低叶酸、维生素B12营养在阿曼儿童新诊断为自闭症是常见的

自闭症孩子食物的天然补充剂

自闭症孩子食物的天然补充剂1鱼油(每天1000毫克)长链ω-3脂肪酸,特别是鱼油中的EPA/DHA,对大脑功能至关重要,具有高度抗炎作用。

补充ω-3脂肪酸是自闭症谱系障碍儿童最常用的补充和替代疗法之一。

研究结果虽然喜忧参半,但一些研究表明自闭症症状有明显改善。

2消化酶(每餐1~2粒胶囊)由于自闭症儿童往往有消化问题,也可能有肠漏,消化酶可以帮助维生素和矿物质的吸收。

根据加拿大自闭症协会的说法,消化酶可以改善消化和减少炎症,这是非常有益的,因为“消化和吸收障碍会导致儿童营养状况受损,而这反过来又会导致并进一步损害免疫力、排毒和大脑功能。

”3维生素D3(2000~5000IU)与非自闭症儿童相比,自闭症儿童更容易缺乏维生素D。

这是健康大脑功能所需的一种关键维生素。

孕妇缺乏维生素D也会增加其后代患自闭症的风险。

一项研究甚至表明,在冬季受孕而出生的婴儿患自闭症的几率最高(由于日照减少,人体的维生素D水平往往最低),这是— 1 —一项对苏格兰801592名儿童的记录关联研究。

另一项研究,在总共254名自闭症儿童中,14.2%有严重的维生素D缺乏症,43.7%有中度不足,28.3%有轻度不足,只有13.8%的自闭症患者有足够的水平的维生素D。

4益生菌(每天500亿个单位)自闭症儿童通常会出现腹痛、便秘和腹泻等肠胃问题。

由于自闭症可能与消化问题有关,每天服用高质量的益生菌可以帮助保持肠道健康以及肠道中有益菌和有害菌的最佳平衡。

5左旋肉碱(每天250~500毫克)这种氨基酸已经被证明可以改善自闭症的症状。

2013年发表的一项以30名自闭症儿童为研究对象的研究表明,左旋肉碱补充剂可以改善行为症状。

左旋肉碱疗法(100毫克/每天/每公斤体重)持续6个月,“明显改善了自闭症的严重程度,但建议进行后续研究。

”6含叶酸的综合维生素(孕妇每天服用)2018年发表的一项研究得出结论:“与未服用的母亲相比,在怀孕前和怀孕期间服用叶酸及多种维生素补充剂的母亲的下一代患自闭症谱系障碍的风险降低。

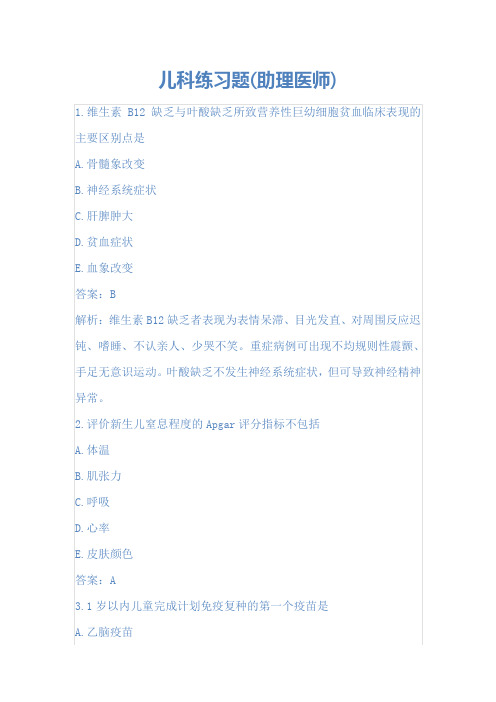

助理医师儿科练习题

A.体温

B.肌张力

C.呼吸

D.心率

E.皮肤颜色

答案:A

3.1岁以内儿童完成计划免疫复种的第一个疫苗是

A.乙脑疫苗

B.百白破疫苗

C.乙肝疫苗

D.麻疹疫苗

E.卡介苗

答案:C

4.符合足月新生儿生理性黄疸特点的是

A.黄疸持续时间>2周

B.黄疸退而复现

C.生后24内出现黄疸

A.完全性大动脉转位

B.房间隔缺损合并肺动脉高压

C.室间隔缺损合并肺动脉高压

D.动脉导管未闭

E.法洛四联症

【答案】E

39.一男婴,营养状况良好,头围46cm,前囟0.5cm,身长75cm,最可能的月龄是()

A.4个月 B.8个月 C.10个月 D.6个月 E.12个月

【答案】E

40.女,3岁。咳嗽5天。发热2天,查体:咽红,双侧扁桃体Ⅰ度肿大,双肺可闻及较固定的中、细湿啰音,最可能的诊断是()

E.低分子右旋糖酐

【答案】A

【解析】该患儿水肿、少尿、血尿、高血压为急性肾小球肾炎的典型表现,目前突出问题是水肿明显,应利尿消肿,故选A。?

44.女孩,会用勺子吃饭,能双脚跳,会翻书,会说23个子的短句 ,最可能的年龄是()

A.2岁 B.4岁 C.4.5岁 D.3.5岁 E.3岁

【答案】A

45.女婴,2个月。拒食、吐奶、嗜睡3天。检体:面色青灰,前囟紧张,脐部少许脓性分泌物。为明确诊断,最关键的检查是()

D.免疫功能测定 E.血培养

答案:E

25.小儿生理性免疫功能低下的时期最主要是

A.学龄期 B.围生期 C.学龄期

D.青春期 E.婴幼儿期

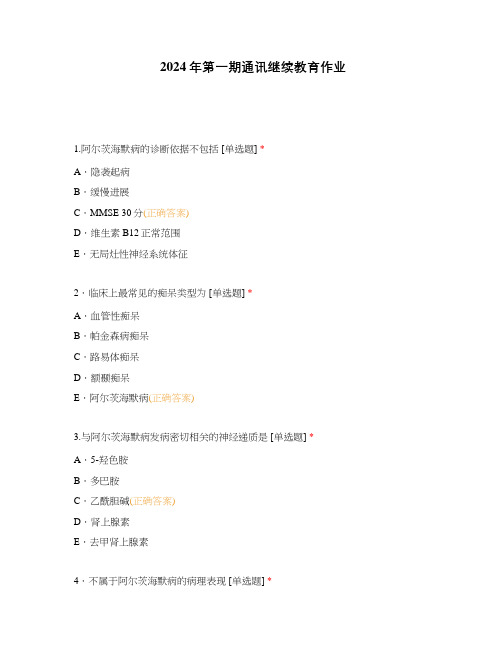

2024年第一期通讯继续教育作业

2024年第一期通讯继续教育作业1.阿尔茨海默病的诊断依据不包括 [单选题] *A.隐袭起病B.缓慢进展C.MMSE 30分(正确答案)D.维生素B12正常范围E.无局灶性神经系统体征2.临床上最常见的痴呆类型为 [单选题] *A.血管性痴呆B.帕金森病痴呆C.路易体痴呆D.额颞痴呆E.阿尔茨海默病(正确答案)3.与阿尔茨海默病发病密切相关的神经递质是 [单选题] *A.5-羟色胺B.多巴胺C.乙酰胆碱(正确答案)D.肾上腺素E.去甲肾上腺素4.不属于阿尔茨海默病的病理表现 [单选题] *A.老年斑B.神经原纤维缠结C.颗粒空泡变性D.Lewy小体(正确答案)E.胆碱能神经元丢失5. 阿尔茨海默病最常见的早期表现为 [单选题] *A. 记忆力减退(正确答案)B. 定向力障碍C. 语言障碍D. 运动障碍E. 精神障碍6. 不属于胆碱酯酶抑制剂的是 [单选题] *A. 多奈哌齐B. 美金刚(正确答案)C. 加兰他敏E重酒石酸卡巴拉汀7.阿尔茨海默病治疗首选药物是() [单选题] *A.改善脑循环和脑代谢的药物B. 胆碱酯酶抑制剂(正确答案)C. 抗胆碱能药物D.兴奋性氨基酸受体拮抗剂E.神经生长因子8. AD常用治疗药物中属于NMDA拮抗剂的是 [单选题] *A. 美金刚(正确答案)B. 多奈哌齐C. 加兰他敏D. 卡巴拉汀E. 多巴胺9.主观认知下降,且客观测试证实认知障碍或精神行为改变,不影响日常生活能力,但对较复杂的日常生活产生可检测到轻度影响。

上述描述属于 [单选题] *A. 临床前期B. 轻度认知障碍(正确答案)C. 轻度痴呆阶段D.中度痴呆阶段10. 可作为阿尔茨海默病体液标记物的是 [单选题] *A. 脑脊液B. 血液C. 尿液D. 唾液E. 以上都可以(正确答案)11.下列不具有减重作用的降糖药是: [单选题] *A.二甲双胍B. α‐糖苷酶抑制剂C.钠‐葡萄糖共转运蛋白2抑制剂(SGLT2i)D.GLP‐1RAE.DPP-4抑制剂(正确答案)12. FDA批准的减重药不包括: [单选题] *A. 芬特明B. 奥利司他(脂肪酶抑制剂)C. 氯卡色林(2C型血清素受体激动剂)D. 二甲双胍(正确答案)E. 利拉鲁肽 3.0 mg(GLP‐1RA)13. 除外下列哪类人群,不宜继续使用SGLT2i [单选题] *A. 泌尿系统感染B. 生殖系统感染C. 急性胃肠炎D. 近期拟行中、大型手术患者E. 中度肝功能不全(正确答案)14. 下列不是代谢手术禁忌症的是: [单选题] *A. 滥用药物、酒精成瘾者B. 1型糖尿病患者C. BMI 27kg/m2(正确答案)D. 胰岛β细胞功能已明显衰竭的T2DM患者15. GLP-1的作用不包括: [单选题] *A. 刺激胰岛素分泌B. 增加胰岛素敏感性(正确答案)C. 抑制胰高糖素分泌D. 抑制胃排空,抑制食欲16. 下列哪项不是代谢性手术: [单选题] *A. 腹腔镜下胃袖状切除术B. 胃大部切除术(正确答案)C. 腹腔镜下 Roux‐en‐Y 胃旁路术D. 胆胰转流十二指肠转位术17. 代谢手术的风险不包括: [单选题] *A. 营养缺乏B. 残胃癌(正确答案)C. 胆石症D. 内疝形成18. 下列说法正确的是: [单选题] *A. BMI≥27 kg/m2,有或无合并症的T2DM,推荐行代谢手术。

孤独症儿童饮食行为与营养问题(精)

中国实用儿科杂志2011年3月第26卷第3期of hepatic veno-occlusive disease in pediatric patients undergo-ing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation attributed to a com-bination of intravenous heparin,oral glutamine,and ursodiol at a single transplant institution [J ].PediatrTransplant,2010,14(5:618-621.[20]Crowther M.Hot topics in parenteral nutrition.A review of theuse of glutamine supplementation in the nutritional support of patients undergoing bone-marrow transplantation and tradition-al cancer therapy [J ].Proc NutrSoc,2009,68(3:269-273.2011-01-10收稿本文编辑:陈婕基金项目:广州市残联孤独症流行病调查项目(穗残联函[2008]185号作者单位:中山大学公共卫生学院妇幼系,广州510080电子信箱:*****************文章编号:1005-2224(201103-0171-03孤独症儿童饮食行为与营养问题静进,刘步云中图分类号:R 72文献标志码:B静进,教授、博士生导师。

现工作于中山大学公共卫生学院妇幼卫生系。

兼任中华预防医学会儿童保健分会副主任、中华预防医学会儿童少年卫生学分会副主任等。

宋庆龄儿科医学奖获得者。

关键词:孤独症;饮食行为;营养素Keywords :autism;eating behaviors ;nutrient1孤独症的饮食行为问题孤独症(autism 的病因至今不很清楚,不同类型和发病程度上很可能存在着不同的起因和不同的问题,一些未知的环境因素对发病可能起着某种诱导或“催化”作用,甚至有研究认为饮食结构和某些营养素可能是孤独症发病的潜在因素之一[1]。

孕妇补叶酸可降低孩子患自闭症的风险

孕妇补叶酸可降低孩子患自闭症的风险

母亲在怀孕开始前4周至怀孕开始后8周服用叶酸补充剂,可以降低孩子患自闭症的风险。

挪威科学家调查了8.5万多名儿童及其母亲孕期服用叶酸的情况。

科学家发现,母亲在孕前至孕初期服用叶酸,其孩子患自闭症的风险比母亲未服用叶酸的孩子减少近40%。

但母亲在孕中期服用叶酸,则不会降低孩子患自闭症的风险。

叶酸属于维生素B类物质,天然存在于绿叶蔬菜内,也可人工合成。

它是细胞正常生长、DNA(脱氧核糖核酸)合成及修复所需的重要营养成分。

自闭症是一种严重的精神发育障碍,症状一般在3岁以前就会表现出来,主要特征是漠视情感、拒绝交流、语言发育迟滞、行为重复刻板、活动和兴趣范围具有显著局限性等。

儿科护理学自考重点

一、儿科免疫的特点:1.IgG可通过胎盘给新生儿,IgG3~5个月后逐渐在体内减少。

2.IgA,IgM不能通过胎盘,新生儿容易患革兰氏阴性菌感染。

3.分泌型IgA在婴儿期缺乏,所以小儿易患呼吸道感染。

一、生长发育1.胎儿期:胚胎期:妊娠-8周,胎儿期:9周-胎儿娩出2.新生儿期:胎儿娩出脐带结扎-28天3.早期新生儿期:脐带结扎-7天4.围生产期:胎儿晚期+妊娠阶段+生后7天,即胎龄满28周-生后7天5.婴儿期:生长发育最迅速,出生后到1周岁6.幼儿期:最易受伤害阶段,1周岁-3周岁7.7.学龄前期:3周岁后到入小学前(6-7岁)8.8.学龄期:从小学起(6-7岁)到进入青春期(12-14周岁)为止。

生殖系统发育接近成人。

智能发育较前更成熟。

9.青春期:女孩11、12-17、18,男孩13、14-18、20,生殖功能基本发育成熟,身高停止增长的时期。

7.小儿生长发育规律:⑴生长发育的连续性和阶段性:出生后头3个月出现第一个生长高峰,至青春期又出现第二个高峰;⑵各系统器官发育的不平衡性:神经系统发育的较早,生殖系统最晚,淋巴系统则先快后回缩;⑶生长发育的顺序性:由上到下,由近到远,由粗到细,由高级到低级,由简单到复杂;⑷生长发育的个体差异。

(5)同一系统发育的不一致性8.影响生长发育两个最基本的因素:遗传因素、环境因素,9.体重:新生儿生后3个月时的体重是出生时体重的2倍,11个月达到出生体重3倍,是第一个生长高峰,2岁时约为出生体重的4倍,新生儿出生时平均体重3KG,半年之内平均每月增加600~800克,下半年平均每月增加300~400克,1岁以内:1-6月的体重=出生体重+月龄*0.77-12月体重=6+月龄*0.252-12岁体重=年龄*2+8(或7)平均每年增加2kg12岁以后为青春期发育,为第二个生长高峰10.身高:新生儿出生约50cm,6个月约65cm,1周岁约75cm,2周岁月85cm 2岁以后平均每年增加5-7.5cm,2-12岁身高=年龄*7+70cm,12岁以后第二生长高峰3岁以下小儿用量板卧位测,上部量与下部量分界线:耻骨联合上缘:12岁时上下部量相等11、头围的正常值:出生32~34cm,6个月40cm,1岁46cm ,2岁48cm12、胸围=头围+岁数1岁时头围=胸围11.前囟:出生约1.5-2cm,1-1.5岁闭合,前囟检查的临床意义:早闭或过小:小头畸形,晚闭或过大:佝偻病、先天甲减,前囟饱满:颅内压增高(见于脑积水患儿)前囟凹陷:脱水或极度消瘦患儿12.后囟出生时已闭合或很小,最迟6-8周闭合,13.颅骨缝约3-4个月闭合14.脊柱:3个月抬头颈椎前凸,6会坐,胸椎后凸,1岁走,腰椎前凸。

孕期危险因素与儿童孤独症相关研究进展_胡恒瑜

孕期危险因素与儿童孤独症相关研究进展胡恒瑜,朱琳,徐琰郑州大学基础医学院,河南郑州450001通讯作者:徐琰,E -mail :xuyan6@关键词:儿童孤独症;孕期;危险因素;预防中国图书分类号:R715.3文献标识码:A文章编号:1001-4411(2016)19-4097-03;doi :10.7620/zgfybj.j.issn.1001-4411.2016.19.81儿童孤独症(childhood autism )又称自闭症,是一种发生在儿童早期的广泛性发育障碍性疾病,其基本特征为不同程度的社会交往障碍﹑言语发育障碍﹑兴趣范围狭窄和刻板重复的行为方式。

孤独症作为一种严重影响儿童健康的神经发育性障碍性疾病,现状不容乐观,已成为全球性的公共健康问题。

因此,很多学者致力于解开孤独症成因之谜,但由于孤独症表现的多样性和病因的复杂性以及纳入研究对象的不一致性,其病因至今不明。

多数研究表明,遗传因素、环境因素、神经生物学因素、免疫因素及孕期危险因素与儿童孤独症的发病相关。

目前,遗传因素在其发病中起主要作用的观点已得到国际学术界的公认,有关孤独症的双生子研究、家系研究、细胞遗传学与分子遗传学研究都为遗传因素在孤独症发病中的作用提供了理论依据。

但是双生子的研究显示,同卵双生子同患孤独症的比率虽然很高,但并非100%。

因此就有环境因素及其他一些因素导致的可能。

也有研究证实[1],自闭症的发生确实与环境及其他一些因素相关。

孕产期危险因素及围生期并发症被多次报道,但各研究结果不尽相同,且多为小样本观察性研究。

本文就国内外近年来有关孕期危险因素与孤独症的相关研究做出如下综述,从而为孤独症的预防和干预提供理论依据。

1母孕期危险因素孤独症的诊断通常是在两岁以前,敏感的窗口期可能是在孕前三个月、孕期或产后的早期发展阶段。

研究表明[2]孕产期的危险因素及围生期的并发症能增加孤独症的患病风险。

1.1母孕期宫内环境与孤独症的发病相关宫内环境对胎儿的大脑发育起着至关重要的作用,内部环境的改变很容易使胎儿出现一定程度的脑损伤,也更容易引起基因的突变,从而导致孤独症的发生。

特殊人群营养习题及答案

特殊人群营养习题及答案1.妊娠期营养不良对胎体的影响有(A)低出生体重、(B)早产、(C)畸形等。

2.婴幼儿的常见营养缺乏症主要是(A)贫血、(B)佝偻病两种。

3.妊娠期营养不良对母体的影响有(A)贫血、(B)妊娠高血压综合征、(C)产后出血等。

4.老年人体内蛋白质的合成能力差,同时对蛋白质的吸收利用率下降,容易出现(A)负氮平衡。

5.母乳喂养时间至少应持续(B)6个月。

6.孕妇常见的营养缺乏症有(A)贫血和(B)缺碘。

7.成人能量消耗除用于食物特殊动力作用外、还用于(A)基础代谢和(B)体力活动。

8.初乳富含大量的钠、氯和免疫蛋白,尤其是(C)免疫球蛋白A和乳铁蛋白等,但乳糖和脂肪含量较成熟乳(D)降低,故易消化。

9.婴幼儿辅食添加的时间应在(B)2个月~3个月龄开始。

10.孕妇一般可根据定期测量体重的增长正常与否来判断(D)营养摄入是否适宜。

二、单选题1.下列哪种营养素不易通过乳腺输送到乳汁中,母乳中的含量很低。

D)维生素C2.胎儿出生时体内储备的铁,一般可满足(C)4个月内婴儿对铁的需要量。

3.婴幼儿佝偻病主要是由(C)维生素D缺乏引起的。

4.母亲妊娠期间严重缺碘,对胎儿发育影响最大的是(B)骨骼系统。

5.小于6月龄的婴儿宜选用蛋白质含量(A)<12%的配方奶粉。

6.孕妇出现巨幼红细胞贫血,主要是由于缺乏(C)维生素B12.7.母乳喂养的婴幼儿添加辅食,从(C)4个月~6个月开始最好。

8.儿童生长发育迟缓、食欲减退或有异食癖,最可能缺乏(D)锌。

9.老年人保证充足的维生素E供给量是为了(C)增强机体的抗氧化功能。

10.与老年人容易发生的腰背酸痛有较密切关系的营养素是(B)钙。

11.超氧化物歧化酶(SOD)的主要组成成分是(A)铜。

12.血液中下列哪种元素含量降低的孕妇比较容易被致病菌感染(A)铁。

三、多选题1.妊娠期营养不良对胎体的影响有(A)低出生体重、(B)早产、(C)畸形等。

2.婴幼儿的常见营养缺乏症主要是(A)贫血、(B)佝偻病两种。

营养与儿童自闭症的关系

营养与儿童自闭症的关系儿童自闭症是一种神经发育障碍,主要表现为社交互动和沟通能力的缺陷,以及刻板、重复性行为的特征。

虽然自闭症的确切原因尚不明确,但研究表明,营养在儿童自闭症的发展和管理中起着重要的作用。

本文将探讨营养与儿童自闭症之间的关系,并提供一些营养方面的建议。

1. 营养与大脑发育儿童期是大脑迅速发育的关键时期,适当的营养摄入对于大脑的正常发育至关重要。

研究发现,一些特定的营养素,如维生素D、维生素B6、叶酸、镁和锌等,与儿童自闭症的风险相关。

这些营养素在神经递质合成、脑细胞功能和神经元连接等方面发挥着重要作用。

因此,适当的营养摄入可以为儿童自闭症的发展提供有利条件。

2. 高质量蛋白质的重要性蛋白质是儿童发育所需的重要营养素之一。

高质量蛋白质的摄入有助于大脑神经元的发育和功能。

研究发现,儿童自闭症患者的蛋白质摄入量普遍较低,这可能与其对特定食物的选择偏好、食物纹理敏感性以及食物选择的刻板行为有关。

因此,家长可以通过提供多样化的蛋白质来源,如鱼类、家禽、豆类和坚果等,来增加儿童自闭症患者的蛋白质摄入。

3. 益生菌与肠道健康近年来,肠道菌群与儿童自闭症之间的关系引起了研究人员的广泛关注。

肠道菌群的失衡可能导致肠道屏障功能受损,进而影响大脑发育和功能。

一些研究表明,通过补充益生菌,可以改善儿童自闭症患者的肠道菌群,缓解相关的行为和认知症状。

因此,适当的益生菌摄入可能对儿童自闭症的管理具有积极的影响。

4. 针对特殊饮食的研究一些家长和专业人士主张采用特殊饮食,如无麸质饮食或特定营养素补充,来改善儿童自闭症的症状。

然而,目前对于这些特殊饮食的疗效仍存在争议,且缺乏充分的科学证据支持。

因此,家长在考虑采用特殊饮食时应咨询专业人士的建议,并进行科学监测和评估。

5. 营养与综合治疗营养在儿童自闭症的综合治疗中扮演着重要角色,但并非是唯一的因素。

综合治疗通常包括行为疗法、语言疗法、教育干预等多个方面的综合干预。

幼儿卫生学复习题

XI幼儿卫生学复习题一.单项选择题1.下列不属于幼儿卫生学研究范畴的是()A.生理解剖特点B.生长发育规律 C营养 D疾病治疗2.应让幼儿有足够的时间接受阳光照射,以预防()A.佝偻病B.脚气病C.坏血病D.夜盲症3.造成婴幼儿“牵拉肘”的生理原因是()A.肘关节较松 B大肌肉发育早 C骨头嫩 D.骨骼在生长4.气体交换的场所是()A.咽 B气管 C支气管 D肺5.呼吸道最狭窄的部位是()A.咽B.喉C.气管D.支气管6.下列不属于婴幼儿呼吸系统的特点的是()A.呼吸频率快B.肺活量小 C声带不够坚韧 D.咽鼓管短宽7.婴幼儿的乳牙一般在几岁出齐()A.2岁半B.6—7个月C.一岁D.一岁半8.“六龄齿”又称“第一恒磨牙”共几颗()A.2B.4C.6D.89.防止胃内东西倒流入口腔的结构是()A.幽门B.贲门C.食管 D喉10.婴儿多大时可以给点“手拿食”()A.3-5个月B.5-6个月C.6-9个月D.9-12个月11.儿童脑细胞的耗氧量约为全身耗氧量的()A.20%B.30%C.40%D.50%12.中大班幼儿每次看电视时间一般不超过()A.15分钟B.30分钟C.60分钟D.120分钟13.下列属于婴幼儿皮肤特点的是()A.保护功能差B.调解体温的功能强C.渗透功能强D.不易受伤14.下列说法正确的是()A.新生儿要剃头发B.幼儿要用化妆品保护C.儿童勤剪指甲D.儿童带金属饰物15.影响婴幼儿心理健康的社会因素是()A.家庭B.情绪C.动机D.自我意识16.预防克汀病最有益的食物是()A.胡萝卜B.西红柿C.海带D.乳类食品17.患儿皮肤上初为红色丘疹,渐为水疱,水疱干缩结痂,该传染病可能是()A.麻疹B.水痘C.风疹D.幼儿急诊18.预防呼吸道传染病,简便有效的措施是()A.用具消毒B.保持空气流通C.保护水源D.管理粪便19.无论采取何种降温措施,一般先把高热病儿的体温降至()A.36o C左右B.37 o C左右C.38 o C左右D.39 o C左右20.年龄在1岁内的孩子,最好的食物和饮料是()A.鲜牛奶B.鲜羊奶C.鲜果汁D.母乳21.生长激素大量分泌是在幼儿()A.熟睡时B.活动时C.饭饱后D.清醒时22.幼儿园适龄儿童的年龄段是()A.0-1周岁B.1-3周岁C.3-6周岁 C.6-9周岁23.因睡眠时间不足,质量不高,而分泌减少,影响身高的激素是()A.甲状腺激素B.生长激素C.肾上腺素D.胰岛素24.为保护幼儿的眼睛,中大班幼儿看电视时间不超过()A.30分钟B.45分钟C.60分钟D.120分钟25.蚊虫是某些传染病的媒介,主要由蚊子传播的是()A.甲肝B.乙肝C.急性结膜炎D.乙型脑炎26只喜欢吃肉,不喜欢吃蔬菜水果的幼儿,时间长了易患()A.夜盲症B.佝偻病C.脚气病D.坏血病27.搞好环境、饮食等卫生,做好经常性的消毒工作,属于()A.控制传染源B.切断传播途径C.保护易感者D.隔离病人28.病初类似感冒,发病后几小时,皮肤上出现出血性皮疹,疑似感染了()A.流行性脑脊髓膜炎B.传染性肝炎C.猩红热D.麻疹29.在小儿几个月时,就可开始训练自觉地控制排尿()A.5-7个月B.6-8个月C.8-10个月D.10-18个月30.血液循环的动力器官是()A.心脏B.动脉C.静脉D.毛细血管31.由于缺乏维生素B12和叶酸,影响红细胞成熟所致的疾病是()A.缺铁性贫血B.夜盲性贫血C.坏血病D.营养性巨幼红细胞性贫血32.下列有关蛋白质生理功能的描述,正确的是()A.免疫功能B.固定润滑脏器C.减少体热散失D.解毒作用33.3-6岁的幼儿,可每日安排三餐及午后几次点心()A.一次B.二次C.三次D.四次34幼儿每餐的热量分配为()A. 25%-30% 35%-40% 10%左右 25%-30%B.20%-30% 40%-45% 10%左右 25%-30%C. 35%-40% 25%-30% 10%左右 25%-30%D.30% 40% 10%左右 30%35.下列不属于植物性食物中毒的是()A.发芽马铃薯中毒B.扁豆中毒C.豆浆中毒D.沙门氏菌食物中毒36.“呆小症”是由于缺乏那种无机盐引起的()A. 碘B. 钙C. 铁D. 锌37.关于添加辅食的原则,下列说法正确的是()A. 品种不能随时更改B. 量基本不变C. 先加固体食物D.不加流食38.治疗弱视的最佳年龄阶段是()A. 学龄前期B. 小学1-2年级C. 小学3-5年级D. 初中39.一氧化碳中毒后,应采取的正确措施是()A. 灌酸菜汤B. 灌醋C. 给患者保暖D. 抬离中毒现场40.转换工作性质,使大脑皮质工作区和休息区不断轮换,这体现了大脑皮质活动的哪种特性()A. 动力定型B. 镶嵌式活动原则C. 优势原则D. 抑制活动原则41.小儿比成人多下列哪种必需氨基酸()A. 组氨酸B. 苏氨酸C. 亮氨酸D.蛋氨酸42.幼儿淋巴系统发育迅速,而生殖系统在童年期几乎没有发展。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Applied nutritional investigationLow folate and vitamin B12nourishment is common in Omani children with newly diagnosed autismYahya M.Al-Farsi M.D.,D.Sc.a ,Mostafa I.Waly M.P.H.,Ph.D.b ,g ,Richard C.Deth Ph.D.c ,Marwan M.Al-Sharbati Ph.D.d ,Mohamed Al-Shafaee M.D.a ,Omar Al-Farsi M.Sc.a ,Maha M.Al-Khaduri M.D.e ,Ishita Gupta M.Sc.f ,Amanat Ali Ph.D.b ,Maha Al-Khalili M.Sc.a ,Samir Al-Adawi Ph.D.d ,Nathaniel W.Hodgson Ph.D.c ,Allal Ouhtit M.Ph.,Ph.D.f ,*aDepartment of Family Medicine and Public Health,College of Medicine and Health Sciences,Sultan Qaboos University,Muscat,Sultanate of Oman bDepartment of Food Science and Nutrition,College of Agriculture and Marine Sciences,Sultan Qaboos University,Muscat,Sultanate of Oman cDepartment of Pharmaceutical Sciences,Northeastern University,Boston,Massachusetts,USA dDepartment of Behavioral Medicine,College of Medicine and Health Sciences,Sultan Qaboos University,Muscat,Sultanate of Oman eDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology,College of Medicine and Health Sciences,Sultan Qaboos University,Muscat,Sultanate of Oman fDepartment of Genetics,College of Medicine and Health Sciences,Sultan Qaboos University,Muscat,Sultanate of Oman gDepartment of Nutrition,High Institute of Public Health,Alexandria University,Alexandria,Egypta r t i c l e i n f oArticle history:Received 24March 2012Accepted 5September 2012Keywords:Autism FolateMethylation Nutrition OmanVitamin B12a b s t r a c tObjective:Arab populations lack data related to nutritional assessment in children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs),especially micronutrient de ficiencies such as folate and vitamin B12.Methods:To assess the dietary and serum folate and vitamin B12statuses,a hospital-based case –control study was conducted in 80Omani children (40children with ASDs versus 40controls).Results:The ASD cases showed signi ficantly lower levels of folate,vitamin B12,and related parameters in dietary intake and serum levels.Conclusion:These data showed that Omani children with ASDs exhibit signi ficant de ficiencies in folate and vitamin B12and call for increasing efforts to ensure suf ficient intakes of essential nutrients by children with ASDs to minimize or reverse any ongoing impact of nutrient de ficiencies.Ó2013Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved.IntroductionA survey of the available literature suggests that nutritional and dietary interventions are considered routine treatment for developmental disorders including autism [1,2].However,the study and implementation of such measures have been limited to the industrialized and af fluent countries of North America and Western Europe,with few exceptions [3,4].Developing coun-tries,and especially Arab countries,lack relevant data because autism is not a common theme of research [5].Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs)are neurodevelopmental disorders commonly characterized by debilitating and intran-sigent symptoms in three categories:dif ficulties with reciprocalsocial interactions,impaired communication skills,and disturbed emotional functioning that often manifests as stereo-typical and non-goal –directed behaviors [6].Oman,an Arab country located on the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula adjacent to the Asian and African continents with a population nearing 3.5million,presents fertile ground to explore the nutritional and dietary de ficits in children with developmental disorders [7].In Oman,a preliminary epidemio-logic survey has suggested that 0.14per 1000Omani children (0–14y old)have ASDs [8].Issues of child welfare are generally a signi ficant concern for domestic social policy.Oman,like other emerging economies,is witnessing the co-occurrence of undernutrition and obesity in its population [9].Evidence also suggests that the country has yet to overcome persistent malnutrition.Alasfoor et al.[10]reported that,nationwide,approximately 7%of children exhibit wasting,11%exhibit stunting,and 18%were classi fied as underweight.A more recent study replicating that study has suggested that these indices of malnutrition may be even higher [11].However,these studies limited their sample selection to preschool childrenThis study was supported by the Internal Grant Fund (IG/AGR/Food/10/01)and His Majesty ’s Strategic Fund (SR/MED/FMCO/11/01),College of Medicine and Health Sciences,Sultan Qaboos University.A research grant from the Autism Research Institute provided partial support for this study.*Corresponding author.Tel.:þ96-8-2414-3464;fax:þ96-8-2441-3300.E-mail address:aouhtit@.om (A.Ouhtit).0899-9007/$-see front matter Ó2013Elsevier Inc.All rights reserved./10.1016/j.nut.2012.09.014Contents lists available at ScienceDirectNutritionjo urnal homepag e:www.nutritNutrition 29(2013)537–541in mainstream education.Thus,children with ASDs were unlikely to be accounted for by these assessments of malnutri-tion indices because such children are unlikely to be enrolled in mainstream schools in Oman[12].To address the potential data gap regarding children with developmental disorders,Al-Farsi et al.[13]examined the nutritional status of128children with ASDs in Oman and found that approximately9%of the partici-pants were malnourished according to the indices of under-weight,wasting,and stunting.There is evidence that the variation in levels of two important nutrients,folate and vitamin B12[14–16],is strongly relevant for ASD.These two nutrients have been suggested to play a vital role in cognitive functions [17]similar to those often found to be disturbed in children with ASDs[14,18–20].Building on these emerging data showing that Arab pop-ulations tend to have folate and vitamin B12deficiencies,we initially conducted a preliminary study on screening the folate and vitamin B12status and we reported that a low status of these two vitamins was associated with hyperhomocysteinemia in Omani autistic children[21].In the present study,we performed a more comprehensive investigation and compared dietary and serum folate and vitamin B12statuses between children with ASDs and control subjects matched for age,gender,ethnicity,and sociodemographic status.Materials and methodsThe present case–control study was designed to determine the differential variation in folate or vitamin B12levels in preschool-age Omani children(3–5y old)with and without diagnosed ASDs.The study was conducted from December 2009to August2010at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital(SQUH),the main referral hospital for all autism cases in Oman.ParticipantsThe study participants included80Omani children(40ASD cases and40 control subjects of overall similar age and gender).The study was approved by the medical research ethics committee of Sultan Qaboos University.All caregivers of the participants provided their informed consent to be included in the study.Ascertainment of an ASD diagnosis was made according to the Childhood Autism Rating Scale[22],which was developed using gold-standard criteria based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,Fourth Edition, Text Revision[23].Accordingly,all participants fulfilled the eligibility for a diag-nosis of an ASD,exhibiting symptoms within the triad of typical autistic traits: communication impairment,social deficits,and ritualistic interests.Control subjects were randomly selected from eligible outpatients at the Department of Child Health at SQUH.Eligible subjects included children3to5y old who were not known to have any overt neurodevelopmental or behavioral disturbances and were not previously or currently considered malnourished.Eligible diag-noses included trauma,routine physical examination,dental problems,and dermatologic problems.Study protocolEach participant’s mother was interviewed one on one.The interview questions were designed to elicit information regarding the child’s develop-mental milestones,sociodemographic background,and dietary history including vitamin supplementation,in addition to other risk factors that might indicate a predisposition to autism,including pregnancy complications,preterm delivery, breast-feeding,and a family history of autism.To overcome the problem of reverse causality d that autistic children might have changed their dietary habits after diagnosis d only recently diagnosed cases were included,for which the dietary intake questionnaire was administered within10to14d of confirming the diagnosis.The retrospective dietary intake of folate and vitamin B12was ascertained using the Reduced Dietary Questionnaire of Block et al.[24],which is a semiquantitative tool to gauge food intake frequency.The psychometric properties of the Reduced Dietary Questionnaire were found to be adequate for the present cohort.Ina food diary,the participants’mothers were asked to report the food items the child had consumed during the year preceding the study and whether they had changed their diet from their usual routine during the previous6mo.Subsequently,all food diaries were analyzed using standard computer-assisted procedures(ESHA Research,Salem,OR,USA).Laboratory measurementsBlood samples were collected from each of the40cases and40controls matched for age,sex,and weight(withinÆ0.5kg)to estimate the levels of serum folate and vitamin B12.For blood sampling,10mL of venous blood was collected from the median cubital vein.Blood samples were drawn into a plain tube by venipuncture.After centrifugation,the serum was transferred to a micro-centrifuge tube and stored atÀ80 C before the folate and vitamin B12 measurements.We used the AxSYM Instrument(Abbott Diagnostics,Worcester,Massachu-setts)for the quantitative determination of serum levels of folate and vitamin B12.The cutoff values were3to20ng/mL for folate and250to1250pg/mL for vitamin B12.Hypersegmented neutrophils on the peripheral blood smear were defined approximately as more than5%of neutrophils with at leastfive lobes or more than1%of neutrophils with at least six lobes.Serum levels of homocysteine and methionine were measured using high-performance liquid chromatography and electrochemical detection.Serum samples were blown with nitrogen and10m L was injected into an ESA CoulArray high-performance liquid chromatographic system with a BDD analytical cell electrochemical detector system(model5040)equipped with an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C8(3Â150mm,3.5m m)reverse-phase C8column.A dual mobile phase gradient elution was used,consisting of a mobile phase containing sodium phosphate25mmol/L and1-octanesulfonic acid1.4mmol/L,adjusted to pH2.65 with phosphoric acid,with the second mobile phase containing50%acetonitrile. The system was run at aflow rate of0.6mL/min at ambient temperature with the following gradients:0to9min0%B,9to19min50%B,and19to30min50%B. Peak area analysis was provided by CoulArray3.06software(ESA,Chelmsford, Massachusetts)based on the standard curves generated for each compound. Statistical analysesChi-square analyses were used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences among portions of the categorical data.The non-parametric Fisher exact test(two-tailed)was used instead of the chi-square test for small samples where the expected frequency was less than5in any of the2Â2table cells. Unpaired Student’s t test was used to ascertain any significant differences between the mean values of two continuous variables,and the Mann–Whitney test was used for non-parametric tests.The odds ratios(ORs)for ASDs were computed for the bottom and middle thirds compared with the top third of folate and vitamin B12concentrations based on the distributions in the control group. The ORs and95%confidence intervals(CIs)obtained from logistic regression modeling were taken as measurements of association between ASD and levels of folate and vitamin B12.All statistical analyses were performed using SAS9.1(SAS Institute,Cary,NC,USA);a cutoff P value<0.05was the threshold of statistical significance for all tests.ResultsEighty children,including40cases and40controls,were analyzed.The age was identical in cases and controls.Selected sociodemographic characteristics of all subjects at the time of enrollment in the study are listed in Table1.In the two groups, most participant families lived in urban areas.The groups were also comparable in the distribution of maternal age,mother’s occupation,and family pared with the control group,mothers of participants in the case group tended to have higher illiteracy rates and folic acid supplementation during pregnancy and a higher consumption of fortifiedflour and bread; however,these differences were not statistically significant (P>0.05).Our results showed that children with ASD had consistently lower levels of folate and vitamin B12in their diet and in their serum(Table2).The level of homocysteine was significantly increased in ASD cases by68%(P¼0.004),whereas the level of methionine was significantly decreased by15%(P¼0.05; Table2).Because homocysteine is the substrate for the folate-and vitamin B12-dependent enzyme methionine synthase and methionine is the product,these results are indicative of a func-tional deficit in methionine synthase activity in children withY.M.Al-Farsi et al./Nutrition29(2013)537–541 538ASD in Oman,consistent with lower serum levels of its vitamin cofactors.Table 3lists the ORs and 95%CIs for ASD by tertile of folate and vitamin B12levels after adjusting for age,gender,and other socioeconomic variables.The OR for being in the ASD group among subjects with folate levels in the lowest tertile compared with those in the highest tertile was 1.7(95%CI 0.3–5.2).The OR for being in the ASD group among subjects with vitamin B12levels in the lowest tertile compared with those in the highest tertiles was 1.6(95%CI 0.8–8.3).A statistically signi ficant trend toward membership in the ASD group was found in participants in the lowest tertiles for folate and vitamin B12(P <0.01,P ¼0.04,respectively).DiscussionThe present study shows that there is a differential variation in two nutrients,folate and vitamin B12,in Omani children with ASD compared to those de fined as control subjects.A signi ficant decrease was found in the mean values of dietary and serum levels of folate and vitamin B12between children with and those without ASD.A decrease in the activity of methionine synthase,for which folate and vitamin B12are required cofactors,was observed,indicating that their dietary and serum de ficits have functional consequences.On the whole,the present data suggest pervasive and persistent de ficiencies of folate and vitamin B12in the studied children with ASD.Even in the general population,the prevalence of folate and vitamin B12de ficiencies in Oman is unknown.However,several reports have indicated that folate and vitamin B12de ficiencies may be common in Arab populations generally [25].A study that compared an Arab population with its Western Europe coun-terpart showed that the dietary intake of folate in Arab men and women was below the recommended nutrient intakes [26].Another study from Israel showed de ficiencies in folate and vitamin B12in Arab patients with Alzheimer ’s disease [27].Our previous study showed that folate de ficiency was associated with adult type 2diabetes in Oman [28].Folate de ficiency has been implicated in the manifestation of various clinical disorders [28].Folate de ficiency is characterized by hypersegmentation of neutrophils,megaloblastosis,and anemia.Megaloblastic anemia can be masked by concurrent iron-de ficiency anemia or thalassemia.Folate de ficiency has been shown to arrest children ’s development,even in the absence of anemia [29].Serum folate concentration,although typically low in patients with folate-de ficient megaloblastic anemia,is primarily a re flection of a short-term folate balance.The World Health Organization has recommended empiric treatment for severely malnourished children with folate de fi-ciency [30].In Oman,prompt treatment of folate de ficiency should be routinely prioritized for children with ASDs.Children with autism or a pervasive developmental disorder-not other-wise speci fied exhibit selective eating habits and very often exhibit feeding dif ficulties [31,32].Children with autism also exhibit greater dif ficulties with feeding and at meal times compared with non-autistic children [33,34].Parents of autistic children find it dif ficult to feed their children,probably because of pica,a disorder in which children tend to be picky eaters,prefer to eat non-edible objects,and resist consuming solid food [34].Although the underlying mechanisms are not very well understood,some autistic children tend to have motor delays resulting in dif ficulties while eating and swallowing,whereas some have gastrointestinal problems (constipation or diarrhea)resulting in an aversion to food [35].De ficiencies in various nutrients have been reported to be associated with autism,including but not limited to vitamin D [36],calcium and vitamin E [37],and vitamins B6,B9,and B12.One possible explanation for the relation between folate and/or vitamin B12de ficiencies and ASD involves DNA hypomethylation [38].Vitamin B12de ficiency has been shown to occur in vegetarians and children who are breast-fed by vegetarian mothers [39,40].Table 1Values are presented as number (percentage)or mean ÆSD.Table 2Comparison of dietary and serum folate and vitamin B12levels and their relatedTable 3Odds ratios and 95%con fidence intervals for autism spectrum disorder by CI,con fidence interval;OR,odds ratio*Tertiles based on the distribution of the controls.Y.M.Al-Farsi et al./Nutrition 29(2013)537–541539An existing vitamin B12deficiency is known to inhibit the release of vitamin B12found in subsequently consumed food,which may be another factor contributing to the predicament of children with ASDs[41].Vitamin B12deficiency has been shown to precipitate megaloblastic anemia,atrophic glossitis,neuropathy,and demy-elination of the central nervous system[42].The fact that vitamin B12deficiency has been linked to several neurologic disorders is further evidence of its vital importance[43].The question remains as to whether such adverse effects of vitamin deficiency may also be observed in children with ASDs.The present study implies that increased intakes of several vitamins and essential nutrients should be promoted.Feeding difficulties in autism can be allevi-ated through the supplementation of essential nutrients such as vitamins B6and B12,which has been recommended by some studies[44].In addition,anecdotal and clinical evidence supports a more active role by health care professionals in the case of nutritional deficiencies in autistic children because problems are sometimes overlooked owing to picky eating being a common problem in neurotypical and autistic children around the age when autism is usually diagnosed(reviewed by Rempel et al.[45]).In general,Oman has been highly proactive with such initiatives.National supplementation programs targeting micronutrient deficiencies were started two decades ago.In 1990,a supplementation program began providing all pregnant women with a daily dose of folic acid5mg and iron200mg throughout the course of their pregnancies[46].In1997,another national program was initiated to fortify relevant food consumed in the country with folic acid5mg/kg and iron30ppm[47].Both programs have been reasonably successful.In1993,it was found that97%of all pregnant women attending health centers had received the supplements,although their compliance rate with the supplementation recommendations had reached77%[48].In 2004,a national survey showed that the initiative for folate fortification inflour and bread had achieved81%coverage of all households in Oman,with an averageflour consumption of116 g/person per day[46].The question remains as to whether such a proactive initiative has reversed known folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies in Omani children with autism.From the present data,compared with the control group,children with autism showed significantly decreased levels of folate and vitamin B12 in their dietary intake and serum.Therefore,concerted effort needs to be directed toward such a vulnerable population.Several limitations of this study must be acknowledged.First, the participants were drawn from a clinical population,namely those seeking consultation at an urban tertiary care unit.It is well known that those seeking care at a hospital are not necessarily a suitable proxy for the community at large.Therefore, community studies with a broader sampling would be prereq-uisite to generalizing the presentfindings.Second,although most of the measurements used were objective,psychosocial histories and demographic information were narrated by the participants’caregivers.It is not clear whether any unidentified confounders exist owing to any possible bias of this approach. Third,the present study was restricted to children of preschool age with ASD;therefore,the present results should be inter-preted within the confines of this age group.Fourth,although the present study indicates a greater folate and vitamin B12defi-ciency in children with ASD compared with control subjects,the observed association is not temporal and therefore does not establish a causal link.It remains unclear whether the observed deficiencies are a consequence of pathologic processes central to developmental disorders or a compensatory adaptation.The condition of the ASD cases may have rendered them incapable of following dietary guidelines with respect to the nutrients investigated,or under-consumption may have been secondary to the primary pathologic processes inherent in developmental disorders such as ASD.In summary,the present study showed that Omani children with ASDs exhibit significant deficiencies in folate and vitamin B12compared with their non-ASD counterparts,defining a nutritional basis for this pervasive developmental disorder in Oman.Ourfindings underscore the importance of mobilizing available health and educational resources to ensure the suffi-cient intake of relevant trace elements and other essential nutrients by children with ASDs and to minimize or reverse any ongoing impact of nutrient deficiencies.Further studies of this type should be encouraged to translate the presentfindings into appropriate policy recommendations.References[1]Mart ıLF.Effectiveness of nutritional interventions on the functioning ofchildren with ADHD and/or ASD.An updated review of research evidence.Bol Asoc Med P R2010;102:31–42.[2]Johnson M,Ostlund S,Fransson G,KadesjöB,Gillberg C.Omega-3/omega-6fatty acids for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder:a randomized placebo-controlled trial in children and adolescents.J Atten Disord 2009;12:394–401.[3]Tang B,Piazza CC,Dolezal D,Stein MT.Severe feeding disorder andmalnutrition in2children with autism.J Dev Behav Pediatr2011;32:264–7.[4]Xia W,Zhou Y,Sun C,Wang J,Wu L.A preliminary study on nutritionalstatus and intake in Chinese children with autism.Eur J Pediatr 2010;169:1201–6.[5]AfifiMM.Mental health publications from the Arab world cited in PubMed,1987–2002.East Mediterr Health J2005;1:319–28.[6]Greenspan SI,Brazelton TB,Cordero J,Solomon R,Bauman ML,Robinson R,et al.Guidelines for early identification,screening,and clinical manage-ment of children with autism spectrum disorders.Pediatrics 2008;121:828–30.[7]Central Intelligence Agency.The world factbook:Oman.Available at:https:///library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mu.html.Accessed August1,2011.[8]Al-Farsi YM,Al-Sharbati MM,Al-Farsi OA,Al-Shafaee MS,Brooks DR,Waly MI.Brief report:prevalence of autistic spectrum disorders in the Sultanate of Oman.J Autism Dev Disord2011;41:821–5.[9]Musaiger AO.Overweight and obesity in the eastern Mediterranean region:can we control it?East Mediterr Health J2004;10:789–93.[10]Alasfoor D,Elsayed MK,Al-Qasmi AM,Malankar P,Sheth M,Prakash N.Protein–energy malnutrition among preschool children in Oman:results ofa national survey.East Mediterr Health J2007;13:1022–30.[11]Alasfoor D,Mohammed AJ.Implications of the use of the new WHO growthcharts on the interpretation of malnutrition and obesity in infants and young children in Oman.East Mediterr Health J2009;15:890–8.[12]Profanter A.Facing the challenges of children and youth with specialabilities and needs on the fringes of Omani society.Child Youth Serv Rev 2009;31:8–15.[13]Al-Farsi YM,Al-Sharbati MM,Waly MI,Al-Farsi OA,Al Shafaee MA,Deth RC.Malnutrition among preschool-aged autistic children in Oman.Res Autism Spectrum Disord2011;5:1549–52.[14]Schmidt RJ,Hansen RL,Hartiala J,Allayee H,Schmidt LC,Tancredi DJ,et al.Prenatal vitamins,one-carbon metabolism gene variants,and risk for autism.Epidemiology2011;22:476–85.[15]James SJ,Melnyk S,Fuchs G,Reid T,Jernigan S,Pavliv O,et al.Efficacy ofmethylcobalamin and folinic acid treatment on glutathione redox status in children with autism.Isr J Clin Nutr2009;89:425–30.[16]Moretti P,Sahoo T,Hyland K,Bottiglieri T,Peters S,del Gaudio D,et al.Cerebral folate deficiency with developmental delay,autism,and response to folinic acid.Neurology2005;64:1088–90.[17]Fafouti M,Paparrigopoulos T,Liappas J,Mantouvalos V,Typaldou R,Christodoulou G.Mood disorder with mixed features due to vitamin B(12) and folate deficiency.Gen Hosp Psychiatry2002;24:106–9.[18]Adams JB,Audhya T,McDonough-Means S,Rubin RA,Quig D,Geis E,et al.Nutritional and metabolic status of children with autism vs.neurotypical children,and the association with autism severity.Nutr Metab2011;8:34.[19]Lowe TL,Cohen DJ,Miller S,Young JG.Folic acid and B12in autism andneuropsychiatric disturbances of childhood.J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry1981;20:104–11.[20]Coelho D,Suormala T,Stucki M,Lerner-Ellis JP,Rosenblatt DS,Newbold RF,et al.Gene identification for the cblD defect of vitamin B12metabolism.N Engl J Med2008;358:1454–64.Y.M.Al-Farsi et al./Nutrition29(2013)537–541 540[21]Ali A,Waly MI,Al-Farsi YM,Al-Sharbati MM,Essa MM,Deth RC.Hyper-homocysteinemia among Omani autistic children:a case control study.Acta Biochim Pol2011;58:547–51.[22]Schopler E,Reichler RJ,DeVellis RF,Daly K.Toward objective classificationof childhood autism:Childhood Autism Rating Scale(CARS).J Autism Dev Disord1980;10:91–103.[23]Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders.4th ed,text rev.Washington,DC:American Psychiatric Association;2000.[24]Block G,Hartman AM,Naughton D.A reduced dietary questionnaire:development and validation.Epidemiology1990;1:58–64.[25]Moussa NA,Awad MO,Yahya TM.Pernicious anaemia and neurophysio-logical studies in Arabs.Int J Clin Pract2000;54:152–4.[26]Herrmann W,Obeid R,Jouma M.Hyperhomocysteinemia and vitamin B-12deficiency are more striking in Syrians than in Germans d causes and implications.Atherosclerosis2003;166:143–50.[27]Hirsch S,de la Maza P,Barrera G,Gatt a s V,Petermann M,Bunout D.TheChileanflour folic acid fortification program reduces serum homocysteine levels and masks vitamin B-12deficiency in elderly people.J Nutr 2002;132:289–91.[28]Al-Maskari MY,Waly MI,Ali A,Al-Shuaibi YS,Ouhtit A.Folate and vitaminB12deficiency and hyperhomocysteinemia promote oxidative stress in adult type2diabetes.Nutrition2012;28:e23–6.[29]Shakur YA,Choudhury N,Hyder SM,Zlotkin SH.Unexpectedly high earlyprevalence of anaemia in6-month-old breast-fed infants in rural Bangladesh.Publ Health Nutr2010;13:4–11.[30]World Health Organization.Preparation and use of food based dietaryguidelines.WHO technical series880.Geneva:World Health Organization;1998.[31]Ahearn WH,Castine T,Nault K,Green G.An assessment of food acceptancein children with autism or pervasive developmental disorder-not other-wise specified.J Autism Dev Disord2001;31:505–11.[32]Palmer S,Ekvall S.Pediatric nutrition in developmental disorders.Springfield,IL:CC Thomas’;1978.[33]Schreck KA,Williams K.Food preferences and factors influencing foodselectivity for children with autism spectrum disorders.Res Dev Disabil 2006;27:353–63.[34]Nadon G,Feldman DE,Dunn W,Gisel E.Mealtime problems in childrenwith autism spectrum disorder and their typically developing siblings:a comparison study.Autism2011;15:98–113.[35]Emond A,Emmett P,Steer C,Golding J.Feeding symptoms,dietarypatterns,and growth in young children with autism spectrum disorders.Pediatrics2010;126:e337–42.[36]Kocovska E,Fernell E,Billstedt E,Minnis H,Gillberg C.Vitamin D andautism:clinical review.Res Dev Disabil2012;33:1541–50.[37]Herndon AC,DiGuiseppi C,Johnson SL,Leiferman J,Reynolds A.Does nutri-tional intake differ between children with autism spectrum disorders and children with typical development?J Autism Dev Disord2009;39:212–22.[38]Piyathilake CJ,Macaluso M,Alvarez RD,Chen M,Badiga S,Siddiqui NR,et al.Ahigher degree of LINE-1methylation in peripheral blood mononuclear cells,a one-carbon nutrient related epigenetic alteration,is associated with a lowerrisk of developing cervical intraepithelial neoplasia.Nutrition2011;27:513–9.[39]Gammon CS,von Hurst PR,Coad J,Kruger R,Stonehouse W.Vegetarianism,vitamin B12status,and insulin resistance in a group of predominantly overweight/obese South Asian women.Nutrition2012;28:20–4.[40]Fadyl H,Inoue bined B12and iron deficiency in a child breast-fed bya vegetarian mother.J Pediatr Hematol Oncol2007;29:74.[41]Chatthanawaree W.Biomarkers of cobalamin(vitamin B12)deficiency andits application.J Nutr Health Aging2011;15:227–31.[42]Reynolds E.Vitamin B12,folic acid,and the nervous ncet Neurol2006;5:949–60.[43]Haapamäki J,Roine RP,Turunen U,FärkkiläMA,Arkkila PE.Increased riskfor coronary heart disease,asthma,and connective tissue diseases in inflammatory bowel disease.J Crohn Dis Colitis2011;5:41–7.[44]Hjiej H,Doyen C,Couprie C,Kaye K,Contejean Y.Substitutive and dieteticapproaches in childhood autistic disorder:interests and limits.Encephale 2008;34:496–503.[45]Rempel GR,Blythe C,Rogers LG,Ravindran V.The process of familymanagement when a baby is diagnosed with a lethal congenital condition.J Fam Nurs2012;18:35–64.[46]Alasfoor DH,AlRassasi B,Rajab H.National food based dietary guidelinesfor Oman d a technical report.Muscat:Department of Nutrition,Ministry of Health;2007.[47]Grosse SD,Waitzman NJ,Romano PS,Mulinare J.Reevaluating the benefitsof folic acid fortification in the United States:economic analysis,regulation, and public health.Am J Publ Health2005;95:1917–22.[48]Sayers GM,Hughes N,Scallan E,Johnson Z.A survey of knowledge and useof folic acid among women of childbearing age in Dublin.J Publ Health Med1997;19:328–32.Y.M.Al-Farsi et al./Nutrition29(2013)537–541541。