劳动经济学》 作者borjas 习题答案

劳动经济学(Borjas

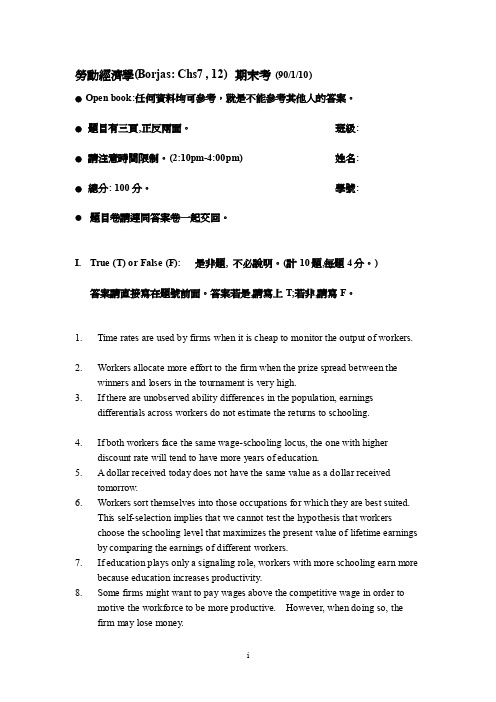

勞動經濟學(Borjas: Chs7 , 12) 期末考(90/1/10)●Open book:任何資料均可參考,就是不能參考其他人的答案。

●題目有三頁,正反兩面。

班級:●請注意時間限制。

(2:10pm-4:00pm) 姓名:●總分: 100分。

學號:●題目卷請連同答案卷一起交回。

I. True (T) or False (F): 是非題, 不必說明。

(計10題,每題4分。

)答案請直接寫在題號前面。

答案若是,請寫上T;若非,請寫F。

1.Time rates are used by firms when it is cheap to monitor the output of workers.2.Workers allocate more effort to the firm when the prize spread between thewinners and losers in the tournament is very high.3.If there are unobserved ability differences in the population, earningsdifferentials across workers do not estimate the returns to schooling.4.If both workers face the same wage-schooling locus, the one with higherdiscount rate will tend to have more years of education.5. A dollar received today does not have the same value as a dollar receivedtomorrow.6.Workers sort themselves into those occupations for which they are best suited.This self-selection implies that we cannot test the hypothesis that workerschoose the schooling level that maximizes the present value of lifetime earnings by comparing the earnings of different workers.7.If education plays only a signaling role, workers with more schooling earn morebecause education increases productivity.8.Some firms might want to pay wages above the competitive wage in order tomotive the workforce to be more productive. However, when doing so, thefirm may lose money.9.The theory of efficiency wage is the solid explanation for inter-industrial wagedifferentials.10. A delayed compensation contract explains the existence of mandatory retirementin the labor market.II.計算題(共兩題,計30分,請寫明計算過程,答案請直接寫在試題下面空白處)1.Suppose that Carl’s wage schooling locus is given by: (Total: 12 points)(1)Derive the marginal rate of return schedule and fill in the blanks in thetable. (9 points)For the rates of return of s=10 and s=13, please show your calculation inthe following: (Y ou don’t have to do this for other years of schooling.)(2)When will Carl quit school if his discount rate is 8 percent? (3 points)2.Mr. Chang (張先生) has just graduated from college. He will live for twomore periods, and he is considering two alternative education-work options.He can start working right away, earning $1000 in period 1, $1100 in period2. He can also go to graduate school and in period 1, spending $300 in thatperiod. After he gets his master degree, he will earn $2500 in period 2.The rate of discount is 10%. (Total: 18 points) 接下頁(1), (2)(1)To maximize his lifetime earnings, what should Mr. Chang do?(10 points)(2) Please calculate the rate of return for Mr. Chang to go to the graduateschool. Is it financially rational for him to get his master degree?(8 points)III.申論題(Essay Questions):請由4題中選2題作答。

《劳动经济学》(作者Borjas)第十三章习题答案

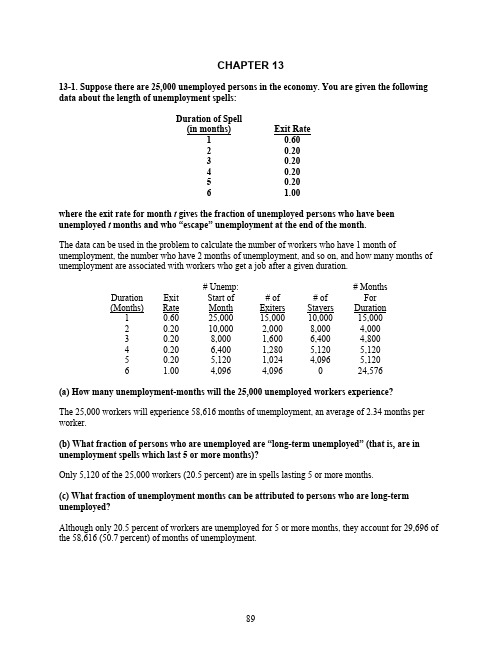

CHAPTER 1313-1. Suppose there are 25,000 unemployed persons in the economy. You are given the following data about the length of unemployment spells:Duration of Spell(in months) ExitRate1 0.602 0.203 0.204 0.205 0.206 1.00where the exit rate for month t gives the fraction of unemployed persons who have been unemployed t months and who “escape” unemployment at the end of the month.The data can be used in the problem to calculate the number of workers who have 1 month of unemployment, the number who have 2 months of unemployment, and so on, and how many months of unemployment are associated with workers who get a job after a given duration.Duration (Months) ExitRate# Unemp:Start ofMonth# ofExiters# ofStayers# MonthsForDuration1 0.60 25,000 15,00010,000 15,0002 0.20 10,000 2,000 8,000 4,0003 0.20 8,000 1,600 6,400 4,8004 0.20 6,400 1,280 5,120 5,1205 0.20 5,120 1,024 4,096 5,1206 1.00 4,096 4,096 0 24,576(a) How many unemployment-months will the 25,000 unemployed workers experience?The 25,000 workers will experience 58,616 months of unemployment, an average of 2.34 months per worker.(b) What fraction of persons who are unemployed are “long-term unemployed” (that is, are in unemployment spells which last 5 or more months)?Only 5,120 of the 25,000 workers (20.5 percent) are in spells lasting 5 or more months.(c) What fraction of unemployment months can be attributed to persons who are long-term unemployed?Although only 20.5 percent of workers are unemployed for 5 or more months, they account for 29,696 of the 58,616 (50.7 percent) of months of unemployment.(d) What is the nature of the unemployment problem in this example: too many workers losing their jobs or too many long spells?Most spells are short-lived, but workers in long spells account for most of the unemployment observed in this economy. Thus, the main problem is too many long spells.13-2. Consider Table 599 of the 2002 U.S. Statistical Abstract.(a) How many workers aged 20 or older were unemployed in the United States during 2001? How many of these were unemployed less than 5 weeks, 5 to 14 weeks, 15 to 26 weeks, and 27 or more weeks?In total, 5,554,000 workers aged 20 years or older were unemployed in the U.S. in 2001. Of these, 40 percent, or 2,221,600 workers, were unemployed for less than 5 weeks; 32.2 percent, or 1,788,388 workers, were unemployed between 5 and 14 weeks; 15.5 percent, or 860,870 workers, were unemployed15 to 26 weeks, and 12.9 percent, or 716,466 workers were unemployed for 27 or more weeks.(b) Assume that the average spell of unemployment is 2.5 weeks for anyone unemployed for less than 5 weeks. Similarly, assume the average spell is 10 weeks, 20 weeks, and 35 weeks for the remaining categories. How many weeks did the average unemployed worker remain unemployed? What percent of total months of unemployment are attributable to the workers that remained unemployed for at least 15 weeks?The total number of weeks of unemployment is calculated as:2,221,600(2.5) + 1,788,388(10) + 860,870(20) + 716,466(35) = 65,731,590months of unemployment spread over 5,554,000 unemployed workers, implies that the average unemployed worker remained unemployed for 11.835 weeks. The percent of total months of unemployment attributable to the workers that remained unemployed for at least 15 weeks is[ 860,870(20) + 716,466(35) ] / 65,731,590 = 64.34 percent.13-3. Suppose the marginal revenue from search isMR = 50 - 1.5w,where w is the wage offer at hand. The marginal cost of search isMC = 5 + w.(a) Why is the marginal revenue from search a negative function of the wage offer at hand?If the offer-at-hand is relatively low, it pays to keep on searching as the next offer is likely higher than the offer-at-hand. If the offer-at-hand is very high, however, it does not pay to keep on searching since it is unlikely that the next search will generate a higher wage offer.(b) Can you give an economic interpretation of the intercept in the marginal cost equation; in other words, what does it mean to say that the intercept equals $5? Similarly, what does it mean to say that the slope in the marginal cost equation equals one dollar?The $5 indicates the out-of-pocket search costs. Even if the offer-at-hand is zero (so that there is no opportunity cost to search), it still costs money to get to the firm and learn about the details of the potential job offer. The slope equals $1, because the costs of search also vary directly with the opportunity cost of search which is the wage offer at hand. If the wage offer at hand is $10, the opportunity cost from one more search equal $10; if the wage offer at hand is $11, the opportunity cost would be $11, and so on.(c) What is the worker’s asking wage? Will a worker accept a job offer of $15?The asking wage is obtained by equating the marginal revenue of search to the marginal cost of search, or 50 – 1.5w = 5 + w. Solving for w implies that the asking wage is $18. The worker, therefore, would not accept a job offer of $15.(d) Suppose UI benefits are reduced, causing the marginal cost of search to increase to MC = 20 + w. What is the new asking wage? Will the worker accept a job offer of $15?If we equate the new marginal cost equation to the marginal revenue equation we find that the asking wage drops to $12. The worker will now accept a wage offer of $15.13-4. (a) How does the exclusion of non-working welfare recipients affect the calculation of the unemployment rate? Use the 2002 U.S. Statistical Abstract to estimate what the 2000 unemployment rate would have been if welfare recipients had been included in the calculation.Excluding non-working welfare recipients from the unemployment rate biases the unemployment rate downward. Table 560 of the Statistical Abstract shows that the labor force in 2000 totaled 140,863,000, while the number employed totaled 135,208,000. Thus, the unemployment rate was 4.0 percent.Table 513 of the Statistical Abstract shows that 2,253,000 people received public assistance in 2000. Assuming all of these were non-working and out of the labor force, their inclusion in the calculation of the unemployment rate would increase the unemployment rate to(140,863,000 + 2,253,000 – 135,208,000) / (140,863,000 + 2,253,000) = 5.5%.(b) How does the exclusion of black market workers affect the calculation of the unemployment rate? Estimate, the best you can, what the 2000 unemployment rate would have been if workers in the underground economy had been included in the calculation.Excluding black market workers from the calculation of the unemployment rate keeps the unemployment rate artificially high. At the best, black market workers are not counted in the labor force, but at the worst, the black market workers claim to be in the labor force and without a job. The problem is that there is no (or very little) data on the black market by definition. Some researchers have estimated the underground economy to be on the order of 10 to 20 percent of activity in the U.S. Suppose half of underground economy workers have regular market jobs as well. Suppose further that of the remaining half, one half claim to be unemployed while the other half is out of the labor force. Thus, 10 percent of the unemployed workers are the number of underground economy workers in the labor force without a job: 10 percent of(140,863,000 – 135,208,000) = 565,500. An equal number say they are not in the labor force. (And twice this number is already reporting having a legitimate job.) Using these estimates, therefore, the labor force should be 140,863,000 + 565,500 = 141,428,500, while the number employed should be 135,208,000 + 565,500 + 565,500 = 136,339,000. Thus, the unemployment rate would be(141,428,500 – 136,339,000) / 141,428,500 = 3.6%.13-5. Compare two unemployed workers; the first is 25 years old and the second is 55 years old. Both workers have similar skills and face the same wage offer distribution. Suppose that both workers also incur similar search costs. Which worker will have a higher asking wage? Why? Can search theory explain why the unemployment rate of young workers differs from that of older workers?The marginal revenue of search depends on the length of the payoff period. Younger workers have the most to gain from obtaining higher paying jobs, since they can then collect the returns from their search investment over a longer expected work-life. As a result, it pays for younger workers to set their asking wage at a relatively high level. This implies that younger workers will tend to have higher unemployment rates and longer spells of unemployment than older workers.13-6. Suppose the government proposes to increase the level of UI benefits for unemployed workers.A particular industry is now paying efficiency wages to its workers in order to discourage them from shirking. What is the effect of the proposed legislation on the wage and on the unemployment rate for workers in that industry?The introduction of UI benefits shifts the no-shirking supply curve upwards (from NS to NS′), because a higher wage would have to be paid in order to attract the same number of workers who do not shirk. As a result, the new equilibrium (point Q′) entails a higher efficiency wage and leads to a larger number of unemployed workers.Dploym ent13-7. It is well known that more-educated workers are less likely to be unemployed and haveshorter unemployment spells than less-educated workers. Which theory(ies), the job search model, the sectoral shifts hypothesis, or the efficiency wage model, can explain this empirical correlation?Two of the theories in question can be formulated in such a way that they each predict that more-educated workers will have less unemployment and shorter spells of unemployment than less-educated workers.The job search model suggests that highly educated workers would have a lower unemployment rate either if they have relatively higher search costs or relatively lower gains from search. It could then be argued, for example, that search costs are (relatively) higher for highly-educated workers than for less-educated workers, perhaps because the nature of the job match between a highly educated worker and a firm is much more complex than the type of job match required between the firm and a worker who does repetitive tasks.Similarly, it is plausible to argue that it is easier to retool a highly-educated worker than a less-educated worker. The decline in demand in particular industries, then, leads to sectoral shift that can be better weathered by highly-educated workers.The efficiency wage model, however, has a harder time explaining the correlation. Presumably, the output of highly-educated workers is more difficult to measure than the output of less-educated workers. As a result, efficiency wages are more likely to arise in industries that employ highly-educated workers, and these industries (which pay above-market wages) would have to maintain a pool of unemployed workers in order to keep the employed workers in line.13-8. Suppose a country has 100 million inhabitants. The population can be divided into the employed, the unemployed, and the persons who are out of the labor force (OLF). In any given year, the transition probabilities among the various categories are given by:Moving Into:Employed Unemployed OLFEmployed 0.94 0.02 0.04 Unemployed 0.20 0.65 0.15 Moving From: OLF 0.05 0.03 0.92These transition probabilities are interpreted as follows. In any given year, 2 percent of the workers who are employed become unemployed; 20 percent of the workers who are unemployed find jobs, and so on. What will be the steady-state unemployment rate?Use E for the number of employed people, U for the number of unemployed, and N for the number not participating. The flows of people among the three categories can be found by multiplying these numbers with respective probabilities in the table. In the steady-state, the flows into each category must exactly balance the outflows. This produces the following equations:Employed: E = .94E + .20U + .05NUnemployed: U = .02E + .65U + .03NOLF: N = .04E + .15U + .92NOnly two of the three equations can be used, however, as E + U + N = 100 million. The steady-state solutions for E, U, and N can now be found with brute force algebra. The solution is that 54.273 million are employed, 6.466 million are unemployed, and 39.261 million are not in the labor force. The steady-state unemployment rate is then%646.10739.60466.6100100=×=×+=E U U u .13-9. Consider an economy with 250,000 adults, of which, 40,000 are retired senior citizens, 20,000 are college students, 120,000 are employed, 8,000 are looking for work, and 62,000 stay at home. What is the labor force participation rate? What is the unemployment rate?The labor force participation rate = ( 120,000 + 8,000 ) / 250,000 = 51.2 percent.The unemployment rate = 8,000 / ( 120,000 + 8,000 ) = 6.25 percent.13-10. Consider an economy with 3 types of jobs. The table below shows the jobs, the frequency with which vacancies open up on a yearly basis, and the income associated with each job. Searching for a job costs $C per year and generates at most 1 job offer. There is a 20 percent chance of not generating any offer in a year. (Note: the expected search duration for a job with probability p of appearing is 1/p years.)Job Type Frequency IncomeA 30 percent $60,000B 20 percent $100,000C 30 percent $80,000As a function of C , specify the optimal job search strategy if the worker maximizes her expected income net of search costs.There are four possible strategies for the worker: accept any job paying at least $100,000, accept any job paying at least $80,000, accept any job paying at least $60,000, or do not search for a job.Under the first strategy, the worker will only accept a B job. The expected search time for a B job is 5 years. Thus, the expected value of this strategy is $100,000 – 5C .Under the second strategy, the worker will accept a B or a C job. The expected search time, therefore, is 2 years (i.e., there is a 50 percent chance of receiving a B or a C job in a year, so the search time is 1/0.5 =2). Thus, the expected value of this strategy isC C 2000,88$2)000,80($3.02.03.0)000,100($3.02.02.0−=−+++.Under the third strategy, the worker will accept any of the three jobs. The expected search time, therefore, is 1.25 years, and the expected value of this strategy isC C 25.1500,77$25.1)000,60($8.03.0)000,80($8.03.0)000,100($8.02.0−=−++.Under the fourth strategy, the worker does not search, and therefore does not find a job or incur search costs, for an expected payoff of $0.One can now compare the four expected payoffs to determine that the optimal search strategy is:Accept the first B job if C < $4,000.Accept the first B or C job if $4,000 # C < $14,000.Accept the first job of any kind if $14,000 # C < $62,000.Don’t search if $62,000 # C .13-11. (a) A country is debating whether to fund a national database of job openings and giving all unemployed workers free access to it. What effect would this plan have on the long-rununemployment rate? What effect would this plan have on the average duration of unemployment? Why?Lower search costs would probably increase the unemployment rate. Lower search costs (similar to extended UI benefits) will cause workers to keep their asking wage higher for a longer time. Thus, unemployed workers will be more selective in the jobs they accept. The result is that workers remain unemployed for longer periods of time. It is also possible that lower search costs will entice workers to quit their jobs in order to look for a better job. This will also increase the unemployment rate.(b) A country is debating whether to impose a $10,000 tax on employers for every worker they lay-off. What effect would this plan have on the long-run unemployment rate? What effect would this plan have on the average duration of unemployment?This policy would cause firms, in the long-run, to be very cautious in hiring new workers. (This cautious behavior is evident in Japan and some countries in Europe. The UI system in the US may also cause firms to be a bit cautious in hiring new workers.) Thus, the unemployed will remain unemployed for longer durations. The effect on the unemployment rate is a little ambiguous. The unemployment rate wouldlikely increase in the long-run, but one could also argue that the end result will be less labor turnover and, therefore, a lower rate of unemployment, especially if unemployed workers under the proposed rules are more easily discouraged and exit the labor force all together.。

劳动经济学鲍哈斯第七版第三章答案

劳动经济学鲍哈斯第七版第三章答案1、已达到预定可使用状态但未办理竣工决算的固定资产,应根据()作暂估价值转入固定资产,待竣工决算后再作调整。

[单选题] *A.市场价格B.计划成本C.估计价值(正确答案)D.实际成本2、A企业2014年12月购入一项固定资产,原价为600万元,采用年限平均法计提折旧,使用寿命为10年,预计净残值为零,2018年1月该企业对该项固定资产的某一主要部件进行更换,发生支出合计400万元,符合固定资产确认条件,被更换的部件的原价为300万元。

则对该项固定资产进行更换后的原价为( )万元。

[单选题] *A.210B.1 000C.820D.610(正确答案)3、由投资者投资转入的无形资产,应按合同或协议约定的价值,借记“无形资产”科目,按其在注册资本所占的份额,贷记“实收资本”科目,按其差额记入()科目。

[单选题] *A.“资本公积—资本溢价”(正确答案)B.“营业外收入”C.“资本公积—其它资本公积”D.“营业外支出”4、企业收取包装物押金及其他各种暂收款项时,应贷记()科目。

[单选题] *A.营业外收入B.其他业务收入C.其他应付款(正确答案)D.其他应收款5、2018年3月,A 公司提出一项新专利技术的设想,经研究,认为研制成功的可能性很大,于2018年4月开始研制。

2019年3月研制成功,取得了专利权。

研究阶段共发生支出500万元,开发阶段发生相关支出1 000万元,其中包含满足无形资产确认条件的支出为800万元。

企业该项专利权的入账价值为( ) 万元。

[单选题] *A.1 500B.800(正确答案)C.1 000D.5006、根据准则的规定,企业收到与日常活动无关的政府补助应当计入()科目。

[单选题] *A.投资收益B.其他业务收入C.主营业务收入D.营业外收入(正确答案)7、.(年浙江省高职考)下列项目中,不属于企业会计核算对象的经济活动是()[单选题] *A购买设备B请购原材料(正确答案)C接受捐赠D利润分配8、企业开出的商业汇票为银行承兑汇票,其无力支付票款时,应将应付票据的票面金额转作()。

现代劳动经济学课后【伊兰伯格】课后习题答案

INSTRUCTOR'S MANUALto accompanyEhrenberg & SmithModern Labor Economics:Theory & Public PolicyEighth EditionRobert S. SmithCornell UniversityRobert M. WhaplesWake Forest UniversityLawrence WohlGustavus Adolphus UniversityCopyright 2003 Addison-Wesley, Inc.All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except testing materials and transparency masters may be copied for classroom use. For information, address Addison-Wesley Higher Education, Pearson PLC 75 Arlington Street, Suite 300, Boston, Massachusetts 02116.A NOTE TO THE INSTRUCTORThis Instructor's Manual is intended to summarize the content of the eighth edition of Modern Labor Economics: Theory and Public Policy in a way that explains our pedagogical strategy. Summarized briefly, we believe that labor economics can be best learned if students are (1) able to see the "big picture" early on, so that new concepts can be placed in perspective; (2) moved carefully from concepts they already know to new ones; (3) motivated by seeing the policy implications or inherently interesting insights generated by the concepts being taught. To this last end, we discuss policy issues in every chapter and, in addition, employ "boxed examples" to demonstrate in historical, cross-cultural, or applied managerial settings the power of the concepts introduced.The text is designed to be accessible to students with limited backgrounds in economics. We do employ graphic analyses and equations as learning aids in various chapters; however, we are careful to precede their use with verbal explanations of the analyses and to introduce these aids in a step-by-step fashion. To help students in the application of concepts to various issues, we have printed answers to the odd-numbered review questions for each chapter at the back of the book.We have also endeavored to put together a text that, while accessible to all, is a comprehensive and up-to-date survey of modern labor economics. There are 9 chapter appendices designed to be used with more advanced students in generating additional insights.In the first part of this Instructor's Manual, we present a brief overview and the general plan of Modern Labor Economics. We then present a chapter-by-chapter review of the concepts presented in the text. In the discussion of each chapter we list the major concepts or understandings covered, and in some cases suggest topics or sections that could be eliminated if time must be conserved. We also present our answers to the even-numbered review questions at the end of each chapter.An important part of this Instructor's Manual are the suggested essay questions related to each chapter. We present a few suggested essay questions for each chapter.Table of ContentsClick on the chapter title to jump directly to that page.Overview of the Text 1 Chapter 1 Introduction 4 Chapter 2 Overview of the Labor Market8 Chapter 3 The Demand for Labor14 Chapter 4 Labor Demand Elasticities20 Chapter 5 Quasi-Fixed Labor Costs and Their Effects on Demand26 Chapter 6 Supply of Labor to the Economy: The Decision to Work32 Chapter 7 Labor Supply: Household Production, the Family, and the Life Cycle37 Chapter 8 Compensating Wage Differentials and Labor Markets45 Chapter 9 Investments in Human Capital: Education and Training51 Chapter 10 Worker Mobility: Migration, Immigration, and Turnover57 Chapter 11 Pay and Productivity62 Chapter 12 Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in the Labor Market68 Chapter 13 Unions and the Labor Market77 Chapter 14 Inequality in Earnings84 Chapter 15 Unemployment88OVERVIEW OF THE TEXTINTRODUCTION/REVIEW: Chapters 1 and 2Chapter 1 - IntroductionAppendix 1A - Statistical Testing of Labor Market Hypotheses Chapter 2 - Overview of the Labor MarketChapters 1 and 2 introduce basic concepts of labor economics. They are written to be accessible to students without backgrounds in intermediate theory, and can, therefore, be used as building blocks when a professor must "begin at the beginning." If the course is being taught to economics majors with intermediate microeconomics as a prerequisite, these chapters may be skipped or skimmed quickly as a review.An appendix to Chapter 1 introduces the student to econometrics. The purpose of this appendix is to present enough of the basic econometric concepts and issues to permit students to read papers employing ordinary least squares regression techniques. We strongly recommend assigning Appendix 1A in courses requiring students to read empirical papers in the field. We also recommend (in footnote 3 of the appendix) an introductory econometrics text that could be assigned by instructors who wish to go beyond our introductory treatment.THE DEMAND FOR LABOR: Chapters 3-5Chapter 3 - The Demand for LaborAppendix 3A - Graphic Derivation of a Firm's Labor Demand Curve Chapter 4 - Labor Demand ElasticitiesAppendix 4A - International Trade and the Demand for Labor: Can High-Wage Countries Compete?Chapter 5 - Quasi-Fixed Labor Costs and Their Effects on DemandThe demand for labor is discussed first primarily because we believe that the supply of labor is a more complex topic in many ways. Before analyzing the labor/leisure choice and household production, we first introduce students to the employer side of the market. For instructors who desire to cover topics concerned with the decision to work first, however, we note that Chapters 6 and 7, which deals with that decision, are self-contained. Therefore, nothing would be lost if Chapters 6 and 7 were taught ahead of Chapters 3, 4, and 5.In Chapter 3 the principal question analyzed is why demand curves slope downward. In Chapter 4 we move to a discussion of the elasticity of demand, and analyze the determinants of the precise relationship between wages and employment. The concepts are used to analyze how technological change and foreign trade affect labor demand. Finally, Chapter 5 analyzes the quasi-fixed nature of many labor costs and the ways these costs affect the demand for labor.SUPPLY OF LABOR TO THE ECONOMY: Chapters 6 and 7Chapter 6 - Supply of Labor to the Economy: The Decision to WorkChapter 7 - Labor Supply: Household Production, the Family, and the Life Cycle Chapters 6 and 7 analyze the decision of an individual to work for pay. The traditional analysis of the labor/leisure choice is given in Chapter 6, while in Chapter 7 the decision to work for pay is placed in the context of household production. The essential features of the decision to work for pay are included in Chapter 6. In one-quarter courses or courses in which time is scarce, Chapter 7 could be skipped; however, doing so would eliminate analyses of family labor supply decisions as well as labor supply decisions in the context of the life cycle.As noted above, Chapters 6 and 7 are designed to be self-contained for the convenience of instructors who wish to teach labor supply ahead of labor demand.FACTORS AFFECTING THE CHOICE OF EMPLOYMENT: Chapters 8-10 Chapter 8 - Compensating Wage Differentials and Labor MarketsAppendix 8A - Compensating Wage Differentials and Layoffs Chapter 9 - Investments in Human Capital: Education and TrainingAppendix 9A - A "Cobweb” Model of Labor Market AdjustmentAppendix 9B - A Hedonic Model of Earnings and Educational Level Chapter 10 - Worker Mobility: Migration, Immigration, and TurnoverOnce they have decided to seek employment, prospective workers encounter important choices concerning their occupation and industry, as well as the general location of their employment. Chapters 8 through 10 analyze these choices, with Chapters 8 and 9 focusing on industry/occupational choice and Chapter 10 on the choice of a specific employer and the location of employment. More particularly, Chapter 8 presents an analysis of job choice within the context of jobs that differ along nonpecuniary dimensions. Chapters 9 and 10 analyze issues affecting worker investments in skill acquisition (Chapter 9) and job change (Chapter 10), and both employ the concepts of human capital theory. All three chapters contain appendices of interest to instructors who wish to teach more advanced material.ANALYSES OF SPECIAL TOPICS IN LABOR ECONOMICS: Chapters 11-15 Chapter 11 - Pay and ProductivityChapter 12 - Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in the Labor MarketAppendix 12A - Estimating "Comparable Worth" Earnings Gaps: AnApplication of Regression AnalysisChapter 13 - Unions and the Labor MarketAppendix 13A - Arbitration and the Bargaining Contract ZoneChapter 14 - Inequality in EarningsAppendix 14A - Lorenz Curves and Gini CoefficientsChapter 15 - UnemploymentHaving presented basic concepts and analytical tools necessary to understand the demand and supply sides of the labor market, we now move to analyses of special topics: compensation, discrimination, unions, inequality, and unemployment. A complete analysis of all these topics requires an understanding of behavior on both the demand and supply sides of the market, and these chapters are built upon the preceding ten. No new analytical tools are introduced in these chapters.The chapters on unionism (Chapter 13) and discrimination (Chapter 12) deal with issues typically covered in labor economics courses, but they are more comprehensive than most other texts. It should be noted that the appendix to Chapter 12 includes an application of regression analysis. The chapter on inequality is unique and can be skipped without a loss in coverage of conventional material; however, it is written in a way that provides a review of material in previous chapters.CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTIONBecause the textbook stresses economic analysis as it applies to the labor market, students must understand the ways economic analyses are used. The basic purpose of Chapter 1 is to introduce students to the two major modes of economic analysis: positive and normative. Because both modes of analysis rest on some very fundamental assumptions, Chapter 1 discusses the bases of each mode in some detail.In our treatment of positive economics, the concept of rationality is defined and discussed, as is the underlying concept of scarcity. There is, in addition, a lengthy discussion of what an economic model is, and an example of the behavioral predictions flowing from such a model is presented. The discussion of normative economics emphasizes its philosophical underpinnings and includes a discussion of the conditions under which a market would fail to produce results consistent with the normative criteria. Labor market examples of governmental remedies are provided.The appendix to Chapter 1 introduces the student to ordinary least squares regression analysis. It begins with univariate analysis, introduced in a graphical context, explaining the concepts of dependent and independent variables, the "intercept" and "slope" parameters, the "error term," and the t statistic. The analysis then moves to multivariate analysis and the problem of omitted variables.List of Major Concepts1. The essential features of a market include the facilitation of contact between buyersand sellers, the exchange of information, and the execution of contracts.2. The uniqueness of labor services affects the characteristics of the labor market.3. Positive economics is the study of economic behavior, and underlying this theory ofbehavior are the basic assumptions of scarcity and rationality.4. Normative economics is the study of what "should be," and theories of socialoptimality are based in part on the underlying philosophical principle of "mutualbenefit. "5. A market "fails" when it does not permit all mutually beneficial trades to take place,and there are three common reasons for such failure.6. A governmental policy is "Pareto-improving" if it encourages additional mutuallybeneficial transactions. At times, though, the goal of improving Pareto efficiency conflicts with one of generating more equity.7. The concept that governmental intervention in a market may be justified on groundsother than the principle of mutual benefit is discussed (for example, governmentintervention may be justified on the grounds that income redistribution is a desirable social objective).8. (Appendix) The relationship between two economic variables (e.g., wages and quitrates) can be plotted graphically; this visual relationship can also be summarized algebraically.9. (Appendix) A way to summarize a linear relationship between two variables isthrough ordinary least squares regression analysis -- a procedure that plots the "best"line (the one that minimizes the sum of squared deviations) through the various data points. The parameters describing this line are estimated, and the uncertaintysurrounding these estimates are summarized by the standard error of the estimate. 10. (Appendix) Multivariate procedures for summarizing the relationship between adependent and two or more independent variables is a generalization of the univariate procedure, and each coefficient can be interpreted as the effect on the dependentvariable of a one-unit change in the relevant independent variable, holding the other variables constant.11.(Appendix) If an independent variable that should be in an estimating equation is leftout, estimates of the other coefficients may be biased away from their true values. Answers to Even-Numbered Review Questions2. Are the following statements "positive" or "normative"? Why?a. Employers should not be required to offer pensions to their employees.b. Employers offering pension benefits will pay lower wages than they would if they didnot offer a pension program.c. If further immigration of unskilled foreigners is prevented, the wages of unskilledimmigrants already here will rise.d. The military draft compels people to engage in a transaction they would notvoluntarily enter into; it should therefore be avoided as a way of recruiting military personnel.e. If the military draft were reinstituted, military salaries would probably fall. Answer: (a) normative (b) positive (c) positive (d) normative (e) positive4. What are the functions and limitations of an economic model?Answer: The major function of an economic model is to strip away real world complexities and focus on a particular cause/effect relationship. In this sense an economic model is analogous to an architect's model of a building. An architect may be interested in designing a building that fits in harmoniously with its surroundings, and in designing such a building the architect may employ a model that captures the essentials of his or her concerns (namely, appearance) without getting into the complexities ofplumbing, electrical circuits, and the design of interior office space. Similarly, an economic model will often focus on a particular kind of behavior and ignore complexities that are either not germane to that behavior or only of indirect importance.Models used to generate insights about responses to a given economic stimulus are often not intended to forecast actual outcomes. For example, if we are interested in bow behavior is affected by stimulus B, with factors C, D, and E held constant, our model may not correctly forecast the observed behavior if stimuli C through E also change.6. A few years ago it was common for state laws to prohibit women from working morethan 40 hours a week. Using the principles underlying normative economics, evaluate these laws.Answer: Laws preventing women from working more than 40 hours per week essentially blocked mutually beneficial transactions. There were women who wanted to work more than 40 hours a week, and there were employers who wanted to employ them for more than 40 hours a week. The restrictions upon their employment prevented these transactions from occurring and therefore made both the women and their potential employers worse off.8. “Government policies as frequently prevent Pareto efficiency as they enhance it.”Comment.Answer. Achieving Pareto efficiency requires the completion of all mutually beneficial transactions. Ideally, government would step in to provide information is that is blocking mutually beneficial transactions or to establish markets (or market substitutes) when markets do not exist. However, governments also have power to prevent transactions or distort prices, both of which can prevent the completion of mutually beneficial transactions. Government regulations can outlaw certain transactions that the parties to them would consider mutually beneficial (the text mentions laws that historically prevented women from working more than 40 hours per week). Government also has the power to distort prices by setting minimum wages, mandating premiums for overtime work, and so forth.Answers to Even-Numbered Problems2. (Appendix) Suppose that a least squares regression yields the following estimate:Wi = -1 + .3Ai, where W is the hourly wage rate (in dollars) and A is the age in years.A second regression from another group of workers yields this estimate:Wi = 3 + .3Ai - .01(Ai)2.a. How much is a 20-year-old predicted to earn based on the first estimate?b. How much is a 20-year-old predicted to earn based on the second estimate? Answer: a. W = -1 + .3x20 = 5 dollars per hour.b. W = 3 + .3x20 - .01x20x20 = 3 + 6 - 4 = 5 dollars per hour.Suggested Essay Questions1. Child labor is an issue that has been discussed a lot recently. From the perspective ofnormative economics, explain the problem with child labor.Answer: Pareto efficiency requires that transactions have mutual benefits, and this can be assured only if the transactions are voluntary and take place with complete information. Children may be compelled by their parents to work, and they have limited capacities to make informed decisions even in the absence of compulsion.2. A law in one town of a Canadian province limits large supermarkets to just fouremployees on Sundays. Analyze this law using the concepts of normative economics. Answer. There are no doubt large supermarkets that want to hire workers on Sundays (because there are consumers who want to shop on Sundays), and there are no doubt employees who could be induced – perhaps by higher wages – to work on Sundays. A law preventing such work prevents a mutually beneficial transaction.CHAPTER 2 - OVERVIEW OF THE LABOR MARKETOur goal in this text is to move students along very carefully from what they do know to the mastery of new concepts. It is our belief that students learn most efficiently if they can associate these new ideas with an overall framework, and it is the purpose of Chapter 2 to provide that framework. This chapter has both a descriptive and an analytical purpose. One aim is to introduce students to the essential concepts, definitions, magnitudes, and trends of widely used labor market descriptors. To this purpose, the chapter discusses and presents data on such topics as the labor force, unemployment, the distribution of employment, and the level of (and trends in) labor earnings. The second aim is to provide students with an overview of labor market analysis. To this end, we discuss basic concepts of demand and supply so that students will be able to see their interaction at the very outset.We start the overview with a discussion of demand schedules and their corresponding demand curves. Particular attention is given to the distinction between movement along a curve and shifts of a curve. Distinctions between individual and more aggregated demand curves are discussed, as is the distinction between short-run and long-run demand curves.A similar discussion and set of distinctions are made for the supply side of the market. After both the demand and supply sides of the market have been discussed and generally modeled, we turn to the question of wage determination and wage equilibrium. Forces that can alter market equilibria are comprehensively discussed, and the chapter's major concepts are reinforced by discussions of the effects of unions, the existence of disequilibrium, and the concept of being "overpaid" or "underpaid" (including a discussion of economic rents). The chapter ends with a discussion of unemployment across various countries.List of Major Concepts1. The labor market and its various subclassifications (national, regional, local; external,internal; primary, secondary) are defined.2. The "labor force" consists of those who are employed or who are seeking work, andmajor trends in labor force participation rates are discussed.3. The "unemployed" are those who are not employed but are seeking work (or awaitingrecall); trends in the unemployment rate are noted.4. Changes in the industrial and occupational distribution of employment are facilitatedby the labor market, which also facilitates adjustments to the "birth" and "death" of job opportunities.5. The distinction between nominal and real wage rates is made, and the calculation ofreal wages is illustrated.6. Distinctions among wage rates, earnings, total compensation, and income aredepicted graphically.7. The labor market is one of three major markets with which an employer must deal; inturn, labor market outcomes (terms of employment and employment levels) areaffected by both product and capital markets.8. The concepts underlying a labor demand schedule are associated with productdemand, the choice of technology, and the supply schedule of competing factors of production; scale and substitution effects are ultimately related to these forces.9. Underlying a supply schedule for labor are the alternatives workers have and theirpreferences regarding the job's characteristics.10. Distinctions between individual and market demand and supply curves are discussed.11. Movements along, rather than shifts of, demand and supply curves occur when wagesof the job in question change; when a variable not shown on the graph changes, the curves tend to shift.12. The interaction of market demand and supply determines the equilibrium wage.13. Changes in the equilibrium wage rate are caused by shifts in either the demand orsupply curves. Disequilibium will persist if the wage is not allowed to adjust to shifts in demand or supply.14. The concepts of "overpaid" and "underpaid" compare the actual wage to theequilibrium (market) wage rate.15. Individuals paid more than their reservation wage are said to obtain an "economicrent."16. The concepts of shortage and surplus are directly related to the relationship betweenactual and equilibrium wage rates.17. Unemployment rates, and especially long-term unemployment rates, have risen inEurope relative to the United States and Canada over the recent decade; this rise may reflect the existence of relatively stronger nonmarket forces in Europe.Answers to Even-Numbered Review Questions2. Analyze the impact of the following changes on wages and employment in agiven occupation:a.)A fall in the danger of the occupation.b.)An increase in product demand.c.)Increased wages in alternative occupations.Answer: (a) A fall in the danger of the occupation, other things being equal, should increase the attractiveness of that occupation, shifting the supply curve to the right and causing employment to rise and wages to fall.(b) An increase in product demand will shift the demand for labor curve to the right causing both wages and employment to increase.(c) Increased wages in other occupations will render them relatively more attractive than they were before and cause the supply curve to the occupation in question to shift to the left. This will cause employment in this market to fall and wages to rise.4. Suppose a particular labor market were in market-clearing equilibrium. What couldhappen to cause the equilibrium wage to fall? If all money wages rose each year, how would this market adjust?Answer: Starting from the position of equilibrium, a labor market could experience a fall in the equilibrium wage if either the demand curve shifts to the left or the supply curve shifts to the right. While market wages are usually stated in nominal terms, their relationship to the prices of both consumer and producer products is of ultimate importance. Therefore, both parties to the employment relationship are, in the last analysis, concerned with the real wage rate. The real wage rate can fall when the nominal wage rate is rising if prices of consumer and producer products rise even more quickly.6. How will a fall in the civilian unemployment rate affect the supply of recruits for thevolunteer army? What will be the effect on military wages?Answer: Supply curves to a given occupation are drawn holding alternative opportunities constant. If those opportunities become more attractive, the supply curve to the given occupation will shift left and tend to drive up wages. Thus, a fall in the unemployment rate will shift the army's supply curve to the left (there will be fewer recruits at each army wage rate), and the army's wages will be driven up.8. Suppose that the Consumer Product Safety Commission issues a regulation requiringan expensive safety device to be attached to all power lawnmowers. This device does not increase the efficiency with which the lawnmower operates. What, if anything, does this regulation do to the demand for labor of firms manufacturing powerlawnmowers? Explain.Answer: This regulation would cause the demand for labor curve of the firms that manufacture power mowers to shift to the left. The demand for labor is in part derived from product demand. Because it is more costly now to manufacture lawnmowers, the prices that will be charged to consumers will rise. This price increase will move the firm upward and to the left along its product demand curve. With less product demanded for any given wage rate paid to workers, the end result is a leftward shift of the labor demandcurve. (If, however, consumer preferences for greater safety were to shift the product demand curve to the right, employment losses would be mitigated.)10. Suppose we observe that employment levels in a certain region suddenly decline as aresult of (i) a fall in the region's demand for labor, and (ii) wages that are fixed in the short run. If the new demand for labor curve remains unchanged for a long period and the region's labor supply curve does not shift, is it likely that employment in theregion will recover? Explain.Answer: The initial response to a leftward shift in the labor demand curve in the context of fixed wages is for there to be a relatively large decline in employment. This decline in employment is larger than the ultimate decline in employment. The initial disequilibrium between demand and supply in the labor market should force wages down in the long run, and as wages decline firms will move downward along their labor demand curves andwill begin to employ more labor. However, employment in the region would recover to its prior level (assuming no subsequent shifts in demand or supply curves) only if the supply curve was vertical; if supply curves are upward-sloping, the declining wage will cause some withdrawal of labor from the market and employment will not recover to its prior level.Answers to Even-Numbered Problems2.Suppose that the supply curve for school teachers is Ls = 20,000 + 350W and thedemand curve for school teachers is Ld = 100,000 – 150W, where L = the number of teachers and W = the daily wage.a. Plot the demand and supply curves.b. What are the equilibrium wage and employment level in this market?c. Now suppose that at any given wage 20,000 more workers are willing to work asschool teachers. Plot the new supply curve and find the new wage and employment level. Why doesn't employment grow by 20,000?Answer: a. See the figure. Plot the Ld and Ls curves by solving for desired employment at given wage rates. If W = 500, for example, employers desire 25,000 workers (Ld = 100,000 – 150x500); if W = 400, they would desire 40,000. Since the equation above is for a straight line, drawing a line using these two points gives us the demand curve. Use the same procedure for the labor supply curve.。

劳动经济学课后习题参考答案 (1)

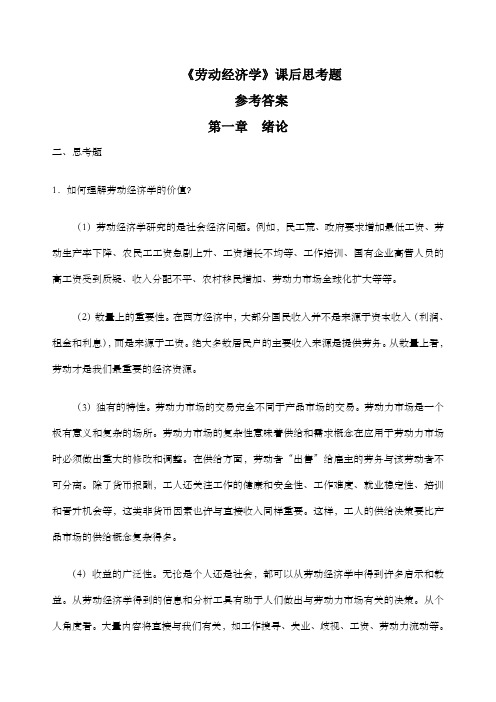

《劳动经济学》课后思考题参考答案第一章绪论二、思考题1.如何理解劳动经济学的价值?(1)劳动经济学研究的是社会经济问题。

例如,民工荒、政府要求增加最低工资、劳动生产率下降、农民工工资急剧上升、工资增长不均等、工作培训、国有企业高管人员的高工资受到质疑、收入分配不平、农村移民增加、劳动力市场全球化扩大等等。

(2)数量上的重要性。

在西方经济中,大部分国民收入并不是来源于资本收入(利润、租金和利息),而是来源于工资。

绝大多数居民户的主要收入来源是提供劳务。

从数量上看,劳动才是我们最重要的经济资源。

(3)独有的特性。

劳动力市场的交易完全不同于产品市场的交易。

劳动力市场是一个极有意义和复杂的场所。

劳动力市场的复杂性意味着供给和需求概念在应用于劳动力市场时必须做出重大的修改和调整。

在供给方面,劳动者“出售”给雇主的劳务与该劳动者不可分离。

除了货币报酬,工人还关注工作的健康和安全性、工作难度、就业稳定性、培训和晋升机会等,这类非货币因素也许与直接收入同样重要。

这样,工人的供给决策要比产品市场的供给概念复杂得多。

(4)收益的广泛性。

无论是个人还是社会,都可以从劳动经济学中得到许多启示和教益。

从劳动经济学得到的信息和分析工具有助于人们做出与劳动力市场有关的决策。

从个人角度看。

大量内容将直接与我们有关,如工作搜寻、失业、歧视、工资、劳动力流动等。

对于企业管理者来说,从对劳动经济学的理解中所得到的知识背景和分析方法,对做出有关雇用、解雇、培训和工人报酬等方面的管理决策也应该是十分有用的。

从社会角度看,了解劳动经济学将使人们成为更有知识、更理智的公民。

2.劳动经济学的研究方法有哪些?首先要明确劳动经济学的基本假设。

劳动经济学的假设主要表现在以下四个方面:(1)资源的相对稀缺性。

如同商品和资本是稀缺的一样,劳动力资源也是有限的。

时间、个人收入和社会资源的稀缺性构成了经济学分析的基本前提。

(2)效用最大化。

由于劳动资源的稀缺性,人类社会进行生产经营活动时,必须研究劳动资源的合理配置和利用。

《劳动经济学》作者Borjas习题答案

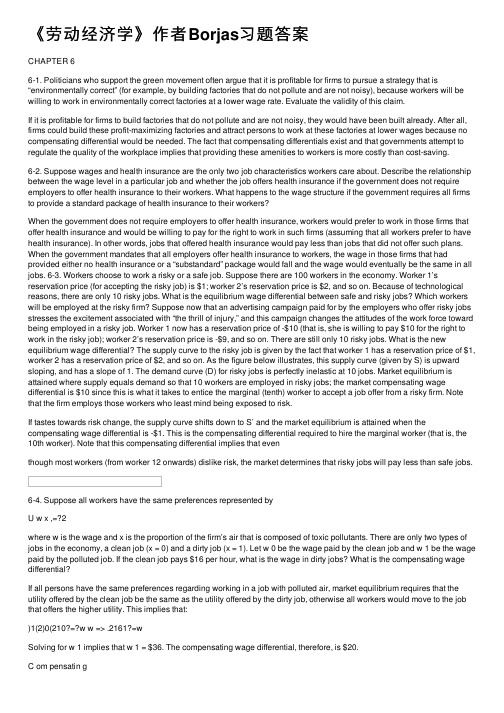

《劳动经济学》作者Borjas习题答案CHAPTER 66-1. Politicians who support the green movement often argue that it is profitable for firms to pursue a strategy that is “environmentally correct” (for example, by building factories that do not pollute and are not noisy), because workers will be willing to work in environmentally correct factories at a lower wage rate. Evaluate the validity of this claim.If it is profitable for firms to build factories that do not pollute and are not noisy, they would have been built already. After all, firms could build these profit-maximizing factories and attract persons to work at these factories at lower wages because no compensating differential would be needed. The fact that compensating differentials exist and that governments attempt to regulate the quality of the workplace implies that providing these amenities to workers is more costly than cost-saving.6-2. Suppose wages and health insurance are the only two job characteristics workers care about. Describe the relationship between the wage level in a particular job and whether the job offers health insurance if the government does not require employers to offer health insurance to their workers. What happens to the wage structure if the government requires all firms to provide a standard package of health insurance to their workers?When the government does not require employers to offer health insurance, workers would prefer to work in those firms that offer health insurance and would be willing to pay for the right to work in such firms (assuming that all workers prefer to have health insurance). In other words, jobs that offered health insurance would pay less than jobs that did not offer such plans. When the government mandates that all employers offer health insurance to workers, the wage in those firms that had provided either no health insurance or a “substandard” package would fall and the wage would eventually be the same in all jobs. 6-3. Workers choose to work a risky or a safe job. Suppose there are 100 workers in the economy. Worker 1’s reservation price (for accepting the risky job) is $1; worker 2’s reservation price is $2, and so on. Because of technological reasons, there are only 10 risky jobs. What is the equilibrium wage differential between safe and risky jobs? Which workers will be employed at the risky firm? Suppose now that an advertising campaign paid for by the employers who offer risky jobs stresses the excitement associated with “the thrill of injury,” and this campaign changes the attitudes of the work force toward being employed in a risky job. Worker 1 now has a reservation price of -$10 (that is, she is willing to pay $10 for the right to work in the risky job); worker 2’s reservation price is -$9, and so on. There are still only 10 risky jobs. What is the new equilibrium wage differential? The supply curve to the risky job is given by the fact that worker 1 has a reservation price of $1, worker 2 has a reservation price of $2, and so on. As the figure below illustrates, this supply curve (given by S) is upward sloping, and has a slope of 1. The demand curve (D) for risky jobs is perfectly inelastic at 10 jobs. Market equilibrium is attained where supply equals demand so that 10 workers are employed in risky jobs; the market compensating wage differential is $10 since this is what it takes to entice the marginal (tenth) worker to accept a job offer from a risky firm. Note that the firm employs those workers who least mind being exposed to risk.If tastes towards risk change, the supply curve shifts down to S′ and the market equilibrium is attained when the compensating wage differential is -$1. This is the compensating differential required to hire the marginal worker (that is, the 10th worker). Note that this compensating differential implies that eventhough most workers (from worker 12 onwards) dislike risk, the market determines that risky jobs will pay less than safe jobs.6-4. Suppose all workers have the same preferences represented byU w x ,=?2where w is the wage and x is the proportion of the firm’s air that is composed of toxic pollutants. There are only two types of jobs in the economy, a clean job (x = 0) and a dirty job (x = 1). Let w 0 be the wage paid by the clean job and w 1 be the wage paid by the polluted job. If the clean job pays $16 per hour, what is the wage in dirty jobs? What is the compensating wage differential?If all persons have the same preferences regarding working in a job with polluted air, market equilibrium requires that the utility offered by the clean job be the same as the utility offered by the dirty job, otherwise all workers would move to the job that offers the higher utility. This implies that:)1(2)0(210?=?w w => .2161?=wSolving for w 1 implies that w 1 = $36. The compensating wage differential, therefore, is $20.C om pensatin gDm ent6-5. Suppose a drop in the compensating wage differential between risky jobs and safe jobs has been observed. Two explanations have been put forward:Engineering advances have made it less costly to create a safe working environment.The phenomenal success of a new action serial “Die On The Job!” has imbued millions ofviewers with a romantic perception of work-related risks.Using supply and demand diagrams show how each of the two developments can explain the drop in the compensating wage differential. Can information on the number of workers employed in the risky occupation help determine which explanation is the right one?The engineering advances make it cheaper for firms to offer safe jobs, and hence reduce the gain from switching from a safe environment to a risky one. This will shift the demand curve for risky jobs in and reduce the compensating wage differential (Figure 1). Note that the equilibrium number of workers in risky jobs goes down.The glamorization of job-related risks may make people more willing to take these risks. This shiftssupply to the right and reduces the compensating differential (Figure 2). Note that the equilibrium number of workers in risky jobs goes up.Thus, information on whether employment in the risky sector increased or decreased can help discern between the two competing explanations.Figure 1. Labor Market for Risky JobsCompensatingDifferentialE new E old Number of Workers in Risky Jobs(w 1 – w 0 )old (w 1 – w 0 )Figure 2. Labor Market for Risky Jobs6-6. Consider a competitive economy that has four different jobs that vary by their wage and risk level. The table below describes each of the four jobs.Job Risk ( r ) Wage ( w )A 1/5 $3B 1/4 $12C 1/3 $23D 1/2 $25All workers are equally productive, but workers vary in their preferences. Consider a worker who values his wage and the risk level according to the following utility function:u w r w r (,)=+12.Where does the worker choose to work? Suppose the government regulated the workplace and required all jobs to have a risk factor of 1/5 (that is, all jobs become A jobs). What wage would the worker now need to earn in the A job to be equally happy following the regulation?Calculate the utility level for each job by using the wage and the risk level: U(A) = 28, U(B) = 28, U(C) = 32, and U(D) = 29. Therefore, the worker chooses a type C job and receives 32 units of happiness. If she is forced to work a type A job, the worker needs to receive a wage of $7 in order to maintain her 32 unitsof happiness as 7 + 25 = 32.CompensatingDifferential E old E new Number of Workers in Risky Jobs(w 1 – w 0 )old (w 1 – w 0 )6-7. Consider Table 6-1 and compare the fatality rate of workers in the agricultural, mining, construction, and manufacturing industries?(a) What would the distribution of wages look like across these four industries given the compensating differential they might have to pay to compensate workers for risk?Mining would pay the highest compensating differential, followed by agriculture, then construction, and finally manufacturing.(b) Now look at the median weekly earnings by industry as reported in Table 629 of the 2002 U.S. Statistical Abstract. Does the actual distribution of wages reinforce your answer to part (a)? If not, what else might enter the determination of median weekly earnings?Median weekly earnings by industry are:$795Mining$371Agriculture$609Construction$613ManufacturingThus, the distribution of wages does not perfectly reflect the compensating differential story, though mining is the best paid and the most dangerous. It is also the unhealthiest, which workers would supposedly take into account as well. Many other factors, however, probably explain the wage structure just as much if not more than compensating differentials, including preferences (family farmers), unions (manufacturing), required skills, and the length of the average work week.6-8. The EPA wants to investigate the value workers place on being able to work in “clean” mines over “dirty” mines. The EPA conducts a study and finds the average wage in clean mines to be $42,250 and the average wage in dirty mines to be $47,250.(a) According to the EPA, how much does the average worker value working in a clean mine?The average value is $47,250 - $42,250 = $5,000.(b) Suppose the EPA could mandate that all dirty mines become clean mines and that all workers who were in a dirty mine must therefore accept a $5,000 pay decrease. Are these workers helped by the intervention, hurt by the intervention, or indifferent to the intervention?All except the marginal worker are hurt by the intervention. The workers who sort themselves into the dirty jobs are those workers that do not mind dirt, and therefore do not value working in a clean job at $5,000. (Similarly, if all of the workers in the clean jobs were forced to accept dirty jobs for $5,000 more, all of them except the marginal worker would be hurt as they all value working in a clean job at more than $5,000.)6-9. There are two types of farming tractors on the market, the FT250 and the FT500. The only difference between the two is that the FT250 is more prone to accidents than the FT500. Over their lifetime, one in ten FT250s is expected to result in an accident, as compared to one in twenty-five FT500s. Further, one in one-thousand FT250s is expected to result in a fatal accident, as compared to only one in five-thousand FT500s. The FT250 sells for $125,000 while the FT500 sells for$137,000. At these prices, 2,000 of each model are purchased each year. What is the statistical value farmers place on avoiding a tractor accident? What is the statistical value of a life of a farmer? The FT500 is associated with an extra cost of $12,000, but its accident rate is only 0.04 compared to the 0.10 accident rate of the FT250. Also, each farmer that buys the FT250 is willing to accept the additional risk in order to save $12,000. Thus, these workers are willing to receive $24 million ($12,000 x 2,000) in exchange for 200 – 80 = 120 accidents. Thus, the value placed on each accident is $200,000. Likewise, the 2,000 farmers who buy the FT250 are willing to receive $24 million in exchange for 2 – .4 = 1.6 fatal accidents. Thus, the value placed on each life is $15 million.6-10. Consider the labor market for public school teachers. Teachers have preferences over their job characteristics and amenities.(a) One would reasonably expect that high-crime school districts pay higher wages than low-crime school districts. But the data consistently reveal that high-crime school districts pay lower wages than low-crime school districts. Why?The likely reason for this is not that teachers do not care about crime – they almost certainly do – but rather that school funding is determined in large part by local property taxes. If high crime schools are located in low income cities, there is nothing (or at least very little) the local school board can do to raise more money to pay the compensating differential.(b) Does your discussion suggest anything about the relation between teacher salaries and school quality?In the end, because high crime schools cannot offer the necessary compensating differential, they will not be able to attract the highest quality workers. Therefore, one would expect that the worst schools (with the worst teachers) are located in the poorest communities with the most crime. This is the typical story of proponents of replacing the property tax scheme to fund public education with a federal program.6–11. Many employers willingly offer their employees certain benefits such as health insurance, a retirement plan, gym memberships, or even an on-site subsidized cafeteria. Why?Offering job benefits is identical to offering a job with bad characteristics such as risk. When offering a risky job, for example, the employer must buy-off the risk from the worker. The employer chooses to do this because it is profitable, i.e., because the cost of buying-off the risk is less costly than transforming the job into a safe one. The same (but opposite) argument holds for job benefits. By offering a job with benefits, the employer can pay the worker less as the worker values the benefits. The employer will find it profitable to continue to offer benefits as long as the employer can save more in reducing the wage than it costs to provide the benefits.One reason health insurance benefits are fairly popular is that firms can usually negotiate lower prices and better packages of care than individuals can do by themselves. Also, firms can deduct the cost of their benefits from their net revenue, whereas individuals cannot deduct the full amount of their healthcare expenses.。

《劳动经济学》(作者Borjas)第十一章习题答案