front-matter

hexo的cover用法示例

hexo的cover用法示例Hexo是一个快速、简洁且高效的静态博客框架,可以帮助用户快速搭建个人博客。

在Hexo中,Cover是指博客文章的封面图像,是展示文章主题和内容的重要元素。

本文将介绍Hexo的Cover用法,并通过示例展示如何使用Cover来增加博客文章的吸引力。

在Hexo中,Cover可以在文章的Front-matter中进行设置。

Front-matter是指位于文章正文之前、用于定义文章元数据的区域。

在Front-matter中,可以使用cover 字段来设置文章的封面图像。

示例如下:```yamltitle: "使用Hexo的Cover功能"date: 2022-01-01cover: /images/cover.jpgcategories:- 技术tags:- Hexo- 博客```在上述示例中,cover字段的值为`/images/cover.jpg`,即指定了文章的封面图像为路径为`/images/cover.jpg`的图片。

用户可以根据自己的需求,指定任何有效的图像路径作为封面图像。

通过在文章的Front-matter中设置cover字段,Hexo会自动根据指定的封面图像路径,在博客主页和文章详情页中显示对应的封面图像。

在博客主页中,封面图像会作为文章的缩略图展示。

用户可以在配置文件`_config.yml`中的`index_generator`部分设置缩略图的大小和显示格式。

示例如下:```yamlindex_generator:path: blog/per_page: 10order_by: -datethumbnail_size:width: 300height: 200thumbnail_format: png```在上述示例中,设置了缩略图的宽度为300像素、高度为200像素,并将缩略图的格式设置为png。

在文章详情页中,封面图像会作为文章的头部图像展示。

Front Matter.

Vol.63April 2008No.2EditorC AMPBELL R.H ARVEY Duke UniversityCo-EditorJ OHN G RAHAM Duke UniversityAssociate EditorsA NAT R.A DMATI Stanford University Y ACINE A¨ıT -S AHAUA Princeton University A NDREW A NGColumbia University K ERRY B ACKTexas A&M University M ALCOLM B AKER Harvard University G EERT B EKAERT Columbia University J ONATHAN B ERKUniversity of California,BerkeleyH ENDRIK B ESSEMBINDER University of Utah M ICHAEL W .B RANDT Duke University A LON B RAV Duke University M ARKUS K.B RUNNERMEIER Princeton UniversityD AVID A.C HAPMAN Boston CollegeJ ENNIFER S.C ONRADUniversity of North Carolina,Chapel HillF RANCESCA C ORNELLI London Business School B ERNARD D UMASUniversity of Lausanne P AUL A.G OMPERS Harvard UniversityM ARK G RINBLATTUniversity of California at Los AngelesD AVID H IRSHLEIFERUniversity of California,Irvine B URTON H OUIFIELDCarnegie Mellon UniversityH ARRISON H ONG Princeton University N ARASIMHAN J EGADEESHEmory University S TEVEN K APLANUniversity of Chicago G.A NDREW K AROLYI Ohio State UniversityA RVIND K RISHNAMURTHY Northwestern University M ICHAEL L EMMON University of UtahF RANCIS L ONGSTAFFUniversity of California,Los AngelesA NDREW M ETRICK Yale University D AVID M USTOUniversity of Pennsylvania T ERRANCE O DEANUniversity of California,Berkeley C HRISTINE P ARLOURUniversity of California,BerkeleyˇLUBO ˇS P ´A STOR University of Chicago L ASSE H EJE P EDERSEN New York University M ITCHELL A.P ETERSEN Northwestern UniversityM ANJU P URI Duke University R AGHURAM R AJAN University of ChicagoA NTOINETTE S CHOARMassachusetts Institute of TechnologyD UANE J.S EPPICarnegie Mellon University H ENRI S ERVAESLondon Business School A NIL S HIVDASANIUniversity of North Carolina R ICHARD S TANTONUniversity of California,BerkeleyA NDREW W INTONUniversity of MinnesotaBusiness ManagerD AVID H.P YLEUniversity of California,BerkeleyEditor’s StaffW ENDY W ASHBURNHELP DESKThe Latest InformationOur World Wide Web SiteFor the latest information about the journal,about our annual meeting,or about other announcements of interest to our membership,consult our web site atSubscription Questions or ProblemsAddress ChangesBlackwell Publishing800-835-6770US(toll free)350Main Street+441865251866ROWMalden,MA02148781-388-8232fax or+441865381393USA or9600Garsington Road,email:subscrip@ Oxford OX42DQ,EnglandPermissions to Reprint Materials from the Journal of FinanceC 2008The American Finance Association.All rights reserved.With the exceptionof fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study,or criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced,stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder.Authorization to photocopy items for internal and personal use is granted by the copyright holder for libraries and other users of the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC),222Rosewood Drive,Danvers,MA01923,USA(),provided the appropriate fee is paid directly to the CCC.This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying,such as copying for general distribution for advertising or promotional purposes,for creating new collective works or for resale.For information regarding reproduction for classroom use,please see the AFA policy statement in the back of this issue.Email UpdatesSign up to receive Blackwell Synergy free e-mail alerts withcomplete Journal of Finance tables of contents and quick links to article abstracts from the most current issue.Simply go to www.blackwell-synergy.com,select the journal from the list of journals,and click on“Sign-up”for FREE email table of contents alerts.Advertising in the JournalFor advertising information,please visit the journal’s web site at or contact the Academic and Science,Advertising Sales Coordinator,at journaladsUSA@ .350Main St.Malden,MA02148.Phone:781.388.8532, Fax:781.338.8532.Association BusinessThose having business with the American Finance Association,or members wishing to volunteer their service or ideas that the association might develop,should contact the Executive Secretary and Treasurer:Prof.David Pyle,American Finance Asso-ciation,University of California,Berkeley—Haas School of Business,545Student Services Building,Berkeley,CA94720-1900.Email:pyle@ANNOUNCEMENT OF2007SMITH BREEDEN PRIZESAND BRATTLE AWARDS (v)ARTICLESWhich Shorts Are Informed?E KKEHART B OEHMER,C HARLES M.J ONES,and X IAOYAN Z HANG (491)An Empirical Analysis of the Pricing of CollateralizedDebt ObligationsF RANCIS A.L ONGSTAFF and A RVIND R AJAN (529)Do Bankruptcy Codes Matter?A Study of Defaults in France,Germany,and the U.K.S ERGEI A.D AVYDENKO and J ULIAN R.F RANKS (565)Empirical Evidence of Risk Shifting in Financially Distressed FirmsA SSAF E ISDORFER (609)Information Sales and Insider Trading with Long-Lived InformationG IOVANNI C ESPA (639)The Industry Life Cycle,Acquisitions and Investment:Does Firm Organization Matter?V OJISLAV M AKSIMOVIC and G ORDON P HILLIPS (673)Capital Gains Taxes and Asset Prices:Capitalization or Lock-in?Z HONGLAN D AI,E DWARD M AYDEW,D OUGLAS A.S HACKELFORD,and H AROLD H.Z HANG (709)Identification of Maximal Affine Term Structure ModelsP IERRE C OLLIN-D UFRESNE,R OBERT S.G OLDSTEIN,and C HRISTOPHER S.J ONES (743)The Term Structure of Real Rates and Expected InflationA NDREW A NG,G EERT B EKAERT,and M IN W EI (797)Competition from Specialized Firms and the Diversification–Performance LinkageJ UAN S ANTALO and M ANUEL B ECERRA (851)Correlated Trading and ReturnsD ANIEL D ORN,G UR H UBERMAN,and P AUL S ENGMUELLER (885)Share Issuance and Cross-sectional ReturnsJ EFFREY P ONTIFF and A RTEMIZA W OODGATE (921)Earnings Management and Firm Performance FollowingOpen-Market RepurchasesG UOJIN G ONG,H ENOCK L OUIS,and A MY X.S UN (947)Underreaction to Dividend Reductions and Omissions?Y I L IU,S AMUEL H.S ZEWCZYK,and Z AHER Z ANTOUT (987)MISCELLANEA (1021)。

新时代核心英语教程写作3教学课件(U11)

Locating and evaluating material

Locating and evaluating material

Generally, this step comprises the following two sub-steps. 1. locating: finding the most promising sources 2. evaluating: evaluating the sources to

2. Databases such as China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) list titles of articles as well as full text material which you can easily access.

What is behind U.K. occupation and governance diplomacy after World War II

Activity 1

Narrow down the following broad topics to proper ones that are fit for research papers of about 2,000 words.

determine which ones are genuinely useful, and eliminating those that are out-of-date, unreliable, or less relevant

Locate material

1. The library is usually your first choice when you look for sources.

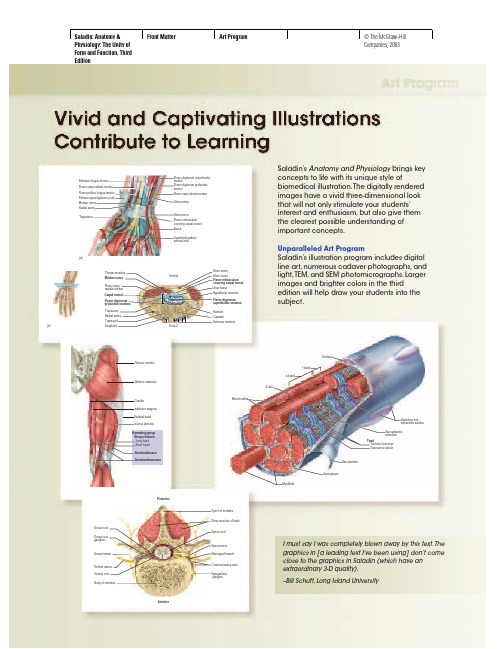

Front Matter Art Program

Saladin’s Anatomy and Physiology brings key concepts to life with its unique style ofbiomedical illustration.The digitally rendered images have a vivid three-dimensional look that will not only stimulate your students’interest and enthusiasm,but also give them the clearest possible understanding of important concepts.Unparalleled Art ProgramSaladin’s illustration program includes digital line art,numerous cadaver photographs,and light,TEM,and SEM rger images and brighter colors in the thirdedition will help draw your students into the subject.I must say I was completely blown away by this text.The graphics in [a leading text I’ve been using] don’t come close to the graphics in Saladin (which have an extraordinary 3-D quality).–Bill Schutt,Long Island UniversityPalmaris longus tendon Median nerve Radial artery Flexor carpi radialis tendon Flexor pollicis longus tendon BursaFlexor retinaculum covering carpal tunnel Trapezium(a)(b)Flexor digitorum profundus tendonFlexor digitorum superficialis tendonUlnar nerveFlexor carpi ulnaris tendon Superficial palmar arterial archUlnar arteryPalmar carpal ligament (cut)Flexor retinaculum covering carpal tunnel Median nerve Carpal tunnel Flexor digitorum profundus tendons Flexor digitorum superficialis tendons Ulnar bursa Radial artery Hamate Trapezium ScaphoidCapitateTrapezoidThenar muscles Hypothenar muscles Ulnar arteryUlnar nerveFlexor carpi radialis tendon Extensor tendonsVentralDorsal Gluteus mediusGluteus maximusIliotibial band Long head Short head Biceps femoris Hamstring group Semitendinosus SemimembranosusAdductor magnus GracilisVastus lateralis Ventral root Dorsal rootSpinal nerveDorsal root ganglionSympathetic ganglionCommunicating rami Dorsal ramusVentral ramus Meningeal branchBody of vertebraAnteriorPosteriorSpine of vertebraDeep muscles of backSpinal cordSarcoplasmSarcolemmaOpenings into transverse tubulesSarcoplasmic reticulumMitochondriaMyofibrilsA bandI bandZ discNucleusTriadTerminal cisternae Transverse tubulexx PrefaceThe art program in Saladin’s text is superb.Students today are more “picture oriented”and gain much of their information from the figures rather than from the text material.The figures in Saladin are clearly and accurately presented.W.Walther,Lake Erie CollegeAbductor digiti minimi(a)(c)(d)(e)(b)Flexor digiti minimi brevis Abductor hallucis Flexor digitorum brevisCalcaneusPlantar fascia (cut)Abductor hallucis (cut)LumbricalsFlexor hallucis longus tendon Flexor digitorum longus tendon Flexor digitorum brevis (cut)Quadratus plantaeFlexor digiti minimi brevisQuadratus plantae (cut)Adductor hallucisFlexor hallucis brevis Flexor digitorum longus tendon (cut)Flexor hallucis longus tendon (cut)Abductor hallucis (cut)Plantar viewDorsal viewDorsalinterosseousPlantarinterosseousInner medullaOuter medullaCortex(b)(c)Arcuate vein Arcuate arteryVasa recta Ascending limbDescending limb Nephron loopCollecting duct Cortical nephron Juxtamedullary nephron Glomerular capsule Glomerulus Proximal convoluted tubule Distalconvoluted tubuleEfferent arteriole Afferent arterioleInterlobular veinInterlobular artery Juxtaglomerular apparatusRenal corpusclePeritubular capillariesCorticomedullary junctionThick segment Thin segmentM e d u l l aC o r t e xRenal capsuleCollecting ductMinor calyxNephronRenal cortexRenal medulla(a)Renal papillaMyelin Motor nerve fiber Axon terminal Schwann cellSynaptic vesicles (containing ACh)Basal lamina(containing AChE)Sarcolemma Region of sarcolemmawith ACh receptorsJunctional foldsNucleus of muscle fiberSynaptic cleftLungsHeart Thoracic vertebra Sternum 2nd rib (a)(b)(c)SternumDiaphragmSuperior vena cava Right lungAorta Parietal pleura (cut) Pulmonary trunkParietal pericardium (cut)Apex of heartDiaphragmAtlas Quality Cadaver ImagesColor photographs of cadavers dissected specifically for this book allow students to see the real texture of organs and theirrelationships to each other.This anatomical realism combines with the simplified clarity of line art to give your students a holistic view of bodily structure.The cadaver photos are excellent! My students(and friends who have taught or taken anatomy class)love them.–Michael Angilletta,Jr.,Indiana State University,Terre HauteStudents have liked the excellent artwork,the charts and tables,and the clinical insights.The photographs of cadaver dissections and the electron microscopy are excellent.- Robert Moldenhauer,St.Clair County Community CollegeFrontalis Orbicularis oculiProcerus Nasalis Parotid salivary gland Zygomaticus major Levator labii superioris Orbicularis orisMasseter PlatysmaSternocleidomastoidDepressor anguli oris Depressor labii inferioris Cranial nervesFibers of olfactory nerve (I)Optic nerve (II)Trochlear nerve (IV)Trigeminal nerve (V)Abducens nerve (VI)Facial nerve (VII)Vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII)Glossopharyngeal nerve (IX)Accessory nerve (XI)Hypoglossal nerve (XII)Vagus nerve (X)Oculomotor nerve (III)Frontal lobeOlfactory bulb Olfactory tract Temporal lobe InfundibulumMedullaCerebellum(a)Optic chiasma (b)Longitudinal fissure Frontal lobe Temporal lobe PonsMedulla oblongata Spinal cordCerebellumOlfactory bulb(from olfactory n., I)Cranial nerves Olfactory tractOptic n. (II)Optic chiasma Optic tract Oculomotor n. (III)Trochlear n. (IV)Trigeminal n. (V)Abducens n. (VI)Facial n. (VII)Vestibulocochlear n. (VIII)Vagus n. (X)Glossopharyngeal n. (IX)Accessory n. (XI)Hypoglossal n. (XII)TrapeziusErector spinae:Spinalis thoracis Iliocostalis thoracis Longissimus thoracisRibsExternal intercostalsIliocostalis lumborum Latissimus dorsiThoracolumbar fasciaPhysiology Focused ArtSaladin illustrates many difficult physiological concepts in steps that students find easy to follow.For students who are "visual learners," illustrations like these teach more than a thousand words.One of the major strengths of the Saladin text,one that promoted me to adopt the text,was the quality and quantity of the illustrations.In my view,this text is a hands-down winner in this area.R.Symmons,California State University at HaywardErythropoiesis inred bone marrowErythrocytescirculate for 120 daysExpired erythrocytesbreak up in liver and spleenSmall intestineCell fragmentsphagocytizedGlobinHemoglobindegradedHydrolyzed to freeamino acidsHemeIronBiliverdinBilirubinBileFecesStorage Reuse Loss bymenstruation,injury, etc.NutrientabsorptionAmino acidsIronFolic acidVitamin B12Lymph absorbschylomicrons from small intestineLymph drainsinto bloodstreamLipoprotein lipaseremoves lipidsfrom chylomicronsLiver disposesof chylomicronremnantsLiverproducesVLDLsLeaves LDLs containingmainly cholesterolCells requiringcholesterol absorb LDLsby receptor-mediatedendocytosisTriglycerides are removedand stored in adipocytesLipids are stored inadipocytes or usedby other cellsLiver producesempty HDL shellsHDL shells pickup cholesterol andphospholipidsfrom tissuesFilled HDLsreturn to liverLiver excretescholesterol asbile saltsChylomicron pathway VLDL/LDLpathwayHDLpathwayMore salt is continually added by the PCT.The higher the osmolarity of the ECF, the more water leaves the descending limb by osmosis.The more water that leaves the descending limb, the saltier the fluid is that remains in the tubule.The more salt that is pumpedout of the ascending limb, thesaltier the ECF is in therenal medulla.The saltier the fluid in theascending limb, the moresalt the tubule pumps intothe ECF.H2O3004002001001,200700900400600Na+K+Cl–Na+K+Cl–Na+K+Cl–Na+K+Cl–Na+K+Cl–Na+K+Cl–H2OH2OH2OH2OMicrographsAll life processes are ultimately cellular processes.Saladin drives this point home with a variety of histological micrographs in LM,SEM,and TEM formats,including many colorized electron micrographs.Photomicrographs Correlated with Line ArtSaladin juxtaposes histological photomicrographs with line art.Much like the combination of cadaver gross photographs and line art,this gives students the best of both perspectives:the realism of photos and the explanatory clarity of line drawings.From Macroscopic to MicroscopicSaladin’s line art guides students from the intuitive level of gross anatomy to the functional foundations revealed by microscopic anatomy.The artwork in Saladin is one of its major strengths.I applaud this;it really seems to help hold the interest of a wide variety of students.D.Farrington,Russell Sage CollegeLeft pulmonary artery Two lobar arteries to left lungLeft pulmonary veins Left atrium Left ventricleRight atrium Right pulmonary veins Right pulmonary arteryThree lobararteries to right lung Right ventriclePulmonary trunk Aortic archPulmonary vein (to left atrium)Pulmonary artery (from right ventricle)Alveolar sacs and alveoli(b)(a)Zone of cell proliferationZone of cell hypertrophyZone of calcificationZone of bone depositionMultiplying chondrocytes Enlarged chondrocytes Breakdown of cartilage lacunae Osteoblasts depositing bone matrixOsteocytesBone marrowTrabecula of spongy boneCalcifying cartilage CiliaGoblet cellSquamous epithelial cellsNuclei of smooth muscle (b)CortexLymphatic nodule Germinal center Subcapsular sinusArtery CapsuleVeinHilumMedullaMedullary cordMedullary sinus Lymphocytes VenuleTrabeculaMacrophage Medullary cords Medullary sinus Reticular fibers Efferent lymphatic vesselAfferent lymphatic vessel ValveTrabecula(b)(a)LymphocytesReticular fibers(c)Macrophage。

front-matter

I I

I

ut: LIL,.[LL~

New Paradigms for Self-Assembly in Science and Technology K~e Larsson Festschrift Guest Editors: B. Lindman and B. W. Ninham (Lund) This volume includes a number of selected papers of the international conference "Colloidal Aspects of Lipids", held in June 1997 at Lund, Sweden. In conjunction with the conference Professor K~re Larsson, well-known and respected as a leading scientist in this field during the decades, was honored.

Springer Friiher Schriftenreihe Reihe Progress in colloid & polymer science zu: Colloid & polymer science Vol, 108. The colloid science of lipids. 1998 The colloid science of lipids ; new paradigms for self assembly in science and technology ; Khre-Larsson-Festschrift / guest eds.: B. Lindmann und B. W. Ninham. - Darmstadt : Steinkopff New York : Springer, 1998 (Progress in colloid & polymer science ; Vol. 108) ISBN 3-7985-1112-8

obsidian frontmatter 语法

obsidian frontmatter 语法Obsidian frontmatter是一种在Obsidian笔记应用中使用的语法结构,用于在笔记文件的开头定义元数据或配置。

它通常被放置在Markdown文件的最前面,用三个短破折号(---)包围起来。

以下是Obsidian frontmatter的语法规则和示例:1. 使用三个短破折号将frontmatter分隔开,如下所示:```---frontmatter内容---```2. frontmatter内容是键值对的形式,使用YAML(YAMLAin't Markup Language)语法。

键和值之间使用冒号(:)分隔,键值对之间使用换行分隔。

例如:```---title: Example Notedate: 2022-01-01tags:- 个人- 笔记---```3. frontmatter可以包含任意数量和类型的键值对。

你可以自定义键名和对应的值,以满足你的需要。

4. 你可以在frontmatter中使用变量来代表一些动态信息。

例如,可以使用`{{date}}`来表示当前日期。

示例:```---title: Example Notedate: {{date}}---```5. frontmatter的内容对于Obsidian是可见的,但在渲染Markdown文件时会被忽略,不会显示在预览或导出的结果中。

通过使用Obsidian frontmatter语法,你可以在笔记文件中定义和管理一些元数据,如标题、日期、标签等,以及其他自定义信息。

这对于组织和搜索笔记非常有帮助。

论文结构及各部分的写作要求

毕业论文的结构1.前置部分(Front Matter):中文封面(Cover, in Chinese)英文题名页(Title Page, in English)郑重声明论文使用授权说明目录(Contents)英文摘要、关键词页(Abstract and Key Words, in English)中文摘要、关键词页(Abstract and Key Words, in Chinese)2.正文部分(Body):引言(Introduction)主体(Body)结论(Conclusion)3.文尾部分(Back Matter):参考文献(Works Cited)致谢(Acknowledgements)附录(Appendix)封底(Back Cover)论文标题1. 论文的标题应具备以下特征:1)准确。

要做到“题与文相符”,概括文章的基本内容,揭示文章的主题。

2)醒目。

要引人注目,给人留下深刻印象。

3)新颖。

要有新鲜感。

只有作者的思想新颖,论题才能富有新意。

4)简洁。

要具有高度的概括性。

字数限制在20个字以内(一般不超过10个实词)。

5)具体。

要具体地表达出论文的观点,切忌空泛而谈。

2. 英文标题四种结构1)名词性词组(包括动名词) Sister Carrie’s Broken Dream2)介词词组On the theme of Young Goodman Brown by Hawthorne3)名词词组+介词词组A comparison between a Teacher-Centered Class and aStudents-Centered Class4)疑问式How to Use a Computer in Managing an English Class (学术论文不建议使用此标题方式)有的标题由两部分组成,用冒号( :)隔开。

一般来说,冒号前面一部分是主标题,提出文章中心或主旨。

冒号后面是副标题,补充说明主标题的内容,如研究重点或研究方法。

texstudio中frontmatter用法

texstudio中frontmatter用法在TexStudio中,我们可以使用frontmatter来定义文档的前言部分。

frontmatter 是一个在主文档开始前定义的区域,在其中可以包含一些与文档格式和结构有关的设置和命令。

首先,我们需要在TexStudio中创建一个新的TEX文件。

在文件的开头,我们可以使用frontmatter命令来定义frontmatter区域。

例如:```\begin{frontmatter}% 在这里插入前言内容和设置\end{frontmatter}```frontmatter区域中可以包含一些常用的设置,比如文档标题、作者、日期等。

我们可以使用相应的命令来定义这些内容。

例如:```\title{我的文档标题}\author{作者}\date{\today}```在frontmatter区域中,我们还可以定义一些特殊的设置,比如文档类型、页眉页脚样式等。

这些设置使用特定的命令进行定义。

例如,可以使用以下命令定义文档类型为book:```\documentclass{book}```使用以下命令定义页眉页脚样式为fancy:```\usepackage{fancyhdr}```除了设置和命令,frontmatter区域还可以包含一些其他的内容,比如摘要、目录等。

我们可以使用相应的命令来插入这些内容。

例如,可以使用以下命令插入摘要:```\begin{abstract}这是摘要内容。

\end{abstract}```最后,在frontmatter区域的末尾,我们需要使用\maketitle命令来生成整个前言部分的内容。

例如:```\maketitle```以上就是在TexStudio中使用frontmatter的基本用法。

通过定义frontmatter区域,我们可以方便地对文档的前言部分进行设置和格式化,从而使整个文档更具有结构性和专业性。

yaml front matter语法

标题:深度解析yaml front matter语法一、引言在编写文章或博客时,我们经常会在文章的开头看到一段被称为“yaml front matter”的内容。

这段内容通常包含了一些元数据,比如文章的标题、作者、发布时间等信息。

本文将深入探讨yaml front matter的语法和使用方法。

二、yaml front matter的基本语法yaml front matter通常使用YAML(YAML Ain't Markup Language)格式来书写。

它位于文章的起始部分,用三个破折号(---)包裹起来。

以下是一个简单的yaml front matter示例:```---title: "文章标题"author: "作者名"date: 2022-01-01categories:- 技术- 编程tags:- YAML---```在上面的示例中,title、author、date、categories和tags就是yaml front matter中的元数据字段,它们的值使用冒号(:)进行键值对的表示。

另外,categories和tags字段的值是一个列表,使用短横线(-)进行表示。

三、yaml front matter的高级语法除了基本的元数据字段外,yaml front matter还可以包含一些高级的语法,比如嵌套结构、引用、复杂数据类型等。

例如:```---title: "文章标题"author: "作者名"date: 2022-01-01tags: &tags- YAML- 文章categories:- 技术references: *tags---```在上面的示例中,我们使用了引用符号(&和*)来定义和引用一个tags字段的取值,这样就可以避免重复输入同样的数值。

这种做法在管理大量文章或博客时尤其有用,可以提高编辑效率。

0-front-matter

Microfacies of Carbonate RocksErik Fl¨ugel Microfaciesof Carbonate Rocks Analysis,Interpretationand ApplicationSecond EditionWith a contribution by Axel Munnecke 123ISBN978-3-642-03795-5e-ISBN978-3-642-03796-2DOI10.1007/10.1007/978-3-642-03796-2Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New YorkLibrary of Congress Control Number:2009935385c Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg2010This work is subject to copyright.All rights are reserved,whether the whole or part of the material is concerned,specifically the rights of translation,reprinting,reuse of illustrations,recitation,broadcasting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way,and storage in data banks.Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September9,1965, in its current version,and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer.Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law.The use of general descriptive names,registered names,trademarks,etc.in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement,that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.Camera-ready by Erentraud Fl¨u gel-Kahler,ErlangenCover design:WMXDesign,HeidelbergPrinted on acid-free paperSpringer is part of Springer Science+Business Media()Preface to the Second EditionA second editon of this book - yes or no - or not yet? Are changes necessary or would it be enough if minor errors in the text were corrected?So I asked for help and I got answers from friends and colleagues. I wish to thank W.Ch. Dullo (Kiel), A. Freiwald (Erlangen), H.-G. Herbig (Cologne), W. Piller (Graz), W. Schlager (Amsterdam), R. J. Stanton (Thousand Oaks, USA) for their excellent and friendly advice.They were in agreement that not enough has changed in the scientific field of ‘Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks’since 2004 when the first edition was published for a new edition to be necessary, but they all believed that an update of the references on the CD going with the volume would be useful.Therefore, the reference section has been updated to April 2009. Most of the new references are since 2002, but a few are earlier. The reference file now contains more than 16,000 references. In connection with the keywords used throughout the book these references can help the reader locate special subjects or overviews of interest.When Erik wrote this book during his last years, his primary goal was to provide students and all those interested in and working with microfacies a helpful und useful resource that contained many plates and figures.Most of the pictures in this book were collected during Erik Flügel’s scientific work, some are from papers that were published in the journal Facies, then published by the Institute of Paleontology (now Geo-zentrum Nordbayern), University Erlangen-Nürnberg, and last not least, some were graciously provided by col-leagues.The author had hoped to include an additional chapter with plates that would provide the reader with an expanded range of information about microfacies. This task has been accomplished by A. Munnecke (Erlangen). Chapter 20 contains plates and figures that have been used successfully in the Course on Micro-facies held every year or two at the University in Erlangen.I wish to thank all of my colleagues at the institute in Erlangen, and especially A. Munnecke for the compilation of Chapter 20.Ch. Schulbert was most helpful in solving software problems with the text and CD.I thank Ch. Bendall (Springer Verlag Heidelberg) for overseeing the printing of this new edition. Erlangen, June 2009Erentraud Flügel-KahlerPrefaceThe objective of this book is to provide a synthesis of the methods used in microfacies studies of carbonate rocks and to show how the application of microfacies studies has contributed to new developments in car-bonate geology. In contrast with other textbooks on car-bonate sedimentology this book focuses on those com-positional and textural constituents of carbonates that reflect the depositional and diagenetic history and de-termine the practical usefulness of carbonate rocks.The chapters are written in such a way, that each one can be used as text in upper level undergraduate and graduate courses. The topics of the book also ap-ply to research workers and exploration geologists, looking for current information on developments in the use of microfacies analysis.Since microfacies studies are based on thin sections, instructive plates showing thin-section photographs ac-companied by thorough and detailed explanations form a central part of this book. All plates in the book con-tain a short summary of the topic. An –> sign leads the reader to the figures on the plate. The description of the microphotographs are printed in a smaller type. Care has been taken to add arrows and/or letters (usually the initials of the subject) so that the maximum informa-tion can be extracted from the figures.Rather than being a revised version of ‘Microfacies Analysis of Limestones’ (Flügel 1982) ‘Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks’ is a new book, based on a new con-cept and offering practical advice on the description and interpretation of microfacies data as well as the application of these data to basin analysis. Microfacies analysis has the advantages over traditional sedimen-tological approaches of being interdisciplinary, and in-tegrating sedimentological, paleontological and geo-chemical aspects.‘Microfacies of Carbonate Rocks’:•analyses both the depositional and the diagenetic his-tory of carbonate rocks,•describes carbonate sedimentation in various ma-rine and non-marine environments, and considers both tropical warm-water carbonates and non-tropi-cal cool-water carbonates,•presents diagnostic features and highlights the sig-nificance of microfacies criteria,•stresses the biological controls of carbonate sedi-mentation and provides an overview on the most common fossils found in thin sections of limestones,• discusses the relationships between diagenetic pro-cesses, porosity and dolomitization,•demonstrates the importance of microfacies for es-tablishing and evaluating sequence stratigraphic frameworks and depositional models,•underlines the potential of microfacies in differenti-ating paleoclimate changes and tracing platform-ba-sin relationships, and•demonstrates the value of microfacies analysis in evaluating reservoir rocks and limestone resources, as well as its usefulness in archaeological prov-enance studies.Structure of the BookMicrofacies of Carbonate Rocks starts with and in-troductory chaper (Chap.1) and an overview of mod-ern carbonate deposition (Chap. 2) followed by 17 chap-ters that have been grouped into 3 major parts. Microfacies Analysis (Chap. 3 to Chap. 10) summa-rizes the methods used in microfacies studies followed by discussions on descriptive modes and the implica-tions of qualitative and quantitative thin-section crite-ria.Microfacies Interpretation (Chap. 11 to Chap. 16) demonstrates the significance of microfacies studies in evaluating paleoenvironment and depositional sys-tems and, finally,Practical Use of Microfacies (Chap. 17 to Chap. 19) demonstrates the importance of applied microfacies studies in geological exploration for hydrocarbons and ores, provides examples of the relationships between carbonate rock resources and their facies and physical properties, and also illustrates the value of microfacies studies to archaeologists.Important references are listed at the end of chap-ters or sections under the heading ‘Basics’. The codeV I I Inumbers K... are keywords leading to references on specific fields of interest (see CD), e.g. K021 (cold-water carbonates), K078 (micrite), or K200 (hydrocar-bon reservoir rocks).The book is also accompanied by a CD containing •an alphabetical list of about 16,000 references (updated in this version up to April 2009) on carbonate rocks (see also Appendix) as word document,and•visual comparison charts for percentage estimation.Synopsis of the Book‘s ContentsChapter 1: New Perspectives in Microfacies. Micro-facies studies, which were originally restricted to the scale of thin sections, provide an invaluable source of information on the depositional constraints and envi-ronmental controls of carbonates, as well as on the prop-erties of carbonate rocks. Microfacies studies assist in understanding sequence stratigraphic patterns and are of economic importance both in reservoir studies and in the evaluation of limestone resources.Chapter 2: Modern Depositional Environments. Knowl-edge of modern carbonates is a prerequisite for under-standing ancient carbonate rocks. Modern carbonates are formed both on land and in the sea, in shallow- and in deep marine settings, and in tropical and non-tropi-cal regions, but the present is only part a key to the Past.Microfacies AnalysisChapter 3: Methodology. Which methods can be used in the field? Which sampling strategy should be ap-plied and how many samples are required? Which labo-ratory techniques are useful in microfacies analysis? Which other techniques should be combined with microfacies studies?Chapter 4: Microfacies Data: Matrix and Grains. This chapter offers practical advice on how to handle micro-facies data, and deals with how to describe and inter-pret thin-section characteristics. Matrix types and grain categories are discussed with regard to their diagnostic criteria, origin and significance.Chapter 5: Microfacies Data: Fabrics. Typical deposi-tional and diagenetic fabrics in limestones reflect the history of the rock. Microfacies criteria indicating breaks and changes in sedimentation (discontinuity sur-faces) are of specific interest in refining sequence strati-graphic boundaries. Variously sized fissures, micro-cracks and breccias can be used in deciphering syn-and post-depositional destructive processes.Chapter 6: Quantitative Microfacies Analysis. Whilst previous chapters focused on qualitative criteria this chapter deals with quantitative data including grain size analysis, frequency analysis and multivariate studies. Constituent analysis and the distribution patterns of spe-cific grain types are valuable tools in the reconstruc-tion of paleoenvironmental controls and depositional settings.Chapter 7: Diagenesis, Porosity and Dolomitization. Understanding diagenetic processes and their products is of high economic importance. The diagenetic micro-facies of a rock reflects changes in the course of its lithification history. The main topics discussed in this chapter are porosity types, carbonate cements, diage-netic textures including compaction and pressure solu-tion, and dolomitization/dedolomitization and dolomite textures. The last part of the chapter deals with thin-section criteria for metamorphic carbonates and marbles.Chapter 8: Classification – chosing a name for your sample. A classification is simply a tool for organizing information, and should not be the only source of con-clusions. Whilst a name based on texture and compo-sition can not replace a well-defined microfacies type, rock names are essential for the categorization of samples. Textural classifications proposed by Dunham and by Folk have proven to be the most practical. Spe-cific concepts must be adhered to in the naming of reef limestones, non-marine carbonates, recrystallized car-bonates rocks and mixed siliciclastic-carbonate rocks. Chapter 9: Limestones are Biological Sediments. In contrast to siliciclastic rocks, both the formation and the destruction of most limestones is directly or indi-rectly influenced and controlled by biological pro-cesses. This chapter stresses the biological controls on carbonate sedimentation. Microbes, encrusting organ-isms, and macro- and microborers can yield useful in-formation on paleoenvironment, depositional con-straints and carbonate production.Chapter 10: Fossils in Thin Sections. It Is Not That Difficult. The recognition of fossils in thin sections is not so difficult once the diagnostic criteria for the main groups have been understood, particularly for algae and foraminifera, sessile invertebrates, and organisms with shells. This chapter provides an overview of the most common fossils found in thin sections of limestones. The text concentrates on identification criteria, envi-ronmental and temporal distribution, and on the sig-nificance of the fossils. Numerous instructive plates are included to aid in the recognition and differentia-tion skeletal grains in thin sections.PrefaceMicrofacies InterpretationChapter 11: Summarizing Microfacies Criteria: Micro-facies Types. How can microfacies data be combined in sensitive and practicable microfacies types? Which criteria should be used, which grain types are of par-ticular importance and, how many microfacies types are reliable? The creation of microfacies types is illus-trated by means of examples.Chapter 12: Recognizing Paleoenvironmental Condi-tions. Carbonate sediments are particularly sensitive to environmental changes. Microfacies and organisms are excellent paleoenvironmental proxies as they re-flect hydrodynamic conditions, the impact of storms, substrate conditions, light, oxygenation, seawater tem-perature and salinity. Significant differences between the compositions of skeletal grain associations for warm-water and cold-water carbonates provide a use-ful tool for estimating paleoclimatic changes. How deep was the sea? Microfacies studies provide an answer. Chapter 13: Integrated Facies Analysis. Understand-ing the formation and diagenesis of carbonate rocks requires the combination of microfacies with mineral-ogical and geochemical data. The chapter deals with acid-insoluble residues and authigenic minerals in car-bonate rocks, discusses the value of minor elements and stable isotopes in tracing the depositional and di-agenetic history of limestones, and deals with the po-tential of organic matter in carbonate rocks for facies analysis.Chapter 14: Depositional Models, Facies Zones and Standard Microfacies. Microfacies are essential for de-fining depositional models and recognizing facies zones. Facies models assist in understanding deposi-tional history. Changes in sedimentological and bio-logical criteria across shelf-slope-basin transects form the basis of generalized models for carbonate platforms, ramps and shelves. Facies belts are reflected by their biotic zonation patterns and the distribution of Stan-dard Microfacies Types (SMF Types). The latter are virtual categories that summarize microfacies with iden-tical criteria. Which criteria are used in differentiating the SMF Types of platform and ramp carbonates? What are the problems involved in the SMF concept? Re-vised and refined SMF types are a meaningful tool in tracing facies belts, but must be used with care. Com-mon microfacies of carbonate ramps (Ramp Micro-facies Types) show only partial correspondence to the SMF Types of rimmed platforms.Chapter 15: Basin Analysis: Recognizing Depositional Settings. Which diagnostic criteria characterize lime-stones of different carbonate systems? Case studies for non-marine and marine carbonate rocks demonstrate how to translate microfacies into ancient depositional settings. Non-marine settings can be successfully re-constructed for pedogenic carbonates, paleokarst de-posits and ancient speleothems, travertine deposits, and lacustrine carbonates, these can be characterized by spe-cific microfacies types. Marine settings can be differ-entiated into peritidal carbonates, platforms and ramps, platform-slope-basin transects, and pelagic deep-ma-rine carbonates. Grain Composition Logs are particu-larly effective in tracing platform-basin relations. Chapter 16: Recognizing Depositional Constraints and Processes. Selected case studies are used to demon-strate the value of microfacies data in interpreting depo-sitional controls.•How can microfacies be used in sequence stratigra-phy? Cyclic depositional patterns and sequence strati-graphic constraints are documented by microfacies data that assist in recognizing sequence boundaries, para-sequences, high-frequency sea-level changes, and sys-tems tracts.•Which criteria characterize reef limestones? Major reef types differ in biota, matrix, sediment, and cements. Which methods should be employed in reconstructing former platforms and reefs that are only recorded by eroded relicts deposited on slopes and in basins? Clast analysis can solve this puzzle.•Which criteria define ancient cold-water carbonates? Ancient cool-water shelf and reef carbonates are typi-fied by specific biotic, compositional and diagenetic features.•Which facies criteria are diagnostic of ancient vent-and seep carbonates? Case studies provide answers.•How to handle mixed carbonate-siliciclastic sedi-ments and interpret limestone-marl successions?•Constraints on carbonate deposition exhibit secular variations, which are discussed in the last section. Practical Use of MicrofaciesChapter 17: Reservoir Rocks and Host Rocks. Carbon-ates are the most important reservoir rocks for hydro-carbons as well as forming important host rocks for ores. Limestones and dolomites contain more than 50% of the world’s oil and gas reserves. Reservoir potential differs for carbonates formed in different depositional settings and depends on the interplay of depositional processes and diagenetic history. The microfacies of cores and cuttings assist in the translation of lithological data into petrophysical information. Facies-based out-crop-analogue studies indicate the scale of porosity andpermeability variations within carbonate bodies. Micro-facies analysis also assists in the genetic interpretation of carbonate-hosted base metal deposits controlled by specific facies patterns.Chapter 18: Carbonate Resources, Facies Control and Rock Properties. Carbonate rocks are important raw materials for chemical and construction industries and are high on the list of extracted mineral resources, both in terms of quantity and of value. Both exploration and exploitation can be enhanced by taking into account the relationships between depositional and diagenetic facies that control technologically relevant chemical and physical parameters, as well as the weathering and decay properties of carbonate rocks. Conservation and preservation of works of art and building stones should start with thin-section studies of the textural and di-agenetic criteria that describe the porosity and perme-ability of the material.Chapter 19: Archaeometry. Microfacies analysis, com-bined with geochemical data has considerable poten-tial in provenance analysis of archaeological materi-als. Thin sections reveal the source of building stones and of material used for mosaics and works of arts. The microfacies of temper grains in ancient pottery helps in understanding the source and production ar-eas for ceramics. Last but not least, microfacies stud-ies can throw new light at the love affair between Antony and Cleopatra....AcknowledgmentsThanks are due to many people who have provided photographs, information and advice:Gernot Arp (Göttingen), Martina Bachmann (Bre-men), Benoit Beauchamp (Calgary), Thilo Bechstädt (Heidelberg), Michaela Bernecker (Erlangen), Joachim Blau (Giessen), Florian Böhm (Kiel), Thomas Brachert (Mainz), Ioan Bucur (Cluj-Napoca), Werner Buggisch (Erlangen),Thomas Clausing (Halle), Wolf-Christian Dullo (Kiel), Paul Enos (Lawrence, Kansas), Gerd Flajs (Aachen), Christof Flügel (München), Helmut Flügel (Graz), Beate Fohrer (Erlangen), Holger Forke (Ber-lin), André Freiwald (Erlangen), Robert van Geldern (Erlangen), Markus Geiger (Bremen), Gisela Gerdes (Oldenburg), Eberhard Gischler (Frankfurt), Dirk von Gosen (Erlangen), Jürgen Grötsch (Damascus). Hans-Georg Herbig (Köln), Richard Höfling (Erlangen), B ernhard Hubmann (Graz), Andi Imran (Makassar), Michael Joachimski (Erlangen), Josef Kazmierczak (Warszawa), Martin Keller (Erlangen), Stephan Kempe (Darmstadt), Helmut Keupp (B erlin), Wolfgang Kiessling (B erlin), Roman Koch (Erlangen), Karl Krainer (Innsbruck), Jochen Kuss (Bremen), Michael Link (Erlangen), Heinz Lorenz (Erlangen), Ulrich Michel (Nürnberg), Axel Munnecke (Erlangen), Fritz Neuweiler (Göttingen), Alexander Nützel (Erlangen), Joachim Reitner (Göttingen), Jürgen Remane (Neuchâtel), Elias Samankassou (Genéve), Diethard Sanders (Innsbruck), Chris Schulbert (Erlangen), Baba Senowbari-Daryan (Erlangen), Robert J. Stanton (Thousand Oaks, California), Torsten Steiger (B ad B lankenburg), Thomas Steuber (B ochum), Harald Tragelehn (Köln), Jörg Trappe (Bonn), Dragica Turnsek (Ljubljana), Andreas Wetzel (Tübingen).I am indebted to Birgit Leipner-Mata and Marieluise Neufert (Institute of Paleontology Erlangen) for labo-ratory work and photography.Chris Schulbert (Institute of Paleontology) was a valuable help with all computer problems.I am sincerely grateful to my friend Johann Georg Haditsch (Graz) for critical reading the text of the book. Special thanks go to Karen Christenson (Nürnberg-Kraftshof) who took care of linguistic problems and pitfalls.Editing, layout, drawings and the preparation of plates and figures have been carried out by my wife Erentraud Flügel-Kahler. I am most grateful for her en-couragement and constant help.Finally, I am obliged to all institutions who gave permission to use published material and to the staff of Springer Verlag, especially to Dr. Wolfgang Engel for his constant encouragement and to Dr. J. Witschel for assistance with the book.X IContents1New Perspectives in Microfacies. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 1.1The Microfacies Concept. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 1.2New Perspectives. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1 2Carbonate Depositional Environments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 2.1Introduction. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 2.1.1Carbonates are Born not Made. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 2.1.2The ‘Sorby Principle’: Limestones are Predominantly BiogenicSediments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 2.1.3Modern Carbonates: Obligatory Reading. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7 2.2Carbonate Sediments Originate on Land and in the Sea. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 2.3Classification of Marine Environments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 2.3.1Boundary Levels. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 2.3.2Vertical and Horizontal Zonations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9 2.3.2.1Vertical Zonations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9 2.3.2.2Horizontal Zonations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 2.4Review of Modern Carbonate Depositional Environments. . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 2.4.1Non-Marine Carbonate Environments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 2.4.1.1Pedogenic Carbonates, Paleosols, and Caliche/Calcretes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 2.4.1.2Palustrine Carbonates. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 2.4.1.3Cave Carbonates, Speleothems and Karst. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 2.4.1.5Glacial Carbonates. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 2.4.1.6Travertine, Calcareous Tufa and Calcareous Sinter. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 2.4.1.7Lacustrine Carbonates: Lakes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 2.4.1.8Fluvial Carbonates. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 2.4.2Transitional Marginal-Marine Environments: Shorelines andPeritidal Sediments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 2.4.2.1Beach (Foreshore), Barriers and Coastal Lagoons. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 2.4.2.2Peritidal Environments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 2.4.3Shallow-Marine Sedimentary Environments: ‘Shallow’ and ‘Deep’. . . . . . 25 2.4.3.1Pericontinental vs Epicontinental Shallow Seas. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 2.4.3.2Carbonate Shelves, Ramps and Platforms. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 2.4.3.3Shelf Margins. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28 2.4.3.4Reefs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29 2.4.4Tropical and Non-Tropical Carbonates: Different in Composition,Controls and Significance. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30 2.4.4.1Latitudinal Zonation and Diagnostic Criteria of Tropical and Non-TropicalCarbonates. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31 2.4.4.2Tropical and Subtropical Shallow-Marine Carbonates. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 2.4.4.3Non-Tropical Shelf and Reef Carbonates. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 37 2.4.5Deep-Marine Environments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46 2.4.5.1Settings. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46 2.4.5.2Sedimentation Processes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47 2.4.5.3Pelagic Sedimentation. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 47 2.4.5.4Resedimentation (‘Allochthonous Carbonates’). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49XIIContents 2.4.5.5Carbonate Plankton and Carbonate Oozes. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49 2.4.5.6Preservation Potential and Dissolution Levels. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 49 2.4.5.7Carbonate Slopes, Periplatform Carbonates and Caronate Aprons. . . . . . . 50 2.4.6Seep and Vent Carbonates. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 51Microfacies Analysis3Methods. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53 3.1Field Work and Sampling. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53 3.1.1Field Observations. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53 3.1.1.1Lithology, Texture and Rock Colors. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 53 3.1.1.2Bedding and Stratification, Sedimentary Structures andDiagenetic Features. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 55 3.1.1.3Fossils and Biogenic Structures. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 59 3.1.1.4Field Logs and Compositional Logs. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 60 3.1.2Sampling. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 61 3.1.2.1Search Sampling and Statistical Sampling. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62 3.1.2.2How Many Samples?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62 3.1.2.3Practical Advice for Microfacies Sampling. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63 3.2Laboratory Work: Techniques. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64 3.2.1Slices, Peels and Thin Sections. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64 3.2.2Casts, Etching and Staining. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 65 3.2.3Microscopy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 3.2.3.1Petrographic Microscopy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 3.2.3.2Stereoscan Microscopy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 3.2.3.3Fluorescence, Cathodoluminescence and Fluid Inclusion Microscopy. . . . 67 3.2.4Mineralogy and Geochemistry. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70 3.2.5Trace Elements and Stable Isotope Analysis. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 704Microfacies Data: Matrix and Grains. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 73 4.1Fine-Grained Carbonate Matrix: Micrite, Microspar, Calcisiltite. . . . . . . . 73 4.1.1Micrite. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74 4.1.2Modes of Formation of Micrite and Other Fine-Grained Matrix Types. . . 80 4.1.3Microspar. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94 4.1.4Calcisiltite. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 95 4.1.5Practical Aids in Describing and Interpreting Fine-Grained Limestones. . 98 4.1.6Significance of Fine-Grained Carbonates. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98 4.2Carbonate Grains. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 100 4.2.1Bioclasts (Skeletal Grains). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 101 4.2.2Peloids: Just a Term of Ignorance?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110 4.2.3Cortoids – Carbonate Grains Characterized by Micrite Envelope. . . . . . . . 118 4.2.4Oncoids and Rhodoids. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 121 4.2.4.1Oncoids. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 124 4.2.4.2Rhodoids and Macroids. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 137 4.2.5Ooids. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 142 4.2.6Pisoids and Vadoids – Simply ‘Larger Ooids’ or Carbonate Grainson their Own?. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 157 4.2.7Aggregate Grains: Grapestones, Lumps and Other Composite Grains. . . . 163 4.2.8Resediments: Intra-, Extra- and Lithoclasts – Insiders and Foreigners. . . . 166 4.2.8.1Intraclasts: Origin and Facies-Diagnostic Types. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 167 4.2.8.2Extraclasts: Strange Foreigners. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 172 4.3Morphometry of Carbonate Grains. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 173 4.3.1Intentions and Methods. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 174 4.3.2Significance of Morphometric Data for Carbonate Grains. . . . . . . . . . . . . 175。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

Advanced Textbooks in Control and Signal ProcessingSeries EditorsProfessor Michael J. Grimble, Professor of Industrial Systems and DirectorProfessor Michael A. Johnson, Professor Emeritus of Control Systems and Deputy Director Industrial Control Centre, Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering, University of Strathclyde, Graham Hills Building, 50 George Street, Glasgow G1 1QE, UK Other titles published in this series:Genetic AlgorithmsK.F. Man, K.S. Tang and S. Kwong Introduction to Optimal EstimationE.W. Kamen and J.K. SuDiscrete-time Signal ProcessingD. WilliamsonNeural Networks for Modelling and Control of Dynamic SystemsM. Nørgaard, O. Ravn, N.K. Poulsenand L.K. HansenFault Detection and Diagnosis in Industrial SystemsL.H. Chiang, E.L. Russell and R.D. Braatz Soft ComputingL. Fortuna, G. Rizzotto, M. Lavorgna, G. Nunnari, M.G. Xibilia and R. Caponetto Statistical Signal ProcessingT. ChonavelDiscrete-time Stochastic Processes(2nd Edition)T. SöderströmParallel Computing for Real-time Signal Processing and ControlM.O. Tokhi, M.A. Hossain andM.H. ShaheedMultivariable Control SystemsP. Albertos and A. Sala Control Systems with Input and Output ConstraintsA.H. Glattfelder and W. Schaufelberger Analysis and Control of Non-linear Process SystemsK.M. Hangos, J. Bokor andG. SzederkényiModel Predictive Control (2nd Edition) E.F. Camacho and C. Bordons Principles of Adaptive Filters and Self-learning SystemsA. ZaknichDigital Self-tuning ControllersV. Bobál, J. Böhm, J. Fessl andJ. MacháčekControl of Robot Manipulators in Joint SpaceR. Kelly, V. Santibáñez and A. Loría Receding Horizon ControlW.H. Kwon and S. HanRobust Control Design with MATLAB®D.-W. Gu, P.H. Petkov andM.M. KonstantinovControl of Dead-time ProcessesJ.E. Normey-Rico and E.F. Camacho Modeling and Control of Discrete-event Dynamic SystemsB. Hrúz and M.C. ZhouBruno Siciliano • Lorenzo Sciavicco Luigi Villani • Giuseppe Oriolo RoboticsModelling, Planning and Control 123Bruno Siciliano, PhDDipartimento di Informatica e Sistemistica Università di Napoli Federico IIVia Claudio 2180125 NapoliItaly Lorenzo Sciavicco, DrEng Dipartimento di Informatica e Automazione Università di Roma TreVia della Vasca Navale 7900146 RomaItalyLuigi Villani, PhDDipartimento di Informatica e Sistemistica Università di Napoli Federico IIVia Claudio 2180125 NapoliItaly Giuseppe Oriolo, PhDDipartimento di Informatica e Sistemistica Università di Roma “La Sapienza”Via Ariosto 2500185 RomaItalyISBN 978-1-84628-641-4 e-ISBN 978-1-84628-642-1DOI 10.1007/978-1-84628-642-1Advanced Textbooks in Control and Signal Processing series ISSN 1439-2232A catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryLibrary of Congress Control Number: 2008939574© 2009 Springer-Verlag London LimitedMATLAB® is a registered trademark of The MathWorks, Inc., 3 Apple Hill Drive, Natick, MA 01760-2098, USA. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.The use of registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made.Cover design: eStudio Calamar S.L., Girona, SpainPrinted on acid-free paper9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1to our familiesSeries Editors’ForewordThe topics of control engineering and signal processing continue toflourish and develop.In common with general scientific investigation,new ideas,concepts and interpretations emerge quite spontaneously and these are then discussed, used,discarded or subsumed into the prevailing subject paradigm.Sometimes these innovative concepts coalesce into a new sub-discipline within the broad subject tapestry of control and signal processing.This preliminary battle be-tween old and new usually takes place at conferences,through the Internet and in the journals of the discipline.After a little more maturity has been acquired by the new concepts then archival publication as a scientific or engineering monograph may occur.A new concept in control and signal processing is known to have arrived when sufficient material has evolved for the topic to be taught as a specialised tutorial workshop or as a course to undergraduate,graduate or industrial engineers.Advanced Textbooks in Control and Signal Processing are designed as a vehicle for the systematic presentation of course material for both popular and innovative topics in the discipline.It is hoped that prospective authors will welcome the opportunity to publish a structured and systematic presentation of some of the newer emerging control and signal processing technologies in the textbook series.Robots have appeared extensively in the artisticfield of sciencefiction writing.The actual name robot arose from its use by the playwright Karel ˇCapek in the play Rossum’s Universal Robots(1920).Not surprisingly,theartistic focus has been on mechanical bipeds with anthropomorphic person-alities often termed androids.This focus has been the theme of such cine-matic productions as,I,Robot(based on Isaac Asimov’s stories)and Stanley Kubrick’sfilm,A.I.;however,this book demonstrates that robot technology is already widely used in industry and that there is some robot technology which is at prototype stage rapidly approaching introduction to commercial use.Currently,robots may be classified according to their mobility attributes as shown in thefigure.viii Series Editors’ForewordThe largest class of robots extant today is that of thefixed robot which does repetitive but often precise mechanical and physical tasks.These robots pervade many areas of modern industrial automation and are mainly con-cerned with tasks performed in a structured environment.It seems highly likely that as the technology develops the number of mobile robots will signif-icantly increase and become far more visible as more applications and tasks in an unstructured environment are serviced by robotic technology.What then is robotics?A succinct definition is given in The Chamber’s Dic-tionary(2003):the branch of technology dealing with the design,construction and use of robots.This definition certainly captures the spirit of this volume in the Advanced Textbooks in Control and Signal Processing series entitled Robotics and written by Bruno Siciliano,Lorenzo Sciavicco,Luigi Villani and Giuseppe Oriolo.This book is a greatly extended and revised version of an earlier book in the series,Modelling and Control of Robot Manipulators(2000, ISBN:978-1-85233-221-1).As can be seen from thefigure above,robots cover a wide variety of types and the new book seeks to present a unified approach to robotics whilst focusing on the two leading classes of robots,thefixed and the wheeled types.The textbook series publishes volumes in support of new disciplines that are emerging with their own novel identity,and robotics as a subject certainly falls into this category.The full scope of robotics lies at the intersection of mechanics,electronics,signal processing,control engineer-ing,computing and mathematical modelling.However,within this very broad framework the authors have pursued the themes of modelling,planning and control.These are,and will remain,fundamental aspects of robot design and operation for years to come.Some interesting innovations in this text include material on wheeled robots and on vision as used in the control of robots. Thus,the book provides a thorough theoretical grounding in an area where the technologies are evolving and developing in new applications.The series is one of textbooks for advanced courses,and volumes in the series have useful pedagogical features.This volume has twelve chapters cov-ering both fundamental and specialist topics,and there is a Problems section at the end of each chapter.Five appendices have been included to give more depth to some of the advanced methods used in the text.There are over twelve pages of references and nine pages of index.The details of the citations and index should also facilitate the use of the volume as a source of reference asSeries Editors’Foreword ix well as a course study text.We expect that the student,the researcher,the lecturer and the engineer willfind this volume of great value for the study of robotics.Glasgow Michael J.Grimble August2008Michael A.JohnsonPrefaceIn the last25years,thefield of robotics has stimulated an increasing interest in a wide number of scholars,and thus literature has been conspicuous,both in terms of textbooks and monographs,and in terms of specialized journals dedicated to robotics.This strong interest is also to be attributed to the inter-disciplinary character of robotics,which is a science having roots in different areas.Cybernetics,mechanics,controls,computers,bioengineering,electron-ics—to mention the most important ones—are all cultural domains which undoubtedly have boosted the development of this science.Despite robotics representing as yet a relatively young discipline,its foun-dations are to be considered well-assessed in the classical textbook literature. Among these,modelling,planning and control play a basic role,not only in the traditional context of industrial robotics,but also for the advanced scenarios offield and service robots,which have attracted an increasing interest from the research community in the last15years.This book is the natural evolution of the previous text Modelling and Con-trol of Robot Manipulators by thefirst two co-authors,published in1995,and in2000with its second edition.The cut of the original textbook has been confirmed with the educational goal of blending the fundamental and techno-logical aspects with those advanced aspects,on a uniform track as regards a rigorous formalism.The fundamental and technological aspects are mainly concentrated in the first six chapters of the book and concern the theory of manipulator structures, including kinematics,statics and trajectory planning,and the technology of robot actuators,sensors and control units.The advanced aspects are dealt with in the subsequent six chapters and concern dynamics and motion control of robot manipulators,interaction with the environment using exteroceptive sensory data(force and vision),mobile robots and motion planning.The book contents are organized in12chapters and5appendices.In Chap.1,the differences between industrial and advanced applications are enlightened in the general robotics context.The most common mechanicalxii Prefacestructures of robot manipulators and wheeled mobile robots are presented. Topics are also introduced which are developed in the subsequent chapters.In Chap.2kinematics is presented with a systematic and general approach which refers to the Denavit-Hartenberg convention.The direct kinematics equation is formulated which relates joint space variables to operational space variables.This equation is utilized tofind manipulator workspace as well as to derive a kinematic calibration technique.The inverse kinematics problem is also analyzed and closed-form solutions are found for typical manipulation structures.Differential kinematics is presented in Chap.3.The relationship between joint velocities and end-effector linear and angular velocities is described by the geometric Jacobian.The difference between the geometric Jacobian and the analytical Jacobian is pointed out.The Jacobian constitutes a fundamen-tal tool to characterize a manipulator,since it allows the determination of singular configurations,an analysis of redundancy and the expression of the relationship between forces and moments applied to the end-effector and the resulting joint torques at equilibrium configurations(statics).Moreover,the Jacobian allows the formulation of inverse kinematics algorithms that solve the inverse kinematics problem even for manipulators not having a closed-form solution.In Chap.4,trajectory planning techniques are illustrated which deal with the computation of interpolating polynomials through a sequence of desired points.Both the case of point-to-point motion and that of motion through a sequence of points are treated.Techniques are developed for generating trajectories both in the joint space and in the operational space,with a special concern to orientation for the latter.Chapter5is devoted to the presentation of actuators and sensors.After an illustration of the general features of an actuating system,methods to control electric and hydraulic drives are presented.The most common proprioceptive and exteroceptive sensors in robotics are described.In Chap.6,the functional architecture of a robot control system is illus-trated.The characteristics of programming environments are presented with an emphasis on teaching-by-showing and robot-oriented programming.A gen-eral model for the hardware architecture of an industrial robot control system isfinally discussed.Chapter7deals with the derivation of manipulator dynamics,which plays a fundamental role in motion simulation,manipulation structure analysis and control algorithm synthesis.The dynamic model is obtained by explicitly tak-ing into account the presence of actuators.Two approaches are considered, namely,one based on Lagrange formulation,and the other based on Newton–Euler formulation.The former is conceptually simpler and systematic,whereas the latter allows computation of a dynamic model in a recursive form.Notable properties of the dynamic model are presented,including linearity in the pa-rameters which is utilized to develop a model identification technique.Finally,Preface xiii the transformations needed to express the dynamic model in the operational space are illustrated.In Chap.8the problem of motion control in free space is treated.The distinction between joint space decentralized and centralized control strategies is pointed out.With reference to the former,the independent joint control technique is presented which is typically used for industrial robot control. As a premise to centralized control,the computed torque feedforward control technique is introduced.Advanced schemes are then introduced including PD control with gravity compensation,inverse dynamics control,robust control, and adaptive control.Centralized techniques are extended to operational space control.Force control of a manipulator in contact with the working environment is tackled in Chap.9.The concepts of mechanical compliance and impedance are defined as a natural extension of operational space control schemes to the constrained motion case.Force control schemes are then presented which are obtained by the addition of an outer force feedback loop to a motion control scheme.The hybrid force/motion control strategy isfinally presented with reference to the formulation of natural and artificial constraints describing an interaction task.In Chap.10,visual control is introduced which allows the use of infor-mation on the environment surrounding the robotic system.The problems of camera position and orientation estimate with respect to the objects in the scene are solved by resorting to both analytical and numerical techniques. After presenting the advantages to be gained with stereo vision and a suit-able camera calibration,the two main visual control strategies are illustrated, namely in the operational space and in the image space,whose advantages can be effectively combined in the hybrid visual control scheme.Wheeled mobile robots are dealt with in Chap.11,which extends some modelling,planning and control aspects of the previous chapters.As far as modelling is concerned,it is worth distinguishing between the kinematic model,strongly characterized by the type of constraint imposed by wheel rolling,and the dynamic model which accounts for the forces acting on the robot.The peculiar structure of the kinematic model is keenly exploited to develop both path and trajectory planning techniques.The control problem is tackled with reference to two main motion tasks:trajectory tracking and configuration regulation.Further,it is evidenced how the implementation of the control schemes utilizes odometric localization methods.Chapter12reprises the planning problems treated in Chaps.4and11 for robot manipulators and mobile robots respectively,in the case when ob-stacles are present in the workspace.In this framework,motion planning is referred to,which is effectively formulated in the configuration space.Several planning techniques for mobile robots are then presented:retraction,cell de-composition,probabilistic,artificial potential.The extension to the case of robot manipulators isfinally discussed.xiv PrefaceThis chapter concludes the presentation of the topical contents of the text-book;five appendices follow which have been included to recall backgroundmethodologies.Appendix A is devoted to linear algebra and presents the fundamentalnotions on matrices,vectors and related operations.Appendix B presents those basic concepts of rigid body mechanics whichare preliminary to the study of manipulator kinematics,statics and dynamics.Appendix C illustrates the principles of feedback control of linear systemsand presents a general method based on Lyapunov theory for control of non-linear systems.Appendix D deals with some concepts of differential geometry needed forcontrol of mechanical systems subject to nonholonomic constraints.Appendix E is focused on graph search algorithms and their complexity inview of application to motion planning methods.The organization of the contents according to the above illustrated schemeallows the adoption of the book as a reference text for a senior undergrad-uate or graduate course in automation,computer,electrical,electronics,ormechanical engineering with strong robotics content.From a pedagogical viewpoint,the various topics are presented in an in-strumental manner and are developed with a gradually increasing level of diffi-culty.Problems are raised and proper tools are established tofind engineering-oriented solutions.Each chapter is introduced by a brief preamble providingthe rationale and the objectives of the subject matter.The topics needed for aproficient study of the text are presented in thefive appendices,whose purposeis to provide students of different extraction with a homogeneous background.The book contains more than310illustrations and more than60worked-out examples and case studies spread throughout the text with frequent resortto simulation.The results of computer implementations of inverse kinemat-ics algorithms,trajectory planning techniques,inverse dynamics computation,motion,force and visual control algorithms for robot manipulators,and mo-tion control for mobile robots are presented in considerable detail in order tofacilitate the comprehension of the theoretical development,as well as to in-crease sensitivity of application in practical problems.In addition,nearly150end-of-chapter problems are proposed,some of which contain further studymatter of the contents,and the book is accompanied by an electronic solu-tions manual(downloadable from /978-1-84628-641-4)containing the MATLAB R code for computer problems;this is available free of charge to those adopting this volume as a text for courses.Special care hasbeen devoted to the selection of bibliographical references(more than250)which are cited at the end of each chapter in relation to the historical devel-opment of thefield.Finally,the authors wish to acknowledge all those who have been helpfulin the preparation of this book.With reference to the original work,as the basis of the present textbook,devoted thanks go to Pasquale Chiacchio and Stefano Chiaverini for theirPreface xv contributions to the writing of the chapters on trajectory planning and force control,respectively.Fabrizio Caccavale and Ciro Natale have been of great help in the revision of the contents for the second edition.A special note of thanks goes to Alessandro De Luca for his punctual and critical reading of large portions of the text,as well as to Vincenzo Lippiello, Agostino De Santis,Marilena Vendittelli and Luigi Freda for their contribu-tions and comments on some sections.Naples and Rome Bruno Siciliano July2008Lorenzo SciaviccoLuigi VillaniGiuseppe OrioloContents1Introduction (1)1.1Robotics (1)1.2Robot Mechanical Structure (3)1.2.1Robot Manipulators (4)1.2.2Mobile Robots (10)1.3Industrial Robotics (15)1.4Advanced Robotics (25)1.4.1Field Robots (26)1.4.2Service Robots (27)1.5Robot Modelling,Planning and Control (29)1.5.1Modelling (30)1.5.2Planning (32)1.5.3Control (32)Bibliography (33)2Kinematics (39)2.1Pose of a Rigid Body (39)2.2Rotation Matrix (40)2.2.1Elementary Rotations (41)2.2.2Representation of a Vector (42)2.2.3Rotation of a Vector (44)2.3Composition of Rotation Matrices (45)2.4Euler Angles (48)2.4.1ZYZ Angles (49)2.4.2RPY Angles (51)2.5Angle and Axis (52)2.6Unit Quaternion (54)2.7Homogeneous Transformations (56)2.8Direct Kinematics (58)2.8.1Open Chain (60)2.8.2Denavit–Hartenberg Convention (61)xviii Contents2.8.3Closed Chain (65)2.9Kinematics of Typical Manipulator Structures (68)2.9.1Three-link Planar Arm (69)2.9.2Parallelogram Arm (70)2.9.3Spherical Arm (72)2.9.4Anthropomorphic Arm (73)2.9.5Spherical Wrist (75)2.9.6Stanford Manipulator (76)2.9.7Anthropomorphic Arm with Spherical Wrist (77)2.9.8DLR Manipulator (79)2.9.9Humanoid Manipulator (81)2.10Joint Space and Operational Space (83)2.10.1Workspace (85)2.10.2Kinematic Redundancy (87)2.11Kinematic Calibration (88)2.12Inverse Kinematics Problem (90)2.12.1Solution of Three-link Planar Arm (91)2.12.2Solution of Manipulators with Spherical Wrist (94)2.12.3Solution of Spherical Arm (95)2.12.4Solution of Anthropomorphic Arm (96)2.12.5Solution of Spherical Wrist (99)Bibliography (100)Problems (100)3Differential Kinematics and Statics (105)3.1Geometric Jacobian (105)3.1.1Derivative of a Rotation Matrix (106)3.1.2Link Velocities (108)3.1.3Jacobian Computation (111)3.2Jacobian of Typical Manipulator Structures (113)3.2.1Three-link Planar Arm (113)3.2.2Anthropomorphic Arm (114)3.2.3Stanford Manipulator (115)3.3Kinematic Singularities (116)3.3.1Singularity Decoupling (117)3.3.2Wrist Singularities (119)3.3.3Arm Singularities (119)3.4Analysis of Redundancy (121)3.5Inverse Differential Kinematics (123)3.5.1Redundant Manipulators (124)3.5.2Kinematic Singularities (127)3.6Analytical Jacobian (128)3.7Inverse Kinematics Algorithms (132)3.7.1Jacobian(Pseudo-)inverse (133)3.7.2Jacobian Transpose (134)Contents xix3.7.3Orientation Error (137)3.7.4Second-order Algorithms (141)3.7.5Comparison Among Inverse Kinematics Algorithms (143)3.8Statics (147)3.8.1Kineto-Statics Duality (148)3.8.2Velocity and Force Transformation (149)3.8.3Closed Chain (151)3.9Manipulability Ellipsoids (152)Bibliography (158)Problems (159)4Trajectory Planning (161)4.1Path and Trajectory (161)4.2Joint Space Trajectories (162)4.2.1Point-to-Point Motion (163)4.2.2Motion Through a Sequence of Points (168)4.3Operational Space Trajectories (179)4.3.1Path Primitives (181)4.3.2Position (184)4.3.3Orientation (187)Bibliography (188)Problems (189)5Actuators and Sensors (191)5.1Joint Actuating System (191)5.1.1Transmissions (192)5.1.2Servomotors (193)5.1.3Power Amplifiers (197)5.1.4Power Supply (198)5.2Drives (198)5.2.1Electric Drives (198)5.2.2Hydraulic Drives (202)5.2.3Transmission Effects (204)5.2.4Position Control (206)5.3Proprioceptive Sensors (209)5.3.1Position Transducers (210)5.3.2Velocity Transducers (214)5.4Exteroceptive Sensors (215)5.4.1Force Sensors (215)5.4.2Range Sensors (219)5.4.3Vision Sensors (225)Bibliography (230)Problems (230)xx Contents6Control Architecture (233)6.1Functional Architecture (233)6.2Programming Environment (238)6.2.1Teaching-by-Showing (240)6.2.2Robot-oriented Programming (241)6.3Hardware Architecture (242)Bibliography (245)Problems (245)7Dynamics (247)7.1Lagrange Formulation (247)7.1.1Computation of Kinetic Energy (249)7.1.2Computation of Potential Energy (255)7.1.3Equations of Motion (255)7.2Notable Properties of Dynamic Model (257)7.2.1Skew-symmetry of Matrix˙B−2C (257)7.2.2Linearity in the Dynamic Parameters (259)7.3Dynamic Model of Simple Manipulator Structures (264)7.3.1Two-link Cartesian Arm (264)7.3.2Two-link Planar Arm (265)7.3.3Parallelogram Arm (277)7.4Dynamic Parameter Identification (280)7.5Newton–Euler Formulation (282)7.5.1Link Accelerations (285)7.5.2Recursive Algorithm (286)7.5.3Example (289)7.6Direct Dynamics and Inverse Dynamics (292)7.7Dynamic Scaling of Trajectories (294)7.8Operational Space Dynamic Model (296)7.9Dynamic Manipulability Ellipsoid (299)Bibliography (301)Problems (301)8Motion Control (303)8.1The Control Problem (303)8.2Joint Space Control (305)8.3Decentralized Control (309)8.3.1Independent Joint Control (311)8.3.2Decentralized Feedforward Compensation (319)8.4Computed Torque Feedforward Control (324)8.5Centralized Control (327)8.5.1PD Control with Gravity Compensation (328)8.5.2Inverse Dynamics Control (330)8.5.3Robust Control (333)8.5.4Adaptive Control (338)Contents xxi8.6Operational Space Control (343)8.6.1General Schemes (344)8.6.2PD Control with Gravity Compensation (345)8.6.3Inverse Dynamics Control (347)8.7Comparison Among Various Control Schemes (349)Bibliography (359)Problems (360)9Force Control (363)9.1Manipulator Interaction with Environment (363)9.2Compliance Control (364)9.2.1Passive Compliance (366)9.2.2Active Compliance (367)9.3Impedance Control (372)9.4Force Control (378)9.4.1Force Control with Inner Position Loop (379)9.4.2Force Control with Inner Velocity Loop (380)9.4.3Parallel Force/Position Control (381)9.5Constrained Motion (384)9.5.1Rigid Environment (385)9.5.2Compliant Environment (389)9.6Natural and Artificial Constraints (391)9.6.1Analysis of Tasks (392)9.7Hybrid Force/Motion Control (396)9.7.1Compliant Environment (397)9.7.2Rigid Environment (401)Bibliography (403)Problems (404)10Visual Servoing (407)10.1Vision for Control (407)10.1.1Configuration of the Visual System (409)10.2Image Processing (410)10.2.1Image Segmentation (411)10.2.2Image Interpretation (416)10.3Pose Estimation (418)10.3.1Analytic Solution (419)10.3.2Interaction Matrix (424)10.3.3Algorithmic Solution (427)10.4Stereo Vision (433)10.4.1Epipolar Geometry (433)10.4.2Triangulation (435)10.4.3Absolute Orientation (436)10.4.43D Reconstruction from Planar Homography (438)10.5Camera Calibration (440)。