Meta分析写作

《2024年Meta分析系列之十五_Meta分析的进展与思考》范文

《Meta分析系列之十五_Meta分析的进展与思考》篇一Meta分析系列之十五_Meta分析的进展与思考Meta分析系列之十五:Meta分析的进展与思考一、引言Meta分析,作为一种重要的文献综述工具,已广泛应用于科学研究领域。

自其诞生以来,就为学者们提供了一个更为精准和系统的分析手段,来对相关领域内的众多研究进行汇总、评价和比较。

在过去的几十年里,随着科技和方法的不断进步,Meta分析也得到了长足的发展。

本文旨在探讨Meta分析的进展、现状以及未来发展方向,以期为相关研究提供参考。

二、Meta分析的进展(一)方法论的完善随着Meta分析的广泛应用,其方法论也在不断完善。

从最初的简单统计合并到现在的多层次模型、贝叶斯分析等复杂方法,Meta分析的精确性和可靠性得到了显著提高。

此外,针对特定类型的研究设计(如诊断试验、干预研究等),也发展出了相应的Meta分析方法。

(二)数据来源的扩展随着互联网和数据库技术的快速发展,Meta分析的数据来源得到了极大的扩展。

除了传统的学术期刊、会议论文等,现在还可以从网络资源、政府报告等获取数据。

同时,大数据和人工智能技术的应用也为Meta分析提供了更为丰富的数据来源。

(三)应用领域的拓展Meta分析的应用领域已经从最初的医学领域扩展到了社会科学、教育学、心理学等多个领域。

这些领域的学者们通过Meta分析对大量相关研究进行综合评价,为政策制定、教育实践等提供了有力的依据。

三、当前Meta分析的挑战与思考(一)数据质量问题随着数据来源的扩展,数据质量问题也日益凸显。

在Meta分析中,数据的质量直接影响到结果的准确性和可靠性。

因此,如何确保数据的真实性和准确性是当前Meta分析面临的重要挑战。

(二)方法论的局限性虽然Meta分析的方法论在不断完善,但仍存在一些局限性。

例如,对于某些特殊类型的研究设计(如定性研究、混合方法研究等),现有的Meta分析方法可能无法完全适用。

meta分析写作要点

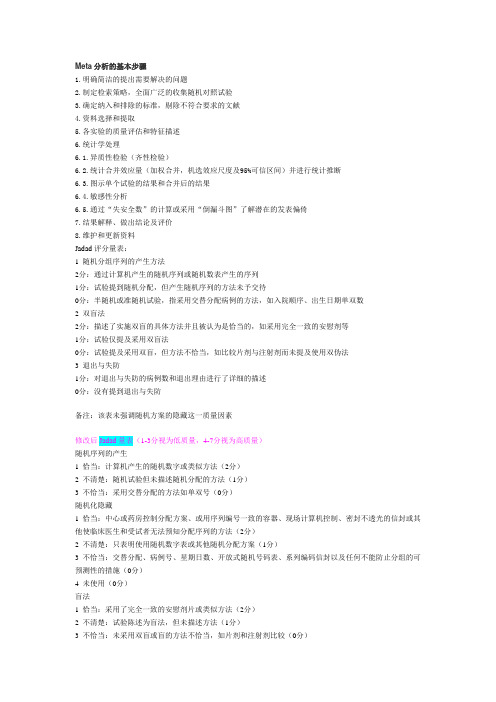

Meta分析的基本步骤1.明确简洁的提出需要解决的问题2.制定检索策略,全面广泛的收集随机对照试验3.确定纳入和排除的标准,剔除不符合要求的文献4.资料选择和提取5.各实验的质量评估和特征描述6.统计学处理6.1.异质性检验(齐性检验)6.2.统计合并效应量(加权合并,机选效应尺度及95%可信区间)并进行统计推断6.3.图示单个试验的结果和合并后的结果6.4.敏感性分析6.5.通过“失安全数”的计算或采用“倒漏斗图”了解潜在的发表偏倚7.结果解释、做出结论及评价8.维护和更新资料Jadad评分量表:1 随机分组序列的产生方法2分:通过计算机产生的随机序列或随机数表产生的序列1分:试验提到随机分配,但产生随机序列的方法未予交待0分:半随机或准随机试验,指采用交替分配病例的方法,如入院顺序、出生日期单双数2 双盲法2分:描述了实施双盲的具体方法并且被认为是恰当的,如采用完全一致的安慰剂等1分:试验仅提及采用双盲法0分:试验提及采用双盲,但方法不恰当,如比较片剂与注射剂而未提及使用双伪法3 退出与失防1分:对退出与失防的病例数和退出理由进行了详细的描述0分:没有提到退出与失防备注:该表未强调随机方案的隐藏这一质量因素修改后Jadad量表(1-3分视为低质量,4-7分视为高质量)随机序列的产生1 恰当:计算机产生的随机数字或类似方法(2分)2 不清楚:随机试验但未描述随机分配的方法(1分)3 不恰当:采用交替分配的方法如单双号(0分)随机化隐藏1 恰当:中心或药房控制分配方案、或用序列编号一致的容器、现场计算机控制、密封不透光的信封或其他使临床医生和受试者无法预知分配序列的方法(2分)2 不清楚:只表明使用随机数字表或其他随机分配方案(1分)3 不恰当:交替分配、病例号、星期日数、开放式随机号码表、系列编码信封以及任何不能防止分组的可预测性的措施(0分)4 未使用(0分)盲法1 恰当:采用了完全一致的安慰剂片或类似方法(2分)2 不清楚:试验陈述为盲法,但未描述方法(1分)3 不恰当:未采用双盲或盲的方法不恰当,如片剂和注射剂比较(0分)撤出与退出1 描述了撤出或退出的数目和理由(1分)2 未描述撤出或退出的数目或理由(0分)Meta分析的计算的主要步骤:1.计算每个研究的效应量及方差2.计算每个研究效应量的权重3.计算合并效应量4.异质性检验5.合并效应量的可信区间6.合并效应量的检验1.单个研究的统计量根据资料类型选择单个研究的统计量d1(1)分类变量可选择的统计量比值比,OR相对危险度,RR率差,RD(2)数量变量可选择加权均属差(WMD)或标准化均数差(SMD)用于描述单个研究的实验结果,其结果解释与常规统计描述指标相同。

《2024年Meta分析系列之二_Meta分析的软件》范文

《Meta分析系列之二_Meta分析的软件》篇一Meta分析系列之二_Meta分析的软件Meta分析系列之二:Meta分析的软件一、引言Meta分析作为一种综合性的文献研究方法,已经在多个学科领域中得到了广泛的应用。

然而,Meta分析的过程涉及到大量的数据整理、统计分析等工作,这就需要借助专业的软件来辅助完成。

本文将重点介绍Meta分析的软件,以及如何利用这些软件提高Meta分析的质量。

二、Meta分析软件概述1. 常用Meta分析软件目前,市面上有很多用于Meta分析的软件,如Comprehensive Meta Analysis (CMA)、Review Manager (RevMan)、Stata等。

这些软件在功能、操作等方面有所不同,但都能有效地支持Meta分析的过程。

2. 软件功能特点(1) Comprehensive Meta Analysis (CMA):CMA是一款功能强大的Meta分析软件,支持多种统计模型,如固定效应模型、随机效应模型等。

同时,CMA还提供了丰富的图形工具,有助于研究者直观地了解分析结果。

(2) Review Manager (RevMan):RevMan是Cochrane协作网推出的专门用于系统评价和Meta分析的软件。

RevMan操作简便,界面友好,适合初学者使用。

(3) Stata:Stata是一款强大的统计分析软件,也支持Meta分析。

Stata的语法较为复杂,但功能丰富,适合有一定统计学基础的研究者使用。

三、软件使用方法及注意事项1. 选择合适的软件在选择Meta分析软件时,应根据自己的需求、经验水平以及软件的功能特点进行综合考虑。

对于初学者,建议选择操作简便、界面友好的软件;对于有一定统计学基础的研究者,可以选择功能更强大、灵活性更高的软件。

2. 严格按照软件操作指南进行操作在使用Meta分析软件时,应严格按照软件操作指南进行操作,避免因操作不当导致分析结果出现偏差。

meta分析的写作思路

收集整理丁香园的关于meta分析的写作!!一、新手meta分析上路(一):选题现在读研的很多学生甚至临床上的医生,迫于某些压力或者是个人兴趣(找虐型),开始学习meta分析,理想的发篇SCI文章,不济的也当学个技术,技多不压身。

为什么会找meta做为切入点呢,江湖传言此乃发文神器,某大仙一年发十篇meta的也不是少见。

感觉它不用做实验,窝在家一股脑的看文献,整理整理数据,也不耗钱,真是一本万利的生意,尤其适合苦逼的临床医生。

也不用养老鼠闻味道,不用陪细胞过夜,不用天天WB,PCR,转染,过表达,etal。

长期接触这些生物试剂能活下来的都是命大。

所以聪明的中国人开始走上了meta这道“不规路”,早上发,中午发,天天发,发。

好了,扯了那么多没用的,入正题,想发一篇文章,首先是要选好一个题目。

我可以负责任的告诉大家,你今天选题的高度决定了你日后发文的高度。

所以磨刀不误砍柴工,好好选题,良好的开端是成功的一半(好一碗鸡汤)。

那么问题来了,怎么选题呢结合我个人的经验,我认为良好的优质的题目有以下几个特点:1.是临床现有的争议点,大家对此还不是很统一,指南也模棱两可。

2.对现有的操作的一种challenge,如果你的meta能改变某种临床行为,那你屌了。

3.之前已经有篇meta了,但后来因为加入新的articles,挑战了之前的结果,能引起一定的讨论。

当然,这些题目都很难找,因为不仅国人“沉迷”meta,老外也不甘落后的。

现阶段大部分multi-centersRCTs都是国外研究机构发表的,他们一般在进行临床研究的同时,已经将其meta分析的文章也顺带做了,RCTs发表同时将meta 分析也扔出去。

所以好题目都被他们抢了,我们只能捡些他们不要的(这是一个忧伤的故事)。

不管如何,我们还是要掌握一些选题的技巧和原则,指不定那一天就让我们碰上了一个好题目也不一定(人如果没有梦想那跟咸鱼有什么区别,星爷如是说)。

我有几个渠道和方式来选择题目(主要指干预方面的meta):1.看本专业Top临床期刊最新的articles和review,如我是神经科的,我就去多逛逛Neurology,Stroke,Movementdisorder等专科杂志最新的RCTs和综述,尤其是综述里面治疗的那一部分。

meta分析的写作教材

16

3. 机理

客观的回答为什么治疗是有效的

• 药理学、药代学研究情况 e.g.中药复方分离出单个成分:川芎活血化瘀,测血小板聚 集性、血液流变学

• 基础研究试验 • 临床研究报道

17

4.必要性

•收集现有研究,列举现有研究是否已解决此临床问题 •是否结论统一 •如已有统一结论,有无系统评价的全面分析 •如有SR/META是否准确回答问题,有无新的证据出现 •研究目的:对某一药物的疗效和安全性进行评估,次要目的 可以为应用范围和使用方法

1.一般信息

•介绍疾病:关注的临床问题 定义(要求1-2句话) •病因学:关于疾病的临床病学资料 •病理生理学 •疾病的自然发展史 •疾病的危害:对经济、工作、家庭的损失,运用数据说明治 疗此类疾病的重要性

15

2.疾病的当前管理(治疗措施)

第一种写法: 全面的治疗方法(心脏组) 第二种写法: 仅仅围绕系统评价所涉及的治疗措施(急性上呼吸道感染组) e.g.硝酸酯类药物治疗不稳定性心绞痛

Data collection and analysis:

e.g. Two review authors independently assessed the identified studies to determine eligibility for inclusion.

23

Main results:

4

PRISMA声明包括7个方面,27个条目和一个四阶段的流程图

5

6

7

文献筛选4阶段流程图

8

9

10

COCHRANE COLLABORATION(CC)组成

1.决策机构——指导委员会Steering Group

如何撰写meta分析论文

数据分析

对提取的数据进行统计分析,包括描 述性统计和推断性统计。

论文撰写

按照学术论文的格式和规范,撰写 meta分析论文,包括引言、方法、 结果、讨论和结论等部分。

02

选题与文献筛选

选题原则与策略

针对性

选择与特定主题或问题相关的研究,确保 meta分析的针对性和目的性。

重要性

选择具有重要性和现实意义的研究主题,能够为特 定领域或实践提供有价值的见解。

创新性

关注新的研究领域或未被充分探讨的问题, 提出新的观点或解释,推动知识进步。

文献筛选标准与方法

文献类型

确定所纳入文献的类型,如随机对照试验、观察性研究等,以确保研 究的可靠性和有效性。

研究质量

采用合适的质量评价工具对所纳入文献的质量进行评价,如Jadad评 分量表等。

研究结果

关注文献的研究结果和结论,确保所纳入文献与研究目的和问题相关 。

格式要求

附录的格式通常需要符合期刊或出版机构的 规定,如字体、字号、行距、页边距等,同 时要注意保护个人隐私和信息安全。

参考文献与附录报告

参考文献报告

在论文中需要有一个专门的部分对参考文献进行报告,包括参考文献的来源、筛选标准 、数量和质量等,以证明研究的可靠性和可重复性。

附录报告

对于一些较为复杂或重要的数据和信息,可以通过附录进行报告,以便读者更好地理解 和评估研究结果。同时,附录也可以作为论文的补充材料,提供更多的信息和证据支持

结论与建议报告

报告撰写

将结论总结、建议提出和实施方案设计等内容整理成一份完整的报 告,确保内容的逻辑性和连贯性。

报告审核与修改

邀请同行专家对报告进行审核和修改,提高报告的质量和水平。

meta分析 论文

meta分析论文以下是一篇关于meta分析的论文的例子:标题:A Meta-analysis of the Efficacy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Depression in Adolescents摘要:该研究旨在通过meta分析评估认知行为疗法(CBT)在青少年抑郁症治疗中的疗效。

我们检索了包括英文和中文在内的巴基斯坦、印度和中国等地的相关数据库,并共纳入了15项研究。

结果显示,CBT在青少年抑郁症治疗中具有显著的疗效,具体表现为抑郁指标的显著下降,自我报告的心理健康水平的提高,以及生活质量的改善。

进一步的亚组分析发现,CBT的疗效在不同性别、年龄和治疗形式的青少年之间没有显著差异。

然而,随机对照试验的质量与CBT的疗效之间存在一定程度的关联,高质量的研究显示出更好的治疗效果。

本研究的结果强调了CBT在青少年抑郁症治疗中的重要性,并提供了进一步研究的建议。

关键词:meta分析、认知行为疗法、青少年、抑郁症、疗效引言:青少年抑郁症是一种常见的精神疾病,对患者的生活质量和学业成就产生负面影响。

虽然有多种治疗方法可供选择,但研究结果不一致,缺乏一致的证据支持。

因此,本研究旨在通过meta分析综合评估CBT在青少年抑郁症治疗中的疗效。

方法:我们检索了PubMed、PsycINFO、Cochrane图书馆和中国知网等数据库,以纳入符合包括青少年、抑郁症和认知行为疗法等关键词的研究。

最终,共纳入了15项符合纳入标准的研究。

结果:该meta分析显示,CBT对青少年抑郁症的治疗具有显著疗效(汇总效应大小为0.65,95%置信区间为0.45-0.85),表现为抑郁指标的显著下降,自我报告的心理健康水平的提高,以及生活质量的改善。

亚组分析结果显示,CBT的疗效在不同性别、年龄和治疗形式的青少年之间没有显著差异(P>0.05)。

然而,随机对照试验的质量与CBT的疗效存在正相关(P<0.05),高质量的研究显示出更好的治疗效果。

META分析文字版

AbstractBackground: Whether depression causes increased risk of the development of breast cancer has long been debated. We conducted an updated meta-analysis of cohort studies to assess the association between depression and risk of breast cancer. Materials and Methods: Relevant literature was searched from Medline, Embase, Web of Science (up to April 2014) as well as manual searches of reference lists of selected publications. Cohort studies on the association between depression and breast cancer were included. Data abstraction and quality assessment were conducted independently by two authors. Random-effect model was used to compute the pooled risk estimate. Visual inspection of a funnel plot, Begg rank correlation test and Egger linear regression test were used to evaluate the publication bias. Results: We identified eleven cohort studies (182,241 participants, 2,353 cases) with a follow-up duration ranging from 5 to 38 years. The pooled adjusted RR was 1.13(95% CI: 0.94 to 1.36; I2=67.2%, p=0.001). The association between the risk of breast cancer and depression was consistent across subgroups. Visual inspection of funnel plot and Begg’s and Egger’s tests indicated no evidence of publication bias. Regarding limitations, a one-time assessment of depression with no measure of duration weakens the test of hypothesis. In addition, 8 different scales were used for the measurementof depression, potentially adding to the multiple conceptual problems concerned with the definition of depression. Conclusions: Available epidemiological evidence is insufficient to support a positive association between depression and breast cancer.IntroductionDepression is highly prevalent in the general population, and it is estimated that 5.8% of men and 9.5% of women will experience a depressive episode in a 12-month period. The lifetime incidence of depression has been estimated at more than 16% in the general population (World Health Organization, 2001; Kessler et al., 2003; World Health Organization, 2008). Breast cancer is by far the most commom cancer in women (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2008), the global burden of breast cancer measured by incidence and mortality is substantial and on the increase (Benson et al., 2012). There are an estimated 1.5 million cases diagnosed annually and almost 0.5 million died from this disease, representing 14% of female cancer deaths in the worldwide (Jemal et al., 2011; Benson et al., 2012). Many factors have been shown to be associated with the occurrence of breast cancer, such as having a first degree relative with breast cancer, bearing the first child at a late age, alcohol consumption and long term use of menopausal estrogen replacement therapy (Kampert et al., 1988; Gail et al., 1989;Slattery et al., 1993). However, it has long been debated that whether depression is an increased risk of the development of breast cancer. Depression may affect the endocrine and immune function (Kowal et al., 1955; Miller et al., 1993), which may have influence on cancer initiation and progression, including breast cancer. Importantly, women themselves widely believed that depression was a risk factor in the development of their breast cancer (Mitchell et al., 1995). However epidemiology evidences on the association between depression and breast cancer incidence are mixed and inconclusive.A great many of studies have assessed the association between depression and subsequent risks of breast cancer. A previous meta-analysis (Oerlemans et al., 2007) focusing on breast cancer pooled results from 7 prospective studies published before 2003 as a secondary analysis and reported a pooled relative risk estimated of 1.59 (95% confidence intervals, 0.74-3.44). Since then some cohort studies have been published, which provide stronger evidence of the association between depression and breast cancer. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis of cohort studies to describe the association between depression and risk of breast cancer.Materials and MethodsSearch strategyWe conducted a systematic literature search (up toApril 2014) of Medline, Embase, Web of Science for studies describing the association between depression and breast cancer. We used the following terms “depression”or “depressive disorder” or “major depressive disorder”or “depressive symptoms” and “breast cancer” or “breast carcinoma” combined with “cohort study” or “prospective study” or “follow-up study” or “longitudinal study”.In addition, studies from reference lists of all relevant publications and reviews were searched to identify potential pertinent studies.Study selectionStudies meeting the following criteria would be included in this meta-analysis: i) the study was a cohort design (prospective cohort or historical cohort); ii) the exposure was depression symptoms or depressive disorder which were measured by self-reported scales or structured clinical interview or clinician diagnosis; iii) the endpoint was diagnosis or report of breast cancer, all participants were free of any subtypes of cancer at the beginning of the study; iv) the study reported the RR or hazard risk(HR) with corresponding 95% CIs for the association between depression and breast cancer; and v) study was publishedin English. If multiple independent published reports were from a same cohort, only the latest one was included. Study selection was independently performed by two authors (S.H.L and D.X.X) and conflicts were resolved through discussion with the third reviewer (L.Z.X).Data extractionWe extracted the following information fromeach retrieved article: name of the first author, yearof publication, study location, characteristics of study population at baseline, duration of follow-ups, sample size, numbers of cases, depression and breast cancer measurements, adjusted effect estimate and corresponding 95% CIs, and variables used in multivariable analysis. Quality assessment was performed according to the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale for cohort studies (Wells et al., 2006) by two investigators (S.H.L and D.X.X). This scale allocates a maximum of nine points for quality of selection (0-4 points), comparability (0-2 points), exposure and outcome of study participants (0-3 points). The two authors discussed the implementationof this assessment tool and agreed on a method of implementation before their independent assessments ofstudies. The level of agreement between the two reviewers was calculated by another investigator (L.Z.X).Statistical analysisThe RRs were used as the common measure of association across studies, and the hazard ratios (HRs) were considered equivalent to RRs. Forest plot was produced to visually assess the RRs and corresponding 95% CIs across studies. Statistical heterogeneity across studies was estimated by I2 statistic. I2 values of 25%, 50%, 75% are regarded as cut-off points for low, moderate and 2003). The RRs were pooled using the fixed-effect modelif no or low heterogeneity was detected, or random-effect model otherwise (DerSimonian et al., 1986). In sensitivity analyses, we conducted leave-one-out analysis (Wallaceet al., 2009) for each study to examine the magnitude of influence of each study on pooled risk estimates. Subgroup analyses for study location, number of participants and cases, follow-up time, exposure measurement, smokingor alcohol drinking and study quality were conductedto examine the robustness of the primary results. Visual inspection of a funnel plot and Begg rank correlation test, Egger linear regression test (Begg et al., 1994;Egger et al., 1997) were used to evaluate the potential publication bias. The Duval and Tweedie nonparametric trim-and-fill procedure(Duval et al., 2000) was used to further assess the possible effect of publication bias. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA). All tests were two sided with a significance level of 0.05.ResultsEligible studiesTotally 1705 articles were identified from the Medline, Embase, Web of Science. After the first round of screening based on titles and abstracts with aforementioned criteria, 1682 articles were excluded. Examining the articles remained in more details, nine articles (Hahn et al.,1988; Jacobs et al., 2000; Dalton et al., 2002; Nyklicek et al., 2003; Goldacre et al., 2007; Gross et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2011; Lemogne et al., 2013) met the inclusion criteria. The detailed reasons for exclusion were shown in Figure 1. Besides, one article (Schuurman et al., 2001) was found from the previous meta-analysis (Oerlemans et al., 2007) and one (Knekt et al., 1996) was identified by searching the reference lists. In total, elevenarticles were included in this meta-analysis.Study characteristicsCharacteristics of the eleven articles were showedin Table 1. These studies were published between 1988 and 2013. The sample size of studies varied from 1,533to 57,320, with a total of 182,241, and the number of breast cancer cases ranged from 20 to 728, with a totalof 2,353. With regard to study location, three studies were conducted in the USA, two studies in Taiwan, twoin Netherlands, one in France, one in the UK, one in Denmark, and one in Finland. In four of eleven studies, depression was measured by self-reported scales which were the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory(MMPI), and Ediburgh Depression Scale (EDS). Two studies used the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) and one used International Classification of Health Problems in Primary Care (ICHPPC) to define depression. The other four studies defined depression according to the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification or International Classification of Disease,Eighth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM or ICD-8-CM). The outcome of studies was ascertained by medical records or death certificates in seven studies, by self-report in two studies, and by combining self-report with medical records in the rest two studies. The eleven articles were assessed and were of moderate quality with a mean score of 6.9 (ranging from 6-8).All the included studies provided adjusted RRs. The major confounding factors adjusted included age, family history of breast cancer, cigarette smoking, alcohol intake, obesity, social status, and complications.Association between depression and risk of breast cancer The association between depression and breastcancer risk was shown in Figure 2. The majority of allthe eleven studies indicated a positive trend between depression and breast cancer (RR>1), but only two of them were statistically significant. At the same time one article (Nyklicek et al., 2003) reported that depression could reduce the risk of breast cancer in middle-aged women. With a moderate to high heterogeneity (I2=67.2%, p=0.001), the pooled analysis from random-effect model revealed that depression was not associated with breastcancer risk (RR,1.13; 95% CI 0.94 to 1.36).Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analysesTable 2 showed the results of subgroup analyses. We conducted subgroup analyses by study characteristics, such as study locations, number of study of participants and cases, duration of follow-up, exposure levels and study quality, while the results were not statistically significant. In addition, we conducted subgroup analyses according to the results whether or not adjusted by alcohol consumption or smoking, and neither alcohol consumption nor smoking altered the association.one showed that Jacobs et al’s study (Jacobs et al., 2000) and Goldacre et al’s study (Go ldacre et al., 2007) imposed the largest influence on the results. The pooled RRs were 1.24 (95%CI: 0.95-1.61) and 1.06 (95%CI 0.92-1.22) after excluding the two studies, respectively.Publication biasVisual inspection of funnel plot revealed some asymmetry (see supplementary Figure 1A). However,the Begg rank correlation test, Egger linear regressiontest provide no evidence of substantial publication bias (Begg’s test Z=1.25, p=0.213; Egger’s test t=-0.39,p=0.709). A sensitivity analysis using the trim-and-fill method was performed with 3 imputed studies, which produced a symmetrical funnel plot (see supplementary Figure 1B). The pooled RR incorporating the three hypothetical studies was smaller than the original results, but it still did not reach the statistically significant (RR, 1.04; 95% CI, 0.84-1.27).DiscussionThe study results were derived from eleven cohort studies which reported association between depression and risk of breast cancer. In all, our meta-analysis involved 2,353 cases of breast cancer and 182,241 participants.No significant association between depression and risk of breast cancer was found (RR, 1.13; 95%CI, 0.94 to 1.36) after adjustment for potential confounders. Furthermore, the association between depression and breast cancer persisted across subgroup analyses.Taking into account the impact of ethnic and geographic on the incidence of breast cancer, subgroup analyses by locations (European countries vs. USA vs. Taiwan) were conducted but no significant difference was found. As we know, different levels of exposure mayhave different effects on the study outcome. Therefore,we conducted subgroup analysis by exposure levels (depression symptoms vs. depressive disorder) which showed no statistically significant association between depression and breast cancer risk. Given that a long period was required to develop a detective tumor, subgroup analysis by the duration of follow-up were conductedand the results were not statistically significant as well, though the RR was elevated in the cohorts of more than10 years of follow-up. There were studies identifiedthat depression individuals may engage more unhealthy behaviors that predispose them to further onset of cancer, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, lack of physical activity (Son et al., 1997; Strine et al., 2008). But the subgroup analyses according to the results that whetheror not adjusted by smoking and alcohol consumption didnot find significant association.A meta-analysis conducted by Marjolein EJ Oerlemanset al. (2007) in 2007 investigated the relationship between depression and overall cancer risk. The previous metaanalysis also identified association between depressionand breast cancer as a secondary analysis. The secondaryanalysis included seven prospective studies which involved 111756 participants and 1601 cases and reported no significant association (RR, 1.59; 95%CI, 0.74-3.44). Our meta-analysis, with four more cohort (Goldacre et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2011; Liang et al., 2011; Lemogne et al., 2013) studies and one update study (Gross et al., 2010), demonstrates no evidence of association between depression and breast cancer, which is consistent with the previous meta-analysis. However, we noticed that the previous review found depression might be a risk factor for breast cancer (RR, 2.5; 95%CI, 1.06-5.91) if study population were followed more than 10 years. In our review, this association in subgroup analysis by follow-up more than 10 years was not proved. To our knowledge, the larger size of participants, the stronger evidence of the study. The combined results of our meta-analyses are more credible with relatively narrow confidence intervals. Considering the limited number of the included studiesof the previous meta-analysis, we can not conclude that there is significant association between depression and breast cancer.Experimental animal studies, human studies andclinical evidence suggest that depression may put an influence on the development of breast cancer through several mechanisms, such as impairing immune function, causing an aberrant activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary- adrenal axis and inhibiting DNA repairmechanisms (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2002; Reiche et al., 2005; Soygur et al., 2007). However, epidemiological research evidences did not indicate the presence of sucha relationship between depression and breast cancer. The and epidemiological studies may be explained by two reasons. On the one hand, the strength of experimental evidence may be compromised due to species differences, inconsistent of laboratory conditions and the measurement of biomarker. Some experiments could not be replicated by different investigators. On the other hand, epidemiological studies may have some methodological flaws, such as insufficient follow-up duration, different definitions and measurement of exposure, the size of sample and so on. Overall, evidence supporting that depression increases the risk of breast cancer are insufficient.There are two strengths in our meta-analysis. Firstly,all studies in the present analyses were cohort studies,which minimized the selection and recall bias. Although our review is an updated meta-analysis, it provides robust and credible conclusion for the association between depression and breast cancer. Secondly, most of studies included in this meta-analysis had average follow-up times more than 10 years. Sufficiently long follow-up duration is necessary because most cancers have a latent period of a few years or even decades (Spratt et al., 1996; Friberget al., 1997). Thus, our results based on long follow-up duration studies could indicate that the depression might not increase the risk of breast cancer.Limitations: A few limitations of our meta-analysis should be acknowledged. Firstly, depression was only measured on the basis of a single baseline measure, which was clearly not identical to depression diagnosis. During the follow-up duration, the exposure intensity of subjects would change. Penninx et al (1998) (Penninx et al., 1998) proved that repeated assessment of depressive symptoms yielded positive association with later developmentof some cancers, in contrast to single measurements. Therefore, a one-time assessment of depression withno measure of duration weakens the test of hypothesis.Secondly, no less than 8 different scales were used for the measurement of depression in the 11 original studies. It may add to the multiple conceptual problems concerned with the definition of depression (Buntinx et al., 2004), which could increase the heterogeneity in our metaanalyses. In conclusion, available epidemiological evidencesare insufficient to support association between depression and the development of breast cancer. Given the high prevalence and morbidity of depression and breast cancer, the results of this meta-analysis not only can act as the clue of the etiology, but can provide the evidence to women who believed that depression could increase the risk of breast cancer.Acknowledgements。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Meta分析写作思路及流程

Meta分析对大家都不陌生,它是指当系统评价用定量合成方法对资料进行统计学处理时称为Meta分析,国内有译为“荟萃分析”或“汇总分析”。

在谈及主题之前,首先对本人进行简单的介绍:在读硕士研究生,从2006年12月开始触及Meta分析,即在导师的指点下,利用闲余时间做Meta分析相关的研究,目前我已经以第1作者发表Meta分析研究3篇(其中SCI收录1篇,中文核心期刊1篇,全国会议论文收录1篇),中文核心期刊非第1作者Meta分析发表1篇、已收稿1篇。

总结以往经验,现把自己的研究思路介绍給大家,希望对相关研究者能有所帮助。

一、选题

“选题”是Meta分析首先要面临的问题,做Meta分析之前的第一个问题就是要找到题目,做什么?那么“选题”也是最难的部分,选题的好坏直接决定着你研究的成与败,好的题目会使我们非常轻松的做完整个研究,并得到满意的结果;然而,不好的题目可能导致无法完成你的研究,不得不中途放弃,因此Meta分析的选题非常重要,是大家首先必须解决的问题。

那么我对怎么样选题,总结了以下几点

1.熟练运用中国生物医学数据库(CBM)和PubMed数据库,通过检索及阅读相关文献达到一个目的——对你要做的主题相关内容非常熟悉,包括研究现状、相关研究文献数量、中文及外文文献发表情况等。

2.选题要新颖、有创新性(也是文章发表的长处);举个例子:我的英文Meta分析创新性就是我检索了中文数据库(相关已发表Meta分析2篇均为英文,均未检索中文数据库),且我仅在中国人群中进行研究,这样降低了不同遗传背景的影响,使研究结果更具体、更有可信性。

3.所选主题目前要存在争议,已经有定论的问题不易做Meta分析。

4.所选主题的相关研究不易过少。

5.最好选题为当前热点问题。

6.注意合并指标的选择,比如目前Meta分析较成熟的是对分类资料(OR或RR值的合并),那么对于定量资料就不是很成熟。

二、检索策略

当题目选好以后,那么下一个问题就是要列出你的检索策略,不同的检索策略所得到的文献数量是不同的,那么我们的目的就是要找到即与我们研究相符合又能检索出比较多文献的这种检索策略,建议大家参考《医学信息检索与利用》等相关书籍,或向图书馆检索工作人员请教。

三、收集资料

如果说“选题”是Meta分析最难的部分,那么“收集资料”就是Meta分析最繁杂的部分。

文献的收集过程可能是非常的漫长,原因可能有2个:①时间,由于事情繁多,无闲暇时间收集资料;②全文,检索结果已经出来,但大部分文献全文无法获得。

第1个问题大家自己解决,第2个问题的解决方法有:

①进图书馆进行手工查询;②通过朋友、同学进行求助;③通过相关网站进行网上求助,如零点花园等都是非常好的文献求助工具。

由于文献较多,内容复杂,那么我们就很有必要对每篇文献进行资料提取,并且对其进行编号以待整理评价。

一般的文献资料提取表主要内容包括文章名称、作者、刊登杂志、研究目的、研究类型、基因检测方法、研究地点、研究对象、疾病诊断标准、统计方法与质量评估、结果、结论、文章评阅时间和文章评阅人等,根据不同研究可以自己变动,文献资料提取表编号可作为文件名。

这样,资料提取表就是我们的第一手资料,避免了我们每次评价都必须翻阅文章全文的麻烦。

四、文献评阅

文献收集后,就是文献的评阅过程。

Meta分析的文献评阅一般是2人根据纳入和排除标准分别对文献进行评阅,当出现不一致时,再请第3人评阅。

文献的评阅也可以参考相关标准对文献进行分级,具体请参考《循证医学》等相关书籍。

五、数据录入、分析及结果

当确定纳入文献之后,我们就可以把纳入文献数据录入相关软件进行分析,那么目前做Meta分析常用软件有好3种:SAS,Stata,RevMan。

由于Stata的作图效果最好,RevMan的操作比较简单,所以建议大家联合应用RevMan(局限为不能做发表偏倚回归图)和Stata。

下图为RevMan和Stata作图:

RevMan森林图(beautiful)

Stata漏斗图(beautiful)

Stata发表偏倚回归图(beautiful)

RevMan漏斗图(beautiful?)

六、论文写作

至此,Meta分析前期过程基本做完,接下来的就是要把我们的研究写成论文的形式发表出去,那么写作过程在此不做介绍,有兴趣者可以参考本人所总结的“SCI撰写和投稿经验”,见零点论文写作投稿与管理版(/bbs/thread-8723790-1-1.html)

祝大家如心所愿!。