第三章 建设工程造价和成本管理 工程管理专业英语ppt课件

《工程造价》第三章(1、2、3节)

二、建筑工程定额 (一)建筑工程定额的含义 是指在正常施工条件下完成规定计量单位的合格建筑安装工程所消耗的人工、 材料、施工机具台班、工期天数及相关费率等的数量基准。

(二)建设工程定额的分类 1.按定额反应的生产要素消耗内容分类 (1)劳动消耗定额 (2)机械消耗定额 (3)材料消耗定额

2.按定额的编制程序和用途分类(重点把握) 按定额的编制程序和用途,可以把建设工程定额分为施工定额、预算定额、概 算定额、概算指标和投资估算指标五种,其中工程计价定额是建设工程定额的 重要组成部分,包括预算定额、概算定额、概算书指标和投资估算指标。工程 计价定额直接用于工程计价。

工程造价=∑基本子项(分部分项工程)实物工程量×单位价格 i=1

式中i——第i个基本子项; n——工程结构分解得到的基本子项数目

每一个工程项目的建设都需要将整个项目进行分解,按照计量规 范或计价定额规定的基本子项或称为分部分项工程(又可称为假 定的建筑安装产进行计价

实物工程量单位价格组成一般可以有三类表现形式,即工料单价、 综合单 价和全费用单价。 如果实物工程量单位价格组成仅由人工、材料、机械 三类资源要素的消耗量和价格 形成,即 单位价格=∑(分部分项工程的资源要素消耗量X资源要素价格) 该单位价格是工料单价。 如果在单位价格中部分纳入人工、材料、 机械 费用以外的其他构成建筑安装工程造价的费用 (目前纳入的是管理费和利 润),则该单位价格是综合单价 如果单位价格包括全部建筑安装工程费用构 成, 则该单位价格是全费用单价。全费用单价是国际惯例,也是我国工程计 价改革与发展的方向。

施工机械 台班价格

设备预算价 格

设备及工器

设

具购置费

备

明

细

项

国家规定的

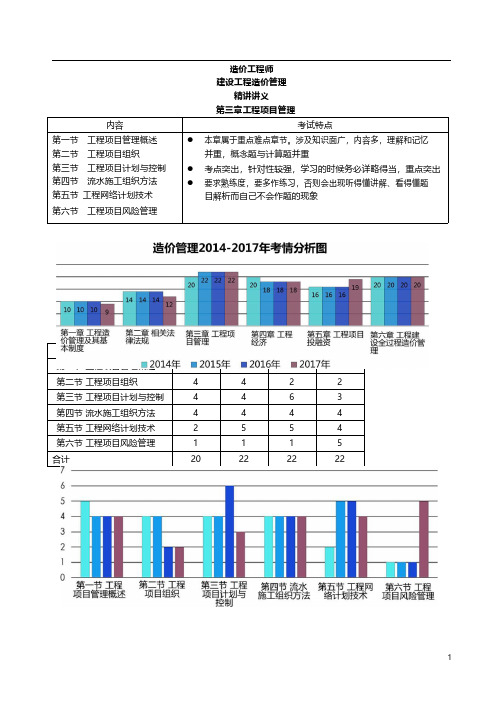

造价工程师(一级)建设工程造价管理 精讲讲义 第三章 工程项目管理

造价工程师建设工程造价管理精讲讲义第三章工程项目管理内容考试特点第一节工程项目管理概述第二节工程项目组织第三节工程项目计划与控制第四节流水施工组织方法第五节工程网络计划技术第六节工程项目风险管理●本章属于重点难点章节。

涉及知识面广,内容多,理解和记忆并重,概念题与计算题并重●考点突出,针对性较强,学习的时候务必详略得当,重点突出●要求熟练度,要多作练习,否则会出现听得懂讲解、看得懂题目解析而自己不会作题的现象节2014年2015年2016年2017年第一节工程项目管理概述5444第二节工程项目组织4422第三节工程项目计划与控制4463第四节流水施工组织方法4444第五节工程网络计划技术2554第六节工程项目风险管理1115合计202222221.工程项目的组成第一节工程项目管理概述『工程项目的组成与分类』项目组成内涵单项工程●具有独立的设计文件,建成后可以独立发挥生产能力或投资效益的一组配套齐全的工程项目单位(子单位)工程●具备独立施工条件并能形成独立使用功能的工程●分解为建筑工程和设备安装工程分部(子分部)工程●应按专业性质、建筑部位等划分。

建筑工程的分部工程包括:地基与基础、主体结构、装饰装修、屋面、给排水及采暖、通风与空调、建筑电气、智能建筑、建筑节能、电梯等工程。

分项工程●般按主要工种、材料、施工工艺、设备类别等划分。

例如:土方开挖、土方回填、钢筋、模板、混凝土、砖砌体、木门窗制作与安装、钢结构基础等。

【2017年真题】根据《建筑工程施工质量验收统一标准》,下列工程中,属于分部工程的有()。

A.砌体结构工程B.智能建筑工程C.建筑节能工程D.土方回填工程E.装饰装修工程答案:BCE解析:建筑工程中的分部工程包括地基与基础、主体结构、装饰装修、屋面、给排水及采暖、通风与空调、建筑电气、智能建筑、建筑节能、电梯等。

【2016年真题】根据《建筑工程施工质量验收统一标准》,下列工程中,属于分项工程的是()。

建设工程造价管理-精品课件(全)

B.通风与空调工程

C.钢结构基础(原教材:玻璃幕墙工程) D.门窗制作与安装工程 答案:B

答案:D

典型例题

2.按照我国现行规定,以下属于造价工程师执业范围的是 ( )。

A. 工程量清单的编制和审批

B. 设计方案的优化 C. 工程经济纠纷的鉴定 D. 工程保险理赔 答案: C

1.4—咨询企业资质条件

20

12

16 10

8 6

1.4 典型例题

3.根据《工程造价咨询企业管理办法》,属于甲级工程

1. 使用注册造价工程师名称;

2. 依法独立执行工程造价业务; 3. 在成果文件上签字并加盖执业印章;

4. 发起设立工程造价咨询企业;

5. 保管和使用本人的注册证书和执业印章;

6. 参加继续教育。

企业 独立,签 名 参 保

典型例题

1.根据《注册造价工程师管理办法》,取得造价工程师

职业资格证书的人员逾期未申请初始注册的,须( )方 可申请初始注册。 A.通过注册机关的可考核 B.重新参加执业资格考试并合格 C.由聘用单位出具证明 D.出具近一年的继续教育证明

2.美国工程新闻记录(ENR)发布的工程造价指数由( 个体指数组成。 )

A.构件钢材

B.波特兰水泥 C.木材 D.普通劳动力 E.通用施工机械

答案:ABCD

第二章 相关法律法规

第一节 建筑法及相关条例 第二节 招标投标法及其实施条例 第三节 合同法及价格法

2.1 典型习题

1.根据《建筑法》,建设工程安全生产管理应建立( 度。 A.责任 B.追溯 C.保证 )制

全国造价工程师执业资格考试

《建设工程造价管理》

《管理》分值分布(预计)

单选 第一章 第二章 第三章 第四章 第五章 6 6 12 12 12 多选 2 4 4 4 2 分值 10 14 20 20 16

工程管理专业英语

Unit 1 Types of Construction Project 建筑项目的类型

□ human endeavor 人类活动 □ Educational philosophies and practices take shape in the architecture of schools and colleges, while governments and corporation express their ―images‖ with structures that house their offices and production facilities. □ 教育理念和实践在学校建筑中得以体现,而政府与企业则通过容纳其 办公室和生产设备的建筑物来体现他们的“形象”。 □ It is difficult, if not impossible (= if possible 如果可能的话), to categorize neatly so great a spectrum of project. □ if not impossible 双重否定表示强烈肯定,否定句型表达肯定句型。 □ a spectrum of n. 系列,范围 □ frustrate vt. 阻碍,挫败 □ arbitrary adj. 武断的,主观的 □ transcend the boundary 超越边界 □ outnumber vt. 在数量上超过 □ parallel vt. 与…相似,类似

Unit 1 Types of Construction Project 建筑项目的类型

Warm Up Questions

1. Why is residential construction industry dominated by large numbers of very small firms? 2. Give some examples of project types of that office and commercial building construction may encompass. 3. What are the major distinctions of heavy construction compared to office and commercial building and residential housing construction? 4. What are the major distinctions of industrial construction in contrast with the basic materials characteristic of heavy engineering construction?

工程管理专业英语

Project cost managementAbstract: Described the current stage of the project cost management situation on the strengthening of the various stages of construction cost management of the importance of and raised a number of key initiatives.Keyword:project cost control, project management systemProject cost management is the basic contents to determine reasonable and effective control of the project cost. As the project cost to the project runs through the entire process, stage by stage can be divided into investment decision stage, the design and implementation phases. The so-called Project Cost effective control is the optimization of the construction plans and design programs on the basis of in the building process at all stages, use of certain methods and measures to reduce the cost of the projects have a reasonable control on the scope and cost of the approved limits.Engineering and cost management work of the current status of project cost management system was formed in the 1950s, 1980s perfect together. Performance of the country and directly involved in the management of economic activities. With the historical process, after recovery, reform and development, formed a relatively complete budget estimate of quota management system. However, as the socialist market economic development, the system's many problems have also exposed.Due to the technical personnel of the project technical and economic concepts and a weak awareness of cost control, cost management makes the quality difficult to raise. Project Cost control is difficult to achieve long-term goals. Our task now is to make the cost management in line with China's national conditions of the market economy system goal, learn from the advanced experience of the developed countries, and establish sound market economic laws of project cost management system, efforts to increase the project cost levels.项目成本管理摘要:描述现阶段的工程造价管理的情况,加强了各阶段的工程造价管理工作的重要性,并提出了若干关键性举措。

建设工程造价管理基础知识ppt课件

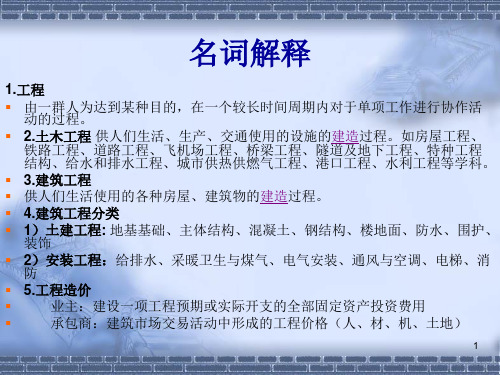

▪

承包商:建筑市场交易活动中形成的工程价格(人、材、机、土地)

1

6.工程建设过程

项目建议及可 研阶段

初设

技术设计

施工图设计

招投标

实施

竣工

后投产

投资估算

概算

修正概算

预算

合同价

结算

实际 造价

决算

2

住宅小区

建设项目

在一个总体规划和设计的范围内

实行统一施工,统一管理,统一核算 的工程

商场 体育馆 住宅楼 中学

▪ 第一章 一般规定 第二章 合同的订立第三章 合同的效力 第四章 合同的履行第五章 合同的变更和转让 第六章 合 同的权利义务终止第七章 违约责任 第八章 其他规定第九 章 买卖合同 第十章 供用电、水、气、热力合同 第十一章 赠与合同 第十二章 借款合同 第十三章 租赁合同 第十

四章 融资租赁合同 第十五章 承揽合同 第十六章 建 设工程合同 第十七章 运输合同 第十八章 技术合

20

建设工程造价管理制度

▪ 一、建设工程造价管理体制 ▪ 1、政府部门的行政管理 ▪ 政府设置了多层管理机构,明确了管理权

限和职责范围,形成一个严密的建设工程造 价宏观管理组织系统。 ▪ 工程造价管理的组织机构 ▪ 标准定额司 省总站 市站 区分站

21

政府在工程造价管理方面的职能

▪ 1 制定工程造价管理有关法规、规章并监督其实施; ▪ 2 组织制定全国统一经济定额并监督指导其实施; ▪ 3 制定造价咨询企业的资质标准并监督其执行; ▪ 4 负责全国工程造价咨询企业资质管理工作; ▪ 5 制定造价专业技术人员执业标准并监督 执行; ▪ 6 监督管理建设工程造价管理的有关行为。

▪ 招标文件不得要求或者标明特定的生产供应者以及含有倾向或者排斥 潜在投标人的其他内容。

工程管理专业英语

目录Unit One About Engineering Economy第一单元关于工程经济Unit Two The Principles of Engineering Economy第二单元工程经济原理Unit Three Cost Concept第三单元成本概念Unit Four Time Value of Money第四单元金钱的时间价值Unit Five The Basic Methods of Engineering Economy 第五单元工程经济的基本方法Unit Six The Definition of a “Project”第六单元项目的定义Unit Seven Why Project Management?第七单元为什么要对项目进行管理?Unit Eight The Project Life Cycle第八单元项目的寿命周期Unit Nine The Project Manager第九单元项目经理Unit Ten Project Planning第十单元制订项目计划Unit Eleven Initial Project Coordination第十一单元开始的项目协调Unit Twelve Budgeting and Cost Estimation第十二单元预算和成本估算Unit Thirteen The Monitoring System of Project第十三单元项目监测系统Unit Fourteen Project Control第十四单元项目控制Unit Fifteen Conditions of Contract for Construction(Excerpts)第十五单元施工合同条件(节选)Unit One About Engineering EconomyEngineering economy——what is it, and why is it important? The initial reaction of many engineering students to these questions is “Money matters will be handled by someone else. It is not something I need to worry about.” In reality, any engineering project must be not only physically realizable, but also economically affordable. For example, a child's tricycle could be built with an aluminum frame or a composite frame. Some may argue that because the composite frame will be stronger and lighter, it is a better choice. However, there is not much of a market for thousand dollar tricycles! One might suggest that this argument is ridiculously simplistic and that common sense would dictate choosing aluminum for the framing material. Although the scenario is an exaggeration, it reinforces the idea that the economic factors of a design weigh heavily in the design process, and that engineering economy is an integral part of that process, regardless of the engineering discipline. Engineering, without economy, makes no sense at all.In broad terms, for an engineering design to be successful, it must be technically sound and produce benefits. These benefits must exceed the costs associated with the design in order for the design to enhance net value. The field of engineering economy is concerned with the systematic evaluation of the benefits and costs of projects involving engineering design and analysis. In other words, engineering economy quantifies the benefits and costs associated with engineering projects to determine whether they make (or save) enough money to warrant their capital investments. Thus, engineering economy requires the application of engineering design and analysis principles to provide goods and services that satisfy the consumer at an affordable cost. As we shall see, engineering economy is as relevant to the design engineer who considers material selection as it is to the chief executive officer whoapproves capital expenditures for new ventures.The technological and social environments in which we live continue to change at a rapid rate. In recent decades, advances in science and engineering have made space travel possible, transformed our transportation systems, revolutionized the practice of medicine, and miniaturized electronic circuits so that a computer can be placed on a semiconductor chip. The list of such achievements seems almost endless. In your science and engineering courses, you will learn about some of the physical laws that underlie these accomplishments.The utilization of scientific and engineering knowledge for our benefit is achieved through the design of things we use, such as machines, structures, products, and services. However, these achievements don't occur without a price, monetary or otherwise. Therefore, the purpose of this book is to develop and illustrate the principles and methodology required to answer the basic economic question of any design: Do its benefits exceed its costs?The Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology states that engineering “is the profession in which a knowledge of the mathematical and natural sciences gained by study, experience, and practice is applied with judgment to develop ways to utilize, economically, the materials and forces of nature for the benefit of mankind.”*In this definition, the economic aspects of engineering are emphasized, as well as the physical aspects. Clearly, it is essential that the economic part of engineering practice be accomplished well.Therefore,engineering economy is the dollars-and-cents side of the decisions that engineers make or recommend as they work to position a firm to be profitable in a highly competitive marketplace.Inherent to these decisions are trade-offs among different types of costs and the performance(response time,safety, weight, reliability, etc.) provided by the proposed design or problem solution.The mission of engineering economy is to balance thesetrade-offs in the most economical manner. For instance, if an engineer at Ford Motor Company invents a new transmission lubricant that increases fuel mileage by 10% and extend s the life of the transmission by 30,000 miles,how much can the company afford to spend to implement this invention? Engineering economy can provide an answer.A few more of the myriad situations in which engineering economy plays a cruclal role come to mind:1. Choosing the best design for a high-efficiency gas furnace.2. Selecting the most suitable robot for a welding operation on an automotive assembly line.3. Making a recommendation about whether jet airplanes for an overnight delivery service should be purchased or leased.4. Determining the optimal staffing plan for a computer help desk.From these illustrations,it should be obvious that engineering economy includes significant technical considerations.Thus,engineering economy involves technical analysis with emphasis on the economic aspects, and has the objective of assisting decisions.This is true whether the decision maker is an engineer interactively analyzing alternatives at a computer-aided design workstation or the Chief Executive Officer(CEO)considering a new project.A n engineer who is unprepared to excel at engineering economy is not properly equipped for,his or her job.Cost considerations and comparisons are fundamental aspects of engineering practice.This basic point was emphasized in Section 1.1. However, the development of engineering economy methodology, which is now used in nearly all engineering work,is relatively recent.This does not mean that,historically, costs were usually overlooked in engineering decisions. However, the perspective that ultimate economy is a primary concern to the engineer and the availability of sound techniques to address this concern differentiate this aspect of modern engineering practicefrom that of the past.A pioneer in the field was Arthur M.Wellington, a civil engineer, who in the latter part of the nineteenth century specifically addressed the role of economic analysis in engineering projects. His particular area of interest was railroad building in the United States.This early work was followed by other contributions in which the emphasis was on techniques that depended primarily on financial and actuarial mathematics.In 1930. Eugene Grant published the first edition of his textbook.+ This was a milestone in the development of engineering economy as we know it today. He placed emphasis on developing an economic point of view in engineering,and(as he stated in the preface) “this point of view involves a realization that quite as definite a body of principles governs the economic aspects of an engineering decision as governs its physical aspects.” In 1942,Woods and DeGarmo wrote the first edition of this book,later titled Engineering Economy.Unit Two The Principles of Engineering EconomyThe development, study, and application of any discipline must begin with a basic foundation.We define the foundation for engineering economy to be a set of principles,or fundamental concepts,that provide a comprehensive doctrine for developing the methodology, These principles will be mastered by students as they progress through this book. However, in engineering economic analysis, experience has shown that most errors can be traced to some violation of or lack of adherence to the basic principles.Once aproblem or need has been clearly defined, the foundation of the discipline can be discussed in terms of seven principles.PRINCIPLE1-DEVELOP THE ALTERNATIVES:The choice(decision) is among alternatives. The alternatives need to be identified and then defined for subsequent analysisA decision situation involves making a choice among two or more alternatives. Developing and defining the alternatives for detailed evaluation is important because of the resulting impact on the quality of the decision.Engineers and managers should place a high priority on this responsibility.Creativity and innovation are essential to the process.One alternative that may be feasible in a decision situation is making no change to the current operation or set of conditions(i.e., doing nothing). If you judge this option feasible,make sure it is considered in the analysis. However, do not focus on the status quo to the detriment of innovative or necessary change.PRINCIPLE2-FOCUS ON THE DIFFERENCES:Only the differences in expected future outcomes among the alternatives are relevant to their comparison and should be considered in the decision.If all prospective outcomes of the feasible alternatives were exactly the same,there would be no basis or need for comparison.We would be indifferent among the alternatives and could make a decision using a random selection.Obviously, only the differences in the future outcomes of the alternatives are important.Outcomes that are common to all alternatives can be disregarded in the comparison and decision.For example,if your feasible housing alternatives were two residences with the same purchase(or rental)price,price would be inconsequential to your final choice.Instead,the decision would depend on other factors, such as location and annual operating and maintenance expenses. This example illustrates,in a simple way, Principle 2,which emphasizes the basic purpose of an engineeringeconomic analysis:to recommend a future course of action based on the differences among feasible alternatives.PRINCIPLE 3-USE A CONSISTENT VIEWPOINT:The prospective outcomes of the alternatives, economic and other, should be consistently developed from a defined viewpoint (perspective).The perspective of the decision maker, which is often that of the owners of the firm,would normally be used.However, it is important that the viewpoint for the particular decision be first defined and then used consistently in the description analysis,and comparison of the alternatives.As an example,consider a public organization operating for the purpose of developing a river basin,including the generation and wholesale distribution of electricity from dams on the river system.A program is being planned to upgrade and increase the capacity of the power generators at two sites. What perspective should be used in defining the technical alternatives for the program? The “owners of the firm” in this example means the segment of the public that will pay the cost of the program and their viewpoint should be adopted in this situation.Now let us look at an example where the viewpoint may not be that of the owners of the firm.Suppose that the company in this example is a private firm and that the problem deals with providing a flexible benefits package for the employees. Also, assume that the feasible alternatives for operating the plan all have the same future costs to the company.The alternatives,however, have differences from the perspective of the employees,and their satisfaction is an important decision criterion. The viewpoint for this analysis and decision should be that of the employees of the company as a group, and the feasible alternatives should be defined from their perspective.PRINCIPLE 4-USE A COMMON UNIT OF MEASURE:Using a common unit of measurement to enumerate asmany of the prospective outcomes as possible will simplify the analysis and comparison of the alternatives.It is desirable to make as many prospective outcomes as possible commensurable (directly comparable).For economic consequences,a monetary unit such as dollars is the common measure.You should also try to translate other outcomes(which do not initially appear to be economic) into the monetary unit.This translation,of course, will not be feasible with some of the outcomes, but the additional effort toward this goal will enhance commensurabilitv and make the subsequent analysis and comparison of alternatives easier.What should you do with the outcomes that are not economic(i.e., the expected consequences that cannot be translated (and estimated) using the monetary unit)? First, if possible, quantify the expected future results using an appropriate unit of measurement for each outcome.If this is not feasible for one or more outcomes,describe these consequences explicitly so that the information is useful to the decision maker in the comparison of the alternatives.PRINCIPLE 5-CONSIDER ALL RELEV ANT CRITERIASelection of a preferred alternative (decision making) requires the use of a criterion (or several criteria). The decision process should consider both the outcomes enumerated in the monetary unit and those expressed in some other unit of measurement or made explicit in a descriptive manner.The decision maker will normally select the alternative that will best serve the long-term interests of the owners of the organization. In engineering economic analysis, the primary criterion relates to the long-term financial interests of the owners. This is based on the assumption that available capital will be allocated to provide maximum monetary return to the owners. Often, though, there are other organizational objectives you would like to achieve with your decision, and these should be considered and given weight in the selection of an alternative. These nonmonetarv attributes andmultiple objectives become the basis for additional criteria in the decision-making process.PRINCIPLE6-MAKE UNCERTAINTY EXPLICIT:Uncertainty is inherent in projecting (or estimating) the future outcomes of the alternatives and should be recognized in their analysis and comparison.The analysis of the alternatives involves projecting or estimating the future consequences associated with each of them.The magnitude and the impact of future outcomes of any course of action are uncertain.Even if the alternative involves no change from current operations, the probability is high that today‟s estimates of, for example,future cash receipts and expenses will not be what eventually occurs. Thus, dealing with uncertainty is an important aspect of engineering economic analysis and is the subject of Chapters 10 and 13.PRINCIPLE 7- REVISIT YOUR DECISIONS:Improved decision making results from an adaptive process, to the extent practicable, the initial projected outcomes of the selected alternative should be subsequently compared with actual results achieved.A good decision-making process can result in a decision that has an undesirable outcome. Other decisions, even though relatively successful,will have results significantly different from the initial estimates of the consequences. Learning from and adapting based on our experience are essential and are indicators of a good organization.The evaluation of results versus the initial estimate of outcomes for the selected alternative is often considered impracticable or not worth the effort. Too often, no feedback to the decision-making process occurs. Organizational discipline is needed to ensure tha t implemented decisions are routinely postevaluated and that the results used to improve future analyses of alternatives and the quality of decision making.The percentage of important decisions inan organization that are not postevaluated should be small.For example,a common mistake made in the comparison of alternatives is the failure to examine adequately the impact of uncertainty in the estimates for selected factors on the decision.Only postevaluations will highlight this type of weakness in the engineering economy studies being done in an organization.Unit Three Cost Concept3.1 Fixed, Variable, and Incremental CostsFixed costs are those unaffected by changes in activity level over a feasible range of operations for the capacity or capability available. Typical fixed costs include insurance and taxes on facilities, general management and administrative salaries, license fees, and interest costs on borrowed capital.Of course, any cost is subject to change, but fixed costs tend to remain constant over a specific range of operating conditions. When large changes in usage of resources occur, or when plant expansion or shutdown is involved, fixed costs will be affected.Variable costs are those associated with an operation that vary in total with the quantity of output or other measures of activity level. If you were making an engineering economic analysis of a proposed change to an existing operation, the variable costs would be the primary part of the prospective differences between the present andchanged operations as long as the range of activities is not significantly changed. For example, the costs of material and labor used in a product or service are variable costs, because they vary in total with the number of output units, even though the costs per unit stay the same.An incremental cost (or incremental revenue) is the additional cost (or revenue) that results from increasing the output of a system by one (or more) units. Incremental cost is often associated with “go-no go” decisions that involve a limited change in output or activity level.③For instance, the incremental cost per mile for driving an automobile may be. $0.27, but this cost depends on considerations such as total mileage driven during the year (normal operating range), mileage expected for the next major trip, and the age of the automobile. Also, it is common to read of the “incremental cost of producing a barrel of oil” and “incremental cost to the state for educating a student.” As these examples indicate, the incremental cost (or revenue) is often quite difficult to determine in practice.3.2 Recurring and Nonrecurring CostsThese two general cost terms are often used to describe various types of expenditures. Recurring costs are those that are repetitive and occur when an organization produces similar goods or services on a continuing basis. Variable costs are also recurring costs, because they repeat with each unit of output. But recurring costs are not limited to variable costs. A fixed cost that is paid on a repeatable basis is a recurring cost. For example, in an organization providing architectural and engineering services, office space rental, which is a fixed cost, is also a recurring cost.Nonrecurring costs, then, are those which are not repetitive, even though the total expenditure may be cumulative over a relatively short period of time. Typically, nonrecurring costs involve developing or establishing a capability or capacity to operate. For example, the purchase cost for real estate upon which a plant will bebuilt is a nonrecurring cost, as is the cost of constructing the plant itself.3.3 Direct, Indirect, and Standard CostsThese frequently encountered cost terms involve most of the cost elements that also fit into the previous overlapping categories of fixed and variable costs, and recurring and nonrecurring costs. Direct costs are costs that can be reasonably measured and allocated to a specific output or work activity. The labor and material costs directly associated with a product, service, or construction activity are direct costs. For example, the materials needed to make a pair of scissors would be a direct cost.Indirect costs are costs that are difficult to attribute or allocate to a specific output or work activity. The term normally refers to types of costs that would involve too much effort to allocate directly to a specific output. In this usage, they are costs allocated through a selected formula (such as, proportional to direct labor hours, direct labor dollars, or direct material dollars) to the outputs or work activities. For example, the costs of common tools, general supplies, and equipment maintenance in a plant are treated as indirect costs.Overhead consists of plant operating costs that are not direct labor or direct material costs. In this book, the terms indirect costs, overhead, and burden are used interchangeably. Examples of overhead include electricity, general repairs, property taxes, and supervision. Administrative and selling expenses are usually added to direct costs and overhead costs to arrive at a unit selling price for a product or service. (Appendix A provides a more detailed discussion of cost accounting principles.)Various methods are used to allocate overhead costs among products, services, and activities. The most commonly used methods involve allocation in proportion to direct labor costs, direct labor hours, direct materials costs, the sum of direct labor and direct materials costs (referred to as prime cost in a manufacturing operation), or machine hours. In each of these methods, it isnecessary to know what the total overhead costs have been or are estimated to be for a time period (typically a year) to allocate them to the production (or service delivery) outputs.Standard costs are representative costs per unit of output that are established in advance of actual production or service delivery. They are developed from anticipated direct labor hours, materials, and overhead categories (with their established costs per unit). Because total overhead costs are associated with a certain level of production, this is an important condition that should be remembered when dealing with standard cost data (for example, see Section 2.5.3). Standard costs play an important role in cost control and other management functions. Some typical uses are the following:1. Estimating future manufacturing costs.2. Measuring operating performance by comparing actual cost per unit with the standard unit cost.3. Preparing bids on products or services requested by customers.4. Establishing the value of work in process and finished inventories.3.4 Cash Cost versus Book CostA cost that involves payment of cash is called a cash cost (and results in a cash flow) to distinguish it from one that does not involve a cash transaction and is reflected in the accounting system as a noncash cost. This noncash cost is often referred to as a book cost. Cash costs are estimated from the perspective established for the analysis (Principle 3, Section 1.3) and are the future expenses incurred for the alternatives being analyzed. Book costs are costs that do not involve cash payments, but rather represent the recovery of past expenditures over a fixed period of time. The most common example of book cost is the depreciation charged for the use of assets such as plant and equipment. In engineering economic analysis, only those costs that are cash flows or potential cash flows from the defined perspective for the analysis need to be considered.Depreciation, for example, is not a cash flow and is important in an analysis only because it affects income taxes, which are cash flows. We discuss the topics of depreciation and income taxes in Chapter 6.3.5 Sunk CostA sunk cost is one that has occurred in the past and has no relevance to estimates of future costs and revenues related to an alternative course of action. Thus, a sunk cost is common to all alternatives, is not part of the future (prospective) cash flows, and can be disregarded in an engineering economic analysis. For instance, sunk costs are nonrefundable cash outlays, such as earnest money on a house or money spent on a passport.We need to be able to recognize sunk costs and then handle them properly in an analysis. Specifically, we need to be alert for the possible existence of sunk costs in any situation that involves a past expenditure that cannot be recovered, or capital that has already been invested and cannot be retrieved.The concept of sunk cost is illustrated in the next simple example. Suppose that Joe College finds a motorcycle he likes and pays $40 as a down payment, which will be applied to the $1,300 purchase price, but which must be forfeited if he decides not to take the cycle. Over the weekend, Joe finds another motorcycle he considers equally desirable for a purchase price of $1,230. For the purpose of deciding which cycle to purchase, the $40 is a sunk cost and thus, would not enter into the decision, except that it lowers the remaining cost of the first cycle. The decision then is between paying $1,260 ($1,300~$40) for the first motorcycle versus $1,230 for the second motorcycle.In summary, sunk costs result from past decisions and therefore are irrelevant in the analysis and comparison of alternatives that affect the future. Even though it is sometimes emotionally difficult to do, sunk costs should be ignored, except possibly to the extent that their existence assists you to anticipate better what will happen in the future.3.6 Opportunity CostAn opportunity cost is incurred because of the use of limited resources, such that the opportunity to use those resources to monetary advantage in an alternative use is foregone. Thus, it is the cost of the best rejected (i.e., foregone) opportunity and is often hidden or implied.For example, suppose that a project involves the use of vacant warehouse space presently owned by a company. The cost for that space to the project should be the income or savings that possible alternative uses of the space may bring to the firm. In other words, the opportunity cost for the warehouse space should be the income derived from the best alternative use of the space. This may be more than or less than the average cost of that space obtained from the accounting records of the company.Consider also a student who could earn $20,000 for working during a year, but chooses instead to go to school for a year and spend $5,000 to do so. The opportunity cost of going to school for that year is $25,000:$5,000 cash outlay and $20,000 for income foregone. (This figure neglects the influence of income taxes and assumes that the student has no earning capability while in school.)3.7 Life-Cycle CostIn engineering practice, the term life-cycle cost is often encountered. This term refers to a summation of all the costs, both recurring and nonrecurring, related to a product, structure, system, or service during its life span, The life cycle is illustrated in Figure 2-2. The life cycle begins with identification of the economic need or want (the requirement) and ends with retirement and disposal activities. It is a time horizon that must be defined in the context of the specific situation-whether it is a highway bridge, a jet engine for commercial aircraft, or an automated flexible manufacturing cell for a factory. The end of the life cycle may be projected on a functional or an economic basis. For example, the amount of time that a structure or piece of equipment is able to perform economically maybe shorter than that permitted by its physical capability. Changes in the design efficiency of a boiler illustrate this situation. The old boiler may be able to produce the steam required, but not economically enough for the intended use.Unit Four Time Value of Money4.1 IntroductionThe term capital refers to wealth in the form of money or property that can be used to produce more wealth. The majority of engineering economy studies involve commitment of capital for extended periods of time, so the effect of time must be considered. In this regard, it is recognized that a dollar today is worth more than a dollar one or more years from now because of the interest (or profit) it can earn. Therefore, money has a time value.4.2 Why Consider Return to Capital?Capital in the form of money for the people, machines, materials, energy, and other things needed in the operation of an。

第3章建设项目决策阶段工程造价的计价与控制40页PPT文档

机械工业出版社《工程造价管理》

3.2 建设项目可行性研究

3.2.1 可行性研究的概念与作用

• 可行性研究的概念

• 是在投资决策前,通过对项目的主要内容和配套条件,如

市场需求、资源供应、建设规模、工艺路线、设备选型、 环境影响、盈利能力等,从经济、技术、工程等方面进行 深入细致的调查研究和分析比较,并对项目建成后可能取 得的经济、社会、环境效益进行科学的预测和评价,为项 目决策提供依据的一种综合性的系统分析方法

3.2 建设项目可行性研究

3.2.2 可行性研究的内容及编制

• 可行性研究的内容

一般工业建设项目的可行性研究就包含以下几个方面的内 容:

• 1)总论

• 项目背景 • 项目概况 • 问题与建议

• 2)市场预测

• 包括:产品市场供应预测、产品市场需求预测、产品目标

市场分析、价格现状与预测、市场竞争力分析、市场风险

机械工业出版社《工程造价管理》

3.1 概述

3.1.2 项目决策阶段影响工程造价的主要因素

• 1、项目建设规模

每一个建设项目都存在着一个合理规模的选择问题,项目 规模合理化的制约因素有:

• 市场因素 • 技术因素 • 环境因素

• 2、建设地区及建设地点(厂址)

• 建设地区选择是指在几个不同地区之间对拟建项目适宜配

量把厂址放在荒地,劣地,山地和空地,尽可能不占或少 占耕地,并力求节约用地

• 减少拆迁移民 • 尽量选在工程地质、水文地质条件较好的地段,土壤耐压

力应满足拟建厂的要求,严防选在断层、溶岩、流沙层和 有用矿床上,以及洪水淹没区,已采矿坑塌陷区,滑坡区

• 有利于厂区合理布置和安全运行。厂区土地面积与外形能

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

• guarantees [gærənˈtiːz]

• thorough [ˈθʌrə] adj. 彻底的;十分的;周密的

n. 保证;保证书(guarantee的复数)

• hourly rate

• stipulations [stɪpjuˈleɪʃnz] n. 规定(stipulation的复数) 计时工资;每小时工资率;按小时计的工资额

• attributes [ˈætrɪbjuːts] n. 属性;特质(attribute的复数) • disaggregate [dɪsˈægrɪgeɪt] vt.分解

• assumed [əˈsjuːmd] adj.假定的

• collectively [kəˈlektɪvlɪ] adv.共同地

• bill of quantities 工程量清单

• wheelbarrows [ˈwiːlbærəʊz] n.手推车(wheelbarrow的复数)

• water hoses 水管 • extension cords 延长绳 • lump-sum 一次总付的 • keep in mind 牢记 • paramount to 最重要的 • making up 组成 • qualifications [kwɒlɪfɪˈkeɪʃns]

Preliminary Cost

Quantity Survey

项目成本系统

精度范围

Estimate

初步成本估算

工料测量

LOGO

• reduced to 简化为 • retrieve [rɪˈtriːv] vt.重新得到;检索数据 • ongoing [ˈɒngəʊɪŋ] adj. 仍在进行的 • pertinent [ˈpɜːtɪnənt] adj. 有关的;切题的 • classification [ˌklæsɪfɪˈkeɪʃn] n. 分类 • covers [ˈkʌvəz]

ONE

Look up relevant literatures to find out if there is any other classification of cost estimation.

Review Questions and Problems

Discuss how to make the cost estimation more accurate.

TWO

02

Basic Elements of Cost Estimation

成本估算的基本要素

Basic Elements of Cost Estimation

Material Costs 材料费

Indirect Labour Costs 业主

Labour Costs 人工费

The Cost of Heavy Equipment 重型设备成本

• interrelate... with 相互关联 • allowance [əˈlauəns] n. 津贴 • work category 工作类别 • accounts for 占……比例 • earth-moving machines 土方机械;掘土机 • concrete plants 混凝土加工厂 • truck cranes 货车起重机 • power tools 电动工具 • concrete vibrators 混凝土振动器 • concrete buggies 混凝土车

• corresponding [ˌkɒrəˈspɒndɪŋ] adj. 相应的

• raw [rɔː] adj. 未加工的

• laborious [ləˈbɔːrɪəs] adj.费力的

• generated [ˈdʒenəreɪtɪd] vt.生成(generate的过去分词) • break down 分解

• markup [ˈm ' ːkʌp] n.(在成本基础上的)加价;利润 • margin [ˈm ' ːdʒɪn] n. 利润 • at the close of 在……结束时 • contingency [kənˈtɪndʒənsi]

n. 意外/偶然开支;应急;不可预见费 • management philosophy 管理哲学 • calls for 要求 • appraisal [əˈpreɪzl] n. 评价 • imponderables [ɪmˈpɒndərəblz]

• decomposing [diːkəmˈpəʊzɪŋ]

• summation [sʌˈmeɪʃn] n.求和;总和

vt & vi.分解(decompose的动名词)

• expenditure item 支出项目

LOGO

• construction supervision 施工监理

• compilation [ˌkɒmpɪˈleɪʃn] n. 汇编

• work package 工作包

vt.推算(extrapolate的过去分词)

• agreement [əˈgriːmənt] n.协议

• working drawings 施工图

• close [kləus] adj.接近的

The first classification, the degree of project definition, is based upon the percentage of completed architectural and engineering designs. It defines available input information to the estimator. The second classification, the end usage of the estimate, is based on available data progress and covers conceptual estimates for investment feasibility, and studies funding authorization, budgets, and contractor detail estimates for lump-sum bidding. The third classification, the estimate generating methodology, is based on processes employed to forecast building costs that are stochastic and deterministic.

第一种分类(标准)为项目定义的细 致程度,是基于已完成的建筑设计和 施工设计的百分比。它为估算人员 定义了可用的输入信息。第二种分 类(标准)为估算的最终用途,是基于 可获取的数据进展,涵盖投资可行性 的概念性估算,并研究资金授权、预 算和承包商对总投标的详细估价。 第三种分类(标准)为估算的生成方 法,是基于预测随机性和确定性的建 筑成本的过程。

n. 无法估量的事物(imponderable的复数) • have a bearing on 影响到

Some choose to include all elements of labour expense in a single hourly rate. Others evaluate direct labour cost separately from indirect cost. Some contractors compute regular and overtime labour costs separately, while others combine scheduled overtime with straight time to arrive at an average hourly rate. Some evaluate labour charges using production rates, others use labour unit costs.

vt.覆盖;包含(cover的第三人称单数) • investment[Inˈvestmənt] n.投资 • employed to 使用

• prudent [ˈpruːdnt] adj. 审慎的;精明的 • varies from 不同于 • expressed as 表示为 • positive [ˈpɒzətɪv] adj. 正的 • negative [ˈnegətɪv] adj. 负的 • surrounding [səˈraʊndɪŋ]

n. 资格;条件(qualification的复数)

LOGO

• stipulate [ˈstɪpjuleɪt] vt.规定 • job site 作业现场 • hoisting [ˈhɔIstɪŋ] n. 吊装(设备) • subbid n. 分标 • amounts [əˈmaunt] n. 数量(amount的复数) • contracting with 与……签订合同 • overhead [ˈəʊvəhed] n. 管理费 • job overhead 工作管理费 • field overhead 工地管理费 • chargeable [ˈtʃ ' ːdʒəbl] adj. 可以记账的 • reliable [rɪˈlaɪəbl] adj. 可靠的

• compiled [kəmˈpaɪld] vt.编制(compile的过去分词)

vt.扩展(extend的第三人称单数)

• fundamentally [fʌndə ˈmentəlɪ] adv. 根本地

• check [tʃek] vt.核实

• extrapolated [ɪkˈstræpəleɪtɪd]

vt.围绕(surround的动名词) • outlay [ˈaʊtleɪ] n. 费用,支出 • plant's manufacturing 设备的制造