A White Heron

浙江省温州市2019-2020学年龙湾区九年级下学期英语二模试卷(有答案)

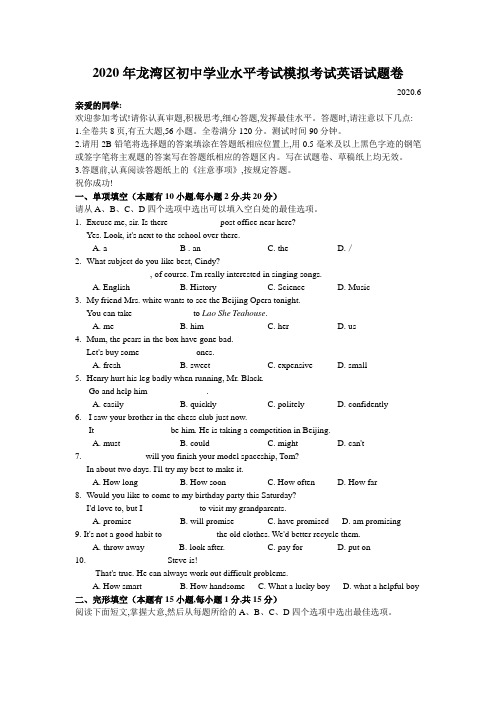

2020年龙湾区初中学业水平考试模拟考试英语试题卷2020.6 亲爱的同学:欢迎参加考试!请你认真审题,积极思考,细心答题,发挥最佳水平。

答题时,请注意以下几点:1.全卷共8页,有五大题,56小题。

全卷满分120分。

测试时间90分钟。

2.请用2B铅笔将选择题的答案填涂在答题纸相应位置上,用0.5毫米及以上黑色字迹的钢笔或签字笔将主观题的答案写在答题纸相应的答题区内。

写在试题卷、草稿纸上均无效。

3.答题前,认真阅读答题纸上的《注意事项》,按规定答题。

祝你成功!一、单项填空(本题有10小题,每小题2分,共20分)请从A、B、C、D四个选项中选出可以填入空白处的最佳选项。

1. -Excuse me, sir. Is there ___________ post office near here?-Yes. Look, it's next to the school over there.A. a B . an C. the D./2. -What subject do you like best, Cindy?- ______________, of course. I'm really interested in singing songs.A. EnglishB. HistoryC. ScienceD. Music3. -My friend Mrs. white wants to see the Beijing Opera tonight.-You can take _____________ to Lao She Teahouse.A. meB. himC. herD. us4. -Mum, the pears in the box have gone bad.-Let's buy some ____________ ones.A. freshB. sweetC. expensiveD. small5. -Henry hurt his leg badly when running, Mr. Black.- Go and help him _____________.A. easilyB. quicklyC. politelyD. confidently6. - I saw your brother in the chess club just now.- It_________________ be him. He is taking a competition in Beijing.A. mustB. couldC. mightD. can't7. -_____________ will you finish your model spaceship, Tom?-In about two days. I'll try my best to make it.A. How longB. How soonC. How oftenD. How far8. -Would you like to come to my birthday party this Saturday?-I'd love to, but I ____________ to visit my grandparents.A. promiseB. will promiseC. have promisedD. am promising9. It's not a good habit to____________ the old clothes. We'd better recycle them.A. throw awayB. look after.C. pay forD. put on10. -_________________ Steve is!-That's true. He can always work out difficult problems.A. How smartB. How handsomeC. What a lucky boyD. what a helpful boy二、完形填空(本题有15小题,每小题1分,共15分)阅读下面短文,掌握大意,然后从每题所给的A、B、C、D四个选项中选出最佳选项。

A white heron(英文原版)

A WHITE HERONSarah Orne JewettI.The woods were already filled with shadows one June evening, just before eight o'clock, though a bright sunset still glimmered faintly among the trunks of the trees. A little girl was driving home her cow, a plodding, dilatory, provoking creature in her behavior, but a valued companion for all that. They were going away from whatever light there was, and striking deep into the woods, but their feet were familiar with the path, and it was no matter whether their eyes could see it or not.There was hardly a night the summer through when the old cow could be found waiting at the pasture bars; on the contrary, it was her greatest pleasure to hide herself away among the huckleberry bushes, and though she wore a loud bell she had made the discovery that if one stood perfectly still it would not ring. So Sylvia had to hunt for her until she found her, and call Co' ! Co' ! with never an answering Moo, until her childish patience was quite spent. If the creature had not given good milk and plenty of it, the case would have seemed very different to her owners. Besides, Sylvia had all the time there was, and very little use to make of it. Sometimes in pleasant weather it was a consolation to look upon the cow's pranks as an intelligent attempt to play hide and seek, and as the child had no playmates she lent herself to this amusement with a good deal of zest. Though this chase had been so long that the wary animal herself had given an unusual signal of her whereabouts, Sylvia had only laughed when she came upon Mistress Moolly at the swamp-side, and urged her affectionately homeward with a twig of birch leaves. The old cow was not inclined to wander farther, she even turned in the right direction for once as they left the pasture, and stepped along the road at a good pace. She was quite ready to be milked now, and seldom stopped to browse. Sylvia wondered what her grandmother would say because they were so late. It was a great while since she had left home at half-past five o'clock, but everybody knew the difficulty of making this errand a short one. Mrs. Tilley had chased the hornéd torment too many summer evenings herself to blame any one else for lingering, and was only thankful as she waited that she had Sylvia, nowadays, to give such valuable assistance. The good woman suspected that Sylvia loitered occasionally on her own account; there never was such a child for straying about out-of-doors since the world was made! Everybody said that it was a good change for a little maid who had tried to grow for eight years in a crowded manufacturing town, but, as for Sylvia herself, it seemed as if she never had been alive at all before she came to live at the farm. She thought often with wistful compassion of a wretched geranium that belonged to a town neighbor."'Afraid of folks,'" old Mrs. Tilley said to herself, with a smile, after she had made the unlikely choice of Sylvia from her daughter's houseful of children, and was returning to the farm. "'Afraid of folks,' they said! I guess she won't be troubled no great with 'em up to the old place!" When they reached the door of the lonely house and stopped to unlock it, and the cat came to purr loudly, and rub against them, a deserted pussy, indeed, but fat with young robins, Sylvia whispered that this was a beautiful place to live in, and she never should wish to go home.The companions followed the shady wood-road, the cow taking slow steps and the child very fast ones. The cow stopped long at the brook to drink, as if the pasture were not half a swamp, and Sylvia stood still and waited, letting her bare feet cool themselves in the shoal water, whilethe great twilight moths struck softly against her. She waded on through the brook as the cow moved away, and listened to the thrushes with a heart that beat fast with pleasure. There was a stirring in the great boughs overhead. They were full of little birds and beasts that seemed to be wide awake, and going about their world, or else saying good-night to each other in sleepy twitters. Sylvia herself felt sleepy as she walked along. However, it was not much farther to the house, and the air was soft and sweet. She was not often in the woods so late as this, and it made her feel as if she were a part of the gray shadows and the moving leaves. She was just thinking how long it seemed since she first came to the farm a year ago, and wondering if everything went on in the noisy town just the same as when she was there, the thought of the great red-faced boy who used to chase and frighten her made her hurry along the path to escape from the shadow of the trees.Suddenly this little woods-girl is horror-stricken to hear a clear whistle not very far away. Not a bird's-whistle, which would have a sort of friendliness, but a boy's whistle, determined, and somewhat aggressive. Sylvia left the cow to whatever sad fate might await her, and stepped discreetly aside into the bushes, but she was just too late. The enemy had discovered her, and called out in a very cheerful and persuasive tone, "Halloa, little girl, how far is it to the road?" and trembling Sylvia answered almost inaudibly, "A good ways."She did not dare to look boldly at the tall young man, who carried a gun over his shoulder, but she came out of her bush and again followed the cow, while he walked alongside."I have been hunting for some birds," the stranger said kindly, "and I have lost my way, and need a friend very much. Don't be afraid," he added gallantly. "Speak up and tell me what your name is, and whether you think I can spend the night at your house, and go out gunning early in the morning."Sylvia was more alarmed than before. Would not her grandmother consider her much to blame? But who could have foreseen such an accident as this? It did not seem to be her fault, and she hung her head as if the stem of it were broken, but managed to answer "Sylvy," with much effort when her companion again asked her name.Mrs. Tilley was standing in the doorway when the trio came into view. The cow gave a loud moo by way of explanation."Yes, you'd better speak up for yourself, you old trial! Where'd she tucked herself away this time, Sylvy?" But Sylvia kept an awed silence; she knew by instinct that her grandmother did not comprehend the gravity of the situation. She must be mistaking the stranger for one of the farmer-lads of the region.The young man stood his gun beside the door, and dropped a lumpy game-bag beside it; then he bade Mrs. Tilley good-evening, and repeated his wayfarer's story, and asked if he could have a night's lodging."Put me anywhere you like," he said. "I must be off early in the morning, before day; but I am very hungry, indeed. You can give me some milk at any rate, that's plain.""Dear sakes, yes," responded the hostess, whose long slumbering hospitality seemed to be easily awakened. "You might fare better if you went out to the main road a mile or so, but you're welcome to what we've got. I'll milk right off, and you make yourself at home. You can sleep on husks or feathers," she proffered graciously. "I raised them all myself. There's good pasturing for geese just below here towards the ma'sh. Now step round and set a plate for the gentleman, Sylvy!" And Sylvia promptly stepped. She was glad to have something to do, and she was hungry herself.It was a surprise to find so clean and comfortable a little dwelling in this New England wilderness. The young man had known the horrors of its most primitive housekeeping, and the dreary squalor of that level of society which does not rebel at the companionship of hens. This was the best thrift of an old-fashioned farmstead, though on such a small scale that it seemed like a hermitage. He listened eagerly to the old woman's quaint talk, he watched Sylvia's pale face and shining gray eyes with ever growing enthusiasm, and insisted that this was the best supper he had eaten for a month, and afterward the new-made friends sat down in the door-way together while the moon came up.Soon it would be berry-time, and Sylvia was a great help at picking. The cow was a good milker, though a plaguy thing to keep track of, the hostess gossiped frankly, adding presently that she had buried four children, so Sylvia's mother, and a son (who might be dead) in California were all the children she had left. "Dan, my boy, was a great hand to go gunning," she explained sadly. "I never wanted for pa'tridges or gray squer'ls while he was to home. He's been a great wand'rer, I expect, and he's no hand to write letters. There, I don't blame him, I'd ha' seen the world myself if it had been so I could."Sylvy takes after him," the grandmother continued affectionately, after a minute's pause. "There ain't a foot o' ground she don't know her way over, and the wild creaturs counts her one o' themselves. Squer'ls she'll tame to come an' feed right out o' her hands, and all sorts o' birds. Last winter she got the jay-birds to bangeing here, and I believe she'd 'a' scanted herself of her own meals to have plenty to throw out amongst 'em, if I hadn't kep' watch. Anything but crows, I tell her, I'm willin' to help support -- though Dan he had a tamed one o' them that did seem to have reason same as folks. It was round here a good spell after he went away. Dan an' his father they didn't hitch, -- but he never held up his head ag'in after Dan had dared him an' gone off."The guest did not notice this hint of family sorrows in his eager interest in something else."So Sylvy knows all about birds, does she?" he exclaimed, as he looked round at the little girl who sat, very demure but increasingly sleepy, in the moonlight. "I am making a collection of birds myself. I have been at it ever since I was a boy." (Mrs. Tilley smiled.) "There are two or three very rare ones I have been hunting for these five years. I mean to get them on my own ground if they can be found.""Do you cage 'em up?" asked Mrs. Tilley doubtfully, in response to this enthusiastic announcement."Oh no, they're stuffed and preserved, dozens and dozens of them," said the ornithologist, "and I have shot or snared every one myself. I caught a glimpse of a white heron a few miles from here on Saturday, and I have followed it in this direction. They have never been found in this district at all. The little white heron, it is," and he turned again to look at Sylvia with the hope of discovering that the rare bird was one of her acquaintances.But Sylvia was watching a hop-toad in the narrow footpath."You would know the heron if you saw it," the stranger continued eagerly. "A queer tall white bird with soft feathers and long thin legs. And it would have a nest perhaps in the top of a high tree, made of sticks, something like a hawk's nest."Sylvia's heart gave a wild beat; she knew that strange white bird, and had once stolen softly near where it stood in some bright green swamp grass, away over at the other side of the woods. There was an open place where the sunshine always seemed strangely yellow and hot, where tall, nodding rushes grew, and her grandmother had warned her that she might sink in the soft blackmud underneath and never be heard of more. Not far beyond were the salt marshes just this side the sea itself, which Sylvia wondered and dreamed much about, but never had seen, whose great voice could sometimes be heard above the noise of the woods on stormy nights."I can't think of anything I should like so much as to find that heron's nest," the handsome stranger was saying. "I would give ten dollars to anybody who could show it to me," he added desperately, "and I mean to spend my whole vacation hunting for it if need be. Perhaps it was only migrating, or had been chased out of its own region by some bird of prey."Mrs. Tilley gave amazed attention to all this, but Sylvia still watched the toad, not divining, as she might have done at some calmer time, that the creature wished to get to its hole under the door-step, and was much hindered by the unusual spectators at that hour of the evening. No amount of thought, that night, could decide how many wished-for treasures the ten dollars, so lightly spoken of, would buy.The next day the young sportsman hovered about the woods, and Sylvia kept him company, having lost her first fear of the friendly lad, who proved to be most kind and sympathetic. He told her many things about the birds and what they knew and where they lived and what they did with themselves. And he gave her a jack-knife, which she thought as great a treasure as if she were a desert-islander. All day long he did not once make her troubled or afraid except when he brought down some unsuspecting singing creature from its bough. Sylvia would have liked him vastly better without his gun; she could not understand why he killed the very birds he seemed to like so much. But as the day waned, Sylvia still watched the young man with loving admiration. She had never seen anybody so charming and delightful; the woman's heart, asleep in the child, was vaguely thrilled by a dream of love. Some premonition of that great power stirred and swayed these young creatures who traversed the solemn woodlands with soft-footed silent care. They stopped to listen to a bird's song; they pressed forward again eagerly, parting the branches -- speaking to each other rarely and in whispers; the young man going first and Sylvia following, fascinated, a few steps behind, with her gray eyes dark with excitement.She grieved because the longed-for white heron was elusive, but she did not lead the guest, she only followed, and there was no such thing as speaking first. The sound of her own unquestioned voice would have terrified her -- it was hard enough to answer yes or no when there was need of that. At last evening began to fall, and they drove the cow home together, and Sylvia smiled with pleasure when they came to the place where she heard the whistle and was afraid only the night before.II.Half a mile from home, at the farther edge of the woods, where the land was highest, a great pine-tree stood, the last of its generation. Whether it was left for a boundary mark, or for what reason, no one could say; the woodchoppers who had felled its mates were dead and gone long ago, and a whole forest of sturdy trees, pines and oaks and maples, had grown again. But the stately head of this old pine towered above them all and made a landmark for sea and shore miles and miles away. Sylvia knew it well. She had always believed that whoever climbed to the top of it could see the ocean; and the little girl had often laid her hand on the great rough trunk and looked up wistfully at those dark boughs that the wind always stirred, no matter how hot and still the air might be below. Now she thought of the tree with a new excitement, for why, if one climbed it at break of day, could not one see all the world, and easily discover from whence the white heronflew, and mark the place, and find the hidden nest?What a spirit of adventure, what wild ambition! What fancied triumph and delight and glory for the later morning when she could make known the secret! It was almost too real and too great for the childish heart to bear.All night the door of the little house stood open and the whippoorwills came and sang upon the very step. The young sportsman and his old hostess were sound asleep, but Sylvia's great design kept her broad awake and watching. She forgot to think of sleep. The short summer night seemed as long as the winter darkness, and at last when the whippoorwills ceased, and she was afraid the morning would after all come too soon, she stole out of the house and followed the pasture path through the woods, hastening toward the open ground beyond, listening with a sense of comfort and companionship to the drowsy twitter of a half-awakened bird, whose perch she had jarred in passing. Alas, if the great wave of human interest which flooded for the first time this dull little life should sweep away the satisfactions of an existence heart to heart with nature and the dumb life of the forest!There was the huge tree asleep yet in the paling moonlight, and small and silly Sylvia began with utmost bravery to mount to the top of it, with tingling, eager blood coursing the channels of her whole frame, with her bare feet and fingers, that pinched and held like bird's claws to the monstrous ladder reaching up, up, almost to the sky itself. First she must mount the white oak tree that grew alongside, where she was almost lost among the dark branches and the green leaves heavy and wet with dew; a bird fluttered off its nest, and a red squirrel ran to and fro and scolded pettishly at the harmless housebreaker. Sylvia felt her way easily. She had often climbed there, and knew that higher still one of the oak's upper branches chafed against the pine trunk, just where its lower boughs were set close together. There, when she made the dangerous pass from one tree to the other, the great enterprise would really begin.She crept out along the swaying oak limb at last, and took the daring step across into the old pine-tree. The way was harder than she thought; she must reach far and hold fast, the sharp dry twigs caught and held her and scratched her like angry talons, the pitch made her thin little fingers clumsy and stiff as she went round and round the tree's great stem, higher and higher upward. The sparrows and robins in the woods below were beginning to wake and twitter to the dawn, yet it seemed much lighter there aloft in the pine-tree, and the child knew she must hurry if her project were to be of any use.The tree seemed to lengthen itself out as she went up, and to reach farther and farther upward. It was like a great main-mast to the voyaging earth; it must truly have been amazed that morning through all its ponderous frame as it felt this determined spark of human spirit wending its way from higher branch to branch. Who knows how steadily the least twigs held themselves to advantage this light, weak creature on her way! The old pine must have loved his new dependent. More than all the hawks, and bats, and moths, and even the sweet voiced thrushes, was the brave, beating heart of the solitary gray-eyed child. And the tree stood still and frowned away the winds that June morning while the dawn grew bright in the east.Sylvia's face was like a pale star, if one had seen it from the ground, when the last thorny bough was past, and she stood trembling and tired but wholly triumphant, high in the tree-top. Yes, there was the sea with the dawning sun making a golden dazzle over it, and toward that glorious east flew two hawks with slow-moving pinions. How low they looked in the air from that height when one had only seen them before far up, and dark against the blue sky. Their grayfeathers were as soft as moths; they seemed only a little way from the tree, and Sylvia felt as if she too could go flying away among the clouds. Westward, the woodlands and farms reached miles and miles into the distance; here and there were church steeples, and white villages, truly it was a vast and awesome worldThe birds sang louder and louder. At last the sun came up bewilderingly bright. Sylvia could see the white sails of ships out at sea, and the clouds that were purple and rose-colored and yellow at first began to fade away. Where was the white heron's nest in the sea of green branches, and was this wonderful sight and pageant of the world the only reward for having climbed to such a giddy height? Now look down again, Sylvia, where the green marsh is set among the shining birches and dark hemlocks; there where you saw the white heron once you will see him again; look, look!a white spot of him like a single floating feather comes up from the dead hemlock and grows larger, and rises, and comes close at last, and goes by the landmark pine with steady sweep of wing and outstretched slender neck and crested head. And wait! wait! do not move a foot or a finger, little girl, do not send an arrow of light and consciousness from your two eager eyes, for the heron has perched on a pine bough not far beyond yours, and cries back to his mate on the nest and plumes his feathers for the new day!The child gives a long sigh a minute later when a company of shouting cat-birds comes also to the tree, and vexed by their fluttering and lawlessness the solemn heron goes away. She knows his secret now, the wild, light, slender bird that floats and wavers, and goes back like an arrow presently to his home in the green world beneath. Then Sylvia, well satisfied, makes her perilous way down again, not daring to look far below the branch she stands on, ready to cry sometimes because her fingers ache and her lamed feet slip. Wondering over and over again what the stranger would say to her, and what he would think when she told him how to find his way straight to the heron's nest."Sylvy, Sylvy!" called the busy old grandmother again and again, but nobody answered, and the small husk bed was empty and Sylvia had disappeared.The guest waked from a dream, and remembering his day's pleasure hurried to dress himself that it might sooner begin. He was sure from the way the shy little girl looked once or twice yesterday that she had at least seen the white heron, and now she must really be made to tell. Here she comes now, paler than ever, and her worn old frock is torn and tattered, and smeared with pine pitch. The grandmother and the sportsman stand in the door together and question her, and the splendid moment has come to speak of the dead hemlock-tree by the green marsh.But Sylvia does not speak after all, though the old grandmother fretfully rebukes her, and the young man's kind, appealing eyes are looking straight in her own. He can make them rich with money; he has promised it, and they are poor now. He is so well worth making happy, and he waits to hear the story she can tell.No, she must keep silence! What is it that suddenly forbids her and makes her dumb? Has she been nine years growing and now, when the great world for the first time puts out a hand to her, must she thrust it aside for a bird's sake? The murmur of the pine's green branches is in her ears, she remembers how the white heron came flying through the golden air and how they watched the sea and the morning together, and Sylvia cannot speak; she cannot tell the heron's secret and give its life away.Dear loyalty, that suffered a sharp pang as the guest went away disappointed later in the day, that could have served and followed him and loved him as a dog loves! Many a night Sylviaheard the echo of his whistle haunting the pasture path as she came home with the loitering cow. She forgot even her sorrow at the sharp report of his gun and the sight of thrushes and sparrows dropping silent to the ground, their songs hushed and their pretty feathers stained and wet with blood. Were the birds better friends than their hunter might have been, -- who can tell? Whatever treasures were lost to her, woodlands and summer-time, remember! Bring your gifts and graces and tell your secrets to this lonely country child!。

中英文对照版-一只白色的苍鹭

那个年轻人把枪靠在门边,又把一只鼓鼓囊囊的狩猎袋扔在枪的旁边;接着他向梯尔利太太道了声晚上好,又重述了一遍他那徒步旅行者的故事.他还问能不能让他在这儿过一夜.

她不敢放胆抬起头来看这个高高的小伙子,这人肩膀上扛着一支枪。不过她还是从树丛里钻了出来,重新跟在母牛屁股后面.那年轻人走在她的身边。

“我是来打几种鸟的,”陌生人和蔼地说,“我迷了路,非常需要朋友的指点,你可别害怕,”他殷勤地加上这么一句.“你大胆说好了,告诉我你叫什么名字,依你看我能不能在你们家里住一夜,好让我明天一大早再到林子里去打猎。"

整整一个夏天,这头老母牛几乎没有一天晚上,是自动走到牛栏跟前等人来开门的;相反,把自己藏在越桔丛里成了它最大的快乐。虽然它脖子上挂有一只声音响亮的铃铛,但是她已经发现:只要站定了一动不动,这只铃铛就不会出声。这样一来,西尔维亚就得费好大的劲儿来找它了.小姑娘嘴里不断发出“牛啊!牛!”的呼唤,却从来听不见一次“哞"的应和声.找啊找啊,小姑娘几乎都快失去了儿童有限的耐心。要不是这头牲口奶的质量好,产量也高,主人们是绝对不会这么迁就它的。而且反正西尔维亚有的是时间,她正犯愁不知怎样打发呢。有时候,遇到天气好,把牛的恶作剧看成一次饶有兴味的捉迷藏游戏,倒也可以解解闷儿.

摘草莓的季节眼看就要到了,西尔维亚是个摘草莓的好帮手。那头母牛出的奶不错,可是要看住它可真够费事的.女主人絮絮叨叨地说个没完,倒是很直爽。接着她又告诉客人,她埋葬过四个子女,因此西尔维亚她妈以及搬到加利福尼亚去的一个儿子(ห้องสมุดไป่ตู้不知是死是活)就成了她仅存的两个孩子了。“我那个儿子阿丹,他的枪法可准了,”她伤心地解释道,“只要他在家,我从不短缺山鸡和松鼠。我琢磨他这人坐不住,又不爱写信.唉,我倒也不想责怪他.要是我年轻那会儿走得动,我也是要到处走走去见世面的。”

Awhiteheron(英文原版)(可编辑修改word版)

A WHITE HERONSarah Orne JewettI.The woods were already filled with shadows one June evening, just before eight o'clock, though a bright sunset still glimmered faintly among the trunks of the trees. A little girl was driving home her cow, a plodding, dilatory, provoking creature in her behavior, but a valued companion for all that. They were going away from whatever light there was, and striking deep into the woods, but their feet were familiar with the path, and it was no matter whether their eyes could see it or not.There was hardly a night the summer through when the old cow could be found waiting at the pasture bars; on the contrary, it was her greatest pleasure to hide herself away among the huckleberry bushes, and though she wore a loud bell she had made the discovery that if one stood perfectly still it would not ring. So Sylvia had to hunt for her until she found her, and call Co' ! Co' ! with never an answering Moo, until her childish patience was quite spent. If the creature had not given good milk and plenty of it, the case would have seemed very different to her owners. Besides, Sylvia had all the time there was, and very little use to make of it. Sometimes in pleasant weather it was a consolation to look upon the cow's pranks as an intelligent attempt to play hide and seek, and as the child had no playmates she lent herself to this amusement with a good deal of zest. Though this chase had been so long that the wary animal herself had given an unusual signal of her whereabouts, Sylvia had only laughed when she came upon Mistress Moolly at the swamp-side, and urged her affectionately homeward with a twig of birch leaves. The old cow was not inclined to wander farther, she even turned in the right direction for once as they left the pasture, and stepped along the road at a good pace. She was quite ready to be milked now, and seldom stopped to browse. Sylvia wondered what her grandmother would say because they were so late. It was a great while since she had left home at half-past five o'clock, but everybody knew the difficulty of making this errand a short one. Mrs. Tilley had chased the hornéd torment too many summer evenings herself to blame any one else for lingering, and was only thankful as she waited that she had Sylvia, nowadays, to give such valuable assistance. The good woman suspected that Sylvia loitered occasionally on her own account; there never was such a child for straying about out-of-doors since the world was made! Everybody said that it was a good change for a little maid who had tried to grow for eight years in a crowded manufacturing town, but, as for Sylvia herself, it seemed as if she never had been alive at all before she came to live at the farm. She thought often with wistful compassion of a wretched geranium that belonged to a town neighbor."'Afraid of folks,'" old Mrs. Tilley said to herself, with a smile, after she had made the unlikely choice of Sylvia from her daughter's houseful of children, and was returning to the farm. "'Afraid of folks,' they said! I guess she won't be troubled no great with 'em up to the old place!" When they reached the door of the lonely house and stopped to unlock it, and the cat came to purr loudly, and rub against them, a deserted pussy, indeed, but fat with young robins, Sylvia whispered that this was a beautiful place to live in, and she never should wish to go home.The companions followed the shady wood-road, the cow taking slow steps and the child very fast ones. The cow stopped long at the brook to drink, as if the pasture were not half a swamp, and Sylvia stood still and waited, letting her bare feet cool themselves in the shoal water, whilethe great twilight moths struck softly against her. She waded on through the brook as the cow moved away, and listened to the thrushes with a heart that beat fast with pleasure. There was a stirring in the great boughs overhead. They were full of little birds and beasts that seemed to be wide awake, and going about their world, or else saying good-night to each other in sleepy twitters. Sylvia herself felt sleepy as she walked along. However, it was not much farther to the house, and the air was soft and sweet. She was not often in the woods so late as this, and it made her feel as if she were a part of the gray shadows and the moving leaves. She was just thinking how long it seemed since she first came to the farm a year ago, and wondering if everything went on in the noisy town just the same as when she was there, the thought of the great red-faced boy who used to chase and frighten her made her hurry along the path to escape from the shadow of the trees.Suddenly this little woods-girl is horror-stricken to hear a clear whistle not very far away. Not a bird's-whistle, which would have a sort of friendliness, but a boy's whistle, determined, and somewhat aggressive. Sylvia left the cow to whatever sad fate might await her, and stepped discreetly aside into the bushes, but she was just too late. The enemy had discovered her, and called out in a very cheerful and persuasive tone, "Halloa, little girl, how far is it to the road?" and trembling Sylvia answered almost inaudibly, "A good ways."She did not dare to look boldly at the tall young man, who carried a gun over his shoulder, but she came out of her bush and again followed the cow, while he walked alongside."I have been hunting for some birds," the stranger said kindly, "and I have lost my way, and need a friend very much. Don't be afraid," he added gallantly. "Speak up and tell me what your name is, and whether you think I can spend the night at your house, and go out gunning early in the morning."Sylvia was more alarmed than before. Would not her grandmother consider her much to blame? But who could have foreseen such an accident as this? It did not seem to be her fault, and she hung her head as if the stem of it were broken, but managed to answer "Sylvy," with much effort when her companion again asked her name.Mrs. Tilley was standing in the doorway when the trio came into view. The cow gave a loud moo by way of explanation."Yes, you'd better speak up for yourself, you old trial! Where'd she tucked herself away this time, Sylvy?" But Sylvia kept an awed silence; she knew by instinct that her grandmother did not comprehend the gravity of the situation. She must be mistaking the stranger for one of the farmer-lads of the region.The young man stood his gun beside the door, and dropped a lumpy game-bag beside it; then he bade Mrs. Tilley good-evening, and repeated his wayfarer's story, and asked if he could have a night's lodging."Put me anywhere you like," he said. "I must be off early in the morning, before day; but I am very hungry, indeed. You can give me some milk at any rate, that's plain.""Dear sakes, yes," responded the hostess, whose long slumbering hospitality seemed to be easily awakened. "You might fare better if you went out to the main road a mile or so, but you're welcome to what we've got. I'll milk right off, and you make yourself at home. You can sleep on husks or feathers," she proffered graciously. "I raised them all myself. There's good pasturing for geese just below here towards the ma'sh. Now step round and set a plate for the gentleman, Sylvy!" And Sylvia promptly stepped. She was glad to have something to do, and she was hungry herself.It was a surprise to find so clean and comfortable a little dwelling in this New England wilderness. The young man had known the horrors of its most primitive housekeeping, and the dreary squalor of that level of society which does not rebel at the companionship of hens. This was the best thrift of an old-fashioned farmstead, though on such a small scale that it seemed like a hermitage. He listened eagerly to the old woman's quaint talk, he watched Sylvia's pale face and shining gray eyes with ever growing enthusiasm, and insisted that this was the best supper he had eaten for a month, and afterward the new-made friends sat down in the door-way together while the moon came up.Soon it would be berry-time, and Sylvia was a great help at picking. The cow was a good milker, though a plaguy thing to keep track of, the hostess gossiped frankly, adding presently that she had buried four children, so Sylvia's mother, and a son (who might be dead) in California were all the children she had left. "Dan, my boy, was a great hand to go gunning," she explained sadly. "I never wanted for pa'tridges or gray squer'ls while he was to home. He's been a great wand'rer, I expect, and he's no hand to write letters. There, I don't blame him, I'd ha' seen the world myself if it had been so I could."Sylvy takes after him," the grandmother continued affectionately, after a minute's pause. "There ain't a foot o' ground she don't know her way over, and the wild creaturs counts her one o' themselves. Squer'ls she'll tame to come an' feed right out o' her hands, and all sorts o' birds. Last winter she got the jay-birds to bangeing here, and I believe she'd 'a' scanted herself of her own meals to have plenty to throw out amongst 'em, if I hadn't kep' watch. Anything but crows, I tell her, I'm willin' to help support -- though Dan he had a tamed one o' them that did seem to have reason same as folks. It was round here a good spell after he went away. Dan an' his father they didn't hitch, -- but he never held up his head ag'in after Dan had dared him an' gone off."The guest did not notice this hint of family sorrows in his eager interest in something else."So Sylvy knows all about birds, does she?" he exclaimed, as he looked round at the little girl who sat, very demure but increasingly sleepy, in the moonlight. "I am making a collection of birds myself. I have been at it ever since I was a boy." (Mrs. Tilley smiled.) "There are two or three very rare ones I have been hunting for these five years. I mean to get them on my own ground if they can be found.""Do you cage 'em up?" asked Mrs. Tilley doubtfully, in response to this enthusiastic announcement."Oh no, they're stuffed and preserved, dozens and dozens of them," said the ornithologist, "and I have shot or snared every one myself. I caught a glimpse of a white heron a few miles from here on Saturday, and I have followed it in this direction. They have never been found in this district at all. The little white heron, it is," and he turned again to look at Sylvia with the hope of discovering that the rare bird was one of her acquaintances.But Sylvia was watching a hop-toad in the narrow footpath."You would know the heron if you saw it," the stranger continued eagerly. "A queer tall white bird with soft feathers and long thin legs. And it would have a nest perhaps in the top of a high tree, made of sticks, something like a hawk's nest."Sylvia's heart gave a wild beat; she knew that strange white bird, and had once stolen softly near where it stood in some bright green swamp grass, away over at the other side of the woods. There was an open place where the sunshine always seemed strangely yellow and hot, where tall, nodding rushes grew, and her grandmother had warned her that she might sink in the soft blackmud underneath and never be heard of more. Not far beyond were the salt marshes just this side the sea itself, which Sylvia wondered and dreamed much about, but never had seen, whose great voice could sometimes be heard above the noise of the woods on stormy nights."I can't think of anything I should like so much as to find that heron's nest," the handsome stranger was saying. "I would give ten dollars to anybody who could show it to me," he added desperately, "and I mean to spend my whole vacation hunting for it if need be. Perhaps it was only migrating, or had been chased out of its own region by some bird of prey."Mrs. Tilley gave amazed attention to all this, but Sylvia still watched the toad, not divining, as she might have done at some calmer time, that the creature wished to get to its hole under the door-step, and was much hindered by the unusual spectators at that hour of the evening. No amount of thought, that night, could decide how many wished-for treasures the ten dollars, so lightly spoken of, would buy.The next day the young sportsman hovered about the woods, and Sylvia kept him company, having lost her first fear of the friendly lad, who proved to be most kind and sympathetic. He told her many things about the birds and what they knew and where they lived and what they did with themselves. And he gave her a jack-knife, which she thought as great a treasure as if she were a desert-islander. All day long he did not once make her troubled or afraid except when he brought down some unsuspecting singing creature from its bough. Sylvia would have liked him vastly better without his gun; she could not understand why he killed the very birds he seemed to like so much. But as the day waned, Sylvia still watched the young man with loving admiration. She had never seen anybody so charming and delightful; the woman's heart, asleep in the child, was vaguely thrilled by a dream of love. Some premonition of that great power stirred and swayed these young creatures who traversed the solemn woodlands with soft-footed silent care. They stopped to listen to a bird's song; they pressed forward again eagerly, parting the branches -- speaking to each other rarely and in whispers; the young man going first and Sylvia following, fascinated, a few steps behind, with her gray eyes dark with excitement.She grieved because the longed-for white heron was elusive, but she did not lead the guest, she only followed, and there was no such thing as speaking first. The sound of her own unquestioned voice would have terrified her -- it was hard enough to answer yes or no when there was need of that. At last evening began to fall, and they drove the cow home together, and Sylvia smiled with pleasure when they came to the place where she heard the whistle and was afraid only the night before.II.Half a mile from home, at the farther edge of the woods, where the land was highest, a great pine-tree stood, the last of its generation. Whether it was left for a boundary mark, or for what reason, no one could say; the woodchoppers who had felled its mates were dead and gone long ago, and a whole forest of sturdy trees, pines and oaks and maples, had grown again. But the stately head of this old pine towered above them all and made a landmark for sea and shore miles and miles away. Sylvia knew it well. She had always believed that whoever climbed to the top of it could see the ocean; and the little girl had often laid her hand on the great rough trunk and looked up wistfully at those dark boughs that the wind always stirred, no matter how hot and still the air might be below. Now she thought of the tree with a new excitement, for why, if one climbed it at break of day, could not one see all the world, and easily discover from whence the white heronflew, and mark the place, and find the hidden nest?What a spirit of adventure, what wild ambition! What fancied triumph and delight and glory for the later morning when she could make known the secret! It was almost too real and too great for the childish heart to bear.All night the door of the little house stood open and the whippoorwills came and sang upon the very step. The young sportsman and his old hostess were sound asleep, but Sylvia's great design kept her broad awake and watching. She forgot to think of sleep. The short summer night seemed as long as the winter darkness, and at last when the whippoorwills ceased, and she was afraid the morning would after all come too soon, she stole out of the house and followed the pasture path through the woods, hastening toward the open ground beyond, listening with a sense of comfort and companionship to the drowsy twitter of a half-awakened bird, whose perch she had jarred in passing. Alas, if the great wave of human interest which flooded for the first time this dull little life should sweep away the satisfactions of an existence heart to heart with nature and the dumb life of the forest!There was the huge tree asleep yet in the paling moonlight, and small and silly Sylvia began with utmost bravery to mount to the top of it, with tingling, eager blood coursing the channels of her whole frame, with her bare feet and fingers, that pinched and held like bird's claws to the monstrous ladder reaching up, up, almost to the sky itself. First she must mount the white oak tree that grew alongside, where she was almost lost among the dark branches and the green leaves heavy and wet with dew; a bird fluttered off its nest, and a red squirrel ran to and fro and scolded pettishly at the harmless housebreaker. Sylvia felt her way easily. She had often climbed there, and knew that higher still one of the oak's upper branches chafed against the pine trunk, just where its lower boughs were set close together. There, when she made the dangerous pass from one tree to the other, the great enterprise would really begin.She crept out along the swaying oak limb at last, and took the daring step across into the old pine-tree. The way was harder than she thought; she must reach far and hold fast, the sharp dry twigs caught and held her and scratched her like angry talons, the pitch made her thin little fingers clumsy and stiff as she went round and round the tree's great stem, higher and higher upward. The sparrows and robins in the woods below were beginning to wake and twitter to the dawn, yet it seemed much lighter there aloft in the pine-tree, and the child knew she must hurry if her project were to be of any use.The tree seemed to lengthen itself out as she went up, and to reach farther and farther upward. It was like a great main-mast to the voyaging earth; it must truly have been amazed that morning through all its ponderous frame as it felt this determined spark of human spirit wending its way from higher branch to branch. Who knows how steadily the least twigs held themselves to advantage this light, weak creature on her way! The old pine must have loved his new dependent. More than all the hawks, and bats, and moths, and even the sweet voiced thrushes, was the brave, beating heart of the solitary gray-eyed child. And the tree stood still and frowned away the winds that June morning while the dawn grew bright in the east.Sylvia's face was like a pale star, if one had seen it from the ground, when the last thorny bough was past, and she stood trembling and tired but wholly triumphant, high in the tree-top. Yes, there was the sea with the dawning sun making a golden dazzle over it, and toward that glorious east flew two hawks with slow-moving pinions. How low they looked in the air from that height when one had only seen them before far up, and dark against the blue sky. Their grayfeathers were as soft as moths; they seemed only a little way from the tree, and Sylvia felt as if she too could go flying away among the clouds. Westward, the woodlands and farms reached miles and miles into the distance; here and there were church steeples, and white villages, truly it was a vast and awesome worldThe birds sang louder and louder. At last the sun came up bewilderingly bright. Sylvia could see the white sails of ships out at sea, and the clouds that were purple and rose-colored and yellow at first began to fade away. Where was the white heron's nest in the sea of green branches, and was this wonderful sight and pageant of the world the only reward for having climbed to such a giddy height? Now look down again, Sylvia, where the green marsh is set among the shining birches and dark hemlocks; there where you saw the white heron once you will see him again; look, look!a white spot of him like a single floating feather comes up from the dead hemlock and grows larger, and rises, and comes close at last, and goes by the landmark pine with steady sweep of wing and outstretched slender neck and crested head. And wait! wait! do not move a foot or a finger, little girl, do not send an arrow of light and consciousness from your two eager eyes, for the heron has perched on a pine bough not far beyond yours, and cries back to his mate on the nest and plumes his feathers for the new day!The child gives a long sigh a minute later when a company of shouting cat-birds comes also to the tree, and vexed by their fluttering and lawlessness the solemn heron goes away. She knows his secret now, the wild, light, slender bird that floats and wavers, and goes back like an arrow presently to his home in the green world beneath. Then Sylvia, well satisfied, makes her perilous way down again, not daring to look far below the branch she stands on, ready to cry sometimes because her fingers ache and her lamed feet slip. Wondering over and over again what the stranger would say to her, and what he would think when she told him how to find his way straight to the heron's nest."Sylvy, Sylvy!" called the busy old grandmother again and again, but nobody answered, and the small husk bed was empty and Sylvia had disappeared.The guest waked from a dream, and remembering his day's pleasure hurried to dress himself that it might sooner begin. He was sure from the way the shy little girl looked once or twice yesterday that she had at least seen the white heron, and now she must really be made to tell. Here she comes now, paler than ever, and her worn old frock is torn and tattered, and smeared with pine pitch. The grandmother and the sportsman stand in the door together and question her, and the splendid moment has come to speak of the dead hemlock-tree by the green marsh.But Sylvia does not speak after all, though the old grandmother fretfully rebukes her, and the young man's kind, appealing eyes are looking straight in her own. He can make them rich with money; he has promised it, and they are poor now. He is so well worth making happy, and he waits to hear the story she can tell.No, she must keep silence! What is it that suddenly forbids her and makes her dumb? Has she been nine years growing and now, when the great world for the first time puts out a hand to her, must she thrust it aside for a bird's sake? The murmur of the pine's green branches is in her ears, she remembers how the white heron came flying through the golden air and how they watched the sea and the morning together, and Sylvia cannot speak; she cannot tell the heron's secret and give its life away.Dear loyalty, that suffered a sharp pang as the guest went away disappointed later in the day, that could have served and followed him and loved him as a dog loves! Many a night Sylviaheard the echo of his whistle haunting the pasture path as she came home with the loitering cow. She forgot even her sorrow at the sharp report of his gun and the sight of thrushes and sparrows dropping silent to the ground, their songs hushed and their pretty feathers stained and wet with blood. Were the birds better friends than their hunter might have been, -- who can tell? Whatever treasures were lost to her, woodlands and summer-time, remember! Bring your gifts and graces and tell your secrets to this lonely country child!。

awhiteheron中英文对照

awhiteheron中英文对照A White Heron - 高雅与牺牲在Sarah Orne Jewett的短篇小说《A White Heron》中,作者呈现了一个年轻女孩辛苦寻找自我真实和与自然界的和谐之间的内心斗争。

小说凭借其独特的写作风格和戏剧性冲突,引起了广泛的关注。

本文将对《A White Heron》进行中英文对照,并探讨其中所体现出来的主题以及与现实生活的联系。

故事背景发生在乡村,讲述了一个被称为Sylvia的10岁女孩的故事。

她被性格活泼的小牧羊女黛西邀请来家中住宿。

一天,黛西发现了一只稀有的白鹭鸟,于是她向Sylvia提出了一项挑战:如果Sylvia能够帮助她找到这只白鹭鸟,她将把她最喜欢的红颈手链送给Sylvia作为奖励。

Sylvia面临着两难选择。

一方面,她对黛西的友谊和承诺感到欣喜,另一方面,她融入自然的渴望在内心深处萌发。

这种渴望促使她保护这种美丽的鸟类,因为她觉得自己与自然界联系更加紧密。

在探索过程中,Sylvia逐渐与白鹭鸟产生情感纽带,感受到了自然的力量和冲突的呼唤。

作者运用描写细腻的叙述手法,将读者带入故事的情境中。

她描绘了可爱的乡村风景,让读者能够身临其境地感受到大自然的美妙。

作者使用了大量的形容词,如“宽敞的农田”、“新鲜的空气”和“浓郁的芬芳”,以强调自然的恩赐和美丽。

这种细致入微的描写使读者对Sylvia内心的挣扎与成长有了更为深入的了解。

在整个故事中,黛西扮演着一个引导者的角色。

她代表了世俗的渴望和物质的诱惑。

黛西笃信“报酬即是成功”,她对白鹭的热情主要是因为它的珍贵和价值。

她视纯洁和理想主义为一种牺牲,她在追求物质利益的同时,忽略了与自然和谐的重要性。

Sylvia则代表了大自然和纯洁的力量。

她的内心和行动显示出对生态平衡和持续发展的尊重。

她乐于与自然保持联系,并在黛西和家庭的诱惑面前毅然选择了自然的价值。

在独自一人走进森林的过程中,Sylvia体会到了自然界的庄严和神圣。

文学选读与批评a white heron

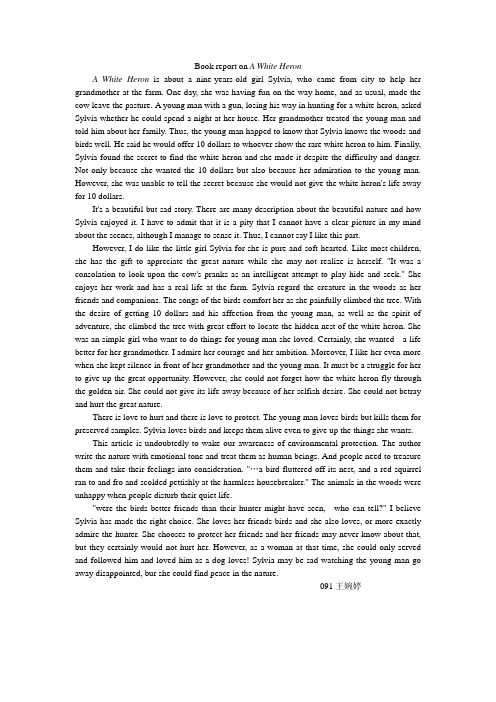

Book report on A White HeronA White Heron is about a nine-years-old girl Sylvia, who came from city to help her grandmother at the farm. One day, she was having fun on the way home, and as usual, made the cow leave the pasture. A young man with a gun, losing his way in hunting for a white heron, asked Sylvia whether he could spend a night at her house. Her grandmother treated the young man and told him about her family. Thus, the young man happed to know that Sylvia knows the woods and birds well. He said he would offer 10 dollars to whoever show the rare white heron to him. Finally, Sylvia found the secret to find the white heron and she made it despite the difficulty and danger. Not only because she wanted the 10 dollars but also because her admiration to the young man. However, she was unable to tell the secret because she would not give the white heron's life away for 10 dollars.It's a beautiful but sad story. There are many description about the beautiful nature and how Sylvia enjoyed it. I have to admit that it is a pity that I cannot have a clear picture in my mind about the scenes, although I manage to sense it. Thus, I cannot say I like this part.However, I do like the little girl Sylvia for she is pure and soft-hearted. Like most children, she has the gift to appreciate the great nature while she may not realize is herself. "It was a consolation to look upon the cow's pranks as an intelligent attempt to play hide and seek." She enjoys her work and has a real life at the farm. Sylvia regard the creature in the woods as her friends and companions. The songs of the birds comfort her as she painfully climbed the tree. With the desire of getting 10 dollars and his affection from the young man, as well as the spirit of adventure, she climbed the tree with great effort to locate the hidden nest of the white heron. She was an simple girl who want to do things for young man she loved. Certainly, she wanted a life better for her grandmother. I admire her courage and her ambition. Moreover, I like her even more when she kept silence in front of her grandmother and the young man. It must be a struggle for her to give up the great opportunity. However, she could not forget how the white heron fly through the golden air. She could not give its life away because of her selfish desire. She could not betray and hurt the great nature.There is love to hurt and there is love to protect. The young man loves birds but kills them for preserved samples. Sylvia loves birds and keeps them alive even to give up the things she wants.This article is undoubtedly to wake our awareness of environmental protection. The author write the nature with emotional tone and treat them as human beings. And people need to treasure them and take their feelings into consideration. "…a bird fluttered off its nest, and a red squirrel ran to and fro and scolded pettishly at the harmless housebreaker." The animals in the woods were unhappy when people disturb their quiet life."were the birds better friends than their hunter might have seen,---who can tell?" I believe Sylvia has made the right choice. She loves her friends birds and she also loves, or more exactly admire the hunter. She chooses to protect her friends and her friends may never know about that, but they certainly would not hurt her. However, as a woman at that time, she could only served and followed him and loved him as a dog loves! Sylvia may be sad watching the young man go away disappointed, bur she could find peace in the nature.091王婉婷。

a white heron赏析

a white heron赏析

A White Heron《一只白苍鹭》是美国著名女作家萨拉·奥恩·朱厄特于1886年发表的一篇短篇小说。

《一只白苍鹭》是一部讲述了人与自然关系的佳作。

作家运用清新的文学语言,让读者从女主人公竭尽全力保护这只白苍鹭的故事中,深深体味到了人与自然之间和谐共处的生态美景。

因此,有生态女性主义评论家把《一只白苍鹭》看作是一幅经典的“风俗画”。

作家通过这部小说的创作,清晰地表达了自己浓烈的乡土情结、深厚的家园意识以及期待人与自然和谐相处的永恒追求。

这部小说中所蕴含的生态女性意识,让读者了解女性与自然之间的亲密关系,并唤起男权制社会下女性意识的觉醒,从而表达作家浓烈的乡土情结、深厚的家园意识以及人与自然和谐相处的永恒追求。

a white heron课文

a white heron课文

《白鹭》是美国作家莎拉·奥尔登·詹娜普尔于1886年发表的短篇

小说,描写了一个年轻女孩帕默奇在森林中偶遇一只白鹭,她最初为了钱

而打算告诉一个男人白鹭的位置,但最终又改变了主意,选择保护白鹭,

表达出对自然和生命的敬畏之情。

在这个转折点上,帕默奇面临着一场内心战争:背叛自己的白鹭朋友,或是坚守自己的信念。

最终,她决定不告诉男人白鹭的位置。

她意识到,

友谊和生命比金钱更为重要。

小说的结尾,帕默奇站在高处,鸟儿飞翔,她惊喜地看到白鹭的飞翔,离她越来越近,她开始感到兴奋和喜悦。

这只白鹭象征着友谊和自由,正

如帕默奇的内心自由和坚定的信念。

此时,她认为,自己的内心已经和白

鹭一样,自由闲适,不再屈服于诱惑和利益的暴力。

小说通过帕默奇的故

事告诉人们,珍惜自然资源,珍惜每一个生命,追求自由和和平,是人与

自然,人与人之间必须坚守的道德底线。

总体上来说,这篇小说展现出了对自然界的赞美和珍惜,以及对人性

的深刻思考。

白鹭作为象征和角色,是对人性本质和自由的呼唤。

通过帕

默奇的选择和成长,人们得以看到珍惜大自然、珍惜生命和追求自由和平

的重要性。

这个故事在当今仍然具有深刻的道德意义,值得我们珍惜生命,保护环境,珍惜和平。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

2016年11月上青春岁月“硕大”、“卷”、“俨”中推断出“菡萏”的词汇意义。

7、鸳鸯《续一切经音义·新花严经卷第七》:上(鸳)于袁反,下(鸯)于姜反,《毛诗》曰:“鸳鸯干飞。

”传曰:“鸳鸯,疋鸟也,言其止为疋,偶飞则双飞。

”《说文》从夗央,皆形声字也。

《诗经·小雅·鸳鸯》:鸳鸯于飞,毕之罗之。

君子万年,福禄宜之。

鸳鸯在梁,戢其左翼。

君子万年,宜其遐福。

据《续一切经音义》所言,“鸳鸯”是一种飞行的鸟类,其文字上来说是形声字。

《诗经·小雅·鸳鸯》两句采用“鸳鸯”起兴,“在飞”、“在梁”都明示“鸳鸯”为飞鸟。

二、结语希麟《续一切经音义》引《诗经》的词汇主要集中在动物、植物、农事、祭祀等方面,这与《诗经》产生的年代以及其主要内容有关。

而在引用《诗经》的同时,《续一切经音义》还引用了很多训诂专书,如《字林》、《说文解字》等,所以我们在找出《续一切经音义》中引用《诗经》的内容后,即可藉助其他字书进行勘误,这是大有裨益的。

《续一切经音义》内容广泛,涵盖了太多知识,我们作为文字学的学生要多加学习,在训诂、音韵、文字方面多多注意。

【参考文献】[1] 希 麟. 续一切经音义[M]. 上海古籍出版社, 1987.[2] 李 青, 编. 诗经[M]. 北京联合出版公司, 2015.[3] 朱杰人, 李慧玲. 毛诗注疏[M]. 上海古籍出版社, 2013.【作者简介】刘雨荷(1993—),女,汉族,四川成都人,四川大学文新学院学生,主要研究方向:汉语言文字学。

>>(上接第06页)When I read the beginning of A White Heron, I was greatly attracted by the purity and innocence of Sylvia, the protagonist in this story. Through reading it, I have found so many brilliant ideas implicit in the text. The most two significant ideas portrayed in the text are the value of difficulties and the power of nature.To begin with, the author clarifies the idea that difficulties create opportunities for us by describing an adventure taken by a small girl, Sylvia. On her way, she has to go through difficulties which are beyond her imagination. “The sharp dry twigs caught and held her and scratched her like angry talons”(90). However, having overcome these difficulties, Sylvia succeeds in reaching the top of the huge pine tree, where she sees a fantastic view and gains a better understanding of herself. She sees “here and there were church steeples, and white villages; truly it was a vast and awesome world” (91).At this moment, she realizes that hurting the white heron is not what she truly hopes; thus, she decides to protect it by saying nothing. It is these difficulties that create the opportunity for her to understand herself. If she does not take the challenge to explore through the forest, she would not experience the wonder of nature and discover her true identity: an innocent child of nature.As a saying goes, “There is no pleasure without pain.”Sylvia acquires a feast for her eyes and a true self after experiencing difficulties, which proves that difficulties and pain bring more opportunities to improve ourselves. When I first came to America from China, the different culture, language, and teaching system all brought pain to me. I, nevertheless, can at present fully understand professors’lectures, fluently communicate with other people in English, and easily catch up with my American classmates. For all these, I should be grateful to those difficulties, for they have trained my will and improved my competence. Therefore, my personal experiences cause me to definitely agree with the author. Difficulties create more opportunities to improve ourselves in physical and mental aspects. Through difficulties, Sylvia finds the “pageant of the world” (92) and decides to be loyal to herself, keeping silence “for a bird’s sake” (92). Likewise, we can also make much progress after going through difficulties. There are infinite possibilities behind difficulties.In addition, the author implicitly describes that nature is powerful, for nature is not only a provider but also a leader. Nature provides a wonderful sight for Sylvia: “there was the sea with the dawning sun making a golden dazzle over it” (91). Everything looks amazing to her, and she is astounded by the beauty. Nature shows a fantastic spectacle to her. Moreover, nature leads her to find her true identity through experiencing and feeling it. Initially, she begins the exploration in order to discover the white heron and to please her friend, on whom she has a crush; but after this adventure, she has changed her mind: “she cannot tell the heron’s secret and give its life away”(92). She no longer blindly subordinates herself to that boy; instead, she finds her true self and her love for nature. She will not betray her true thoughts and values, even if it means that she will get the rebuke from her grandmother and bear the departure of that boy.Nature creates various creatures on the earth and provides a colorful world and leads us to retrieve the selves who are lost in human society. Thanks to nature, Sylvia witnesses the beauty beyond description and gets her true identity back. “It seemed that as if she never had been alive at all before” (85). Just like her, each of us can find a different world and our true selves in nature. When we are tired of those high buildings and heavy traffic in modern life, we can get close to nature, where we can see the harmonious scenery and enjoy the atmosphere of tranquility. When we find we are lost in social life, we can go on a date with nature, where we can well explore our hearts and regain our initial and truest selves. Nature is always there. When we turn back, we will always see nature. Nature is our loyal friend: she creates amazing scenes to rejoice us and gives sincere advice to us. With the company of nature, we, like Sylvia, can live our lives without dissembling our true characters. In short, nature can provide us big spectacles and lead us to better understand ourselves.All in all, two crucial ideas are depicted by writing this story: difficulties are valuable, and nature is powerful. The author teaches us to positively deal with difficulties, because we can improve ourselves by overcoming them; she tells us to get close to nature, because we can enjoy ourselves and discover true selves in nature. We will live a much better life if we take the two ideas seriously. These two themes are everlasting truths. They are applicable for not only us but also our descendants, not only this generation but also endless ones.【Reference】[1] Paul Negri. Great American Short Stories[M]. Dover Publications, 2002:85-92.A White Heron□ 白玉杰(兰州理工大学, 甘肃 兰州 730050)Abstract:Not only do we read this story for fun, but also we learn profound lessons from it. A White Heron leads us into a positive, pure world, revealing the influence of difficulties and mightiness of nature before us.Key words:difficulties; nature; lessons07。