译前准备对交替传译效果的影响

论译前准备对口译质量的影响

论译前准备对口译质量的影响作者:王庆张雨绮来源:《散文百家·下旬刊》2016年第11期摘要:由于两种语言存在着截然不同的区别,文化背景、用词习惯等方面的诸多不同,这就需要我们在进行口译前对其做好充分的本准备、环境准备和心理准备。

本文旨在对影响口译的诸多因素进行分析,提出合理有效的译前准备方案,以此达到成功完成口译的目的。

关键词:译前准备;表达说者之意;信息要点随着国际间交往的日益频繁,口译越来越多地出现在我们的工作中。

成功口译在能否完成双方共同的既定目标起着至关重要的作用。

外语的学习也应该越来越重视对这方面的培养,以符合时代社会的需求。

除了我们日常对外语言语、文化的日常积累外,在口译之前有针对性地进行准备工作也是极其重要的。

众所周知,翻译就是把已说出或写出的文字、文章用另一种语言来表达,以此来达到交际的目的。

我们在进行口译时不是单纯地把一种语言的词汇用另一种语言的词汇来套用,文化背景的不同,许多言语的不对等性,随着时代的发展所出现的新词、新意会使得我们的翻译出现偏差,甚至错误,有些时候会造成严重的后果,所以我们必须做好充分的译前准备。

译前准备指的就是口译任务开始之前,译员为顺利完成任务所进行的准备。

译前准备会帮助我们更快、更准确地表达说者之意,感情倾向,使得翻译表达清晰,准确。

一、充分了解掌握口译时的主题和背景口译涉及的范围和主题很广,既会有经济的、文化的、政治的,还会有医疗、环境方面的,它会涉及到我们生活、工作的各个领域。

在口译之前应该确定主题,对涉及的领域进行了解,除了在词汇方面做好十足的准备外,还应了解翻译的要求,例如是连续翻译还是同声传译,毕竟二者的要求,程序是不一样的。

除了主题之外,翻译所需的背景也是要了解的。

背景不同,所需词汇不同,翻译人的着装不同,是官方的还是民间的,是属于洽谈性的还是属于记者招待会,是属于签订文件还是属于发布公告之类的,只有这样才能做到心中有数。

二、精心准备词汇表学习外语,我们不能够什么领域的词汇都掌握,特别是一些专业性极强领域的专业词汇和特殊词汇,所以在准备过程中要掌握好所能涉及的所有词汇。

中国国际广播电视台访谈节目模拟交替传译实践报告以师村妙石访谈录为例

六、模拟交替传译实践过程及效 果

六、模拟交替传译实践过程及效果

1、准备阶段:在准备阶段,我们首先对师村妙石的访谈录进行了深入研究, 充分理解了原文的意思和文化背景。同时,我们也查阅了大量的参考资料,以扩 充自己的知识储备。

六、模拟交替传译实践过程及效果

2、模拟交替传译实践过程:在模拟交替传译实践中,我们采用了同传的方式, 即一人负责一部分内容的翻译。在翻译过程中,我们充分运用了之前提到的传译 技巧,力求使译文准确、流畅。同时,我们也注重与搭档的配合,确保翻译的连 贯性和准确性。

二、认知负荷模型与交替传译

二、认知负荷模型与交替传译

认知负荷模型认为,人类在处理复杂任务时,其认知资源有限,因此需要对 任务进行合理分配,以充分利用资源。在交替传译中,认知负荷模型可以帮助我 们理解口译员如何有效地分配注意力,以在短时间内准确翻译出源语言的信息。

三、模拟交替传译实践过程

三、模拟交替传译实践过程

五、结论

五、结论

本次实践报告表明,认知负荷模型可以有效地指导模拟交替传译实践。通过 理解和应用这一模型,我们可以更好地理解交替传译过程中的认知现象,并找到 提高翻译质量的方法。然而,本报告仅是一个初步的探索,未来研究可以进一步 探讨如何在真实的交替传译场景中应用认知负荷模型,以及如何通过培训和实践 来提高口译员应对高认知负荷的能力。

四、翻译难点与对策

四、翻译难点与对策

1、修辞手法丰富:师村妙石在访谈中频繁使用修辞手法,如比喻、象征等, 需要译者准确理解并转化为目标语言。

四、翻译难点与对策

2、文化背景复杂:访谈涉及大量日本传统文化和历史背景,需要译者具备相 关知识并适当解释。

四、翻译难点与对策

3、语言差异处理:日语和汉语在表达方式、句式结构等方面存在较大差异, 需要译者充分理解并适当调整。

交替传译在译员训练中的作用

The Role of Consecutive in Interpreter Training: A Cognitive ViewBy Daniel GILEFrom AIIC1. IntroductionWhether consecutive interpreting should be taught systematically in all interpreter training programs is a frequently debated question. One argument made forcefully against including CI training is that consecutive is gradually disappearing from the market. This claim is made mostly in Western Europe; in other markets, and in particular in Asia and in Eastern Europe, consecutive seems to be as lively as ever, due to its distinct advantages over simultaneous (less costly, less cumbersome in terms of equipment, more flexible over time and space).A further argument made against CI training is that in programs serving a market where this mode of interpretation is not required, learning consecutive means devoting much time and energy to the acquisition of skills not relevant to the market, time and energy that would be better invested in simultaneous. Some, however, counter this argument by claiming that simultaneous is just an "accelerated consecutive" and that the skills of consecutive are therefore relevant to simultaneous.This paper looks more closely at the nature of consecutive in cognitive terms, and brings this analysis into the debate.2. Is simultaneous an "accelerated consecutive"?In cognitive terms, the most fundamental problem in interpreting is that it is composed of a number of concurrent operations each of which requires processing capacity (PC), and the amount of PC required is often as much as - or even more than - the interpreter has available at the time it is needed.In simultaneous, such operations can be pooled together into "Efforts", such as:•the Listening Effort (listening to and analyzing the source speech);•the Production Effort (producing a target-language version of the speech);• a short-term Memory Effort (storing information just received from the speaker until it can be rendered in the target speech).All three "Efforts" include operations that require processing capacity, as is well known to psycholinguists. Seemingly "effortless" speech production does require attentional resources, as evidenced inter alia by hesitation pauses, which reflect intensive efforts to find an appropriate word and/or an appropriate syntactic structure to start, continue or end a sentence. This is true even in one's native language. Similarly, the seemingly "spontaneous" and "automatic" comprehension effort also requires attentional resources. If these are not invested into listening, words can be heard and forgotten without leaving meaningful traces in the listener's mind, as can be seen in consecutive when too much attention is devoted to note-taking and not enough to listening.In consecutive, during the listening phase, operations can be pooled together into:•the Listening Effort, the same as in simultaneous;•the Production Effort (producing notes, not a target-language version of the speech);• a short-term Memory Effort (storing information just received until it is noted - for that part of the information taken down as notes). During the reformulation phase, we have:• A Note-Reading Effort (some PC is required to understand - and sometimes decipher - the notes);• A long-term Memory Effort for retrieving information stored in long-term memory and reconstructing the content of the speech;• A Production Effort, for producing the target-language speech.On the basis of these "Effort Models", as they are known in the literature, the following differences between simultaneous and consecutive can be pointed out:(1) In simultaneous, two languages are processed at the same time in "working memory" (roughly, the cognitive resources engaged in short-term processing of information just received). This requires devoting some attention to inhibiting the influence of the source language when producing the target speech in order to avoid interference. In consecutive, this constraint is much weaker, or even non-existent, depending on the way the notes are taken (even if notes are taken in the source language, they are generally single words rather than full sentence structures, hence the likelihood of less interference). Moreover, while speaking, the interpreter can devote more attention to monitoring his/her output in consecutive than in simultaneous as part of the Production Effort.(2) In simultaneous, target-speech production occurs under heavier time pressure than in consecutive, where the interpreter can pace him/herself. This is particularly important for speech segments with high information density, where the pressure in simultaneous is particularly high. In consecutive, it is also high during the listening phase, and therefore affects Note Production, but loses its urgency during the reformulation phase.These two differences explain and justify the fact that some colleagues are willing to work into their B language in consecutive, but not in simultaneous.(3)In consecutive, while listening, interpreters have to decide what to take down in their notes and how. They also have to devote some attention to the writing process itself. These operations, which require specific know-how, are not found in simultaneous.(4) In consecutive, the slowness of writing and the resulting delay between the moment information is heard and the moment it is noted submits working memory to high pressure in a specific way that is not present in simultaneous, at least in language pairs not requiring extensiveword-order changes. (In language pairs requiring extensive word-order changes, the lag-related cognitive load in simultaneous may be similar to that in consecutive.) Coping with this writing-induced load requires specific strategies and know-how.(5) In consecutive, there is much more involvement of long-term memory (in the range of a few minutes) than in simultaneous.These and other differences mean that it takes time to reach proficiency in the specific skills of consecutive, and that good simultaneous interpreters are not automatically good consecutive interpreters and vice-versa. In particular, there is no reason to assert that good mastery of consecutive should be a pre-requisite for simultaneous.3. Pedagogical considerationsGiven the above, why should it make sense to teach consecutive to students whose market does not require it?The advantages of consecutive are the following:(1) Separation between the listening phase and the reformulation phase in consecutive leaves reformulation free of heavy time constraints. Students can therefore be taught fundamental methodological principlesrelated to "translation" problems (fidelity norms, linguistic norms, reformulation strategies, etc.). In simultaneous, time pressure may make students less receptive to suggestions in this respect, as many object that they do not have time to think of all the solutions proposed by instructors.(2) Separation between the listening phase and the reformulation phase makes it possible to use time more efficiently than in simultaneous for basic instruction in listening and reformulation strategies: in simultaneous, the number of students practicing at the same time is limited by the number of available booths in the classroom; in consecutive, all students in the room are engaged in the listening phase at all times, when listening to the source speech and when listening to its interpretation by a classmate (provided the instructor tells them to listen to the interpretation and comment on it).(3) In consecutive, it is possible for students to focus more easily than in simultaneous on the listening component and see what they missed: indicators of one's comprehension of the source speech are found in the notes, and in the students' ability to reconstruct the speech from their notes while following the target speech of the student who is performing in class. In simultaneous, the students' recollection of their comprehension is more blurred.In-depth analysis has long been recognized as a major quality component of interpreting (and translation). The importance of this advantage of consecutive should not be underestimated.(4) In consecutive, it is easier than in simultaneous to work ontarget-language production, since, as explained above, there is much less interference from the source language and from time pressure. Working on target-language production means working on correctness, on linguistic norms, on flexibility enhancement, and on the eradication of linguistic interference.Incidentally, the separation between the two phases makes it easier in consecutive than in simultaneous to detect weaknesses in the students' mastery of the target language. In simultaneous, language problems in the output may also be linked to processing capacity saturation and/or wrong decision-making, and it is difficult to do an accurate diagnosis.(5) More generally, separation between the two phases also makes it easier to control target-speech fidelity. In simultaneous, correcting for fidelity takes much longer and is more complex, requiring either the useof transcripts or alternately listening to source-speech andtarget-speech recordings.4. ConclusionAs I hope to have demonstrated through this synoptic discussion, on the one hand, consecutive corresponds to a partly distinct set of skills which require time and effort to master, and on the other, it offers distinct advantages in the classroom. What should the proper strategy be, then, in those programs serving markets where there is no (perceived) need for consecutive?My personal opinion is that consecutive is too valuable to dispense with, at least during the first half of a program. I do not believe, however, that perfect mastery of consecutive should necessarily be institutionalized as a mandatory requirement for the conference interpreter's degree. A range of compromise solutions can be contemplated, starting with a minimum solution, which would entail several weeks of training in consecutive on relatively brief and easy speeches (in terms of speed, technicality and logic), enough to work on the listening and production components and to detect and correct major weaknesses in students, but not enough to reach maturity in note-taking and in the processing of difficult speeches in consecutive. Alternatively, consecutive could be taught throughout the training program, but not be tested as a requirement for the degree, except as a special option. The option of keeping full mastery in consecutive as a requirement for the degree is legitimate as well, at least in those markets where consecutive is still present. Decisions should be left to program leaders, depending on the length and status of the program, on the students, and on the markets to be served. The one trap to avoid is a dogmatic attitude, one way or another.5. Bibliographical tipsThis short paper only briefly raises the main issues. Colleagues who wish to gain more insight into ideas, concepts and research on consecutive will find many interesting texts explaining the fundamental ideology of consecutive as the basis of conference interpreting and giving pedagogical advice in writings by authors from ETI, Geneva (Ilg, Rozan) and ESIT, Paris (Lederer, Seleskovitch, Thiéry). The issue of processing capacity and the Effort Models are explained inter alia in texts by Gile.A few recent books on consecutive were written in Italy (Claudia Monacelli, Falbo et al.) and Spain (Catalina Iliescu). Interesting empirical research (experimental and non-experimental) has been and is being carried out inter alia by Cai Xiaohong and other researchers in China,by scholars in Japan, and by Peter Mead and others in Italy. A rather comprehensive bibliography was prepared by Gérard Ilg and published in 1996 in Interpreting1:1 (88-99). For a relatively comprehensive list and some details about more recent studies, consult recent issues of the IRN Bulletin。

学生译员英汉交替传译中的听辨障碍及其应对策略

学生译员英汉交替传译中的听辨障碍及其应对策略摘要:通过问卷调查、个人座谈和回放口译录音等方式,考察了38名学生口译员的口译过程。

调查显示:学生译员遇到的听辨障碍主要与词汇量、专业术语、源语发言者的语速及语音语调、译员自身的听力水平、译员的个人状态和心理素质和译员的英语国家社会文化背景知识这几大因素有关。

针对此情况,提出了四项应对策略:有针对性地进行译前准备和主题预测;扩充词汇量和熟悉英语国家社会文化背景知识;进行语音语调的强化训练。

关键词:学生译员;英汉交传;听辨障碍;应对策略一、研究背景听辨能力是口译过程中的一项基础能力,是口译活动能否顺利进行的重要参考指数。

口译中的分析理解过程是与听辨过程同时进行的。

Gile认为,口译的理解,是译员的语言知识和非语言知识相互作用、分析综合的结果。

Seleskovitch 提出的口译三角模式认为,翻译并不是一种语言的转换过程,其核心在于译员对“意义”的理解和表达。

对于口译过程中的听辨能力,国内不少研究者也做过不同程度的研究。

刘和平认为,口译的理解过程就是分析综合的过程,包括语音听辨、语法层次分析、语义和篇章分析、文体修辞分析、文化分析、社会心理分析、意义推断和综合。

杨晓华用心理语言学和认知语言学的知识分析译员理解时的信息加工过程,并强调言外知识的重要性。

李学兵分析了口译过程中影响口译译员理解的因素。

这些研究对于提高译员的听辨能力,都有很大的帮助和启发。

但是,我们也看到,这些研究或多或少都根源于Gile的口译理解模式,同时,缺乏对口译听辨过程的实证研究,一手的数据和观察结果比较缺乏。

口译过程中到底有哪些不同类型的听辨障碍?导致这些障碍的主要因素有哪些?我们可以采取什么样的策略来应对?本次实证研究尝试找到这些问题的答案。

本研究着重考察从英语转换到汉语的交替传译活动,详细描述译员在完成口译任务过程中表现出的听辨障碍及其相关特征,力图揭示这一特定的双语转换活动中存在的一般性策略和方法,为口译实践和口译教学提供更具体的指导。

英语口译交替传译要领

英语口译交替传译要领交传, 是译员在讲话人讲完一句、一个意群、一段甚至整篇后译出目标语言的翻译方式。

两会期间举行的新闻发布会采用的都是交传。

和同传比较起来,交传时译员是和听者直接见面的,因而受到的关注比较多,心理压力也相对较大;同时,由于译员有一定的时间对源语言(句、意群、段或篇)的.整体内容进行理解并在组织译文的过程中对结构做出必要的调整,通常大家预期的翻译质量也会比较高。

鉴于这两点,交传的难度相对较大,同时它也更能反映出翻译的水平。

无论在任何场合,如正式谈判、礼节性会见、新闻发布会、参观、游览、宴请、开幕式或电话交谈中,要做好交传都离不开以下工作:1. 大量练习。

有条件的,可采取两人一组的方式,一人充当讲话者,另一人担任翻译。

一个人练习可采用视译的方法,看报读书时,将某些段落做成笔记,随后口译出来。

2. 有效的笔记系统。

关联词的记录应得到特别重视,以确保翻译时,用一根线就能连起一串珠。

3. 心理素质的培养。

大声朗读是一种不错的方法。

还可练习在小型会议上发表自己的观点,同人交流。

若能通过在一些比较正式的比赛、演出中登台以增强信心,锻练胆量,则更是良策了。

4. 每次活动的认真准备。

对会谈要点、发布会口径、参观将会涉及的技术用语等都要尽可能充分地掌握,以便翻译时成竹在胸,游刃有余。

不同场合的交传则主要表现在处理方式和风格把握上的差异。

正式谈判、新闻发布会和开幕式等都是严肃、庄重的活动,翻译应立场鲜明、沉稳准确、语速适中。

礼节性会见一般不涉及实质性问题,通常以寒暄和互通情况为主,翻译应很好地传递友好的信息,维护宾主双方共同营造的融洽气氛。

宴请除开头或结尾部分的祝酒外,多为随意的攀谈,翻译时可多用口语,使轻松的谈话成为美食的佐餐。

参观、游览时,翻译重在抓住要害,传递信息,视需要可作概括,语速稍快亦可。

电话翻译时由于缺少了一般翻译时的眼神交流(eye contact),听力理解的难度增高,因此应高度专注,以听为主,以记为辅,语速要适当放慢,确保对方准确无误地接收到所发信息。

全国翻译专业二级口译证书(Catti2)备考指南

全国翻译专业二级口译证书(Catti2)备考指南翻译口译专业的学生,最绕不开的考试当属全国翻译专业资格证书(catti)和上海高级口译证书。

2019年,我分别于5月和11月通过了二口和二笔考试,在此分享一下常见备考问题和个人快速备考的经验。

我是翻译专业出身,17年在英国读口译研究生。

回国后的主业虽然和英语相关,但口译实践较少,所以备考以熟悉题型、找到口译临场的状态为主。

本文也比较适合MTI在读生或从事英语相关工作,有一定翻译口译基础的知友们参考。

成绩单如下:一、常见问题1、catti系列考试有啥用?catti考试不仅包括英语,还包括日、韩、法、德等小语种。

catti口、笔译资格证是官方唯一认定的翻译职业资格考试,相比上海高口证书在长三角地区的接受度,这个考试在全国范围内的接受程度更高,也是对考生翻译能力的检验。

在很多翻译类职位的招聘要求中,拥有catti二口及以上的资格证书也是一条硬门槛。

另外,根据人事部相关规定,二级口、笔译证书可以评定企事业单位的中级职称。

2.非英语专业可以报考吗?catti三级和二级报考不限专业,但从19年开始,官网报名需要进行教育部学历认证(学信网),审核时间在24h以内。

我个人不是很清楚其他学历或社会报考的条件。

参加catti一级口笔译考试,需要先获得同类考试的二级证书。

3、通过catti考试是否等于职业译员?catti考试中的实务部分尽可能还原了交替传译的现场,但与实际工作还是有很大差别。

获得catti二级证书只是拿到了一块敲门砖,考生还需要在实践中总结经验,积累人脉,才能成为真正的职业翻译。

4、考试时间和形式?每年两次考试,分别在6月和11月,一般提前2个月左右在官网报名,基本全国的直辖市和省会城市均有考点。

考试前一周打印准考证。

相关信息可以关注微博@ CATTI考试资料与资讯2020年受疫情影响,上半年6月的考试已确定顺延。

从2018年开始,全国范围内的catti考试改革为机考。

汉英交替传译信息流失的心理因素及应对策略

知识文库 第16期258汉英交替传译信息流失的心理因素及应对策略李国润译员在进行交替传译时都会产生紧张情绪,作为一名优秀的译员应该能够适时调整情绪, 努力使自己集中精力,排除干扰,从而保质保量地完成口译任务。

口译工作对译员的心理素质要求很高,因此,积极调整心态和善于调节紧张情绪也是译员所必须具备的素质。

一、汉英交替传译信息流失的心理因素 1、外因在汉英交替传译过程中,译员经历真实、紧张的环境,周围会有很多外在的干扰与不利因素影响着译员的翻译质量。

比如:在我国,一些重要的会议和公开场合的演讲发言都在比较大型的会场举行。

场内可以容纳很多观众,但是宽敞的会场大厅也可能产生大量的噪音干扰,译员难免会受其影响,影响翻译质量。

其次,如果源语者来自南方一些省市,他们的发言带有浓厚的地方口音和较多的方言,令人难以听辨,这无疑给译员造成更大的心里压力。

2、内因内因来源于译员的语言基本功、双语转换能力以及自己稳定的心理素质。

译员由于经验不足,产生紧张情绪,或是知识储备欠缺,而前期的准备工作也没有涉及到此类知识,亦或是双语转换能力不强,都会影响到翻译的质量。

此外,有一些译员心理素质较差,到达口译现场后感受到现场的紧张气氛,看到台下众多的观众,可能会产生恐惧心理。

还有一些译员缺乏自信,总是怀疑自己的口译能力,对已经翻译完的内容抱有不确定的心理;或是出现了一次漏译、误译之后就总是无法释然,影响到接下来的翻译内容。

口译工作不是简单地语音听辨,也不是单纯地将一种语言转换成另一种语言,口译是一种将目标语进行“分析、整理、重新表达”的完整过程。

口译过程实质上是一个将译员的认知水平和语言处理能力相结合,二者共同参与并相互控制的一个复杂的心理过程。

与同声传译相比其难度在于,交传要抓住源语者说话重点,更加注意意思准确、完整,语言通顺易懂,不能拖泥带水,对译文的准确性也要求更高。

译员进行交替传译时要面对观众单独发言,其实质更像是在台上面向观众进行独唱表演,所以交替传译比同声传译更有表演因素,因此译员在传译时要有表演意识。

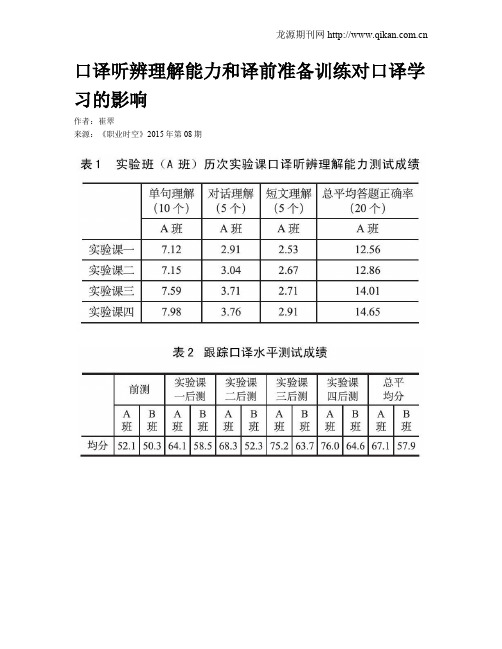

口译听辨理解能力和译前准备训练对口译学习的影响

口译听辨理解能力和译前准备训练对口译学习的影响作者:崔翠来源:《职业时空》2015年第08期摘要:以未开展口译学习的英语教育专业学生为研究对象,进行了四次口译实验课。

经过口译能力前测、后测,结合问卷、访谈等进行数据分析,发现口译听辨理解技能训练能有效提高口译学习者的听辨理解水平;对口译学习者的口译质量产生积极影响;译前准备对口译质量的影响非常明显。

关键词:口译听辨理解能力;训练;译前准备;口译学习;实验课一、引言西方著名的翻译理论家、翻译实践家和教育家塞莱斯科维奇在其著作《口译技艺》中指出口译的过程可以划分为三个阶段:听到带有一定含义的语言声;记住原话所表达的思想内容;用译成语说出新话。

口译也可以分为语言信号的输入、语言信号的处理和语言信号的输出三大环节。

作为一种交际活动,口译中的信息主要是通过听来获取的。

因此,口译过程的第一环节就涉及听辨能力,听懂是口译的关键步骤,译者的听力水平是成功口译的基础。

事实上,在基础口译的教学阶段,学生的听辨理解能力往往是口译学习的一个瓶颈(仲伟合,王斌华2009:Ⅳ)。

在国际口译领域有较大影响力的Gile将口译中的听力分析活动(Listening and Analysis Efforts)定义为“所有与听力理解有关的活动,包括译者辨析语音符号、识别字词的含义到最后决定讲话人所表达的意思”(Gile 1995:162),并提出了经典的口译理解方程式:C(理解)=KL(语言知识)+EKL(非语言知识)+A(分析)。

在国内,刘宓庆教授(2004:87)认为口译听力既包括“听”(接收、理解),也包括“力”(加工、产生),涵盖了从信息的捕捉分解、综合到理解的全过程。

而译前准备既是交替传译的一个“重要環节”,又是译员必备的基本功。

从准备的内容分,译前准备可分为语言知识准备、专业知识准备、职业素养准备和身体素质准备。

具体到一项商务陪同口译的译前准备工作分为:任务信息的准备、行业知识的准备、术语准备、商务礼仪知识的准备、口译工具的准备、口译技能的准备等。

- 1、下载文档前请自行甄别文档内容的完整性,平台不提供额外的编辑、内容补充、找答案等附加服务。

- 2、"仅部分预览"的文档,不可在线预览部分如存在完整性等问题,可反馈申请退款(可完整预览的文档不适用该条件!)。

- 3、如文档侵犯您的权益,请联系客服反馈,我们会尽快为您处理(人工客服工作时间:9:00-18:30)。

最新英语专业全英原创毕业论文,都是近期写作1 通过《喧哗与骚动》中三兄弟各自对于凯蒂的叙述分析三人各自性格特征2 An Exploration on Different Cultures in Terms of Flowers3 从跨文化角度论谚语中的比喻与翻译4 浅析唐诗翻译的难点和策略(开题报告+论)5 A Glimpse of Intercultural Marriage between China and Western Countries6 An Analysis of Harmonious Coexistence Between Nature and Civilization in Wuthering Heights From the Perspective of Eco-criticism7 Foreign Publicity Translation8 美国基督新教与中国儒家的伦理道德的比较9 从功能对等的角度论英语习语翻译10 从《洛丽塔》看美国世纪中期的消费文化11 英语政治新闻中委婉语的形式及语用功能研究12 通过苔丝透析托马斯•哈代的现代女性意识13 解析《德伯家的苔丝》中女主人公的反叛精神和懦弱性格14 农村学生英语学习情感障碍分析15 浅谈中西婚俗的文化差异16 “红”、“黄”汉英联想意义对比研究17 《玻璃动物园》中的逃避主义解读18 出人意料的结局和夸张-基于欧亨利的短篇小说《忙碌经纪人的罗曼史》19 英语广告中仿拟的关联分析20 文学翻译中的对等21 浅谈中外记者招待会中口译者的跨文化意识22 浅析科技英语的文体特点23 对夏洛蒂勃朗特《简爱》中简爱的女性主义分析24 伊丽莎白.贝内特与简.爱的婚姻观之比较25 对狄金森诗歌中四个主题的分析26 The Application of Symbolism in The Great Gatsby27 《威尼斯商人》中鲍西亚形象浅析28 《永别了,武器》一书所体现的海明威的写作风格29 A Brief Study of Bilingual Teaching in China--from its Future Developing Prospective30 汉语公示语的英译31 大学英语四级考试的效度32 论奥斯卡•王尔德的矛盾性——从传记角度解读《奥斯卡•王尔德童话集》33 从原型批评的角度透视《野草在歌唱》的人物及意象34 报刊广告英语的文体特色分析35 从《了不起的盖茨比》看美国梦的幻灭36 红色,英汉词汇差异的文化理据37 解读罗伯特•彭斯的爱情观——以《一朵红红的玫瑰》和《约翰•安德生,我的爱人》为例38 简•奥斯汀《诺桑觉寺》中人物对爱情和婚姻的不同态度39 《格列佛游记》中格列佛的人格探析40 归化与异化策略在字幕翻译中的运用41 An Analysis of the Religious Elements in Robinson Crusoe42 英汉动物习语文化内涵对比研究43 协商课程在高中英语教学中的应用初探44 从交际方式的角度比较中美课堂差异45 英语学习中的性别差异46 汉英姓氏文化差异47 浅析《傲慢与偏见》中女性人物的认知局限48 悖论式的唯美主义--论王尔德的《道连•格雷的画像》49 《远离尘嚣》中女主角的情感变迁研究50 菲尔丁小说《汤姆•琼斯》中的戏剧因素分析51 浅析初中学生英语阅读理解障碍及解决对策52 “美国梦”的再探讨—以《推销员之死》为例53 Cultural Differences and Idiomatic Expressions in Translation54 《威尼斯商人》中夏洛克与《失乐园》中的撒旦的反叛者形象比较55 对林语堂的《吾国与吾民》几种中译本比较研究56 《简•爱》中的女性主义意识初探57 从语境视角看英译汉字幕翻译——以《梅林传奇》为例58 Study of Themes of George Bernard Shaw’s Social Problem Plays59 浅析《理智与情感》中简奥斯汀的婚姻观60 西方饮食文化给中国餐饮业经营者带来的若干启示61 Hardy’s View of feminism from Sue Bridehead in Jude the Obscure62 浅谈《竞选州长》中的幽默与讽刺63 从中美餐饮礼仪差异谈跨文化交际64 浅谈商务英语信函写作65 从自然主义角度解读《人鼠之间》中的美国梦(开题报告+论文 )66 中西方奢侈品消费文化之比较67 功能对等理论视角下的商务合同翻译研究68 传统道德与时代新意识之战―论林语堂在《京华烟云》中的婚恋观69 《哈克贝利•费恩历险记》的艺术特色分析70 现代英语新词分析71 高中英语课堂中的文化渗透72 The Gothic Elements in Edgar Allan Poe’s Works73 从文学伦理阐释《榆树下的欲望》母杀子的悲剧74 福克纳《我弥留之际》女主人公艾迪的形象探析75 法律英语的语言特点及其翻译76 英汉汽车广告中常用“滑溜词”的对比分析77 欲望与死亡——对马丁伊登的精神分析78 论英汉翻译过程79 On the Translation of Chinese Classical Poetry from Aesthetic Perspective—Based on the different English versions of “Tian Jing ShaQiu Si”80 On Sentence Division and Combination in C-E Literature Translation81 英语演讲语篇中的parallelism及其汉译策略—以奥巴马就职演说稿为例82 托尼•莫里森《宠儿》的哥特式重读83 以《哈利波特与消失的密室》为例探讨哥特式风格在哈利波特小说系列中的应用84 涉外商函的特点及其翻译85 从关联理论角度看电影台词翻译—电影“小屁孩日记”的个案研究86 从合作原则角度解读《成长的烦恼》中的言语幽默87 浅谈《欲望号街车》所阐述的欲望88 从人际功能和言语行为理论解析《儿子与情人》的对话89 从《红楼梦》和《简爱》看中西方女性主义90 试论英语中的歧义与翻译91 Joy Luck Club:Chinese Tradition under American Appreciation92 房地产广告的英译研究93 中西方传统女权主义思想异同比较——王熙凤与简爱之人物性格对比分析94 中国菜名翻译方法的研究95 基于质量准则的英语修辞分析96 从男性角色解读《简爱》中的女性反抗意识97 浅谈当代大学生炫耀性消费文化98 从童话看中西方儿童教育的差异99 Psychological Analysis of Holden in The Catcher in the Rye100 通过会话原则分析手机短信语言101 从“三美”原则看《荷塘月色》的翻译102 The Application of Situational Teaching Approach in the Lead-in of Middle School English Classes103 论《紫色》中的性别暴力104 浅谈文化差异对英语明喻汉译的影响105 浅谈跨文化视角下的英汉习语互译106 小说《飘》中斯嘉丽的人物性格分析107 一个女性的悲剧—从人性角度浅析苔丝的悲剧108 从广交会现场洽谈角度论英语委婉语在国际商务谈判中的功能与应用109 《论语》中“孝”的英译——基于《论语》两个英译本的对比研究110 Influence of Cross-Cultural Differences on the Translation of Chinese and English Idioms111 论《呼啸山庄》中两代人之间不同的爱情观112 爱默生超验主义对世纪美国人生观的影响——以《论自助》为例113 The Lost Generation—“Nada” in Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”114 The Elementary Stage Translation Teaching Design for Undergraduate English Majors115 埃德加•爱伦•坡短篇小说的语言特色分析116 中西面子观的比较研究117 论法律英语的语言特征及其翻译118 浅谈高中英语练习课教学119 塞林格《麦田里的守望者》的逃离与守望120 浅析商务谈判中非言语交际的核心地位121 论英语课堂教学中的非语言交际122 英语词汇的文化内涵及词汇教学123 是受害者还是恶棍?——重新解读夏洛克124 英语意识流小说汉译现状及对策研究125 论林纾翻译小说中的翻译策略126 英语专业学生语音学习中的问题127 从主角与配角之间关系的角度探讨《老人与海》中的生存主题128 The Application of Computer Assisted Instruction in Senior English Listening Teaching129 论英语口语教学中存在的问题及对策130 《名利场》中的女主人公性格分析131 中英文颜色词的文化内涵及翻译132 解读奥斯卡•王尔德的《莎乐美》中的女性意识133 中美婚姻观对比研究134 The Analysis of Pearl in The Scarlet Letter135 试析《傲慢与偏见》中的书信136 从《永别了,武器》与《老人与海》浅析海明威的战争观137 论英语被动语态的语篇功能及其翻译策略—以《高级英语》第二册为例138 从《金色笔记》看多丽丝•莱辛的女性意识139 中美电影文化营销的比较研究140 Culture Teaching in College English Listening Classrooms141 对外新闻的导语编译研究142 析《麦田里的守望者》霍尔顿•考尔菲德的性格特征143 旅游景点标志翻译初探144 Application of Cooperative Learning to English Reading Instruction in Middle School145 浅析中美商务谈判中的文化冲突146 A New View of Feminism in The Mill on the Floss River147 西方吸血鬼与中国鬼的文学形象比较(开题报告+论)148 从跨文化交际角度看电影片名翻译149 论英语影视作品的字幕翻译技巧150 《天黑前的夏天》中女主人公凯特的自我救赎之路151 《简爱》在当代中国的现实意义——从温和的女性主义视角分析152 《了不起的盖茨比》与美国梦的破灭153 英文歌曲在提高英语专业学生口语能力方面的作用154 从《永别了,武器》与《老人与海》浅析海明威的战争观155 论英文电影字幕翻译及其制约因素——以《别对我说谎》为例156 英汉味觉隐喻的对比研究157 哈利波特的情感分析158 A Probe into the Spiritual Worlds of The Old Man and the Sea159 论《海的女儿》的女性自我价值主题160 《白雪公主》的后现代主义创作技巧161 论石黑一雄《别让我走》中新与旧的世界162 由《红楼梦》中人名的英译看中西文化差异163 从文化角度看中西饮食文化的差异164 浅析美剧台词中幽默的翻译——以《绝望的主妇》为例165 商务英语中的委婉表达及其翻译166 英汉动物词汇文化内涵对比167 英语体育新闻标题的特点及其翻译168 从容•重生—解读《肖申克的救赎》中的人物心态169 从文化差异的角度看《红楼梦》颜色词的英译170 从等效理论视角看汉英外宣翻译171 概念隐喻视角下看莎士比亚十四行诗172 A Feminist Study of William Shakespeare’s As You Like It173 人性的堕落——解析《蝇王》人性恶的主题174 基本数字词在中西文化中的差异与翻译175 对张爱玲与简•奥斯汀作品的比较性研究176 The Analysis of Teacher Images in English Films And Their Impacts on Young Teachers177 中英爱情隐喻的对比研究178 论《呼啸山庄》中的叙述技巧179 论《了不起的盖茨比》中二元主角的运用180181 从功能对等理论来看委婉语翻译182 论欧•亨利的写作风格183 论《阿芒提拉多酒桶》中文学手法的运用及其艺术效果184 分析与比较中美电视新闻的娱乐化,及其未来的发展185 中西方爱情悲剧故事的比较分析——以“梁祝”和《罗密欧与朱丽叶》为例186 黑人英语克里奥起源论187 山寨文化的反思——发展与创新188 跨文化商务谈判中的文化差异及应对技巧189 从《胎记》中阿米那达布的人物分析看人性的原始表达190 A Superficial Analysis of Religious Consciousness of Jane Eyre191 The Inconsistencies between Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind and Alexandra Ripley’s Scarlett192 高中英语听力课中的文化教学193 论海勒《约塞连幸免于难》的黑色幽默的荒诞与反讽194 英国文化中的非语言交际的研究195 高中英语“后进生”产生的原因以及补差方法研究196 《雾都孤儿》中的童话模式解读197 Cultural Differences Between English and Chinese by AnalyzingBrand Names198 论简·奥斯汀在《傲慢与偏见》中的婚姻观199 译前准备对交替传译效果的影响200 论远大前程中皮普的道德观。