Comparative Genomics Phylogenetic footprinting and shadowing

真核生物水平基因转移

Horizontal gene transfer in eukaryotic evolution真核生物进化中的水平基因转移Abstract | Horizontal gene transfer (HGT; also known as lateral gene transfer) hashad an important role in eukaryotic genome evolution, but its importance is often overshadowed by the greater prevalence and our more advanced understanding of gene transfer in prokaryotes. Recurrent endosymbioses and the generally poor sampling of most nuclear genes from diverse lineages have also complicated the search for transferred genes. Nevertheless, the number of well-supported cases of transfer fromboth prokaryotes and eukaryotes, many with significant functional implications, is now expanding rapidly. Major recent trends include the important role of HGT in adaptation to certain specialized niches and the highly variable impact of HGT in different lineages.概括|水平基因转移(HGT;也被称为侧向基因转移)在真核基因组进化中起了一个非常重要的作用,但是它的重要性往往因为我们对高度流行的疾病和原核生物基因转移更关注而被遮掩了。

大肠杆菌的MLST分型

Address: 1INSERM UMR570, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris Descartes, Paris, France, 2Hôpital Avicenne, AP-HP; UFR Santé, Médecine, Biologie Humaine, Université Paris 13, Bobigny, France, 3Biodiversity of Emerging Bacterial Pathogens, Institut Pasteur, 28 rue du Dr Roux, 75724 Paris, France, 4Genotyping of Pathogens and Public Health, Institut Pasteur, 28 rue du Dr Roux, 75724 Paris, France, 5Faculté de Médecine, Université René Descartes, Hôpital Necker-Enfants Malades, AP-HP, Paris, France, 6Institut Pasteur, CNRS URA3012, Paris, France and 7INSERM U722, Faculté de Médecine, Université Paris Diderot, Paris, France

This article is available from: /1471-2164/9/560

© 2008 Jaureguy et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Baden-Württemberg.

AcknowledgementsWe thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for financial support.S.H.was supported by a grant of the Landesgraduiertenfo¨rderung Baden-Wu ¨rttemberg.References1H.K.Moghadam et anization of Hox clusters in rainbow trout(Oncorhynchus mykiss ):a tetraploid model species.J.Mol.Evol.(in press)2Aparicio,S.et al .(2002)Whole-genome shotgun assembly and analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes .Science 297,1301–13103Jaillon,O.et al .(2004)Genome duplication in the teleost fish Tetraodon nigroviridis reveals the early vertebrate proto-karyotype.Nature 431,946–9574Amores,A.et al .(2004)Developmental roles of pufferfish Hox clusters and genome evolution in ray-fin fish.Genome Res.14,1–105Chiu,C-h.et al .(2004)Bichir Hox A cluster sequence reveals surprising trends in ray-finned fish genomic evolution.Genome Res.14,11–176Powers,T.P .and Amemiya, C.T.(2004)Evolutionary plasticity of vertebrate Hox genes.Curr.Genomics 5,459–4727Powers,T.P.and Amemiya,C.T.(2004)Evidence for a Hox 14paralog group in vertebrates.Curr.Biol.14,R183–R1848Garcia-Ferna`ndez,J.(2005)Hox,ParaHox,ProtoHox:facts and guesses.Heredity 94,145–1529Santini,S.et al .(2003)Evolutionary conservation of regulatory elements in vertebrate hox gene clusters.Genome Res.13,1111–112210Amores,A.et al .(1998)Zebrafish hox clusters and vertebrate genomeevolution.Science 282,1711–171411Naruse,K.et al .(2000)A detailed linkage map of medaka,Oryziaslatipes :comparative genomics and genome evolution.Genetics 154,1773–178412Ledje,C.et al .(2002)Characterization of Hox genes in the bichir,Polypterus palmas .J.Exp.Zool.294,107–11113Hoegg,S.et al .(2004)Phylogenetic timing of the fish-specific genomeduplication correlates with the diversification of teleost fish.J.Mol.Evol.59,190–20314Fried,C.et al .(2004)Exclusion of repetitive DNA elements fromgnathostome Hox clusters.J.Exp.Zoolog.B Mol.Dev.Evol.302,165–17315Chiu,C-h.et al .(2002)Molecular evolution of the Hox A cluster in thethree major gnathostome lineages.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.99,5492–549716Prohaska,S.J.et al .(2004)Surveying phylogenetic footprints in largegene clusters:applications to Hox cluster duplications.Mol.Phylo-genet.Evol.31,581–60417Prohaska,S.J.et al .(2004)The shark Hox N cluster is homologous tothe human Hox D cluster.J.Mol.Evol.58,212–21718Wagner,G.P.et al .(2004)Divergence of conserved non-codingsequences:rate estimates and relative rate tests.Mol.Biol.Evol.21,2116–212119Wagner,G.P .et al.Molecular evolution of duplicated ray-finned fishHox A clusters:increased synonymous substitution rate and asym-metrical co-divergence of coding and non-coding sequences.J.Mol.Evol.(in press)20Tagle,D.A.et al .(1988)Embryonic epsilon and gamma globin genes ofa prosimian primate (Galago crassicaudatus ).Nucleotide and amino acid sequences,developmental regulation and phylogenetic footprints.J.Mol.Biol.203,439–45521Chiu,C-h.et al .(2002)Molecular evolution of the Hox A cluster in thethree major gnathostome lineages.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.99,5492–549722Loots,G.G.et al .(2000)Identification of a coordinate regulator ofinterleukins 4,13,and 5by cross-species sequence comparisons.Science 288,136–1400168-9525/$-see front matter Q 2005Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.06.004Discovering functional relationships:biochemistry versus geneticsSharyl L.Wong,Lan V.Zhang and Frederick P.RothDepartment of Biological Chemistry and Molecular Pharmacology,Harvard Medical School,250Longwood Ave,Boston,MA,02115USABiochemists and geneticists,represented by Doug and Bill in classic essays,have long debated the merits of their methods.We revisited this issue using genomic data from the budding yeast,Saccharomyces cerevisiae ,and found that genetic interactions outperformed protein interactions in predicting functional relation-ships between genes.However,when combined,these interaction types yielded superior performance,convin-cing Doug and Bill to call a truce.IntroductionFor more than ten years,Doug,a retired biochemist,and Bill,a retired geneticist,have lived on a hill overlooking acar factory,debating their strategies for reverse engineer-ing a car (see:http://www2.biology.ualberta.ca/locke.hp/dougandbill.htm ).Doug advocated rolling up his sleeves,getting under the hood and determining how the parts fit together.Bill preferred tying the hands of a different car-factory worker each morning,then relaxing with a cup of coffee and later examining the cars that emerged from the factory.One day,Doug and Bill strolled over the next hill.In the midst of debate,they encountered Sharyl,a graduate student in computational genomics.Having overheard their debate,she interjected,‘I don’t know much about cars,but I detect an analogy to biochemistry and genetics.I’m trying to discover functional relationships between genes and proteins in yeast and I wonder which of your strategies would work best.’Corresponding author:Roth,F.P.(fritz_roth@).Available online 27June 2005TRENDS in Genetics Vol.21No.8August 2005424Differing approaches to determining gene functionTo discover functional relationships,Doug would ask,‘Which proteins physically interact with my favorite protein?’By contrast,Bill would perturb the DNA sequence of a gene and observe the consequences in vivo, asking‘What are the genetic interaction partners of my favorite gene?’In other words,‘Which genes produce surprising phenotypes if mutated in combination with my favorite gene?’Sharyl described how thefields of biochemistry and genetics had‘gone genomic,’scaling up their classical approaches to discover functional relation-ships with ever-greater efficiency.Their resulting sys-tematic studies offered a playingfield on which to assess Doug and Bill’s dilemma.Sharyl then wondered,‘Which type of interaction–protein or genetic–is better at revealing functional relationships?’She pulled out her laptop computer and set to work(Figure1).Protein versus genetic interactions in predicting functional relationshipsBecause‘gene function’is vaguely defined,Sharyl used the Gene Ontology(GO)vocabulary,which describes gene products in terms of biological process,cellular component and molecular function(/) [1,2].She defined three measures of functional relatedness for a pair of genes:(i)shared GO biological process(shared process);(ii)shared GO cellular component(shared component);and(iii)shared GO molecular function (shared function).For example,if two genes were assigned to the same GO biological process category,Sharyl considered the gene pair to have a‘shared process’.To avoid associations between genes in broadly defined categories,she considered only specific GO categories–those to which200or fewer genes(out of w6000total yeast genes)were assigned,including genes assigned to more specific daughter categories.To represent the biochemists,she chose a high-confidence protein-inter-action data set based on affinity purification followed by mass spectrometry(APMS)[3].For the geneticists,she fielded a recent systematic genetic-interaction data set[4] (Tables1and2in the supplementary data online;Box1).To level the playingfield,she considered only the 104409gene pairs(the‘arena’)assessed by both approaches and for which both genes in each pair had a GO annotation.In this arena,the number of gene pairs sharing a specific GO process,component or function was 3841,1803and1139,respectively.The arena contained48 biochemical interactions and729genetic interactions, derived primarily from screens involving the17genes used both as baits in the protein-interaction screens and as query genes crossed to4500mutants in synthetic genetic array(SGA)analysis.Interestingly,there was no overlap between the protein and genetic interactions(Table3, supplementary data online).A previous related study[5]did not consider whether gene pairs had been assessed for both types of interaction and used literature-derived interaction data,which are subject to inspection bias.With a few taps on her keyboard,Sharyl let the games begin.Two proteins exhibiting a protein interaction had a shared process,component or function42%(P Z2e-17), 31%(P Z2e-15)and29%(P Z1e-16)of the time,respect-ively.Genetic interactions were uniformly less-accurate indicators of shared function,with corresponding rates ofFigure1.Protein interaction versus genetic interaction.(a)A protein interaction exists when two proteins are in physical contact,either direct or indirect(e.g.within the same protein complex).(b)By contrast,a genetic interaction is determined between two genes by comparing their single-mutant phenotypes with their double-mutant phenotypes.Here,we focus on synthetic sick or lethal genetic interactions,in which mutation of two genes causes a more severe growth defect (represented by the face marked with an X)than mutation of either alone (represented by happy faces)[4,19].Yellow and blue circles represent proteins and rectangles represent genes.Rectangles marked with an X represent mutated genes.TRENDS in Genetics Vol.21No.8August2005425 19%(P Z 2e-63),15%(P Z 2e-66)and 8%(P Z 2e-28).However,genetic interactions detected gene pairs with shared function with much higher sensitivity (4–6%)than biochemical interactions (0.5–1.2%;Table 4in the supplementary data online).When considering different physical-interaction data sets [3,6](Box 1),genetic interactions were consistently more sensitive and some-times more accurate (see Glossary;Table 4,supplemen-tary data online).Thus,it was difficult to declare a clear winner.Combining genetic and protein interactions with other dataAre genetic interactions combined with other types of evidence more informative than protein interactions combined with other evidence?Rather than considering each type of interaction in isolation,several groups have previously combined heterogeneous data,using machine learning approaches to predict some property of a gene pair or to predict gene function [7–12].Therefore,Sharyl combined multiple types of evidence [11]–including co-localization [13],sequence homology [14],correlated mRNA expression [15,16]and chromosomal distance (Table 5,supplementary data online)–to predict shared function.She chose a previously described probabilistic-decision tree approach [12]and compared performance with and without the benefit of protein and/or genetic-interaction data.For each of shared process,component,and function and for each choice of input data,she performed cross-validation:she randomized all gene pairs in the arena into four groups,and successively scored each group using a model trained on the remaining three.She then compared the prediction score of each gene pair with its corresponding shared process,function or component status.A plot of true-versus false-positive rates revealed that genetic and protein interactions were comparable at low sensitivities;however,as sensitivity increased,genetic-interaction data enhanced performance more than protein-interaction data.This trend was observed for shared process (Figure 2),component (Figure 1a,supplementary data online)and function (Figure 1b,supplementary data online).Doug,the biochemist,began to despair.Before Bill could begin to gloat,however,Sharyl showed that genetic-and protein-interaction data together gave markedly better results than either alone,suggesting that each offers distinctly different types of information.Although protein interactions can represent associations between genes in the same complex or physically connected pathway,genetic interactions canadditionally reflect relationships between genes in physi-cally non-interacting pathways.She repeated this anal-ysis with another APMS protein-interaction data set [6]and then with the union of two yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H)data sets [17,18](Tables 1and 3,and Figures 2and 3in the supplementary data online),altering the arena appropriately.In each case,genetics beat biochemistry by a slim margin,but the combination of these comp-lementary interaction types outperformed either alone.Sharyl’s results convinced Doug and Bill to shake hands and head back over the hill .until new data or new technology call for a rematch.GlossaryAccuracy:is defined as the number of gene pairs with the same function divided by the number of gene pairs with the given predictive characteristic.For example,the number of pairs that both genetically interact and have shared process divided by the number of pairs that genetically interact.Sensitivity (or true positive rate):is defined as the number of gene pairs with the same function that pass a given score threshold (i.e.true positives)divided by the total number of gene pairs with the same function.False positive rate (or 1–specificity):is defined as the number of gene pairs without the same function that pass a given score threshold (i.e.false positives)divided by the total number of gene pairs without the same function.Figure 2.Performance when predicting ‘shared process’with and without genetic [4]and/or protein-interaction data from Gavin et al.[3].(a)Each point on the curve represents performance at a given threshold score (such that pairs above that threshold are predicted to have shared function).‘P’and ‘G’represent protein and genetic-interaction data ing all high-throughput data yields the best prediction performance.Notably,this performance is impaired more by the omission of genetic interaction data than by omission of protein interaction data.The same information is shown in (b)but in finer detail.TRENDS in Genetics Vol.21No.8August 2005426AcknowledgementsWe thank C.Boone,H.Fraser,and T.Hughes for helpful comments,O.King for mathematical advice and G.Berriz for his Gene Ontology parser.S.L.W.was supported by the Ryan Foundation and the Milton Fund of Harvard University.L.V.Z.was supported by the Fu Foundation,the Ryan Foundation and the American Association of University Women.This work was also supported by Funds for Discovery provided by John Taplin,a Howard Hughes Medical Institute institutional grant to Harvard Medical School and the National Institutes of Health/National Human Genome Research Institute.Supplementary dataSupplementary data associated with this article can be found at doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.06.006References1Harris,M.A.et al .(2004)The Gene Ontology (GO)database and informatics resource.Nucleic Acids Res.32Database issue,D258–2612Dwight,S.S.et al .(2004)Saccharomyces genome database:under-lying principles and organisation.Brief.Bioinform.5,9–223Gavin,A.C.et al .(2002)Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes.Nature 415,141–1474Tong,A.H.et al .(2004)Global mapping of the yeast genetic interaction network.Science 303,808–8135Deng,M.et al .(2004)An integrated probabilistic model for functional prediction of put.Biol.11,463–4756Ho,Y.et al .(2002)Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry.Nature 415,180–1837Troyanskaya,O.G.et al .(2003)A Bayesian framework for combining heterogeneous data sources for gene function prediction (in Sacchar-omyces cerevisiae ).Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.100,8348–83538Lee,I.et al .(2004)A probabilistic functional network of yeast genes.Science 306,1555–15589Chen,Y.and Xu,D.(2004)Global protein function annotation through mining genome-scale data in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae .Nucleic Acids Res.32,6414–642410Zhang,L.V .et al .(2004)Predicting co-complexed protein pairs usinggenomic and proteomic data integration.BMC Bioinformatics 5,3811Wong,S.L.et al .(2004)Combining biological networks to predictgenetic interactions.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A.101,15682–1568712King,O.D.et al .(2003)Predicting gene function from patterns ofannotation.Genome Res.13,896–90413Kumar,A.et al .(2002)Subcellular localization of the yeast proteome.Genes Dev.16,707–71914Altschul,S.F.et al .(1997)Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST:a newgeneration of protein database search programs.Nucleic Acids Res.25,3389–340215Hughes,T.R.et al .(2000)Functional discovery via a compendium ofexpression profiles.Cell 102,109–12616Cho,R.J.et al .(1998)A genome-wide transcriptional analysis of themitotic cell cycle.Mol.Cell 2,65–7317Ito,T.et al .(2001)A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore theyeast protein interactome.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S. A.98,4569–457418Uetz,P .et al .(2000)A comprehensive analysis of protein-proteininteractions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae .Nature 403,623–62719Tong,A.H.et al .(2001)Systematic genetic analysis with orderedarrays of yeast deletion mutants.Science 294,2364–23680168-9525/$-see front matter Q 2005Elsevier Ltd.All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.06.006TRENDS in Genetics Vol.21No.8August 2005427。

comp2

Outline

• All-against-all Self-comparison of Proteome • Between-proteome Comparisons • Family and Domain Analysis • Ancient Conserved Regions (ACRs) • Horizontal Gene Transfer • Functional Classification of Genes • Gene-order Comparisons

• The functions of human genes and other DNA regions can be

revealed by studying their counterparts in lower organisms.

Outline

• All-against-all Self-comparison of Proteome • Between-proteome Comparisons • Family and Domain Analysis • Ancient Conserved Regions (ACRs) • Horizontal Gene Transfer • Functional Classification of Genes • Gene-order Comparisons

Between-Proteome Comparisons : Why?

• To identify orthologs, gene families, and domains • Orthologs: (proteins that share a common ancestry & function)

Genome Analysis II

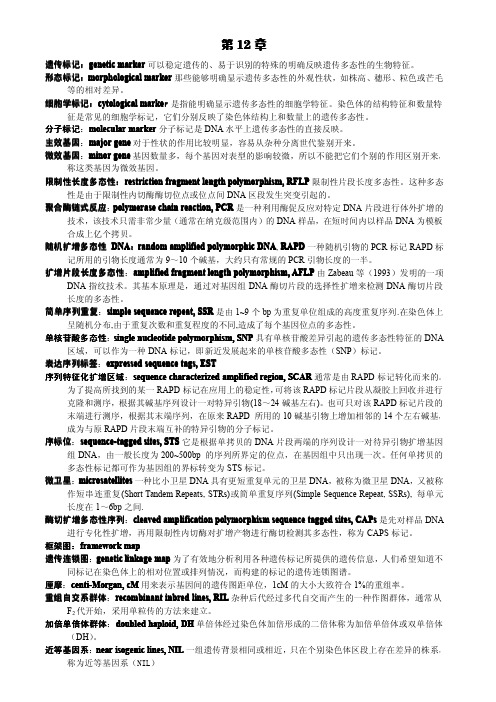

植物生技名词解释,整理答案版

第12章遗传标记:genetic marker可以稳定遗传的、易于识别的特殊的明确反映遗传多态性的生物特征。

:morphological marker那些能够明确显示遗传多态性的外观性状,如株高、穗形、粒色或芒毛形态标记形态标记:等的相对差异。

细胞学标记:cytological marke r是指能明确显示遗传多态性的细胞学特征。

染色体的结构特征和数量特征是常见的细胞学标记,它们分别反映了染色体结构上和数量上的遗传多态性。

分子标记:molecular marker分子标记是DNA水平上遗传多态性的直接反映。

主效基因:major gene对于性状的作用比较明显,容易从杂种分离世代鉴别开来。

微效基因:minor gene基因数量多,每个基因对表型的影响较微,所以不能把它们个别的作用区别开来,称这类基因为微效基因。

:restriction fragment length polymorphism,RFLP限制性片段长度多态性。

这种多态限制性长度多态性限制性长度多态性:性是由于限制性内切酶酶切位点或位点间DNA区段发生突变引起的。

聚合酶链式反应:polymerase chain reaction,PCR是一种利用酶促反应对特定DNA片段进行体外扩增的技术,该技术只需非常少量(通常在纳克级范围内)的DNA样品,在短时间内以样品DNA为模板合成上亿个拷贝。

随机扩增多态性DNA:random amplified polymorphic DNA,RAPD一种随机引物的PCR标记RAPD标记所用的引物长度通常为9~10个碱基,大约只有常规的PCR引物长度的一半。

扩增片段长度多态性:amplified fragment length polymorphism,AFLP由Zabeau等(1993)发明的一项DNA指纹技术。

其基本原理是,通过对基因组DNA酶切片段的选择性扩增来检测DNA酶切片段长度的多态性。

简单序列重复:simple sequence repeat,SSR是由1~9个bp为重复单位组成的高度重复序列.在染色体上呈随机分布,由于重复次数和重复程度的不同,造成了每个基因位点的多态性。

混养反硝化硫细菌thiopseu...

摘要随着社会经济的迅速发展,制药和石油化工等行业的工业废水排放量逐年增加。

含硫、含氮和高浓度化学需氧量(COD)是工业废水污染物组成的典型特征。

这类废水未达标排放到环境中会引起富营养化等问题。

碳氮硫共脱除工艺包含硫酸盐-有机物去除单元,反硝化脱硫单元,生物硫回收单元和硝化单元。

此工艺将硫酸盐还原与反硝化脱硫过程耦合,实现有机物、硫酸盐和氮氧化物的高效去除。

然而此工艺存在污染物去除和资源化效率易受进水负荷干扰,活性污泥中微生物群落功能机制不明确和单质硫产率较低的问题。

本研究在碳氮硫共脱除反应器中分离出一株能够在厌氧条件下同时代谢COD、硫化物和氮氧化物的功能菌株X2。

基于16S rRNA基因的系统进化分析表明菌株X2属于Pseudomonadaceae科,与Pseudomonas caeni有较近的亲缘关系。

它们在系统进化树中与Pseudomonadaceae科其他近缘物种明显分离,形成一个新的进化单元。

采用Pseudomonas caeni作为参考菌株,利用多相分类的方法对菌株X2进行鉴定,结果表明:与Pseudomonas caeni相比较,菌株X2X2代表Pseudomonadaceae科中一个新属的模式种。

依据其硫氧化和反硝化的生理特性命名为Thiopseudomonas denitrificans X2。

根据能量和营养来源差异,设置不同的条件分析菌株X2的代谢特征。

菌株X2可以分别在异养反硝化、混养硫氧化-反硝化和自养硫氧化-反硝化条件下生长代谢。

它可以利用有机或者无机碳作为营养来源,也可以利用硫化物或有机物氧化作为能量来源,属于兼性化能无机营养型硫细菌。

在菌株X2代谢过程中,高浓度电子受体存在的条件下,硫化物不发生过度氧化。

氧化反应的主要产物为颗粒状单质硫。

功能基因表达分析表明硫氧化基因fccAB和反硝化基因nirS都是不受底物诱导的持家基因。

在混养硫氧化-反硝化条件下,这两种基因的表达量都显著低于反硝化条件。

通过基因对比鉴别两个物种的方法专业术语

通过基因对比鉴别两个物种的方法专业术语基因对比是一种常用的方法,用于鉴别两个物种或者确定亲缘关系。

通过比较两个物种的基因组序列、基因组组成、基因家族等,可以揭示其相似性和差异性,并进一步了解物种的进化历史和可能的共同祖先。

以下是一些与基因对比相关的专业术语:1. 基因组学(genomics): 研究整个基因组的构成和功能的学科领域。

基因组学的发展使得基因对比更加精确、全面。

2. 基因组序列(genome sequence): 指其中一物种的完整基因组序列。

通过对两个物种的基因组序列进行比较,可以揭示共同的基因和变异的基因。

3. 基因组组装(genome assembly): 将大量DNA片段拼接成连续的序列,以获得物种的完整基因组序列。

基因组组装有助于将两个物种的基因组进行对比,发现其相似性和差异性。

4. 突变(mutation): 基因组中发生的变异,可分为点突变、插入突变和缺失突变等不同类型。

基因对比可以揭示两个物种之间出现的突变情况,进而推断其进化过程。

5. 保守基因(conserved gene): 在不同物种中高度保守的基因序列,其功能在物种间保持相似。

基因组对比可以发现哪些基因在两个物种之间保持高度相似,并进一步了解这些基因之间的功能和作用。

6. 基因家族(gene family): 指具有相似基因序列和功能的基因集合。

通过对两个物种的基因家族进行比较,可以发现基因家族的扩张、收缩和进化过程。

7.等位基因(alleles): 在同一基因座上不同的基因形式。

基因组对比可以帮助鉴别两个物种中的等位基因,并进一步理解这些等位基因与物种间的差异和进化关系。

8. 同源基因(homologous genes): 指在不同物种中具有相同起源的基因。

通过对两个物种的同源基因进行比较,可以了解这些基因在不同物种间的进化和功能演化。

9. 进化树(phylogenetic tree): 通过对基因组对比数据进行系统学分析,建立物种间的进化关系图谱。

6-生物信息学-转录调控分析

出现的概率相互独立。 矩阵每一列表示模体相应位置上四种碱基 出现的概率。 对于长度为n的模体,碱基i(i={A, C, G, T})在模体第j 个位置上出现的频率为q i,j,则整个模体用矩阵M表示如下:

q A,1 q A,2 ∙∙∙ q A,n q C,1 q C,2 ∙∙∙ q C,n

G,1

REDUCE 算法:以模体出现的次数作为自变量

来进行简单线性回归

MatrixREDUCE算法:用位置频率矩阵的打分作

为自变量进行回归

MARSMotif-M算法:多变量适应回归模型

转录因子结合位点分析可利用网络资源

Category Single motif discovery Program MobyDick YMF Consensus MEME Gibbs Sampler URL /mobydick/ /software.html /software.html /meme/intro.html /gibbs/gibbs.html

High-throughput Techniques in Transcriptional Regulation Analysis

一、ChIP技术

创立者:

20世纪80年代末

Alexander Varshavsky等人

(Cell. 1988,53(6): 937-947 )

基本实验过程: 甲醛交联,稳定蛋白质-DNA复合物 裂解细胞,分离蛋白质-DNA复合物 加入特异性抗体,沉淀蛋白质-DNA复合物 去交联,纯化DNA 应用PCR技术,特异性扩增目的DNA片段

M= q

q G,2 ∙∙∙ q G,n

q T,1 q T,2 ∙∙∙ q T,n

(三)序列标识图(sequence logo)

水产专业英语词汇

Aquaculture水产养殖Genetics 遗传学Genomics 基因组学Teleosts 硬骨鱼类Shellfish 贝类Shrimp 虾Physiologic 生理的Mechanisms 机制Maturity 成熟Bodyweight 体重Ovary 卵巢Testis 精巢Dimorphism 二态性Hormone 激素disulfide bonds 二硫键mediate 介导receptor 受体reproduction 繁殖immunity 免疫endocrine 内分泌的promotion 促进clone 克隆signal transduction 信号转导Transformation 转化Transfection 转染Infection 感Characterize 鉴定Gene 基因Pool 池塘Photoperiod 光周期water temperature 水温reproductive manipulation 繁殖调控egg 卵sperm 精子semen 精液female 雌鱼male 雄fertilization 受精volume 体积hatch 孵化gentle aeration 微充气larvae 仔鱼triplicate 重复3次dose 剂量Gonad 性腺RNA extraction RNA提取Ethanol 酒精Sex 性别Blood 血Brain 脑Eye 眼Gill 鳃Kidney 肾Intestine 肠Liver 肝Muscle 肌肉Pituitary 垂体Skin 皮肤Spleen 脾脏Stomach 胃Microscope 显微镜Aliquot 份Activate 激活Digestion 消化Protocol 实验计划Primer 引物Polymerase 聚合酶Reverse transcription 反转录Sequence 序列Fragment 片段Amplification 扩增Template 模板Cycle 循环Intron 内含子Exon 外显子Vertebrate 脊椎动物Kit 试剂盒Instruction 用法说明Agarose gel 琼脂糖胶Band 带Propagate 繁殖amino acid 氨基酸alignment 比对phylogenetic trees进化树marker 标记Quantitative 定量的Stage时期Procedure 程序Software 软件Concentration 浓度Motility 活力encoding region 编码区signal 信号residue 残基flounder 牙鲆common carp 鲤鱼grass carp 草鱼tissue 组织population 群体sex ratio 性比negative 负的positive 正的control 对照grow 生长production 生产molecular 分子的stock 群体sex determination mechanisms性别决定机制superfemale 超雌个体progeny 后代feeding 喂养manipulation 管理environment 环境study 研究species 种类catfish 鲶鱼microsatellite 微卫星elucidate 阐明further investigations 进一步的研究significantly 显著地spawn 产卵expression 表达up-regulate 上调fold 倍gynogenesis 雌核发育homozygosity 纯合性meiotic减数的irradiate灭活heterologous 异源的cold shock冷休克diploid 二倍体的morphology形态homogamete同配marine 海洋flatfish比目鱼coastal areas沿海地区adult成体individual个体investment投资chromosome染色体approach方法monosexual单性的second meiotic division第二次减数分裂induce诱导mitogynogenesis卵裂雌核发育the first mitotic division 第一有丝分裂homologous同源的development发育paternal父母的offspring子代Nowadays当前Cryopreserve冷冻Technique技术Practical实际的Feasible可行的Neomal伪雄鱼Theoretical理论的genetic diversity遗传多样性sex control性别控制lab 实验室sex differentiation性分化heterozygosity杂合度recombination重组locus位点Additionally另外地Increment增量cultivated population养殖群体basepairs碱基对feasibility可行性parameter参数survival rate成活率gynogenetic population雌核发育群体thaw 解冻fisheries水产trial实验experiment实验storage保存liquid nitrogen液氮waterbath水浴appropriate适宜的condition条件haploid单倍体diploid二倍体hybrid杂交子treatment处理incubator培养容器percentage百分率embryo胚胎fertilization rate受精率survival rate 成活率data数据batch批randomly随机地sample取样classic经典的mixture混合物enzyme酶Ligation 连接Restriction限制性的Dilute稀释pre-amplification预扩automatic自动的denaturation变性anneal退火elongation延伸polyacrylamide gel聚丙烯酰胺胶silver staining银染molecular weight分子量allele等位基因index指数Initiation起始Duration持续Putative 推定的Polymorphism多态性linkage disequilibrium连锁不平衡artificial人工的diploidization二倍化optimization优化proportion比例sex reversal性逆转crossover交换incorporation整合eel鳗鲡summary摘要abstract摘要discussion 讨论references参考文献material and method材料和方法result结果title题目manuscript草稿revise修改review评审funding资助genetic sexing遗传性别鉴定Acknowledgments致谢Mechanism机制Article文章Foundation基础Methylation甲基化Aromatase芳香化酶Promoter启动子Androgen雄激素Estrogen雌激素Masculinization雄性化inverse relationship负相关suppress抑制genotypic sex determination遗传性别决定temperature-dependent sex determination温度性别决定thermosensitive period温度敏感期non-mammalian vertebrates非哺乳类脊椎动物sex steroid 性类固醇激素hypothesize假定pattern模式pathway 通路epigenetic表观遗传的nuclear细胞核transcription factors转录因子biosynthesis生物合成mutual共同的dinucleotides二核苷酸transcription start site转录起始位点overall总体上frequencies频率phenotype表型genotype基因型housekeeping gene持家基因exogenous外源的temperature-dependent温度依赖的sex-dependent性别依赖的rear养殖culture养殖stimulate刺激block阻止bioinformatic生物信息的putative推定的co-transfection共转染transcriptional activators转录激活因子luciferase reporter assay荧光素酶报告基因检测opening reading frame开放阅读框similarity相似度development发育demethylation去甲基化process过程sex differentiation性分化silence沉默DNA methyltransferases DNA甲基转移酶Identify 鉴定、发现Influence影响Consistent一致的Nutrition 营养Disease疾病Ingredient成分body size体长polygenic多基因的monosex populations单性群体determine确定match匹配consequence结果migration 迁移discern辨别hypermethylate超甲基化phenomenon现象conserved保守的threshold阈值scheme计划Fertlizating rate and survial rate are the important parameters of revaluatingThe quality of eggs受精率和成活率是评价卵的重要参数For improving the culturing production ,feeding and managent is very important饲养的管理对于提高养殖产量非常重要的The first step of breeding project design is the selection of the base population基础群的选择是育种计划设计的第一步The tilapia have a unique breeding characteristics: Male territory estoblisher and female mouth brooders罗非鱼具有奇特的繁殖习性:雄性领地占领者和雌性口腔孵化者The half-smooth tongue sole showed significand growth difference半滑舌鳎两性之间生长差异显著I have ten pools providing for culturing tilapia我有十个池塘养殖罗非鱼Reproductive manipulation is of importance for gonad maturity繁殖调控对鱼类的性腺成熟时非常重要的The hatching stage of sole eggs is 3 days舌鳎卵需要三天才能孵化Nowadays there are a lot of of nile tilapia femilies all over the world目前世界上有很多罗非鱼的品系Getting ready with data:gather all importantdata,analyses,plots and tables,organize results so that they follow a logical sequence,consolidate data plot and create figure for the manuscript,discuss the data with your advisor and note down important pointsFirst draft :identify tow or three important findings emerging from the experiments make them the central theme of the article,note good or bad writing styles in the literature ,some a simple and easy to follow some are just too complex,note the readership of the journal that you are considering ,prepare figures schemes and tables Structure of a scientific paper :title,abstract,toc graphics,introductionStructure of a scientific paper:experimentalsection ,result anddiscussion,conclusions,acknowledgments ,referencesSelecting a journal :each journal specializes area of research ,hence its readership varies .Aproper choice ofjournal can make a larger impact,get to know the focus and readership of the journal that you are considering general vs.specialized area journal,select 2 or 3 journals in the chosen area with relatively high impact factors.discuss with your advisor and decide on the journal,find out the journal's submission criteria and format.Submission:read the finalized paper carefully,check for accuiacy of figures and captions,are the figures correctly referred to in the text.get feedback from advisor and colleagues.make sure the paper is read by at least one colleague who is not familiar with the specific work.Revision and galley proof.。

生物信息学Bioinformatics

Analysis!

Definition Bioinformatics

an intersecting discipline

----is an interdisciplinary scientific field that develops methods and software tools for storing, retrieving, organizing and analyzing biological data.

Kir2.1

/

常用蛋白质三维结构观察和修改工具

工具

网站

备注

SwissPdbViewer Jmol

MolMol PyMol Rasmol VMD

/spdbv/

/

NCBI BLAST: Understand the Output

Raw score (S) Calculated by summing scored for individual aligned position. Scores for each position are calculated using a substitution matrix BLOSUM or PAM).

Biological Data

Biological Data

Simpleroject, HGP ----The challenge of huge data

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

– Clusters of ambiguity – 7-52kb from each end – Translocations between telomeres – Rapid evolution – Observed in Plasmodium falciparum (antigenic variation)

Results

– – – – Exact count of 5538 genes Better gene boundaries New introns identified New motifs found

Human

– Coding part of genome 2% (70% in yeast), regulatory motifs 3% of intergenic sequences (15% in yeast) – repetitions

Comparative genomics: intro

More than one genome in hand

– no additional information ...CGATGACTATTA... ...CGATGACTA-TA... ...C---GAGTATTA... ...CGATGACTATTA...

Detection of regulatory elements

Make up random motif of form: CGAxxxxxTGG Check validity with the test Results

40 30 20

any nucleotides

Discovered

Known

Summary

Phylogenetic shadowing

Additive divergence

Credits to Bofelli et al. Science, Vol 299, Issue 5611, 13911394 , 28 February 2003

Phylogenetic shadowing

A few closely related species

– Chimp – Baboon – monkeys

Credits to Bofelli et al. Science, Vol 299, Issue 5611, 13911394 , 28 February 2003

Patterns of bullet holes

Bullet holes in planes after a combat Aim: protect vulnerable areas Abraham Wald was asked to analyse patterns of bullet holes

An Example: ORF rejected by the test

Motif recognition

a motif

Gal4 Divergent Convergent ? ? ?

genes

Difference

Genome evolution at large scale

Genome evolution at large scale

quantity of data -> quality of results

We start with…

Input: 4 Saccharomyces

• S. cerevisiae, S. paradoxus, S. mikatae, S. bayanus • 5 to 20 mln years since the divergence of species • Divergent enough to introduce noise where needed • Related enough for orthologues to be easily detectable

Patterns of bullet holes

Phylogenetic footprinting: – Airplane – genome – Bullet hole – mutation – Combat – natural selection

mutations genome sequence functional region!

Understanding genomes

Yeast genome structure

• ~10Mbp • 70% coding, 15% of intergenic region is regulatory

Elements to identify

Genes cDNA de novo / other organisms Results 4800-6400 Regulatory elements Systematic mutations upstream Clustering / common motif search ~60 motifs

Genome alignment

Anchoring with ORFs Aligning region in between

...CGATGACTATTA... ...CGATGACTA-TA... ...C---GAGTATTA... ...CGATGACTATTA...

50kb segment; arrow – direction of ORF, red – 1-1 match; blue – multiple match

Comparative Genomics: Phylogenetic footprinting and shadowing

Sequencing and comparison of yeast species to identify genes and regulatory elements, Manolis Kellis, Nick Patterson, Matthew Endrizzi, Bruce Birren & Eric S. Lander Nature 423, 241 - 254 (15 May 2003)

Regulatory elements identification

Regulatory motifs

– Short 6-15bp – Hard to identify

A small investigation of Gal4 motif shows conservation rates:

Motif: Random Gal4 Intergenic Coding Difference 3% 7% ½x 12.5% 3% 4x Difference 4x

Expected quality:

– High sensitivity of dummy method – High specificity thanks to divergence

Genes identification

Results: gene catalogue revision

– From ~4000 named genes only 15 rejected. One mistake. – 5538 genes (before: 6062) – Different start/stop codons for 5% of genes – ~60 new introns

Genome evolution - nucleotides

S. cerevisiae ...CGTTGACTATTA... Other yeast ...CGATGGCTA-TA...

Nucleotide identity:

S. paradoxus coding intergenic 90% 80% S. mikatae 85% 70% S. bayanus 80% 60%

identity coding intergenic difference 60% 30% 2x

gap 1.3% 14% 10x

frame shift 0.14% 10.2% +stop codons 75x

Genes identification

Solution:

– Dummy method: long region without stop codon becomes putative ORF – We reject putative ORF based on the gene region characteristics

2x faster!

Genome evolution nucleotides

Measures of variation for all species (multiple alignment)

S. cerevisiae ...CGATGCCTATTC... S. paradoxus ...CGATGGCTA-TA... S. mikatae ...C---GAGTATTA... S. bayanus ...CGATTACTATGA...

Look agions

“Because evolution relentlessly tinkers with genome sequence and tests the results by natural selection, such [functional] elements should stand out by virtue of having a greater degree of conservation”