Measuring implicit psychological constructs in organizational behavior

Chapter 8 psychological assessment第8章:心理评估

The Test was primarily used for children’s intellectual ability. The child’s intelligence could compare to other kids of the same age by Binet-Simon Intelligence Test.

3. Tests of Intellectual Ability

3.1 Binet-Simon Intelligence Test

It included items designed to measure ability to follow instructions, to exercise judgement, and to solve a wide variety of problems. The final version contained 54 items arranged in order of difficulty, from following the movement of a lighted match with the eyes, through pointing to named parts of the body and counting backwards from 20, to working out what time a clock face would show if the hour and minute hands swapped places. Also called the Binet scale, though this is unfair to Simon, who played a major part in its development. See also mental age, Stanford-Binet intelligence scale.

What-is-Intelligence

‐ The ability to judge, comprehend, and reason ‐ The ability to understand and deal with people,

g

Spatial s

Arithmetical

s

Conflicting theories have led many psychometric theorists to propose hierarchical theories of intelligence

that include both general and specific components

Spearman also believed that performance on any test of mental ability required the use of a specific ability factor that he termed “s”

s

Logical

s Mechanical

Intelligence Tests and Basic Abilities

Module Objectives: What is intelligence? How do we measure intelligence? Who are the children whose intelligence sets them apart from their peers?

Think on Your Own…

as for specific abilities

心理学专业英语复习材料

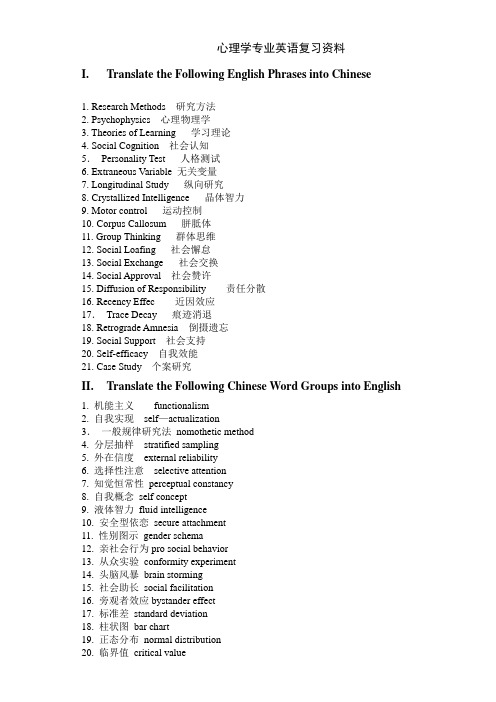

心理学专业英语复习资料I. Translate the Following English Phrases into Chinese1. Research Methods 研究方法2. Psychophysics 心理物理学3. Theories of Learning 学习理论4. Social Cognition 社会认知5.Personality Test 人格测试6. Extraneous Variable 无关变量7. Longitudinal Study 纵向研究8. Crystallized Intelligence 晶体智力9. Motor control 运动控制10. Corpus Callosum 胼胝体11. Group Thinking 群体思维12. Social Loafing 社会懈怠13. Social Exchange 社会交换14. Social Approval 社会赞许15. Diffusion of Responsibility 责任分散16. Recency Effec 近因效应17.Trace Decay 痕迹消退18. Retrograde Amnesia 倒摄遗忘19. Social Support 社会支持20. Self-efficacy 自我效能21. Case Study 个案研究II. Translate the Following Chinese Word Groups into English1. 机能主义functionalism2. 自我实现self—actualization3.一般规律研究法nomothetic method4. 分层抽样stratified sampling5. 外在信度external reliability6. 选择性注意selective attention7. 知觉恒常性perceptual constancy8. 自我概念self concept9. 液体智力fluid intelligence10. 安全型依恋secure attachment11. 性别图示gender schema12. 亲社会行为pro social behavior13. 从众实验conformity experiment14. 头脑风暴brain storming15. 社会助长social facilitation16. 旁观者效应bystander effect17. 标准差standard deviation18. 柱状图bar chart19. 正态分布normal distribution20. 临界值critical value21. 知觉适应perceptual adaptationIII. Multiple Choices1. Like Carl Rogers, I believe people choose to live more creative and meaningful lives. My name isa. Wertheimer.b. Washburn.c. Skinner.d. Maslow.2. The goals of psychology are toa. develop effective methods of psychotherapy.b. describe, predict, understand, and control behavior.c. explain the functioning of the human mind.d. compare, analyze, and control human behavior.3. The "father" of psychology and founder of the first psychological laboratory wasa. Wilhelm Wundt.b. Sigmund Freud.c. John B. Watson.d. B. F. Skinner.4. You see a psychologist and tell her that you are feeling depressed. She talks to you about the goals you have for yourself, about your image of yourself, and about the choices that you make in your life and that you could make in your life. This psychologist would probably belong to the __________ school of psychology.a. humanisticb. psychodynamicc. behavioristicd. Gestalt5. Biopsychologistsa. limit the scope of their study to animals.b. are concerned with self-actualization and free will.c. stress the unconscious aspect of behavior.d. attempt to explain behavior in terms of biological or physical mechanisms.6. In a study of effects of alcohol on driving ability, the control group should be givena. a high dosage of alcohol.b. one-half the dosage given the experimental group.c. a driving test before and after drinking alcohol.d. no alcohol at all.7.The phrase "a theory must also be falsifiable" meansa. researchers misrepresent their data.b. a theory must be defined so it can be disconfirmed.c. theories are a rich array of observations regarding behavior but with few facts to support them.d. nothing.8. A common method for selecting representative samples is to select thema. randomly from the larger population.b. strictly from volunteers.c. by threatening or coercing institutionalized populations.d. from confidential lists of mail order firms.9. The chief function of the control group in an experiment is that ita. allows mathematical relationships to be established.b. provides a point of reference against which the behavior of the experimental group can be compared.c. balances the experiment to eliminate all extraneous variables.d. is not really necessary.10. Which of the following best describes a double-blind experimental procedure?a. All subjects get the experimental procedure.b. Half the subjects get the experimental procedure, half the placebo; which they receive is known only to the experimenter.c. Half the subjects get the experimental procedure, half the placebo; which they receive is not known to subjects or experimenters.d. All subjects get the control procedure.11. A simple experiment has two groups of subjects calleda. the dependent group and the independent group.b. the extraneous group and the independent group.c. the before group and the after group.d. the control group and the experimental group.12. One of the limitations of the survey method isa. observer bias.b. that it sets up an artificial situation.c. that replies may not be accurate.d. the self-fulfilling prophecy.13. To replicate an experiment means toa. use control groups and experimental groups.b. use statistics to determine the effect of chance.c. control for the effects of extraneous variables.d. repeat the experiment using either identical or improved research methods.14. Information picked up by the body's receptor cells is termeda. cognitionb. perception.c. adaptation.d. sensation.15. The incoming flow of information from our sensory systems is referred to asa. sensation.b. perception.c. adaptation.d. cognition.16. A researcher presents two lights of varying brightness to a subject who is asked to respond "same" or "different" by comparing their intensities. The researcher is seeking thea. just noticeable difference.b. absolute threshold.c. subliminal threshold.d. minimal threshold.17. Film is to camera as __________ is to eye.a. retinab. irisc. lensd. pupil18. Black and white vision with greatest sensitivity under low levels of illumination describes the function ofa. the cones.b. the visual pigments.c. the rods.d. the phosphenes.19. Unpleasant stimuli may raise the threshold for recognition. This phenomenon is calleda. aversive stimulation.b. absolute threshold.c. perceptual defense.d. unconscious guard.20. When infants are placed in the middle of a visual cliff, they usuallya. remain still.b. move to the shallow side of the apparatus.c. move to the deep side of the apparatus.d. approach their mothers when called, whether that requires moving to the shallow or deep side.21.The fact that objects that are near each other tend to be grouped together is known asa. closure.b. continuation.c. similarity.d. nearness.22. An ability to "read" another person's mind is termeda. clairvoyance.b. telepathy.c. precognition.d. psychokinesis.23. The fact that infants will often crawl off tables or beds shows thata. depth perception is completely learned.b. human depth perception emerges at about 4 months of age.c. integration of depth perception with motor skills has not yet been accomplished.d. depth perception is completely innate.24. Sensations are organized into meaningful perceptions bya. perceptual constancies.b. localization of meaning.c. perceptual grouping (Gestalt) principles.d. sensory adaptation.25. The analysis of information starting with features and building into a complete perception is known asa. perceptual expectancy.b. top-down processing.c. bottom-up processing.d. Gregory's phenomenon.26.One recommended way for parents to handle problems of occasional bed wetting in children is toa. limit the amount of water they drink in the evening.b. punish them for "wet" nights.c. wake them up during the night to use the toilet.d. consider medication or psychotherapy.27. Teachers, peers, and adults outside the home become important in shaping attitudes toward oneself in Erikson's stage ofa. trust versus mistrust.b. initiative versus guilt.c. industry versus inferiority.d. integrity versus despair.28. With aging there is a decline of __________ intelligence, but not of __________ intelligence.a. fluid; fixedb. fixed; fluidc. fluid; crystallizedd. crystallized; fluid29. The single most important thing you might do for a dying person is toa. avoid disturbing that person by not mentioning death.b. allow that person to talk about death with you.c. tell that person about the stages of dying.d. keep your visits short and infrequent in order to avoid tiring that person.30. The five-factor model of personality includesa. social interactionism.b. neuroticism.c. agreeableness.d. sense of humor.31. An adjective checklist would most likely be used by aa. psychodynamic therapist.b. behaviorist.c. humanistic therapist.d. trait theorist.32. Jung believed that there are basic universal concepts in all people regardless of culture calleda. persona.b. collective consciousness.c. archetypes.d. mandalas.33. Behaviorists are to the external environment as humanists are toa. stress.b. personal growth.c. humankind.d. internal conflicts.34. Self-actualization refers toa. a tendency that causes human personality problems.b. what it is that makes certain men and women famous.c. anyone who is making full use of his or her potentials.d. the requirements necessary for becoming famous, academically distinguished, or rich.35. If you were asked to describe the personality of your best friend, and you said she was optimistic, reserved, and friendly, you would be using the __________ approach.a. psychodynamicb. analyticalc. humanisticd. trait36. The halo effect refers toa. the technique in which the frequency of various behaviors is recorded.b. the use of ambiguous or unstructured stimuli.c. the process of admitting experience into consciousness.d. the tendency to generalize a favorable or unfavorable first impression to unrelated details of personality.37.A truck gets stuck under a bridge. Several tow-trucks are unable to pull it out. At last a little boy walks up and asks the red-faced adults trying to free the truck why they haven't let the air out of the truck's tires. Their oversight was due toa. divergent thinking.b. cognitive style.c. synesthesia.d. fixation.38. __________ thinking goes from specific facts to general principles.a. Deductiveb. Inductivec. Divergentd. Convergent39. In most anxiety disorders, the person's distress isa. focused on a specific situation.b. related to ordinary life stresses.c. greatly out of proportion to the situation.d. based on a physical cause.40. The antisocial personalitya. avoids other people as much as possible.b. is relatively easy to treat effectively by psychotherapy.c. tends to be selfish and lacking remorse.d. usually gives a bad first impression.41. One who is quite concerned with orderliness, perfectionism, and a rigid routine might be classified as a(n) __________ personality.a. histrionicb. obsessive-compulsivec. schizoidd. avoidant42.In psychoanalysis, patients avoid talking about certain subjects. This is calleda. avoidance.b. transference.c. analysis.d. resistance.43. In psychoanalysis, an emotional attachment to the therapist that symbolically represents other important relationships is calleda. resistance.b. transference.c. identification.d. empathy.44. In aversion therapy a person __________ to associate a strong aversion with an undesirable habit.a. knowsb. learnsc. wantsd. hopes45. Behavior modification involvesa. applying non-directive techniques such as unconditional positive regard to clients.b. psychoanalytic approaches to specific behavior disturbances.c. the use of learning principles to change behavior.d. the use of insight therapy to change upsetting thoughts and beliefs.46. A cognitive therapist is concerned primarily with helping clients change theira. thinking patterns.b. behaviors.c. life-styles.d. habits.47.__________ is best known for his research on conformity.a. Aschb. Rubinc. Schachterd. Zimbardo48. Solomon Asch's classic experiment (in which subjects judged a standard line and comparison lines) was arranged to test the limits ofa. social perception.b. indoctrination.c. coercive power.d. conformity.49. Aggression is best defined asa. hostility.b. anger.c. any action carried out with the intent of harming another person.d. none of these50. Which of the following is the longest stage of grieving for most people?a. shockb. angerc. depressiond. agitation51. Which of the following is NOT part of the definition of psychology?A) scienceB) therapyC) behaviorD) mental process52.The term psychopathology refers toA) the study of psychology.B) study of psychological disorders.C) the distinction between psychologists and psychiatrists.D) the focus of counseling psychology.53. In which area of psychology would a researcher interested in how individuals persist to attain a difficult goal (like graduating from college) most likely specialize?A) motivation and emotionB) physiological psychologyC) social psychologyD) community psychology54. A psychologist who focused on the ways in which people's family background related to their current functioning would be associated with which psychological approach?A) the behavioral approachB) the psychodynamic approachC) the humanistic approachD) the cognitive approach55. The researcher most associated with functionalism isA) William James.B) Wilhelm Wundt.C) Charles Darwin.D) E. B. Titchener.56. A psychologist is attempting to understand why certain physical characteristics are rated as attractive. The psychologist explains that certain characteristics have been historically adaptive, and thus are considered attractive. This explanation is consistent with which of the following approaches?A) the sociocultural approachB) the humanistic approachC) the cognitive approachD) the evolutionary approach57. Which approach would explain depression in terms of disordered thinking?A) the humanistic approachB) the evolutionary approachC) the cognitive approachD) the sociocultural approach58. Which of the following would a sociocultural psychologist be likely to study?A) the impact of media messages on women's body imageB) the way in which neurotransmitters are implicated in the development of eating disordersC) the impact of thinking patterns on weight managementD) the benefits of exercise in preventing obesity59. Why is psychology considered a science?A) It focuses on internal mental processes.B) It classifies mental disorders.C) It focuses on observation, drawing conclusions, and prediction.D) It focuses on behavior.60. Why is it important to study positive psychology?A) Psychologists are only interested in the experiences of healthy persons.B) We get a fuller understanding of human experience by focusing on both positive and negativeaspects of life.C) Negative experiences in people's lives tell us little about people's mental processes.D) Psychology has been too focused on the negativeIV. Blank filling1.The perspective that focuses on how perception is organized is called psychology.2.A(n) is a broad explanation and prediction concerning a phenomenon of interest.3.The variable is expected to change as a result of the experimenter's manipulation.4.Bill refuses to leave his house because he knows spiders live outside. Bill is most clearlysuffering from a .5.Learned _______ may develop when a person is repeatedly exposed to negative events overwhich he/she has no control.6.Troublesome thoughts that cause a person to engage in ritualistic behaviors are called________.7.Psychologists consider deviant, maladaptive, and personally distressful behaviors to be______.8.Ken is impulsive, reckless, and shows no remorse when he hurts other people. He is often introuble with the law. Kevin is most likely to be diagnosed with _______ personality disorder.9.The researcher known as the "father of modern psychology" was Wilhelm _______.10.Asking someone to think about their conscious experience while listening to poetry wouldbe an example of _______.11.The field of psychology that is interested in workplace behavior is called Industrial and___________ psychology.12.________ is a statistic that measures the strength of the relationship between two variables.13.In a set of data, the number that occurs most often is called the ______.14.In a set of data, the average score is called the _______.15.A study that collects data from participants over a period of time is known as a(n) ______.16.The variable that a researcher manipulates is called the _______ variable.17._______statistics are used to test a hypothesis.18.A mental framework for how a person will think about something is called a ______.19.Rapid skeletal and sexual development that begins to occur around ages nine to eleven iscalled _______.20.A generalization about a group that does not take into account differences among membersof that group is called a(n) ________.21.Feeling the same way as another, or putting yourself in someone else's shoes, is called______.22.Feelings or opinions about people, objects, and ideas are called _______.23.When you saw a movie in a crowded theater you found yourself laughing out loud witheveryone else. When you saw it at home, though, you still found it funny but didn't laugh as much. This is an example of ________ contagion.24.When Carlos first sat next to Brenda in class he didn't think much of her. After sitting nextto her every day for a month he really likes her. This is best explained by the ________ effect.V.True or false (10 points, 1 point each)1 Positive psychology is not interested in the negative things that happen in people's lives.A) True2 The behavioral approach is interested in the ways that individuals from different cultures behave.A) TrueB) False3. Developmental psychologists focus solely on the development of children.A) TrueB) False4. Psychologists study behavior and mental processes.A) TrueB) False5. Meta-analysis examines many studies to draw a conclusion about an effect.A) TrueB) False6. The 50th percentile is the same as the median.A) TrueB) False7. The standard deviation is a measure of central tendency.A) TrueB) False8. Variables can only have one operational definition.A) TrueB) False9. The scores for 5 participants are 3, 2, 6, 3, and 7. The range is 4.A) TrueB) False10. In correlational research, variables are not manipulated by the researcher.A) TrueB) False11. The placebo effect refers to experimenter bias influencing the behavior of participants.A) TrueB) FalseCarol and Armando work together, go to school together, and socialize together. Carol notices that Armando is always on time to work and class and is never late when they make plans. One day, Armando is late to class. It is likely that Carol would make an external attribution about Armando's lateness.A) TrueB) False12. Violence in movies and television has no effect on people's levels of aggression.A) TrueB) False13. Rioting behavior is usually understood to occur because of groupthink.A) TrueB) False14. Small groups are more prone to social loafing than larger groups.A) TrueB) False15. Piaget believed that children were active participants in their cognitive development.A) True16 A strong ethnic identity helps to buffer the effects of discrimination on well-being.A) TrueB) False17. Older adults experience more positive emotions than younger adults.A) TrueB) False18. Harlow's research showed that infant monkeys preferred to spend time with the "mother" (wireor cloth) on which they were nursed.A) TrueB) False19. To help adolescents research their full potential, parents should be effective managers of theirchildren.A) TrueB) False20. Emerging adulthood is the period between 18 and 30 years of age.A) TrueB) False21. Health psychologists work only in mental health domains.A) TrueB) FalseVI. Essays questions (20 points, 10 points each)1. What is qualitative research interview?2. What is bystander effect? When is it most likely to occur? How can its effects be minimized?3. How important is fathering to children?。

A-level-A2心理学专业学术名词梳理

A-level-A2心理学专业学术名词梳理本文梳理4个主题的内容的学术名词,分别是变态心理学、组织心理学、消费者心理学和健康心理学。

变态心理学Abnormal Psychology1.精神分裂症 schizopheriaDementia 精神错乱Psychotic disorder 精神异常Paranoid 偏执狂Catatonic 紧张性的Disorganized 无组织的、没有条理的Undifferentiated 未分化的Delusion 妄想Hallucination 幻觉Delusional disorder 妄想症Monozygotic twin 同卵双胞胎Dizygotic twin 异卵双胞胎Dopamine 多巴胺Overactive 过度活跃的Matarepresentation system 元表征系统central monitor system 中心控制系统Receptor 接收器Antipsychotics 抗精神病药ECT 电击疗法Token economy 代币性经济Cognitive behavior therapy 认知行为疗法2.双相情感障碍 Bipolar and related behaviors Depression 抑郁症Mania 躁狂症Unipolar 单向的Bipolar 双向的Norepinephrine 去甲肾上腺素Serotonin 血清素Learned helplessness 习得性无助Attributional style 归因风格Antidepressants 抗抑郁药物Cognitive restructure 认知重构Rational emotive behavior therapy 理性情绪疗法3.冲动控制障碍 Impulse control disorders Salience 显著Euphoria 兴奋Tolerance 宽容Withdrawal 戒断Conflict 矛盾Relapse 复发Keptomania 盗窃癖Gambling disorder 赌博障碍Pyromania 纵火癖Postive reinforcement 正向激励Feeling state theory 感觉状态理论Opiate antagonist 类鸦片拮抗剂Covert sensitisation 内隐致敏法Imaginal desensitation 系统脱敏法Implulse control therapy 冲动控制疗法4.焦虑症 Anxiety disorderGeneralized Anxiey disorder 广泛焦虑障碍Apphrehension 恐惧,忧虑Motor tension 运动紧张Autonmic overactivity 自主神经过度活跃Agoraphobia 广场恐惧症Phobia 恐惧症Blood phobia 血液恐惧症Classical conditioning 经典条件反射Generalisation 泛化Extinction 消失Psychoanalytic 精神分析的Oedipus Complex 俄狄浦斯综合症Systematic desensitisation 系统脱敏疗法Applied tension 外施张力Applied relaxation 外施放松5.强迫症 Obsessive compulsive disorders Obsession 痴迷Compulsion 冲动Body dismorphic disorder 躯体变形障碍Neurological 神经系统的Orbitofrontal cortex 前额皮质Urge 冲动Circuit 电路Psychodynamic 精神动力学的Traumatic experience 创伤经历Anal stage 肛欲期Psychosexual development 性心理发展阶段ID 本我Ego 自我Superego 超我Potty training 入厕训练Exposure and response prevention 暴露和反应干预消费心理学Consumer psychology1.物理环境 Physical environmentRetail 零售Leisure 休闲External 外部的Interior 内部的Layout 布局Freeform layout 自由布局Grid layout 网格布局Open air market 露天市场Ambience 气氛Pleasure arousal 兴奋冲动Submissiveness 柔顺Mediating effect 调节效应2.心理环境 Psychological environmentCognitive map 认知地图Graphic 图像的Multidimensional scaling 多维标度Spatial configuration 空间配置Menu design 菜单设计Eye magnet 眼睛磁铁Incongruent 不一致Primacy effect 首因效应Recency effect 近因效应Sensory perception 感官知觉Behavior constraint 行为约束Defending place 保护的地方Queue 队列Instrusion 侵入3.消费者行为 Consumer behaviorUtility 实用功效Endowment 养老Precious 珍贵的Compensatory 补偿Lexigraphic 词素文字的Availability 可用性Representativeness 代表性Anchors 锚Insula 脑岛Nucleus accumben 伏隔核Mesial prefrontal cortex 前额皮质内侧Deactivation 失活Intuitive 直观的Conscious 有意识的Unconscious 无意识的Choice blindness 选择失明False memory 错误的记忆Detector 探测器4.产品 ProductGift wrapping 礼物包装Reveal 揭示Associative learning 联想学习Color association 颜色关联Cultural association 文化关联Horizontal centrality 水平中心Visual attention 视觉注意力Gaze 凝视Cascade 级联Interpersonal influence 人际关系的影响Disrupt 破坏Reframe 重新定义Purchase decision 购买决策Subjective norm 主观规范Planned behavior 计划的行为Intention 意图Divestment 撤资5.广告 AdvertisingPersuasive techique 说服技术Elaborate 精心的Personal relevance 个人的相关性promotion 促销活动Explicit memory 外显记忆Implicit memory 内隐记忆Mental suspicion 精神的怀疑Mental conviction 精神信念Brand recognition 品牌认知度Self monitor 自我监控Slogan 口号健康心理学Health psychology1.医患关系 The patient-practitioner relationship Non-verbal communication 非语言交流Cardigan 开襟羊毛衫Verbal communication 语言交流Directing style 主导风格Sharing style 分享风格Consultation 咨询Practitioner diagnosis 医生诊断Disclosure 信息披露Appraisal 评估Utilisation 利用Hypochondriasis 疑病症Munchausen syndrome 孟乔森综合病征2.遵从医疗建议 Adherence to medical advice Preventative measure 预防措施Acute 急性的Chronic 慢性的Overestimate 高估Incur 承担Adherence 依从性Rational 理性的Health belief model 健康信念模型Vulnerability 脆弱性Severity 严重程度Self efficacy 自我效能Modifying 修改Compliance 合规Antacid 抗酸剂Replenish 补充Prescription 处方Asthma 哮喘Intervention 干预3.疼痛 PainPhysiological response 生理反应tissue 维织dissipate 消散Helplessness 无助Psychogenic pain 心因性疼痛Specificity theory 特异性理论Gate control theory 闸门控制理论Peripheral fibre 外周纤维Spinal cord 脊髓Pain fibre 疼痛纤维Clinical interview 临床访谈Psychometric measure 心理测量Analgesics 止痛剂Anaesthetic 麻醉Attention diversion 注意力转移Cognitive redefinition 认知重新定义Acupuncture 针灸4.压力 stressPhysiology 生理学Autonomic nervous system 自主神经系统Endocrine system 内分泌系统Sympathetic 交感神经的Parasympathetic 副交感神经的Adrenal medullary system 肾上腺髓质系统Cardiovascular problem 心血管问题Gastrointestinal disorder 肠胃失调General adaption syndrome 广泛适应综合征Resistance 阻力Exhaustion 疲惫Cerebral blood flow 脑血流Prefrontal cortex 前额叶皮层Saliva 唾液Persistance 暂留Semantic 语义的Cortisol 皮质醇Beta blocker 受体阻滞药Biofeedback 生物反馈Conceptualisation 概念化Rehearsal 重复5.健康促进 Health promptionFear arousal 恐惧唤起Comprehension 理解Acceptance 接收Medium 媒介Angina pectoris 心绞痛Hyperventilation 换气过度Panic attack 恐惧症Token economy 代币制经济Stroke 中风Coronary heart disease 冠心病Plasma 等离子体Cholesterol 胆固醇Blood pressure 血压Unrealistic optimism 不切实际的乐观Contemplation 沉思Termination 终止组织心理学Psychology and organisation1.工作动力 Motivation to work Hierarchy of need 需求层次Esteem 尊重Self-actualisation 自我实现Existence need 生存需要Relatedness need 联系需要Affiliation 联系Interpersonal relationship 人际关系Thematic 主题Apperception 统觉Expectancy 预期寿命Instrumentality 手段Valence 价Equity 股本Underpayment 缴付不足Overpayment 缴付盈余Instrinsic motivation 内驱动机Extrinsic motivation 外驱动机Bonus 奖金Praise 赞美Empowerment 赋权2.领导力和管理 Leadership and management Universalist 普世的Transformational 转型Charismatic 有魅力的Fostering 培养Initiating 启动Contingency 连续性Permissive 宽容的Autocratic 独裁Followership 追随Alienated 疏远Conformist 墨守成规Pragmatic 务实的3.组织中的小组行为 Group behavior in organisations Storming风暴Norming规范化Adjourning延期Cohesiveness凝聚力Intra内部Cohesion 凝聚力Allowable 允许的Specialist 专家Inventory 库存Illusion 错觉Invulnerability 刀枪不入Morality 道德Censorship 审查Rationalisation 合理化Unanimity 一致Shortcoming 缺点Commission 委员会Omission 遗漏Heuristics 启发式Perseverance 毅力Evidentiary 证据的Hindsight bia 事后偏见Conjunctive bia 连接偏见Availability heuristic 启发可用性Representativeness heuristic 代表启发式Compromise 妥协Avoidance 避免Collaboration 协作Superordinate 地位高的4.组织工作情况 Organisational work condition Hawthorne effect 霍索恩效应Illumination 照明Supervisor 主管Deficiency 缺乏Autonomy 自治Intra departmental 内部部门Inter departmental 国际部门Temporal condition 时间条件Rotation 旋转Metropolitan rota 都市轮值Metropolitan 大都会Slow rotation 慢旋转Mortality 死亡率Diabete 糖尿病Pregnancy 怀孕Visual display 视觉呈现Auditory display 听觉呈现Operator machine system 操作机系统5.工作满意度 Satisfaction at work Motivator 动力源Hygiene 卫生Supervision 监督Autonomy 自治Dimension 维度Enrichment 丰富Job rotation 工作轮换Enlargement 扩大Integration 集成Job sabotage 工作破坏Revenge 复仇Compensation 补偿Absenteeism 旷工Commitment 承诺如何高效记忆心理学学术名词?1.巧用单词卡大家可以回想一下我们小时候是怎么学习英语单词的,幼儿园或者小学的老师会帮助大家把新学的单词记在一张卡片上,然后在卡片的背面标上对应的中文意思或者对应的图片。

核电安全文化评价

Assessing safety culture in nuclear powerstations $T.Lee *,K.HarrisonEnvironmental Psychology and Policy Research Unit,School of Psychology,University of St.Andrews,St.Andrews,Fife KY169JU,UKAbstractDe®nitions of safety culture abound,but they variously refer to the safety-related values,attitudes,beliefs,risk perceptions and behaviours of all employees.This assembly may seem too inclusive to be meaningful,but each represents a di erent level of processing and the choice for measurement (or intervention)is more pragmatic than theoretical.The present study addresses mainly attitudes,but also reported behaviours.This is done using a 120-item questionnaire covering eight domains of safety in three nuclear power stations.Principal components analysis yields 28factors Ðall but four of which are correlated with one or more of nine criteria of accident history.Di erences by gender,age,shifts/days and work areas are revealed,but these are confounded by type of job and ANOVAS are applied to clarify the main sources of variation.The e ects on safety culture of a number of organisational com-ponents are also explored.For example,the role of safety in team brie®ngs,management style,work pressure versus safety,etc.It is concluded that personnel safety surveys can use-fully be applied to deliver a multi-perspective,comprehensive and economical assessment of the current state of a safety culture and also to explore the dynamic inter-relationships of its `working parts'.#2000Elsevier Science Ltd.All rights reserved.Keywords:Safety culture;Nuclear accidents;Nuclear employees;Nuclear power stations;Safety attitudes1.IntroductionConsiderable progress has been made towards `engineering out'the physical causes of accidents in high technology plants.It is now generally acknowledged that individual human frailties and pervasive organisational defects lie behind the majority of the remaining accidents.Although many of these have beenanticipatedSafety Science 34(2000)61±97/locate/ssci0925-7535/00/$-see front matter #2000Elsevier Science Ltd.All rights reserved.P I I:S 0925-7535(00)00007-2$A version of the survey,including the full questionnaire and software for computing factor scores and norms based on ®ve NPS's will shortly be available on CD.*Corresponding author.Tel.:+44-1334-462063;fax:+44-1334-463042.E-mail address:trl@st-andrews@ (T.Lee).62T.Lee,K.Harrison/Safety Science34(2000)61±97in safety rules,prescriptive procedures and management treatises,people don't always do what they are supposed to do.Some employees have negative attitudes to safety which adversely a ect their behaviours.This undermines the system of mul-tiple defences that an organisation constructs and maintains to guard against injury to its workers and damage to its property.This safety management system is essen-tially a social system,wholly reliant on the employees who operate it.Its success depends on three things;its scope,whether employees are knowledgeable about it and whether they are well disposed towards it,i.e.,committed to making it work. The concept of`safety culture'has evolved as a way of formulating and addressing this new focus.An excellent overview and`practical guide'has recently been provided by Cooper(1998).The de®nition of safety culture adopted here is the one proposed by ACSNI(The Advisory Committee on the Safety of Nuclear Installations),i.e.:The safety culture of an organisation is the product of individual and group values, attitudes,perceptions,competencies and patterns of behaviour that determine the commitment to and the style and pro®ciency of an organisation's health and safety management.Organisations with a positive safety culture are characterised by communica-tions founded on mutual trust,by shared perceptions of the importance of safety and by con®dence in the e cacy of preventive measures.(ACSNI,1993,p.23).All de®nitions that attempt to capture the essence of safety culture are bound to be inadequate because each of its many manifestations are extensive,complex and intan-gible.However,two critical attributes may help to®ll out the picture.First,in a healthy culture,the avoidance of accident and injury by all available means is the responsibility of every person in the organisation.Second,the integration of role behaviours and the consolidation of social norms create a common set of expectations,a`way of life'that transcends individual members.A culture is much more than the sum of its parts. This way of conceptualising safety management originated in the nuclear industry, in the aftermath of Chernobyl.But it is related to the similar concept of`safety cli-mate',which in turn evolved from`organisational climate'(Schneider,1975;Zohar, 1980).Some authors still prefer to use this term and others retain both`climate'and `culture',claiming they are useful for di erent purposes(Mearns et al.,1998).Byrom and Corbridge(1997,p.3),for example,de®ne safety climate as``F F F the tangible outputs of an organisation's health and safety culture as perceived F F F at a particular point in time''and Mearns et al.(1998)as a``snapshot in time''.This meteorological terminology is enigmatic,for two reasons.First,`climate'is normal parlance for the underlying consistencies in the weather of a region,not for a transitory state as suggested by these authors.Second,time sampling is the only prac-tical method available for measuring human phenomena but,fortunately,cultures (unlike the weather)change very slowly.Hence,`snapshots'can provide estimates that are likely to remain valid(barring major interventions)for many months. Another perspective is that the`safety climate'is but one facet of several that interact to produce the safety culture.According to Cooper(1998),the safety culture is,``TheT.Lee,K.Harrison/Safety Science34(2000)61±9763 product of multiple goal-directed interactions between people(psychological),jobs (behavioural)and the organisation(situational)''(p.17).He explicitly acknowledges that this tripartite interaction is also represented in the ACSNI de®nition quoted above as well as in earlier formulations.However,Cooper reserves the term`safety climate' for the`people'aspects.This is not a`time sampling'distinction but a`content'one. The overall assessment of this tripartite safety culture complex is obviously beyond the scope of any single method.In the case of the personnel safety survey,the method described here,information is elicited about all three elements,but with di ering degrees of thoroughness and without attempting to identify them sepa-rately.They interact so closely that it is doubtful if the latter could be achieved.The replies to any questions about overt behaviour or about the company safety orga-nisation are inevitably but variously confounded with the respondents'subjective attitudes towards them.We have preferred the superordinate term`safety culture'for another reason, more pragmatic than theoretical.It is the term devised and exclusively adopted by the nuclear industry and used in the many reports on the subject produced by the IAEA(International Atomic Energy Agency).However,whatever de®nitions are used,the proactive stance to safety is now almost universally accepted,if not always practised.In consequence,there is an urgent demand for methods of assessment,for ways of diagnosing weaknesses;also for benchmarking the strengths of safety cultures across time and between organi-sations.The research reported here is in part a response to this growing need for measurement and in part an attempt to disaggregate some of the main working parts of safety cultures as a prelude to exploring their inter-relationships.It is the second main phase(Lee,1998)of an attempt to develop a robust methodology for the assessment of safety cultures in the nuclear industry.It is recognised that a full and comprehensive assessment of a safety culture also requires the kind of data normally supplied in detail through one or other of the safety auditing systems available.This may be supplemented by a peer review pro-cedure,following,for example,the system devised by the World Association of Nuclear Operators(WANO),IAEA,(OSART Review)or the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission(see Section8).However,these are`top-down'methods;they list the systems in place and cannot easily assess how well they are working.When information is available on the latter score it is sparse,or based on the`expert judgement'of the managers responsible for the arrangements,who may be inclined to present a sanguine view.Grote and Ku nzler(2000)describe the use of questionnaires to supplement what they describe as the``predominantly gut feelings''of professional audit sta .Performance indicators are also obviously useful measures of the health of a safety culture and unlike audits and peer reviews,they do have the virtue of measuring mainly outcome as distinct from input.`Feedback of results'is an essential requirement of organisational learning.Some of these measures are based on plant performance,and for these there is an implicit assumption that a well-managed plant optimises both productivity and safety.Others are direct measures of safety performance(e.g.lost time accident rate,recordable incidents,average radiation dose to workers,etc).64T.Lee,K.Harrison/Safety Science34(2000)61±97However,performance indicators are also a`top-down'approach,with management experts setting target levels.This dual purpose,i.e.measurement and motivation, usually implies a link to bonus payments and these may lead to stress,under-reporting of incidents and premature return to work among sick or injured sta .Moreover,it is not always easy to interpret the meaning of performance indicators.For example,a large number of shutdowns(`scrams')may indicate either that errors have resulted in tripping of the reactor or that its operators have reacted cautiously when in doubt. Performance indicators tend also to be long-term measures of safety culture,responding only slowly to changes in organisation(e.g.management style,`downsizing',`out-sourcing',etc).Most important of all,they are gross measures of consequence and give little indication of the causes of upward or downward trending.Finally,there is as yet no clear evidence that performance indicators are valid as predictors of future perfor-mance(Wreathall et al.,1995).These comments on audits and performance indicators should not be taken to imply that they should be supplantedÐonly that they should be supplemented by personnel safety surveys.No single method of assessment is su cient,although the balance between them should perhaps be reconsidered,especially if cost-e ectiveness is in the frame(see Section8).1.1.Attitudes towards safetyIt may be argued that it is a radical step to base safety management partly on the subjective views of sta Ðbut these are the reality on which their working lives are based.It may also be claimed that non-managerial workers`do not see the total picture'Ðbut the same can be said for the management,including those conducting audits and peer reviews.To quote a text from30years ago,``Executives must be prepared to face the real possibility that the attitudes they believe employees have may not coincide with actual employee attitudes.They must recognise that this di erence F F F is not a threat to their personal integrity''(Blum and Naylor,1968,p. 302).A more contemporary perspective would add that the converse also appliesÐworkers are often ignorant of the true attitudes of managers.The total socio-technical system is extremely complex and in an attitudinal approach,all members of the organisation at every level should properly be invited to respond to a standard appraisal of it.They all contribute to the safety cultureÐby de®nition;some have unique knowledge.Both knowledge and attitudes can be mea-sured with relative ease and can be used to monitor changes over time or resulting from speci®c interventions.Moreover,the validity of attitudes can be con®rmed by comparing them with actual behaviour.Work in progress will shortly make it possible for nuclear power stations to assess their performance against a set of norms.2.Previous researchThere are several precedents for the attempt to measure attitudes toward safety in large-scale organisations.They can be traced as far back as the classic HawthorneT.Lee,K.Harrison/Safety Science34(2000)61±9765 studies in the l930H s,when the attitudes of21,216employees of the Western Electric Company in the USA were assessed in a mass interviewing programme(Roethlisber-ger and Dickson,1939).It was strongly argued by a number of authors during the l980s that negative attitudes among workers are the precursors of`unsafe'behaviour and their origins,in turn,in defective management attitudes and practices.(Jonson, 1982;Beck and Feldman,1983;Purdham,1984;Sheehy and Chapman,1984,1987; Gri ths,l985;Allen,1986;Lee,1998).A number of`in house'surveys were carried out during this period and Lutness(l987) argued persuasively for an instrument developed by the Du Pont safety organisation, but provided little ing mainly qualitative methods,Marcus(l988)studied24 nuclear power stations in the USA and concluded that those plants where the attitudes of employees favoured control,responsibility and a generally proactive attitude towards safety had three times fewer`error events'and a generally better safety record. Zohar(1980)is generally credited with publishing the®rst quantitative study of attitudes that focuses speci®cally on safety,using principal components analysis (PCA).He extracted eight factors from his40-item questionnaire.Glennon(1982), Brown and Holmes(1986)in the USA,and Coyle et al.(1995)in Australia attemp-ted to con®rm these eight factors as an underlying basic structure,but without much success.The latter authors did,however,detect signi®cant di erences between an accident and a no-accident group using a somewhat revised version.This quest for what they termed``a possible architecture of safety attitudes''was also pursued by Cox and Cox(1991),who surveyed a European-wide sample of chemical/gas manufacturing plants.A review of these and other studies in the lit-erature leads the present authors to the conclusion that di erences in the chosen breadth and depth of coverage,in judgements over item selection and wording,toge-ther with cross-cultural and inter-industry variations render the quest for universal structure premature,at the least.Olearnik and Canter(1988)were probably the®rst in the UK to use a survey(and other instruments such as`uncompleted sentences')of safety attitudes and,indeed,to seriously address the issue of validation.They report results from16plants of a steel company.Their data provide a better prediction of accident rates in these plants than `expert judgements'of their relative hazardousness.This initiated an important stream of work in the chemical and later,in the power generation industries.A safety attitude questionnaire comprising a basic16standardised scales has been developed.Reliability coe cients are quoted and correlations with accident rates are reported as`satisfactory' (Donald,1994,1997;Donald and Canter,1994;Donald and Young,1996).An o shore safety questionnaire has been developed by Flin et al.(1996)and applied,for example,to722workers on11o shore installations.The original emphasis of this work was on risk perceptions but it has broadened to include per-ceptions of the job and work environment,attitudes to safety and perceptions of organisational factors relevant to safety.From a total of19scales,14show sig-ni®cant di erences between an accident and no-accident group(Mearns et al.,1997). In the Norwegian sector of the North Sea,Rundmo(1992)has considerably extended the early work of Marek et al.(1987),which focused on the perceived risks of`ordinary accidents',disasters and post-accident measures.In particular,he is the66T.Lee,K.Harrison/Safety Science34(2000)61±97only researcher so far to have demonstrated an improvement in safety culture over a (4-year)period.He has also applied structural equation modelling in an attempt to establish the causal relationships between risk perceptions and various scales of protective measures,i.e.safety status,job stress and accidents/near misses.He con-cludes,``The higher the perceived risk,the more dissatis®ed with safety status,the more accidents and near accidents they experience''(Rundmo,1995,p.1).The work by Cox and Cox(1991),referred to above,has also continued,extend-ing into the o shore industry and to the development of a general purpose``Safety Behavioural Toolkit''.This is based on a triangulation approach through ques-tionnaires,interviews and behavioural observation at both the individual and orga-nisational levels(Cox et.al.,1997).Also recently,the Health and Safety Executive in the UK has launched a do-it-yourself survey(Byrom and Corbridge,1997)which is applicable to all industries.This instrument is described in more detail in Section8. The main previous work in the nuclear industry was initiated by the authors in collaboration with Mr.J.A.Coote of British Nuclear Fuels and was carried out at the Sella®eld site in1991(Lee and Coote,1993;Lee,1997,1998).Ostrom et al. (1993)have also developed a combined questionnaire/interview approach covering 13categories of safety norms,designed for use in US nuclear stations.The aim of the research presented in the present paper was to build on these foundations to customise a procedure for UK nuclear power stations.3.MethodThree stations were selected for the study from widely separated sites in the UK and representing di erent technologies.A total of seven focus groups were held,two in each station plus an additional group con®ned to contractors.The groups were each composed of a cross-section of 10À12sta ,including two or three managers and at least one safety rep.The discus-sions were recorded verbatim and subsequently analysed qualitatively.The general conclusions that emerged are summarised in a separate(unpublished)report(Lee and Sibley,1996).The focus group material suggested a number of areas that extend the range of the study more widely than before.New items were added to a shortened(but equivalent)form of the Sella®eld questionnaire and this revised and extended draft version was returned for piloting and further discussion by members of each of the focus groups.This led to suggestions for still further items and for general re®nement of the proposed ones.It should be noted that a good safety survey should be gener-ated from,as well as administered to,the entire workforce or a representative sample. The original Sella®eld questionnaire contained172items,but the analysis showed that this could be reduced to approximately80without loss of validity.This shor-tened form was then customised for the present study to a total of120.It is expected that the present analysis will again make it possible to reduce the number of items for more convenient general application and without sacri®cing validity.The questionnaires were distributed in each of the three stations in di erent ways. Common to each was the use of the monthly team brie®ng session to explain theT.Lee,K.Harrison/Safety Science34(2000)61±9767 aims and background of the study.Respondents were supplied with sealable envel-opes pre-addressed to the University of St.Andrews,giving further reinforcement to the assurance of anonymity provided in the introduction.Partly because of the di erent circumstances prevailing at each of the stations but mainly because of the di erent methods adopted for distribution,the response rates were variable,i.e.167(45%),248(46%)and268(74%),respectively.The total sample is683.The variability is due to di erent methods adopted by stations for distributing the survey forms.All were explained and distributed at team brie®ngs. However,in one case they were requested back`as soon as possible'.In another,some were completed at the brie®ng and a deadline set for others.In the third,this was supplemented by unremitting pleas through the various communication media and a donation to charity,proportional to the response rate,was promised.Experience shows that questionnaires need to be completed as well as distributed as part of a team brie®ng session and this approach has been adopted in subsequent studies.The questionnaire covers eight domains relevant to safety performance(Table1). The allocation of items to domains was a matter of judgement but it was guided by the focus group discussions.Although these were largely non-directive,the groups were reminded at intervals of the need to consider a predetermined set of issues but also to allude to any issues not included in this underlying agenda.The domains were as fol-lows,together with the number of items included under each one.A number of items were considered relevant to more than one domain and were allocated accordingly: .con®dence in safety(21);.contractors(20);.job satisfaction(23);.participation(25);.risk(20).safety rules(16).stress(15);and.training(15)It may be noted that the domains of permit to work and design of plant included in the Sella®eld study(Lee,1998)were omitted.Two new domains of current inter-est,i.e.Stress and contractors were added.Con®dence in safety combines two of the domains included in the previous study.4.Results4.1.Factor analysisThe next stage was to carry out the form of factor analysis known as principal components analysis(PCA)of each domain,followed by Varimax Rotation of the emergent factors.The three or four factors accounting for the greatest amount of variance and with the highest Eigen values(minimum1.0)were extracted in each case.The rationale for this procedure is to identify groups of items that are closely correlated with each other and therefore demonstrably measuring the same under-lying component or dimension.This is a purely empirical process and the `meaning'of a factor is indicated by the wording of the contributing items.It is usual to distil this meaning into a single label.The choice of an appropriate label is a matter of judgement.The naming process allocates greater weight to the wording of those items that are most highly `loaded'on the factor.In case of doubt about the true meaning of a given factor,it is always possible to refer to the full set of items.Table 1Domains and factors Domain aFactors Alpha b Con®dence in safety Con®dence in control measures [1-Con]0.843KMO=0.869Con®dence in anticipation/response [2-Con]0.843Bart.=2563.117;P =0.0000Con®dence in reorganisation [3-Con]0.843Con®dence insafety standards [4-Con]0.843Contractors Company support for contractors [1-Ctr]0.762KMO=0.852Satisfaction with contractors'safety [2-Ctr]0.762Bart.=2074.781;P =0.0000Respect for contractors'role [3-Ctr]0.762Job satisfaction Contentment with the job [1-Job]0.847KMO=0.890Satisfaction with job relationships [2-Job]0.847Bart.=3779.122Interest in the job [3-Job]0.847P =0.0000Trust in colleagues [4-Job]0.847Participation Perceived empowerment [1-Par]0.808KMO=0.874Management's concern for safety [2-Par]0.808Bart.=5094.786;P =0.0000General morale [3-Par]0.808RiskOrganisational risk level [1-Ris]0.891KMO=0.796Personal risk taking [2-Ris]0.891Bart.=2987.841Risks of multi-skilling [3-Ris]0.891P =0.0000Risk versus productivity [4-Ris]0.891Safety rules Complexity of instructions [1-Saf]0.722KMO=0.785Hazard identi®cation/response [2-Saf]pro®ciency 0.722Bart.=2018.144Response to alarms [3-Saf]0.722P =0.0000Emergency procedures [4-Saf]0.722StressPersonal stress [1-Str]0.852KMO=0.791Job insecurity [2-Str]0.852Bart.=1379.175;P =0.0000Management's concern for health [3-Str]0.852Training/selection Quality of training induction [1-Tra]0.781KMO=0.830E ectiveness of sta selection [2-Tra]0.781Bart.=4443.021;P =0.0000General quality of training [3-Tra]0.781aKMO,Kaiser±Meyer±Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (acceptable at >0.500);BART,Bartlett's test of sphericity (acceptable at P <0.05).bCronbach's alpha is based on the number of items in a scale and the average of their intercorrelations.When calculating regression factor scores,as in the present case,all items in the relevant domain are included in each scale Ðthough di erentially weighted for each factor (Norusis,1994,pp.73±74).Hence,alpha is the same for all factors within a domain.68T.Lee,K.Harrison /Safety Science 34(2000)61±97T.Lee,K.Harrison/Safety Science34(2000)61±9769The factor loading is derived from a regression analysis and re¯ects the extent to which an item contributes to its factor.If the loading is high,the item is more typical of the overall meaning of the factor.It is useful to think of the loading as a form of correlation between the single item and the aggregate e ect of all the items.The results of factor analysis of the eight domains,together with their names and factor loadings are shown in Table1.Reliability co-e cients,Cronbach's alphas, which are generally satisfactory are also shown.The items in a selected four of the factors are shown in Table2as examples.It will be noted that factors within domains are completely independent,by virtue of the varimax rotation.However,the domains themselves are inter-correlated to varying degrees.An alternative approach considered was to process the entire data set of172items simultaneously and then to perform a secondary factor analysis.The choice was made empirically,based on the earlier Sella®eld data-set of5296(Lee, 1998).Using the`total'method,the emergent factors were less easily interpreted and substantially less valid when compared with the accident data.It appears that in performing data reduction procedures on172items,it is expedient where possible to ®rst separate the(obviously)`chalk'from the(obviously)`cheese'.After all,doubtful items can be included in more than one category so that their allocation is determined empirically.4.2.Factor scoresApproximately half of the items in the questionnaire are expressed negatively and half positively.Scales were reversed as necessary so that a high score equals a posi-tive orientation towards safety.Regression factor scores were next computed by adding an individual's score for each item in the factor,weighted by its factor coe cient.Factor scores are then standardised to a mean of0and a standard deviation of1(Norusis,1994).The e ect is to replace,for each respondent,the120`raw'scores by28factor scores based on groups of congruent items.The resulting scales,by virtue of their standardisation, are directly comparable.The total sample was included in the factor analysis.This was on the assumption that the close similarity in type of work and in safety management systems between the three stations would have resulted in a common underlying factor structure. Applying this structure,standardised factor scores(and norms for the industry) could be generated.This allows for con®dential self-assessment of current status and progress over time.In the present study,both raw and standardised scores were made available to each station,but the focus was on strengths and weaknesses,not on inter-station comparisons.4.3.Validation4.3.1.Correlation between attitudes and accident historyIt was demonstrated in the Sella®eld Study(Lee,1998)that there is a strong and positive relationship between negative expressions of attitude(or reported behaviour)。

基础语法翻译参考译文

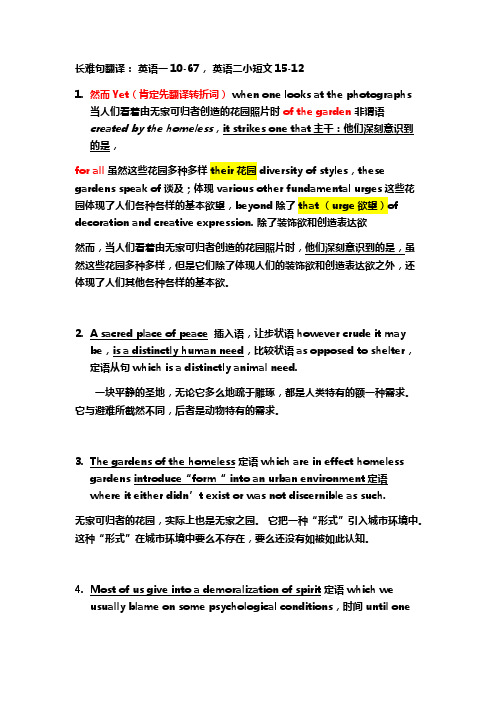

长难句翻译:英语一10-67,英语二小短文15-121.然而Yet(肯定先翻译转折词)when one looks at the photographs当人们看着由无家可归者创造的花园照片时of the garden非谓语created by the homeless,it strikes one that主干:他们深刻意识到的是,for all虽然这些花园多种多样their花园diversity of styles,these gardens speak of谈及;体现various other fundamental urges这些花园体现了人们各种各样的基本欲望,beyond除了that(urge欲望)of decoration and creative expression.除了装饰欲和创造表达欲然而,当人们看着由无家可归者创造的花园照片时,他们深刻意识到的是,虽然这些花园多种多样,但是它们除了体现人们的装饰欲和创造表达欲之外,还体现了人们其他各种各样的基本欲。

2.A sacred place of peace插入语,让步状语however crude it maybe,is a distinctly human need,比较状语as opposed to shelter,定语从句which is a distinctly animal need.一块平静的圣地,无论它多么地疏于雕琢,都是人类特有的额一种需求。

它与避难所截然不同,后者是动物特有的需求。

3.The gardens of the homeless定语which are in effect homelessgardens introduce“form“into an urban environment定语where it either didn’t exist or was not discernible as such.无家可归者的花园,实际上也是无家之园。

多元动机网格测验(MMG-S)中文版的修订报告

多元动机网格测验(MMG-S)中文版的修订报告焦璨;张敏强;吴利;纪薇【摘要】对Sokolowski等人编制的简版多元动机网格测验(MMG-S)作了中文版的修订.MMG-S的验证性因素分析表明:中文修订版MMG-S仍保持英文版的六因子结构,修订后六因子的α系数在0.70~0.84之间.中文修订版MMG-S具有良好的心理学测量指标,可用于测量企业管理人员的三种社会性动机.【期刊名称】《心理与行为研究》【年(卷),期】2010(008)001【总页数】5页(P49-53)【关键词】多元动机网格测验;成就动机;交往动机;权力动机【作者】焦璨;张敏强;吴利;纪薇【作者单位】深圳大学心理学系,深圳,518000;华南师范大学心理应用研究中心,广州,510631;华南师范大学心理应用研究中心,广州,510631;华南师范大学心理应用研究中心,广州,510631;华南师范大学心理应用研究中心,广州,510631【正文语种】中文【中图分类】B841.71 引言Murray界定了十多种社会性动机,研究与应用最多的三种社会性动机是:成就动机、权力动机与交往动机 [1]。

成就动机是人们希望从事对自己有重要意义的、有一定困难的、具有挑战性的活动,在活动中能取得优异结果和成绩,并能超过他人的动机;交往动机,也称亲和动机或合群动机,是在交往需要的基础上发展起来的一种重要的社会性动机;权力动机,也称影响力动机,是指人们具有的某种支配和影响他人以及周围环境的内在驱力 [2]。

社会性动机的传统测量方式有两种:一是美国心理学家Murray于1943年发展起来的主题统觉测验(thematic apperception test, TAT);二是自陈量表法,以爱德华个性偏好量表(edwards personal preference schedule,EPPS)等为代表。

这两种测量方法测量的是动机的不同方面 [3]:TAT测验测得的是内隐动机(implicit motivation),自陈量表测得的是外显动机(explicit motivation)。

1995—2005年英语专八翻译真题及答案

英语专业八级考试翻译部分历届试题及参考答案(1995-2005)1995 年英语专业八级考试--翻译部分参考译文C-E原文:简.奥斯丁的小说都是三五户人家居家度日,婚恋嫁娶的小事。

因此不少中国读者不理解她何以在西方享有那么高的声誉。

但一部小说开掘得深不深,艺术和思想是否有过人之处,的确不在题材大小。

有人把奥斯丁的作品比作越咀嚼越有味道的橄榄。

这不仅因为她的语言精彩,并曾对小说艺术的发展有创造性的贡献,也因为她的轻快活泼的叙述实际上并不那么浅白,那么透明。

史密斯夫人说过,女作家常常试图修正现存的价值秩序,改变人们对“重要”和“不重要”的看法。

也许奥斯丁的小说能教我们学会转换眼光和角度,明察到“小事”的叙述所涉及的那些不小的问题。

参考译文:However, subject matter is indeed not the decisive factor by which we judge a novel of its depth as well as (of ) its artistic appeal and ideological content (or: as to whether a novel digs deepor not or whether it excels in artistic appeal and ideological content). Some people compare Austen’s works to olives: the more you chew them, the more tasty (the tastier) they become. This comparison is based not only on (This is not only because of ) her expressive language and her creative contribution to the development of novel writing as an art, but also on (because of ) thefact that what hides behind her light and lively narrative is something implicit and opaque (not so explicit and transparent). Mrs. Smith once observed, women writers often sought (made attempts)to rectify the existing value concepts (orders) by changing people’s opinions on what is “important” and what is not.E-C原文I, by comparison, living in my overpriced city apartment, walking to work past putrid sacksof street garbage, paying usurious taxes to local and state governments I generally abhor, I amrated middle class. This causes me to wonder, do the measurement make sense? Are we measuring only that which is easily measured--- the numbers on the money chart --- and ignoring valuesmore central to the good life?For my sons there is of course the rural bounty of fresh-grown vegetables, line-caught fish and the shared riches of neighbours’ orchards an d gardens. There is the unpaid baby-sitter for whose children my daughter-in-law baby-sits in return, and neighbours who barter their skills and labour. But more than that, how do you measure serenity? Sense if self?I don’t want to idealize life in smal l places. There are times when the outside world intrudes brutally, as when the cost of gasoline goes up or developers cast their eyes on untouched farmland. There are cruelties, there is intolerance, there are all the many vices and meannesses in smallplaces that exist in large cities. Furthermore, it is harder to ignore them when they cannot bebanished psychologically to another part of town or excused as the whims of alien groups --- when they have to be acknowledged as “part of us.”Nor do I want to belittle the opportunities for small decencies in cities --- the eruptions ofone-stranger-to-another caring that always surprise and delight. But these are,sadly,more exceptions than rules and are often overwhelmed by the awful corruptions and dangers that surround us.参考译文:对我的几个儿子来说,乡村当然有充足的新鲜蔬菜,垂钓来的鱼,邻里菜园和果园里可供分享的丰盛瓜果。

Task-based language learning & teaching1 (2)

comment

If there is a lot of information t process, some of which is information organisation unclear, the task will be more amount of computation difficult; as it will be if the clarity of information given problem to be solved involves sufficiency of information given many elements and is inherently tricky.

the attentional resources of humans are limited and may need to be manipulated in the service of language acquisition

there are two modes of processing available to learners and that different effects result from their engagement: (see below) .

If the students have done a similar task before or if the information is already familiar and known to them, then the task will tend to be easier. If the task material is inherently structured- as e.g. in a simple story, then the task will be easier.

什么是创造力Creativity