国际经济学(克鲁格曼)教材答案

国际经济学克鲁格曼课后习题答案章完整版

国际经济学克鲁格曼课后习题答案章集团标准化办公室:[VV986T-J682P28-JP266L8-68PNN]第一章练习与答案1.为什么说在决定生产和消费时,相对价格比绝对价格更重要?答案提示:当生产处于生产边界线上,资源则得到了充分利用,这时,要想增加某一产品的生产,必须降低另一产品的生产,也就是说,增加某一产品的生产是有机会机本(或社会成本)的。

生产可能性边界上任何一点都表示生产效率和充分就业得以实现,但究竟选择哪一点,则还要看两个商品的相对价格,即它们在市场上的交换比率。

相对价格等于机会成本时,生产点在生产可能性边界上的位置也就确定了。

所以,在决定生产和消费时,相对价格比绝对价格更重要。

2.仿效图1—6和图1—7,试推导出Y商品的国民供给曲线和国民需求曲线。

答案提示:3.在只有两种商品的情况下,当一个商品达到均衡时,另外一个商品是否也同时达到均衡?试解释原因。

答案提示:4.如果生产可能性边界是一条直线,试确定过剩供给(或需求)曲线。

答案提示:5.如果改用Y商品的过剩供给曲线(B国)和过剩需求曲线(A国)来确定国际均衡价格,那么所得出的结果与图1—13中的结果是否一致?6.答案提示:国际均衡价格将依旧处于贸易前两国相对价格的中间某点。

7.说明贸易条件变化如何影响国际贸易利益在两国间的分配。

答案提示:一国出口产品价格的相对上升意味着此国可以用较少的出口换得较多的进口产品,有利于此国贸易利益的获得,不过,出口价格上升将不利于出口数量的增加,有损于出口国的贸易利益;与此类似,出口商品价格的下降有利于出口商品数量的增加,但是这意味着此国用较多的出口换得较少的进口产品。

对于进口国来讲,贸易条件变化对国际贸易利益的影响是相反的。

8.如果国际贸易发生在一个大国和一个小国之间,那么贸易后,国际相对价格更接近于哪一个国家在封闭下的相对价格水平?答案提示:贸易后,国际相对价格将更接近于大国在封闭下的相对价格水平。

克鲁格曼《国际经济学》(国际金融部分)课后习题答案(英文版)第一章

克鲁格曼《国际经济学》(国际金融部分)课后习题答案(英文版)第一章CHAPTER 1INTRODUCTIONChapter OrganizationWhat is International Economics About?The Gains from TradeThe Pattern of TradeProtectionismThe Balance of PaymentsExchange-Rate DeterminationInternational Policy CoordinationThe International Capital MarketInternational Economics: Trade and MoneyCHAPTER OVERVIEWThe intent of this chapter is to provide both an overview of the subject matter of international economics and to provide a guide to the organization of the text. It is relatively easy for an instructor to motivate the study of international trade and finance. The front pages of newspapers, the covers of magazines, and the lead reports of television news broadcasts herald the interdependence of the U.S. economy with the rest of the world. This interdependence may also be recognized by students through their purchases of imports of all sorts of goods, their personal observations of the effects of dislocations due to international competition, and their experience through travel abroad.The study of the theory of international economics generates an understanding of many key events that shape our domesticand international environment. In recent history, these events include the causes and consequences of the large current account deficits of the United States; the dramatic appreciation of the dollar during the first half of the 1980s followed by its rapid depreciation in the second half of the 1980s; the Latin American debt crisis of the 1980s and the Mexico crisis in late 1994; and the increased pressures for industry protection against foreign competition broadly voiced in the late 1980s and more vocally espoused in the first half of the 1990s. Most recently, the financial crisis that began in East Asia in 1997 andspread to many countries around the globe and the Economic and Monetary Union in Europe have highlighted the way in which various national economies are linked and how important it is for us to understand these connections. At the same time, protests at global economic meetings have highlighted opposition to globalization. The text material will enable students to understand the economic context in which such events occur.Chapter 1 of the text presents data demonstrating the growth in trade and increasing importance of international economics. This chapter also highlights and briefly discusses seven themes which arise throughout the book. These themes include: 1) the gains from trade;2) the pattern of trade; 3) protectionism; 4), the balance of payments; 5) exchange rate determination; 6) international policy coordination; and 7) the international capital market. Students will recognize that many of the central policy debates occurring today come under the rubric of one of these themes. Indeed, it is often a fruitful heuristic to use current events to illustrate the force of the key themes and arguments which are presentedthroughout the text.。

克鲁格曼国际经济学课后答案

克鲁格曼国际经济学课后答案【篇一:克鲁格曼《国际经济学》(国际金融)习题答案要点】lass=txt>第12章国民收入核算和国际收支1、如问题所述,gnp仅仅包括最终产品和服务的价值是为了避免重复计算的问题。

在国民收入账户中,如果进口的中间品价值从gnp中减去,出口的中间品价值加到gnp中,重复计算的问题将不会发生。

例如:美国分别销售钢材给日本的丰田公司和美国的通用汽车公司。

其中出售给通用公司的钢材,作为中间品其价值不被计算到美国的gnp中。

出售给日本丰田公司的钢材,钢材价值通过丰田公司进入日本的gnp,而最终没有进入美国的国民收入账户。

所以这部分由美国生产要素创造的中间品价值应该从日本的gnp中减去,并加入美国的gnp。

2、(1)等式12-2可以写成ca?(sp?i)?(t?g)。

美国更高的进口壁垒对私人储蓄、投资和政府赤字有比较小或没有影响。

(2)既然强制性的关税和配额对这些变量没有影响,所以贸易壁垒不能减少经常账户赤字。

不同情况对经常账户产生不同的影响。

例如,关税保护能提高被保护行业的投资,从而使经常账户恶化。

(当然,使幼稚产业有一个设备现代化机会的关税保护是合理的。

)同时,当对投资中间品实行关税保护时,由于受保护行业成本的提高可能使该行业投资下降,从而改善经常项目。

一般地,永久性和临时性的关税保护有不同的效果。

这个问题的要点是:政策影响经常账户方式需要进行一般均衡、宏观分析。

3、(1)、购买德国股票反映在美国金融项目的借方。

相应地,当美国人通过他的瑞士银行账户用支票支付时,因为他对瑞士请求权减少,故记入美国金融项目的贷方。

这是美国用一个外国资产交易另外一种外国资产的案例。

(2)、同样,购买德国股票反映在美国金融项目的借方。

当德国销售商将美国支票存入德国银行并且银行将这笔资金贷给德国进口商(此时,记入美国经常项目的贷方)或贷给个人或公司购买美国资产(此时,记入美国金融项目的贷方)。

最后,银行采取的各项行为将导致记入美国国际收支表的贷方。

国际经济学 (克鲁格曼) 教材解答

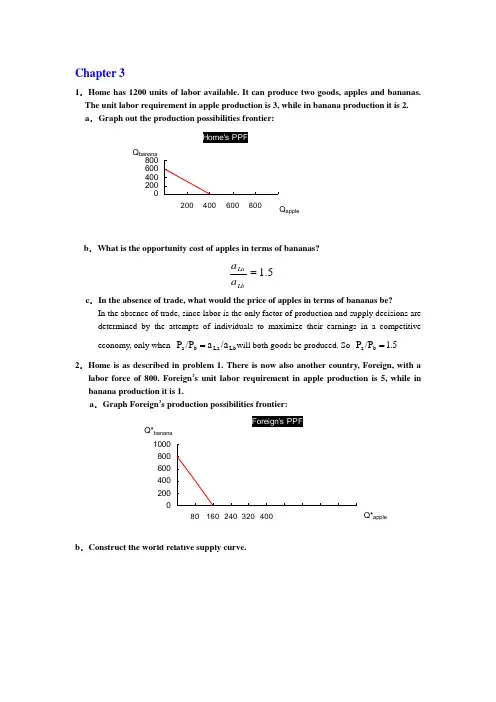

Chapter 31.Home has 1200 units of labor available. It can produce two goods, apples and bananas. The unit labor requirement in apple production is 3, while in banana production it is 2. a .Graph out the production possibilities frontier:b .What is the opportunity cost of apples in terms of bananas?5.1=LbLa a a c .In the absence of trade, what would the price of apples in terms of bananas be?In the absence of trade, since labor is the only factor of production and supply decisions aredetermined by the attempts of individuals tomaximize their earnings in a competitive economy, only when Lb La b a /a a /P P =will both goods be produced. So 1.5 /P P b a =2.Home is as described in problem 1. There is now also another country, Foreign, with alabor force of 800. Foreign ’s unit labor requirement in apple production is 5, while in banana production it is 1.a .Graph Foreign ’s production possibilities frontier:b .3.Now suppose world relative demand takes the following form: Demand for apples/demand for bananas = price of bananas/price of apples.a .Graph the relative demand curve along with the relative supply curve:a b b a /P P /D D =∵When the market achieves its equilibrium, we have 1b a )(D D -**=++=ba b b a a P P Q Q Q Q ∴RD is a hyperbola xy 1=b .What is the equilibrium relative price of apples?The equilibrium relative price of apples is determined by the intersection of the RD and RScurves.RD: yx 1= RS: 5]5,5.1[5.1],5.0(5.0)5.0,0[=∈=⎪⎩⎪⎨⎧+∞∈=∈y y y x x x ∴25.0==y x∴2/=b P a P e ec .Describe the pattern of trade.∵b a b e a e b a P P P P P P ///>>**∴In this two-country world, Home will specialize in the apple production, export apples and import bananas. Foreign will specialize in the banana production, export bananas and import apples.d .Show that both Home and Foreign gain from trade.International trade allows Home and Foreign to consume anywhere within the coloredlines, which lie outside the countries ’ production possibility frontiers. And the indirect method, specializing in producing only one production then trade with other country, is a more efficient method than direct production. In the absence of trade, Home could gain three bananas by foregoing two apples, and Foreign could gain by one foregoing five bananas. Trade allows each country to trade two bananas for one apple. Home could then gain four bananas by foregoing two apples while Foreign could gain one apple by foregoing only two bananas. So both Home and Foreign gain from trade.4.Suppose that instead of 1200 workers, Home had 2400. Find the equilibrium relative price. What can you say about the efficiency of world production and the division of the gains from trade between Home and Foreign in this case? RD: yx 1= RS: 5]5,5.1[5.1],1(1)1,0[=∈=⎪⎩⎪⎨⎧+∞∈=∈y y y x x x ∴5.132==y x∴5.1/=b P a P e eIn this case, Foreign will specialize in the banana production, export bananas and import apples. But Home will produce bananas and apples at the same time. And the opportunity cost of bananas in terms of apples for Home remains the same. So Home neither gains nor loses but Foreign gains from trade.5.Suppose that Home has 2400 workers, but they are only half as production in both industries as we have been assuming, Construct the world relative supply curve and determine the equilibrium relative price. How do the gains from trade compare with those in the case described in problem 4?In this case, the labor is doubled while the productivity of labor is halved, so the "effective labor"remains the same. So the answer is similar to that in 3. And both Home and Foreign can gain from trade. But Foreign gains lesser compare with that in the case 4.6.”Korean workers earn only $2.50 an hour; if we allow Korea to export as much as it likes to the United States, our workers will be forced down to the same level. Y ou can’t import a $5 shirt without importing the $2.50 wage that goes with it.” Discuss.In fact, relative wage rate is determined by comparative productivity and the relative demand for goods. Korea’s low wage reflects the fact that Korea is less productive than the United States in most industries. Actually, trade with a less productive, low wage country can raise the welfare and standard of living of countries with high productivity, such as United States. Sothis pauper labor argument is wrong.7.Japanese labor productivity is roughly the same as that of the United States in the manufacturing sector (higher in some industries, lower in others), while the United States, is still considerably more productive in the service sector. But most services are non-traded. Some analysts have argued that this poses a problem for the United States, because our comparative advantage lies in things we cannot sell on world markets. What is wrong with this argument?The competitive advantage of any industry depends on both the relative productivities of the industries and the relative wages across industries. So there are four aspects should be taken into account before we reach conclusion: both the industries and service sectors of Japan and U.S., not just the two service sectors. So this statement does not bade on the reasonable logic. 8.Anyone who has visited Japan knows it is an incredibly expensive place; although Japanese workers earn about the same as their U.S. counterparts, the purchasing power of their incomes is about one-third less. Extend your discussing from question 7 to explain this observation. (Hint: Think about wages and the implied prices of non-trade goods.) The relative higher purchasing power of U.S. is sustained and maintained by its considerably higher productivity in services. Because most of those services are non-traded, Japanese could not benefit from those lower service costs. And U.S. does not have to face a lower international price of services. So the purchasing power of Japanese is just one-third of their U.S. counterparts.9.How does the fact that many goods are non-traded affect the extent of possible gains from trade?Actually the gains from trade depended on the proportion of non-traded goods. The gains will increase as the proportion of non-traded goods decrease.10.We have focused on the case of trade involving only two countries. Suppose that there are many countries capable of producing two goods, and that each country has only one factor of production, labor. What could we say about the pattern of production and in this case? (Hint: Try constructing the world relative supply curve.)Any countries to the left of the intersection of the relative demand and relative supply curves export the good in which they have a comparative advantage relative to any country to the right of the intersection. If the intersection occurs in a horizontal portion then the country with that price ratio produces both goods.Chapter 41. In the United States where land is cheap, the ratio of land to labor used in cattle rising ishigher than that of land used in wheat growing. But in more crowded countries, where land is expensive and labor is cheap, it is common to raise cows by using less land and more labor than Americans use to grow wheat. Can we still say that raising cattle is land intensive compared with farming wheat? Why or why not?The definition of cattle growing as land intensive depends on the ratio of land to labor used inproduction, not on the ratio of land or labor to output. The ratio of land to labor in cattle exceeds the ratio in wheat in the United States, implying cattle is land intensive in the United States. Cattle is land intensive in other countries too if the ratio of land to labor in cattle production exceeds the ratio in wheat production in that country. The comparison between another country and the United States is less relevant for answering the question.2. Suppose that at current factor prices cloth is produced using 20 hours of labor for eachacre of land, and food is produced using only 5 hours of labor per acre of land.a. Suppose that the economy ’s total resources are 600 hours of labor and 60 acres ofland. Using a diagram determine the allocation of resources.5TF LF /TF LF /QF)(TF / /QF)(LF aTF / aLF 20TC LC /TC LC /QC)(TC / /QC)(LC aTC / aLC =⇒===⇒==We can solve this algebraically since L=LC+LF=600 and T=TC+TF=60. The solution is LC=400, TC=20, LF=200 and TF=40.b. Now suppose that the labor supply increase first to 800, then 1000, then 1200 hours.Using a diagram like Figure4-6, trace out the changing allocation of resources. Labor Land ClothFoodLC LF TCTFtion).specializa (complete 0.LF 0,TF 1200,LC 60,TC :1200L 66.67LF 13.33,TF 933.33,LC 46.67,TC :1000L 133.33LF 26.67,TF 666.67,LC 33.33,TC :800L ===============c. What would happen if the labor supply were to increase even further?At constant factor prices, some labor would be unused, so factor prices would have to change, or there would be unemployment.3. “The world ’s poorest countries cannot find anything to export. There is no resource thatis abundant — certainly not capital or land, and in small poor nations not even labor is abundant.” Discuss.The gains from trade depend on comparative rather than absolute advantage. As to poor countries, what matters is not the absolute abundance of factors, but their relative abundance. Poor countries have an abundance of labor relative to capital when compared to more developed countries.4. The U.S. labor movement — which mostly represents blue-collar workers rather thanprofessionals and highly educated workers — has traditionally favored limits on imports form less-affluent countries. Is this a shortsighted policy of a rational one in view of the interests of union members? How does the answer depend on the model of trade?In the Ricardo ’s model, labor gains from trade through an increase in its purchasing power. This result does not support labor union demands for limits on imports from less affluent countries.In the Immobile Factors model labor may gain or lose from trade. Purchasing power in terms of one good will rise, but in terms of the other good it will decline.The Heckscher-Ohlin model directly discusses distribution by considering the effects of trade on the owners of factors of production. In the context of this model, unskilled U.S. labor loses from trade since this group represents the relatively scarce factors in this country. The results from the Heckscher-Ohlin model support labor union demands for import limits.5. There is substantial inequality of wage levels between regions within the United States. Labor Land ClothFood0l 800 0l 1000 0l 1200For example, wages of manufacturing workers in equivalent jobs are about 20 percent lower in the Southeast than they are in the Far West. Which of the explanations of failure of factor price equalization might account for this? How is this case different from the divergence of wages between the United States and Mexico (which is geographically closer to both the U.S. Southeast and the Far West than the Southeast and Far West are to each other)?When we employ factor price equalization, we should pay attention to its conditions: both countries/regions produce both goods; both countries have the same technology of production, and the absence of barriers to trade. Inequality of wage levels between regions within the United States may caused by some or all of these reasons.Actually, the barriers to trade always exist in the real world due to transportation costs. And the trade between U.S. and Mexico, by contrast, is subject to legal limits; together with cultural differences that inhibit the flow of technology, this may explain why the difference in wage rates is so much larger.6.Explain why the Leontief paradox and the more recent Bowen, Leamer, andSveikauskas results reported in the text contradict the factor-proportions theory.The factor proportions theory states that countries export those goods whose production is intensive in factors with which they are abundantly endowed. One would expect the United States, which has a high capital/labor ratio relative to the rest of the world, to export capital-intensive goods if the Heckscher-Ohlin theory holds. Leontief found that the United States exported labor-intensive goods. Bowen, Leamer and Sveikauskas found that the correlation between factor endowment and trade patterns is weak for the world as a whole.The data do not support the predictions of the theory that countries' exports and imports reflect the relative endowments of factors.7.In the discussion of empirical results on the Heckscher-Ohlin model, we noted thatrecent work suggests that the efficiency of factors of production seems to differ internationally. Explain how this would affect the concept of factor price equalization.If the efficiency of the factors of production differs internationally, the lessons of the Heckscher-Ohlin theory would be applied to “effective factors” which adjust for the differences in technology or worker skills or land quality (for example). The adjusted model has been found to be more successful than the unadjusted model at explaining the pattern of trade between countries. Factor-price equalization concepts would apply to the effective factors. A worker with more skills or in a country with better technology could be considered to be equal to two workers in another country. Thus, the single person would be two effective units of labor. Thus, the one high-skilled worker could earn twice what lower skilled workers do and the price of one effective unit of labor would still be equalized.chapter 81. The import demand equation, MD, is found by subtracting the home supply equation from the home demand equation. This results in MD = 80 - 40 x P. Without trade, domestic prices and quantities adjust such that import demand is zero. Thus, the price in the absence of trade is2.2. a. Foreign's export supply curve, XS, is XS = -40 + 40 x P. In the absence of trade, the price is 1.b. When trade occurs export supply is equal to import demand, XS = MD. Thus, using theequations from problems 1 and 2a, P = 1.50, and the volume of trade is 20.3. a. The new MD curve is 80 - 40 x (P+t) where t is the specific tariff rate, equal to 0.5. (Note: in solving these problems you should be careful about whether a specific tariff or ad valorem tariff is imposed. With an ad valorem tariff, the MD equation would be expressed as MD =80-40 x (1+t)P). The equation for the export supply curve by the foreign country is unchanged. Solving, we find that the world price is $1.25, and thus the internal price at home is $1.75. The volume of trade has been reduced to 10, and the total demand for wheat at home has fallen to 65 (from the free trade level of 70). The total demand for wheat in Foreign has gone up from 50 to 55.b. andc. The welfare of the home country is best studied using the combined numerical andgraphical solutions presented below in Figure 8-1.P T =1.7550556070QuantityPrice P W =1.50P T*=1.25where the areas in the figure are:a: 55(1.75-1.50) -.5(55-50)(1.75-1.50)=13.125b: .5(55-50)(1.75-1.50)=0.625c: (65-55)(1.75-1.50)=2.50d: .5(70-65)(1.75-1.50)=0.625e: (65-55)(1.50-1.25)=2.50Consumer surplus change: -(a+b+c+d)=-16.875. Producer surplus change: a=13.125. Government revenue change: c+e=5. Efficiency losses b+d are exceeded by terms of trade gain e. [Note: in the calculations for the a, b, and d areas a figure of .5 shows up. This is because we are measuring the area of a triangle, which is one-half of the area of the rectangle defined by the product of the horizontal and vertical sides.]4. Using the same solution methodology as in problem 3, when the home country is very small relative to the foreign country, its effects on the terms of trade are expected to be much less. The small country is much more likely to be hurt by its imposition of a tariff. Indeed, this intuition is shown in this problem. The free trade equilibrium is now at the price $1.09 and the trade volume is now $36.40.With the imposition of a tariff of 0.5 by Home, the new world price is $1.045, the internal home price is $1.545, home demand is 69.10 units, home supply is 50.90 and the volume of trade is 18.20. When Home is relatively small, the effect of a tariff on world price is smaller than when Home is relatively large. When Foreign and Home were closer in size, a tariff of .5 by home lowered world price by 25 percent, whereas in this case the same tariff lowers world price byabout 5 percent. The internal Home price is now closer to the free trade price plus t than when Home was relatively large. In this case, the government revenues from the tariff equal 9.10, the consumer surplus loss is 33.51, and the producer surplus gain is 21.089. The distortionary losses associated with the tariff (areas b+d) sum to 4.14 and the terms of trade gain (e) is 0.819. Clearly, in this small country example the distortionary losses from the tariff swamp the terms of trade gains. The general lesson is the smaller the economy, the larger the losses from a tariff since the terms of trade gains are smaller.5. The effective rate of protection takes into consideration the costs of imported intermediate goods. In this example, half of the cost of an aircraft represents components purchased from other countries. Without the subsidy the aircraft would cost $60 million. The European value added to the aircraft is $30 million. The subsidy cuts the cost of the value added to purchasers of the airplane to $20 million. Thus, the effective rate of protection is (30 - 20)/20 = 50%.6. We first use the foreign export supply and domestic import demand curves to determine the new world price. The foreign supply of exports curve, with a foreign subsidy of 50 percent per unit, becomes XS= -40 + 40(1+0.5) x P. The equilibrium world price is 1.2 and the internal foreign price is 1.8. The volume of trade is 32. The foreign demand and supply curves are used to determine the costs and benefits of the subsidy. Construct a diagram similar to that in the text and calculate the area of the various polygons. The government must provide (1.8 - 1.2) x 32 = 19.2 units of output to support the subsidy. Foreign producers surplus rises due to the subsidy by the amount of 15.3 units of output. Foreign consumers surplus falls due to the higher price by7.5 units of the good. Thus, the net loss to Foreign due to the subsidy is 7.5 + 19.2 - 15.3 = 11.4 units of output. Home consumers and producers face an internal price of 1.2 as a result of the subsidy. Home consumers surplus rises by 70 x .3 + .5 (6x.3) = 21.9 while Home producers surplus falls by 44 x .3 + .5(6 x .3) = 14.1, for a net gain of 7.8 units of output.7. At a price of $10 per bag of peanuts, Acirema imports 200 bags of peanuts. A quota limiting the import of peanuts to 50 bags has the following effects:a. The price of peanuts rises to $20 per bag.b. The quota rents are ($20 - $10) x 50 = $500.c. The consumption distortion loss is .5 x 100 bags x $10 per bag = $500.x50 bags x$10 per bag = $250.。

《国际经济学》克鲁格曼(第六版)习题答案imsect4

OVERVIEW OF SECTION IV: INTERNATIONAL MACROECONOMIC POLICYPart IV of the text is comprised of five chapters:Chapter 18 The International Monetary System, 1870-1973Chapter 19 Macroeconomic Policy and Coordination Under Floating Exchange Rates Chapter 20 Optimum Currency Areas and The European ExperienceChapter 21 The Global Capital Market: Performance and Policy ProblemsChapter 22 Developing Countries: Growth, Crisis, and ReformSECTION OVERVIEWThis final section of the book, which discusses international macroeconomic policy, provides historical and institutional background to complement the theoretical presentation of the previous section. These chapters also provide an opportunity for students to hone their analytic skills and intuition by applying and extending the models learned in Part III to a range of current and historical issues.The first two chapters of this section discuss various international monetary arrangements. These chapters describe the workings of different exchange rate systems through the central theme of internal and external balance. The model developed in the previous section provides a general framework for analysis of gold standard, reserve currency, managed floating, and floating exchange-rate systems.Chapter 18 chronicles the evolution of the international monetary system from the gold standard of 1870 - 1914, through the interwar years, and up to and including the post-war Bretton Woods period. The chapter discusses the price-specie-flow mechanism of adjustment in the context of the discussion of the gold standard. Conditions for internal and external balance are presented through diagrammatic analysis based upon the short-run macroeconomic model of Chapter 16. This analysis illustrates the strengths and weaknesses of alternative fixed exchange rate arrangements. The chapter also draws upon earlier discussion of balance of payments crises to make clear the interplay between "fundamental disequilibrium" and speculative attacks. There is a detailed analysis of the Bretton Woodssystem that includes a case study of the experience during its decline beginning in the mid-1960s and culminating with its collapse in 1973.Chapter 19 focuses on recent experience under floating exchange rates. The discussion is couched in terms of current debate concerning the advantages of floating versus fixed exchange rate systems. The theoretical arguments for and against floating exchange rates frame two case studies, the first on the experience between the two oil shocks in the 1970s and the second on the experience since 1980. The transmission of monetary and fiscal shocks from one country to another is also considered. Discussion of the experience in the 1980s points out the shift in policy toward greater coordination in the second half of the decade. Discussion of the 1990s focuses on the strong U.S. economy from 1992 on and the extended economic difficulties in Japan. Finally, the chapter considers what has been learned about floating rates since 1973. The appendix illustrates losses arising from uncoordinated international monetary policy using a game theory setup.Europe’s switch to a single currency, the euro, is the subject of Chapter 20, and provides a particular example of a single currency system. The chapter discusses the history of the European Monetary System and its precursors. The early years of the E.M.S. were marked by capital controls and frequent realignments. By the end of the 1980s, however, there was marked inflation convergence among E.M.S. members, few realignments and the removal of capital controls. Despite a speculative crisis in 1992-3, leaders pressed on with plans for the establishment of a single European currency as outlined in the Maastricht Treaty which created Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). The single currency was viewed as an important part of the EC 1992 initiative which called for the free flow within Europe of labor, capital, goods and services. The single currency, the euro, was launched on January 1, 1999 with eleven original participants. These countries have ceded monetary authority to a supranational central bank and constrained their fiscal policy with agreements on convergence criteria and the stability and growth pact. A single currency imposes costs as well as confers benefits. The theory of optimum currency areas suggests conditions which affect the relative benefits of a single currency. The chapter provides a way to frame this analysis using the GG-LL diagram which compares the gains and losses from a single currency. Finally, the chapter examines the prospects of the EU as an optimal currency area compared to the United States and considers the future challenges EMU will face.The international capital market is the subject of Chapter 21. This chapter draws an analogy between the gains from trade arising from international portfolio diversification andinternational goods trade. There is discussion of institutional structures that have arisen to exploit these gains. The chapter discusses the Eurocurrency market, the regulation of offshore banking, and the role of international financial supervisory cooperation. The chapter examines policy issues of financial markets, the policy trilemma of the incompatibility of fixed rates, independent monetary policy, and capital mobility as well as the tension between supporting financial stability and creating a moral hazard when a government intervenes in financial markets. The chapter also considers evidence of how well the international capital market has performed by focusing on issues such as the efficiency of the foreign exchange market and the existence of excess volatility of exchange rates.Chapter 22 discusses issues facing developing countries. The chapter begins by identifying characteristics of the economies of developing countries, characteristics that include undeveloped financial markets, pervasive government involvement, and a dependence on commodity exports. The macroeconomic analysis of previous chapters again provides a framework for analyzing relevant issues, such as inflation in or capital flows to developing countries. Borrowing by developing countries is discussed as an attempt to exploit gains from intertemporal trade and is put in historical perspective. Latin American countries’ problems with inflation and subsequent attempts at reform are detailed. Finally, the East Asian economic miracle is revisited (it is discussed in Chapter 10), and the East Asian financial crisis is examined. This final topic provides an opportunity to discuss possible reforms of the world’s financial architecture.。

国际经济学(克鲁格曼)课后习题答案1-8章

第一章练习与答案1.为什么说在决定生产和消费时,相对价格比绝对价格更重要?答案提示:当生产处于生产边界线上,资源则得到了充分利用,这时,要想增加某一产品的生产,必须降低另一产品的生产,也就是说,增加某一产品的生产是有机会机本(或社会成本)的。

生产可能性边界上任何一点都表示生产效率和充分就业得以实现,但究竟选择哪一点,则还要看两个商品的相对价格,即它们在市场上的交换比率。

相对价格等于机会成本时,生产点在生产可能性边界上的位置也就确定了。

所以,在决定生产和消费时,相对价格比绝对价格更重要。

2.仿效图1—6和图1—7,试推导出Y商品的国民供给曲线和国民需求曲线。

答案提示:3.在只有两种商品的情况下,当一个商品达到均衡时,另外一个商品是否也同时达到均衡?试解释原因。

答案提示:4.如果生产可能性边界是一条直线,试确定过剩供给(或需求)曲线。

答案提示:5.如果改用Y商品的过剩供给曲线(B国)和过剩需求曲线(A 国)来确定国际均衡价格,那么所得出的结果与图1—13中的结果是否一致?答案提示:国际均衡价格将依旧处于贸易前两国相对价格的中间某点。

6.说明贸易条件变化如何影响国际贸易利益在两国间的分配。

答案提示:一国出口产品价格的相对上升意味着此国可以用较少的出口换得较多的进口产品,有利于此国贸易利益的获得,不过,出口价格上升将不利于出口数量的增加,有损于出口国的贸易利益;与此类似,出口商品价格的下降有利于出口商品数量的增加,但是这意味着此国用较多的出口换得较少的进口产品。

对于进口国来讲,贸易条件变化对国际贸易利益的影响是相反的。

7.如果国际贸易发生在一个大国和一个小国之间,那么贸易后,国际相对价格更接近于哪一个国家在封闭下的相对价格水平?答案提示:贸易后,国际相对价格将更接近于大国在封闭下的相对价格水平。

8.根据上一题的答案,你认为哪个国家在国际贸易中福利改善程度更为明显些?答案提示:小国。

9*.为什么说两个部门要素使用比例的不同会导致生产可能性边界曲线向外凸?答案提示:第二章答案1.根据下面两个表中的数据,确定(1)贸易前的相对价格;(2)比较优势型态。

《国际经济学》克鲁格曼(第六版)习题答案imsect3

OVERVIEW OF SECTION III: EXCHANGE RATES AND OPEN ECONOMY MACROECONOMICSSection III of the textbook is comprised of six chapters:Chapter 12 National Income Accounting and the Balance of PaymentsChapter 13 Exchange Rates and the Foreign Exchange Market: An Asset Approach Chapter 14 Money, Interest Rates, and Exchange RatesChapter 15 Price Levels and the Exchange Rate in the Long RunChapter 16 Output and the Exchange Rate in the Short RunChapter 17 Fixed Exchange Rates and Foreign Exchange InterventionSECTION III OVERVIEWThe presentation of international finance theory proceeds by building up an integrated model of exchange rate and output determination. Successive chapters in Part III construct this model step by step so students acquire a firm understanding of each component as well as the manner in which these components fit together. The resulting model presents a single unifying framework admitting the entire range of exchange rate regimes from pure float to managed float to fixed rates. The model may be used to analyze both comparative static and dynamic time path results arising from temporary or permanent policy or exogenous shocks in an open economy.The primacy given to asset markets in the model is reflected in the discussion of national income and balance of payments accounting in the first chapter of this section. Chapter 12 begins with a discussion of the focus of international finance. The discussion then proceeds to national income accounting in an open economy. The chapter points out, in the discussion on the balance of payments account, that current account transactions must be financed by financial account flows from either central bank or noncentral bank transactions. A case study uses national income accounting identities to consider the link between government budget deficits and the current account.Observed behavior of the exchange rate favors modeling it as an asset price rather than as a goods price. Thus, the core relationship for short-run exchange-rate determination in the model developed in Part III is uncovered interest parity. Chapter 13 presents a model inwhich the exchange rate adjusts to equate expected returns on interest-bearing assets denominated in different currencies given expectations about exchange rates, and the domestic and foreign interest rate. This first building block of the model lays the foundation for subsequent chapters that explore the determination of domestic interest rates and output, the basis for expectations of future exchange rates and richer specifications of the foreign-exchange market that include risk. An appendix to this chapter explains the determination of forward exchange rates.Chapter 14 introduces the domestic money market, linking monetary factors to short-run exchange-rate determination through the domestic interest rate. The chapter begins with a discussion of the determination of the domestic interest rate. Interest parity links the domestic interest rate to the exchange rate, a relationship captured in a two-quadrant diagram. Comparative statics employing this diagram demonstrate the effects of monetary expansion and contraction on the exchange rate in the short run. Dynamic considerations are introduced through an appeal to the long run neutrality of money that identifies a long-run steady-state value toward which the exchange rate evolves. The dynamic time path of the model exhibits overshooting of the exchange-rate in response to monetary changes.Chapter 15 develops a model of the long run exchange rate. The long-run exchange rate plays a role in a complete short-run macroeconomic model since one variable in that model is the expected future exchange rate. The chapter begins with a discussion of the law of one price and purchasing power parity. A model of the exchange rate in the long-run based upon purchasing power parity is developed. A review of the empirical evidence, however, casts doubt on this model. The chapter then goes on to develop a general model of exchange rates in the long run in which the neutrality of monetary shocks emerges as a special case. In contrast, shocks to the output market or changes in fiscal policy alter the long run real exchange rate. This chapter also discusses the real interest parity relationship that links the real interest rate differential to the expected change in the real exchange rate. An appendix examines the relationship of the interest rate and exchange rate under a flexible-price monetary approach.Chapter 16 presents a macroeconomic model of output and exchange-rate determination in the short run. The chapter introduces aggregate demand in a setting of short-run price stickiness to construct a model of the goods market. The exchange-rate analysis presented in previous chapters provides a model of the asset market. The resulting model is, in spirit, very close to the classic Mundell-Fleming model. This model is used to examine the effects of avariety of policies. The analysis allows a distinction to be drawn between permanent and temporary policy shifts through the pedagogic device that permanent policy shifts alter long-run expectations while temporary policy shifts do not. This distinction highlights the importance of exchange-rate expectations on macroeconomic outcomes. A case study of U.S. fiscal and monetary policy between 1979 and 1983 utilizes the model to explain notable historical events. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the links between exchange rate and import price movements which focuses on the J-curve and exchange-rate pass-through. An appendix to the chapter compares the IS-LM model to the model developed in this chapter. A second appendix considers intertemporal trade and consumption demand. A third appendix discusses the Marshall-Lerner condition and estimates of trade elasticities.The final chapter of this section discusses intervention by the central bank and the relationship of this policy to the money supply. This analysis is blended with the previous chapter's short-run macroeconomic model to analyze policy under fixed rates. The balance sheet of the central bank is used to keep track of the effects of foreign exchange intervention on the money supply. The model developed in previous chapters is extended by relaxing the interest parity condition and allowing exchange-rate risk to influence agents' decisions. This allows a discussion of sterilized intervention. Another topic discussed in this chapter is capital flight and balance of payments crises with an introduction to different models of how a balance of payments or currency crisis can occur. The analysis also is extended to a two-country framework to discuss alternative systems for fixing the exchange-rate as a prelude to Part IV. An appendix to Chapter 17 develops a model of the foreign-exchange market in which risk factors make domestic-currency and foreign-currency assets imperfect substitutes.A second appendix explores the monetary approach to the balance of payments. The third appendix discusses the timing of a balance of payments crisis.。

克鲁格曼国际经济学答案(英文)

Overview of Section IInternational Trade TheorySection I of the text is comprised of six chapters: Chapter 2 Labor Productivity and Comparative Advantage: The Ricardian Model Chapter 3 Specific Factors and Income Distribution Chapter 4 Resources and Trade: The Heckscher-Ohlin Model Chapter 5 The Standard Trade Model Chapter 6 Economies of Scale, Imperfect Competition, and International Trade Chapter 7 International Factor Movements T Section I Overview Section I of the text presents the theory of international trade. The intent of this section is to explore the motives for and implications of patterns of trade between countries. The presentation proceeds by introducing successively more general models of trade, where the generality is provided by increasing the number of factors used in production, by increasing the mobility of factors of production across sectors of the economy, by introducing more general technologies applied to production, and by examining different types of market structure. Throughout Section I, policy concerns and current issues are used to emphasize the relevance of the theory of international trade for interpreting and understanding our economy. Chapter 2 gives a brief overview of world trade. In particular, it discusses what we know about the quantities and pattern of world trade today. The chapter uses the empirical relationship known as the gravity model as a framework to describe trade. This framework describes trade as a function of the size of the economies involved and their distance. It can then be used to see where countries are trading more or less than expected. The chapter also notes the growth in world trade over the previous decades and uses the previous era of globalization (pre-WWI) as context for today’s experience. Chapter 3 introduces you to international trade theory through a framework known as the Ricardian model of trade. This model addresses the issue of why two countries would want to trade with each other. This model shows how mutually-beneficial trade arises when there are two countries, each with one factor of production which can be applied toward producing each of two goods. Key concepts are introduced, such as the production possibilities frontier, comparative advantage versus absolute advantage, gains from trade, relative prices, and relative wages across countries. 4 Krugman/Obstfeld • International Economics: Theory and Policy, Seventh Edition Chapter 4 introduces what is known as the classic Heckscher-Ohlin model of international trade. Using this framework, you can work through the effects of trade on wages, prices and output. Many important and intuitive results are derived in this chapter including: the Rybczynski Theorem, the Stolper-Samuelson Theorem, and the Factor Price Equalization Theorem. Implications of the Heckscher-Ohlin model for the pattern of trade among countries are discussed, as are the failures of empirical evidence to confirm the predictions of the theory. The chapter also introduces questions of political economy in trade. One important reason for this addition to the model is to consider the effects of trade on income distribution. This approach shows that while nations generally gain from international trade, it is quite possible that specific groups within these nations could be harmed by this trade. This discussion, and related questions about protectionism versus globalization, becomes broader and even more interesting as you work through the models and different assumptions of subsequent chapters. Chapter 5 presents a general model of international trade which admits the models of the previous chapters as special cases. This “standard trade model” is depicted graphically by a general equilibrium trade model as applied to a small open economy. Relative demand and relative supply curves are used to analyze a variety of policy issues, such as the effects of economic growth, the transfer problem, and the effects of trade tariffs and production subsidies. The appendix to the chapter develops offer curve analysis. While an extremely useful tool, the standard model of trade fails to account for some important aspects of international trade. Specifically, while the factor proportions Heckscher-Ohlin theories explain some trade flows between countries, recent research in international economics has placed an increasing emphasis on economies of scale in production and imperfect competition among firms. Chapter 6 presents models of international trade that reflect these developments. The chapter begins by reviewing the concept of monopolistic competition among firms, and then showing the gains from trade which arise in such imperfectly competitive markets. Next, internal and external economies of scale in production and comparative advantage are discussed. The chapter continues with a discussion of the importance of intra-industry trade, dumping, and external economies of production. The subject matter of this chapter is important since it shows how gains from trade arise in ways that are not suggested by the standard, more traditional models of international trade. The subject matter also is enlightening given the increased emphasis on intra-industry trade in industrialized countries. Chapter 7 focuses on international factor mobility. This departs from previous chapters which assumed that the factors of production available for production within a country could not leave a country’s borders. Reasons for and the effects of international factor mobility are discussed in the context of a one-factor (labor) production and trade model. The analysis of the international mobility of labor motivates a further discussion of international mobility of capital. The international mobility of capital takes the form of international borrowing and lending. This facilitates the discussion of inter-temporal production choices and foreign direct investment behavior. 。

克鲁格曼国际经济学答案

Chapter 61.For each of the following examples, explain whether this is a case of external or internaleconomies of scale:a.Most musical wind instruments in the United States are produced by more than adozen factories in Elkhart, Indiana.b.All Hondas sold in the United States are either imported or produced in Marysville,Ohio.c.All airframes for Airbus, Europe’s only producer of large aircraft, are assembled inT oulouse, France.d.Hartford, Connecticut is the insurance capital of the northeastern United States.External economies of scale: Cases a and d. The productions of these two industries concentrate in a few locations and successfully reduce each industry's costs even when the scale of operation of individual firms remains small. External economies need not lead to imperfect competition. The benefits of geographical concentration may include a greater variety of specialized services to support industry operations and larger labor markets or thicker input markets.Internal economies of scale: Cases b and c. Both of them occur at the level of the individual firm. The larger the output of a product by a particular firm, the lower its average costs. This leads to imperfect competition as in petrochemicals, aircraft, and autos.2.In perfect competition, firm set price equal to marginal cost. Why isn’t this possiblewhen there are internal economies of scale?Unlike the case of perfectly competitive markets, under monopoly marginal revenue is not equal to price. The profit maximizing output level of a monopolist occurs where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Marginal revenue is always less than price under imperfectly competitive markets because to sell an extra unit of output the firm must lower the price of all units, not just the marginal one.3.It is often argued that the existence of increasing returns is a source of conflict betweencountries, since each country is better off if it can increase its production in those industries characterized by economies of scale. Evaluate this view in terms of both the monopolistic competition and the external economy models.Both internal economies of scale (which may lead to monopolistic competition) and external economies of scale could lead to increasing returns.By concentrating the production of each good with economies of scale in one country rather than spreading the production over several countries, the world economy will use the same amount of labor to produce more output.In the monopolistic competition model, the concentration of labor benefits the host country.The host country can capture some monopoly rents. But the rest of the world may hurt and have to face higher prices on its consumption goods.In the external economies case, such monopolistic pricing behavior is less likely since imperfectly competitive markets are less likely.4.Suppose the two countries we considered in the numerical example on pages 132-135were to integrate their automobile marker with a third country with an annual market for 3.75 million automobiles. Find the number of firms, the output per firm, and theprice per automobile in the new integrated market after trade.15.8n X 1c P c AC 2=⇒==−−→−+=+==n S Fb S n bn X F AC PHowever, since you will never see 0.8 firms, there will be 15 firms that enter the market, not16 firms since the last firm knows that it can not make positive profits. The rest of the solution is straight-forward. Using X=S/n, output per firm is 41,666 units. Using the price equation, and the fact that c=5,000, yields an equilibrium price of $7,000.5. Evaluate the relative importance of economies of scale and comparative advantage incausing the following:a. Most of the world ’s aluminum is smelted in Norway or Canada.b. Half of the world ’s large jet aircraft are assembled in Seattle.c. Most semiconductors are manufactured in either the United States or Japan.d. Most Scotch whiskey comes from Scotland.e. Much of the world ’s best wine comes from France.a. The relatively few locations for production suggest external economies of scale in production. If these operations are large, there may also be large internal economies of scale in production.b. Since economies of scale are significant in airplane production, it tends to be done by a small number of (imperfectly competitive) firms at a limited number of locations. One such location is Seattle, where Boeing produces.c. Since external economies of scale are significant in semiconductor production,semiconductor industries tend to be concentrated in certain geographic locations. If, for some historical reason, a semiconductor is established in a specific location, the export of semiconductors by that country is due to economies of scale and not comparative advantage.d. "True" scotch whiskey can only come from Scotland. The production of scotch whiskeyrequires a technique known to skilled distillers who are concentrated in the region. Also, soil and climactic conditions are favorable for grains used in local scotch production. This reflects comparative advantage.e. France has a particular blend of climactic conditions and land that is difficult to reproduce elsewhere. This generates a comparative advantage in wine production.6. There are some shops in Japan that sell Japanese goods imported back from the UnitedStates at a discount over the prices charged by other Japanese shops. How is this possible?The Japanese producers employ price discrimination across United States and Japanesemarkets, so that the goods sold in the United States are much cheaper than those sold in Japan. It may be profitable for other Japanese to purchase these goods in the United States, incur any tariffs and transportation costs, and resell the goods in Japan. Clearly, the price differential across markets may lead to such profitable chance.7. Consider a situation similar to that in Figure 6-9, in which two countries that canproduce a good are subject to forward-falling supply curves. In this case, however, suppose that the two countries have the same costs, so that their supply curves are identical.a. What would you expect to be the pattern of international specialization and trade?What would determine who produces the good?Suppose two countries that can produce a good are subject to forward-falling supply curves and are identical countries with identical curves. If one country starts out as a producer of a good, i.e. it has a head start even as a matter of historical accident, then all production will occur in that particular country and it will export to the rest of the world. b. What are the benefits of international trade in this case? Do they accrue only to thecountry that gets the industry?Consumers in both countries will pay a lower price for this good when externaleconomies are maximized through trade and all production is located in a single market. In the present example, no single country has a natural cost advantage or is worse off than it would be under autarky.8. It is fairly common for an industrial cluster to break up and for production to move tolocations with lower wages when the technology of the industry is no longer rapidly improving —when it is no longer essential to have the absolutely most modern machinery, when the need for highly skilled workers has declined, and when being at the cutting edge of innovation conveys only a small advantage. Ex plain this tendency of industrial clusters to break up in terms of the theory of external economies.External economies are important for firms as technology changes rapidly and as the“cutting edge” moves quickly with frequent innovations. As this pr ocess slows, manufacturing becomes more normal and standard and there is less advantage brought by external economies. Instead, firms look for low cost production locations. Since external economies are no longer important, firms find little advantage in being clustered and it is likely that low-wage locations will be chosen.chapter 81. The import demand equation, MD , is found by subtracting the home supply equation from the home demand equation. This results in MD = 80 - 40 x P . Without trade, domestic prices Q P,CD AC AC External Economics and Specializationand quantities adjust such that import demand is zero. Thus, the price in the absence of trade is 2.2. a. Foreign's export supply curve, XS , is XS = -40 + 40 x P . In the absence of trade, the price is 1.b. When trade occurs export supply is equal to import demand, XS = MD . Thus, using theequations from problems 1 and 2a, P = 1.50, and the volume of trade is 20.3. a. The new MD curve is 80 - 40 x (P+t) where t is the specific tariff rate, equal to 0.5. (Note: in solving these problems you should be careful about whether a specific tariff or ad valorem tariff is imposed. With an ad valorem tariff, the MD equation would be expressed as MD =80-40 x (1+t)P). The equation for the export supply curve by the foreign country is unchanged. Solving, we find that the world price is $1.25, and thus the internal price at home is $1.75. The volume of trade has been reduced to 10, and the total demand for wheat at home has fallen to 65 (from the free trade level of 70). The total demand for wheat in Foreign has gone up from 50 to 55.b. andc. The welfare of the home country is best studied using the combined numerical andgraphical solutions presented below in Figure 8-1.P T =1.7550556070QuantityPrice P W =1.50P T*=1.25where the areas in the figure are:a: 55(1.75-1.50) -.5(55-50)(1.75-1.50)=13.125b: .5(55-50)(1.75-1.50)=0.625c: (65-55)(1.75-1.50)=2.50d: .5(70-65)(1.75-1.50)=0.625e: (65-55)(1.50-1.25)=2.50Consumer surplus change: -(a+b+c+d)=-16.875. Producer surplus change: a=13.125. Government revenue change: c+e=5. Efficiency losses b+d are exceeded by terms of trade gain e. [Note: in the calculations for the a, b, and d areas a figure of .5 shows up. This is because we are measuring the area of a triangle, which is one-half of the area of the rectangle defined by the product of the horizontal and vertical sides.]4. Using the same solution methodology as in problem 3, when the home country is very small relative to the foreign country, its effects on the terms of trade are expected to be much less. The small country is much more likely to be hurt by its imposition of a tariff. Indeed, this intuition is shown in this problem. The free trade equilibrium is now at the price $1.09 and the trade volume is now $36.40.With the imposition of a tariff of 0.5 by Home, the new world price is $1.045, the internal homeprice is $1.545, home demand is 69.10 units, home supply is 50.90 and the volume of trade is 18.20. When Home is relatively small, the effect of a tariff on world price is smaller than when Home is relatively large. When Foreign and Home were closer in size, a tariff of .5 by home lowered world price by 25 percent, whereas in this case the same tariff lowers world price by about 5 percent. The internal Home price is now closer to the free trade price plus t than when Home was relatively large. In this case, the government revenues from the tariff equal 9.10, the consumer surplus loss is 33.51, and the producer surplus gain is 21.089. The distortionary losses associated with the tariff (areas b+d) sum to 4.14 and the terms of trade gain (e) is 0.819. Clearly, in this small country example the distortionary losses from the tariff swamp the terms of trade gains. The general lesson is the smaller the economy, the larger the losses from a tariff since the terms of trade gains are smaller.5. The effective rate of protection takes into consideration the costs of imported intermediate goods. In this example, half of the cost of an aircraft represents components purchased from other countries. Without the subsidy the aircraft would cost $60 million. The European value added to the aircraft is $30 million. The subsidy cuts the cost of the value added to purchasers of the airplane to $20 million. Thus, the effective rate of protection is (30 - 20)/20 = 50%.6. We first use the foreign export supply and domestic import demand curves to determine the new world price. The foreign supply of exports curve, with a foreign subsidy of 50 percent per unit, becomes XS = -40 + 40(1+0.5) x P. The equilibrium world price is 1.2 and the internal foreign price is 1.8. The volume of trade is 32. The foreign demand and supply curves are used to determine the costs and benefits of the subsidy. Construct a diagram similar to that in the text and calculate the area of the various polygons. The government must provide (1.8 - 1.2) x 32 = 19.2 units of output to support the subsidy. Foreign producers surplus rises due to the subsidy by the amount of 15.3 units of output. Foreign consumers surplus falls due to the higher price by7.5 units of the good. Thus, the net loss to Foreign due to the subsidy is 7.5 + 19.2 - 15.3 = 11.4 units of output. Home consumers and producers face an internal price of 1.2 as a result of the subsidy. Home consumers surplus rises by 70 x .3 + .5 (6x.3) = 21.9 while Home producers surplus falls by 44 x .3 + .5(6 x .3) = 14.1, for a net gain of 7.8 units of output.7. At a price of $10 per bag of peanuts, Acirema imports 200 bags of peanuts. A quota limiting the import of peanuts to 50 bags has the following effects:a. The price of peanuts rises to $20 per bag.b. The quota rents are ($20 - $10) x 50 = $500.c. The consumption distortion loss is .5 x 100 bags x $10 per bag = $500.d. The production distortion loss is .5 x50 bags x$10 per bag = $250.。

克鲁格曼《国际经济学》(第8版)课后习题详解

克鲁格曼《国际经济学》(第8版)课后习题详解克鲁格曼《国际经济学》(第8版)课后习题详解第1章绪论本章不是考试的重点章节,建议读者对本章内容只作大致了解即可,本章没有相关的课后习题。

第1篇国际贸易理论第2章世界贸易概览一、概念题1>(发展中国家(developing countries)答:发展中国家是与发达国家相对的经济上比较落后的国家,又称“欠发达国家”或“落后国家”。

通常指第三世界国家,包括亚洲、非洲、拉丁美洲及其他地区的130多个国家。

衡量一国是否为发展中国家的具体标准有很多种,如经济学家刘易斯和世界银行均提出过界定发展中国家的标准。

一般而言,凡人均收入低于美国人均收入的五分之一的国家就被定义为发展中国家。

比较贫困和落后是发展中国家的共同特点。

2>(服务外包(service outsourcing)答:服务外包是指企业将其非核心的业务外包出去,利用外部最优秀的专业化团队来承接其业务,从而使其专注于核心业务,达到降低成本、提高效率、增强企业核心竞争力和对环境应变能力的一种管理模式。

20世纪90年代以来,随着信息技术的迅速发展,特别是互联网的普遍存在及广泛应用,服务外包得到蓬勃发展。

从美国到英国,从欧洲到亚洲,无论是中小企业还是跨国公司,都把自己有限的资源集中于公司的核心能力上而将其余业务交给外部专业公司,服务外包成为“发达经济中不断成长的现象”。

3>(引力模型(gravity model)答:丁伯根和波伊赫能的引力模型基本表达式为:其中,是国与国的贸易额,为常量,是国的国内生产总值,是国的国内生产总值,是两国的距离。

、、三个参数是用来拟合实际的经济数据。

引力模型方程式表明:其他条件不变的情况下,两国间的贸易规模与两国的GDP成正比,与两国间的距离成反比。

把整个世界贸易看成整体,可利用引力模型来预测任意两国之间的贸易规模。

另外,引力模型也可以用来明确国际贸易中的异常现象。

4>(第三世界(third world)答:第三世界这个名词原本是指法国大革命中的Third Estate(第三阶级)。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Chapter 31.Home has 1200 units of labor available. It can produce two goods, apples and bananas. The unit labor requirement in apple production is 3, while in banana production it is 2. a .Graph out the production possibilities frontier:b .What is the opportunity cost of apples in terms of bananas?5.1=LbLa a a c .In the absence of trade, what would the price of apples in terms of bananas be?In the absence of trade, since labor is the only factor of production and supply decisions aredetermined by the attempts of individuals to maximize their earnings in a competitive economy, only when Lb La b a /a a /P P =will both goods be produced. So 1.5 /P P b a =2.Home is as described in problem 1. There is now also another country, Foreign, with alabor force of 800. Foreign ’s unit labor requirement in apple production is 5, while in banana production it is 1.a .Graph Foreign ’s production possibilities frontier:b .Construct the world relative supply curve.Home's PPF 0200400600800200400600800Q apple Q banana Foreign's PPF0200400600800100080160240320400Q*apple Q*banana3.Now suppose world relative demand takes the following form: Demand for apples/demandfor bananas = price of bananas/price of apples.a .Graph the relative demand curve along with the relative supply curve:a b b a /P P /D D =∵When the market achieves its equilibrium, we have 1b a )(D D -**=++=ba b b a a P P Q Q Q Q ∴RD is a hyperbola xy 1=b .What is the equilibrium relative price of apples?The equilibrium relative price of apples is determined by the intersection of the RD and RScurves.RD: yx 1= RS: 5]5,5.1[5.1],5.0(5.0)5.0,0[=∈=⎪⎩⎪⎨⎧+∞∈=∈y y y x x x ∴25.0==y x∴2/=b P a P e ec .Describe the pattern of trade.∵b a b e a e b a P P P P P P ///>>**∴In this two-country world, Home will specialize in the apple production, export apples and import bananas. Foreign will specialize in the banana production, export bananas and import apples.d .Show that both Home and Foreign gain from trade.International trade allows Home and Foreign to consume anywhere within the coloredlines, which lie outside the countries ’ production possibility frontiers. And the indirect method, specializing in producing only one production then trade with other country, is a more efficient method than direct production. In the absence of trade, Home could gain three bananas by foregoing two apples, and Foreign could gain by one foregoing five bananas. Trade allows each country to trade two bananas for one apple. Home could then gain four bananas by foregoing two apples while Foreign could gain one apple by foregoing only two bananas. So both Home and Foreign gain from trade.4.Suppose that instead of 1200 workers, Home had 2400. Find the equilibrium relative price. What can you say about the efficiency of world production and the division of the gains from trade between Home and Foreign in this case?RD: yx 1= RS: 5]5,5.1[5.1],1(1)1,0[=∈=⎪⎩⎪⎨⎧+∞∈=∈y y y x x x ∴5.132==y x ∴5.1/=b P a P e eIn this case, Foreign will specialize in the banana production, export bananas and import apples. But Home will produce bananas and apples at the same time. And the opportunity cost of bananas in terms of apples for Home remains the same. So Home neither gains nor loses but Foreign gains from trade.5.Suppose that Home has 2400 workers, but they are only half as production in both industries as we have been assuming, Construct the world relative supply curve and determine the equilibrium relative price. How do the gains from trade compare with those in the case described in problem 4?In this case, the labor is doubled while the productivity of labor is halved, so the "effective labor"remains the same. So the answer is similar to that in 3. And both Home and Foreign can gain from trade. But Foreign gains lesser compare with that in the case 4.6.”Korean workers earn only $ an hour; if we allow Korea to export as much as it likes to the United States, our workers will be forced down to the same level. You can’t import a $5 shirt without importing the $ wage that goes with it.” Discuss.In fact, relative wage rate is determined by comparative productivity and the relative demand for goods. Korea’s low wage reflects the fact that Korea is less productive than the United States in most industries. Actually, trade with a less productive, low wage country can raise the welfare and standard of living of countries with high productivity, such as United States. Sothis pauper labor argument is wrong.7.Japanese labor productivity is roughly the same as that of the United States in the manufacturing sector (higher in some industries, lower in others), while the United States, is still considerably more productive in the service sector. But most services are non-traded. Some analysts have argued that this poses a problem for the United States, because our comparative advantage lies in things we cannot sell on world markets. What is wrong with this argument?The competitive advantage of any industry depends on both the relative productivities of the industries and the relative wages across industries. So there are four aspects should be taken into account before we reach conclusion: both the industries and service sectors of Japan and U.S., not just the two service sectors. So this statement does not bade on the reasonable logic. 8.Anyone who has visited Japan knows it is an incredibly expensive place; although Japanese workers earn about the same as their . counterparts, the purchasing power of their incomes is about one-third less. Extend your discussing from question 7 to explain this observation. (Hint: Think about wages and the implied prices of non-trade goods.) The relative higher purchasing power of U.S. is sustained and maintained by its considerably higher productivity in services. Because most of those services are non-traded, Japanese could not benefit from those lower service costs. And U.S. does not have to face a lower international price of services. So the purchasing power of Japanese is just one-third of their U.S. counterparts.9.How does the fact that many goods are non-traded affect the extent of possible gains from trade?Actually the gains from trade depended on the proportion of non-traded goods. The gains will increase as the proportion of non-traded goods decrease.10.We have focused on the case of trade involving only two countries. Suppose that there are many countries capable of producing two goods, and that each country has only one factor of production, labor. What could we say about the pattern of production and in this case? (Hint: Try constructing the world relative supply curve.)Any countries to the left of the intersection of the relative demand and relative supply curves export the good in which they have a comparative advantage relative to any country to the right of the intersection. If the intersection occurs in a horizontal portion then the country with that price ratio produces both goods.Chapter 41. In the United States where land is cheap, the ratio of land to labor used in cattle rising ishigher than that of land used in wheat growing. But in more crowded countries, where land is expensive and labor is cheap, it is common to raise cows by using less land and more labor than Americans use to grow wheat. Can we still say that raising cattle is land intensive compared with farming wheat? Why or why not?The definition of cattle growing as land intensive depends on the ratio of land to labor used inproduction, not on the ratio of land or labor to output. The ratio of land to labor in cattle exceeds the ratio in wheat in the United States, implying cattle is land intensive in the United States. Cattle is land intensive in other countries too if the ratio of land to labor in cattle production exceeds the ratio in wheat production in that country. The comparison between another country and the United States is less relevant for answering the question.2. Suppose that at current factor prices cloth is produced using 20 hours of labor for eachacre of land, and food is produced using only 5 hours of labor per acre of land.a. Suppose that the economy ’s total resources are 600 hours of labor and 60 acres ofland. Using a diagram determine the allocation of resources.5TF LF /TF LF /QF)(TF / /QF)(LF aTF / aLF 20TC LC /TC LC /QC)(TC / /QC)(LC aTC / aLC =⇒===⇒==We can solve this algebraically since L=LC+LF=600 and T=TC+TF=60. The solution is LC=400, TC=20, LF=200 and TF=40.b. Now suppose that the labor supply increase first to 800, then 1000, then 1200 hours. Using a diagram like Figure4-6, trace out the changing allocation of resources. Labor Land ClothFoodLCLF TCTFtion).specializa (complete 0.LF 0,TF 1200,LC 60,TC :1200L 66.67LF 13.33,TF 933.33,LC 46.67,TC :1000L 133.33LF 26.67,TF 666.67,LC 33.33,TC :800L ===============c. What would happen if the labor supply were to increase even further?At constant factor prices, some labor would be unused, so factor prices would have tochange, or there would be unemployment.3. “The world ’s poorest countries cannot find anything to export. There is no resource thatis abundant — certainly not capital or land, and in small poor nations not even labor is abundant.” Discuss.The gains from trade depend on comparative rather than absolute advantage. As to poor countries, what matters is not the absolute abundance of factors, but their relative abundance. Poor countries have an abundance of labor relative to capital when compared to more developed countries.4. The U.S. labor movement — which mostly represents blue-collar workers rather thanprofessionals and highly educated workers — has traditionally favored limits on imports form less-affluent countries. Is this a shortsighted policy of a rational one in view of the interests of union members? How does the answer depend on the model of trade?In the Ricardo ’s model, labor gains from trade through an increase in its purchasing power. This result does not support labor union demands for limits on imports from less affluent countries.In the Immobile Factors model labor may gain or lose from trade. Purchasing power in terms of one good will rise, but in terms of the other good it will decline.The Heckscher-Ohlin model directly discusses distribution by considering the effects of trade on the owners of factors of production. In the context of this model, unskilled U.S. labor loses from trade since this group represents the relatively scarce factors in this country. The results from the Heckscher-Ohlin model support labor union demands for import limits. 5. There is substantial inequality of wage levels between regions within the United States. Labor Land Cloth Food0l 800 0l 1000 0l 1200For example, wages of manufacturing workers in equivalent jobs are about 20 percent lower in the Southeast than they are in the Far West. Which of the explanations of failure of factor price equalization might account for this? How is this case different from the divergence of wages between the United States and Mexico (which is geographically closer to both the . Southeast and the Far West than the Southeast and Far West are to each other)?When we employ factor price equalization, we should pay attention to its conditions: both countries/regions produce both goods; both countries have the same technology of production, and the absence of barriers to trade. Inequality of wage levels between regions within the United States may caused by some or all of these reasons.Actually, the barriers to trade always exist in the real world due to transportation costs. And the trade between U.S. and Mexico, by contrast, is subject to legal limits; together with cultural differences that inhibit the flow of technology, this may explain why the difference in wage rates is so much larger.6.Explain why the Leontief paradox and the more recent Bowen, Leamer, andSveikauskas results reported in the text contradict the factor-proportions theory.The factor proportions theory states that countries export those goods whose production is intensive in factors with which they are abundantly endowed. One would expect the United States, which has a high capital/labor ratio relative to the rest of the world, to export capital-intensive goods if the Heckscher-Ohlin theory holds. Leontief found that the United States exported labor-intensive goods. Bowen, Leamer and Sveikauskas found that the correlation between factor endowment and trade patterns is weak for the world as a whole.The data do not support the predictions of the theory that countries' exports and imports reflect the relative endowments of factors.7.In the discussion of empirical results on the Heckscher-Ohlin model, we noted thatrecent work suggests that the efficiency of factors of production seems to differ internationally. Explain how this would affect the concept of factor price equalization.If the efficiency of the factors of production differs internationally, the lessons of the Heckscher-Ohlin theory would be applied to “effective factors” which adjust for the differences in technology or worker skills or land quality (for example). The adjusted model has been found to be more successful than the unadjusted model at explaining the pattern of trade between countries. Factor-price equalization concepts would apply to the effective factors. A worker with more skills or in a country with better technology could be considered to be equal to two workers in another country. Thus, the single person would be two effective units of labor. Thus, the one high-skilled worker could earn twice what lower skilled workers do and the price of one effective unit of labor would still be equalized.chapter 81. The import demand equation, MD, is found by subtracting the home supply equation from the home demand equation. This results in MD = 80 - 40 x P. Without trade, domestic prices and quantities adjust such that import demand is zero. Thus, the price in the absence of trade is2.2. a. Foreign's export supply curve, XS, is XS = -40 + 40 x P. In the absence of trade, the price is 1.b. When trade occurs export supply is equal to import demand, XS = MD. Thus, using theequations from problems 1 and 2a, P = , and the volume of trade is 20.3. a. The new MD curve is 80 - 40 x (P+t) where t is the specific tariff rate, equal to . (Note: in solving these problems you should be careful about whether a specific tariff or ad valorem tariff is imposed. With an ad valorem tariff, the MD equation would be expressed as MD =80-40 x (1+t)P). The equation for the export supply curve by the foreign country is unchanged. Solving, we find that the world price is $, and thus the internal price at home is $. The volume of trade has been reduced to 10, and the total demand for wheat at home has fallen to 65 (from the free trade level of70). The total demand for wheat in Foreign has gone up from 50 to 55.b. andc. The welfare of the home country is best studied using the combined numerical andgraphical solutions presented below in Figure 8-1. Home SupplyHome Demanda b c d e P T =1.7550556070QuantityPrice P W =1.50P T*=1.25where the areas in the figure are:a: 55 (55-50) .5(55-50) (65-55) .5(70-65) (65-55) surplus change: -(a+b+c+d)=. Producer surplus change: a=. Government revenue change: c+e=5. Efficiency losses b+d are exceeded by terms of trade gain e. [Note: in the calculations for the a, b, and d areas a figure of .5 shows up. This is because we are measuring the area of a triangle, which is one-half of the area of the rectangle defined by the product of the horizontal and vertical sides.]4. Using the same solution methodology as in problem 3, when the home country is very small relative to the foreign country, its effects on the terms of trade are expected to be much less. The small country is much more likely to be hurt by its imposition of a tariff. Indeed, this intuition is shown in this problem. The free trade equilibrium is now at the price $ and the trade volume is now $.With the imposition of a tariff of by Home, the new world price is $, the internal home price is $, home demand is units, home supply is and the volume of trade is . When Home is relatively small, the effect of a tariff on world price is smaller than when Home is relatively large. When Foreign and Home were closer in size, a tariff of .5 by home lowered world price by 25 percent, whereas in this case the same tariff lowers world price by about 5 percent. The internal Home price is now closer to the free trade price plus t than when Home was relatively large. In this case, the government revenues from the tariff equal , the consumer surplus loss is , and the producer surplus gain is . The distortionary losses associated with the tariff (areas b+d) sum to and the terms of trade gain (e) is . Clearly, in this small country example the distortionary losses from the tariff swamp the terms of trade gains. The general lesson is the smaller the economy,the larger the losses from a tariff since the terms of trade gains are smaller.5. The effective rate of protection takes into consideration the costs of imported intermediate goods. In this example, half of the cost of an aircraft represents components purchased from other countries. Without the subsidy the aircraft would cost $60 million. The European value added to the aircraft is $30 million. The subsidy cuts the cost of the value added to purchasers of the airplane to $20 million. Thus, the effective rate of protection is (30 - 20)/20 = 50%.6. We first use the foreign export supply and domestic import demand curves to determine the new world price. The foreign supply of exports curve, with a foreign subsidy of 50 percent per unit, becomes XS = -40 + 40(1+ x P. The equilibrium world price is and the internal foreign price is . The volume of trade is 32. The foreign demand and supply curves are used to determine the costs and benefits of the subsidy. Construct a diagram similar to that in the text and calculate the area of the various polygons. The government must provide - x 32 = units of output to support the subsidy. Foreign producers surplus rises due to the subsidy by the amount of units of output. Foreign consumers surplus falls due to the higher price by units of the good. Thus, the net loss to Foreign due to the subsidy is + - = units of output. Home consumers and producers face an internal price of as a result of the subsidy. Home consumers surplus rises by 70 x .3 + .5 (6= while Home producers surplus falls by 44 x .3 + .5(6 x .3) = , for a net gain of units of output.7. At a price of $10 per bag of peanuts, Acirema imports 200 bags of peanuts. A quota limiting the import of peanuts to 50 bags has the following effects:a. The price of peanuts rises to $20 per bag.b. The quota rents are ($20 - $10) x 50 = $500.c. The consumption distortion loss is .5 x 100 bags x $10 per bag = $500.d. The production distortion loss is .5 x50 bags x$10 per bag = $250.。