Functional GI Disorders for the Psychiatrist

成人重度抑郁症脑白质微结构的DTI的研究

42·中国CT和MRI杂志 2024年3月 第22卷 第3期 总第173期【通讯作者】侯效芳,女,副主任医师,主要研究方向:中枢神经系统的影像诊断。

E-mail:**************DTI Study on The Microstructure of White·43CHINESE JOURNAL OF CT AND MRI, MAR. 2024, Vol.22, No.3 Total No.173头线圈扫描获取。

采用自旋回波平面成像序列采集DTI数据,扫描参数为:32个扩散方向,b=1000s/mm 2,TR 13 000ms,TE 86.1ms,翻转角度180°,47个相邻轴向切片,3mm厚度,无间隙,成像矩阵128×128,视野256 × 256mm 2。

为探讨MDD患者脑白质结构扩散特征的改变,采用Windows 软件FMRIB Software Library(FSL)。

首先,利用FSL中的脑提取工具算法从DTI数据中去除非脑组织;然后,通过梯度图像与基线b=0图像之间的仿射变换进行头部运动和涡流校正。

然后利用FSL中的dtifit工具计算扩散张量,得到各向异性分数、平均扩散系数、轴向扩散系数和径向扩散系数图。

由于各向异性分数是DTI研究中最广泛使用的,并被用作TBSS研究的惯用指标[13-14],我们在本研究中选择各向异性分数进行后续研究。

所有患者的各向异性分数图谱均与蒙特利尔神经成像研究所(MNI152)模板空间[15]对齐,使用非线性配准工具FNIRT。

使用TBSS pipeles9 (https:///fsl/fslwiki/TBSS)对MDD和健康对照组之间的各向异性分数图进行体素方面的统计分析。

所有患者的MNI空间分数各向异性图谱用于生成平均各向异性分数图谱。

然后,将所有患者的各向异性分数图谱投影到由平均各向异性分数图谱导出的脑组织框架各向异性分数图上,其阈值为0.2。

Functional Esophageal Disorders

Functional Esophageal DisordersJEAN PAUL GALMICHE,*RAY E.CLOUSE,‡ANDRÁS BÁLINT,§IAN J.COOK,ʈPETER J.KAHRILAS,¶WILLIAM G.PATERSON,#and ANDRE J.P.M.SMOUT***University of Nantes,Nantes,France;‡Washington University,St.Louis,Missouri;§Semmelweis University,Budapest,Hungary;ʈUniversity of New South Wales,Sydney,Australia;¶Northwestern University,Chicago,Illinois;#Queen’s University,Kingston,Ontario,Canada;and**University of Utrecht,Utrecht,the NetherlandsFunctional esophageal disorders represent processes accompanied by typical esophageal symptoms(heart-burn,chest pain,dysphagia,globus)that are not ex-plained by structural disorders,histopathology-based motor disturbances,or gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroesophageal reflux disease is the preferred diag-nosis when reflux esophagitis or excessive esophageal acid exposure is present or when symptoms are closely related to acid reflux events or respond to antireflux therapy.A singular,well-defined pathogenetic mecha-nism is unavailable for any of these disorders;combina-tions of sensory and motor abnormalities involving both central and peripheral neural dysfunction have been invoked for some.Treatments remain empirical,al-though the efficacy of several interventions has been established in the case of functional chest pain.Man-agement approaches that modulate central symptom perception or amplification often are required once local provoking factors(eg,noxious esophageal stimuli)have been eliminated.Future research directions include fur-ther determination of fundamental mechanisms respon-sible for symptoms,development of novel management strategies,and definition of the most cost-effective di-agnostic and treatment approaches.F unctional esophageal disorders represent chronicsymptoms typifying esophageal disease that have no readily identified structural or metabolic basis(Table1). Although mechanisms responsible for the disorders re-main poorly understood,a combination of physiologic and psychosocial factors likely contributes toward pro-voking and escalating symptoms to a clinically signifi-cant level.Several diagnostic requirements are uniform across the disorders:(1)exclusion of structural or meta-bolic disorders potentially responsible for symptoms is essential;(2)an arbitrary requirement of at least3 months of symptoms with onset at least6months before diagnosis is applied to each diagnosis to establish some degree of chronicity;(3)gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)must be excluded as an explanation for symp-toms;and(4)a motor disorder of the types with known histopathologic bases(eg,achalasia,scleroderma esopha-gus)must not be the primary symptom source.An important modification in threshold for the third uniform criterion has occurred in this reevaluation of the functional esophageal disorders.1Satisfactory evidence of a symptom relationship with acid reflux events,either by analytical determination from an ambulatory pH study or through subjective outcome from therapeutic antire-flux trials,even in the absence of objective GERD evi-dence,now is sufficient to incriminate GERD(Figure1). The purpose of this modification is to preferentially diagnose GERD over a functional disorder in the initial evaluation so that effective GERD treatments are not overlooked in management.Consequently,the acid-sen-sitive esophagus is now excluded from the group of functional esophageal disorders and considered within the realm of GERD,even if physiologic data indicate that hypersensitivity of the esophagus in this setting can encompass stimuli other than acid.Presumably symp-toms that persist despite GERD interventions or that are out of proportion to the GERDfindings ultimately would be reconsidered toward a functional diagnosis. The role of weakly acidic reflux events(reflux events with pH values between4and7)remains unclear,and tech-nological advances(eg,applications of multichannel in-traluminal impedance monitoring)are expected to fur-ther define the small proportion with functional heartburn truly meeting all stated criteria.2 Abbreviations used in this paper:GERD,gastroesophageal refluxdisease;PPI,proton pump inhibitor.©2006by the American Gastroenterological Association Institute0016-5085/06/$32.00doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.08.060Table1.Functional Gastrointestinal DisordersA.Functional esophageal disordersA1.Functional heartburnA2.Functional chest pain of presumed esophageal originA3.Functional dysphagiaA4.GlobusGASTROENTEROLOGY2006;130:1459–1465A1.Functional HeartburnDefinitionRetrosternal burning in the absence of GERD that meets other essential criteria for the functional esophageal disorders typifies this diagnosis.Constraints in the ability to fully recognize the presence or impor-tance of GERD in individual subjects likely result in a heterogeneous subject group.1EpidemiologyHeartburn is reported by20%–40%of subjects in Western populations,depending on thresholds for a positive response.Studies using both endoscopy and ambulatory pH monitoring to objectively establish evi-dence of GERD indicate that functional heartburn rep-resentsϽ10%of patients with heartburn presenting to gastroenterologists.3The proportion may be higher in primary care settings.A1.Diagnostic Criteria*for FunctionalHeartburnMust include all of the following:1.Burning retrosternal discomfort or pain2.Absence of evidence that gastroesophagealacid reflux is the cause of the symptom3.Absence of histopathology-based esophagealmotility disorders*Criteria fulfilled for the last3months with symptom onset at least6months before diagnosis.Justification for Change in DiagnosticCriteriaThe threshold for the second criterion has been revised to exclude patients with normal esophageal acid exposure yet acid-related symptom events on ambulatory pH monitoring or symptomatic response to antireflux therapy.This group resembles other patients with GERD in terms of presentation,manometricfindings, impact on quality of life,and natural history.Outcome is less satisfactory with antireflux therapy,however,and some subjects within this group will be shown to have functional symptoms that persist once their relationship to reflux events is eliminated with therapy.4Two or more days weekly of mild heartburn is sufficient in GERD to influence quality of life,but thresholds for symptom frequency or severity have not been determined for func-tional heartburn.5Clinical EvaluationClarification of the nature of the symptom is an essentialfirst step to avoid overlooking extraesophageal symptom sources.Additional evaluation primarily is ori-ented toward establishing or excluding the presence of GERD.6,7Endoscopy that reveals no evidence of esoph-agitis is insufficient in this regard,especially in those subjects who are evaluated while remaining on or shortly after discontinuing antireflux therapy.Ambulatory pH monitoring can better classify patients who have normal findings on endoscopic evaluation,including those whose symptoms persist despite therapy.A favorable response to a brief therapeutic trial using high dosages of a proton pump inhibitor(PPI)is not specific,8but lack of response probably has a high negative predictive value for GERD.Physiologic FeaturesMuch of the available literature is clouded by inclusion of subjects with undetected GERD in pa-tient groups with presumed functional heartburn.Theprevailing view is to consider disturbed visceral per-ception as a major factor involved in pathogenesis.9 Enhanced sensitivity to refluxate having slight pH alterations from normal may be responsible in some instances.The focus has remained on intraluminal noxious stimulation;little direct evidence for alter-ation in central signal processing is available in these subjects with heartburn,although it is suspected. Figure1.Further classification of patients with heartburn and no evidence of esophagitis at endoscopy using ambulatory pH monitoring and response to a therapeutic trial of PPIs.The subset with functional heartburn has nofindings that would support a presumptive diagnosis of endoscopy-negative reflux disease(ENRD).The precise thresholds for separation of subjects at each step remain uncertain.Thisfigure shows classification categories byfindings and is not meant to sug-gest a diagnostic management algorithm for use in clinical practice.1460GALMICHE ET AL GASTROENTEROLOGY Vol.130,No.5Psychological FeaturesAcute experimental stress enhances perception of esophageal acid in patients with GERD without promoting reflux events.10Enhanced perception is in-fluenced by the psychological status of the patient. Thus,psychological factors may participate in heart-burn reporting when evidence of a noxious esophageal stimulus is limited.Psychological profiles do not dif-ferentiate subjects with normal esophageal acid expo-sure and no esophagitis from those with elevated acid exposure times,but patients whose heartburn does not correlate well with acid reflux events on an ambulatory pH study do demonstrate greater anxiety and somati-zation scores as well as poor social support than those with reflux-provoked symptoms.11TreatmentPersisting symptoms unrelated to GERD may respond to low-dose tricyclic antidepressants,other antidepressants,or psychological therapies used in many functional syndromes,although controlled trials demonstrating efficacy are unavailable.Reduction in transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations with agents such as baclofen is being investigated.12Anti-reflux surgery in patients with functional heartburn and non–acid reflux events has not been fully evalu-ated,but surgical management would not be expected to be as beneficial as in GERD considering known outcome predictors for these operations.A2.Functional Chest Pain ofPresumed Esophageal OriginDefinitionThis disorder is characterized by episodes of un-explained chest pain that usually are midline in location and of visceral quality and therefore potentially of esoph-ageal origin.The pain easily is confused with cardiac angina and pain from other esophageal disorders,includ-ing achalasia and GERD.EpidemiologyInferential data extracted from cardiac evalua-tions for chest pain indicate that this is a common disorder.Findings on15%–30%of coronary angio-grams performed in patients with chest pain are nor-mal.13Although once considered a diagnosis of elderly women,chest pain without specific explanation was reported twice as commonly by subjects15–34years of age than by subjects older than45years of age in a householders survey,and the sexes were equally represented.14A2.Diagnostic Criteria*for FunctionalChest Pain of Presumed EsophagealOriginMust include all of the following:1.Midline chest pain or discomfort that is not ofburning quality2.Absence of evidence that gastroesophageal re-flux is the cause of the symptom3.Absence of histopathology-based esophagealmotility disorders*Criteria fulfilled for the last3months with symptom onset at least6months before diagnosisJustification for Change in DiagnosticCriteriaAs for other functional esophageal disorders,pain episodes linked to reflux events are now considered to fall within the spectrum of symptomatic GERD.Clinical EvaluationExclusion of cardiac disease is of pivotal impor-tance.Likewise,identification of GERD as the cause of the symptom is essential for diagnostic categorization and management.Exclusion of GERD cannot rely on endoscopy alone,because esophagitis is found inϽ20% of patients with unexplained chest pain.15Ambulatory pH monitoring plays a useful role,and determining the statistical relationship between symptoms and reflux events is the most sensitive approach.16,17When com-bining subjects with and without abnormal acid expo-sure,40%of patients with normalfindings on coronary angiograms may have acid-related pain.1A brief thera-peutic trial with a high-dose PPI regimen is a rapid way of determining clinically relevant reflux-symptom asso-ciations and is recommended for its simplicity and cost-effectiveness.18The diagnostic accuracy remains uncer-tain.Other diagnostic studies,including esophageal manometry,have a limited yield when chest pain is the sole symptom.Physiologic FeaturesAbnormalities have been detected in3categories: sensory abnormalities,distorted central signal process-ing,and abnormal esophageal motility.Motility abnor-malities,particularly spastic motor disorders,are con-spicuous,but their primary role in production of chestApril2006FUNCTIONAL ESOPHAGEAL DISORDERS1461pain is not well established.The relationship of recently observed sustained contraction of longitudinal muscle to pain is being studied.Enhanced sensitivity to intralumi-nal stimuli,including acid and esophageal distention, may be a primary abnormality.Patients with chest pain can be completely segregated from control subjects by pressure thresholds using impedance planimetry.19How subjects with functional chest pain reach the hypersen-sitivity state is not clear.Intermittent stimulation by physiologic acid reflux or spontaneous distention events with swallowing or belching may be relevant.Recent studies also verify alterations in central nervous system processing of afferent signals.A variety of investigational paradigms involving sensory decision theory,electrical stimulation and cortical evoked potentials,and heart rate variability indicate that chest pain reproduced by local esophageal stimulation is accompanied by errors in cen-tral signal processing and an autonomic response.20–22In acid-sensitive subjects,thefindings are further provoked by acid instillation.Psychological FeaturesPsychological factors appear relevant in functional chest pain,with their role potentially being complex. Psychiatric diagnoses,particularly anxiety disorders,de-pression,and somatization disorder,are overrepresented in patients with chronic chest pain.23These disorders have not segregated well with specific physiologicfind-ings,suggesting that they may interact toward produc-ing the symptomatic state,possibly by mediating symp-tom severity and health care utilization.24Psychological factors also influence well-being,functioning,and qual-ity of life,which are important outcomes in an otherwise nonmorbid disease.TreatmentSystematic management is recommended,because continued pain is associated with impaired functional status and increased health care utilization and sponta-neous recovery is rare.Exclusionary evaluation including a therapeutic trial for GERD is indicated.Once the exclusionary evaluation is completed,management op-tions for functional chest pain become limited.Smooth muscle relaxants are ineffective in controlled trials.In-jection of botulinum toxin into the lower esophageal sphincter and esophageal body has had anecdotal use.25,26 The most encouraging outcomes come from antidepres-sant and psychological/behavioral interventions.27,28Ef-ficacy is demonstrated in controlled trials for both tricy-clic antidepressants and more contemporary agents(eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors).29,30Benefits have not been dependent on the presence of any particular physiologic or psychological characteristic.Interest in a psychological intervention is reported by the majority of patients who are asked,particularly when activity limi-tation and pain intensity or frequency are high.A3.Functional DysphagiaDefinitionThe disorder is characterized by a sensation of abnormal bolus transit through the esophageal body. Thorough exclusion of structural lesions,GERD,and histopathology-based esophageal motor disorders is re-quired for establishing the diagnosis.EpidemiologyLittle information is available regarding the prev-alence of functional dysphagia,largely because of the degree of exclusionary evaluation required.Between7% and8%of respondents from a householders survey re-ported dysphagia that was unexplained by questionnaire-ascertained disorders.14Less than1%report frequent dysphagia.Functional dysphagia is the least prevalent of these functional esophageal disorders.A3.Diagnostic Criteria*for FunctionalDysphagiaMust include all of the following:1.Sense of solid and/or liquid foods sticking,lodging,or passing abnormally through theesophagus2.Absence of evidence that gastroesophageal re-flux is the cause of the symptom3.Absence of histopathology-based esophagealmotility disorders*Criteria fulfilled for the last3months with symptom onset at least6months before diagnosisJustification for Change in DiagnosticCriteriaDysphagia is not easily linked to reflux events. Nevertheless,the modification of the threshold used for the second criterion(see the introduction)would at-tribute the symptom to GERD rather than a functional diagnosis if the link were established,even in the absence of other objective GERD indicators.Clinical EvaluationFastidious exclusion of structural disorders is re-quired initially.31Endoscopy and esophageal barium ra-1462GALMICHE ET AL GASTROENTEROLOGY Vol.130,No.5diography are necessary to exclude intrinsic and extrinsic lesions,with radiographic studies being augmented with radio-opaque bolus challenge duringfluoroscopy if re-quired.32Biopsies at the time of endoscopy are recom-mended for excluding eosinophilic esophagitis.Esopha-geal manometry,primarily for detection of achalasia,is recommended if endoscopy and barium radiography fail to provide a specific diagnosis.Ambulatory pH monitor-ing plays a small role but may be helpful in patients whose dysphagia is associated with heartburn or regur-gitation,but a brief therapeutic trial with a high-dose PPI regimen usually is satisfactory for identifying pa-tients with subtle GERD as a cause for dysphagia.33 Physiologic FeaturesMechanisms responsible for this disorder are poorly understood.Peristaltic dysfunction may be re-sponsible in some subjects.Rapid propagation velocity is accompanied by poor barium clearance that may be perceived as dysphagia.34Likewise,failed or low-ampli-tude contraction sequences impair esophageal emptying and can result in dysphagia.35Dysphagia also can be induced by intraluminal acid and balloon distention, suggesting that abnormal esophageal sensory perception may be a factor in some subjects.36Psychological FeaturesAcute stress experiments suggest that central fac-tors can precipitate motor abnormalities potentially re-sponsible for dysphagia.1Barium transit is adversely altered in asymptomatic and symptomatic subjects dur-ing recollection of unpleasant topics or stressful,unpleas-ant interviews.Noxious auditory stimuli or difficult cognitive tasks alter manometric recordings by increas-ing contraction wave amplitude and occasionally induc-ing simultaneous contraction sequences.The relevance of thesefindings to functional dysphagia remains conjec-tural.TreatmentManagement includes reassurance,avoidance of precipitating factors,careful mastication of food,and modification of any psychological abnormality that seems directly relevant to symptom production.Symptom modulation with antidepressants and psychological ther-apies can be attempted,considering their effects in other disorders.Empirical dilation may be indicated.32Smooth muscle relaxants,botulinum toxin injection,or even pneumatic dilation can be useful in some patients with spastic disorders,particularly if incomplete lower esoph-ageal sphincter relaxation and delay of distal esophageal emptying on barium radiography are evident.A4.GlobusDefinitionGlobus is defined as a sense of a lump,a retained food bolus,or tightness in the throat.The symptom is nonpainful,frequently improves with eating,commonly is episodic,and is unassociated with dysphagia or odynophagia.Globus is unexplained by structural le-sions,GERD,or histopathology-based esophageal motil-ity disorders.EpidemiologyGlobus is a common symptom and is reported by up to46%of apparently healthy individuals,with a peak incidence in middle age.14It is uncommon in subjects younger than20years of age.The symptom is equally prevalent in men and women among healthy individuals in the community,but women are more likely to seek health care for this symptom.37A4.Diagnostic Criteria*for GlobusMust include all of the following:1.Persistent or intermittent,nonpainful sensa-tion of a lump or foreign body in the throat2.Occurrence of the sensation between meals3.Absence of dysphagia or odynophagia4.Absence of evidence that gastroesophageal re-flux is the cause of the symptom5.Absence of histopathology-based esophagealmotility disorders*Criteria fulfilled for the last3months with symptom onset at least6months before diagnosisJustification for Change in DiagnosticCriteriaBy factor analysis,globus is distinct from pain, and pain often is indicative of a local structural disor-der.38As for other functional esophageal disorders,dem-onstration that the symptom is directly related to reflux events would indicate a diagnosis of GERD,even in the absence of other objective evidence of GERD.Clinical EvaluationThe diagnosis is made from a compatible clinical history,including clarification that dysphagia is absent. Physical examination of the neck followed by nasolaryn-goscopic examination of the pharynx and larynx are advised,although routine use of nasolaryngoscopy in patients with typical symptoms remains debated.Fur-April2006FUNCTIONAL ESOPHAGEAL DISORDERS1463ther investigation of the simple symptom is not well supported;dysphagia,odynophagia,pain,weight loss, hoarseness,or other alarm symptoms mandate more ex-tensive evaluation.There are grounds for a therapeutic trial of a PPI when uninvestigated patients present with the symptom of globus,particularly when typical reflux symptoms coexist.Physiologic FeaturesConsistent evidence is lacking to attribute globus to any specific anatomic abnormality,including the cri-copharyngeal bar.Upper esophageal sphincter mechanics do not seem relevant,and the pharyngeal swallow mech-anism is normal.Urge to swallow and increased swallow frequency might contribute to the symptom by period-ically causing air entrapment in the proximal esophagus. Esophageal balloon distention can reproduce globus sen-sation at low distending thresholds,suggesting some degree of esophageal hypersensitivity.39Likewise,globus is more common in conjunction with reflux symptoms, although a strong relationship between GERD and glo-bus has not been established.40Additionally,the symp-tom does not respond well to antireflux therapy.Al-though gastroesophageal reflux and distal esophageal motility disorders can include globus in their presenta-tions,these mechanisms are believed to play a minimal role in the pathophysiology of globus.Psychological FeaturesNo specific psychological characteristic has been identified in subjects with globus.Psychiatric diagnoses are prevalent in subjects seeking health care,but an explanation distinct from ascertainment bias has not been established.Increased reporting of stressful life events preceding symptom onset has been observed in several studies,suggesting that life stress might be a cofactor in symptom genesis or exacerbation.41Up to 96%of subjects with globus report symptom exacerba-tion during periods of high emotional intensity.42 TreatmentGiven the benign nature of the condition,the likelihood of long-term symptom persistence,and the absence of highly effective pharmacotherapy,the main-stay of treatment rests with explanation and reassurance. Expectations for prompt symptom resolution are low, because symptoms persist in up to75%of patients at3 years.43Controlled trials of antidepressants for globus are unavailable,but there is some anecdotal evidence for their utility.44Recommendations for FutureResearchDespite their high prevalence rates,functional esophageal disorders have not been well studied.In par-ticular,highly effective management approaches have not been established.Several areas requiring additional research were identified.1.Studies validating the diagnostic criteria are needed,and a method for improving the accuracy of symp-tom-based criteria while limiting exclusionary workup would be welcomed.2.The fundamental mechanisms of symptom produc-tion remain poorly defined.Further application of new technologies for measuring reflux events,motor physiology,and esophageal sensation as well as cen-tral signal modulation is recommended(eg,mul-tichannel intraluminal impedance monitoring,high-resolution manometry).3.Well-structured,controlled treatment trials would bewelcomed in any of these disorders,because manage-ment remains highly empirical.4.Treatment trials should include measures of quality oflife and functional outcome when determining both short-term and long-term effects.The impact of in-terventions on functional impairment and health care resource use,important indicators of morbidity from the functional esophageal disorders,should be a focus in measuring treatment success.References1.Functional esophageal disorders.In:Drossman DA,Corazziari E,Delvaux M,Spiller R,Talley NJ,Thompson WG,Whitehead WE, eds.Rome III.The functional gastrointestinal disorders.3rd ed.McLean,VA:Degnon Associates(in press).2.Sifrim D.Acid,weakly acidic and non-acid gastroesophageal re-flux:differences,prevalence and clinical relevance.Eur J Gastro-enterol Hepatol2004;16:823–830.3.Martinez SD,Malagon IB,Garewal HS,Cui H,Fass R.Non-erosivereflux disease(NERD)—acid reflux and symptom patterns.Ali-ment Pharmacol Ther2003;17:537–545.4.Watson RGP,Tham TCK,Johnston BT,McDougall NI.Doubleblind cross-over placebo controlled study of omeprazole in the treatment of patients with reflux symptoms and physiological levels of acid reflux—the“sensitive esophagus.”Gut1997;40: 587–590.5.Dent J,Armstrong D,Delanye B,Moayyedi P,Talley NJ,Vakil N.Symptom evaluation in reflux disease:workshop,background, process,terminology,recommendations,and discussion out-puts.Gut2004;53(Suppl IV):iv1–iv24.6.Dent J,Brun J,Fendrick M,Fennerty MB,Janssens J,Kahrilas PJ,Lauritsen K,Reynolds JC,Shaw M,Talley NF,Genval Workshop Group.An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease manage-ment—The Genval Workshop Report.Gut1999;44(Suppl2):S1–S16.7.French-Belgian Consensus Conference on Adult Gastro-Oesopha-geal Reflux Disease“Diagnosis and Treatment.”Eur J Gastroen-terol Hepatol2000;12:129–137.1464GALMICHE ET AL GASTROENTEROLOGY Vol.130,No.58.Numans ME,Lau J,de Wit NJ,Bonis PA.Short-term treatmentwith proton-pump inhibitors as a test for gastroesophageal reflux disease:a meta-analysis of diagnostic test characteristics.Ann Intern Med2004;140:518–527.9.Fass R,Tougas G.Functional heartburn:the stimulus,the pain,and the brain.Gut2002;51:885–892.10.Bradley LA,Richter JE,Pulliam TJ,McDonald-Haile J,Scarinci IC,Schan CA,Dalton CB,Salley AN.The relationship between stress and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux:the influence of psy-chological factors.Am J Gastroenterol1993;88:11–19.11.Johnston BT,Lewis SA,Collins JS,McFarland RJ,Love AH.Acidperception in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is dependent on psychosocial factors.Scand J Gastroenterol1995;30:1–5. 12.Koek GH,Sifrim D,Lerut T,Janssens J,Tack J.Effect of theGABA(B)agonist baclofen in patients with symptoms and duo-deno-gastro-oesophageal reflux refractory to proton pump inhibi-tors.Gut2003;52:1397–1402.13.Kemp HG,Vokonas PS,Cohn PF,Gorlin R.The anginal syndromeassociated with normal coronary arteriograms.Report of a six year experience.Am J Med1973;54:735–742.14.Drossman DA,Li Z,Andruzzi E,Temple RD,Talley NJ,ThompsonJG,Whitehead WE,Janssens J,Funch-Jensen P,Corazziari E, Richter JE,Koch GG.U.S.householders survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders.Prevalence,sociodemography and health impact.Dig Dis Sci1993;38:1569–1580.15.Kahrilas PJ,Quigley EM.Clinical esophageal pH recording:atechnical review for practice guideline development.Gastroenter-ology1996;110:1982–1996.16.Wiener GJ,Richter JE,Copper JB,Wu WC,Castell DO.Thesymptom index:a clinically important parameter of ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring.Am J Gastroenterol1988;83:358–361.17.Prakash C,Clouse RE.Value of extended recording time withwireless esophageal pH monitoring in evaluating gastroesopha-geal reflux disease.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol2005;3:329–334.18.Fass R,Fennerty MB,Ofman JJ,Gralnek IM,Johnson C,CamargoE,Sampliner RE.The clinical and economic value of a short course of omeprazole in patients with noncardiac chest pain.Gastroenterology1998;115:42–49.19.Rao SSC,Gregersen H,Hayek B,Summers RW,Christensen J.Unexplained chest pain:the hypersensitive,hyperactive,and poorly compliant esophagus.Ann Intern Med1996;124:950–958.20.Bradley LA,Scarinci IC,Richter JE.Pain threshold levels andcoping strategies among patients who have chest pain and nor-mal coronary arteries.Med Clin North Am1991;75:1189–202.21.Hollerbach S,Bulat R,May A,Kamath MV,Upton AR,Fallen EL,Tougas G.Abnormal cerebral processing of oesophageal stimuli in patients with noncardiac chest pain(NCCP).Neurogastroen-terol Motil2000;12:555–565.22.Tougas G,Spaziani R,Hollerbach S,Djuric V,Pang C,Upton AR,Fallen EL,Kamath MV.Cardiac autonomic function and oesoph-ageal acid sensitivity in patients with non-cardiac chest pain.Gut 2001;49:706–712.23.Clouse RE,Carney RM.The psychological profile of non-cardiacchest pain patients.Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol1995;7:1160–1165.24.Song CW,Lee SJ,Jeen YT,Chun HJ,Um SH,Kim CD,Ryu HS,Hyun JH,Lee MS,Kahrilas PJ.Inconsistent association of esoph-ageal symptoms,psychometric abnormalities and dysmotility.Am J Gastroenterol2001;96:2312–2316.ler LS,Pullela SV,Parkman HP,Schiano TD,Cassidy MJ,CohenS,Fisher RS.Treatment of chest pain in patients with noncardiac, nonreflux,nonachalasia spastic esophageal motor disorders usingbotulinum toxin injection into the gastroesophageal junction.Am J Gastroenterol2002;97:1640–1646.26.Storr M,Allescher HD,Rosch T,Born P,Weigert N,Classen M.Treatment of symptomatic diffuse esophageal spasm by endo-scopic injections of botulinum toxin:a prospective study with long term follow-up.Gastrointest Endosc2001;54:754–759.27.Eslick GD,Fass R.Noncardiac chest pain:evaluation and treat-ment.Gastroenterol Clin North Am2003;32:531–552.28.Peski-Oosterbaan AS,Spinhoven P,van Rood Y,van der DoesJW,Bruschke AV,Rooijmans HG.Cognitive-behavioral therapy for noncardiac chest pain:a randomized trial.Am J Med1999;106: 424–429.29.Clouse RE.Antidepressants for functional gastrointestinal syn-dromes.Dig Dis Sci1994;39:2352–2363.30.Varia I,Logue E,O’connor C,Newby K,Wagner HR,Davenport C,Rathey K,Krishnan KR.Randomized trial of sertraline in patients with unexplained chest pain of noncardiac origin.Am Heart J 2000;140:367–372.31.Lind CD.Dysphagia:evaluation and treatment.Gastroenterol ClinNorth Am2003;32:553–575.32.Clouse RE.Approach to the patient with dysphagia or odynopha-gia.In:Yamada T,Alpers DH,Kaplowitz N,Laine L,Owyang C, Powell DW(eds).Textbook of gastroenterology.4th ed.Philadel-phia,PA:Lippincott Williams&Wilkins,2003:678–691.33.Vakil NB,Traxler B,Levine D.Dysphagia in patients with erosiveesophagitis:prevalence,severity,and response to proton pump inhibitor treatment.Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol2004;2:665–668.34.Hewson EG,Ott DJ,Dalton CB,Chen YM,Wu WC,Richter JE.Manometry and plementary studies in the assess-ment of esophageal motility disorders.Gastroenterology1990;98:626–632.35.Jacob P,Kahrilas PJ,Vanagunas A.Peristaltic dysfunction asso-ciated with nonobstructive dysphagia in reflux disease.Dig Dis Sci1990;35:939–942.36.Deschner WK,Maher KA,Cattau E,Benjamin SB.Manometricresponses to balloon distention in patients with nonobstructive dysphagia.Gastroenterology1989;97:1181–1185.37.Batch AJG.Globus pharyngeus(part I).J Laryngol Otol1988;102:152–158.38.Deary IJ,Wilson JA,Harris MB,MacDougall G.Globus pharyngis:development of a symptom assessment scale.J Psychosom Res 1995;39:203–213.39.Cook I,Shaker R,Dodds W,Hogan W,Arndorfer R.Role ofmechanical and chemical stimulation of the esophagus in globus sensation(abstr).Gastroenterology1989;96:–A99.40.Wilson J,Heading R,Maran A,Pryde A,Piris J,Allan P.Globussensation is not due to gastro-oesophageal reflux.Clin Otolaryn-gol1987;12:271–275.41.Harris MB,Deary IJ,Wilson JA.Life events and difficulties inrelation to the onset of globus pharyngis.J Psychosom Res 1996;40:603–615.42.Thompson WG,Heaton KW.Heartburn and globus in apparentlyhealthy people.Can Med Assoc J1982;126:46–48.43.Timon C,O’Dwyer T,Cagney D,Walsh M.Globus pharyngeus:long-term follow-up and prognostic factors.Ann Otol Rhinol Lar-yngol1991;100:351–354.44.Brown SR,Schwartz JM,Summergrad P,Jenike MA.Globushystericus syndrome responsive to antidepressants.Am J Psy-chiatry1986;143:917–918.Received January31,2005.Accepted August31,2005.Address requests for reprints to:Ray E.Clouse,MD,Division of Gastroenterology,Washington University School of Medicine,660 South Euclid Avenue,Campus Box8124,St Louis,Missouri63110. e-mail:rclouse@;fax:(314)454-5107.April2006FUNCTIONAL ESOPHAGEAL DISORDERS1465。

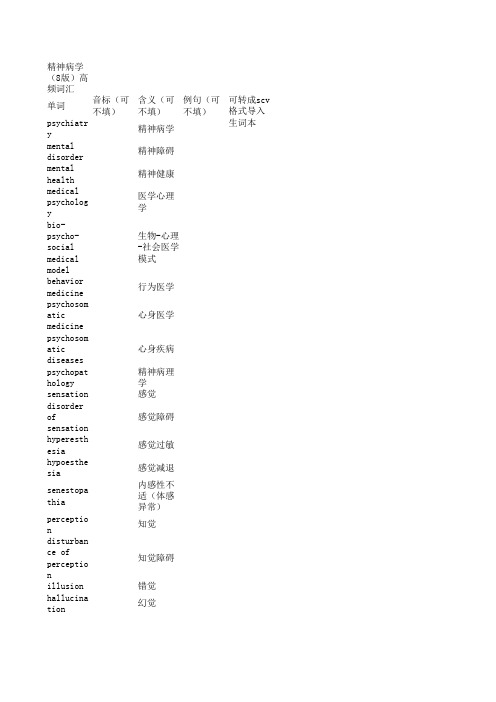

精神病学高频英语词汇(医学英语)

(8版)高频词汇单词音标(可不填)含义(可不填)例句(可不填)psychiatry精神病学mentaldisorder精神障碍mentalhealth精神健康medical psycholog y 医学心理学bio-psycho-social medical model 生物-心理-社会医学模式behaviormedicine行为医学psychosomaticmedicine心身医学psychosomaticdiseases心身疾病psychopat hology 精神病理学sensation感觉disorderofsensation感觉障碍hyperesthesia感觉过敏hypoesthesia感觉减退senestopa thia 内感性不适(体感异常)perception知觉disturbance ofperception知觉障碍illusion错觉hallucina tion 幻觉可转成scv格式导入生词本hallucination幻听visualhallucination幻视olfactoryhallucination幻嗅gustatoryhallucination幻味tactilehallucination幻触visceralhallucination内脏幻觉genuinehallucination真性幻觉pseudo-hallucination假性幻觉functional hallucina tion 机能性幻觉reflex hallucina tion 反射性幻觉hypnagogic hallucina tion 入睡前幻觉psychogenic hallucina tion 心因性幻觉psychosensory disturban ce 感知综合障碍metamorph opsia 视物变形症macropsia 视物显大症micropsia 视物显小症thinking思维thinkingdisorder思维障碍disorderof the thinking form 思维形式障碍flight ofthought思维奔逸inhibition ofthought思维迟缓povertyofthought思维贫乏loosenessofthought思维散漫splittingofthought思维破裂wordsalad词的杂拌incoheren ce of thought 思危不连贯circumsta ntiality 病理性赘述blockingofthought思维中断thoughtinsertion思维插入forced thinking 强制性思维thoughthearing思维化声diffusionofthought思维扩散thought broadcast ing 思维被广播symbolic thinking 象征性思维neologism词语新作paralogis mthinking 逻辑倒错性思维obsessiveidea强迫观念delusion妄想primarydelusion原发妄想secondarydelusion继发妄想delusionofpersecutiondelusionofreferencedelusionofphysicalinfluencegrandiosedelusion被害妄想delusionof guilty关系妄想delusionof physical influence 物理影响妄想grandiosedelusion夸大妄想delusionof guilty罪恶妄想hypochondriacaldelusion疑病妄想delusionof love钟情妄想delusionofjealousy嫉妒妄想experienc e of being revealed 被洞悉感(内心被揭露感)overvalued idea超价观念attention注意disorderofattention注意障碍hyperprosexia注意增强aprosexia注意涣散hypoprosexia注意减退transference ofattention注意转移narrowingofattention注意狭窄memory记忆disorderof memory记忆障碍hypermnesia记忆增强hypomnesia记忆减退amnesia遗忘anterogra de amnesia 顺行性遗忘retrograd e amnesia 逆行性遗忘circumscr ibed amnesia 界限性遗忘paramnesia错构confabulation虚构intelligence智能mental retardati on 精神发育迟滞dementia痴呆pseudodementia假性痴呆Ganser syndrome 刚塞综合症puerilism童样痴呆depressive pseudodem entia 抑郁性假性痴呆orientation定向力disorientation定向障碍affect情感emotion情绪mood心境elation情感高涨depression情感低落anxiety焦虑phobia恐惧apathy情感淡漠irritability易激惹性labileaffect情感不稳parathymia情感倒错will意志disorderof will意志障碍hyperbulia意志增强hypobulia意志减弱abulia意志缺乏hesitant犹豫不决psychomotor excitemen t 精神运动性兴奋psychomotor inhibitio n 精神运动性抑制stupor木僵cereaflexibility蜡样屈曲mutism缄默症negativism违拗症active negativis m 主动性违拗passive negativis m 被动性违拗stereotyped act刻板动作echopraxia模仿动作mannerism作态consciousness意识drowsiness嗜睡confusion意识浑浊sopor昏睡coma昏迷twilightstate朦胧状态delirium谵妄状态oneiroidstate梦样状态insight自知力interview面谈检查acute brain syndrome 急性脑病综合症chronic brain syndrome 慢性脑病综合症amnesia syndrome 遗忘综合症Korsakov ’s syndrome 柯萨可夫综合症Alzheimer’s disease AD阿尔茨默病presenile dementia 早老性痴呆dementia praecox 早发性痴呆senileplaqueSP老年斑neurofibrillary tangles NFT神经元纤维缠结vascular dementia VD血管性痴呆multi-infarct dementia MID多发性梗塞性痴呆multi-infarctdementiaMIDpost-traumatic confusion al state 外伤性精神混乱状态post-traumatic amnesia PTA脑外伤后遗忘post-concussio nal syndrome 脑震荡综合症epilepticautomatisms自动症fugue神游症schizophr enia 精神分裂症delusiona l disorder 妄想性障碍mooddisorder心境障碍affective disorder 情感性精神障碍bipolardisorder双相障碍manicdepressiv e psychosis 躁狂抑郁性精神病flight ofidea意念飘忽delirious mania 谵妄性躁狂depressive pseudodem entia 抑郁性假性痴呆cyclothym ia 环性心境障碍disthymic disorder 恶劣心境障碍neuroses神经症consciousness意识preconsciousness前意识unconsciousness潜意识id本我ego自我superego超我panicattack惊恐发作anxietydisorder焦虑症phobia恐惧症depression抑郁obsessionandcompulsion强迫症状obsessiveidea强迫观念obsessiveintention强迫意向compulsivebehavior强迫行为hypochondriacalsymptom疑病症状hypochondriasis疑病症generalized anxiety symptom 广泛性焦虑障碍panicdisorder惊恐障碍agoraphob ia 场所恐惧症social phobia 社交恐惧症simple phobia 单一恐惧症somatofor m disorders 躯体形式障碍somatizat ion disorders 躯体化障碍chronic fatigue syndrome 慢性疲劳综合症CFShysteria癔症stress应激eustress良性应激distress不良应激stressor应激源generaladaptatio n syndrome 全身适应综合症GASpost-traumatic stress disorder 创伤后应激障碍PTSDadjustmentdisorder适应障碍physiolog icaldisorder related to psycholog ical factors 心理因素相关障碍eatingdisorder进食障碍anorexia nervosa 神经性厌食bulimia nervosa 神经性贪食insomnia失眠症hypersomnia嗜睡症sleepwalkingdisorder睡行症sleepterror夜惊nightmare梦魇sexual dysfuncti onal 性功能障碍sexualhypoactivity性欲减退impotence阳萎femalefailureofgenitalresponse冷阴orgasm disorder 性乐高潮障碍prematureejaculation早泄vaginismus阴道痉挛dyspareunia性交疼痛personalitydisorder人格障碍paranoidpersonali ty disorder 偏执性人格障碍schizoidpersonali ty disorder 分裂性人格障碍antisocial personali ty disorder 反社会性人格障碍impulsivepersonali ty disorder 冲动性人格障碍histrionic personali ty disorder 表演性人格障碍obsessive -compulsiv e personali ty 强迫性人格障碍anxiouspersonali ty disorder 焦虑性人格障碍sexual deviatin 性心理障碍transsexualism易性症fetishism恋物癖transvestism异装癖exhibitionism露阴癖voyeurism窥阴癖frotteurism摩擦癖sadism性施虐癖masochism性受虐癖homosexuality同性恋suicide自杀suicideidea自杀意念attemptedsuicide自杀未遂committedsuicide自杀死亡parasuicide类自杀deliberate self-harm蓄意自伤suicidegesture自杀姿势crisisintervention危机干预mental retardati on 精神发育迟滞intelligencequotient智商 IQchildhood autism 儿童孤独症attention deficitand hyperacti ve disorder ADHD注意缺陷与多动障碍conductdisorder品行障碍ticdisorder抽动障碍somatotherapy躯体治疗psychotropic drugs精神药物neurolept ics 神经阻滞剂antipsych otics 抗精神病药物antidepre ssants 抗抑郁药物mood stabilize rs 心境稳定剂antimanic drugs 抗躁狂药物anxiolyti c drugs 抗焦虑药物psychosti mulants 精神振奋药物nootropic drugs 脑代谢药物acute distonia 急性肌张力障碍akathisia静坐不能Parkinson ism 类帕金森症tardive dyskinesi a 迟发性运动障碍malignant syndrome 恶性综合症electric convulsiv e therapy 电抽搐治疗electrica l shock therapy 电休克治疗psychotherapy心理治疗individual therapy个别治疗coupletherapy夫妻治疗familytherapy家庭治疗grouptherapy集体治疗psychoana lytic therapy 精神分析治疗psychodyn amic therapy 心理动力学治疗brieftherapy短程治疗behavioral-cognitive therapy 行为-认知治疗humanisti c therapy 人本主义治疗systemictherapy系统治疗compliance依从性placebo effect 安慰剂效应therapeuticrelation治疗关系。

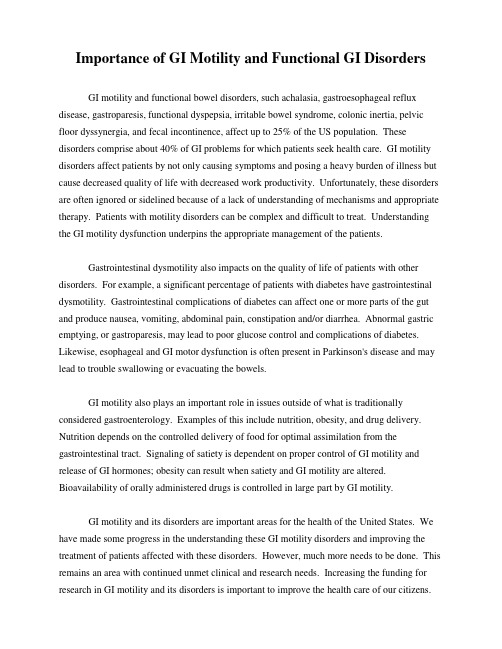

Importance of GI Motility Disorders (2)

Importance of GI Motility and Functional GI DisordersGI motility and functional bowel disorders, such achalasia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastroparesis, functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome, colonic inertia, pelvic floor dyssynergia, and fecal incontinence, affect up to 25% of the US population. These disorders comprise about 40% of GI problems for which patients seek health care. GI motility disorders affect patients by not only causing symptoms and posing a heavy burden of illness but cause decreased quality of life with decreased work productivity. Unfortunately, these disorders are often ignored or sidelined because of a lack of understanding of mechanisms and appropriate therapy. Patients with motility disorders can be complex and difficult to treat. Understanding the GI motility dysfunction underpins the appropriate management of the patients.Gastrointestinal dysmotility also impacts on the quality of life of patients with other disorders. For example, a significant percentage of patients with diabetes have gastrointestinal dysmotility. Gastrointestinal complications of diabetes can affect one or more parts of the gut and produce nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation and/or diarrhea. Abnormal gastric emptying, or gastroparesis, may lead to poor glucose control and complications of diabetes. Likewise, esophageal and GI motor dysfunction is often present in Parkinson's disease and may lead to trouble swallowing or evacuating the bowels.GI motility also plays an important role in issues outside of what is traditionally considered gastroenterology. Examples of this include nutrition, obesity, and drug delivery. Nutrition depends on the controlled delivery of food for optimal assimilation from the gastrointestinal tract. Signaling of satiety is dependent on proper control of GI motility and release of GI hormones; obesity can result when satiety and GI motility are altered. Bioavailability of orally administered drugs is controlled in large part by GI motility.GI motility and its disorders are important areas for the health of the United States. We have made some progress in the understanding these GI motility disorders and improving the treatment of patients affected with these disorders. However, much more needs to be done. This remains an area with continued unmet clinical and research needs. Increasing the funding for research in GI motility and its disorders is important to improve the health care of our citizens.Table 1. Prevalence of GI Motility Disorders Compared to Chronic Non-GI DisordersDyspepsia 20-25% Irritable bowel syndrome 10-25% Functional heartburn (GERD) 15.5% Chronic constipation 12-19%Hypertension 28% Migraine Headache 6-18% Asthma 8% Diabetes 8%IBS and chronic constipation, but not dyspepsia, are more common in females than males. Table 2. Prevalence of Upper GI SymptomsPercent of Population> 1 episode Relevantper month Symptoms Heartburn 21.6% 6.3% Regurgitation 16.4% 2.9% Dysphagia 7.8% 4.6% Bloating 10.7% 4.5% Postprandial Fullness 20.9% 3.6% Early Satiety 23.0% 5.3% Nausea 9.5% 2.2% Vomiting 2.7% 0.4% Belching/Burping 6.3% 3.0% Abdominal Pain 0.8%Abd Discomfort 4.3%From: Camilleri, Dubois, et al. Clinical Gastroenterology Hepatology 2005;3:543-552.Table 3. Societal Burden of GI SymptomsDays of Missed WorkDuring the past 3 months Asymptomatic 0.4Heartburn 1.0 Regurgitation 1.3Dysphagia 1.3 Postprandial Fullness 0.9Early Satiety 1.1Nausea 2.2Vomiting 4.4Belching 1.4Bloating 1.4Abdominal pain 1.9From: Camilleri, Dubois, et al. Clinical Gastroenterology Hepatology 2005;3:543-552. Table 4. Leading Gastrointestinal Symptoms Prompting an Outpatient Doctor Visit1. Abdominal Pain2. Diarrhea3. Nausea4. Vomiting5. Heartburn and indigestion6. Constipation7. Anal/rectal bleeding8. Blood in stool (melana)9. Other, unspecified GI symptoms10. Decreased Appetite11. Difficulty SwallowingFrom: Russo, Wei, Thiny, et al. Gastroenterology2004;126:1448-1453.Table 5. Leading Physician Diagnoses of Outpatient Doctor Visits for GI Symptoms1. Abdominal Pain2. GERD3. Gastroenteritis4. Gastritis5. Hemorrhoids6. Irritable bowel syndrome7. Hernias12. Dyspepsia13. ConstipationFrom: Russo, Wei, Thiny, et al. Gastroenterology2004;126:1448-1453.Table 6. Socioeconomic Impact of GI Motility DisordersQuality of life (QoL)Patients with GI motility disorders have lower QoL scores than population norms, those with organic GI diseases, and those with other chronic illnesses Resource utilizationFunctional GI disorders - 41% of diagnoses in GI clinics IBS: costs are 50% higher than for non-IBS controls Direct costs approximate $10 billion annuallyIndirect costs are as high as $20 billion annually Dyspepsia: costs are $2 billion annually。

心理学专业 英语作文

Psychology is a fascinating field that delves into the human mind and its processes. It is the scientific study of behavior and mental functions,encompassing a wide range of topics from the biological aspects of the brain to the social interactions of individuals. Here are some key areas and concepts that could be explored in an English essay about psychology:1.Historical Development:Discuss the evolution of psychology from its early philosophical roots to the establishment of it as a scientific discipline.Mention key figures like Sigmund Freud,Carl Jung,and B.F.Skinner,and their contributions to the field.2.Branches of Psychology:Psychology is a diverse field with various branches such as clinical psychology,cognitive psychology,developmental psychology,social psychology, and more.Each branch focuses on a different aspect of human behavior and mental processes.3.Theories and Models:Explore the different theories that have shaped the understanding of the human mind,such as behaviorism,cognitive theories, psychoanalytic theories,and humanistic psychology.Discuss how these theories have been applied in practice.4.Research Methods:Psychology relies heavily on empirical research.Discuss the various research methods used in psychology,including experiments,surveys,case studies,and longitudinal studies.Highlight the importance of ethical considerations in conducting research.5.Cognitive Processes:Delve into how humans perceive,learn,remember,and think. Discuss topics such as attention,memory,problemsolving,and decisionmaking.6.Emotional and Behavioral Disorders:Address the classification and treatment of various mental health disorders,such as anxiety disorders,mood disorders,and personality disorders.Discuss the role of psychologists in diagnosing and treating these conditions.7.Social Psychology:Examine how individuals are influenced by others and their social environment.Discuss topics like conformity,obedience,social influence,and group dynamics.8.Developmental Psychology:Explore how individuals develop from infancy to old age. Discuss stages of development,cognitive development,and the impact of social andcultural factors on development.9.Applied Psychology:Discuss how psychology is applied in various settings,such as education,business,sports,and healthcare.Highlight the role of psychologists in improving performance,wellbeing,and mental health.10.Ethical Issues:Address the ethical dilemmas that psychologists may face,such as confidentiality,informed consent,and the use of animals in research.11.Future of Psychology:Speculate on the future trends and developments in the field of psychology,including advances in technology,new research methodologies,and the potential for interdisciplinary integration.12.Cultural Perspectives:Discuss how cultural differences can influence psychological theories and practices.Consider the importance of cultural competence in understanding and treating diverse populations.13.Neuropsychology:Explore the relationship between the brain and behavior,focusing on how brain injuries or diseases can affect cognitive and emotional functioning.14.Positive Psychology:Discuss the relatively new field of positive psychology,which focuses on the study of happiness,wellbeing,and human strengths.15.Psychological Assessment:Explain the various tools and techniques used by psychologists to assess cognitive abilities,personality traits,and mental health status.When writing an essay on psychology,it is crucial to use clear and concise language, provide examples to support your arguments,and cite reputable sources to back up your claims.Additionally,it is important to maintain an objective and scientific tone throughout the essay.。

功能性消化不良患者的心理社会应激与异常的胃肌电活动有关

功能性消化不良患者的心理社会应激与异常的胃肌电活动有关Lee Y.-C.;张诗峰【期刊名称】《世界核心医学期刊文摘:胃肠病学分册》【年(卷),期】2006(0)11【摘要】Objective. Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a heterogeneous and loosely defined clinical syndrome that is characterized by persistent or recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen without any identifiable structural or biochemical basis. Gastric myoelectrical activity in functional dyspepsia patients with gastric reddish streaks as a subgroup has not previously been investigated and the potential role of psychosocial distress in the genesis of gastric dysrhythmia in patients with FD is unclear. Material and methods. Electrogastrography was performed in 45 patients with FD and 35 healthy controls for 30 min in the fasting state and 30 min postprandially. Psychological distress and the number and severity of stressful life events were measured using self-rating questionnaires. Results. FD patients had a higher percentage of pre-and postprandial dysrhythmia, lower dominant frequency, and a higher instability coefficient as compared to healthy controls. In FD patients, severity of stressful life events was positively correlated with the percentage of tachygastria in the fasting state ( r=0.43, p=0.005) and marginally positively co-rrelated with the percentage of postprandial tachygastria ( r =0.253, p =0.098) and instability coefficient of thedominant frequency ( r =0.256, p =0.093). Total nu-mber of stressful life events was marginally positively correlated with fasting tachygastria ( r=0.25, p =0.098) and instability coefficient of the postprandial dominant frequency ( r =0.287, p =0.056). Interpersonal sensitivity was found to be negatively correlated with fasting dominant frequency in FD patients (r = -0.311, p < 0.05). Conclusions. FD patients with gastric reddish streaks have abnormal fasting and postprandial gastric myoelectrical activity. Perceived severity of stressful life events and interpersonal sensitivity are associated with disturbance of gastric myoelectrical activity.【总页数】1页(P61-61)【关键词】心理社会应激;肌电活动;胃电图;应激生活事件;健康受试者;胃节律障碍;应激性生活事件;临床综合征;严【作者】Lee Y.-C.;张诗峰【作者单位】【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R57【相关文献】1.2.149精神心理因素对功能性消化不良患者胃电活动的影响 [J], 左国文;梁列新;郑琴芳;覃柳;张志雄2.2.40胃食管反流病(GERD)和动力障碍样功能性消化不良(GERD+)患者的胃肌电活动和排空活动:水负荷试验的作用 [J], M.Noar;K.Koch;L.Xu3.精神心理因素对功能性消化不良患者胃电活动的影响 [J], 左国文;梁列新;郑琴芳;覃柳;张志雄4.糖尿病胃轻瘫患者异常胃肌电活动的观察与分析 [J], 江汉龙;王正国5.西沙比利对功能性消化不良患者胃肌电活动的影响及疗效观察 [J], 石美珲;阮洪军因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

心理健康课件ppt英文

04

Methods for maintaining mental health

Establishing healthy lifestyle habits

Eating a balanced die

A healthy die is essential for maintaining psychological well being Incorporate a variety of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean protein, and health fits into your meals to support your mental health

Detailed description

OCD buffers may have invasive thoughts and perform reactive behaviors to allocate their anxiety Treatment options include exposure therapy and medicine

Detailed description

Anxiety disorder can manifest in various ways, such as panic attacks, phobias, and generalized anxiety Coping strategies include relaxation techniques, cognitive behavioral therapy, and managing stress through time management and self-care

Environmental factors

加巴喷丁治疗奥氮平致不宁腿综合征1例

·案例讨论·

http://www. psychjm. net. cn

加巴喷丁治疗奥氮平致不宁腿综合征 1 例

顾梦阅 1,狄东川 2,邱 俊 1,翟金国 1,2*

(1. 济宁医学院,山东 济宁 272000; 2. 济宁医学院第二附属医院,山东 济宁 272000

对多巴胺功能障碍以外的潜在机制进行深入研究。 既往多巴胺受体激动剂被广泛应用于 RLS 的

治疗,但长期应用可能会导致 RLS 症状恶化[9],且存 在加重精神症状的风险。加巴喷丁是一种 α2δ 钙通 道配体,已被证明可以改善 RLS[10],这类药物选择 性、高亲和力地结合钙通道的 α2δ 亚型 1 蛋白,调节 神经末梢的钙离子内流,从而导致兴奋性神经递质 (主要是谷氨酸)减少[11]。因此,加巴喷丁可能是治 疗抗精神病药物引起的 RLS 更安全的选择 。 [3,12] 此 外,国外已有报道,加巴喷丁成功治疗了氯氮平等 抗精神病药物诱导的 RLS[6]。本案例中,患者先后 三次在我院住院治疗,首次予以利培酮治疗,效果 欠 佳 ;后 调 整 为 氯 氮 平 继 续 治 疗 ,精 神 症 状 有 所 改 善 ,但 治 疗 过 程 中 患 者 出 现 白 细 胞 减 少 的 情 况 ;本 次治疗在奥氮平达到治疗剂量的过程中,患者精神 症状逐渐好转,PANSS 评分减分率>50%,考虑目前 用其他抗精神病药物替代奥氮平有加剧精神症状 的风险,在与患者家属讨论后,开始给患者服用加 巴喷丁,效果较好。

*通信作者:翟金国,E-mail:zhaijinguo@163. com)

【摘要】 本文目的是提示临床使用奥氮平过程中加强对不宁腿综合征(RLS)的识别与治疗。本文报道 1 例精神分裂症患者 服用奥氮平期间出现夜间双下肢不适、控制不住地想要活动双腿、无法入睡等 RLS 症状,服用加巴喷丁后,患者症状明显改善。

行为纠正疗法联合药物治疗在青少年情绪行为障碍患者中的应用效果

*基金项目:清远市2022年科技计划项目(2022ZCJF)①清远市第三人民医院 广东 清远 511500行为纠正疗法联合药物治疗在青少年情绪行为障碍患者中的应用效果*吴雪娥① 严金梅① 杨灵灵①【摘要】 目的:观察行为纠正疗法联合药物治疗在青少年情绪行为障碍患者中的应用效果。

方法:选择2021年6月—2022年9月清远市第三人民医院收治的84例青少年情绪行为障碍患者作为研究对象,采用随机数表法将84例青少年情绪行为障碍患者分为对照组(n =42)和试验组(n =42),对照组给予常规药物治疗,试验组则在对照组基础上给予行为纠正疗法。

对比两组干预前后Achenbach 儿童行为量表(CBCL)评分、焦虑自评量表(SAS)评分、抑郁自评量表(SDS)评分、生活质量及患者满意度。

结果:干预后,两组CBCL 评分、SAS 评分、SDS 评分较干预前均明显降低,且试验组低于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P <0.05)。

干预后,两组健康调查简表(SF-36)评分较干预前均明显升高,且试验组高于对照组,差异有统计学意义(P <0.05)。

试验组患者总满意度为97.62%,明显高于对照组的85.71%,差异有统计学意义(P <0.05)。

结论:行为纠正疗法联合药物治疗在青少年情绪行为障碍患者的临床治疗中具有较好的应用效果,其可有效改善情绪行为障碍和负性情绪,提高患者满意度,改善生活质量。

【关键词】 行为纠正疗法 药物治疗 青少年情绪行为障碍 Achenbach 儿童行为量表评分 doi:10.14033/ki.cfmr.2023.24.007 文献标识码 B 文章编号 1674-6805(2023)24-0029-05 Effect of Behavioral Modification Therapy Combined with Drug Therapy in Patients with Adolescent Emotional Behavior Disorder/WU Xue ’e, YAN Jinmei, YANG Lingling. //Chinese and Foreign Medical Research, 2023, 21(24): 29-33 [Abstract] Objective: To observe the effect of behavior modification therapy combined with drug therapy in patients with adolescent emotional behavior disorder. Method: A total of 84 patients with adolescent emotional behavior disorder who treated in Qingyuan Third People's Hospital from June 2021 to September 2022 were selected as the study objects, and 84 patients with adolescent emotional behavior disorder were divided into the control group (n =42) and the experimental group (n =42) by random number table method. The control group was given conventional drug treatment, and the experimental group was given behavioral modification therapy based on the control group. The Achenbach child behavior checklist (CBCL) score, self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) score, self-rating depression scale (SDS) score and quality of life before and after intervention and patients' satisfaction were compared between two groups. Result: After intervention, the CBCL scores, SAS scores and SDS scores in two groups were significantly lower than those before intervention, and those in the experimental group were lower than those in the control group, the differences were statistically significant (P <0.05). After intervention, the MOS item short from health survey (SF-36) scores in two groups were significantly higher than those before intervention, and that in the experimental group was higher than that in the control group, the differences were statistically significant (P <0.05). The total satisfaction of experimental group was 97.62%, which was significantly higher than 85.71% of the control group, and the difference was statistically significant (P <0.05). Conclusion: Behavior modification therapy combined with drug therapy has a good application effect in the clinical treatment of patients with adolescent emotional behavior disorder, which can effectively improve emotional behavior disorder, improve patients' satisfaction, improve quality of life. [Key words] Behavior modification therapy Drug therapy Adolescent emotional behavior disorder Achenbach child behavior checklist score First-author's address: Qingyuan Third People's Hospital, Qingyuan 511500, China 青少年情绪行为障碍是临床较为常见的心理问题,患病率在15岁左右的人群中相对较高[1-2]。

考研英语二词根词缀

考研英语二词根词缀词根和词缀在英语中发挥着重要的作用,可以帮助我们扩充词汇量,理解单词的意思以及构建正确的语境。

在考研英语二中,词根和词缀的知识点是必备的能力之一。

本文将介绍一些常见且有用的词根词缀,并提供一些例子帮助读者深入理解。

一、常见的词根1. Bio-(生命)- Biology(生物学):the study of living organisms- Biodegradable(可生物降解的):capable of being decomposed by living organisms- Bioengineering(生物工程):the use of engineering principles to manipulate biological systems2. Geo-(地质)- Geography(地理学):the study of the physical features of the earth and its atmosphere- Geology(地质学):the study of the earth's structure, history, and the processes that shape it- Geothermal(地热的):relating to or produced by the internal heat of the earth3. Psych-(心理)- Psychology(心理学):the study of the human mind and behavior - Psychologist(心理学家):a person who studies and analyzes human behavior and mental processes- Psychoanalysis(精神分析):a method of treating mental disorders by investigating unconscious conflicts二、常见的词缀1. -ful(充满的)- Wonderful(美妙的):extremely good or impressive; inspiring delight or admiration- Colorful(多彩的):full of different colors; vivid or picturesque - Insightful(有洞察力的):showing or having an accurate and deep understanding; perceptive2. -less(无)- Fearless(无畏的):lacking fear; not afraid- Homeless(无家可归的):without a home or a permanent place of residence- Endless(无尽的):having no limit or conclusion; infinite3. -ize(使…;变…)- Organize(组织):arrange into a structured whole; order- Visualize(形象化):form a mental image of; imagine- Analyze(分析):examine in detail in order to discover or reveal something三、例句解析1. The biodegradable packaging is more environmentally friendly than traditional plastic packaging.这种可生物降解的包装比传统塑料包装更环保。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。