计算材料学-14-1

Ch14 - Composites

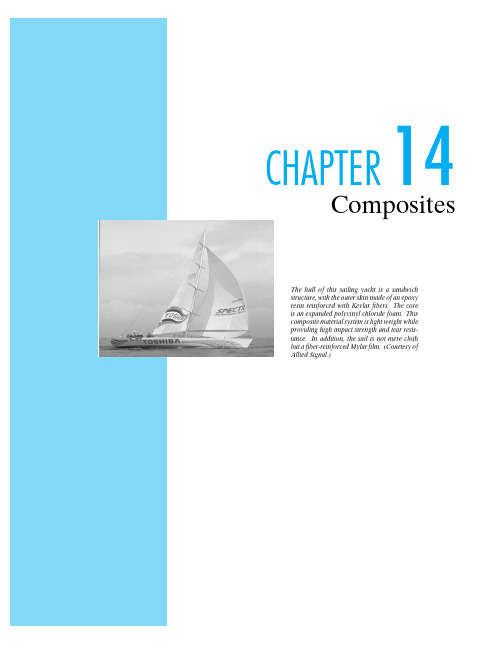

CHAPTER14CompositesThe hull of this sailing yacht is a sandwich structure,with the outer skin made of an epoxy resin reinforced with Kevlar fibers.The core is an expanded polyvinyl chloride foam.This composite material system is light weight while providing high impact strength and tear resis-tance.In addition,the sail is not mere cloth but a fiber-reinforced Mylar film.(Courtesy of Allied Signal.)Figure14-1Glassfibers to be used for reinforcement in afiber-glass composite.(Courtesy of Owens-Corning FiberglasCorporation)Figure14-2The glassfiber reinforcement in afiberglass composite is clearly seen in a scanning electron microscope image of a fracturesurface.(Courtesy of Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corporation)(a)(b)(c)Figure14-3Three commonfiber configurations for composite reinforcement are(a)contin-uousfibers,(b)discrete(or chopped)fibers, and(c)woven fabric,which is used to make a laminated structure.HN NnC COO((Very fine, wool typeFine wires (drawn diameter = 25 microns)also coarse whiskersFigure14-4Relative cross-sectional areas and shapes of a wide variety of re-inforcingfibers.(After L.J.Broutman and R.H.Krock,Eds.,Modern Composite Materials,Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.,Inc.,Reading,Mass.,1967,Chapter14.)Figure14-6Anisotropic macrostructure of wood.(Courtesy of Zimmer Corporation)Scanning electron micoscope image of the aggregate composite com-posed of ceramic(hydroxyapatite plus tricalcium phosphate)gran-ules in a polymeric(collagen)matrix.The image shows collagen as a darker gray.(From J.P.McIntyre,J.F.Shackelford,M.W.Chap-man,and R.R.Pool,Bull.Amer.Ceram.Soc.701499(1991))SandGravelR e l a t i v e a b u n d a n c e (a r b i t a r y s c a l e )0.1110100Sieve openings (mm)(see Table 14.5)Figure 14-7Typical particle size distribution for aggregate in con-crete.(Note the logarithmic scale for particle sizes screened through the sieve openings.)Figure14-8Filling the volume of concrete with aggregate is aided by a wide particle size dis-tribution.The smaller particlesfill spaces be-tween larger ones.This view is,of course,a two-dimensional schematic.Figure 14-9Three idealized composite ge-ometries:(a)a direction parallel to con-tinuous fibers in a matrix,(b)a direc-tion perpendicular to continuous fibers in a matrix,and (c)a direction rela-tive to a uniformly dispersed aggregatecomposite.(c)(E-glass) fiber modulus = 72.4 × 103 MPaComposite (70 vol % fibers)modulus = 52.8 × 103 MPa(Epoxy) matrix modulus = 6.9 × 103 MPa15001000500000.010.02Figure 14-11Simple stress–strain plots for a composite and its fiber and ma-trix components.The slope of each plot gives the modulus of elasticity.The composite modulus is given by Equation 14.7.Figure14-12Uniaxial loading of a composite perpendicular to the fiber reinforcement can be simplyrepresented by this slab.10050000.51.0E c (103 M P a )Figure 14-13The composite modulus,E c ,is a weighted average of the moduli of its components (E m =matrix modulus and E f =fiber modulus).For the isostrain case of parallel loading (Equation 14.7),the fibers make a greater contribution to E c than for isostress (perpendicular)loading (Equation 14.19).The plot is for the specific case of E-glass-reinforced epoxy (see Figure 14–11).Figure14-14Uniaxial stressing of an isotropic aggregate composite.E hE cE l0.51.0Exponent in Equation 14.21Figure 14-15The dependence of composite modulus,E c ,on the volume fraction of a high-modulus phase,v h ,for an aggre-gate composite is generally between the extremes of isostrain and isostress condi-tions.Two simple examples are given byEquation 14.21for n =0and 12.Decreas-ing n from a +1to −1represents a trend from a relatively low-modulus aggregate in a relatively high-modulus matrix to the reverse case of a high-modulus aggregate in a low-modulus matrix.12+12–+1–10.81.01.21.4B /An Ӎ 0Therefore,Figure14-16The utility of a reinforcingphase in this polymer–matrix compos-ite depends on the strength of the inter-facial bond between the reinforcementand the matrix.These scanning elec-tron micrographs contrast(a)poor bond-ing with(b)a well-bonded interface.Inmetal–matrix composites,high interfa-cial strength is also desirable to ensurehigh overall composite strength.(Cour-tesy of Owens-Corning Fiberglas Cor-poration)(a)(b)(b)Figure 14-17(a)Plot of the tensile stress along a “short”fiber in which the build-up of stress near the fiber ends never exceeds the criti-cal stress associated with fiber failure.(b)A similar plot for the case of a “long”fiber in which the stress in the middle of the fiber reaches the critical value.(a)(b)(c)Figure14-18For ceramic–matrix composites,low interfacial strength is desirable(in contrast to the case for ductile–matrix composites,such as in Figure14–16).We see that(a)a matrix crack approaching afiber is(b)deflected along thefiber–matrix interface.For the overall composite(c),the increased crack path length due tofiber pull-out significantly improves fracture toughness.(Two tougheningmechanisms for unreinforced ceramics are illustrated in Figure8–7.)K I C (M P a Ί m )302010Figure 14-19The fracture toughness of these structural ce-ramics is substantially increased by the use of a rein-forcing phase.(Note the toughening mechanism illus-trated in Figure 14–18.)S p e c i f i c s t r e n g t h (m m )l a r /e p o x y120100806040200Figure 14-20A bar graph plot of the data of Table 14.13illustrates the sub-stantial increase in specific strength possible with composites.Continuous Pultrusion Continuous strand–roving or other forms of reinforcement–is impregnated in a resin bath and drawn through a die which sets the shape of the stock and controls the resin content. Final cure is effected in an oven through which the stock is drawn by a suitable pulling device.resin and poured into open molds. Cure is at roomtemperature. A post-cure of 30 minutes at 200 F isnormal.Open mold processes(a)Figure14-21Summary of the diverse methods of processingfiberglass prod-ucts:(a)open-mold processes.Preforming methodsClosed mold processes(b)(c)Directed FiberRoving is cut into 1 to 2 inch lengths ofchopped strand which are blownthrough a flexible hose onto a rotatingpreform screen. Suction holds them inplace while a binder is sprayed on thepreform and cured in an oven. Theoperator controls both deposition ofchopped strands and binder.Plenum ChamberRoving is fed into a cutter on top ofplenum chamber. Chopped strands aredirected onto a spinning fiberdistributor to separate choppedstrands and distribute strandsuniformly in plenum chamber. Fallingstrands are sucked onto preformscreen. Resinous binder is sprayed on.Preform is positioned in a curing oven.New screen is indexed in plenumchamber for repeat cycle.Water SlurryChopped strands are pre-impregnatedwith pigmented polyester resin andblended with cellulosic fiber in a waterslurry. Water is exhausted through acontoured, perforated screen and glassfibers and cellulosic material aredeposited on the surface. The wetpreform is transferred to an ovenwhere hot air is sucked through thepreform. When dry, the preform issufficiently strong to be handled andmolded.Premix/Molding CompoundPrior to molding, glass reinforcement, usuallychopped spun roving, is thoroughly mixed with resin,pigment, filler, and catalyst. The premixed materialcan be extruded into a rope-like form for easyhandling or may be used in bulk form.The premix is formed into accurately weighed chargesand placed in the mold cavity under heat andpressure. Amount of pressure varies from 100 to 1500psi. Length of cycle depends on cure temperature,resin, and wall thickness. Cure temperatures rangefrom 225 F to 300 F. Time varies from 30 seconds to 5minutes.Injection MoldingFor use with thermoplasticmaterials. The glass and resinmolding compound isintroduced into a heatingchamber where it softens. Thismass is then injected into amold cavity that is kept at atemperature below thesoftening point of the resin.The part then cools andsolidifies.Continuous LaminatingFabric or mat is passedthrough a resin dip andbrought together betweencellophane covering sheets;the lay-up is passed through aheating zone and the resin iscured. Laminate thickness andresin content are controlledby squeeze rolls as the variousplies are brought together.Figure14-21(Continued)(b)preforming methods,(c)closed-mold processes. (After illustrations from Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corporation as ab-stracted in R.Nicholls,Composite Construction Materials Handbook, Prentice Hall,Inc.,Englewood Cliffs,N.J.,1976.)T y p e I (n o r m a l )C o m p r e s s i v e s r e n g h , p s i m o i s t -c u r e d a t 70 F500040003000200010000.400.600.400.600.400.600.400.600.500.700.500.700.500.700.500.70T y p e I (n o r m a l )Water, lb/lb of cement80007000600050004000300020001000C o m p r e s s i v e s r e n g h , p s i m o i s t -c u r e d a t 70 FWater, lb/lb of cement(b) Non-air-entrained concreteFigure 14-22Variation in compressive strength for typical concretes (of different ce-ment types,cure times,and air entrainment)as a function of water/cement ratio.(From Design and Control of Concrete Mixtures,11th Ed.,Portland Cement Association,Skokie,Ill.,1968.)。

计算材料学1

1. 1计算材料学/材料设计的历史背景 续

20 世纪 70 年代是初步发展阶段段;到了 20 世纪 80 年代已形成学科。 80 年代中期日本从材料界提出 了用三大材料在分子原子水平上混合,构成杂化 材料的思想。 1985 年日本出版了《新材料开发与 材料设计学》一书,首次提出了材料设计学这一 专门方向,书中介绍了早期的研究与应用情况, 并在大学材料系开设材料设计课程。 1988 年由日 本科学技术厅功能梯度材料的研究任务,提出将 设计-合成-评估三者紧密结合起来,按预定要求做 出材料,并连续组织有关这一课题的国际研讨会。

1.1 计算材料学/材料设计的历史背景 续

随着凝聚态物理、统计物理、固体物理、量 子力学、量子化学等基础学科的发展,以及计算 机能力的极大提高,使得理论和计算在材料研制 过程中的作用越来越大。1999年美国能源部发表 一篇题为:“计算材料学:一场科学革命将成为 现实 ” (http://www. /) 。此文提到: 由于计算机能力的不断提高,材料科学正处于另 一场科学革命的边缘。科学家可能用太拉 (1012) 级以上的计算机通过模拟运算来指导先进材料的 发展,进一步阐明材料是如何形成的

1.1 计算材料学/材料设计的历史背景 续

1989年,美国若干个专业委员会调查分析了美 国八个工业部门(航天,汽车,生物材料,化学, 电子学,能源,金属和通讯等)对材料的需求, 之后编写出版了《90年代的材料科学与工程》 报告。材料设计的发展,使材料科学从定性描 述逐渐进入定量的科学阶段。到了20世纪90年 代,材料设计的研究已成为潮流。目的按需订 做材料,进行性能模拟,性能预报。

GRADING

• • • Class attending Homework and presentation (liu2001612@) Exam

计算材料学-14-2-2

s s

p p

p p

p p

sp2 sp2

sp2

sp2 sp2 sp2

p

sp3 hybrid atomic orbitals

sp3 hybrid orbitals in CH4

Tetrahedral geometry is achieved using four sp3 hybrid orbitals.

材料的结构计算材料学第二章维度零维分子团簇量子点一维纳米线管高聚物dna等二维表面界面超晶格三维固体液体材料按照其维度的分类材料按照其原子结构的分类长程序与局域序晶体液体长程有序短程有序长程无序短程有序长程无序短程无序材料的分类气态液态非晶晶态2dlattice晶格的定义

计算材料学

计算材料学第二章 材料模拟的物理化学基础

Key: charge rearrange in atoms to minimize total energy

化学键(Chemical Bonds)

• Compounds are formed from chemically bound atoms or ions. • Bonding involves only the valence electrons. • Valence electrons are usually the outer electrons in the atoms • One can use the Periodic Table to guide determination of valence electrons

Bonding and antibonding Orbital

Overlap of Wavefunctions

Bonding and antibonding Orbital

计算材料科学课件11.1 计算材料科学简介

第一性原理方法

• 计算表面吉布斯自由能、研究表面吸附机理、表面化学反 应过程、界面力学性质,薄膜生长机理、自组装等。

α-Al2O3/FeAl氢渗透阻挡层中氢的能量和扩散 Reference: Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 38, 7550 (2013)

计算软件

• Quantum ESPRESSO: /

• Siesta: http://departments.icmab.es/leem/siesta/

• Materials Studio

参考书目

• 计算材料科学基础 张跃 谷景华 等 北京航空航天大 学出版社

• Density Functional Theory David S. SHOLL

参考书目

材料学计算的方法

• 量子力学方法 • 分子动力学方法 • Monte Carlo 方法 • 有限元分析方法

量子力学方法

量子力学第一性原理方法可以无需任何实验数据,完全从 材料组成原子的种类以及排列方式出发计算材料性能。该 方法可以研究能量学和电子层次的问题。

分子动力学方法

分子动力学方法通过简化原子间相互作用,可以计算的体 系比量子力学方法能够研究的体系大得多,特别是可以研 究温度、压力等环境因素的影响和动力学问题。

材料学研究对象的空间尺度不断缩小。 材料应用环境的日益复杂化 仅依靠实验室的实验来进行材料研究已经难以满足现代新

材料研究和发展的要求

材料学计算的优越性

计算机模拟技术可以根据有关的基本理论,在计算机虚拟 环境下从纳观、微观、介观和宏观的不同尺度对材料进行 多层次研究,也可以模拟超高温、超高压等极端环境下的 材料服役性能,模拟材料在服役条件下的性能演变规律、 失效机理,进而实现材料服役性能的改善和材料设计。

计算材料学

Gradient Corrected Methods

Gradient Corrected or Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA): 泛函不仅决定 于电子密度,还决定于电子密度的梯度。

交换项 Perdew and Wang (PW86): 修正 LSDA 的泛函形式:加入高阶项。

局域密度近似

• 局域密度近似最早是由Kohn W和Sham L.J提出来的,这是一种既简单可行而又很 有效的近似,其基本思想是在局域密度近 似中,利用均匀电子气密度函数来获得非 均匀电子气的交换关联泛函。 • 交换关联能可以写为式

E xc [ ] dr ( r ) xc [ ( r )]

绝热近似

• 波恩(Born M)和奥本海默(Oppenheimer J.E) 提出了绝热近似,根据这种近似,可 以将原子核运动和电子的运动分开。通过 绝热近似,可以获得多电子的薛定谔方程

H (r, R) E (r, R)

H

H H e H N H e N

电子作 用项 原子核 作用项 电子和原子核 相互作用项

计算材料学

杨振华

第一性原理计算方法

•

第一性原理方法是一种理想的研究方法,物理学家常 称第一性原理方法,化学家常称为“从头算”,但是 本质都是一样的。就是从材料的电子结构出发,应用 量子力学理论,只借助于普朗克常数h、电子的静止 质量m0、电子电量e、光速c和波尔兹曼常数k这五个 基本的物理常量,以及某些合理的近似而进行计算。 这种计算不需要任何其他可调的(经验的或拟合的)参 数就可以如实地求解材料的一些基本物理性能参数。 通过求解多粒子系统总能量的办法来分析体系的电子 结构和原子核构型的关系,从而确定系统的性质 。

《材料科学与工程基础》习题和思考题及答案

《材料科学与工程基础》习题和思考题及答案四川大学考研bbs (. scuky. /bbs)欢迎您报考川大!《材料科学与工程基础》习题和思考题及答案第二章2T.按照能级写出N、0、Si、Fe、Cu、Br原子的电子排布 (用方框图表示)。

2-2.的镁原子有13个中子,11. 17%的镁原子有14个中子,试计算镁原子的原子量。

2-3.试计算N壳层内的最大电子数。

若K、L、M、N壳层中所有能级都被电子填满时,该原子的原子序数是多少?2-4.计算0壳层内的最大电子数。

并定出K、L、M、N、0壳层中所有能级都被电子填满时该原子的原子序数。

2-5.将离子键、共价键和金属键按有方向性和无方向性分类,简单说明理由。

2-6.按照杂化轨道理论,说明下列的键合形式:(1)C02的分子键合(2)甲烷CH4的分子键合(3)乙烯C2II4的分子键合(4)水1120的分子键合(5)苯环的分子键合(6)譏基中C、0间的原子键合2-7.影响离子化合物和共价化合物配位数的因素有那些?2-8.试解释表2-3-1中,原子键型与物性的关系?2-9. 0°C时,水和冰的密度分别是1. 0005g/cm3和0. 95g/cm3,解释这一现象?2-10.当CN=6时,K+离子的半径为0. 133nm(a)当CN二4时,半径是多少?(b)CN=8时,半径是多少?2-11. (R利用附录的资料算出一个金原子的质量?(b)每mm3的金有多少个原子?(c)根据金的密度,某颗含有1021个原子的金粒,体积是多少?(d)假设金原子是球形(rAu=0.144lnm), 并忽略金原子之间的空隙,则1021个原子占多少体积?(e)这些金原子体积占总体积的多少百分比?2-12. 一个CaO的立方体晶胞含有4个52+离子和4个02-离子,每边的边长是0. 478nm,则CaO的密度是多少?2-13.硬球模式广泛的适用于金属原子和离子,但是为何不适用于分子?2-14.计算(Q)面心立方金属的原子致密度;(b)面心立方化合物NaCl的离子致密度(离子半径rNa+=0. 097, rCl-二0.181);(C)由计算结果,可以引出什么结论?2-15.铁的单位晶胞为立方体,晶格常数a=0. 287nm,请由铁的密度算出每个单位晶胞所含的原子个数。

计算材料学-14-4-3

计算材料学计算材料学第四章原子模拟方法陈效双中科院上海技术物理研究所、上海科技大学本章提纲1.原子模拟基础2.结构优化方法3.分子动力学方法4.Monte-Carlo方法计算材料学第四章4-3. 分子动力学方法分子动力学提纲4-3.1 分子动力学概论4-3.2 分子动力学的基本流程和算法4-3.3 不同系综下的分子动力学4-3.4 分子动力学模拟结果的分析4-3.5 加速分子动力学What is MD?•What is Molecular Dynamics?–A technique to move atoms along the paths they should follow according to F=ma (This is calledintegrating the equations of motion)导论分子动力学是在原子、分子水平上求解多体问题的重要的计算机模拟方法,可以预测纳米尺度上的材料动力学特性。

通过求解所有粒子的运动方程,分子动力学方法可以用于模拟与原子运动路径相关的基本过程。

在分子动力学中,粒子的运动行为是通过经典的Newton运动方程所描述。

分子动力学的发展史按照由许多经典粒子构成的系统的演化;每个粒子同时相互作用(通常-且也含有“硬球”接触相互作用),和经历外部的附加势;尽管是具有比在电子情形更简单的信息内容,系统是一个许多体问题。

分子动力学的三个主要目标What is MD Good For?•Trajectories of atoms (e.g., during collisions, reactions, etc.)•Thermodynamic averages (e.g., energy, pressure, volume, etc.)•Transport coefficients (e.g., diffusion constant, thermal conductivity, etc.)•Vibrational density of states (phonon spectra and beyond)分子动力学提纲4-3.1 分子动力学概论4-3.2 分子动力学的基本流程和算法4-3.3 不同系综下的分子动力学4-3.4 分子动力学模拟结果的分析4-3.5 加速分子动力学分子动力学的操作步骤•Initialize:select positions and velocities •Integrate:compute all forces,and determine new positions•Equilibrate:let the system reach equilibrium (i.e.,lose memory of initial conditions)•Average:accumulate quantities of interest分子动力学的典型流程步骤一:初始化粒子初始速度的Maxwell-Boltzmann分布步骤二:牛顿运动方式的积分The Basic MD Problem: Time Step1. Start with positions and velocities at time t k:r(t k),v(t k)2. Find the forces on each particle at t k: F(t k)3. Find the accelerations of each particle at t k: a(t k)4. Use r(t k), v(t k), a(t k) to get the correct positions andvelocities at t k+1 = t + δt : r(t k+1), v(t k+1)5. Iterate this process to evolve the system in time*** How do I do step 4? ***Use a Taylor expansion!!19Velocity Verlet Algorithm•r(t+δt) = r(t) + v(t)δt + 1/2a(t)δt2•v(t+δt) = v(t) + 1/2[a(t)+a(t+δt)]δt•Velocities appear explicitly and make use of a at t and t+δt, so this is like a predictor-corrector approach•This is probably the most commonly used algorithm •Fast, simple, accurate trajectories, energy conservation for long time step有限差分方法各种算法,如Verlet,velocity verlet,leapfrog Verlet,Gear predictor-corrector等,它们的本质都是有限差分方法。

第十四章北航 材料力学 全部课件 习题答案

dM qRd R1cos( ) qR21cos( )d

所以,在切向载荷 q 与多余未知力 FBy 作用下,截面的弯矩为

6

M

(

)

0

qR2

1

cos(

)d

FBy

R

sin

qR2

(

sin

)

FBy

R

sin

(b)

在图 c 所示铅垂单位载荷作用下,截面的弯矩则为

M () Rsin

根据单位载荷法,得相当系统横截面 B 的铅垂位移为

1

9F 4

2FN1

2

3F 2

FN1

1

0

得

FN1 F

ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ

由此得

FN2

F 4

,

FN3

F 2

2. 角位移计算

施加单位力偶如图 d 所示,并同样以刚性杆 BC 与 DG 为研究对象,则由平衡方程

11

M B 0, 1 F N2 2a F N3 3a 0

MG 0, F N2 2a F N3 a 0

M ( ) qR2 4 sin π

在图 d 所示水平单位载荷作用下,截面的弯矩则为

M () R(1cos)

于是,得截面 B 的水平位移为

ΔBx

1 EI

π/2

R(1

0

cos )qR2

4 π

sin

Rd

qR4 EI

π2 8

π 2

2 π

1

( )

14-5 图示桁架,各杆各截面的拉压刚度均为 EA,试求杆 BC 的轴力。

MG 0, F 3a FN1 3a FN2 2a FN3 a 0

得

FN2

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

2.

M.I. Eremets, V.V. Struzhkin, H.K. Mao, R.J. Hemley, Science 293: 272-274 (2001).

27

材料模拟的重要性-解释相变机制

Two typical reason of pressure-induced metallization 1. Structural transition from low coordination insulator to a high coordination metallic phase (e.g., Si, Ge) Band overlap due to the increased interatomic interactions with pressure (e.g., I)

25

材料模拟的重要性-预言新的结构相

Phys. Rev. B60, 14177(1999). (理论预言)

Germanium Clathrate

A. M. Guloy, et al., Nature 443, 320 (2006). (实验合成)

26

材料模拟的重要性-解释相变机制

1. Boron (in β-phase) transforms from a nonmetal to a metal (superconductor) at about 160 GPa. The critical temperature of the transition increases from 6 K at 175 GPa to 11.2 K at 250 GPa.

Gerbrand Ceder, “COMPUTATIONAL MATERIALS SCIENCE: Predicting Properties from Scratch”, Science, Vol 280, Issue 5366, 1099-1100 , 15 May 1998

17

Science列举的计算材料成功应用例子

16

计算模拟与设计在材料研究中的地位

It has always been a dream of materials researchers to design a new material completely on paper, optimizing the composition and processing steps in order to achieve the properties required for a given application.

Al5Ru2: orthorhombic

AlRu: cubic Crystal structures of Al-Ru bimetallic alloys

23

模拟的重要性-材料的结构和物性计算

AlRu: cubic

Lattice constant (Å) Experiment Theory 2.991~ 3.036 3.002 Bulk modulus (GPa) 207 202 Young modulus (GPa) 267, 260±10 232 Heat of formation (kJ/mol) -124.1±3.3 -126.8

1. 设计新型材料和器件 i. 高性能磁光记录材料:Tb/Bi/FeCo与Tb/Pb/FeCo超晶格

ii. 超硬材料:C3N4(硬度可以媲美金刚石?) iii. 新型锂电池阴极材料:LixCoO2 的替代品,Al替代Co? 2. 预言晶体结构(e.g.,针对70种合金,>120晶体进行10000个 第一性原理能量计算,六个月) 3. 计算材料相图 4. 获得实验难以实现的极端条件下(如高温、高压)的材料结 构与物性

材料模拟的重要性-材料的电子结构

Li intercalation in carbon nanotube

21

材料模拟的重要性-材料的相图计算

22

材料模拟的重要性-材料的结构计算

Al6Ru: orthorhombic Al2Ru: orthorhombic Al3Ru2: tetragonal

Al13Ru4: monoclinic

11

计算材料学涉及的内容

计算材料学的发展与计算机科学与技术的迅猛发展 密切相关。 极难完成的一些材料计算,如材料的量子力学计算 等,现在使用微机就能够完成,超级计算机的出现 将带来材料学的大发展。 计算材料物理和计算理论学家的发展,模型与算法 的成熟,使得材料计算的应用更广泛。 因此,计算材料学基础知识的掌握已成为现代材料 研究者必备的技能之一 。

计算材料学

计算材料学第一章 导论

陈效双

中科院上海技术物理研究所、上海科技大学

科学计算的发展及其重要意义

“科学计算已经是继理论科学、实验科学之后,人类认识 与征服自然的第三种科学方法”。--原南开大学校长候 自新

Moore定律(1965): 计算机的CPU速度每1.5 年增加一倍。

2

计算机实验(模拟)的概念与步骤

1998 Nobel Prize in Chemistry to Walter Kohn and John Pople

14

计算模拟与设计在材料研究中的地位

美国若干个专业委员会(1989) 现代理论和计算机的进步,使得材料科学与 工程的性质正在发生变化。材料的计算机分析与 模型化的进展,将使材料科学从定性描述逐渐进 入定量描述阶段。

12

计算材料学涉及的内容

超级计算机和理论方法的发展

上海超级计算中心 魔方(top10) 材料设 计软件

LLNL IBM SP power3 Rmax 红外物理国 家实验室 7.22Tflops

There are several types of computers

13

计算材料学涉及的内容

第一性原理 的密度函数 理论预测材 料的结构等 许多性质。

• • • • • •

明确所要研究的物理现象 发展合适的理论和数学模型描述该现象 将数学模型转换成适于计算机编程的形式 发展和/或应用适当的数值算法 编写模拟程序 开展计算机实验,分析结果

3

计算材料学的概念

计算材料学是是近年里飞速发展的一门新兴交叉学科。它综合 了凝聚态物理、材料物理学、理论化学、材料力学和工程力学、 计算机算法等多个相关学科。 本学科的目的是利用现代高速计算机,模拟材料的各种物理化 学性质,深入理解材料从微观到宏观多个尺度的各类现象与特 征,并对于材料的结构和物性进行理论预言,从而达到设计新 材料的目的。

《90年代的材料科学与工程》

15

计算模拟与设计在材料研究中的地位

美国国家科学研究委员会(1995) 材料设计(materials by design)一词正在 变为现实,它意味着在材料研制与应用过程中理 论的份量不断增长,研究者今天已经处在应用理 论和计算来设计材料的初期阶段。

《材料科学的计算与理论技术》

纳米二极管

10

计算材料学涉及的内容

依靠实验进行材料研究已经难以满足现代新材料研 究和发展的要求。 计算机模拟,根据基本理论,从纳观、微观、介观 和宏观的不同尺度对材料进行多层次研究,可模拟 超高温、超高压等极端环境下的材料服役性能,模 拟材料在服役条件下的性能演变规律、失效机理, 实现材料服役性能的改善和材料设计。 因此,在现代材料学领域中,计算机“实验”已成 为与实验室实验同样重要的研究手段,而且随着计 算材料学的不断发展,它的作用会越来越大。

5

计算材料学涉及的内容

主要包括两个方面的内容: 计算模拟,即从实验数据出发,通过建立数学模型及 数值计算,模拟实际过程; 材料的计算机设计,即直接理论模型和计算,预测或 设计材料结构与性能。 前者使材料研究不仅仅停留在实验结果和定性的讨论 上,实验结果上升为一般的、定量的理论;后者则使 材料的研究与开发更具方向性、前瞻性,有助于原始 性创新,可以大大提高研究效率。 因此,计算材料学是连接材料学理论与实验的桥梁。

28

材料模拟的重要性-解释相变机制

Experimental metallization: Gap closure (at 160 GPa) instead of structural Transformation from α-boron to bct (at 240 GPa)

Phys. Rev. B66, 092101(2002).

19

材料模拟的重要性-材料的基本性质

Charge Density in LiCoO2

4 3 2 1 0 -1 -2

Band structure of LiMnO2

-3.6 -3.7 -3.8 -3.9 -4 -4.1 -4.2 -4.3

20

3.5

3.7

3.9

4.1

4.3

4.5

Energy versus lattice parameter for fcc Al

8

计算材料学涉及的内容

当今许多关键技术上的材料,界面和表面需原子和 键水平认识。

纳米晶体

材料组装

9

计算材料学涉及的内容

未来超小型化器件的关键材料,单个原子(电子) 的增减,性质将变化,从单量子结构认识。

C48B12 S -(CH2)nC48N12 S

Gold lead

Gold lead

单分子二极管

18

材料模拟的重要性

Understanding How, why, where of phenomenon • How does H diffuse through A? • Why is A harder than B? • Where does A bind to B?

Prediction Parameter values, new phenomena • What is the diffusivity of H in A? • How hard is A? • Will A bind to B and how strongly?