Predicting European Union Recessions in the Euro Era 欧盟

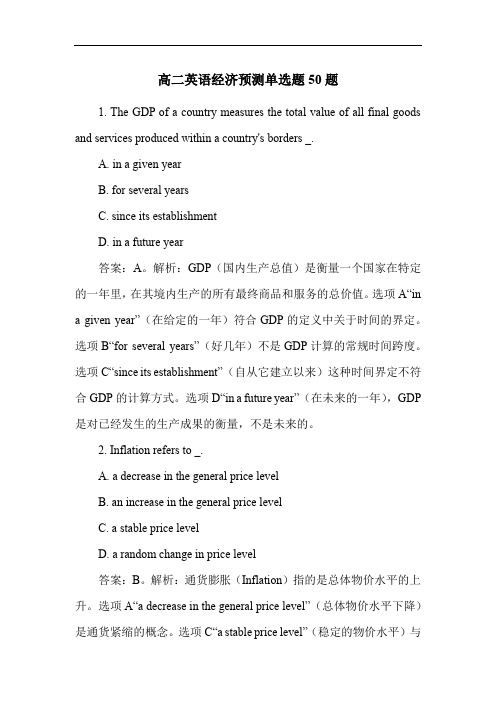

高二英语经济预测单选题50题

高二英语经济预测单选题50题1. The GDP of a country measures the total value of all final goods and services produced within a country's borders _.A. in a given yearB. for several yearsC. since its establishmentD. in a future year答案:A。

解析:GDP(国内生产总值)是衡量一个国家在特定的一年里,在其境内生产的所有最终商品和服务的总价值。

选项A“in a given year” 在给定的一年)符合GDP的定义中关于时间的界定。

选项B“for several years” 好几年)不是GDP计算的常规时间跨度。

选项C“since its establishment”(自从它建立以来)这种时间界定不符合GDP的计算方式。

选项D“in a future year”(在未来的一年),GDP 是对已经发生的生产成果的衡量,不是未来的。

2. Inflation refers to _.A. a decrease in the general price levelB. an increase in the general price levelC. a stable price levelD. a random change in price level答案:B。

解析:通货膨胀(Inflation)指的是总体物价水平的上升。

选项A“a decrease in the general price level” 总体物价水平下降)是通货紧缩的概念。

选项C“a stable price level”( 稳定的物价水平)与通货膨胀概念相悖。

选项D“a random change in price level”(物价水平随机变化)没有准确表达通货膨胀是物价上升这一概念。

小学下册D卷英语第2单元测验卷(含答案)

小学下册英语第2单元测验卷(含答案)英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.The capital of Japan is __________.2.Iron reacts with oxygen to form _______.3.The teacher is _____ (kind/strict) to us.4. A shooting star is actually a _______ that burns up in the atmosphere.5.The chemical symbol for francium is ______.6.My ______ loves to explore new technologies.7.I can use it to ______ (动词) new games. Sometimes, I pretend it is a ______ (角色).8.My dad loves __________ (历史) and shares stories with us.9.The ________ is a famous painting by Leonardo da Vinci.10.The Earth’s shape is not a perfect sphere; it is an ______.11.The _____ (种子) will grow into a new plant.12.The __________ is a famous beach destination in Florida. (迈阿密)13.The penguin is a flightless ______ (鸟) that swims well.14.I enjoy ______ with my friends at the mall. (hanging out)15.The __________ (洞穴) is dark and mysterious.16.I see a ___ (cloud/sky) above.17.The rabbit is ___ (nibbling) on some grass.18.My favorite food is _______.19.I can ________ my toys.20.The country known for its pyramids is ________ (埃及).21.The children are _____ in the classroom. (quiet)22._____ (环境) plays a big role in plant health.23. A __________ is a region known for its cultural heritage.24.The _______ (小狐狸) is quick and clever.25.Chemical engineering involves applying principles of chemistry to design processes for producing _____.26.I like to _____ (捡) shells.27.The chemical symbol for chlorine is __________.28.My grandparents love to ____.29.We need to ___ (clean) our room.30.On weekends, we often visit the _________ (玩具店) to look for new _________ (玩具).31.The chemical formula for ethanol is _____.32.The __________ is a zone of contact between two different rock types.33.Hydraulic systems use fluids to transmit ______.34.What is the name of the longest river in the world?A. AmazonB. NileC. MississippiD. Yangtze答案:B35.My favorite _________ (玩具) teaches me about science.36.We are learning about ___. (plants, eats, sleeps)37.The kitten plays with a _________. (球)38.What is the name of the process plants use to make food from sunlight?A. RespirationB. PhotosynthesisC. FermentationD. Decomposition答案:B39.I see a _____ (狮子) at the zoo.40.The _____ (花期) varies among different plants.41.The __________ (历史的图景) paints a broad picture.42. A ____(community newsletter) informs residents of events and resources.43.Mars has the largest volcano in the ______.44.The city of Honiara is the capital of _______.45.biogeography) studies the distribution of species. The ____46._____ (种植) vegetables is rewarding and fun.47.What is the opposite of "hot"?A. WarmB. CoolC. ColdD. Scorching答案: C48.My friend is a _____ (摄影师) who captures moments.49. A cat's whiskers help it sense ______ (环境).50.The chemical formula for copper(I) oxide is _____.51.Mulching helps to retain ______ in the soil. (覆盖物有助于保持土壤中的水分。

小学下册第13次英语第6单元真题(含答案)

小学下册英语第6单元真题(含答案)英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.What type of animal is a parrot?A. FishB. MammalC. BirdD. Reptile答案:C2.What do we call a young lion?A. PupB. CubC. KitD. Fawn答案:B.Cub3.The __________ (空气质量) can be improved with more plants.4.How many wheels does a bicycle have?A. OneB. TwoC. ThreeD. Four答案:B5.Metalloids have properties of both ________ and nonmetals.6.She is _____ (making) a cake.7.We can _____ (harvest) crops in the fall.8.The cat is chasing a _____.9.My dad is a __________. (工程师)10.The squirrel collects acorns in ________________ (秋天).11. A shadow is created when light is ______ by an object.12. A puppy needs ______ (训练) to learn tricks.13. A mixture that can be separated into its components is called a ______.14.An oxidizing agent is a substance that can accept _____.15. A wild boar has sharp ______ (牙齿).16.He is a coach, ______ (他是一名教练), training young athletes.17.My favorite _____ is a cuddly bear.18.What do you call a person who travels in space?A. AstronautB. PilotC. ScientistD. Engineer答案: A19.__________ are compounds that contain carbon.20.The capital of Egypt is _____ (92).21.I enjoy making ______ for my family.22.What is the opposite of "hot"?A. WarmB. CoolC. ColdD. Scorching答案: C23.The chemical formula for manganese dioxide is _______.24.Chinchillas have very soft ________________ (毛发).25.Cats can see well in ______ light.26.What is the sound of a cow?A. BarkB. MeowC. MooD. Quack答案:C27.The ____ is small and can often be found in flower beds.28.She takes care of her ________.29.The wind can be very ______ (强烈) sometimes.30.The _______ of a swing is caused by gravity.31.I have a toy _______ that spins and plays music when you press a button.32.My uncle takes me fishing ____.33.What is the name of the fairy tale character who lost her glass slipper?A. RapunzelB. CinderellaC. Snow WhiteD. Belle答案:B34.The dog is ______ by my side. (sitting)35. A __________ is an area of land that is very dry.36.Planting flowers can improve local ______ (生态系统).37. A __________ is a famous site for outdoor festivals.38.I love to design my own _________ (玩具) for my friends.39.I often host a ________ (名词) day at home where friends can bring their toys.40.This ________ (玩具) helps improve my skills.41.The tortoise can live for over a _______ (百年).42.In a chemical reaction, substances change into new __________.43.An insulator prevents the flow of ______ (electricity).44.The ______ is a talented writer.45.古代玛雅文明以其________ (calendar) 和建筑而闻名。

哥本哈根协议-英文版

Declaration of the European Ministers of Vocational Education and Training,and the European Commission,convened in Copenhagen on 29 and 30 November 2002, on enhanced European cooperation in vocational education and training“The Copenhagen Declaration”Over the years co-operation at European level within education and training has come to play a decisive role in creating the future European society.Economic and social developments in Europe over the last decade have increasingly underlined the need for a European dimension to education and training. Furthermore, the transition towards a knowledge based economy capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion brings new chal-lenges to the development of human resources.The enlargement of the European Union adds a new dimension and a number of challenges, opportunities and requirements to the work in the field of education and training. It is particularly important that acceding member states should be integrated as partners in future cooperation on education and training initiatives at European level from the very beginning.The successive development of the European education and training programmes has been a key factor for im-proving cooperation at European level.The Bologna declaration on higher education in June 1999 marked the introduction of a new enhanced Euro-pean cooperation in this area.The Lisbon European Council in March 2000 recognised the important role of education as an integral part of economic and social policies, as an instrument for strengthening Europe's competitive power worldwide, and as a guarantee for ensuring the cohesion of our societies and the full development of its citizens. The European Council set the strategic objective for the European Union to become the world’s most dynamic knowledge-based economy. The development of high quality vocational education and training is a crucial and integral part of this strategy, notably in terms of promoting social inclusion, cohesion, mobility, employability and competi-tiveness.The report on the 'Concrete Future Objectives of Education and Training Systems', endorsed by the Stockholm European Council in March 2001, identified new areas for joint actions at European level in order to achieve the goals set at the Lisbon European Council. These areas are based on the three strategic objectives of the report;i.e. improving the quality and effectiveness of education and training systems in the European Union, facilitating access for all to education and training systems, and opening up education and training systems to the wider world.In Barcelona, in March 2002 the European Council endorsed the Work Programme on the follow-up of the Objectives Report calling for European education and training to become a world quality reference by 2010. Furthermore, it called for further action to introduce instruments to ensure the transparency of diplomas and qualifications, including promoting action similar to the Bologna-process, but adapted to the field of vocational education and training.In response to the Barcelona mandate, the Council of the European Union (Education, Youth and Culture) adopted on 12 November 2002 a Resolution on enhanced cooperation in vocational education and training. This resolution invites the Member States, and the Commission, within the framework of their responsibilities, to involve the candidate countries and the EFTA-EEA countries, as well as the social partners, in promoting an increased cooperation in vocational education and training.Strategies for lifelong learning and mobility are essential to promote employability, active citizenship, social in-clusion and personal development1. Developing a knowledge based Europe and ensuring that the European labour market is open to all is a major challenge to the vocational educational and training systems in Europe and to all actors involved. The same is true of the need for these systems to continuously adapt to new developments and changing demands of society. An enhanced cooperation in vocational education and training will be an im-portant contribution towards ensuring a successful enlargement of the European Union and fulfilling the objec-tives identified by the European Council in Lisbon. Cedefop and the European Training Foundation are impor-tant bodies for supporting this cooperation.The vital role of the social partners in the socio-economic development is reflected both in the context of the European social dialogue and the European Social Partners framework of actions for the lifelong development of competences and qualifications, agreed in March 2002. The social partners play an indispensable role in the development, validation and recognition of vocational competences and qualifications at all levels and are part-ners in the promotion of an enhanced cooperation in this area.The following main priorities will be pursued through enhanced cooperation in vocational education and training: 2On the basis of these priorities we aim to increase voluntary cooperation in vocational education and training, in order to promote mutual trust, transparency and recognition of competences and qualifications, and thereby establishing a basis for increasing mobility and facilitating access to lifelong learning.European dimension•Strengthening the European dimension in vocational education and training with the aim of improving closer cooperation in order to facilitate and promote mobility and the development of inter-institutional cooperation, partnerships and other transnational initiatives, all in order to raise the profile of the Euro-pean education and training area in an international context so that Europe will be recognised as aworld-wide reference for learners.Transparency, information and guidance•Increasing transparency in vocational education and training through the implementation and rationali-zation of information tools and networks, including the integration of existing instruments such as the European CV, certificate and diploma supplements, the Common European framework of reference for languages and the EUROPASS into one single framework.•Strengthening policies, systems and practices that support information, guidance and counselling in the Member States, at all levels of education, training and employment, particularly on issues concerning ac-cess to learning, vocational education and training, and the transferability and recognition of compe-tences and qualifications, in order to support occupational and geographical mobility of citizens inEurope.Recognition of competences and qualifications•Investigating how transparency, comparability, transferability and recognition of competences and/or qualifications, between different countries and at different levels, could be promoted by developing ref-erence levels, common principles for certification, and common measures, including a credit transfersystem for vocational education and training•Increasing support to the development of competences and qualifications at sectoral level, by reinforc-ing cooperation and co-ordination especially involving the social partners. Several initiatives on a Com-munity, bilateral and multilateral basis, including those already identified in various sectors aiming atmutually recognised qualifications, illustrate this approach.1Priorities identified in the Resolution on lifelong learning adopted by the Council of the European Union (Education and Youth) on 27 June 20022Priorities identified in the Resolution on the promotion of enhanced European co-operation on vocational education and training approved by the Council of the European Union (Education, Youth and Culture) on 12 November 2002•Developing a set of common principles regarding validation of non-formal and informal learning with the aim of ensuring greater compatibility between approaches in different countries and at different lev-els.Quality assurance•Promoting cooperation in quality assurance with particular focus on exchange of models and methods, as well as common criteria and principles for quality in vocational education and training.•Giving attention to the learning needs of teachers and trainers within all forms of vocational education and training.The following principles will underpin enhanced cooperation in vocational education and training:•Cooperation should be based on the target of 2010, set by the European Council in accordance with the detailed work programme and the follow-up of the Objectives report in order to ensure coherence with the objectives set by the Council of the European Union (Education, Youth and Culture).•Measures should be voluntary and principally developed through bottom-up cooperation.•Initiatives must be focused on the needs of citizens and user organisations.•Cooperation should be inclusive and involve Member States, the Commission, candidate countries, EFTA-EEA countries and the social partners.The follow-up of this declaration should be pursued as follows to ensure an effective and successful implementation of an enhanced European cooperation in vocational education and training:1.Implementation of the enhanced cooperation in vocational education and training shall be a graduallyintegrated part of the follow-up of the objectives report. The Commission will reflect this integrated ap-proach in its reporting to the Council of the European Union (Education, Youth and Culture) within the timetable already decided for the work of the objectives report. The ambition is to fully integrate thefollow-up work of the enhanced co-operation in vocational education and training in the follow-up ofthe objectives report.2.The existing Commission working group, which will be given a similar status to that of the workinggroups within the follow-up of the objectives report, in future including Member States, EFTA-EEAcountries, candidate countries and the European social partners, will continue to work in order to ensure effective implementation and coordination of the enhanced cooperation in vocational education andtraining. The informal meetings of the Directors General for Vocational Training, which contributed to launching this initiative in Bruges 2001, will play an important role in focusing and animating the follow-up work.3.Within this framework the initial focus between now and 2004 will be on concrete areas where work isalready in progress, i.e. development of a single transparency framework, credit transfer in vocationaleducation and training and development of quality tools. Other areas, which will be immediately in-cluded as a fully integrated part of the work of the follow-up of the objectives report organised in eight working groups and an indicator group, will be lifelong guidance, non-formal learning and training ofteachers and trainers in vocational education and training. The Commission will include progress onthese actions in its report mentioned in paragraph 1.The ministers responsible for vocational education and training and the European Commission have con-firmed the necessity to undertake the objectives and priorities for actions set out in this declaration and to participate in the framework for an enhanced cooperation in vocational education and training, including the social partners. A meeting in two years time will be held to review progress and give advice on priorities and strategies.。

金融专题英语文献

Int.Fin.Markets,Inst.and Money 38(2015)42–64Contents lists available at ScienceDirectJournal of International Financial Markets,Institutions &Money journal homepage:/locate/intfin Does stock market liquidity explain real economic activity?New evidence from two large European stock marketsNicholas Apergis a ,Panagiotis G.Artikis b ,∗,Dimitrios Kyriazis caBusiness School,Northumbria University,Newcastle upon Tyne NE18ST,UK bDepartment of Business Administration,University of Piraeus,80Karaoli &Dimitriou Street,18534Piraeus,Greece c Department of Banking and Financial Management,University of Piraeus,80Karaoli &Dimitriou Street,18534Piraeus,Greece a r t i c l e i n f o Article history:Received 18December 2013Accepted 14May 2015Available online 19May 2015Keywords:Stock market liquidityEconomic conditionsUK marketGermany market a b s t r a c t This paper examines the relationship between stock market liquidity,which proxies for the implicit cost of trading shares,with macroeconomic conditions.We provide evidence that stock market liquidity contains strong and robust information about the condition of the economy for both the UK and Germany in the presence of well-established leading indicators.Our findings exemplify the importance of small cap firms’liquidity in explaining the state of the economy and support the “flight-to-quality argument”.Finally,the empirical findings show that there is not any differential role of liquidity in explaining the course of macroeconomic variables between a capital market and a bank-oriented economy.©2015Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.1.IntroductionThe existence of an illiquidity risk premium is well documented in the literature,in the sense that illiquid stocks command higher expected returns than liquid stocks (e.g.,Amihud and Mendelson,1986;Amihud,2002;Chordia et al.,2005;Kempf and Mayston,2008;Pastor and Stambaugh,2003;Acharya and Pedersen,2005;Papavassiliou,2013).The liquidity shock hypothesis argues that sudden drops in asset markets liquidity cause equity prices to fall and the price of liquid assets to rise (Kiyotaki and Moore,2008).Moreover,in a world where firms have to cope with financing constraints on their investments,this fall in equity prices reduces the funds for investments a firm can raise by issuing equity and/or using equity as collateral in borrowing.As a result,investments fall,output follows and a recession starts.The liquidity shock hypothesis has received wide attention because of its immediate policy implications.If unexpected fluctuations in equity liquidity are the cause of economic growth,then a government can attenuate the economic performance by making the supply of liquid assets countercyclical.At the onset of a recession,a government can use liquid assets to buy up some of the illiquid equity to prevent equity prices from falling precipitously.The increase in the supply of liquid assets relaxes firms’financing constraints,while the stabilization of equity prices further improves firms’ability to use the equity market to finance their investment projects with lower cost of capital,thus,increasing the return on the projects they adopt.These policy implications seem to provide a justification for the large and repeated injections of liquidity by the US Federal Reserve System as well as other central banks over the recessionary period 2008–2009.The goal of this study is to investigate the information content of stock market liquidity,based on firm-level data,to explain the course of economic activity,after controlling for a number of equity (i.e.,market risk premium,stock market ∗Corresponding author.Tel.:+302104142200.E-mail addresses:Nicholas.apergis@ (N.Apergis),partikis@unipi.gr (P.G.Artikis),dkyr@unipi.gr (D.Kyriazis)./10.1016/j.intfin.2015.05.0021042-4431/©2015Elsevier B.V.All rights reserved.N.Apergis et al./Int.Fin.Markets,Inst.and Money38(2015)42–6443 volatility)and non-equity(i.e.,housing starts,term spread,short-term interest rates,default spread)factors.In doing so,we apply alternative liquidity proxies to different indicators of economic activity,while we utilize a sample of stocks originating from two of the largest European stock markets,i.e.the London Stock Exchange and the Deutsche Börse,spanning the period 1994to2011and1997to2011,respectively.The rationale for examining whether stock market liquidity can act as a leading indicator for economic activity is threefold. First,according to the“flight to quality”hypothesis put forward by Longstaff(2004),investors tend to shift their portfolios to more liquid securities in turbulent times of economic activity.Second,liquidity can affect economic activity through certain investment channels,since a liquid secondary market may facilitate investments in productive long-run projects(Levine, 1991).Third,Brunnermeier and Pedersen(2009)show that during periods of economic downturn,both a lack of assets’markets liquidity and reducedfinancial intermediaries’funding liquidity lead to liquidity spirals.The relationship between stock market liquidity and economic activity has attracted limited attention in the literature and certain studies have focused either on US data or on small markets,such as Norway and Switzerland.Beber et al.(2011)find that an orderflow portfolio,based on cross-sector movements,can predict the state of the macro economy.In a similar study,Kaul and Kayacetin(2009)show that two alternative orderflow measures can predict GDP and industrial production growth.Næs et al.(2011)use alternative liquidity measures,both for the US and Norway,and document that stock market liquidity can serve as a leading indicator for the macroeconomic variables.Meichle et al.(2011)find that stock market liquidity is the main predictor for economic activity for Switzerland over the period1990–2010.More recently,Florackis et al.(2014a)find that stock market illiquidity can better explain and forecast the future UK GDP growth than any other variable usually examined(i.e.,term spread,short-term interest rates and real money supply)and confirm a statistically significant negative association between these two variables.Taking into account that the association between stock market liquidity and macro variables has attracted limited interest in the literature,further evidence is needed in terms of market selection,methodological approaches and the sample period, in order to fully understand this association.The present study contributes to the literature towards this end in a number of ways.It is clear from the above discussion that the relationship between stock market liquidity and macro variables has been examined mainly in a US setting.Thus,we shed further light in the literature with the use,for thefirst time,of data from two large European stock markets,the UK and Germany.The London Stock Exchange(LSE)and the German stock exchange (Deutsche Börse)are selected on the grounds that although they are major markets of great international importance and interest,ranking among the world’s largest in terms of number offirms listed and total market capitalization,they have a larger liquidity effect and have not been cross-examined in the previous empirical literature.Another significant novelty of the present paper is that for thefirst time we provide an interesting comparison of the information content of stock market liquidity for economic activity between a capital market oriented economy(UK)and a banking oriented economy(Germany).It has been argued1that the type of thefinancial system(i.e.,market vs.bank based)influences economic growth,while a number of empirical works show that the distinction is irrelevant,at least for the case of developed and mature markets(Beck and Levine,2002).The issue examined in our study is whether we should expect that stock market liquidity could behave differently in a bank-based system,such as in Germany,than in a market-based system,such as in the UK,based on the fact that liquidity is explicitly used as the main explanatory variable of the macroeconomic environment.Stock markets provide direct funding to investors,while banks and otherfinancial institutions,as intermediaries,provide indirect funding to them.Therefore,we could argue that stock markets provide an easier and quicker transmission of liquidity to investors and to the real economy than banks when the economy is thriving, but an equally faster negative adjustment of liquidity when the economy is plunging into recession.In terms of methodological approaches,the present study differentiates from previous works in the area by examining alternative liquidity proxies.To this end,the paper makes use of alternatives definitions of liquidity as well as the Instru-mental Variable(IV)methodological approach,which takes cares of any endogeneity bias problems.The study focuses on the simpler non-sophisticated liquidity proxies,which,however,are the ones used by practitioners and investment profes-sionals that do not require restrictive assumptions as the more sophisticated proxies do.Moreover,the present study differs from those by Næs et al.(2011),Meichle et al.(2011)and Florackis et al.(2014a)by examining the information content of two liquidity measures,namely,the turnover and the volume of trading,to explain economic activity along with the relative spread and Amihud’s illiquidity ratio which have both been previously examined.We opt to use different liquidity proxies in order to fully examine on how various aspects of liquidity affect economic conditions and to provide robustness to our results.1Stiglitz(1985)and Bhide(1993)claim that stock markets do not produce the same improvement in resource allocation and corporate governance as banks.Those who favour the market-based system argue against the role of banks for extracting informational rents fromfirms and reducing incentives to undertake risky and innovative but profitable projects(e.g.,Rajan,1992;Morck and Nakamura,1999).La Porta et al.(2002)also argue against the role of state-owned banks for having political goals in the process of supplying credit to rather traditional labour intensive industries,than to innovative and truly strategic ones.However,Boot and Thakor(1997)show that banks facilitate better the goal of economic growth in emergingfinancial systems and stock markets do better in maturefinancial systems.In addition,Allen and Gale(2000)present evidence that both banks and markets provide different financial services,while economies at different stages of economic development require different mixtures offinancial services to operate effectively.A similarfinding is provided by Tadesse(2002).Beck and Levine(2002)do notfind any evidence that the type offinancial structure really matters for industry growth and the efficient allocation of capital across industries.44N.Apergis et al./Int.Fin.Markets,Inst.and Money38(2015)42–64For robustness purposes,we have also included for thefirst time an additional control variable,i.e.,housing starts,apart from the term spread,market risk premium,stock market volatility,short-term interest rate and default spread,already used in previous studies.The importance of housing starts in explaining macroeconomic conditions has been documented extensively in the literature(Green,1997;Coulson and Kim,2000;Hui and Yiu,2003;Iacoviello,2003).A housing start is generally counted as the excavation of the foundation and indicates advance demand in the housing sector.Housing starts, on top of being a leading indicator of strength in the construction industry,are also an important leading economic indicator, due to their extensive spillover benefits to the other sectors(i.e.,retail,manufacturing,utilities,labour markets),since new homes need to be equipped and furnished from scratch(Karamujic,2013).Finally,as far as the sample period is concerned,the present study is implemented in a quite unique and interesting time frame,i.e.,1994–2011,since it covers both periods of“bull”and“bear”equity markets and periods of economic expansion (1994–2002,2004–2008,2010–2011)and economic downturn(2002–2004,2008–2010).In particular,the second period of recession was quite severe,following the burst of the real estate bubble in the US,which triggered the globalfinancial crisis that drained liquidity fromfinancial markets worldwide.Thus,our empirical models are tested across a number of different economic and stock market backgrounds and the implications of our results may be of particular interest not only for academics,but also for investors(i.e.,retail and institutional),policy makers and regulators.To foreshadow the results,they show that there is a strong relationship between stock market liquidity and the state of the macro economy in both countries under investigation.When there is drainage of stock market liquidity and the implicit costs for trading stocks increase,then investors should be anticipating lower GDP,investments and consumption and higher unemployment rates.Finally,the liquidity of small stock companies is found to have a larger impact on the macro variables investigated across both countries.This important result corroborates thefindings of Amihud(2002)and more recently of Cakici and Tan(2014)and may have serious implications for investors and central banks’policies,since a large drop in the liquidity of smallfirms stocks gives a strong signal for the beginning of a recessionary period.As investors start switching from their positions on small cap stocks to government bonds or large cap stocks,central banks may increase promptly the money supply aiming to stimulate the real economy,avoiding plunging in a deep and prolonged recession.The empiricalfindings are expected to shed further light on the role of market liquidity in the growth process,especially, during turbulent periods like the recent recession,since liquidity is closely associated with both the market liquidity risk and the funding liquidity risk.Thefirst type of risk occurs as the market liquidity worsens and potential investors need to trade,while the second type is the risk where traders cannot fund their positions and are forced to unwind.This perverse situation is having significant effects on the real economy.However,systematic(market)liquidity can have serious repercussions not only for thefinancial system,but also for the real economy,since any disruptions can lead tofinancial crises,which damagefinancial stability,resources allocation and have a negative impact on the real economy(Ferguson et al.,2007).Therefore,the presence of this downward liquidity spiral recommends that policy makers have to improve the funding liquidity of investors in the market,especially that of banking institutions.The rest of the paper is organized as follows.Section2presents a pertinent literature review,while Section3defines the liquidity proxies along with a number of other control variables and describes the methodology employed.Section4 presents and discusses the results obtained from the empirical analysis.Finally,Section5concludes the paper.2.Literature reviewAcademic research has extensively examined the relationship between asset prices(e.g.,interest rates,term spreads, stock returns,and exchange rates)and real economic indicators.Estrella and Hardouvelis(1991)show that the yield curve can predict future developments in real economic activity,while others highlight the role of the term spreads(i.e.,the difference between a10-year government bond and an uncovered short-term interest rate)in predicting future turning points in the economy(Estrella and Mishkin,1998;Rudebusch and Williams,2009;Wright,2006).The rationale of using financial market variables as leading indicators for economic activity is threefold:(a)investors convey the information about the future state of the economy by tradingfinancial securities and changing their relative price over time,based on new information arrivals(Beber et al.,2011),(b)they are observed and not estimated through a theoretical model,and(c)they are instantly and easily available at a high frequency to all market participants and analysts(Meichle et al.,2011).However, Stock and Watson(2003),by carrying out their empirical study for seven OECD countries spanning the period1959–1999, conclude that the link betweenfinancial market variables and real economic activity is not uniform and stable across all countries and periods.Asset liquidity,which is the ability to sell an investment instantly and at a price close to its current market price,can be thought of as the channel through which information about macroeconomic variables is incorporated into asset prices.A number of research studies in the literature of market microstructure have documented a positive link between a security’s illiquidity and its expected returns,which establishes the presence of an illiquidity risk factor and the associated illiquid-ity risk premium(Amihud and Mendelson,1986;Amihud,2002;Jones,2002;Pastor and Stambaugh,2003;Acharya and Pedersen,2005;Guo et al.,2011).Taking into account on one hand that asset prices can forecast real economic indicators and on the other that asset liquidity can explain asset prices changes,this could imply that asset liquidity contains incremental information about macroeconomic conditions.One possible explanation could be the role of the“flight to liquidity”or“flight to quality”,N.Apergis et al./Int.Fin.Markets,Inst.and Money38(2015)42–6445 put forward by Longstaff(2004)who shows that investors prefer to invest in US Treasury bonds which are more liquid in comparison with Refcorp2bonds,although both of them carry the same credit risk.In fact,Longstaff(2004)discovers that about10%to15%of T-Bill prices can be attributed to their large liquidity premia.Levine and Zervos(1998)provide an explanation by showing how stock market liquidity affects real economic activity via certain investment channels.They empirically establish a statistically significant positive relationship between stock market liquidity and current and future rates of economic growth in several countries,after controlling for political and economic factors.A different explanation is provided by Brunnermeier and Pedersen(2009)who develop a model that describes a mutually dependent relationship between assets market liquidity andfinancial intermediaries’funding liquidity.In particular,the model explains,among other things,how a reduced funding liquidity in periods offinancial downturns can lead to a“flight to quality”,i.e.,that financial intermediaries change their liquidity provision to stocks with low margin requirements.A similar path has been followed by Rösch and Kaserer(2012)who provide evidence consistent with the theoretical model of Brunnermeier and Pedersen(2009).This“flight to quality”argument may also be associated with the size offirms in terms of market value.Small capitalization firms suffer more than large capitalizationfirms during an economic downturn,while they prosper more when the economy is expanding(Perez-Quiros and Timmermann,2000;Switzer,2010).In addition,small cap stocks are usually less liquid than large cap stocks.Chordia et al.(2004)witness an increase in aggregate market liquidity over time,which has been more pronounced for large than for smallfirms.During a recession,investors move out more heavily from small cap stocks that perform poorly and are less liquid than from large cap stocks.Chordia et al.(2004)also establish that average daily changes in liquidity exert a heterogeneous effect on stock returns,depending on thefirm size,since the liquidity of smallfirms varies more on a daily basis than that of largefirms.Thus,the liquidity variation of small cap stocks is larger than the variation of large cap stocks.Næs et al.(2011)document,using US data,that the liquidity of small capfirms is more informative about future macro fundamentals than the liquidity of large capfirms.They attribute this effect to the tendency of investors to move outfirst from small cap stocks,either because of changing expectations about economic environment or due to increased funding liquidity constraints.They confirm this by exhibiting a much larger drop in trading volume of small cap stocks before a recession,than that observed for largefirm stocks.In a more recent study,Cakici and Tan(2014),investigating the effect of value3and momentum variables in23developed international markets,find that value stock returns are lower prior to a recession and this is rather due to a deterioration of funding liquidity and not due to poor market liquidity.Although the literature provides a number of different explanations of why stock market liquidity should be related to economic growth,the relationship per se between aggregate market liquidity and the future economic conditions has attracted less interest from academic researchers.First,a number of studies,closely related to our work,examine whether macroeconomic factors affect stock market liquidity.More specifically,Fujimoto(2003)and Söderberg(2008)examine the in-sample and out-of sample forecasting ability of various macroeconomic variables on liquidity,but do not consider that this relationship can go in the opposite way.Lu and Glascock(2010)show that the pricing component of liquidity can be significantly affected by a number of macroeconomic factors and,in particular,the growth in industrial production and when the economy digs deeper into recession.In a somewhat different approach,Gibson and Mougeot(2004)document that a time-varying liquidity risk premium in the US stock market can be linked with a recession index.In another strand of the literature,there are studies that examine equity-market orderflows,which are closely related to stock market liquidity.Specifically,Kaul and Kayacetin(2009)examine the information content of two different measures of aggregate equity-market orderflows for future macroeconomic fundamentals and expected stock market returns.They discover that both can predict future growth rates of industrial production and real GDP,up to four quarters ahead,and this result is robust even after controlling for variables associated with common equity pricing factors.Beber et al.(2011) address how the issue of orderflows movements by investors across equity sectors is related to current and future economic conditions.Their results show that large-sized active orderflows in the materials sector can forecast an expanding economy, while large-sized active orderflows into consumer discretionary,financials,and telecommunications forecast a contracting economy.In the light of the recent globalfinancial crisis,the reduced funding liquidity and the decreased orderflow movements from market makers are addressed by three papers that directly explore the issue of stock market liquidity and the real economy.Næs et al.(2011)employ US and Norwegian stock market data and display that stock market liquidity(in terms of the trading costs of equities)can be used as a powerful“leading indicator”of the real economy,even after controlling for the presence of other variables,which are extensively used in previous relevant empirical studies for predicting business cycles. Their study makes use of a large US dataset over the period1947–2008along with a unique dataset for Norway spanning the period1990–2006.The authors also discover an important relationship between the size of thefirms and the information content of liquidity in predicting GDP growth,afinding that is consistent with the“flight-to-quality”effect.Meichle et al.(2011)claim that for a small open economy,i.e.,the Swiss economy,asset price factors,such as term spreads,are not entirely appropriate to predict economic growth,as long as they are severely affected by exogenous factors2Refcorp is a government agency created by the Financial Institutions Reform,Recovery,and Enforcement Act of1989(FIRREA).The principal of these bonds is fully collateralized by Treasury bonds,while full payment of coupons is guaranteed by the Treasury under the provisions of FIRREA.3It has been well established(e.g.,Fama and French,1992,1996;Lakonishok et al.,1994)that value stocks which are described as stocks with high ratios to fundamentals(e.g.,book value,earnings per share,cashflows,etc)relative to stock price tend to over perform stocks with correspondingly low ratios.46N.Apergis et al./Int.Fin.Markets,Inst.and Money38(2015)42–64(i.e.,co-movements of international long-term interest rates).They alsofind that over the last two decades(1990–2010) stock market liquidity is a better predictor of economic activity than term spreads.However,this picture is reversed if the entire sample period(1975–2010)is considered,with term spreads gaining predictive power(Rudebusch and Williams, 2009).Thisfinding also confirms the results by Stock and Watson(2003)about the erratic and time varying behaviour of asset prices as predictors of real economic activity.Finally,Florackis et al.(2014a)in a study,which focuses only on the UK market and considers only macroeconomic activity in terms of GDP growth,examine the explanatory power of stock market liquidity in forecasting the real UK.GDP growth over the period1989–2012.By using standard linear and nonlinear models,theyfind a statistically significant negative relationship between stock market illiquidity and future growth in GDP of UK,even after including the usual explanatory variables(e.g.,term spreads,short-term interest rates and real money supply/divisia).They also show that that the effect of both market illiquidity and divisia money becomes stronger during periods of illiquid market conditions and poor economic growth.Furthermore,through an out-of-sample forecasting analysis they discover that a regime switching model of illiquid vs.liquid market conditions predicts UK growth in GDP better than any other model,even the one published by the Bank of England’s inflation report.3.Methodology3.1.Liquidity proxies and samplefirmsAs far as the liquidity measures are concerned,there are numerous indicators developed in the literature that attempt to measure stock market liquidity.The high frequency liquidity measures require intraday data on bid/ask quotes,orderflows, volume of trades etc.,which are not available for a long period of time.Thus,we adopt low frequency liquidity measures that can be estimated with daily data,which are available for longer time periods.Furthermore,since liquidity is an unobservable characteristic of an asset market,which cannot be captured in a single measure,it is desirable to examine the issue with the use of a variety of liquidity measures.We use four alternative liquidity measures:(a)the Amihud(2002)illiquidity ratio(ILR),(b)the relative spread(RS),(c) turnover(TUR)and(d)the volume of trading(VTR).According to Goyenko and Ukhov(2009)and Goyenko et al.(2009),the first two liquidity proxies capture the spread cost and the price impact when estimated with daily data.The rationale for using turnover and volume of trading is twofold.First,they are simple and straightforward to calculate and do not require a large amount of data or restrictive assumptions as the more sophisticated proxies,such as the Lesmond et al.(1999)and Roll (1984)liquidity measures.Second,they are the most commonly used liquidity measures by practitioners and investment professionals and have been previously used in the pertinent literature in other aspects of liquidity,such as in asset pricing.Amihud’s(2002)illiquidity ratio(ILR)is the ratio of absolute stock returns to monetary volume on a daily basis,displaying how much prices move for each monetary unit of trades.The cost associated with larger trades is more accurately captured in the price impact of a trade.Hasbrouck(2009)shows that the ILR is the best available price-impact proxy constructed from daily data.Moreover,Amihud(2002)shows that the ILR is positively and significantly related to both the price impact and thefixed cost component estimates defined by Brennan and Subrahmanyam(1996).The ILR captures the sensitivity of prices to trading volumes,since it is a measure of the elasticity dimension of liquidity.The ILR is calculated as:ILR i,T=1D TTt=1R i,tVOL i,t(1)where D T is the number of observations within a time window T,|R i,t|is the absolute return at day t for stock i,and VOL i,t is the trading volume in monetary values at day t for stock i.The ILR essentially provides an illiquidity measure,since a high value indicates low liquidity(i.e.,a high price impact of trades).Moreover,a high price impact suggests that the market depth is low and a smaller volume is needed to move that price.A market participant who wishes tofill his order immediately must be willing to pay the ask price for a buy order and collect the bid price for a sell order.The difference between the two prices is the bid-ask spread,which reflects the cost of immediacy.Thus,the bid-ask is a spread cost,which is observed in both dealer and limit order markets.In the present study, we estimate a market-wide proportional spread measure,the relative bid/ask spread(RS).It is estimated as the ratio of the quoted spread(i.e.,the differences between the best ask and bid quotes)over the midpoint price(i.e.,the averages of the best ask and bid quotes)on a daily basis:RS i,T=1D TTt=1P ASKi,t−P BIDi,tP ASKi,t+P BIDi,t/2(2)where P ASK i,t and P BID i,t are the ask and bid price,respectively,at day t for stock i.The RS provides a relative measure of trading costs and proxies for a percentage two-way transaction cost,i.e.,what fraction of the price needs to be paid to“cross”from the bid to the ask price,or vice versa.Similarly to the case of the ILR,the RS is an illiquidity measure,since a high spread indicates an illiquid market where the implicit costs of trading are large.。

2023年12月英语六级听力原文及参考答案

2023年12月英语六级听力原文及参考答案听力稿原文section AConversation 1气候变化和全球经济发展W: Professor Henderson could you give us a brief overview of what you do, where you work and your main area of research?M: Well the Center for Climate Research where I work links the science of climate change to issues around economics and policy。

Some of our research is to do with the likely impacts of climate change and all of the associated risks。

W: And how strong is the evidence that climate change is happening that it‘s really something we need to be worried about。

M: Well most of the science of climate change particularly that to do with global warming is simply fact。

But other aspects of the science are less certain or at least more disputed。

And so we‘re really talking about risk what the economics tells us is thatit’s probably cheaper to avoid climate change to avoid the risk than it has to deal with the likely consequences。

欧洲主权债务危机英文共17页文档

2、What are the influences of the ESDC on China?

(disadvantages and advantages)

Over China’s foreign trade More money will leave China

Improve China’s structural transformation European overseas capital investment return Reconsider the local debt of China

欧洲主权债务危机英文

41、俯仰终宇宙,不乐复何如。 42、夏日长抱饥,寒夜无被眠。 43、不戚戚于贫贱,不汲汲于富贵。 44、欲言无予和,挥杯劝孤影。 45、盛年不重来,一日难再晨。及时 当勉励 ,岁月 不待人 。

优秀精品课件文档资 料

European Sovereign Debt Crisis and China

1、What’s European Sovereign Debt Crisis ? (the progress of the Crisis)

From late 2009, fears of a sovereign debt crisis developed among investors concerning some European states, intensifying in early 2010 and thereafter.

If potential lenders or bond purchasers begin to suspect that a government may fail to pay back its debt, they may demand a high interest rate in compensation for the risk of default. A dramatic rise in the interest rate faced by a government due to fear that it will fail to honor its debt is sometimes called a sovereign debt crisis.

2013年英二阅读第四篇

2013年英二阅读第四篇内容如下:Text4(1) Europe is not a gender-equality heaven. In particular, the corporate workplace will never be completely family—friendly until women are part of senior management decisions, and Europe’s top corporate-governance positions remain overwhelmingly male .indeed, women hold only 14 percent of positions on Europe corporate boards.(2) The Europe Union is now considering legislation to compel corporate boards to maintain a certain proportion of women-up to 60 percent. This proposed mandate was born of frustration. Last year, Europe Commission Vice President Viviane Reding issued a call to voluntary action. Reding invited corporations to sign up for gender balance goal of 40 percent female board membership. But her appeal was considered a failure: only 24 companies took it up.(3) Do we need quotas to ensure that women can continue to climb the corporate Ladder fairy as they balance work and family?4) “Personally, I don’t like quotas,”Reding said recently. “Buti like what the quotas do.”Quotas get action: they “open the way to equality and they break through the glass ceiling,”according to Reding, a result seen in France and other countries with legally binding provisions on placing women in top business positions.(5) I understand Reding’s reluctance-and her frustration. I don’tlike quotas either; they run counter to my belief in meritocracy, government by the capable. Bur, when one considers the obstacles to achieving the meritocratic ideal, it does look as if a fairer world must be temporarily ordered.(6) After all, four decades of evidence has now shown that corporations in Europe as the US are evading the meritocratic hiring and promotion of women to top position—no matter how much “soft pressure”is put upon them. When women do break through to the summit of corporate power--as, for example, Sheryl Sandberg recently did at Facebook—they attract massive attention precisely because they remain the exception to the rule.(7) If appropriate pubic policies were in place to help all women---whether CEOs or their children’s caregivers--and all families, Sandberg would be no more newsworthy than any other highly capable person living in a more just society.36. In the European corporate workplace, generally_____.[A] women take the lead[B] men have the final say[C] corporate governance is overwhelmed[D] senior management is family-friendly37. The European Union’s intended legislation is ________.[A] a reflection of gender balance[B] a response to Reding’s call[C] a reluctant choice[D] a voluntary action38. According to Reding, quotas may help women ______.[A] get top business positions[B] see through the glass ceiling[C] balance work and family[D] anticipate legal results39. The author’s attitude toward Reding’s appeal is one of _________.[A] skepticism[B] objectiveness[C] indifference[D] approval40. Women entering top management become headlines due to the lack of ______.[A] more social justice[B] massive media attention[C] suitable public policies[D] greater “soft pressure”。

2024年高二英语学科全球合作研究的合作机制构建分析单选题30题

2024年高二英语学科全球合作研究的合作机制构建分析单选题30题1.International cooperation is crucial for addressing global challenges. The ______ of different countries is essential.A.effortsanizationsC.cooperationsD.initiatives答案:B。

“国际合作对于应对全球挑战至关重要。

不同国家的组织是必不可少的。

”A 选项“efforts”努力;C 选项“cooperations”合作,此处与前文重复;D 选项“initiatives”倡议。

根据语境,这里强调不同国家的组织,所以选B。

2.Global cooperation requires strong ______ among nations.A.associationsB.partnershipsC.connectionsD.relationships答案:B。

“全球合作需要国家之间强大的伙伴关系。

”A 选项“associations”协会;C 选项“connections”联系;D 选项“relationships”关系,而伙伴关系更能体现全球合作的需求,所以选B。

3.The success of global cooperation depends on effective ______.A.coordinationsB.arrangementsanizationsD.plans答案:C。

“全球合作的成功取决于有效的组织。

”A 选项“coordinations”协调;B 选项“arrangements”安排;D 选项“plans”计划。

这里强调组织的重要性,所以选C。

4.In global cooperation, ______ play an important role in promoting common development.A.institutionspaniesC.factoriesD.schools答案:A。

产业组织理论参考教材及经典文献选读

《产业组织理论》参考教材及经典文献选读一、参考教材:1.廖进球主编:产业组织理论,上海财经大学出版社,2012年。

2.施马兰西、威利格:产业组织经济学手册(第1卷),经济科学出版社,2009年。

3.斯蒂芬•马丁:高级产业经济学,上海财经大学出版社,2003年。

4.泰勒尔:产业组织理论,中国人民大学出版社,1997年。

5.夏伊:产业组织理论与应用,清华大学出版社,2005年。

6.卡尔顿、佩洛夫:现代产业组织,中国人民大学出版社,2009年。

7.乔治·J·施蒂格勒:产业组织和政府管制,潘振民译,上海三联书店,1989年。