启航曹其军写作讲义正文

一前言

一、概述一.前言高等学校体育是高等学校教育的重要组成部分,体育课程教学是高等学校体育工作的中心环节,是达到学校体育目的,完成学校体育任务的主要途径。

健康体魄是青年为祖国和人民服务的基本前提,是中华民族旺盛生命力的体现。

学校教育要树立健康第一的指导思想,切实加强体育工作,使学生掌握基本的运动技能,养成坚持锻炼身体的良好习惯。

为了贯彻党的教育方针,促进学生的健康发展,使当代大学生成为社会主义事业的建设者和接班人,根据《中共中央国务院关于深化教育改革全面推进素质教育的决定》和国务院批准发布实行的《学校体育工作条例》及国家教育部颁发的《全国普通高等学校体育课程教学指导纲要的通知》精神,在总结我校体育课程建设和教学改革经验及兄弟院校经验的基础上,结合当前我校体育教学的实际情况,对我校原教学大纲进行了重新修订。

二.体育课程性质1.体育课程是大学生以身体练习为主要手段,通过合理的体育教育和科学的体育锻炼过程,达到增强体质、增进健康和提高体育素养为主要目标的公共必修课程;是学校课程体系的重要组成部分;是高等学校体育工作的中心环节。

2. 体育课程是寓促进身心和谐发展、思想品德教育、文化科学教育、生活与体育技能教育于身体活动并有机结合的教育过程;是实施素质教育和培养全面发展的人才的重要途径。

三.体育课程目标1. 基本目标(1)运动参与目标:积极参与各种体育活动并基本形成自觉的锻炼习惯,基本形成终身体育意识,能够编制可行的个人锻炼计划,有一定的体育文化欣赏能力。

(2)运动技能目标:熟练掌握两项以上健身运动的基本方法和技能;能科学地进行体育锻炼,提高自己的运动能力;掌握常见运动创伤的处置方法。

(3)身体健康目标:能测试和评价自身体质健康状况,掌握提高身体素质、全面发展体能的知识与方法;能合理选择人体需要的健康营养食品;形成健康的生活方式;具有健康的体魄。

(4)心理健康目标:根据自己的能力设置体育学习目标;自觉通过体育活动改善心理状态、克服心理障碍,养成积极乐观的生活态度;运用适宜的方法调节自己的情绪;在运动中体验运动的乐趣和成功的感觉。

启航2014考研暑期强化班专业课下载链接汇总8.3

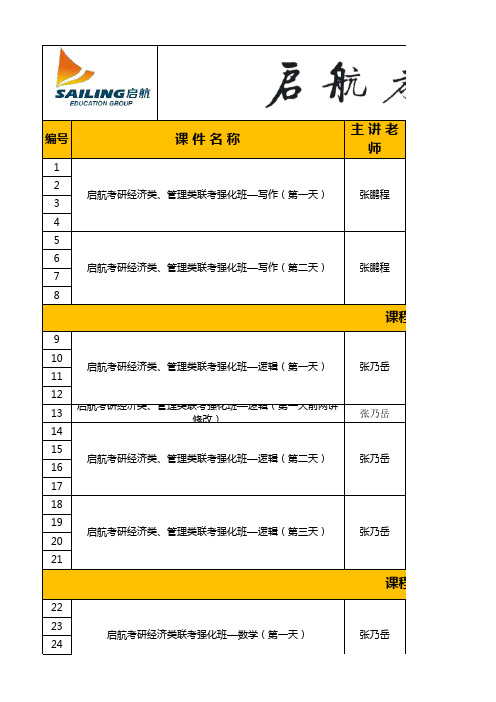

编号主 讲 老 师12345678910111213张乃岳141516171819202122232425启航考研经济类联考强化班—数学(第一天)张乃岳张乃岳启航考研经济类、管理类联考强化班—逻辑(第一天前两讲修改)启航考研经济类、管理类联考强化班—逻辑(第二天)张乃岳启航考研经济类、管理类联考强化班—逻辑(第三天)课 件 名 称启航考研经济类、管理类联考强化班—写作(第一天)张鹏程启航考研经济类、管理类联考强化班—逻辑(第一天)张乃岳张鹏程启航考研经济类、管理类联考强化班—写作(第二天)课程说课程说课李俊红上 传 时 间下 载 链 接第一讲:/c02ztnyb65第二讲:/c0a2a4kl5u 第三讲:/c0j683mwxn 第四讲:/c04fjbqbxt 第一讲:/c0kku6kc5s 第二讲:/c0yakq3k0g 第三讲:/c0ql2tgmsj 第四讲:/c03m8xjaz5第一讲:/c0qtofrjhh第二讲:/c0mzai6mqb 第三讲:/c053q6yhca 第四讲:/c0tahlsnlb2013.7.23/share/link?shareid=923167142&uk=1395717154第一讲:/c09ghadsrx第二讲:/c0px6aaj30第三讲:/c0p0fnb8rs 第四讲:/c0tu6kthia 第一讲:/c0u3txbmcu第二讲:/c0bkmaawb4第三讲:/c0xraw61a1第四讲:/c0bbspivmt第一讲:/c02wm7j5pj第二讲:/c00gnkp7p9第三讲:/c04v7dhcov 第四讲:/c0vha89rh32013.7.222013.7.242013.7.232013.7.222013.7.222013.7.22课程说明:经济类联考和管理类联考写作是用一样的课件。

课程说明:经济类联考和管理类联考逻辑是用一样的课件。

2013.7.25/share/link?shareid=2855457530&uk=1395717154gmdf启航2014考研计算机内部绝密讲义。

2008年曹其军考研英语阅读理解StepbyStep(2)

Text 1 The recent, apparently successful, prediction by mathematical models of an appearance of El Nino—the warm ocean current that periodically develops along the Pacific coast of South America—has excited researchers. Jacob Berknes pointed out over 20 years ago how winds might create either abnormally warm or abnormally cold water in the eastern equatorial Pacific. 1) Nevertheless, until the development of the models no one could explain why conditions should regularly shift from one to the other, as happens in the periodic changes between appearances of the warm El Nino and the cold socalled antiEl Nino. The answer, at least if the current model that links the behavior of the ocean to that of the atmosphere is correct, is to be found in the ocean. 2) It has long been known that during an El Nino, two conditions exist: A) unusually warm water extends along the eastern Pacific, principally along the coasts of Ecuador and Peru, and B) winds blow from the west into the warmer air rising over the warm water in the east. These winds tend to create a feedback mechanism by driving the warmer surface water into “piles” that block the normal rising of deeper, cold water in the east and further warm the eastern water, thus strengthening the wind. The contribution of the model is to show that the winds of an El Nino, which raise sea level in the east, simultaneously send a signal to the west lowering sea level. According to the model, that signal is generated as a negative Rossby wave, a wave of depressed sea level, that moves westward parallel to the equator at 25 to 85 kilometers per day. 3) Taking months to travel across the Pacific, Rossby waves march to the western boundary of the Pacific basin, which is modeled as a smooth wall but in reality consists of quite irregular island chains, such as the Philippines and Indonesia. When the waves meet the western boundary, they are reflected, and the model predicts that Rossby waves will be broken into numerous coastal Kelvin waves carrying the same negative sealevel signal. These eventually shoot toward the equator, and then head eastward along the equator propelled by the rotation of the Earth at a speed of about 250 kilometers per day. When Kelvin waves of sufficient amplitude arrive from the western Pacific, their negative sealevel signal overcomes the feedback mechanism tending to raise the sea level, and they begin to drive the system into the opposite cold mode. This produces a gradual shift in winds, one that will eventually send Rossby waves westward, waves that will eventually return as cold cycleending Kelvin waves, beginning another warming cycle. 1 It was not until the appearance of mathematical models that [A] El Nino was defined as unusually warm or cold ocean currents. [B] the occurrences of E1 Nino were inaccurately predicted. [C] the cause of regular El Nino was correctly interpreted. [D] the shifts in ocean currents were linked to atmospheric conditions. 2 Which of the following best describes the organization of the first paragraph? [A] A model is described and its value assessed. [B] A result is reported and its importance explained. [C] A phenomenon is noted and its significance debated. [D] A hypothesis is introduced and contrary evidence presented. 3 According to the model, which of the following signals the disappearance of an E1 Nino? [A] The arrival in the eastern Pacific of negative Kelvin waves. [B] A shift in the direction of the winds produced by an antiEl Nino. [C] The reflection of Kelvin waves reaching the eastern border of the Pacific. [D] An increase in the speed at which negative Rossby waves cross the Pacific. 4 Which of the following would most seriously undermine the validity of the model? [A] El Nino extends much farther along the coasts of Ecuador and Peru during some years. [B] The rising of cold water in the eastern Pacific depends on the local characters. [C] The variations in the time for Rossby waves to cross the Pacific rely on the wind power. [D] The Pacific irregular western coast hinders most Kelvin waves from heading eastward. 5 The primary purpose of the text as a whole is to [A] introduce a new explanation of physical phenomenon. [B] explain the difference between two natural phenomena. [C] illustrate the limits of applying mathematics to complex problems. [D] clarify the distinction between an old explanation and a new model. 难句突破 1 Nevertheless, until the development of the models no one could explain why conditions should regularly shift from one to the other, as happens in the periodic changes between appearances of the warm El Nino and the cold socalled antiEl Nino. 【解析】本句话的主⼲是“no one could explain why...”。

MENEXENUS

MENEXENUSby Plato Translated by Benjamin JowettAPPENDIX I.It seems impossible to separate by any exact line the genuine writings of Plato from the spurious. The only external evidence to them which is of much value is that of Aristotle; for the Alexandrian catalogues of a century later include manifest forgeries. Even the value of the Aristotelian authority is a good deal impaired by the uncertainty concerning the date and authorship of the writings which are ascribed to him. And several of the citations of Aristotle omit the name of Plato, and some of them omit the name of the dialogue from which they are taken. Prior, however, to the enquiry about the writings of a particular author, general considerations which equally affect all evidence to the genuineness of ancient writings are the following: Shorter works are more likely to have been forged, or to have received an erroneous designation, than longer ones; and some kinds of composition, such as epistles or panegyrical orations, are more liable to suspicion than others; those, again, which have a taste of sophistry in them, or the ring of a later age, or the slighter character of a rhetorical exercise, or in which a motive or some affinity to spurious writings can be detected, or which seem to have originated in a name or statement really occurring in some classical author, are also of doubtful credit; while there is no instance of any ancient writing proved to be a forgery, which combines excellence with length.A really great and original writer would have no object in fathering his works on Plato; and to the forger or imitator, the 'literary hack' of Alexandria and Athens, the Gods did not grant originality or genius. Further, in attempting to balance the evidence for and against a Platonic dialogue, we must not forget that the form of the Platonic writing was common to several of his contemporaries. Aeschines, Euclid, Phaedo, Antisthenes, and in the next generation Aristotle, are all said to have composed dialogues; and mistakes of names are very likely to have occurred. Greek literature in the third century before Christ was almostas voluminous as our own, and without the safeguards of regular publication, or printing, or binding, or even of distinct titles. An unknown writing was naturally attributed to a known writer whose works bore the same character; and the name once appended easily obtained authority. A tendency may also be observed to blend the works and opinions of the master with those of his scholars. To a later Platonist, the difference between Plato and his imitators was not so perceptible as to ourselves. The Memorabilia of Xenophon and the Dialogues of Plato are but a part of a considerable Socratic literature which has passed away. And we must consider how we should regard the question of the genuineness of a particular writing, if this lost literature had been preserved to us.These considerations lead us to adopt the following criteria of genuineness: (1) That is most certainly Plato's which Aristotle attributes to him by name, which (2) is of considerable length, of (3) great excellence, and also (4) in harmony with the general spirit of the Platonic writings. But the testimony of Aristotle cannot always be distinguished from that of a later age (see above); and has various degrees of importance. Those writings which he cites without mentioning Plato, under their own names, e.g. the Hippias, the Funeral Oration, the Phaedo, etc., have an inferior degree of evidence in their favour. They may have been supposed by him to be the writings of another, although in the case of really great works, e.g. the Phaedo, this is not credible; those again which are quoted but not named, are still more defective in their external credentials. There may be also a possibility that Aristotle was mistaken, or may have confused the master and his scholars in the case of a short writing; but this is inconceivable about a more important work, e.g. the Laws, especially when we remember that he was living at Athens, and a frequenter of the groves of the Academy, during the last twenty years of Plato's life. Nor must we forget that in all his numerous citations from the Platonic writings he never attributes any passage found in the extant dialogues to any one but Plato. And lastly, we may remark that one or two great writings, such as the Parmenides and the Politicus, which arewholly devoid of Aristotelian (1) credentials may be fairly attributed to Plato, on the ground of (2) length, (3) excellence, and (4) accordance with the general spirit of his writings. Indeed the greater part of the evidence for the genuineness of ancient Greek authors may be summed up under two heads only: (1) excellence; and (2) uniformity of tradition--a kind of evidence, which though in many cases sufficient, is of inferior value.Proceeding upon these principles we appear to arrive at the conclusion that nineteen-twentieths of all the writings which have ever been ascribed to Plato, are undoubtedly genuine. There is another portion of them, including the Epistles, the Epinomis, the dialogues rejected by the ancients themselves, namely, the Axiochus, De justo, De virtute, Demodocus, Sisyphus, Eryxias, which on grounds, both of internal and external evidence, we are able with equal certainty to reject. But there still remains a small portion of which we are unable to affirm either that they are genuine or spurious. They may have been written in youth, or possibly like the works of some painters, may be partly or wholly the compositions of pupils; or they may have been the writings of some contemporary transferred by accident to the more celebrated name of Plato, or of some Platonist in the next generation who aspired to imitate his master. Not that on grounds either of language or philosophy we should lightly reject them. Some difference of style, or inferiority of execution, or inconsistency of thought, can hardly be considered decisive of their spurious character. For who always does justice to himself, or who writes with equal care at all times? Certainly not Plato, who exhibits the greatest differences in dramatic power, in the formation of sentences, and in the use of words, if his earlier writings are compared with his later ones, say the Protagoras or Phaedrus with the Laws. Or who can be expected to think in the same manner during a period of authorship extending over above fifty years, in an age of great intellectual activity, as well as of political and literary transition? Certainly not Plato, whose earlier writings are separated from his later ones by as wide an interval of philosophical speculation as that which separates his later writings from Aristotle.The dialogues which have been translated in the first Appendix, and which appear to have the next claim to genuineness among the Platonic writings, are the Lesser Hippias, the Menexenus or Funeral Oration, the First Alcibiades. Of these, the Lesser Hippias and the Funeral Oration are cited by Aristotle; the first in the Metaphysics, the latter in the Rhetoric. Neither of them are expressly attributed to Plato, but in his citation of both of them he seems to be referring to passages in the extant dialogues. From the mention of 'Hippias' in the singular by Aristotle, we may perhaps infer that he was unacquainted with a second dialogue bearing the same name. Moreover, the mere existence of a Greater and Lesser Hippias, and of a First and Second Alcibiades, does to a certain extent throw a doubt upon both of them. Though a very clever and ingenious work, the Lesser Hippias does not appear to contain anything beyond the power of an imitator, who was also a careful student of the earlier Platonic writings, to invent. The motive or leading thought of the dialogue may be detected in Xen. Mem., and there is no similar instance of a 'motive' which is taken from Xenophon in an undoubted dialogue of Plato. On the other hand, the upholders of the genuineness of the dialogue will find in the Hippias a true Socratic spirit; they will compare the Ion as being akin both in subject and treatment; they will urge the authority of Aristotle; and they will detect in the treatment of the Sophist, in the satirical reasoning upon Homer, in the reductio ad absurdum of the doctrine that vice is ignorance, traces of a Platonic authorship. In reference to the last point we are doubtful, as in some of the other dialogues, whether the author is asserting or overthrowing the paradox of Socrates, or merely following the argument 'whither the wind blows.' That no conclusion is arrived at is also in accordance with the character of the earlier dialogues. The resemblances or imitations of the Gorgias, Protagoras, and Euthydemus, which have been observed in the Hippias, cannot with certainty be adduced on either side of the argument. On the whole, more may be said in favour of the genuineness of the Hippias than against it.The Menexenus or Funeral Oration is cited by Aristotle, and is interesting as supplying an example of the manner in which the oratorspraised 'the Athenians among the Athenians,' falsifying persons and dates, and casting a veil over the gloomier events of Athenian history. It exhibits an acquaintance with the funeral oration of Thucydides, and was, perhaps, intended to rival that great work. If genuine, the proper place of the Menexenus would be at the end of the Phaedrus. The satirical opening and the concluding words bear a great resemblance to the earlier dialogues; the oration itself is professedly a mimetic work, like the speeches in the Phaedrus, and cannot therefore be tested by a comparison of the other writings of Plato. The funeral oration of Pericles is expressly mentioned in the Phaedrus, and this may have suggested the subject, in the same manner that the Cleitophon appears to be suggested by the slight mention of Cleitophon and his attachment to Thrasymachus in the Republic; and the Theages by the mention of Theages in the Apology and Republic; or as the Second Alcibiades seems to be founded upon the text of Xenophon, Mem. A similar taste for parody appears not only in the Phaedrus, but in the Protagoras, in the Symposium, and to a certain extent in the Parmenides.To these two doubtful writings of Plato I have added the First Alcibiades, which, of all the disputed dialogues of Plato, has the greatest merit, and is somewhat longer than any of them, though not verified by the testimony of Aristotle, and in many respects at variance with the Symposium in the description of the relations of Socrates and Alcibiades. Like the Lesser Hippias and the Menexenus, it is to be compared to the earlier writings of Plato. The motive of the piece may, perhaps, be found in that passage of the Symposium in which Alcibiades describes himself as self-convicted by the words of Socrates. For the disparaging manner in which Schleiermacher has spoken of this dialogue there seems to be no sufficient foundation. At the same time, the lesson imparted is simple, and the irony more transparent than in the undoubted dialogues of Plato. We know, too, that Alcibiades was a favourite thesis, and that at least five or six dialogues bearing this name passed current in antiquity, and are attributed to contemporaries of Socrates and Plato. (1) In the entire absence of real external evidence (for the catalogues of the Alexandrianlibrarians cannot be regarded as trustworthy); and (2) in the absence of the highest marks either of poetical or philosophical excellence; and (3) considering that we have express testimony to the existence of contemporary writings bearing the name of Alcibiades, we are compelled to suspend our judgment on the genuineness of the extant dialogue.Neither at this point, nor at any other, do we propose to draw an absolute line of demarcation between genuine and spurious writings of Plato. They fade off imperceptibly from one class to another. There may have been degrees of genuineness in the dialogues themselves, as there are certainly degrees of evidence by which they are supported. The traditions of the oral discourses both of Socrates and Plato may have formed the basis of semi-Platonic writings; some of them may be of the same mixed character which is apparent in Aristotle and Hippocrates, although the form of them is different. But the writings of Plato, unlike the writings of Aristotle, seem never to have been confused with the writings of his disciples: this was probably due to their definite form, and to their inimitable excellence. The three dialogues which we have offered in the Appendix to the criticism of the reader may be partly spurious and partly genuine; they may be altogether spurious;--that is an alternative which must be frankly admitted. Nor can we maintain of some other dialogues, such as the Parmenides, and the Sophist, and Politicus, that no considerable objection can be urged against them, though greatly overbalanced by the weight (chiefly) of internal evidence in their favour. Nor, on the other hand, can we exclude a bare possibility that some dialogues which are usually rejected, such as the Greater Hippias and the Cleitophon, may be genuine. The nature and object of these semi-Platonic writings require more careful study and more comparison of them with one another, and with forged writings in general, than they have yet received, before we can finally decide on their character. We do not consider them all as genuine until they can be proved to be spurious, as is often maintained and still more often implied in this and similar discussions; but should say of some of them, that their genuineness is neither proven nor disproven until further evidence about them can beadduced. And we are as confident that the Epistles are spurious, as that the Republic, the Timaeus, and the Laws are genuine.On the whole, not a twentieth part of the writings which pass under the name of Plato, if we exclude the works rejected by the ancients themselves and two or three other plausible inventions, can be fairly doubted by those who are willing to allow that a considerable change and growth may have taken place in his philosophy (see above). That twentieth debatable portion scarcely in any degree affects our judgment of Plato, either as a thinker or a writer, and though suggesting some interesting questions to the scholar and critic, is of little importance to the general reader.INTRODUCTION.The Menexenus has more the character of a rhetorical exercise than any other of the Platonic works. The writer seems to have wished to emulate Thucydides, and the far slighter work of Lysias. In his rivalry with the latter, to whom in the Phaedrus Plato shows a strong antipathy, he is entirely successful, but he is not equal to Thucydides. The Menexenus, though not without real Hellenic interest, falls very far short of the rugged grandeur and political insight of the great historian. The fiction of the speech having been invented by Aspasia is well sustained, and is in the manner of Plato, notwithstanding the anachronism which puts into her mouth an allusion to the peace of Antalcidas, an event occurring forty years after the date of the supposed oration. But Plato, like Shakespeare, is careless of such anachronisms, which are not supposed to strike the mind of the reader. The effect produced by these grandiloquent orations on Socrates, who does not recover after having heard one of them for three days and more, is truly Platonic.Such discourses, if we may form a judgment from the three which are extant (for the so-called Funeral Oration of Demosthenes is a bad and spurious imitation of Thucydides and Lysias), conformed to a regular type. They began with Gods and ancestors, and the legendary history of Athens, to which succeeded an almost equally fictitious account of later times. The Persian war usually formed the centre of the narrative; in the age of Isocrates and Demosthenes the Athenians were still living on the glories of Marathon and Salamis. The Menexenus veils in panegyric the weak places of Athenian history. The war of Athens and Boeotia is a war of liberation; the Athenians gave back the Spartans taken at Sphacteria out of kindness-- indeed, the only fault of the city was too great kindness to their enemies, who were more honoured than the friends of others (compare Thucyd., which seems to contain the germ of the idea); we democrats are the aristocracy of virtue, and the like. These are the platitudes andfalsehoods in which history is disguised. The taking of Athens is hardly mentioned.The author of the Menexenus, whether Plato or not, is evidently intending to ridicule the practice, and at the same time to show that he can beat the rhetoricians in their own line, as in the Phaedrus he may be supposed to offer an example of what Lysias might have said, and of how much better he might have written in his own style. The orators had recourse to their favourite loci communes, one of which, as we find in Lysias, was the shortness of the time allowed them for preparation. But Socrates points out that they had them always ready for delivery, and that there was no difficulty in improvising any number of such orations. To praise the Athenians among the Athenians was easy,--to praise them among the Lacedaemonians would have been a much more difficult task. Socrates himself has turned rhetorician, having learned of a woman, Aspasia, the mistress of Pericles; and any one whose teachers had been far inferior to his own--say, one who had learned from Antiphon the Rhamnusian--would be quite equal to the task of praising men to themselves. When we remember that Antiphon is described by Thucydides as the best pleader of his day, the satire on him and on the whole tribe of rhetoricians is transparent.The ironical assumption of Socrates, that he must be a good orator because he had learnt of Aspasia, is not coarse, as Schleiermacher supposes, but is rather to be regarded as fanciful. Nor can we say that the offer of Socrates to dance naked out of love for Menexenus, is any more un-Platonic than the threat of physical force which Phaedrus uses towards Socrates. Nor is there any real vulgarity in the fear which Socrates expresses that he will get a beating from his mistress, Aspasia: this is the natural exaggeration of what might be expected from an imperious woman. Socrates is not to be taken seriously in all that he says, and Plato, both in the Symposium and elsewhere, is not slow to admit a sort of Aristophanic humour. How a great original genius like Plato might or might not have written, what was his conception of humour, or what limits he would have prescribed to himself, if any, in drawing the picture of the Silenus Socrates,are problems which no critical instinct can determine.On the other hand, the dialogue has several Platonic traits, whether original or imitated may be uncertain. Socrates, when he departs from his character of a 'know nothing' and delivers a speech, generally pretends that what he is speaking is not his own composition. Thus in the Cratylus he is run away with; in the Phaedrus he has heard somebody say something-- is inspired by the genius loci; in the Symposium he derives his wisdom from Diotima of Mantinea, and the like. But he does not impose on Menexenus by his dissimulation. Without violating the character of Socrates, Plato, who knows so well how to give a hint, or some one writing in his name, intimates clearly enough that the speech in the Menexenus like that in the Phaedrus is to be attributed to Socrates. The address of the dead to the living at the end of the oration may also be compared to the numerous addresses of the same kind which occur in Plato, in whom the dramatic element is always tending to prevail over the rhetorical. The remark has been often made, that in the Funeral Oration of Thucydides there is no allusion to the existence of the dead. But in the Menexenus a future state is clearly, although not strongly, asserted.Whether the Menexenus is a genuine writing of Plato, or an imitation only, remains uncertain. In either case, the thoughts are partly borrowed from the Funeral Oration of Thucydides; and the fact that they are so, is not in favour of the genuineness of the work. Internal evidence seems to leave the question of authorship in doubt. There are merits and there are defects which might lead to either conclusion. The form of the greater part of the work makes the enquiry difficult; the introduction and the finale certainly wear the look either of Plato or of an extremely skilful imitator. The excellence of the forgery may be fairly adduced as an argument that it is not a forgery at all. In this uncertainty the express testimony of Aristotle, who quotes, in the Rhetoric, the well-known words, 'It is easy to praise the Athenians among the Athenians,' from the Funeral Oration, may perhaps turn the balance in its favour. It must be remembered also that the work was famous in antiquity, and is included in the Alexandrian catalogues of Platonic writings.MENEXENUSPERSONS OF THE DIALOGUE: Socrates and Menexenus.SOCRATES: Whence come you, Menexenus? Are you from the Agora?MENEXENUS: Yes, Socrates; I have been at the Council.SOCRATES: And what might you be doing at the Council? And yet I need hardly ask, for I see that you, believing yourself to have arrived at the end of education and of philosophy, and to have had enough of them, are mounting upwards to things higher still, and, though rather young for the post, are intending to govern us elder men, like the rest of your family, which has always provided some one who kindly took care of us.MENEXENUS: Yes, Socrates, I shall be ready to hold office, if you allow and advise that I should, but not if you think otherwise. I went to the council chamber because I heard that the Council was about to choose some one who was to speak over the dead. For you know that there is to be a public funeral?SOCRATES: Yes, I know. And whom did they choose?MENEXENUS: No one; they delayed the election until tomorrow, but I believe that either Archinus or Dion will be chosen.SOCRATES: O Menexenus! Death in battle is certainly in many respects a noble thing. The dead man gets a fine and costly funeral, although he may have been poor, and an elaborate speech is made over him by a wise man who has long ago prepared what he has to say, although he who is praised may not have been good for much. The speakers praise him for what he has done and for what he has not done--that is the beauty of them--and they steal away our souls with their embellished words; in every conceivable form they praise the city; and they praise those who died in war, and all our ancestors who went before us; and they praise ourselves also who are still alive, until I feel quite elevated by their laudations, and I stand listening to their words,Menexenus, and become enchanted by them, and all in a moment I imagine myself to have become a greater and nobler and finer man than I was before. And if, as often happens, there are any foreigners who accompany me to the speech, I become suddenly conscious of having a sort of triumph over them, and they seem to experience a corresponding feeling of admiration at me, and at the greatness of the city, which appears to them, when they are under the influence of the speaker, more wonderful than ever. This consciousness of dignity lasts me more than three days, and not until the fourth or fifth day do I come to my senses and know where I am; in the meantime I have been living in the Islands of the Blest. Such is the art of our rhetoricians, and in such manner does the sound of their words keep ringing in my ears.MENEXENUS: You are always making fun of the rhetoricians, Socrates; this time, however, I am inclined to think that the speaker who is chosen will not have much to say, for he has been called upon to speak at a moment's notice, and he will be compelled almost to improvise.SOCRATES: But why, my friend, should he not have plenty to say? Every rhetorician has speeches ready made; nor is there any difficulty in improvising that sort of stuff. Had the orator to praise Athenians among Peloponnesians, or Peloponnesians among Athenians, he must be a good rhetorician who could succeed and gain credit. But there is no difficulty in a man's winning applause when he is contending for fame among the persons whom he is praising.MENEXENUS: Do you think not, Socrates?SOCRATES: Certainly 'not.'MENEXENUS: Do you think that you could speak yourself if there should be a necessity, and if the Council were to choose you?SOCRATES: That I should be able to speak is no great wonder, Menexenus, considering that I have an excellent mistress in the art of rhetoric,--she who has made so many good speakers, and one who was the best among all the Hellenes--Pericles, the son of Xanthippus.MENEXENUS: And who is she? I suppose that you mean Aspasia.SOCRATES: Yes, I do; and besides her I had Connus, the son ofMetrobius, as a master, and he was my master in music, as she was in rhetoric. No wonder that a man who has received such an education should be a finished speaker; even the pupil of very inferior masters, say, for example, one who had learned music of Lamprus, and rhetoric of Antiphon the Rhamnusian, might make a figure if he were to praise the Athenians among the Athenians.MENEXENUS: And what would you be able to say if you had to speak?SOCRATES: Of my own wit, most likely nothing; but yesterday I heard Aspasia composing a funeral oration about these very dead. For she had been told, as you were saying, that the Athenians were going to choose a speaker, and she repeated to me the sort of speech which he should deliver, partly improvising and partly from previous thought, putting together fragments of the funeral oration which Pericles spoke, but which, as I believe, she composed.MENEXENUS: And can you remember what Aspasia said?SOCRATES: I ought to be able, for she taught me, and she was ready to strike me because I was always forgetting.MENEXENUS: Then why will you not rehearse what she said?SOCRATES: Because I am afraid that my mistress may be angry with me if I publish her speech.MENEXENUS: Nay, Socrates, let us have the speech, whether Aspasia's or any one else's, no matter. I hope that you will oblige me.SOCRATES: But I am afraid that you will laugh at me if I continue the games of youth in old age.MENEXENUS: Far otherwise, Socrates; let us by all means have the speech.SOCRATES: Truly I have such a disposition to oblige you, that if you bid me dance naked I should not like to refuse, since we are alone. Listen then: If I remember rightly, she began as follows, with the mention of the dead:-- (Thucyd.)There is a tribute of deeds and of words. The departed have already had the first, when going forth on their destined journey they wereattended on their way by the state and by their friends; the tribute of words remains to be given to them, as is meet and by law ordained. For noble words are a memorial and a crown of noble actions, which are given to the doers of them by the hearers. A word is needed which will duly praise the dead and gently admonish the living, exhorting the brethren and descendants of the departed to imitate their virtue, and consoling their fathers and mothers and the survivors, if any, who may chance to be alive of the previous generation. What sort of a word will this be, and how shall we rightly begin the praises of these brave men? In their life they rejoiced their own friends with their valour, and their death they gave in exchange for the salvation of the living. And I think that we should praise them in the order in which nature made them good, for they were good because they were sprung from good fathers. Wherefore let us first of all praise the goodness of their birth; secondly, their nurture and education; and then let us set forth how noble their actions were, and how worthy of the education which they had received.And first as to their birth. Their ancestors were not strangers, nor are these their descendants sojourners only, whose fathers have come from another country; but they are the children of the soil, dwelling and living in their own land. And the country which brought them up is not like other countries, a stepmother to her children, but their own true mother; she bore them and nourished them and received them, and in her bosom they now repose. It is meet and right, therefore, that we should begin by praising the land which is their mother, and that will be a way of praising their noble birth.The country is worthy to be praised, not only by us, but by all mankind; first, and above all, as being dear to the Gods. This is proved by the strife and contention of the Gods respecting her. And ought not the country which the Gods praise to be praised by all mankind? The second praise which may be fairly claimed by her, is that at the time when the whole earth was sending forth and creating diverse animals, tame and wild, she our mother was free and pure from savage monsters, and out of all animals selected and brought forth man, who is superior to the rest in。

第一部分:作文起航 讲义—2023年小升初语文写作技巧部编版

第一部分作文起航本章要点写好一句话写好基本句一、用句子的主要成分写好一句话句子的主要成分是主语、谓语、宾语,次要成分是定语、状语、补语。

把三个主要部分写好就是一句完整的句子。

例如妈妈是名老师。

这是一个简单而完整的句子,要想锻炼写作基本功,就得写生动的句子,生动的句子怎么写就要补充完句子的次要成分定语、状语、补语,也就是扩写成一个更完整的句子。

如漂亮的妈妈是一名受人尊重的老师。

(用“漂亮”来形容妈妈用“受人尊重”来修饰老师)二、抓住时间、地点、人物、事件写好一句话时间、地点、人物、事件(事件的起因、经过、结果)这四点是记叙文的四要素,也可以说是记叙文的六要素。

抓住这几点写好一句话是写好记叙文的基础。

例如九月十日那天,漂亮的妈妈上学校的主席台领取了优秀教师的荣誉证书。

(时间:九月十日地点:学校主席台人物:妈妈事件:领取优秀教师的荣誉证书)写好一段话一、用好词名句写好一段话(一)、用连续性词语写好一段话1.用动作的连续性例如即他弯着腰,篮球在他的手下前后左右不停地拍着,两眼溜溜地转动,寻找“突围”的机会。

突然他加快了步伐,一会儿左拐,一会儿右拐,冲过了两层防线,来到篮下,一个虎跳,转身投篮,篮球在空中划了一条漂亮的弧线后,不偏不倚地落在筐内。

2.用时间的连续性例如我们班和三班的篮球比赛太激烈了,比分交替领先。

开场5分钟,我们班6∶4领先开场10分钟,三班12∶11反超比赛结束时,我们班最终以30∶28险胜三班。

3.用空间方位的连续性例如我们的教室宽敞又明亮,教室前方有一块黑板,是老师写板书的地方。

黑板的前面有一个讲台,讲台上放着一台智能化的电脑,只要打开电脑,敲下键盘,我们就可以足不出户浏览天下。

讲台的正前方整整齐齐地排列着5排课桌椅,我们就在这里上课。

教室后面是板报墙,展示着同学们亲自制作的手抄报。

(二)用动词的近义词写好一段话例如我登上峨眉山顶,视野十分开阔。

我仰望天空,朵朵像棉花般的白云缓缓地从头顶飘过我眺望远方,皑皑白雪在阳光照耀下若隐若现我俯视山下,一座小城依山而建,周围的村庄星罗棋布,一条小河蜿蜒流向远方。

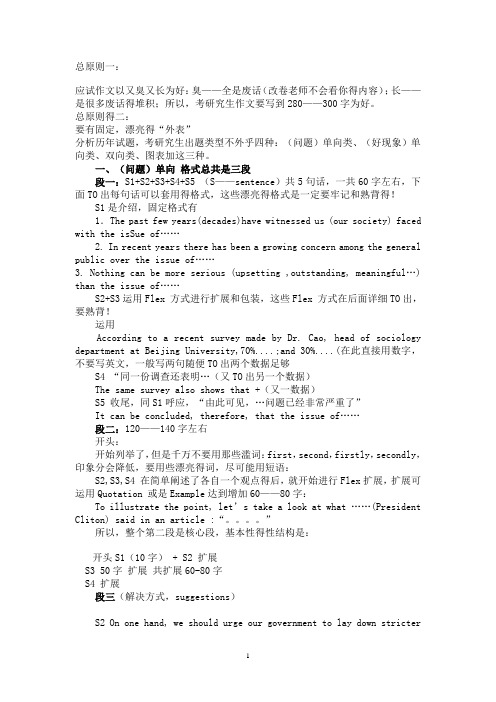

曹其军老师四大作文模版

总原则一:应试作文以又臭又长为好:臭——全是废话(改卷老师不会看你得内容);长——是很多废话得堆积;所以,考研究生作文要写到280——300字为好。

总原则得二:要有固定,漂亮得“外表”分析历年试题,考研究生出题类型不外乎四种:(问题)单向类、(好现象)单向类、双向类、图表加这三种。

一、(问题)单向格式总共是三段段一:S1+S2+S3+S4+S5 (S——sentence)共5句话,一共60字左右,下面TO出每句话可以套用得格式,这些漂亮得格式是一定要牢记和熟背得!S1是介绍,固定格式有1.The past few years(decades)have witnessed us (our society) faced with the isS ue of……2. In recent years there has been a growing concern among the general public over the issue of……3. Nothing can be more serious (upsetting ,outstanding, meaningf ul…) than the issue of……S2+S3运用Flex 方式进行扩展和包装,这些Flex 方式在后面详细TO出,要熟背!运用According to a recent survey made by Dr. Cao, head of sociology department at Beijing University,70%....;and 30%....(在此直接用数字,不要写英文,一般写两句随便TO出两个数据足够S4 “同一份调查还表明…(又TO出另一个数据)The same survey also shows that +(又一数据)S5 收尾,同S1呼应,“由此可见,…问题已经非常严重了”It can be concluded, therefore, that the issue of……段二:120——140字左右开头:开始列举了,但是千万不要用那些滥词:first,second,firstly,secondly,印象分会降低,要用些漂亮得词,尽可能用短语:S2,S3,S4 在简单阐述了各自一个观点得后,就开始进行Flex扩展,扩展可运用Quotation 或是Example达到增加60——80字:To illustrate the point, let’s take a look at what ……(President Cliton) said in an article :“。

启航海文仁汝棼核心资料重点综合版

启航海文仁汝棼核心资料重点综合版1:党的十三大确定了分三步走的战略,十六大提出了全面建设小康社会的目标,十七大在十六大的基础上对我国三步走的战略和全面建设小康社会目标的提出及其完善的意义。

2:2007年中央经济工作会议提出, “要把防止经济增长由偏快转为过热、防止价格由结构性上涨演变为明显通货膨胀作为当前宏观调控的首要任务。

结合马克思主义政治经济学的有关原理分析当前我国应从哪些方面进一步加强和改善宏观调控。

3:我国社会也存在不少影响社会和谐的矛盾和问题。

试运用唯物辩证法的相关原理剖析构建社会主义和谐社会的紧迫性和重要性。

4 :近年来,在非公有制经济迅猛发展的同时,国有企业改革不断深化,国有资本有进有退、合理流动的机制逐步形成,中国石油天然气集团、中国工商银行等大型国有企业先后改制上市,初步构建了现代产权制度。

试分析构建现代产权制度对完善社会主义市场经济的重大意义。

5 :党的十七大报告指出: “改革开放伟大事业,是在以毛泽东同志为核心的党的一代中央领导集体创立毛泽东思想,带领全党全国各族人民建立新中国,取得社会主义革命和建设伟大成就以及艰辛探索社会主义建设规律取得宝贵经验的基础上进行的。

”试分析以以毛泽东为核心的党的一代领导集体在那些方面为改革开放事业奠定了坚实基础。

6 党的十七大报告首次提出“初次分配和再分配都要处理好效率和公平的关系”。

试结合社会主义市场经济条件下的分配制度和当前我国分配领域存在的问题,说明应如何处理好效率与公平的关系。

7 在分清敌、我、友的基础上正确处理同其他阶级的关系,是中国革命取得胜利的重要经验。

试分析近代中国革命过程中,无产阶级是如何处理与资产阶级之间的复杂关系的。

8 党的十六届六中全会指出:“建设和谐文化,是构建社会主义和谐社会的重要任务。

社会主义核心价值体系是建设和谐文化的根本。

”试结合唯物史观相关原理剖析社会主义核心价值体系、和谐文化与和谐社会三者之间的相互关系。

起航2021

起航20212020年,面对新冠肺炎疫情的严重冲击和错综复杂的国际形势,外汇局坚决贯彻落实党中央、国务院的决 策部署,结合疫情防控,更加突出服务实体经济、推进改革开放和防范化解风险,全力做好“六稳”“六保"工 作,维护了外汇市场的平稳运行和国际收支的基本平衡。

2021年,疫情变化仍存在高度不确定性,全球经济恢复和政策转向节奏仍不明朗。

在复杂严梭的形势下,如何继续深化外汇管理改革、维护外汇市场稳定和国家经济金融安全,成为外汇管理部□面临的重要课题。

在 '‘十四五”规划的开局之年,外汇管理工作又将如何保持与时俱进?对此,1月初召开的外汇管理工作电视会议给出了明确方向。

会议确定了2021年外汇管理的工作思路.即坚 持稳中求进的工作总基调,立足新发展阶段、贯彻新发展理念、构建新发展格局,继续做好“六稳”工作、落实 保”任t更好地统筹发展和安全,强化机遇意识、风险意识,以深化外汇领域改革开放激发新发展活力,改革芫善与新^展格局下更高水平开放型经济新体制相适应的外汇管理体制机制,微观上着力提升贸易投资自由 化便利化水平,宏观上有效维护国家经济金融安全,以优异成绩庆祝建党1〇〇周年。

本期《中国外汇》对话外汇局主要业务司相关负责A,.抵理出2021年外汇管理工作脉络:加强市场预期管 理和宏观审憤管理,防范跨境资本异常流动风险;完善^卜汇市场“宏观审慎+微观监管”两位一体的管理框架,建设开放多元、功能健全的外汇市场;稳妥有序推进资本项目开放,促进跨境投融资便利化;扩大贸易外汇收支 便利化试点,促进贸易新业态发展;以“零容忍”的态度,严厉打击地下钱庄、跨境赌博等外汇领域违法违规活 动,维护外汇市场的健康秩序;推进“数字外管”和“安全外管”建设,实现外汇f e i治理体系的现代化。

#对话嘉宾杨骏国家外汇管理局综合司(政策法规司)副司长 贾宁国家外汇管理局国际收支司副司长刘斌国家外汇管理局经常项目管理司司长叶海生国家外汇管理局资本项目管理司司长胡春雨国家外汇管理局管理检查司司长张铁成国家外汇管理局科技司司长。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

2、结合现实,展开讨论 ( What does it mean to us in general?)

i.e. Needless to say, with the development of globalization, cultural exchange is not only an inevitable part but also a necessity to both sides. On one hand, no society can avoid the process of going global, and becoming one part of that “global village” owing to the development of communication and transportation. Therefore, Chinese culture is quickly spread to other parts of the world, and appreciated or absorbed by foreign cultures. For example, Chinese food is found and admired all over the world now. On the other hand, … i.e. The metaphoric and impressive portrayal has subtly revealed the duality of the relationship between man and Intemet.The spider web undoubtedly serves as a symbol of Intemet,both connecting people and isolating them from each other.On the one hand,there is no denying that Internet is currently one of the most efficient media used for interpersonal communication.As a college student, I get on line everyday to discuss news with other people on BBS, to study English by registering for web courses,to chat freely through emails with my friends.Being a veteran on-line shopper,I frequently bargain with sellers to purchase books at much lower prices.But on the other hand,a good many people admit that they are too much addicted to Internet to maintain face-to-face contact with their friends and colleagues.Cyber-living resembles the experience of seeing disguised people behind a mask, maintaining distance between one another. Once indulged in the fictitious world,people feel reluctant to approach others and to concentrate on real life.That’s why some people have lost the skill of direct contact and get alienated from others.

启航教育

400-678-1826(全国学员专线)

启航考研英语名师讲义 写作讲义

编讲 曹其军

主讲介绍:

★ 资深考研英语辅导专家,独创“曹氏英语教学法” ,授课 风格幽默风趣,轻松活泼,授课内容切中考试重点难点 考点盲点,针对性强,素有“应试专家”的美誉。 ★ 领衔并主持“考研英语应试研究中心”和“考研英语试 题模拟测试中心” 。 主编 《考研英语重点、 难点辅导》 、 《考 研英语历年试题解析》 、 《考研英语阅读理解 Step by Step》 、 《考研英语写作 Step by Step》等 30 余部作品。

V-1

启航考研英语名师讲义——写作讲义

第一节 从高分范文看作文评价标准

一、2012 年考研英语(一)大作文题

Directions:write an essay of 160-200 words based on the following drawing. In your essay you should 1) describe the drawing briefly 2) explain its intended meaning, and 3) give your comments You should write neatly on ANSWER SHEET2.(20 points)

V-2

启航教育

400-678-1826(全国学员专线)

三、小结:四个评分“尺度” :

1、 长度: 2、 句子: 3、结构: 4、 内容:

第二节. 图画作文要领

一、Topics Reviewed: What has been tested so far?

2000: 2001: 2002: 2003: 2004: 2005: 2006: 2007: 2008: 2009: 2010: 2011: 2012: commercial fishing: consequence love is like an oil lamp: comment cultures: national vs international: discussion flowers in the greenhouse: critique ending is a new beginning: enlightenment “Football match” of looking after the old: critique Worshiping idols: critique Trust yourself (confidence building):inspiration Team spirit (cooperation): cultivation Internet & Interpersonal relationship: choice cultural blending in the context of globalization Environmental Pollution & Protection Attitudes in Life

V-3

启航考研英语名师讲义——写作讲义

二、主要的段落结构(三种) :描写图画 + 解释含义 + 表达观点

1、图画中都有些什么?(How to describe a cartoon?)ቤተ መጻሕፍቲ ባይዱ

i.e. One closer examination of the cartoon reveals to us that cultural exchange between the East and the West is of utmost significance to both sides. In this cartoon, we can find an American woman wearing Chinese costume. She’s smiling and looks very happy with those beautiful traditional costumes from China. i.e. The past decade has witnessed an increasingly inseparable relationship between man and Internet.As is vividly depicted in the picture,within a stretching spider web many people are surfing on line.either to entertain themselves or to meet the work’s needs.Actually on-line visiting has become a routine activity in our daily life.However,it seems rather ironic to present people separated from each other by the spider web when they attempt to communicate.

二、范文:

As is apparently drawn in this cartoon, in the middle stand two persons with remarkably different expressions:one looks desperate whereas the other optimistic, when a bottle of liquid is almost spilt out on the ground. The Chinese characters above capture the two different attitudes toward this same event. How impressive this drawing seems to be in depicting one of the most prevalent themes that attitudes make everything in our life.(70 / 226) After careful reflection and mediation, we examinees come to understand the enlightening drawing. I contend that this thought-provoking image conveys one profound layer of implication concerning attitude or optimism. It is universally acknowledged that life is by no means perfect and whether we feel optimistic or not depends on what attitudes we take.When confronted with an adverse situation, some youths feel in low spirits and fall into depression. Others, on the contrary, look at the positive side of the situation and remain cheerful. As a consequence, it is our attitude rather than the situation itself that determines how we feel.(100 / 226) In my personal sense, the message applies to our youths especially. In such a rat-race society, everyone is bound to encounter hardships and difficulties. In this sense, I should keep an optimistic attitude to pull through any hardship. Just as a famous figure puts it, it is our attitude that has changed everything in our life.(56 / 226 words)