数理经济学ppt课件

数理经济学课件.docx

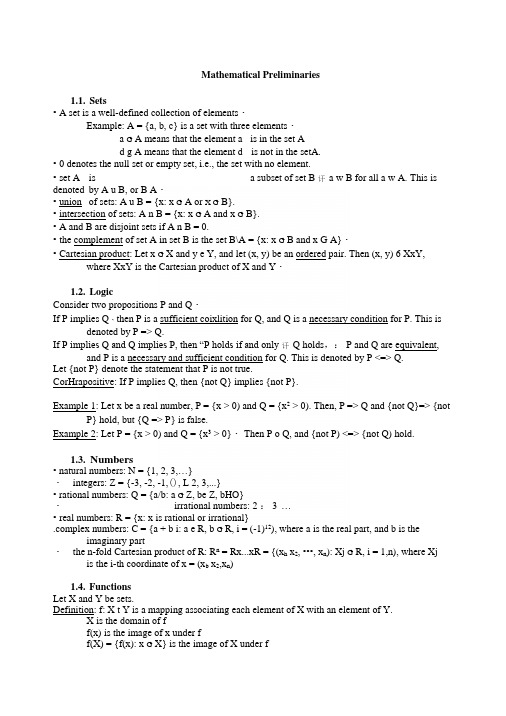

Mathematical Preliminaries1.1.Sets•A set is a well-defined collection of elements・Example: A = {a, b, c} is a set with three elements・a G A means that the element a is in the set Ad g A means that the element d is not in the setA.•0 denotes the null set or empty set, i.e., the set with no element.•set A is a subset of set B 讦a w B for all a w A. This is denoted by A u B, or B A・•union of sets: A u B = {x: x G A or X G B}.•intersection of sets: A n B = {x: x G A and x G B}.•A and B are disjoint sets if A n B = 0.•the complement of set A in set B is the set B\A = {x: x G B and x G A}・•Cartesian product: Let x G X and y e Y, and let (x, y) be an ordered pair. Then (x, y) 6 XxY, where XxY is the Cartesian product of X and Y・1.2.LogicConsider two propositions P and Q・If P implies Q、then P is a sufficient coixlition for Q, and Q is a necessary condition for P. This is denoted by P => Q.If P implies Q and Q implies P, then “P holds if and only 讦Q holds,: P and Q are equivalent, and P is a necessary and sufficient condition for Q. This is denoted by P <=> Q.Let {not P} denote the statement that P is not true.CorHrapositive: If P implies Q, then {not Q} implies {not P}.Example 1: Let x be a real number, P = {x > 0) and Q = {x2 > 0). Then, P => Q and {not Q}=> {not P} hold, but {Q => P} is false.Example 2: Let P = {x > 0) and Q = {x3 > 0}・ Then P o Q, and {not P) <=> {not Q) hold.1.3.Numbers•natural numbers: N = {1, 2, 3,…}・integers: Z = {-3, -2, -1,(), L 2, 3,...}•rational numbers: Q = {a/b: a G Z, be Z, bHO}・irrational numbers: 2 : 3 …•real numbers: R = {x: x is rational or irrational}.complex numbers: C = {a + b i: a e R, b G R, i = (-1)12), where a is the real part, and b is the imaginary part・the n-fold Cartesian product of R: R n = Rx...xR = {(x h x2, •••, x n): Xj G R, i = 1,n), where Xj is the i-th coordinate of x = (x b x2,x n)1.4.FunctionsLet X and Y be sets.Definition: f: X t Y is a mapping associating each element of X with an element of Y.X is the domain of ff(x) is the image of x under ff(X) = {f(x): x G X} is the image of X under f•a function: if only one point in Y is associated with each point in X・ a coirespondence: if more than one point in Y can be associated with each point in X •inverse function: x = f *(y) if and only if y = f(x).a function f: X T Y is onto 讦f(X) = Y.It means that the equation f(x) = y has at least one solution for each y.•if f(x) and f ly) are both single・valued, then f is on—to-one.It means that the equation f(x) = y has at most one solution for each y.•composite function: h = g(f(x)) = g • f is the composition of f with g satisfying f: A t B u C, g:C t D, g • f: A t D.L5e BoundsLet S c R.•S is bounded from above (from below)讦there exists a G R (b G R) such that x < a (x > b) for all x G S. Then, a is an upper bound of S, and b is a lower bound of S・•The least upper bound (lub) or suDremum (sup) of S is the upperbound of S such that there does not exist a smaller upper bound. It is denoted by sup(S).•The supremum of S is called a maximum (max) of S if sup(S) G S. It is denoted by max(S). •The greatest lower bound (gib) or infimum (inf) of S is the lower bound of S such that there does not exist a larger lower bound. 1( is denoted by inf(S).•The infimum of S is called a minimum (min) of S if inf(S) e S. It is denoted by min(S).• Property:If S c R and S has an upperbound, then S has a supremum.If S u R and S has a lowerbound, then S has an infimum.16 Vector SpaceConsider a set V.LI- associative law: x + (y + z) = (x + y) + z, for all x, y, z, w VL2- identity: there exists O G V such that x + 0 = x for all x G VL3- inverse: there exists (-x) e V such that x + (-x) = 0 for all x e VL4- commutative law: x + y = y + x for all x, y G VL5- associative law: a・([3・x) = (a-p) x for all a, p e R, and for all x G VL6- identity: there exists 1 G V such that l x = x for all x e VL7- distributive law: a・(x + y) = a x + a y for all ae R, and for all x, y w VL8- distributive law: (a + p)-x = a x + p x for all a,卩G R, and for all x G V L9- closure: x e V and y G V implies that (x + y) G V LIO- closure: x G V and ae R implies that (a・x) e V. Definition: A set V is vector space (or linear space) if it satisfies Ll-Ll0. Then x G V is called a vector. Examples: R l\ or C n is each a vector space.1.7. Norms and distancesConsider a function d(x, y) satisfying:M1: d(x, y) = 0 if and only if x = y M2: d(x, y) + d(y, z) > d(z, x) M3: d(x, y) > 0 for all x, y M4: d(x, y) = d(y, x).Definition: For a given set X,讦a function d: XxX —> R satisfies M1-M4, then: X is a metric space, denoted by (X, d)d is a metricd(x, y) is the distance between points x and y.Examples:di(x,y) = [Zi (xj - yi)2!12 = Euclidian distance,denoted by ||x - y||d2(x, y) = maxi 风-y s|d3(x, y) = Zi lx, - y.lNote: Topology consists in studying the properties of sets that are independent of the distance measure chosen.Definition: Let V be a vector space・ A real value function N: V t R is called a norm on V if: N(x) > 0 for all x G V N(x) = 0 if and only if x = 0N(r x) = |r| N(x) for all re R and x e V, andN(x + y) < N(x) + N(y) for all x, y G V.Example: N(x) = d|(x, 0) = [Xi (xj)2]12 = ||x|| is the Euclidian noim of x in R.R n, with Euclidian norm and Euclidian metric, is a normed vector space.Every normed vector space is a metric space with respect to the induced metric defined by d](x, y) = llx - yll.Convex SetsLet X be a vector space (e.g・,X = R n).Definition: A set S c: X is convex if any x, y G S implies that(0x + (1-0) y) e S, for all 0 e R, 0 < 0 < 1.Note: (0 x + (1-0) y) is called a linear combination of x and y.Properties:・Any intersection of convex sets is convex.•Let Si, i = 1,m, be convex sets in vector space X. Then:•(Ejei (Xj Si) = {x: x = Z i=i■•…m oti Xi, XjG Sj, otf R, i = 1,…,Hi} is a convexset.•(SixS2x...xS m) = x i=1■•…m (Si) is a convex set.L9. Compact SetsLet S u R n.Definition: An open ball about x0 e R n with radius r e R, r > 0, is defined as:B r(x0) = {x: x G S, d(x, x0) < r}, where d(x, x0) is the Euclidian distance betweenpoints x and x0.Definition: An open set S u R n is a set S such that, for each x e S, there exists an open ball B r(x) completely contained in S.• The union of open sets is open..A finite intersection of open sets is open.Definition: The inierior of a set S, denoted by int(S), is the union of all open sets contained in S..A set S is open 讦and only 讦S 二int(S).Definition: A set S c R n is closed 讦the set (R n\S) is open.・The intersection of closed sets is closed・.A finite union of closed sets is closed・Definition: The closure of a set S, denoted by cl(S), is the intersection of all closed sets containing S..A set S is closed if and only if S = cl(S).Definition: The boundary of a set S u R" is the set cl(S)ncl(R n/S).Definition: A set S is bounded if there exists an open ball with a finite radius which contains S・Definition: A collection of open sets (S a)a€A in a metric space X is said to be an open cover of a given set S u R n if S u 低入 S a.The open cover (S a)ae A of S is said to admit a finite subcover if there exists a finitesubcollection (SQ^F such that S u S®Definition 1: A set S c R n is compact if and only if it is closed and bounded・Definition 2: A subset S of a metric space X is compact if and only if every open cover of S has a finite subcover.Note: The definition 2 of compactness applies to sets in any metric space, while definition 1 applies only to sets in R n.LIO. SequencesLet (X, d) be a metric space (e.g., X = R n), and let S c X.Definition: A sequence {xj: j = 1,g} in S converges to y if, for any e > 0, there exists a positive integer j" such that j hj,implies d(y, xj) < e.This is denoted by y = limj* {xj, where y is the limit of {Xj}.Note: It does not follow that y = lirOjT® {xj} G S・Definition: A sequenee {Xj: j = 1,…,g} in S is a Cauchy sequence if for any e > 0, there exists a positive integer such that, for any ij > j\ d(x i9 Xj) < £.Definition: If every Cauchy sequence in a metric space is also a convergent sequence, then the* A sequence {xp j = 1,…严} in R" is a Cauchy sequence if and only if it is a convergent sequence, i.e. if and only if there is y G R n such that linij》{Xj} —> y.metric space is said to be complete.By the above definition, this implies that R n is complete (although not all metric spaces are complete)・Definition: Let m(j) be an increasing function: m: {12 3,…} T {1, 2, 3,such that m(k+l) > m(k).Given a sequence {xj: j = 1, 2,…,g}, {m = 1,…,g} is a subsequence of {xj: j =1,2,…,oo}..A set S c R n is closed if and only if every convergent sequenee of points in S converges to a point in S・・ A set S e R n is compact if and only if every sequence in S has a convergent subsequence whoselimit is in S.・ A sequence {xj: j = 1, 2,…,g} in R n converges to y if and only if every subsequence of {xj: j =1,…,g} converges to y.・Every bounded sequence contains a convergent subsequence・Definition: A sequence {xj: j = 1,2,…,oo} is (strictly) increasing if, for all m > n, x m > (>) x n for all n.A sequence {xj: j = 1,2,…,<»} is (strictly) decreasing if, for all m > n, x m < (<) x n forall n・Let X u R, X H 0. If X is bounded from above (below), there exists an increasing (decreasing) sequence in X converging to sup(X) (inf(X)).Definition: Assume that ±oo are allowed as limits of a sequence.The lim sup of the sequence {xj: j = 1,in R is defined as limj^oo {可:j =1,2 •••}, where aj = sup{xj, Xj+b Xj+2. ...}・ It is denoted by linij^oo supk>j x k, or simply by lim SUpjTco Xj・The lim inf of the sequence {Xj: j = 1,in R is defined as limj^ {bj: j = 1,2 …}, where bj = inf{x jt Xj+i, x i+2, ...}. It is denoted by inf k>j x k, or simply by lim infj†Xj・† A sequence xj in R converges to a limit y G R if and only if y = lim supj* Xj = lim in与* Xj.。

数理经济学课件

>0 i=1,2…n 图(a) 图(a <0 i=1,2…n 图(b) 图(b 图(c) 图(c

⑶追求享受品种多样化假设:

U ( x1 , x2 )

图(d 图(d)

得到的都是向下弯曲 的截线,故效用函数的整 个曲面是向下弯曲的,数 学上称为凹函数,重要任 务就是寻找一种简洁的凹 函数作为效用函数的数学 表达式。

k (σ −1)⋅δ

σ ⋅( δ −1)

<k

(σ −1) (σ −1)

倍,符合效用函数凹的假设,实际中常用δ=σ, 倍,符合效用函数凹的假设,实际中常用δ=σ,因其推导出的需求 函数表达式一致。 故, 其中:

U ( x1 ⋯ xn ) = A[α1 x1

σ

1

σ

+ ⋯ + α n xn

σ

1

σ

σ

]

(σ −1)

数理经济学

——理论与应用 ——理论与应用

(研究生用)

说

• • • • • •

明

1、课堂学时:40,课外与课堂学习比例为3︰1 2、教 材: 数理经济学——理论与应用 清华大学出版社,张金水著 。 3、参 考 书: (1) 可计算非线性动态投入产出模型,清华大学出版社,张金水著 。 (2) 一般均衡理论,上海财经出版社,罗斯·M.斯塔尔著。 (3) 数理经济学导论,中国统计出版社,伍超标著 (4)数理经济分析入门,中国科学技术大学出版社,候定丕。 (5)价值理论及数理经济学的20篇论文,首都经济贸易大学出版社,吉 拉德·德布鲁著。

2.1 生产过程中投入量与产出量之间定量关系;生产函数的数 生产过程中投入量与产出量之间定量关系; 学表达式

数理经济学 课件

《数理经济学》课件

数学符号在数理经济学中具有特定的意义,它们代表了经济变量、参数和函数等。理解这些符号的意义 是理解数理经济学理论的关键。

数学模型与方程

01

模型构建

数理经济学家使用数学模型来描述经济系统。这些模型通常由一组方程

式构成,用来表示不同经济变量之间的关系。

02

方程类型

在数理经济学中,常见的方程类型包括线性方程、非线性方程、微分方

数理经济学的发展历程

总结词

数理经济学的发展历程可以追溯到19世纪,其发展经 历了多个阶段,包括古典数理经济学、新古典数理经 济学和现代数理经济学等。

详细描述

数理经济学的发展历程可以追溯到19世纪,当时一些 经济学家开始尝试运用数学方法来描述和预测经济现 象。古典数理经济学阶段主要关注生产、分配和交换 等经济活动的均衡问题。新古典数理经济学阶段则强 调个体行为和市场均衡的研究,并引入了边际分析和 效用函数等概念。现代数理经济学则更加注重数学模 型的复杂性和精确性,并广泛应用于宏观和微观经济 学等领域。

在数理经济学中,证明方法多种多样 ,包括直接证明、反证法、归纳法和 演绎法等。这些方法用于证明经济定 理和推导经济关系,确保经济理论的 严谨性和准确性。

在数理经济学中,必须遵循一定的推 理原则,如公理化原则、一致性原则 和完备性原则等。这些原则确保了经 济理论的逻辑严密性和科学性。

03

数理经济学的应用

宏观经济学中的应用

经济增长与经济发展

数理经济学在研究经济增长、经济发展等方面发挥了重要作用,通 过建立数学模型来解释国家或地区的经济增长和发展趋势。

财政政策与货币政策

利用数理经济学方法分析财政政策和货币政策的效果,为政府制定 经济政策提供科学依据。

数理经济学 chapter1 课件

.Chapter1Basic Probability Theory•A random experiment is a process that generates well-defined outcomes. One and only one of the possible experimental outcomes will occur,but there is uncertainty associated with which one will occur.•Fundamental axioms of modern econometrics:–An economic system can be viewed as a random experiment governed by some probability distribution or probability law.–Any economic phenomena(often in form of data)can be viewed as an outcome of this random experiment.•Two essential elements of a random experiment:–The set of all possible outcomes—sample space.–The likelihood with which each outcome will occur—probability func-tion.•Definition:Sample Space.The possible outcomes of the random experiment are called basic outcomes,and the set of all basic outcomes is called the sample space,denoted by S.When an experiment is performed, the realization of the experiment is one outcome in the sample space.•Examples:Finite Sample Space.Experiment Sample SpaceToss a coin{Head,Tail}Roll a die{1,2,3,4,5,6}Play a football game{Win,Lose,Tie}•Example:Infinite Discrete Sample Space.Consider the number of accidents that occur at a given intersection within a month.The sample space is the set of all nonnegative integers{0,1,2,···}.•Example:Continuous Sample Space.When recording the lifetime of a light bulb,the outcome is the time until the bulb burns out.Therefore the sample space is the set of all nonnegative real number{t:t∈R,t≥0}.•Definition:Event.An event A is a subset of basic outcomes from the sample space S.The event A is said to occur if the random experiment gives rise to one of the constituent basic outcomes in A.That is,an event occurs if any of its basic outcomes has occurred.•Example:A die is rolled.Event A is defined as“number resulting is even”. Event B is”number resulting is4”.Then A={2,4,6}and B={4}.•Remarks:–The words”set”and”event”are interchangeable.–Basic outcome∈sample space,event⊂sample space.•Definition:Containment.The event A is contained in the event B, or B contains A,if every sample point of A is also a sample point of B. Whenever this is true,we will write A⊂B,or equivalently,B⊃A.•Definition:Equality.Two events A and B are said to be equal,A=B, if A⊂B and B⊂A.•Definition:Empty Set.The set containing no elements is called the empty set and is denoted by∅.The event corresponding to∅is called a null(impossible)event.•Definition:Complement.The complement of A,denoted by A c,is the set of basic outcomes of a random experiment belonging to S but not to A.•Definition:Union.The union of A and B,A∪B,is the set of all basic outcomes in S that belong to either A or B.The union of A and B occurs if and only if either A or B(or both)occurs.•Definition:Intersection.The intersection of A and B,denoted by A∩B or AB,is the set of basic outcomes in S that belong to both A and B.The intersection occurs if and only if both events A and B occur.Venn Diagram:Use circles(or other shapes)to denote sets(events).The inte-rior of the circle represents the elements of the set,while the exterior represents elements which are not in the set.Figure1:Venn Diagrams:(a)Complement,(b)Union,and(c)Intersection•Definition:Difference.The difference of A and B,denoted by A\B or A−B,is the set of basic outcomes in S that belong to A but not to B, i.e.A\B=A∩B c.The symmetric difference,A÷B,contains basic outcomes that belong to A or to B,but not to both of them.Figure2:Venn Diagrams:Symmetric Difference.1.3Review of Set Theory•Definition:Exclusiveness.If A and B have no common basic out-comes,they are called mutually exclusive(or disjoint).Their intersection is empty set,i.e.,A∩B=∅.•Definition:Collectively Exhaustive.Suppose A1,A2,···,A n are n events in the sample space S,where n is any positive integer.If∪n i=1A i=S, then these n events are said to be collectively exhaustive.•Definition:Partition.A class of events H={A1,A2,···,A n}formsa partition of the sample space S if these events satisfy(1)A i∩A j=∅for all i=j(mutually exclusive).(2)A1∪A2∪···∪A n=S(collectively exhaustive).Laws of Set Operations•Complementation(A c)c=A,∅C=S •CommutativityA∪B=B∪A,A∩B=B∩A.•AssociativityA∪(B∪C)=(A∪B)∪C,A∩(B∩C)=(A∩B)∩C.•Distributivity:A∩(B∪C)=(A∩B)∪(A∩C),A∪(B∩C)=(A∪B)∩(A∪C). More Generally,for n≥1,B∩(∪n i=1A i)=∪n i=1(B∩A i),B∪(∩n i=1A i)=∩n i=1(B∪A i).•De Morgan’s Laws:(A∪B)c=A c∩B c,(A∩B)c=A c∪B c. More Generally,for n≥1,(∪n i=1A i)c=∩n i=1(A c i),(∩n i=1A i)c=∪n i=1(A c i).Use Venn diagrams to check De Morgan’s Laws for the case of two events(A∪B)c=A c∩B c.Figure3:Validation of(A∪B)c=A c∩B c.Left panel:(A∪B)c;right panel:A c∩B c.•How to prove the general case of De Morgan’s Laws(n>2)(∪n i=1A i)c=∩n i=1(A c i).•Proof.x∈(∪n i=1A i)c⇔x/∈A i for any i=1,···,n⇔x∈A c i for all i=1,···,n⇔x∈∩n i=1(A c i).Hence,the equality holds.•Definition:Probability Function.Suppose a random experiment has a sample space S .The probability function P maps an event to a real number between 0and 1.It satisfies the following properties:(1)0≤P (A )≤1for any event A in B .(2)P (S )=1.(3)Countable Additivity :If countable number of events A 1,A 2,···∈B are mutually exclusive (pairwise disjoint),then P (∪∞i =1A i )=∑∞i =1P (A i ).•Definition:Countable Set.A set S is called countable if the set can be put into1-1correspondence with a subset of the natural numbers.•Remarks:–We can use a(finite or infinite)sequence to list all elements in a countable set.–Finite sets are countable.–The set of natural numbers,the set of integers,and the set of rational numbers are countable sets.–The set of all real numbers in interval(a,b),b>a,is uncountable.Properties of Probability Function:•P (Φ)=0.•P (A c )=1−P (A ).•If C 1,C 2,···are mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive,thenP (A )=∞∑i =1P (A ∩C i ).•If A ⊂B ,P (A )≤P (B ).•Subadditivity :For events A i ,i =1,2,···,P (∪∞i =1A i )=∞∑i =1P (A i \∪i −1j =1A j )≤∞∑i =1P (A i ).•Theorem:For any n events A1,···,A n,P(∪n i=1A i)=∑i P(A i)−∑i1<i2P(A i1A i2)+∑i1<i2<i3P(A i1A i2A i3)+···+(−1)n+1P(A1A2···A n).•Proof by induction.–When n=2,the theorem is true.–Assume for n=k events,the theorem is true.–For n=k+1events,we haveP(∪k+1i=1A i)=P(A k+1)+P(∪k i=1A i)−P(∪k i=1(A i A k+1)).Apply the formula of n=k events to P(∪k i=1A i)and P(∪k i=1(A i A k+1)), we obtain the formula for n=k+1events.1.5Methods of Counting•For the so-called classical or logical interpretation of probability,we will assume that the sample space S contains afinite number N of outcomes and all of these outcomes are equally probable.•For every event A,P(A)=number of outcomes in AN.•How to determine the number of total outcomes in the space S and in various events in S?1.5Methods of Counting•We consider two important counting methods:permutation and combi-nation.•Fundamental Theorem of Counting.If a random experiment con-sists of k separate tasks,the i-th of which can be done in n i ways,i=1,···,k,then the entire job can be done in n1×n2×···×n k ways.•Example:Permutation.Suppose we will choose two letters from fourletters{A,B,C,D}in different orders,with each letter being used at mostonce each time.How many possible orders could we obtain?There are12ways:{AB,BA,AC,CA,AD,DA,BC,CB,BD,DB,CD,DC}.The word“ordered”means that AB and BA are distinct outcomes.Permutations•Problem:Suppose that there are k boxes arranged in row and there are n objects,where k≤n.We are going to choose k from the n objects tofill in the k boxes.How many possible different ordered sequences could you obtain?–First,one object is selected tofill in box1,there are n ways.–A second object is selected from the remaining n−1objects.Therefore, there are n−1ways tofill box2.–..–The last box(box k),there are n−(k−1)ways tofill it.•The total number of different ways tofill box1,2,···,k isn(n−1)···(n−(k−1))=n! (n−k)!.•The experiment is equal to selecting k objects out of the n objectsfirst, then arrange the selected k objects in a sequence.•Each different arrangement of the sequence is called a permutation.•The number of permutations of choosing k out of n,denoted by P k n,isP k n=n! (n−k)!.•Convention:0!=1.•Example:The Birthday Problem.What is the probability that at least two people in a group of k people(2<k≤365)will have the same birthday?–Let S={(x1,x2,···,x k)},x i represents the birthday of person i.How many outcomes in S?365k.–How many ways the k people can have different birthdays?P k365.–The probability that all k people will have different birthday is P k365/365k.–The probability that at least two people will have the same birthday is p=1−P k365/365k.–k=10,p=0.1169482;k=20,p=0.4114384,k=30,p=0.7063162, k=40,p=0.8912318,k=50,p=0.9703736;k=60,p=0.9941227.Combinations•Choosing a subset of k elements from a set of n distinct elements.•The order of the elements is irrelevant.For example,the subsets{a,b}and {b,a}are identical.•Each subset is called a combination.•The number of combinations of choosing k out of n is denoted by C k n.We haveC k n=the number of choosing k out of n with ordering the number of ordering k elements=P k n/k!=n!/k!(n−k)!.•Example:Combination.Suppose we will choose two letters from four letters{A,B,C,D}.Each letter is used at most once in each arrangement but now we are not concerned with their ordering.How many possible pairs could we have?There are six pairs:{A,B},{A,C},{A,D},{B,C},{B,D},{C,D}.•Example:A class contains15boys and30girls,and10students are to be selected at random for a special assignment.What is the probability that exactly3boys will be selected?–The number of combinations of10students out of45students is C1045.–The number of combinations of3boys out of15boys is C315.–The number of combinations of7girls out of30girls is C730.–Thus,p=C315C730/C1045.•C k n is also denoted by (nk).This is also called a binomial coefficientbecause of its appearance in the binomial theorem(x+y)n=n∑k=0(nk)x k y n−k.•Properties of the binomial coefficients–∑nk=0C k n=2n,∑nk=0(−1)k C k n=0.–∑ik=0C k n C i−kn=C i2n.–C k n+C k−1n=C k n+1.•Example:The Matching Problem.A person types n letters,types the corresponding addresses on n envelopes,and then places the n letters in the n envelopes in a random manner.What is the probability p n that at least one letter will be placed in the correct envelope?•ANS:–Let A i be the event that letter i,i=1,···,n,is placed in the correct envelope.We need to determine the value of P(∪n i=1A i).–Use formulaP(∪n i=1A i)=∑i P(A i)−∑i1<i2P(A i1A i2)+∑i1<i2<i3P(A i1A i2A i3)+···+(−1)n+1P(A1A2···A n).–∑i1<···<i kP(A i1···A ik)=C k n×(n−k)!/n!=1/k!.–P(∪n i=1A i)=1−12!+13!−···+(−1)n+11n!=n∑i=1(−1)i+11i!=−[n∑i=0(−1)i1i!−1]≈1−e−1≈0.632.1.6Conditional Probability•Different economic events are generally related to each other.Because of the connection,the occurrence of event B may affect or contain the information about the probability that event A will occur.•Example:Financial Contagion.A large drop of the price in one market can cause a large drop of the price in another market,given the speculations and reactions of market participants.•Definition:Conditional Probability.Let A and B be two events in(S,B,P).Then the conditional probability of event A given event B, denoted as P(A|B),is defined asP(A|B)=P(A∩B) P(B)provide that P(B)>0.•Properties of Conditional Probability:–P(A)=P(A|S).–P(A|B)=1−P(A c|B).–Multiplication RulesP(A∩B)=P(B)P(A|B)=P(A)P(B|A).•Example:Suppose two balls are to be selected,without replacement,from a box containing r red balls and b blue balls.What is the probability that thefirst is red and the second is blue?ANS:Let A={thefirst ball is red},B={the second ball is blue}.ThenP(A∩B)=P(A)P(B|A)=rr+b·br+b−1.•Theorem:Chain Rule.For any events A1,A2,···,A n,we haveP(A1A2···A n)=P(A1)P(A2|A1)P(A3|A1A2)···P(A n|A1···A n−1) provided P(A1···A n−1)>0.•Remark–P(A1···A n−1)>0implies P(A1)>0,P(A1A2)>0,···.•Theorem:Rule of Total Probability.Let{A i,i=1,2,···}be a partition(i.e.,mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive)of S,P(A i)> 0for i≥1.For any event B in S,P(B)=∞∑i=1P(B|A i)P(A i).•Example:Suppose B1,B2,and B3are mutually exclusive.If P(B i)=1/3 and P(A|B i)=i/6for i=1,2,3.What is P(A)?(Hint:B1,B2,B3are also collectively exhaustive.)•Bayes’Theorem:P(B|A)=P(A|B)P(B)P(A).•Remarks:–We consider P(B)as the prior probability about the event B.–P(B|A)is posterior probability given that A has occurred.•Alternative Statement of Bayes’Theorem:Suppose E1,···,E n are n mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive events in the sample space S.ThenP(E i|A)=P(A|E i)P(E i)P(A)=P(A|E i)P(E i)∑ni=1P(A|E i)P(E i).•Example:Auto-insurance Suppose an insurance company has three types of customers:high risk,medium risk and low risk.From the com-pany’s consumer database,it is known that25%of its customers are high risk,25%are medium risk,and50%are low risk.Also,the database shows that the probability that a customer has at least one accident in the current year is0.25for high risk,0.16for medium risk,and0.10for low risk.What is the probability that a new customer is high risk,given that he has had one accident during the current year?•ANS:Let H,M,L are the events that the customer is a high risk,medium risk or low risk customer.Let A be the event that the customer has had one accident during the current year.ThenP(H|A)=P(A|H)P(H)P(A|H)P(H)+P(A|M)P(M)+P(A|L)P(L).Given P(H)=0.25,P(M)=0.25,P(L)=0.50,P(A|H)=0.25, P(A|M)=0.16,P(A|L)=0.10,we haveP(H|A)=0.410.•Example:In a certain group of people the ratio of the number of men to the number of women is r.It is known that the incidence of color blindness among men is p,and the incidence of color blindness among women is p2. Suppose that the person that we randomly selected is color blind,what is the probability that the person is a man?•ANS:Let M and W denote the events“man selected”and“woman se-lected”,and D be the event“the selected person is color blind”.ThenP(M|D)=P(D|M)P(M)P(D|M)P(M)+P(D|W)P(W)=pr1+rpr1+r+p21+r=rr+p.•Example:In a TV game there are three curtains A,B,and C,of which two hide nothing while behind the third there is a Big Prize.The Big Prize is won if it is guessed correctly which curtain hides it.You choose one of the curtains,say A.Before curtain A is pulled to reveal what is behind it,the game host pulls one of the two other curtains,say B, and shows that there is nothing behind it.He then offers you the option to change your decision(from curtain A to curtain C).Should you stick to your original choice or change to C?•ANS:Let A,B,and C be the events“Big Prize is behind curtain A”(respectively,B and C).We can assume P(A)=P(B)=P(C)=1/3. Let B∗be the event“host shows that there is nothing behind curtain B”. ThenP(A|B∗)=P(B∗|A)P(A)P(B∗|A)P(A)+P(B∗|B)P(B)+P(B∗|C)P(C).–If the prize is behind curtain A,the host randomly pulls curtain B or curtain C,so P(B∗|A)=1/2.–If the prize is behind curtain B,P(B∗|B)=0.–If the prize is behind curtain C,P(B∗|C)=1.Therefore,P(A|B∗)=12×1312×13+0×13+1×13=1/3.Similarly,P(C|B∗)=2/3.•If two events A and B are unrelated.Then we expect that the information of B is irrelevant to predicting P(A).In other words,we expect that P(A|B)=P(A).•Definition:Independence.Two events A and B are said to be statis-tically independent if P(A∩B)=P(A)P(B).•Remarks:–By this definition,P(A|B)=P(A∩B)/P(B)=P(A)P(B)/P(B)=P(A).Similarly,we have P(B|A)=P(B).Therefore,the knowledge of B does not help in predicting A.–If P(A)=0,then any event B is independent of A.•Example:Random Walk Hypothesis(Fama1970).If a stock market is fully efficient,then the stock price P t will follow a random walk; that is,P t=P t−1+X t,where the stock price change{X t=P t−P t−1}is independent across different periods.•Example:Geometric Random Walk Hypothesis.The stock price {P t}is called a geometric random walk if X t=ln P t−ln P t−1is independent across different time periods.Note that X t≈P t−P t−1approximates theP t−1relative stock price change.•Example:Suppose two events A and B are mutually exclusive.If P(A)> 0and P(B)>0,can A and B be independent?•ANS:A and B are not independent becauseP(A∩B)=0=P(A)P(B).•Theorem:Let A and B be two independent events.Then(a)A and B c;(b)A c and B;(c)A c and B c are all independent.•Proof.(a)P(AB c)=P(A)−P(AB)=P(A)−P(A)P(B)=P(A)[1−P(B)]=P(A)P(B c),A andB c are independent.•Remark:Intuitively,A and B c should be independent.Because if not, we would be able to predict B c from A,and thus predict B.•Definition:Independence Among Several Events.Events A1,···,A nare(jointly)independent if,for every possible collection of events A i1,···,A iK,where K=2,···,n and i1<i2<···<i K∈{1,2,···,n},P(A i1∩···∩A iK)=P(A i1)···P(A iK).•Remark:We need to verify2n−1−n conditions.For example,three events A,B,and C are independent ifP(A∩B)=P(A)P(B),P(A∩C)=P(A)P(C),P(B∩C)=P(B)P(C),P(A∩B∩C)=P(A)P(B)P(C).•Remark:It is possible tofind that three events are mutually(pairwise) independent but not jointly independent.It is also possible tofind three events A,B,C that satisfy P(A∩B∩C)=P(A)P(B)P(C)but not independent.•Example:SupposeS={a,b,c,d}and each basic outcome is equally likely to occur.Let A1={a,b},A2= {b,c},and A3={a,c}.Then we haveP(A1)=P(A2)=P(A3)=12,P(A1A2)=P(A1A3)=P(A2A3)=14,butP(A1A2A3)=0=1 8 .•Example:Suppose S={a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h}and each basic outcome is equally likely to occur.Let A1={a,b,c,d},A2={a,b,c,d},and A3={a,e,f,g}.ThenP(A1)=P(A2)=P(A3)=1 2 ,P(A1A2A3)=1 8 ,butP(A1A2)=1/2=P(A1)P(A2).•Theorem:If the events A1,A2,···,A n are independent,the same is true for events B1,B2,···,B n,where for each i,the event B i stands for either A i or its complement A c i.•Theorem:If the events A1,A2,···,A n are independent,thenP(A1∪···∪A n)=1−{[1−P(A1)]···[1−P(A n)]}.•Example:Consider experiments1,2,···,n such that in each of them an event D may or not occur.Let P(D)=p for every experiment,and let A k be the event“D occurs at the k-th experiment”.•ANS:A1∪···∪A n is the event“D occurs at least once in the n experi-ments”.ThenP(A1∪···∪A n)=1−{[1−P(A1)]···[1−P(A n)]}=1−(1−p)n.。

数理经济学-数理经济学本083jok-PPT精品文档

A

1

21

练习4:利润率=1时,求供给函数及要素需求函数。

L bp Y w

p r w 要素 需求函数 L/Y

1 1

1 A

22

练习4:利润率=1时,求供给函数及要素需求函数。

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 p a r b w A

练习:请写出生产函数表达式

27

N1原材料面粉消耗 N2原材料调料消耗 K固定资本 生 产 函 数 Q产出数量

生 产 L 函 数

V增加值

28

N1原材料面粉消耗 N2原材料调料消耗 K固定资本 生 产 函 数 Q产出数量

生 产 L 函 数

V增加值

N 1 N 2 Q min , ,V 1 b 2 b

数理经济学丶课间休息

1

第3 讲

第2章:生产函数与供给函数 及要素需求函数

2

了解生产函数与供给 函数及要素需求函 数在实际中的应用

3

r

利润最大决策

K

生 产 函 数 Y

w

Max Y s.t rK+wL=C

L

C

4

练习1:

写出生产函数的数学表 达式并画出等产量线。

5

练习1:写出生产函数的数学表达式

Max S.t

Y Y (K, L) r K w L C

Y 1 Y 1 K r L w

13

练习3:边际利润率=利润率?

Max Y Y(K, L) S.t r K wL C Y p Y p pY ? K r L w C

1 1

A A

1

1 1

数理金融 课件

PV

C1 1 r

C2

1 r 2

Cn

1 r n

2.1.4 年金

1.普通年金的终值

2.年金的现值

3.永续年金

2021/10/10

17

2.2债券及其期限结构

▪ 2.2.1债券的定义和要素

▪ 1.面值

▪ 2.期限

▪ 3.附息债券与票面利率

▪ 4.付息频率

▪ 5.分期偿还特征

▪ 6附加选择权

▪ 2.2.2债券的风险

2021/10/10

19

2.3 债券定价

▪ 2.3.1债券定价的原则 ▪ 2.3.2影响债券定价的因素 ▪ 债券的面值P; ▪ 债券的票面利息c; ▪ 债券的有效期T; ▪ 是否可提前赎回; ▪ 是否可转换; ▪ 流通性; ▪ 违约的可能性; ▪ 影响债券定价的外部因素有: ▪ 基准利率(即无风险利率); ▪ 市场利率; ▪ 通货膨胀率;

Ni P0 X i Ni P0 X i

1.6.2 单期不确定性无套利定价模型

, N n )T 满足

定理 1.6 资本市场不存在套利机会当且仅当存在 Rl

使

PT v 或ZT 1

2成 021立/1。 0/1这 0 里 PT 和 ZT 分别为矩阵 P 和 Z 的转置矩阵。

13

1.7 单期不确定性均衡定价模型

(2) P ~ Q 当且仅当U (x) U ( y)

(3) 设 P , Q B~ , 0,1 ,则U (P (1 )Q) U (P) (1 )U (Q)

1.2.4 von Nenmann-Morgenstren 效用函数

1.2.5 伯瑞特(Pratt)率

给定 von Neumann and Morgenstern 效用函数V X ,定义 Pratt 率 Ah : R R

数理经济学讲义

• “现代数理经济学不但是一门应用数学的经济科学, 而且很有点‘数学物理方法’的味道,在其学术著 作中,人们几乎

• 杨小凯:“在瓦尔拉斯那个时代,应用高等数学的 经济学叫数理经济学,以示与自然语言进行分析的 经济学之区别。但在我们这个时代,经济学几乎已 全部数学化,国际经济学术界中,完全用自然语言 讨论经济问题的文献已经很少了。当代没有不应用 数学的物理学,从这个意义上我们可以说,今天不 应用数学的‘经济学’也算不上经济学了。今天的 经济学就是上个世纪人们称为数理经济学的东西。 广义的数理经济学就是‘高级经济分析’。它与初 级经济分析和中级经济分析的区别在于更系统地运 用高等数学来阐述经济理论。而初级、中级经济分 析主要是用几何图形浅显(但不严格)地解释这些 用高等数学推出的理论。”

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

主讲 :刘照德 博士 副教授 QQ: 912804610 Email:lzhaode@

广东财经大学经济贸易学院 2013.9.2

1

本课程简介及基本要求

➢ 1.本课程的开设背景及教学计划 ➢ 2.基本要求

➢ 每人需要有一本教材,可以复印或打印 ➢ 认真听课,自学相关基础知识 ➢ 上课不许接听电话; ➢ 随机点名,不得无故旷课,有事需请假 ➢ 上课可以随时提问问题 ➢ 课下邮件或QQ群内讨论 ➢ 按时交作业

10

§1.2 数理经济学的产生与发展

数理经济学在它的历史进程中经历了3个重 要阶段:

➢边际分析阶段 ➢集论与线性分析阶段 ➢汇合阶段

11

§1.2 数理经济学的产生与发展

➢边际分析阶段(1838一1947) 1838年到1947年,是经济学向数学借用武

器的历史发展阶段,借用的基本工具:微 积分,尤其是偏导数、全微分和拉格朗日 乘数法。 边际分析法是这一时期产生的一种经济分 析方法,同时形成了边际效用学派,代表 人物有walras,Jevollss,Gossen,Menger, Edgeworth,Marshall,Fisher,Clark等人。

均衡的稳定性理论、资源最优配置、一般交易论

13

§1.2 数理经济学的产生与发展

➢集论与线性分析阶段(1948一1960) 1838年到1947年,是经济学向数学借用武

器的历史发展阶段,借用的基本工具:微 积分,尤其是偏导数、全微分和拉格朗日 乘数法。 边际分析法是这一时期产生的一种经济分 析方法,同时形成了边际效用学派,代表 人物有walras,Jevollss,Gossen,Menger, Edgeworth,Marshall,Fisher,Clark等人。

14

§1.2 数理经济学的产生与发展

➢集论与线性分析阶段(1948一1960) 集论方法主要工具:数学分析、凸分析和

拓扑学 线性分析主要工具:线性代数和线性规划 此时,数理经济学在研究内容上几乎就等

于一般经济均衡理论,研究成果表现为以 下两个方面:一般经济均衡的严格理论体 系和线性经济模型

15

§1.2 数理经济学的产生与发展

➢ 汇合阶段(1961一) 这阶段主要成果有:

经济学中的不确定性与信息 大范围经济分析 经济学中的对偶性 总需求理论 经济连续统 社会选择理论 经济增长理论 税收优化理论 组织理论 无限维经济学 不完全资产市场均衡论

16

§1.3 数理经济学与其他学科的关系

17

§1.3 数理经济学与其他学科的关系

2

如何学习数理经济学 ——分享三句话

• “学东西要从简单的学起。” ——芝加哥的统计学家刁锦寰

• “复杂的事情简单做,简单的事情反复做。” ——无名氏

• “学会宏观经济学教科书的内容我用了一年, 但真正了解这些内容背后的约束条件我用了8 年。”

——BLANCHARD

2020/3/25

3

第一章 导论

8

§1.1 数理经济学的定义

➢可见,数理经济学是数学方法(或者其它自 然科学方法)在经济学原理方面的应用,应 用的目的是用数学语言来表达、推理和论 证经济学原理。数理经济学是从一些经济 假设出发,用抽象的数学方法,建立经济 机理的数学模型。

9

§1.2 数理经济学的产生与发展

• 数理经济学的真正诞生,是19世纪中叶的 事情。1983年,诺贝尔经济学奖得主 GDebreu在他的获奖演讲中说:“如果要对数 理经济学的诞生选择一个象征性的日子, 我们这一行会以罕见的一致意见选定1838 年,……Coumot是作为第一个阐明经济现象 的数学模型的缔造者而著称于世 的。”Coumot的贡献,是他在《财富理论 的数学原理研究》中第一次以数学方式阐 明了经济现象的理论模型。

§1.1 数理经济学的定义 §1.2 数理经济学的产生与发展 §1.3 数理经济学与其他学科的关系 §1.4 几个重要概念

4

§1.1 数理经济学的定义

• 1.数理经济学是“西方资产阶级经济学在理 论研究中运用数学方法进行陈述和推理的 一个分支科学——中国大百科全书—经济学

卷

• 2.数理经济学是“包括数学理论和方法在经 济理论中的各种应用”——数理经济学手册

12

§1.2 数理经济学的产生与发展

➢ 边际分析阶段(1838一1947) 边际分析阶段,数理经济学在研究内容上几乎全是

微观经济学,其成就可概括为3个方面: ✓ 形成和发展了一套完整的微观经济活动者行为理论; ✓ 提出了一般经济均衡的理论框架; ✓ 创立了当今的消费者理论、生产者理论、垄断竞争

理论及一般经济均衡理论的数学基础。 主要理论有:厂商理论、消费理论、一般均衡理论、

• 5. “数理经济学是主要进行定性分析的理 论经济学,它研究最优经济效果、利益协 调和最优价格的确定这些经济学基本理论 问题,为经济计量学、管理科学、经济控 制论提供模型框架、结构和基础理论,它 实在是经济学的基础之基础。”--杨小凯 《数理经济学基础》

7

§1.1 数理经济学的定义

• 杨小凯:“在瓦尔拉斯那个时代,应用高等数学的 经济学叫数理经济学,以示与自然语言进行分析的 经济学之区别。但在我们这个时代,经济学几乎已 全部数学化,国际经济学术界中,完全用自然语言 讨论经济问题的文献已经很少了。当代没有不应用 数学的物理学,从这个意义上我们可以说,今天不 应用数学的‘经济学’也算不上经济学了。今天的 经济学就是上个世纪人们称为数理经济学的东西。 广义的数理经济学就是‘高级经济分析’。它与初 级经济分析和中级经济分析的区别在于更系统地运 用高等数学来阐述经济理论。而初级、中级经济分 析主要是用几何图形浅显(但不严格)地解释这些 用高等数学推出的理论。”

5

§1.1、数理经济学的定义

• 3.以数学为经济分析方法论基础的经济学, 叫做数理经济学。 ——武康平,1996

• 4.数理经济学“仅是一种经济分析的方法, 是经济学家利用数学符号描述经济问题, 运用已知数学定理进行推理的一种方 法”——数理经济学的基本方法,[美]蒋中 一,1999

6

§1.1 数理经济学的定义