卡西欧翻译比赛

第五届CASIO杯翻译竞赛英语组原文

第五届CASIO杯翻译竞赛英语组原文OpticsManini Nayar When I was seven,my friend Sol was hit by lightning and died.He was on a rooftop quietly playing marbles when this happened.Burnt to cinders,we were told by the neighbourhood gossips.He'd caught fire,we were assured,but never felt a thing.I only remember a frenzy of ambulances and long clean sirens cleaving the silence of that damp October ter,my father came to sit with me.This happens to one in several millions,he said,as if a knowledge of the bare statistics mitigated the horror.He was trying to help,I think.Or perhaps he believed I thought it would happen to me.Until now,Sol and I had shared everything;secrets,chocolates, friends,even a birthdate.We would marry at eighteen,we promised each other,and have six children,two cows and a heart-shaped tattoo with'Eternally Yours'sketched on our behinds.But now Sol was somewhere else,and I was seven years old and under the covers in my bed counting spots before my eyes in the darkness.After that I cleared out my play-cupboard.Out went my collection of teddy bears and picture books.In its place was an emptiness,the oak panels reflecting their own woodshine.The space I made seemed almost holy,though mother thought my efforts a waste.An empty cupboard is no better than an empty cup,she said in an apocryphal aside.Mother always filled things up-cups,water jugs,vases,boxes,arms-as if colour and weight equalled a superior quality of life.Mother never understood that this was my dreamtime place.Here I could hide, slide the doors shut behind me,scrunch my eyes tight and breathe in another world. When I opened my eyes,the glow from the lone cupboard-bulb seemed to set the polished walls shimmering,and I could feel what Sol must have felt,dazzle and darkness.I was sharing this with him,as always.He would know,wherever he was, that I knew what he knew,saw what he had seen.But to mother I only said that I was tired of teddy bears and picture books.What she thought I couldn't tell,but she stirred the soup-pot vigorously.One in several millions,I said to myself many times,as if the key,the answer to it all,lay there.The phrase was heavy on my lips,stubbornly resistant to knowledge. Sometimes I said the words out of context to see if by deflection,some quirk of physics,the meaning would suddenly come to me.Thanks for the beans,mother,I said to her at lunch,you're one in millions.Mother looked at me oddly,pursed her lips and offered me more rice.At this club,when father served a clean ace to win the Retired-Wallahs Rotating Cup,I pointed out that he was one in a million.Oh,the serve was one in a million,father protested modestly.But he seemed pleased.Still, this wasn't what I was looking for,and in time the phrase slipped away from me,lost its magic urgency,became as bland as'Pass the salt'or'Is the bath water hot?'If Sol was one in a million,I was one among far less;a dozen,say.He was chosen.I was ordinary.He had been touched and transformed by forces I didn't understand.I was left cleaning out the cupboard.There was one way to bridge the chasm,to bring Sol back to life,but I would wait to try it until the most magical of moments.I would wait until the moment was so right and shimmering that Sol would have to come back. This was my weapon that nobody knew of,not even mother,even though she had pursed her lips up at the beans.This was between Sol and me.The winter had almost guttered into spring when father was ill.One February morning,he sat in his chair,ashen as the cinders in the grate.Then,his fingers splayed out in front of him,his mouth working,he heaved and fell.It all happened suddenly, so cleanly,as if rehearsed and perfected for weeks.Again the sirens,the screech of wheels,the white coats in perpetual motion.Heart seizures weren't one in a million. But they deprived you just the same,darkness but no dazzle,and a long waiting.Now I knew there was no turning back.This was the moment.I had to do it without delay;there was no time to waste.While they carried father out,I rushed into the cupboard,scrunched my eyes tight,opened them in the shimmer and called out 'Sol!Sol!Sol!'I wanted to keep my mind blank,like death must be,but father and Sol gusted in and out in confusing pictures.Leaves in a storm and I the calm axis.Here was father playing marbles on a roof.Here was Sol serving ace after ace. Here was father with two cows.Here was Sol hunched over the breakfast table.Thepictures eddied and rushed.The more frantic they grew,the clearer my voice became, tolling like a bell:'Sol!Sol!Sol!\'The cupboard rang with voices,some mine,some echoes,some from what seemed another place-where Sol was,maybe.The cupboard seemed to groan and reverberate,as if shaken by lightning and thunder.Any minute now it would burst open and I would find myself in a green valley fed by limpid brooks and red with hibiscus.I would run through tall grass and wading into the waters,see Sol picking flowers.I would open my eyes and he'd be there, hibiscus-laden,laughing.Where have you been,he'd say,as if it were I who had burned,falling in ashes.I was filled to bursting with a certainty so strong it seemed a celebration almost.Sobbing,I opened my eyes.The bulb winked at the walls.I fell asleep,I think,because I awoke to a deeper darkness.It was late,much past my bedtime.Slowly I crawled out of the cupboard,my tongue furred,my feet heavy. My mind felt like lead.Then I heard my name.Mother was in her chair by the window,her body defined by a thin ray of moonlight.Your father Will be well,she said quietly,and he will be home soon.The shaft of light in which she sat so motionless was like the light that would have touched Sol if he'd been lucky;if he had been like one of us,one in a dozen,or less.This light fell in a benediction,caressing mother,slipping gently over my father in his hospital bed six streets away.I reached out and stroked my mother's arm.It was warm like bath water,her skin the texture of hibiscus.We stayed together for some time,my mother and I,invaded by small night sounds and the raspy whirr of crickets.Then I stood up and turned to return to my room.Mother looked at me quizzically.Are you all right,she asked.I told her I was fine,that I had some cleaning up to do.Then I went to my cupboard and stacked it up again with teddy bears and picture books.Some years later we moved to Rourkela,a small mining town in the north east, near Jamshedpur.The summer I turned sixteen,I got lost in the thick woods there. They weren't that deep-about three miles at the most.All I had to do was cycle for all I was worth,and inminutes I'd be on the dirt road leading into town.But a stir in the leaves gave me pause.I dismounted and stood listening.Branches arched like claws overhead.The sky crawled on a white belly of clouds.Shadows fell in tessellated patterns of grey and black.There was a faint thrumming all around,as if the air were being strung and practised for an overture.And yet there was nothing,just a silence of moving shadows,a bulb winking at the walls.I remembered Sol,of whom I hadn't thought in years.And foolishly again I waited,not for answers but simply for an end to the terror the woods were building in me,chord by chord,like dissonant music.When the cacophony grew too much to bear, I remounted and pedalled furiously,banshees screaming past my ears,my feet assuming a clockwork of their own.The pathless ground threw up leaves and stones, swirls of dust rose and settled.The air was cool and steady as I hurled myself into the falling light.。

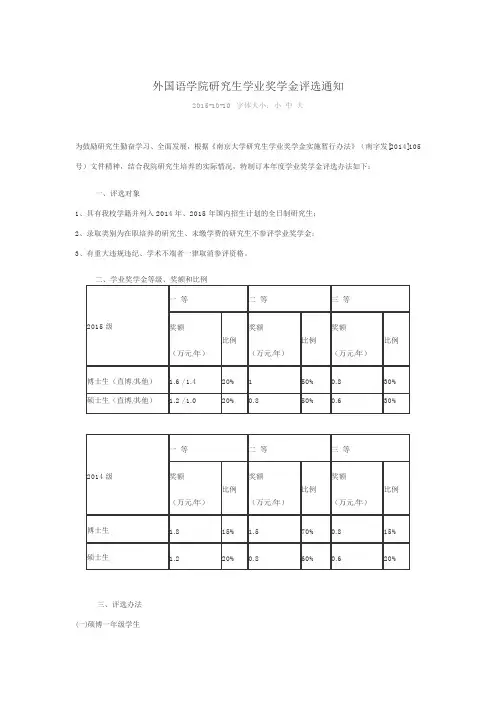

外国语学院研究生学业奖学金评选通知

1、博士一年级学生:以入学考试成绩为主,参考学术潜力(近三年代表性学术成果)确定名单。

申请者须填写《2015级博士研究生学院奖学金申请表》,详见附件一。

2、硕士一年级学生:推荐免试硕士新生原则上参评一等学业奖学金,二、三等学业奖学金根据入学成绩确定名单。

(二)硕博二年级学生所有学生须填写《2014级研究生学业奖学金申请表》,详见附件2。

其中:1、博士二年级学生:以博士学科综合考试结果为主,参考学术成果(入学以来代表性学术成果)确定名单。

2、硕士二年级学生:(1)学术型硕士:学业成绩(仅计算C类课程的平均分,B类和D类课程中成绩在90分以上的,每一门加3分,最高可加12分)与中期考核成绩各占100分;科研论文发表加分政策如下:A&HCI论文、SSCI论文或一流期刊论文一篇加30分;CSSCI论文一篇加15分;CSSCI扩展版、CSSCI集刊或北大中文核心期刊论文一篇加5分;论文必须为正式发表的论文。

用稿通知不可作为加分依据。

(2)专业型硕士:以学业成绩为主(不含第二外语),同时参考翻译成果、实践活动。

2015年10月15日12点前,申请人将填写的相关学业奖学金申请表电子版发至njusfspingjiang@,电子表格需为03版excel格式,请勿发pdf版,excel的文件名为“学号+姓名”,邮件名称为“学号+姓名”(请勿加上任何其他信息)。

格式错误者、逾期不发送电子版者不予参评。

相关纸质材料,请在10月15日12点以前交至外院楼225办公室,材料接收时间周一——周四上班时间。

外国语学院将成立奖学金评审小组,根据申请者材料现场打分、排序并公示。

南京大学外国语学院2015年10月10日附件1、/uploadfck/files/2015级博士研究生学业奖学金申请表(1).xls附件2、/uploadfck/files/2014级研究生学业奖学金申请表.xls4、外国语学院将成立奖学金评审小组,根据申请者面试情况和申请材料现场打分、排序并公示。

翻译练习二

第十一届CASIO杯翻译竞赛原文(英语组)To evoke the London borough of Diston, we turn to the poetry of Chaos:Each thing hostileTo every other thing: at every pointHot fought cold, moist dry, soft hard, and the weightlessResisted weight.So Des lived his life in tunnels. The tunnel from flat to school, the tunnel (not the same tunnel) from school to flat. And all the warrens that took him to Grace, and brought him back again. He lived his life in tunnels … And yet for the sensitive soul, in Diston Town, there was really only one place to look. Where did the eyes go? They went up, up.School –Squeers Free, under a sky of white: the weakling headmaster, the demoralised chalkies in their rayon tracksuits, the ramshackle little gym with its tripwires and booby traps, the Lifestyle Consultants (Every Child Matters), and the Special Needs Coordinators (who dealt with all the ‘non-readers’). In addition, Squeers Free set the standard for the most police call-outs, the least GCSE passes, and the highest truancy rates. It also led the pack in suspensions, expulsions, and PRU ‘offrolls’; such an offroll –a transfer to a Pupil Referral Unit –was usually the doorway to a Youth Custody Centre and then a Young Offender Institution. Lionel, who had followed this route, always spoke of his five and a half years (on and off) in a Young Offender Institution (or Yoi, as he called it) with rueful fondness, like one recalling a rite of passage – inevitable, bittersweet. I was out for a month, he would typically reminisce. Then I was back up north. Doing me Yoi.* * *On the other hand, Squeers Free had in its staff room an exceptional Learning Mentor – a Mr Vincent Tigg.What’s going on with you, Desmond? You were always an idle little sod. Now you can’t get enough of it. Well, what next?I fancy modern languages, sir. And history. And sociology. And astronomy. And –You can’t study everything, you know.Yes I can. Renaissance boy, innit.… You want to watch that smile, lad. All right. We’ll see about you. Now off you go.And in the schoolyard? On the face of it, Des was a prime candidate for persecution. He seldom bunked off, he never slept in class, he didn’t assault the teachers or shoot up in the toilets – and he preferred the company of the gentler sex (the gentler sex, at Squeers Free, being quite rough enough). So in the normal courseof things Des would have been savagely bullied, as all the other misfits (swats, wimps, four-eyes, sweating fatties) were savagely bullied – to the brink of suicide and beyond. They called him Skiprope an d Hopscotch, but Des wasn’t bullied. How to explain this? To use Uncle Ringo’s favourite expression, it was a no-brainer. Desmond Pepperdine was inviolable. He was the nephew, and ward, of Lionel Asbo.It was different on the street. Once a term, true, Lionel escorted him to Squeers Free, and escorted him back again the same day (restraining, with exaggerated difficulty, the two frothing pitbulls on their thick steel chains). But it would be foolish to suppose that each and every gangbanger and posse-artist (and every Yardie and jihadi) in the entire manor had heard tell of the great asocial. And it was different at night, because different people, different shapes, levered themselves upward after dark … Des was fleet of foot, but he was otherwise unsuited to life in Diston Town. Second or even first nature to Lionel (who was pronounced ‘uncontrollable’ at the age of eighteen months), violence was alien to Des, who always felt that violence – extreme and ubiquitous though it certainly seemed to be –came from another dimension.So, this day, he went down the tunnel and attended school. But on his way home he feinted sideways and took a detour. With hesitation, and with deafening self-consciousness, he entered the Public Library on Blimber Road. Squeers Free had a library, of course, a distant Portakabin with a few primers and ripped paperbacks scattered across its floor … But this: rank upon rank of proud-chested bookcases, like lavishly decorated generals. By what right or title could you claim any share of it? He entered the Reading Room, where the newspapers, firmly clamped to long wooden struts, were apparently available for scrutiny. No one stopped him as he approached.He had of course seen the dailies before, in the corner shop and so on, and there were G ran’s Telegraph s, but his experience of actual newsprint was confined to the Morning Lark s that Lionel left around the flat, all scrumpled up, like origami tumbleweeds (there was also the occasional Diston Gazette). Respectfully averting his eyes from the Times, the Independent, and the Guardian, Des reached for the Sun, which at least looked like a Lark, with its crimson logo and the footballer’s fiancée on the cover staggering out of a nightclub with blood running down her neck. And, sure enough, on page three (News in Briefs) there was a hefty redhead wearing knickers and a sombrero.But then all resemblances ceased. You got scandal and gossip, and more girls, but also international news, parliamentary reports, comment, analysis … Until now he had accepted the Morning Lark as an accurate reflection of reality. Indeed, he sometimes thought it was a local paper (a light-hearted adjunct to the Gazette), such was its fidelity to the customs and mores of his borough. Now, though, as he stood there with the Sun quivering in his hands, the Lark stood revealed for what it was – a daily lads’ mag, perfunctorily posing as a journal of record.The Sun, additionally to recommend it, had an agony column presided over not by the feckless Jennaveieve, but by a wise-looking old dear called Daphne, who dealtsympathetically, that day, with a number of quite serious problems and dilemmas, and suggested leaflets and helplines, and seemed genuinely …第十一届CASIO杯翻译竞赛(英语组)译文著/ [英]马丁·艾米斯(Martin Amis)译/中南民族大学2014级MTI曾诗琴为了唤起对伦敦迪斯顿自治市的回忆,我们可以翻阅混沌时期的诗歌:万物相生相克:无处不是冷热相争,干湿相对,刚柔相斗,无重抵抗有重。

卡西欧杯翻译竞赛历年赛题及答案

第九届卡西欧杯翻译竞赛原文(英文组)来自: FLAA(《外国文艺》)Meansof Delive ryJoshua CohenSmuggl ing Afghan heroin or womenfrom Odessa wouldhave been morerepreh ensib le, but more logica l. Youknowyou’reafoolwhenwhatyou’redoingmakeseven the post office seem effici ent. Everyt hingI was packin g into thisunwiel dy, 1980s-vintag e suitca se was availa ble online. Idon’tmeanthatwhenIarrive d in Berlin I couldhave ordere dmoreLevi’s510s for next-day delive ry. I mean, I was packin g books.Not just any books— thesewere all the same book, multip le copies. “Invali d Format: An Anthol ogy of Triple Canopy, Volume 1”ispublis hed, yes, by Triple Canopy, an online magazi ne featur ing essays, fictio n, poetry and all variet y of audio/visualcultur e, dedica ted — click“About”—“toslowin g down the Intern et.”Withtheirbook, the firstin a planne d series, the editor s certai nly succee ded. They were slowin g me down too, just fine.“Invali d Format”collec ts in printthe magazi ne’sfirstfour issues and retail s, ideall y, for $25. But the 60 copies I was courie ring, in exchan ge for a couchand coffee-pressaccess in Kreuzb erg, wouldbe givenaway. For free.Untillately the printe d book change d more freque ntly, but less creati vely, than any othermedium. If you though t“TheQuotab le Ronald Reagan”wastooexpens ive in hardco ver, you couldwait a year or less for the same conten t to go soft. E-books, whichmade theirdebutin the 1990s, cut costseven more for both consum er and produc er, though as the Intern et expand ed thoserolesbecame confus ed.Self-publis hed book proper tiesbeganoutnum berin g, if not outsel ling, theirtradeequiva lents by the mid-2000s, a situat ion furthe r convol utedwhen the conglo merat es starte d“publis hing”“self-publis hed books.”Lastyear, Pengui n became the firstmajortradepressto go vanity: its Book Countr y e-imprin t will legiti mizeyour “origin al genrefictio n”forjustunder$100. Theseshifts make small, D.I.Y.collec tives like Triple Canopy appear more tradit ional than ever, if not just quixot ic — a word derive d from one of the firstnovels licens ed to a publis her.Kenned y Airpor t was no proble m, my connec tionat Charle s de Gaulle went fine. My luggag e connec ted too, arrivi ng intact at Tegel. But immedi ately afterimmigr ation, I was flagge d. A smalle r wheeli e bag held the clothi ng. As a custom s offici alrummag ed throug h my Hanes, I prepar ed for what came next: the larger case, caster s broken, handle rusted—I’mpretty sure it had alread y been Used when it was givento me for my bar mitzva h.Before the offici al couldopen the clasps and startpoking inside, I presen ted him with the docume nt the Triple Canopy editor, Alexan der Provan, had e-mailed me — the nightbefore? two nights before alread y? I’dbeenuponeofthosenights scouri ng New York City for a printe r. No one printe d anymor e. The docume nt stated, inEnglis h and German, that thesebookswere books. They were promot ional, to be givenaway at univer sitie s, galler ies, the Miss Read art-book fair at Kunst-Werke.“Allaresame?”theoffici al asked.“Allegleich,”Isaid.An olderguardcame over, prodde d a spine, said someth ingIdidn’tget. The younge r offici al laughe d, transl ated,“Hewantsto know if you read everyone.”At lunchthe next day with a musici an friend. In New York he played twicea month, ate food stamps. In collap singEuropehe’spaid2,000 eurosa nightto play aquattr ocent o church.“Whereare you handin g the booksout?”heasked.“Atanartfair.”“Whyanartfair?Whynotabookfair?”“It’sanart-bookfair.”“Asoppose d to a book-bookfair?”I told him that at book-book fairs, like the famous one in Frankf urt, they mostly gave out catalo gs.Taking trains and tramsin Berlin, I notice d: people readin g. Books, I mean, not pocket-size device s that bleepas if censor ious, on whicheven Shakes peare scanslike a spread sheet. Americ ans buy more than half of all e-bookssold intern ation ally—unless Europe ans fly regula rly to the United States for the sole purpos e ofdownlo ading readin g materi al from an Americ an I.P. addres s. As of the evenin g I stoppe d search ing the Intern et and actual ly went out to enjoyBerlin, e-booksaccoun ted for nearly 20 percen t of the salesof Americ an publis hers. In German y, howeve r, e-booksaccoun ted for only 1 percen t last year. I beganasking themultil ingua l, multi¬ethnic artist s around me why that was. It was 2 a.m., at Soho House, a privat eclubI’dcrashe d in the former Hitler¬jugend headqu arter s. One instal latio nistsaid, “Americ ans like e-booksbecaus ethey’reeasier to buy.”Aperfor mance artist said, “They’realsoeasier not to read.”Trueenough: theirpresen ce doesn’tremindyouofwhatyou’remissin g;theydon’ttake up spaceon shelve s. The next mornin g, Alexan der Provan and I lugged the booksfor distri butio n, gratis. Questi on: If booksbecome mere art object s, do e-booksbecome concep tualart? Juxtap osing psychi atric case notesby the physic ian-noveli st RivkaGalche n with a dramat icall y illust rated invest igati on into the devast ation of New Orlean s, “Invali d Format”isamongthe most artful new attemp ts to reinve nt the Web by the codex, and the codexby the Web. Its texts“scroll”: horizo ntall y, vertic ally; titlepagesevoke“screen s,”refram ing conten t that follow s not unifor mly and contin uousl y but rather as a welter of column shifts and fonts. Its closes t predec essor s mightbe mixed-mediaDada (Ducham p’sloose-leafed, shuffl eable“GreenBox”); or perhap s“ICanHasCheezb urger?,”thebest-sellin g book versio n of the pet-pictur es-with-funny-captio ns Web site ICanHa sChee zburg ; or simila r volume s fromStuffW hiteP eople Like.com and Awkwar dFami lyPho . Theselatter booksare merely the kitsch iestproduc ts of publis hing’srecent enthus iasmfor“back-engine ering.”They’repseudo liter ature, commod ities subjec t to the samerevers ing proces s that for over a centur y has paused“movies”into“stills”— into P.R. photos and dorm poster s — and notate d pop record ingsfor sheetmusic.Admitt edlyIdidn’thavemuchtimetoconsid er the implic ation s of adapti ve cultur e in Berlin. I was too busy dancin gto“IchLiebeWie Du Lügst,”aka“LovetheWayYou Lie,”byEminem, and fallin g asleep during“Bis(s) zum Ende der Nacht,”aka“TheTwilig ht Saga: Breaki ng Dawn,”justafterthe dubbed Bellacriesover herunlike ly pregna ncy, “Dasistunmögl ich!”— indeed!Transl ating medium s can seem just as unmögl ich as transl ating betwee n unrela ted langua ges: therewill be confus ions, distor tions, techni cal limita tions. The Web ande-book can influe nce the printbook only in matter s of styleand subjec t — no links, of course, just theirmetaph or. “Theghostin the machin e”can’tbeexorci sed, onlyturned around: the machin e inside the ghost.As for me, I was haunte d by my suitca se. The extraone, the empty. My last day in Kreuzb erg was spentconsid ering its fate. My wheeli e bag was packed. My laptop was stowed in my carry-on. I wanted to leavethe pleath er immens ity on the corner of Kottbu sserDamm, down by the canal,butI’ve neverbeen a waster. I brough t it back. It sits in the middle of my apartm ent, unreve rtibl e, only improv able, hollow, its lid floppe d open like the coverof a book.传送之道约书亚·科恩走私阿富汗的海洛因和贩卖来自敖德萨的妇女本应受到更多的谴责,但是也更合乎情理。

2013年第十届卡西欧casio翻译比赛原文

158Humans are animals and like all animals we leave tracks as we walk: signs of passage made in snow, sand, mud, grass, dew, earth or moss. The language of hunt-ing has a luminous word for such mark-making: ‘foil’. A creature’s ‘foil’ is its track. We easily forget that we are track-makers, though, because most of our journeys now occur on asphalt and concrete – and these are substances not easily impressed.‘Always, everywhere, people have walked, veining the earth with paths visible and invisible, symmetrical or meandering,’ writes Thomas Clark in his enduring prose-poem ‘In Praise of Walking’. It’s true that, once you begin to notice them, you see that the land-scape is still webbed with paths and footways – shadowing the modern-day road network, or meeting it at a slant or perpendicular. Pilgrim paths, green roads, drove roads, corpse roads, trods, leys, dykes, drongs, sarns, snickets – say the names of paths out loud and at speed and they become a poem or rite – holloways, bostles, shutes, driftways, lichways, ridings, halterpaths, cartways, carneys, causeways, herepaths.Many regions still have their old ways, connecting place to place, leading over passes or round mountains, to church or chapel, river or sea. Not all of their histories are happy. In Ireland there are hundreds of miles of famine roads, built by the starv-ing during the 1840s to connect nothing with nothing in return for little, unregistered on Ordnance Survey base maps. In the Netherlands there are doodwegen and spook-wegen – death roads and ghost roads – which converge on medieval cemeteries. Spain has not only a vast and operational network of cañada , or drove roads, but also thousands of miles of the Camino de Santiago, the pilgrim routes that lead to the shrine of Santiago de Compostela. For pilgrims walking the Camino, every footfall is doubled, landing at once on the actual road and also on the path of faith. In Scotland there are clachan and rathad – cairned paths and shieling paths – and in Japan the slender farm tracks that the poet Bashō followed in 1689 when writing his Narrow Road to the Far North . The American prairies were traversed in the nineteenth century by broad ‘bison roads’, made by herds of buffalo moving several beasts abreast, and then used by early settlers as they pushed westwards across the Great Plains.Paths of long usage exist on water as well as on land. The oceans are seamed with seaways – routes whose course is determined by prevailing winds and currents – and rivers are among the oldest ways of all. During the winter months, the only route in and out of the remote valley of Zanskar in the Indian Himalayas is along the ice-path formed by a frozen river. The river passes down through steep-sided valleys of shaley rock, on whose slopes snow leopards hunt. In its deeper pools, the ice is blue and lucid. The journey down the river is called the chadar , and parties undertaking the chadar areRobert Macfarlane 第十届杯翻译竞赛原文(英语组)Pathled by experienced walkers known as ‘ice-pilots’, who can tell where the dangers lie. Different paths have different characteristics, depending on geology and purpose. Certain coffin paths in Cumbria have flat ‘resting stones’ on the uphill side, on which the bearers could place their load, shake out tired arms and roll stiff shoulders; cer-tain coffin paths in the west of Ireland have recessed resting stones, in the alcoves of which each mourner would place a pebble. The prehistoric trackways of the Eng-lish Downs can still be traced because on their close chalky soil, hard-packed by cen-turies of trampling, daisies flourish. Thousands of work paths crease the moorland of the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides, so that when seen from the air the moor has the appearance of chamois leather. I think also of the zigzag flexure of mountain paths in the Scottish Highlands, the flagged and bridged packhorse routes of York-shire and Mid Wales, and the sunken green-sand paths of Hampshire on whose shady banks ferns emerge in spring, curled like crosiers.The way-marking of old paths is an esoteric lore of its own, involving cairns, grey wethers, sarsens, hoarstones, longstones, milestones, cromlechs and other guide-signs. On boggy areas of Dartmoor, fragments of white china clay were placed to show safe paths at twilight, like Hansel and Gretel’s pebble trail. In mountain country, boulders often indicate fording points over rivers: Utsi’s Stone in the Cairn-gorms, for instance, which marks where the Allt Mor burn can be crossed to reach traditional grazing grounds, and onto which has been deftly incised the petroglyph of a reindeer that, when evening sunlight plays over the rock, seems to leap to life. Paths and their markers have long worked on me like lures: drawing my sight up and on and over. The eye is enticed by a path, and the mind’s eye also. The imagina-tion cannot help but pursue a line in the land – onwards in space, but also backwards in time to the histories of a route and its previous followers. As I walk paths I often wonder about their origins, the impulses that have led to their creation, the records they yield of customary journeys, and the secrets they keep of adventures, meetings and departures. I would guess I have walked perhaps 7,000 or 8,000 miles on footpaths so far in my life: more than most, perhaps, but not nearly so many as others. Thomas De Quincey estimated Wordsworth to have walked a total of 175,000–180,000 miles: Wordsworth’s notoriously knobbly legs, ‘pointedly condemned’ – in De Quincey’s catty phrase – ‘by all … female connoisseurs’, were magnificent shanks when it came to passage and bearing. I’ve covered thousands of foot-miles in my memory, because when – as most nights – I find myself insomniac, I send my mind out to re-walk paths I’ve followed, and in this way can sometimes pace myself into sleep.‘They give me joy as I proceed,’ wrote John Clare of field paths, simply. Me too. ‘My left hand hooks you round the waist,’ declared Walt Whitman – companion-ably, erotically, coercively – in Leaves of Grass (1855), ‘my right hand points to landscapes of continents, and a plain public road.’ Footpaths are mundane in the bestForeign Literature and Art159sense of that word: ‘worldly’, open to all. As rights of way determined and sustained by use, they constitute a labyrinth of liberty, a slender network of common land that still threads through our aggressively privatized world of barbed wire and gates, CCTV cameras and ‘No Trespassing’ signs. It is one of the significant differences be-tween land use in Britain and in America that this labyrinth should exist. Americans have long envied the British system of footpaths and the freedoms it offers, as I in turn envy the Scandinavian customary right of Allemansrätten (‘Everyman’s right’). This convention – born of a region that did not pass through centuries of feudalism, and therefore has no inherited deference to a landowning class – allows a citizen to walk anywhere on uncultivated land provided that he or she cause no harm; to light fires; to sleep anywhere beyond the curtilage of a dwelling; to gather flowers, nuts and berries; and to swim in any watercourse (rights to which the newly enlightened access laws of Scotland increasingly approximate).Paths are the habits of a landscape. They are acts of consensual making. It’s hard to create a footpath on your own. The artist Richard Long did it once, treading a dead-straight line into desert sand by turning and turning about dozens of times. But this was a footmark not a footpath: it led nowhere except to its own end, and by walking it Long became a tiger pacing its cage or a swimmer doing lengths. With no promise of extension, his line was to a path what a snapped twig is to a tree. Paths connect. This is their first duty and their chief reason for being. They relate places in a literal sense, and by extension they relate people.Paths are consensual, too, because without common care and common practice they disappear: overgrown by vegetation, ploughed up or built over (though they may persist in the memorious substance of land law). Like sea channels that require regular dredging to stay open, paths need walking. In nineteenth-century Suffolk small sickles called ‘hooks’ were hung on stiles and posts at the start of certain well-used paths: those running between villages, for instance, or byways to parish church-es. A walker would pick up a hook and use it to lop off branches that were starting to impede passage. The hook would then be left at the other end of the path, for a walker coming in the opposite direction. In this manner the path was collectively maintained for general use.By no means all interesting paths are old paths. In every town and city today, cut-ting across parks and waste ground, you’ll see unofficial paths created by walkers who have abandoned the pavements and roads to take short cuts and make asides. Town planners call these improvised routes ‘desire lines’ or ‘desire paths’. In Detroit – where areas of the city are overgrown by vegetation, where tens of thousands of homes have been abandoned, and where few can now afford cars – walkers and cy-clists have created thousands of such elective easements.160。

21世纪CASIO 杯英语演讲比赛

第十届“21世纪CASIO 杯”全国中小学英语演讲比赛

初中组话题:The older I grow, the …(越长大,越……)

题解:小时候我们总是盼望着快快长大,对成长充满着好奇,跨过了天真烂漫的童年时代,现在的你与以前最大的变化是什么?成长带给你最大的感悟是什么?字数要求150---200字。

参赛方式:第一阶段:截止2011年10月28日,稿件按备课组为单位上交到郑丽丽处。

地区初赛:学生以书面演讲稿形式(按附页要求格式写),评委对稿件删选后挑出进入决赛的选手参加决赛。

地区决赛:2011年11月----12月,选手面对评委脱稿对已准备的演讲稿即席演讲,回答评委问题,由评委打分,通过地区决赛进入全国总决赛,代表陕西省参加全国总决赛。

具体事宜见大赛官方网站:http://contest.

演讲稿件格式见附页:

演讲稿件格式

2011.10。

第三届“外教社·CASIO杯”全国中学生英语阅读竞赛全国总决赛上海圆满落幕

第三届“外教社CASIO杯”全国中学生英语阅读竞赛全国总

决赛上海圆满落幕

佚名

【期刊名称】《《高考金刊》》

【年(卷),期】2010(000)010

【摘要】由上海外语教育出版社和课堂内外杂志社共同主办,卡西欧(上海)贸易有限公司协办的第三届“外教社·CASIO杯”全国中学生英语阅读竞赛全国总决赛于2010年7月19日在上海举行。

【总页数】1页(PI0001-I0001)

【正文语种】中文

【中图分类】G633.33

【相关文献】

1.竞赛的季节——服务技能大赛特别专题:提升服务,全速领航——2011一汽-大众奥迪专业双杯竞赛全国总决赛圆满落幕 [J], 晓波

2.第三届“外教社杯”全国大学英语教学大赛江苏赛区决赛圆满落幕 [J], 无

3.2009年“外教社·卡西欧杯”第二届全国中学生英语阅读竞赛 [J], 无

4.竞赛的季节——服务技能大赛特别专题:提升服务,全速领航——2011一汽-大众奥迪专业双杯竞赛全国总决赛圆满落幕 [J], 晓波

5.第三届“外教社·CASIO杯”全国中学生英语阅读竞赛圆满落幕 [J],

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

第八届卡西欧翻译大赛要求

第八届CASIO杯翻译竞赛征文启事由上海翻译家协会和上海译文出版社共同承办,以推进我国翻译事业的繁荣发展,发现和培养翻译新人为宗旨的CASIO杯翻译竞赛,继成功举办了七届之后,已成为翻译界的知名赛事。

今年,本届竞赛特设两个语种——英语和法语。

具体参赛规则如下:一、本届竞赛为英语、法语翻译竞赛。

二、参赛者年龄:45周岁以下。

三、竞赛原文将刊登于2011年第3期(2011年6月出版)的《外国文艺》杂志、上海译文出版社网站及上海翻译家协会网站。

四、本届翻译竞赛评选委员会由各大高校、出版社的专家学者组成。

五、参赛译文必须用电脑打印,寄往:上海市福建中路193号上海译文出版社《外国文艺》编辑部,邮政编码200001。

信封上注明:CASIO杯翻译竞赛。

为了体现评奖的公正性和客观性,译文正文内请勿书写姓名等任何与译者个人身份信息相关的文字或符号,否则译文无效。

请另页写明详尽的个人信息,如姓名、性别、出生年月日、工作学习单位及家庭住址、联系电话、E-MAIL地址等,恕不接受以电子邮件和传真等其他形式发来的参赛稿件,参加评奖的译文恕不退还。

六、参赛译文必须独立完成,合译、抄袭或请他人校订过的译文均属无效。

七、截稿日期为2011年8月10日(以邮寄当日邮戳为准)。

八、为鼓励更多的翻译爱好者参与比赛,提高翻译水平,两个语种的竞赛各设一等奖1名(证书及价值8000元的奖金和奖品),二等奖2名(证书及价值3000元的奖金和奖品),三等奖3名(证书及价值2000元的奖金和奖品),优胜奖20名(证书及价值300元的奖品),此外还设优秀组织奖1名(价值5000元的奖金和奖品)。

各奖项在没有合格译文的情况下将作相应空缺。

获奖证书及奖品务必及时领取,两年内未领者视为自动放弃。

九、《外国文艺》将于2011年第6期(2011年12月出版)公布评选结果并刊登优秀译文,竞赛结果同时在上海译文出版社和上海翻译家协会网站上公布。

十、以上条款的解释权归上海译文出版社所有。

第六届卡西欧翻译大赛english

第六届卡西欧翻译大赛englishMarrying AbsurdJoan DidionTo be married in Las Vegas, Clark County, Nevada, a bride must swear that she is eighteen or has parental permission and a bride-groom that he is twenty-one or has parental permission. Someone must put up five dollars for the license. (On Sundays and holidays, fifteen dollars. The Clark County Courthouse issues marriage licenses at any time of the day or night except between noon and one in the afternoon, between eight and nine in the evening, and between four and five in the morning.) Nothing else is required. The State of Nevada, alone among these United States, demands neither a premarital blood test nor a waiting period before or after the issuance of a marriage license. Driving in across the Mojave from Los Angeles, one sees the signs way out on the desert, looming up from that moonscape of rattlesnakes and mesquite, even before the Las Vegas lights appear like a mirage on the horizon: “GE TTING MARRIED? Free License Information First Strip Exit.” Perhaps the Las Vegas wedding industry achieved its peak operational efficiency between 9:00 p.m. and midnight of August 26,1965, an otherwise unremarkable Thursday which happened to be, by Presidential order, the last day on which anyone could improve his draft status merely by getting married. One hundred and seventy-one couples were pronounced man and wife in the name of Clark County and the State of Nevada that night, sixty-seven of them by a single justice of the peace, Mr. James A. Brennan. Mr. Brennan did one wedding at the Dunes and the other sixty-six in his office, and charged each couple eight dollars. One bride lenther veilto six others. “I got it down from five to three minutes,” Mr.B rennan said later of his feat. “I could’ve married them en masse, but they’re people, not cattle. People expect more when they get married.”What people who get married in Las Vegas actually do expect—what, in the largest sense, their “expectations” are—strikes one as a curious and self—contradictory business. Las Vegas is the most extreme and allegorical of American settlements, bizarre and beautiful in its venality and in its devotion to immediate gratification, a place the tone of which is set by mobster s and call girls and ladies’ room attendants with amyl nitrite poppers in their uniform pockets. Almost everyone notes that there is no “time” in Las Vegas, no night and no day and no past and no future (no Las Vegas casino, however, has taken the obliteration of the ordinary time sense quite so far as Harold’s Club in Reno, which for a while issued, at odd intervals in the day and night, mimeographed “bulletins” carrying news from the world outside); neither is there any logical sense of where one is. One is standing on a highway in the middle of a vast hostile desert looking at an eighty-foot sign which blinks “STARDUST” or “CAESAR’S PALACE.” Yes, but what does that explain? This geographical implausibility reinforces the sense that what happens there has no connection with “real” life; Nevada cities like Reno and Carson are ranch towns, Western towns, places behind which there is some historical imperative. But Las Vegas seems to exist only in the eye of the beholder. All of which makes it an extraordinarily stimulating and interesting place, but an odd one in which to want to wear a candlelight satin Priscilla of Boston wedding dress with Chantilly lace insets,tapered sleeves and a detachable modified train.And yet the Las Vegas wedding business seems to appeal to precisely that impulse. “Sincere and Dignified Since 1954,” one wedding chape l advertises. There are nineteen such wedding chapels in Las Vegas, intensely competitive, each offering better, faster, and, by implication, more sincere services than the next: Our Photos Best Anywhere, Your Wedding on APhonograph Record, Candlelight with Your Ceremony, Honeymoon Accommodations, Free Transportation from Your Motel to Courthouse to Chapel and Return to Motel, Religious or Civil Ceremonies, Dressing Rooms, Flowers, Rings, Announcements, Witnesses Available, and Ample Parking. All of these services, like most others in Las Vegas (sauna baths, payroll-check cashing, chinchilla coats for sale or rent) are offered twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, presumably on the premise that marriage, like craps, is a game to be played when the table seems hot.But what strikes one most about the Strip chapels, with their wishing wells and stained-glass paper windows and their artificial bouvardia, is that so much of their business is by no means a matter of simple convenience, of late-night liaisons between show girls and baby Crosbys. Of course there is some of that. (One night about eleven o’clock in Las Vegas I watched a bride in an orange minidress and masses of flame-colored hair stumble from a Strip chapel on the arm of her bridegroom, who looked the part of the expendable nephew in movies like Miami Syndicate. “I gotta get the kids,” the bride whimpered. “I gotta pick up the sitter, I gotta get to the midn ight show.” “What you gotta get,” the bridegroom said, opening the door of a Cadillac Cou pe de Ville and watching her crumple on the seat, “issober.”) But Las Vegas seems to offer something other than “convenience”; it is merchandising “niceness,” the fa csimile of proper ritual, to children who do not know how else to find it, how to make the arrangements, how to do it “right.” All day and evening long on the Strip, one sees actual wedding parties, waiting under the harsh lights at a crosswalk, standing uneasily in the parking lot of the Frontier while the photographer hired by The Little Chur ch of the West (“Wedding Place of the Stars”) certifies the occasion, takes the picture: the bride in a veil and white satin pumps, the bridegroomusually in a white dinner jacket, and even an attendant or two, a sister or a best friend in hot-pink peau de soie, a flirtation veil, a carnation nosegay. “When I Fall in love It Will Be Forever,” the organist plays, and then a few bars of Lohengrin. The mother cries; the stepfather, awkward in his role, invites the chapel hostess to join them for a drink at the Sands. The hostess declines with a professional smile; she has already transferred her interest to the group waiting outside. One bride out, another in, and again t he sign goes up on the chapel door: “One moment please—Wedding.”I sat next to one such wedding party in a Strip restaurant the last time I was in Las Vegas. The marriage had just taken place; the bride still wore her dress, the mother her corsage. A bored waiter poured out a few swallows of pink champagne (“on the house”) for everyone but the b ride, who was too young to be served. “You’ll need something with more kick than that,” the bride’s father said with heavy jocularity to his new son-in-law; the ritual jokes about the wedding night had a certain Panglossian character, since the bride was clearly several months pregnant. Another round of pink champagne, this time not onthe house, and the bride began to cry. “It was just as nice,” she sobbed, “as I hoped and dreamed it would be.”。

CASIO英语知识对抗赛策划书

CASIO英语知识对抗赛策划书前言:在科技飞速进展的今天,电子词典的更新速度也上升到了一个新的高度。

越来越多的电子词典品牌走进大众的视野。

而随着学生对外语的学习热情越来越大,家长对小孩学习外语的重视也越来越大。

随之而来的是电子词典销售市场的增长。

电子词典的销售人群有专门多,而大学生那个销售点是其中比较重要的一个,不管是从短期效益依旧从长远效益来看大学生那个市场差不多上专门重要的一个销售人群。

因此,在大学生之间做好宣传工作是十分重要的。

活动主题:挑战英语,我有卡西欧活动标语:卡西欧,JUST“读”IT一、活动背景尽管随着学生对学习外语的热情增长而使电子词典的市场增大,但在电子词典品牌日益增多、越来越多的公司想在电子词典上分一杯羹的今天,电子词典的市场竞争也差不多到了白热化的程度。

尽管CASIO通过几年的进展差不多打开了专门大的一部分市场,但想要在众多的电子词典品牌中脱颖而出,在如此猛烈的环境下生存进展,必须让我们的品牌在社会中的认可程度超越其他的品牌。

近几年一些电子词典公司为了使自己的品牌更具有阻碍力,差不多逐步夸大了广告宣传的力度。

而我们CASIO想要加大自己的阻碍力应该采取更加新意的宣传方法,使我们的阻碍力增加到一个新的高度。

二、市场分析1、同电视、报刊传媒相比,在学校宣传有良好的性价比,可用最少的资金做到最好的宣传。

2、学校消费地域集中,针对性强,对电子词典需求量相对较高,产品品牌容易打开市场。

3、方便的活动申请:商家在高校、公寓内搞宣传或促销活动一定要通过一系列的申请,而通过和我们骄阳合作,贵公司能够方便快捷的获得校方批准,同时能得到骄阳各部门的大力协作配合。

4、高效廉价的宣传:以往校内活动中,我们积存了许多的宣传体会,在学校建有强大的宣传网,能够在短时刻内达到专门好的宣传成效。

而且我们骄阳有足够的优秀人才为公司完成宣传活动!5、因为年年都有新生,如条件承诺的话,我们还能够建立一个长期友好合作关系,如每年共同策划一次英语知识对抗赛,将会使CASIO品牌在公寓内外的知名度不断加深,甚至到各个高校,极具有长远意义。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

How Writers Build the Brand By Tony PerrottetAs every author knows, writing a book is the easy part these days. It’s when the publication date looms that we have to roll up our sleeves and tackle the real literary labor: rabid self-promotion. For weeks beforehand, we are compelled to bombard every friend, relative and vague acquaintance with creative e-mails and Facebook alerts, polish up our Web sites with suspiciously youthful author photos, and, in an orgy of blogs, tweets and YouTube trailers, attempt to inform an already inundated world of our every reading, signing, review, interview and (well, one can dream!) TV -appearance. In this era when most writers are expected to do everything but run the printing presses, self-promotion is so accepted that we hardly give it a second thought. And yet, whenever I have a new book about to come out, I have to shake the unpleasant sensation that there is something unseemly about my own clamor for attention. Peddling my work like a Viagra salesman still feels at odds with the high calling of literature. In such moments of doubt, I look to history for reassurance. It’s always comforting to be reminded that literary whoring — I mean, self-marketing — has been practiced by the greats. The most revered of French novelists recognized the need for P.R. “For artists, the great problem to solve is how to get oneself noticed,” Balzac observed in “Lost Illusions,” his classic novel about literary life in early 19th-century Paris. As another master, Stendhal, remarked in his autobiography “Memoirs of an Egotist,” “Great success is not possible without a certain degree of shamelessness, and even of out-and-out charlatanism.” Those words should be on the Authors Guild coat of arms. Hemingway set the modern gold standard for inventive self-branding, burnishing his image with photo ops from safaris, fishing trips and war zones. But he also posed for beer ads. In 1951, Hem endorsed Ballantine Ale in a double-page spread in Life magazine, complete with a shot of him looking manly in his Havana abode. As recounted in “Hemingway and the Mechanism of Fame,” edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli and Judith S. Baughman, he proudly appeared in ads for Pan Am and Parker pens, selling his namewith the abandon permitted to Jennifer Lopez or LeBron James today. Other American writers were evidently inspired. In 1953, John Steinbeck also began shilling for Ballantine, recommending a chilled brew after a hard day’s labor in the fields. Even Vladimir Nabokov had an eye for self-marketing, subtly suggesting to photo editors that they feature him as a lepidopterist prancing about the forests in cap, shorts and long socks. (“Some fascinating photos might be also taken of me, a burly but agile man, stalking a rarity or sweeping it into my net from a flowerhead,” he enthused.) Across the pond, the Bloomsbury set regularly posed for fashion shoots in British Vogue in the 1920s. The frumpy Virginia Woolf even went on a “Pretty Woman”-style shopping expedition at French couture houses in London with the magazine’s fashion editor in 1925. But the tradition of self-promotion predates the camera by millenniums. In 440 B.C. or so, a first-time Greek author named Herodotus paid for his own book tour around the Aegean. His big break came during the Olympic Games, when he stood up in the temple of Zeus and declaimed his “Histories” to the wealthy, influential crowd. In the 12th century, the clergyman Gerald of Wales organized his own book party in Oxford, hoping to appeal to college audiences. According to “The Oxford Book of Oxford,” edited by Jan Morris, he invited scholars to his lodgings, where he plied them with good food and ale for three days, along with long recitations of his golden prose. But they got off easy compared with those invited to the “Funeral Supper” of the 18th-century French bon vivant Grimod de la Reynière, held to promote his opus “Reflections on Pleasure.” The guests’ curiosity turned to horror when they found themselves locked in a candlelit hall with a catafalque for a dining table, and were served an endless meal by black-robed waiters while Grimod insulted them as an audience watched from the balcony. When the diners were finally released at 7 a.m., they spread word that Grimod was mad — and his book quickly went through three -printings. Such pioneering gestures pale, however, before the promotional stunts of the 19th century. In “Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris During the Age of Revolution,” the historian Paul Metzner notes that new technology led to an explosion in the number of newspapers in Paris, creating an array of publicity options. In “Lost Illusions,” Balzac observes that it wasstandard practice in Paris to bribe editors and critics with cash and lavish dinners to secure review space, while the city was plastered with loud posters advertising new releases. In 1887, Guy de Maupassant sent up a hot-air balloon over the Seine with the name of his latest short story, “Le Horla,” painted on its side. In 1884, Maurice Barrès hired men to wear sandwich boards promoting his literary review, Les Taches d’Encre. In 1932, Colette created her own line of cosmetics sold through a Paris store. (This first venture into literary name-licensing was, tragically, a flop). American authors did try to keep up. Walt Whitman notoriously wrote his own anonymous reviews, which would not be out of place today on Amazon. “An American bard at last!” he raved in 1855. “Large, proud, affectionate, eating, drinking and breeding, his costume manly and free, his face sunburnt and bearded.” But nobody could quite match the creativity of the Europeans. Perhaps the most astonishing P.R. stunt — one that must inspire awe among authors today — was plotted in Paris in 1927 by Georges Simenon, the Belgian-born author of the Inspector Maigret novels. For 100,000 francs, the wildly prolific Simenon agreed to write an entire novel while suspended in a glass cage outside the Moulin Rouge nightclub for 72 hours. Members of the public would be invited to choose the novel’s characters, subject matter and title, while Simenon hammered out the pages on a typewriter. A newspaper advertisement promised the result would be “a record novel: record speed, record endurance and, dare we add, record talent!” It was a marketing coup. As Pierre Assouline notes in “Simenon: A Biography,” journalists in Paris “talked of nothing else.” As it happens, Simenon never went through with the glass-cage stunt, because the newspaper financing it went bankrupt. Still, he achieved huge publicity (and got to pocket 25,000 francs of the advance), and the idea took on a life of its own. It was simply too good a story for Parisians to drop. For decades, French journalists would describe the Moulin Rouge event in elaborate detail, as if they had actually attended it. (The British essayist Alain de Botton matched Simenon’s chutzpah, if not quite his glamour, a few years ago when he set up shop in Heathrow for a week and became the airport’s first “writer in residence.” But then he actually got a book out of it, along with prime placement in Heathrow’s bookshops.) What lessons can we draw from all this? Probably none, except that even the mostegregious act of self--promotion will be forgiven in time. So writers today should take heart. We could dress like Lady Gaga and hang from a cage at a Yankees game — if any of us looked as good near-naked, that is. On second thought, maybe there’s a reason we have agents to rein in our P.R. ideas.How Writers Build the Brand By Tony PerrottetAs every author knows, writing a book is the easy part these days. It’s when the publication date looms that we have to roll up our sleeves and tackle the real literary labor: rabid self-promotion. For weeks beforehand, we are compelled to bombard every friend, relative and vague acquaintance with creative e-mails and Facebook alerts, polish up our Web sites with suspiciously youthful author photos, and, in an orgy of blogs, tweets and YouTube trailers, attempt to inform an already inundated world of our every reading, signing, review, interview and (well, one can dream!) TV -appearance. In this era when most writers are expected to do everything but run the printing presses, self-promotion is so accepted that we hardly give it a second thought. And yet, whenever I have a new book about to come out, I have to shake the unpleasant sensation that there is something unseemly about my own clamor for attention. Peddling my work like a Viagra salesman still feels at odds with the high calling of literature.In such moments of doubt, I look to history for reassurance. It’s always comforting to be reminded that literary whoring — I mean, self-marketing — has been practiced by the greats. The most revered of French novelists recognized the need for P.R. “For artists, the great problem to solve is how to get oneself noticed,” Balzac observed in “Lost Illusions,” his classic novel about literary life in early 19th-century Paris. As another master, Stendhal, remarked in his autobiography “Memoirs of an Egotist,” “Great success is not possible without a certain degree of shamelessness, and even of out-and-out charlatanism.” Those words should be on the Authors Guild coat of arms. Hemingway set the modern gold standard for inventive self-branding, burnishing his image with photo ops from safaris, fishing trips and war zones. But he also posed for beer ads. In 1951, Hem endorsed Ballantine Ale in a double-page spread in Life magazine, complete with a shot of him looking manly in his Havana abode. As recounted in “Hemingway and the Mechanism of Fame,” edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli and Judith S. Baughman, he proudly appeared in ads for Pan Am and Parker pens, selling his name with the abandon permitted to Jennifer Lopez or LeBron James today. Other American writers were evidently inspired. In 1953, John Steinbeck also began shilling for Ballantine, recommending a chilled brew after a hard day’s labor in the fields. Even Vladimir Nabokov had an eye for self-marketing, subtly suggesting to photo editors that they feature him as a lepidopterist prancing about the forests in cap, shorts and long socks. (“Some fascinating photos might be also taken of me, a burly but agile man, stalking a rarity or sweeping it into my net from a flowerhead,” he enthused.) Across the pond, the Bloomsbury set regularly posed for fashion shoots in British Vogue in the 1920s. The frumpy Virginia Woolf even went on a “Pretty Woman”-style shopping expedition at French couture houses in London with the magazine’s fashion editor in 1925. But the tradition of self-promotion predates the camera by millenniums. In 440 B.C. or so, a first-time Greek author named Herodotus paid for his own book tour around the Aegean. His big break came during the Olympic Games, when he stood up in the temple of Zeus and declaimed his “Histories” to the wealthy, influential crowd. In the 12th century, the clergyman Gerald of Wales organized his own book party in Oxford, hoping to appeal to college audiences. According to “The Oxford Book ofOxford,” edited by Jan Morris, he invited scholars to his lodgings, where he plied them with good food and ale for three days, along with long recitations of his golden prose. But they got off easy compared with those invited to the “Funeral Supper” of the 18th-century French bon vivant Grimod de la Reynière, held to promote his opus “Reflections on Pleasure.” The guests’ curiosity turned to horror when they found themselves locked in a candlelit hall with a catafalque for a dining table, and were served an endless meal by black-robed waiters while Grimod insulted them as an audience watched from the balcony. When the diners were finally released at 7 a.m., they spread word that Grimod was mad — and his book quickly went through three -printings. Such pioneering gestures pale, however, before the promotional stunts of the 19th century. In “Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris During the Age of Revolution,” the historian Paul Metzner notes that new technology led to an explosion in the number of newspapers in Paris, creating an array of publicity options. In “Lost Illusions,” Balzac observes that it was standard practice in Paris to bribe editors and critics with cash and lavish dinners to secure review space, while the city was plastered with loud posters advertising new releases. In 1887, Guy de Maupassant sent up a hot-air balloon over the Seine with the name of his latest short story, “Le Horla,” painted on its side. In 1884, Maurice Barrès hired men to wear sandwich boards promoting his literary review, Les Taches d’Encre. In 1932, Colette created her own line of cosmetics sold through a Paris store. (This first venture into literary name-licensing was, tragically, a flop). American authors did try to keep up. Walt Whitman notoriously wrote his own anonymous reviews, which would not be out of place today on Amazon. “An American bard at last!” he raved in 1855. “Large, proud, affectionate, eating, drinking and breeding, his costume manly and free, his face sunburnt and bearded.” But nobody could quite match the creativity of the Europeans. Perhaps the most astonishing P.R. stunt — one that must inspire awe among authors today — was plotted in Paris in 1927 by Georges Simenon, the Belgian-born author of the Inspector Maigret novels. For 100,000 francs, the wildly prolific Simenon agreed to write an entire novel while suspended in a glass cage outside the Moulin Rouge nightclub for 72 hours. Members of the public would be invited to choose the novel’s characters, subject matter and title, whileSimenon hammered out the pages on a typewriter. A newspaper advertisement promised the result would be “a record novel: record speed, record endurance and, dare we add, record talent!” It was a marketing coup. As Pierre Assouline notes in “Simenon: A Biography,” journalists in Paris “talked of nothing else.” As it happens, Simenon never went through with the glass-cage stunt, because the newspaper financing it went bankrupt. Still, he achieved huge publicity (and got to pocket 25,000 francs of the advance), and the idea took on a life of its own. It was simply too good a story for Parisians to drop. For decades, French journalists would describe the Moulin Rouge event in elaborate detail, as if they had actually attended it. (The British essayist Alain de Botton matched Simenon’s chutzpah, if not quite his glamour, a few years ago when he set up shop in Heathrow for a week and became the airport’s first “writer in residence.” But then he actually got a book out of it, along with prime placement in Heathrow’s bookshops.) What lessons can we draw from all this? Probably none, except that even the most egregious act of self--promotion will be forgiven in time. So writers today should take heart. We could dress like Lady Gaga and hang from a cage at a Yankees game — if any of us looked as good near-naked, that is. On second thought, maybe there’s a reason we have agents to rein in our P.R. ideas.。