add some clauses to the contract regarding unforeseen events and, actually, they have made extensive use of it.26 Finally, if the position of the Civil law is against judiciary revision, administrative law has taken an other path, allowing for the revision of the contract,27 and the legislator also organizes the revision in some cases (e.g. leases and intellectual property rights).法国法律中的违约责任:在安全的期望值和有效性之间Pierre Garello1论文简介:哪个途径可以让我们更好地了解法国合同法?合同是帮助我们在不确定的世界上生活的很好的工具,它们可以使我们计划自己不知道的未来和投资。