重力模型

2000重力场模型求正常重力

2000重力场模型求正常重力正常重力是地球表面上物体受到的重力加速度,通常被定义为9.8 m/s²。

这个数值是根据重力场模型推导出来的,而重力场模型是描述地球上物体受到的重力力场的数学模型。

重力场模型是基于牛顿的万有引力定律建立的。

根据万有引力定律,两个物体之间的引力与它们质量的乘积成正比,与它们之间距离的平方成反比。

而地球上的重力场是由地球的质量分布所引起的。

在重力场模型中,地球被假设为一个完全球对称的物体,其质量均匀分布在球心。

根据这个假设,可以推导出在地球表面上的物体受到的重力加速度与离地球球心距离的平方成反比。

而由于地球的形状是略微扁球形的,所以这个重力加速度在地球不同的地方会略有不同。

重力场模型还考虑了地球自转对重力加速度的影响。

由于地球自转,地球上的物体会受到离心力的作用,此离心力会使重力加速度在赤道附近稍微减小,而在极地附近稍微增大。

这就是为什么赤道上的物体相对于极地上的物体所受到的重力稍微减小的原因。

除了地球的自转,重力场模型还考虑了地球上的地形对重力加速度的影响。

由于地球上存在地形起伏,不同地方的海拔高度不同,这也会对重力加速度产生影响。

一般来说,海拔越高,离地球球心的距离就会增加,因此重力加速度会稍微减小。

同时,地球上的重力场还受到地下物体的影响,例如地下的岩石和水体等,这些物体也会对重力加速度产生微弱的影响。

根据重力场模型,我们可以计算出地球上不同地方的重力加速度。

一般来说,地球表面上的重力加速度大约为9.8 m/s²,但实际上它在不同地方会略有差异。

例如在赤道附近,重力加速度约为9.78 m/s²,而在极地附近则约为9.83 m/s²。

同时,在海拔高度较高的地方,重力加速度也会稍微减小。

正常重力是地球上物体受到的重力加速度,它是根据重力场模型推导出来的。

重力场模型考虑了地球的球形、自转、地形和地下物体对重力加速度的影响,因此地球上的重力加速度在不同地方会略有不同。

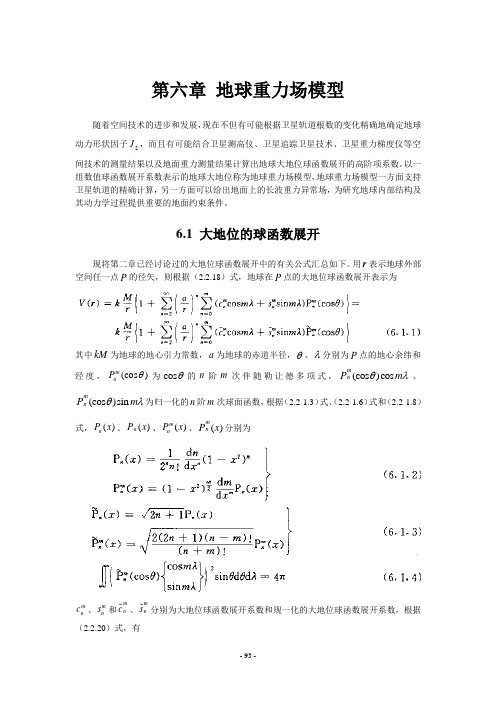

第六章——地球重力场模型

第六章 地球重力场模型随着空间技术的进步和发展,现在不但有可能根据卫星轨道根数的变化精确地确定地球动力形状因子2J ,而且有可能结合卫星测高仪、卫星追踪卫星技术、卫星重力梯度仪等空间技术的测量结果以及地面重力测量结果计算出地球大地位球函数展开的高阶项系数。

以一组数值球函数展开系数表示的地球大地位称为地球重力场模型,地球重力场模型一方面支持卫星轨道的精确计算,另一方面可以给出地面上的长波重力异常场,为研究地球内部结构及其动力学过程提供重要的地面约束条件。

6.1 大地位的球函数展开现将第二章已经讨论过的大地位球函数展开中的有关公式汇总如下。

用r 表示地球外部空间任一点P 的径矢,则根据(2.2.18)式,地球在P 点的大地位球函数展开表示为其中kM 为地球的地心引力常数,a 为地球的赤道半径,θ、λ分别为P 点的地心余纬和经度,(cos )mn P θ为cos θ的n 阶m 次伴随勒让德多项式,(cos )cos mn P m θλ、(cos )sin mn P m θλ为归一化的n 阶m 次球面函数,根据(2.2-1.3)式、(2.2-1.6)式和(2.2-1.8)式,()n P x 、()n P x 、()mn P x 、()mn P x 分别为m n c 、m n s 和mn c 、mn s 分别为大地位球函数展开系数和规一化的大地位球函数展开系数,根据(2.2.20)式,有根据(2.3.4)式、(2.3.5)式,大地位二阶球函数展开系数等于其中A 、B 、C 分别为地球绕1Ox 、2Ox 和其旋转轴3Ox 轴的转动惯量,12I 、23I 、13I 分别为地球绕相应轴的惯性积,大地位球函数展开有时写成下面的形式nm J 、nm K 与大地位球函数展开系数m n c 、m n s 之间的关系为2J 称为地球的动力形状因子。

当3n 时,()n P x 、()mn P x 的表达式如表6.1.1所示。

第三节重力模型法精品PPT课件

重力模型法(GM)认为交通区i到j的出行分布量 不仅与社会经济因素有关(驱动因素),而且还与时 间、空间等阻碍因素有关。

重力模型的基本公式为:

Pi Pj

tij k

d

2 ij

Casey模型

tij

k

Oi D j Cij

tij

k

Oi Dj Cij

其中, Pi,Pj——小区i,j的人口数; Oi,Dj——小区i,j的产生交通量与吸引交通量; R——小区i,j间的阻抗(距离、费用等);

缺点: ①虽考虑路网变化和土地利用对出行的影响

,但没有考虑出行者的个体因素影响; ②交通区内出 行交通量无法求出; ③若交通小区之间的距离非常小 时,有夸大预测力模型法能够考虑路网阻抗的变化,要求 数据不苛刻,因此适用范围较广,可用于各 种交通规划。

增长系数法可以作为重力模型法的补充,在 重力模型法无法满足约束条件时,可以辅助 应用(例如课本P142);也可以用于预测城 市外部交通量及公路交通量。

七模型理论解释概率论解释信息论解释最大熵原理八重力模型的特点九交通分布模型的选用重力模型法能够考虑路网阻抗的变化要求数据不苛刻因此适用范围较广可用于各种交通规划

第三节 重力模型法 (Gravity Model)

主要内容

概述 模型参数标定 无约束模型(简单模型) 单约束模型 双约束模型 模型理论解释 重力模型特点 分布模型选择

假设γ=1,下面采用乌尔希斯模型来检验其是否 合理。

交通区1:

小区1总体可达性

根据 Tij Oi •

Dj

n

Cij

D j Cij

计算小区1到各小区出行量:

j=1

82 T11 8 10 3.2

T12

重力模型PPT演示课件

qi1j

qi0j

*

(

F0 Oi

F0 Dj

)/2

计算结果如下面表所示

11

O/D 1 2 3

合计

增长系数

用平均增长系数法第一次迭代计算OD表

1 19.046 17.755

4.453 41.254

2 16.992 60.7 11.933

19.804 36.241

合计 40.541 90.405 35.554

166.500

增长系数 0.9521 1.0165 1.0125

0.9526

1.0145

1.0182

12

O/D 1 2 3

FO12 U 2 / O2 91.9 / 359.619 0.2555 FD02 V2 / D2 90.3 / 354.302 0.2549

FO13 U 3 / O3 36.0 / 138.771 0.2594 FD03 V3 / D3 36.9 / 141.152 0.2614

合计 增长系数

用平均增长系数法第三次迭代计算OD表

1 17.823 17.127

4.276

2 16.684 62.318 11.544

3 4.438 12.291 20.310

合计 38.946 91.736 36.130

q PiPj

ij

d

2 ij

Pi Pj 分别表示i小区和j小区的人口(用出行人数代替了总人数)

dij 表示i,j小区之间的距离 (用出行费用函数 f (cij ) 来表示)

5-重力模型法

束,则可得到双约束重力模型(过程略):

( ) qij = ai ⋅ bj ⋅ Oi ⋅ Dj ⋅ f cij

∑ ( )

−1

ai

=

j

bj ⋅ Dj ⋅ f

cij

∑ ( )

−1

bj = i ai ⋅ Oi ⋅ f cij

双约束重力模型可以同时满足行列约束条件,是目前使

用较多的一种重力模型。

表1 现状OD矩阵及未来发生、吸引量

1 2 3 Oi` Oi 1 4 2 2 8 16

2 2 8 4 14 28

3 2 4 4 10 40

Dj` 8 14 10 32

Dj 16 28 40

84

表2 各区之间的行程时间

123 1244 2412 3422

美国联邦公路局重力模型

模型形式为:

∑ ( ( ) ) qij = Oi ⋅

5.5 重力模型的优缺点

优点:

模型形式直观,可解释性强,易被规划人员理解和 接 受; 能比较敏感地反映交通设施变化对出行的影响,适 用于中长期需求预测; 不需要完整的基年OD矩阵,如果有可信赖的模型参 数,甚至不需要基年OD矩阵; 特定交通小区(如新开发区)之间的分布量为零时, 也能进行预测。 能比较敏感地反映交通小区之间行驶时间变化的情况。

双约束重力模型的标定

双约束重力模型中的ai与bj是在计算过程中产生的,不是固 定的参数,因而对于双约束重力模型只有阻抗函数中的参数需 要标定。在取指数型阻抗函数时,需要标定的就是参数β。

如果参数β的取值能使得由重力模型计算结果中得到的出行

长度分布,与实际调查得到的出行长度分布最大程度地吻合, 则该值就作为模型参数标定的最优值。因此重力模型的标定问 题就转化为一个方程求根的问题。可以用牛顿法等数值方法求

第三章 交通需求预测-重力模型

l 基本假设为:交通区i到交通区j的出行分布

1、无约束重力模型

l

万有引力模型

模型为:

F = K⋅

l

量与i区的出行发生量、j区的出行吸引量成正 比,与i区和j区之间的交通阻抗成反比。 根据对约束情况的不同分类,重力模型有三种 形式:无约束重力模型、单约束重力模型和双 约束重力模型。

X ij = k ⋅

可采用先考虑宏观因素预测其总比例,再考 虑微观因素预测各交通区间出行方式的分担率的 方法。 出行总比例预测 条件类方式:根据车辆拥有量进行预测。

l

竞争类方式 取决于需求的出行方式其总比例预测可根据有关的社 会经济发展目标,结合其发展实际状况,通过综合分 析求得。如出租车等。 取决于有关政策的出行方式其总比例预测可按照有关 的发展策略,根据已有基础进行规划确定,如公交车 出行等。 各交通区间的出行比例预测 各交通区间某种出行方式的出行比例取决于该出行方 式的总比例、出行目的结构和出行距离,通过前述模 型以及根据出行调查等资料统计分析拟合建立的现状 关系曲线进行预测。

其中, c:汽车(car);b:公共汽车(bus)

l

∑∑ A

j m

其中Tijm——从交通区i到交通j,第 m种交通方 式的交通量;

4、 回归模型法——产生分担组合模型

l

二、交通方式的分类

l l l l l l l

该模型是通过建立交通方式分担率与其相关因素 间的回归方程,作为预测交通方式模型。

可分为:自由类、条件类和竞争类。 1、自由类交通方式 主要指步行交通,影响因素(内在因素)包括: 出行目的、出行距离、气候条件等 2、条件类交通方式 主要指单位小汽车、单位大客车、私人小汽车、摩托 车等交通方式 影响因素(外在因素)包括:有关政策、社会、经济 的发展水平。 影响因素(内在因素)包括:车辆拥有量、出行目的、 出行距离等。

重力模型

tij

两边取对数,得

( Oi D j )

cij

ln tij ln ln( Oi D j ) ln( cij )

t ij

令:

Oi D j

c ij 已知数据

待标定参数

y ln tij

则:

a 0 ln

a1

a 2

x1 ln(Oi D j )

K ij 的计算方法为:

首先令 K ij =1,根据现状OD表标定模型,计算 。

将现状数据代入模型,计算出OD分布。

根据上面的公式计算 K ij 。

假定 K ij 的值在将来不发生变化,预测时不做任何修改而 直接使用。 标定 的方法与乌尔希斯重力模型 相同。

Oi 这两种模型均能满足出行产生约束条件,即: 此都称为单约束重力模型。

以幂指数交通阻抗函数 f (cij ) cij 为例介绍其计算方法:

第1步:令m=0,m为迭代次数;

第2步:给出

m

(可以用最小二乘法求出);

bm j 1/

第3步:令 ai 1 ,求出 b m ( j

m 1 第4步:求出 a i 和 b

m 1 j

a

i

m i Oi cij

38.6 91.9 36.0 166.5

表5

现状行驶时间

1 7.0 2 17.0 3 22.0

表6

将来行驶时间

1 4.0 2 9.0 3 11.0

c ij

1

c ij

1

2

3

17.0

22.0

15.0

23.0

23.0

7.0

2

3

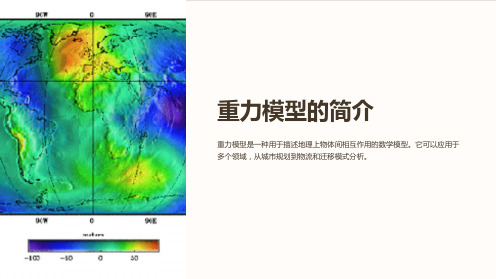

《重力模型的简介》课件

重力模型是一种用于描述地理上物体间相互作用的数学模型。它可以应用于 多个领域,从城市规划到物流和迁移模式分析。

重力模型的定义

简要阐述

重力模型是一种描述两个地理位置之间相互作用强度的数学模型。它基于物体间的距离和质 量的概念。

数学表达

重力模型公式为:F = G × (m1 × m2) / r^2,其中F是作用力,G是引力常量,m1和m2是物 体的质量,r是物体间的距离。

数据分析

运行模型,分析结果并解释模 型的预测能力。

结论和展望

结论

重力模型是一个有用的工具,可以用于解释和预测 地理上的相互作用。

展望

未来,重力模型将进一步发展和应用于更多领域, 为人类社会的发展和决策提供支持。

3

案例1

使用重力模型预测城市间的人口迁徙模 式,为城市规划和基础设施建设提供依 据。

案例3

研究不同交通网络条件下的人口流动规 律,为交通规划和交通管理提供决策支 持。

重力模型的数据分析方法

数据收集

收集相关地理和物体数据,包 括位置、质量和其他相关因素。

模型建立

基于收集的数据建立重力模型, 并设置模型参数。

影响因素

重力模型的主要参数是物体间的距离和质量,但还可以考虑其他因素,如交通网络、经济发 展水平等。

重力模型的应用领域

城市规划

物流管理

重力模型可以用于确定城市之间的规模和发展趋势, 帮助政府和规划者做出合理决策。

重力模型可用于优化货物流动的路径选择和配送策 略,提高物流效率和降低成本。

迁徙分析

通过重力模型,可以预测人口迁徙的模式和方向, 为公共政策制定和资源分配提供参考。

重力模型的基本原理

1. 引力与距离成反比 2. 引力与物体质量成正比 3. 物体间的相互作用受到其他因素的影响

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

BOSTON COLLEGEDepartment of EconomicsEC 871 Prof. Anderson International Trade TheoryTTh 1:30 Fall 2007office hours: T 3-4, Th 4:30-5:30Email: james.anderson@Web: /~anderson Tel.: 617-552-3691SyllabusCourse Requirements are: (1) a series of homework assignments(2) a mid-term exam Oct. 18(3) a final exam, date TBAThe purpose of this course is to acquaint the student with the basic tools of international trade theory. Trade theory is the richest lode of applied general equilibrium theory. To develop skill and intuition in applied ge theory, I have two sorts of homework. One sort is written mathematical and intuitive exercises. The other sort is programming exercises with simple computable general equilibrium models.Some important topics skipped here will be covered in Ec875, Political Economy of Trade and Development. These include trade and growth, the political economy of trade, and the institutions of trade. Some attention will be paid to empirical work; the Feenstra textbook is a great resource here.The reading list is small compared to many graduate reading lists. I think less is more in learning the basics. In contrast, Ec875 assumes the basics and requires extensive reading of recent papers. The reading list has more papers by me than are justified by their pure merit. This is because I can communicate more about the creation of economics in discussing the work I (probably) know best.TextbooksA.A. Dixit and V. Norman, Theory of International Trade, Cambridge UniversityPress, 1980. A key reference for core theory material:B. R. Feenstra Advanced International Trade: Theory and Evidence, 2003. It isparticularly outstanding for treatment of empirical work in the context of theory.A good theory text alternative covering Dixit and Norman’s ground is A. Woodland, International Trade and Resource Allocation, Amsterdam: North Holland, 1982.A good undergraduate text for review or supplement is Markusen, Maskus, Melvin and Kaempfer, The Theory of International Trade, Ethier, Modern International Economics,Krugman and Obstfeld, International Economics: Theory and Policy, or Caves, Frankel and Jones, World Trade and Payments.Surveys1.Surveys of International Trade, D. Greenaway and L.A. Winters eds. Oxford: BasilBlackwell, 1994. MA level surveys.2.Handbook of International Economics, Vol 1,North-Holland, eds. Jones and Kenen;Volume 3, eds Grossman and Rogoff, 1995. Graduate level surveys.3.“International Trade Theory”, JE Anderson, New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics,forthcoming (/~anderson/PalgraveTrade.pdf). Intermediate level survey.Important MonographsHelpman and Krugman, Market Structure and Foreign Trade, MIT 1985.Helpman and Grossman, Innovation and Growth in the Global Economy, MIT 1991. Anderson and Neary, Measuring the Restrictiveness of International Trade Policy, MIT 2004.G. Grossman ed, Imperfect Competition and International Trade, MIT Press, 1992. Collection of key essays.Web sites: this course teaches theory and some applications and we tend to lose sight of why we study the stuff. These sites give information on the application of ideas to the policy issues:WTO: vast amount of information about the WTO and its dispute settlement processes. (How secretive is this organization?)Trade negotiations web page: /cidtrade/ lots of news and opinion on a wide range of trade negotiation issues.USTR reports: /reports/index.html. USTR is the negotiation arm of US trade; these are its briefs for disputes.The Economist: . Lots of their current stories and opinion are free.Deardorff’s glossary of international economics terms: http://www-/~alandear/glossary/SyllabusCitations marked with an asterisk are basic starting points and fundamental to the lectures.I. Introduction and A Simplified Trade ModelReadings:*Dixit-Norman, Ch. 1.II. Supply and Demand with DualityReadings*DN, ch. 2*A. Woodland, (1980), "Direct and Indirect Trade UtilityFunctions", RES, 47,907-26.III. The Gains from TradeReadings*DN, ch. 3IV. Explorations of Special CasesA. The Ricardian Theoryreadings:*DN, Ch. 2*Dornbusch, Fischer and Samuelson, 1977, AER, “The Ricardian modelwith a continuum of goods”B.The Factor Proportions Theory1. The Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson ModelReadings:*Handbook, ch. 1*Feenstra, ch. 2*R. Jones, "The Structure of Simple GeneralEquilibrium Models," JPE Dec. 1965.*DN, ch. 42. Extensions of the ModelReadings*Ethier, W.J., "Higher Dimensional Issues in TradeTheory," Handbook.*Dixit-Norman, Chs. 2, 4.*Neary, JP and AS Schweinberger, "Factor ContentFunctions and the Theory of International Trade", RES, 1986.*Feenstra, ch. 3Dixit-Woodland, "The Relationship Between FactorEndowments and Commodity Trade," JIE, May 1982Neary, JP, 1985, "Twoness and Trade Theory", Econometrica, 53C. Empirical Work on Core Trade ModelsReadings:Do Endowments and Technology Explain Trade?*Feenstra, chs. 2,3Leamer and Levinsohn, Handbook, vol. 3.Leamer, E., Sources of International ComparativeAdvantage, M.I.T.,1984.Does Trade Affect Factor Prices?*Feenstra, ch. 4D. Trade Costsreadings:*”Gravity Lectures”, J. Anderson*”Trade Costs”, J. Anderson and E. van Wincoop, JEL, 2004.*”Gravity with Gravitas: A Solution to the Border Puzzle”, J. Andersonand E. van Wincoop, AER March 2003.J. Rauch (1999), “Networks vs. Markets in International Trade”, JIE 48, 7-37.Eaton, J. and S. Kortum (2002), “Technology, Geography and Trade”,Econometrica, 70, 1741-79.Feenstra, ch. 5.Helpman, E. M. Melitz and Y. Rubinstein (2007) “Estimating TradeFlows: Trading Partners and Trading Volumes”, NBER WP No. 12927.Arkolakis, C. (2007), “Market Access Costs and the New ConsumersMargin in International Trade”, mimeo.V. Imperfect Competition and Scale EconomiesA. Product Differentiation, Monopolistic Competition and TradeReadings: 1) *Helpman and Krugman, Chs. 6-11.*Feenstra, ch. 5J. P. Neary"Monopolistic competition and international trade theory,” in S. Brakman and B.J. Heijdra (eds.): The Monopolistic Competition Revolution in Retrospect, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 159-184.B. Division of Labor and Scale EconomiesReadings:1) *Ethier, W., "National and International Returns to Scale in the Modern Theory of International Trade" AER, June 1982, also in G. Grossman Imperfect Competition and International Trade.C. Firm Behavior, Trade and the Empirics of ProductivityReadings:Melitz, Marc (2003), “The Impact of Trade on Intra-industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity”, Econometrica, 71, 1695-1725.VI. Commercial PolicyA. TheoryReadings*Anderson, JE and JP Neary, Measuring Trade Restrictiveness, (2004) chs. 3,6,7.*Anderson, JE and JP Neary, “Welfare vs. Market Access: The Implications of Tariff Structure for Tariff Reform” (2005)(/~anderson/WelvsMktAccess.pdf)*Anderson, JE and JP Neary, “Revenue Tariff Reform”(2006),(/~anderson/RevenueTarReform.pdf).Anderson, JE, "The Theory of Protection" in D. Greenaway and LAWinters SurveysA. Dixit, "Taxation in Open Economies," Chapter inHandbook of Public FinanceB. Empirical work on Trade Policyreadings:*Feenstra, ch. 7*R. Feenstra, “Estimating the Effects of Trade Policy”, 1995 Handbook,vol. 3.Anderson and Neary Measuring Trade Restrictiveness, chs. 11, 12, 14.VII. Strategic Trade PolicyReadings:*J. Brander, "Strategic Trade Policies" in Handbook, vol. 3.*G. Maggi, “Strategic Trade Policies with Endogenous Modes ofCompetition”, AER, 1996, 237-58.Brander and Spencer, "Tariff Protection and Imperfect Competition" andEaton and Grossman, "Optimal Trade and Industrial Policy underOligopoly", chs. 6 and 7 in Grossman, Imperfect Competition andInternational Trade.J. McLaren 1997, “Size, Sunk Cost and Judge Bowker’s Objection to FreeTrade”, AER, 400-420.Anderson (2006) “Commercial Policy in a PredatoryWorld”(/~anderson/PolicyPredWorld.pdf)。