抑扬格

抑扬格

抑扬格五音步目录含义英文诗歌中用得最多的便是抑扬格,百分之九十的英文诗都是用抑扬格写成的。

其中又以抑扬格五音步居多。

要弄清什么是抑扬格五音步(lambic pentameter),要先知道什么音步和抑扬格。

音步我们知道凡是有两个以上音节的英文单词,都有重读音节与轻读音节之分,在一句话中,根据语法、语调、语意的要求,有些词也要重读,有些要轻读。

如he went to town to buy a book.. I’m glad to hear the news. 英文中有重读和轻读之分,重读的音节和轻读的音节,按一定模式配合起来,反复再现,组成诗句,听起来起伏跌宕,抑扬顿挫,就形成了诗歌的节奏。

多音节单词有重音和次重音,次重音根据节奏既可视为重读,也可视为轻读。

读下面这两句诗:Alone │she cuts │and binds│ the grain,And sings │a me│lancho│ly strain.这两行诗的重读与轻读的固定搭配模式是:轻——重。

在每行中再现四次,这样就形成了这两行诗的节奏。

某种固定的轻重搭配叫“音步”(foot),相当与乐谱中的“小节”。

一轻一重,就是这两行诗的音步。

一行诗中轻重搭配出现的次数叫音步数,这两行诗的音步数都是四,所以就称其为四音步诗。

抑扬格如果一个音步中有两个音节,前者为轻,后者为重,则这种音步叫抑扬格音步,其专业术语是(iamb, iambic.)。

轻读是“抑”,重读是“扬”,一轻一重,故称抑扬格。

英语中有大量的单词,其发音都是一轻一重,如adore, excite, above, around, appear, besides, attack, supply, believe, return等,所以用英语写诗,用抑扬格就很便利。

也就是说,抑扬格很符合英语的发音规律。

因此,在英文诗歌中用得最多的便是抑扬格,百分之九十的英文诗都是用抑扬格写成的。

前面的那两句诗就是抑扬格诗。

什么是五步抑扬格

什么是五步抑扬格?英诗简析音步(feet)音步是诗行中按一定规律出现的轻音节和重音节的不同组合成的韵律最小单位。

英语文字是重音----音节型语言,因此有轻读音节兴重音节之分,它们是形成英语特有的抑扬顿挫声韵节律的决定性因素。

这是英文和英语在语音方面的区别之一。

法语是音节型语言,音节没有轻重之分,法语韵律的最小单位就是音节,而非音步。

据统计﹕英诗中这种轻重音组音步﹔其余各种音步可以看作是从这五种衍生而出来的。

这五个音步是﹕抑扬格,扬抑格,抑抑扬格,扬抑抑格和扬扬格。

现述如下﹕1.抑格格音步(iambic foot, iambus) ,即轻格或短长格﹕一轻读音节后跟一个重读音节即构成抑扬格。

它是英语本身最基本的节奏单位,也是英诗的最重要、最常用的音步。

随便说一句话,其基本音步就是抑扬格,如﹕It’s time︱the chil︱dren went︱to bed. 这句话有四个抑扬格音步。

We’ll learn︱a poem︱by Keats, 有三个抑扬格音步。

The sym︱bols used︱in scan︱sion are︱the breve(ˇ)︱and the︱macron(ˋ)。

︱这句话共七个音步,有五个抑扬格。

一些著名英诗体都是抑扬格,如民遥体,十四行诗,双韵体,哀歌等。

例诗:The Eagle : A FragmentHe clasps the crag with crooked hands ;Close to the sun in lonely lands ,Ringed with the azure world , he stands .The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls :He watches from his mountain walls ,And like a thunderbolt he falls .2.扬抑格音步(trochaic foot, trochee ),即重轻格或长短格,由一个重读音节后跟一个轻读音节构成。

五步抑扬格例子 -回复

五步抑扬格例子-回复五步抑扬格是中国古代诗歌中常见的一种韵律格律,在五言绝句等体裁中被广泛使用。

本文以中括号内的内容为主题,将一步一步回答。

[生命的轮回]第一步:起句生命的轮回,如同天空中的星斗,闪烁着璀璨的光芒。

每当迎接新的曙光,我不禁思考着生命的意义与存在的价值。

是什么让我们在这茫茫宇宙中扮演着一场短暂的角色,然后又消失不见呢?我将用文字的力量,探寻这个永恒之谜。

第二步:托物言志岁月如梭,时间的河流从未停歇。

在生与死的交错中,我们见证着生命的轮回。

春天的花朵绽放,夏日的阳光灿烂,秋风吹过的时候,枯叶纷纷飘落,冬日的寒风吹过,大地封印在白雪之下。

生命像沧海一样多变,喜怒哀乐在其中交织。

种子从土地中发芽,长成繁茂的树木,然后最终还给大地。

这是一场如梦一般的旅程,却又不可逆转。

第三步:起承转合生命的轮回,或许没有一个明确的答案。

人们有各种各样的观点和信仰。

有人坚信轮回转世,有人选择相信来世重生,还有人则对生命的结束抱有迷茫和恐惧。

无论是出于对宗教、哲学还是科学的信仰,我们都容易陷入对生命的本质和意义的思考。

我们在这个短暂的时间里,努力寻找着目的和价值。

我们为繁衍生命而努力,为追求幸福而奋斗。

可是在追求的过程中,我们是否迷失了自己?人生是否应该更多地关注内在的成长而不是外在世俗的成就?第四步:承生命的轮回,不仅仅是一个个体的旅程,更是整个宇宙的法则。

在科学的角度来看,生命的存在是一种奇迹。

从最早的宇宙大爆炸开始,无数的星系和行星诞生,有机物质的出现,再到地球上的生命起源。

从最简单的细菌到复杂的人类,生命在演化的过程中变得越来越精巧。

而每个生命体的存在都有其独特的意义。

生命的轮回并非简单的出生与死亡,而是分为不同的阶段和角色。

它鼓励着我们去探索、成长和实现自己的潜能。

第五步:合当我们面对生命的轮回时,我们不应该害怕,而是要勇敢地面对。

生活的意义不仅在于我们的一生,而更在于我们所创造出来的影响和传承。

像星斗一样,在宇宙的长河中发光发热。

五步抑扬格例子

五步抑扬格例子

抑揚格是一种修辞手法,常用于文学作品中,能够增强语句的节奏和美感。

下

面将为您提供五个抑揚格的例子。

1. "花开花落,岁月如梭。

" 这句话的抑揚格体现在“花开花落”和“岁月如梭”这

两对相对呼应的词语上,使整个句子显得韵律流畅。

2. "碧波荡漾,白云飘荡。

" 这个例子中,动词“荡漾”和“飘荡”形成了抑揚格,

表达了美丽而宁静的景象。

3. "日出东方,钟鸣秋色。

" 这句话中的动词“日出”和“钟鸣”形成了抑揚格,描

绘了美丽的日出和秋天的景色。

4. "春风送暖,花开满园。

" 这个例子中的动词“送暖”和“开”形成了抑揚格,表

达了温暖的春天和繁花盛开的景象。

5. "绿树成荫,蓝天白云。

" 这句话的抑揚格体现在“成荫”和“白云”这两对相对

呼应的词语上,形容了郁郁葱葱的树木和晴朗明亮的天空。

通过以上五个抑揚格的例子,我们可以看到它们美化了句子的表达方式,增添

了诗意和节奏感。

这种修辞手法在文学创作中经常被使用,使作品更加生动、抒情。

同时,抑揚格也可以用在日常的表达中,给人带来愉悦的感受。

英文诗歌的节奏划分

英文诗歌的节奏划分

英文诗歌的节奏划分主要依赖于韵律和节拍。

英语诗歌的韵律通常基于音节的重读(重音)和轻读(轻音)的排列。

理解这些基本元素有助于分析和欣赏英文诗歌的节奏:

1.音节:英语中的每个词都由一个或多个音节组成。

音节是诗歌节奏的基础单位。

2.重音和轻音:英语诗歌的节奏感来自于重音音节(强调的、发音更响亮和长的音节)和轻音音节(不强调的、发音更轻和短的音节)的交替。

3.韵脚(Foot):一个韵脚是由一定数量的音节组成的,包含至少一个重音音节。

英语诗歌中常见的韵脚类型包括:

●抑扬格(Iamb):由一个轻音音节后跟一个重音音节

组成(如“de-LIGHT”)。

●扬抑格(Trochee):一个重音音节后跟一个轻音音

节(如“HAP-py”)。

●短促格(Anapest):两个轻音音节后跟一个重音音

节(如“un-der-STAND”)。

长促格(Dactyl):一个重音音节后跟两个轻音音节(如“BEAU-ti-ful”)。

4.诗行长度:诗行的长度通常由韵脚的数量决定。

比如,五个抑扬格组成的诗行称为五步抑扬格,是莎士比亚十四行诗的标准形式。

5.韵律模式:诗歌的节奏也受到整体韵律模式的影响,这可能包括规律的韵脚排列或更自由的形式。

通过了解这些韵律学的基础知识,可以更深入地理解和欣赏英文诗歌的节奏和流动性。

每位诗人可能会根据他们的创作目的和风格选择不同的韵律模式。

四步抑扬格 英语

四步抑扬格英语

四步抑扬格是一种英语诗歌的韵律形式,它由四个音步组成,每个音步由一个重读音节和一个非重读音节组成。

具体来说,四步抑扬格的节奏模式为:轻重轻重,其中第一个重音音节称为扬,第二个非重音音节称为抑。

这种韵律形式在英语诗歌中比较常见,常用于表达情感和营造氛围。

不同的音步类型和不同音步数量的组合可以构成诗行的多种变化形式,如四步抑扬格、五步抑扬格等。

根据押韵在诗行中出现的位置不同,可以包括行尾韵和行内韵等不同类型。

例如:

"Up from the meadow rich with corn

Clear in the cool September morn"

这是一个行尾韵的例子,"corn"和"morn"在诗行的结尾押韵。

"They fondle the fiddle of my heart"

这是一个行内韵的例子,"fiddle"和"heart"在同一诗行中押韵。

五步抑扬格名词解释英文

五步抑扬格名词解释英文

五步抑扬格是中国传统的修辞格之一,其是一种古诗词的韵脚形式,用于表达诗人的情感和思想,使诗歌更加优美动听。

下面通过五步抑扬格名词解释英文的方式,详细解析这一修辞格,以期读者更好地了解其含义和应用。

第一步:五步抑扬格

五步抑扬格的英文释义为“five feet rhythm”,其中,“五步”表示每句诗中含有五个字(或音节);“抑扬”则表示基调进退、升降,形成了一种起伏、抑扬顿挫的节奏感。

第二步:起承转合

五步抑扬格主要应用于诗歌的起承转合部分,即前两句为“起”,第三四句为“承”,最后一句“合”。

第三步:押韵格式

五步抑扬格的押韵格式一般为“aabbccdee”,其中每个字母代表一个韵脚。

例如,李白的《将进酒》中,“人生得意须尽欢,莫使金樽空对月;天生我材必有用,千金散尽还复来;烹羊宰牛且为乐,会须一饮三百杯。

”

第四步:常见应用

五步抑扬格常见于古诗文中,如《将进酒》、《滕王阁序》等,也常用于现代汉语诗歌中。

其应用可以使诗歌更加美妙、优美,也有功能排比、对偶等修辞效果。

第五步:注意事项

在运用五步抑扬格时,需要注意平仄、押韵、意思表达等方面的协调。

抑扬顿挫的表达应该符合上下文的情感色彩,避免形式与内容相悖,造成不良影响。

总之,五步抑扬格是一种古老而鲜活的修辞格,在中国文学史上有着丰富的应用和独特的价值。

通过上述名词解释英文的方式,相信我们都能更好地了解、欣赏和运用这一修辞格。

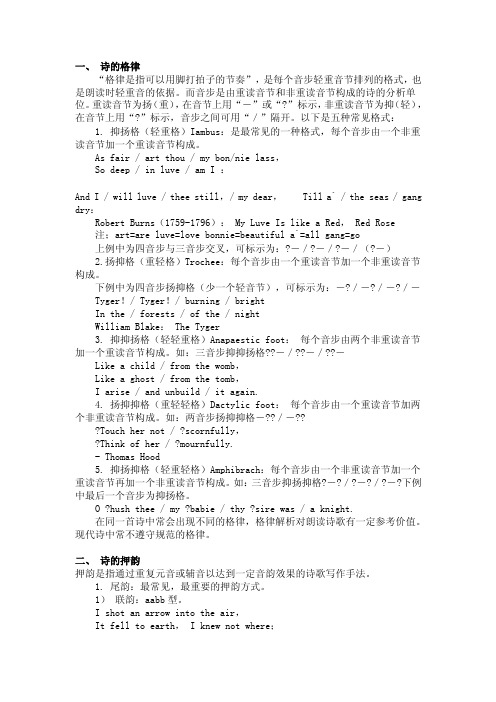

英文诗歌的格律体式

一、诗的格律“格律是指可以用脚打拍子的节奏”,是每个音步轻重音节排列的格式,也是朗读时轻重音的依据。

而音步是由重读音节和非重读音节构成的诗的分析单位。

重读音节为扬(重),在音节上用“-”或“?”标示,非重读音节为抑(轻),在音节上用“?”标示,音步之间可用“/”隔开。

以下是五种常见格式:1. 抑扬格(轻重格)Iambus:是最常见的一种格式,每个音步由一个非重读音节加一个重读音节构成。

As fair / art thou / my bon/nie lass,So deep / in luve / am I :And I / will luve / thee still,/ my dear,Till a` / the seas / gang dry:Robert Burns(1759-1796): My Luve Is like a Red, Red Rose注;art=are luve=love bonnie=beautiful a`=all gang=go上例中为四音步与三音步交叉,可标示为:?-/?-/?-/(?-)2.扬抑格(重轻格)Trochee:每个音步由一个重读音节加一个非重读音节构成。

下例中为四音步扬抑格(少一个轻音节),可标示为:-?/-?/-?/-Tyger!/ Tyger!/ burning / brightIn the / forests / of the / nightWilliam Blake: The Tyger3. 抑抑扬格(轻轻重格)Anapaestic foot:每个音步由两个非重读音节加一个重读音节构成。

如:三音步抑抑扬格??-/??-/??-Like a child / from the womb,Like a ghost / from the tomb,I arise / and unbuild / it again.4. 扬抑抑格(重轻轻格)Dactylic foot:每个音步由一个重读音节加两个非重读音节构成。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

抑扬格五音步目录含义英文诗歌中用得最多的便是抑扬格,百分之九十的英文诗都是用抑扬格写成的。

其中又以抑扬格五音步居多。

要弄清什么是抑扬格五音步(lambic pentameter),要先知道什么音步和抑扬格。

音步我们知道凡是有两个以上音节的英文单词,都有重读音节与轻读音节之分,在一句话中,根据语法、语调、语意的要求,有些词也要重读,有些要轻读。

如he went to town to buy a book.. I’m glad to hear the news. 英文中有重读和轻读之分,重读的音节和轻读的音节,按一定模式配合起来,反复再现,组成诗句,听起来起伏跌宕,抑扬顿挫,就形成了诗歌的节奏。

多音节单词有重音和次重音,次重音根据节奏既可视为重读,也可视为轻读。

读下面这两句诗:Alone │she cuts │and binds│ the grain,And sings │a me│lancho│ly strain.这两行诗的重读与轻读的固定搭配模式是:轻——重。

在每行中再现四次,这样就形成了这两行诗的节奏。

某种固定的轻重搭配叫“音步”(foot),相当与乐谱中的“小节”。

一轻一重,就是这两行诗的音步。

一行诗中轻重搭配出现的次数叫音步数,这两行诗的音步数都是四,所以就称其为四音步诗。

抑扬格如果一个音步中有两个音节,前者为轻,后者为重,则这种音步叫抑扬格音步,其专业术语是(iamb, iambic.)。

轻读是“抑”,重读是“扬”,一轻一重,故称抑扬格。

英语中有大量的单词,其发音都是一轻一重,如adore, excite, above, around, appear, besides, attack, supply, believe, return等,所以用英语写诗,用抑扬格就很便利。

也就是说,抑扬格很符合英语的发音规律。

因此,在英文诗歌中用得最多的便是抑扬格,百分之九十的英文诗都是用抑扬格写成的。

前面的那两句诗就是抑扬格诗。

An EMPTY HOUSEAlexander PopeYou beat│your pate, │and fan│cy wit │will come:Knock as│you please, │there’s no│body│at home.(你拍拍脑袋,以为灵感马上就来。

可任你怎么敲打,也无人把门打开。

pate,脑袋。

fancy,动词:以为,想象。

)此诗的基本音步类型是抑扬格,每行五音步。

因此称此诗的格律是“抑扬格五音步”(iambic pentameter)。

一首诗的音步类型和诗行所含的音步数目构成此诗的格律(meter)。

Iambic pentameterFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaIambic pentameter is a commonly used metrical line in traditional verse and verse drama. The term describes the particular rhythm that the words establish in that line. That rhythm is measured in small groups of syllables; these small groups of syllables are called "feet". The word "iambic" describes the type of foot that is used (in English, an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable). The word "pentameter" indicates that a line has five of these "feet."These terms originally applied to the quantitative meter of classical poetry. They were adopted to describe the equivalent meters in English accentual-syllabic verse. Different languages express rhythm in different ways. In Ancient Greek and Latin, the rhythm is created through the alternation of short and long syllables. In English, the rhythm is created through the use of stress, alternating between unstressed and stressed syllables. An English unstressed syllable is equivalent to a classical short syllable, while an English stressed syllable is equivalent to a classical long syllable. When a pair of syllables is arranged as a short followed by a long, or an unstressed followed by a stressed, pattern, that foot is said to be "iambic". The English word "trapeze" is an example of an iambic pair of syllables, since the word is made up of two syllables ("tra—peze") and is pronounced with the stress on the second syllable ("tra—PEZE", rather than "TRA—peze"). Iambic pentameter is a line made up of five such pairs of short/long, or unstressed/stressed, syllables.Iambic rhythms come relatively naturally in English. Iambic pentameter is the most common meter in English poetry; it is used in many of the major English poetic forms, including blank verse, the heroic couplet, and some of the traditional rhymed stanza forms. William Shakespeare used iambic pentameter in his plays and sonnets.Contents∙1Simple example∙2Rhythmic variation∙3History∙4Reading in drama∙5See also∙6Notes∙7ReferencesSimple exampleAn iambic foot is an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable. The rhythm can be written as:The da-DUM of a human heartbeat is the most common example of this rhythm.A line of iambic pentameter is five iambic feet in a row:The tick-TOCK rhythm of iambic pentameter can be heard in the opening line of Shakespeare's Sonnet 12:When I do count the clock that tells the timeIt is possible to notate this with a '˘' (breve) mark representing an unstressed syllable and a '/'(slash or ictus) mark representing a stressed syllable.[1]In this notation a line of iambic pentameter would look like this:The following line from John Keats' Ode to Autumn is a straightforward example:[2]To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shellsThe scansion of this can be notated as follows:The divisions between feet are marked with a |, and the caesura(a pause) with a double vertical bar ||.˘/˘/˘/˘/˘/To swell|the gourd,||and plump|the ha-|zel shells[edit] Rhythmic variationAlthough strictly speaking, iambic pentameter refers to five iambs in a row (as above), in practice, poets vary their iambic pentameter a great deal, while maintaining the iamb as the most common foot. There are some conventions to these variations, however. Iambic pentameter must always contain only five feet, and the second foot is almost always an iamb. The first foot, on the other hand, is the most likely to change by the use of inversion, which reverses the order of the syllables in the foot. The following line from Shakespeare's Richard III begins with an inversion:Now is|the win-|ter of|our dis-|con-tentAnother common departure from standard iambic pentameter is the addition of a final unstressed syllable, which creates a weak or feminine ending. One of Shakespeare's most famous lines of iambic pentameter has a weak ending:[3]˘/˘/˘//˘˘/˘To be|or not|to be,||that is|the ques-tionThis line also has an inversion of the fourth foot, following the caesura. In general a caesura acts in many ways like a line-end: inversions are common after it, and the extra unstressed syllable of the feminine ending may appear before it. Shakespeare and John Milton(in his work before Paradise Lost) at times employed feminine endings before a caesura.[4]Here is the first quatrain of a sonnet by John Donne, which demonstrates how he uses a number of metrical variations strategically:/˘˘/˘/˘/˘/Bat-ter|my heart|three-per-|soned God,|for you|˘/˘///˘/˘/as yet|but knock,|breathe,shine|and seek|to mend.|˘/˘/˘///˘˘/That I|may rise|and stand|o'er throw|me and bend|˘/˘///˘/˘/Your force|to break,|blow,burn|and make|me new.|Donne uses an inversion (DUM da instead of da DUM) in the first foot of the first line to stress the key verb, "batter", and then sets up a clear iambic pattern with the rest of the line (da DUM da DUM da DUM da DUM). In the second and fourth lines he uses spondees in the third foot to slow down the rhythm as he lists monosyllabic verbs. The parallel rhythm and grammar of these lines highlights the comparison Donne sets up between what God does to him "as yet" ("knock, breathe, shine and seek to mend"), and what he asks God to do ("break, blow, burn and make me new"). Donne also uses enjambment between lines three and four to speed up the flow as he builds to his desire to be made new. To further the speed-up effect of the enjambment, Donne puts an extra syllable in the final foot of the line (this can be read as an anapest (dada DUM) or as an elision).As the examples show, iambic pentameter need not consist entirely of iambs, nor need it have ten syllables. Most poets who have a great facility for iambic pentameter frequently vary the rhythm of their poetry as Donne and Shakespeare do in the examples, both to create a more interesting overall rhythm and to highlight important thematic elements. In fact, the skillful variation of iambic pentameter, rather than the consistent use of it, may well be what distinguishes the rhythmic artistry of Donne, Shakespeare, Milton, and the 20th century sonneteer Edna St. Vincent Millay.Linguists Morris Halle and Samuel Jay Keyser developed a set of rules (English Stress: Its Forms, Its Growth, and Its Role in Verse, Harper and Row, 1971) which correspond with those variations which are permissible in English iambic pentameter. Essentially, the Halle-Keyser rules state that only "stress maximum" syllables are important in determining the meter. A stress maximum syllable is a stressed syllable surrounded on both sides by weak syllables in the same syntactic phrase and in the same verse line. In order to be a permissible line of iambic pentameter, no stress maxima can fall on a syllable that is designated as a weak syllable in the standard, unvaried iambic pentameter pattern. In the Donne line, the word God is not a maximum. That is because it is followed by a pause. Similarly the words you, mend, and bend are not maxima since they are each at the end of a line (as required for the rhyming of mend/bend and you/new.) Rewriting the Donne quatrain showing the stress maxima (denoted with an 'M') results in the following:/˘˘M˘M˘/˘/Bat-ter|my heart|three-per-|soned God,|for you|˘M˘///˘M˘/as yet|but knock,|breathe,shine|and seek|to mend.|˘˘˘M˘///˘˘/That I|may rise|and stand|o'er throw|me and bend|˘M˘///˘M˘/Your force|to break,|blow,burn|and make|me new.|The Halle-Keyser system has been criticized because it can identify passages of prose as iambic pentameter.[5]Other scholars have revised Halle-Keyser, and they, along with Halle and Keyser, are known collectively as “generative metrists.”Later generative metrists pointed out that poets have often treated non-compound words of more than one syllable differently from monosyllables and compounds of monosyllables. Any normally weak syllable may be stressed as a variation if it is a monosyllable, but not if it is part of a polysyllable except at the beginning of a line or a phrase. Thus Shakespeare wrote in The Merchant of Venice, Act I, Scene 2:but wrote no lines of the form of "As gazelles leap a never-resting brook". The stress patterns are the same, and in particular, the normally weak third syllable is stressed in both lines; the difference is that in Shakespeare's line the stressed third syllable is a one-syllable word, "four", whereas in the un-Shakespearean line it is part of a two-syllable word, "gazelles". (The definitions and exceptions are more technical than stated here.) Pope followed such a rule strictly, Shakespeare fairly strictly, Milton much less, and Donne not at all—which may be why Ben Jonson said Donne deserved hanging for "not keeping of accent".[6]Derek Attridge has pointed out the limits of the generative approach; it has “not brought us any closer to understanding why particular metrical forms are common in English, why certainvariations interrupt the metre and others do not, or why metre functions so powerfully as a literary device.”[7]Generative metrists also fail to recognize that a normally weak syllable in a strong position will be pronounced differently, i.e. “promoted” and so no longer "weak."Several scholars have argued that iambic pentameter has been so important in the history of English poetry by contrasting it with the one other important meter (Tetrameter), variously called “four-beat,” “strong-stress,” “native meter,” or “four-by-four meter.”[8]Four-beat, with four beats to a line, is the meter of nursery rhymes, children’s jump-rope and counting-out rhymes, folk songs and ballads, marching cadence calls, and a good deal of art poetry. It has been described by Attridge as based on doubling: two beats to each half line, two half lines to a line, two pairs of lines to a stanza. The metrical stresses alternate between light and heavy.[9]It is a heavily regular beat that produces something like a repeated tune in the performing voice, and is, indeed, close to song. In fact, a great many songs and almost all jazz music are four-beat. Because of its odd number of metrical beats, iambic pentameter, as Attridge says, does not impose itself on the natural rhythm of spoken language.[10] Thus iambic pentameter frees intonation from the repetitiveness of four-beat and allows instead the varied intonations of significant speech to be heard. Pace can be varied in iambic pentameter, as it cannot in four-beat, as Alexander Pope demonstrated in his “An Essay on Criticism”:When Ajax strives some rock’s vast weight to throw,The line, too, labours and the words move slow.Not so when swift Camilla scours the plain,Flies o’er th’unbending corn, and skims along the main.Moreover, iambic pentameter, instead of the steady alternation of lighter and heavier beats of four-beat, permits principal accents, that is accents on the most significant words, to occur at various points in a line as long as they are on the even–numbered syllables, or on the first syllable, in the case of an initial trochaic inversion. It is not the case, as is often alleged, that iambic pentameter is “natural” to English; rather it is that iambic pentameter allows the varied intonations and pace natural to significant speech to be heard along with the regular meter.[11]。