UWES量表17个问项

大学生学习投入量表(UWES-S)的修订报告

大学生学习投入量表(UWES-S)的修订报告大学生学习投入量表(UWES-S)的修订报告一、引言学习投入是指学生在学习过程中所表现出的积极投入态度和行为,是学习效果的关键因素之一。

随着高等教育的迅速发展和大众化,对于大学生学习投入的研究也日益受到重视。

为了更好地评估和促进大学生的学习投入,学者们发展了许多评估工具,其中大学生学习投入量表(UWES-S)是目前被广泛使用的一种工具。

二、大学生学习投入量表(UWES-S)的研究背景UWES-S量表最早是由学者Schaufeli等于2001年开发的。

原始版的UWES-S量表包括17个项目,使用7点Likert量表,被广泛用于评估员工的工作投入。

然而,随着大学生学习投入的研究逐渐增多,研究者们开始逐渐探索将UWES-S量表用于评估大学生学习投入的可行性。

三、修订目的与方法本次修订报告的目的是依据已有的研究成果,对UWES-S量表进行修订,更好地适应大学生学习投入的特点。

修订过程分为三个步骤:项目筛选、专家评议和信效度测试。

首先,在项目筛选阶段,我们参考了以往的研究成果以及专家的意见,将原始版中与大学生学习投入无关的项目进行剔除,仅保留与大学生学习投入相关的项目。

在此基础上,我们还增加了一部分新的项目,以更全面地评估大学生学习投入的不同维度。

其次,在专家评议阶段,我们邀请了大学教育、心理学和测量学领域的专家对修订后的UWES-S量表进行评审。

他们从专业性、适用性和可理解性等方面给出了宝贵的意见,并提出了一些可以进一步完善的建议。

最后,在信效度测试阶段,我们将修订后的UWES-S量表应用于一所大学的500名学生进行了实地调查。

通过分析数据,我们评估了量表的信度和效度,并且进一步验证了修订后的UWES-S量表在评估大学生学习投入方面的合理性和有效性。

四、修订结果与讨论修订后的UWES-S量表共包括15个项目,涵盖了大学生学习投入的三个维度:个人投入、认知投入和情感投入。

学习投入问卷含评分标准

3

4

5

6

7

15在学习过程中,即使精神疲惫,我也能很快恢复

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

16学习时,我能集中注意力,不易分心

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

17即使学习进展不顺利,我也能精力充沛地坚持下去

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

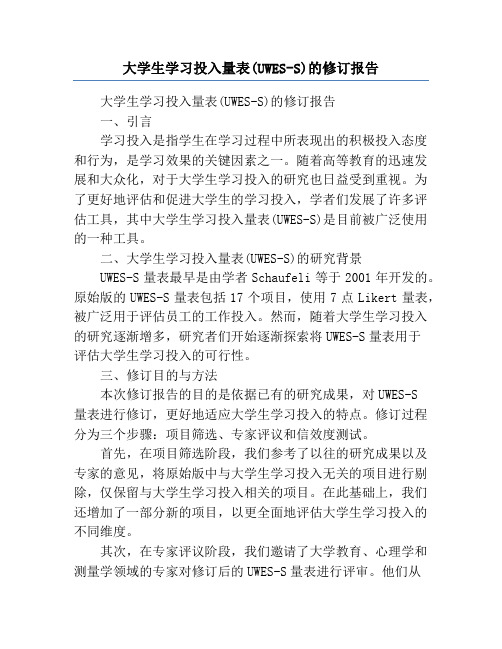

该问卷为李西营于 2010 年翻译修订的国外 Schaufeli 的学习投入量表(the UtrechtWork Engagement Scale-student,缩写为 UWES-S),修订后的量表共包括 17 个项目,问卷采用 Likert7 点计分法,”从 1 到 7 分别代表:从来没有、几乎没有过、很少、有时、经常、十分频繁、总是,问卷分为三个维度,分别为:动机、精力与专注。计分是按照所选数字进行累加计分。

动机共6题,为1、2、3、5、7、9

精力共6题,为4、8、10、12、15、17

专注共5题,为6、11、13、14、16

题目

从来没有

几乎没有

很少

有时

经常

十分频繁

总是

1学习时,我精力充沛

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

2我觉得学习很有价值和意义

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

3学习时,我觉得时间过得很快

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

4学习或上课时,我充满活力

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

5我对学习感兴趣

1

2

3

学习投入问卷(含评分标准)

精力共6题,为4、8、10、12、15、17

专注共5题,为6、11、13、14、16

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8早晨一起床,我就充满学习的力量

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

9专心学习时,我体验到了快乐

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

10我对自己的学习感到满意

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

11学习时,我专心致志

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

12我能充满活力连续学习很长时间

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

13在学习上,我喜欢探究新问题

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

14学习时,我达到了忘我的境界

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

15在学习过程中,即使精神疲惫,我也能很快恢复

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

16学习时,我能集中注意力,不易分心

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

17即使学习进展不顺利,我也能精力充沛地坚持下去

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

该问卷为李西营于2010年翻译修订的国外Schaufeli的学习投入量表(the UtrechtWork Engagement Scale-student,缩写为UWES-S),修订后的量表共包括17个项目,问卷采用Likert7点计分法,”从1到7分别代表:从来没有、几乎没有过、很少、有时、经常、十分频繁、总是,问卷分为三个维度,分别为:动机、精力与专注。计分是按照所选数字进行累加计分。

大学生学习投入及学业自我效能感研究

大学生学习投入及学业自我效能感研究作者:赵静王文娟朱琳来源:《牡丹江师范学院学报(哲学社会科学版)》2020年第06期[摘要] 采用《学习投入量表》及《学业自我效能感量表》,通过方便取样法对某高校大学生进行在线问卷调查,了解新冠肺炎疫情下大学生学习投入及学业自我效能感状况。

结果显示,在学业自我效能感得分上,男生高于女生,大五高于大二和大三,居住在城市和县城者高于居住于农村者;平均每天课外学习时长4小时以上者,学习投入、自我效能感得分均高于4小时以下者;对线上学习有信心者,在学习投入及自我效能感得分均高于没有信心者。

[关键词] 新冠肺炎疫情;线上学习;学习投入;学业自我效能感[中图分类号]G442 [文献标志码]A一、研究背景学习投入是指学生对学习表现出的一种持续的、充满积极情感的状态,它以活力、奉献和专注为主要特征[1]179,学习投入较高时,学业中的收获也会更多。

廖友国等将学习投入定义为学生在开始和执行学习活动时认知和行为上卷入的强度和情感上体验的质量[2]74,并且提出学习投入应该包括认知、情绪和行为三个方面的投入情况。

个体的学习投入容易受到环境因素的影响,环境因素包括外界环境和内在心理环境。

如果学生的学习投入较少,其获得的学习经验和自我认同就会减少,也会影响其对于学术的信心。

[3]107学业自我效能感通常被理解为是自我效能感在学习领域中的表现。

班杜拉认为[4]191,学业自我效能感是个体对自身要达到既定学习和学业目标的能力判断,也指学习者对自己是否有能力或技能去完成学习任务的能力判断和自信评价。

它属于主观范疇而非客观范畴。

[5]11本研究通过问卷调查,了解大学生学习投入、学业自我效能感情况,研究结果将促进学生高效率的学习。

二、研究方法(一)研究对象采取方便抽样法,于2020年5月对某全日制高校学生进行在线问卷调查,收集问卷876份。

其中,男生311人,女生565人;年龄在17-26之间(M=21,SD=1.74);大一222人,大二261人,大三178人,大四112人,大五103人。

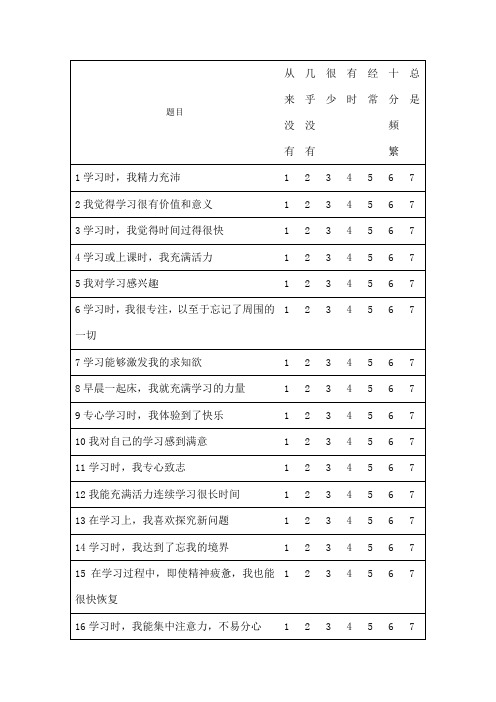

(完整版)mmse量表

(完整版)mmse量表简易精神状态检查量表(MMSE)1.现在是哪一年--- 1 02.现在是什么季节--- 1 03.现在是几月--- 1 04.今天是几号--- 1 05.今天是星期几--- 1 06.咱们现在是在哪个国家--- 1 07.咱们现在是在哪个城市--- 1 08.咱们现在是在哪个城区--- 1 09.这里是哪家医院--- 1 010.这里是第几层楼--- 1 011.我告诉你三种东西,我说完后请你重复一边这三种东西是什么, 树钟表汽车。

请你记住,过一会儿还要让你回忆出它们的名字。

--- ---- ---- 3 2 1 012.请你算一算100 - 7= --- 1 093 - 7= --- 1 086 – 7= --- 1 079 –7 = --- 1 072 – 7= --- 1 013.现在请你说出刚才让你记住的那三样东西--- --- --- 3 2 1 014.(出示手表)这个东西叫什么--- 1 015.(出示铅笔)这个东西叫什么--- 1 016.请你跟着我说“四十四只石狮子”--- 1 017.我给你一张纸请按我说的去做,现在开始;“用右手拿着这张纸,用两只手将它对折起来,放在你的左腿上”。

--- --- --- 3 2 1 018.请你念一念这句话,并按上面的意思去做--- 1 019.请你写一个完整的句子--- 1 020.--- 1 0得分:请您闭上眼睛MMSE评定注意事项1.关于第8个问题,患者如果非本地人,可以改成问他熟悉的城市。

2.关于第11个问题,一定评定者连续说出三种东西3.关于第17个问题,需要连续说出三个动作指令,然后看患者能不能续贯完成。

对于偏瘫患者,指令可以是健侧手。

4.关于第19个问题,向患者强调句子一定要完整。

对于患者说出的句子,一定主语谓语宾语齐全才能得分。

5.关于第20个问题,患者所画出的图形一定有正确的空间关系才能得分。

6.每一个空不正确扣一分,满分30分。

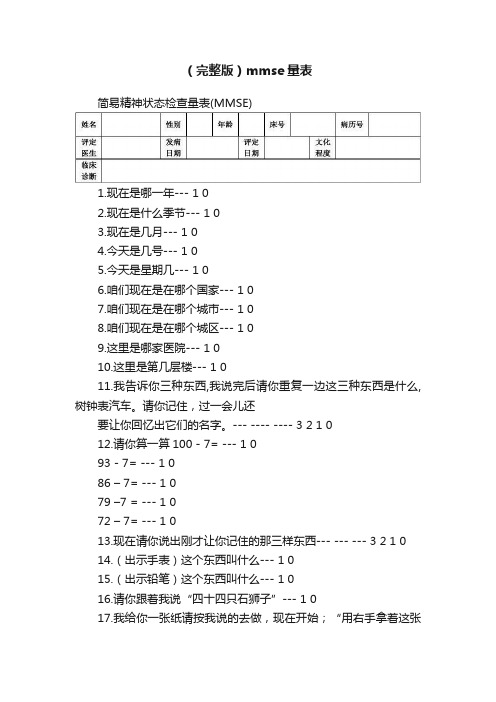

大学生学习投入量表_UWES_S_的修订报告

心理研究 Psychological Research 2010,3(1):84-88

大学生学习投入量表(UWES-S)的修订报告

李西营1 黄 荣2

(1. 河南师范大学 教育科学学院,新乡 453007; 2. 南京师范大学 教育科学学院,南京 210046)

摘 要:目的:修订适用于中国大学生的学习投入量表。 方法:抽取300名大学生为样本进行分析。 结果:(1)中文版UWES-S分为动 机,精力和专注三个维度;(2)问卷的α系数为0.815-0.919;(3)问卷有较好的结构效度和效标关联效度。 各分量表与总量表的相关系 数在0.856-0.902之间。 效标关联效度分析表明学习投入量表能较好预测学生的学习成绩 。 结论:该问卷的测量指标符合心理测量 学要求,但是还需要进一步结合我国的实际进行验证。 关键词:学习投入;大学生学习投入量表

目前,关于学习投入的研究较少,对于学习投入 还没有形成比较一致的概念。乔晓熔认为,学习投入 是学生在开始和执行学习活动时行为上卷入的强度 和情感上体验的质量[4]。 投入既包括行为成分,又包 括情感成分。投入可以通过开始、参与、努力、集中注 意坚持、 在困难或失败面前继续尝试等行为上的表 现和积极的情感体验(如积极、乐观、热情、高兴、好 奇、兴趣)来体现,并可以在朝向奋斗目标的行为中 得到证明。苏红等人认为,学习投入是指学习者在学 习 过 程 中 消 耗 的 经 费 、 时 间 和 精 力 等 资 源 的 总 称 [5]。 William 认 为 , 学 习 投 入 是 指 学 生 学 习 过 程 中 的 动 机 水平,学生的学习动机水平越高,那么他在学习中付 出的努力就越多[6]。 Schaufeli认为,学习投入是个体 学习时具有充沛的精力和良好的心理韧性, 认识到 学习的意义,对学习充满热情,沉浸于自己的学习之 中的状态, 学习投入可以归为活力 (vigor)、 奉献 (dedication)和专注(absorption)三个维度[7-8]。

汉密尔顿抑郁量表使用说明

汉密尔顿抑郁量表使用说明汉密尔顿抑郁量表是临床上评定抑郁状态时最常用的量表。

(24项版)一、评定方法:应由经过训练的两名评定员对被评定者进行汉密尔顿抑郁量表联合检查。

一般采用交谈与观察方式,待检查结束后,两名评定员分别独立评分。

若需比较治疗前后抑郁症状和病情的变化,则于入组时,评定当时或入组前一周的情况,治疗后2-6周,再次评定,以资比较。

二、评定标准: 五级评分项目:0为无1轻度2中度3重度4很重三级评分项目:0为无1轻度-中度2重度下面介绍各项目名称及具体评分标准:1.抑郁情绪⊙只在问到时才诉述 1 ⊙在言语中自发地表达 2 ⊙不用言语也可从表情、姿势、声音或欲哭中流露出这种情绪 3 ⊙病人的自发和非自发语言(表情、动作),几乎完全表现为这种情绪 4 2.有罪感⊙责备自己,感到自己已连累他人 1 ⊙认为自己犯了罪,或反复思考以往的过失和错误 2 ⊙认为目前的疾病,是对自己错误的惩罚,或有罪恶妄想 3 ⊙罪恶妄想伴有指责或威胁性幻觉 4 3.自杀⊙觉得活着没有意义 1 ⊙希望自己已经死去,或常想到与死有关的事 2⊙消极观念(自杀念头) 3 ⊙有严重自杀行为 4 4.入睡困难⊙主诉有时有入睡困难,即上床后半小时仍不能入睡 1 ⊙主诉每晚均有入睡困难 2 5.睡眠不深⊙睡眠浅多恶梦 1 ⊙半夜(晚上12点以前)曾醒来(不包括上厕所) 2 6.早醒⊙有早醒,比平时早醒1小时,但能重新入睡 1 ⊙早醒后无法重新入睡 2 7.工作和兴趣⊙提问时才诉述 1 ⊙自发地直接或间接表达对活动、工作或学习失去兴趣,如感到没精打采,犹豫不决,不能坚持或需强迫自己去工作或活动 2 ⊙病室劳动或娱乐不满3小时 3 因目前的疾病而停止工作,住院患者不参加任何活动或者没有他人帮助便不能完成病室日常事务 4 8.迟缓:指思维和语言缓慢,注意力难以集中,主动性减退。

⊙精神检查中发现轻度迟缓 1 ⊙精神检查中发现明显迟缓 2 ⊙精神检查进行困难 3⊙完全不能回答问题(木僵) 4 9.激越⊙检查时表现的有些心神不定 1 ⊙明显的心神不定或小动作多 2 ⊙不能静坐,检查中曾站立 3 ⊙搓手,咬手指,扯头发,咬嘴唇 4 10.精神性焦虑⊙问到才时诉述 1 ⊙自发地表达 2 ⊙表情和言谈流露明显忧虑 3 明显惊恐 4 11.躯体性焦虑:指焦虑的生理症状,包括口干、腹胀、腹泻、打呃、腹绞痛、心悸、头痛、过度换气和叹息、以及尿频和出汗等。

大学生学习投入量表_UWES_S_的修订报告

因素一:动机。指个体非常喜欢学习并对学习充

行回译,确定译文的准确性。 第三步,调整问题描述 满兴趣,理解学习的意义,并在学习中体验到快乐。

方式,使其符合中国人的语言习惯和思考方式,形成

因素二:精力。指个体具有充沛的精力和良好的

问卷第一稿。 第四步,对221名在校大学生进行随机 心理韧性,为自己的学习努力付出而不易疲倦,并且

注为0.815。 表明了该量表在总体上有较好的稳定性

2 结果

2.1 项目分析 对量表所有题目进行项目区分度分析。 各个项

目的鉴别指数D≥0.4,符合心理测量学的要求[10]。 计

和内部一致性。 2.4 效度分析 2.4.1 结构效度

从探索性因素分析的结果可以看出, 各个项目 的 负 荷 均 在 0.5 以 上 , 三 个 因 子 的 方 差 累 计 贡 献 率 为

专注

2 189.87 10.889***

1>2(p<0.012),2>3(p=0.012),1>3(p<0.001)

总量表 2 25.24

7.783***

1>2(p=0.001),2>3(p=0.004),1>3(p<0.001)

注:1 代表一等(85 分及以上),2 代表二等(70~84 分),3 代表三等(70 分以下)

代 表 有 时/一 个 月 几 次 ,4 代 表 经 常/一 周 一 次 ,5 代 表

采用主成分分析法,斜交旋转,析出的因子数为

十分频繁/一周几次,6代表总是/每天。

3。 这3因素累积解释方差为59.153%,单个因素解释

1.3 问卷的修编

的总方差分别为44.691%、8.169%、6.292%, 因素特

中文版Utrecht工作投入量表的信效度检验

中文版Utrecht工作投入量表的信效度检验一、本文概述随着积极心理学的兴起,工作投入作为员工积极心理状态的重要体现,越来越受到研究者和实践者的关注。

在中国文化背景下,对员工工作投入的研究不仅有助于提升员工个人的工作满意度和幸福感,还能为企业创造更大的价值。

因此,本文旨在探讨中文版Utrecht工作投入量表的信度和效度,以期为中国情境下的工作投入研究提供可靠的测评工具。

本文将对Utrecht工作投入量表进行简要的介绍,阐述其在国际范围内的应用情况。

接着,本文将重点讨论中文版量表的翻译与修订过程,包括翻译的原则、步骤以及修订的依据。

在此基础上,本文将通过实证研究检验中文版量表的信度和效度,包括内部一致性信度、重测信度、结构效度和效标效度等方面。

本文将总结研究结果,讨论中文版Utrecht工作投入量表在中国文化背景下的适用性,并展望未来的研究方向。

通过本文的研究,我们期望为工作投入领域的研究者和实践者提供有益的参考和借鉴。

二、文献综述近年来,随着积极心理学的兴起,工作投入作为员工个体积极、充实的工作状态,日益受到研究者的关注。

作为工作倦怠的对立面,工作投入不仅对员工个体的身心健康、工作满意度和组织承诺有积极的影响,而且能够提升组织的整体绩效。

因此,准确评估员工的工作投入状态对于提升员工的工作效率和组织的整体绩效至关重要。

在众多评估工作投入的量表中,Utrecht工作投入量表(UWES)因其良好的信度和效度在国际上得到了广泛的应用。

该量表由Schaufeli 等人于2002年开发,包括活力、奉献和专注三个维度,旨在全面评估员工的工作投入程度。

由于其简洁、易操作的特点,UWES在国内外得到了广泛的应用和研究。

然而,在跨文化背景下,量表的文化适应性和信效度可能会受到影响。

因此,对中文版UWES进行信效度检验具有重要的理论和实践意义。

通过对中文版UWES的信效度进行检验,可以评估其在中国文化背景下的适用性,为准确评估中国员工的工作投入状态提供有效的工具。

Test manual UWES

UWESU TRECHTW ORK E NGAGEMENT S CALEPreliminary Manual[Version 1, November 2003]Wilmar Schaufeli&Arnold Bakker© Occupational Health Psychology UnitUtrecht UniversityPage1. The concept of work engagement (4)2. Development of the UWES (6)3. Validity of the UWES (8)4. Psychometric quality of the Dutch version (11)4.1. Description of the Dutch language database (11)of the items (13)4.2. Distributioncharacteristics14consistency……………………………………………………………………………4.3. Internalstructure and inter-correlations (15)4.4. Factor4.5. Relationships with burnout (17)4.6. Relationships with age and gender (18)occupational groups (19)4.7. Differencesbetweenversion (21)4.8. Shortenedversion (21)4.9. Student5. Other language versions (23)international language database (24)the5.1. Descriptionof5.2. Distribution characteristics of the items...................................................... .. (26)5.3. Reliability........................................................................................ .. (26)structure and inter-correlations....................................................... .. (28)5.4. Factor5.5. Relationships with age and gender (30)………..countries……………………………………………………….315.6. Differencesbetweenversion (32)5.7. Shortened6. Practical use (33)6.1. Completion and scoring (34)336.2. Dutchnorms…………………………………………………………………………………...6.3. Other language norms (37)7. Conclusion (41)ReferencesAppendix: UWES versionsContrary to what its name suggests, Occupational Health Psychology has almost exclusive been concerned with ill-health and un well-being. For instance, a simple count reveals that about 95% of all articles that have been published so far in the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology deals with negative aspects of workers' health and well-being , such as cardiovascular disease, Repetitive Strain Injury, and burnout. In contrast, only about 5% of the articles deals with positive aspects such as job satisfaction and motivation. This rather one-sided negative focus is by no means specific for the field of occupational health psychology. According to a recent estimate, the amount of psychological articles on negative states outnumbers the amount of positive articles by 17 to 11.However, it seems that times have changed. Since the beginning of this century, more attention is paid to what has been coined positive psychology: the scientific study of human strength and optimal functioning. This approach is considered to supplement the traditional focus of psychology on psychopathology, disease, illness, disturbance, and malfunctioning. The recent trend to concentrate on optimal functional also aroused attention in organizational psychology, as is demonstrated by a recent plea for positive organizational behavior; that is ‘…the study of positively oriented human resource strengths and psychological capacities that can be measured, developed, and effectively managed for performance improvement in today’s workplace’ 2.Because of the emergence of positive (organizational) psychology, it is not surprising that positive aspects of health and well-being are increasingly popular in Occupational Health Psychology. One of these positive aspects is work engagement, which is considered to be the antipode of burnout. Whilst burned-out workers feel exhausted and cynical, their engaged counterparts feel vigorous and enthusiastic about their work. In contrast to previous positive approaches – such as the humanistic psychology – who were largely unempirical, the current positive psychology is empirical in nature. This implies the careful operationalization of constructs, including work engagement. Hence, we wrote this test-manual of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES).This test manual is preliminary, which means that our work on the UWES is still in progress. Nevertheless, we did not want to wait any longer with publishing some important psychometric details since many colleagues, both in The Netherlands as well as abroad, are working with the UWES. Many of them have contributed to this preliminary test-manual by proving us with their data. Without their help this manual could not have been written. Therefore, we would like to thank our colleagues for their gesture of true scientific collaboration3.Utrecht/Valéncia, November 20031 Diener, E., Suh, E.M., Lucas, R.E. & Smith, H.I (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125,267-302.2 Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 695-706.3 Sarah Jane Cotton (AUS), Edgar Bresco (SPA), Maureen Dollard (AUS), Esther Greenglass (CAN), Asbjørn Grimsmo (NOR), Gabriele Haeslich (GER), Jari Hakanen (FIN), Sandrine Hollet (FRA), Aristotelis Kantas (GRE), Alexandra Marques Pinto (POR), Stig Berge Matthiesen (NOR), Susana Llorens (SPA), Astrid Richardsen (NOR), Peter Richter (GER), Ian Rothmann (SAF), Katariina Salmela-Aro (FIN), Marisa Salanova (SPA), Sabine Sonnentag (GER), Peter Vlerick (BEL), Tony Winefield (AUS), Hans de Witte (BEL), Dieter Zapf (GER).1. The concept of work engagementWork engagement is the assumed opposite of burnout. Contrary to those who suffer from burnout, engaged employees have a sense of energetic and effective connection with their work activities and they see themselves as able to deal well with the demands of their job. Two schools of thought exist on the relationship between work engagement and burnout. The first approach of Maslach and Leiter (1997) assumes that engagement and burnout constitute the opposite poles of a continuum of work related well-being, with burnout representing the negative pole and engagement the positive pole. Because Maslach and Leiter (1997) define burnout in terms of exhaustion, cynicism and reduced professional efficacy, it follows that engagement is characterized by energy, involvement and efficacy. By definition, these three aspects of engagement constitute the opposites of the three corresponding aspects of burnout. In other words, according to Maslach and Leiter (1997) the opposite scoring pattern on the three aspects of burnout – as measured with the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI; Maslach, Jackson & Leiter, 1996) – implies work engagement. This means that low scores on the exhaustion- and cynicism-scales and a high score on the professional efficacy scale of the MBI is indicative of engagement.However, the fact that burnout and engagement are assessed by the same questionnaire has at least two important negative consequences. First, it is not plausible to expect that both concepts are perfectly negatively correlated. That is, when an employee is not burned-out, this doesn’t necessarily mean that he or she is engaged in his or her work. Reversibly, when an employee is low on engagement, this does not mean that he or she is burned-out. Secondly, the relationship between both constructs cannot be empirically studied when they are measured with the same questionnaire. Thus, for instance, both concepts cannot be included simultaneously in one model in order to study their concurrent validity.For this reason we define burnout and work engagement are two distinct concepts that should be assessed independently (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2001). Although employees will experience work engagement and burnout as being opposite psychological states, whereby the former has a positive quality and the latter a negative quality, both need to be considered as principally independent of each other. This means that, at least theoretically, an employee who is not burned-out may score high or low on engagement, whereas an engaged employee may score high or low on burnout. In practice, however, it is likely that burnout and engagement are substantively negatively correlated. In contrast to Maslach and Leiter’s (1997) approach, our approach enables the assessment of the strength of the association between work engagement and burnout since different instruments assess both independently. It is possible to include both constructs simultaneously in one analysis, for instance, to investigate whether burnout or engagement explains additional unique variance in a particular variable after the opposite variable has been controlled for.Work engagement is defined as follows (see also Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá & Bakker, 2001): ‘Engagement is a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor,dedication, and absorption. Rather than a momentary and specific state, engagement refers toa more persistent and pervasive affective-cognitive state that is not focused on any particularobject, event, individual, or behavior. Vigor is characterized by high levels of energy andmental resilience while working, the willingness to invest effort in one’s work, and persistenceeven in the face of difficulties. Dedication refers to being strongly involved in one's work andexperiencing a sense of significance, enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, and challenge. Absorption,is characterized by being fully concentrated and happily engrossed in one’s work, wherebytime passes quickly and one has difficulties with detaching oneself from work’Accordingly, vigor and dedication are considered direct opposites of exhaustion and cynicism, respectively. The continuum that is spanned by vigor and exhaustion has been labeled energy or activation, whereas the continuum that is spanned by dedication and cynicism has been labeled identification (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2001). Hence, work engagement is characterized by a high level of energy and strong identification with one's work. Burnout, on the other hand, is characterized by the opposite: a low level of energy combined with poor identification with one's work.As can be seen from the definition above, the direct opposite of the third aspect of burnout – professional inefficacy – is not included in the engagement concept. There are two reasons for this. First, there is accumulating empirical evidence that exhaustion and cynicism constitute the core of burnout, whereas lack of professional efficacy seems to play a less prominent role (Maslach, Schaufeli & Leiter, 2001; Shirom, 2002). Second, it appeared from interviews and discussions with employees and supervisors that rather than by efficacy, engagement is particularly characterized by being immersed and happily engrossed in one's work – a state that we have called absorption. Accordingly, absorption is a distinct aspect of work engagement that is not considered to be the opposite of professional inefficacy. Based on the pervious definition, a self-report questionnaire – called the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) – has been developed that includes the three constituting aspects of work engagement: vigor, dedication, and absorption.Vigor is assessed by the following six items that refer to high levels of energy and resilience, the willingness to invest effort, not being easily fatigued, and persistence in the face of difficulties.1. At my work, I feel bursting with energy2. At my job, I feel strong and vigorous3. When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work4. I can continue working for very long periods at a time5. At my job, I am very resilient, mentally6. At my work I always persevere, even when things do not go well*Those who score high on vigor usually have much energy, zest and stamina when working, whereas those who score low on vigor have less energy, zest and stamina as far as their work is concerned.Dedication is assessed by five items that refer to deriving a sense of significance from one’s work, feeling enthusiastic and proud about one’s job, and feeling inspired and challenged by it.1. I find the work that I do full of meaning and purpose2. I am enthusiastic about my job3. My job inspires me* This item is has been eliminated in the 15-item version of the UWES.4. I am proud on the work that I do5. To me, my job is challengingThose who score high on dedication strongly identify with their work because it is experienced as meaningful, inspiring, and challenging. Besides, they usually feel enthusiastic and proud about their work. Those who score low do not identify with their work because they do not experience it to be meaningful, inspiring, or challenging; moreover, they feel neither enthusiastic nor proud about their work.Absorption is measured by six items that refer to being totally and happily immersed in one’s work and having difficulties detaching oneself from it so that time passes quickly and one forgets everything else that is around.1. Time flies when I'm working2. When I am working, I forget everything else around me3. I feel happy when I am working intensely4. I am immersed in my work5. I get carried away when I’m working6. It is difficult to detach myself from my job*Those who score high on absorption feel that they usually are happily engrossed in their work, they feel immersed by their work and have difficulties detaching from it because it carries them away. As a consequence, everything else around is forgotten and time seems to fly. Those who score low on absorption do not feel engrossed or immersed in their work, they do neither have difficulties detaching from it, nor do they forget everything around them, including time.Structured qualitative interviews with a heterogeneous group of Dutch employees who scored high on the UWES showed that engaged employees are active agents, who take initiative at work and generate their own positive feedback (Schaufeli, Taris, Le Blanc, Peeters, Bakker & De Jonge, 2001). Furthermore, their values seem to match well with those of the organization they work for and they also seem to be engaged in other activities outside their work. Although the interviewed engaged workers indicated that they sometimes feel tired, unlike burned-out employees who experience fatigue as being exclusively negative, they described their tiredness as a rather pleasant state because it was associated with positive accomplishments. Some engaged employees who were interviewed indicated that they had been burned-out before, which points to certain resilience as well as to the use of effective coping strategies. Finally, engaged employees are not workaholic because they enjoy other things outside work and because, unlike workaholics, they do not work hard because of a strong and irresistible inner drive, but because for them working is fun.2.The development of the UWESOriginally, the UWES included 24 items of which the vigor-items (9) and the dedication-items (8) for a large part consisted of positively rephrased MBI-items. For instance, ’’When I get up in the morning, I feel like going to work’’ (vigor) versus ’’I feel tired when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job’’ (exhaustion) and ’’I am enthusiastic about my job’’ (dedication) versus ’’I have become less enthusiastic aboutmy work’’ (cynicism). These reformulated MBI-items were supplemented by original vigor and dedication items, as well as with new absorption items to constitute the UWES-24 . After psychometric evaluation in two different samples of employees and students, 7 items appeared to be unsound and were therefore eliminated so that 17 items remained: 6 vigor items, 5 dedication items, and 6 absorption items (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá & Bakker, 2002a). The resulting 17-item version of the UWES is included in the Appendix. Subsequent psychometric analyses uncovered two other weak items (AB06 en VI06), so that in some studies also a 15-item version of the UWES has been used (e.g., Demerouti, Bakker, Janssen & Schaufeli, 2001). The databases that are analyzed for this test-manual include the UWES-15 as well as the UWES-17 (see 4.1 and 5.1).The results from psychometric analyses with the UWES can be summarized as follows:• Factorial validity. Confirmatory factor analyses show that the hypothesized three-factor structure of the UWES is superior to the one-factor model and fits well to the data of various samples from The Netherlands, Spain and Portugal (Salanova, Schaufeli, Llorens, Pieró & Grau, 2000; Schaufeli et al., 2002a; Schaufeli, Martínez, Marques-Pinto, Salanova & Bakker, 2002b; Schaufeli, Taris & Van Rhenen, 2003). However, there is one exception, using explorative factor analyses Sonnentag (2003) found did not find a clear three-factor structure and decided to use the total-score on the UWES as a measure for work engagement.• Inter-correlations. Although, according to confirmatory factor analyses the UWES seems to have a three-dimensional structure, these three dimensions are closely related. Correlations between the three scales usually exceed .65 (e.g., Demerouti et al., 2001; Salanova et al., 2000; Schaufeli et al., 2002a, 2002b), whereas correlations between the latent variables range from about .80 to about .90 (Salanova et al., 2000; Schaufeli et al., 2002a, 2002b).• Cross-national invariance. The factor structure of the slightly adapted student version of the UWES (see4.9) is largely invariant across samples from Spain, The Netherlands and Portugal (Schaufeli et al.,2002b). Detailed analyses showed that the loadings of maximum three items differed significantly between the samples of the three countries.• Internal consistency. The internal consistency of the three scales of the UWES is good. That is, in all cases values of Cronbach's α are equal to or exceed the critical value of .70 (Nunnaly & Bernstein, 1984). Usually values of Cronbach's α for the scales range between .80 and .90 (Salanova et al., 2000;Salanova, Grau, Llorens & Schaufeli, 2001; Demerouti et al., 2001; Montgomery, Peeters, Schaufeli & Den Ouden, 2003; Salanova, Bresó & Schaufeli, 2003a; Schaufeli, Taris & Van Rhenen, 2003;Salanova, Carrero, Pinazo & Schaufeli, 2003b; Schaufeli & Bakker, in press).• Stability. Scores on the UWES are relatively stable across time. Two, year stability coefficients for vigor, dedication and absorption are .30, .36, and .46, respectively (Bakker, Euwema, & Van Dierendonk, 2003).In sum: these psychometric results confirm the factorial validity of the UWES – as expected, the UWES consists of three scales that are highly correlated. Besides, this pattern of relationships is observed among samples from different countries, which confirms the cross-national validity of the three-factor solution. Taken together this means that engagement is a construct that consists of three closely related aspects that are measured by three internally consistent scales.3. The validity of the UWESSince its introduction in 1999, a number of validity studies have been carried out with the UWES that uncover its relationship with burnout and workaholism, identify possible causes and consequences of engagement and elucidate the role that engagement plays in more complex processes that are related to worker's health and well-being. Below these validity studies are reviewed.• Work engagement and burnout. As expected, the three aspects of burnout – as measured with the MBI – are negatively related with the three aspects of work engagement (Salanova, Schaufeli, Llorens, Pieró & Grau, 2000; Demerouti et al., 2001; Schaufeli et al., 2002a; Schaufeli, Martínez, Marques-Pinto, Salanova & Bakker, 2002b; Montgomery et al., 2003; Schaufeli & Bakker, in press). However, the pattern of relationships slightly differs from what was expected. Namely, vigor and exhaustion are much less strongly inter-related than could be expected on theoretical grounds, whereas (lack of) professional efficacy was most strongly related to all three aspects of engagement. As a consequence, a second-order factor analytic model in which the three sub-scales load together with lack of professional efficacy on one factor and exhaustion and cynicism on the other factor fits well to the data (Salanova et al., 2000; Schaufeli et al., 2002a; Schaufeli, Taris & Van Rhenen, 2003; Schaufeli & Bakker, in press).A similar result was obtained by Demerouti et al. (1999) using discriminant analyses. In this study, thethree engagement scales plus lack of professional efficacy loaded on one discriminant function, whereas both other burnout scales loaded on the second remaining function. A possible explanation for these findings may be that lack of professional efficacy is measured with items that are positively formulated and that are subsequently reversed to constitute a ''negative'' score that is supposed to be indicative for lack of professional efficacy. Recently, Bouman, Ten Brake en Hoogstraten (2000) showed that the notoriously low negative correlations between lack of professional efficacy and both other burnout dimensions change dramatically in much higher positive correlations when instead of reversing positively formulated items, negative items are used to tap lack of efficacy. Still unpublished Belgian, Dutch (Waegenmakers, 2003) and Spanish studies replicate this remarkable result. In other words, that professional efficacy is stronger related to engagement than to burnout is probably partly due to the fact that the efficacy items of the MBI have been positively phrased instead of negatively. However, it is also conceivable that work engagement leads to feelings of professional efficacy.• Work engagement and workaholism. A recent study on the construct validity of work engagement, burnout and workaholisme showed that engagement and workaholism are hardly related to each otherwith the exception of absorption that correlates moderately positive with the workaholism aspect ‘working excessively’ (Schaufeli, Taris & Van Rhenen, 2003). Moreover, it is remarkable that vigor and dedication are negatively – albeit weakly – correlated with the second defining characteristic of workaholism, namely ’’strong inner drive’’. Obviously, the irresistible inner drive of the workaholic to work is different from the vigor and dedication characteristic of the engaged employee. This study also showed that work engagement and workaholism are related to different variables: both types of employees work hard and are loyal to the organization they work for, but in case of workaholism this goes at the expense of the employee's mental health and social contacts outside work, whereas engaged workers feel quite good, both mentally as well as socially.• Possible causes of work engagement. It should be emphasized that we are dealing with possible causes (and consequences) of engagement, since only very few causal inferences can be made because the majority of studies is cross-sectional in nature. Work engagement is positively associated with job characteristics that might be labeled as resources, motivators or energizers, such as social support form co-workers and one's superior, performance feedback, coaching, job autonomy, task variety, and training facilities (Demerouti et al., 2001; Salanova et al., 2001, 2003; Schaufeli, Taris & Van Rhenen, 2003; Schaufeli & Bakker, in press). Sonnentag (2003) showed that the level of experienced work engagement is positively associated with the extent to which employees recovered from their previous working day. Moreover, work engagement is positively related with self-efficacy (Salanova et al., 2001), whereby it seems that self-efficacy may precede engagement as well as follow engagement.(Salanova, Bresó & Schaufeli, 2003). This means that an upward spiral may exist: self-efficacy breeds engagement, which in its turn, increases self-efficacy beliefs, and so on. In a similar vein, a recent unpublished study among students showed that previous academic performance (i.e., the student's GPA as taken from the university's computerized student information system) correlated positively with engagement (Waegenmakers, 2003). An earlier study across three countries had already revealed that engagement is positively related to self-reported academic performance (Schaufeli et al., 2002b).Furthermore, it appears that employee's who take the positive feelings from their work home or who – vice versa – take the positive experiences at home to their work exhibit higher levels of engagement compared to those where there is no positive cross-over between the two different domains (Montgomery et al., 2003). Finally, in a study among working couples it was shown that wives' levels of vigor and dedication uniquely contribute to husbands' levels of vigor and dedication, respectively, even when controlled for several work and home demands (Bakker, Demerouti & Schaufeli, 2003). The same applies to husband's levels of engagement that are likewise influenced by their wives' levels of engagement. This means that engagement crosses over from one partner to the other, and vice versa. So far, two longitudinal studies have been performed on the possible causes of burnout. The study of Bakker et al (2003) among employees from a pension fund company showed that job resources such as social support from one's colleagues and job autonomy are positively related to levels of engagement that are measured two years later. Also, it appeared in this study that engaged employees are successful in mobilizing their job resources. Bakker, Salanova, Schaufeli and Llorens (2003) found similar results among Spanish teachers.• Possible consequences of work engagement. The possible consequences of work engagement pertain to positive attitudes towards work and towards the organization, such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and low turnover intention (Demerouti et al., 2001; Salanova et al., 2000; Schaufeli & Bakker, in press; Schaufeli, Taris & Van Rhenen, 2003), but also to positive organizational behavior such as, personal initiative and learning motivation (Sonnentag, 2003), extra-role behavior (Salanova, Agut & Peiró, 2003), and proactive behavior (Salanova et al., 2003). Furthermore, there are some indications that engagement is positively related to health, that is, to low levels of depression and distress (Schaufeli, Taris & Van Rhenen, 2003) and psychosomatic complaints (Demerouti et al., 2001).Finally, it seems that work engagement is positively related to job performance. For instance, a study among about one-hundred Spanish hotels and restaurants showed that employees’ levels of work engagement had a positive impact on the service climate of these hotels and restaurants, which, in its turn, predicted employees' extra-role behavior as well as customer satisfaction (Salanova, Agut, & Peiró, 2003). It is important to note that, in this study, work performance was measured independently from the employees, namely by interviewing customers about their satisfaction with the service received.• Work engagement as a mediator in the motivation process. The previous findings about possible causes and consequences suggest that work engagement may play a mediating role between job resources on the one hand and positive work attitudes and work behaviors at the other hand. In a recent study, Schaufeli and Bakker (in press) tested such a model among four samples from different types of service organizations. Their structural equation model also included job stressors, burnout, and health complaints. They found some evidence for the existence of two types of processes: (1) a process of health impairment or erosion in which job stressors and lacking job resources are associated with burnout, which, in its turn is related to health complaints and negative work attitudes; (2) a motivational process in which available job resources are associated with work engagement, which, in its turn, is associated with positive work attitudes. Also other studies confirmed the mediating role of work engagement. Essentially, the results of Schaufeli and Bakker (in press) have been replicated by Hakanen, Schaufeli and Bakker (2003) in a study among a large sample of Finnish teachers.Furthermore, the results of the study by Salanova, Agut and Peiró (2003) corroborate the model of Schaufeli and Bakker (in press): work engagement plays a mediating role between job resources (e.g., technical equipment, participation in decision making) and service climate and job performance (i.e., extra-role behavior and customer satisfaction) Moreover, in another study among over 500 ICT-workers, Salanova et al. (2003) observed that work engagement mediated the relationship between available resources (performance feedback, task variety, and job control) and proactive organizational behavior.• Work engagement as a collective phenomenon. Work engagement is not only an individual phenomenon, but it also occurs in groups; that is, it seems that employees in some teams or parts of the organization are more engaged than in other teams or parts (Salanova, Agut en Peiró, 2003; Taris, Bakker, Schaufeli & Schreurs, 2003). Obviously, engagement is not restricted to the individual employee, but groups of employees may differ in levels of engagement as well. Bakker and Schaufeli。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

J Happiness Stud(2009)10:459–481DOI10.1007/s10902-008-9100-yThe Construct Validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale:Multisample and Longitudinal EvidencePiia Seppa¨la¨ÆSaija MaunoÆTaru FeldtÆJari HakanenÆUlla KinnunenÆAsko TolvanenÆWilmar SchaufeliPublished online:6May2008ÓSpringer Science+Business Media B.V.2008Abstract This study investigated the factor structure and factorial group and time invariance of the17-item and9-item versions of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES;Schaufeli et al.(2002b)Journal of Happiness Studies3:71–92).Furthermore,the study explored the rank-order stability of work engagement.The data were drawn fromfive different studies(N=9,404),including a three-year longitudinal study(n=2,555), utilizingfive divergent occupational samples.Confirmatory factor analysis supported the hypothesized correlated three-factor structure—vigor,dedication,absorption—of both UWES scales.However,while the structure of the UWES-17did not remain the same across the samples and time,the structure of the UWES-9remained relatively unchanged. Thus,the UWES-9has good construct validity and use of the9-item version can be recommended in future research.Moreover,as hypothesized,Structural Equation Modeling showed high rank-order stabilities for the work engagement factors(between 0.82and0.86).Accordingly,work engagement seems to be a highly stable indicator of occupational well-being.Keywords Work engagementÁUtrecht Work Engagement ScaleÁConstruct validityÁFactor structureÁFactorial group and time invarianceÁRank-order stabilityP.Seppa¨la¨(&)ÁS.MaunoÁT.FeldtÁA.TolvanenDepartment of Psychology,University of Jyva¨skyla¨,P.O.Box35,40014Jyva¨skyla¨,Finlande-mail:piia.r.seppala@psyka.jyu.fiJ.HakanenDepartment of Psychology,Finnish Institute of Occupational Health,Helsinki,FinlandU.KinnunenDepartment of Psychology,University of Tampere,Tampere,FinlandW.SchaufeliDepartment of Psychology,Utrecht University,Utrecht,The Netherlands123460P.Seppa¨la¨et al. 1IntroductionWith the emergence of positive psychology(e.g.,Seligman2002,2003;Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi2000;Turner et al.2002)added to the fact that the number of positive constructs of occupational well-being are limited,the concept of work engagement has received increasing attention in thefield of occupational health psychology(Schaufeli and Salanova2007).Work engagement,including the three dimensions of vigor,dedication and absorption,is assumed to be a strictly positive and relatively stable indicator of occupational well-being(Schaufeli et al.2002b).The three dimensions of work engage-ment are also included in the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale(UWES),a survey which has been developed to measure work engagement(Schaufeli et al.2002b).The UWES has been translated into many languages and used among different occu-pational groups(e.g.,blue-collar workers,dentists,hospital staff,managers,police officers, teachers;see Schaufeli2007a;Schaufeli and Bakker2003)although its psychometric properties have remained somewhat less explored.For example,it is still unclear whether the theoretically based three-dimensional structure of the scale remains the same across different occupational groups(i.e.,factorial group invariance)and/or across different measurement points(i.e.,factorial time invariance).Furthermore,while the time-invari-ance of the structure of the scale is uncertain,the assumed stability of work engagement remains without strong empirical evidence.Accordingly,the aim of this study was to investigate the psychometric properties of the UWES by utilizingfive divergent data sets,one of which was longitudinal,gathered in Finland(N=9,404).Specifically,the purpose of the study was to test the factor structure of the UWES and its group-and time-invariant properties by means of confirmatory factor analysis(CFA).The former was studied by evaluating the factor structure of the UWES acrossfive samples containing different,although mainly white-collar,occupational groups (i.e.,dentists,educational staff,health care staff,managers,and young managers),and the latter by utilizing the so-called multi-sample method and among the dentists(n=2,555), three-year longitudinal data with two measurement points.Furthermore,the longitudinal data made it possible to investigate the stability of work engagement during this three-year time-period.Also the stability of work engagement was assessed by using CFA within the Structural Equation Modeling(SEM)framework,a procedure which results in an error-free stability coefficient for work engagement.1.1Work EngagementWork engagement is considered as the positive opposite of burnout(Schaufeli et al.2002b; see also Maslach et al.1996;Maslach and Leiter1997;Maslach et al.1996,2001).Spe-cifically,Schaufeli et al.(2002b,p.74)define work engagement‘‘as a positive,fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor,dedication,and absorption.’’Vigor,refers to high levels of energy and mental resilience while working,the willingness to invest effort in one’s work,and persistence in the face of difficulties.Dedication is char-acterized by a sense of significance,enthusiasm,inspiration,pride,and challenge. Absorption refers to being fully concentrated and deeply engrossed in one’s work,and is characterized by time passing quickly and difficulties in detaching oneself from work. According to a recent review,work engagement is positively associated,for instance,with mental and psychosomatic health,intrinsic motivation,efficacy beliefs,positive attitudes towards work and the organization,and high performance(Schaufeli and Salanova2007). 123The Construct Validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale461 Furthermore,Schaufeli et al.(2002b,p.74)define work engagement as a relatively stable state of mind:‘‘rather than a momentary and specific state,engagement refers to a more persistent and pervasive affective-cognitive state that is not focused on any particular object,event,individual,or behavior.’’Thus work engagement is considered to be more stable than work-related emotions(e.g.,contented,enthusiastic,cheerful;see Warr1990), but less stable than personality traits,such as the Big Five(for the distinction between emotions,moods,and temperament;see Gray and Watson2001).As a matter of fact,work engagement has been considered a work-related mood(Schaufeli and Salanova2007).1.1.1Utrecht Work Engagement ScaleThe UWES,a self-report questionnaire,consists of17items(UWES-17),which measure the three underlying dimensions of work engagement:vigor(six items),dedication(five items),and absorption(six items)(Schaufeli2007b;Schaufeli et al.2002b;see Appendix). Atfirst the UWES consisted of24items,but after psychometric testing seven unsound items were omitted and17items were retained.Subsequent psychometric analyses revealed another two weak items(item6in the scale of vigor and item6in the scale of absorption;see Schaufeli and Bakker2003),and hence a15-item version of the UWES has been used in some studies(e.g.,Xanthopoulou et al.,in press).Recently,a shorter9-item version of the UWES(UWES-9)has also been developed(Schaufeli et al.2006;see Appendix).In this abridged scale,vigor,dedication and absorption are assessed by three items per dimension.1.1.2Previous Studies of the UWESRecent confirmatory factor analytic(CFA)studies have supported the theoretically based correlated three-factor—vigor,dedication,absorption—structure of the UWES-17and UWES-9(e.g.,Hakanen2002;Hallberg and Schaufeli2006;Schaufeli and Bakker2003; Schaufeli et al.2002b,2006).All these studies have also shown that the three factors of work engagement are highly interrelated(correlations between0.60and0.99).Because of the high correlations between the three factors,an alternative one-factor structure of the UWES-17and the UWES-9has also been tested.In this one-factor structure all the items were constrained to load on one underlying factor(Hallberg and Schaufeli2006;Schaufeli and Bakker2003;Schaufeli et al.2002b,2006).However,in all these studies,the theo-retically based correlated three-factor structure has shown significantly betterfit with the data than an alternative one-factor structure and thus has received most support.In addition to verifying the theoretically based structure of the scale,it is very important to determine whether the structure of the scale remains the same(i.e.,at least the factor loadings remain equal;see,e.g.,Jo¨reskog2005;see also Statistical analyses below)across different contexts and over time.If not,we cannot be sure that we are measuring the same construct and what the construct we are measuring actually is.Therefore,to obtain com-parable results the construct(the structure of the scale)needs to be the same despite,for example,occupation,culture,or time point.Thus far,studies of the factorial invariance of the correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-17and the UWES-9across groups(i.e.,factorial group invariance)have remained rather limited.In fact,the factorial group invariance of the UWES-17has not been fully confirmed,as in previous group-invariance studies the scale has been revised.In a study conducted among students from Spain,the Netherlands,and Portugal,the correlated three-factor structure of a14-item UWES-S(i.e.,a slightly shortened student version of the123462P.Seppa¨la¨et al. UWES-17;vigor item6and absorption items4and6were removed because of non-significant or poor(\0.40)factor loadings)was found to be only partially group-invariant (see Schaufeli et al.2002a).The unconstrained correlated three-factor structure showed significantly betterfit with data than the constrained correlated three-factor structures(i.e., factor loadings and error covariances were constrained to be equal)in all pairs of countries. The detailed analysis also showed that from one to three of the factor loadings differed between the countries;only the factor loadings of the absorption subscale remained the same across all the country comparisons,while the factor loadings of the vigor subscale remained the same in two of the three countries.In addition,a study conducted among Greek and Dutch employees failed to support the factorial group invariance of the correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-15(i.e., vigor item6and absorption item6were removed).In particular,the unconstrained cor-related three-factor structure showed significantly betterfit with data than the constrained correlated three-factor structures(i.e.,factor loadings,factor variances,and error variances were constrained to be equal)(Xanthopoulou et al.,in press).To date,only Schaufeli et al. (2006)have tested the group-invariance of the UWES-9.They found that the correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-9did not remain the same across10countries(Aus-tralia,Belgium,Canada,Finland,France,Germany,The Netherlands,Norway,South Africa,Spain).Specifically,the unconstrained correlated three-factor structurefitted the data significantly better than the constrained correlated three-factor structures(i.e.,the factor loadings and factor covariances were constrained to be equal across10countries). Taken together,the results on factorial group-invariance are somewhat conflicting and the equality of the correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-17and the UWES-9in different contexts has not been shown.Longitudinal studies of work engagement are rare,and to the best of our knowledge the factorial invariance of the correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-17and the UWES-9across time(i.e.,factorial time invariance)has not previously been studied(see Schaufeli2007a).Therefore,it continues to be unclear whether the hypothesized correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-17and the UWES-9remains unchanged over time. Moreover,the hypothesized stability of work engagement remains unclear,since the sta-bility of the construct can only be evaluated if the structure of the scale remains unchanged.In the present study,CFA within the SEM framework makes it possible to test the invariance of the correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-17and the UWES-9across time by connecting CFA models tested at different measurement points in the same model (e.g.,Jo¨reskog2005).Furthermore,demonstration of the structural time-invariance of the UWES-17and the UWES-9allows for the production of error-free rank-order stability coefficients of work engagement.Rank-order stability reflects the degree to which the relative ordering of individuals within a group is maintained over time.Therefore,rank-order stability is conceptually and statistically distinct from traditional exploratory tech-niques,such as investigating absolute mean level changes occurring in a concept over time.Thus far,the rank-order stability of work engagement has been assessed by using correlation coefficients between the corresponding constructs(Llorens et al.2007;Mauno et al.2007;Schaufeli et al.2006).In previous longitudinal studies,the experience of work engagement has tended to remain fairly stable.In a two-year follow-up study in Finland, the test-retest correlations of the UWES-17for vigor,dedication and absorption were0.73, 0.67,0.69,respectively(Mauno et al.2007).Also,in a one-year follow-up study con-ducted in Australia and Norway,the corresponding test-retest correlations of the UWES-9 were0.61,0.56,and0.60for Australia,and0.71,0.66,and0.68for Norway(Schaufeli et al.2006).In a study among Spanish university students,the test-retest correlations were 123The Construct Validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale463 0.68for vigor and0.61for dedication over a three-week period,when a slightly adapted student version of the vigor and dedication subscales of the UWES-17were used in a laboratory setting(Llorens et al.2007).1.2Aims of the StudyTo sum up,the psychometric testing of the UWES is still in progress and warrants further research.So far,only a few studies have been conducted on factorial group invariance (Schaufeli et al.2002a,2006;Xanthopoulou et al.,in press).These have shown somewhat conflicting results and in no case has factorial group invariance been demonstrated. Moreover,according to the definition,work engagement is considered a stable rather than a momentary state of mind(Schaufeli et al.2002b);however,the true stability of work engagement remains unclear,as evidence for the factorial time invariance of the scale is lacking.In addition,the short version of the scale has only recently been developed,and therefore the psychometric properties of the UWES-9have not yet been fully tested.The present study addresses each of these concerns.Specifically,the present study investigated the construct validity of the Finnish trans-lations of the UWES-17and the UWES-9.Thefirst aim was to test whether the Finnish translations of the scales would include the three interrelated theoretically based dimen-sions of vigor,dedication,and absorption.To ensure the validity of the hypothesized structure,and since the three dimensions of work engagement have correlated highly in previous studies,an alternative one-factor structure of the UWES-17and UWES-9was also tested.The second aim was to investigate whether the correlated three-factor structure would remain the same across different occupational samples(i.e.,factorial group invariance).The third aim of this study was to investigate whether the correlated three-factor structure would remain the same across different measurement points(i.e.,factorial time invariance)by conducting a three-year follow-up study among dentists.Thefinal aim was to examine the rank-order stabilities of the three work engagement factors across the three-year follow-up period.The study hypotheses,on the basis of the theory and previous studies of work engagement,can be summarized as follows:H1:The correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-17and the UWES-9fits better to the data than the one-factor structure in each occupational sample and at both measurement points.H2:The correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-17and the UWES-9remains the same across thefive occupational samples.H3:The correlated three-factor structure of the UWES-17and the UWES-9remains the same across the two measurement points.H4:The rank-order stabilities of the work engagement factors are relatively high over the three-year follow-up time.2Method2.1ParticipantsThe study was based onfive independent samples containing a total of9,404Finnish participants.Table1shows the distribution of background factors(gender,age,123T a b l e 1B a c k g r o u n d c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s a n d m e a n l e v e l s o f t h e d i m e n s i o n s o f w o r k e n g a g e m e n t f o r t h e s t u d y s a m p l e sV a r i a b l eS a m p l e 1S a m p l e 2S a m p l e 3S a m p l e 4S a m p l e 5T o t a l H e a l t h c a r e (n =736)Y o u n g m a n a g e r s (n =747)M a n a g e r s (n =1,301)E d u c a t i o n (n =3,365)D e n t i s t s (n =3,255,f o l l o w -u p n =2,555)N =9,404G e n d e r20032006F e m a l e 639(87%)108(15%)394(30%)2,534(79%)2,328(72%)1,883(74%)6,003(65%)M a l e 97(13%)637(85%)902(70%)676(21%)927(28%)672(26%)3,239(35%)A g eM =44.00S D =9.81R a n g e =19–63M =30.96S D =3.22R a n g e =23–35M =47.88S D =8.52R a n g e =23–6516–25(5%)26–35(24%)36–45(25%)46–55(31%)O v e r 55(15%)M =45.79S D =9.43R a n g e =23–82M =48.49S D =8.82R a n g e =27–76R a n g e =16–82O r g a n i z a t i o n a l /j o b t e n u r e O r g a n i z a t i o n a l t e n u r eO r g a n i z a t i o n a l t e n u r eO r g a n i z a t i o n a l t e n u r eJ o b t e n u r eJ o b t e n u r eR a n g e =0–52M =13.81S D =9.38R a n g e =0–40M =4.37S D =3.62R a n g e =0–18M =11.86S D =9.35R a n g e 0–40M =12.37S D =9.86R a n g e 0–41M =19.54S D =9.95R a n g e =0–50M =22.30S D =9.41R a n g e =3–52P e r m a n e n t j o b 579(80%)696(93%)1,261(98%)2,183(67%)2,998(94%)2,404(96%)7,717(84%)F i x e d -t e r m j o b 148(20%)50(7%)29(2%)1,087(33%)200(6%)87(4%)1,514(16%)H o u r s w o r k e d w e e k l y M =38.43S D =6.07R a n g e =8–85M =38.52S D =2.90R a n g e =7–50M =47.28S D =8.33R a n g e =16–90M =36.77S D =9.52R a n g e =2–75M =32.88S D =8.16R a n g e =0–79M =32.45S D =7.81R a n g e =2–55R a n g e =0–90U W E S -17V i g o rM =4.51,S D =1.05M =4.57,S D =0.93M =4.52,S D =0.97M =4.58,S D =1.01M =4.52,S D =1.04M =4.59,S D =0.95R a n g e =4.51–4.59D e d i c a t i o nM =4.82,S D =1.12M =4.63,S D =1.13M =4.80,S D =1.08M =4.67,S D =1.19M =4.97,S D =1.09M =4.97,S D =0.99R a n g e =4.63–4.97A b s o r p t i o nM =3.82,S D =1.38M =4.07,S D =1.21M =4.34,S D =1.15M =3.92,S D =1.34M =3.81,S D =1.40M =3.81,S D =1.35R a n g e =3.81–4.34U W E S -9464P.Seppa¨la ¨et al.123T a b l e 1c o n t i n u e dV a r i a b l eS a m p l e 1S a m p l e 2S a m p l e 3S a m p l e 4S a m p l e 5T o t a l H e a l t h c a r e (n =736)Y o u n g m a n a g e r s (n =747)M a n a g e r s (n =1,301)E d u c a t i o n (n =3,365)D e n t i s t s (n =3,255,f o l l o w -u p n =2,555)N =9,404V i g o rM =4.64,S D =1.17M =4.55,S D =1.08M =4.53,S D =1.11M =4.56,S D =1.18M =4.63,S D =1.24M =4.71,S D =1.14R a n g e =4.53–4.71D e d i c a t i o nM =4.66,S D =1.27M =4.54,S D =1.19M =4.71,S D =1.15M =4.56,S D =1.29M =4.89,S D =1.22M =4.85,S D =1.15R a n g e =4.54–4.89A b s o r p t i o nM =4.10,S D =1.40M =4.13,S D =1.29M =4.41,S D =1.18M =4.13,S D =1.44M =4.22,S D =1.44M =4.23,S D =1.37R a n g e =4.10–4.41The Construct Validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale465123466P.Seppa¨la¨et al. organizational/job tenure,type of job contract,hours worked weekly)among the partici-pants and the mean levels for the dimensions of work engagement in each sample.Sample1consisted of questionnaire data collected in a single public health care organization in Finland in2003(Central Finland Health Care District,henceforth health care;see Mauno et al.2005,2007).Of the selected random sample,736participants returned the questionnaire(response rate46%).The majority of the participants were women(87%)and worked as nurses(n=468;64%).The other occupational groups represented in the sample were physicians(n=38;5%),clerical workers(n=85;12%) (i.e.,support services),administrative(n=77;11%),researchers/research assistants (n=37;5%),and technical/warehouse/delivery workers(n=23;3%).Sample2consisted of questionnaire data gathered in2006from registered members of two Finnish trade unions(Union of Professional Engineers in Finland and Union of Sal-aried Employees).A postal questionnaire was sent to all members of the trade unions who were age35years or less and in a managerial position(henceforth young managers).The sample consisted of747managers(response rate49%).The great majority of the partic-ipants were men(86%)and they worked in different parts of Finland in both the private and public sectors.Of them43%represented lower management,49%middle management and8%top management.Sample3consisted of questionnaire data gathered in2005from the members offive large Finnish trade unions(Union of Professional Engineers in Finland,Finnish Associ-ation of Graduates in Economics and Business,Finnish Association of Graduate Engineers, Finnish Association for Human Resource Management,and Experts and Managerial Professionals of Municipalities Association;see Kinnunen et al.2008).The random sample consisted of1,301participants(response rate40%)after omitting those employees who were not in a managerial position(henceforth managers).The majority of the par-ticipants were men(70%),and42%represented lower management,26%middle management and32%top management.Sample4consisted of questionnaire data gathered in2001from the Educational Department of Helsinki,Finland(henceforth education;see Bakker et al.2007;Hakanen 2002;Hakanen et al.2006).The sample consisted of3,365participants(response rate 52%)from across the whole organization and from all the professional groups within it. The majority of participants were female(79%)and most of them worked as teachers (n=2,038;60%)at elementary(n=843),lower secondary(n=497),upper secondary (n=278),or vocational schools(n=217).The other occupational groups represented in the sample were support staff(e.g.,psychologist,school assistant)(n=936;28%)and administrative workers(n=391;12%).Sample5consisted of questionnaire data collected in a three-year follow-up study (2003–2006)with two measurement points among Finnish dentists(henceforth dentists; see Hakanen et al.2005).The postal questionnaire was sent to every dentist who was a member of the Finnish Dental Association at the time the data were gathered in2003.In 2003,3,255dentists answered the questionnaire(response rate71%),and in2006,2,555of those identified three years later(n=3,035)returned the questionnaire(response rate 84%).Most of the respondents(over70%)were women and60%of the respondents were employed in the public sector.2.2InstrumentWork Engagement was assessed by using Finnish translations of the UWESs17and9 (Hakanen2002).The accuracy of the Finnish translations was checked by the back-123The Construct Validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale467 translation method.The UWES-17consists of17items on the three underlying dimensions of vigor,dedication,and absorption(Schaufeli2007b;see Appendix).‘‘Vigor’’is measured with six items(items1,4,8,12,15,17),‘‘dedication’’withfive items(items2,5,7,10, 13),and‘‘absorption’’with six items(items3,6,9,11,14,16).Items are rated on a seven-point scale ranging from0(never)to6(every day).The internal consistencies(Cronbach’s alpha)of the UWES-17ranged between0.75and0.83for vigor,between0.86and0.90for dedication,and between0.82and0.88for absorption.The shortened version of the UWES, the UWES-9,contains three items for vigor(items1,4,8),three for dedication(items5,7, 10)and three for absorption(items9,11,14)(Schaufeli et al.2006;see Appendix).The items are rated on the same scale as the UWES-17.The internal consistencies(Cronbach’s alpha)of the UWES-9varied from0.81to0.85for vigor,from0.83to0.87for dedication, and from0.75to0.83for absorption.2.3Statistical AnalysesTo investigate the psychometric properties of the UWES scales,CFA within the SEM framework,performed with the LISREL8.72program(Jo¨reskog and So¨rbom1996a),was used.As the variables were ordinal,the Weighted Least Squares(WLS)estimation pro-cedure based on polychoric correlations and asymptotic covariance matrices,calculated by the PRELIS2.72program(Jo¨reskog and So¨rbom1996b),was applied.Likewise,as the variables were ordinal,threshold values of the observed variables were set to be equal for each sample and in Sample5for both measurement points,using the PRELIS2.72pro-gram(Jo¨reskog and So¨rbom1996b).This was done to ensure that the response scale was the same across the investigated samples and across the different measurement points(see, e.g.,Jo¨reskog2005).The distributions of the responses were skewed—the majority of the answers were in categories4(‘‘O nce a week’’)or5(‘‘A few times a week’’).The polychoric correlation is,however,considered to be rather robust to violations of underlying bivariate normality(see,e.g.,Jo¨reskog2005).Because there is no consensus on thefit indices for evaluating structural equation models(e.g.,Bollen and Long1993;Boomsma2000;Hoyle and Panter1995),modelfit and model comparisons were based on severalfit indices(see Fit indices below).This study focused on the participants who answered all the items of the UWES-17and the UWES-9(i.e.,listwise deletion).The analytic procedure consisted of three steps.In thefirst step of the analyses,the hypothesized correlated three-factor model(henceforth M1;see Fig.1a)of the UWES-17 and the UWES-9was tested for each sample separately,and also for both measurement points in Sample5,to determine whether the observed variables(items)of work engagement loaded on the hypothesized latent factors(vigor,dedication,absorption)on each occasion.To ensure that the correlated three-factor model was valid,an alternative one-factor model(henceforth M2;see Fig.1b)of the UWES-17and the UWES-9was also tested.In the one-factor model,all the items were restricted to load on one latent factor.In the second step of the analyses,the factorial group invariance of the best-fitting factor model was simultaneously investigated across thefive samples by using the multi-sample method(i.e.,data on the same variables collected from several samples were estimated in a joint analysis).The factorial group invariance of the UWES-17and the UWES-9was tested by comparing thefit of the baseline model(i.e.,thresholds of observed variables were constrained to be equal and other parameter estimates were freely estimated)to that of the constrained model(i.e.,thresholds of observed variables and factor loadings were constrained to be equal across thefive samples).Since the statistical power of a structural123468P.Seppa¨la¨et al.equation model is a function of the characteristics of the model and size of the sample,the large sample size of this study might produce results that are of statistical,but not practical, significance(e.g.,Hoyle and Panter1995;see also Fit indices below).Therefore,because of the very large sample size(N=9,404),only the weak measurement invariance was tested.To determine weak measurement invariance,the equality of the factor loadings(i.e., same unit of measurement;see Jo¨reskog2005)across samples must be demonstrated;this is not required of the other parameters(see Meredith1964,1993).In other words,the equality of the factor loadings is the minimum assumption for factorial group invariance to hold,because if the factor loadings do not remain the same across different groups,we cannot be sure that we are measuring the same construct and what the construct we are measuring actually is.In the third step of the analyses,the factorial time invariance of the best-fitting factor model of the UWES-17and the UWES-9was investigated over a three-year follow-up with two measurement points(Sample5).First,the baseline stability model was estimated by using structural equations between the latent factors of work engagement to connect the factor models estimated at the two time points.Next,the constrained stability model was estimated by setting the corresponding factor loadings equal across the two measurement points.Factorial time invariance was then tested by comparing thefit of the baseline stability model(i.e.,thresholds of observed variables were set equal and other parameters freely estimated)to the constrained stability model(i.e.,thresholds of observed variables and factor loadings were set equal across the two measurement points).As previously,the equality of the factor loadings at different measurement points must be demonstrated; however,equality of the other parameters is not required to determine weak measurement invariance(see Meredith1964,1993).Finally,the rank-order stabilities of the work engagement factors were investigated by estimating the stability coefficients of the UWES-17 123。